Submitted:

12 September 2023

Posted:

13 September 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

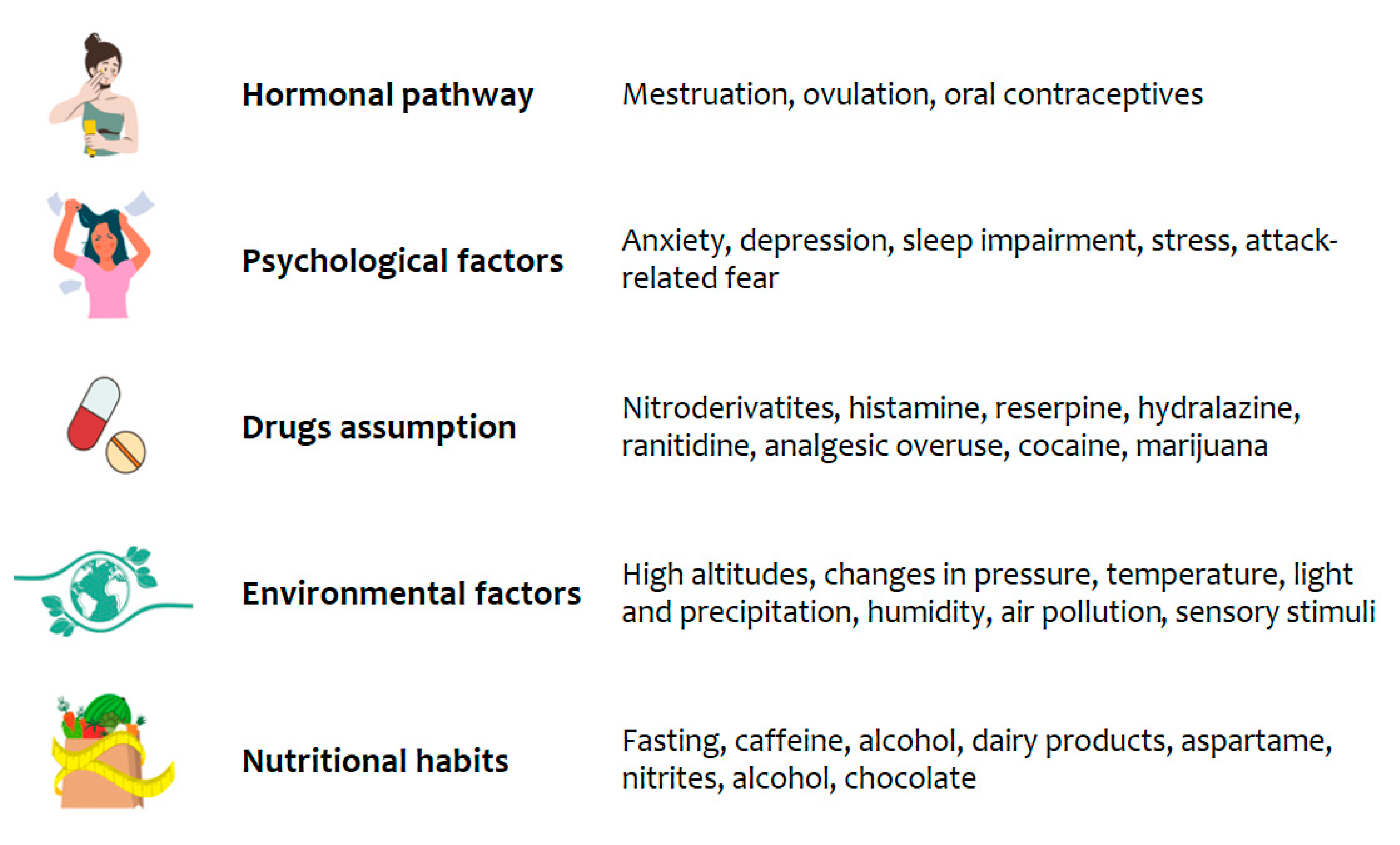

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

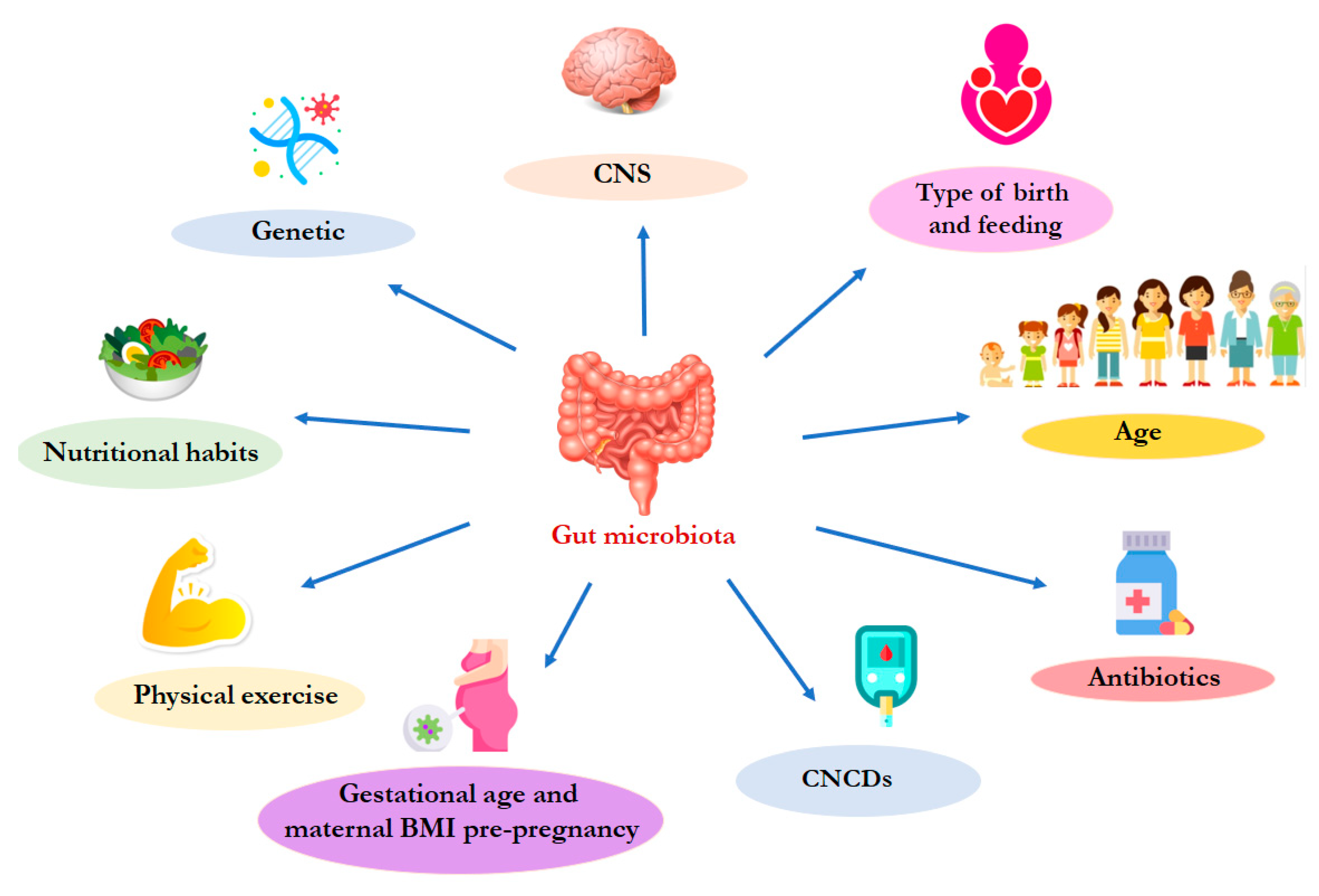

3. The gut microbiota physiological composition

4. Migraine and gut dysbiosis

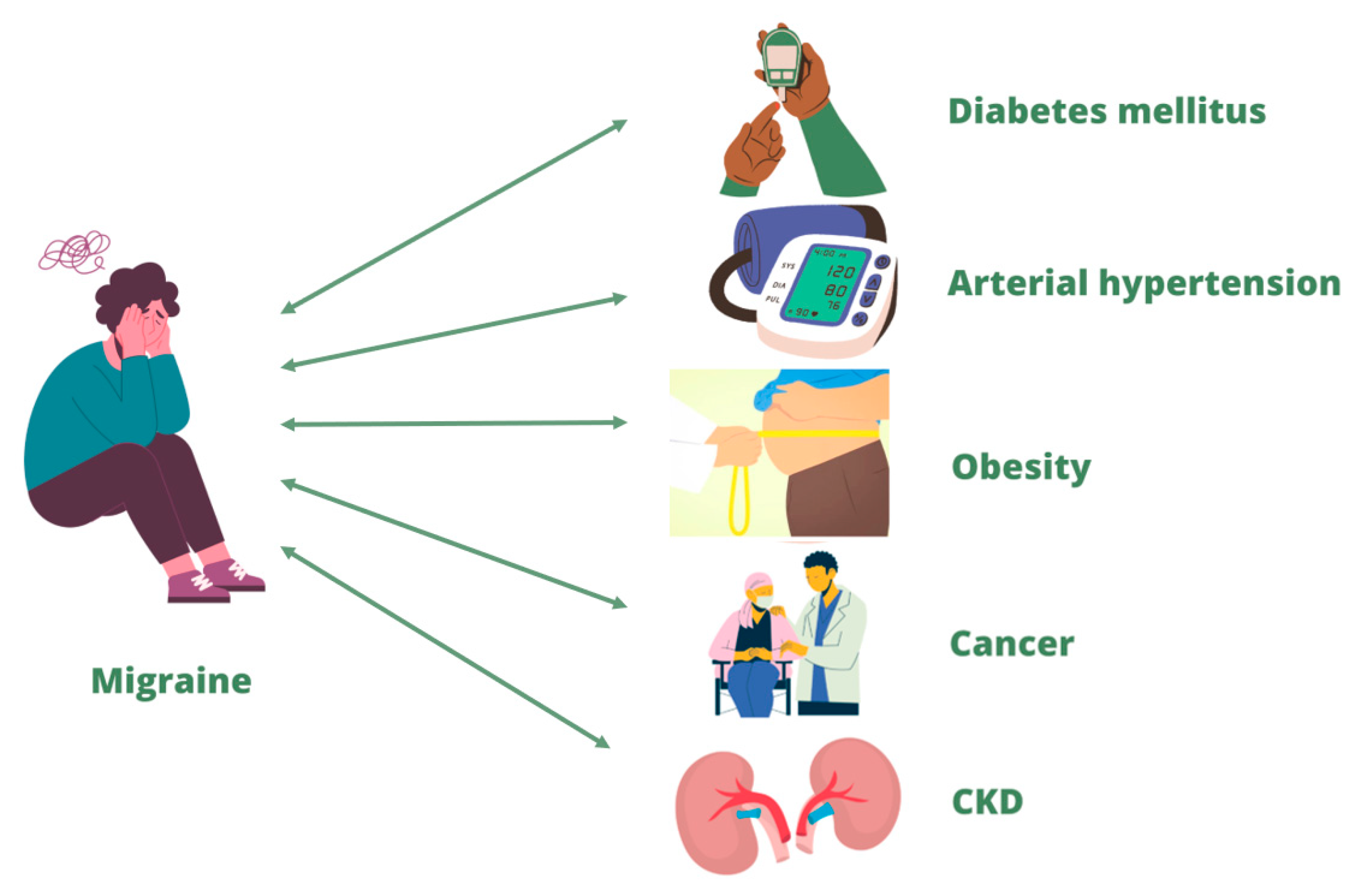

5. Migraine and its correlation with chronic non-communicable diseases

5.1. Diabetes mellitus and migraine

5.2. Arterial hypertension and migraine

5.3. Obesity and migraine

5.4. Cancer and migraine

5.5. CKD and migraine

6. Possible nutritional approaches and lifestyle changes to counteract migraine

6.1. Mediterranean Diet

6.2. The ketogenic diet

6.3. Probiotic and prebiotic supplementation

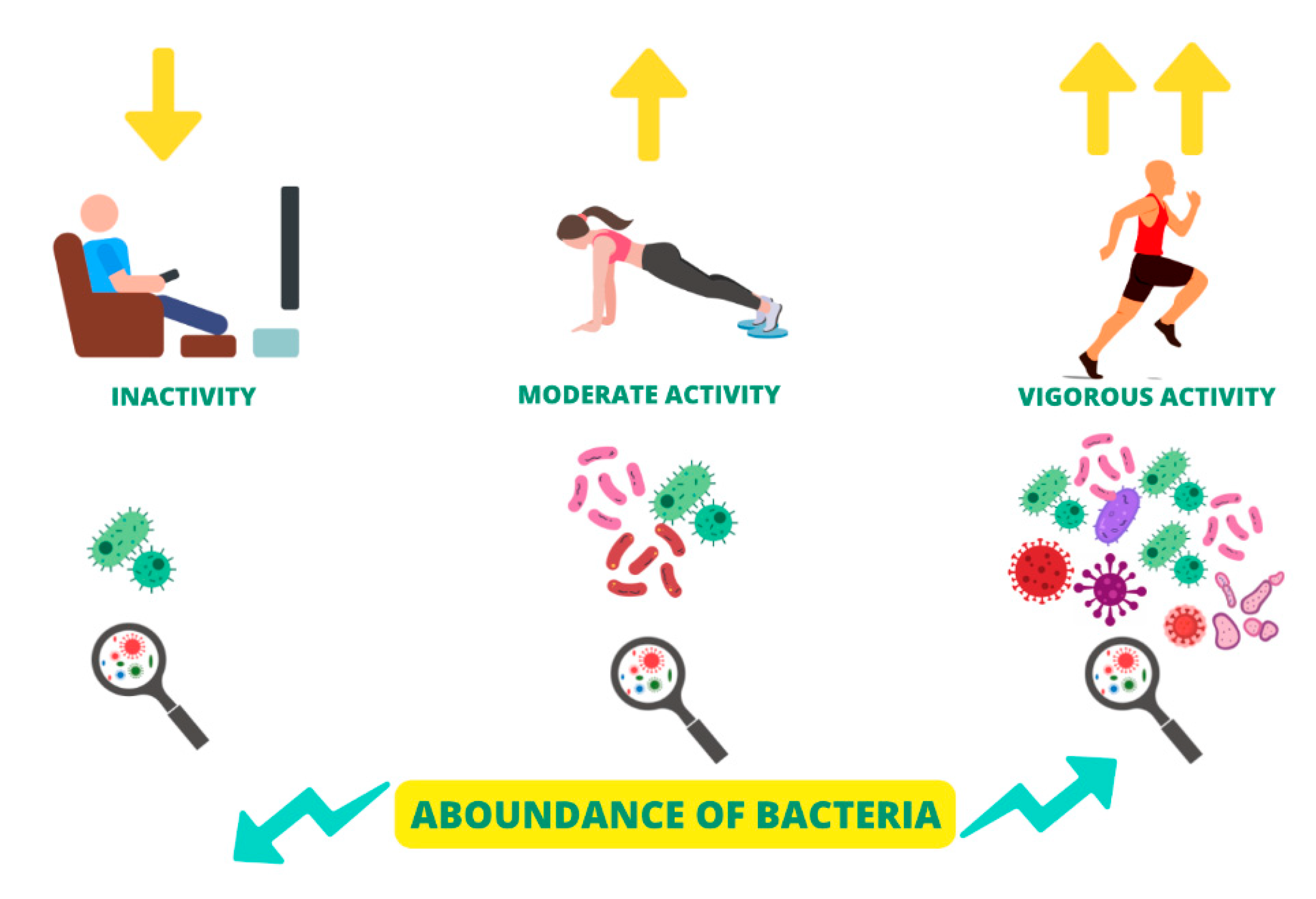

6.4. Physical activity

6.5. Vitamin D supplementation

6.6. Other vitamins supplementation

6.7. Iron supplementation

6.8. Polyphenol-rich foods assumption

6.9. Magnesium supplementation

6.10. Abstention from the histamine-rich foods consumption

7. Conclusions

Abbreviations

| 5-HT | 5-hydroxytryptamine |

| AH | Arterial Hypertension |

| BDNF | Brain Neurotrophic Factor |

| BMI | Body mass index |

| CGRP | calcitonin gene-related peptide |

| CKD | Chronic Kidney Disease |

| CNCDs | Chronic Non-Communicable Diseases |

| CNS | Central Nervous System |

| CV | Cardiovascular |

| DAO | Diaminossidase |

| DM | Dibetes Mellitus |

| ED | Endothelial Dysfunction |

| EPA | Aicosapentaenoic acid |

| EVOO | Extra Virgin Olive Oil |

| FOS | Fructooligosaccharides |

| GI | Gastrointestinal |

| GOS | Galactogosharides |

| HPA | Hypothalamic-Pituitary-Adrenal |

| IAA | Indole 3 Acetic Acid |

| IL | Interleukin |

| IS | Indoxyl Sulphate |

| KD | Ketogenic diet |

| MD | Mediteranean Diet |

| MUFAs | Monounsaturated Fat Acids |

| NF-κB | Kappa-B Nuclear Factor |

| NMDA | N-methyl-D-aspartic Acid |

| NO | Nitric Oxide |

| NSAIDs | Nonsteroidal Anti-Inflammatory Drugs |

| OS | Oxidative Stress |

| PUFAs | Polyunsaturated Fat Acids |

| RAAS | Renin- angiotensin- aldosterone system |

| RDA | Recommended Dietary Allowance |

| SCFAs | Short Chain Fatty Acids |

| TMAO | Trimethylamine N-Oxide |

| TNF | Tumor Necrosis Factor |

| WHO | World Health Organization |

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Burstein, R.; Noseda, R.; Borsook, D. Migraine: multiple processes, complex pathophysiology. J Neurosci 2015, 35, 6619–6629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stovner, L.J.; Hagen, K.; Linde, M.; Steiner, T.J. The global prevalence of headache: an update, with analysis of the influences of methodological factors on prevalence estimates. J Headache Pain 2022, 23, 34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Steiner, T.J.; Stovner, L.J.; Vos, T.; Jensen, R.; Katsarava, Z. Migraine is first cause of disability in under 50s: will health politicians now take notice? J Headache Pain 2018, 19, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cieza, A.; Causey, K.; Kamenov, K.; Hanson, S.W.; Chatterji, S.; Vos, T. Global estimates of the need for rehabilitation based on the Global Burden of Disease study 2019: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2019. Lancet 2021, 396, 2006–2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rossi, M.F.; Tumminello, A.; Marconi, M.; Gualano, M.R.; Santoro, P.E.; Malorni, W.; Moscato, U. Sex and gender differences in migraines: a narrative review. Neurol Sci 2022, 43, 5729–5734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sacco, S.; Lampl, C.; Maassen van den Brink, A.; Caponnetto, V.; Braschinsky, M.; Ducros, A.; Little, P.; Pozo-Rosich, P.; Reuter, U.; Ruiz de la Torre, E.; et al. Burden and attitude to resistant and refractory migraine: a survey from the European Headache Federation with the endorsement of the European Migraine & Headache Alliance. J Headache Pain 2021, 22, 39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tonini, M.C.; Fiorencis, A.; Iannacchero, R.; Zampolini, M.; Cappuccio, A.; Raddino, R.; Grillo, E.; Albanese, M.; Allais, G.; Bassano, M.A.; et al. Narrative Medicine to integrate patients', caregivers' and clinicians' migraine experiences: the DRONE multicentre project. Neurol Sci 2021, 42, 5277–5288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burch, R.C.; Buse, D.C.; Lipton, R.B. Migraine: Epidemiology, Burden, and Comorbidity. Neurol Clin 2019, 37, 631–649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paredes, S.; Cantillo, S.; Candido, K.D.; Knezevic, N.N. An Association of Serotonin with Pain Disorders and Its Modulation by Estrogens. Int J Mol Sci 2019, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calhoun, A.H.; Batur, P. Combined hormonal contraceptives and migraine: An update on the evidence. Cleve Clin J Med 2017, 84, 631–638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calhoun, A.H. Hormonal Contraceptives and Migraine With Aura-Is There Still a Risk? Headache 2017, 57, 184–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, A.; Syed, Y.Y. Estetrol/Drospirenone: A Review in Oral Contraception. Drugs 2022, 82, 1117–1125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gasparini, C.F.; Smith, R.A.; Griffiths, L.R. Genetic and biochemical changes of the serotonergic system in migraine pathobiology. J Headache Pain 2017, 18, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Q.; Shao, A.; Jiang, Z.; Tsai, H.; Liu, W. The exploration of mechanisms of comorbidity between migraine and depression. J Cell Mol Med 2019, 23, 4505–4513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peres, M.F.P.; Mercante, J.P.P.; Tobo, P.R.; Kamei, H.; Bigal, M.E. Anxiety and depression symptoms and migraine: a symptom-based approach research. J Headache Pain 2017, 18, 37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stubberud, A.; Buse, D.C.; Kristoffersen, E.S.; Linde, M.; Tronvik, E. Is there a causal relationship between stress and migraine? Current evidence and implications for management. J Headache Pain 2021, 22, 155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Radat, F. [Stress and migraine]. Rev Neurol (Paris) 2013, 169, 406–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Klan, T.; Diezemann-Prossdorf, A.; Guth, A.L.; Gaul, C.; Witthoft, M. [Fear of migraine attacks: diagnosis and treatment]. Schmerz 2023, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tepper, S.J. Medication-overuse headache. Continuum (Minneap Minn) 2012, 18, 807–822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tfelt-Hansen, P.C.; Tfelt-Hansen, J. Nitroglycerin headache and nitroglycerin-induced primary headaches from 1846 and onwards: a historical overview and an update. Headache 2009, 49, 445–456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lance, J.W. 5-Hydroxytryptamine and its role in migraine. Eur Neurol 1991, 31, 279–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Connor, J.P.; Stjepanovic, D.; Budney, A.J.; Le Foll, B.; Hall, W.D. Clinical management of cannabis withdrawal. Addiction 2022, 117, 2075–2095. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Farooque, U.; Okorie, N.; Kataria, S.; Shah, S.F.; Bollampally, V.C. Cocaine-Induced Headache: A Review of Pathogenesis, Presentation, Diagnosis, and Management. Cureus 2020, 12, e10128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Takahashi, T.T.; Ornello, R.; Quatrosi, G.; Torrente, A.; Albanese, M.; Vigneri, S.; Guglielmetti, M.; Maria De Marco, C.; Dutordoir, C.; Colangeli, E.; et al. Medication overuse and drug addiction: a narrative review from addiction perspective. J Headache Pain 2021, 22, 32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marmura, M.J. Triggers, Protectors, and Predictors in Episodic Migraine. Curr Pain Headache Rep 2018, 22, 81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Minen, M.T.; Begasse De Dhaem, O.; Kroon Van Diest, A.; Powers, S.; Schwedt, T.J.; Lipton, R.; Silbersweig, D. Migraine and its psychiatric comorbidities. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 2016, 87, 741–749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Noce, A.; Marchetti, M.; Marrone, G.; Di Renzo, L.; Di Lauro, M.; Di Daniele, F.; Albanese, M.; Di Daniele, N.; De Lorenzo, A. Link between gut microbiota dysbiosis and chronic kidney disease. Eur Rev Med Pharmacol Sci 2022, 26, 2057–2074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Noce, A.; Marrone, G.; Di Daniele, F.; Ottaviani, E.; Wilson Jones, G.; Bernini, R.; Romani, A.; Rovella, V. Impact of Gut Microbiota Composition on Onset and Progression of Chronic Non-Communicable Diseases. Nutrients 2019, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ceppa, F.A.; Izzo, L.; Sardelli, L.; Raimondi, I.; Tunesi, M.; Albani, D.; Giordano, C. Human Gut-Microbiota Interaction in Neurodegenerative Disorders and Current Engineered Tools for Its Modeling. Front Cell Infect Microbiol 2020, 10, 297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cryan, J.F.; O'Riordan, K.J.; Cowan, C.S.M.; Sandhu, K.V.; Bastiaanssen, T.F.S.; Boehme, M.; Codagnone, M.G.; Cussotto, S.; Fulling, C.; Golubeva, A.V.; et al. The Microbiota-Gut-Brain Axis. Physiol Rev 2019, 99, 1877–2013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matijasic, M.; Mestrovic, T.; Paljetak, H.C.; Peric, M.; Baresic, A.; Verbanac, D. Gut Microbiota beyond Bacteria-Mycobiome, Virome, Archaeome, and Eukaryotic Parasites in IBD. Int J Mol Sci 2020, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hills, R.D., Jr.; Pontefract, B.A.; Mishcon, H.R.; Black, C.A.; Sutton, S.C.; Theberge, C.R. Gut Microbiome: Profound Implications for Diet and Disease. Nutrients 2019, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gonzalez-Sarrias, A.; Romo-Vaquero, M.; Garcia-Villalba, R.; Cortes-Martin, A.; Selma, M.V.; Espin, J.C. The Endotoxemia Marker Lipopolysaccharide-Binding Protein is Reduced in Overweight-Obese Subjects Consuming Pomegranate Extract by Modulating the Gut Microbiota: A Randomized Clinical Trial. Mol Nutr Food Res 2018, 62, e1800160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bjorksten, B. The gut microbiota: a complex ecosystem. Clin Exp Allergy 2006, 36, 1215–1217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chakaroun, R.M.; Massier, L.; Kovacs, P. Gut Microbiome, Intestinal Permeability, and Tissue Bacteria in Metabolic Disease: Perpetrators or Bystanders? Nutrients 2020, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodriguez, J.M.; Murphy, K.; Stanton, C.; Ross, R.P.; Kober, O.I.; Juge, N.; Avershina, E.; Rudi, K.; Narbad, A.; Jenmalm, M.C.; et al. The composition of the gut microbiota throughout life, with an emphasis on early life. Microb Ecol Health Dis 2015, 26, 26050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thursby, E.; Juge, N. Introduction to the human gut microbiota. Biochem J 2017, 474, 1823–1836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mackowiak, P.A. Recycling metchnikoff: probiotics, the intestinal microbiome and the quest for long life. Front Public Health 2013, 1, 52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belkaid, Y.; Hand, T.W. Role of the microbiota in immunity and inflammation. Cell 2014, 157, 121–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rowland, I.; Gibson, G.; Heinken, A.; Scott, K.; Swann, J.; Thiele, I.; Tuohy, K. Gut microbiota functions: metabolism of nutrients and other food components. Eur J Nutr 2018, 57, 1–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, I. The gut-brain axis: historical reflections. Microb Ecol Health Dis 2018, 29, 1542921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, W.L.; Xu, S.Y.; Ren, Z.G.; Tao, L.; Jiang, J.W.; Zheng, S.S. Application of metagenomics in the human gut microbiome. World J Gastroenterol 2015, 21, 803–814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rinninella, E.; Raoul, P.; Cintoni, M.; Franceschi, F.; Miggiano, G.A.D.; Gasbarrini, A.; Mele, M.C. What is the Healthy Gut Microbiota Composition? A Changing Ecosystem across Age, Environment, Diet, and Diseases. Microorganisms 2019, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bull, M.J.; Plummer, N.T. Part 1: The Human Gut Microbiome in Health and Disease. Integr Med (Encinitas) 2014, 13, 17–22. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Walker, R.W.; Clemente, J.C.; Peter, I.; Loos, R.J.F. The prenatal gut microbiome: are we colonized with bacteria in utero? Pediatr Obes 2017, 12 Suppl 1, 3–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanaka, M.; Nakayama, J. Development of the gut microbiota in infancy and its impact on health in later life. Allergol Int 2017, 66, 515–522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nyangahu, D.D.; Jaspan, H.B. Influence of maternal microbiota during pregnancy on infant immunity. Clin Exp Immunol 2019, 198, 47–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Easton, Z.J.W.; Regnault, T.R.H. The Impact of Maternal Body Composition and Dietary Fat Consumption upon Placental Lipid Processing and Offspring Metabolic Health. Nutrients 2020, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kapoor, A.; Dunn, E.; Kostaki, A.; Andrews, M.H.; Matthews, S.G. Fetal programming of hypothalamo-pituitary-adrenal function: prenatal stress and glucocorticoids. J Physiol 2006, 572, 31–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arboleya, S.; Watkins, C.; Stanton, C.; Ross, R.P. Gut Bifidobacteria Populations in Human Health and Aging. Front Microbiol 2016, 7, 1204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manor, O.; Dai, C.L.; Kornilov, S.A.; Smith, B.; Price, N.D.; Lovejoy, J.C.; Gibbons, S.M.; Magis, A.T. Health and disease markers correlate with gut microbiome composition across thousands of people. Nat Commun 2020, 11, 5206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pickard, J.M.; Zeng, M.Y.; Caruso, R.; Nunez, G. Gut microbiota: Role in pathogen colonization, immune responses, and inflammatory disease. Immunol Rev 2017, 279, 70–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Conlon, M.A.; Bird, A.R. The impact of diet and lifestyle on gut microbiota and human health. Nutrients 2014, 7, 17–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Canale, M.P.; Noce, A.; Di Lauro, M.; Marrone, G.; Cantelmo, M.; Cardillo, C.; Federici, M.; Di Daniele, N.; Tesauro, M. Gut Dysbiosis and Western Diet in the Pathogenesis of Essential Arterial Hypertension: A Narrative Review. Nutrients 2021, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.; Jazwinski, S.M. The Gut Microbiota and Healthy Aging: A Mini-Review. Gerontology 2018, 64, 513–520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Salazar, N.; Arboleya, S.; Fernandez-Navarro, T.; de Los Reyes-Gavilan, C.G.; Gonzalez, S.; Gueimonde, M. Age-Associated Changes in Gut Microbiota and Dietary Components Related with the Immune System in Adulthood and Old Age: A Cross-Sectional Study. Nutrients 2019, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, X.; Liang, W.; Li, L.; Xiong, Q.; He, S.; Zhao, J.; Guo, X.; Xiang, S.; Zhang, P.; Wang, H.; et al. The Accumulation of Gut Microbiome-derived Indoxyl Sulfate and P-Cresyl Sulfate in Patients With End-stage Renal Disease. J Ren Nutr 2022, 32, 578–586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noce, A.; Marrone, G.; Ottaviani, E.; Guerriero, C.; Di Daniele, F.; Pietroboni Zaitseva, A.; Di Daniele, N. Uremic Sarcopenia and Its Possible Nutritional Approach. Nutrients 2021, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raspini, B.; Vacca, M.; Porri, D.; De Giuseppe, R.; Calabrese, F.M.; Chieppa, M.; Liso, M.; Cerbo, R.M.; Civardi, E.; Garofoli, F.; et al. Early Life Microbiota Colonization at Six Months of Age: A Transitional Time Point. Front Cell Infect Microbiol 2021, 11, 590202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, L.; Xiao, X. The role of gut microbiota in the effects of maternal obesity during pregnancy on offspring metabolism. Biosci Rep 2018, 38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fouhy, F.; Watkins, C.; Hill, C.J.; O'Shea, C.A.; Nagle, B.; Dempsey, E.M.; O'Toole, P.W.; Ross, R.P.; Ryan, C.A.; Stanton, C. Perinatal factors affect the gut microbiota up to four years after birth. Nat Commun 2019, 10, 1517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ramirez, J.; Guarner, F.; Bustos Fernandez, L.; Maruy, A.; Sdepanian, V.L.; Cohen, H. Antibiotics as Major Disruptors of Gut Microbiota. Front Cell Infect Microbiol 2020, 10, 572912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carabotti, M.; Scirocco, A.; Maselli, M.A.; Severi, C. The gut-brain axis: interactions between enteric microbiota, central and enteric nervous systems. Ann Gastroenterol 2015, 28, 203–209. [Google Scholar]

- Perez-Cobas, A.E.; Moya, A.; Gosalbes, M.J.; Latorre, A. Colonization Resistance of the Gut Microbiota against Clostridium difficile. Antibiotics (Basel) 2015, 4, 337–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Langdon, A.; Crook, N.; Dantas, G. The effects of antibiotics on the microbiome throughout development and alternative approaches for therapeutic modulation. Genome Med 2016, 8, 39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elvers, K.T.; Wilson, V.J.; Hammond, A.; Duncan, L.; Huntley, A.L.; Hay, A.D.; van der Werf, E.T. Antibiotic-induced changes in the human gut microbiota for the most commonly prescribed antibiotics in primary care in the UK: a systematic review. BMJ Open 2020, 10, e035677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coelho, G.D.P.; Ayres, L.F.A.; Barreto, D.S.; Henriques, B.D.; Prado, M.; Passos, C.M.D. Acquisition of microbiota according to the type of birth: an integrative review. Rev Lat Am Enfermagem 2021, 29, e3446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitchell, C.M.; Mazzoni, C.; Hogstrom, L.; Bryant, A.; Bergerat, A.; Cher, A.; Pochan, S.; Herman, P.; Carrigan, M.; Sharp, K.; et al. Delivery Mode Affects Stability of Early Infant Gut Microbiota. Cell Rep Med 2020, 1, 100156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, J.; Li, Z.; Zhang, W.; Zhang, C.; Zhang, Y.; Mei, H.; Zhuo, N.; Wang, H.; Wang, L.; Wu, D. Comparison of gut microbiota in exclusively breast-fed and formula-fed babies: a study of 91 term infants. Sci Rep 2020, 10, 15792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stanislawski, M.A.; Dabelea, D.; Wagner, B.D.; Sontag, M.K.; Lozupone, C.A.; Eggesbo, M. Pre-pregnancy weight, gestational weight gain, and the gut microbiota of mothers and their infants. Microbiome 2017, 5, 113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dorelli, B.; Galle, F.; De Vito, C.; Duranti, G.; Iachini, M.; Zaccarin, M.; Preziosi Standoli, J.; Ceci, R.; Romano, F.; Liguori, G.; et al. Can Physical Activity Influence Human Gut Microbiota Composition Independently of Diet? A Systematic Review. Nutrients 2021, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dziewiecka, H.; Buttar, H.S.; Kasperska, A.; Ostapiuk-Karolczuk, J.; Domagalska, M.; Cichon, J.; Skarpanska-Stejnborn, A. Physical activity induced alterations of gut microbiota in humans: a systematic review. BMC Sports Sci Med Rehabil 2022, 14, 122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Noce, A.; Tranchita, E.; Marrone, G.; Grazioli, E.; Di Lauro, M.; Murri, A.; Vanni, G.; Della Morte Canosci, D.; Di Daniele, N.; Parisi, A.; et al. The possible role of physical activity in the modulation of gut microbiota in chronic kidney disease and its impact on cardiovascular risk: a narrative review. Eur Rev Med Pharmacol Sci 2023, 27, 3733–3746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aragon-Vela, J.; Solis-Urra, P.; Ruiz-Ojeda, F.J.; Alvarez-Mercado, A.I.; Olivares-Arancibia, J.; Plaza-Diaz, J. Impact of Exercise on Gut Microbiota in Obesity. Nutrients 2021, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katzmarzyk, P.T. Physical activity, sedentary behavior, and health: paradigm paralysis or paradigm shift? Diabetes 2010, 59, 2717–2725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vijay, A.; Valdes, A.M. Role of the gut microbiome in chronic diseases: a narrative review. Eur J Clin Nutr 2022, 76, 489–501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ojeda, J.; Avila, A.; Vidal, P.M. Gut Microbiota Interaction with the Central Nervous System throughout Life. J Clin Med 2021, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin, C.R.; Osadchiy, V.; Kalani, A.; Mayer, E.A. The Brain-Gut-Microbiome Axis. Cell Mol Gastroenterol Hepatol 2018, 6, 133–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Novellino, F.; Sacca, V.; Donato, A.; Zaffino, P.; Spadea, M.F.; Vismara, M.; Arcidiacono, B.; Malara, N.; Presta, I.; Donato, G. Innate Immunity: A Common Denominator between Neurodegenerative and Neuropsychiatric Diseases. Int J Mol Sci 2020, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maiuolo, J.; Gliozzi, M.; Musolino, V.; Carresi, C.; Scarano, F.; Nucera, S.; Scicchitano, M.; Oppedisano, F.; Bosco, F.; Ruga, S.; et al. The Contribution of Gut Microbiota-Brain Axis in the Development of Brain Disorders. Front Neurosci 2021, 15, 616883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kappeter, A.; Sipos, D.; Varga, A.; Vigvari, S.; Halda-Kiss, B.; Peterfi, Z. Migraine as a Disease Associated with Dysbiosis and Possible Therapy with Fecal Microbiota Transplantation. Microorganisms 2023, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhu, X.; Han, Y.; Du, J.; Liu, R.; Jin, K.; Yi, W. Microbiota-gut-brain axis and the central nervous system. Oncotarget 2017, 8, 53829–53838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Socala, K.; Doboszewska, U.; Szopa, A.; Serefko, A.; Wlodarczyk, M.; Zielinska, A.; Poleszak, E.; Fichna, J.; Wlaz, P. The role of microbiota-gut-brain axis in neuropsychiatric and neurological disorders. Pharmacol Res 2021, 172, 105840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ochoa-Reparaz, J.; Kasper, L.H. The Second Brain: Is the Gut Microbiota a Link Between Obesity and Central Nervous System Disorders? Curr Obes Rep 2016, 5, 51–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hamel, E. Serotonin and migraine: biology and clinical implications. Cephalalgia 2007, 27, 1293–1300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deen, M.; Christensen, C.E.; Hougaard, A.; Hansen, H.D.; Knudsen, G.M.; Ashina, M. Serotonergic mechanisms in the migraine brain - a systematic review. Cephalalgia 2017, 37, 251–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferrari, M.D.; Goadsby, P.J.; Roon, K.I.; Lipton, R.B. Triptans (serotonin, 5-HT1B/1D agonists) in migraine: detailed results and methods of a meta-analysis of 53 trials. Cephalalgia 2002, 22, 633–658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heatley, R.V.; Denburg, J.A.; Bayer, N.; Bienenstock, J. Increased plasma histamine levels in migraine patients. Clin Allergy 1982, 12, 145–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Worm, J.; Falkenberg, K.; Olesen, J. Histamine and migraine revisited: mechanisms and possible drug targets. J Headache Pain 2019, 20, 30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, H.; Silberstein, S.D. Histamine and Migraine. Headache 2018, 58, 184–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aamodt, A.H.; Stovner, L.J.; Hagen, K.; Zwart, J.A. Comorbidity of headache and gastrointestinal complaints. The Head-HUNT Study. Cephalalgia 2008, 28, 144–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Camara-Lemarroy, C.R.; Rodriguez-Gutierrez, R.; Monreal-Robles, R.; Marfil-Rivera, A. Gastrointestinal disorders associated with migraine: A comprehensive review. World J Gastroenterol 2016, 22, 8149–8160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chang, F.Y.; Lu, C.L. Irritable bowel syndrome and migraine: bystanders or partners? J Neurogastroenterol Motil 2013, 19, 301–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zanos, T.P.; Silverman, H.A.; Levy, T.; Tsaava, T.; Battinelli, E.; Lorraine, P.W.; Ashe, J.M.; Chavan, S.S.; Tracey, K.J.; Bouton, C.E. Identification of cytokine-specific sensory neural signals by decoding murine vagus nerve activity. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2018, 115, E4843–E4852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cook, T.M.; Gavini, C.K.; Jesse, J.; Aubert, G.; Gornick, E.; Bonomo, R.; Gautron, L.; Layden, B.T.; Mansuy-Aubert, V. Vagal neuron expression of the microbiota-derived metabolite receptor, free fatty acid receptor (FFAR3), is necessary for normal feeding behavior. Mol Metab 2021, 54, 101350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Crawford, J.; Liu, S.; Tao, F. Gut microbiota and migraine. Neurobiol Pain 2022, 11, 100090. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tang, Y.; Liu, S.; Shu, H.; Yanagisawa, L.; Tao, F. Gut Microbiota Dysbiosis Enhances Migraine-Like Pain Via TNFalpha Upregulation. Mol Neurobiol 2020, 57, 461–468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- David, L.A.; Materna, A.C.; Friedman, J.; Campos-Baptista, M.I.; Blackburn, M.C.; Perrotta, A.; Erdman, S.E.; Alm, E.J. Host lifestyle affects human microbiota on daily timescales. Genome Biol 2014, 15, R89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, R.K.; Chang, H.W.; Yan, D.; Lee, K.M.; Ucmak, D.; Wong, K.; Abrouk, M.; Farahnik, B.; Nakamura, M.; Zhu, T.H.; et al. Influence of diet on the gut microbiome and implications for human health. J Transl Med 2017, 15, 73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramsden, C.E.; Zamora, D.; Faurot, K.R.; MacIntosh, B.; Horowitz, M.; Keyes, G.S.; Yuan, Z.X.; Miller, V.; Lynch, C.; Honvoh, G.; et al. Dietary alteration of n-3 and n-6 fatty acids for headache reduction in adults with migraine: randomized controlled trial. BMJ 2021, 374, n1448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haghighi, F.S.; Rahmanian, M.; Namiranian, N.; Arzaghi, S.M.; Dehghan, F.; Chavoshzade, F.; Sepehri, F. Migraine and type 2 diabetes; is there any association? J Diabetes Metab Disord 2015, 15, 37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lopez-de-Andres, A.; Luis Del Barrio, J.; Hernandez-Barrera, V.; de Miguel-Diez, J.; Jimenez-Trujillo, I.; Martinez-Huedo, M.A.; Jimenez-Garcia, R. Migraine in adults with diabetes; is there an association? Results of a population-based study. Diabetes Metab Syndr Obes 2018, 11, 367–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cheon, D.Y.; Han, K.; Yang, Y.S.; Kim, Y.; Lee, S.H.; Kim, C.; Sohn, J.H.; Oh, M.S.; Lee, B.C.; Lee, M.; et al. Associations between migraine and major cardiovascular events in type 2 diabetes mellitus. Cardiovasc Diabetol 2022, 21, 275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bhoi, S.K.; Kalita, J.; Misra, U.K. Metabolic syndrome and insulin resistance in migraine. J Headache Pain 2012, 13, 321–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, M.; Hussein, M.; Magdy, R.; Khamis, A.; Al-Azayem, S.A.; Othman, A.M.; Ahmed, A.; Osama, W. The potential impact of insulin resistance and metabolic syndrome on migraine headache characteristics. BMC Neurol 2022, 22, 422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hagen, K.; Asvold, B.O.; Midthjell, K.; Stovner, L.J.; Zwart, J.A.; Linde, M. Inverse relationship between type 1 diabetes mellitus and migraine. Data from the Nord-Trondelag Health Surveys 1995-1997 and 2006-2008. Cephalalgia 2018, 38, 417–426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Berge, L.I.; Riise, T.; Fasmer, O.B.; Hundal, O.; Oedegaard, K.J.; Midthjell, K.; Lund, A. Does diabetes have a protective effect on migraine? Epidemiology 2013, 24, 129–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aamodt, A.H.; Stovner, L.J.; Midthjell, K.; Hagen, K.; Zwart, J.A. Headache prevalence related to diabetes mellitus. The Head-HUNT study. Eur J Neurol 2007, 14, 738–744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fagherazzi, G.; El Fatouhi, D.; Fournier, A.; Gusto, G.; Mancini, F.R.; Balkau, B.; Boutron-Ruault, M.C.; Kurth, T.; Bonnet, F. Associations Between Migraine and Type 2 Diabetes in Women: Findings From the E3N Cohort Study. JAMA Neurol 2019, 76, 257–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Friedman, B.W.; Mistry, B.; West, J.R.; Wollowitz, A. The association between headache and elevated blood pressure among patients presenting to an ED. Am J Emerg Med 2014, 32, 976–981. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paolucci, M.; Altamura, C.; Vernieri, F. The Role of Endothelial Dysfunction in the Pathophysiology and Cerebrovascular Effects of Migraine: A Narrative Review. J Clin Neurol 2021, 17, 164–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tronvik, E.; Stovner, L.J.; Helde, G.; Sand, T.; Bovim, G. Prophylactic treatment of migraine with an angiotensin II receptor blocker: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA 2003, 289, 65–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mahmoud, A.N.; Mentias, A.; Elgendy, A.Y.; Qazi, A.; Barakat, A.F.; Saad, M.; Mohsen, A.; Abuzaid, A.; Mansoor, H.; Mojadidi, M.K.; et al. Migraine and the risk of cardiovascular and cerebrovascular events: a meta-analysis of 16 cohort studies including 1 152 407 subjects. BMJ Open 2018, 8, e020498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Olesen, J. The role of nitric oxide (NO) in migraine, tension-type headache and cluster headache. Pharmacol Ther 2008, 120, 157–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Entonen, A.H.; Suominen, S.B.; Sillanmaki, L.H.; Rautava, P.T.; Kauniskangas, K.; Mantyselka, P.T.; Sumanen, M.; Koskenvuo, M.J. Prevalent migraine as a predictor of incident hypertension. Eur J Public Health 2022, 32, 297–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gales, B.J.; Bailey, E.K.; Reed, A.N.; Gales, M.A. Angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors and angiotensin receptor blockers for the prevention of migraines. Ann Pharmacother 2010, 44, 360–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barbanti, P.; Aurilia, C.; Egeo, G.; Fofi, L. Hypertension as a risk factor for migraine chronification. Neurol Sci 2010, 31 Suppl 1, S41–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manna, P.; Jain, S.K. Obesity, Oxidative Stress, Adipose Tissue Dysfunction, and the Associated Health Risks: Causes and Therapeutic Strategies. Metab Syndr Relat Disord 2015, 13, 423–444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bleich, S.; Cutler, D.; Murray, C.; Adams, A. Why is the developed world obese? Annu Rev Public Health 2008, 29, 273–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gelaye, B.; Sacco, S.; Brown, W.J.; Nitchie, H.L.; Ornello, R.; Peterlin, B.L. Body composition status and the risk of migraine: A meta-analysis. Neurology 2017, 88, 1795–1804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arzani, M.; Jahromi, S.R.; Ghorbani, Z.; Vahabizad, F.; Martelletti, P.; Ghaemi, A.; Sacco, S.; Togha, M.; School of Advanced Studies of the European Headache, F. Gut-brain Axis and migraine headache: a comprehensive review. J Headache Pain 2020, 21, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Westgate, C.S.J.; Israelsen, I.M.E.; Jensen, R.H.; Eftekhari, S. Understanding the link between obesity and headache- with focus on migraine and idiopathic intracranial hypertension. J Headache Pain 2021, 22, 123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kany, S.; Vollrath, J.T.; Relja, B. Cytokines in Inflammatory Disease. Int J Mol Sci 2019, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, X.; Wang, M.; Li, S.; Zhang, Y. Migraine and breast cancer risk: a meta-analysis of observational studies based on MOOSE compliant. Medicine (Baltimore) 2016, 95, e4031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elser, H.; Skajaa, N.; Ehrenstein, V.; Fuglsang, C.H.; Farkas, D.K.; Sorensen, H.T. Cancer risk in patients with migraine: A population-based cohort study in Denmark. Headache 2022, 62, 57–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.H.; Sheu, J.J.; Lin, Y.C.; Lin, H.C. Association of migraines with brain tumors: a nationwide population-based study. J Headache Pain 2018, 19, 111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goldlust, S.A.; Graber, J.J.; Bossert, D.F.; Avila, E.K. Headache in patients with cancer. Curr Pain Headache Rep 2010, 14, 455–464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernstein, C.A. Evaluation of headache in patients with cancer. Cancer 2021, 127, 4368–4375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weng, S.C.; Wu, C.L.; Kor, C.T.; Chiu, P.F.; Wu, M.J.; Chang, C.C.; Tarng, D.C. Migraine and subsequent chronic kidney disease risk: a nationwide population-based cohort study. BMJ Open 2017, 7, e018483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W.; Zhang, L.; Yang, L.; Xiao, C.; Wu, X.; Yan, P.; Cui, H.; Yang, C.; Zhu, J.; Wu, X.; et al. Migraine, chronic kidney disease and kidney function: observational and genetic analyses. Hum Genet 2023. [CrossRef]

- Rahman, A.; Segasothy, M.; Samad, S.A.; Zulfiqar, A.; Rani, M. Analgesic use and chronic renal disease in patients with headache. Headache 1993, 33, 442–445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Headache Classification Committee of the International Headache Society (IHS) The International Classification of Headache Disorders, 3rd edition. Cephalalgia 2018, 38, 1–211. [CrossRef]

- Chhaya, K.T.; Mankad, S.; Shah, M.K.; Patel, M.; Desai, D.; Desai, S.D. Headache Associated with Hemodialysis in Patients with End-Stage Renal Disease in India: A Common Yet Overlooked Comorbidity. Ann Indian Acad Neurol 2022, 25, 82–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silberstein, S.D. Preventive Migraine Treatment. Continuum (Minneap Minn) 2015, 21, 973–989. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kesserwani, H. Migraine Triggers: An Overview of the Pharmacology, Biochemistry, Atmospherics, and Their Effects on Neural Networks. Cureus 2021, 13, e14243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gazerani, P. Migraine and Diet. Nutrients 2020, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bagdy, G.; Riba, P.; Kecskemeti, V.; Chase, D.; Juhasz, G. Headache-type adverse effects of NO donors: vasodilation and beyond. Br J Pharmacol 2010, 160, 20–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lacatusu, C.M.; Grigorescu, E.D.; Floria, M.; Onofriescu, A.; Mihai, B.M. The Mediterranean Diet: From an Environment-Driven Food Culture to an Emerging Medical Prescription. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2019, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aridi, Y.S.; Walker, J.L.; Roura, E.; Wright, O.R.L. Adherence to the Mediterranean Diet and Chronic Disease in Australia: National Nutrition and Physical Activity Survey Analysis. Nutrients 2020, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arab, A.; Khorvash, F.; Karimi, E.; Hadi, A.; Askari, G. Associations between adherence to Mediterranean dietary pattern and frequency, duration, and severity of migraine headache: A cross-sectional study. Nutr Neurosci 2023, 26, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sofi, F.; Abbate, R.; Gensini, G.F.; Casini, A. Accruing evidence on benefits of adherence to the Mediterranean diet on health: an updated systematic review and meta-analysis. Am J Clin Nutr 2010, 92, 1189–1196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alcalay, R.N.; Gu, Y.; Mejia-Santana, H.; Cote, L.; Marder, K.S.; Scarmeas, N. The association between Mediterranean diet adherence and Parkinson's disease. Mov Disord 2012, 27, 771–774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liperoti, R.; Landi, F.; Fusco, O.; Bernabei, R.; Onder, G. Omega-3 polyunsaturated fatty acids and depression: a review of the evidence. Curr Pharm Des 2009, 15, 4165–4172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liao, Y.; Xie, B.; Zhang, H.; He, Q.; Guo, L.; Subramanieapillai, M.; Fan, B.; Lu, C.; McIntyre, R.S. Efficacy of omega-3 PUFAs in depression: A meta-analysis. Transl Psychiatry 2019, 9, 190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tamir, H.; Mahadik, S.P.; Rapport, M.M. Fractionation of synaptic membranes with sodium diatrizoate. Anal Biochem 1976, 76, 634–647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azzini, E.; Polito, A.; Fumagalli, A.; Intorre, F.; Venneria, E.; Durazzo, A.; Zaccaria, M.; Ciarapica, D.; Foddai, M.S.; Mauro, B.; et al. Mediterranean Diet Effect: an Italian picture. Nutr J 2011, 10, 125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakirhan, H.; Yildiran, H.; Uyar Cankay, T. Associations between diet quality, DASH and Mediterranean dietary patterns and migraine characteristics. Nutr Neurosci 2022, 25, 2324–2334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghoreishy, S.M.; Askari, G.; Mohammadi, H.; Campbell, M.S.; Khorvash, F.; Arab, A. Associations between potential inflammatory properties of the diet and frequency, duration, and severity of migraine headaches: a cross-sectional study. Sci Rep 2022, 12, 2878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martins, L.B.; Braga Tibaes, J.R.; Dos Santos Rodrigues, A.M.; Hassanzadeh Keshteli, A.; Karam Vono, C.; Borges, E.B.J.; Horta, P.M.; Teixeira, A.L.; Matos Ferreira, A.V. The quality and inflammatory index of the diet of patients with migraine. Nutr Neurosci 2022, 25, 2092–2099. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Merra, G.; Noce, A.; Marrone, G.; Cintoni, M.; Tarsitano, M.G.; Capacci, A.; De Lorenzo, A. Influence of Mediterranean Diet on Human Gut Microbiota. Nutrients 2020, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D'Andrea Meira, I.; Romao, T.T.; Pires do Prado, H.J.; Kruger, L.T.; Pires, M.E.P.; da Conceicao, P.O. Ketogenic Diet and Epilepsy: What We Know So Far. Front Neurosci 2019, 13, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Longo, R.; Peri, C.; Cricri, D.; Coppi, L.; Caruso, D.; Mitro, N.; De Fabiani, E.; Crestani, M. Ketogenic Diet: A New Light Shining on Old but Gold Biochemistry. Nutrients 2019, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hall, K.D.; Chen, K.Y.; Guo, J.; Lam, Y.Y.; Leibel, R.L.; Mayer, L.E.; Reitman, M.L.; Rosenbaum, M.; Smith, S.R.; Walsh, B.T.; et al. Energy expenditure and body composition changes after an isocaloric ketogenic diet in overweight and obese men. Am J Clin Nutr 2016, 104, 324–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Koh, S.; Dupuis, N.; Auvin, S. Ketogenic diet and Neuroinflammation. Epilepsy Res 2020, 167, 106454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Greco, T.; Glenn, T.C.; Hovda, D.A.; Prins, M.L. Ketogenic diet decreases oxidative stress and improves mitochondrial respiratory complex activity. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab 2016, 36, 1603–1613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paoli, A.; Mancin, L.; Bianco, A.; Thomas, E.; Mota, J.F.; Piccini, F. Ketogenic Diet and Microbiota: Friends or Enemies? Genes (Basel) 2019, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borkum, J.M. Migraine Triggers and Oxidative Stress: A Narrative Review and Synthesis. Headache 2016, 56, 12–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, G. Integrating Pathophysiology in Migraine: Role of the Gut Microbiome and Melatonin. Curr Pharm Des 2019, 25, 3550–3562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Lorenzo, C.; Ballerini, G.; Barbanti, P.; Bernardini, A.; D'Arrigo, G.; Egeo, G.; Frediani, F.; Garbo, R.; Pierangeli, G.; Prudenzano, M.P.; et al. Applications of Ketogenic Diets in Patients with Headache: Clinical Recommendations. Nutrients 2021, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kechagia, M.; Basoulis, D.; Konstantopoulou, S.; Dimitriadi, D.; Gyftopoulou, K.; Skarmoutsou, N.; Fakiri, E.M. Health benefits of probiotics: a review. ISRN Nutr 2013, 2013, 481651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fijan, S. Microorganisms with claimed probiotic properties: an overview of recent literature. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2014, 11, 4745–4767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vlasova, A.N.; Kandasamy, S.; Chattha, K.S.; Rajashekara, G.; Saif, L.J. Comparison of probiotic lactobacilli and bifidobacteria effects, immune responses and rotavirus vaccines and infection in different host species. Vet Immunol Immunopathol 2016, 172, 72–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naghibi, M.M.; Day, R.; Stone, S.; Harper, A. Probiotics for the Prophylaxis of Migraine: A Systematic Review of Randomized Placebo Controlled Trials. J Clin Med 2019, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caetano, M.A.F.; Castelucci, P. Role of short chain fatty acids in gut health and possible therapeutic approaches in inflammatory bowel diseases. World J Clin Cases 2022, 10, 9985–10003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Hemert, S.; Breedveld, A.C.; Rovers, J.M.; Vermeiden, J.P.; Witteman, B.J.; Smits, M.G.; de Roos, N.M. Migraine associated with gastrointestinal disorders: review of the literature and clinical implications. Front Neurol 2014, 5, 241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hemarajata, P.; Versalovic, J. Effects of probiotics on gut microbiota: mechanisms of intestinal immunomodulation and neuromodulation. Therap Adv Gastroenterol 2013, 6, 39–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, Y.J.; Wang, H.Y.; Wang, X.J.; Kaye, A.D.; Sun, Y.H. Potential Beneficial Effects of Probiotics on Human Migraine Headache: A Literature Review. Pain Physician 2017, 20, E251–E255. [Google Scholar]

- Bedu-Ferrari, C.; Biscarrat, P.; Langella, P.; Cherbuy, C. Prebiotics and the Human Gut Microbiota: From Breakdown Mechanisms to the Impact on Metabolic Health. Nutrients 2022, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Macfarlane, G.T.; Steed, H.; Macfarlane, S. Bacterial metabolism and health-related effects of galacto-oligosaccharides and other prebiotics. J Appl Microbiol 2008, 104, 305–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Divyashri, G.; Sadanandan, B.; Chidambara Murthy, K.N.; Shetty, K.; Mamta, K. Neuroprotective Potential of Non-Digestible Oligosaccharides: An Overview of Experimental Evidence. Front Pharmacol 2021, 12, 712531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levine, E.S.; Crozier, R.A.; Black, I.B.; Plummer, M.R. Brain-derived neurotrophic factor modulates hippocampal synaptic transmission by increasing N-methyl-D-aspartic acid receptor activity. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 1998, 95, 10235–10239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bull, F.C.; Al-Ansari, S.S.; Biddle, S.; Borodulin, K.; Buman, M.P.; Cardon, G.; Carty, C.; Chaput, J.P.; Chastin, S.; Chou, R.; et al. World Health Organization 2020 guidelines on physical activity and sedentary behaviour. Br J Sports Med 2020, 54, 1451–1462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Warburton, D.E.; Nicol, C.W.; Bredin, S.S. Health benefits of physical activity: the evidence. CMAJ 2006, 174, 801–809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cerda, B.; Perez, M.; Perez-Santiago, J.D.; Tornero-Aguilera, J.F.; Gonzalez-Soltero, R.; Larrosa, M. Gut Microbiota Modification: Another Piece in the Puzzle of the Benefits of Physical Exercise in Health? Front Physiol 2016, 7, 51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Liu, Y.; Wang, X.; Zhang, X. Physical Exercise and Diet: Regulation of Gut Microbiota to Prevent and Treat Metabolic Disorders to Maintain Health. Nutrients 2023, 15, 1539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campaniello, D.; Corbo, M.R.; Sinigaglia, M.; Speranza, B.; Racioppo, A.; Altieri, C.; Bevilacqua, A. How Diet and Physical Activity Modulate Gut Microbiota: Evidence, and Perspectives. Nutrients 2022, 14, 2456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodrigues, S.; Silva, J.M.D.; Oliveira, M.C.C.; Santana, C.M.F.; Carvalho, K.M.; Barbosa, B. Physical exercise as a non-pharmacological strategy for reducing behavioral and psychological symptoms in elderly with mild cognitive impairment and dementia: a systematic review of randomized clinical trials. Arq Neuropsiquiatr 2021, 79, 1129–1137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mizutani, T.; Ishizaka, A.; Koga, M.; Tsutsumi, T.; Yotsuyanagi, H. Role of Microbiota in Viral Infections and Pathological Progression. Viruses 2022, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cataldi, S.; Bonavolonta, V.; Poli, L.; Clemente, F.M.; De Candia, M.; Carvutto, R.; Silva, A.F.; Badicu, G.; Greco, G.; Fischetti, F. The Relationship between Physical Activity, Physical Exercise, and Human Gut Microbiota in Healthy and Unhealthy Subjects: A Systematic Review. Biology (Basel) 2022, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, T.J.; Chu, M.K. Exercise in Treatment of Migraine Including Chronic Migraine. Curr Pain Headache Rep 2021, 25, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lippi, G.; Mattiuzzi, C.; Sanchis-Gomar, F. Physical exercise and migraine: for or against? Ann Transl Med 2018, 6, 181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Song, T.J.; Chu, M.K.; Sohn, J.H.; Ahn, H.Y.; Lee, S.H.; Cho, S.J. Effect of Vitamin D Deficiency on the Frequency of Headaches in Migraine. J Clin Neurol 2018, 14, 366–373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eyles, D.W. Vitamin D: Brain and Behavior. JBMR Plus 2021, 5, e10419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Das, S.; Hasan, M.M.; Mohsin, M.; Jeorge, D.H.; Rasul, M.G.; Khan, A.R.; Gazi, M.A.; Ahmed, T. Sunlight, dietary habits, genetic polymorphisms and vitamin D deficiency in urban and rural infants of Bangladesh. Sci Rep 2022, 12, 3623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amiri, P.; Kazeminasab, S.; Nejadghaderi, S.A.; Mohammadinasab, R.; Pourfathi, H.; Araj-Khodaei, M.; Sullman, M.J.M.; Kolahi, A.A.; Safiri, S. Migraine: A Review on Its History, Global Epidemiology, Risk Factors, and Comorbidities. Front Neurol 2021, 12, 800605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niu, P.P.; Wang, X.; Xu, Y.M. Higher Circulating Vitamin D Levels Are Associated With Decreased Migraine Risk: A Mendelian Randomization Study. Front Nutr 2022, 9, 907789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zandifar, A.; Masjedi, S.S.; Banihashemi, M.; Asgari, F.; Manouchehri, N.; Ebrahimi, H.; Haghdoost, F.; Saadatnia, M. Vitamin D status in migraine patients: a case-control study. Biomed Res Int 2014, 2014, 514782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Togha, M.; Razeghi Jahromi, S.; Ghorbani, Z.; Martami, F.; Seifishahpar, M. Serum Vitamin D Status in a Group of Migraine Patients Compared With Healthy Controls: A Case-Control Study. Headache 2018, 58, 1530–1540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Acharya, U.; Gau, J.T.; Horvath, W.; Ventura, P.; Hsueh, C.T.; Carlsen, W. Hemolysis and hyperhomocysteinemia caused by cobalamin deficiency: three case reports and review of the literature. J Hematol Oncol 2008, 1, 26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ustun Ozek, S. A study on the correlation between pain frequency and severity and vitamin B12 levels in episodic and chronic migraine. Arq Neuropsiquiatr 2022, 80, 586–592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D'Onofrio, F.; Raimo, S.; Spitaleri, D.; Casucci, G.; Bussone, G. Usefulness of nutraceuticals in migraine prophylaxis. Neurol Sci 2017, 38, 117–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Faraji, H.; Paknahad, Z.; Chitsaz, A. Dietary Intake of Thiamine in Migraine Patients and Healthy Subjects: a Case-Control Study. Clin Nutr Res 2018, 7, 40–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fila, M.; Chojnacki, C.; Chojnacki, J.; Blasiak, J. Nutrients to Improve Mitochondrial Function to Reduce Brain Energy Deficit and Oxidative Stress in Migraine. Nutrients 2021, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maresz, K. Growing Evidence of a Proven Mechanism Shows Vitamin K2 Can Impact Health Conditions Beyond Bone and Cardiovascular. Integr Med (Encinitas) 2021, 20, 34–38. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Abbaspour, N.; Hurrell, R.; Kelishadi, R. Review on iron and its importance for human health. J Res Med Sci 2014, 19, 164–174. [Google Scholar]

- Meng, S.H.; Zhou, H.B.; Li, X.; Wang, M.X.; Kang, L.X.; Fu, J.M.; Li, X.; Li, X.T.; Zhao, Y.S. Association Between Dietary Iron Intake and Serum Ferritin and Severe Headache or Migraine. Front Nutr 2021, 8, 685564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torres-Ferrus, M.; Ursitti, F.; Alpuente, A.; Brunello, F.; Chiappino, D.; de Vries, T.; Di Marco, S.; Ferlisi, S.; Guerritore, L.; Gonzalez-Garcia, N.; et al. From transformation to chronification of migraine: pathophysiological and clinical aspects. J Headache Pain 2020, 21, 42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.; Wang, D.; Wu, F.; Dong, Z.; Yu, S. Association between inflammatory potential of diet and self-reported severe headache or migraine: A cross-sectional study of the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey. Nutrition 2023, 113, 112098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pamuk, G.E.; Top, M.S.; Uyanik, M.S.; Koker, H.; Akker, M.; Ak, R.; Yurekli, O.A.; Celik, Y. Is iron-deficiency anemia associated with migraine? Is there a role for anxiety and depression? Wien Klin Wochenschr 2016, 128, 576–580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Landete, J.M. Updated knowledge about polyphenols: functions, bioavailability, metabolism, and health. Crit Rev Food Sci Nutr 2012, 52, 936–948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakirhan, H.; Pehlivan, M.; Uyar Cankay, T.; Kocak, M. Migraine severity, disability, and duration: Is a good diet quality, high intake of phytochemicals and polyphenols important? Front Nutr 2022, 9, 1041907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goschorska, M.; Gutowska, I.; Baranowska-Bosiacka, I.; Barczak, K.; Chlubek, D. The Use of Antioxidants in the Treatment of Migraine. Antioxidants (Basel) 2020, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nowaczewska, M.; Wicinski, M.; Kazmierczak, W.; Kazmierczak, H. To Eat or Not to Eat: A Review of the Relationship between Chocolate and Migraines. Nutrients 2020, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, S.H.; Wang, M.X.; Kang, L.X.; Fu, J.M.; Zhou, H.B.; Li, X.; Li, X.; Li, X.T.; Zhao, Y.S. Dietary Intake of Calcium and Magnesium in Relation to Severe Headache or Migraine. Front Nutr 2021, 8, 653765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Domitrz, I.; Cegielska, J. Magnesium as an Important Factor in the Pathogenesis and Treatment of Migraine-From Theory to Practice. Nutrients 2022, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamanaka, R.; Shindo, Y.; Oka, K. Magnesium Is a Key Player in Neuronal Maturation and Neuropathology. Int J Mol Sci 2019, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, K.; Wang, X.F.; Li, D.Y.; Chen, Y.C.; Zhao, L.J.; Liu, X.G.; Guo, Y.F.; Shen, J.; Lin, X.; Deng, J.; et al. The good, the bad, and the ugly of calcium supplementation: a review of calcium intake on human health. Clin Interv Aging 2018, 13, 2443–2452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schnedl, W.J.; Enko, D. Histamine Intolerance Originates in the Gut. Nutrients 2021, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Branco, A.; Yoshikawa, F.S.Y.; Pietrobon, A.J.; Sato, M.N. Role of Histamine in Modulating the Immune Response and Inflammation. Mediators Inflamm 2018, 2018, 9524075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costa, F.; Beltrami, E.; Mellone, S.; Sacchetti, S.; Boggio, E.; Gigliotti, C.L.; Stoppa, I.; Dianzani, U.; Rolla, R.; Giordano, M. Genes and Microbiota Interaction in Monogenic Autoimmune Disorders. Biomedicines 2023, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Durak-Dados, A.; Michalski, M.; Osek, J. Histamine and Other Biogenic Amines in Food. J Vet Res 2020, 64, 281–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Yu, Y.; Hou, L.; Yu, Y.; Wu, Y.; Wu, S.; He, Y.; Ge, Y.; Wei, Y.; Luo, Q.; et al. Association between dietary habits and the risk of migraine: a Mendelian randomization study. Front Nutr 2023, 10, 1123657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruiz-Capillas, C.; Herrero, A.M. Impact of Biogenic Amines on Food Quality and Safety. Foods 2019, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Izquierdo-Casas, J.; Comas-Baste, O.; Latorre-Moratalla, M.L.; Lorente-Gascon, M.; Duelo, A.; Soler-Singla, L.; Vidal-Carou, M.C. Diamine oxidase (DAO) supplement reduces headache in episodic migraine patients with DAO deficiency: A randomized double-blind trial. Clin Nutr 2019, 38, 152–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okutan, G.; Ruiz Casares, E.; Perucho Alcalde, T.; Sanchez Nino, G.M.; Penades, B.F.; Terren Lora, A.; Torrente Estringana, L.; Lopez Oliva, S.; San Mauro Martin, I. Prevalence of Genetic Diamine Oxidase (DAO) Deficiency in Female Patients with Fibromyalgia in Spain. Biomedicines 2023, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, R.W.; Chadwick, D.R.; Bott, T.; West, H.M.; Wilson, P.; Hodgins, G.R.; Snape, C.E.; Jones, D.L. Biochar application to temperate grasslands: challenges and opportunities for delivering multiple ecosystem services. Biochar 2023, 5, 33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Esposito, F.; Montuori, P.; Schettino, M.; Velotto, S.; Stasi, T.; Romano, R.; Cirillo, T. Level of Biogenic Amines in Red and White Wines, Dietary Exposure, and Histamine-Mediated Symptoms upon Wine Ingestion. Molecules 2019, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).