1. Introduction

Cervical cancer is the fourth most frequently diagnosed malignancy and the fourth leading cause of cancer-related death among women worldwide [

1]. Radical hysterectomy (RH) with pelvic lymph node assessment is the standard treatment for early-stage cervical cancer (stages IB1, IB2 and IIA1 of the International Federation of Gynecology and Obstetrics – FIGO 2018 - classification). In these stages, radiotherapy (RT) has shown similar survival rates but is associated with more side effects, being therefore reserved for cases in which surgery is contraindicated [

2,

3]. The combination of radical surgery and RT is associated with significantly increased morbidity and should be avoided [

3].

Since the Gynecologic Oncology Group (GOG) published in 1990 [

4] that tumor size, depth of stromal invasion and presence of lymphovascular space invasion (LVSI) are independent prognostic factors for tumor relapse after RH, patients presenting these pathological conditions are classified into an intermediate recurrence risk group. In 1999, Sedlis et al. [

5] published the results of a prospective, randomized study (GOG-92 trial) comparing RT with no further treatment in patients presenting a combination of these intermediate-risk factors (IRFs) after RH, and reported a 46% decrease in the recurrence rate in the RT group. Based on these results, adjuvant RT has become the recommended treatment for this subgroup of patients by many international guidelines [

3,

6,

7,

8]. However, this study was performed more than two decades ago and its results may not be comparable with current clinical practice since the measurement of tumor size was carried out exclusively by clinical examination instead of imaging, and surgical radicality was not described. Many more recent studies show that excellent local control can be achieved with surgery alone, although most of them are retrospective [

9,

10]. The need of RT in these intermediate-risk patients is, therefore, a controversial issue nowadays.

On the other hand, patients with positive pelvic lymph nodes, microscopic involvement of the parametrium or positive margins are considered as a high-risk population for recurrence, since the presence of these factors significantly decreases survival rates. According to a prospective randomized study performed by Peters et al. [

11] in 2000, patients with these unfavorable factors benefit from concurrent administration of RT + chemotherapy (CT), as it has shown better overall survival (OS) and disease-free survival (DFS). Since then, this has been the standard recommended treatment for patients with these pathological findings [

3].

The primary aim of this study was to determine whether adjuvant RT has an impact on survival after RH for early-stage cervical cancer according to the Sedlis criteria. The secondary aim was to analyze if there was a significantly difference in OS between patients who presented one or two IRFs depending on whether or not they received RT. We also evaluate if there were other prognostic factors associated with tumor recurrence for these patients.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study design and data selection

We conducted a retrospective study including consecutive patients diagnosed with early-stage cervical cancer at the Gynecologic Oncology Unit of La Paz University Hospital between January 2005 and December 2022. All preoperative stages IA1 with LVSI, IA2, IB1, IB2 and IIA1 of FIGO 2018 classification and all histologic subtypes were included in the study. Although RH is not currently recommended in stages IA, it was an accepted alternative in many guidelines when LVSI was present, so these patients were also included in our study. All patients underwent primary surgical treatment by RH with pelvic lymphadenectomy or pelvic sentinel lymph node biopsy (SLNB) and received follow-up care at the same center. Exclusion criteria included patients who underwent fertility-sparing surgery or radical parametrectomy after simple hysterectomy, or patients with advanced stages or incomplete medical records. Querleu-Morrow’s classification was used to describe the radicality of the intervention [

12]. All surgical procedures were performed by gynecologic oncologists. External beam radiation (EBRT), CT and brachytherapy (BT) were selectively used postoperatively depending on the institutional tumor board decision, based on the presence of histologic risk factors and patients characteristics. Irradiation of the pelvis was performed with a total dose of 45 to 50.4 Gray. When CT was administered, weekly cisplatin (40mg/m

2) was used as chemotherapeutic agent.

Tumor diameter ≥4cm (in the final paraffin section), presence of LVSI or deep or middle third stromal invasion were defined as Sedlis (intermediate-risk) criteria [

5]. Peters criteria [

11] (high-risk criteria) were defined as the presence of parametrial invasion, positive pelvic lymph nodes (micrometastases or macrometastases) and/or positive surgical margins.

The data were obtained through a review of patients’ medical records after the approval from the Ethics and Clinical Research Committee of La Paz University Hospital (Reference PI-3668). Clinical, surgical and pathological data were collected from all elegible patients. Patients were classified into no adjuvant treatment and patients who received adjuvant treatment.

OS was defined as the time from the end of treatment to the date of death. DFS was defined as the time from the end of treatment to the diagnosis of recurrence (local or metastatic).

2.2. Statistical analysis

A descriptive analysis of the quantitative variables was performed using the mean and standard deviation (SD) or the median and interquartile range (IQR) if the variables were not normally distributed; these variables were compared using Student’s t test or the Mann–Whitney test in cases of non-normality. Qualitative variables were described using frequency distributions and percentages, and were compared using the Pearson χ2 test or Fisher’s exact test. Kaplan-Meier survival analysis was used for the calculation of OS and PFS. Survival curves were compared using the log-rank test. Univariate and multivariate analysis of prognostic factors to predict survival outcomes were performed using Cox proportional-hazards regression models. A stepwise backward model selection was performed for variables with p≤0.20 in univariate analysis with p<0.05 to be retained in the final model. Statistical significance was defined as p value less than 0.05. All statistical analysis were performed using STATA Statistics/Data Analysis (StataCorp LP, Texas USA).

3. Results

From our initial cohort of 134 patients, a total of 121 (90,29%) eligible patients were included in the study. The median age in the cohort was 48.4 (SD 11.5) years. The tumor types were squamous cell carcinoma in 74 (61.7%) patients, adenocarcinoma in 18 (15%) patients, adenosquamous carcinoma in 23 (19.2%) patients and other infrequent subtypes in 5 (4.2%) patients. The most frequent FIGO stage was IB2 in 48 (40%) patients, followed by IB1 in 32 (26.7%) patients. Death data was missing for 6 patients. Of the remaining 115 patients, the median follow-up time was 70.2 months (IQR: 31.9 to 120.8). Recurrence rate was 24.79%. 73 (60.3%) patients underwent no adjuvant treatment and 48 (39.7%) received adjuvant RT (with or without CT). 56 (56.6 %) patients had one Sedlis criteria, of whom 46.4% received adjuvant RT, in contrast with patients who had two Sedlis criteria (26.3%) where 73% received RT. There were only 4 patients (4%) who met three Sedlis Criteria and all of them received adjuvant RT.

We formed two groups depending on whether patients received adjuvant treatment or not. The baseline, surgical and pathological characteristics of both groups are shown in

Table 1. Patients who received RT treatment had more advanced tumor stages (p<0.001), higher clinical (p<0.001) and radiological (p<0.0001) tumor size and less conization rates (p=0.004). Moreover, RT group had higher tumor grade (p<0.001), increased LVSI (p<0.001), a higher proportion of positive margins (p=0.001) and higher parametrial (p<0.001) and deep stromal invasion (p<0.0001) rates. Reviewing Sedlis criteria as well as Peters criteria, in the adjuvant treatment group there was a higher number of patients who met two Sedlis criteria (p=0.002) or at least one Peters criteria (p<0.001).

After adjustment for statistically significant variables at univariate analysis, radiotherapy was not found to be a statistically significant prognostic factor for OS (hazard ratio [HR] = 1.605, 95% confidence interval [CI]: 0.294-8.767, p=0.584) or PFS (HR=1.536, 95%CI: 0.364-6.482, p=0.559). However, positive LVSI and rare tumoral histologies (different to squamous cell carcinoma, adenocarcinoma or adenosquamous carcinoma) were correlated with OS (p=0.019, p=0.021 respectively), although not with PFS (p=0.098, p=0.654 respectively). Having prior conization was a protective factor for recurrence (HR=0.269, 95%CI: 0.080-0.898, p=0.033). The number of positive pelvic lymph nodes, maximum tumor diameter, tumor grade, presence of positive margins, stromal invasion, parametrial invasion and tumor histology were not correlated with OS and DFS rates. The results of multivariate analysis are shown in

Table 2.

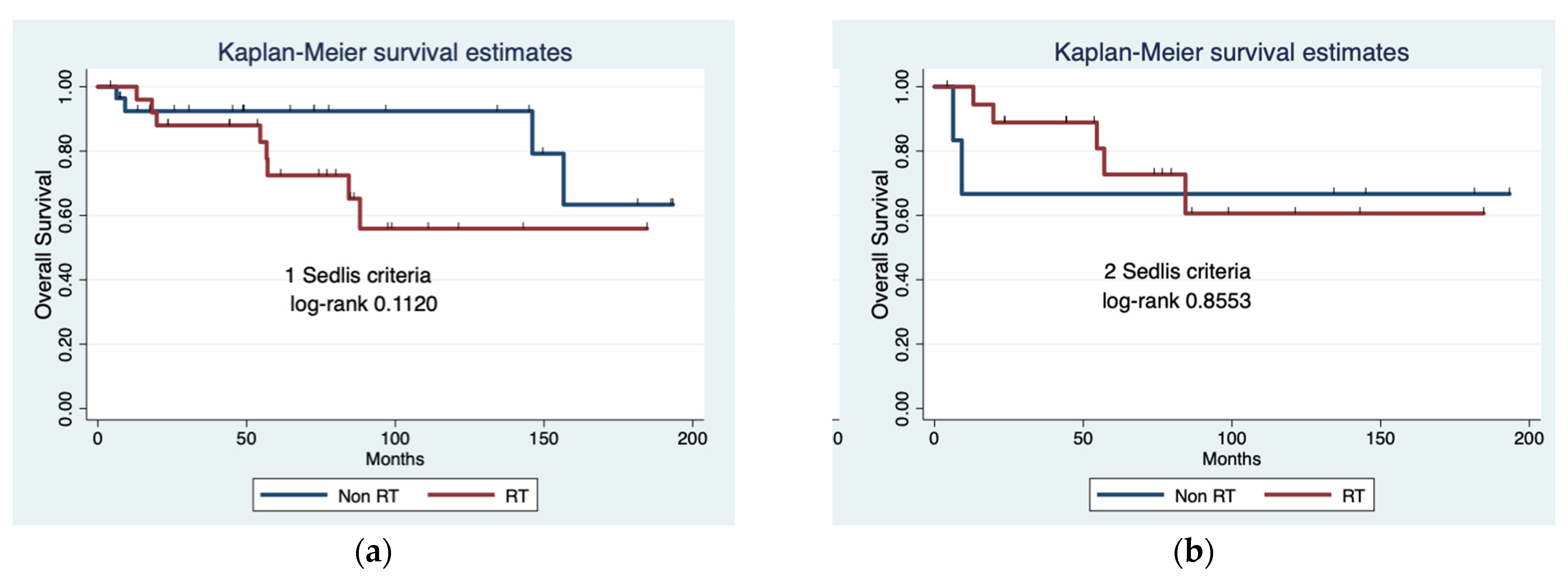

Finally, when comparing patients who met only one ore two Sedlis criteria (and no Peters criteria), there were no statistically significant differences in OS between RT and no further treatment in either group (log-rank 0.112 and 0.8553 respectively) (

Figure 1).

4. Discussion

The results of this study showed that RT does not have an impact on survival in patients who meet one or two intermediate risk criteria without high-risk criteria. As previously mentioned, GOG-92 trial [

5] was the one that determined the benefit of adjuvant RT in patients with IRFs after RH. In this study, patients that presented at least two IRFs were included. They reported a DFS rate at two years of 88% in RT group and 79% in no further treatment group. In the extended follow-up data published by Rotman et al. [

13], the improvement of DFS rates was confirmed in the RT group. However, no significant differences in OS were found (HR=0.70; 90%CI= 0.46 to 1.05; p=0.074). Although this is a prospective randomized study, it was published more than 20 years ago and has many critical points [

14]. First of all, tumor size was assessed by visual inspection rather than by imaging techniques as recommended by current quality indicators for surgical treatment of cervical cancer [

15]. Secondly, the type of parametrial resection was not reported, making it impossible to determine the extent of radicality, which is essential data to assess if an optimal surgical management was performed. Moreover, 26.7% patients of the Sedlis study had tumors >4cm that probably would not be candidates for surgery today. Furthermore, SLNB ultrastaging performed nowadays can exclude high-risk patients that could have been not detected in the GOG-92 trial. All this weaknesses could mean that the population treated in the Sedlis trial is different from patients currently undergoing RH, making the results not comparable [

14].

Studies conducted after GOG-92 trial are mostly retrospective and the data are contradictory. Nevertheless, most of them show that adequate surgical management may be sufficient for intermediate-risk patients after RH. In the study carried out by Haesen et al. [

16] that included 182 patients with FIGO stage IB1 and a combination IRFs, the recurrence rate was only 10% despite the fact that most of the patients did not received adjuvant RT. Two other retrospective studies that included a large cohort of patients found no survival benefit of adjuvant RT or concurrent chemoradiotherapy compared with no further treatment [

17,

18]. In some retrospective studies, different statistical techniques were used to homogenize the groups and improve the validity of the results, reaching similar conclusions: in the multicentric study performed by Ye et al. [

9] that included patients with only one IRF and compared adjuvant RT, adjuvant CT or no adjuvant treatment, no significant differences were found in the 5-year OS (p= 0. 486) and DFS (p=0.874) rates between RT group and no further treatment group after a propensity score matching; similar results were recently found by Tuscharoenporn et al. [

19] in their propensity score-adjusted analysis of 219 patients with stages IB-IIA and IRF according to Sedlis trial criteria. There were no significant association between adjuvant treatment and OS (p=0.36) or DFS (p=0.42), although a lower pelvic relapse was observed in the RT group (p=0.02).

In contrast to these results, in the meta-analysis performed by Sagi-Dain et al. [

20] adjuvant RT showed a reduced recurrence risk in OS in patients with two IRFs (OR 1.86, p=0.04), but these benefits were not shown after adding patients with only one risk factor.

Since all these studies differ from each other in the number of Sedlis criteria included, we investigated whether there was a benefit in terms of OS in our cohort in patients who received RT depending on whether they presented only one or two IRFs (and none high-risk factors). No statistically significant differences were found in either of the two groups. According to our results, in the study of 134 matched patients with one or more IRFs [

21] the number of positive IRFs did not affect DFS (5-year DFS of 84.7% for one IRF and 5-year DFS of 85.6% for two or three IRFs; p=0.994). The effect on OS could not be calculated because only 5 patients died during the follow-up period.

In a recent meta-analysis performed by Gómez-Hidalgo et al. [

22] that included eight studies (Sedlis trial among them) reported similar outcomes in terms of recurrence and mortality between adjuvant treatment and observation.

Following the results obtained in two retrospective studies conducted by Cibula et al. [

23,

24] in which radical surgery alone achieved similar OS and DFS rates compared to those achieved by adjuvant treatment, they have developed a prospective, randomized trial (CERVANTES trial), currently ongoing, that is expected to provide definitive insights into the role of radiotherapy in patients with intermediate-risk cervical cancer [

25].

Our study had several limitations mainly due to its retrospective nature and the limited number of patients. Since most patients who received adjuvant treatment had poor prognostic factors, both treatment groups were not completely balanced. In addition, our study included all histological subtypes compared to most publications that exclude the infrequent ones, which could have generated bias. On the other hand, in our center, prior to 2009 the imaging technique used for diagnosis was ultrasound instead of magnetic resonance imaging. This may have increased the rate of patients who were not actually candidates for RH. Despite all this, RT has not been shown to be a statistically significant prognostic factor for recurrence or death in the multivariate logistic regression model and OS wasn’t improved in patients who met either only one or two IRFs and received RT compared with no further treatment group.

5. Conclusions

No benefit in terms of survival were found in patients with two Sedlis criteria who received RT, which is in line with the most recent literature results. It is possible that the improvement of diagnostic and surgical techniques that have been developed in recent years will enable a more accurate selection of patients eligible for surgery, allowing an optimal control of the disease without the need of adjuvant treatments. The results of prospective randomized trials are needed to confirm these findings.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M. A.-E. and I.Z.; methodology, M. A.-E., I.Z. and M.Gorostidi; validation, I.Z, M.Gorostidi and A. H.; formal analysis, I.Z. and M.Gorostidi; investigation, M. A.-E., M. Gorostidi, M.Gracia, V.G.-P., M.D.D., J.S., A.H and I.Z.; data curation, M.A.-E., M. Gorostidi, M. Gracia, V.G.-P., M.D.D. and J.S.; writing—original draft preparation, M. A.-E.; writing—review and editing, M. A.-E., I.Z., M.Gorostidi, M. Gracia., V.G.-P., M.D.D., J.S. and A.H.; supervision, I.Z and A.H. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Ethics Committee of La Paz University Hospital (protocol code PI-3668 and approved on April 30, 2019).

Informed Consent Statement

Patient consent was waived due to the retrospective nature o the study, approved by the Ethics Committee.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding authors. The availability of the data is restricted to investigators based in academic institutions.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Sung, H.; Ferlay, J.; Siegel, R.L.; Laversanne, M.; Soerjomataram, I.; Jemal, A.; Bray, F. Global Cancer Statistics 2020: GLOBOCAN Estimates of Incidence and Mortality Worldwide for 36 Cancers in 185 Countries. CA A Cancer J Clin 2021, 71, 209–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhatla, N.; Aoki, D.; Sharma, D.N.; Sankaranarayanan, R. Cancer of the cervix uteri: 2021 update. Int J Gynecol Obstet 2021, 155, 28–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cibula, D.; Raspollini, M.R.; Planchamp, F.; Centeno, C.; Chargari, C.; Felix, A.; Fischerová, D.; Jahnn-Kuch, D.; Joly, F.; Kohler, C.; et al. ESGO/ESTRO/ESP Guidelines for the management of patients with cervical cancer – Update 2023*. Int J Gynecol Cancer 2023, 33, 649–666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delgado GOG 1990.pdf.

- Sedlis, A.; Bundy, B.N.; Rotman, M.Z.; Lentz, S.S.; Muderspach, L.I.; Zaino, R.J. A Randomized Trial of Pelvic Radiation Therapy versus No Further Therapy in Selected Patients with Stage IB Carcinoma of the Cervix after Radical Hysterectomy and Pelvic Lymphadenectomy: A Gynecologic Oncology Group Study. Gynecologic Oncology 1999, 73, 177–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhatla, N.; Aoki, D.; Sharma, D.N.; Sankaranarayanan, R. Cancer of the cervix uteri. Int J Gynecol Obstet 2018, 143, 22–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Armstrong, D.K.; Alvarez, R.D.; Backes, F.J.; Bakkum-Gamez, J.N.; Barroilhet, L.; Behbakht, K.; Berchuck, A.; Chen, L.; Chitiyo, V.C.; Cristea, M.; et al. NCCN Guidelines® Insights: Ovarian Cancer, Version 3.2022: Featured Updates to the NCCN Guidelines. Journal of the National Comprehensive Cancer Network 2022, 20, 972–980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chino, J.; Annunziata, C.M.; Beriwal, S.; Bradfield, L.; Erickson, B.A.; Fields, E.C.; Fitch, K.; Harkenrider, M.M.; Holschneider, C.H.; Kamrava, M.; et al. Radiation Therapy for Cervical Cancer: Executive Summary of an ASTRO Clinical Practice Guideline. Practical Radiation Oncology 2020, 10, 220–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, Y.; Li, Z.; Kang, S.; Zhan, X.; Zhang, Y.; Xu, Y.; Li, W.; Lang, J.; Liu, P.; Chen, C. Impact of different postoperative adjuvant therapies on the survival of early-stage cervical cancer patients with one intermediate-risk factor: A multicenter study of 14 years. J of Obstet and Gynaecol 2023, jog.15632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cibula, D. Management of patients with intermediate-risk early stage cervical cancer. J Gynecol Oncol 2020, 31, e54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iii, W.A.P.; Liu, P.Y.; Ii, R.J.B.; Stock, R.J.; Monk, B.J.; Berek, J.S.; Souhami, L.; Grigsby, P.; Jr, W.G.; Alberts, D.S. Concurrent Chemotherapy and Pelvic Radiation Therapy Compared With Pelvic Radiation Therapy Alone as Adjuvant Therapy After Radical Surgery in High-Risk Early-Stage Cancer of the Cervix.

- Querleu, D.; Cibula, D.; Abu-Rustum, N.R. 2017 Update on the Querleu–Morrow Classification of Radical Hysterectomy. Ann Surg Oncol 2017, 24, 3406–3412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rotman, M.; Sedlis, A.; Piedmonte, M.R.; Bundy, B.; Lentz, S.S.; Muderspach, L.I.; Zaino, R.J. A phase III randomized trial of postoperative pelvic irradiation in stage IB cervical carcinoma with poor prognostic features: Follow-up of a gynecologic oncology group study. International Journal of Radiation Oncology*Biology*Physics 2006, 65, 169–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodriguez, J.; Viveros-Carreño, D.; Pareja, R. Adjuvant treatment after radical surgery for cervical cancer with intermediate risk factors: is it time for an update? Int J Gynecol Cancer 2022, 32, 1219–1226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cibula, D.; Planchamp, F.; Fischerova, D.; Fotopoulou, C.; Kohler, C.; Landoni, F.; Mathevet, P.; Naik, R.; Ponce, J.; Raspagliesi, F.; et al. European Society of Gynaecological Oncology quality indicators for surgical treatment of cervical cancer. Int J Gynecol Cancer 2020, 30, 3–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Haesen, J.; Salihi, R.; Van Gorp, T.; Van Nieuwenhuysen, E.; Han, S.N.; Christiaens, M.; Van Rompuy, A.-S.; Waumans, L.; Neven, P.; Vergote, I. Radical hysterectomy without adjuvant radiotherapy in patients with cervix carcinoma FIGO 2009 IB1, with or without positive Sedlis criteria. Gynecologic Oncology 2021, 162, 539–545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nasioudis, D.; Latif, N.A.; Giuntoli Ii, R.L.; Haggerty, A.F.; Cory, L.; Kim, S.H.; Morgan, M.A.; Ko, E.M. Role of adjuvant radiation therapy after radical hysterectomy in patients with stage IB cervical carcinoma and intermediate risk factors. Int J Gynecol Cancer 2021, 31, 829–834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, L.; Wen, H.; Feng, Z.; Han, X.; Zhu, J.; Wu, X. Role of adjuvant therapy after radical hysterectomy in intermediate-risk, early-stage cervical cancer. Int J Gynecol Cancer 2021, 31, 52–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tuscharoenporn, T.; Muangmool, T.; Charoenkwan, K. Adjuvant pelvic radiation versus observation in intermediate-risk early-stage cervical cancer patients following primary radical surgery: a propensity score-adjusted analysis. J Gynecol Oncol 2023, 34, e42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sagi-Dain, L.; Abol-Fol, S.; Lavie, O.; Sagi, S.; Ben Arie, A.; Segev, Y. Cervical Cancer with Intermediate Risk Factors: Is there a Role for Adjuvant Radiotherapy? A Systematic Review and a Meta-Analysis. Gynecol Obstet Invest 2019, 84, 606–615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turkmen, O.; Kilic, F.; Tokalioglu, A.A.; Cakir, C.; Yuksel, D.; Kilic, C.; Boran, N.; Kimyon Comert, G.; Turan, T. The effect of adjuvant radiotherapy on oncological outcomes in patients with early-stage cervical carcinoma with only intermediate-risk factors: a propensity score matching analysis. Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology 2022, 42, 3204–3211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gómez-Hidalgo, N.R.; Acosta, Ú.; Rodríguez, T.G.; Mico, S.; Verges, R.; Conesa, V.B.; Bradbury, M.; Pérez-Hoyos, S.; Pérez-Benavente, A.; Gil-Moreno, A. Adjuvant therapy in early-stage cervical cancer after radical hysterectomy: are we overtreating our patients? A meta-analysis. Clin Transl Oncol 2022, 24, 1605–1614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cibula, D.; Abu-Rustum, N.R.; Fischerova, D.; Pather, S.; Lavigne, K.; Slama, J.; Alektiar, K.; Ming-Yin, L.; Kocian, R.; Germanova, A.; et al. Surgical treatment of “intermediate risk” lymph node negative cervical cancer patients without adjuvant radiotherapy—A retrospective cohort study and review of the literature. Gynecologic Oncology 2018, 151, 438–443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cibula, D.; Akilli, H.; Jarkovsky, J.; Van Lonkhuijzen, L.; Scambia, G.; Meydanli, M.M.; Ortiz, D.I.; Falconer, H.; Abu-Rustum, N.R.; Odetto, D.; et al. Role of adjuvant therapy in intermediate-risk cervical cancer patients – Subanalyses of the SCCAN study. Gynecologic Oncology 2023, 170, 195–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cibula, D.; Borčinová, M.; Kocian, R.; Feltl, D.; Argalacsova, S.; Dvorak, P.; Fischerová, D.; Dundr, P.; Jarkovsky, J.; Höschlová, E.; et al. CERVANTES: an international randomized trial of radical surgery followed by adjuvant (chemo) radiation versus no further treatment in patients with early-stage, intermediate-risk cervical cancer (CEEGOG-CX-05; ENGOT-CX16). Int J Gynecol Cancer 2022, 32, 1327–1331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).