Submitted:

04 September 2023

Posted:

06 September 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

- a)

- to evaluate maximal cervical isometric strength (forward flexion, extension, lateral flexion) in absolute values using a handheld dynamometer, and to calculate cervical isometric strength in relative values (in relation to body mass and body height), flexion/extension ratios and strength asymmetries between left and right side,

- b)

- to evaluate the range of motion in all directions of movements (forward flexion, extension, lateral flexion, and rotation) using a digital goniometer, and to examine possible differences between left and right sides,

- c)

- to examine the relationship among cervical strength, range of motion, and musculoskeletal pain at the cervical joint,

- d)

- to examine the sex-related effect on cervical strength, range of motion (ROM), and musculoskeletal pain profile in young adults.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants

2.2. Study design

2.3. Testing Procedures

2.3.1. Anthropometric characteristics

2.3.2. Musculoskeletal pains

2.3.3. Cervical Range of Motion - Cervical strength

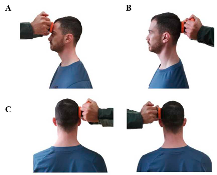

2.3.3.1. Testing position

2.3.3.2. Range of motion measurement

2.3.3.3. Maximal isometric strength measurement

2.4. Statistics

3. Results

3.1. Cervical range of motion

3.2. Cervical isometric strength

3.2.1. Absolute values

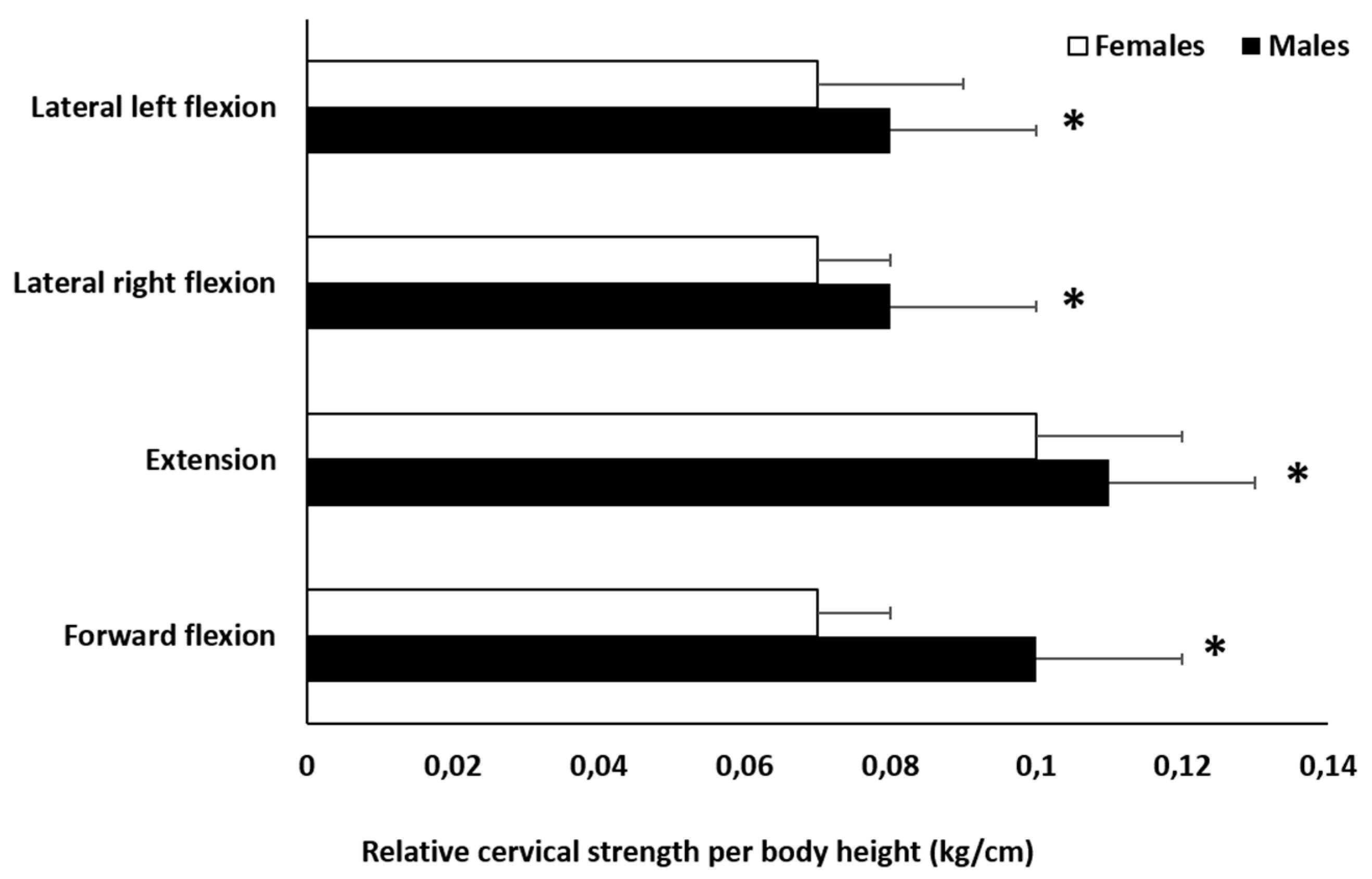

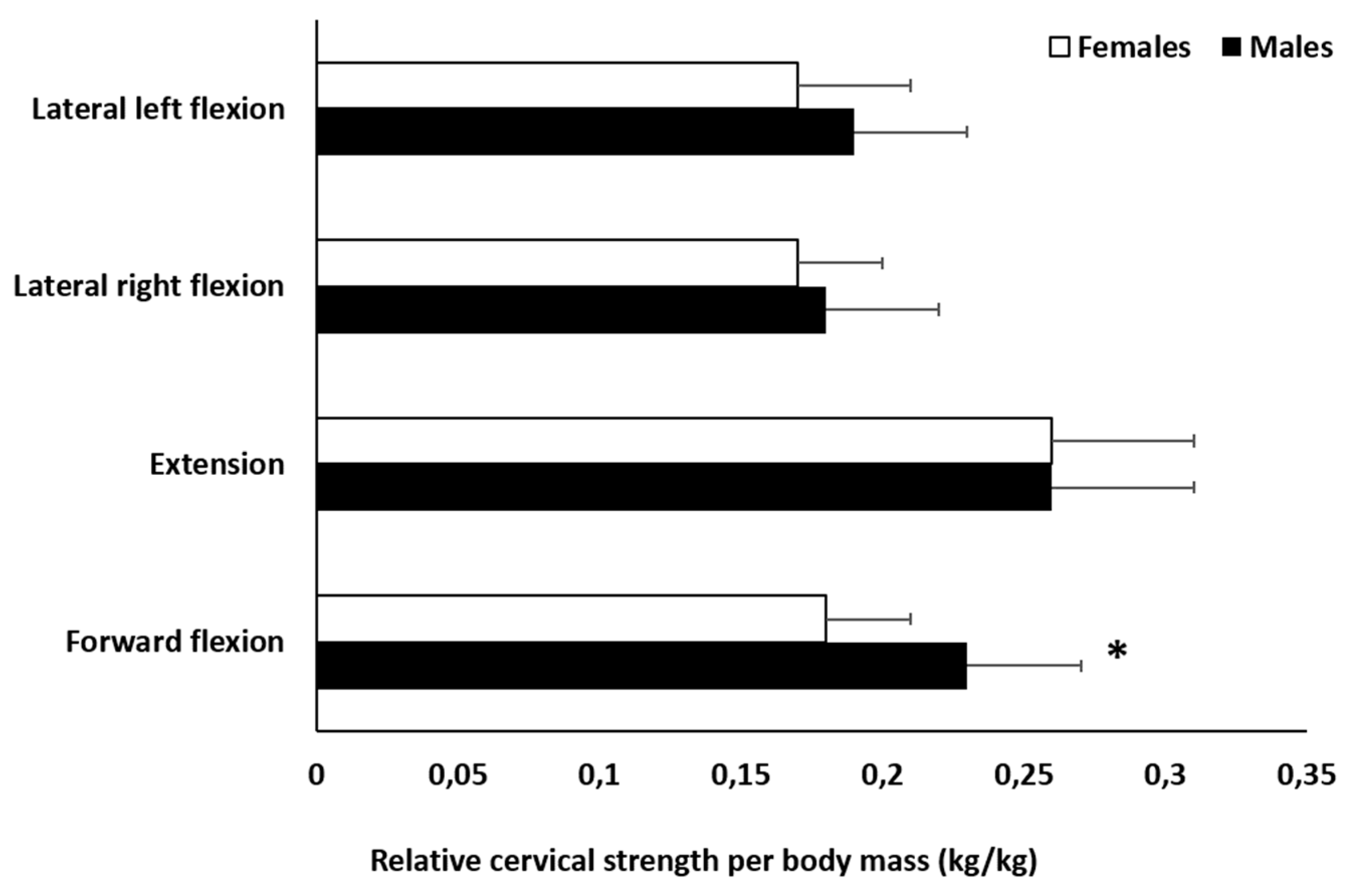

3.2.2. Relative values

3.3. Relationship of anthropometric characteristics with cervical strength and ROM

3.4. Neck pain

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Kaiser JT, Reddy V, Lugo-Pico JG. Anatomy, Head and Neck: Cervical Vertebrae. [Updated 2022 Oct 6]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih. 5397.

- Cimmino MA, Ferrone C, Cutolo M. Epidemiology of chronic musculoskeletal pain. Best Pract Res Clin Rheumatol. 2011;25:173-83. [CrossRef]

- Damasceno, G. M.; Ferreira, A. S.; Nogueira, L. A. C.; Reis, F. J. J.; Andrade, I.C.S.; Meziat-Filho, N. Text neck and neck pain in 18-21-year-old young adults. Eur Spine J. 2018, 27, 1249–1254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Genebra CVDS, Maciel NM, Bento TPF, Simeão SFAP, Vitta A. Prevalence and factors associated with neck pain: a population-based study. Braz J Phys Ther. 2017 Jul-Aug;21(4):274-280. [CrossRef]

- Hansraj, K.K. Assessment of stresses in the cervical spine caused by posture and position of the head. Surg Technol Int. 2014, 25, 277–279. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Kazeminasab S, Nejadghaderi SA, Amiri P, Pourfathi H, Araj-Khodaei M, Sullman MJM, Kolahi AA, Safiri S. Neck pain: global epidemiology, trends and risk factors. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2022 Jan 3;23(1):26. [CrossRef]

- Lee WH, Ko MS. Effect of sleep posture on neck muscle activity. J Phys Ther Sci. 2017 Jun;29(6):1021-1024. [CrossRef]

- Lei JX, Yang PF, Yang AL, Gong YF, Shang P, Yuan XC. Ergonomic Consideration in Pillow Height Determinants and Evaluation. Healthcare (Basel). 2021 Oct 7;9(10):1333. [CrossRef]

- Malchaire JB, Roquelaure Y, Cock N, Piette A, Vergracht S, Chiron H. Musculoskeletal complaints, functional capacity, personality and psychosocial factors. Int Arch Occup Environ Health. 2001 Oct;74(8):549-57. [CrossRef]

- Shahwan BS, D'emeh WM, Yacoub MI. Evaluation of computer workstations ergonomics and its relationship with reported musculoskeletal and visual symptoms among university employees in Jordan. Int J Occup Med Environ Health. 2022 Apr 11;35(2):141-156. [CrossRef]

- Walankar, P.P.; Kemkar, M.; Govekar, A.; Dhanwada, A. Musculoskeletal Pain and Risk Factors Associated with Smartphone Use in University Students. Indian J. Occup. Environ. Med. 2021, 25(4), 220–224. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Algarni AD, Al-Saran Y, Al-Moawi A, Bin Dous A, Al-Ahaideb A, Kachanathu SJ. The Prevalence of and Factors Associated with Neck, Shoulder, and Low-Back Pains among Medical Students at University Hospitals in Central Saudi Arabia. Pain Res Treat. 2017;2017:1235706. [CrossRef]

- Fejer R, Kyvik KO, Hartvigsen J. The prevalence of neck pain in the world population: a systematic critical review of the literature. Eur Spine J. 2006 Jun;15(6):834-48. [CrossRef]

- Karatrantou K, Gerodimos V. A comprehensive wellness profile in sedentary office employees: Health, musculoskeletal pains, functional capacity, and physical fitness indices. Work. 2023;74(4):1481-1489. [CrossRef]

- Todd A, McNamara CL, Balaj M, Huijts T, Akhter N, Thomson K, Kasim A, Eikemo TA, Bambra C. The European epidemic: Pain prevalence and socioeconomic inequalities in pain across 19 European countries. Eur J Pain. 2019 Sep;23(8):1425-1436. [CrossRef]

- Daffner, S.D.; Hilibrand, A.S.; Hanscom, B.S.; Brislin, B.T. , Vaccaro, A.R., Albert, T.J. Impact of neck and arm pain on overall health status. J. Impact of neck and arm pain on overall health status. Spine. 2003, 28(17), 2030–5. [Google Scholar]

- IJzelenberg, W.; Burdorf, A. Risk factors for musculoskeletal symptoms and ensuing health care use and sick leave. Spine. 2005, 30(13), 1550–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eagle, S. R. , Nagai, T., Morgan, P., Hendershot, R., & Sell, T. C. Naval Special Warfare (NSW) crewmen demonstrate diminished cervical strength and range of motion compared to NSW students. Work.

- De Loose, V.; Van den Oord, M.; Burnotte, F.; Van Tiggelen, D.; Stevens, V.; Cagnie, B.; Danneels, L.; Witvrouw, E. ; Functional assessment of the cervical spine in F-16 pilots with and without neck pain. Aviat Space Environ Med. 2009, 80(5), 477–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stenneberg, M.S.; Rood, M.; de Bie, R.; Schmitt, M.A.; Cattrysse, E.; Scholten-Peeters, G. G. To What Degree Does Active Cervical Range of Motion Differ Between Patients With Neck Pain, Patients With Whiplash, and Those Without Neck Pain? A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2017, 98(7), 1407–1434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alpayci M, Şenköy E, Delen V, Şah V, Yazmalar L, Erden M, Toprak M, Kaplan Ş. Decreased neck muscle strength in patients with the loss of cervical lordosis. Clin Biomech (Bristol, Avon). 2016 Mar;33:98-102. [CrossRef]

- Shahidi B, Johnson CL, Curran-Everett D, Maluf KS. Reliability and group differences in quantitative cervicothoracic measures among individuals with and without chronic neck pain. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2012 Oct 31;13:215. [CrossRef]

- Vernon HT, Aker P, Aramenko M, Battershill D, Alepin A, Penner T. Evaluation of neck muscle strength with a modified sphygmomanometer dynamometer: reliability and validity. J Manipulative Physiol Ther. 1992 Jul-Aug;15(6):343-9. [PubMed]

- Catenaccio E, Mu W, Kaplan A, Fleysher R, Kim N, Bachrach T, Zughaft Sears M, Jaspan O, Caccese J, Kim M, Wagshul M, Stewart WF, Lipton RB, Lipton ML. Characterization of Neck Strength in Healthy Young Adults. PM R. 2017 Sep;9(9):884-891. [CrossRef]

- Chiu TT, Lam TH, Hedley AJ. Maximal isometric muscle strength of the cervical spine in healthy volunteers. Clin Rehabil. 2002 Nov;16(7):772-9. [CrossRef]

- Garcés GL, Medina D, Milutinovic L, Garavote P, Guerado E. Normative database of isometric cervical strength in a healthy population. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2002 Mar;34(3):464-70. [CrossRef]

- Hamilton DF, Gatherer D, Jenkins PJ, Maclean JG, Hutchison JD, Nutton RW, Simpson AH. Age-related differences in the neck strength of adolescent rugby players: A cross-sectional cohort study of Scottish schoolchildren. Bone Joint Res. 2012 Jul 1;1(7):152-7. [CrossRef]

- Nutt S, McKay MJ, Gillies L, Peek K. Neck strength and concussion prevalence in football and rugby athletes. J Sci Med Sport. 2022 Aug;25(8):632-638. [CrossRef]

- Vasavada, A.N.; Danaraj, J.; Siegmund, G.P. ; Head and neck anthropometry, vertebral geometry and neck strength in height-matched men and women. J Biomech. 2008, 41(1), 114–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jordan A, Mehlsen J, Bülow PM, Ostergaard K, Danneskiold-Samsøe B. Maximal isometric strength of the cervical musculature in 100 healthy volunteers. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 1999 Jul 1;24(13):1343-8. [CrossRef]

- McBride L, James RS, Alsop S, Oxford SW. Intra and Inter-Rater Reliability of a Novel Isometric Test of Neck Strength. Sports (Basel). 2022 Dec 21;11(1):2. [CrossRef]

- Peolsson A, Oberg B, Hedlund R. Intra- and inter-tester reliability and reference values for isometric neck strength. Physiother Res Int. 2001;6(1):15-26. [CrossRef]

- Salo PK, Ylinen JJ, Mälkiä EA, Kautiainen H, Häkkinen AH. Isometric strength of the cervical flexor, extensor, and rotator muscles in 220 healthy females aged 20 to 59 years. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther. 2006 Jul;36(7):495-502. [CrossRef]

- Valkeinen H, Ylinen J, Mälkiä E, Alen M, Häkkinen K. Maximal force, force/time and activation/coactivation characteristics of the neck muscles in extension and flexion in healthy men and women at different ages. Eur J Appl Physiol. 2002 Dec;88(3):247-54. [CrossRef]

- Versteegh T, Beaudet D, Greenbaum M, Hellyer L, Tritton A, Walton D. Evaluating the reliability of a novel neck-strength assessment protocol for healthy adults using self-generated resistance with a hand-held dynamometer. Physiother Can. 2015 Winter;67(1):58-64. [CrossRef]

- Elliott J, Heron N, Versteegh T, Gilchrist IA, Webb M, Archbold P, Hart ND, Peek K. Injury Reduction Programs for Reducing the Incidence of Sport-Related Head and Neck Injuries Including Concussion: A Systematic Review. Sports Med. 2021 Nov;51(11):2373-2388. [CrossRef]

- Collins CL, Fletcher EN, Fields SK, Kluchurosky L, Rohrkemper MK, Comstock RD, Cantu RC. Neck strength: a protective factor reducing risk for concussion in high school sports. J Prim Prev. 2014 Oct;35(5):309-19. [CrossRef]

- Gillies L, McKay M, Kertanegara S, Huertas N, Nutt S, Peek K. The implementation of a neck strengthening exercise program in elite rugby union: A team case study over one season. Phys Ther Sport. 2022 May;55:248-255. [CrossRef]

- Garrett JM, Mastrorocco M, Peek K, van den Hoek DJ, McGuckian TB. The Relationship Between Neck Strength and Sports-Related Concussion in Team Sports: A Systematic Review With Meta-analysis. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther. 2023 Oct;0(10):1-9. [CrossRef]

- Pan F, Arshad R, Zander T, Reitmaier S, Schroll A, Schmidt H. The effect of age and sex on the cervical range of motion - A systematic review and meta-analysis. J Biomech. 2018 Jun 25;75:13-27. [CrossRef]

- Thoomes-de Graaf, M.; Thoomes, E.; Fernández-de-Las-Peñas, C.; Plaza-Manzano, G.; Cleland, J.A. Normative values of cervical range of motion for both children and adults: A systematic review. Musculoskelet Sci Pract. 2020, 49, 102–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Williams MA, McCarthy CJ, Chorti A, Cooke MW, Gates S. A systematic review of reliability and validity studies of methods for measuring active and passive cervical range of motion. J Manipulative Physiol Ther. 2010 Feb;33(2):138-55. [CrossRef]

- Dvorak J, Antinnes JA, Panjabi M, Loustalot D, Bonomo M. Age and gender related normal motion of the cervical spine. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 1992 Oct;17(10 Suppl):S393-8. [CrossRef]

- Zárate-Tejero CA, Rodríguez-Rubio PR, Brandt L, Krauss J, Hernández-Secorún M, Lucha-López O, Hidalgo-García C. Association between Age, Sex and Cervical Spine Sagittal Plane Motion: A Descriptive and Correlational Study in Healthy Volunteers. Life (Basel). 2023 Feb 7;13(2):461. [CrossRef]

- Ferguson, B. ACSM’s Guidelines for Exercise Testing and Prescription, 9th ed. J Can Chiropr Assoc. 2014, 58(3), 328. [Google Scholar]

- Jannatbi, L.I.; Nigudgi, S.R.; Shrinivas, R. Assessment of musculoskeletal disorders by standardized Nordic questionnaire among computer engineering students and teaching staff of Gulbarga city. Int. J. Community Med. Public Health 2016, 3, 668–674. [Google Scholar]

- Bayattork M, Sköld MB, Sundstrup E, Andersen LL. Exercise interventions to improve postural malalignments in head, neck, and trunk among adolescents, adults, and older people: systematic review of randomized controlled trials. J Exerc Rehabil. 2020 Feb 26;16(1):36-48. [CrossRef]

- Häkkinen K, Pakarinen A. Muscle strength and serum testosterone, cortisol and SHBG concentrations in middle-aged and elderly men and women. Acta Physiol Scand. 1993 Jun;148(2):199-207. [CrossRef]

- Ryushi T, Hakkinen K, Kauhanen H, Komi PV. Muscle fiber characteristics, muscle cross-sectional area and force production in strength athletes, physically active males and females. Scand J Sports Sci. 1988; 10:7-15.

- Olivier PE, Du Toit DE. Isokinetic neck strength profile of senior elite rugby union players. J Sci Med Sport. 2008 Apr;11(2):96-105. [CrossRef]

- Gourie-Devi M, Nalini A, Sandhya S. Early or late appearance of "dropped head syndrome" in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2003 May;74(5):683-6. [CrossRef]

- Kyllönen ES, Heikkinen JE, Väänänen HK, Kurttila-Matero E, Wilen-Rosenqvist G, Lankinen KS, Vanharanta JH. Influence of estrogen-progestin replacement therapy and exercise on lumbar spine mobility and low back symptoms in a healthy early postmenopausal female population: a 2-year randomized controlled trial. Eur Spine J. 1998;7(5):381-6. [CrossRef]

- Cunha-Henriques S, Costa-Paiva L, Pinto-Neto AM, Fonsechi-Carvesan G, Nanni L, Morais SS. Postmenopausal women with osteoporosis and musculoskeletal status: a comparative cross-sectional study. J Clin Med Res. 2011 Jul 26;3(4):168-76. [CrossRef]

- Jahre H, Grotle M, Smedbråten K, Dunn KM, Øiestad BE. Risk factors for non-specific neck pain in young adults. A systematic review. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2020 Jun 9;21(1):366. [CrossRef]

- Staudte HW, Duhr N. Age- and sex-dependent force related function of the cervical spine. Eur Spine J. 1994;3:155-161.

- Hurwitz EL, Randhawa K, Yu H, Côté P, Haldeman S. The Global Spine Care Initiative: a summary of the global burden of low back and neck pain studies. Eur Spine J. 2018;27:796-801. [CrossRef]

- Schulenberg J, Schoon I. The Transition to Adulthood across Time and Space: Overview of Special Section. Longit Life Course Stud. 2012;3:164-172. [CrossRef]

- Schoon I, Chen M, Kneale D, Jager J. Becoming adults in Britain: lifestyles and wellbeing in times of social change. J Longitudinal Life Course Stud. 2012;3:17.

- Dunn, KM. Extending conceptual frameworks: life course epidemiology for the study of back pain. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2010 Feb 2;11:23. [CrossRef]

| Variables | Males (n=30) | Females (n=30) |

|---|---|---|

| Age (years old) | 21.95 ± 1.1 | 21.1 ± 1.2 |

| Body height (cm) | 178.5 ± 7.4 | 166.3 ± 6.3* |

| Body mass (kg) | 78.25 ± 14.4 | 64.6 ± 10.98* |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 24.4 ± 3.1 | 23.4 ± 3.99 |

| Movement | Males (n = 30) | Females (n = 30) |

|---|---|---|

| Forward flexion (ο) | 71.42 ± 10.34 | 69.81 ± 13.45 |

| Extension (ο) | 80.38 ± 12.48 | 94.28 ± 14.16* |

| Right lateral flexion (ο) | 47.76 ± 8.05 | 53.39 ± 10.71* |

| Left lateral flexion (ο) | 47.89 ± 8.69 | 53.87 ± 8.5* |

| Right lateral rotation (ο) | 80.83 ± 9.26 | 83.16 ± 9.34 |

| Left lateral rotation (ο) | 82.34 ± 8.44 | 85.56 ± 8.36 |

| Movement | Males (n = 30) | Females (n = 30) |

|---|---|---|

| Forward flexion (kg) | 17.92 ± 4.25* | 11.17 ± 2.10 |

| Extension (kg) | 20.45 ± 4.70* | 16.27 ± 3.17 |

| Right lateral flexion (kg) | 14.33 ± 3.89* | 10.93 ± 2.42 |

| Left lateral flexion (kg) | 14.52 ± 3.62* | 11.13 ± 2.85 |

| Flexion / Extension ratio (%) | 89.17 ± 17.51* | 69.75 ± 12.18 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).