Submitted:

04 September 2023

Posted:

06 September 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

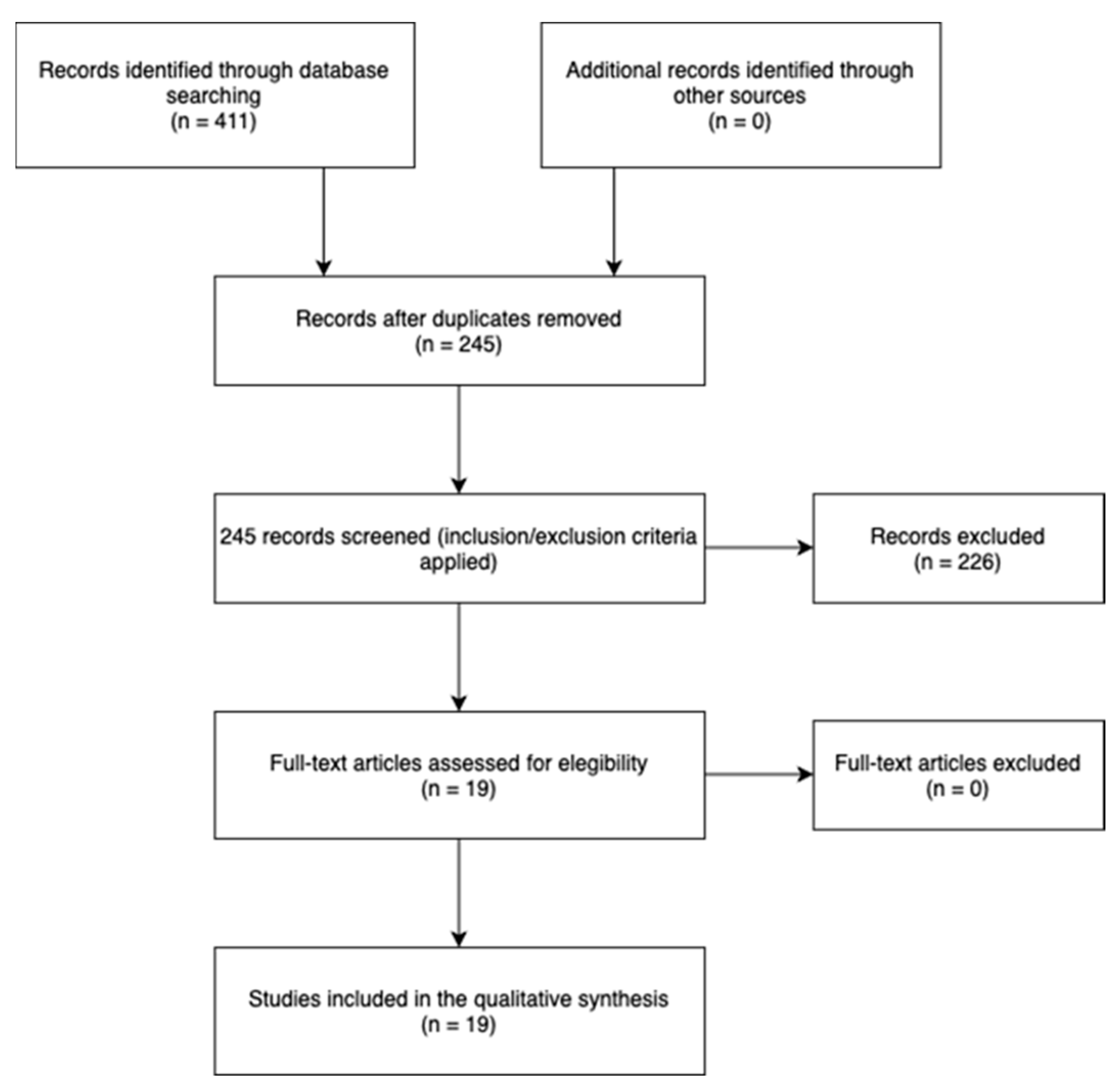

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Eligibility criteria

2.1.1. Inclusion Criteria

2.1.2. Exclusion Criteria.

2.1.3. Information Sources and Search Strategy.

2.1.4. Selection strategy

2.1.5. Methodological Quality

3. Results

| AUTHORS | q1 | q2 | q3 | q4 | q5 | q6 | q7 | q8 | q9 | q10 | q11 | q12 | q13 | q14 | q15 | q16 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bandara et al [32] (2021) | yes | partial yes | yes | partial yes | yes | yes | no | partial yes | no | no | yes | no | no | yes | no | no |

| Houck et al [33] (2017) | no | partial yes | yes | partial yes | yes | yes | no | partial yes | no | no | yes | no | yes | yes | no | yes |

| Li et al [34] (2017) | yes | partial yes | yes | partial yes | yes | yes | Partial Yes | yes | yes | no | yes | yes | yes | yes | yes | yes |

| Littlewood et al [35] (2014) | yes | partial yes | yes | partial yes | no | no | no | yes | no | yes | no-meta | no-meta | no | no | no-meta | no |

| Longo et al [36] (2021) | yes | partial yes | yes | partial yes | yes | yes | no | yes | yes | yes | yes | yes | yes | yes | yes | yes |

| Longo et al [37] (2021) | yes | partial yes | yes | partial yes | yes | yes | no | yes | yes | no | yes | yes | yes | yes | yes | yes |

| Matlak et al [38] (2021) | no | partial yes | yes | partial yes | yes | yes | no | yes | no | no | no-meta | no-meta | yes | no | no-meta | yes |

| Mazuquin et al [12] (2021) | yes | partial yes | yes | partial yes | yes | yes | yes | yes | yes | no | yes | yes | yes | yes | yes | yes |

| Saltzman et al [39] (2017) | no | partial yes | yes | partial yes | yes | yes | no | no | no | yes | no-meta | no-meta | no | yes | no-meta | no |

| Silveira et al [40] (2021) | yes | partial yes | yes | partial yes | yes | yes | partial yes | yes | yes | yes | yes | yes | yes | yes | yes | no |

| Thomson et al [41] (2015) | yes | partial yes | yes | yes | yes | yes | partial yes | partial yes | no | no | no-meta | no-meta | no | no | no-meta | yes |

| Gallagher et al [42] (2015) | yes | yes | yes | yes | no | no | no | yes | yes | no | no meta | no meta | yes | yes | no meta | yes |

| Chang et al [43] (2014) | yes | yes | yes | yes | yes | yes | partial yes | yes | yes | no | yes | yes | yes | yes | yes | yes |

| Chan et al [44] (2014) | yes | yes | yes | yes | yes | yes | yes | yes | partial yes | no | yes | yes | no | yes | yes | no |

| Shen et al [45] (2014) | yes | yes | yes | yes | yes | yes | no | partial yes | yes | no | yes | yes | no | yes | yes | no |

| Huang et al [46] (2013) | yes | partial yes | yes | yes | yes | no | no | yes | no | no | no | yes | no | yes | no | no |

| Riboh et al [47] (2014) | yes | yes | yes | yes | yes | yes | no | yes | yes | no | no | yes | yes | yes | yes | yes |

| Kluczynski et al [48] (2014) | yes | yes | yes | yes | no | no | no | partial yes | no | no | yes | no | no | yes | no | yes |

| Kluczynski et al [49] (2015) | yes | yes | yes | yes | yes | yes | no | yes | no | no | no | no | no | yes | no | yes |

| AUTHORS | ARTICLE TYPE | POPULATION | EVALUATION TIME | RESULTS | OUTCOMES AND SCALES | CONCLUSIONS | LIMITATIONS |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Bandara et al [32] |

Systematic review (6 RCT) |

531 patients Diagnosis: All participants received rotator cuff repair Average age and DS: non specified. M = non specified F = non specified |

T0 = first postoperative day T1 = 6 month after rotator cuff repair T2 = 12 month after rotator cuff repair |

= ROM EP > Constant-Murley Score (no increased risk of recurrence) |

Joints balance = ROM. Function = Constant-Murley Shoulder Score. Structure = Recurrence rate |

1) EP = TP - ROM. 2) EP > risk of recurrence but > functional recovery 3) EP = TP - safe and reproducible results in the short and long term. |

1 Variable design of each individual study. 2 High eterogeneity revealed in pooled analvses. 3 Variability in the description of each rehabilitation protocol and timing 4 Possibility of bias in a number of the included studies |

|

Houck et al [33] |

Systematic review (7 RCT) |

5896 patients Diagnosis: All participants received rotator cuff repair Average age: 46 - 59 years DS: non specified M = non specified F = non specified |

T0 = first postoperative day T1 = 6 month after rotator cuff repair T2 = 12 month after rotator cuff repair T3 = 24 month after rotator cuff repair |

EP > ROM EP > risk of recurrence TP > Cure rate TP > ASES score EP > small injuries TP > large injuries |

joints balance =ROM. Function = ASES score. Structure = Recurrence rate |

1) EP > ROM but > risk of recurrence |

1 lack of reporting follow-up results, age, sex, tear size, and the rotator cuff muscles involved. 2 surgical techniques inconsistently reported in the included studies. 3 risks of bias in the ROM reported due to a lack of blinding. |

|

Li et al [34] (2017) |

Systematic review (8 RCT) |

671 patients Diagnosis: All participants received rotator cuff repair Average age: 58,1 ± 3,9 DS M = non specified F = non specified |

T0 = first postoperative day T1 = 3 month after rotator cuff repair T2 = 6 month after rotator cuff repair T3 = 12-24 month after rotator cuff repair |

EP > ROM = cure rate, ASES at T2, SST, Constant-Murley score TP > ASES at T3 |

joints balance = ROM. Function = Constant-Murley Shoulder Score, ASES, SST. Structure = Recurrence rate |

1) EP> ROM but < shoulder functionality 2) EP< cure rate for large injuries |

1 number of trials relatively small 2 no high quality of evidence in all outcomes 4 outcome assessors were not blinded to rehabilitation protocol. 4 the standard deviation is not provided in some included studies. |

|

Littlewood et al [35] (2014) |

Systematic review (12 RCT) |

819 patients Diagnosis: All participants received rotator cuff repair Average age: 58,1 DS: non specified M = 430 F = 389 |

T0 = first postoperative day T1 = 3 month after rotator cuff repair T2 = 6 month after rotator cuff repair T3 = 12 month after rotator cuff repair |

= pain, risk of recurrence and disability |

Function = pain, disability Structure = Recurrence rate |

1) EP = TP |

1 small mean number of included participants per trial 2 only one reviewer identified relevant studies, extracted data, and synthesized the findings. |

|

Longo et al [36] (2021) |

Systematic review (16 RCT) |

1424 patients Diagnosis: All participants received rotator cuff repair Average age: 56,1 ± 8,7 DS PP 56,6 ± 9 DS PT M = 776 F = 648 |

T0 = first postoperative day T1 = 3 month after rotator cuff repair T2 = 6 month after rotator cuff repair T3 = 12 month after rotator cuff repair T4 = 24 month after rotator cuff repair |

EP > ROM external rotation at T1. EP > ROM T2. = ROM at T4. = risk of recurrence and Constant-Murley score |

joints balance = ROM. Function = Constant-Murley Shoulder Score. Structure = Recurrence rate |

1) = recurrence rate between the 2 groups 2) EP > external rotation at 3- and 6-months follow-up, but = at 24 |

1 lack of information on the RC tear characteristics 2 muscle atrophy and fatty infiltration was not specified in most of the included articles. 3 Differents early protocols in terms of exercise and timing |

|

Longo et al [37] (2021) |

Systematic review (31 RCT) |

5109 patients Diagnosis: All participants received rotator cuff repair Average age: 58,2 years ± 3,7 DS M = 2396. F = 2231 |

T0 = first postoperative day T1 = 3 month after rotator cuff repair T2 = 6 month after rotator cuff repair T3 = 12 month after rotator cuff repair T4 = 24 month after rotator cuff repair |

= immobilization period = passive ROM EP active ROM > risk of recurrence TP complete active ROM > risk of recurrence = strengthening exercises |

Structure = Recurrence rate |

1) = recurrence rate for immobilization, passive ROM, and force exercises. 2) EP active ROM > recurrence rate 3) TP full active ROM > recurrence rate |

1 insufficient number of studies reporting the preoperative tear size. 2 no conclusions regarding clinical outcomes were made. |

| Matlak et al [38] (2021) | Systematic review (22 RCT) | 1782 patients | T0 = first postoperative day | EP > ROM; | joints balance =ROM; | 1) EP = reduced risk of stiffness, improves ROM and function faster | 1 Lack of hig qualirty studies about subscapularis rehabilitation |

| Diagnosis: All participants received rotator cuff repair | T1 = 6 weeks after rotator cuff repair | EP > Function | Structure = Recurrence rate, rigidity | 2) TP = Reduced risk of recurrence. | |||

| Average age: 45 - 64,8 years | T2 = 3 month after rotator cuff repair | EP < Rigidity | Structure = strenght | 3) CPM can accelerate ROM gain but does not improve long-term results. | 2 Literature gaps about optimal dosage of frequency and intensity of exercise, ideal time to begin loading. | ||

| DS: non specified | T3 = 6 month after rotator cuff repair | TP < risk of recurrence | 4)Early isometric loading may be beneficial for increasing strength and tendon shaping but requires further research | ||||

| M = non specified | EP > strenght | ||||||

| F = non specified | |||||||

| Mazuquin et al [12] (2021) | Systematic review (20 RCT) | 1841 patients | T0 = first postoperative day | = VAS; | joints balance = ROM; | 1) EP > ROM and same tendon integrity | 1 The majority of the RCTs were considered of high or unclear overall risk of bias, had small sample sizes and their definition of early and delayed rehabilitation were not consistent |

| Diagnosis: All participants received rotator cuff repair | T1 = 6 weeks after rotator cuff repair | = ASES, Constant-Murley, SST, WORC; | Function = ASES, Constant-Murley Shoulder Score, SST, WORC; SANE; | 2 ubgroup analyses were not pos- sible due to the lack of data reported by tear size | |||

| Average age: 54 - 65,4 years | T2 = 3 month after rotator cuff repair | EP > SANE Score; | Structure = strength, tendon integrity | ||||

| DS: non specified | T3 = 6 month after rotator cuff repair | = Strength, tendon integrity | |||||

| M = non specified | T4 = 1 year after rotator cuff repair | EP > ROM short term | |||||

| F = non specified | T5 = 2 years after rotator cuff repair | TP > rigidity long term | |||||

| Saltzman et al [39] (2017) | Systematic review (9 RCT) | 265 -2251 patients | T0 = first postoperative day | = tendon healing, risk of recurrence, functional outcomes, and strength | joints balance = ROM; | 1) EP > ROM | Difficulty in controlling for heterogeneity, small sample sizes and narrow study populations, lack of blinding in individual studies |

| Diagnosis: All participants received rotator cuff repair | T1 = 6 month after rotator cuff repair | EP > ROM; | Function = ASES, Constant-Murley, SST, WORC; | 2) = Functional results and recurrence rate | |||

| Average age: 57,7 - 60,38 years | T2 = 12 month after rotator cuff repair | EP > risk of recurrence for large injuries | Structure = Recurrence rate and recovery rate | 3) EP > Recurrence rate for large injuries | |||

| DS: non specified | |||||||

| M = non specified | |||||||

| F = non specified | |||||||

| Silveira et al [40] (2021) | Systematic review (8 RCT) | 756 patients | T0 = first postoperative day | = pain, strength, and integrity | joints balance = ROM; | 1) EP > freedom of movement of the shoulder but worse quality of life; | Different tear size and surgical techniques |

| Diagnosis: All participants received rotator cuff repair | T1 = 6 weeks after rotator cuff repair | TP > WORC Index at T1, | Function = WORC Index, Constant-Murley score; | 2) Differences between groups do not appear to be clinically important | |||

| Average age: 50,43 - 57,68 years | T2 = 3 month after rotator cuff repair | = in other follow-up times | Structure = strength, tendon integrity | ||||

| DS: non specified | T3 = 6 month after rotator cuff repair | = Constant-Murley score; | |||||

| M= 442; | T4 = 1 year after rotator cuff repair | EP > ROM at T1, = in other follow-up times | |||||

| F= 344. | T5 = 2 years after rotator cuff repair | ||||||

| Thomson et al [41] (2015) | Systematic review (11 RCT) | 706 patients | T0 = first postoperative day | EP > ROM; | joints balance = ROM | 1) EP = TP | 1 Data extracted by only one reviewer 2 Language and publication bias |

| Diagnosis: All participants received rotator cuff repair | T1 = 6 month after rotator cuff repair | TP > large injuries | |||||

| Average age: 58,1 years | T2 = 12 month after rotator cuff repair | ||||||

| DS: non specified | |||||||

| M= non specified | |||||||

| F= non specified | |||||||

| Gallagher et al [42] (2015) | Systematic review (6 RCT) | 80 patients | T0 = first postoperative day | =risk of recurrence, PAIN | Function: Constant shoulder score, ASES, SST, UCLA and DASH score | EP better ROM in short term, but = in long term | 1 lack of uniform, prospective trials comparing similar rehabilitation protocols 2 All studies suffered from an intrinsic inability to properly blind individu- als and several suffered from inadequate randomization or insufficient incomplete outcome reporting |

| Diagnosis: All participants received rotator cuff repair | T1 = 3 month after rotator cuff repair | EP > ROM at T2, = ROM at T3 | |||||

| Average age: 54.5 - 63.2 | T2 = 6 month after rotator cuff repair | =stiffness, =healing | |||||

| DS: non specified | T3 = 12 month after rotator cuff repair | = ASES, SST, DASH | |||||

| M = non specified | EP > UCLA at T1, but = at T2 and T3 | ||||||

| F = non specified | |||||||

| Chang et al [43] (2014) | Systematic review (6 RCT) | 482 patients | T0 = closest day to surgery | =external rotation range | Function = UCLA and Costant | Early ROM exercises improve postoperative stifness but improper tendon healing in large-sized tears | 1 Small numbers of included trials |

| Diagnosis: All participants received rotator cuff repair | T1 = 6 month after rotator cuff repair | EP > shoulder forward flexion range at T1 and T2 | 2 heterogeneities among the included articles regarding the severity of the rotator cuff tears, surgical techniques, and functional outcome assessment scales | ||||

| Average age: 54.5 - 63.5 | T2 = 12 month after rotator cuff repair | EP > recurrency | Structure = recurrence rate | 3 not all the included trials reported | |||

| DS: non specified | EP = reduce stiffness | reoperation rate | |||||

| M = 233 | |||||||

| F = 249 | |||||||

| Chan et al [44] (2014) | Systematic review (4 RCT) | 370 patients | T0 = closest day to surgery | = ASES (4 RCT), CMS (2 RCT), SST, WORC | Function = ASES, Constant, SST, WORC, DASH | No statistically significant differences in functional outcomes scores, relative risks of recurrent rotator cuff tears | 1 Unavailable data for several studies included in the review. |

| Diagnosis: All participants received rotator cuff repair | T1 = latest time point in all trials | = recurrence | Structure = recurrence rate | 2 None of the outcomes were judged to be of high quality by the author | |||

| Average age: 65 | = ROM | Joint balance = ROM | 3 Lack of blinding | ||||

| DS: non specified | |||||||

| M = 203 | |||||||

| F = 167 | |||||||

| Shen et al [45] (2014) | Systematic review (3 RCT) | 265 patients | T0 = day one post-operatory | EP > Constant (1 RTC) at 12 months | Function = ASES, Constant, SST | No significant differences in tendon healing. EP > external rotation at six moths but no at 1 year | 1 small number of rcTs included |

| Diagnosis: All participants received rotator cuff repair | T1 = 6 months | = ASES, SST e VAS | Pain = VAS | EP Fastest ROM recovery | 2 some clinical heterogeneity among trials | ||

| Average age: 55.3 - 63.5 | T2 = 12 months | = tendon healing | |||||

| DS: non specified | = ROM | ||||||

| Huang et al [46] (2013) | Systematic review (6 RCT) | 448 patients | T0 = day one post-operatory | EP > ROM | Function: DASH, Constant, ASES, SST | EP > ROM but greater risk of un-healing or re-tearing | 1 few article with variable outcome measures and time points of follow-up |

| Diagnosis: All participants received rotator cuff repair | T1 = 6 months | EP > function | Pain = VAS | 2 data of some studies did not fit normal distributions and could not be calculated | |||

| Average age: 55 - 63 | T2 = 12 months | TP > healing | Structure = healing | ||||

| DS: non specified | EP > risk of retear | 3 all articles were only of fair quality | |||||

| EP > VAS at week 5 and 16, but EP = TP | |||||||

| at T1 and T2 | |||||||

| Riboh et al [47] (2014) | Systematic review (5 RCT) | 451 patients | T0 = day one post-operatory | Function = Constant, SST, ASES, UCLA | EP > shoulder forward flexion at 3/6/12 months, external rotation only at 3 months | 1 methodologic limitations and moderate risk of bias of 3 of the 5 randomized studies included | |

| Diagnosis: All participants received rotator cuff repair | T1 = 3 months | = recurrence | Pain = VAS | = recurrency | 2 all of the studies suffered from performance bias because neither surgeons nor patients could be blinded to the treatment-group assignment. | ||

| Average age: 54.8 - 63.2 | T2 = 6 months | EP > ROM | Structure = healing | 3 All 5 studies provide only Level II data | |||

| DS: non specified | T3 = 12 months | ||||||

| Kluczynski et al [48] 2014 | Meta Analysis (28 RCT) | 1729 patients | T0 = day one post-operatory | EP > risk of retear >5cm | Structure = recurrence rate, healing | EP greater risk of retear for >5cm tears, TP greater risk for <3cm tears | 1 RC healing as only outcome examinated |

| Diagnosis: All participants received rotator cuff repair | T1 = latest time point in all trials | TP > risk of retear <3cm | 2 Most studies included in this review provided evidence levels of 2 to 4 | ||||

| 3 Focused only on passive ROM | |||||||

| Average age: non specified | |||||||

| DS: non specified | |||||||

| Kluczynski et al [49] 2015 | Meta Analysis (37 RCT) | 2251 patients | T0 = day one post-operatory | EP > risk of retear | Structure = recurrence rate, healing | EP greater risk of retear for >5cm tears ad <3cm tears | 1 RC healing as only outcome examinated |

| Diagnosis: All participants received rotator cuff repair | T1 = latest time point in all trials, at least 1 year | 2 focused only on the active ROM component of rehabilitation | |||||

| 3 unable to control for the heterogeneity of these studies | |||||||

| Average age: non specified | 4 small sample size of the early active ROM group | ||||||

| DS: non specified | |||||||

| RCT = Randomized Controlled Trial; ROM = Range Of Motion; EP = Early Protocol; TP = Traditional Protocol; ASES = American Shoulder and Elbow Society; CPM = Continuous Passive Motion; WORC Index = Western Ontario Rotator Cuff Index; SST = Simple Shoulder Test; SANE = Single Assessment Numeric Evaluation; VAS = Visual Analalogic Scale; UCLA = UNiversity of CAliforna Los Angeles; DASH = Disabilities of the Arm, Shoulder and Hand; CMS = Constant-Marley Scale | |||||||

4. Discussion

4.1. Pain

4.2. Functional Recovery

4.3. Risk of Retear

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Littlewood, C.; May, S.; Walters, S. Epidemiology of Rotator Cuff Tendinopathy: A Systematic Review. Shoulder Elbow 2013; 5, 256–265. [CrossRef]

- Lädermann, A.; Denard, P.J.; Collin, P. Massive rotator cuff tears: definition and treatment. Int Orthop 2015, 39, 2403–2414. [CrossRef]

- Keener, J.D.; Patterson, B.M.; Orvets, N.; Chamberlain, A.M. Degenerative rotator cuff tears: Refining surgical indications based on natural history data. Journal of the American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons 2019, 27, 156–165. [CrossRef]

- Yazdani, A.N.; Rai, V.; Agrawal, D.K. Rotator Cuff Health, Pathology, and Repair in the Perspective of Hyperlipidemia. J Orthop Sports Med. 2022, 4, 263-275. [CrossRef]

- Razmjou, H.; Lincoln, S.; Axelrod, T.; Holtby, R. Factors Contributing to Failure of Rotator Cuff Surgery in Persons with Work-Related Injuries. Physiotherapy Canada 2008, 60, 125. [CrossRef]

- Oh, J.H.; Park, M.S.; Rhee, S.M. Treatment Strategy for Irreparable Rotator Cuff Tears. Clin Orthop Surg 2018, 10, 119–134.

- Tempelhof, S.; Rupp, S.; Seil, R. Age-related prevalence of rotator cuff tears in asymptomatic shoulders. J Shoulder Elbow Surg 1999, 8, 296–9. [CrossRef]

- Minagawa, H.; Yamamoto, N.; Abe, H.; Fukuda, M.; Seki, N.; Kikuchi, K.; Kijima, H.; Itoi, E. Prevalence of symptomatic and asymptomatic rotator cuff tears in the general population: From mass-screening in one village. J Orthop 2013, 10, 8–12. [CrossRef]

- Littlewood, C.; Bateman, M.; Butler-Walley, S.; Bathers, S.; Bromley, K.; Lewis, M.; Funk, L.; Denton, J.; Moffatt, M.; Winstanley, R.; Mehta, S.; Stephens, G.; Dikomitis, L.; Foster, N.E. Rehabilitation following rotator cuff repair: A multi-centre pilot & feasibility randomised controlled trial (RaCeR). Clin Rehabil 2021. 35, 829–839. [CrossRef]

- Gartsman, G.M. Arthroscopic management of rotator cuff disease. J Am Acad Orthop Surg 1998, 6, 259–66. [CrossRef]

- Ensor, K.L.; Kwon, Y.W.; Dibeneditto, M.R.; Zuckerman, J.D.; Rokito, A.S. The rising incidence of rotator cuff repairs. J Shoulder Elbow Surg 2013, 22, 1628–32. [CrossRef]

- Mazuquin, B.; Moffatt, M.; Gill, P.; Selfe, J.; Rees, J.; Drew, S.; Littlewood, C. Effectiveness of early versus delayed rehabilitation following rotator cuff repair: Systematic review and meta-analyses. PLoS One 2021, 16,5, e0252137. [CrossRef]

- Jain, N.B.; Higgins, L.D.; Losina, E.; Collins, J.; Blazar, P.E.; Katz, J.N. Epidemiology of musculoskeletal upper extremity ambulatory surgery in the United States. BMC Musculoskelet Disord 2014, 15, 4. [CrossRef]

- Littlewood, C.; Mazuquin, B.; Moffatt, M.; Bateman, M. Rehabilitation following rotator cuff repair: A survey of current practice. Musculoskeletal Care 2021, 19, 165–171. [CrossRef]

- Cho, C.-H.; Song, K.-S.; Jung, G.H.; Lee, Y.K.; Shin, H.K. Early postoperative outcomes between arthroscopic and mini-open repair for rotator cuff tears. Orthopedics 2012, 35, 1347-52. [CrossRef]

- Nazari, G.; MacDermid, J.C.; Bryant, D.; Dewan, N.; Athwal, G.S. Effects of arthroscopic vs. mini-open rotator cuff repair on function, pain & range of motion. A systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS One 2019, 14(10), e0222953. [CrossRef]

- Cole, B.J.; McCarty, L.P.; Kang, R.W.; Alford, W.; Lewis, P.B.; Hayden, J.K. Arthroscopic rotator cuff repair: prospective functional outcome and repair integrity at minimum 2-year follow-up. J Shoulder Elbow Surg 2007, 16, 579–85. [CrossRef]

- DeFranco, M.J.; Bershadsky, B. Ciccone, J.; Yum, J.K.; Iannotti, J.P. Functional outcome of arthroscopic rotator cuff repairs: a correlation of anatomic and clinical results. J Shoulder Elbow Surg 2007, 16, 759–65. [CrossRef]

- Iannotti, J.P.; Deutsch, A.; Green, A.; Rudicel, S.; Christensen, J.; Marraffino, S.; Rodeo, S. Time to failure after rotator cuff repair: a prospective imaging study. J Bone Joint Surg Am 2013, 95, 965–71. [CrossRef]

- Zhao, J.; Luo, M.; Pan, J.; Liang, G.; Feng, W.; Zeng, L.; Yang, W.; Liu, J. Risk factors affecting rotator cuff retear after arthroscopic repair: a meta-analysis and systematic review. J Shoulder Elbow Surg 2021, 30, 2660–2670. [CrossRef]

- Cuff, D.J.; Pupello, D.R. Prospective randomized study of arthroscopic rotator cuff repair using an early versus delayed postoperative physical therapy protocol. J Shoulder Elbow Surg 2012, 21, 1450–5. [CrossRef]

- Düzgün, I.; Baltacı, G.; Atay, O.A. Comparison of slow and accelerated rehabilitation protocol after arthroscopic rotator cuff repair: pain and functional activity. Acta Orthop Traumatol Turc 2011, 45, 23–33. [CrossRef]

- Arndt, J.; Clavert, P.; Mielcarek, P.; Bouchaib, J.; Meyer, N.; Kempf, J.F.; French Society for Shoulder & Elbow (SOFEC). Immediate passive motion versus immobilization after endoscopic supraspinatus tendon repair: a prospective randomized study. Orthop Traumatol Surg Res 2012, 98, S131-8. [CrossRef]

- Peltzm C.D.; Sarver, J.J.; Dourte, L.M.; Würgler-Hauri, C.C.; Williams, G.R.; Soslowsky, L.J. Exercise following a short immobilization period is detrimental to tendon properties and joint mechanics in a rat rotator cuff injury model. J Orthop Res 2010, 28, 841–5. [CrossRef]

- Huberty, D.P.; Schoolfield, J.D.; Brady, P.C.; Vadala, A.P.; Arrigoni, P.; Burkhart, S.S. Incidence and treatment of postoperative stiffness following arthroscopic rotator cuff repair. Arthroscopy 2009, 25, 880–90. [CrossRef]

- Papalia, R.; Franceschi, F.; Vasta, S.; Gallo, A.; Maffulli, N.; Denaro, V. Shoulder stiffness and rotator cuff repair. Br Med Bull 2012, 104, 163–74. [CrossRef]

- Chen, L.; Peng, K.; Zhang, D.; Peng, J.; Xing, F.; Xiang, Z. Rehabilitation protocol after arthroscopic rotator cuff repair: early versus delayed motion. Int J Clin Exp Med 2015, 8, 8329–38.

- Namdari, S.; Green, A. Range of motion limitation after rotator cuff repair. J Shoulder Elbow Surg 2010, 19, 290–6. [CrossRef]

- Pollock, M.; Fernandes, R.M.; Pieper, D.; Tricco, A.C.; Gates, M.; Gates, A.; Hartling, L. Preferred Reporting Items for Overviews of Reviews (PRIOR): a protocol for development of a reporting guideline for overviews of reviews of healthcare interventions. Syst Rev 2019, 8, 335. [CrossRef]

- Methley, A.M.; Campbell, S.; Chew-Graham, C.; McNally, R.; Cheraghi-Sohi, S. PICO, PICOS and SPIDER: a comparison study of specificity and sensitivity in three search tools for qualitative systematic reviews. BMC Health Serv Res 2014, 14, 579. [CrossRef]

- Shea, B.J.; Reeves, B.C.; Wells, G.; Thuku, M.; Hamel, C.; Moran, J.; Moher, D.; Tugwell, P.; Welch, V.; Kristjansson, E.; Henry, D.A. AMSTAR 2: a critical appraisal tool for systematic reviews that include randomised or non-randomised studies of healthcare interventions, or both. BMJ 2017, 358, 4008. [CrossRef]

- Bandara, U.; An, V.V.G.; Imani, S.; Nandapalan, H.; Sivakumar, B.S. Rehabilitation protocols following rotator cuff repair: a meta-analysis of current evidence. ANZ J Surg 2021, 91, 2773–2779. [CrossRef]

- Houck, D.A.; Kraeutler, M.J.; Schuette, H.B.; McCarty, E.C.; Bravman, J.T. Early Versus Delayed Motion after Rotator Cuff Repair: A Systematic Review of Overlapping Meta-analyses. American Journal of Sports Medicine 2017, 45, 2911–2915. [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; Sun, H.; Luo, X.; Wang, K.; Wu, G.; Zhou, J.; Wang, P.; Sun, X. The clinical effect of rehabilitation following arthroscopic rotator cuff repair: A meta-analysis of early versus delayed passive motion. Medicine (United States); 2018, 97(2), e9625. [CrossRef]

- Littlewood, C.; Bateman, M.; Clark, D.; Selfe, J.; Watkinson, D.; Walton, M.; Funk, L.. Rehabilitation following rotator cuff repair: a systematic review. Shoulder and Elbow 2015, 7, 115–124. [CrossRef]

- Longo, U.G.; Risi Ambrogioni, L.; Berton, A.; Candela, V.; Migliorini, F.; Carnevale, A.; Schena, E.; Nazarian, A.; DeAngelis, J.; Denaro, V. Conservative versus accelerated rehabilitation after rotator cuff repair: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Musculoskelet Disord; 2021, 22(1), 637. [CrossRef]

- Longo, U.G.; Carnevale, A.; Piergentili, I.; Berton, A.; Candela, V.; Schena, E.; Denaro, V. Retear rates after rotator cuff surgery: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Musculoskelet Disord; 2021, 22(1), 749. [CrossRef]

- Matlak, S.; Andrews, A.; Looney, A.; Tepper, K.B. Postoperative Rehabilitation of Rotator Cuff Repair: A Systematic Review. Sports Med Arthrosc Rev 2021, 29, 119–129. [CrossRef]

- Saltzman, B.M.; Zuke, W.A.; Go, B.; Mascarenhas, R.; Verma, N.N.; Cole, B.J.; Romeo, A.A.; Forsythe, B. Does early motion lead to a higher failure rate or better outcomes after arthroscopic rotator cuff repair? A systematic review of overlapping meta-analyses. Journal of Shoulder and Elbow Surgery 2017, 26, 1681–1691. [CrossRef]

- Silveira, A.; Luk, J.; Tan, M.; Kang, S.H.; Sheps, D.M.; Bouliane, M.; Beaupre, L. Move It or Lose It? The Effect of Early Active Movement on Clinical Outcomes Following Rotator Cuff Repair: A Systematic Review with Meta-analysis. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther 2021, 51, 331–344. [CrossRef]

- Thomson, S.; Jukes, C.; Lewis, J.S. Rehabilitation following surgical repair of the rotator cuff: A systematic review. Physiotherapy (United Kingdom) 2016, 102, 20–28. [CrossRef]

- Gallagher, B.P.; Bishop, M.E.; Tjoumakaris, F.P.; Freedman, K.B. Early versus delayed rehabilitation following arthroscopic rotator cuff repair: A systematic review. Phys Sportsmed 2015, 43, 178–87. [CrossRef]

- Chang, K.V.; Hung, C.Y.; Han, D.S.; Chen, W.S.; Wang, T.G.; Chien, K.L. Early versus delayed passive range of motion exercise for arthroscopic rotator cuff repair: A meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. American Journal of Sports Medicine 2015, 43, 1265–1273. [CrossRef]

- Chan, K.; MacDermid, J.C.; Hoppe, D.J.; Ayeni, O.R.; Bhandari, M.; Foote, C.J.; Athwal, G.S. Delayed versus early motion after arthroscopic rotator cuff repair: A meta-analysis. J Shoulder Elbow Surg 2014, 23, 1631–1639. [CrossRef]

- Shen, C.; Tang, Z.H.; Hu, J.Z.; Zou, G.Y.; Xiao, R.C.; Yan, D.X. Does immobilization after arthroscopic rotator cuff repair increase tendon healing? A systematic review and meta-analysis. Archives of Orthopaedic and Trauma Surgery 2014, 134, 1279–1285. [CrossRef]

- Huang,T.S; Wang, S.F.; Lin, J-J. Comparison of Aggressive and Traditional Postoperative Rehabilitation Protocol after Rotator Cuff Repair: A Meta-analysis. J Nov Physiother. 2013, 3, 170. [CrossRef]

- Riboh, J.C.; Garrigues, G.E. Early passive motion versus immobilization after arthroscopic rotator cuff repair. Arthroscopy - Journal of Arthroscopic and Related Surgery 2014, 30, 997–1005. [CrossRef]

- Kluczynski, M.A.; Nayyar, S.; Marzo, J.M.; Bisson, L.J. Early Versus Delayed Passive Range of Motion after Rotator Cuff Repair: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. American Journal of Sports Medicine 2015, 43, 2057–2063. [CrossRef]

- Kluczynski, M.A.; Isenburg, M.M.; Marzo, J.M.; Bisson, L.J. Does Early Versus Delayed Active Range of Motion Affect Rotator Cuff Healing after Surgical Repair? American Journal of Sports Medicine 2016, 44, 785–791. [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).