1. Introduction

The increased life expectancy and aging of patients with chronic liver disease (CLD) entails a raise in the need for invasive procedures and surgeries in increasingly complex patients due to the addition of extrahepatic comorbidities. Patients with advanced chronic liver disease (ACLD) or cirrhosis undergoing surgery have an increased risk of morbidity and mortality in contrast to the general population[

1].

Classically, the mortality risk after surgery has been related to liver function. High Child-Turcotte-Pugh (CTP) score values have consistently been associated with complications and mortality in operated patients[2-5]. The Model for End-Stage Liver Disease (MELD) incorporates renal function and has been linearly correlated to postoperative mortality[

6]. Through the years there have been attempts to improve these predictions by incorporating variables related to comorbidity. However, the Charlson Comorbidity Index (CCI)[

7], and the American Society of Anesthesiologists physical status classification system (ASA)[

8], were designed in non-cirrhotic patients. In 2013, Jepsen et al. developed the Cirrhosis Comorbidity Score (CirCom)[

9], a semi-quantitative scale that evaluates the long-term and non-surgically related mortality risk added to cirrhosis by other comorbidities. Nevertheless, prediction models designed to predict surgical risk are preferable. In the general population, one of the most used calculators is the National Surgery Quality Improvement Program (NSQIP)[

10]. The NSQIP includes 20 variables but only one (ascites in the previous 30 days) is related to ACLD. The NSQIP evaluates postoperative morbidities and 30-day mortality but the prevalence of patients with cirrhosis was unknown.

Only two models have been developed to evaluate surgical risk in patients with ACLD, the Post-operative Mayo Risk Score (MRS)[

11] and the Veterans Outcomes and Costs Associated with Liver Disease (VOCAL)-Penn Cirrhosis Surgical Risk Score[

12,

13]. The MRS included age, ASA score, MELD, and etiology of cirrhosis as independent predictors of surgical mortality at short- (7, 30, and 90 days) and long-(1 and 5 years) term. Nevertheless, it did not include the type of surgery[

11]. The VOCAL-Penn is the most recent and complete surgical risk score to evaluate patients with cirrhosis, including variables such as age, liver function (bilirubin and albumin levels), portal hypertension (platelet count), etiology of cirrhosis (non-alcoholic fatty liver disease), comorbidity (obesity and ASA score), and the type and emergency of surgery[

12,

13]. Although the VOCAL-Penn improves mortality risk prediction over previous scores (CTP, MELD, MRS), it has not been validated in European cohorts.

Therefore, the primary aim of our study was to compare surgical risk mortality prediction of the existing risk scores (CTP, MELD-Na, MRS, NSQIP, and VOCAL-Penn) in a European cohort of patients with ACLD. As secondary aims, we described comorbidity, complications after surgery, and variables related to mortality in our cohort.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design and Population

This is a retrospective, observational, single-center study (Hospital del Mar) of patients with ACLD who underwent major surgery between January 2010 and December 2019. Patients were identified from the hospital registry by cross-matching the International Classification of Diseases (ICD) related to CLD, cirrhosis, and its complications [ICD-9 571, 572.2, 572.3, 572.4, 572.5, 573.5, 070.2, 070.3, 070.44, 070.6, 070.7, and ICD-10 K70, K72.10/K72.11, K73, K74, K75.4, K75.9, K76.0, K76.1, K76.6, K76.7, K76.81, B19.0] and the Common Procedure Terminology (CPT) codes of all surgical procedures.

The hospital registry of patients with CLD was revised by a medical student (A.S.) supervised by the multidisciplinary team. The comorbidities were reviewed by a pharmacist (E.C.). Surgical procedures were scrutinized by an expert surgeon (A.P.) and anesthesiologist (J.A). Two expert hepatologists (L.C. and J.A.C) revised all the liver-related data and the ACLD categorization. Only patients with the inclusion criteria for ACLD who underwent major surgeries counted in the VOCAL-Penn[

12] were included.

The ACLD was defined by the presence of any chronic liver disease and at least one of the following criteria: 1) Thrombocytopenia with platelets <150.000/uL and splenomegaly [

14]; 2) AST-to-Platelet Ratio Index (APRI) >2 [

15]; 3) nodular liver edge by ultrasound[

16]; 4) transient elastography (TE) >15 kPa[

17] and/or 5) signs of portal hypertension by upper digestive endoscopy (UDE)[

18].

The major surgeries were classified according to 1) the localization: abdominal (laparoscopic or laparotomy), abdominal wall, vascular, orthopedic, and thoracic/cardiac, and 2) the emergency indication (urgent and elective). Emergent surgery was considered if it had been performed in the first 24 hours after the diagnosis of the surgical pathology. Early reoperation was defined as a second surgery related to a complication of the initial surgery and performed on the same admission or in the first postoperative month.

We excluded patients with 1) ASA-V because of its intrinsic high mortality risk; 2) early reoperations, and 3) surgeries not included in the VOCAL-Penn (localized in the central nervous system, hepatic surgeries, or those with accepted low risk).

The study protocol was approved by the Ethical Committee of our institution ‘Comitè Ètic d'Investigació Clínica -Parc de Salut Mar’, study reference 2020/9640, by the ethical guidelines of the 1975 Declaration of Helsinki.

2.2. Data Collection, Mortality Estimation Risks, and Definitions

Sociodemographic data (age, gender), the dates of admission, surgery and hospital discharge, and hospital stay were obtained through the hospital registry. Information about ACLD (etiology, decompensation, presence of ascites 30 days previous to surgery, TE, and UDE at an interval of 2 years) was retrospectively obtained from medical records. Laboratory data on liver function (bilirubin, albumin, prothrombin time, INR, platelets) and renal function (urea, creatinine, sodium) were collected at an interval of fewer than 6 months.

After surgery, we evaluated renal function (maximum creatinine and creatinine at discharge), and data regarding bacterial infection (type and severity), ACLD decompensation (ascites, encephalopathy, portal hypertension bleeding), and hemorrhage (type and need for transfusion of blood products) during admission. The development of acute kidney injury (AKI) was characterized by Kidney Disease Improving Global Guidelines[

21]. We defined severe bacterial infection if it required intensive care unit (ICU) admission for organ support (vasoactive drugs, mechanical ventilation, renal replacement therapy). Multidrug-resistant microorganism (MDRM) was identified if it presented resistance to ≥ 2 groups of antibiotics. We also recorded worse renal function, and the presence of bacterial infection, ACLD decompensation, and/or hemorrhage from discharge to 90 days after surgery. The date and cause of death were compiled, and we calculated whether it had occurred within 30 days, 90 days, or 180 days from surgery.

2.3. Statistical Analysis

Categorical variables were described as frequencies and percentages. Continuous variables were detailed as medians and interquartile ranges (IQR). We compared the baseline characteristics of our cohort (H. Mar) to those reported by the VOCAL-Penn cohort by comparing proportions on categorical variables and medians on continuous variables with the Wilcoxon signed-rank test.

We assessed variables related to 90-day mortality in our cohort. Variables were compared between groups using χ2 for categorical variables, and the Mann-Whitney U test for continuous variables. Covariates that were significant with p<0.05 in univariate analysis were included in multivariate forward stepwise Cox regression models. A maximum of one variable for every 10 events was entered into the model. Kaplan-Meier analysis and Log-Rank test were used to gauge the association between variables of interest and observed postoperative mortality.

Surgical risk scores (CTP, MELD-Na, MRS, NSQIP, and VOCAL-Penn) were evaluated using tools of discrimination and calibration. Discrimination or predictive capacity for mortality of each score was depicted graphically according to their median (IQR) mortality rate in patients with the presence or absence of observed mortality after surgery at 30 days (by MRS, NSQIP, and VOCAL-Penn), at 90 days (by MRS and VOCAL-Penn), and 180 days (by VOCAL-Penn). The predictive capacity of the scores was estimated using the Receiver Operating Characteristic (ROC) curves and concordance statistics (c-statistics) with 95% confidence intervals (CIs). The accuracy was considered excellent if c-statistic >0.9, and good for values between 0.7 and 0.9[

22]. Moreover, the c-statistic (95%CI) of each score was compared with VOCAL-Penn (as the reference) according to the Hanley and MacNeil test [

23] to identify those with the highest diagnostic accuracy. Calibration or goodness of fit to the observed mortality was evaluated with a graph of observed events rate against the predicted mortality probabilities of each score. The overall performance of the scores was studied with the Brier score, which is a global measure that incorporates discrimination and calibration information. Its value can range from 0 to 1. The lower the value, the better the prediction.

All the analyses were 2-tailed. Statistical analysis and graphs were performed using IBM SPSS statistics V 24.0 (IBM Corp) and STATA V15.1 (StataCorp).

3. Results

3.1. Study Population and Comparison with VOCAL-Penn Cohort

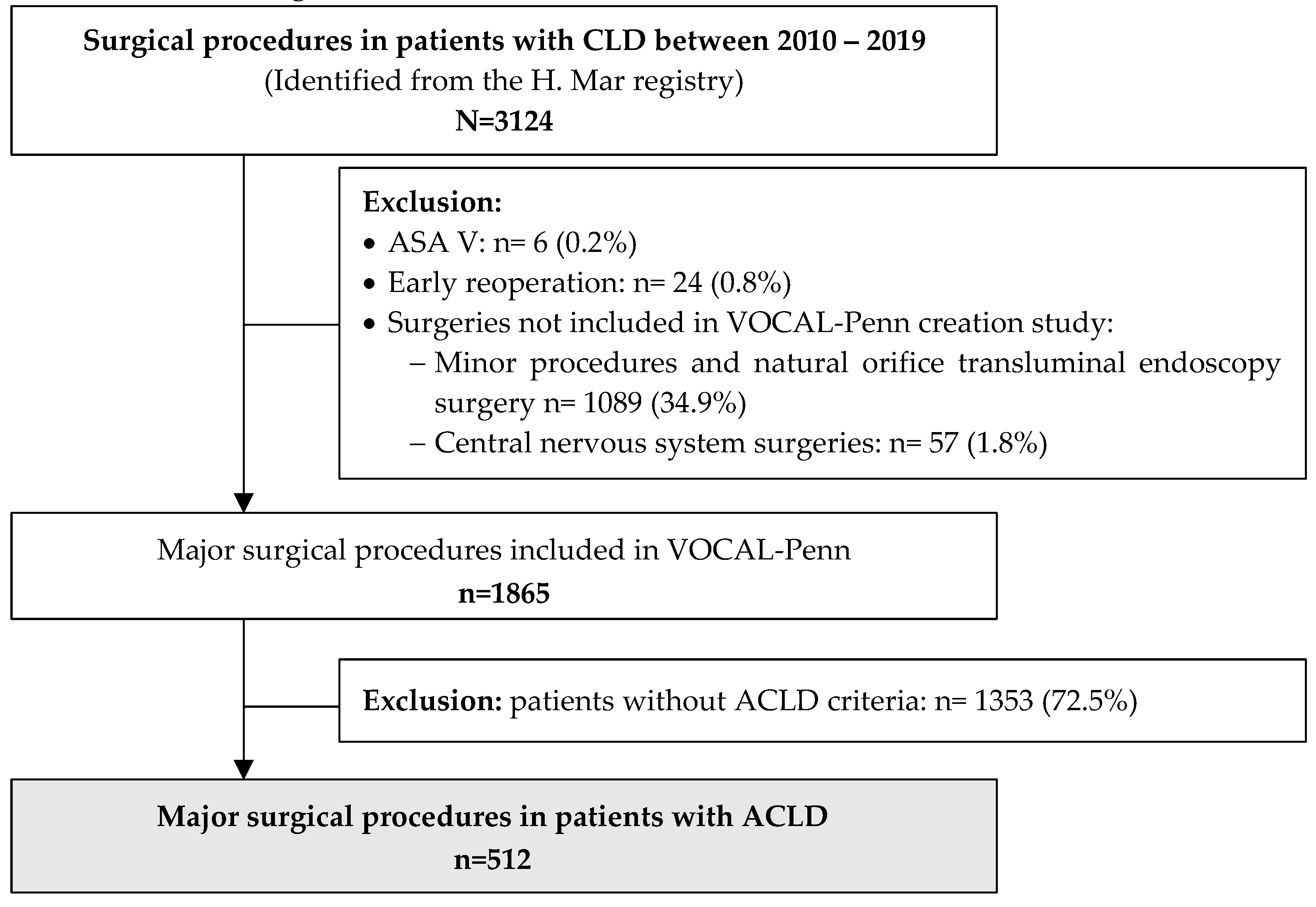

All surgical procedures in patients with CLD between January 2010 and December 2019 (N=3124) were initially evaluated. Only major surgical procedures included in VOCAL-Penn (n=1865) were considered. Patients without ACLD (n=1353) were excluded. Therefore, after a profound revision of the hospital registry, 512 patients with ACLD who underwent a major surgical procedure were included. The flowchart of the study population is shown in

Figure 1.

Demographic data, information about the ACLD, and comorbidities of included patients (n=512) are summarized in

Table 1. The median (IQR) age was 66 years (57-75) and 332 (64.8%) were male. Etiologies of ACLD were alcohol (45.3%), viral (31.4%), and metabolic-associated fatty liver disease (MAFLD)(10.8%). Endoscopic signs of portal hypertension were present in 58.5%. Most of the patients had good liver function before surgery: 70.7% were CTP A and the median (IQR) MELD-Na was 12 (8-16), while 29.3% had a history of a previous decompensation (15.2% with ascites 30 days before surgery). The 40.2% of surgeries were urgent, and the predominant localization was abdominal (42.6%), orthopedic (25.0%), and abdominal wall (21.7%). Urgent surgeries were performed more frequently in patients with CTP B/C (60.2%) than in CTP A (29.6%)(p<0.001), and in those with ascites (70.5%) than in those without (34.8%)(p<0.001).

Several disparities were detected when comparing H. Mar and VOCAL-Penn cohorts (

Table 1). The VOCAL-Penn cohort had a clear predominance of males (97.2%) compared to H. Mar (64.8%)(p<0.001) and included patients with better liver function evidenced by the MELD, MELD-Na, and CTP scales (p<0.001 in all variables). However, the proportion of ascites before surgery was similar between both cohorts (H. Mar 15.2% vs. VOCAL-Penn 13.2%; p=0.174). The predominant etiologies of ACLD in the H. Mar were alcohol and hepatitis C, while in the VOCAL-Penn cohort were alcohol and its combination with hepatitis C. The presence of metabolic and cardiovascular comorbidities such as diabetes, obesity, and hypertension was significantly higher in the VOCAL-Penn cohort, as well as the rate of previous decompensation (H. Mar 29.3% vs. VOCAL-Penn 43.8%; p<0.001). Therefore, the prevalence of patients with ASA-IV was higher in the VOCAL-Penn cohort (54.4%) than in H. Mar (24.2%)(p<0.001). Emergent and abdominal (laparoscopic and laparotomy) surgeries were more frequent in the H. Mar cohort, while abdominal wall, vascular, and thoracic/cardiac surgeries were predominant in VOCAL-Penn Cohort.

3.2. Clinical Events and Mortality after Surgery

During hospitalization 38 (7.4%) patients died. Liver decompensation was observed in 149 (29.1%) patients: ascites in 141 (27.5%), encephalopathy in 40 (7.8%), and hemorrhage due to portal hypertension in 7 (1.4%). Bacterial infections were observed in 200 (39.1%) patients. The first infection was spontaneous bacterial peritonitis (SBP) in 57 (28.5%), urinary infection in 42 (21.0%), other intra-abdominal infections in 35 (17.5%), and respiratory infection in 27 (13.5%). Seventy-nine (39.5%) were produced by MDRM and 47 (23.5%) developed a severe bacterial infection: 19 (40.4%) SBP, 13 (27.7%) respiratory infections, 10 (21.3%) bacteremia, and 5 (10.6%) other intra-abdominal infections. Hemorrhage was presented in 73 (14.3%) patients: non-digestive in 46 (63.0%), digestive non-portal hypertension in 20 (27.4%), and due to portal hypertension in 7 (9.6%). Transfusion of at least 2 red blood cell packs was required in 56 (76.7%) patients with hemorrhage. Renal function was evaluated in 427 patients and 124 (29.0%) developed AKI during admission: 25 (20.2%) grade 1A, 43 (34.7%) grade 1B, 25 (20.2%) grade II, and 31 (25.0%) grade III. Ascites was more frequent in patients with AKI (55.6%) compared to those without (22.4%)(p<0.001).

After discharge and during the first 90 days of follow-up from surgery 12 (2.3%) patients died and 135 (26.4%) had ascites: clinical in 68 (14.4%), and radiological in 67 (14.2%). Seventy-eight (16.6%) patients showed some bacterial infection: urinary in 24 (30.8%), respiratory in 15 (19.2%), and cellulitis or skin infection in 15 (19.2%). Thirty-two (6.8%) patients presented bleeding, mainly of soft tissue. Renal function was evaluated in 349 patients and AKI was observed in 34 (9.7%). Therefore 158 (45.2%) patients presented AKI during the first 90 days after surgery.

The mortality rate at 30, 90, and 180 days from surgery was 6.4% (n=33), 9.8% (n=50), and 13.7% (n=70), respectively. Liver decompensation, sepsis, and cardiovascular events were the most frequent causes of death at the three-time points. Mortality rates by liver decompensation, sepsis, and cardiovascular event at 90 days were 18 (36.0%), 11 (22.0%), and 8 (16.0%), respectively. However, as we got away from the date of surgery, patients died less from liver decompensation and more from cancer or unknown causes.

3.3. Variables Related to Mortality after Surgery

Univariate analysis of variables related to 90-day mortality is depicted in

Table 2. In our cohort, the etiology of the ACLD did not impact on mortality. Neither obesity nor other metabolic comorbidities were useful in discriminating the risk of mortality. Age and liver-related variables such as bilirubin, INR, albumin, platelets, and ascites 30 days before surgery were associated with 30-day, 90-day, and 180-day mortality. Baseline creatinine level was related to 30 and 90-day mortality but not to 180-day mortality. Chronic kidney disease was associated only with 30-day mortality but not with 90 or 180-day mortality. Moreover, the CirCom score was not useful for predicting mortality (Log-Rank

30D= 0.133; Log-Rank

90D= 0.531; and Log-Rank

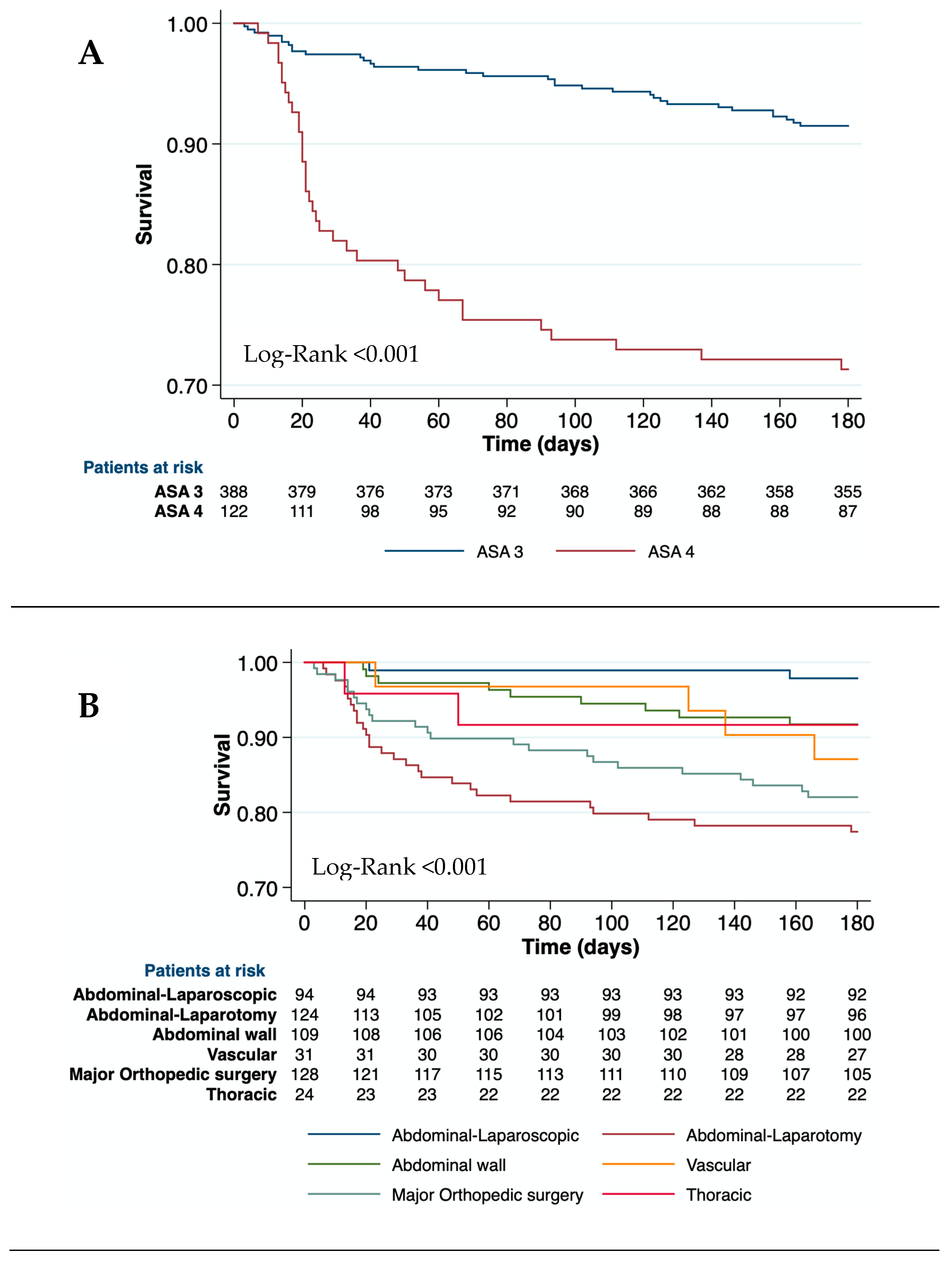

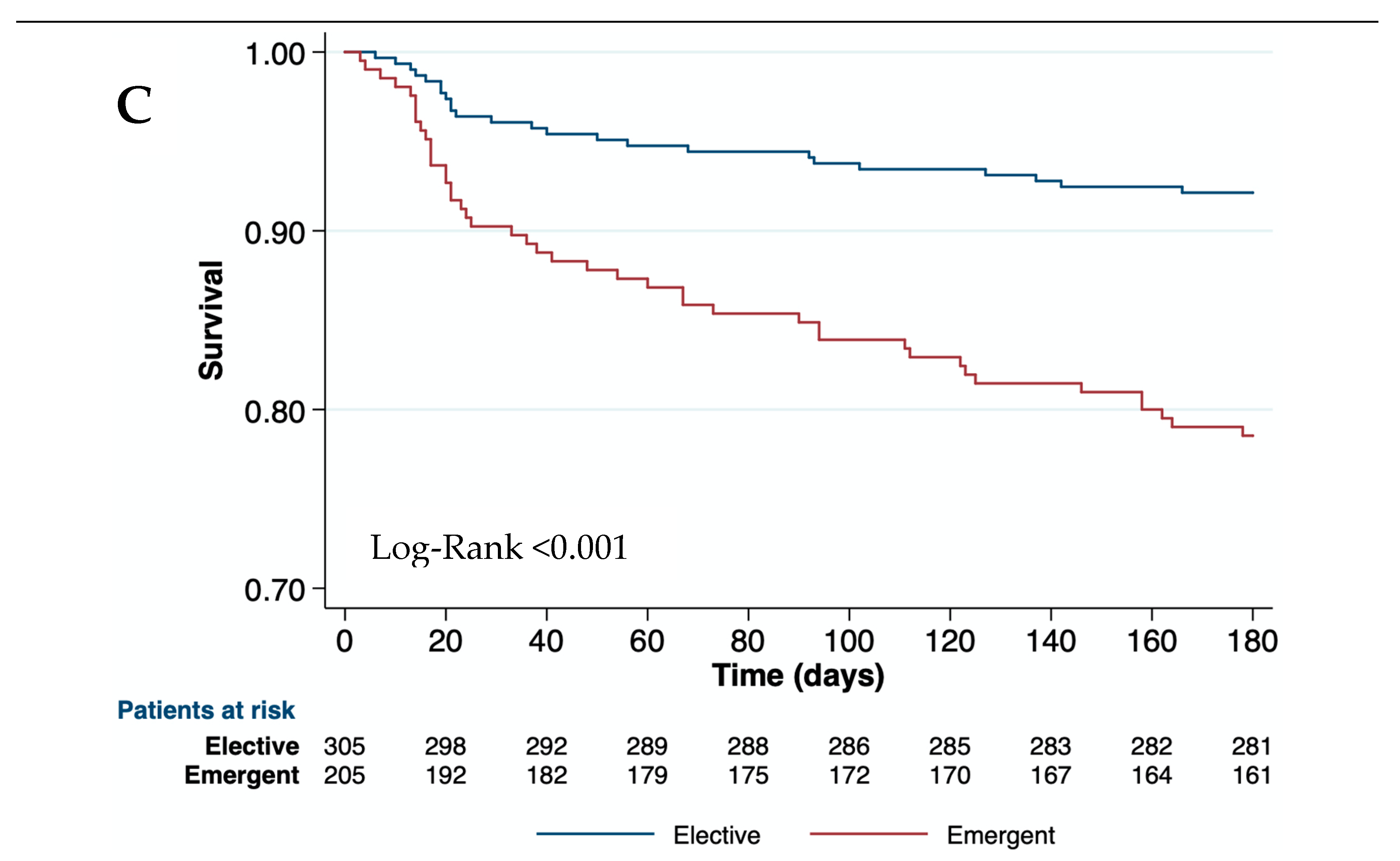

180D= 0.566). However, patients with ASA-IV showed higher postoperative mortality than ASA-III at all-time points (

Table 2 and

Figure 2a). The type and the emergency of surgery were associated with postoperative mortality (Log-Rank< 0.01 at all-time points). Therefore, open abdominal surgeries and major orthopedic surgeries had the highest mortality risk at 90 days (46.0% and 30.0%, respectively) (

Table 2, and

Figure 2b,c). Clinical events during hospitalization such as AKI, bacterial infections, and hemorrhage were also related to mortality at all-time points (p<0.001) (

Table 2).

Variables associated with 90-day postoperative mortality in the multivariate Cox regression analysis are depicted in

Table 3. The variables were grouped into four categories: 1) age and comorbidity, 2) liver function, 3) type and urgency of surgery, and 4) clinical events during admission. In the first group, age and ASA-IV were related to mortality at all three-time points. Neither chronic kidney disease nor baseline creatinine were independently associated with mortality. Regarding liver function, bilirubin and albumin were associated with mortality at all-time points, and INR at 90 days. No differences in the model were found when choosing ascites or platelet levels. In the third category, patients undergoing urgent surgery showed between 2-3 times higher risk of mortality, and those undergoing open abdominal surgery or major orthopedic surgery developed a higher mortality risk at all three-time points. Finally, patients with AKI or bacterial infections during admission showed a higher risk of mortality during the first 90 days after surgery.

3.4. Diagnostic Accuracy and Calibration of Surgical Risk Scales

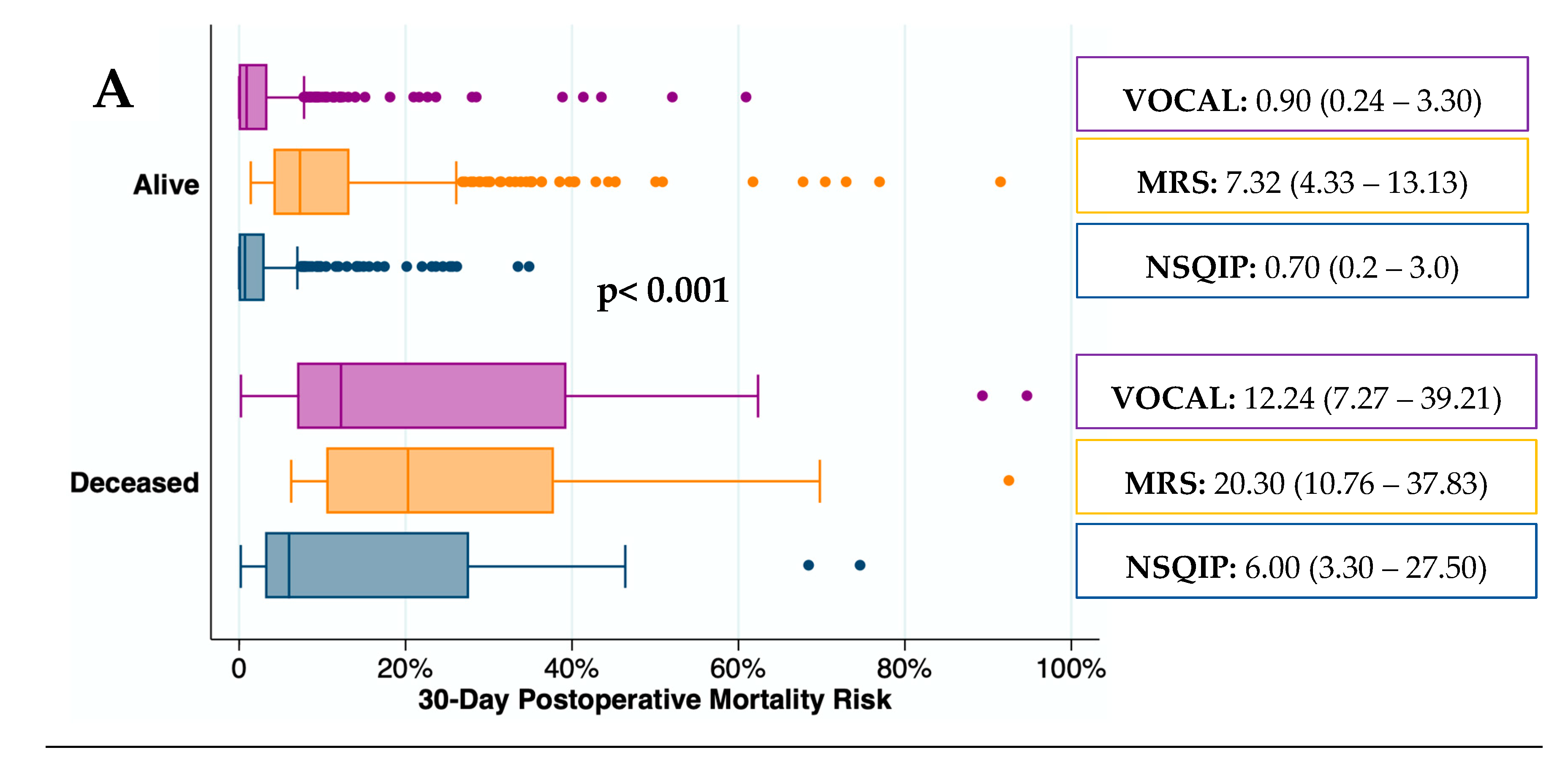

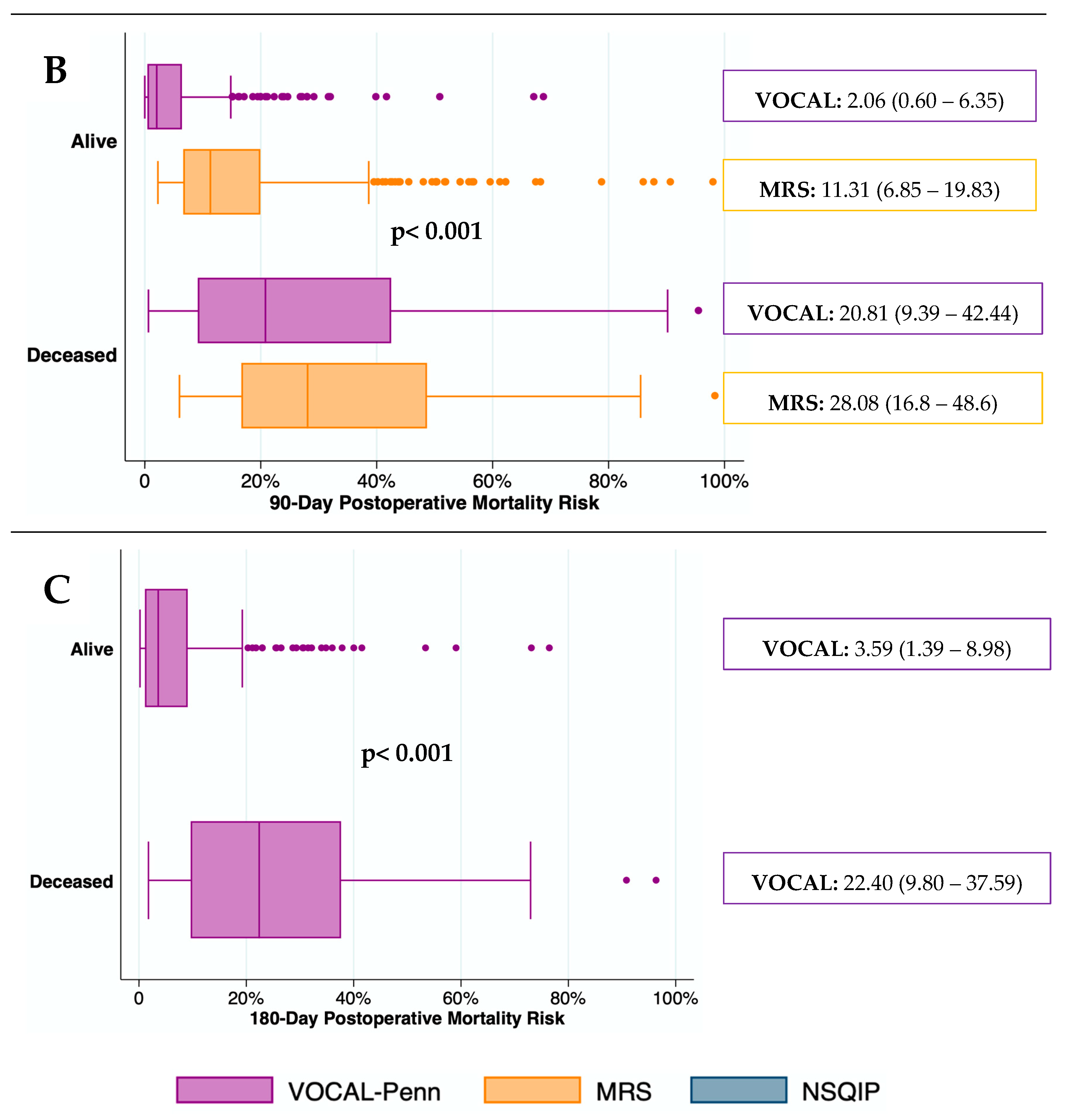

The predictive capacity for mortality of surgical risk scores was depicted graphically in

Figure 3. The median (IQR) mortality rate was significantly higher in deceased patients than in those who remained alive at all-time points (p< 0.001). The median (IQR) mortality risk predicted by the MRS in patients who remained alive at 30 and 90 days after surgery was higher than by the VOCAL-Penn. In contrast, the median (IQR) mortality risk predicted by the NSQIP in deceased patients, 30 days after surgery, was lower than by the VOCAL-Penn.

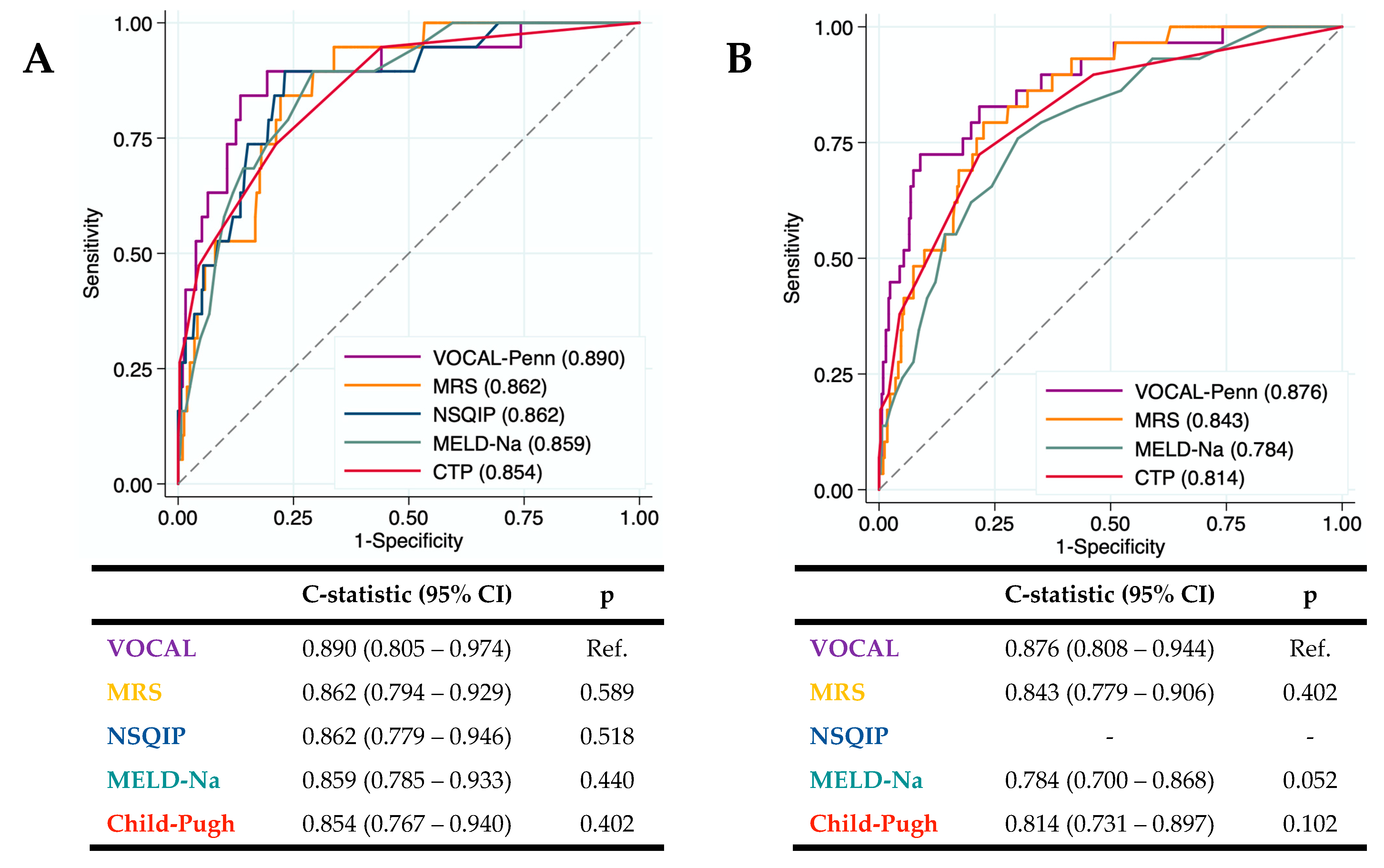

The diagnostic accuracy of the surgical risk scales (CTP, MELD-Na, NSQIP, MRS, and VOCAL-Penn) for identifying the 30 and 90-day postoperative mortality was evaluated in our cohort (

Figure 4a,b). The VOCAL-Penn showed a good predictive capacity for mortality at 30 days (C-statistic

VP-30D= 0.890) and 90 days (C-statistic

VP-90D= 0.876). The c-statistic (95%CI) of each score was compared with VOCAL-Penn (as the reference). Even though the VOCAL-Penn presented a higher c-statistic than the rest of the scores, the differences with the MRS, NSQIP, MELD-Na, and CTP were not statistically significant.

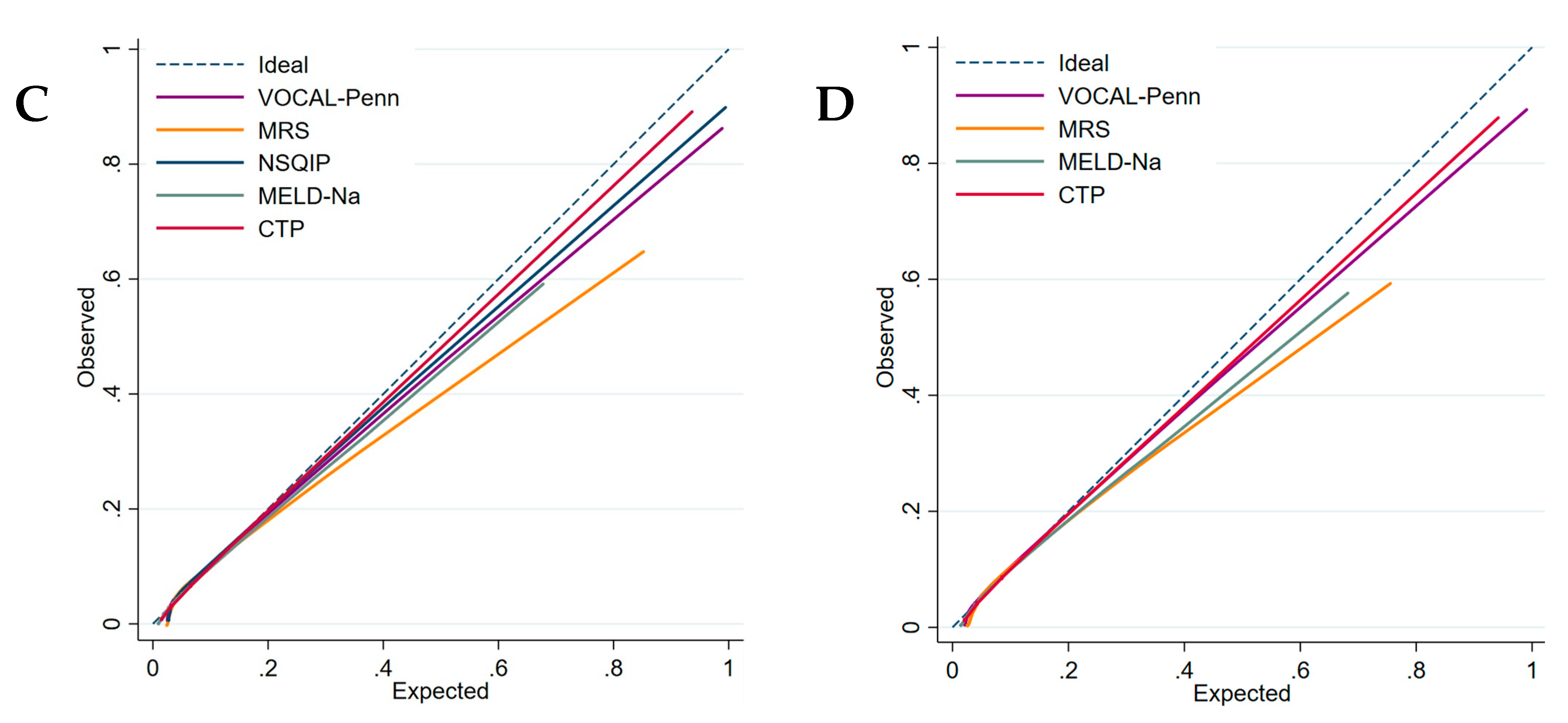

Calibration curves (

Figure 4c,d) showed that the CTP and the VOCAL-Penn have better calibration than the MRS at 30 and 90 days because the MRS overestimates postoperative mortality. The MELD-Na has a better calibration at 30 days than at 90 days.

The overall performance of the surgical risk scales was evaluated with the Brier score (

Table 4). The Brier score at 30 and 90 days after surgery for VOCAL-Penn (Brier

VP-30D= 0.046 and Brier

VP-90D= 0.055) was similar to NSQIP (Brier

NSQIP-30D= 0.044) and lower than MRS (Brier

MRS-30D= 0.058 and Brier

MRS-90D= 0.081), MELD-Na (Brier

MELD-30D= 0.058 and Brier

MELD-90D= 0.082) and Child-Pugh (Brier

CTP-30D= 0.050 and Brie

CTP-90D= 0.074).

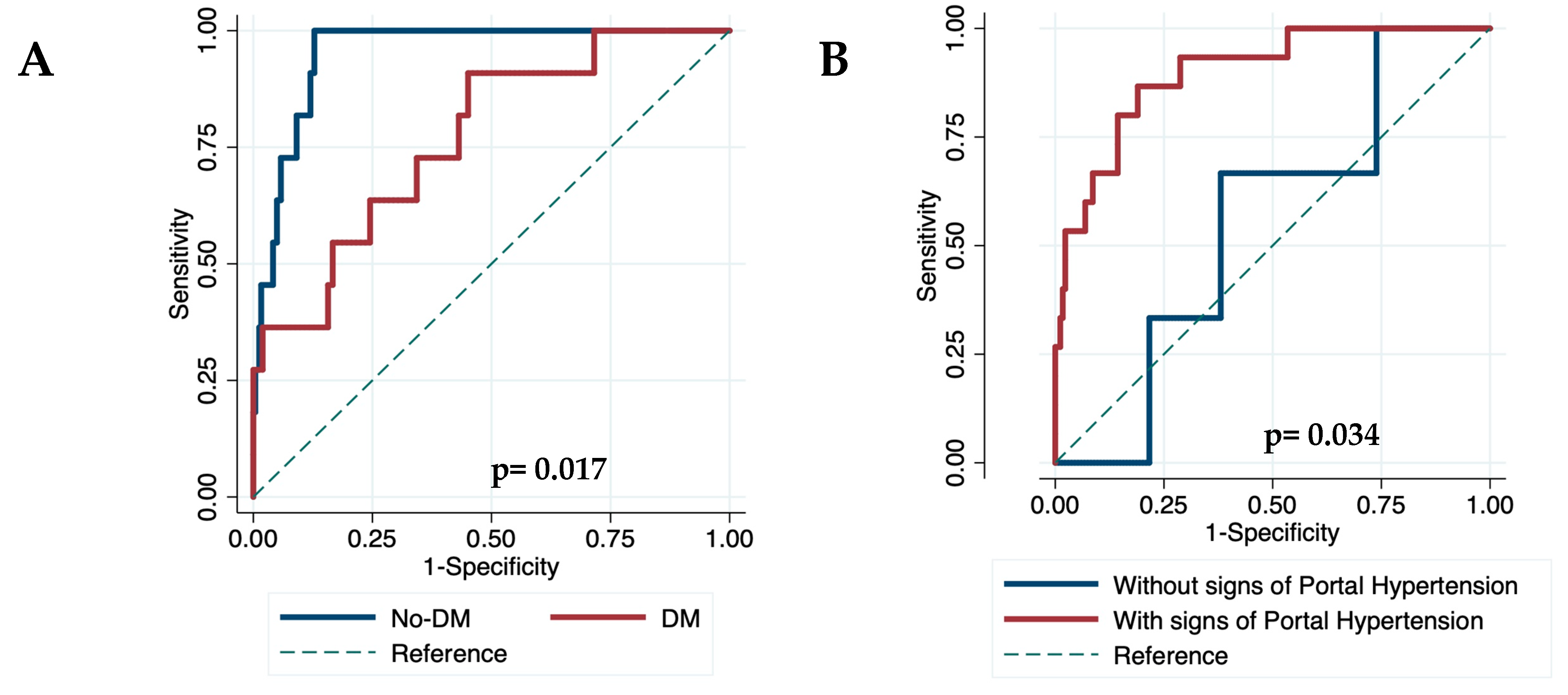

3.5. Diagnostic Accuracy of VOCAL-Penn in Different Scenarios.

Finally, we evaluated the diagnostic accuracy of the VOCAL-Penn for identifying the 30, 90, and 180-day postoperative mortality in different scenarios. The diagnostic accuracy of VOCAL-Penn did not reveal differences according to gender, etiology of ACLD, or the presence of chronic kidney disease. However, the VOCAL-Penn showed a lower discrimination capacity at 30 days in patients with diabetes (C-statistic

30D= 0.770) compared to those without (C-statistic

30D= 0.953)(p=0.017)(

Figure 5a), in patients without endoscopic signs of portal hypertension (C-statistic

30D= 0.555) compared to those with (C-statistic

30D= 0.898)(p=0.034)(

Figure 5b), and for abdominal wall surgeries (C-statistic

30D= 0.608) compared to abdominal (C-statistic

30D= 0.916) or orthopedic (C-statistic

30D= 0.948) surgeries (p<0.05 in both cases). A decrease in diagnostic accuracy according to the category of surgery has also been found 90 and 180 days after surgery. Similarly, its discrimination capacity at 180 days was lower for urgent (C-statistic

180D= 0.692) compared to elective (C-statistic

180D= 0.901) surgeries (p=0.008).

4. Discussion

The postoperative mortality of patients with ACLD is an important area of improvement for the professionals who participate in the care process of these patients, especially considering that the need for surgical interventions has increased with aging and comorbidity. Our European cohort of patients with ACLD has shown a mortality rate after surgery similar to American cohorts[

12,

13]. Liver decompensation, sepsis, and cardiovascular events were the most frequent causes of death. However, substantial differences were found when comparing the H. Mar and VOCAL-Penn cohorts. Our European cohort showed: 1) a more equilibrated distribution of males (64.8% vs. 97.2%); 2) alcohol consumption as the predominant etiology of ACLD; 3) a lower presence of metabolic and cardiovascular comorbidities such as diabetes, obesity, and hypertension, with a lower representation of patients with ASA-IV (24.2% vs. 54.4%); and 4) a higher frequency of abdominal (laparoscopic and laparotomy) and urgent surgeries.

The mortality rate after surgery in patients with ACLD in our cohort was 6.4% at 30 days, 9.8% at 90 days, and 13.7% at 180 days, similar to those previously described in American cohorts of creation and validation of VOCAL-Penn[

12,

13]. The variables independently associated with mortality were age, ASA scale, bilirubin, albumin, INR, open abdominal surgery, and urgent surgeries. Additionally, unlike the original VOCAL-Penn study, major orthopedic surgery was also associated with mortality. Therefore, variables associated with mortality in our cohort could be grouped into four categories: 1) age and comorbidity (ASA scale); 2) liver function (bilirubin, albumin, and INR); 3) type and urgency of surgery; and 4) complications during the admission (AKI and bacterial infections).

The CirCom score was not useful to assess postoperative mortality in our study, probably because it was designed to assess the risk of long-term mortality associated with comorbidity. Classic liver function scores such as CTP and MELD-Na showed lower diagnostic accuracy than other scores in our cohort, similar to previously published[

12].

The discriminative ability of the MRS was similar to the VOCAL-Penn’s but the median (IQR) mortality risk predicted by the MRS in patients who remained alive at 30 and 90 days after surgery was higher than by the VOCAL-Penn, showing an overestimation of the risk and high variability. Moreover, the Brier score showed higher values for MRS than for VOCAL-Penn demonstrating a worse calibration and capacity for predicting postoperative mortality. These findings could be explained, at least in part, by differences in the prevalence of comorbidities, CLD stage, and surgical invasivity reported in 2007[

11].

For the first time, the NSQIP calculator[

10] has been evaluated exclusively in patients with ACLD. We found that NSQIP had a good discrimination and calibration to predict mortality at 30 days probably due to the significative prevalence of ascites before surgery in our cohort. However, the median (IQR) mortality risk at 30 days after surgery predicted by the NSQIP in deceased patients was lower than by the VOCAL-Penn, showing an infra-estimation of the risk and a lower accurate prediction. Therefore, we recommend evaluating the NSQIP in multicenter large cohorts of patients with ACLD before concluding its usefulness in this specific population.

The necessity for useful tools in patients with ACLD led to the design and validation of the VOCAL-Penn score in 2021[

12,

13]. This American cohort included almost exclusively men with a high prevalence of metabolic comorbidities and ASA-IV. In contrast, our cohort has included a higher proportion of patients with alcohol consumption and hepatitis C infection, and undergoing more frequent abdominal or urgent surgeries. These baseline differences between H. Mar and VOCAL-Penn cohorts could explain the null association of MAFLD or obesity with mortality in our cohort. Neither chronic kidney disease nor baseline creatinine was independently associated with mortality in the H. Mar cohort, and no differences in the model were found when choosing platelet levels. These variables are included in the VOCAL-Penn score but could be redundant in European cohorts with a lower presence of metabolic and cardiovascular comorbidities (obesity, diabetes, and hypertension). Despite baseline differences between H. Mar and VOCAL-Penn cohorts, VOCAL-Penn showed a very good discrimination ability for predicting mortality at 30 and 90 days. The calibration curve for VOCAL-Penn was not excellent but the Brier score was the lowest for predicting mortality at 90 days in our European cohort. Importantly, the VOCAL-Penn’s diagnostic accuracy was significantly lower in patients with diabetes (C-statistic

30D= 0.770), without signs of portal hypertension (C-statistic

30D= 0.555), undergoing abdominal wall surgery (C-statistic

30D= 0.608), or for urgent surgeries (C-statistic

180D= 0.692). However, a more detailed analysis of multicenter European cohorts is required to draw solid conclusions and establish preventive strategies.

Our study has some limitations. First, it has been performed in a single center. However, our results are based on a large cohort of patients very well characterized by surgeons, anesthesiologists, pharmacists, and hepatologists. Second, it is a retrospective study that only evaluated patients who underwent surgery. Therefore, those who did not undergo the surgery due to the perception by the multidisciplinary team that the available scales showed a not acceptable high risk were not included. Third, the lack of some variables led to the unavailability of some scores in some surgeries (vascular, thoracic, and cardiac) that could be underrepresented. However, the predictive capacity of the scales has been compared in the patients with all the data. In contrast, our study has important strengths and findings: 1) it is the first European cohort evaluating VOCAL-Penn and NSQIP scales in a large well-characterized cohort of patients with ACLD; 2) we have found substantial differences when comparing European and American cohorts; 3) some variables included in VOCAL-Penn did not associated with mortality; 4) calibration of VOCAL-Penn score was not excellent in our cohort; and 5) we have identified patients (with diabetes, or without signs of portal hypertension) and surgeries (abdominal wall and urgent) discriminated suboptimal by the VOCAL-Penn score.

5. Conclusions

Our European cohort of patients with ACLD has shown a mortality rate after surgery similar to those previously described in American studies. Liver decompensation, sepsis, and cardiovascular events were the most frequent causes of death. However, substantial differences have been found when compared with American cohorts. Some variables included in the VOCAL-Penn score were not associated with an increased risk of mortality. Consequently, the calibration of the VOCAL-Penn score was not excellent and the discriminative ability decreased in some subgroups of our patients. We consider that our results should be validated in larger multicenter and extensive prospective studies to confirm these findings and to construct new and more accurate surgical scores for European patients.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, LC, AP, JA, JAC; methodology, LC, AP, JA, JAC.; software, LC, CER, JCA; validation, LC, AP, JA, JAC; formal analysis, LC, XD, JAC; investigation, LC, AP, EC, AS, CER, AC, JA, JAC; resources, LC, AP, JA, JAC; data curation, LC; writing—original draft preparation, LC, JAC; writing—review and editing, AP, EC, AS, CER, XD, AC, JA; visualization, LC, JAC; supervision, JAC; project administration, JAC; funding acquisition. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This project has received the support of “Programa de Qualitat del Parc de Salut Mar” granted in the 18th Call for Projects 2022 for Quality Improvement of the “Parc de Salut Mar”.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted by the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Ethical Committee of our institution ‘Comitè Ètic d'Investigació Clínica -Parc de Salut Mar’ (study reference 2020/9640, and date of approval 22nd December 2020).

Informed Consent Statement

Patient consent was waived due to the retrospective nature of the study.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Johnson:, K.M.; Newman, K.L.; Green, P.K.; Berry, K.; Cornia, P.B.; Wu, P.; Beste, L.A.; Itani, K.; Harris, A.H.S.; Kamath, P.S.; et al. Incidence and Risk Factors of Postoperative Mortality and Morbidity After Elective Versus Emergent Abdominal Surgery in a National Sample of 8193 Patients With Cirrhosis. Ann Surg 2021, 274, e345–e354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ziser, A.; Plevak, D.J.; Wiesner, R.H.; Rakela, J.; Offord, K.P.; Brown, D.L. Morbidity and mortality in cirrhotic patients undergoing anesthesia and surgery. Anesthesiology 1999, 90, 42–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- del Olmo, J.A.; Flor-Lorente, B.; Flor-Civera, B.; Rodriguez, F.; Serra, M.A.; Escudero, A.; Lledo, S.; Rodrigo, J.M. Risk factors for nonhepatic surgery in patients with cirrhosis. World J Surg 2003, 27, 647–652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Telem, D.A.; Schiano, T.; Goldstone, R.; Han, D.K.; Buch, K.E.; Chin, E.H.; Nguyen, S.Q.; Divino, C.M. Factors that predict outcome of abdominal operations in patients with advanced cirrhosis. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2010, 8, 451–457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jacob, K.A.; Hjortnaes, J.; Kranenburg, G.; de Heer, F.; Kluin, J. Mortality after cardiac surgery in patients with liver cirrhosis classified by the Child-Pugh score. Interactive cardiovascular and thoracic surgery 2015, 20, 520–530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Northup, P.G.; Wanamaker, R.C.; Lee, V.D.; Adams, R.B.; Berg, C.L. Model for End-Stage Liver Disease (MELD) predicts nontransplant surgical mortality in patients with cirrhosis. Ann Surg 2005, 242, 244–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Charlson, M.E.; Pompei, P.; Ales, K.L.; MacKenzie, C.R. A new method of classifying prognostic comorbidity in longitudinal studies: development and validation. J Chronic Dis 1987, 40, 373–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horvath, B.; Kloesel, B.; Todd, M.M.; Cole, D.J.; Prielipp, R.C. The Evolution, Current Value, and Future of the American Society of Anesthesiologists Physical Status Classification System. Anesthesiology 2021, 135, 904–919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jepsen, P.; Vilstrup, H.; Lash, T.L. Development and validation of a comorbidity scoring system for patients with cirrhosis. Gastroenterology 2014, 146, 147–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bilimoria, K.Y.; Liu, Y.; Paruch, J.L.; Zhou, L.; Kmiecik, T.E.; Ko, C.Y.; Cohen, M.E. Development and evaluation of the universal ACS NSQIP surgical risk calculator: a decision aid and informed consent tool for patients and surgeons. J Am Coll Surg 2013, 217, 833–842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Teh, S.H.; Nagorney, D.M.; Stevens, S.R.; Offord, K.P.; Therneau, T.M.; Plevak, D.J.; Talwalkar, J.A.; Kim, W.R.; Kamath, P.S. Risk factors for mortality after surgery in patients with cirrhosis. Gastroenterology 2007, 132, 1261–1269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahmud, N.; Fricker, Z.; Hubbard, R.A.; Ioannou, G.N.; Lewis, J.D.; Taddei, T.H.; Rothstein, K.D.; Serper, M.; Goldberg, D.S.; Kaplan, D.E. Risk Prediction Models for Post-Operative Mortality in Patients With Cirrhosis. Hepatology 2021, 73, 204–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mahmud, N.; Fricker, Z.; Panchal, S.; Lewis, J.D.; Goldberg, D.S.; Kaplan, D.E. External Validation of the VOCAL-Penn Cirrhosis Surgical Risk Score in 2 Large, Independent Health Systems. Liver Transpl 2021, 27, 961–970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Augustin, S.; Millan, L.; Gonzalez, A.; Martell, M.; Gelabert, A.; Segarra, A.; Serres, X.; Esteban, R.; Genesca, J. Detection of early portal hypertension with routine data and liver stiffness in patients with asymptomatic liver disease: a prospective study. J Hepatol 2014, 60, 561–569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lin, Z.H.; Xin, Y.N.; Dong, Q.J.; Wang, Q.; Jiang, X.J.; Zhan, S.H.; Sun, Y.; Xuan, S.Y. Performance of the aspartate aminotransferase-to-platelet ratio index for the staging of hepatitis C-related fibrosis: an updated meta-analysis. Hepatology 2011, 53, 726–736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Procopet, B.; Berzigotti, A. Diagnosis of cirrhosis and portal hypertension: imaging, non-invasive markers of fibrosis and liver biopsy. Gastroenterol Rep (Oxf) 2017, 5, 79–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- de Franchis, R.; Bosch, J.; Garcia-Tsao, G.; Reiberger, T.; Ripoll, C.; Baveno, V.I.I.F. Baveno VII - Renewing consensus in portal hypertension. J Hepatol 2022, 76, 959–974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Franchis, R.; Baveno, V.I.F. Expanding consensus in portal hypertension: Report of the Baveno VI Consensus Workshop: Stratifying risk and individualizing care for portal hypertension. J Hepatol 2015, 63, 743–752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kamath, P.S.; Wiesner, R.H.; Malinchoc, M.; Kremers, W.; Therneau, T.M.; Kosberg, C.L.; D'Amico, G.; Dickson, E.R.; Kim, W.R. A model to predict survival in patients with end-stage liver disease. Hepatology 2001, 33, 464–470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, W.R.; Biggins, S.W.; Kremers, W.K.; Wiesner, R.H.; Kamath, P.S.; Benson, J.T.; Edwards, E.; Therneau, T.M. Hyponatremia and mortality among patients on the liver-transplant waiting list. N Engl J Med 2008, 359, 1018–1026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Russ, K.B.; Stevens, T.M.; Singal, A.K. Acute Kidney Injury in Patients with Cirrhosis. J Clin Transl Hepatol 2015, 3, 195–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swets, J.A. Measuring the accuracy of diagnostic systems. Science 1988, 240, 1285–1293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hanley, J.A.; McNeil, B.J. A method of comparing the areas under receiver operating characteristic curves derived from the same cases. Radiology 1983, 148, 839–843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).