1. Introduction

Macrophages play a pivotal role in the process of wound and burn healing [

1,

2,

3,

4]. In both types of healing the M1 macrophages first debride the injured skin of apoptotic and dead cells and of intercellular cell matrix. Subsequently, M2 macrophages orchestrate the regeneration of the epidermis, dermis and hypodermis of the injured skin [

2,

3,

4,

5,

6]. This is mediated by a wide range of cytokines/growth factors secreted by these macrophages, including vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) mediating neo-vascularization, epidermal growth factor (EGF) inducing epidermal re-growth, fibroblasts growth factor (FGF) recruiting fibroblasts, and factors recruiting mesenchymal stem cells (MSC) which contribute to the regeneration of the injured skin [

7]. In wounds, incisions, and contusions, the macrophages mediating healing comprise of both residential macrophages and monocytes derived macrophages that are recruited by chemotactic factors such as macrophage inflammatory protein-1 (MIP-1), monocyte chemoattractant protein-1 (MCP-1) and

regulated on activation, normal T cell expressed and secreted factor (RANTES) secreted by cells surrounding the wound [

8,

9,

10,

11]. However, since in epidermis penetrating burns (burn degrees 2-4) the residential macrophages are inactivated or killed [

1] and since the surface area size of the burns are in many cases larger than that of wounds, infiltration of macrophages into burns and healing of burns may take longer time than in wounds and regeneration of epidermis in many burns may be slower than in wounds. This slow re-epithelialization is a major risk factor because of microbial infections that occur in the absence of intact epidermis. Such infections may result in high morbidity and mortality following severe burn injuries [

6,

12,

13,

14].

Based on the pivotal role of macrophages in healing of burns, and in view of the immune suppression of macrophages following burn injury [

15,

16], it has been suggested that the risk factors due to slow re-epithelialization might be reduced by accelerating the regrowth of the epidermis over the burned tissue [

3,

4,

7,

15,

16,

17,

18]. Several methods of various degrees of difficulty have been studied for accelerating burn healing. These include topical application to burns of autologous MSC [

19,

20], autologous cultured epidermal cell grafts [

21,

22],

recombinant human granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor (GM-CSF) [

23,

24]

, high-density lipoprotein nanoparticles [

25], bioactive molecules delivered in microfibers [

26,

27] and the use of negative pressure wound therapy[

28].

The present review offers an alternative method to those mentioned above, for accelerated healing of burns by inducing rapid recruitment and activation of macrophages in treated burns, by topical application of a-gal nanoparticles. This method recapitulates the physiologic healing processes of burns, but the accelerated recruitment of macrophages into treated burns cuts the healing time by half. The interaction of these nanoparticles with the natural anti-Gal antibody (one of the most abundant natural antibodies in humans) within burns results in rapid and extensive recruitment of monocytes derived macrophages into burns. Many of these macrophages polarize into M2 macrophages which orchestrate accelerated healing of burns by localized secretion of angiogenic factors such as VEGF and growth factors recruiting MSC. This review describes studies that characterized the anti-Gal antibody and a-gal nanoparticles, the simple production of these nanoparticles from mammalian red blood cells and the great efficacy of the burn and wound therapies with a-gal nanoparticles, as observed in the anti-Gal producing mouse experimental model.

2. Anti-Gal and the a-gal Epitope

The method described in this review for accelerating burn healing harnesses the immunologic potential of the natural anti-Gal antibody which is one of the most abundant natural antibodies in humans, constituting 1% of serum immunoglobulins [

29]. The immune system in humans produces anti-Gal throughout life in response to antigenic stimulation by some carbohydrate antigens presented on gastrointestinal bacteria [

30,

31]. The mammalian antigen recognized by the anti-Gal is the a-gal epitope (Gala1- 3Galb1-4GlcNAc-R) [

32,

33,

34]. The a-gal epitope is abundantly expressed on glycolipids and glycoproteins of nonprimate mammals, lemurs, and New-World monkeys (monkeys of South America), therefore, these mammals cannot produce anti-Gal [

35,

36,

37]. In contrast, humans, apes, and Old-World monkeys (monkeys of Asia and Africa) all lack a-gal epitopes but produce the natural anti-Gal antibody [

35,

36,

37,

38]. Incubation of cells presenting a-gal epitope in human serum results in effective activation of the complement cascade in the serum, because of the binding of serum anti-Gal to these a-gal epitopes. The efficacy of this complement activation was demonstrated in xenotransplantation studies. Interaction between anti-Gal and a-gal epitopes on endothelial cells of pig xenografts was found to result in the activation of the complement system, causing cytolysis of these cells, collapse of the vascular bed and rapid (hyperacute) rejection of such xenografts in monkeys or humans [

39,

40,

41,

42]. Similarly, incubation of enveloped viruses presenting a-gal epitopes in human serum was found to result in binding of anti-Gal to these epitopes and in activation of the complement system which leads to complement mediated destruction of such viruses [

43,

44,

45,

46]. Since the very potent macrophage directing chemotactic factors C5a and C3a are produced as complement cleavage peptide byproducts during complement activation, we assumed that binding of serum anti-Gal to multiple a-gal epitopes on a-gal nanoparticles applied to burns and wounds may result in extensive recruitment of monocyte derived macrophages to treated skin injury sites.

3. Hypothesis

The effective complement activation by anti-Gal binding to a-gal epitopes led us to hypothesize that topical application of nanoparticles presenting multiple a-gal epitopes (called a-gal nanoparticles and previously called a-gal liposomes) during the early stages of hemostasis in burns, results in binding of the natural anti-Gal antibody to these nanoparticles [

17,

47]. Anti-Gal is present in the fluid film on the surface of burns together with the complement system proteins, as well as with other serum proteins which leak from injured capillaries. As detailed below, a-gal nanoparticles are small size liposomes (~200-300 nm) constructed of a-gal presenting glycolipids that are anchored in the nanoparticles wall that is comprised of phospholipids and cholesterol (

Figure 1A).

The binding of anti-Gal to the multiple a-gal epitopes on the nanoparticles results in activation of the complement cascade and thus in generation of chemotactic complement cleavage peptides C5a and C3a (Step 1 in

Figure 1B). These chemotactic factors induce extensive migration of neutrophils and monocytes derived macrophages into the burn area (Step 2 in

Figure 1B). In addition, it was further hypothesized that whereas the neutrophils survive only for few hours in the burn, the recruited macrophages are long-lived, and they bind the a-gal nanoparticles as a result of interaction between the Fcg “tail” of anti-Gal bound to the nanoparticles and Fcg receptors (FcgR) on the macrophages (Step 3 in

Figure 1B). It was further hypothesized that the multiple Fcg/FcgR interactions between anti-Gal coated a-gal nanoparticles and macrophages may activate the recruited macrophages to secrete various cytokines/growth factors that mediate accelerated migration of fibroblasts and MSC into the treated burn, as well as neo-vascularization of the healing burn (Step 4 in

Figure 1B), and rapid re-epithelialization. Ultimately, these multiple cytokines/growth factors secreted by the recruited and activated macrophages may accelerated healing of the a-gal nanoparticles treated burns in comparison to non-treated burns.

4. Preparation of a-gal Nanoparticles

A relatively simple way for preparing a-gal nanoparticles is by extraction of their components from the membranes (ghosts) of rabbit red blood cells (RBC) in a mixture of chloroform and methanol [

17]. The reason for using these RBC is that they present as many as 2x10

6 a-gal epitopes per RBC, an amount that is several folds higher than any other mammalian RBC studied [

35]. After the rabbit RBC are lysed in water and their membranes are washed for the removal of hemoglobin, the RBC membranes are incubated overnight in a solution of chloroform:methanol 1:2 with constant stirring, resulting in the extraction of phospholipids, glycolipids and cholesterol from these membranes, whereas all proteins are denatured and removed from the solution by filtration. The solution containing the extracted molecules is dried and the mixture of phospholipids, glycolipids and cholesterol is resuspended in saline by extensive sonication. This sonication results in formation of a suspension of submicroscopic liposomes (~100-300 nm) with walls comprised of phospholipid and cholesterol and studded with multiple a-gal epitopes in the form of anchored a-gal glycolipids (

Figure 1A). These submicroscopic liposomes originally called a-gal liposomes [

17,

48] have been subsequently referred to as a-gal nanoparticles [

18,

47] to indicate that they do not contain any substance in their lumen.

The a-gal nanoparticles were found to present ~10

14 a-gal epitopes/mg nanoparticles [

18]. Processed 500 ml packed rabbit RBC were found to yield ~6 grams of a-gal nanoparticles. Because of their small size, a-gal nanoparticles suspensions can be sterilized by filtration through a 0.4 mm filter. It is of note that a-gal nanoparticles may be prepared also from synthetic a-gal glycolipids, phospholipids and cholesterol by similar mixing and sonication processes. The a-gal nanoparticles are highly stable and can be kept as frozen suspensions for >10 years, at 4

oC for >2 years and as dried nanoparticles on wound dressings kept at room temp. for >1 year (unpublished observations). Stability of the stored a-gal nanoparticles could be confirmed by their ability to bind anti-Gal in amounts like those measured immediately after production. Topical application of a-gal nanoparticles to burns and wounds can be performed by various methods including the use of nanoparticles suspensions in saline or PBS, nanoparticles dried on wound dressings, aerosol suspensions and suspensions in hydrogels.

5. Experimental Animal Models

Studies of anti-Gal associated therapies cannot be performed in standard animal experimental models such as mice, rats, rabbits, pigs or guinea pigs because these animals, like other non-primate mammals, synthesize a-gal epitopes [

35,

36]. Therefore, such mammals are immunotolerant to the a-gal epitope and cannot produce the anti-Gal antibody [

35]. However, the two experimental non-primate mammalian models available for studying anti-Gal associated therapies have been mice [

49,

50] and pigs [

51,

52] in which the

GGTA1 gene coding for the glycosyltransferase synthesizing a-gal epitope “a1,3galactosyltransferase”, was disrupted (i.e., knocked out). These a1,3galactosyltransferase knockout (GT-KO) mice [

17,

18] and pigs [

53,

54,

55] lack the ability to synthesize a-gal epitopes and thus, can produce the anti-Gal antibody. Whereas GT-KO pigs produce the natural anti-Gal antibody, as humans do, GT-KO mice do not naturally produce this antibody since they do not develop gastrointestinal bacterial flora that may immunize them, because they are kept in a sterile environment and receive sterile food. Nevertheless, GT-KO mice readily produce the anti-Gal antibody following several immunizations with xenogeneic cells or tissues presenting a-gal epitopes, such as pig kidney membranes (PKM) homogenate [

56].

6. In vitro Effects of a-gal Nanoparticles on Macrophages

Some of the steps of anti-Gal/a-gal nanoparticles interaction, described in the hypothesis illustrated in

Figure 1B, could be demonstrated

in vitro in studies described in

Figure 2. Step 1 of anti-Gal binding to a-gal epitopes on a-gal nanoparticles was demonstrated by the specific binding of monoclonal anti-Gal antibody to these nanoparticles (

Figure 2A). A similar binding was observed with serum anti-Gal from anti-Gal producing GT-KO mice that interacts woth a-gal nanoparticles (

Figure 2B). In the absence of a-gal epitopes on the nanoparticles, no binding of the monoclonal anti-Gal antibody was observed [

17].

Step 3 in the hypothesis in

Figure 1B predicts binding of anti-Gal coated α-gal nanoparticles to macrophages via Fcg/FcgR interaction. This binding is demonstrated by scanning electron microscopy (SEM) in

Figure 2C,D. Macrphages lacking a-gal epitopes were generated

in vitro by culturing of monocytes obtained from blood of GT-KO pigs. These macrophages were co-incubated for 2 hours at room temp. with anti-Gal-coated α-gal nanoparticles. Such incubation resulted in extensive binding of α-gal nanoparticles to the macrophages, shown as the multiple small spheres (size of 100–300nm) covering the surface of the two macrophages (

Figure 2C,D). In the absence of anti-Gal on the α-gal nanoparticles, no binding of these nanoparticles to macrophages was observed [

47]. Step 4 in the hypothesis in

Figure 1B predicted that the binding of anti-Gal coated a-gal nanoparticles to recruited macrophages via Fcγ/FcγR interaction may generate signals that activate a variety of cytokines/growth factors producing genes that orchestrate accelerated healing of a-gal nanoparticles treated burns. Possible activation of macrophages by anti-Gal coated a-gal nanoparticles was studied with GT-KO mouse macrophages incubated for 24-48 hours at 37°C, alone or with α-gal nanoparticles coated with anti-Gal or lacking the antibody. The secretion of VEGF by the macrophages was measured in the tissue culture medium after 24 and 48 hours of co-incubation. Macrophages co-incubated with α-gal nanoparticles lacking anti-Gal, secreted only background level of VEGF, as determined by ELISA measuring this cytokine (

Figure 2E). However, co-incubation of the macrophages with anti-Gal-coated α-gal nanoparticles for 24 and 48 hours resulted in elevated secretion of VEGF by the activated macrophages, at levels that were significantly higher than the background levels (

Figure 2E) [

48]. These findings indicated that anti-Gal mediated binding of a-gal nanoparticles to cultured macrophages indeed induces these macrophages to secrete VEGF.

7. In vivo Effects of a-gal Nanoparticles on Macrophages

A crucial step in the hypothesis in

Figure 1B is Step 2 which predicts that anti-Gal binding to a-gal nanoparticles applied to burns activates the complement system, resulting in the formation of complement cleavage chemotactic peptides C5a and C3a. These peptides direct a rapid and extensive recruitment of monocytes derived macrophages to the treated burn. The occurrence of Step 2 was studied by intradermal injection of 10 mg a-gal nanoparticles in anti-Gal producing GT-KO mice (i.e., GT-KO mice immunized with PKM) and microscopic evaluation of macrophages in the injection site at various time points. The first effect of such injection was the accumulation of many neutrophils, observed at the injection site within 12 hours post injection [

48]. These neutrophils are also chemotactically recruited by C5a and C3a generated by anti-Gal/a-gal nanoparticles interaction. However, after 24 hours, most neutrophils disappeared, and multiple mononuclear cells were observed migrating to the injection site (

Figure 3A). The number of macrophages increased after 4 days and as expected, they all were immunostained by the macrophage specific antibody F4/80 (

Figure 3B). Quantitative real time PCR (qRT-PCR) of skin specimen containing the recruited macrophages displayed activation of genes encoding for fibroblast growth factor (FGF), interleukin 1 (IL1), platelet derived growth factor (PDGF), and colony stimulating factor (CSF) [

48].

The number of recruited macrophages further increased by Day 7 (

Figure 3C). These macrophages had large size and ample cytoplasm, characteristic of activated macrophages (

Figure 3C,D) [

48]. Large numbers of recruited macrophages were observed at the injection site, even on Day 14. However, by Day 21 post injection of the a-gal nanoparticles, all macrophages disappeared from the injection site and the skin in that area displayed normal structure with no granuloma, chronic inflammatory response, or keloid formation [

48]. Intradermal injection of a-gal nanoparticles together with cobra venom factor (a complement activation inhibitor), with saline, or with nanoparticles lacking a-gal epitopes (i.e., nanoparticles produced from GT-KO pig RBC) all resulted in no significant recruitment of macrophages to the injection site [

48]. Similarly, intradermal injection of a-gal nanoparticles into wild-type (WT) mice (i.e., mice lacking the anti-Gal antibody) resulted in no macrophage recruitment. These observations clearly demonstrated the ability of a-gal nanoparticles to induce extensive and rapid recruitment of macrophages by binding of the anti-Gal antibody and activation of the complement system which generates the potent chemotactic complement cleavage chemotactic peptides C5a and C3a.

8. Macrophages Recruited by a-gal Nanoparticles are M2 Further Recruiting MSC

Analysis of the characteristics of macrophages recruited by a-gal nanoparticles in anti-Gal producing GT-KO mice could be further performed by subcutaneous implantation of biologically inert sponge discs (made of polyvinyl alcohol- PVA, 10 mm diameter, 3 mm thickness) that contained 10 mg α-gal nanoparticles. The PVA sponge discs were explanted on Day 6 or Day 9. The cells harvested from these sponge discs had the morphology of large macrophages as those presented in

Figure 3D. Each of the PVA sponge discs contained at those time points ~0.4x10

6 and ~0.6x10

6 infiltrating cells, respectively, whereas sponge discs with only saline contained ~0.02x10

6 and ~0.04x10

6 cells, respectively [

17]. Immunostaining and flow cytometry analysis of the cells recruited by a-gal nanoparticles indicated that most of them (>90%) expressed the macrophage markers CD11b and CD14 (

Figure 4A). In contrast, no significant proportion of the infiltrating cells displayed surface markers of CD4+ T cells, CD8+ T cells, or of B cells (i.e., lymphocytes presenting CD20+ cell marker) [

17].

Further analysis of the polarization state of macrophages recruited by a-gal nanoparticles indicated that they were M2 macrophages since they were positively immunostained for M2 markers IL-10 and Arginase-1 and were negatively immunostained for IL-12, a marker which characterizes M1 macrophages (

Figure 4B) [

57]. When these infiltrating macrophages were cultured

in vitro for 5 days, the culture wells were found to contain cell colonies at a frequency of one colony per 50,000 to 100,000 cultured macrophages. These cell colonies had the morphological characteristics of colonies formed by MSC (

Figure 4C,D). Accordingly, the majority of the cells retrieved from these colonies presented the stem cell markers Sca-1 and CD-29 (

Figure 4E,F). These colonies contained 300-1000 cells per colony, suggesting that the cells forming them proliferated at an average cell-cycle time of ~12 hours. Overall, the observations in

Figure 4B–F suggest that the majority of macrophages recruited and activated by a-gal nanoparticles polarized into M2 macrophages and further directed migration of MSC into the implanted PVA sponge discs [

58].

9. Accelerated Healing of Burns by Topical Application of a-gal Nanoparticles

The above

in vitro and

in vivo studies on the effects of a-gal nanoparticles on macrophages (

Figure 3 and

Figure 4, respectively) prompted the analysis of effects of these nanoparticles on burns healing in anti-Gal producing GT-KO mice [

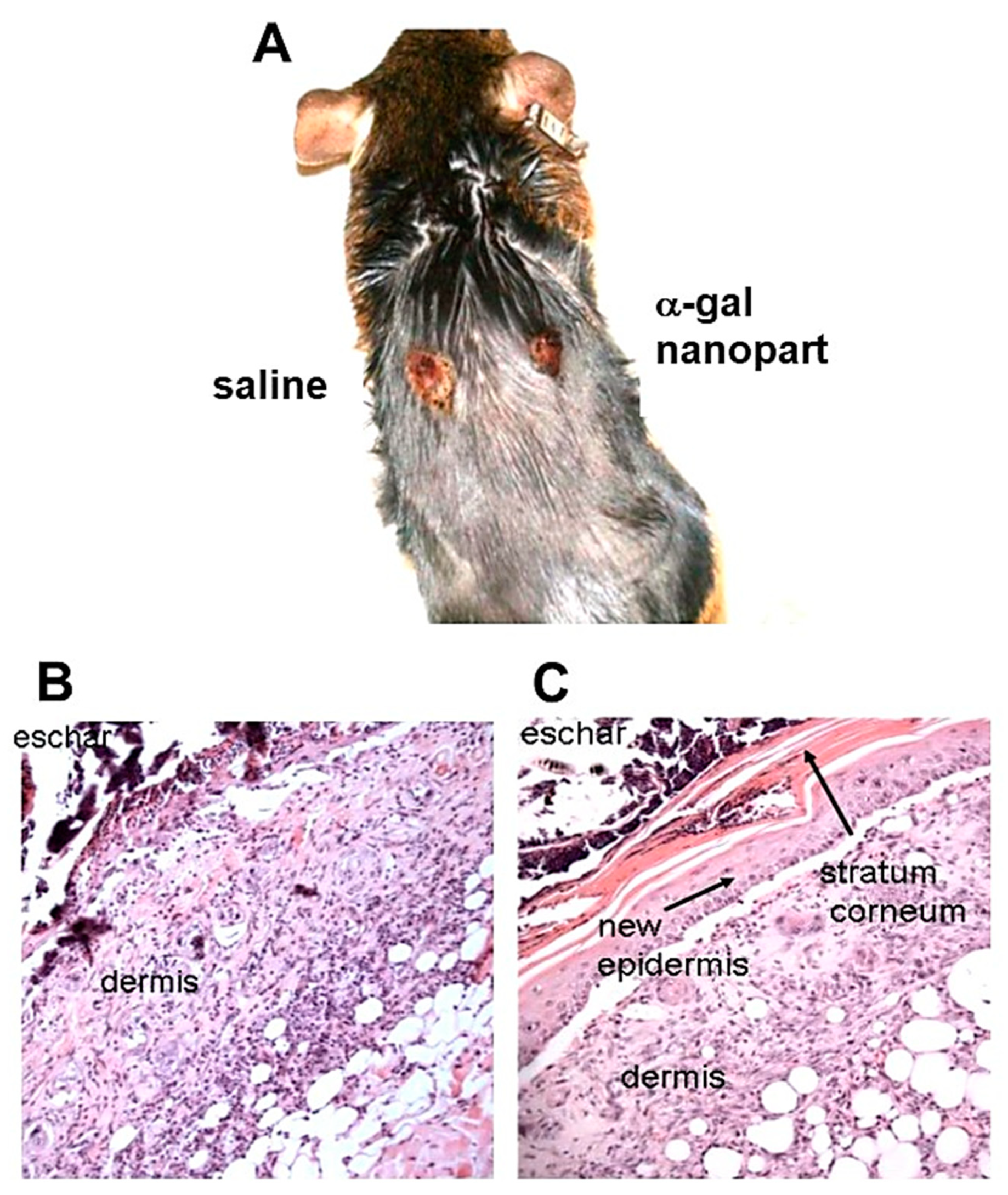

17]. For this purpose, 10 mg a-gal nanoparticles from a suspension containing 100 mg/ml, were dried under sterile conditions on 1x1cm pads of small “spot” bandages. Pads with dried 0.1ml saline served as controls. Two thermal injuries were performed on shaved two abdominal flanks of anesthetized mice by a brief contact of heated end of a metal spatula (~2x3 mm), resulting in a second degree burn affecting epidermis and dermis, but not the hypodermis. The right side burns were covered with α-gal nanoparticles coated spot bandages, and the left side burns with control saline containing spot bandages (

Figure 5A). Removal of the bandages by the mice was prevented by covering them with Tegaderm

TM and with Transpore

TM adhesive tape. The dressings were removed at various time points, the extent of covering the burn by re-epithelialization and macrophage infiltration were measured and the burn areas were sectioned and subjected to histologic staining by hematoxylin & eosin (H&E) (

Figure 5B,C and

Figure 6) and by Mason trichrome that stains collagen blue (

Figure 7). The extent of macrophages infiltrates into burns and of re-epithelialization (i.e., covering of the burn injury by regenerating epidermis) are presented in

Figure 8A and 8B, respectively.

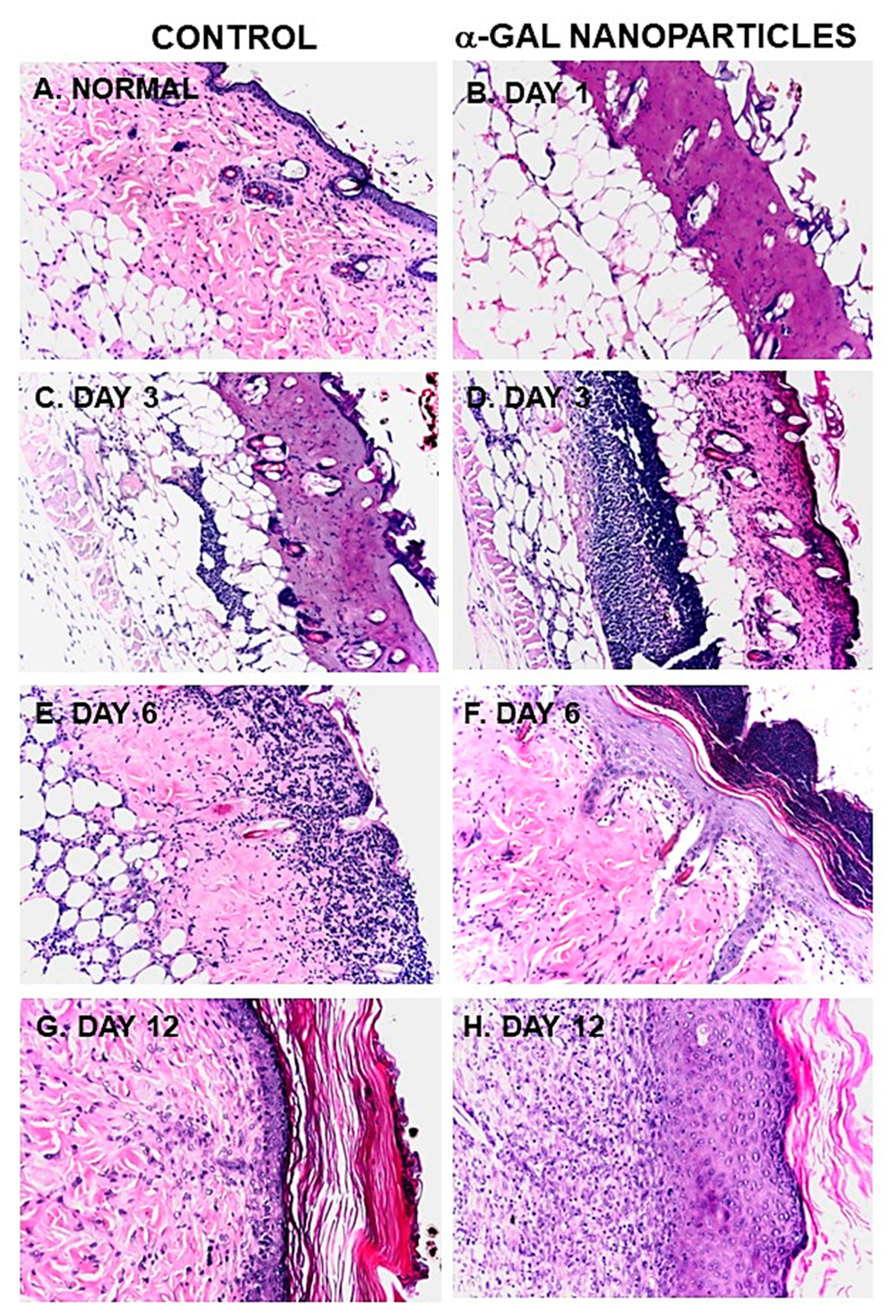

The histology of a representative normal mouse skin is presented in

Figure 6A and

Figure 7F. The epidermis in such skins is comprised of 2-3 layers of epithelial cells, the underlying dermis is stained pink by H&E and blue by Mason trichrome and the hypodermis contained mostly fat tissue, characterized by multiple adipocytes. The thermal injuries in the mouse skin resulted in destruction of both the epidermis and the dermis, as observed 24 hours post injury (

Figure 6B). This damage is similar to second degree burns in humans, in that both epidermis and dermis are destroyed, whereas damage to the hypodermis is minimal. No differences have been observed 24 hours post injury in a-gal nanoparticles treated burns (

Figure 6B) and in burns treated with saline (not shown).

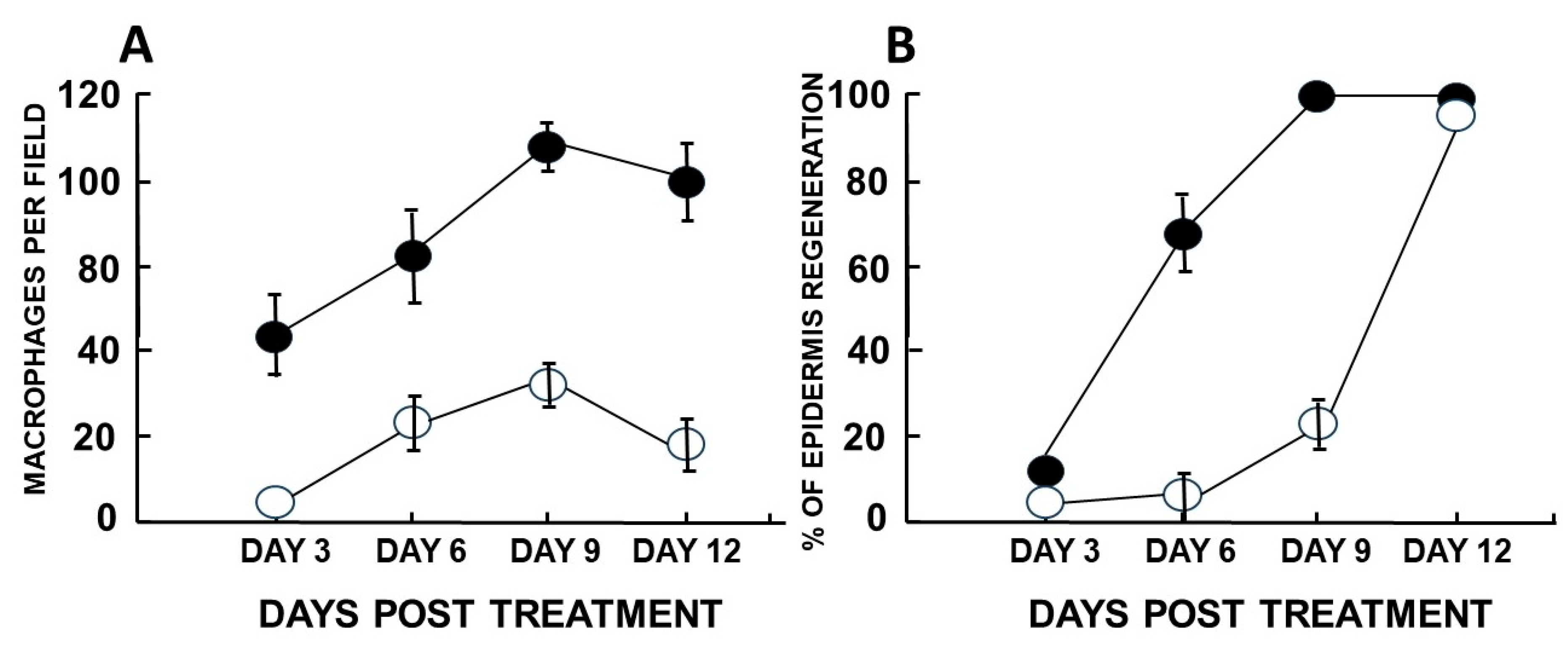

A major difference was observed between treated and control burns, inspected 3 days post injury. Whereas no significant number of macrophages was observed in control burns, as many as 40 macrophages were detected in same size field in a-gal nanoparticles treated burns (

Figure 6C,D and

Figure 8A). In addition, control burns displayed some degree of neutrophils infiltration, but a-gal nanoparticles treated burns displayed ~5 fold higher number of neutrophils (

Figure 6C,D).

The most dramatic difference between the two burn treatments was observed 6 days post thermal injury. At that time point, a-gal nanoparticles treated burns displayed extensive regeneration of epidermis as 50-100% re-epithelialization of the surface areas (mean of ~70%) (

Figure 8B). The newly formed epidermis also included formation of

stratum corneum (

Figure 5C and

Figure 6D). Many of the macrophages and neutrophils were found to be removed to the surface of the regenerating epidermis, above the

stratum corneum and were mixed with remnants of the eschar. This accelerated healing was found to be dose depended since 1 mg of a-gal nanoparticles induced an average of 23% healing after 6 days and 0.1 mg elicited not measurable healing [

17]. No significant epidermis regeneration was observed on Day 6 in control burns (

Figure 5B,

Figure 6C and

Figure 8B). Nevertheless, the dermis displayed increasing numbers of macrophages in a state of migration to the apical area of the injured dermis.

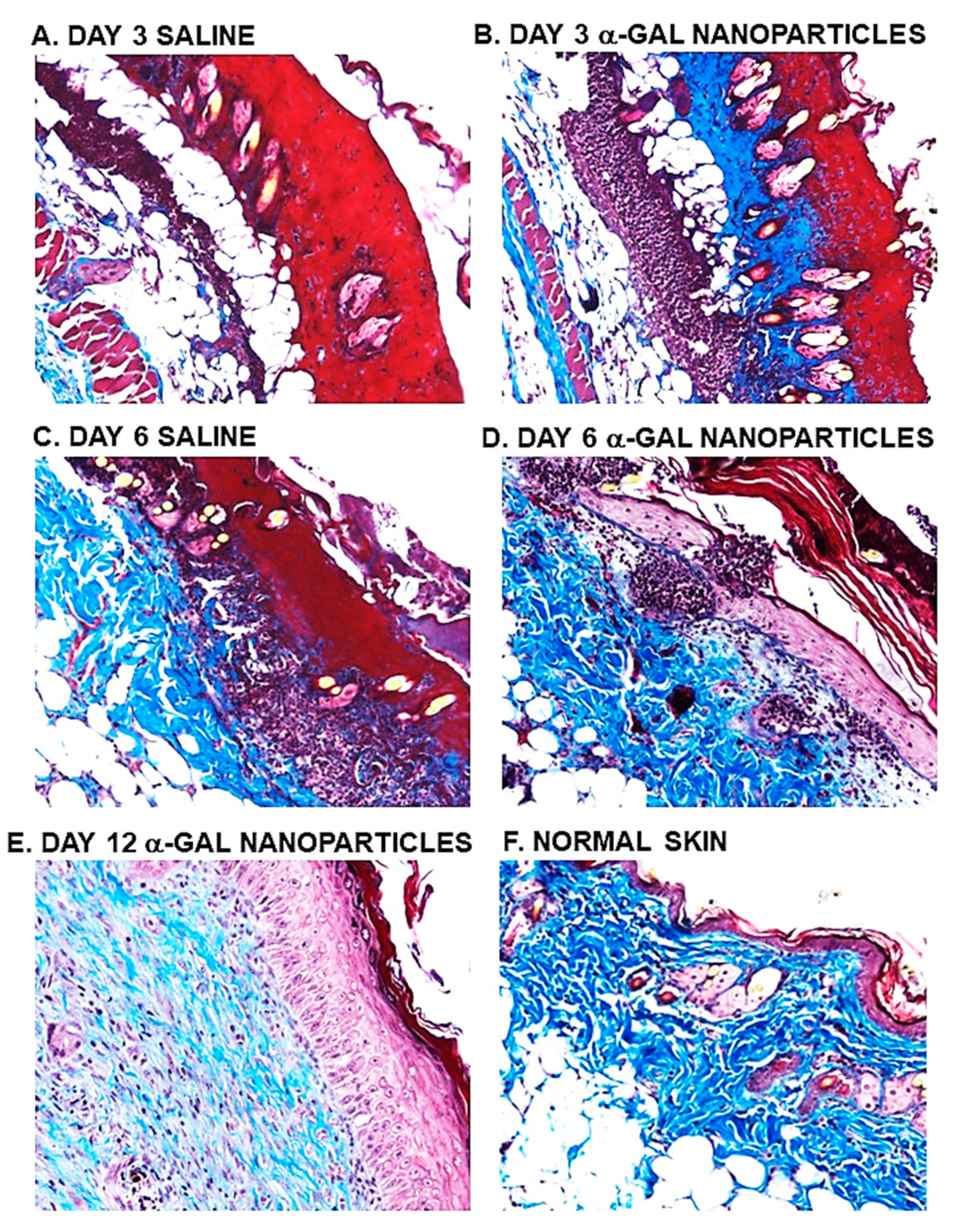

Evaluation of dermis regeneration was performed by Mason trichrome which stained blue

de novo synthesized collagen. Near complete regeneration of the dermis was observed in a-gal nanoparticles treated burns after 6 days (

Figure 7D), whereas in control burns much of the dermis was stained red, characteristic of thermal damage of the dermis (

Figure 7A,C). Initial indication of re-epithelialization of control burns was observed on Day 9, in which ~20% of the burn surfaces were covered by regenerating epidermis (

Figure 8B). In contrast, 100% of the a-gal nanoparticles treated burns were healed by that time point. By Day 12, all control burns displayed complete healing as that observed in a-gal nanoparticles treated burns (

Figure 6G, 6H,

Figure 7E and

Figure 8B). All treated and control healed burns did not develop keloids. These findings imply that topical application of a-gal nanoparticles to burns accelerates burns healing and cuts the healing time by ~40%-50%. It is of note that in the absence of anti-Gal (e.g., in wild-type mice), no difference in the healing process was observed between control burns and burns treated with a-gal nanoparticles. Both were similar to the healing of control burns in anti-Gal producing GT-KO mice [

17].

10. α-Gal Nanoparticles Mediated Accelerated Healing of Wounds

Since both healing processes of burns and wounds are mediated by macrophages, it was of interest to determine whether a-gal nanoparticles treatment has similar accelerating effects on wound healing in anti-Gal producing GT-KO mice, as the effects described above in burns healing. Oval shaped full thickness wounds (~6x9 mm) were performed in anesthetized anti-Gal producing GT-KO mice. The wounds were covered with spot bandage dressings containing 10 mg dried a-gal nanoparticles or with control spot bandage dressing containing saline. The healing of the wounds was evaluated by re-epithelialization at various time points. As with treated burns, wounds treated with a-gal nanoparticles completely healed by Day 6 post treatment, whereas control wounds healed only after 12-14 days [

18,

48]. Studies on completely healed treated and control wounds, 28 days post injury, indicated that, healing of saline treated control wounds resulted in fibrosis and scar formation, characteristic to the physiologic default healing of untreated wounds. In contrast, healing of a-gal nanoparticles treated wounds resulted in restoration of the normal structure of skin including re-appearance of skin appendages such as hair, sebaceous glands, and hypodermal adipocytes [

48]. It was suggested that the accelerated recruitment and activation of macrophages resulted in regeneration of the normal skin structure prior to the initiation of the default fibrosis and scar formation processes, thereby avoiding the latter processes [

18,

47]. It should be noted that a similar healing that includes restoration of the original structure and function was observed in anti-Gal producing GT-KO mice following myocardial infarction (MI) which was treated by injections of a-gal nanoparticles [

59]. In contrast, post infarction ischemic myocardium injected with saline displayed fibrosis and scar formation, similar to the pathology observed in post-MI injured myocardium in humans.

11. Concluding Remarks

Burn healing can be accelerated by the use of a-gal nanoparticles, which harness the immunologic potential of the natural anti-Gal antibody, an abundant antibody in humans constituting ~1% of immunoglobulins. Application of a-gal nanoparticles to burns results in binding of anti-Gal to the a-gal epitopes on these nanoparticles. This interaction activates the complement system, resulting in formation of complement cleavage chemotactic peptides, that direct rapid and extensive migration of monocytes derived macrophages into the treated burns. These recruited macrophages bind via their Fcg receptors the Fcg “tails” of anti-Gal coating the a-gal nanoparticles and are activated to into an M2 polarization state. The activated macrophages further produce a variety of cytokines/growth factors that mediate accelerated regrowth of the epidermis and regeneration of the injured dermis. In anti-Gal producing mice the accelerated epidermal regrowth results in covering of burn with intact epidermis, twice as fast as physiologic regrowth. Similarly, healing of a-gal nanoparticles treated burns in these mice is 40–60% faster than physiologic burn healing. The a-gal nanoparticles are non-toxic, and do not induce chronic granulomas or keloids. In addition, the a-gal nanoparticles are highly stable for long periods at various temperatures, and in view of their accelerated healing effects they may be considered for treatment of human burns. Accelerated healing by a-gal nanoparticles is also observed in treated wounds of anti-Gal producing mice. Application of a-gal nanoparticles to burns and wounds may be feasible in the form of dried nanoparticles on wound dressings and as suspensions, aerosols, hydrogels, or incorporated into sheets of biodegradable scaffold materials such as collagen sheets.

References

- Mahdavian Delavary, B.; van der Veer, W M. ; van Egmond, M.; Niessen, F.B.; Beelen, R.H. Macrophages in skin injury and repair. Immunobiology. 2011, 216, 753–762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- DiPietro, L.A.; Koh, T.J. Macrophages and wound healing. Adv. Wound Care 2016, 2, 71–75. [Google Scholar]

- Suda, S.; Williams, H.; Medbury, H.J.; Holland, A.J. A Review of Monocytes and Monocyte-Derived Cells in Hypertrophic Scarring Post Burn. J. Burn Care Res. 2016, 37, 265–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- 4. Penatzer JA, Srinivas S, Thakkar RK. The role of macrophages in thermal injury. Int J Burns Trauma. 2022; 12, 1–12.

- Italiani, P.; Boraschi, D. From Monocytes to M1/M2 macrophages: phenotypical vs. functional differentiation. Front. Immunol. 2014, 5, 514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singer, A.J; Clark, R.A. Cutaneous wound healing. N. Engl. J. Med. 1999, 341, 738–746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeschke, M.G.; van Baar, M.E.; Choudhry, M.A.; Chung, K.K.; Gibran, N.S.; Logsetty, S. Burn injury. Nat. Rev. Dis. Primer. 2020, 6, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piccolo, M.T.; Wang, Y.; Sannomiya, P.; Piccolo, N.S.; Piccolo, M.S.; Hugli, T.E.; Ward, P.A.; Till, G.O. Chemotactic mediator requirements in lung injury following skin burns in rats. Exp. Mol. Pathol. 1999, 66, 220–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shukaliak, J.; Dorovini-Zis, K. Expression of the [β]-Chemokines RANTES and MIP-1β by Human Brain Microvessel Endothelial Cells in Primary Culture. J. Neuropathol. Exp. Neurol. 2000, 59, 339–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shallo, H.; Plackett, T.P.; Heinrich, S.A.; Kovacs, E.J. Monocyte chemoattractant protein-1 (MCP-1) and macrophage infiltration into the skin after burn injury in aged mice. Burns 2003, 29, 641–647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heinrich, S.A.; Messingham, K.A.; Gregory, M.S.; Colantoni, A.; Ferreira, A.M.; Dipietro, L.A.; Kovacs, E.J. Elevated monocyte chemoattractant protein-1 levels following thermal injury precede monocyte recruitment to the wound site and are controlled, in part, by tumor necrosis factor-α. Wound Repair Regen. 2003, 11, 110–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tyler MP, Watts AM, Perry ME, Roberts AH, McGrouther DA. Dermal cellular inflammation in burns. An insight into the function of dermal microvascular anatomy. Burns 2001, 27, 433–438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martin, P.; Leibovich, S. J. Inflammatory cells during wound repair: the good, the bad and the ugly. Trends. Biol. 2005, 15, 599–607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Franz, M.G.; Steed, D.L.; Robson, M.C. Optimizing healing of the acute wound by minimizing complications. Curr. Probl. Surg. 2007, 4, 691–763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alexander, M.; Chaudry, I.H.; Schwacha, M.G. Relationships between burn size, immunosuppression, and macrophage hyperactivity in a murine model of thermal injury. Cell. Immunol. 2002, 220, 63–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schwacha, M.G. Macrophages and post-burn immune dysfunction. Burns 2003, 29, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galili, U.; Wigglesworth, K.; Abdel-Motal, U.M. Accelerated healing of skin burns by anti-Gal/α-gal liposomes interaction. Burns 2010, 36, 239–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galili, U. α-Gal Nanoparticles in Wound and Burn Healing Acceleration. Adv. Wound Care (New Rochelle). 2017, 6, 81–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hocking, A.M. Mesenchymal Stem Cell Therapy for Cutaneous Wounds. Adv. Wound Care (New Rochelle). 2012, 1, 166–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jo, H. , Brito, S.; Kwak, B.M.; Park, S.; Lee, M.G.; Bin, B.H. Applications of Mesenchymal Stem Cells in Skin Regeneration and Rejuvenation. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 2410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernon, C,A. ; Dawson, R.A.; Freedlander, E.; Short, R.; Haddow, D.B.; Brotherston, M.; MacNeil, S. Clinical experience using cultured epithelial autografts leads to an alternative methodology for transferring skin cells from the laboratory to the patient. Regen. Med. 2006, 1, 809–821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, H. Outcomes of sprayed cultured epithelial autografts for full-thickness wounds: a single-centre experience. Burns 2012, 38, 931–936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yuan, L.; Minghua, C.; Feifei, D.; Runxiu, W.; Ziqiang, L.; Chengyue, M. , Wenbo, J. Study of the use of recombinant human granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor hydrogel externally to treat residual wounds of extensive deep partial-thickness burn. Burns 2015, 41, 1086–1091. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yan, D.; Liu, S.; Zhao, X.; Bian, H.; Yao. X.; Xing, J.; Sun, W.; Chen, X. Recombinant human granulocyte macrophage colony stimulating factor in deep second-degree burn wound healing. Medicine (Baltimore) 2017, 96, e6881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lavker, R.M.; Kaplan, N.; McMahon, K.M.; Calvert, A.E.; Henrich, S.E.; Onay, U.V.; Lu, K.Q.; Peng, H.; Thaxton, C.S. Synthetic high-density lipoprotein nanoparticles: Good things in small packages. Ocul. Surf. 2021, 21, 19–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hermosilla, J.; Pastene-Navarrete, E.; Acevedo, F. Electrospun Fibers Loaded with Natural Bioactive Compounds as a Biomedical System for Skin Burn Treatment. A Review. Pharmaceutics 2021, 13, 2054; [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Weng, T.; Wang, J.; Yang, M.; Zhang, W.; Wu, P.; You, C.; Han, C.; Wang, X. Nanomaterials for the delivery of bioactive factors to enhance angiogenesis of dermal substitutes during wound healing. Burns Trauma 2022, 10, tkab049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frear, C.C.; Griffin, B.R.; Cuttle, L.; Kimble, R.M.; McPhail, S.M. Cost-effectiveness of adjunctive negative pressure wound therapy in pediatric burn care: evidence from the SONATA in C randomized controlled trial. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 16650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galili, U.; Rachmilewitz, E.A.; Peleg, A.; Flechner, I. A unique natural human IgG antibody with anti-α-galactosyl specificity. J. Exp. Med. 1984, 160, 1519–1531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galili, U.; Mandrell, R.E.; Hamadeh, R.M.; Shohet, S.B.; Griffiss, J.M. Interaction between human natural anti-α-galactosyl immunoglobulin G and bacteria of the human flora. Infect. Immun. 1988, 56, 1730–1737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mañez, R.; Blanco, F.J.; Díaz, I.; Centeno, A.; Lopez-Pelaez, E.; Hermida, M.; Davies, H.F.; Katopodis, A. Removal of bowel aerobic gram-negative bacteria is more effective than immunosuppression with cyclophosphamide and steroids to decrease natural α-galactosyl IgG antibodies. Xenotransplantation 2001, 8, 15–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galili, U.; Macher, B.A.; Buehler, J.; Shohet, S.B. Human natural anti-α-galactosyl IgG. II. The specific recognition of α[1,3]-linked galactose residues. J. Exp. Med. 1985, 162, 573–582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Towbin, H.; Rosenfelder, G.; Wieslander, J.; Avila, J.L.; Rojas, M.; Szarfman, A.; Esser, K.; Nowack, H.; Timpl, R. Circulating antibodies to mouse laminin in Chagas disease, American cutaneous leishmaniasis, and normal individuals recognize terminal galactosyl [α1-3]-galactose epitopes. J. Exp. Med. 1987, 166, 419–432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Teneberg, S.; Lönnroth, I.; Torres Lopez, J.F.; Galili, U.; Olwegard Halvarsson, M.; Angstrom, J.; Karlsson, K.A. Molecular mimicry in the recognition of glycosphingolipids by Galα3Galß4GlcNAcß-binding Clostridium difficile toxin A, human natural anti-α-galactosyl IgG and the monoclonal antibody Gal-13: Characterization of a binding-active human glycosphingolipid, non-identical with the animal receptor. Glycobiology 1996, 6, 599–609. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Galili, U.; Clark, M.R.; Shohet, S.B.; Buehler, J.; Macher, B.A. Evolutionary relationship between the anti-Gal antibody and the Galα1-3Gal epitope in primates. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1987, 84, 1369–1373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Galili, U.; Shohet, S.B.; Kobrin, E.; Stults, C.L.M.; Macher, B.A. Man, apes, and Old-World monkeys differ from other mammals in the expression of α-galactosyl epitopes on nucleated cells. J. Biol. Chem. 1988, 263, 17755–17762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thall, A.; Galili, U. Distribution of Gal alpha 1----3Gal beta 1----4GlcNAc residues on secreted mammalian glycoproteins (thyroglobulin, fibrinogen, and immunoglobulin G) as measured by a sensitive solid-phase radioimmunoassay. Biochemistry 1990, 29, 3959–3965. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oriol, R.; Candelier, J.J.; Taniguchi, S.; Balanzino, L.; Peters, L.; Niekrasz, M.; Hammer, C.; Cooper, D.K. Major carbohydrate epitopes in tissues of domestic and African wild animals of potential interest for xenotransplantation research. Xenotransplantation 1999, 6, 79–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cooper, D.K.C.; Good, A.H.; Koren, E.; Oriol, R.; Malcolm, A.J.; Ippolito, R.M.; Neethling, F.A.; Ye, Y.; Romano, E.; Zuhdi, N. Identification of α-galactosyl and other carbohydrate epitopes that are bound by human anti-pig antibodies: Relevance to discordant xenografting in man. Transpl. Immunol. 1993, 1, 198–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galili, U. Interaction of the natural anti-Gal antibody with α-galactosyl epitopes: A major obstacle for xenotransplantation in humans. Immunol. Today 1993, 14, 480–482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sandrin, M.S.; Vaughan, H.A.; Dabkowski, P.L.; McKenzie, I.F.C. Anti-pig IgM antibodies in human serum react predominantly with Gal (αl-3)Gal epitopes. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1993, 90, 11391–11395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collins, B.H.; Cotterell, A.H.; McCurry, K.R.; Alvarado, C.G.; Magee, J.C.; Parker, W.; Platt, J.L. Cardiac xenografts between primate species provide evidence for the importance of the α-galactosyl. determinant in hyperacute rejection. J. Immunol. 1995, 154, 5500–5510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Repik, P.M.; Strizki, M.; Galili, U. Differential host dependent expression of α-galactosyl epitopes on viral glycoproteins: A study of Eastern equine encephalitis virus as a model. J. Gen. Virol. 1994, 75, 1177–1181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pipperger, L.; Koske, I.; Wild, N.; Müllauer, B.; Krenn, D.; Stoiber, H.; Wollmann, G.; Kimpel, J.; von Laer, D.; Bánki, Z. Xenoantigen-dependent complement-mediated neutralization of LCMV glycoprotein pseudotyped VSV in human serum. J. Virol. 2019, 93, e00567–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Takeuchi, Y.; Porter, C.D.; Strahan, K.M.; Preece, A.F.; Gustafsson, K.; Cosset, F.L.; Weiss, R.A.; Collins, M.K. Sensitization of cells and retroviruses to human serum by [α1-3] galactosyltransferase. Nature 1996, 379, 85–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Preece, A.F.; Strahan, K.M.; Devitt, J.; Yamamoto, F.; Gustafsson, K. Expression of ABO or related antigenic carbohydrates on viral envelopes leads to neutralization in the presence of serum containing specific natural antibodies and complement. Blood 2002, 99, 2477–2482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Galili, U. book “The natural anti-Gal antibody as foe turned friend in medicine” Academic Press/Elsevier, London, New York, 2018, pp. 207–228.

- Wigglesworth, K.M.; Racki, W.J.; Mishra, R.; Szomolanyi-Tsuda, E.; Greiner, D.L.; Galili, U. Rapid recruitment and activation of macrophages by anti-Gal/α-Gal liposome interaction accelerates wound healing. J. Immunol. 2011, 186, 4422–4432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thall, A.D.; Maly, P.; Lowe, J.B. Oocyte Gal1,3Gal epitopes implicated in sperm adhesion to the zona pellucida glycoprotein ZP3 are not required for fertilization in the mouse. J. Biol. Chem. 1995, 270, 21437–21440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tearle, R.G.; Tange, M.J.; Zanettino, Z.L.; Katerelos, M.; Shinkel, T.A.; Van Denderen, B.J.; Lonie, A.J.; Lyonsm, I. , Nottle, M.B.; Cox, T. et al. The alpha-1,3-galactosyltransferase knockout mouse. Implications for xenotransplantation. Transplantation 1996, 61, 13–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lai, L.; Kolber-Simonds, D.; Park, K.W.; Cheong, H.T.; Greenstein, J.L.; Im, G.S.; Samuel, M.; Bonk, A.; Rieke, A.; Day, B.N.; et al. Production of α-1,3-galactosyltransferase knockout pigs by nuclear transfer cloning. Science 2002, 295, 1089–1092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phelps, C.J.; Koike, C.; Vaught, T.D.; Boone, J.; Wells, K.D.; Chen, S.H.; Ball, S.; Specht, S.M.; Polejaeva, I.A.; Monahan, J.A.; et al. Production of α1,3-galactosyltransferase-deficient pigs. Science 2003, 299, 411–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dor, F.J.; Tseng, Y.L.; Cheng, J.; Moran, K.; Sanderson, T.M.; Lancos, C.J.; Shimizu, A.; Yamada, K.; Awwad, M.; Sachs, D.H.; et al. α1,3-Galactosyltransferase gene-knockout miniature swine produce natural cytotoxic anti-Gal antibodies. Transplantation 2004, 78, 15–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fang, J.; Walters, A.; Hara, H.; Long, C.; Yeh, P.; Ayares, D.; Cooper, D.K.; Bianchi, J. Anti-gal antibodies in α1,3- galactosyltransferase gene knockout pigs. Xenotransplantation 2012, 19, 305–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Galili, U. The natural anti-Gal antibody and simulate the evolutionary appearance of this antibody in primates. Xenotransplantation 2013, 20, 267–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanemura, M.; Yin, D.; Chong, A.S.; Galili, U. Differential immune responses to α-gal epitopes on xenografts and allografts: Implications for accommodation in xenotransplantation. J. Clin. Investig. 2000, 105, 301–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaymakcalan, O.E.; Abadeer, A.; Goldufsky, J.W.; Galili, U.; Karinja, S.J.; Dong, X.; Jin, J.L.; Samadi, A.; Spector, J.A. Topical α-gal nanoparticles accelerate diabetic wound healing. Exp. Dermatol. 2020, 29, 404–413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galili, U.; Goldufsky, J.W.; Schaer, G.L. α-Gal Nanoparticles Mediated Homing of Endogenous Stem Cells for Repair and Regeneration of External and Internal Injuries by Localized Complement Activation and Macrophage Recruitment. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 11490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Galili, U.; Zhu, Z.; Chen, J.; Goldufsky, J.W.; Schaer, G.L. Near Complete Repair After Myocardial Infarction in Adult Mice by Altering the Inflammatory Response With Intramyocardial Injection of α-Gal Nanoparticles. Frontiers Cardiovasc. Med. 2021, 8, 719160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).