Submitted:

07 September 2023

Posted:

07 September 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

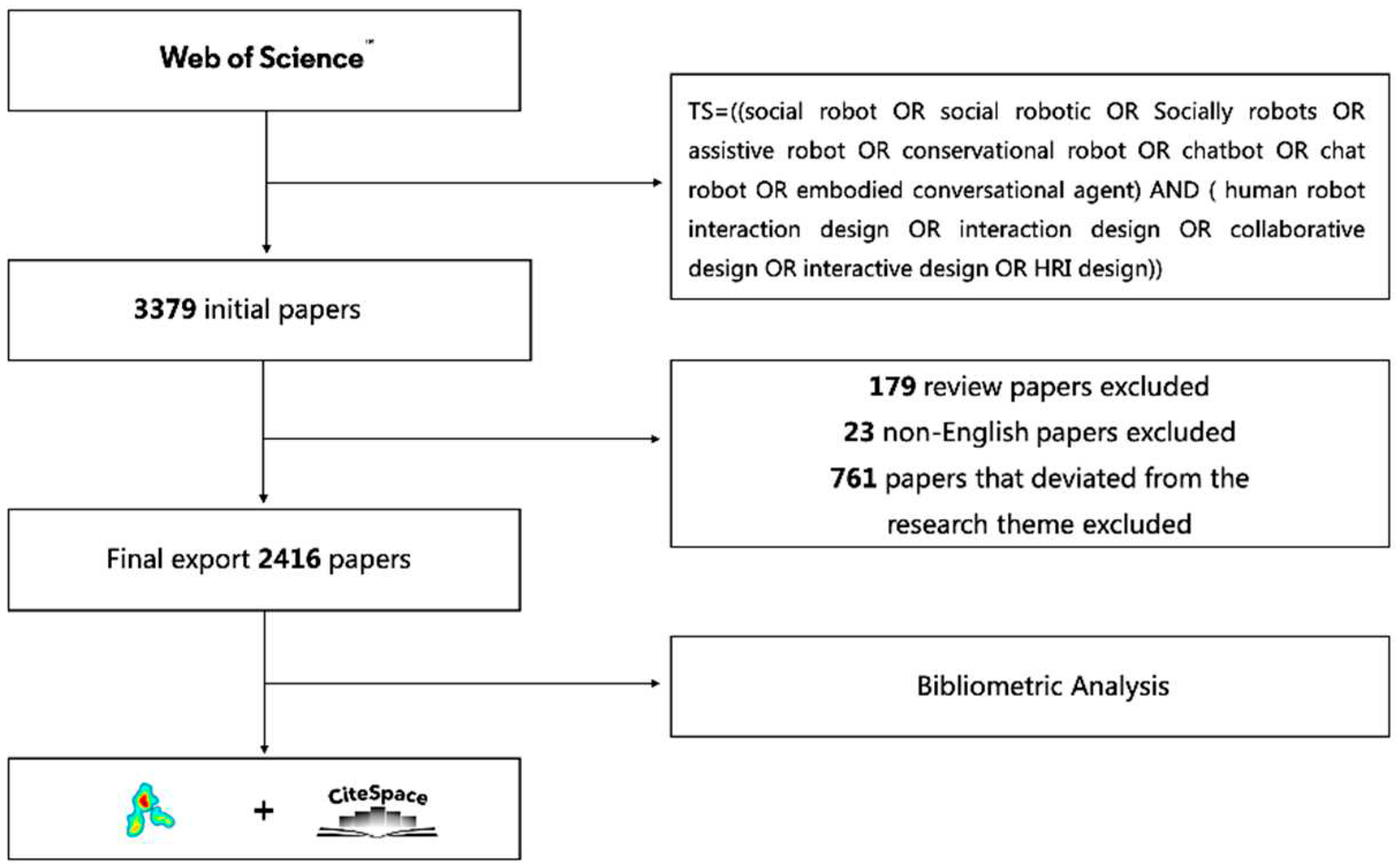

2. Research design

2.1. Data sources

2.2. Research methods

3. Bibliometric Results and Analysis

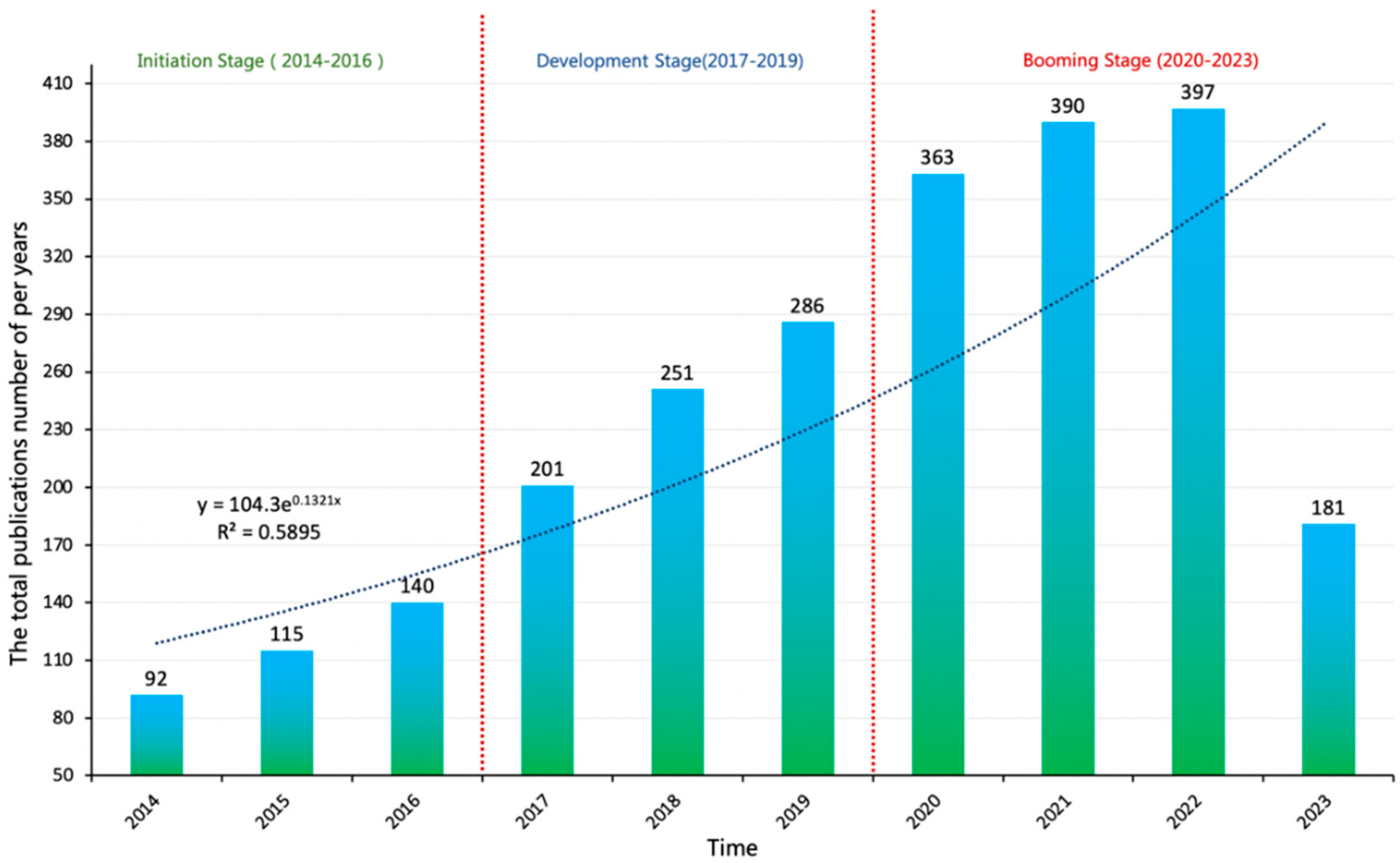

3.1. Trend analysis of annual outputs of SRID literature

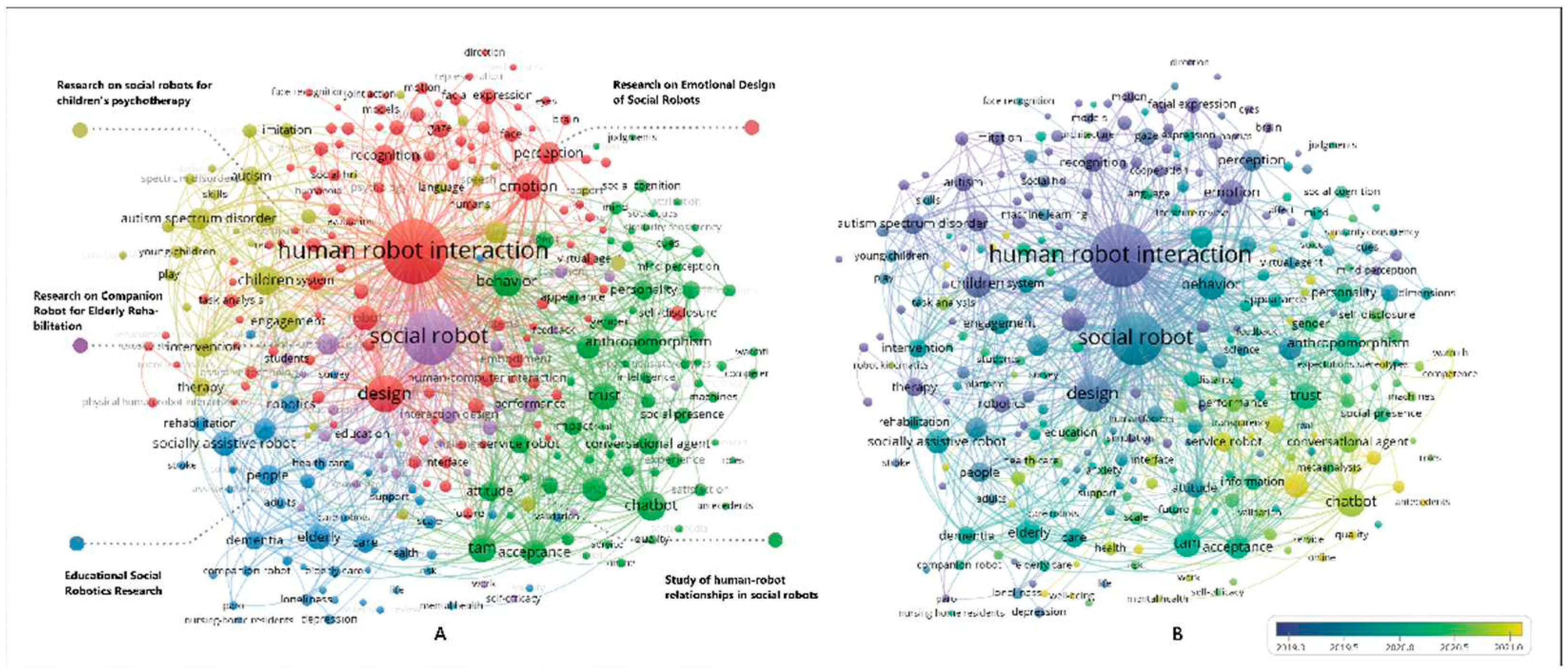

3.2. Research Hotspots of SRID

| Cluster | Cluster label | Average time | Keywords number | Keywords |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1(green) | Study of human-robot relationships in social robots | 2021 | 101 | Acceptance;anthropomorphism;attitude;trust;privacy;self-disclosure ;TAM;warmth;transparency; |

| 2(red) | Research on Emotional Design of Social Robots | 2019 | 60 | Affective computing;affective robotics; emotion;facial expression;body language;eeg; gaze;gesture recognition; |

| 3(yellow) | Research on social robots for children’s psychotherapy | 2019 | 51 | Autism;therapy intervention ;children;anxiety;training ;social skills;spectrum disorder;games;speech |

| 4(biue) | Research on Companion Robot for Elderly Rehabilitation | 2020 | 48 | Elderly;health-care;loneliness;mental health;assisted therapy;co-design;depression;user-centered design |

| 5(purple) | Educational Social Robotics Research | 2020 | 28 | Educational robot;performance;knowledge;teacher;classroom;child-robot interaction; empathy;interaction design |

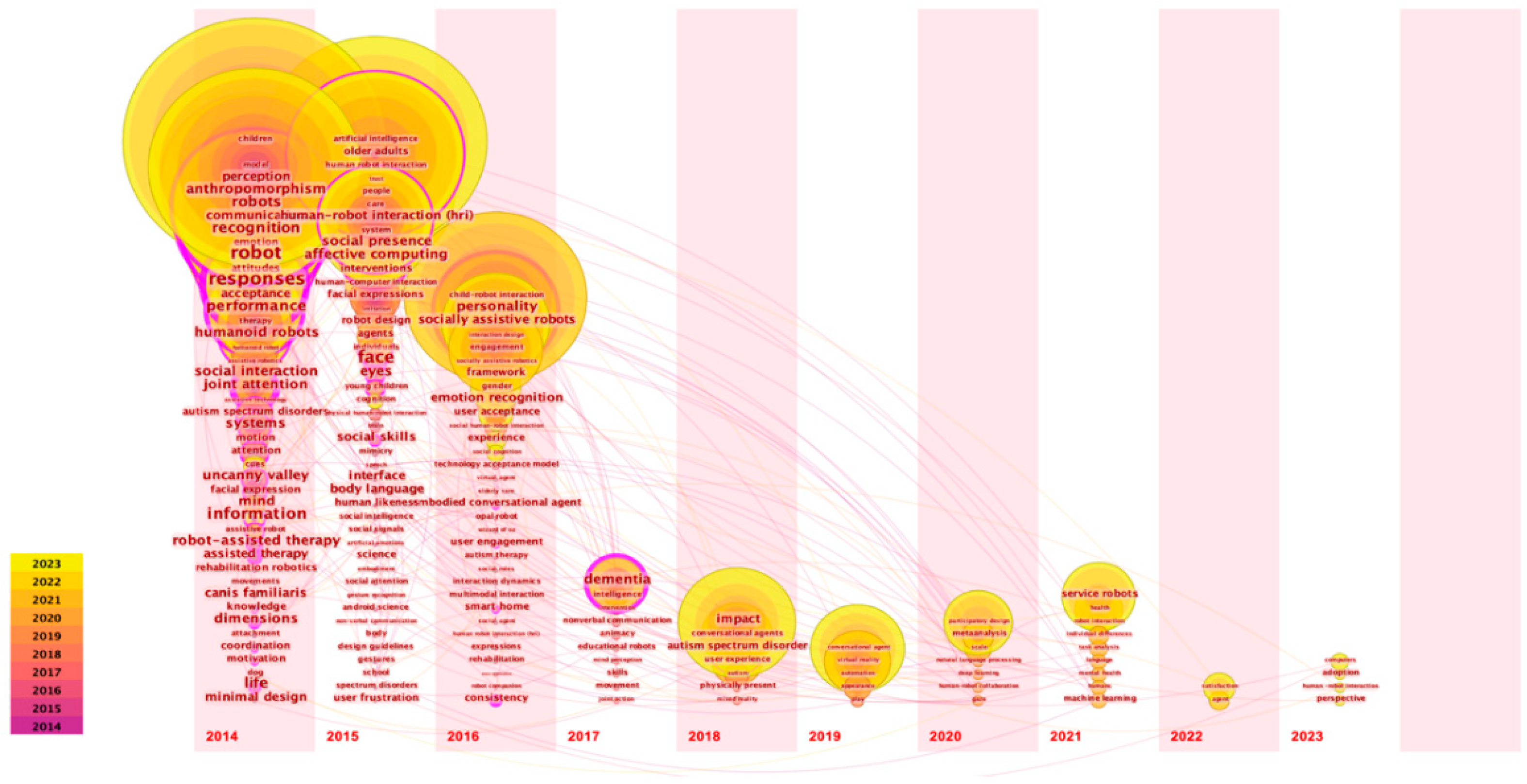

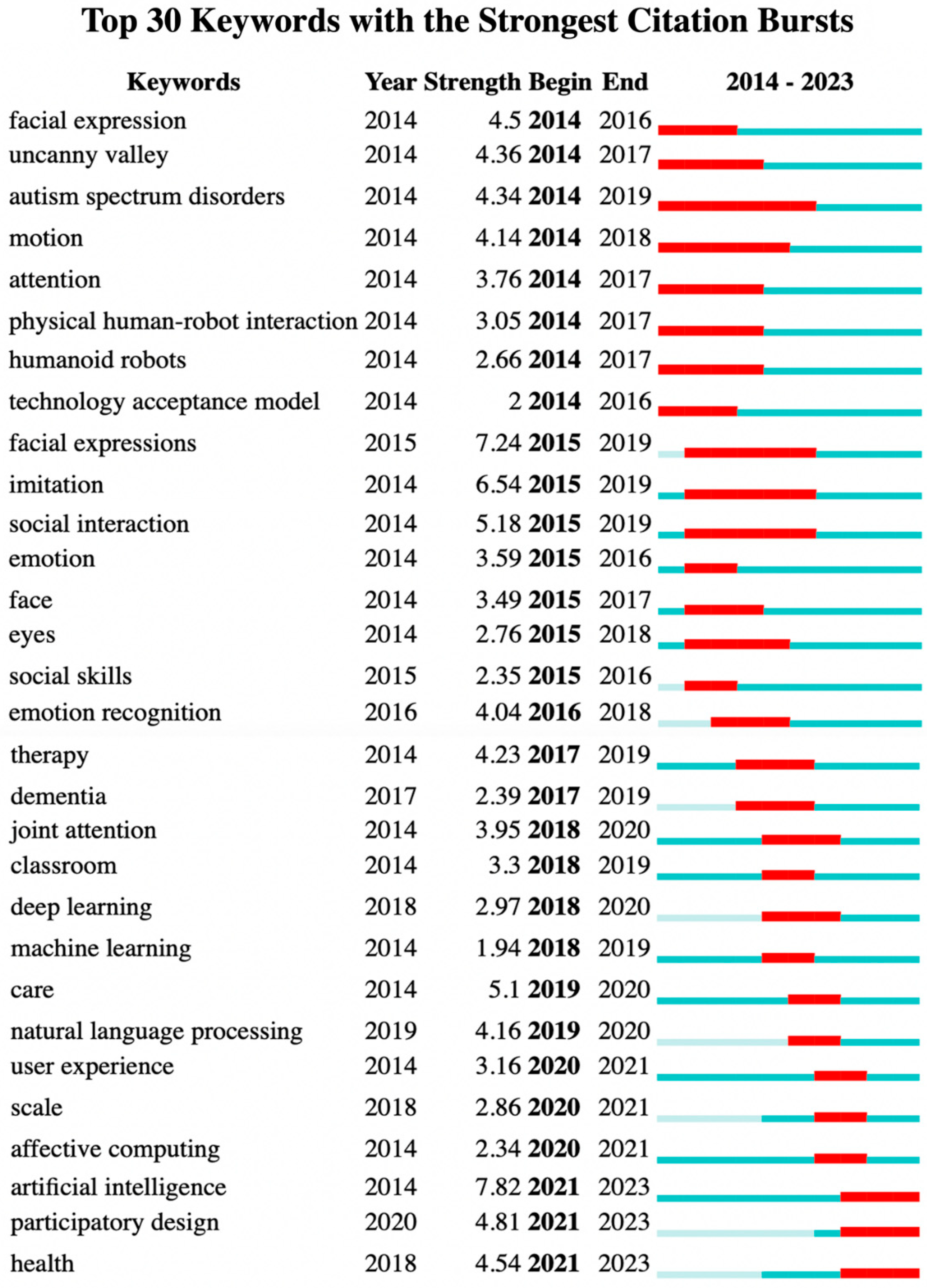

3.3. The evolution and trend of SRID research hotspots

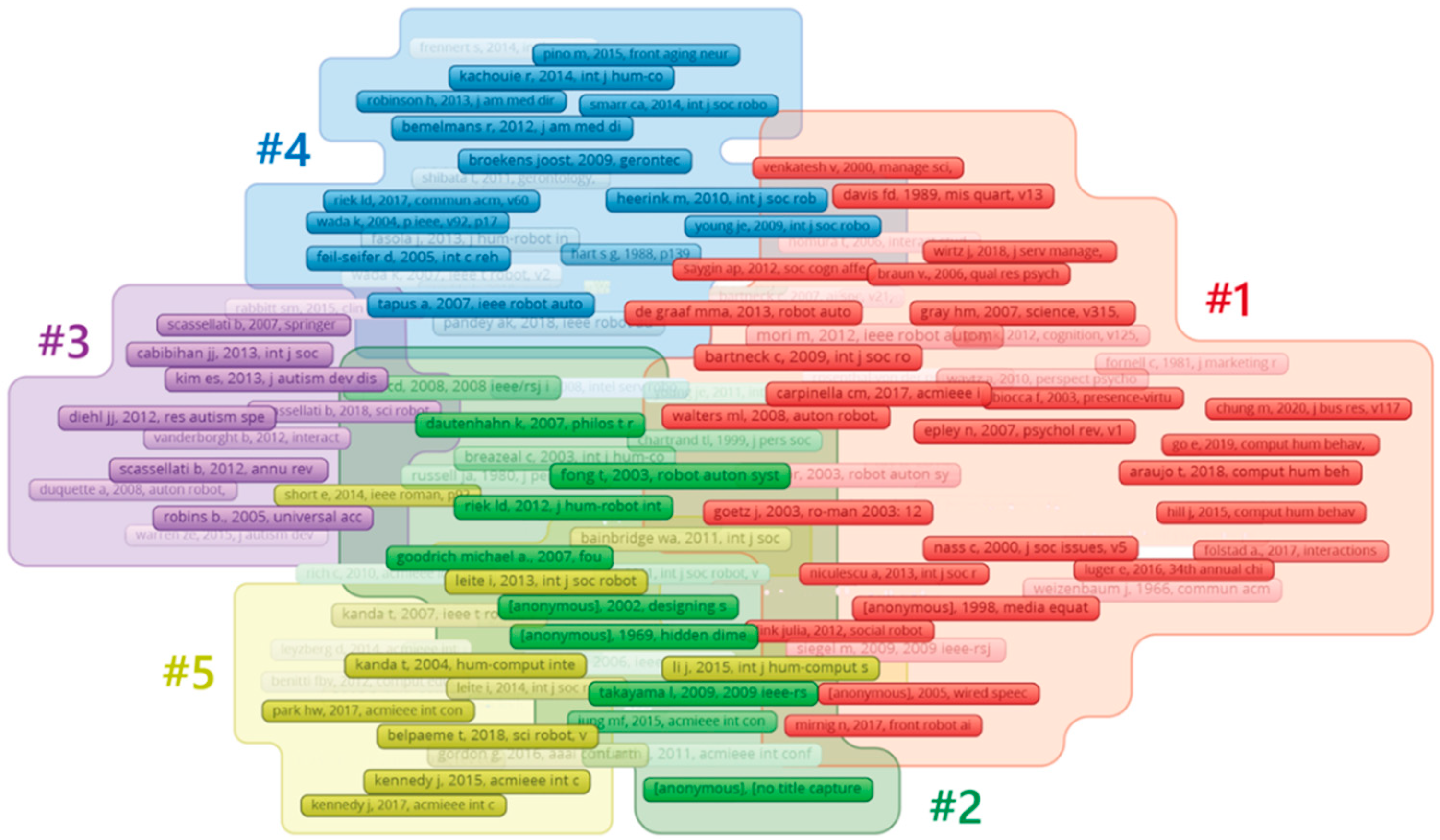

3.4. Knowledge Base of SR-HRI Research

3.5. Distribution of SRID literature sources

| Ranking | Literature source | publisher | number of publications | citations | average number of citations |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | International Journal of Social Robotics | SPRINGER | 4010 | 184 | 21.793 |

| 2 | Computers in Human Behavior | ELSEVIER | 1268 | 39 | 32.512 |

| 3 | Frontiers in Psychology | FRONTIERS | 764 | 34 | 22.470 |

| 4 | International Journal of Human-Computer Studies | ELSEVIER | 734 | 22 | 33.363 |

| 5 | ACM/IEEE International Conference on Human-Robot Interaction(HRI2015) | ACM | 563 | 12 | 46.916 |

| 6 | International Journal of Contemporary Hospitality Management | EMERALD | 544 | 7 | 77.714 |

| 7 | Journal of The American Medical Directors Association | ELSEVIER | 440 | 4 | 110.034 |

| 8 | ACM/IEEE International Conference on Human-Robot Interaction(HRI2018) | ACM | 435 | 13 | 33.461 |

| 9 | Frontiers in Robotics and Ai | FRONTIERS | 388 | 69 | 5.623 |

| 10 | ACM/IEEE International Conference on Human-Robot Interaction(HRI2019) | ACM | 363 | 30 | 12.021 |

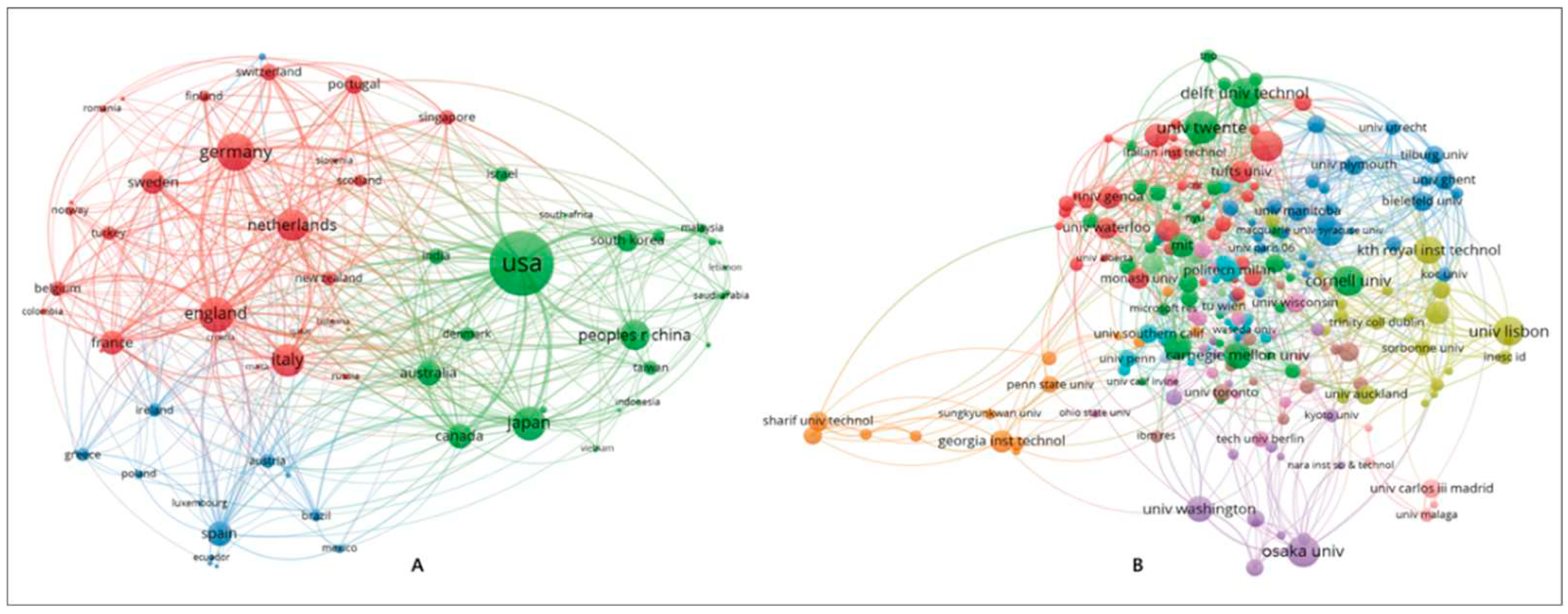

3.6. High-impact countries and research institutions

3.7. High impact author analysis

| Ranking | Author | Institution | Number of published papers | Number of citations | H index |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Paiva, Ana | Polytechnic University of Lisbon | 30 | 476 | 43 |

| 2 | Ishiguro, Hiroshi | Osaka University | 29 | 369 | 54 |

| 3 | Dautenhahn, Kerstin | University of Waterloo | 26 | 599 | 56 |

| 4 | Sabanovic, Selma | Indiana University | 24 | 237 | 32 |

| 5 | Guy Hoffman | Cornell University | 21 | 483 | 33 |

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

6. Limitations and future research

Author Contributions

Funding

Disclosure statement

References

- Eyssel, Friederike, and Dieta Kuchenbrandt. "Social Categorization of Social Robots: Anthropomorphism as a Function of Robot Group Membership." British Journal of Social Psychology 51, no. 4 (2012): 724-31. [CrossRef]

- ou, Xiao, Chih-Fu Wu, Kai-Chieh Lin, Senzhong Gan, and Tzu-Min Tseng. "Effects of Different Types of Social Robot Voices on Affective Evaluations in Different Application Fields." International Journal of Social Robotics 13 (2021): 615-28. [CrossRef]

- Alenljung, Beatrice, Jessica Lindblom, Rebecca Andreasson, and Tom Ziemke. "User Experience in Social Human-Robot Interaction." In Rapid Automation: Concepts, Methodologies, Tools, and Applications, 1468-90: IGI Global, 2019. [CrossRef]

- Van Pinxteren, Michelle ME, Ruud WH Wetzels, Jessica Rüger, Mark Pluymaekers, and Martin Wetzels. "Trust in Humanoid Robots: Implications for Services Marketing." Journal of Services Marketing (2019). [CrossRef]

- Rueben, Matthew, Alexander Mois Aroyo, Christoph Lutz, Johannes Schmölz, Pieter Van Cleynenbreugel, Andrea Corti, Siddharth Agrawal, and William D Smart. "Themes and Research Directions in Privacy-Sensitive Robotics." Paper presented at the 2018 IEEE workshop on advanced robotics and its social impacts (ARSO) 2018.

- Christoforakos, Lara, Alessio Gallucci, Tinatini Surmava-Große, Daniel Ullrich, and Sarah Diefenbach. "Can Robots Earn Our Trust the Same Way Humans Do? A Systematic Exploration of Competence, Warmth, and Anthropomorphism as Determinants of Trust Development in Hri." Frontiers in Robotics and AI 8 (2021): 79.

- Chatterjee, Sheshadri, Soumya Kanti Ghosh, Ranjan Chaudhuri, and Bang Nguyen. "Are Crm Systems Ready for Ai Integration?" The Bottom Line 32, no. 2 (2019): 144-57.

- Atman Uslu, Nilüfer, Gulay Öztüre Yavuz, and Yasemin Koçak Usluel. "A Systematic Review Study on Educational Robotics and Robots." Interactive Learning Environments (2022): 1-25.

- Park, Sungjun S, ChunTing D Tung, and Heejung Lee. "The Adoption of Ai Service Robots: A Comparison between Credence and Experience Service Settings." Psychology & Marketing 38, no. 4 (2021): 691-703. [CrossRef]

- Duffy, Brian R. "Anthropomorphism and the Social Robot." Robotics and Autonomous Systems 42, no. 3-4 (2003): 177-90. [CrossRef]

- Chung, Hanna, Hyunmin Kang, and Soojin Jun. "Verbal Anthropomorphism Design of Social Robots: Investigating Users’ Privacy Perception." Computers in Human Behavior 142 (2023): 107640. [CrossRef]

- Khan, Sara, and Claudio Germak. "Reframing Hri Design Opportunities for Social Robots: Lessons Learnt from a Service Robotics Case Study Approach Using Ux for Hri." Future internet 10, no. 10 (2018): 101. [CrossRef]

- Deutsch, Inbal, Hadas Erel, Michal Paz, Guy Hoffman, and Oren Zuckerman. "Home Robotic Devices for Older Adults: Opportunities and Concerns." Computers in Human Behavior 98 (2019): 122-33. [CrossRef]

- Yang, Daseul, Yu-Jung Chae, Doogon Kim, Yoonseob Lim, Dong Hwan Kim, ChangHwan Kim, Sung-Kee Park, and Changjoo Nam. "Effects of Social Behaviors of Robots in Privacy-Sensitive Situations." International Journal of Social Robotics (2021): 1-14. [CrossRef]

- Babel, Franziska, Johannes Kraus, Linda Miller, Matthias Kraus, Nicolas Wagner, Wolfgang Minker, and Martin Baumann. "Small Talk with a Robot? The Impact of Dialog Content, Talk Initiative, and Gaze Behavior of a Social Robot on Trust, Acceptance, and Proximity." International Journal of Social Robotics (2021): 1-14.

- Yang, Yang, Yue Liu, Xingyang Lv, Jin Ai, and Yifan Li. "Anthropomorphism and Customers’ Willingness to Use Artificial Intelligence Service Agents." Journal of Hospitality Marketing & Management (2021): 1-23. [CrossRef]

- Segijn, Claire M, Joanna Strycharz, Amy Riegelman, and Cody Hennesy. "A Literature Review of Personalization Transparency and Control: Introducing the Transparency–Awareness–Control Framework." Media and Communication 9, no. 4 (2021): 120-33. [CrossRef]

- Fronemann, Nora, Kathrin Pollmann, and Wulf Loh. "Should My Robot Know What’s Best for Me? Human–Robot Interaction between User Experience and Ethical Design." AI & SOCIETY 37, no. 2 (2022): 517-33.

- Giger, Jean-Christophe, Nuno Piçarra, Patrícia Alves-Oliveira, Raquel Oliveira, and Patrícia Arriaga. "Humanization of Robots: Is It Really Such a Good Idea?" Human Behavior and Emerging Technologies 1, no. 2 (2019): 111-23.

- Lin, Hongxia, Oscar Hengxuan Chi, and Dogan Gursoy. "Antecedents of Customers’ Acceptance of Artificially Intelligent Robotic Device Use in Hospitality Services." Journal of Hospitality Marketing & Management 29, no. 5 (2020): 530-49. [CrossRef]

- Tranfield, David, David Denyer, and Palminder Smart. "Towards a Methodology for Developing Evidence-Informed Management Knowledge by Means of Systematic Review." British journal of management 14, no. 3 (2003): 207-22. [CrossRef]

- Al-Emran, Mostafa, Vitaliy Mezhuyev, and Adzhar Kamaludin. "Technology Acceptance Model in M-Learning Context: A Systematic Review." Computers & Education 125 (2018): 389-412. [CrossRef]

- Suru, H Umar, and Pietro Murano. "Security and User Interface Usability of Graphical Authentication Systems–a Review." International Journal of Engineering Trends and Technology (IJERT) 67 (2019): 17-36.

- Gunesekera, Asela Indunil, Yukun Bao, and Mboni Kibelloh. "The Role of Usability on E-Learning User Interactions and Satisfaction: A Literature Review." Journal of Systems and Information Technology (2019). [CrossRef]

- Tan, Hao, Jialing Li, Min He, Jiayu Li, Dan Zhi, Fanzhi Qin, and Chen Zhang. "Global Evolution of Research on Green Energy and Environmental Technologies: A Bibliometric Study." Journal of Environmental Management 297 (2021): 113382. [CrossRef]

- de Wit, Jan, Paul Vogt, and Emiel Krahmer. "The Design and Observed Effects of Robot-Performed Manual Gestures: A Systematic Review." ACM Transactions on Human-Robot Interaction 12, no. 1 (2023): 1-62.

- Robinson, Nicole, Brendan Tidd, Dylan Campbell, Dana Kulić, and Peter Corke. "Robotic Vision for Human-Robot Interaction and Collaboration: A Survey and Systematic Review." ACM Transactions on Human-Robot Interaction 12, no. 1 (2023): 1-66. [CrossRef]

- Mahdi, Hamza, Sami Alperen Akgun, Shahed Saleh, and Kerstin Dautenhahn. "A Survey on the Design and Evolution of Social Robots—Past, Present and Future." Robotics and Autonomous Systems (2022): 104193.

- Loveys, Kate, Gabrielle Sebaratnam, Mark Sagar, and Elizabeth Broadbent. "The Effect of Design Features on Relationship Quality with Embodied Conversational Agents: A Systematic Review." International Journal of Social Robotics 12, no. 6 (2020): 1293-312. [CrossRef]

- Lim, Velvetina, Maki Rooksby, and Emily S Cross. "Social Robots on a Global Stage: Establishing a Role for Culture During Human–Robot Interaction." International Journal of Social Robotics 13, no. 6 (2021): 1307-33. [CrossRef]

- Stock-Homburg, Ruth. "Survey of Emotions in Human–Robot Interactions: Perspectives from Robotic Psychology on 20 Years of Research." International Journal of Social Robotics 14, no. 2 (2022): 389-411. [CrossRef]

- Park, Sung, and Mincheol Whang. "Empathy in Human–Robot Interaction: Designing for Social Robots." International journal of environmental research and public health 19, no. 3 (2022): 1889.

- Song, Yao, and Yan Luximon. "Trust in Ai Agent: A Systematic Review of Facial Anthropomorphic Trustworthiness for Social Robot Design." Sensors 20, no. 18 (2020): 5087. [CrossRef]

- de Jong, Chiara, Jochen Peter, Rinaldo Kühne, and Alex Barco. "Children’s Acceptance of Social Robots: A Narrative Review of the Research 2000–2017." Interaction Studies 20, no. 3 (2019): 393-425.

- Gasteiger, Norina, Kate Loveys, Mikaela Law, and Elizabeth Broadbent. "Friends from the Future: A Scoping Review of Research into Robots and Computer Agents to Combat Loneliness in Older People." Clinical interventions in aging (2021): 941-71. [CrossRef]

- Rasouli, Samira, Garima Gupta, Elizabeth Nilsen, and Kerstin Dautenhahn. "Potential Applications of Social Robots in Robot-Assisted Interventions for Social Anxiety." International Journal of Social Robotics 14, no. 5 (2022): 1-32. [CrossRef]

- Kabacińska, Katarzyna, Tony J Prescott, and Julie M Robillard. "Socially Assistive Robots as Mental Health Interventions for Children: A Scoping Review." International Journal of Social Robotics 13 (2021): 919-35. [CrossRef]

- Abbasi, Nida Itrat, Micol Spitale, Peter B Jones, and Hatice Gunes. "Measuring Mental Wellbeing of Children Via Human-Robot Interaction: Challenges and Opportunities." Interaction Studies 23, no. 2 (2022): 157-203.

- Liu, Li, and Vincent G Duffy. "Exploring the Future Development of Artificial Intelligence (Ai) Applications in Chatbots: A Bibliometric Analysis." International Journal of Social Robotics 15, no. 5 (2023): 703-16. [CrossRef]

- Van Eck, Nees, and Ludo Waltman. "Software Survey: Vosviewer, a Computer Program for Bibliometric Mapping." scientometrics 84, no. 2 (2010): 523-38.

- Chen, Chaomei. "Citespace Ii: Detecting and Visualizing Emerging Trends and Transient Patterns in Scientific Literature." Journal of the American Society for Information Science and Technology 57, no. 3 (2006): 359-77. [CrossRef]

- Rheu, Minjin, Ji Youn Shin, Wei Peng, and Jina Huh-Yoo. "Systematic Review: Trust-Building Factors and Implications for Conversational Agent Design." International Journal of Human–Computer Interaction 37, no. 1 (2021): 81-96. [CrossRef]

- Aghimien, Douglas Omoregie, Clinton Ohis Aigbavboa, Ayodeji Emmanuel Oke, and Wellington Didibhuku Thwala. "Mapping out Research Focus for Robotics and Automation Research in Construction-Related Studies: A Bibliometric Approach." Journal of Engineering, Design and Technology 18, no. 5 (2020): 1063-79.

- Li, Jie, Floris Goerlandt, Genserik Reniers, and Bin Zhang. "Sam Mannan and His Scientific Publications: A Life in Process Safety Research." Journal of Loss Prevention in the Process Industries 66 (2020): 104140. [CrossRef]

- Achuthan, Krishnashree, Vinith Kumar Nair, Robin Kowalski, Sasangan Ramanathan, and Raghu Raman. "Cyberbullying Research—Alignment to Sustainable Development and Impact of Covid-19: Bibliometrics and Science Mapping Analysis." Computers in Human Behavior 140 (2023): 107566. [CrossRef]

- Mongeon, Philippe, and Adèle Paul-Hus. "The Journal Coverage of Web of Science and Scopus: A Comparative Analysis." scientometrics 106 (2016): 213-28. [CrossRef]

- Glanzel, Wolfang. Bibliometrics as a Research Field a Course on Theory and Application of Bibliometric Indicators, 2003.

- Bitkina, Olga Vl, Hyun K Kim, and Jaehyun Park. "Usability and User Experience of Medical Devices: An Overview of the Current State, Analysis Methodologies, and Future Challenges." International Journal of industrial ergonomics 76 (2020): 102932.

- Gobster, Paul H. "(Text) Mining the Landscape: Themes and Trends over 40 Years of Landscape and Urban Planning." 21-30: Elsevier, 2014. [CrossRef]

- Chen Yongkang, Jiang Yuhao, He Ke, and Wu Xingting." Research progress, hotspot and trend analysis of emotional design based on bibliometrics." Packaging Engineering 43, no. 06 (2022): 32-40.

- Tan, Hao, Jiahao Sun, Wang Wenjia, and Chunpeng Zhu. "User Experience & Usability of Driving: A Bibliometric Analysis of 2000-2019." International Journal of Human–Computer Interaction 37, no. 4 (2021): 297-307. [CrossRef]

- Van Eck, Nees Jan, and Ludo Waltman. "Software Survey: Vosviewer, a Computer Program for Bibliometric Mapping." scientometrics 84, no. 2 (2010): 523-38.

- Frey, Brendan J, and Delbert Dueck. "Clustering by Passing Messages between Data Points." science 315, no. 5814 (2007): 972-76. [CrossRef]

- Reeves, Byron, and Clifford Nass. "The Media Equation: How People Treat Computers, Television, and New Media Like Real People." Cambridge, UK 10 (1996): 236605.

- Song, Yao, Da Tao, and Yan Luximon. "In Robot We Trust? The Effect of Emotional Expressions and Contextual Cues on Anthropomorphic Trustworthiness." Applied ergonomics 109 (2023): 103967. [CrossRef]

- Nass, Clifford, and Youngme Moon. "Machines and Mindlessness: Social Responses to Computers." Journal of social Issues 56, no. 1 (2000): 81-103. [CrossRef]

- Kirby, Rachel, Jodi Forlizzi, and Reid Simmons. "Affective Social Robots." Robotics and Autonomous Systems 58, no. 3 (2010): 322-32.

- Foehr, Jonas, and Claas Christian Germelmann. "Alexa, Can I Trust You? Exploring Consumer Paths to Trust in Smart Voice-Interaction Technologies." Journal of the Association for Consumer Research 5, no. 2 (2020): 181-205. [CrossRef]

- Pfeifle, Anne. "Alexa, What Should We Do About Privacy: Protecting Privacy for Users of Voice-Activated Devices." Wash. L. Rev. 93 (2018): 421.

- Benke, Ivo, Ulrich Gnewuch, and Alexander Maedche. "Understanding the Impact of Control Levels over Emotion-Aware Chatbots." Computers in Human Behavior 129 (2022): 107122. [CrossRef]

- Li, Xinge, and Yongjun Sung. "Anthropomorphism Brings Us Closer: The Mediating Role of Psychological Distance in User–Ai Assistant Interactions." Computers in Human Behavior 118 (2021): 106680. [CrossRef]

- Chopdar, Prasanta Kr, and Janarthanan Balakrishnan. "Consumers Response Towards Mobile Commerce Applications: Sor Approach." International Journal of Information Management 53 (2020): 102106. [CrossRef]

- Mende, Martin, Maura L Scott, Jenny van Doorn, Dhruv Grewal, and Ilana Shanks. "Service Robots Rising: How Humanoid Robots Influence Service Experiences and Elicit Compensatory Consumer Responses." Journal of Marketing Research 56, no. 4 (2019): 535-56. [CrossRef]

- Lyons, Joseph B, Kevin T Wynne, Sean Mahoney, and Mark A Roebke. "Trust and Human-Machine Teaming: A Qualitative Study." In Artificial Intelligence for the Internet of Everything, 101-16: Elsevier, 2019.

- Liu, Sunny Xun, Qi Shen, and Jeff Hancock. "Can a Social Robot Be Too Warm or Too Competent? Older Chinese Adults’ Perceptions of Social Robots and Vulnerabilities." Computers in Human Behavior 125 (2021): 106942. [CrossRef]

- Bekey, George A. "Current Trends in Robotics: Technology and Ethics." Robot ethics: The ethical and social implications of robotics (2012): 17-34.

- Gnambs, Timo, and Markus Appel. "Are Robots Becoming Unpopular? Changes in Attitudes Towards Autonomous Robotic Systems in Europe." Computers in Human Behavior 93 (2019): 53-61. [CrossRef]

- Broadbent, Elizabeth, Rie Tamagawa, Anna Patience, Brett Knock, Ngaire Kerse, Karen Day, and Bruce A MacDonald. "Attitudes Towards Health-Care Robots in a Retirement Village." Australasian journal on ageing 31, no. 2 (2012): 115-20. [CrossRef]

- Lee, Kwan Min, Wei Peng, Seung-A Jin, and Chang Yan. "Can Robots Manifest Personality?: An Empirical Test of Personality Recognition, Social Responses, and Social Presence in Human–Robot Interaction." Journal of communication 56, no. 4 (2006): 754-72.

- Lutz, Christoph, Aurelia Tamò, and A Guzman. "Communicating with Robots: Antalyzing the Interaction between Healthcare Robots and Humans with Regards to Privacy." Human-machine communication: rethinking communication, technology, and ourselves (2018): 145-65.

- Breazeal, Cynthia. "Emotion and Sociable Humanoid Robots." International Journal of Human-Computer Studies 59, no. 1-2 (2003): 119-55.

- Dautenhahn, Kerstin. "Socially Intelligent Robots: Dimensions of Human–Robot Interaction." Philosophical transactions of the royal society B: Biological sciences 362, no. 1480 (2007): 679-704.

- Park, Jonghwa, Hanbyul Choi, and Yoonhyuk Jung. "Users’ Cognitive and Affective Response to the Risk to Privacy from a Smart Speaker." International Journal of Human–Computer Interaction 37, no. 8 (2021): 759-71. [CrossRef]

- Kontogiorgos, Dimosthenis, Andre Pereira, Olle Andersson, Marco Koivisto, Elena Gonzalez Rabal, Ville Vartiainen, and Joakim Gustafson. "The Effects of Anthropomorphism and Non-Verbal Social Behaviour in Virtual Assistants." Paper presented at the Proceedings of the 19th ACM International Conference on Intelligent Virtual Agents 2019.

- Davison, Daniel P, Frances M Wijnen, Jan van der Meij, Dennis Reidsma, and Vanessa Evers. "Designing a Social Robot to Support Children’s Inquiry Learning: A Contextual Analysis of Children Working Together at School." International Journal of Social Robotics 12 (2020): 883-907. [CrossRef]

- Provoost, Simon, Ho Ming Lau, Jeroen Ruwaard, and Heleen Riper. "Embodied Conversational Agents in Clinical Psychology: A Scoping Review." Journal of Medical Internet Research 19, no. 5 (2017): e151. [CrossRef]

- Guemghar, Imane, Paula Pires de Oliveira Padilha, Amal Abdel-Baki, Didier Jutras-Aswad, Jesseca Paquette, and Marie-Pascale Pomey. "Social Robot Interventions in Mental Health Care and Their Outcomes, Barriers, and Facilitators: Scoping Review." JMIR mental health 9, no. 4 (2022): e36094.

- Pauw, Lisanne S, Disa A Sauter, Gerben A van Kleef, Gale M Lucas, Jonathan Gratch, and Agneta H Fischer. "The Avatar Will See You Now: Support from a Virtual Human Provides Socio-Emotional Benefits." Computers in Human Behavior 136 (2022): 107368. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Yaoxin, Wenxu Song, Zhenlin Tan, Huilin Zhu, Yuyin Wang, Cheuk Man Lam, Yifang Weng, Sio Pan Hoi, Haoyang Lu, and Bella Siu Man Chan. "Could Social Robots Facilitate Children with Autism Spectrum Disorders in Learning Distrust and Deception?" Computers in Human Behavior 98 (2019): 140-49.

- Schweinberger, Stefan R, Maike Pohl, and Paul Winkler. "Autistic Traits, Personality, and Evaluations of Humanoid Robots by Young and Older Adults." Computers in Human Behavior 106 (2020): 106256. [CrossRef]

- Bendig, Eileen, Benjamin Erb, Lea Schulze-Thuesing, and Harald Baumeister. "The Next Generation: Chatbots in Clinical Psychology and Psychotherapy to Foster Mental Health–a Scoping Review." Verhaltenstherapie (2019): 1-13. [CrossRef]

- David, Daniel, Silviu-Andrei Matu, and Oana Alexandra David. "Robot-Based Psychotherapy: Concepts Development, State of the Art, and New Directions." International Journal of Cognitive Therapy 7, no. 2 (2014): 192-210.

- Riches, Simon, Lisa Azevedo, Alkesh Vora, Ina Kaleva, Lawson Taylor, Peipei Guan, Priyanga Jeyarajaguru, Harley McIntosh, Constantina Petrou, and Sara Pisani. "Therapeutic Engagement in Robot-Assisted Psychological Interventions: A Systematic Review." Clinical Psychology & Psychotherapy 29, no. 3 (2022): 857-73. [CrossRef]

- De’Aira, G Bryant, Jin Xu, Yu-Ping Chen, and Ayanna Howard. "The Effect of Robot Vs. Human Corrective Feedback on Children’s Intrinsic Motivation." Paper presented at the 2019 14th ACM/IEEE International Conference on Human-Robot Interaction (HRI) 2019.

- Zhang, Andong, and Pei-Luen Patrick Rau. "Tools or Peers? Impacts of Anthropomorphism Level and Social Role on Emotional Attachment and Disclosure Tendency Towards Intelligent Agents." Computers in Human Behavior 138 (2023): 107415. [CrossRef]

- Robinson, Nicole L, and David J Kavanagh. "A Social Robot to Deliver a Psychotherapeutic Treatment: Qualitative Responses by Participants in a Randomized Controlled Trial and Future Design Recommendations." International Journal of Human-Computer Studies 155 (2021): 102700. [CrossRef]

- Chattaraman, Veena, Wi-Suk Kwon, Juan E Gilbert, and Kassandra Ross. "Should Ai-Based, Conversational Digital Assistants Employ Social-or Task-Oriented Interaction Style? A Task-Competency and Reciprocity Perspective for Older Adults." Computers in Human Behavior 90 (2019): 315-30. [CrossRef]

- Wu, Ya-Huei, Jérémy Wrobel, Mélanie Cornuet, Hélène Kerhervé, Souad Damnée, and Anne-Sophie Rigaud. "Acceptance of an Assistive Robot in Older Adults: A Mixed-Method Study of Human–Robot Interaction over a 1-Month Period in the Living Lab Setting." Clinical interventions in aging 9 (2014): 801. [CrossRef]

- Morillo-Mendez, Lucas, Martien GS Schrooten, Amy Loutfi, and Oscar Martinez Mozos. "Age-Related Differences in the Perception of Robotic Referential Gaze in Human-Robot Interaction." International Journal of Social Robotics (2022): 1-13. [CrossRef]

- Asgharian, Pouyan, Adina M Panchea, and François Ferland. "A Review on the Use of Mobile Service Robots in Elderly Care." Robotics 11, no. 6 (2022): 127. [CrossRef]

- Sasidharan, Vinod, Laura Payne, Elizabeth Orsega-Smith, and Geoffrey Godbey. "Older Adults’ Physical Activity Participation and Perceptions of Wellbeing: Examining the Role of Social Support for Leisure." Managing Leisure 11, no. 3 (2006): 164-85. [CrossRef]

- Fasola, Juan, and Maja J Mataric. "Using Socially Assistive Human–Robot Interaction to Motivate Physical Exercise for Older Adults." Proceedings of the IEEE 100, no. 8 (2012): 2512-26.

- Li Sijia, Ni Shiguang, Wang Xuqian, and Peng Kaiping." Socially assisted robots: Exploring a new approach to mental health care for the elderly." Chinese Journal of Clinical Psychology, 25, no. 06 (2017): 1191-96.

- Akalin, Neziha, Annica Kristoffersson, and Amy Loutfi. "Do You Feel Safe with Your Robot? Factors Influencing Perceived Safety in Human-Robot Interaction Based on Subjective and Objective Measures." International Journal of Human-Computer Studies 158 (2022): 102744. [CrossRef]

- Chew, Esyin, Umer Sikander Khan, and Pei Hsi Lee. "Designing a Novel Robot Activist Model for Interactive Child Rights Education." International Journal of Social Robotics 13, no. 7 (2021): 1641-55. [CrossRef]

- Reich-Stiebert, Natalia, Friederike Eyssel, and Charlotte Hohnemann. "Exploring University Students’ Preferences for Educational Robot Design by Means of a User-Centered Design Approach." International Journal of Social Robotics 12 (2020): 227-37. [CrossRef]

- Konijn, Elly A, and Johan F Hoorn. "Robot Tutor and Pupils’ Educational Ability: Teaching the Times Tables." Computers & Education 157 (2020): 103970. [CrossRef]

- Kleinberg, Jon. "Bursty and Hierarchical Structure in Streams." Data mining and knowledge discovery 7, no. 4 (2003): 373-97.

- Theodoraki, Christina, Léo-Paul Dana, and Andrea Caputo. "Building Sustainable Entrepreneurial Ecosystems: A Holistic Approach." Journal of Business Research 140 (2022): 346-60. [CrossRef]

- Small, Henry. "Co-Citation in the Scientific Literature: A New Measure of the Relationship between Two Documents." Journal of the American Society for information Science 24, no. 4 (1973): 265-69. [CrossRef]

- Chen, Chaomei, Fidelia Ibekwe-SanJuan, and Jianhua Hou. "The Structure and Dynamics of Cocitation Clusters: A Multiple-Perspective Cocitation Analysis." Journal of the American Society for Information Science and Technology 61, no. 7 (2010): 1386-409. [CrossRef]

- Bartneck, Christoph, Dana Kulić, Elizabeth Croft, and Susana Zoghbi. "Measurement Instruments for the Anthropomorphism, Animacy, Likeability, Perceived Intelligence, and Perceived Safety of Robots." International Journal of Social Robotics 1 (2009): 71-81.

- Riek, Laurel D. "Wizard of Oz Studies in Hri: A Systematic Review and New Reporting Guidelines." Journal of Human-Robot Interaction 1, no. 1 (2012): 119-36. [CrossRef]

- Russell, James A. "A Circumplex Model of Affect." Journal of personality and social psychology 39, no. 6 (1980): 1161.

- Kozima, Hideki, Marek P Michalowski, and Cocoro Nakagawa. "Keepon: A Playful Robot for Research, Therapy, and Entertainment." International Journal of Social Robotics 1 (2009): 3-18.

- Robins, Ben, Kerstin Dautenhahn, R Te Boekhorst, and Aude Billard. "Robotic Assistants in Therapy and Education of Children with Autism: Can a Small Humanoid Robot Help Encourage Social Interaction Skills?" Universal Access in the Information Society 4 (2005): 105-20.

- Kim, Elizabeth S, Lauren D Berkovits, Emily P Bernier, Dan Leyzberg, Frederick Shic, Rhea Paul, and Brian Scassellati. "Social Robots as Embedded Reinforcers of Social Behavior in Children with Autism." Journal of autism and developmental disorders 43 (2013): 1038-49. [CrossRef]

- Heerink, Marcel, Ben Kröse, Vanessa Evers, and Bob Wielinga. "Assessing Acceptance of Assistive Social Agent Technology by Older Adults: The Almere Model." International Journal of Social Robotics 2, no. 4 (2010): 361-75. [CrossRef]

- Wada, Kazuyoshi, and Takanori Shibata. "Living with Seal Robots—Its Sociopsychological and Physiological Influences on the Elderly at a Care House." IEEE transactions on robotics 23, no. 5 (2007): 972-80. [CrossRef]

- Fasola, Juan, and Maja J Matarić. "A Socially Assistive Robot Exercise Coach for the Elderly." Journal of Human-Robot Interaction 2, no. 2 (2013): 3-32. [CrossRef]

- Belpaeme, Tony, James Kennedy, Aditi Ramachandran, Brian Scassellati, and Fumihide Tanaka. "Social Robots for Education: A Review." Science robotics 3, no. 21 (2018): eaat5954. [CrossRef]

- Kanda, Takayuki, Takayuki Hirano, Daniel Eaton, and Hiroshi Ishiguro. "Interactive Robots as Social Partners and Peer Tutors for Children: A Field Trial." Human–Computer Interaction 19, no. 1-2 (2004): 61-84.

- Bartneck, Christoph, and Jodi Forlizzi. "A Design-Centred Framework for Social Human-Robot Interaction." Paper presented at the RO-MAN 2004. 13th IEEE international workshop on robot and human interactive communication (IEEE Catalog No. 04TH8759) 2004.

- Schmidt, Frank L, and John E Hunter. "Measurement Error in Psychological Research: Lessons from 26 Research Scenarios." Psychological methods 1, no. 2 (1996): 199.

- Smeds, Karolina, Florian Wolters, and Martin Rung. "Estimation of Signal-to-Noise Ratios in Realistic Sound Scenarios." Journal of the American Academy of Audiology 26, no. 02 (2015): 183-96. [CrossRef]

- Hancock, Peter A, Theresa T Kessler, Alexandra D Kaplan, John C Brill, and James L Szalma. "Evolving Trust in Robots: Specification through Sequential and Comparative Meta-Analyses." Human factors 63, no. 7 (2021): 1196-229. [CrossRef]

- Lemaignan, Séverin, Charlotte ER Edmunds, Emmanuel Senft, and Tony Belpaeme. "The Pinsoro Dataset: Supporting the Data-Driven Study of Child-Child and Child-Robot Social Dynamics." PloS one 13, no. 10 (2018): e0205999. [CrossRef]

- McCartney, Neil, Audrey L Hicks, Joan Martin, and Colin E Webber. "A Longitudinal Trial of Weight Training in the Elderly: Continued Improvements in Year 2." The Journals of Gerontology Series A: Biological Sciences and Medical Sciences 51, no. 6 (1996): B425-B33. [CrossRef]

- Pickut, Barbara A, Wim Van Hecke, Eric Kerckhofs, Peter Mariën, Sven Vanneste, Patrick Cras, and Paul M Parizel. "Mindfulness Based Intervention in Parkinson’s Disease Leads to Structural Brain Changes on Mri: A Randomized Controlled Longitudinal Trial." Clinical neurology and neurosurgery 115, no. 12 (2013): 2419-25.

- van Straten, Caroline L, Jochen Peter, Rinaldo Kühne, and Alex Barco. "On Sharing and Caring: Investigating the Effects of a Robot’s Self-Disclosure and Question-Asking on Children’s Robot Perceptions and Child-Robot Relationship Formation." Computers in Human Behavior 129 (2022): 107135.

- Holohan, Michael, and Amelia Fiske. "“Like I’m Talking to a Real Person”: Exploring the Meaning of Transference for the Use and Design of Ai-Based Applications in Psychotherapy." Frontiers in Psychology 12 (2021): 720476.

- Naneva, Stanislava, Marina Sarda Gou, Thomas L Webb, and Tony J Prescott. "A Systematic Review of Attitudes, Anxiety, Acceptance, and Trust Towards Social Robots." International Journal of Social Robotics 12, no. 6 (2020): 1179-201.

- Mehrabian, Albert, and James A Russell. An Approach to Environmental Psychology: the MIT Press, 1974.

- Arora, Raj. "Validation of an Sor Model for Situation, Enduring, and Response Components of Involvement." Journal of Marketing Research 19, no. 4 (1982): 505-16.

- Cho, Woo-Chul, Kyung Young Lee, and Sung-Byung Yang. "What Makes You Feel Attached to Smartwatches? The Stimulus–Organism–Response (S–O–R) Perspectives." Information Technology & People 32, no. 2 (2019): 319-43.

- Kumari, Pooja. "How Does Interactivity Impact User Engagement over Mobile Bookkeeping Applications?" Journal of Global Information Management (JGIM) 30, no. 5 (2021): 1-16.

- Lutz, Christoph, and Aurelia Tamó-Larrieux. "The Robot Privacy Paradox: Understanding How Privacy Concerns Shape Intentions to Use Social Robots." Human-Machine Communication 1 (2020): 87-111. [CrossRef]

- Wang, Zilong, and Jian Wang. "Do the Emotions Evoked by Interface Design Factors Affect the User’s Intention to Continue Using the Smartwatch? The Mediating Role of Quality Perceptions." International Journal of Human–Computer Interaction 39, no. 3 (2023): 546-61. [CrossRef]

- Saydam, Mehmet Bahri, Hasan Evrim Arici, and Mehmet Ali Koseoglu. "How Does the Tourism and Hospitality Industry Use Artificial Intelligence? A Review of Empirical Studies and Future Research Agenda." Journal of Hospitality Marketing & Management 31, no. 8 (2022): 908-36. [CrossRef]

- Sabe, Michel, Toby Pillinger, Stefan Kaiser, Chaomei Chen, Heidi Taipale, Antti Tanskanen, Jari Tiihonen, Stefan Leucht, Christoph U Correll, and Marco Solmi. "Half a Century of Research on Antipsychotics and Schizophrenia: A Scientometric Study of Hotspots, Nodes, Bursts, and Trends." Neuroscience & Biobehavioral Reviews 136 (2022): 104608.

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).