1. Introduction

One of the most essential state tasks in all countries is to solve the challenges of environmental protection as well as the integrated rational use of natural resources. Every year, it is particularly important to solve the tasks of limiting anthropogenic influences on terrestrial ecosystems, as well as to develop scientific measures and strategies for managing them to prevent undesirable changes and assure environmental safety. Special attention is paid to "industrial symbiosis", which is based on using waste from one industry as a raw material for another [1-4].

Economic importance. The melon fly is a major pest of cucurbit crops, causing significant economic losses to farmers. A control strategy that can effectively manage this pest could help reduce these losses and increase the profitability of these crops.

Environmental impact. The use of chemical pesticides to control melon fly populations can have negative environmental impacts, such as pollution of soil and water resources. An effective control strategy that relies on non-chemical methods like disinfection and soil productivity management could help reduce these impacts.

Food security. Cucurbit crops are an important source of food for many people, particularly in the regions where they are grown. Effective control of the melon fly could help ensure a stable supply of these crops, contributing to food security.

Innovation. Developing effective non-chemical pest control strategies requires innovation and scientific research. The topic of an effective melon fly control strategy based on disinfection and soil productivity management represents an important area of ongoing research and innovation in the field of pest management.

Overall, the topic of an effective melon fly control strategy based on disinfection and soil productivity management is relevant because it addresses important issues related to economic, environmental, and food security concerns, while also requiring innovation and scientific research to develop effective solutions.

Interest in the integrated use of natural resources and various wastes to produce new commercial goods has grown in both near and far countries such as the United States, England, Japan, China, Brazil, Europe, Russia, and Kazakhstan [5-8]. Numerous researches are being done in this direction to develop fertilisers, ameliorants, insecticides, and other agricultural agents [

9].

Mineral fertilizers used in agriculture harm the soil, ecosystem, and agricultural products. Uncontrolled and unscientific use of chemical fertilizers leads to the deterioration of soil ecosystems and the increase of soil acidification and heavy metal ions [

10]. Chemical fertilizer also negatively impacts crop quality and causes ecological environment damage, such as water pollution, greenhouse gas emissions, and N leaching [

11]. However, many modern methods used in environmental protection are not economically efficient and adversely affect the change of the soil layer. In order to improve the condition of the soil and increase the quality of food (improve the nutritional value), it is necessary to move to low-cost, environmentally friendly methods. Many green technologies such as biofertilizers, green manure, bacterialization, algal biofertilizers, and vermicompost contribute to the sustainable development of agriculture. Agricultural waste is a potential feedstock for composting, which is one of the important waste utilization methods.

Thus, improper fertilizing technology might have a negative effect on soil health and soil-related ecosystem services. Imbalanced use of chemical fertilizers can alter soil pH, and increase pest attack, acidification, and soil crust, which results in a decrease in soil organic carbon and useful organisms, stunting plant growth and yield, and even leading to the emission of greenhouse gases [

12].

Organic fertilizer can improve the physical and chemical properties of soil, such as structure, water retention, nutrients, and cation exchange capacity, and promotes positive biological soil properties, enhancing yield. Vermicompost provides plant growth hormones such as gibberellins, auxins, and cytokinins [

13].

Fruit flies constitute an important group of pests investing cucurbitaceous vegetables. In Kazakhstan, Cucurbitaceae are the leading crops grown on an area of over 80 thousand ha with (70%) concentrated in the south part of Kazakhstan [

14]. The melon fly Zeugodacus cucurbitae (Diptera, Tephritidae) is an important, global, agricultural pest [

15]. Z. cucurbitae can infest more than 130 host plants including vegetables and fruits, but mainly gourd and nightshade plants, such as cucumber, pumpkin, melon, watermelon, bitter melon, tomato and eggplant. Adult insects are yellow flies with black spots 5–7 mm long. Mass flight of adults to feeding places begins in spring, when the soil warms up to 20 °C. During this period, the process of formation of the first fruits already begins in plants. After 6–7 days, insects start laying eggs in immature fruits to a depth of 2 mm. After 2–7 days, the eggs ripen, larvae hatch from them, which live in fruits and feed on their tissues. The larval phase lasts 8–13 days, and even longer in the last generation. The larva of the melon fly has a yellowish-white cylindrical body 8–10 mm long with two processes on the sides. Usually it gnaws through the fruit, comes out and in the soil, forms a chrysalis at a depth of 12–13 cm. But often this process occurs in the fruits. In summer, the pupa develops within 13–20 days. Winters in soil at a depth of up to 18 cm.

Adult flies feed on fruit juice by piercing them with their ovipositor. The larvae consume the seeds and tissues, making the fruit completely unusable. Their damage is evidenced by small tubercles at the sites of puncture by the ovipositor and holes in the exit zone [

14].

The use of agricultural waste as a secondary raw material to produce a variety of valuable commercial products is of economic and agroecological relevance. The importance lies in improving the environmental situation, lowering expenses, and boosting the environmental safety of the products.

The current research aimed to discover how the properties of sierozem soil alters when a mixture of vermicompost, bentonite, and sulphur-perlite-containing waste (SPCW) is applied, and what possibilities there are to produce environmentally safe cucurbits.

We have established for the first time that the use of only the above components allows us to obtain a new simultaneous effect - an increase in insecticidal action against melon flies and the production of environmentally friendly gourds with high yields. Insecticide-fertilizer in solid form retains its physicochemical and biological properties over a wide temperature range, does not require special conditions for transportation and storage.

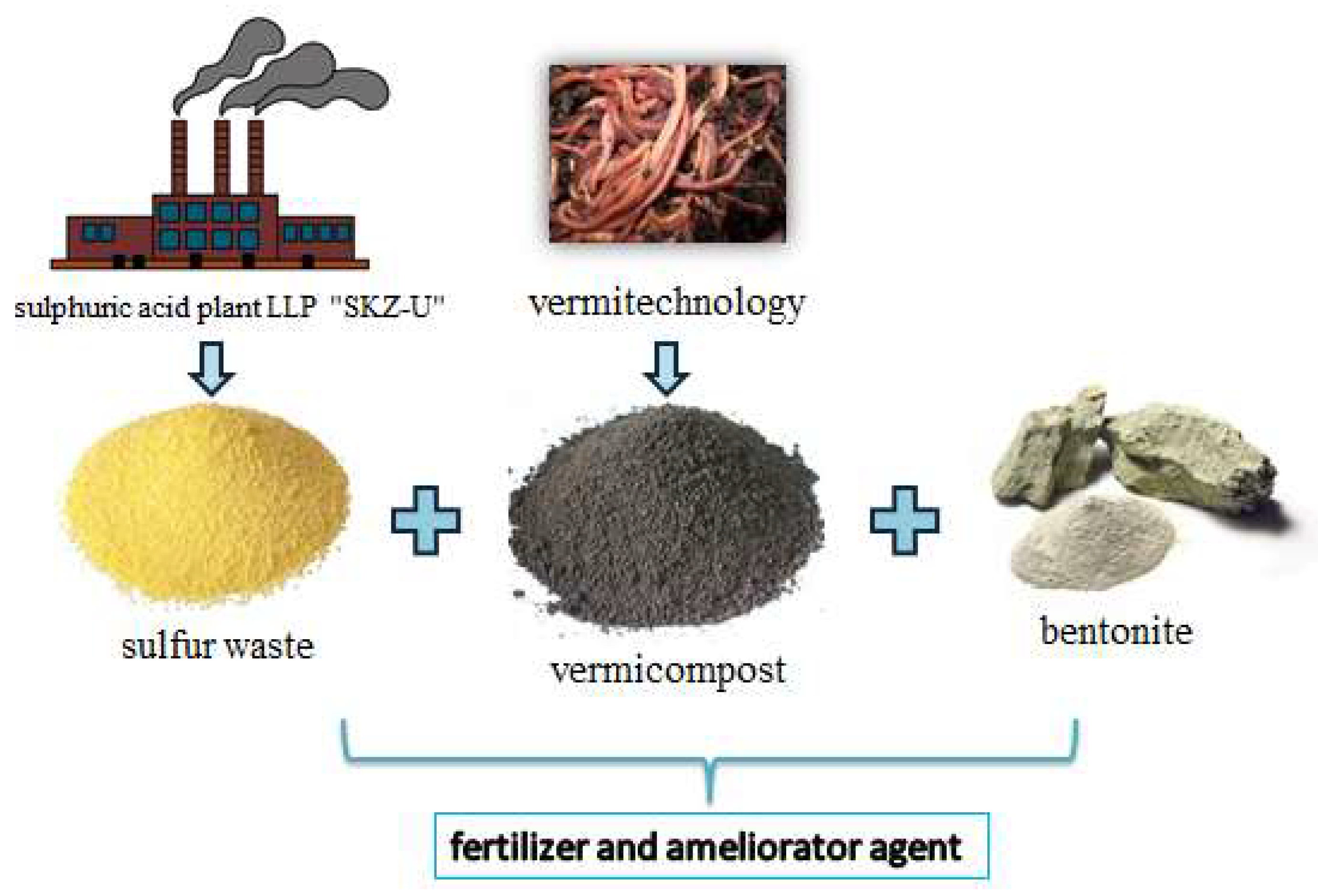

Below in

Figure 1 shows the schematic way of obtaining insecticidal fertilizer ameliorant.

Metagenomic soil analysis is a powerful tool for understanding the microbial communities present in soil. It involves analyzing the genetic material (DNA or RNA) of all microorganisms present in a soil sample, without the need for culturing or isolating them. The importance of metagenomic soil analysis lies in its ability to provide a comprehensive view of the microbial diversity and function in soil, which is critical for various fields, including agriculture, environmental science, and biotechnology [

16].

Here are some specific ways in which metagenomic soil analysis is important:

Understanding soil health: Soil is a complex ecosystem that contains a diverse array of microorganisms, which play a crucial role in nutrient cycling, plant growth, and soil health. Metagenomic soil analysis can provide a detailed understanding of the microbial community composition and their functions in soil. This information can help identify beneficial microorganisms, potential pathogens, and other factors that affect soil health.

Identifying novel microorganisms and functions: Metagenomic soil analysis can uncover new microorganisms that have not been previously described or cultured. These microorganisms may have unique metabolic pathways or functions that could be harnessed for biotechnological applications, such as the production of biofuels or bioremediation of contaminated soils.

Monitoring soil changes: Metagenomic soil analysis can be used to monitor changes in soil microbial communities over time or in response to environmental stressors. For example, it can be used to assess the impact of agricultural practices, such as fertilization or tillage, on soil microbial diversity and function.

Developing sustainable agricultural practices: Metagenomic soil analysis can help identify microorganisms that contribute to plant growth promotion, disease suppression, and nutrient cycling. This information can be used to develop sustainable agricultural practices that reduce the need for synthetic fertilizers and pesticides, leading to improved soil health and reduced environmental impact.

In summary, metagenomic soil analysis is a powerful tool for understanding soil microbial diversity and function. Its applications in agriculture, environmental science, and biotechnology make it an important area of research for understanding and managing soil ecosystems.

Molecular methods are promising in the determination and study of the majority of uncultivated microorganisms, which allow studying the properties of microbiomes in situ, without isolating inoculums from pure cultures. Metagenomics is the analysis of the total genetic material isolated from an entire biological system. The highest priority in metagenomic systems is the analysis of the 16S rRNA gene, on the structure of which the modern phylogenetic classification of bacteria is based.

2. Materials and Methods

The studies carried out in 2020-2022 covered the sierozem soils of Zhanakorgan (Kyzylorda region), bentonite clays of Sauran (Turkestan region), vermicompost obtained at the production site of the research institute "Ecology", Khoja Ahmed Yasawi Kazakh-Turkish International University, and silicon-containing waste from the sulphuric acid plant LLP "SAP-U" (Kyzylorda region).

Early maturing cucurbit varieties were selected for the study: melon (Torpedo), watermelon (Crimson), and pumpkin (Matilda). They were grown in the south of Kazakhstan, specifically in the Turkestan and Kyzylorda regions. Natural and climatic conditions favour their cultivation: a lot of heat, solar radiation, and mostly clear and dry weather. Melon fly (Myiopardalis pardalina) is one of the most dangerous cucurbit pests, causing significant damage.

The melon (Torpedo) is a great lover of warmth, its root system is shallow, and it grows more in width so that a fertile layer of 20 cm is sufficient. The watermelon (Crimson suite) is a widely grown variety that can withstand dry climates. The pumpkin (Matilda) is pear-shaped and has a light orange or beige colour with a firm crust.

In the south of Kazakhstan, melon pests have so far caused massive damage to about 7 thousand hectares of land used for growing melons, watermelons, and pumpkins. In the absence of effective control measures, villagers in the Kyzylorda and Turkestan regions have been compelled to abandon cucurbit cultivation. "Vermiserbent" was tested to control the melon fly in cucurbit fields, taking into consideration the unique properties of all its components.

The melon fly is harmful in the larval stage. The melon fly larvae from infested crops migrate into the soil and usually hibernate at a maximum depth of 15-20 cm. In spring, when the temperature rises to 15˚C, the adult individuals of the melon fly hatch from the larvae. To prevent the emergence of melon flies from the larvae, it is, therefore, necessary to eradicate them from the uppermost soil layers before spring.

If spread en masse in the fields, the yield of melons and pumpkins can drop by 80-90%, and almost all produce becomes unfit for consumption. Damage to cucurbit fruit occurs with the involvement of both an adult fly and larvae. If the larvae damage the fruit from the inside, then the adult flies puncture the peel from the outside. At the puncture sites, the flies lay eggs that turn into larvae after 2 days. The larvae bore into the flesh of the fruit, make movements, and rotting occurs in these places, which serve as foci for the accumulation of pathogens and bacteria.

2.1. Experimental design

The total area of the (Zhanakorgansky district, Otrarsky district, Savransky district) of each experimental field was 250 m2, each plot was 40 m2, and the settlement area was 20 m2. The plot options were laid out randomly in 4-fold replication. The scheme of the experiment was as follows: 1) the original soil without the incorporation of foreign components (control); with incorporation: 2) combination of 20 t ha-1 vermicompost, 2 t ha-1 bentonite, and 5 t ha-1 SPCW.

A 15-20 t ha-1 (or 3-5 kg m-2) of "Vermiserbent" (ratio 10:1:2.5) was applied to the soil surface of the experimental field previously infested with melon fly in autumn. Atmospheric precipitation during the autumn application partially dissolved the components, allowing the larvae in the surface layers to be destroyed. In early spring, the top layer of soil was then loosened (up to 20-30 cm), which allows the destruction of the remaining larvae.

To sterilise the seeds before sowing, they were immersed for up to 10 h in an extract obtained by boiling the waste under study with water (at a ratio of 1:5). The extract was diluted 10 times with water for prophylactic purposes and the plants in the experimental plots were sprayed. The plant treatment was repeated twice at a rate of 2 L ha-1. The extract decomposes in the air to form hydrogen sulphide, the odour of which repels melon flies and other pests. The first treatment was performed during the first leaf formation, while the second treatment was performed during the formation of loops. In the control plot, the field was treated with a solution of the insecticide "Rapira" (2 L ha-1).

2.2. Agrochemical analysis

The agrochemical parameters of soil were determined using the following methods: humus - according to Tyurin in the modification of Nikitin [17-18]; pH - according to GOST 26483-85 [

19]; exchange cations - according to Gedroits with trilonometric ending; total nitrogen (N) - according to Kjeldahl [

20]; hydrolytic acidity – according to GOST 26212-91 [

21]; mobile phosphorus (P) and exchangeable potassium (K) – according to GOST 26207-91 [

22].

The water extraction method was used to extract easily soluble salts from the soil. In a 750 cm3 dry flask, 100 g of air-dry soil was passed through a 1-2 mm diameter sieve, and 500 cm3 of distilled water (dH2O) without CO2 was added, sealed with a rubber stopper and shaken for 5 minutes. The aqueous extract was then filtered with a tightly pleated philtre.

The average sugar content was determined according to GOST 8756.13-87 [

23]. Sampling was carried out according to GOST

26671-2014 [

24], while sample preparation - according to GOST

26313-2014 [

25].

The mass fraction of protein in cucurbits was determined using the biuret method modified by Jennings [

26]. Approximately 5.0 g of the sample was weighed to an accuracy of ±0.001 g and placed in a dry 250 cm

3 Erlenmeyer flask with a stopper. The sample was measured with a 0.1 cm

3 graduated cylinder under a draft of 2 cm

3 carbon tetrachloride to extract the fat, and then 100 cm

3 Biuret reagent was added with a pipette. The sealed flask was shaken on a mechanical shaker for 60 min. Then the extract was centrifuged at 4500 rpm for 10 min. A transparent centrifugate was added to the cuvette of a photoelectric colourimeter with a solution layer thickness of 5 mm. The optical density was measured at 550 nm. The protein content in the sample (mg) was determined using a calibration curve.

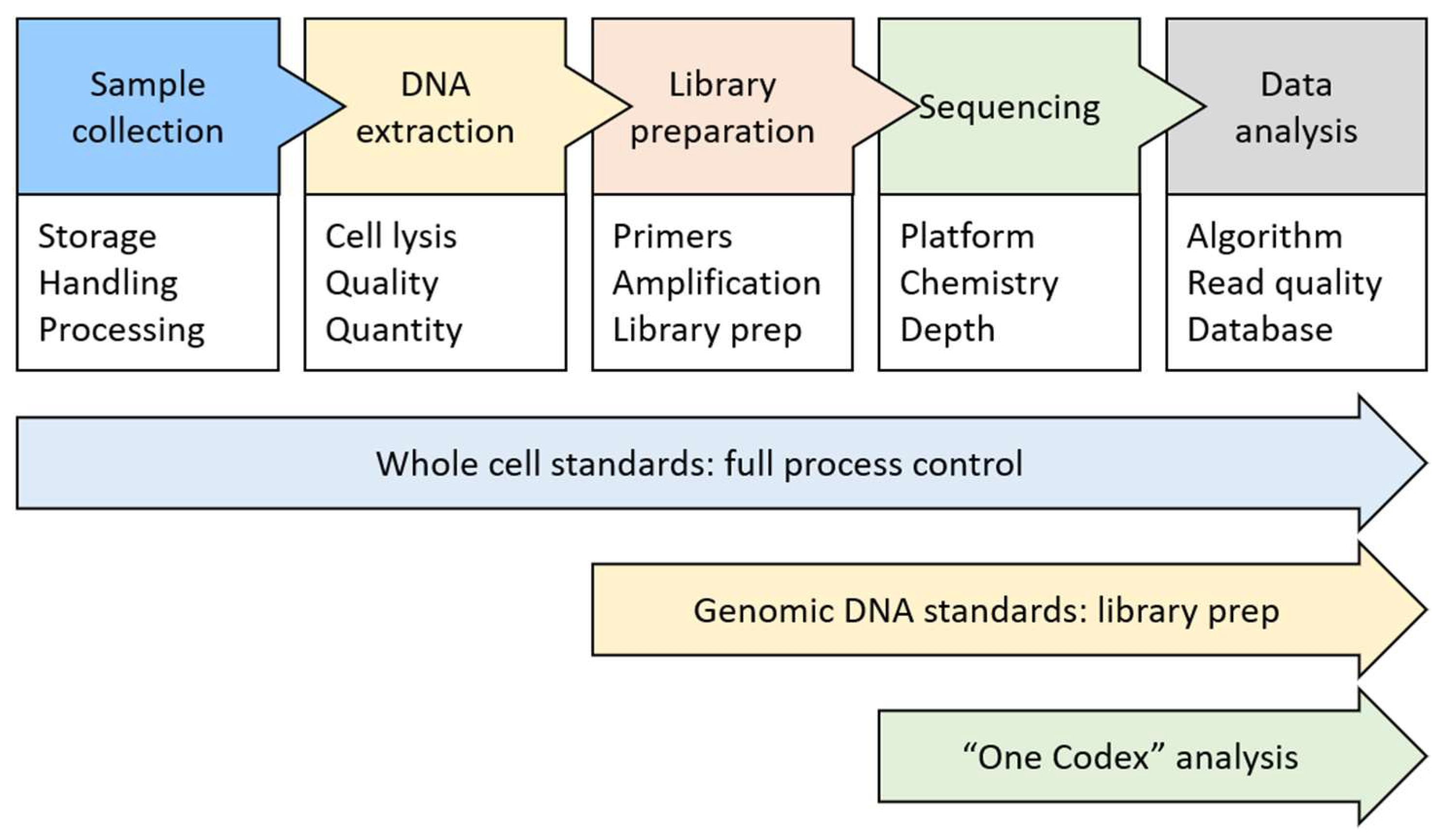

2.3. Metagenomic analysis.

The analysis of the phylogenetic structure of microbiomes in the soil samples was carried out on a HiSeq device from Illumina (USA) at the University of Inner Mongolia (China) according to the standard protocol [

27]. The full description of the Illumina platform is presented on the official website of the company

https://www.illumina.com. The general process of metagenomic analysis includes several stages (

Figure 2). Each stage was performed according to the manufacturer's standard [

28].

2.4. Soil horizon method

The soil of the experimental field was light sierozem soil. They have a profile with fuzzy transitions between horizons and are well permeable to water. The parent rock is loam. Humus reserves in the soil profile were found to be mostly concentrated in the upper layer of 0-20 cm (0.95-1.23%, 26.5-27.4 t ha-1), while it dropped moving downwards in the profile. Despite the low percentage, it can be found up to half a metre. These soils can be suitable for growing cucurbits and other crops after fertilization and regular irrigation.

A soil pit is dug with sheer, even walls, first to a depth of 0.6 m, while throwing out the soil mass only along its longitudinal (lateral) walls. In the process of digging the cut, layer by layer of soil is sequentially removed. In this case, various genetic horizons (subhorizons) are opened.

After reaching a depth of 0.6 m, a step-ledge is made with a height of about 0.4 m, then the pit is deepened by another 0.4 m and another step is made, etc. Usually, three steps are made in a complete soil section. Their width depends on the granulometric composition of the studied soil: in easily shedding soils (sandy-loamy sandy) they are wider (about 0.4–0.5 m), in more stable (clay-loamy) they are narrower (0.3 m).

At the end of the deepening of the soil cut, the front (front) and side walls are cleaned with a shovel, while the bayonet of the shovel turns in the opposite direction so that the handle mounted on it does not interfere.

A measuring (for example, tailor's) tape is attached to the upper edge of the cleaned front wall with a pin or needle, which is stretched down the center to determine the thickness of individual horizons (subhorizons) of the soil.

The left side of the front wall (to the left of the measuring tape) remains unaffected by the work on describing the soil profile, the right (working) one is intended for the removal of soil samples.

The fresh section is carefully examined and genetic horizons and subhorizons are preliminarily distinguished. It is recommended that the final selection of soil horizons (subhorizons) be carried out as the final stage in the description of the section after each of the studied features (color, moisture content, granulometric composition, structure, etc.) has been described. Preliminary identification of genetic horizons (subhorizons) is carried out on the basis of a change in color in the soil stratum from top to bottom.

Horizons (subhorizons) are described in order from top to bottom.

In the process of describing the soil profile, samples are taken - material for laboratory work of the necessary analyzes. Samples are wrapped in paper or placed in special bags along with labels indicating the location of the pit - the number of the description point.

2.5. Method for determination of nitrogen.

A 0.200 g sample of soil is taken on a laboratory balance and placed in a heat-resistant test tube with a capacity of 50 ml. 2 ml of a solution with a mass fraction of hydrogen peroxide of 30% is poured into the test tube along the wall, wetting the entire sample of soil with it. After 2 minutes, 3 ml of concentrated sulfuric acid containing selenium is added with a dispenser. The contents of the test tubes are stirred in a circular motion, placed in a device for heating test tubes, placed in a fume hood and the test tubes are gradually heated to 400 ˚C. Ashing is carried out at this temperature until the solution is completely discolored. Then the solution is left to cool at room temperature and topped up with distilled water to the mark on the test tube. If heat-resistant tubes or a heating device are not available, 50 ml Kjeldahl flasks may be used. In this case, after the organic matter has been ashed, the solution is quantitatively transferred into volumetric flasks with a capacity of 50 ml and topped up with distilled water to the mark.

1 ml of a clear solution obtained by decomposition of the soil is transferred by a dispenser into a dry flat-bottomed or conical flask with a capacity of 100 ml. 45 ml of the working staining reagent is added to the solution with a dispenser, 2.5 ml of the working solution of hypochlorite is added. After adding each reagent, the solution is stirred, the flask with the solution is left for 1 hour for the formation of a stable color. The optical density of the colored solution is measured relative to the zero solution in a cuvette with an absorbing layer thickness of 1 cm at a wavelength of 655 nm.

3. Results

The agrochemical properties of the Sierozem soils used in the study were as follows: pH (KCl) was 5.90-6.50; hydrolytic acidity was 2.38-2.76 mEq./100 g soil; mobile phosphorus (P) content was 25.0-31.0 mg kg-1; total nitrogen (N) was 0.095-0.117%; exchangeable potassium (K) content was 120-130 mg kg-1; total absorbed bases were 13.6-14.0 mEq./100 g soil. Calcium (Ca) cations predominated in all horizons, with a concentration of 7.5 mEq. or ~54.3% in a layer of 0-40 cm.

An investigation of the soil aqueous extract was carried out to gain information on the composition and amount of easily soluble salts, as well as the degree and type of salinisation. Carbonates, bicarbonate, chlorides, and sulphates of calcium (Ca), magnesium (Mg), and sodium (Na) are the most prevalent salts that induce soil salinisation and harm plants. When the salts concentration reaches 0.1% soil dry soil weight they begin to have a negative impact on the quality and volume of crop yields. Table 1 shows the results of the chemical analysis of the aqueous extract obtained from absolutely dry soil before treatment with fertilizer - ameliorant.

According to the aqueous extract data, the sierozem soil studied was not saline. The salt content in the upper layer from 0-100 cm varied between 0.104 and 0.112% (

Table 1). The aqueous extract contained no carbonates. The chlorine ion concentration in the upper 0-100 cm (1 m) layer did not surpass the toxicity threshold, averaging 0.010%. At the same time, bicarbonate ions dominated, accounting for more than 41% of the total salts.

An analysis of the cationic composition of the aqueous extract revealed a drop in calcium (Ca) reserves and an increase in sodium (Na) as it passes from the upper to the lower horizon. The content of magnesium (Mg) cations in a metre (0-100 cm) layer was evenly distributed. The alkalinity of the soil can be explained by a relatively high content of sodium and calcium bicarbonate (

Table 1).

During the transition from the upper to lower soil horizons, a decrease in the quantitative content of humic substances, an increase in the pH of the medium, and a decrease in the fine fractions in the granulometric composition were observed.

Table 2 shows initial the mechanical composition of the profile of the sierozem soil of the Otrar and Sauran districts of the Turkistan region and the Zhanakorgan district of the Kyzylorda region.

Sufficiently high soil alkalinity can be explained by a precipitation shortage in the region. The removal of weathering and soil formation products from soils and parent rock is limited in this regard. A high alkali level in the soil is well known to be detrimental to most crops, including melons. Plant metabolism is disrupted in an alkaline environment, and the solubility and availability of nutrients, as well as iron, copper, manganese, boron, and zinc, are reduced. In the case of an alkaline reaction, plant toxic chemicals, such as soda and sodium aluminate, develop in the soil solution [29-32].

When the pH rises sharply, the root hairs of the plants experience alkali burn, which has a negative effect on their further development and can lead to death. The strongly alkaline soils of the study area have pronounced negative agrophysical properties, which are accompanied by a strong peptisation of soil colloids and humic substances dissolution. These soils become textured (lose their structure), excessively sticky when wet and hard when dry, with poor filtration and unsatisfactory air conditions.

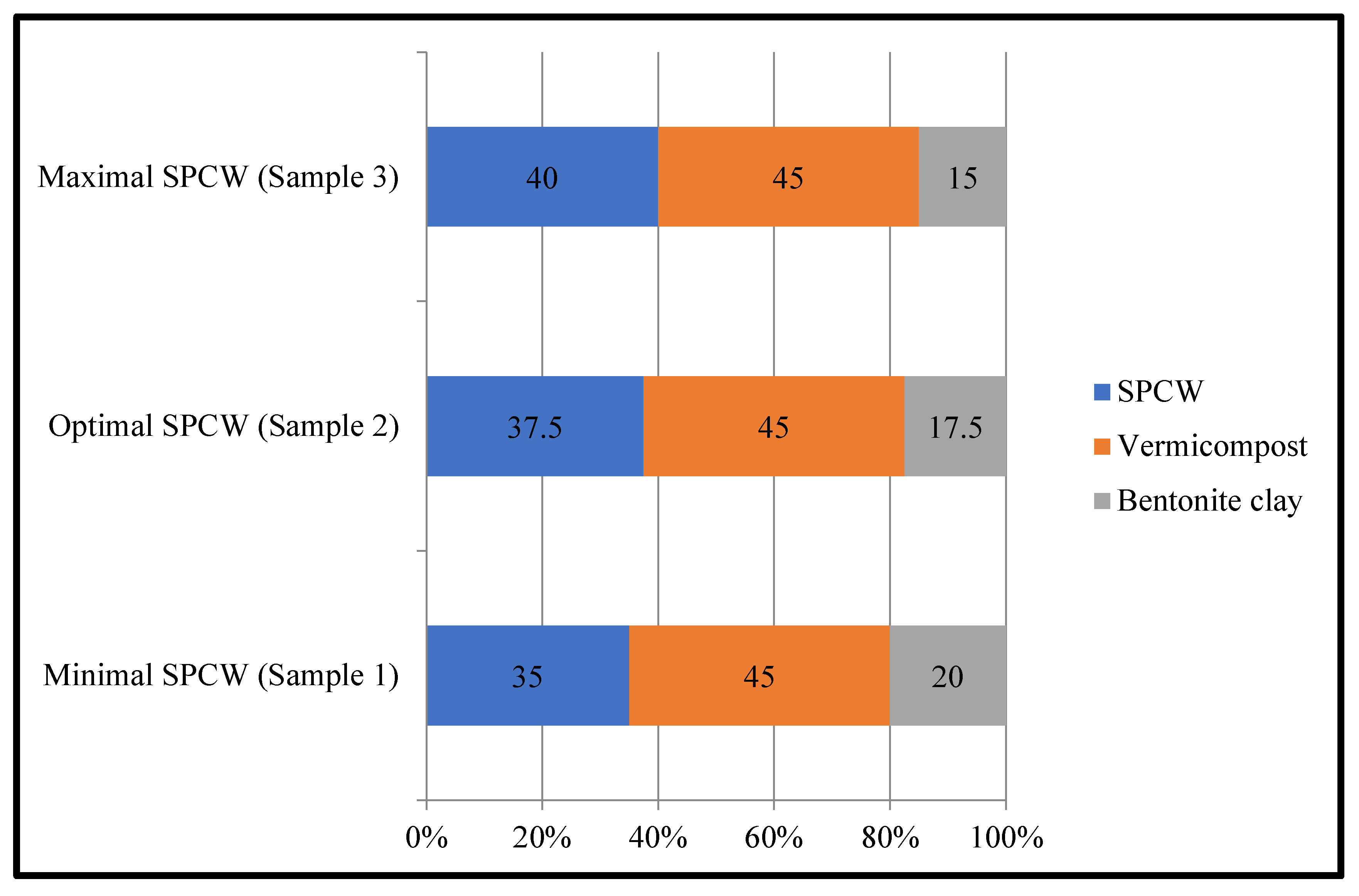

Only extensive recultivation measures with the inclusion of organomineral compositions can improve these alkaline soils. As a fertiliser and reclamation agent (FRA), a "Vermiserbent" mixture of vermicompost, bentonite, clay, and SPCW was chosen (

Figure 3).

The optimal ratios of the "Vermiserbent" components were determined based on laboratory, extended laboratory, and field trials on farm soils. The components of "Vermiserbent" are characterised by the properties described below.

All components of "Vermiserbent" contain calcium compounds. Calcium displaces the absorbed sodium, making the Solonetz horizon more structurally and water permeable, consequently allowing salts to be washed out of the lower horizons.

Vermicompost improves soil fertility and structure, has high agrochemical and growth-promoting properties, and delivers a consistent, high, ecologically safe crop yield with outstanding flavour. Vermicompost has great physical and chemical properties, including structural water resistance (95-97%) and complete moisture capacity (200-250%), allowing it to be used not only as a fertiliser but also as an effective ameliorant and soil conditioner.

Bentonite from the Urangai deposit (Turkestan region) contains 60-70% montmorillonite minerals. It is a veritable treasure trove of natural trace elements. Due to the presence of the main nutrients K (0.8-1.4%), N (0.8-1.0%), P (0.08-0.10%), a complex of trace elements, SiO2 (57.5%), and CaCO3 (13.5%), bentonite can be utilised as a fertiliser and an ameliorant.

Waste from sulphuric acid production contains in its composition 10 to 20% sulphur compounds (free sulphur, polysulphides, thiosulphate, sulphate, mercaptans), perlite, gypsum, and slaked lime [

33]. When introduced into the soil, it not only acts as a fertiliser and ameliorating agent, but it also shows an insecticidal action that kills many pests.

The yield, marketability, and calorie content of melon, watermelons, and pumpkins from the control and trial plots were determined during the study (

Table 3).

After using "Vermiserbent" the nutritional value of melon is defined by the following standard indicators (g per 100 g of melon): 88.5 g water; 0.63 g proteins; 0.25 g fat; 0.77 g carbohydrate; 0.02 g ascorbic acid; 0.6 g fibre; 0.4 g pectin; and 0.5 g ash.

The sugar composition in watermelon was as follows: 1.82% glucose; 2.96% fructose; 2.87% sucrose. In the pulp of the fruit, the sugar is 12 g per 100 grams. Fructose predominates in watermelon.

Pumpkin (Matilda) refers to an early maturing variety. The content of the main constituents in 100 g of fruit is as follows: 1.0 g protein; 0.1 g fat; 44.2 g carbohydrate; 89.3 g water.

In terms of aesthetics, the produced melons, watermelons, and pumpkins are not inferior to the control samples. The nitrate content were below the permissible standard values. The quantitative composition of macro- and microelements in the melons and watermelons cultivated in both the control and experimental plots showed no significant variations. The melons and watermelons from the experimental plots, on the other hand, were juicier and sweeter than those from the control plot. The experimental plots produced more melons, watermelons, and pumpkins than the control plots, and the fruits were larger as well.

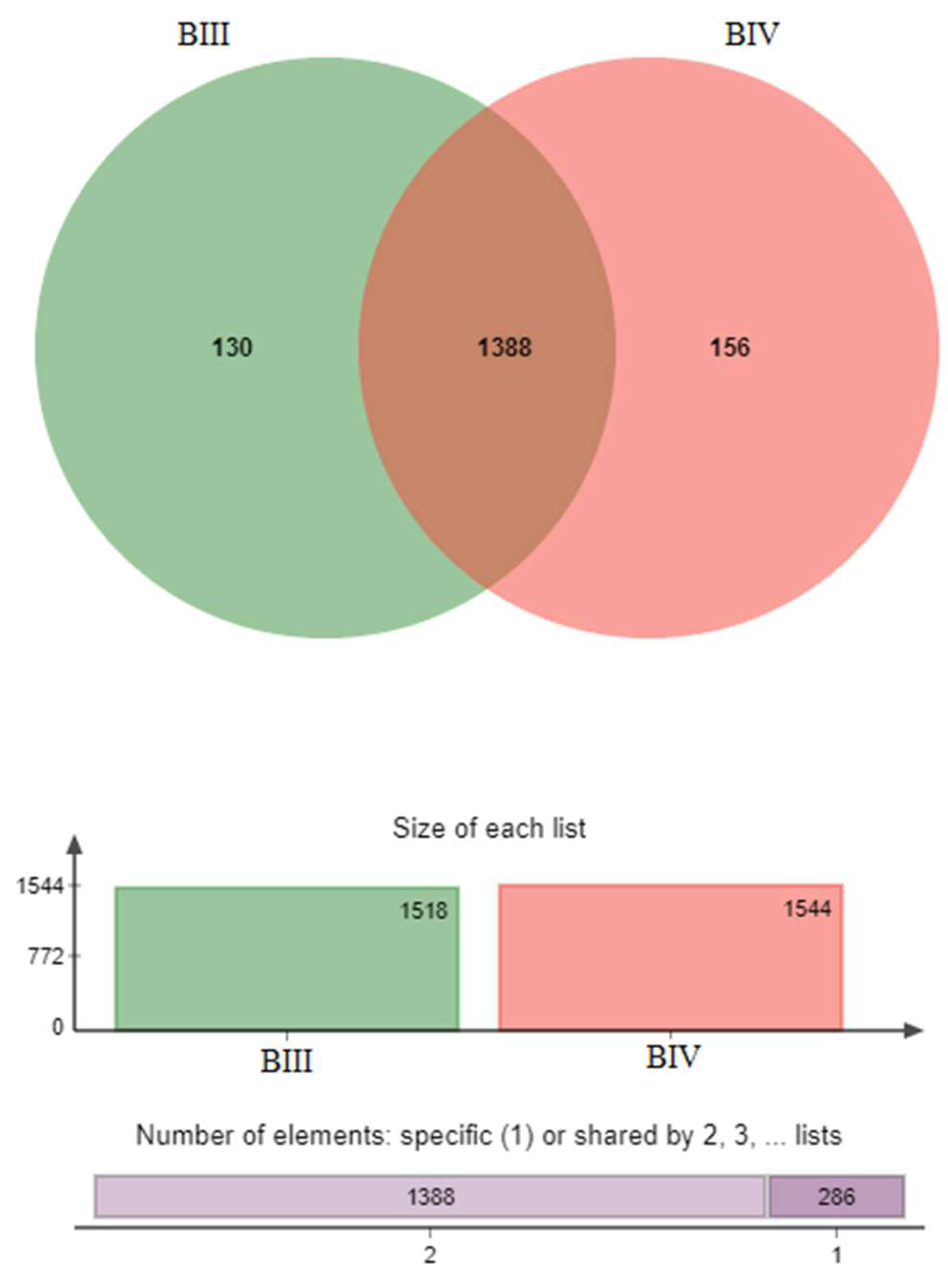

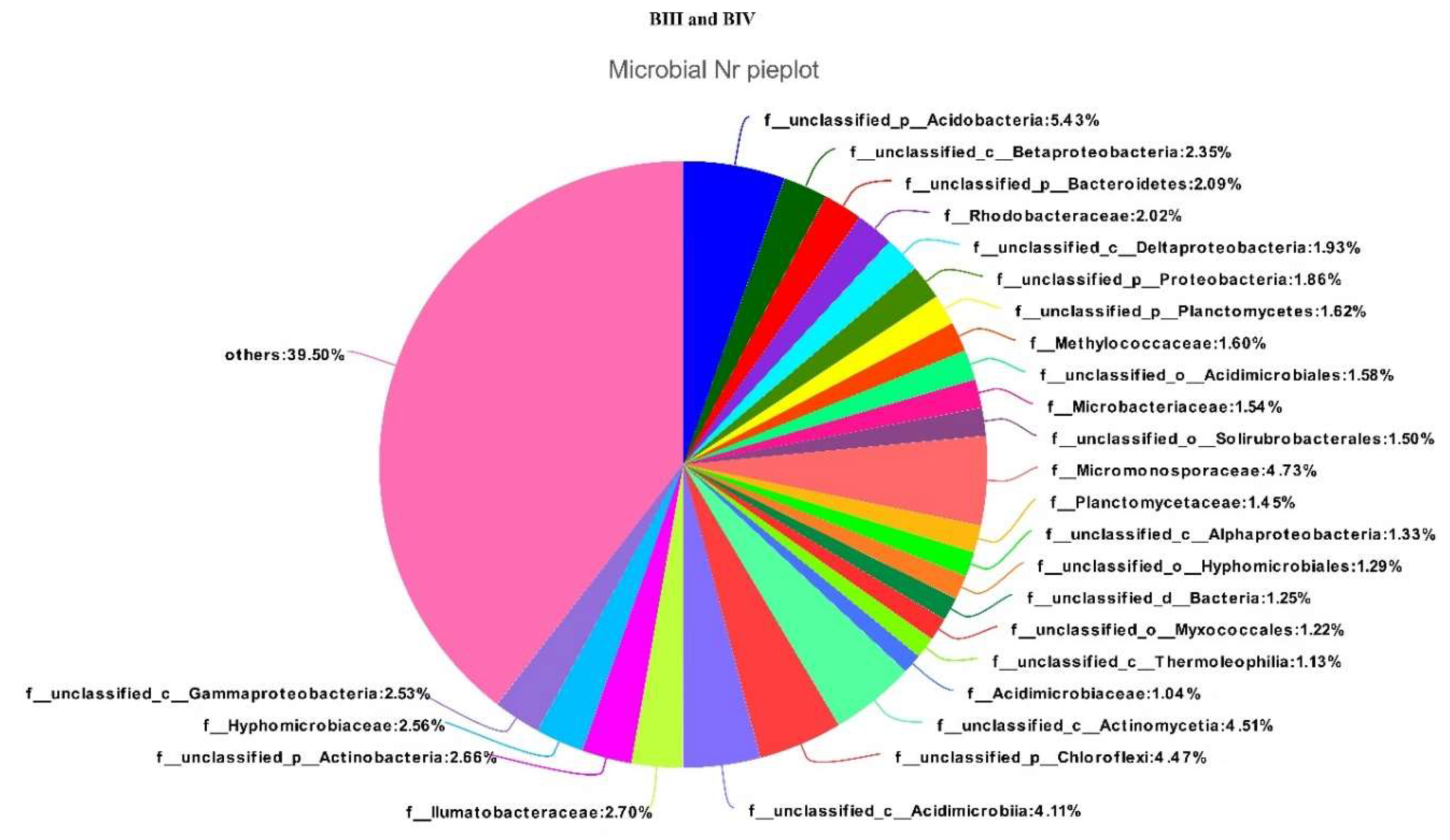

We studied the microbiota of substrates obtained using vermitechnology. Changes in the composition of bacteria during the passage of manure through the digestive tract of worms are usually considered by comparing the complexes of microbial cells of manure consumed by worms and coprolites. To understand the mechanisms of change in the microbiota of manure passing through worms, it is also necessary to know the composition of bacteria. Therefore, the taxonomic composition and abundance of bacterial species in soil and coprolite were studied (after treatment with vermiserbent) (

Figure 4 and

Figure 5). In the microbiological analysis of the soil before and after treatment are designated BIII and BIV.

The overlapping part indicates the common species in several sample groups, the non-overlapping part indicates the unique species of the sample group, and the number indicates the corresponding number of species (

Figure 4). This means that there are 1388 species in the two samples, and 130 species only in sample BIII, and 156 species in sample BIV.

The prokaryotic BIII and BIV community is mainly composed of representatives of

Acidobacteria sp. (5.43%),

Actinomycetia (4.51%),

Chloroflexi (4.47%),

Micromonosporaceae (4.73%)

Acidimicrobiia (4.47%). Other identified species 1.04 to 2.66% and not certain species 36.50% of the total number of species (

Figure 5).

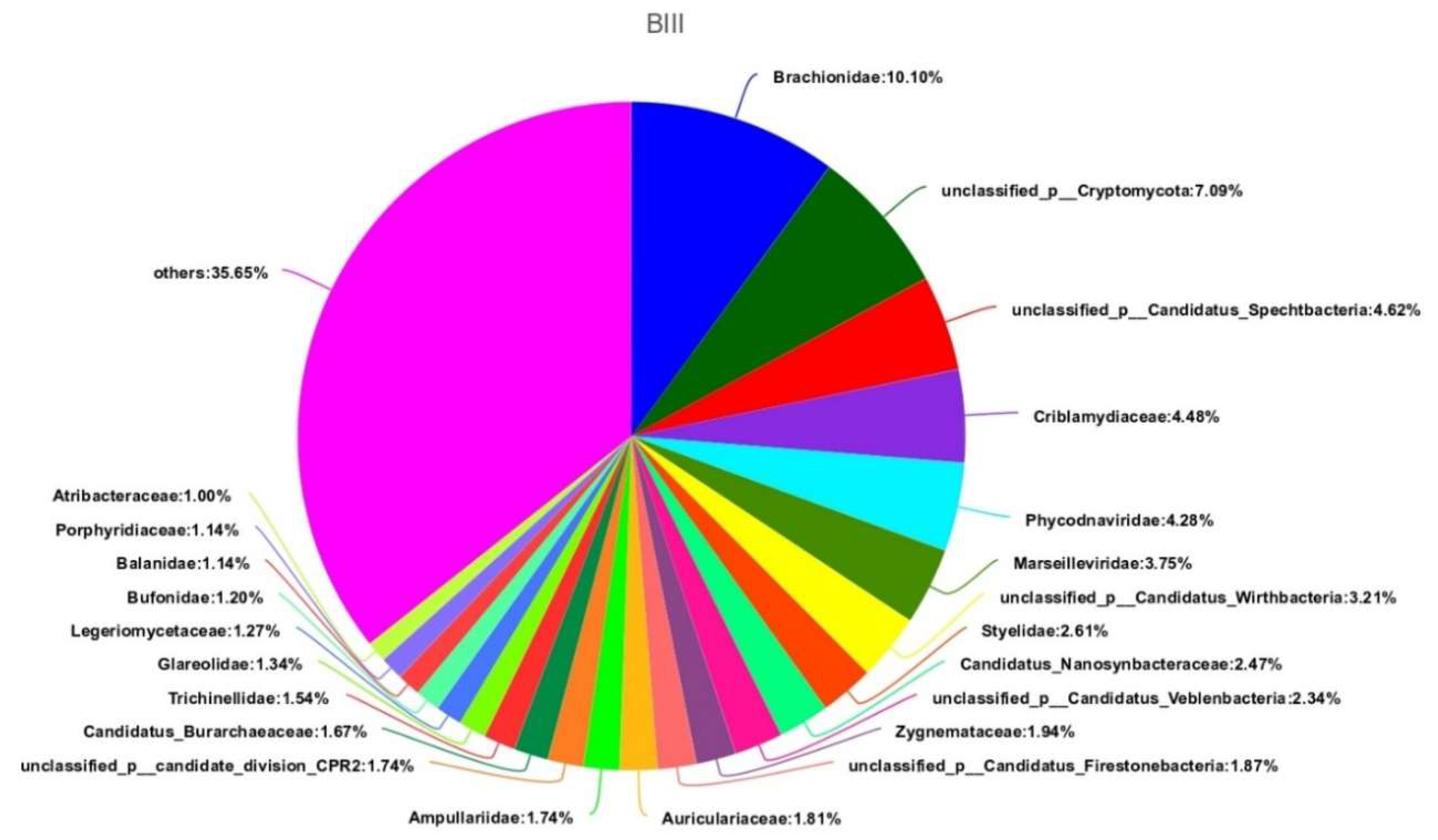

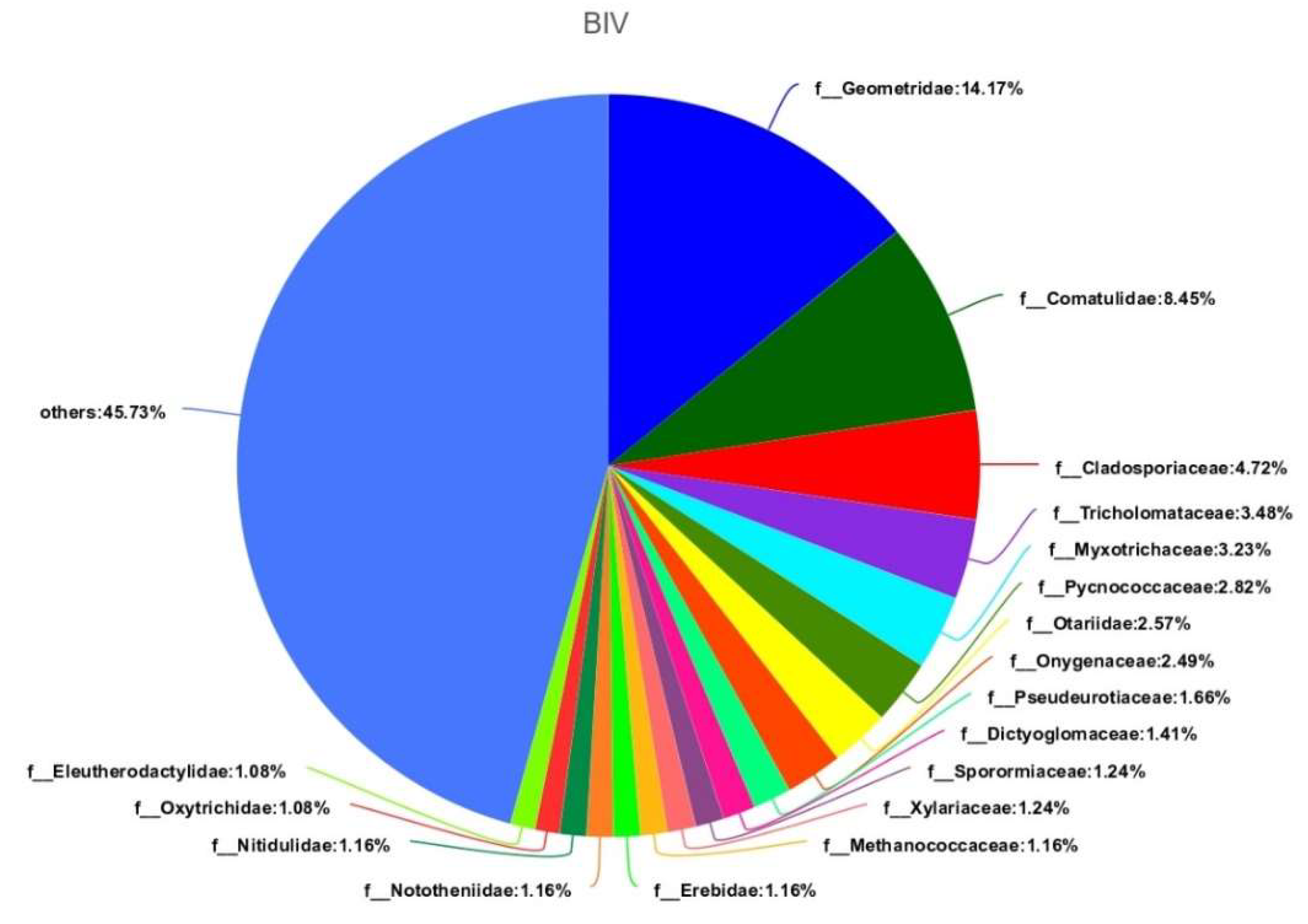

If you look at the samples separately, then there will be the next

Figure 6 and

Figure 7. In these pictures, we will see their diversity, that they are rich in species composition in the soil after the experiments.

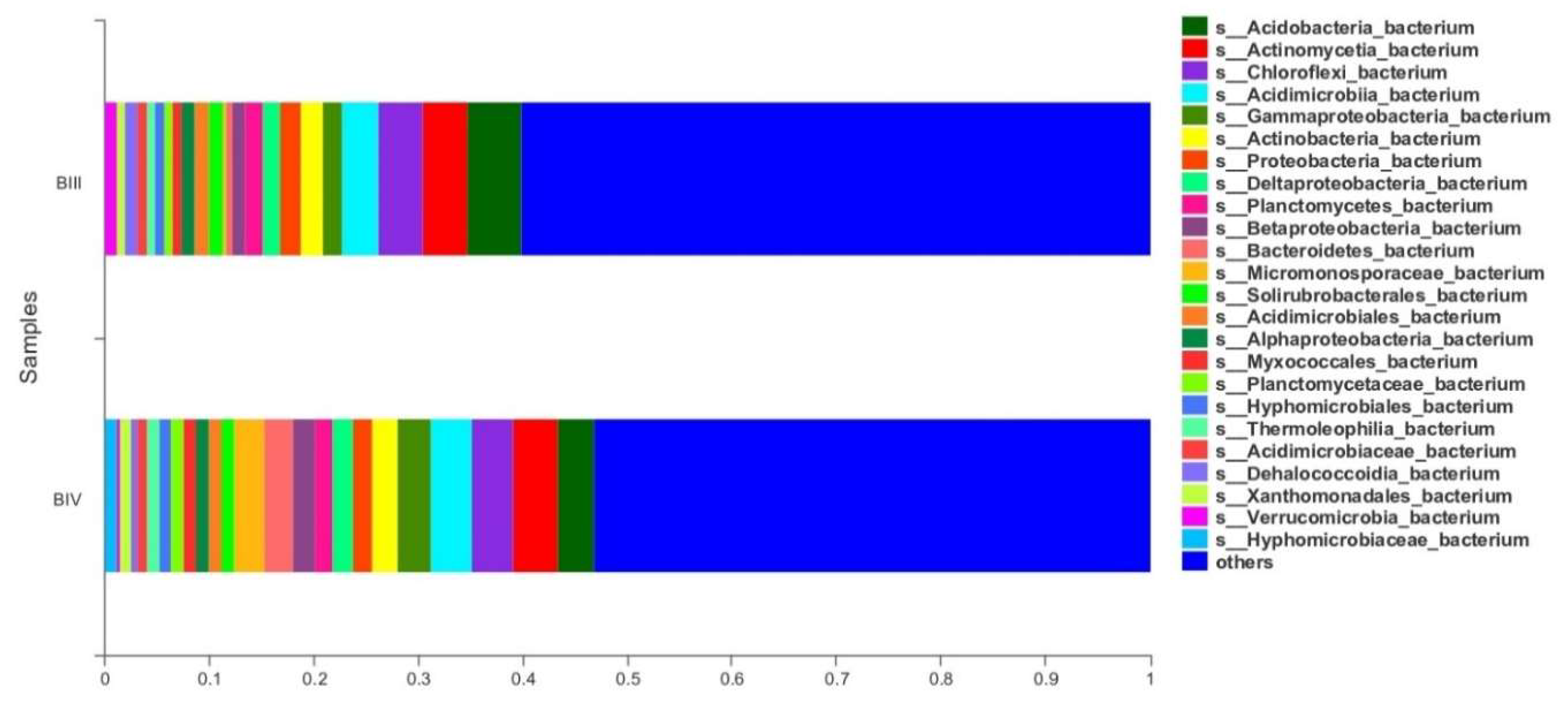

Comparatively, two samples can be shown as follows in percentage terms (

Figure 8). The abscissa/ordinate is the name of the specimen, the ordinate/abscissa is the proportion of species in the specimen, the bars of different colors represent different species, and the length of the bar represents the proportion of species.

The work carried out makes it possible to relate the features of the structure and diversity of microbial communities, studied by sequencing the 16S rRNA gene, to the features of soil properties and their genesis.

The presence of a large number of microorganisms in a soil sample could indicate a healthy and fertile soil. Microorganisms play a critical role in soil health and fertility by breaking down organic matter, releasing nutrients, and maintaining soil structure. Some microorganisms such as bacteria, fungi, and protozoa can also help to control plant diseases and pests. Additionally, soil microorganisms can help to sequester carbon, which can help mitigate climate change.

4. Conclusions

The new agent "Vermiserbent", when applied to the soil, influences the formation of agrophysical (structure, bulk density, air permeability, water holding capacity, etc.), physicochemical, and biological properties of the soil. Intensification of physiological and biochemical processes by the agent "Vermiserbent" in cucurbits accelerates the passage of phenophase and shortens the duration of the vegetation period by an average of 7-10 days. The developed composition is a source of plant nutrients. Further research should be focused on determining the biological effect of insecticide ameliorant on melon flies. It would also be interesting to use insecticide – ameliorant on other agricultural pests.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, S.G. and A.A.; methodology, Y.Zh.; software, T.K.; validation, H.A., Y.Zh. and K.T.; formal analysis, S.G.; investigation, A.A.; resources, T.K.; data curation, H.A.; writing—original draft preparation, Y.Zh.; writing—review and editing, T.K.; visualization, S.G.; supervision, A.A.; All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

The data used to support the findings of this study are included within the article.

Acknowledgments

This study did not receive any funding in any form.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that there are no conflicts of interest.

References

- Basic technologies for processing industrial and municipal solid waste: [proc. allowance] / L. B. Khoroshavin, V. A. Belyakov, E. A. Svalov; [scient. ed. A. S. Noskov]; Ministry of Education and Science Ros. Federation, Ural. feder. un-t. - Yekaterinburg: Ural Publishing House. un-ta, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Chertow, M. Scholarship and Practice in Industrial Symbiosis: 1989-2014/M.Chertow, J.Park // Taking Stock of Industrial Ecology, - 2016. – Ch. 5.- P. 87-116.

- E.Andersson, O. E.Andersson, O.Arfwidsson, V.Bergstand et al.Industrial Symbiosis in Stenungsund. 2013. – http://www.industriellekologi.se/symbiosis/stenungsund.

- Domenech, T. Structure and Morphology of industrial symbiosis networks: The case of Kalundborg / T.Domenech, M.Davies. //Procedia – Social and Behavioral Sciences,10,79-89, 2011.

- A. Mavropoulos, D. A. Mavropoulos, D. Wilson, S. Velis, J. Cooper, and B. Eppelquist, Globalization and Waste Management. C: Step 1, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Ratnawati, B. ,Yani M., Suprihatin S., Hardjomidjojo H. Waste processing techniques at the landfill site using the material flow analysis method. DOI 10.22034/gjesm.2023.01.06.

- Rasskazova, A.V. The increase of effectiveness of power utilization of brown coal of Russian Far East and prospects of valuable metals extraction / A.V.Rasskazova, T.N.Alexandrova, N.A.Lavrik // Eurasian Mining. 2014. Vol.1. P.25-27.

- Processing of industrial and domestic wastes (Technology and equipment for the protection of the lithosphere): Training manual / Workshop / Vetoshkin A.G. - M.: DIA, 2015.-400 p.

- Marchenko, L.A. , Artyushin A.A., Smirnov I.G., Mochkova T.V., Spiridonov A.Yu., Kurbanov R.K. Technology for the application of pesticides and fertilizers by unmanned aerial vehicles in digital agriculture. Agricultural machines and technologies. 2019;13(5):38-45. [CrossRef]

- Environmental impacts of pesticides. — 16. — [Electronic resource]. Access Mode: https://www.slu. 20 May.

- A.S. Mezhevov. The use of biomeliorants to increase the productivity of low-humus soils. Scientific journal of the Russian Research Institute of Land Reclamation Problems, No. A.S. Mezhevov. The use of biomeliorants to increase the productivity of low-humus soils. Scientific journal of the Russian Research Institute of Land Reclamation Problems, No. 2020. [Google Scholar]

- [Electronic resource]: http://www.bibliotekar.ru/2-9-67-himiya-pochvy/34.

- Sulfur-containing waste from sulfuric acid production of CKZ-U LLP is a valuable commercial resource. G.A. Sainova., E.M. Sulfur-containing waste from sulfuric acid production of CKZ-U LLP is a valuable commercial resource. G.A. Sainova., E.M. Kozhamberdiev., A.D. Akbasova., U.K. Ibraimov. Almaty: Altyn baspa., 2021. - 216 p.

- https://otyrar. 2013.

- Shelly, T.E.; Kurashima, R.S. Capture of melon flies and Oriental fruit flies (Diptera: Tephritidae) in traps baited with torula yeast-borax or CeraTrap in Hawaii. Fla. Entomol. 2018, 101, 144–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lawson, K.E. , Wu S., Bhattacharjee A.S. Metabolic network analysis reveals microbial community interactions in anammox granules[J]. Nature Communications, 2017, 8.

- Determination of organic matter by the Tyurin method in the modification of TSINAO. 2621.

- Determination of organic matter by the Tyurin method in the Nikitin modification. 6221.

- GОSТ 26483-85 Soil.

- GОSТ 26107-84 Soil.

- Determination of hydrolytic acidity by the Kappen method in the modification of TSINAO. 2621.

- Determination of mobile compounds of phosphorus and potassium by the Kirsanov method in the modification of TSINAO. GОSТ 26207-91.

- GОSТ 8756.13-87 Fruit and vegetable processing products. Methods for the determination of sugars / GОSТ № 8756.13-87.

- GОSТ 26671-2014 Fruit and vegetable processing products, canned meat and meat-growing. Preparation of samples for laboratory analysis.

- GОSТ 26313-2014 Fruit and vegetable processing products. Acceptance rules and sampling methods.

- [Electronic resource]: https://med7. 2050.

- Delmont, T.O. , Robe P., Cecillon S., Clark I.M., Constancias F. Accessing the soil metagenome for studies of microbial diversity // Appl Environ Microbiol. – 2011. – № 77. – P. 1315-1324.

- Oulas, A. , Pavloudi C., Polymenakou P., Pavlopoulos G.A., Papanikolaou N., Kotoulas G. Metagenomics: tools and insights for analyzing next-generation sequencing data derived from biodiversity studies // Bioinform Biol Insights. – 2015. – № 9. – P. 75-88.

- Samofalova, I.A. Chemical composition of soils and soil-forming rocks [Text]: textbook. I.A. Samofalova, M-in s.-x. Russian Federation, FGOU VPO "Perm State Agricultural Academy". - Perm: Publishing House of FGOU VPO "Perm State Agricultural Academy", 2009. - 132 p.

- O. Klimenko., A. O. Klimenko., A. Ivanova., N. Klimenko. Influence of soil alkalinity on the mobility of plant nutrients. Bulletin of the Nikitovsky Botanical Garden. 2007. Issue. 95.

- Hale, Beverley., Evans L., Lambert R. Effects of cement or lime on Cd, Co, Cu, Ni, Pb, Sb and Zn mobility in field-contaminated and aged soils. 2012 Jan 15;199-200:119-27. DOI 10.1016/j.jhazmat.2011.10.

- Zhang, Chang., Yu, Zhi-gang., Zeng, Guang-ming and etc. Effects of sediment geochemical properties on heavy metal bioavailability. DOI 10.1016/j.envint.2014.08.010 Environment International Volume 73, 14, P. 20 December.

- Sokolova, T.A. , Tolpeshta I.I., Trofimov S.Ya. soil acidity. Acid-base buffer capacity of soils. Aluminum compounds in the solid phase of the soil and in the soil solution. Ed. 2nd, rev. and additional - Tula: Grif and K, 2012. - 124 p.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).