Submitted:

30 August 2023

Posted:

31 August 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

0. Introduction

- Our proposed lightweight superpixel metric graph neural network significantly reduces the learnable parameters by at most 10000 times compared with mainstream segmentation models.

- Our proposed superpixel-based model reduces the problem size and poses rich prior knowledge to the rarely considered graph structure data, which helps SMGNN achieve SOTA performance on white blood cell images.

- We innovatively propose superpixel metric learning according to the definition of superpixel metric score, which is more efficient than pixel-level metric learning.

- The whole deep learning based nucleus and cytoplasm segmentation and cell type classification system is accurate and efficient to execute in hematological laboratories.

1. Methodolgy of Superpixel Metric

1.1. Compression Ratio on Image Data

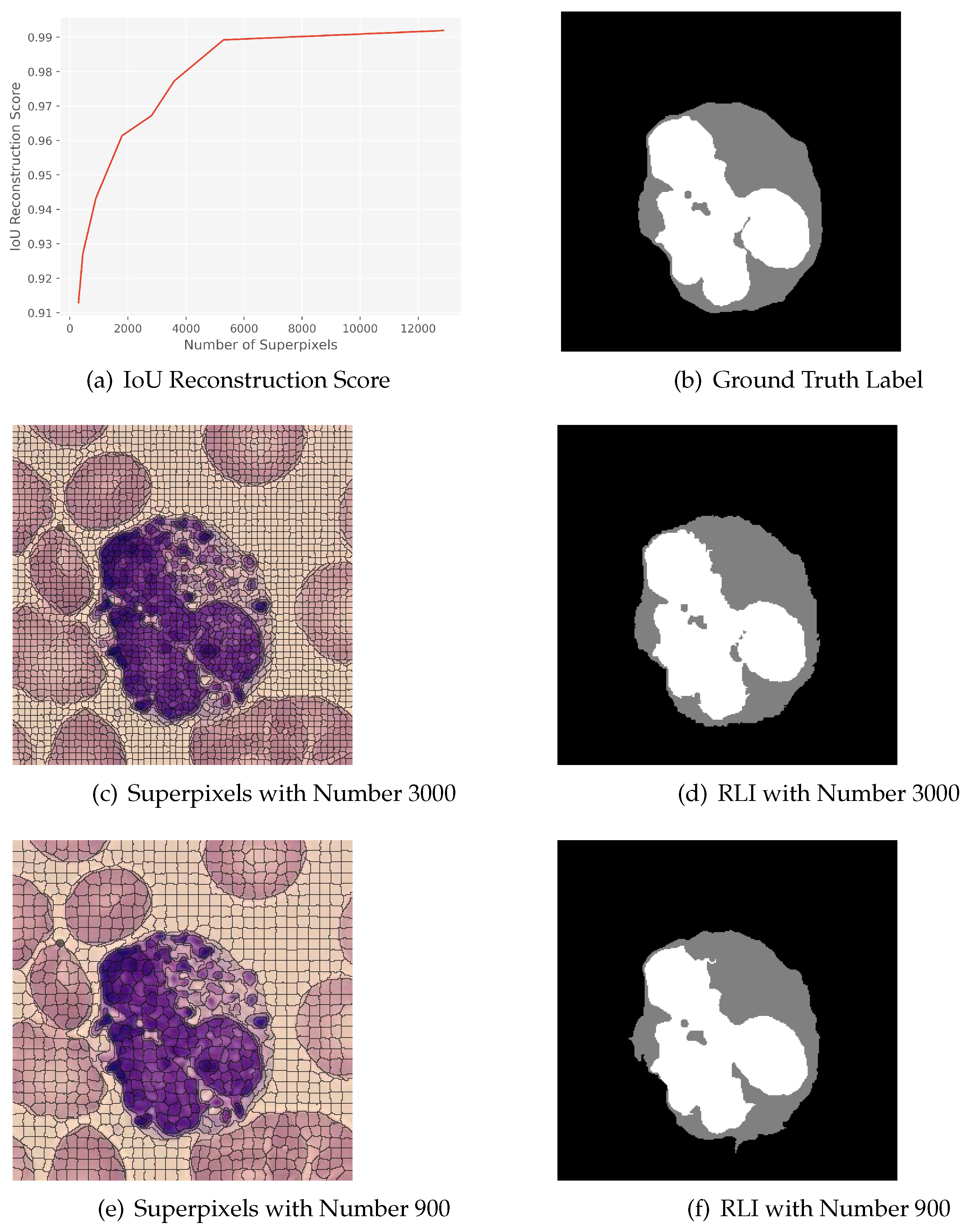

1.2. Quality of Superpixel and Reconstruction Score

1.3. Lightweight Graph Neural Networks for Superpixel Embedding

1.4. Memory Efficient Metric Learning

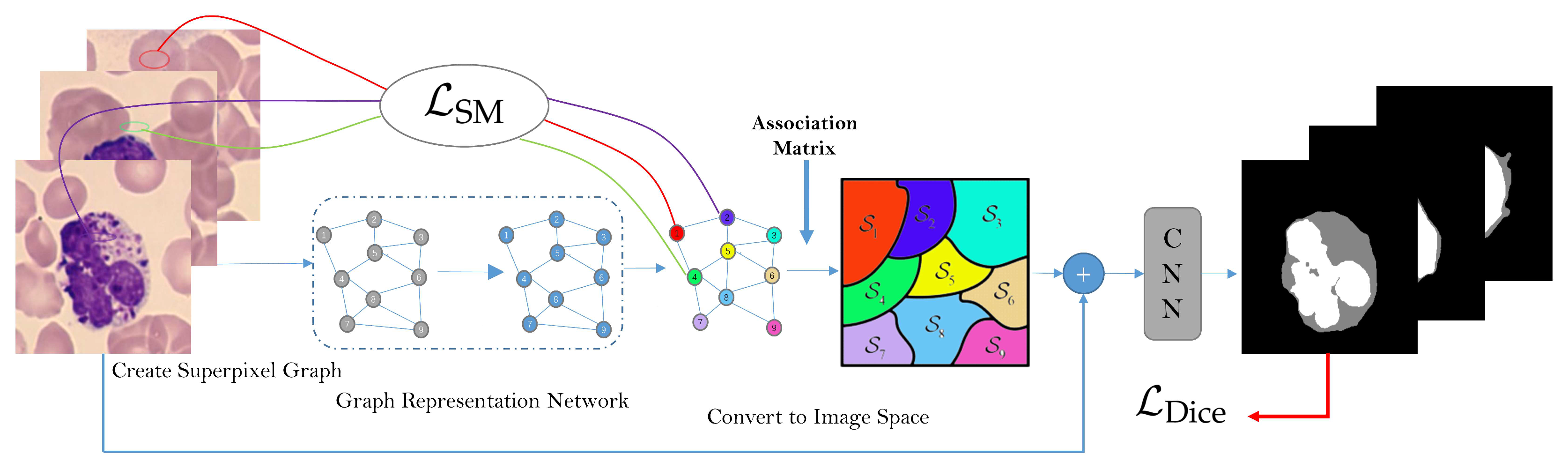

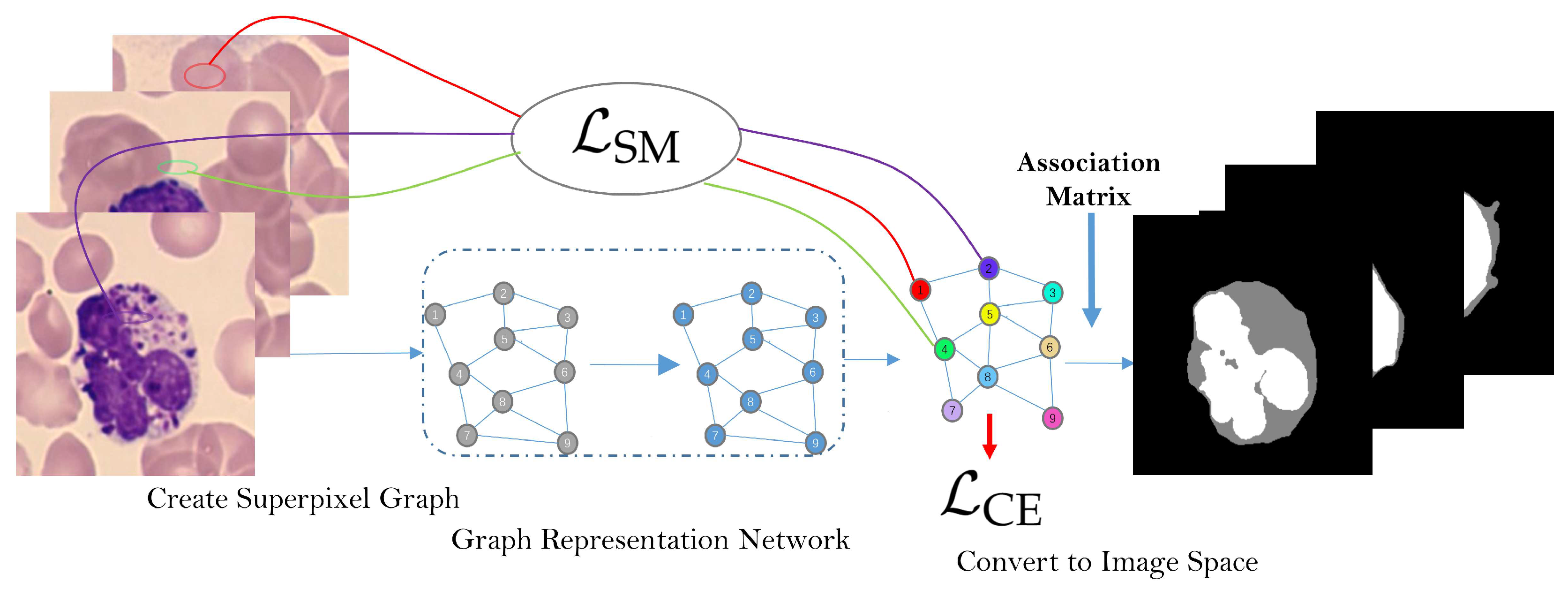

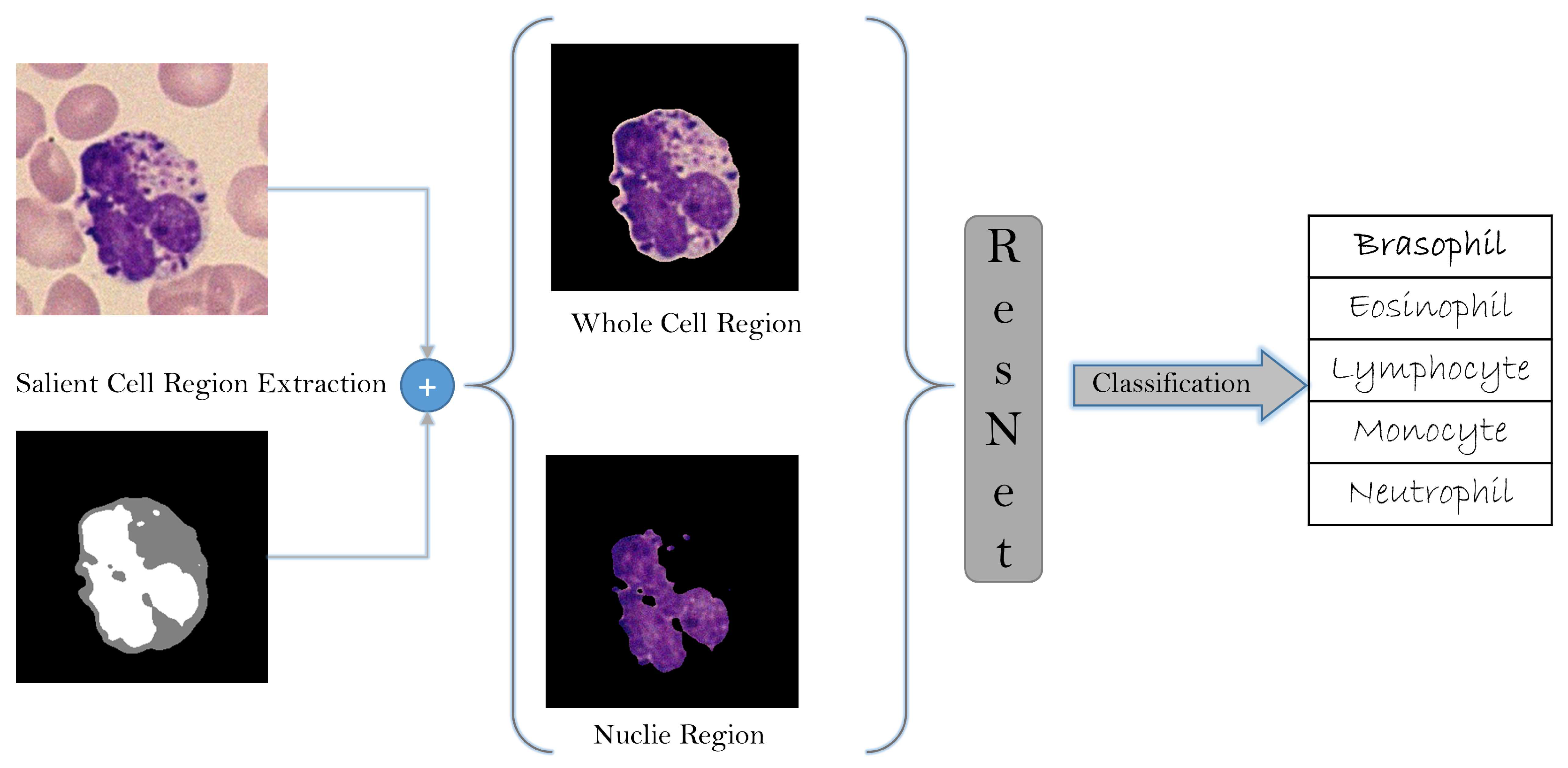

2. The Work-Flow and Architecture of SMGNN

3. Numerical Experiments

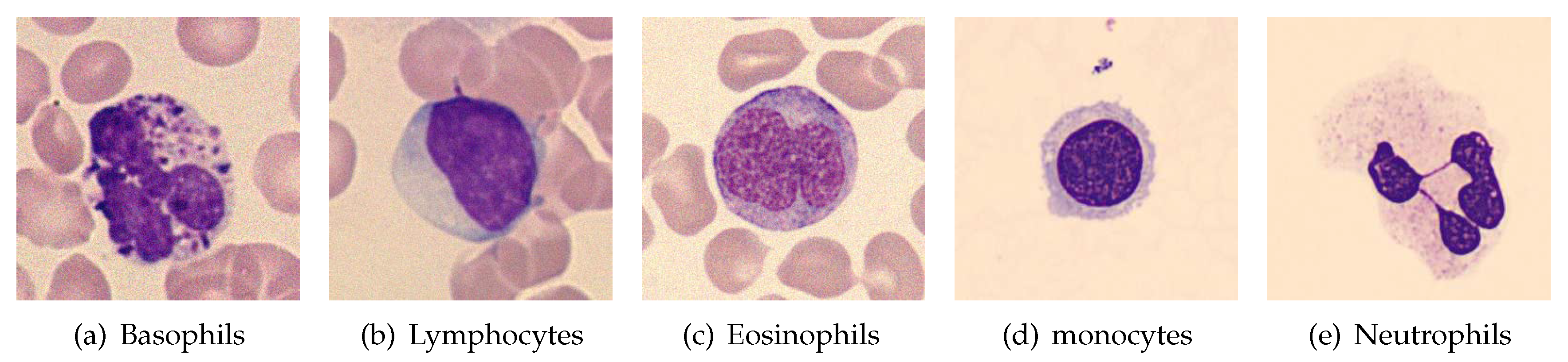

3.1. Dataset Description

3.2. Evaluation of Superpixel Scale

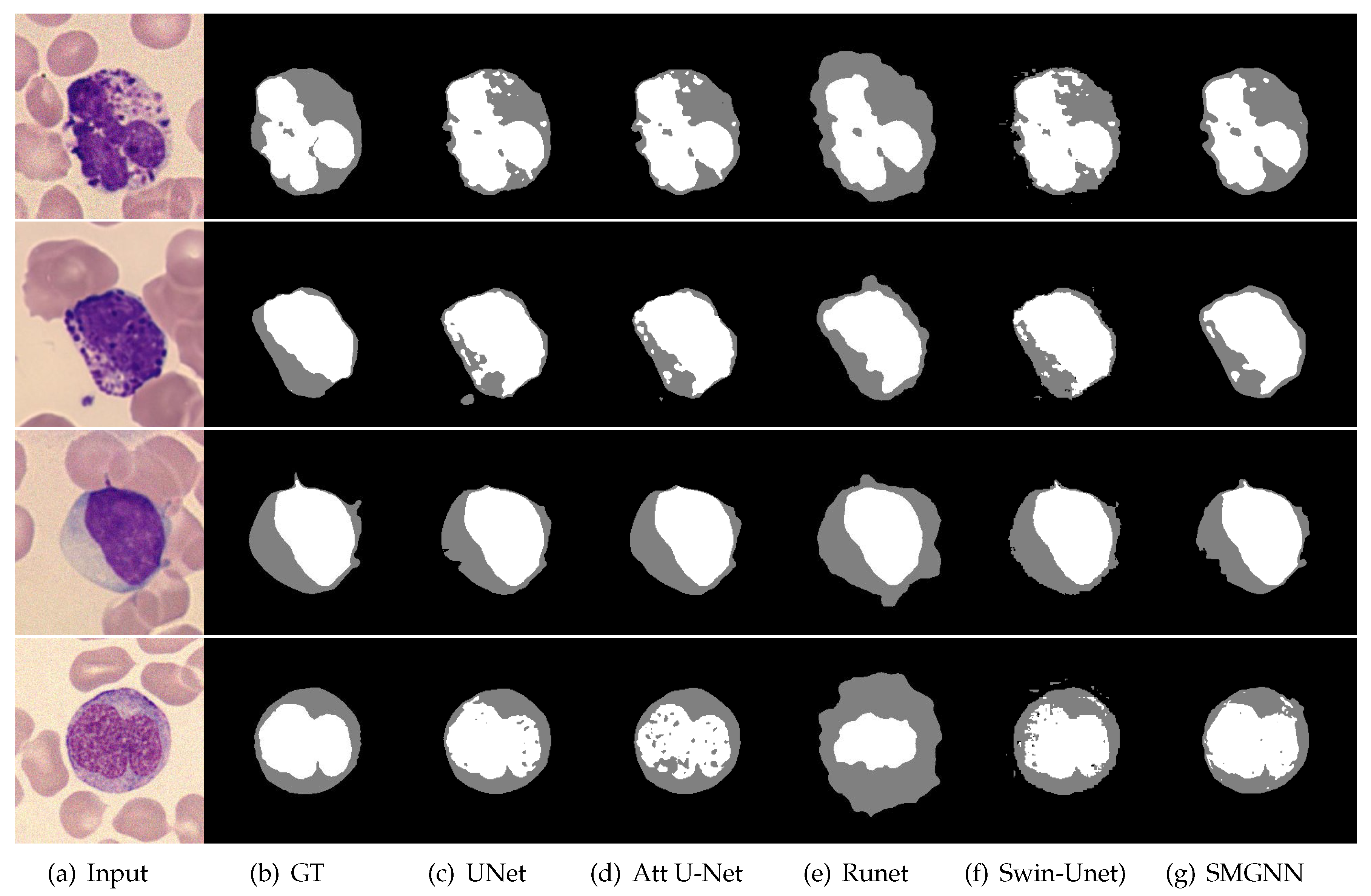

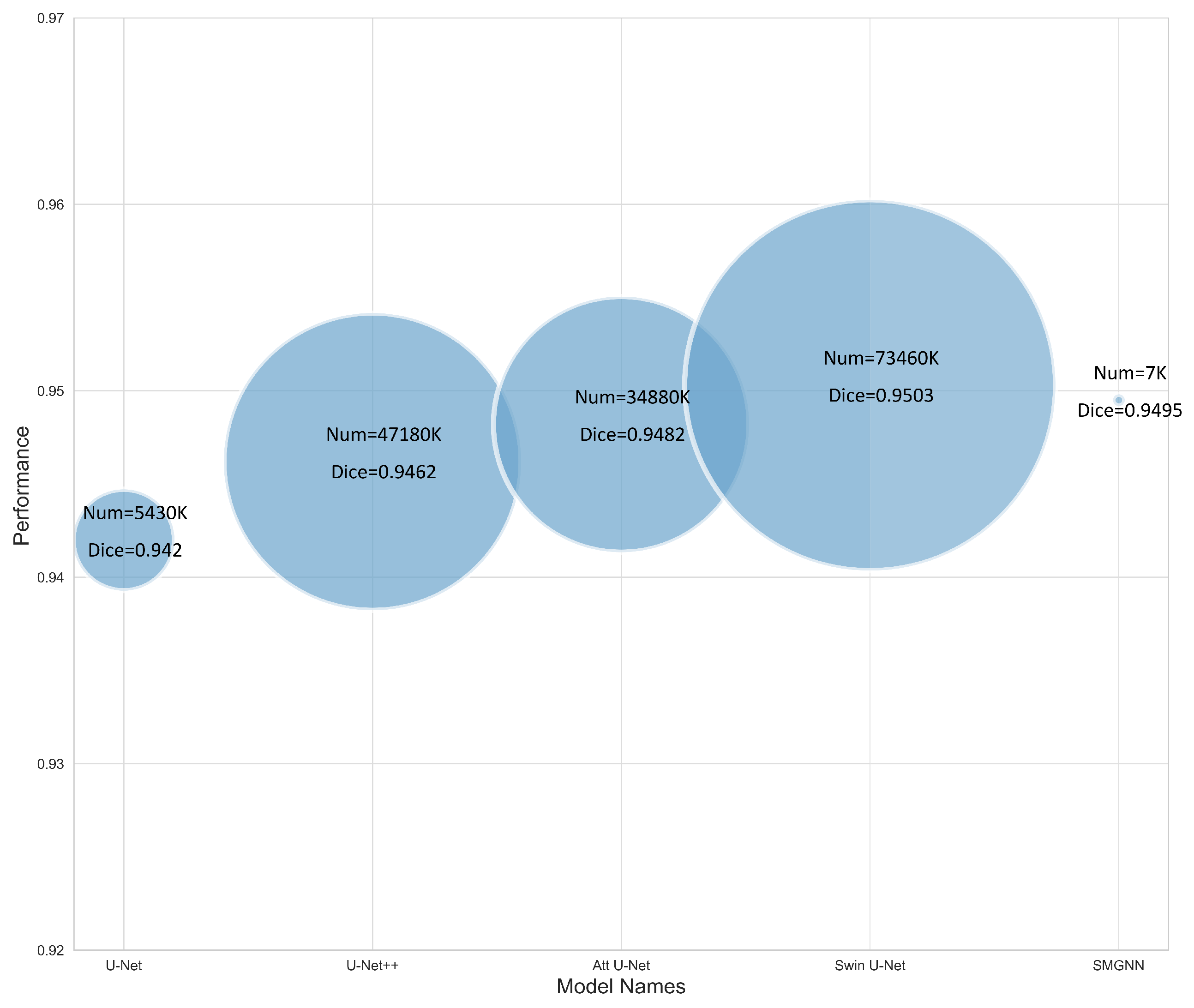

3.3. Comparison with Mainstream Deep Learning Segmentation Methods

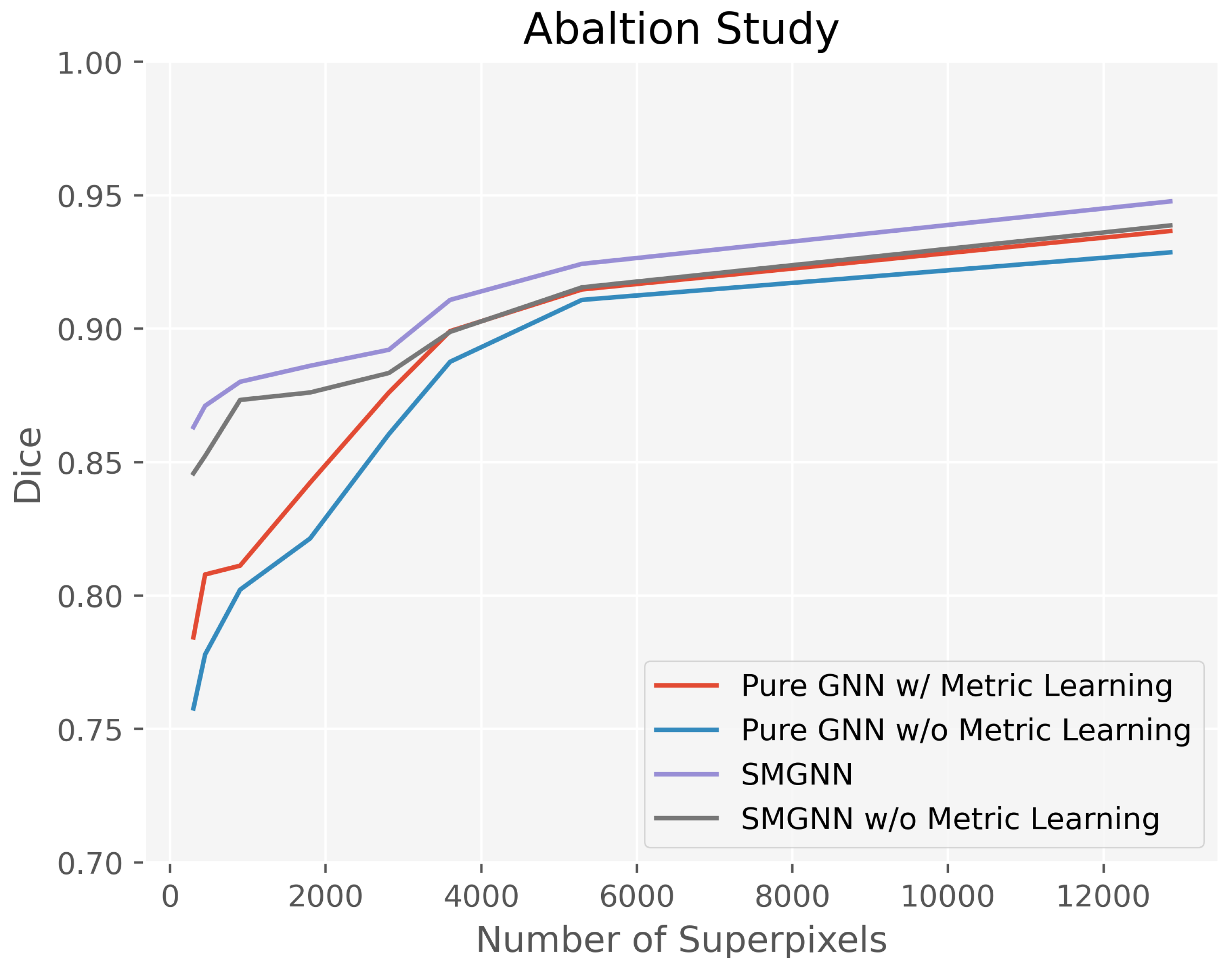

3.4. Ablation Study

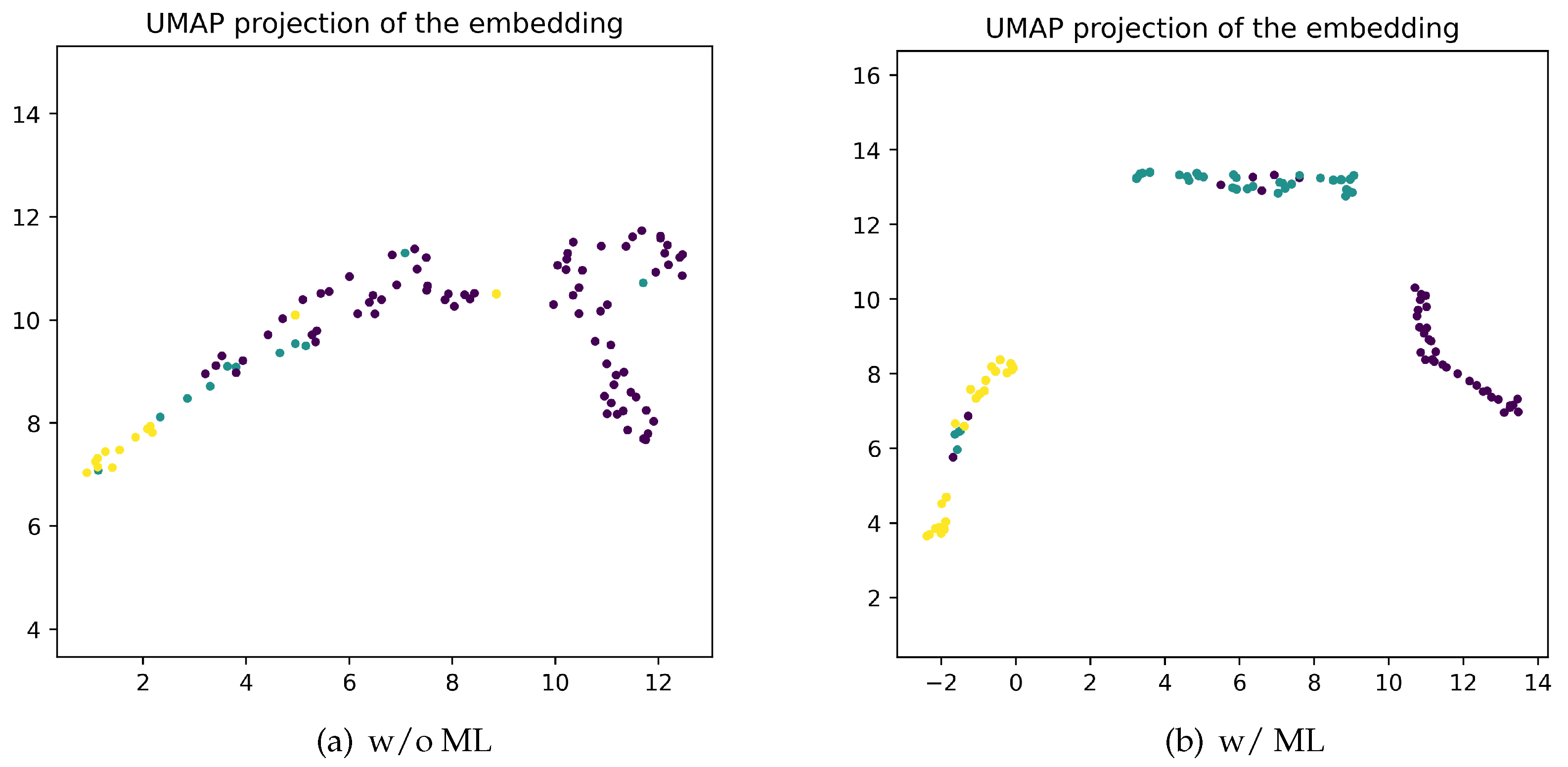

3.5. Effectiveness of Metric Learning on Embedding Space

3.6. White Blood Cells Type Classification Results

4. Conclusion

References

- Mohamed, H.; Omar, R.; Saeed, N.; Essam, A.; Ayman, N.; Mohiy, T.; AbdelRaouf, A. Automated detection of white blood cells cancer diseases. 2018 First international workshop on deep and representation learning (IWDRL). IEEE, 2018, pp. 48–54.

- Kruskall, M.S.; Lee, T.H.; Assmann, S.F.; Laycock, M.; Kalish, L.A.; Lederman, M.M.; Busch, M.P. Survival of transfused donor white blood cells in HIV-infected recipients. Blood, The Journal of the American Society of Hematology 2001, 98, 272–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xing, F.; Yang, L. Robust nucleus/cell detection and segmentation in digital pathology and microscopy images: a comprehensive review. IEEE reviews in biomedical engineering 2016, 9, 234–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zheng, X.; Wang, Y.; Wang, G.; Liu, J. Fast and robust segmentation of white blood cell images by self-supervised learning. Micron 2018, 107, 55–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, Y.; Wu, Y.; Wang, Z.; Wei, B.; Lai, M.; Shou, J.; Fan, Y.; Xu, Y. Cyclic Learning: Bridging Image-level Labels and Nuclei Instance Segmentation. IEEE Transactions on Medical Imaging 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gao, Z.; Shi, J.; Zhang, X.; Li, Y.; Zhang, H.; Wu, J.; Wang, C.; Meng, D.; Li, C. Nuclei grading of clear cell renal cell carcinoma in histopathological image by composite high-resolution network. Medical Image Computing and Computer Assisted Intervention–MICCAI 2021: 24th International Conference, Strasbourg, France, September 27–October 1, 2021, Proceedings, Part VIII 24. Springer, 2021, pp. 132–142.

- Ronneberger, O.; Fischer, P.; Brox, T. U-net: Convolutional networks for biomedical image segmentation. International Conference on Medical image computing and computer-assisted intervention. Springer, 2015, pp. 234–241.

- Zhou, Z.; Rahman Siddiquee, M.M.; Tajbakhsh, N.; Liang, J. Unet++: A nested u-net architecture for medical image segmentation. In Deep learning in medical image analysis and multimodal learning for clinical decision support; Springer, 2018; pp. 3–11.

- Huang, H.; Lin, L.; Tong, R.; Hu, H.; Zhang, Q.; Iwamoto, Y.; Han, X.; Chen, Y.W.; Wu, J. Unet 3+: A full-scale connected unet for medical image segmentation. ICASSP 2020-2020 IEEE International Conference on Acoustics, Speech and Signal Processing (ICASSP). IEEE, 2020, pp. 1055–1059.

- Jia, F.; Liu, J.; Tai, X.C. A regularized convolutional neural network for semantic image segmentation. Analysis and Applications 2021, 19, 147–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dosovitskiy, A.; Beyer, L.; Kolesnikov, A.; Weissenborn, D.; Zhai, X.; Unterthiner, T.; Dehghani, M.; Minderer, M.; Heigold, G.; Gelly, S. ; others. An image is worth 16x16 words: Transformers for image recognition at scale. arXiv preprint arXiv:2010.11929, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Z.; Lin, Y.; Cao, Y.; Hu, H.; Wei, Y.; Zhang, Z.; Lin, S.; Guo, B. Swin transformer: Hierarchical vision transformer using shifted windows. Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision, 2021, pp. 10012–10022.

- Nicolas Carion, Francisco Massa, G. S.N.U.A.K.; Zagoruyko, S. End-to-End Object Detection with Transformers. ECCV 2020, 2020, pp. 213–229.

- Petit, O.; Thome, N.; Rambour, C.; Themyr, L.; Collins, T.; Soler, L. U-net transformer: Self and cross attention for medical image segmentation. International Workshop on Machine Learning in Medical Imaging. Springer, 2021, pp. 267–276.

- Valanarasu, J.M.J.; Oza, P.; Hacihaliloglu, I.; Patel, V.M. Medical transformer: Gated axial-attention for medical image segmentation. Medical Image Computing and Computer Assisted Intervention–MICCAI 2021: 24th International Conference, Strasbourg, France, September 27–October 1, 2021, Proceedings, Part I 24. Springer, 2021, pp. 36–46.

- Cao, H.; Wang, Y.; Chen, J.; Jiang, D.; Zhang, X.; Tian, Q.; Wang, M. Swin-unet: Unet-like pure transformer for medical image segmentation. Computer Vision–ECCV 2022 Workshops: Tel Aviv, Israel, October 23–27, 2022, Proceedings, Part III. Springer, 2023, pp. 205–218.

- Chi, Z.; Wang, Z.; Yang, M.; Li, D.; Du, W. Learning to capture the query distribution for few-shot learning. IEEE Transactions on Circuits and Systems for Video Technology 2021, 32, 4163–4173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, G.D.; Masuda, S.; Yamaguchi, D.; Nagai, M. The optimal GNN-PID control system using particle swarm optimization algorithm. International Journal of Innovative Computing, Information and Control 2009, 5, 3457–3469. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Y.; Yi, K.; Liu, X.; Wang, Y.G.; Jin, S. ACMP: Allen-cahn message passing with attractive and repulsive forces for graph neural networks. The Eleventh International Conference on Learning Representations, 2022.

- Min, S.; Gao, Z.; Peng, J.; Wang, L.; Qin, K.; Fang, B. STGSN—A Spatial–Temporal Graph Neural Network framework for time-evolving social networks. Knowledge-Based Systems 2021, 214, 106746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bumgardner, B.; Tanvir, F.; Saifuddin, K.M.; Akbas, E. Drug-Drug Interaction Prediction: a Purely SMILES Based Approach. 2021 IEEE International Conference on Big Data (Big Data). IEEE, 2021, pp. 5571–5579.

- Bruna, J.; Zaremba, W.; Szlam, A.; LeCun, Y. Spectral networks and locally connected networks on graphs. arXiv preprint arXiv:1312.6203, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Defferrard, M.; Bresson, X.; Vandergheynst, P. Convolutional neural networks on graphs with fast localized spectral filtering. Advances in neural information processing systems 2016, 29. [Google Scholar]

- Kipf, T.N.; Welling, M. Semi-supervised classification with graph convolutional networks. arXiv preprint arXiv:1609.02907, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Veličković, P.; Cucurull, G.; Casanova, A.; Romero, A.; Liò, P.; Bengio, Y. Graph Attention Networks. International Conference on Learning Representations, 2018.

- Xu, K.; Hu, W.; Leskovec, J.; Jegelka, S. How powerful are graph neural networks? arXiv preprint arXiv:1810.00826, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Lu, Y.; Chen, Y.; Zhao, D.; Chen, J. Graph-FCN for Image Semantic Segmentation; Advances in Neural Networks – ISNN 2019, 2019.

- Zhang, L.; Li, X.; Arnab, A.; Yang, K.; Tong, Y.; Torr, P.H. Dual graph convolutional network for semantic segmentation. arXiv preprint arXiv:1909.06121, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Tian, Z.; Liu, L.; Zhang, Z.; Fei, B. Superpixel-based segmentation for 3D prostate MR images. IEEE transactions on medical imaging 2015, 35, 791–801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Monti, F.; Boscaini, D.; Masci, J.; Rodola, E.; Svoboda, J.; Bronstein, M.M. Geometric deep learning on graphs and manifolds using mixture model cnns. Proceedings of the IEEE conference on computer vision and pattern recognition, 2017, pp. 5115–5124.

- Gadde, R.; Jampani, V.; Kiefel, M.; Kappler, D.; Gehler, P.V. Superpixel Convolutional Networks using Bilateral Inceptions. Springer, Cham, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Avelar, P.H.; Tavares, A.R.; da Silveira, T.L.; Jung, C.R.; Lamb, L.C. Superpixel image classification with graph attention networks. 2020 33rd SIBGRAPI Conference on Graphics, Patterns and Images (SIBGRAPI). IEEE, 2020, pp. 203–209.

- Zhao, W.; Jiao, L.; Ma, W.; Zhao, J.; Zhao, J.; Liu, H.; Cao, X.; Yang, S. Superpixel-based multiple local CNN for panchromatic and multispectral image classification. IEEE Transactions on Geoscience and Remote Sensing 2017, 55, 4141–4156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, B.; Xie, X.; Ma, X.; Ren, G.; Ma, Y. Superpixel-based extended random walker for hyperspectral image classification. IEEE Transactions on Geoscience and Remote Sensing 2018, 56, 3233–3243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.; Li, S.; Fu, W.; Fang, L. Multiscale superpixel-based sparse representation for hyperspectral image classification. Remote Sensing 2017, 9, 139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Q.; Xiao, L.; Yang, J.; Wei, Z. CNN-enhanced graph convolutional network with pixel-and superpixel-level feature fusion for hyperspectral image classification. IEEE Transactions on Geoscience and Remote Sensing 2020, 59, 8657–8671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Felzenszwalb, P.F.; Huttenlocher, D.P. Efficient graph-based image segmentation. International journal of computer vision 2004, 59, 167–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, X.; Malik, J. Learning a classification model for segmentation. Computer Vision, IEEE International Conference on. IEEE Computer Society, 2003, Vol. 2, pp. 10–10.

- Liu, M.Y.; Tuzel, O.; Ramalingam, S.; Chellappa, R. Entropy rate superpixel segmentation. CVPR 2011. IEEE, 2011, pp. 2097–2104.

- Achanta, R.; Shaji, A.; Smith, K.; Lucchi, A.; Fua, P.; Süsstrunk, S. SLIC superpixels compared to state-of-the-art superpixel methods. IEEE transactions on pattern analysis and machine intelligence 2012, 34, 2274–2282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Z.; Chen, J. Superpixel segmentation using linear spectral clustering. Proceedings of the IEEE conference on computer vision and pattern recognition, 2015, pp. 1356–1363.

- Liu, Y.J.; Yu, C.C.; Yu, M.J.; He, Y. Manifold SLIC: A fast method to compute content-sensitive superpixels. Proceedings of the IEEE conference on computer vision and pattern recognition, 2016, pp. 651–659.

- Achanta, R.; Susstrunk, S. Superpixels and polygons using simple non-iterative clustering. Proceedings of the IEEE conference on computer vision and pattern recognition, 2017, pp. 4651–4660.

- Tu, W.C.; Liu, M.Y.; Jampani, V.; Sun, D.; Chien, S.Y.; Yang, M.H.; Kautz, J. Learning superpixels with segmentation-aware affinity loss. Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, 2018, pp. 568–576.

- Jampani, V.; Sun, D.; Liu, M.Y.; Yang, M.H.; Kautz, J. Superpixel sampling networks. Proceedings of the European Conference on Computer Vision (ECCV), 2018, pp. 352–368.

- Yang, F.; Sun, Q.; Jin, H.; Zhou, Z. Superpixel segmentation with fully convolutional networks. Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF conference on computer vision and pattern recognition, 2020, pp. 13964–13973.

- Suzuki, T. Superpixel segmentation via convolutional neural networks with regularized information maximization. ICASSP 2020-2020 IEEE International Conference on Acoustics, Speech and Signal Processing (ICASSP). IEEE, 2020, pp. 2573–2577.

- Zhu, L.; She, Q.; Zhang, B.; Lu, Y.; Lu, Z.; Li, D.; Hu, J. Learning the superpixel in a non-iterative and lifelong manner. Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, 2021, pp. 1225–1234.

- Saueressig, C.; Berkley, A.; Munbodh, R.; Singh, R. A joint graph and image convolution network for automatic brain Tumor segmentation. International MICCAI Brainlesion Workshop. Springer, 2021, pp. 356–365.

- Kulikov, V.; Lempitsky, V. Instance segmentation of biological images using harmonic embeddings. Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, 2020, pp. 3843–3851.

- Kim, J.; Kim, T.; Kim, S.; Yoo, C.D. Edge-labeling graph neural network for few-shot learning. Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF conference on computer vision and pattern recognition, 2019, pp. 11–20.

- Chen, T.; Kornblith, S.; Norouzi, M.; Hinton, G. A simple framework for contrastive learning of visual representations. International conference on machine learning. PMLR, 2020, pp. 1597–1607.

- Chen, X.; Fan, H.; Girshick, R.; He, K. Improved baselines with momentum contrastive learning. arXiv preprint arXiv:2003.04297, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- He, K.; Fan, H.; Wu, Y.; Xie, S.; Girshick, R. Momentum contrast for unsupervised visual representation learning. Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF conference on computer vision and pattern recognition, 2020, pp. 9729–9738.

- Caron, M.; Misra, I.; Mairal, J.; Goyal, P.; Bojanowski, P.; Joulin, A. Unsupervised learning of visual features by contrasting cluster assignments. Advances in neural information processing systems 2020, 33, 9912–9924. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, W.; Zhou, T.; Yu, F.; Dai, J.; Konukoglu, E.; Van Gool, L. Exploring cross-image pixel contrast for semantic segmentation. Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision, 2021, pp. 7303–7313.

- Gilmer, J.; Schoenholz, S.S.; Riley, P.F.; Vinyals, O.; Dahl, G.E. Neural message passing for quantum chemistry. ICML, 2017.

- Weisfeiler, B.; Leman, A. A reduction of a graph to a canonical form and an algebra arising during this reduction, Nauchno–Technicheskaja Informatsia, 9 (1968), 12–16.

- Achanta, R.; Susstrunk, S. Superpixels and Polygons using Simple Non-Iterative Clustering. IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), 2017.

- Milletari, F.; Navab, N.; Ahmadi, S.A. V-net: Fully convolutional neural networks for volumetric medical image segmentation. 2016 fourth international conference on 3D vision (3DV). IEEE, 2016, pp. 565–571.

- Kingma, D.P.; Ba, J. Adam: A Method for Stochastic Optimization. ICLR (Poster), 2015.

- McInnes, L.; Healy, J.; Melville, J. Umap: Uniform manifold approximation and projection for dimension reduction. arXiv preprint arXiv:1802.03426, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Acevedo, A.; Merino, A.; Alférez, S.; Molina, Á.; Boldú, L.; Rodellar, J. A dataset of microscopic peripheral blood cell images for development of automatic recognition systems. Data in brief 2020, 30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yampri, P.; Pintavirooj, C.; Daochai, S.; Teartulakarn, S. White blood cell classification based on the combination of eigen cell and parametric feature detection. 2006 1ST IEEE conference on industrial electronics and applications. IEEE, 2006, pp. 1–4.

- Livieris, I.E.; Pintelas, E.; Kanavos, A.; Pintelas, P. Identification of blood cell subtypes from images using an improved SSL algorithm. Biomedical Journal of Scientific & Technical Research 2018, 9, 6923–6929. [Google Scholar]

- Banerjee, R.; Ghose, A. A Light-Weight Deep Residual Network for Classification of Abnormal Heart Rhythms on Tiny Devices. Joint European Conference on Machine Learning and Knowledge Discovery in Databases. Springer, 2022, pp. 317–331.

- He, K.; Zhang, X.; Ren, S.; Sun, J. Deep residual learning for image recognition. Proceedings of the IEEE conference on computer vision and pattern recognition, 2016, pp. 770–778.

| 1 |

| Accuracy | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Basophil | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| Eosinophil | 0 | 8 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| Lymphocyte | 0 | 0 | 23 | 1 | 0 | |

| Monocyte | 0 | 0 | 0 | 10 | 0 | |

| Neutrophil | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 16 | |

| Overall Accuracy | - | - | - | - | - |

| Accuracy | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Basophil | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| Eosinophil | 2 | 5 | 0 | 0 | 1 | |

| Lymphocyte | 0 | 1 | 20 | 2 | 1 | |

| Monocyte | 0 | 0 | 3 | 6 | 1 | |

| Neutrophil | 2 | 1 | 2 | 0 | 12 | |

| Overall Accuracy | - | - | - | - | - |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).