Submitted:

05 September 2023

Posted:

08 September 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study design

2.2. Data presentation and Statistical Analysis

2.3. Ethics approval

3. Results and Commentaries

3.1. Cellular immune profile in AIDS (1983–1985)

| GROUPS | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CONTROL (n=11) |

RISK (n=27) |

LAS/ARC (n=37) |

AIDS (n=47) |

|

| Age (years) | 30.4 | 30.7 | 31.9 | 30.8 |

| Leucocytes/mm3 | 5263.6 | 5955.6 | 5689.2 | 4763.8* |

| Lymphocytes/mm3 | 1967.6 | 2316.7 | 2264.2 | 1218.2* |

| T lymphocyte (%) | 64.0 | 64.8 | 62.2 | 52.1* |

| T lymphocytes/mm3 | 1247 | 1509.8 | 1403.9 | 662.3* |

| B lymphocytes (%) | 18.2 | 16.6 | 15.0 | 18.6 |

| B lymphocytes/mm3 | 397.3 | 362.7 | 307.6 | 214.4* |

| T4 (%) | 44.4 | 37.8 | 26.3 | 13.5* |

| T4/mm3 | 863 | 833.9 | 591.4 | 191.2* |

| T8 (%) | 21.6 | 26.6 | 37.3* | 39.0* |

| T8/mm3 | 451.9 | 620.2 | 797.6* | 550.7 |

| T4/T8 | 2.3 | 1.6 | 0.74* | 0.53* |

| PHA 20 µg/mL | 255979.7 | 233381.8 | 175852.9 | 118450.1* |

| Con-A 20 µg/mL | 172269.5 | 136493.3 | 111128.2 | 54795.5* |

| PWM 20 µg/mL | 75942.8 | 71469.8 | 27760.5 | 17930.1* |

| PPD 10 µg/mL | 59989.1 | 16696.0 | 15505.3* | 7098.8* |

3.2. HIV diagnosis in children (1989–1993)

3.3. HIV/HTLV co-infections in patients attended by one Hospital of São Paulo (1991–1994)

| Year of collection | Local/ Group |

Number of cases | Mean age (years) |

Sex (number) | HTLV-1/-2 (%) |

HTLV-1 (%) | HTLV-2 (%) | Ref |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1991–1992 | IIER, SP | 471 | M (406) F (65) | 62 (13.2) | 37 (7.9) | 25 (5.3) | [30] | |

| IDU | 216 | 29 | M (155) F (61) | 57 (26.4) | 33 (15.3) | 24 (11.1) | ||

| Homo/Bis | 229 | 34 | M (229) | 3 (1.3) | 2 (0.9) | 1 (0.4) | ||

| Othersa | 26 | 30 | M (22) F (4) | 2 (7.7) | 2 (7.7) | |||

| 1994 | IIER, SP | 553 | 32 | M (358) F (195) | 56 (10.1) | 22 (4.0) | 34 (6.1) | [31] |

| IDU | 89 | 29 | M (65) F (24) | 25 (28.0) | 10 (11.2) | 15 (16.8) | ||

| Hetero | 236 | 33 | M (96) F (140) | 21 (8.9) | 8 (3.4) | 13 (5.5) | ||

| Homo/Bis | 139 | 33 | M (139) | 5 (3.6) | 2 (1.4) | 3 (2.2) | ||

| Others/Unkb | 89 | 32 | M (58) F (31) | 5 (5.6) | 2 (2.2) | 3 (3.4) | ||

| 2001–2002 | CRTA-PR | 758 | 36 | M (424) F (334) | 43 (5.7) | 6 (0.8) | 37 (4.9) | [32,33] |

| Sexual | 633 | 16 (2.5) | 2 (0.3) | 14 (2.2) | ||||

| IDU | 57 | 17 (29.8) | 2 (3.5) | 15 (26.3) | ||||

| Sexual+IDU | 33 | 7 (21.2) | 1 (3.0) | 6 (18.2) | ||||

| Otherc | 35 | 3 (8.6) | 1 (2.9) | 2 (5.7) | ||||

| 1999–2006 | CRTAs, SP | 1,393 | M (982) F (411) | 81 (5.8) | 46 (3.3) | 35 (2.5) | [35] | |

| Clinics, SP | 919 | M (538) F (381) | 121 (13.2) | 88 (9.6) | 33 (3.6) | |||

| 2014–2015 | CRTA-SP | 1,608 | 44 | M (1237) F (371) | 50 (3.1) | 26 (1.6) | 22 (1.4) | [36] |

| 2012–2015 | CRTAs, SP | 1,383 | 36 | M (930) F (453) | 58 (4.2) | 29 (2.1) | 24 (1.7) | [43,45] |

3.4. HIV/HTLV co-infections in Londrina, Paraná (2001–2002)

3.5. HIV/HTLV co-infections in patients of several CRTAs and out-patient clinics of São Paulo (1999–2006)

3.6. HIV/HTLV co-infections in patients of the pioneer CRTA-SP (2014–2015)

3.7. HIV and HIV/HTLV co-infection in patients of several CRTAs of São Paulo (2010–2016)

3.8. HIV/HTLV co-infections in recent CRTAs setting in São Paulo (2012–2015)

3.9. Variations of HIV/HTLV co-infections prevalence rates regarding the years of sample collection (1991–2015)

| Years of samples collection | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1991–1992a (n=471) |

1994b (n=553) |

2001–2002c (n=758) |

1999–2006d (n=1,393) |

2014–2015e (n=1,608) |

2012–2015f (n=1,383) |

p-value | |

| n (%) | n (%) | n (%) | n (%) | n (%) | n (%) | ||

| HIV/HTLV | 62 (13.2) | 56 (10.1) | 43 (5.7) | 81 (5.8) | 50 (3.1) | 58 (4.2) | <0.0000001 |

| HIV/HTLV-1 | 37 (7.9) | 22 (4.0) | 6 (0.8) | 46 (3.3) | 26 (1.6) | 29 (2.1) | <0.0000001 |

| HIV/HTLV-2 | 25 (5.3) | 34 (6.1) | 37 (4.9) | 35 (2.5) | 22 (1.4) | 24 (1.1) | <0.0000001 |

4. Discussion

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflict of Interest

References

- Laurindo-Teodorescu, L.; Teixeira, P.R. Histórias da aids no Brasil: As respostas governamentais à epidemia de aids. Ministério da Saúde/Secretaria de Vigilância em Saúde/Departamento de DST, Aids e Hepatites Virais, Brasília, Brazil, 2015; Vol. 1, pp. 1–464. Available online: https://unesdoc.unesco.org/ark:/48223/pf0000235557?posInSet=2&queryId=f390b88f-74e1-450d-a274-cfb553262cc7 (accessed on 4 July 2023).

- CDC. Pneumocystis Pneumonia: Los Angeles. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report (MMWR). Centers for Disease Control, June 5, 1981; Volume 30(21), pp. 250–252. Available online: https://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/preview/mmwrhtml/june_5.htm (accessed on 4 July 2023).

- CDC. Kaposi's Sarcoma and Pneumocystis Pneumonia Among Homosexual Men — New York City and California. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report (MMWR). Centers for Disease Control, July 3, 1981; Volume 30(25), pp. 305–308. Available online: https://www.jstor.org/stable/23300179 (accessed on 4 July 2023).

- CDC. Opportunistic Infections and Kaposi's Sarcoma among Haitians in the United States. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report (MMWR). Centers for Disease Control, July 9, 1982; Volume 31(26), pp. 353–354,360–361. Available online: https://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/preview/mmwrhtml/00001123.htm (accessed on 4 July 2023).

- CDC. Pneumocystis carinii pneumonia among persons with hemophilia A. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report (MMWR). Centers for Disease Control, July 16, 1982; Volume 31(27), pp. 365–367. Available online: https://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/preview/mmwrhtml/00001126.htm (accessed on 4 July 2023).

- CDC. Current Trends Update on Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndrome (AIDS) -United States. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report (MMWR). Centers for Disease Control, September 24, 1982; Volume 31(37), 507–508,513–514. Available online: https://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/preview/mmwrhtml/00001163.htm (accessed on 4 July 2023).

- Poiesz, B.J.; Ruscetti, F.W.; Gazdar, A.F.; Bunn, P.A.; Minna, J.D.; Gallo, R.C. Detection and isolation of type C retrovirus particles from fresh and cultured lymphocytes of a patient with cutaneous T-cell lymphoma. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1980; 77(12), 7415–7419. [CrossRef]

- Kalyanaraman, V.S.; Sarngadharan, M.G.; Robert-Guroff, M.; Miyoshi, I.; Golde, D.; Gallo, R.C. A new subtype of human T-cell leukemia virus (HTLV-II) associated with a T-cell variant of hairy cell leukemia. Science. 1982; 218, 571–573. [CrossRef]

- Barré-Sinoussi, F.; Chermann, J.C.; Rey, F.; Nugeyre M.T.; Chamaret, S.; Gruest, J.; Dauguet, C.; Axler-Blin,C.; Vézinet-Brun, F.; Rouzioux, C.; Rozenbaum, W.; Montagnier, L. Isolation of a T-lymphotropic retrovirus from a patient at risk for acquired immune deficiency syndrome (AIDS). Science. 1983 May 20; 220(4599), 868–871. [CrossRef]

- Popovic, M.; Sarngadharan, M.G.; Read, E.; Gallo, R.C. Detection, isolation, and continuous production of cytopathic retroviruses (HTLV-III) from patients with AIDS and pre-AIDS. Science. 1984 May 4; 224(4648), 497–500. [CrossRef]

- Gallo, R.C.; Salahuddin, S.Z.; Popovic, M.; Shearer, G.M.; Kaplan, M.; Haynes, B.F.; Palker. T.J.; Redfield, R.; Oleske, J.; Safai, B.; et al. Frequent detection and isolation of cytopathic retroviruses (HTLV-III) from patients with AIDS and at risk for AIDS. Science. 1984 May 4; 224(4648), 500–503. [CrossRef]

- Vallinoto, A.C.R.; Rosadas, C.; Machado, L.F.A.; Taylor, G.P.; Ishak, R. HTLV: It is time to reach a consensus on its nomenclature. Front Microbiol. 2022; 13, 896224. [CrossRef]

- Brites, C.; Sampaio, J.; Oliveira, A. HIV/Human T-cell lymphotropic virus coinfection revisited: Impact on AIDS progression. AIDS Rev. 2009; 11, 8–16 Available online: https://www.aidsreviews.com/resumen.php?id=1030&indice=2009111&u=unp.

- Beilke, M.A. Retroviral coinfections: HIV and HTLV: Taking stock of more than a quarter century of research. AIDS Res Hum Retroviruses. 2012; 28(2), 139–147. [CrossRef]

- Montaño-Castellón, I.; Marconi, C.S.C.; Saffe, C.; Brites, C. Clinical and laboratory outcomes in HIV-1 and HTLV-1/2 coinfection: A systematic review. Front Public Health. 2022; 10, 820727. [CrossRef]

- Rosadas, C.; Taylor, G.P. HTLV-1 and co-infections. Front Med. 2022; 9, 812016. [CrossRef]

- Gessain, A.; Cassar, O. Epidemiological aspects and world distribution of HTLV-1 infection. Front Microbiol. 2012; 3, 388. [CrossRef]

- Murphy, E.L.; Cassar, O.; Gessain, A. Estimating the number of HTLV-2 infected persons in the world. Retrovirology 2015, 12(Suppl 1):O5 Available online: http://www.retrovirology.com/content/12/S1/O5 (accessed on 22 August, 2023). [CrossRef]

- Carneiro-Proietti, A.B.F.; Catalan-Soares, B.C.; Castro-Costa, C.M.; Murphy, E.L.; Sabino, E.C.; Hisada, M.; Galvão-Castro, B.; Alcantara, L.C.J.; Remondegui, C.; Verdonck, K.; Proietti, F.A. HTLV in the Americas: Challenges and perspectives. Rev Panam Salud Publica. 2006; 19(1),44–53. [CrossRef]

- Briggs, N.C.; Battjes, R.J.; Cantor, K.P.; Blattner, W.A.; Yellin, F.M.; Wilson, S.; Ritz, A. L.; Weiss, S.H.; Goedert, J.J. Seroprevalence of human T cell lymphotropic virus type II infection, with or without human immunodeficiency virus type 1 coinfection, among US intravenous drug users. J Infect Dis. 1995; 172(1), 51-58. [CrossRef]

- Paiva, A.; Casseb, J. Origin and prevalence of human T-lymphotropic virus type 1 (HTLV-1) and type 2 (HTLV-2) among indigenous populations in the Americas. Rev Inst Med Trop Sao Paulo. 2015; 57(1), 1–13. [CrossRef]

- Ishak, R.; Ishak, M.O.G.; Azevedo V.N.; Machado, L.F.A.; Vallinoto, I.M.C.; Queiroz, M.A.F.; Costa, G.L.C.; Guerreiro, J.F.; Vallinoto, A.C.R. HTLV in South America: Origins of a silent ancient human infection. Virus Evol. 2020; 6(2), veaa053. [CrossRef]

- De-Araujo, A.C. Cell-mediated immunity in the Acquired Immunodeficiency Syndrome. Brazilian J Med Biol Res. 1987; 20, 579–582. PMID: 3452448. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/profile/Adele-Caterino-De-Araujo/publications (accessed on 6 July 2023).

- Amadori, A.; Zamarchi, R.; Ciminale, V.; Del Mistro, A.; Siervo, A.; Alberti, A.; Colombatti, M.; Chieco-Bianchi, L. HIV-1-specific B cell activation. A major constituent of spontaneous B cell activation during HIV-1 infection. J Immunol. 1989; 143(7), 2146–2152. [CrossRef]

- Amadori, A.; De Rossi, A.; Faulkner-Valle, GP.; Chieco-Bianchi, L. Spontaneous in vitro production of virus-specific antibody by lymphocytes from HIV-infected subjects. Clin Immunol Immunopathol. 1988; 46(3), 342–351. [CrossRef]

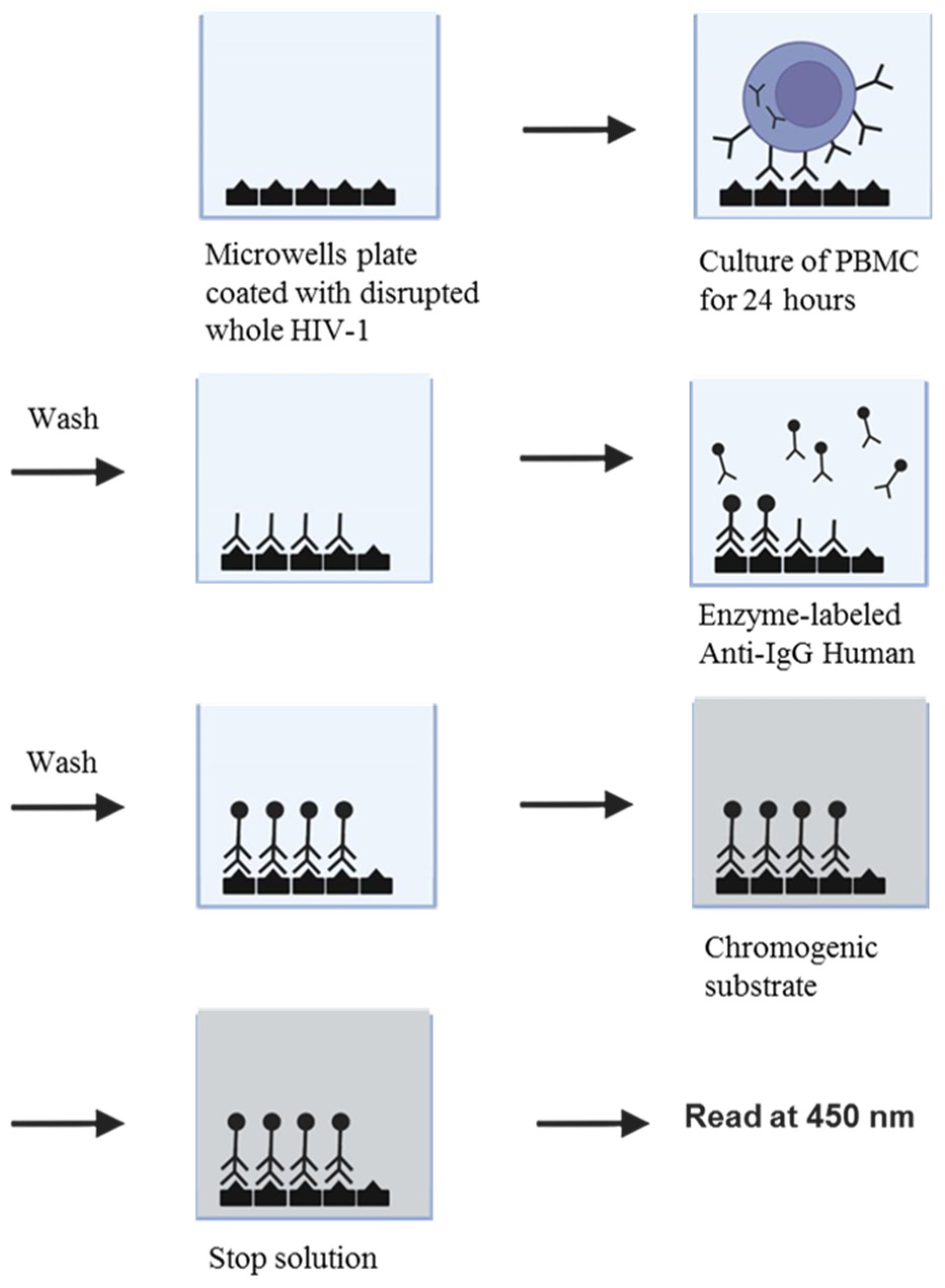

- Caterino-de-Araujo, A.; de-los- Santos-Fortuna, E.; Grumach, A.S. An alternative method for in vitro production of HIV-1-specific antibodies. Brazilian J Med Biol Res. 1991; 24, 797–799. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/profile/Adele-Caterino-De-Araujo/publications (accessed on 6 July 2023).

- Caterino-de-Araujo, A. Rapid in vitro detection of HIV-1-specific antibody secretion by cells-culture with virus antigens. Mem Inst Oswaldo Cruz. Rio de Janeiro. 1992; 87(2), 239–247. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/profile/Adele-Caterino-De-Araujo/publications (accessed on 6 July 2023). [CrossRef]

- De Rossi, A.; Mammano, F.; Del Mistro, A.; Chieco-Bianchi, L. Serological and molecular evidence of infection by human T-cell lymphotropic virus type II in Italian drug addicts by use of synthetic peptides and polymerase chain reaction. Eur J Cancer Clin Oncol. 1991; 27(7), 835-838. [CrossRef]

- Koech, C.C.; Lwembe, R.M.; Odari, E.O.; Budambula, N.L.M. Prevalence and associated risk factors of HTLV/HIV co-infection among people who inject drugs (PWIDs): A review. J Hum Virol Retrovirol 6(1): 00188. [CrossRef]

- Caterino de Araujo, A.; do Rosario Casseb, J.S.; Neitzert, E.; Xavier de Souza, M.L.; Mammano, F.; Del Mistro, A.; De Rossi, A.; Chieco-Bianchi, L. HTLV-I and HTLV-II infections among HIV-1 seropositive patients in Sao Paulo, Brazil. Eur J Epidemiol. 1994; 10, 165–171. [CrossRef]

- Caterino-de-Araujo, A.; de los Santos-Fortuna, E.; Meleiro, M.C.Z.; Suleiman, J.; Calabrò, M.L.; Favero, A.; De Rossi, A.; Chieco-Bianchi, L. Sensitivity of two enzyme-linked Immunosorbent assay tests in relation to Western blot in detecting human T-cell lymphotropic virus types I and II infection among HIV-1 infected patients from São Paulo, Brazil. Diagn Microbiol Infect Dis. 1998; 30(3), 173–182. [CrossRef]

- Morimoto, H.K.; Caterino-De-Araujo, A.; Morimoto, A.A.; Reiche, E.M.V.; Ueda, L.T.; Matsuo, T.; Stegmann, J.W.; , Reiche, F.V. Seroprevalence and risk factors for Human T cell lymphotropic virus type 1 and 2 infection in human immunodeficiency virus-infected patients attending AIDS referral center health units in Londrina and other communities in Paraná, Brazil. AIDS Res Hum Retroviruses. 2005. 21(4), 256–262. [CrossRef]

- Morimoto, H.K.; Morimoto, A.A.; Reiche, E.M.V.; Ueda, L.T.; Matsuo, T.; Reiche, F.V.; Caterino-de-Araujo, A. Difficulties in the diagnosis of HTLV-2 infection in HIV/AIDS patients from Brazil: Comparative performances of serologic and molecular assays, and detection of HTLV-2b subtype. Rev Inst Med Trop. Sao Paulo. 2007; 49(4), 225–230. [CrossRef]

- Casseb, J.; Souza, T.; Pierre-Lima, M.T.; Yeh, E.; Hendry, M.; Gallo, D. Testing problems in diagnosing HTLV infection among intravenous drug users with AIDS in São Paulo city, Brazil. AIDS Res Hum Retroviruses. 1997; 13(18), 1639-1641. [CrossRef]

- Jacob, F.; Santos-Fortuna, E.; Azevedo, R.S.; Caterino-de-Araujo, A. Serological patterns for HTLV-I/II and its temporal trend in high-risk populations attended at Public Health Units of São Paulo, Brazil. J. Clin. Virol. 2008; 42(2), 149–155. [CrossRef]

- Caterino-de-Araujo, A.; Sacchi, C.T.; Gonçalves, M.G.; Campos, K.R.; Magri, M.C.; Alencar, W.K.; Group of Surveillance and Diagnosis of HTLV of São Paulo (GSuDiHTLV-SP). Current prevalence and risk factors associated with HTLV-1 and HTLV-2 infections among HIV/AIDS patients in São Paulo, Brazil. AIDS Res. Hum. Retroviruses. 2015; 31(5), 543–549. [CrossRef]

- Zunt, J.R.; Tapia, K.; Thiede, H.; Lee, R.; Hagan, H. HTLV-2 infection in injection drug users in King County, Washington. Scand J Infect Dis. 2006; 38(8), 654–663. [CrossRef]

- Mesquita, F.; Kral, A.; Reingold, A.; Bueno, R.; Trigueiros, D.; Araujo, P.J.; Santos Metropolitan Region Collaborative Study Group. Trends of HIV infection among injection drug users in Brazil in the 1990s: The impact of changes in patterns of drug use. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2001; 28(3), 298–302. [CrossRef]

- Mesquita, F.; Doneda, D.; Gandolfi, D.; Nemes M.I.B.; Andrade, T.; Bueno, R.; Trigueiros, D,P. Brazilian response to the human immunodeficiency virus/acquired immunodeficiency syndrome epidemic among injection drug users. Clin Infect Dis. 2003; 37(Suppl 5), S382–S385. [CrossRef]

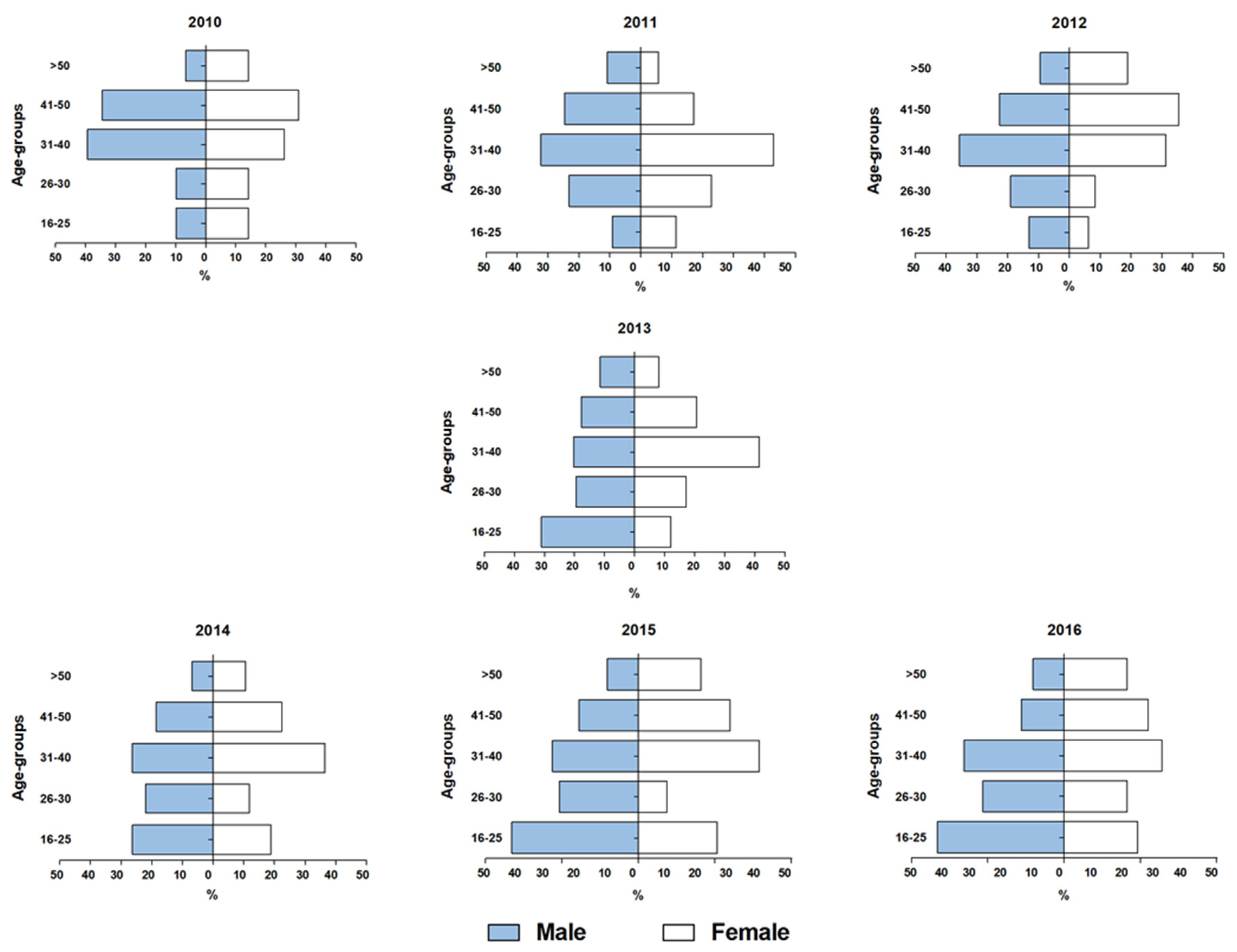

- Caterino-de-Araujo, A.; Campos, K.R. Spread of human retrovirus infections in individuals at the second and third decades of life in São Paulo, Brazil. Austin J HIV/AIDS Res. 2017; 4(1), 1036. Available online: https://austinpublishinggroup.com/hiv-aids-research/fulltext/ajhr-v4-id1036.pdf (accessed on 11 July 2023).

- Paiva, A.; Casseb, J. Sexual transmission of human T-cell lymphotropic virus type 1. Rev Soc Bras Med Trop. 2014; 47(3), 265-274. [CrossRef]

- HIV–AIDS, Boletim Epidemiológico, Brasília, 2016. Ano V, Nº 1 da 27ª a 53ª semanas epidemiológicas - julho a dezembro de 2015 e da 01ª a 26ª semanas epidemiológicas - janeiro a junho de 2016. Available online: http://antigo.aids.gov.br/pt-br/pub/2016/boletim-epidemiologico-de-aids-2016 (accessed on 12 July 2023).

- Campos, K.R.; Gonçalves, M.G.; Caterino-de-Araujo, A. Failures in detecting HTLV-1 and HTLV-2 in patients infected with HIV-1. AIDS Res Hum Retroviruses. 2017; 33(4), 382–385. [CrossRef]

- Kuramitsu, M.; Sekizuka, T.; Yamochi, T.; Firouzi, S.; Sato, T.; Umeki, K.; Sasaki, D.; Hasegawa, H.; Kubota, R.; Sobata, R.; Matsumoto, C.; Kaneko, N.; Momose, H.; Araki, K.; Saito, M.; Nosaka, K.; Utsunomiya, A.; Koh, K-R.; Ogata, M.; Uchimaru, K.; Iwanaga, M.; Sagara, Y.; Yamano, Y.; Okayama, A.; Miura, K.; Satake, M.; Saito, S.; Itabashi, K.; Yamaguchi, K.; Kuroda, M.; Watanabe, T.; Okuma, K.; Hamaguchi, I. 2017. Proviral features of human T cell leukemia virus type 1 in carriers with indeterminate Western blot analysis results. J Clin Microbiol. 2017; 55(9), 2838–2849. [CrossRef]

- Campos, K.R.; Gonçalves, M.G.; Costa, N.A.; Caterino-de-Araujo, A. Comparative performances of serologic and molecular assays for detecting HTLV-1 and HTLV-2 in patients infected with HIV-1. Brazilian J Infect Dis. 2017; 21(3), 297–305. [CrossRef]

- Okuma, K.; Kuramitsu, M.; Niwa, T.; Taniguchi, T.; Masaki, Y.; Ueda G.; Matsumoto, C.; Sobata, R.; Sagara, Y.; Nakamura, H.; Satake, M.; Miura, K.; Fuchi, N.; Masuzaki, H.; Okayama, A.; Umeki, K.; Yamano, Y.; Sato, T.; Iwanaga, M.; Uchimaru, K.; Nakashima, M.; Utsunomiya, A.; Kubota, R.; Ishitsuka, K.; Hasegawa, H.; Sasaki, D.; Koh, K-R.; Taki, M.; Nosaka, K.; Ogata, M.; Naruse, I.; Kaneko, N.; Okajima, S.; Tezuka, K.; Ikebe, E.; Matsuoka, S.; Itabashi, K.; Saito, S.; Watanabe, T.; Hamaguchi, I. Establishment of a novel diagnostic test algorithm for human T-cell leukemia virus type 1 infection with line immunoassay replacement of western blotting: A collaborative study for performance evaluation of diagnostic assays in Japan. Retrovirology. 2020; 17(1), 26. [CrossRef]

- Brasil. Ministério da Saúde. Guia de Manejo Clínico da Infecção pelo HTLV / Ministério da Saúde, Secretaria de Vigilância em Saúde, Departamento de Doenças de Condições Crônicas e Infecções Sexualmente Transmissíveis. Brasília: Ministério da Saúde, 2021. 104p. : Il. ISBN 978-65-5993-116-3. Available online: http://antigo.aids.gov.br/pt-br/pub/2022/guia-de-manejo-clinico-da-infeccao-pelo-htlv (accessed on 14 July 2023).

- Vallinoto, A.C.R.; Azevedo, V.N.; Santos, D.E.M.; Caniceiro, S.; Mesquita, F.C.L.; Hall, W.W.; Ishak, M.O.G.; Ishak, R. Serological evidence of HTLV-I and HTLV-II coinfections in HIV-1 positive patients in Belém, state of Pará, Brazil. Mem Inst Oswaldo Cruz, Rio de Janeiro. 1998; 93(3), 407-409. [CrossRef]

- Laurentino, R.V.; Lopes, I.G.L.; Azevedo, V.N.; Machado, L.F.A.; Moreira, M.R.C.; Lobato, L.; Ishak, M.O.G.; Ishak, R.; Vallinoto, A.C.R. Molecular characterization of human T-cell lymphotropic virus coinfecting human immunodeficiency virus 1 infected patients in the Amazon region of Brazil. Mem Inst Oswaldo Cruz. 2005; 100(4), 371-376. [CrossRef]

- Alencar, S.P.; Souza, M.C.; Fonseca, R.R.S.; Menezes, C.R.; Azevedo, V.N.; Ribeiro, A.L.R.; Lima, S.S.; Laurentino, R.V.; Barbosa, M.A.A.P.; Freitas, F.B.; Oliveira-Filho, A.B.; Machado, L.F.A. Prevalence and molecular epidemiology of human T-lymphotropic virus (HTLV) infection in people living with HIV/AIDS in the Pará state, Amazon region of Brazil. Front Microbiol. 2020; 11, 572381. [CrossRef]

- Brites, C.; Goyanna, F.; França, L.G.; Pedroso C.; Netto, E.M.; Adriano, S.; Sampaio, J.; Harrington Jr, W. Coinfection by HTLV-I/II is associated with an increased risk of strongyloidiasis and delay in starting antiretroviral therapy for AIDS patients. Braz J Infect Dis. 2011; 15(1), 6-11. [CrossRef]

- Pereira, F.M.; Santos, F.L.N.; Silva, Â.A.O.; Nascimento, N.M.; Almeida, M.C.C.; Carreiro, R.P.; Galvão-Castro, B.; Grassi, M.F.R. Distribution of human immunodeficiency virus and human T-leukemia virus co-infection in Bahia, Brazil. Front Med. 2022; 8, 788176. [CrossRef]

- de Oliveira, E.H.; Oliveira-Filho, A.B.; Souza, L.A.; da Silva, L.V.; Ishak, M.O.G.; Ishak, R.; Vallinoto, A.C.R. Human T-cell lymphotropic virus in patients infected with HIV-1: Molecular epidemiology and risk factors for transmission in Piaui, Northeastern Brazil. Curr HIV Res. 2012; 10(8), 700-707. [CrossRef]

- Santos de Souza, M.; Prado Gonçales, J.; Santos de Morais, V.M.; Silva Júnior, J.V.J.; Lopes, T.R.R.; Costa, J.E.F.D.; Côelho, M.R.C.D. Prevalence and risk factor analysis for HIV/HTLV 1/2 coinfection in Paraíba state, Brazil. J Infect Dev Ctries. 2021; 15(10), 1551-1554. [CrossRef]

- Etzel, A.; Shibata, G.; Rozman, M.; Jorge, M.L.S.G.; Damas, C.D.; Segurado, A.A.C. HTLV-1 and HTLV-2 infections in HIV-infected individuals from Santos, Brazil: Seroprevalence and risk factors. JAIDS. 2001; 26(2), 185-190. Available online: https://journals.lww.com/jaids/abstract/2001/02010/htlv_1_and_htlv_2_infections_in_hiv_infected.13.aspx (accessed on 24 August 2023).

- Kleine-Neto, W.; SanabaniI, S.S.; Jamal, L.F.; Sabino, E.C. Prevalence, risk factors and genetic characterization of human T-cell lymphotropic virus types 1 and 2 in patients infected with human immunodeficiency virus type 1 in the cities of Ribeirão Preto and São Paulo. Rev Soc Bras Med Trop. 2009; 42 (3), 264-270. [CrossRef]

- Barcellos, N.T.; Fuchs, S.C.; Mondini, L.G.; Murphy, E.L. Human T lymphotropic virus type I/II infection: Prevalence and risk factors in individuals testing for HIV in counseling centers from Southern Brazil. Sex Transm Dis. 2006; 33(5), 302–306. [CrossRef]

- Galetto, L.R.; Lunge,V.R.; Béria, J.U.; Tietzmann, D.C.; Stein A.T.; Simon, D. Prevalence and risk factors for human T cell lymphotropic virus infection in Southern Brazilian HIV-positive patients. AIDS Res Hum Retroviruses. 2014; 30(9), 907-911. [CrossRef]

- Chequer, P.; Marins, J.R.P.; Possas, C.; Valero, J.D.A.; Bastos, F.I.; Castilho, E.; Hearst, N. AIDS research in Brazil. AIDS. 2005; 19 (suppl 4), S1–S3. [CrossRef]

- Okie, S. Fighting HIV – lessons from Brazil. N Engl J Med. 2006; 354: 1977–1981. [CrossRef]

- Boletim Epidemiológico. HIV – AIDS 2022. Secretaria de Vigilância em Saúde, Ministério da Saúde, Número Especial. Dez. 2022. Brasília. Available online: https://www.gov.br/aids/pt-br/centrais-de-conteudo/boletins-epidemiologicos/2022/hiv-aids/boletim_hiv_aids_-2022_internet_31-01-23.pdf/view (accessed on 17 July 2023).

- Colón-López, V.; Miranda-De León, S.; Machin-Rivera, M.; Soto-Abreu, R.; Marrero-Cajigas, E.L.; Rolón-Colón, Y.; Valencia-Torres, I.M.; Suárez-Pérez, E.L. New diagnoses among HIV+ men and women in Puerto Rico: Data from the HIV surveillance system 2003-2014. P R Health Sci J. 2019; 38(1), 33-39. PMID: 30924913. Available online: https://prhsj.rcm.upr.edu/index.php/prhsj/article/viewFile/1772/1171 (accessed on 22 August 2023).

- Agwu, A. Sexuality, sexual health, and sexually transmitted infections in adolescents and young adults. Top Antivir Med. 2020; 28(2), 459-462. Available online: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC7482983/ (accessed on 22 August 2023).

- The path that ends AIDS: UNAIDS Global AIDS Update 2023. Geneva: Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS; 2023. Licence: CC BY-NC-SA 3.0 IGO. Available online: https://thepath.unaids.org/wp-content/themes/unaids2023/assets/files/2023_report.pdf (accessed on 22 August 2023).

- Martin, F.; Tagaya, Y.; Gallo, R. Time to eradicate HTLV-1: An open letter to WHO. Lancet. 2018; 391(10133), 1893-1894. [CrossRef]

- WHO. Human T-lymphotropic virus type 1: Technical report. 2021 Available online: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789240020221 (accessed on 24 August 2023).

- Rosadas, C.; Menezes, M.L.B.; Galvão-Castro, B.; Assone, T.; Miranda, A.E.; Aragon, M.; Caterino-de-Araujo, A.; Taylor, G.P.; Ishak, R. Blocking HTLV-1/2 silent transmission in Brazil: Current public health policies and proposal of additional strategies. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2021; 15(9), e0009717. [CrossRef]

- Miranda, A.E.; Rosadas, C.; Assone, T.; Pereira, G.F.M.; Vallinoto, A.C.R.; Ishak, R. Strengths, Weaknesses, Opportunities and Threats (SWOT) analysis of the implementation of public health policies on HTLV-1 in Brazil. Front Med. 2022; 9:859115. [CrossRef]

- Sagara, Y.; Nakamura, H.; Satake, M.; Watanabe, T.; Hamaguchi, I. Increasing horizontal transmission of human T-cell leukemia virus type 1 in adolescents and young adults in Japan. J Clin Virol. 2022; 157, 105324. [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).