1. Introduction

Rasmussen was the first to propose a combination of resection and disconnection [

1] of the classical anatomical hemispherectomy for surgical treatment of hemispheric DRE. The purpose of performing a disconnection was to reduce surgical morbidity and above all the 35% risk of delayed superficial cerebral hemosiderosis, characterized by meningeal inflammation with macrophages filled with hemosiderin, subpial necrotic lesions and ependymitis [

1,

2,

3], while keeping the good seizure outcome (85% complete or nearly complete seizure freedom) of hemispherectomy. This new procedure was later named hemispherotomy (HST) by Delalande [

4].

HST can be described as a disconnection of the corona radiata and the internal capsule, the corpus callosum, the fornix, the intra-limbic and limbic gyri, the fronto-temporo-limbic connections and the anterior commissure [

5,

6,

7,

8,

9].

Several modifications of HST have been described: through anterior temporal lobectomy with peri-sylvian transcortical incision [

10], through a supra-insular window [

11,

12,

13] or vertically through the central cortex [

14,

15]. The latter, the vertical parasagittal HST (VPH), was described by Delalande and is characterized by a vertical disconnection with limited resection [

14]. This method rapidly became our way of performing an HST.

When we started to perform VPH, our main goal was not only to reduce the complications rate (particularly the rate of shunt placement (15%)) and mortality (3.6%)) [

14], but also to preserve as much as possible the lenticular nucleus by performing a disconnection under the insular cortex (sub-insular) [

14]. Our purpose in this paper is to report our experience trying to reach these goals.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Population and data collection

All the patients suffered from DRE, according to the international league against epilepsy (ILAE). Patients underwent a presurgical workup at the Saint-Luc University Hospital including video-EEG seizure recording in the epilepsy monitoring unit (EMU), high-resolution magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), fluorodeoxyglucose positron-emission tomography (FDG PET) and, if possible, a cognitive evaluation. Before surgery, all cases were discussed in our multidisciplinary meeting for DRE. Senior staff members of adult or pediatric neurology assessed post-operative follow-up. All relevant data pre, per and postoperatively were collected retrospectively from medical charts (

Table 2).

Epilepsy etiologies were classified as congenital (cortical dysplasia, hemimegalencephaly, Sturge-Weber syndrome), acquired (ischemic or hemorrhagic stroke, postoperative or post-traumatic encephalomalacia) and progressive (Rasmussen encephalitis).

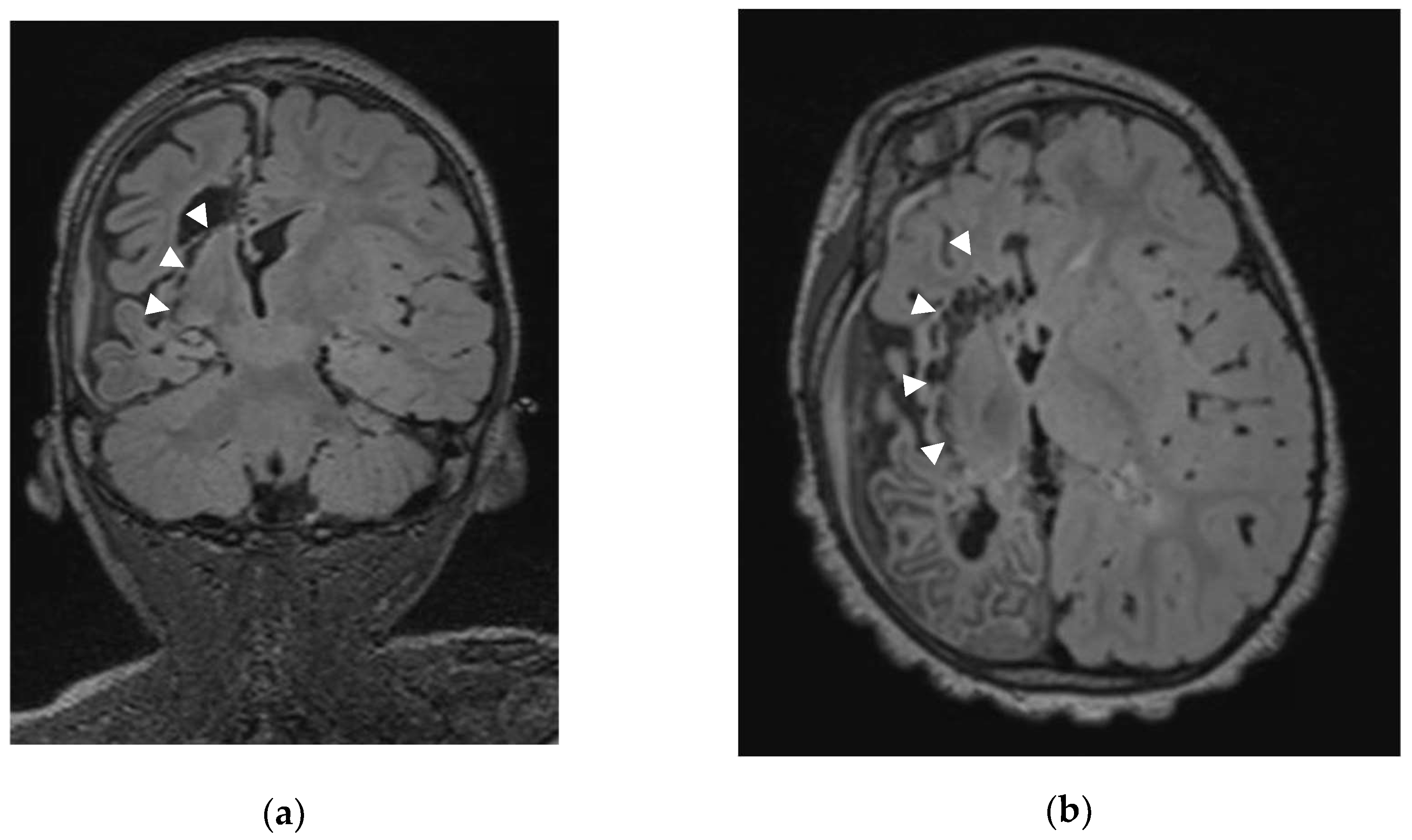

2.2. Sub-insular VPH method description

The senior author (CR) performed all surgeries. Our first sub-insular VPH was achieved in August 2008 implementing a series of modifications to the original Delalande VPH [

14] with the meaning of improving disconnection and preserving a maximum of lenticular connections. All surgeries were prepared on the BrainLab® neuronavigation software (Brainlab AG, Feldkirchen, Germany) using magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) acquired just before the surgery. All volumes of interest were identified: Trolard vein (superior anastomotic vein), the targeted ventricle, the pericallosal and anterior cerebral arteries, the homolateral optic nerve, the great cerebral vein of Galen, the homolateral lenticular nucleus (LN) and amygdala.

Surgery was always performed under general anesthesia. Our paramedian skin incision is centered slightly anterior to the coronal suture to avoid the Trolard vein.

After dural opening with maximal preservation of the bridging veins we perform, under the operative microscope, a minimal precentral parenchymal resection (pallium and body of corpus callosum; ≤ 20 mm by ≤ 10 mm). Once the ventricle body is opened and the interventricular foramen of Monro identified, we occlude it with a thin rectangular Gelfoam sponge (Pfizer Inc®, New York, USA) to avoid blood contamination of the distal ventricular system. Using the ultrasonic aspirator (CUSA Excel® Integra LifeSciences®, Princeton, New Jersey, USA) we perform the anterior corpus callosotomy (genu and rostrum) followed by a sub-rostral resection of the posterior part of the gyrus rectus, of the cingulum and posterior part of the Brodmann area 25. Our next step consists in the splenium disconnection down to the great cerebral vein of Galen. Then the ventricular trigone floor is disconnected; during that step, we disconnect not only the crus (posterior column) of fornix but also the intralimbic and limbic gyri up to reach the posterior part of the ambient cistern. Once this step is completed, we reach the posterior part of the temporal horn and perform the posterior-anterior sub-insular trans-claustral disconnection staying as much as possible lateral to the lenticular nucleus (

Figure 1).

We resect the piriform lobe and we end our hemispherotomy by extending our disconnection along the sylvian fissure until reaching the already resected subgenuorostrum area. At the end of the sub-insular VPH, we take the time to reach a perfect hemostasis before removing the Gelfoam plug from the foramen of Monro. A Gelfoam plug is placed in the cortical resection cavity and the dura, skull and skin are closed as usual.

The patient usually remains one day in the intensive care unit. Immediate postoperative imaging is not routinely performed and after approximatively one-week surveillance on the neuro-pediatric department, the patient is transferred to an associated institution (Centre Hospitalier Neurologique William Lennox) for rehabilitation and follow-up.

The principal differences between Delalande and Raftopoulos technique are shown in

Table 1.

2.3. Outcome

The Engel classification was used to assess the postoperative seizure outcome [

16].

2.4. Statistical analysis

Qualitative variables and quantitative variables were presented as number of patients, percentages and mean respectively. Statistical analysis was performed using GraphPad Prism 9. The result is considered significant when the p-value is less than or equal to 5% (p ≤ 0.05). A non-parametric Mann-Whitney test was done to compare the age variable in two populations: transfused and non-transfused patients. Data are represented as mean ± standard error of the mean (SEM). A Fisher's exact test was achieved to assess whether an APOS complication influences the Engel score.

2.5. Ethics

This study was approved by the Clinical Research Ethics Board of the Cliniques Universitaires Saint-Luc (CUSL).

3. Results

3.1. Demographic data and clinical findings

We report the first 25 consecutive patients suffering from hemispheric DRE who underwent modified sub-insular VPH by the senior author (CR) at the St Luc University Hospital. Mean age at seizure onset is 2.7-year-old (range: 0.0 – 9.6). Etiology was ischemic or hemorrhagic stroke in 13 patients (52%), Rasmussen syndrome in 4 (16%), cortical dysplasia in 2 (8%), hemimegalencephaly in 3 (12%), Sturge-Weber syndrome in 1 (4%) and gliosis after trauma or tumor resection in 2 (8%). (

Table 2)

Table 2.

Preoperative data.

Table 2.

Preoperative data.

| |

Overall (25)

No of patients (%) or mean |

| Age at |

|

| Onset |

2.7 |

| Surgery |

7.3 |

| Gender M/F |

14/11 |

| Etiology |

|

| Congenital |

6 (24%) |

| Cortical dysplasia |

2 (8%) |

| Hemimegalencephaly |

3 (12%) |

| Sturge-Weber |

1 (4%) |

| Acquired |

16 (64%) |

| Stroke (ischemic/hemorrhagic) |

13 (52%) |

| Posttraumatic |

1 (4%) |

| Gliosis (post-tumor resection) |

1 (4%) |

| Progressive (Rasmussen) |

4 (16%) |

| Hemispherotomy side (R/L) |

17/8 |

3.1.1. Medical history

Four patients had experienced previous brain surgery. Patient 5 had a decompressive craniectomy after trauma in another hospital. Patient 7 had four epilepsy surgeries with the last procedure being a peri-sylvian HST and ventriculo-peritoneal shunt (VPS) abroad without seizures improvement. Patient 11 underwent drainage of intra-ventricular hemorrhage (HIV) grade 4 with intraparenchymal hematoma (HIP). Patient 15 had already a callosotomy by the senior author (CR) without seizures reduction.

All patients displayed hemiparesis or hemiplegia before surgery without useful hand function. All evaluable patients presented with at least moderate development delay.

3.2. Surgical procedure and postoperative course

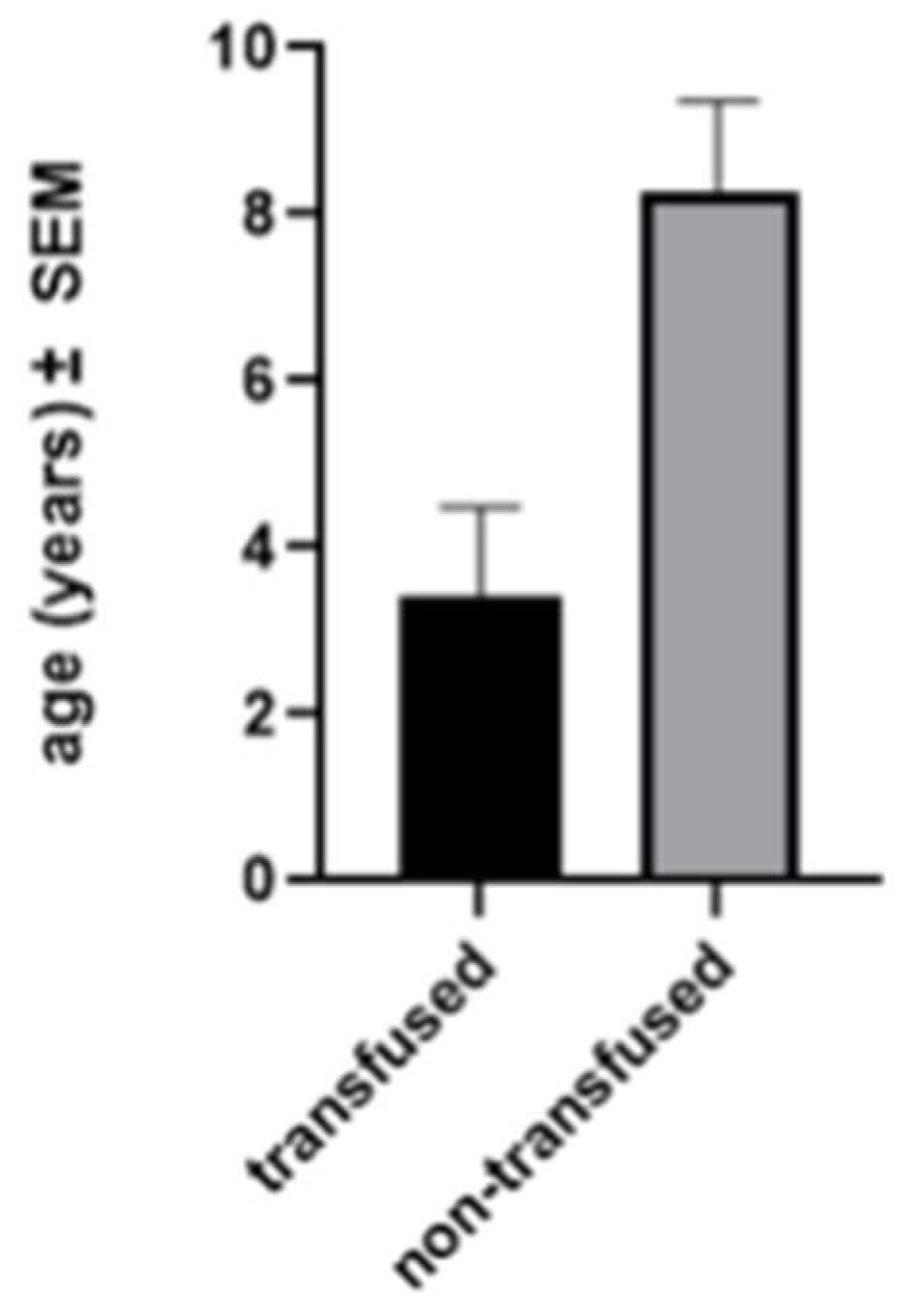

Mean age at sub-insular VPH was 7.3 years (range: 0.16 – 22.1). Seventeen (68%) surgeries were performed on the right hemisphere. No intra-operative complication and no mortality occurred. Five (20.8%) patients needed a blood transfusion during surgery or immediately after it (average: 123 ml). The need for blood transfusion was related to younger age (

Figure 2).

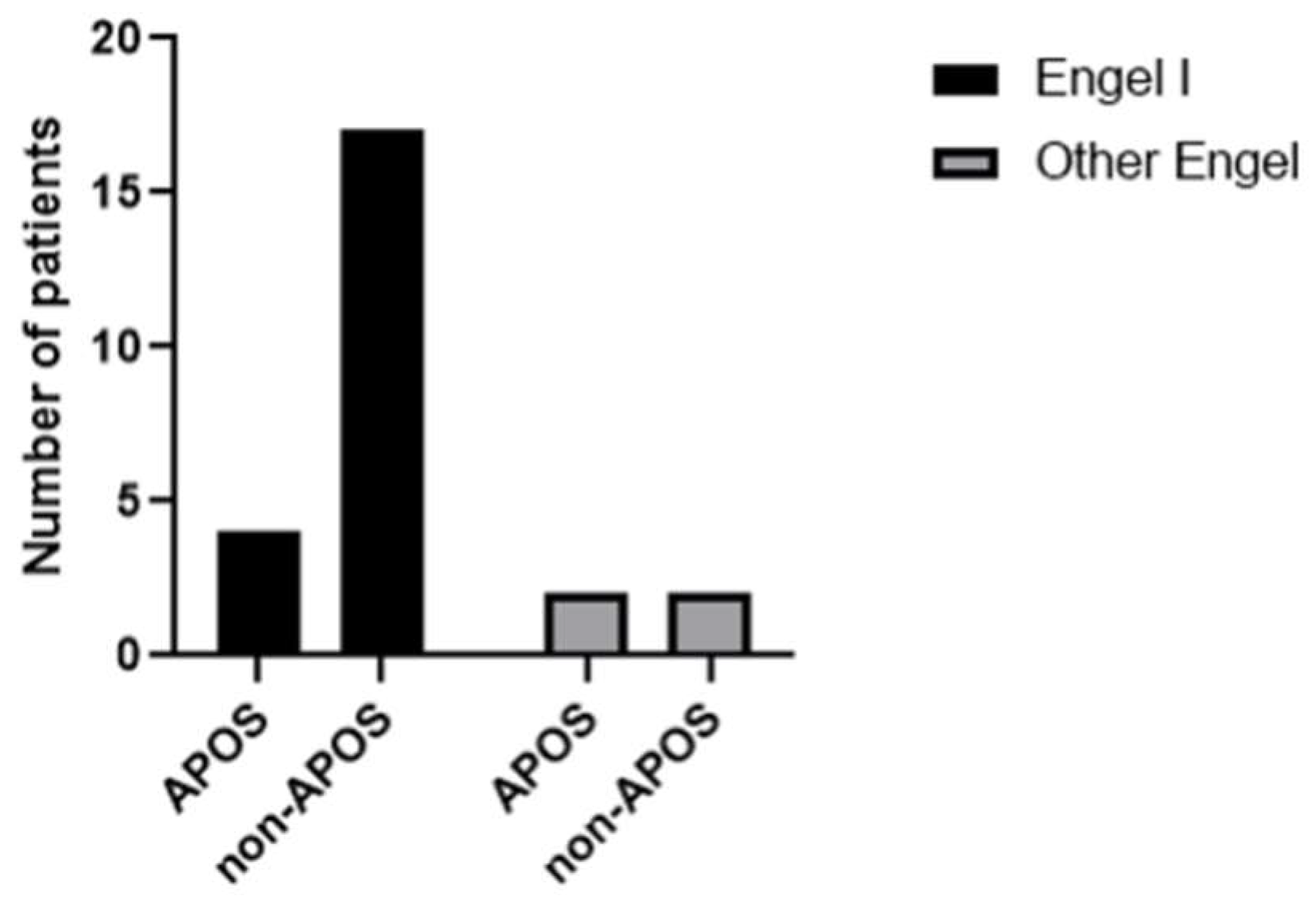

3.2.1. Acute postoperative seizures

Six (24%) patients experienced postoperative seizures within the first week (acute postoperative seizure or APOS). Nevertheless, four of them achieved prolonged seizure freedom (Engel I). The two others (patient 3 and 24) needed a second surgery for completion of the hemispherotomy and were not seizure free at last FUp. We found no link between the presence of APOS and the risk of not being seizure free (

Figure 3).

3.2.2. Hydrocephalus and shunting

No patient required a shunt during the first postoperative week. Two patients (9%) developed a delayed hydrocephalus requiring a shunt at one (patient 5) and three (patient 20) months postoperatively. Patient 3 underwent kysto-peritoneal shunt placement during her second hemispherotomy procedure for a persistent subdural hygroma without hydrocephalus. Patient 15 needed a VPS for treatment of recurrent pseudo-meningocele.

3.3. Seizure outcome

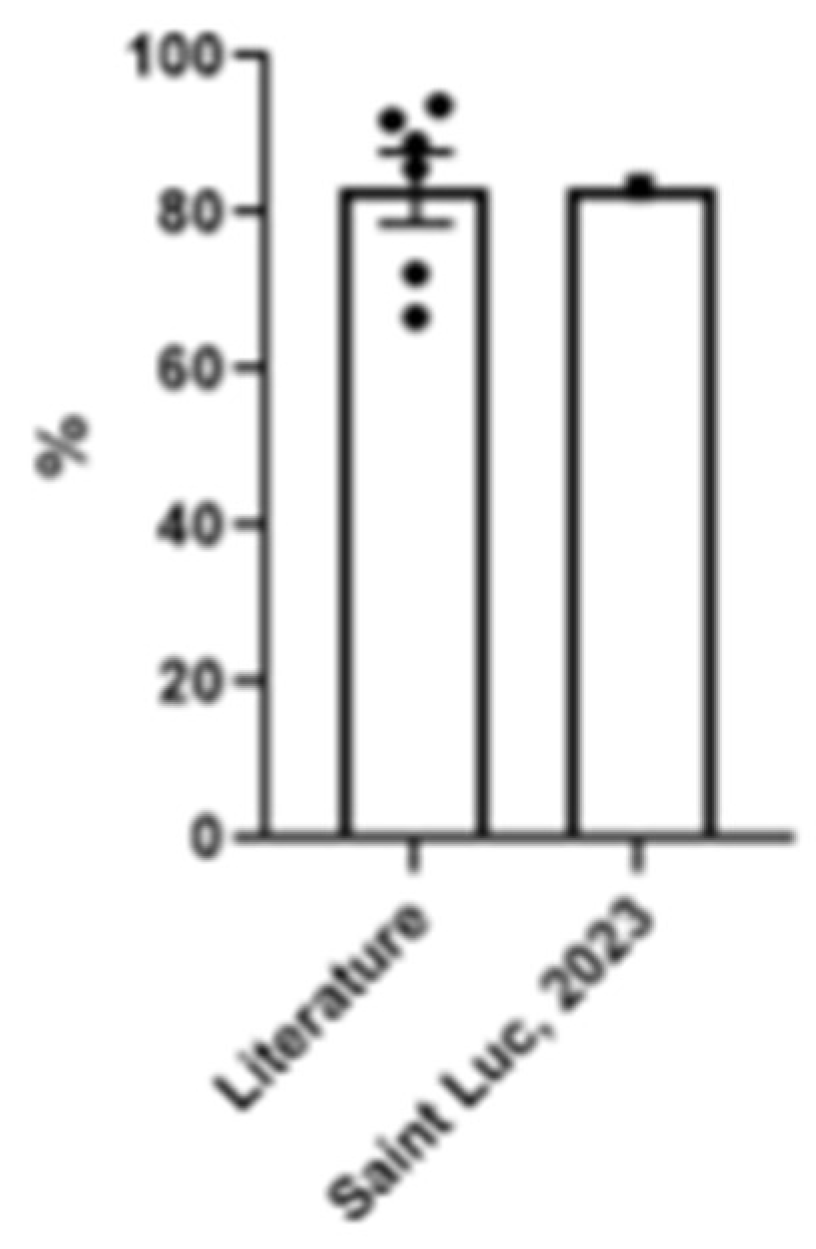

Our mean follow-up is 6.5 years (range: 0.08 – 11.7). 23 patients had at least a 3-months of follow-up (FUp) of those 20 (86.3%) are Engel 1 at last FUp.

1. Patient 3, suffering from Rasmussen encephalitis, was seizure free for 10 months after first VPH before recurrence of catastrophic status epilepticus. Postoperative MRI shown suspected persistence of callosal connection. We performed a second surgery for completion of the hemispherotomy. Unfortunately, she did not experience seizure improvement despite radiological confirmation of complete disconnection.

2. Patient 5 developed epilepsy after severe head trauma that required decompressive craniectomy. He was seizure free during two years after VPH and then presented recurrent spasms despite complete disconnection on MRI.

3. Patient 10 still suffered from morpheic seizures after surgery, but her last video-EEG showed a bilateralization of the epileptic foci.

Three other patients needed revision surgery for persistent or recurrent seizures. Patients 14 and 16 presented seizure recurrence with predominantly vegetative symptoms and had an amygdala residue resection: they are currently seizure free [

17].

Patient 24 (who was not taken into account in the analysis of long-term results) needed a second surgery for persistent infantile spasm. Postoperative MRI suspected persistence of callosal connection at the genu. He underwent a second surgery for completion of callosotomy and amygdalo-hippocampectomy but despite worthwhile seizure improvement, he was not seizure free one month after this procedure.

| Case No |

Sex |

Age at (y) |

Side |

Etiology |

Complications |

2nd surgery |

FUp (y) |

mRS |

Sz outcome (Engel) |

| Onset |

Surgery |

Cong |

Ac |

Prog |

BTF (ml) |

HCP |

APOS |

AF |

| 1 |

F |

6,6 |

6,8 |

R |

|

|

+ |

0 |

- |

|

+ |

|

14,91 |

1 |

I |

| 2 |

M |

7,4 |

8,9 |

R |

|

+ |

|

0 |

- |

+ |

- |

|

13,59 |

1 |

I |

| 3 |

F |

3,2 |

5,7 |

R |

|

|

+ |

100 |

- |

+ |

+ |

+ |

11,77 |

5 |

IV |

| 4 |

M |

0 |

6,8 |

L |

|

+ |

|

0 |

- |

|

- |

|

9,72 |

2 |

I |

| 5 |

M |

9,6 |

12,7 |

R |

|

+ |

|

0 |

+ |

|

+ |

|

9,96 |

3 |

II |

| 6 |

M |

3,2 |

5,5 |

R |

+ |

|

|

0 |

- |

|

- |

|

7,32 |

3 |

I |

| 7 |

M |

0,1 |

12,8 |

R |

+ |

|

|

0 |

- |

|

- |

|

10,04 |

3 |

I |

| 8 |

M |

1 |

22,1 |

L |

|

+ |

|

0 |

- |

+ |

- |

|

9,71 |

3 |

I |

| 9 |

M |

1,8 |

10 |

R |

|

+ |

|

0 |

- |

|

+ |

|

7,74 |

3 |

I |

| 10 |

F |

3 |

15,8 |

L |

|

+ |

|

0 |

- |

|

+ |

|

4,49 |

NA |

II |

| 11 |

F |

0,3 |

9,7 |

R |

|

+ |

|

0 |

- |

|

- |

|

7,6 |

3 |

I |

| 12 |

F |

1,5 |

4,9 |

L |

|

+ |

|

180 |

- |

|

+ |

|

7,02 |

2 |

I |

| 13 |

M |

3 |

5,5 |

L |

|

+ |

|

0 |

- |

|

+ |

|

6,86 |

3 |

I |

| 14 |

F |

3,7 |

4,2 |

R |

|

|

+ |

0 |

+ |

|

- |

+ |

6,2 |

2 |

I |

| 15 |

M |

1,3 |

6,9 |

R |

|

+ |

|

0 |

- |

|

- |

|

4,31 |

3 |

I |

| 16 |

F |

6 |

7,4 |

R |

|

|

+ |

0 |

- |

|

- |

+ |

5,15 |

2 |

I |

| 17 |

F |

4,6 |

5,5 |

R |

|

+ |

|

0 |

- |

|

+ |

|

4,6 |

3 |

I |

| 18 |

M |

0,3 |

1,5 |

L |

+ |

|

|

90 |

- |

|

- |

|

4,95 |

3 |

I |

| 19 |

M |

0 |

1,6 |

R |

+ |

|

|

0 |

- |

+ |

+ |

|

4,93 |

4 |

I |

| 20 |

F |

3 |

4,8 |

L |

|

+ |

|

+ |

- |

|

+ |

|

4,82 |

4 |

I |

| 21 |

F |

0,17 |

2,38 |

R |

+ |

|

|

0 |

- |

|

- |

|

3,95 |

2 |

I |

| 22 |

M |

0,75 |

7,19 |

R |

|

+ |

|

0 |

- |

|

- |

|

3,33 |

3 |

I |

| 23 |

F |

5,98 |

10,51 |

L |

|

+ |

|

0 |

- |

|

+ |

|

0,32 |

3 |

I |

| 24 |

M |

0 |

0,16 |

R |

+ |

|

|

100 |

- |

+ |

- |

+ |

0,16 |

NA |

III |

| 25 |

M |

0,5 |

3,28 |

R |

|

+ |

|

0 |

- |

+ |

- |

|

0,08 |

4 |

I |

| M/F |

1,27 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Mean |

|

2,68 |

7,3048 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

6,5448 |

2,826086957 |

|

| Range |

|

9.6 - 0 |

22.1 - 0,16 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

14,9-0,08 |

|

|

| Cong, congenital; Ac, acquired; Prog, progressive; BTF, blood transfusion; HCP, hydrocephalus; APOS, acute postoperative seizure; AF, aseptic fever; FUp, follow-up; mRS, modified Rankin scale; Sz, seizure; NA, not available/not applicable; Second surgeries (3, completion of VPH and KPS, 14, amygdalohippocampectomy; 16, amygdalohippocampectomy; 24, amygdalohippocampectomy and completion of callosotomy) |

3.4. Cognitive outcome

Six patients (26%) had significant cognitive impairment at last follow-up, with no possibility of social integration. Patient 3 was bedridden since seizure recurrence 10 months after first VPH with uncontrolled epilepsy and this despite two VPH for Rasmussen's encephalitis. Patient 5 was able to walk but had severe pre-operative cognitive impairment due to severe head trauma responsible for the onset of his epilepsy. Patient 7 had severe cognitive impairment as part of extensive cortical dysplasia with refractory epilepsy and encephalopathy for 10 years prior to surgery.

Patient 8 underwent surgery at the age of 22 with already a severe cognitive impairment in the context of refractory epilepsy since birth. Patient 19 presented with a global developmental delay, already suspected before surgery, in the context of his hemimegalencephaly, despite excellent control of his epilepsy. Finally, patient 20 exhibit preoperative hemiplegia and severe preoperative congenital delay in the setting of a pre-natal left ischemic stroke. She is currently able to communicate but is unable to walk unassisted due to her persistent motor deficit.

All the other patients were able to attend a normal school, or one adapted for their motor deficit. Patients 1 and 2 have a driver's license and have completed university studies. Unfortunately, a quantitative assessment of the developmental quotients was not possible due to the absence of pre- or post-operative assessment based on quantitative scales.

4. Discussion

4.1. Elegance of the vertical parasagittal HST (VPH)

VPH allows complete disconnection of one hemisphere with minimal brain resection and without dissection of the Sylvian fissure, resection of the insula or vessel sacrifice [

12]. VPH grants a complete insular cortex disconnection avoiding potential poor postoperative outcome due to residual connected insular cortex as reported by Bulteau et al [

18] in cases of functional hemispherectomy. This complex procedure addressing one whole hemisphere is carried out through a limited paramedian precentral cortical resection and through one ventricle with an extended view and understanding of the prosencephalic (forebrain) anatomy.

4.2. Gelfoam plug into the foramen of Monro

The range of postoperative shunt varies between 2.5% and 21.1% [

19]. In their series of 83 cases of VPH, Delalande et al reported 16% shunt placement [

14], with an incidence of 76.9% in the hemimegalencephaly group without well identified reason. In our three cases with hemimegalencephaly no hydrocephalus developed. A similar rate of 13% is met with lateral HST [

20].

In both vertical and lateral approach, shunt dependency is probably related to blood contamination of the CSF with inflammation of the subarachnoid spaces and arachnoid villi [

21] and to the initial volume of the ventricular system (smaller the ventricular system higher the risk of ventricular synechia). We favored the CSF blood contamination hypothesis and thus decided to protect the third ventricle and the rest of the ventricular system by occluding the homolateral foramen of Monro with a thin piece of Gelfoam sponge. This plug is removed at the very end of surgery when the hemostasis is complete and the operative field perfectly clean. This strategy seems to have played a role in reducing the rate hydrocephalus to 8,7%. Moreover, we have no case of acute hydrocephalus, which is potentially more dangerous. It would be interesting to know if this measureis used in other series with a low rate of postoperative shunt.

4.3. Sub-insular disconnection with lenticular nucleus (LN) preservation

The physiology of the LN, i.e., the putamen and the globus pallidum, is significant in many aspects: motor adjustment and skill acquisition [

22,

23], habit memory [

24] and cognitive functions [

25]. Decrease of N-acetyl aspartate/creatine ratios in both LN in patients with bipolar disorder was reported by Lai et al [

26] stressing the role of LN in mood behavior. Abnormalities of the LN microstructure in patients with schizophrenia were also observed [

27]. The LN has multiple connections not only with the cortex, which is disconnected by the VPH, but also with the thalamus, the habenula and the brainstem. Keeping the LN intact as much as possible preserves part of these connections and their role.

Nevertheless, the clinical impact of keeping the LN intact is currently unknown. Postoperative walking is irregularly reported in the literature between 33 and 100%, with great variability depending on the etiology of the epilepsy and the length of follow-up [

4,

28,

29,

30]. 86.9% of our patients were able to walk independently at the last follow-up and 100% of those who walked preoperatively. 74% of them were also able to follow a conventional education program with adaptations related to the loss of dexterity of the paretic hand. In patients with a bad functional status at last FUp, severe preoperative involvement, longer duration of epilepsy and underlying pathology (Rasmussen encephalopathy, hemimegalencephaly ...) are probably partly responsible for the poorer outcome. [9,18] Due to the small number of patients, it was not possible to demonstrate a statistically significant relationship between epilepsy etiology and functional outcome in our series.

The importance of keeping the LN intact as much as possible should be explored and analyzed on a large series with a long-term follow-up.

4.5. Acute postoperative seizures (APOS)

The definition of APOS has evolved with time and their influence on prognosis is still unclear. In 1963, Falconer et al reported neighborhood fits in the first postoperative month without worse prognosis [

32]. In 1991 and later, the frame of 7 days was used and considered as negative for showing prolonged seizure freedom [

33,

34,

35]. In 2001, the Commission on Neurosurgery of the ILAE definition recommended using a period of one month and considered APOS not to have a negative prognostic value [

36].

During the first postoperative month after surgery for DRE, 25% of children may show an APOS [

37]. In their series of HST, Panigrahi et al [

38] described a 25% rate of APOS while their rate of seizure freedom (Engel I) at last follow up was 94%, the highest in the literature.

On the other hand, in their multicenter series De Palma [

19]

et al showed the presence of APOS as the only significant association with poor seizure outcome and numerous studies have shown a correlation between early postoperative seizures and poor outcomes [

35,

39,

40,

41].

In our series, 66.6% of patients presenting APOS were seizure free (Engel I) at last follow up. There was no statistically significant correlation between the presence of APOS and the risk of not being seizure free. However, because of the small number of patients the results should be treated with caution.

In this context, we believe that care must be taken in the event of APOS, surgery should not be immediately considered a failure, but patients/families should be warned of a one-third risk of actual surgery ineffectiveness.

4.6. VPH: literature review and comparison with our series (Table 3)

Ours included, ten original cases series have already been reported elsewhere [

14,

19,

30,

38,

42,

43,

44,

45,

46] using the classical Delalande or modified VPH procedures.

Our series has predominantly acquired cases (55%) with a rate of seizure freedom of 86.3% compared to the series of Honda

et al with only congenital cases and a seizure freedom rate of 66.7%. [

30]

The mean age at surgery in our series (7.3 y) is very similar to the population of Delalande

et al (8.0 y) [

14]. The lowest mean age at surgery (4.3 y) is reported in the series of Honda

et al [

30] probably because all their patients were congenital cases. In their series, all patients received blood transfusions compared with 20% in ours. In our population, the need for transfusion was significantly related to patient age (p = 0.0034) and our low rate of transfusion (20%) can then be explained by the low number of cases of hemimegalencephaly or Sturge-Weber syndrome.

With 86.3% of patients in Engel I at one-year follow-up and only one in Engel IV (4%), our series confirms the vertical parasagittal sub-insular HST as a very efficient procedure to treat refractory hemispheric DRE.

5. Conclusions

The modified vertical parasagittal sub-insular hemispherotomy is a safe and successful surgical technique for hemispheric DRE with similar seizure freedom rate to the biggest series reported in the literature. Our modifications permitted a low rate of postoperative hydrocephalus and an excellent motor and cognitive long-term outcome. Longer follow-up and quantitative measurement of the pre and postoperative cognitive status are needed to assess the impact of the sub-insular approach.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, C.R.; methodology, C.R.; validation, C.R., N.D.G. and S.F.S.; formal analysis, N.D.G.; investigation, C.R. and N.D.G.; data curation, N.D.G; writing—original draft preparation, C.R and N.D.G.; writing—review and editing, N.D.G, C.R and S.F.S.; supervision, C.R.. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by Ethics Committee of Cliniques Universitaires Saint Luc (protocol code 2023/10AOU/347 approved the 31/08/23).

Informed Consent Statement

All patients’ caregivers signed an informed consent thus agreeing use of medical data for future clinical research.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available in the article.

Acknowledgments

We thank Elisa Dardenne, our data manager for her help with the statistical analysis of the reported data.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Rasmussen, T. Hemispherectomy for Seizures Revisited. Canadian Journal of Neurological Sciences / Journal Canadien des Sciences Neurologiques 1983, 10, 71–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Laine, E.; Pruvot, P.; Osson, D. Ultimate Results of Hemispherectomy in Cases on Infantile Cerebral Hemiatrophy Productive of Epilepsy. Neurochirurgie 1964, 10, 507–522. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Noetzel Mi, V.H. Diffusion Yon Blutfarbstoff in Der Inneren Rantlzone Unr Iiul~eren 0berfliiehe Des Zentralnervensystems Bei Subarachnoidaler Blutung.

- Delalande OP, J.M.; B. C.; G.M.; P.P.; D.O.A. Hemispherotomy: A New Procedure for Central Disconnection. Epilepsia 1992, 33, 99–100. [Google Scholar]

- Morino, M.; Shimizu, H.; Ohata, K.; Tanaka, K.; Hara, M. Anatomical Analysis of Different Hemispherotomy Procedures Based on Dissection of Cadaveric Brains. J Neurosurg 2002, 97, 423–431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- The Human Central Nervous System.

- Türe, U.; Yaşargil, D.C.H.; Al-Mefty, O.; Yaşargil, M.G. Topographic Anatomy of the Insular Region. J Neurosurg 1999, 90, 720–733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blanchet, B.; Roland, J.; Braun, M.; Anxionnat, R.; Moret, C.; Picard, L. [The Anatomy and the MRI Anatomy of the Interhemispheric Cerebral Commissures]. J Neuroradiol 1995, 22, 237–251. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Alotaibi, F.; Albaradie, R.; Almubarak, S.; Baeesa, S.; Steven, D.A.; Girvin, J.P. Hemispherotomy for Epilepsy: The Procedure Evolution and Outcome. Canadian Journal of Neurological Sciences / Journal Canadien des Sciences Neurologiques 2021, 48, 451–463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schramm, J.; Behrens, E.; Entzian, W. Hemispherical Deafferentation. Neurosurgery 1995, 36, 509–516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Villemure, J.-G.; Mascott, C.R. Peri-Insular Hemispherotomy. Neurosurgery 1995, 37, 975–980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shimizu, H.; Maehara, T. Modification of Peri-Insular Hemispherotomy and Surgical Results. Neurosurgery 2000, 47, 367–373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hmaimess, G.; Raftopoulos, C.; Kadhim, H.; Nassogne, M.-C.; Ghariani, S.; de Tourtchaninoff, M.; van Rijckevorsel, K. Impact of Early Hemispherotomy in a Case of Ohtahara Syndrome with Left Parieto-Occipital Megalencephaly. Seizure 2005, 14, 439–442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Delalande, O.; Bulteau, C.; Dellatolas, G.; Fohlen, M.; Jalin, C.; Buret, V.; Viguier, D.; Dorfmüller, G.; Jambaqué, I. VERTICAL PARASAGITTAL HEMISPHEROTOMY. Operative Neurosurgery 2007, 60, 19–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Delalande, O.; Dorfmüller, G. Hémisphérotomie Verticale Parasagittale : Technique Opératoire. Neurochirurgie 2008, 54, 353–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Engel, J.V.N.P.Jr. R.T.B. and O.L.M. Outcome with Respect to Epileptic Seizures., 2nd ed; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Baltus, C.; El M’Kaddem, B.; Ferrao Santos, S.; Ribeiro Vaz, J.G.; Raftopoulos, C. Second Surgery after Vertical Paramedian Hemispherotomy for Epilepsy Recurrence. Heliyon 2023, 9, e14326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bulteau, C.; Otsuki, T.; Delalande, O. Epilepsy Surgery for Hemispheric Syndromes in Infants: Hemimegalencepahly and Hemispheric Cortical Dysplasia. Brain Dev 2013, 35, 742–747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- de Palma, L.; Pietrafusa, N.; Gozzo, F.; Barba, C.; Carfi-Pavia, G.; Cossu, M.; De Benedictis, A.; Genitori, L.; Giordano, F.; Russo, G. Lo; et al. Outcome after Hemispherotomy in Patients with Intractable Epilepsy: Comparison of Techniques in the Italian Experience. Epilepsy & Behavior 2019, 93, 22–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lew, S.M.; Koop, J.I.; Mueller, W.M.; Matthews, A.E.; Mallonee, J.C. Fifty Consecutive Hemispherectomies. Neurosurgery 2014, 74, 182–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Massicotte, E.M.; Del Bigio, M.R. Human Arachnoid Villi Response to Subarachnoid Hemorrhage: Possible Relationship to Chronic Hydrocephalus. J Neurosurg 1999, 91, 80–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Durieux, P.F.; Schiffmann, S.N.; d’Exaerde, A. de K. Targeting Neuronal Populations of the Striatum. Front Neuroanat 2011, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, S.; Hikosaka, O. The Globus Pallidus Sends Reward-Related Signals to the Lateral Habenula. Neuron 2008, 60, 720–729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- van Schouwenburg, M.; Aarts, E.; Cools, R. Dopaminergic Modulation of Cognitive Control: Distinct Roles for the Prefrontal Cortex and the Basal Ganglia. Curr Pharm Des 2010, 16, 2026–2032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rahayel, S.; Postuma, R.B.; Montplaisir, J.; Génier Marchand, D.; Escudier, F.; Gaubert, M.; Bourgouin, P.-A.; Carrier, J.; Monchi, O.; Joubert, S.; et al. Cortical and Subcortical Gray Matter Bases of Cognitive Deficits in REM Sleep Behavior Disorder. Neurology 2018, 90, e1759–e1770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lai, S.; Zhong, S.; Liao, X.; Wang, Y.; Huang, J.; Zhang, S.; Sun, Y.; Zhao, H.; Jia, Y. Biochemical Abnormalities in Basal Ganglia and Executive Dysfunction in Acute- and Euthymic-Episode Patients with Bipolar Disorder: A Proton Magnetic Resonance Spectroscopy Study. J Affect Disord 2018, 225, 108–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delvecchio, G.; Pigoni, A.; Perlini, C.; Barillari, M.; Versace, A.; Ruggeri, M.; Altamura, A.C.; Bellani, M.; Brambilla, P. A Diffusion Weighted Imaging Study of Basal Ganglia in Schizophrenia. Int J Psychiatry Clin Pract 2018, 22, 6–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dorfer, C.; Czech, T.; Dressler, A.; Gröppel, G.; Mühlebner-Fahrngruber, A.; Novak, K.; Reinprecht, A.; Reiter-Fink, E.; Traub-Weidinger, T.; Feucht, M. Vertical Perithalamic Hemispherotomy: A Single-Center Experience in 40 Pediatric Patients with Epilepsy. Epilepsia 2013, 54, 1905–1912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fohlen, M.; Dorfmüller, G.; Ferrand-Sorbets, S.; Dorison, N.; Chipaux, M.; Taussig, D. Parasagittal Hemispherotomy in Hemispheric Polymicrogyria with Electrical Status Epilepticus during Slow Sleep: Indications, Results and Follow-Up. Seizure 2019, 71, 190–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Honda, R.; Kaido, T.; Sugai, K.; Takahashi, A.; Kaneko, Y.; Nakagwa, E.; Sasaki, M.; Otsuki, T. Long-Term Developmental Outcome after Early Hemispherotomy for Hemimegalencephaly in Infants with Epileptic Encephalopathy. Epilepsy & Behavior 2013, 29, 30–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaughan, D.N.; Jackson, G.D. The Piriform Cortex and Human Focal Epilepsy. Front Neurol 2014, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Falconer, M.A.; Serafetinides, E.A. A Follow-up Study of Surgery in Temporal Lobe Epilepsy. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 1963, 26, 154–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Garcia, P.A.; Barbaro, N.M.; Laxer, K.D. The Prognostic Value of Postoperative Seizures Following Epilepsy Surgery. Neurology 1991, 41, 1511–1511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malla, B.R.; O’Brien, T.J.; Cascino, G.D.; So, E.L.; Radhakrishnan, K.; Silbert, P.; Marsh, W.R. Acute Postoperative Seizures Following Anterior Temporal Lobectomy for Intractable Partial Epilepsy. J Neurosurg 1998, 89, 177–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mani, J.; Gupta, A.; Mascha, E.; Lachhwani, D.; Prakash, K.; Bingaman, W.; Wyllie, E. Postoperative Seizures after Extratemporal Resections and Hemispherectomy in Pediatric Epilepsy. Neurology 2006, 66, 1038–1043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wieser, H.G.; Blume, W.T.; Fish, D.; Goldensohn, E.; Hufnagel, A.; King, D.; Sperling, M.R.; Lüders, H.; Pedley, T.A.; Commission on Neurosurgery of the International League Against Epilepsy (ILAE) ILAE Commission Report. Proposal for a New Classification of Outcome with Respect to Epileptic Seizures Following Epilepsy Surgery. Epilepsia 2001, 42, 282–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giridharan, N.; Horn, P.S.; Greiner, H.M.; Holland, K.D.; Mangano, F.T.; Arya, R. Acute Postoperative Seizures as Predictors of Seizure Outcomes after Epilepsy Surgery. Epilepsy Res 2016, 127, 119–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panigrahi, M.; Krishnan, S.S.; Vooturi, S.; Vadapalli, R.; Somayajula, S.; Jayalakshmi, S. An Observational Study on Outcome of Hemispherotomy in Children with Refractory Epilepsy. International Journal of Surgery 2016, 36, 477–482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moosa, A.N. V.; Gupta, A.; Jehi, L.; Marashly, A.; Cosmo, G.; Lachhwani, D.; Wyllie, E.; Kotagal, P.; Bingaman, W. Longitudinal Seizure Outcome and Prognostic Predictors after Hemispherectomy in 170 Children. Neurology 2013, 80, 253–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, K.; Buchhalter, J.; McClelland, R.; Raffel, C. Frequency and Significance of Acute Postoperative Seizures Following Epilepsy Surgery in Children and Adolescents. Epilepsia 2002, 43, 874–881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koh, S.; Nguyen, S.; Asarnow, R.F.; LoPresti, C.; Yudovin, S.; Shields, W.D.; Vinters, H. V.; Mathern, G.W. Five or More Acute Postoperative Seizures Predict Hospital Course and Long-Term Seizure Control after Hemispherectomy. Epilepsia 2004, 45, 527–533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tripathi, M.; Chandra, P.; Padma, V.; Shailesh, G.; Chandreshekar, B.; Sarkar, C. Hemispherotomy for Intractable Epilepsy. Neurol India 2008, 56, 127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arifin, M.T.; Muttaqin, Z.; Hanaya, R.; Bakhtiar, Y.; Bintoro, A.C.; Iida, K.; Kurisu, K.; Arita, K.; Andar, E.B.P.S.; B, H.K.; et al. Hemispherotomy for Drug-Resistant Epilepsy in an Indonesian Population. Epilepsy Behav Rep 2019, 12, 100337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kawai, K.; Morino, M.; Iwasaki, M. Modification of Vertical Hemispherotomy for Refractory Epilepsy. Brain Dev 2014, 36, 124–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iwasaki, M.; Uematsu, M.; Osawa, S.; Shimoda, Y.; Jin, K.; Nakasato, N.; Tominaga, T. Interhemispheric Vertical Hemispherotomy: A Single Center Experience. Pediatr Neurosurg 2015, 50, 295–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarat Chandra, P.; Subianto, H.; Bajaj, J.; Girishan, S.; Doddamani, R.; Ramanujam, B.; Chouhan, M.S.; Garg, A.; Tripathi, M.; Bal, C.S.; et al. Endoscope-Assisted (with Robotic Guidance and Using a Hybrid Technique) Interhemispheric Transcallosal Hemispherotomy: A Comparative Study with Open Hemispherotomy to Evaluate Efficacy, Complications, and Outcome. J Neurosurg Pediatr 2019, 23, 187–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).