1. Introduction

More than two-thirds of the Earth’s surface is covered by oceans, which harbor a vast array of creatures, including plants, animals and microbes. Since the ancient times, marine organisms had been served as the sources of foods [

1], cosmetic ingredients [

2], and drugs [

3], which are hotspots for global researchers nowadays [

4]. Continuous studies focused on the secondary metabolites derived from marine environments, resulting a rapid expansion of marine natural products [

5]. These substances displayed a wide spectrum of potential pharmacological effects, including antivirus [

6], anti-osteoclastogenesis [

7], antimicrobial [

8], antitumor [

9]. To date, almost 20 drugs from marine sources are in clinical use [

10].

The marine soft coral genus

Litophyton belongs to the family Nephtheidae, order Alcyonacea, subclass Octocorallia. The

Litophyton genus consists of near 100 species, according to the Word Register of Marine Species (WoRMS) [

11]. They are widely distributed throughout tropical and temperate waters, such as South China Sea [

12], Red Sea [

13], as well as other waters of Indo-Pacific Ocean [

14,

15,

16]. However, only a few specimens collected from South China Sea [

12], Red Sea [

17,

18], Indonesian [

15,

19] and Japanese [

16] waters have been chemically investigated, which calls for more attentions from the global researchers.

In was observed that the alcyonarian

Litophyton viridis provided chemical protection of a fish

Abudefduf leucogaster [

20]. The extracts of animals of the genus

Litophyton was biologically screened and showed a variety of potent bioactivities, such as antioxidant [

21], genotoxic [

18], cytotoxic [

21,

22], and HIV-1 enzyme inhibitory [

22] activities. Inspired by these bioassays, chemical investigations on the

Litophyton soft corals were carried out by the researchers worldwide. These reported studies revealed that the members of the genus

Litophyton are one of the most prolific producers of bioactive secondary metabolites (

Table S1). However, there was no specific review of substances from the soft corals of the title genus. On the basis of a extensive literature search using SciFinder, this work specifically summarized all metabolites from the genus

Litophyton for the first time, covering a period of near five decades (between 1975 and July, 2023).

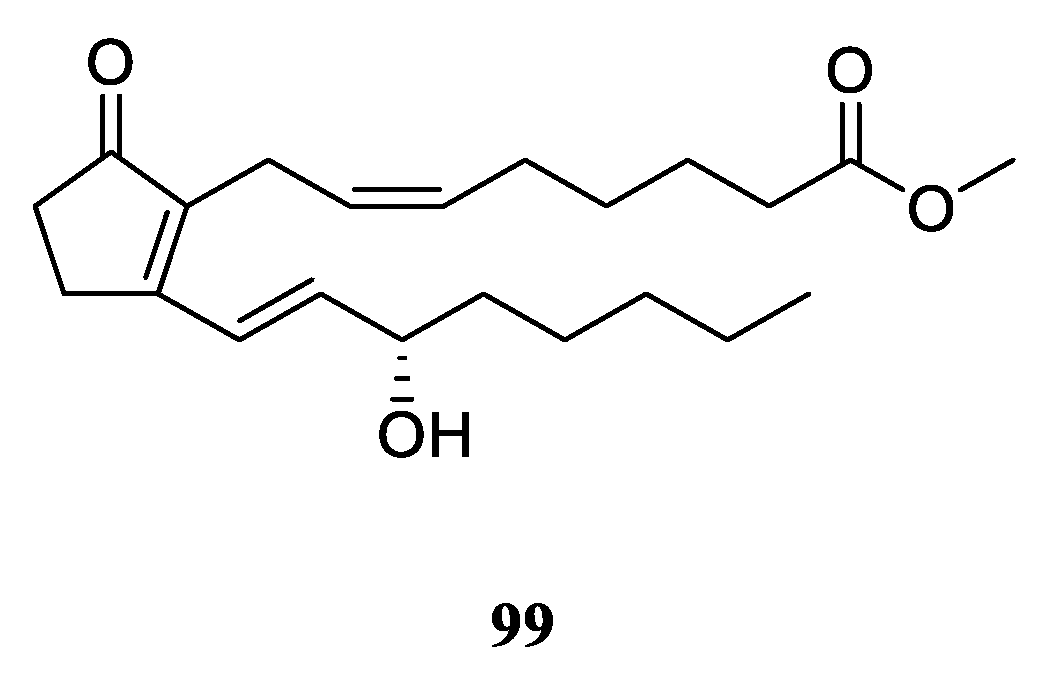

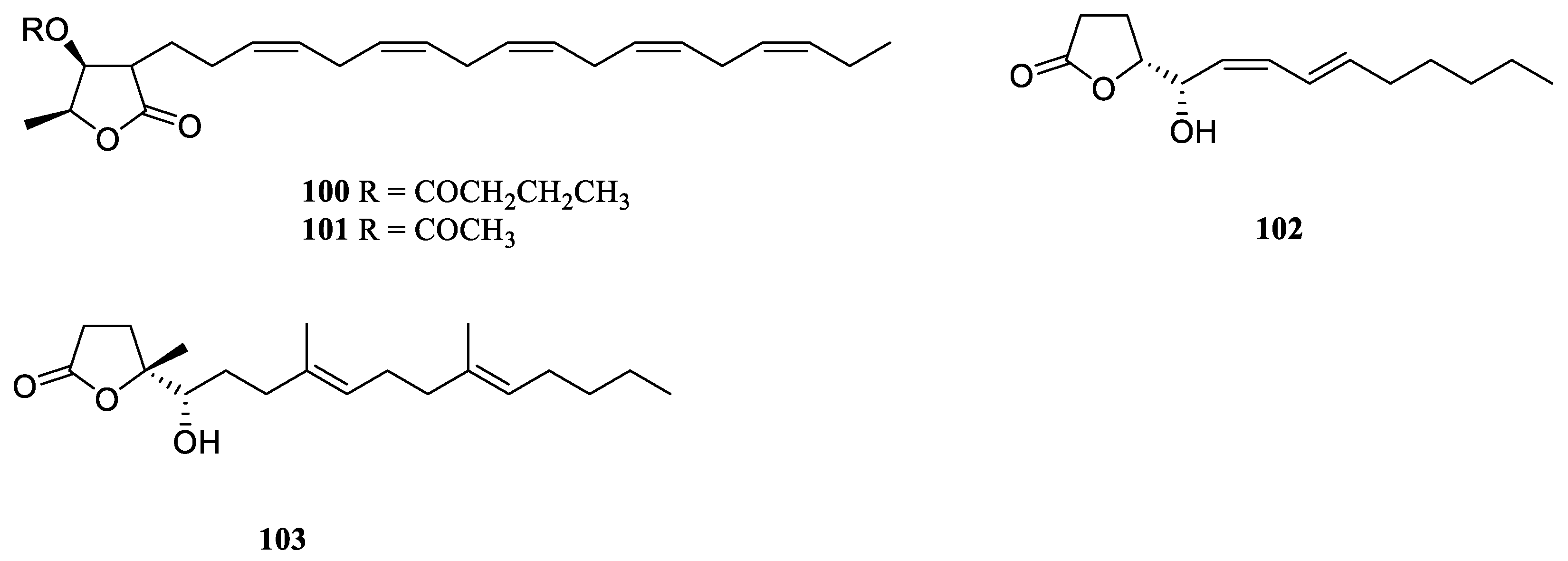

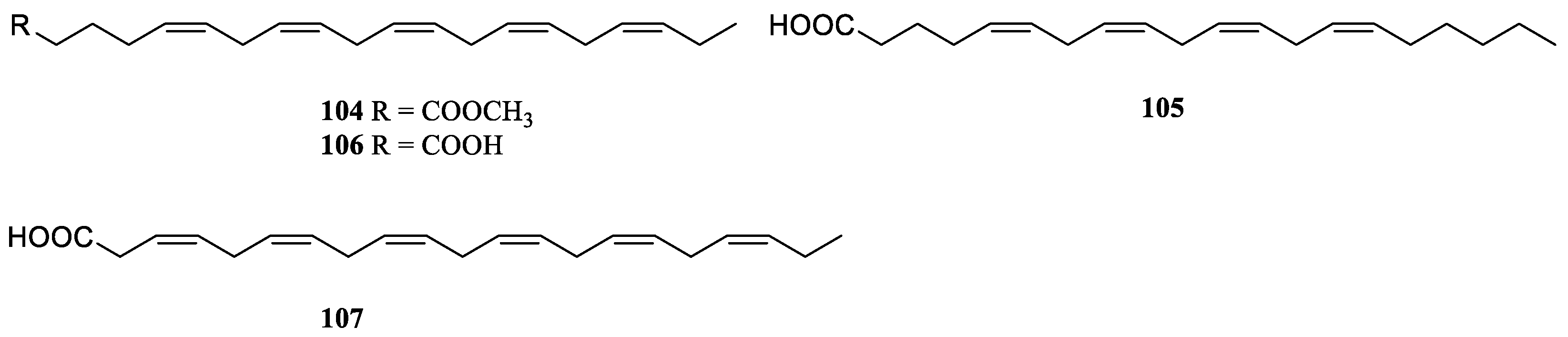

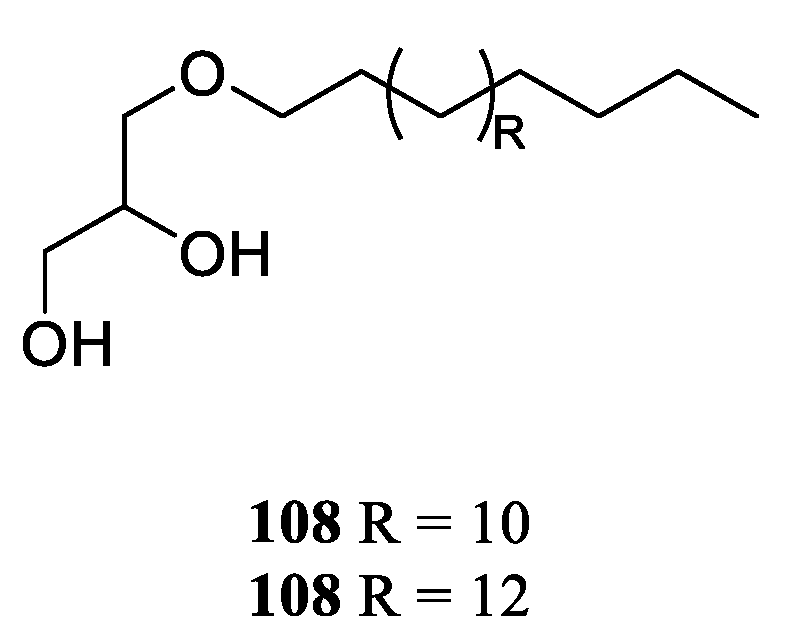

2. Classification of Secondary Metabolites from the Genus Litophyton

Since the first report of a novel cembrane diterpene named 2-hydroxynephtenol from the soft coral

L. viridis in 1975 [

19], many research groups around the world have carried out chemical investigation on the genus

Litophyton, resulting in fruitful achievements. A total of 109 secondary metabolites have been isolated and characterized in the

Litophyton corals during 49 years of research (

Table S1). These chemical compositions can be classified structurally as sesquiterpene, diterpene, tetraterpene, polyhydroxylated steroid, ceramide, nucleotide, prostaglandin,

γ-lactone, fatty acid and glycerol ether. Intriguingly, one uncommon

bis-sesquiterpene was encountered during the research of the alcyonarian

Litophyton nigrum [

23]. In the following subsections, these compounds were further grouped under different catalogs based on structural features. Among them, sesquiterpene and

bis-sesquiterpene-type metabolites were grouped as ‘sesquiterpenes and a related dimer’ according to the corresponding structural relationship. The ceramide and nucleotide-type compounds were put under one category ‘alkaloids’. The pack of ‘lipids’ comprise prostaglandin,

γ-lactone, fatty acid and glycerol ether. Herein, the chemical structures, taxonomical distributions, and biological activities of the reported metabolites from the title genus whenever available were described.

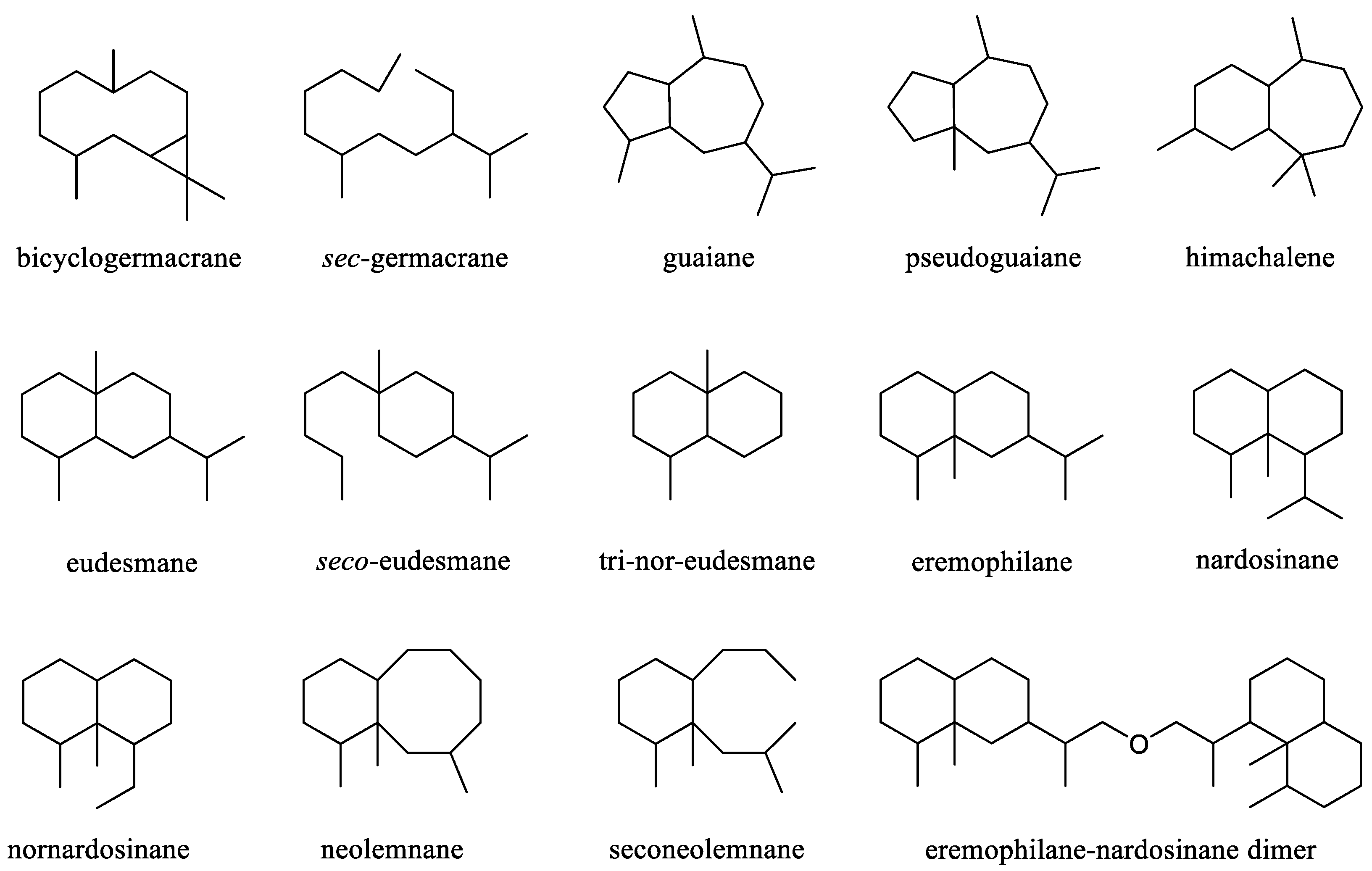

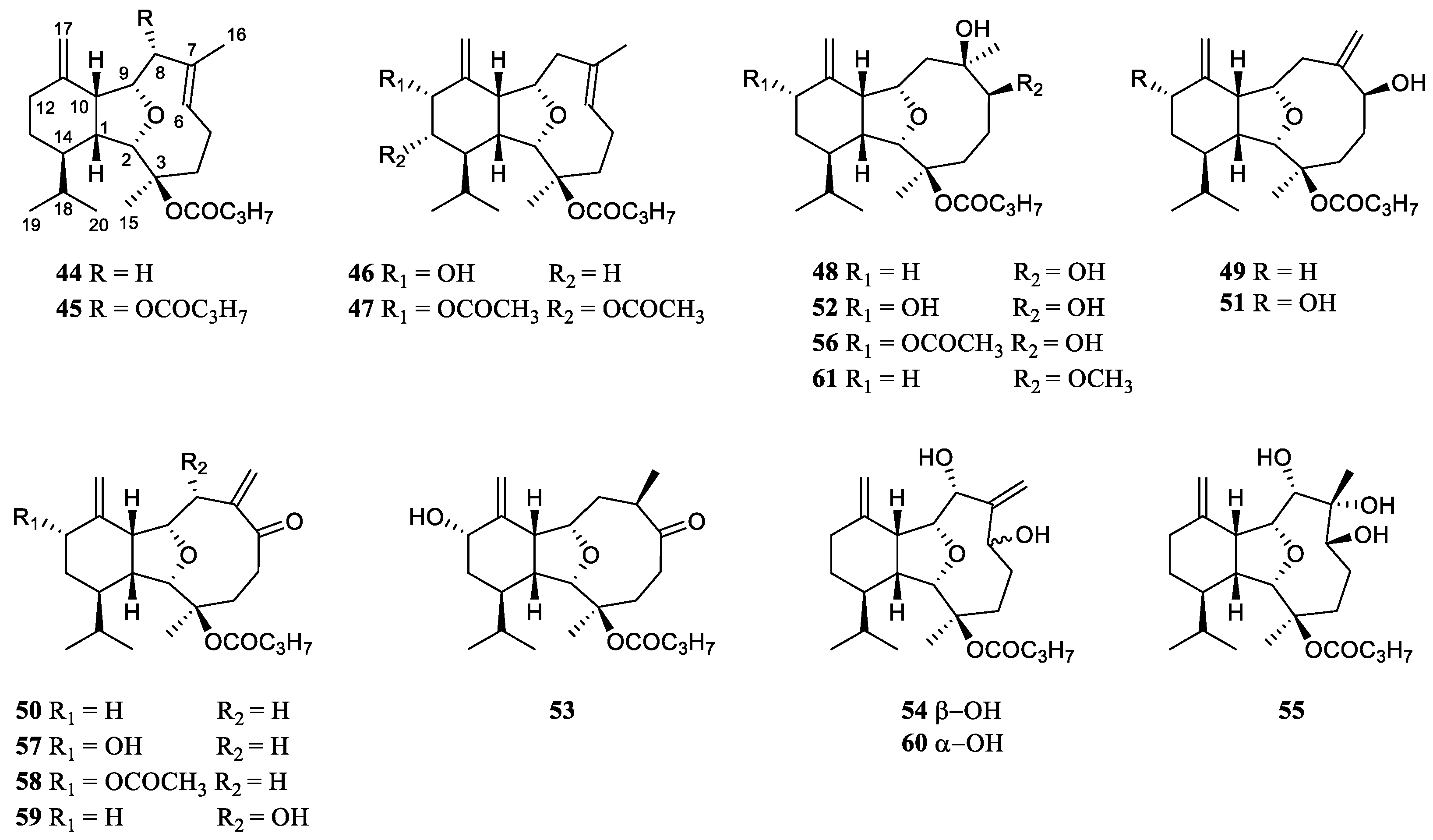

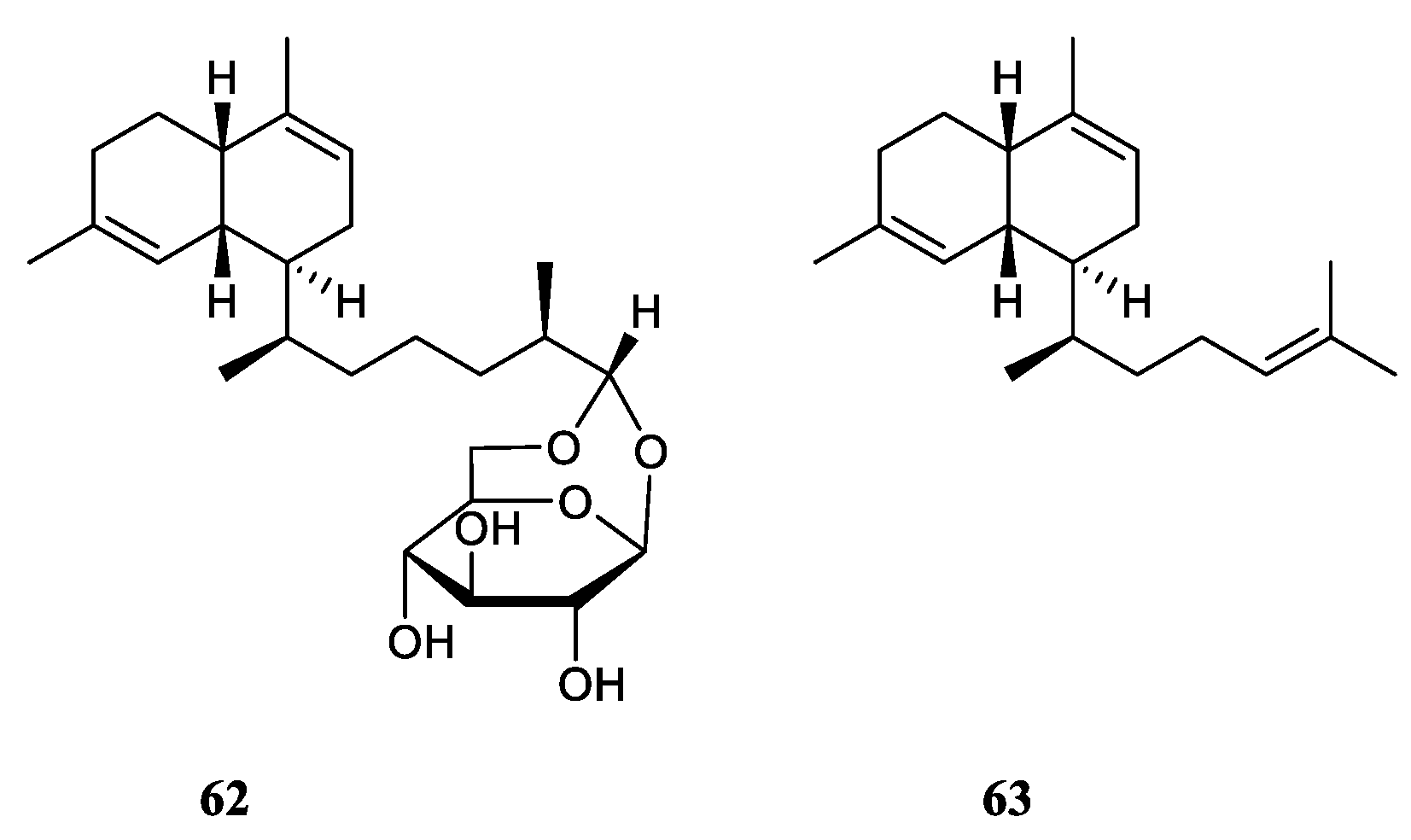

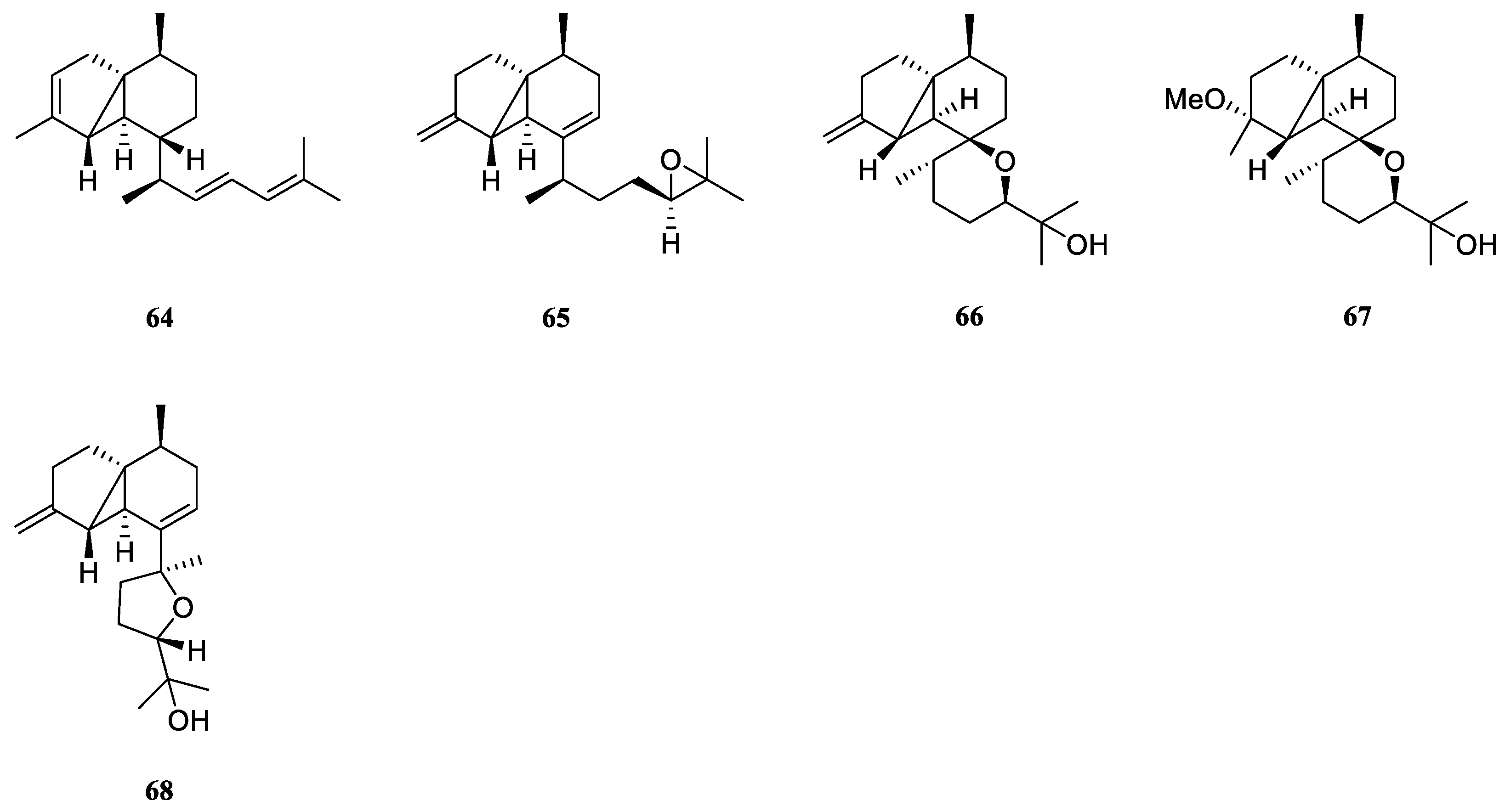

3. Sesquiterpenes and A Related Dimer

This was largest cluster of terpenes obtained from the genus

Litophyton. Since the first sesquiterpene (–)-bicyclogermacrene [

24] was found, more and more efforts were made to search sesquiterpenes from different species of this genus, resulting in an account of 37 compounds. These substances possessed a variety of carbon frameworks, which could be further classified into 15 categories: bicyclogermacrane, s

ec-germacrane, guaiane, pseudoguaiane, himachalene, eudesmane,

seco-eudesmane, tri-nor-eudesmane, eremophilane, nardosinane, nornardosinane, eremophilane, neolemnane, seconeolemnane, and eremophilane-nardosinane dimmer (

Figure 1). These different types of sesquiterpenes distributed in three species

L. arboreum,

L. nigrum and

Litophyton setoensis, which were inhabited in different marine environments including Red Sea, South China Sea and Indonesian water (

Table S1).

Figure 1.

The reported carbon frameworks of sesquiterpenes from the genus Litophyton.

Figure 1.

The reported carbon frameworks of sesquiterpenes from the genus Litophyton.

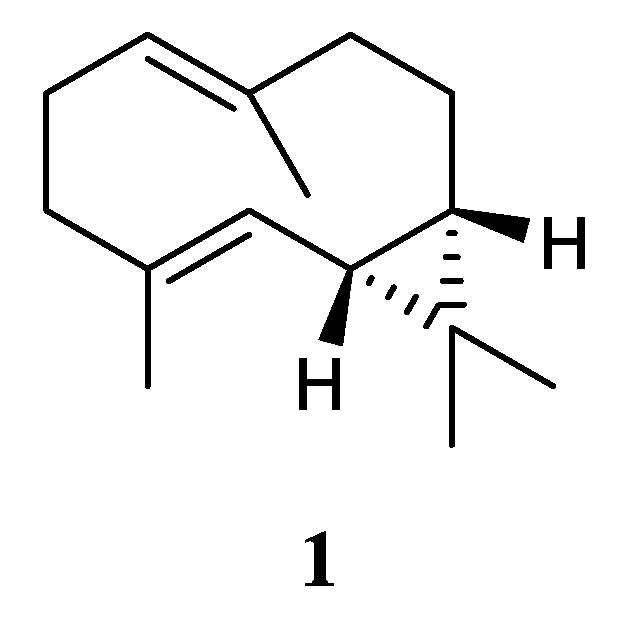

3.1. Bicyclogermacrane Sesquiterpene

Chemical probing of the soft coral

L. arboreum, which was collected near Bali, Indonesia, yielded the sesquiterpene (–)-bicyclogermacrene (

1) [

24] (

Figure 2). This compound exhibited low antiproliferative activities against the cell lines L-929 and K-562 with GI

50 values of 186 and 200 μM, respectively, and low cytotoxic effect against the HeLa cell line with CC

50 of 182 μM.

Figure 2.

The chemical structure of bicyclogermacrane sesquiterpene from the genus Litophyton.

Figure 2.

The chemical structure of bicyclogermacrane sesquiterpene from the genus Litophyton.

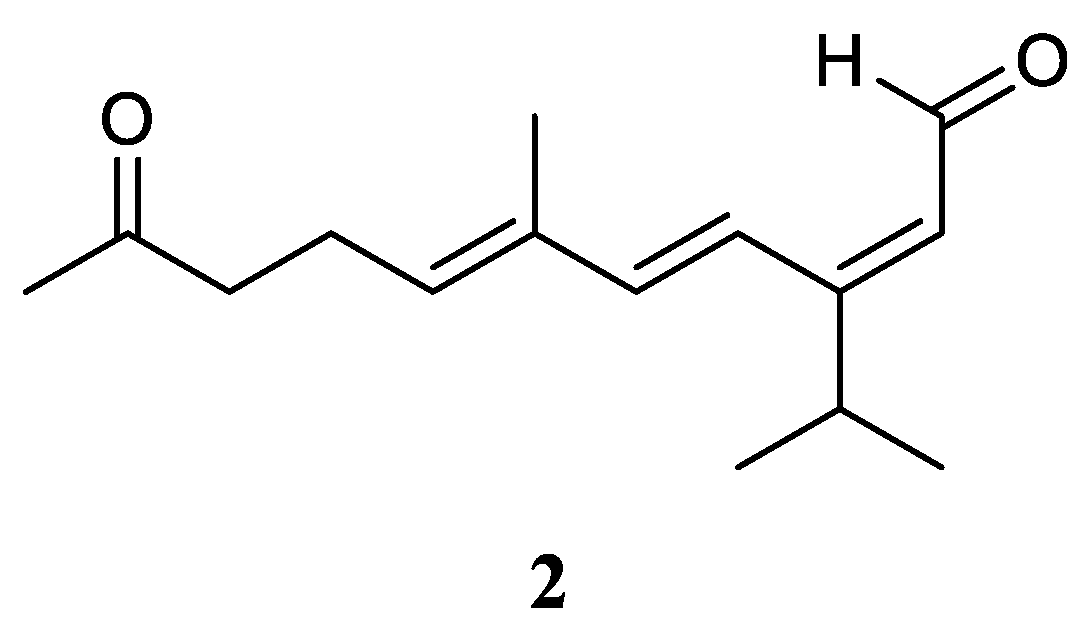

3.2. Sec-germacrane Sesquiterpene

Very recently, Ahmed

et al. [

17] carried out the chemical investigation of the Red Sea specimen

L. arboreum, which was collected at Neweba, Egypt. The acyclic sesquiterpene (2

E,6

E)-3-isopropyl-6-methyl-10-oxoundeca-2,6-dienal (

2) was found from this sample, which possessed a

sec-germacrane nucleus (

Figure 3). Anti-malarial bioassays disclosed the isolate

2 was active against chloroquine-sensitive (D6) and chloroquine-resistant (W2) strains of

Plasmodium falciparum with IC

50 values of 3.7 and 2.2 mg/mL, respectively. In addition, the metabolite

2 was non-toxic to the Vero cell line at the concentration of 4.76 mg/mL. These findings demonstrated that sesquiterpene

2 could be developed as a anti-malarial lead compound with highly safe in the range of tested concentrations.

Figure 3.

The chemical structure of sec-germacrane sesquiterpene from the genus Litophyton.

Figure 3.

The chemical structure of sec-germacrane sesquiterpene from the genus Litophyton.

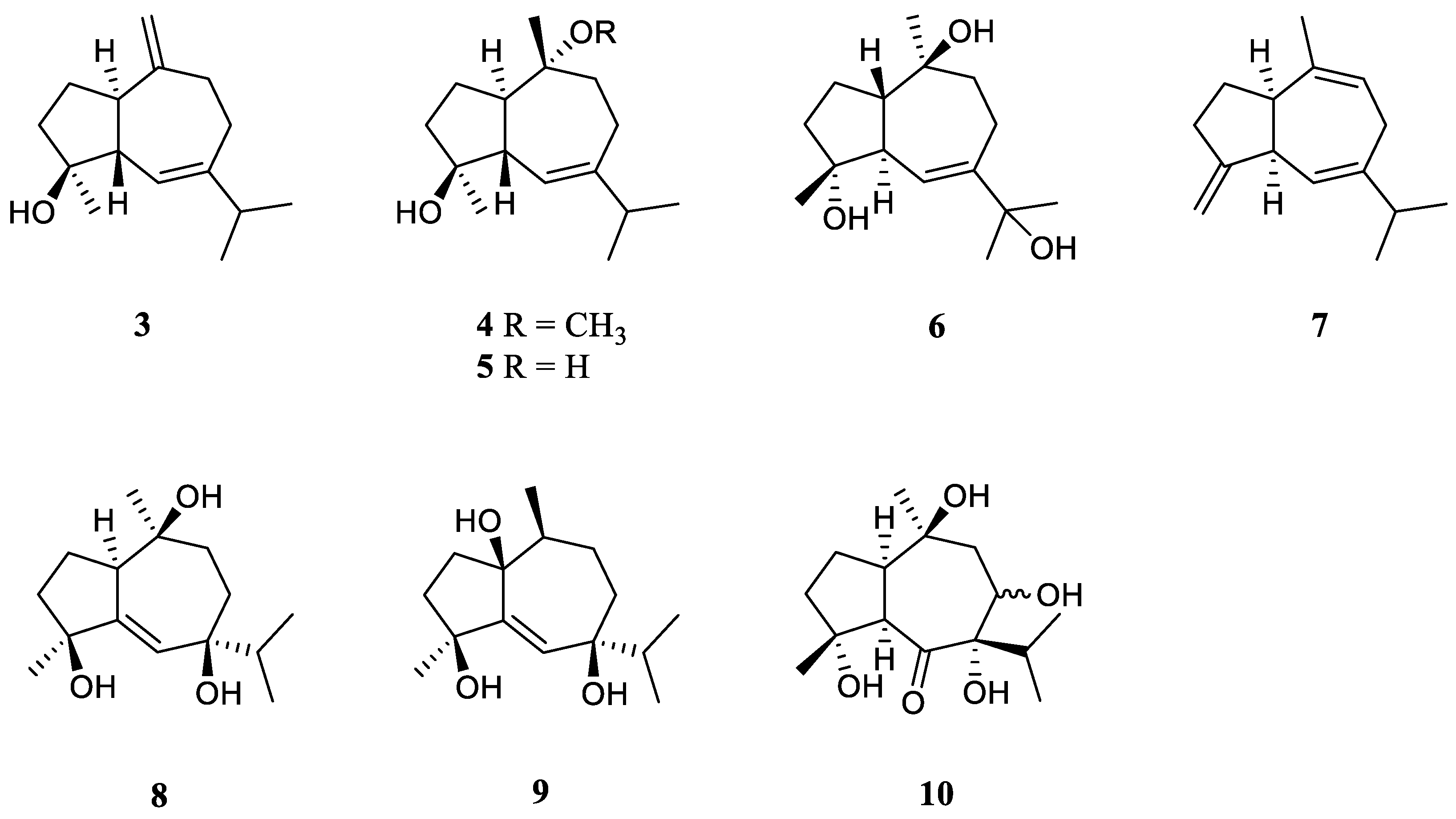

3.3. Guaiane Sesquiterpenes

Interestingly, the guaiane sesquiterpenes were frequently encountered in the Red Sea soft coral L. arboreum.

Bioassay-guided fractionation of the Red Sea alcyonarian

L. arboreum by Ellithey

et al., which was collected at Sharm El-Sheikh, Egypt, yielded three guaiane sesquiterpenes alismol (

3), 10-

O-methyl alismoxide (

4) and alismoxide (

5) [

25] (

Figure 4). Compound

3 showed potent inhibitory activity against HIV-1 protease receptor with IC

50 of 7.2 µM, compared to the positive control, which had IC

50 of 8.5 μM. Molecular docking study disclosed the hydrogen bond between

3 and the amino acid residue of Asp 25 in the hydrophobic receptor pocket with a score of −11.14. Meanwhile, sesquiterpenes

3 and

4 showed moderate cytotoxic activities against the cell lines HeLa (IC

50 30 and 38 μM, respectively) and Vero (IC

50 49 and 49.8 μM, respectively). Morevoer,

4 exhibited moderate cytotoxicity against the U937 cell line with IC

50 of 50 µM. However,

5 was judged as inactive against the above-mentioned cell lines (all IC

50 > 100 µM). In the further study, compounds

2 and

5 demonstrated cytostatic action in HeLa cells, revealing potential use in virostatic cocktails. In Ellithey’s continual study [

26], alismol (

3) showed promising cytotoxic effects against the cancer cell lines HepG2, MDA and A549 (IC

50 4.52, 7.02, and 9.23 μg/mL, respectively).

Hawas’s group reported the presence of alismol (

3) in Red Sea specimen

L. arboreum collected off the coast of Jeddah, Saudi Arabia, together with another guaiane sesquiterpene alismorientol B (

6) [

27] (

Figure 4). These two secondary metabolites were subjected to antimicrobial and cytotoxic bioassays. As a result, metabolites

3 and

6 showed weak to strong antibacterial activities against

Escherichia coli ATCC 10536,

Pseudomonas aeruginosa NTCC 6750,

Bacillus cereus ATCC 9634,

Bacillus subtilis ATCC6633,

Staphylococcus aureus ATCC5141 with MIC values ranging from 10.4 to 1.3 μg/mL. Of which,

6 had significant activity against

B. cereus ATCC 9634 with MIC of 1.3 μg/mL. And they exhibited weak to moderate antifungal activities against

Candida albicans and

Aspergillus niger with MIC values ranging from 10.1 to 6.0 μg/mL. Moreover, they displayed potent cytotoxic effects against the cell lines MCF-7, HCT-116 and HepG2 with IC

50 ranging from 4.32 to 44.52 μM. Of which,

6 showed the most potent cytotoxic effect against MCF-7 cells with IC

50 of 4.32 μM. Additionally, Hawas’s group evaluated the methanolic extract of the above-mentioned soft coral for its

in vivo genotoxicity and antigenotoxicity against the mutagenicity induced by the anticancer drug cyclophosphamide [

18]. The extract was found to be safe and nongenotoxic at 100 mg/kg b. wt. Moreover, the mice group of cyclophosphamide pretreated with the extract (100 mg/kg b. wt.) showed significant reduction in the percentage of chromosomal aberrations induced in bone marrow and mouse spermatocytes.

The existence of alismoxide (

5) was shown in the Egyptian Red Sea

L. arboreum collection from Hurghada by Mahmoud

et al. [

28]. In the anticancer bioassays, sesquiterpene

5 displayed no cytotoxic activities against the cell lines A549, MCF-7 and HepG2 (all IC

50 > 100 µmol/mL). The co-existence of alismol (

3) and alismoxide (

5) as well as an undescribed sesquiterpene, litoarbolide A (

7), and three known analogues 4

α,7

β,10

α-trihydroxyguai-5-ene (

8), leptocladol B (

9) and nephthetetraol (

10) (

Figure 4) in another Egyptian Red Sea

L. arboreum specimen from Neweba, was revealed by Ahmed

et al.’s work [

17]. Viewing from the perspective of their structures, litoarbolide A (

7) was supposed to be the biosynthetic precursor to other sesquiterpenes, which could be generated via further post-translational modifications. The anti-malarial properties of substances

7–

10 were evaluated. However, nly compounds

9 and

10 exhibited anti-malarial activities against chloroquine-resistant

Plasmodium falciparum W2 with IC

50 values of 4.3 and 3.2 mg/mL, respectively.

Figure 4.

The chemical structures of guaiane sesquiterpenes from the genus Litophyton.

Figure 4.

The chemical structures of guaiane sesquiterpenes from the genus Litophyton.

3.4. Pseudoguaiane Sesquiterpenes

A new pseudoguaiane-type sesquiterpene named litopharbol (

11) (

Figure 5) was isolated from the methanolic extract of the Saudi Arabian Red Sea soft coral

L. arboreum by Hawas’s group [

27]. Its structure was determined through the elucidation of NMR data. Compound

11 exhibited a wide spectrum of antibacterial activities against Gram-negative bacteria

E. coli ATCC 10536 and

P. aeruginosa NTCC 6750, as well as Gram-positive bacteria

B. cereus ATCC 9634,

B. subtilis ATCC6633 and

S. aureus ATCC5141 with MIC values ranging from 1.8 to 9.6 μg/mL. Among these bacteria,

11 showed significant activity against

B. cereus ATCC 9634 with MIC of 1.8 μg/mL. And this sesquiterpene exhibited weak antifungal activities against

C. albicans and

A. niger with MIC values of 12.5 and 12.9 μg/mL, respectively. Moreover, it displayed potent cytotoxic effects against cell lines MCF-7, HCT-116 and HepG2 with IC

50 values of 9.42, 26.21 and 38.92 μM. In Hawas’s continual study, litopharbdiol (

12) was identified, which shared the same carbon framework with

11 [

18] (

Figure 5). However, no bioassay for this compound was reported in the article.

Figure 5.

The chemical structures of pseudoguaiane sesquiterpenes from the genus Litophyton.

Figure 5.

The chemical structures of pseudoguaiane sesquiterpenes from the genus Litophyton.

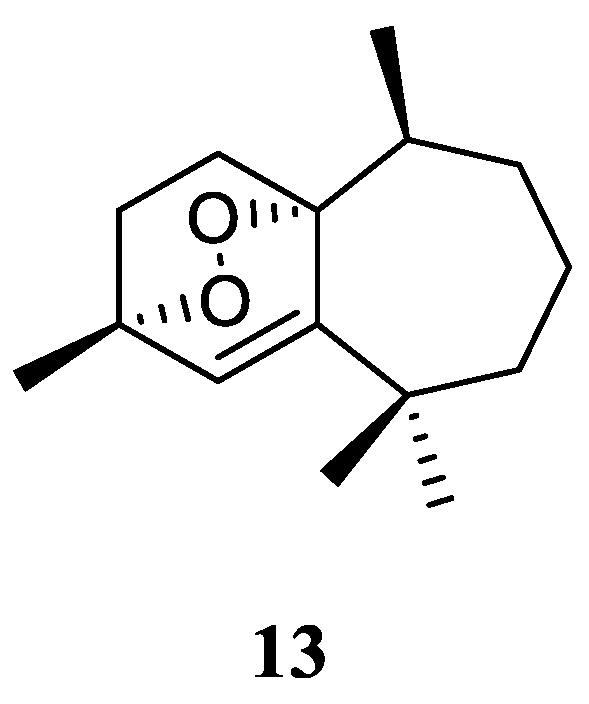

3.5. Himachalene Sesquiterpenes

Purification of the CH

2Cl

2/MeOH extract of Saudi Arabian Red Sea alcyonarian

L. arboreum yielded a new himachalene-type sesquiterpene 3

α,6

α-epidioxyhimachal-1-ene (

13) (

Figure 6), which showed antiproliferative effects toward three different cancer cell lines MCF-7, HCT116 and HepG-2 [

29]. (It might be worth to point out that no specific data of the bioassay results was provided in this article.)

Figure 6.

The chemical structure of himachalene sesquiterpene from the genus Litophyton.

Figure 6.

The chemical structure of himachalene sesquiterpene from the genus Litophyton.

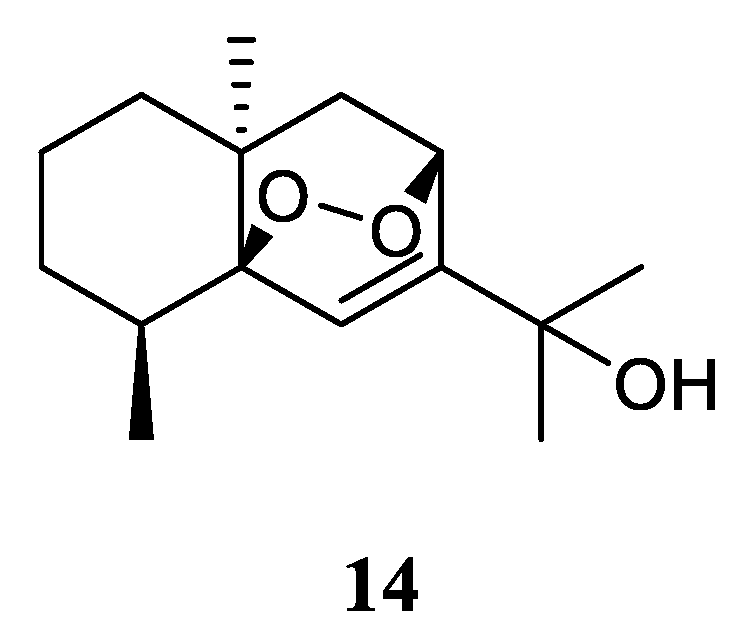

3.6. Eudesmane Sesquiterpene

The

n-hexane-chloroform (1:1) fraction of the Egyptian Red Sea

L. arboreum sample exhibited noticeable cytotoxicity towards A549 cell line (IC

50 22.6 mg/mL) [

28]. The subsequent bioassay-guided isolation yielded a eudesmane sesquiterpene 5

β,8

β-epidioxy-11-hydroxy-6-eudesmene (

14) (

Figure 7). Compound

14 exerted noticeable activity against A549 cell line (IC

50 67.3 µmol/mL) compared to etoposide as standard cytotoxic agent (IC

50 48.3 µmol/mL). However, this compound did not show cytotoxic effects against cell lines MCF-7 and HepG2 (both IC

50 > 100 µmol/mL).

Figure 7.

The chemical structure of eudesmane sesquiterpene from the genus Litophyton.

Figure 7.

The chemical structure of eudesmane sesquiterpene from the genus Litophyton.

3.7. Seco-eudesmane Sesquiterpene

In the above-mentioned study [

28], a

seco-eudesmane sesquiterpene chabrolidione B (

15) (

Figure 8) was co-isolated. However, compound

15 were judged as inactive against the cell lines A549, MCF-7 and HepG2 (all IC

50 > 100 µmol/mL).

Figure 8.

The chemical structure of seco-eudesmane sesquiterpene from the genus Litophyton.

Figure 8.

The chemical structure of seco-eudesmane sesquiterpene from the genus Litophyton.

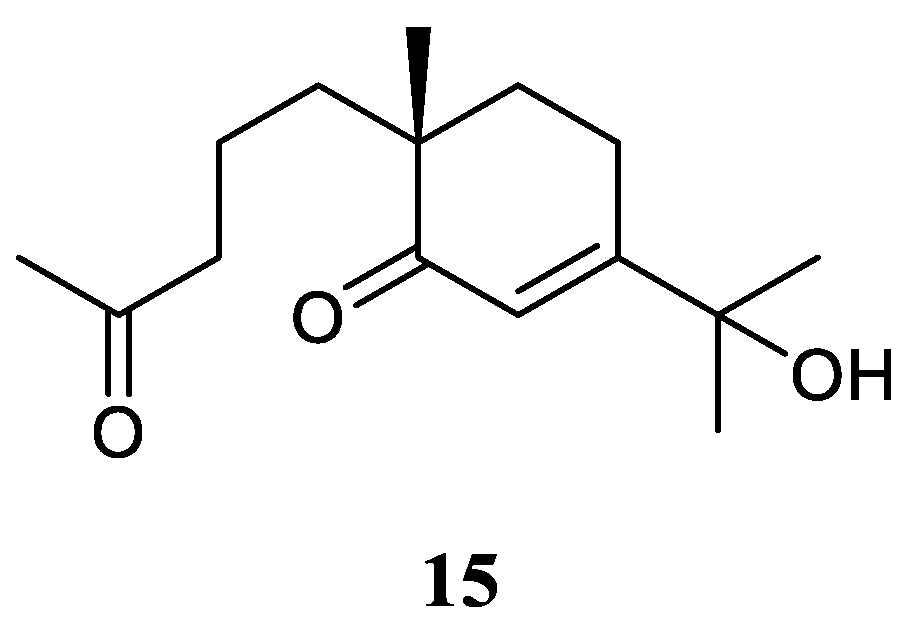

3.8. Tri-nor-eudesmane Sesquiterpenes

The methanolic extract of the Saudi Arabia Red Sea

L. arboreum collection harbored two tri-nor-eudesmane sesquiterpenes teuhetenone A (

16) and calamusin I (

17) [

27] (

Figure 9). Intrestingly, these two nor-sesquiterpenes

16 and

17 displayed a wide spectrum of bioactivities. In the antibacterial bioassays, they showed moderate to strong activities against

E. coli ATCC 10536,

P. aeruginosa NTCC 6750,

B. cereus ATCC 9634,

B. subtilis ATCC6633,

S. aureus ATCC5141 with MIC values ranging from 10.9 to 1.2 μg/mL. Of which,

16 exhibited the most potent activity against

E. coli ATCC 10536 with MIC of 1.9 μg/mL, and

17 displayed the most potent activity against

P. aeruginosa NTCC 6750 with MIC of 1.2 μg/mL. In the antifungal biotests, they exhibited weak to moderate activities against

C. albicans and

A. niger with MIC values ranging from 7.4 to 3.2 μg/mL. In the cytotoxic experiments, they displayed potent cytotoxic effects against cell lines MCF-7 and HepG2 with IC

50 ranging from 6.43 to 39.23 μM. While, the methanolic extract of the Egyptian Red Sea

L. arboreum sample yielded another tri-nor-eudesmane sesquiterpene 7-oxo-tri-nor-eudesm-5-en-4

β-ol (

18) [

28] (

Figure 9). However, this nor-sesquiterpene

18 did not show cytotoxic activities against the cell lines A549, MCF-7 and HepG2 (all IC

50 > 100 µmol/mL).

Figure 9.

The chemical structures of tri-nor-eudesmane sesquiterpenes from the genus Litophyton.

Figure 9.

The chemical structures of tri-nor-eudesmane sesquiterpenes from the genus Litophyton.

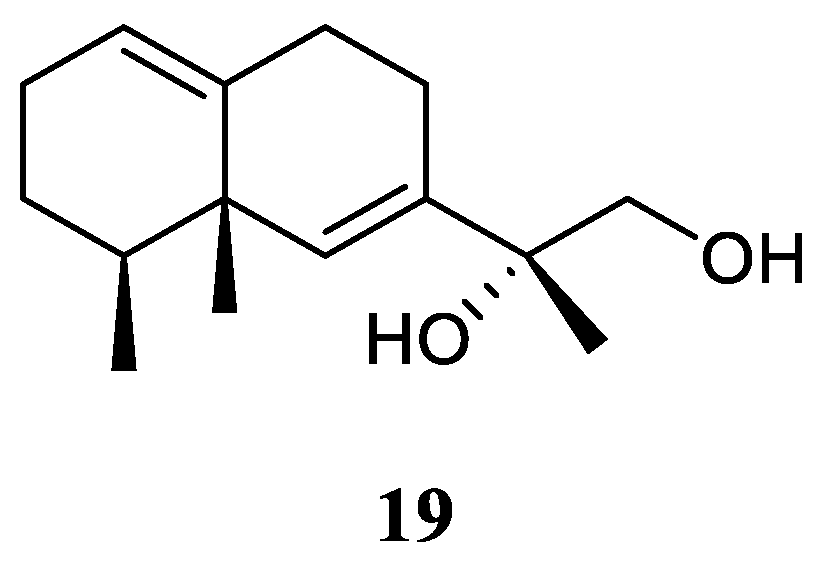

3.9. Eremophilane Sesquiterpene

11,12-Dihydroxy-6,10-eremophiladiene (

19) (

Figure 10) was obtained from the soft coral

Litophyton nigrum, using a structure-oriented HR-MS/MS approach [

23]. This alcyonarian specimen was collected at Xisha Islands, Hainan, China. However, no bioassays were performed due to its scarcity of amounts.

Figure 10.

The chemical structure of eremophilane sesquiterpene from the genus Litophyton.

Figure 10.

The chemical structure of eremophilane sesquiterpene from the genus Litophyton.

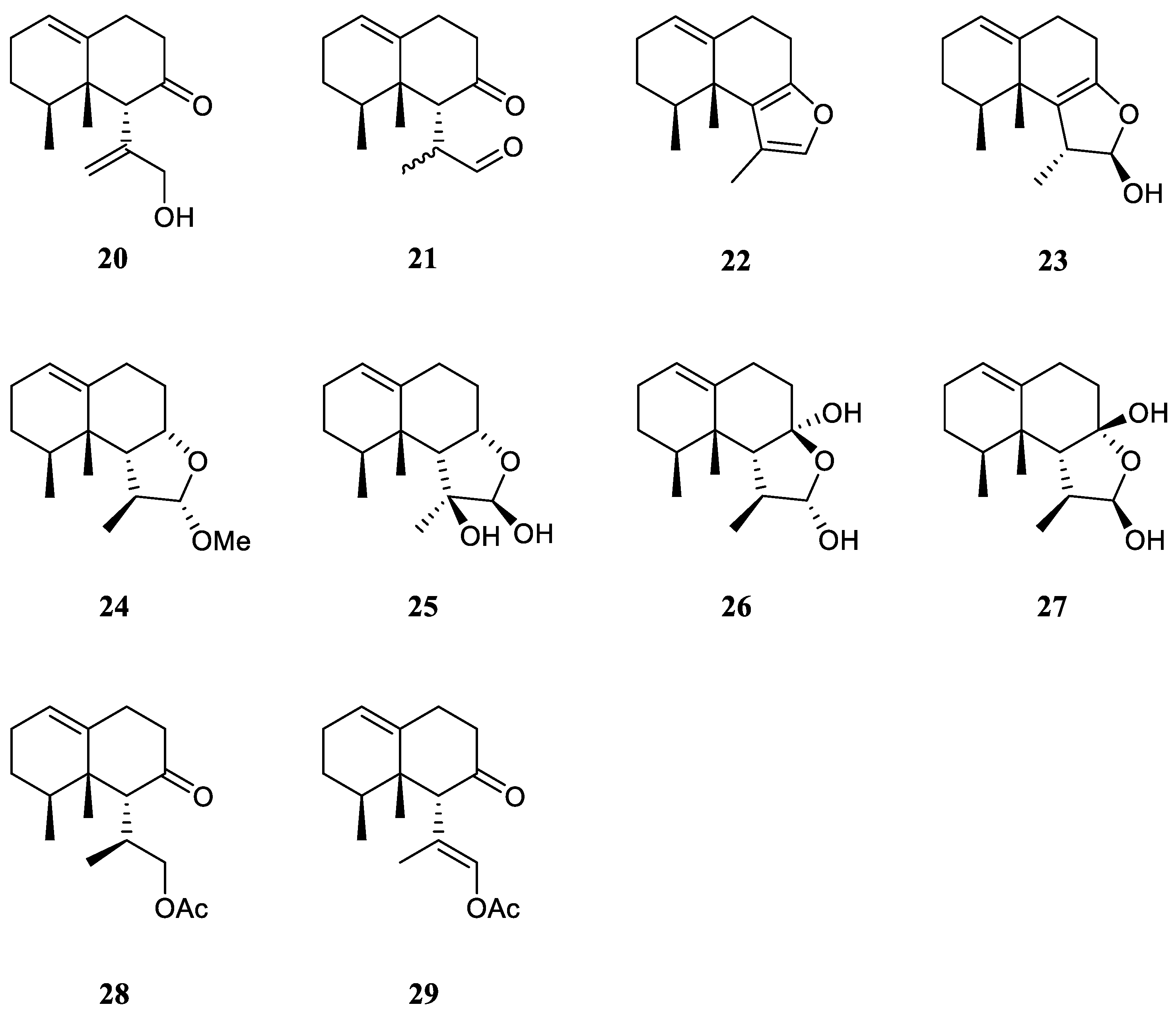

3.10. Nardosinane Sesquiterpenes

Interestingly, the South China Sea soft coral L. nigrum is a rich source of nardosinane sesquiterpenes.

The chemical investigation of the Xisha collection by Yang

et al. afforded two new terpenes linardosinenes B (

20) and C (

21) [

12] (

Figure 11). These two compounds were evaluated for cytotoxities against different cell lines. Sesquiterpene

20 exhibited cytotoxic effect against the THP-1 cell line with IC

50 of 59.49 μM. While compound

21 displayed cytotoxicities against the cell lines SNU-398 and HT-29 with IC

50 of 24.3 and 44.7 μM, respectively. In their continual study on the Xisha sample, four additional new secondary metabolites linardosinenes D–G (

22–

25) (

Figure 11) were obtained [

30]. All metabolites exhibited weak inhibitory effect against bromodomain-containing protein 4 (BRD4), a promising therapeutic target in various human diseases, at a concentration of 10 μM with inhibitory rates ranging from 15.8% to 18.1%.

Using a structure-oriented HR-MS/MS approach, an undescribed sesquiterpene linardosinene I (

26), along with its known 7

β,12

α-epimer lemnal-l(l0)-ene-7

β,12

α-diol (

27) (

Figure 11) were isolated from Xisha alcyonarian

L. nigrum [

23]. The absolute configuration of terpene

27 was determined to be 4

S,5

S,6

R,7

S,11

S,12

S by single crystal X-ray diffraction analysis with Cu K

α radiation [Flack parameter: 0.13(14)]. Sesquiterpene

26 exhibited a potent PTP1B inhibitory activity (IC

50 10.67 μg/mL). It also showed moderate cytotoxic activities against the human tumour cell lines HT-29, Capan-1 and SNU-398 with IC

50 values of 35.48, 42.55, and 25.17 μM, respectively. However, co-isolated metabolite

27 was inactive against PTP1B (IC

50 >20 μg/mL) or cell lines HT-29, Capan-1 and SNU-398 (all IC

50 >50 μM).

Recently, two members of this cluster, paralemnolin J (

28) and (l

S,8

S,8a

S)-

l-[(

E)-2′-acetoxy-l′-methylethenyl]-8,8

a-dimethyl-3,4,6,7,8,8

a-hexahydronaphthalen-2(1

H)-one (

29) (

Figure 11), were isolated in the chemical investigation of a Balinese soft coral

L. setoensis [

15]. In terms of biological activity, cytotoxic effects against several solid tumor and leukemia cell lines HT-29, Capan-1, A549, and SNU-398 were assessed for compounds

28 and

29. As a result, both compounds showed weak cytotoxic activities against the test cell lines (all IC

50 >20 μM).

Figure 11.

The chemical structures of nardosinane sesquiterpenes from the genus Litophyton.

Figure 11.

The chemical structures of nardosinane sesquiterpenes from the genus Litophyton.

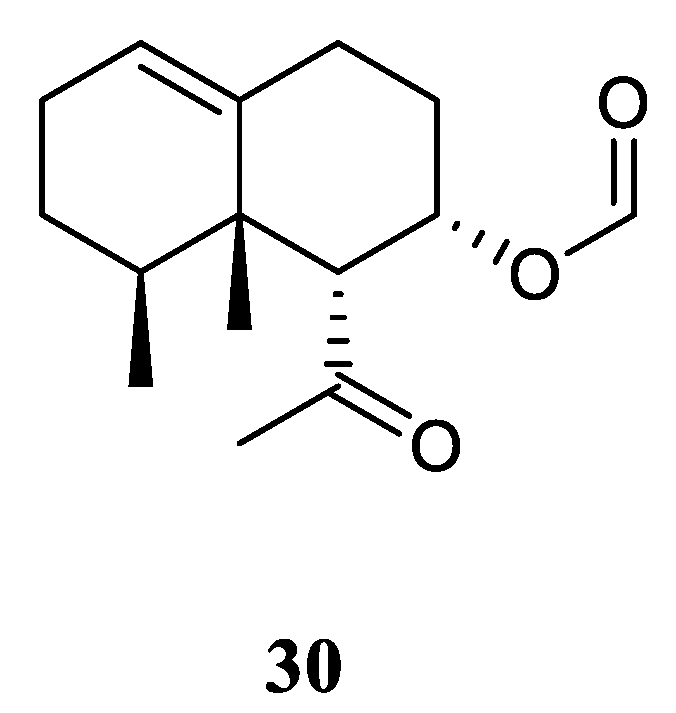

3.11. Nornardosinane Sesquiterpene

Chemical probing of Xisha alcyonarian

L. nigrum afforded an uncommon nornardosinane sesquiterpene linardosinene A (

30) [

12] (

Figure 12). The absolute configuration of

30 was determined by modified Mosher's method and TDDFT ECD approach. This isolate was evaluated for cytotoxicity against the THP-1 cell line and inhibitory activities against the PTP1B, BRD4, HDAC1 and HDAC6 protein kinases. However, it was inactive against the above-mentioned cell line and protein kinases.

Figure 12.

The chemical structure of nornardosinane sesquiterpene from the genus Litophyton.

Figure 12.

The chemical structure of nornardosinane sesquiterpene from the genus Litophyton.

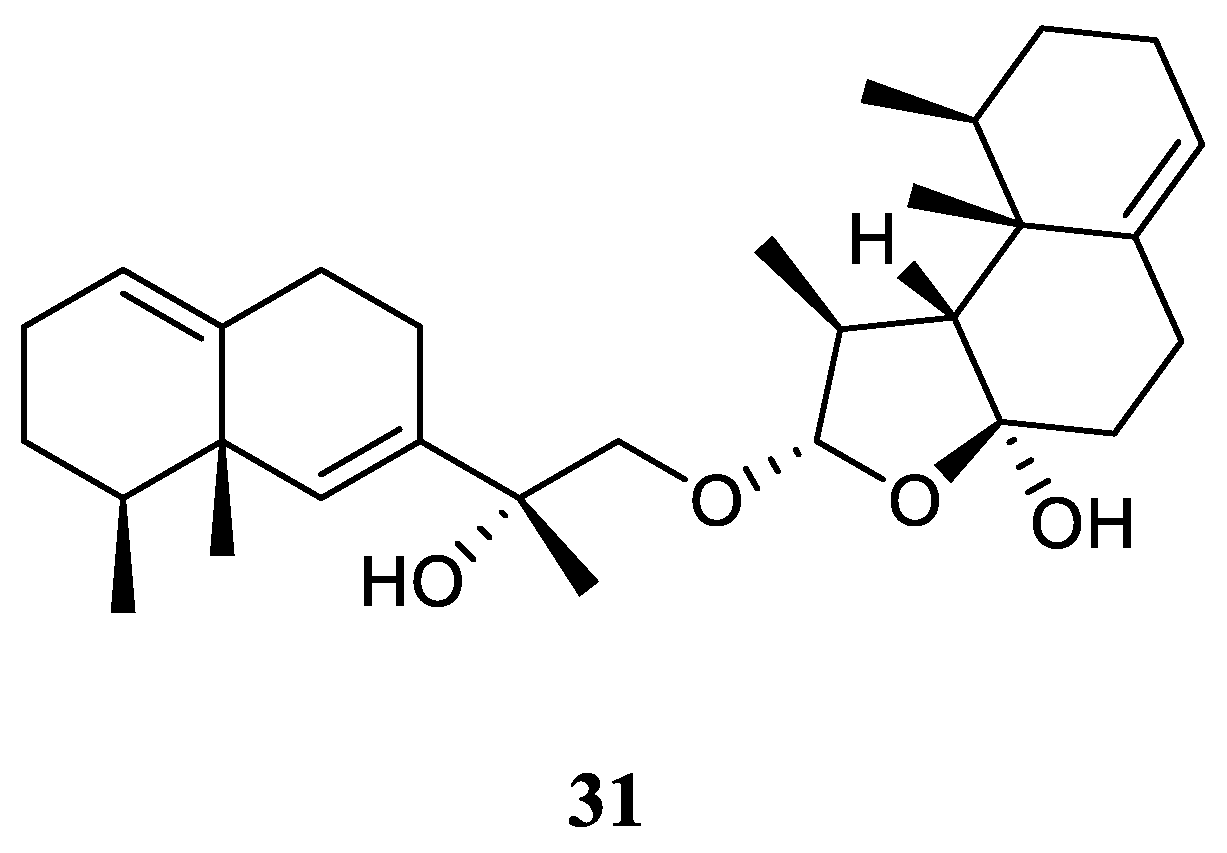

3.12. Eremophilane-Nardosinane Bis-Sesquiterpene

Interestingly, one uncommon sesquiterpe dimer, linardosinene H (

31) (

Figure 13), was found in the soft coral

L. nigrum collected at Xisha Islands, South China Sea, whose structure consisted of a eremophilane sesquiterpene

19 and a nardosinane sesquiterpene

26 [

23]. Contrast to its monomer

26, this bis-sesquiterpene

31 did not exhibit inhibitory activity against PTP1B (IC

50 >20 μg/mL) or the cell lines HT-29, Capan-1, A549, and SNU-398 (all IC

50 >20 μM).

Figure 13.

The chemical structure of eremophilane-nardosinane bis-sesquiterpene from the genus Litophyton.

Figure 13.

The chemical structure of eremophilane-nardosinane bis-sesquiterpene from the genus Litophyton.

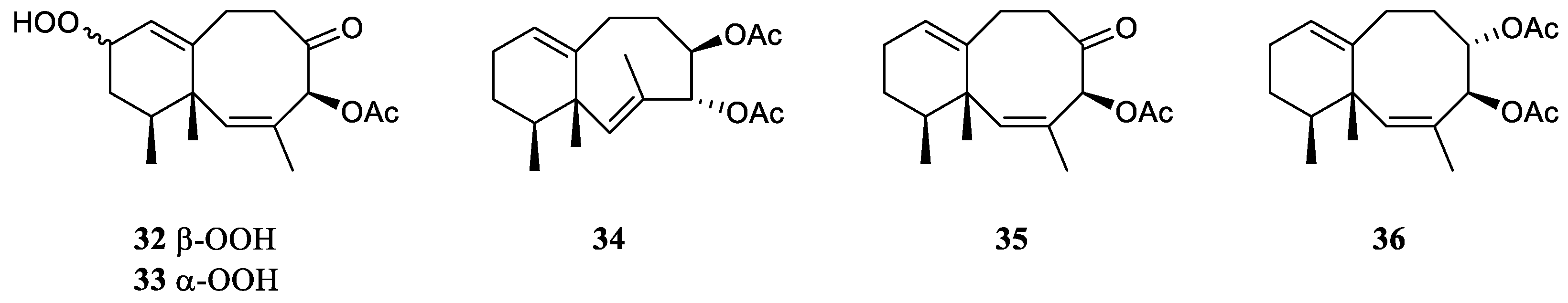

3.13. Neolemnane Sesquiterpene

Study on the chemical constituents of the Chinese soft coral

L. nigrum yielded three new sesquiterpenes lineolemnenes A–C (

32–

34) possessed the neolemnane carbon framework, together with the related known compound 4-acetoxy-2,8-neolemnadien-5-one (

35) [

12] (

Figure 14). It might be worth to point out that the absolute configuration of

35 was unambiguously determined to be 1

S,4

S,12

S by X-ray diffraction analysis for the first time. The cytotoxicities of substances

32 and

33 against SNU-398, HT-29, Capan-1, and A549 were evaluated. It revealed that

32 and

33 only exhibited potent cytotoxic activity against SNU-398 with IC

50 values of 44.4 and 27.6 μM, respectively. And none of them showed potent inhibitory activities against the PTP1B, BRD4, HDAC1 and HDAC6 protein kinases. Compound

35 was also found in the Indonesian soft coral

L. setoensis, together with another sesquiterpene paralemnolin E (

36) [

15] (

Figure 14). They were subjected to cytotoxic bioassays against several solid tumor and leukemia cell lines HT-29, Capan-1, A549, and SNU-398. The results revealed both two compounds had weak cytotoxic activities against the test cell lines (all IC

50 >20 μM).

Figure 14.

The chemical structures of neolemnane sesquiterpenes from the genus Litophyton.

Figure 14.

The chemical structures of neolemnane sesquiterpenes from the genus Litophyton.

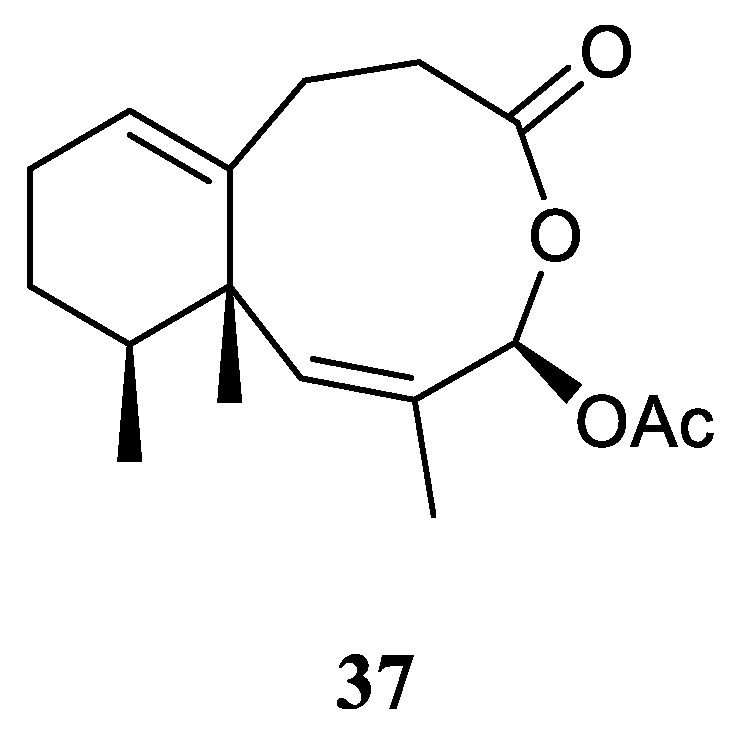

3.14. Seconeolemnane Sesquiterpene

A new sesquiterpene lineolemnene D (

37) (

Figure 15) was isolated and characterized from the Xisha soft coral

L. nigrum [

12]. Structurally, this compound possessed an unusual seconeolemnane skeleton. The absolute configuration of

30 was determined to be 1

S,4

R,12

S by TDDFT ECD approach. Bioassays including cytotoxicity against the THP-1 cell line and inhibitory activities against the PTP1B, BRD4, HDAC1 and HDAC6 protein kinases were performed for this isolate. However, it was judged as inactive in these biotests.

Figure 15.

The chemical structure of seconeolemnane sesquiterpene from the genus Litophyton.

Figure 15.

The chemical structure of seconeolemnane sesquiterpene from the genus Litophyton.

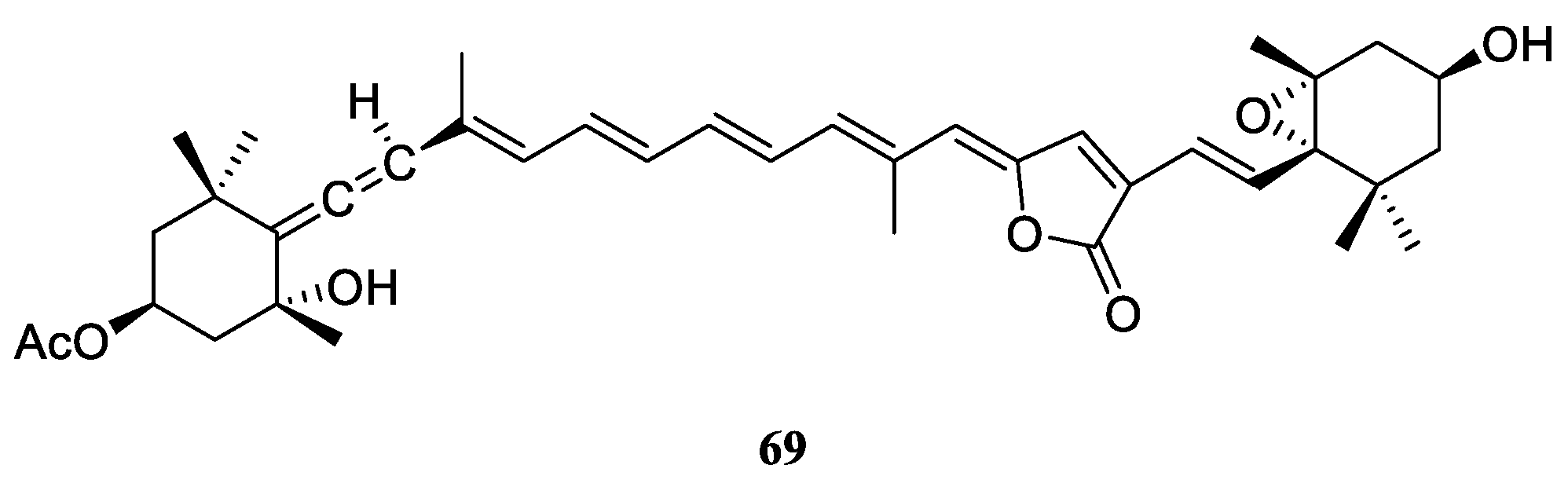

6. Steroids

It seemed the documentation of the steroids from the genus

Litophyton started in 1976, where two 19-hydroxysterols were reported from

L. viridis by Bortolotto

et al. [

39]. Till now, 23 steroids had been obtained from four species, including

L. viridis,

Litophyton mollis,

L. arboreum and unclearly indentified

Litophyton sp. Structurally, ergostanes and 4

α-methylated ergostanes dominated the steroidal profiling of this genus, with three exceptions. The exceptional cases include one stigmastane, one 13,14-

seco steroid, and one 4

α,23-dimethylated ergostane (

Table S1). Considering these, the following presentation of steroids was divided into two categories 4

α-methylated and other miscellaneous steroids.

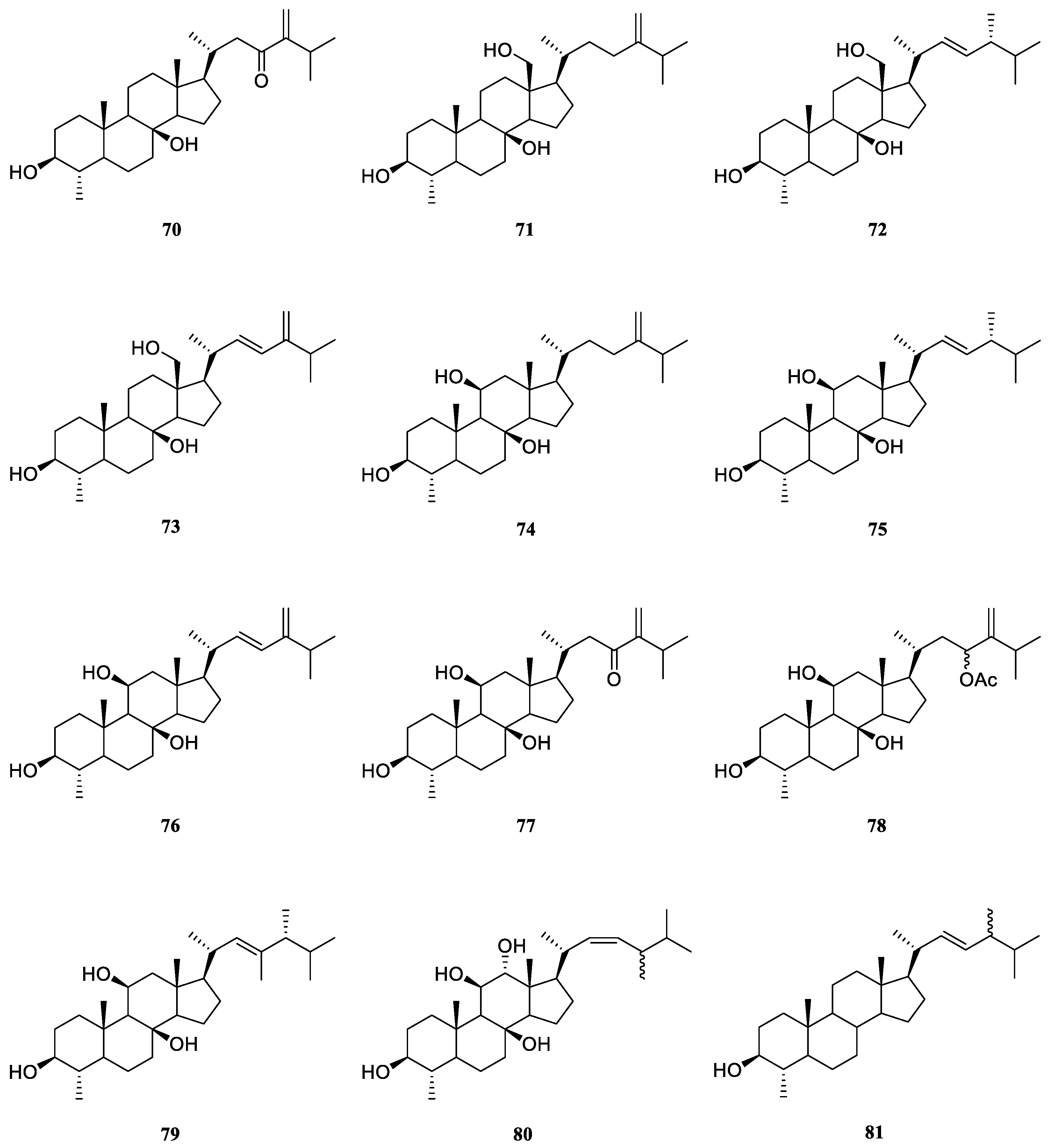

6.1. 4α-Methylated Steroids

Examination of less polar fractions of the extract of the soft coral

L. viridis, which was collected in the Lesser Sunda Islands, led to the isolation of a novel polyoxygenated sterol 4

α-methyl-3

β,8

β-dihydroxy-5

α-ergost-24(28)-en-23-one (

70) [

40] (

Figure 22). The structure and relative configuration of

70 were established unambiguously by X-Ray diffraction analysis on its

p-bromobenzoate derivative.

Končić

et al. conducted the first chemical investigation on the metabolic profile of the Red Sea alcyonarian

L. mollis, resulting in the isolation of ten 4

α-methylated steroids

71–

80 [

41] (

Figure 22). These steroids differed not only in the substitution of hydroxyl groups at steroidal nucleus but also in diverse oxidation of side chains. The absolute configuration of C-24 in compounds

72,

75 and

79 was assigned as

R based on the chemical shift difference between C-26 and C-27 carbon atoms, which was a powerful rule to determine the absolute configuration of steroidal side chains [

42,

43,

44]. The cytotoxic activities of metabolites

71–

79 were evaluated against cell lines K562 and A549 [

41]. As a result, compounds

71 and

75–

78 displayed potent cytotoxicity against K562 cells with IC

50 values ranging from 5.6 to 8.9 μM. Meanwhile, these compounds showed low toxicity against healthy PBMCs, thus denoting interesting differential toxicity. Additionally, the tested steroids exhibited moderate levels of toxicity against A549 cells with IC

50 values around 20 μM, further underlining their antileukemic activity.

The Red Sea soft coral

L. arboreum was frequently encountered by marine natural product chemists. Shaker

et al. found that the Egyptian specimen

L. arboreum harbored 4

α,24-dimethyl-cholest-22

Z-en-3

β-ol (

81) (

Figure 22), the complete assignments of

13C NMR data of which was reported for the first time [

45]. Interestingly, the presence of nebrosteroid M (

74) in another Egyptian sample

L. arboreum had been reported by Mahmoud

et al., which was collected in front of the National Institute of Oceanography and Fisheries at Hurghada province [

28]. It was also found sterol

74 showed cytotoxic effect against A549 cell line (IC

50 36.9 μmol/mL). Moreover, this compound exhibited moderate cytotoxicity against MCF-7 (IC

50 55.3 μmol/mL), but no activity against HepG2 (IC

50 >100 μmol/mL).

Ahmed

et al. also made a Egyptian collection of

L. arboreum from Neweba. Chemical probing of this sample led to isolation of previously reported 4

α-methylated steroids

74,

75 and

79 [

17]. Anti-malarial activities against chloroquine-sensitive (D6) and chloroquine-resistant (W2) strains of

Plasmodium falciparum, together with the cytotoxic effect against the Vero cell line were evaluated for these three isolates. However, they were judged as inactive at the concentration of 4.76 mg/mL in the above-mentioned bioassays.

Figure 22.

The chemical structures of 4α-methylated steroids from the genus Litophyton.

Figure 22.

The chemical structures of 4α-methylated steroids from the genus Litophyton.

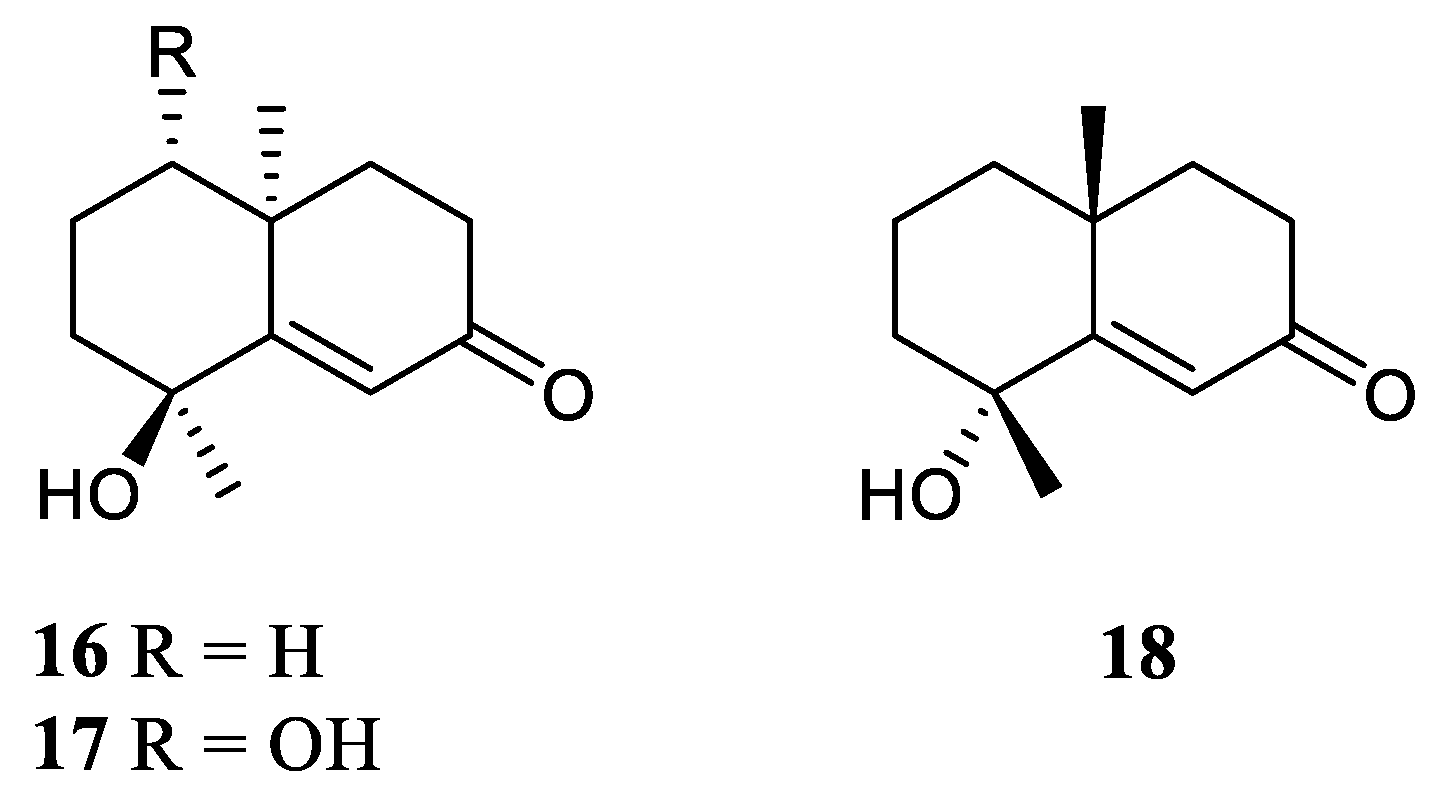

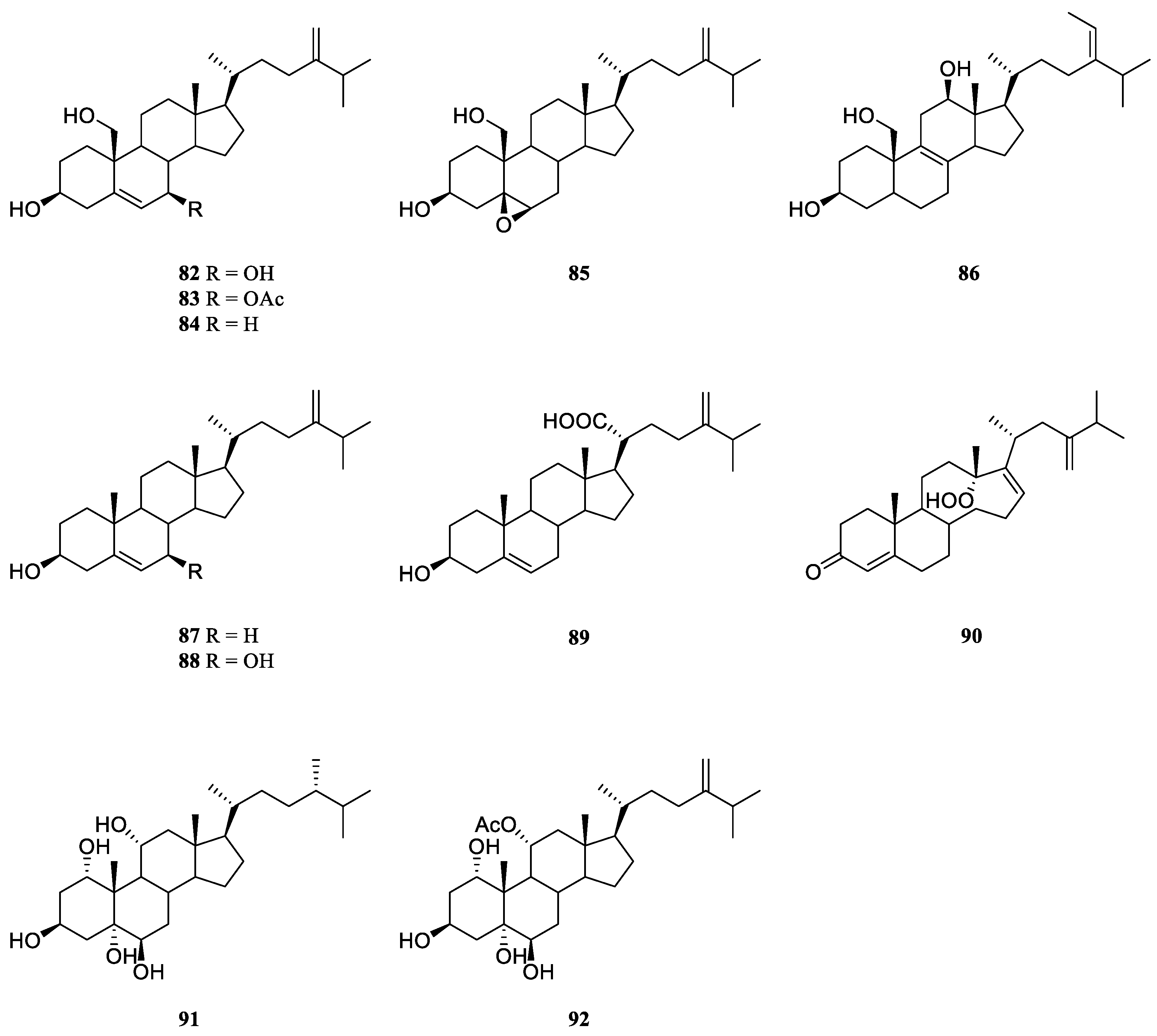

6.2. Other Miscellaneous Steroids

Two novel polyhydroxylated sterols, 24-methylenecholest-5-en-3

β,7

β,19-triol (

82) and its 7-monoacetate derivative (

83) (

Figure 23) were isolated from the soft coral

L.

viridis, collected off Serwaru, Leti Island, Maluku Province, Indonesia [

39]. The structure of

82 had been established by X-ray diffraction analysis [

46]. It was said these two substances were the first instances of naturally occurring 19-hydroxysterols [

39]. More than ten years later, another two new 19-hydroxysterols, litosterol (

84) and 5,6-epoxylitosterol (

85) (

Figure 23), were reported from the Okinawan sample

L.

viridis [

47]. The latter compound showed an antileukemic activity (IC

50 0.5 μg/mL) against leukemia cells P388

in vitro.

Interestingly, 19-hydroxysterols 82 and 83 were widely distributed in the species L. arboreum collected at different waters.

Study on the substances of South China Sea alcyonarian

L. arboreum, which was collected at Xisha Islands, led to the co-isolation of the previously reported sterol

82 and undescribed (24

E)-24-ethyl-5

α-cholesta-8,24(28)-diene-3

β,12

β,19-triol (

86) [

48] (

Figure 23).

Chemical investigation of the Egyptian Red Sea soft coral

L. arboreum by Ellithey

et al., which was collected at Sharm El-Sheikh, revealed the co-existence of three steroids

82,

83 and 24-methylcholesta-5,24(28)-diene-3β-ol (

87) [

25] (

Figure 23). Compounds

82 and

83 demonstrated strong cytotoxicity against HeLa cells (IC

50 8 and 5.3 μM, respectively) and moderate cytotoxicity against U937 cells (IC

50 16.4 and 10.6 μM, respectively). Wheares steroid

87 showed weak cytotoxicity against HeLa cells (IC

50 48 μM) and no potent cytotoxicity against U937 cells (inhibition rates <80%). Moreover, sterol

83 displayed strong inhibitory activity against HIV-1 protease witht IC

50 of 4.85 μM. In Ellithey’s continuous study, sterols

82 and

83 had strong cytotoxic effects against cancer cell lines HepG2 (IC

50 8.5 and 6.07 μg/mL, respectively), MDA (IC

50 5.5 and 6.3 μg/mL, respectively) and A549 (IC

50 9.3 and 5.2 μg/mL, respectively) [

26].

Figure 23.

The chemical structures of other miscellaneous steroids from the genus Litophyton.

Figure 23.

The chemical structures of other miscellaneous steroids from the genus Litophyton.

Co-existence of three known secondary metabolites

82,

84 and

87 in the Egyptian Red Sea collection

L. arboretum from Hurghada was reported by Shaker

et al. [

45]. Recently, study on another Egyptian Red Sea alcyonarian

L. arboreum collected at the same coast by Mahmoud

et al., disclosed the existence of sterol

87, too [

28]. In this study, metabolite

87 exhibited noticeable cytotoxicity against A549 cell line (IC

50 28.5 μmol/mL) and weak cytotoxic activities against both cell lines MCF-7 and HepG2 (IC

50 70.0 and 77.6 μmol/mL, respectively).

Chemical probing of Egyptian Red Sea collection

L. arboreum from Neweba afforded steroids

83,

84, 3

β,7

β-dihydroxy-24-methylenecholesterol (

88), and chabrolosteroid I (

89) [

17] (

Figure 23). Anti-malarial bioassays indicated that compound

88 displayed weak activity against chloroquine-resistant strain

P. falciparum W2 with IC

50 of 4.0 mg/mL, but was inactive against chloroquine-sensitive strain

P. falciparum D6 at the concentration of 4.76 mg/mL.

A novel

seco-steroid 13,14-

seco-22-norergosta-4,24(28)-dien-19-hydroperoxide-3-one (

90) (

Figure 23) together with the known one

83 were found in the chemical investigation of Saudi Arabian Red Sea specimen

L. arboreum by Ghandourah

et al., which was collected from the North of Jeddah coast [

29]. They showed antiproliferative effects toward three different cancer cell lines MCF-7, HCT116 and HepG-2. (It might be worth to point out no specific data was provided in this article.) In addition, Hawas

et al. reported the presence of sterols

82 and

87 in another Saudi Arabian Red Sea sample

L. arboreum [

18].

Extensive studies indicated the methanolic extract of Egyptian Red Sea alcyonarian

Litophyton sp. showed anti-colon cancer therapeutic potential. [

21] The following chromatography resulted in the purification of two polyhydroxylated sterols sarcsteroid F (

91) and 24-methylenecholestane-1α,3β,5α,6β,11α-pentol-11-monoacetate (

92) (

Figure 23).

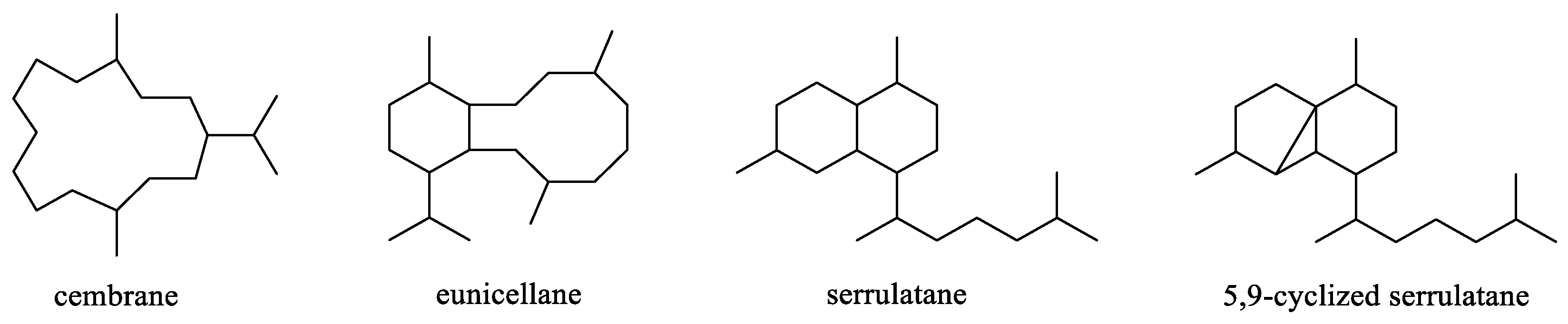

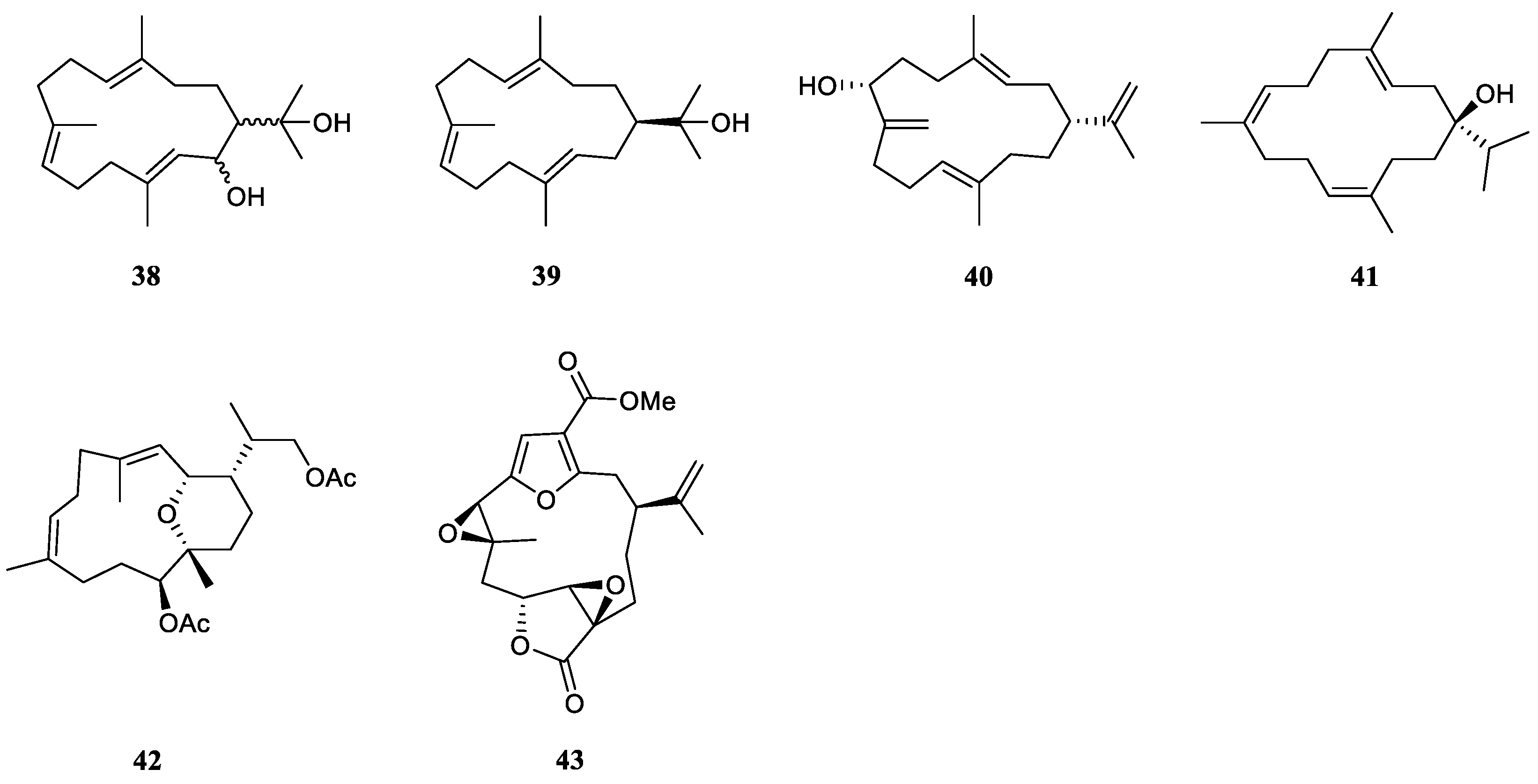

9. Conclusions

The current work presents an up-to-date documentation of the reported studies on the genus

Litophyton with a special focus on their diverse chemical classes of secondary metabolites and their bioactivities. Those investigated soft corals of this genus were inhabited in various marine environments from tropical to temperate regions, especially in the South China Sea, Red Sea, Indonesian and Japanese waters (

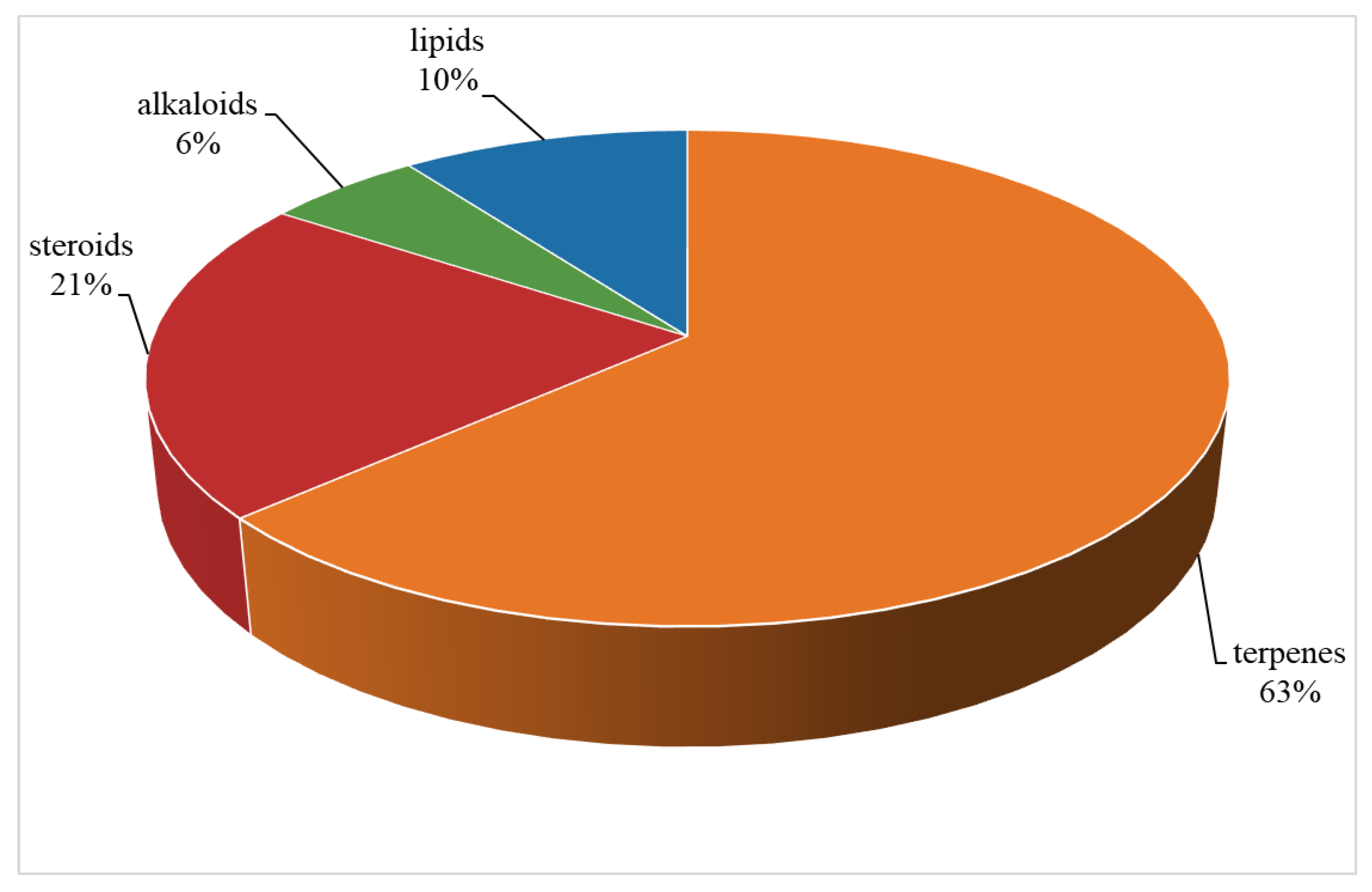

Table S1). A total of 109 compounds from a variety of species of this genus were reported from 1975 to the July, 2023, covering a period of near five decades. These substances illustrated in this work could be categorized as four major chemical classes: terpenes, alkaloids, steroids and lipids (

Figure 30). Among them, terpenes were predominant chemical compositions, which consisted of 36 sesquiterpenes, 31 diterpenes, one bis-sesquiterpene and one tetraterpene (

Table S1). Additionally, the very recently reported one s

ec-germacrane sesquiterpene [

17], one himachalene sesquiterpene [

29], one nornardosinane sesquiterpene [

12], one seconeolemnane sesquiterpene [

12], one eremophilane-nardosinane bis-sesquiterpene [

23], and five 5,9-cyclized serrulatane diterpenes [

15] were quite uncommon marine natural products.

Figure 30.

The chemical profile of secondary metabolites from the genus Litophyton.

Figure 30.

The chemical profile of secondary metabolites from the genus Litophyton.

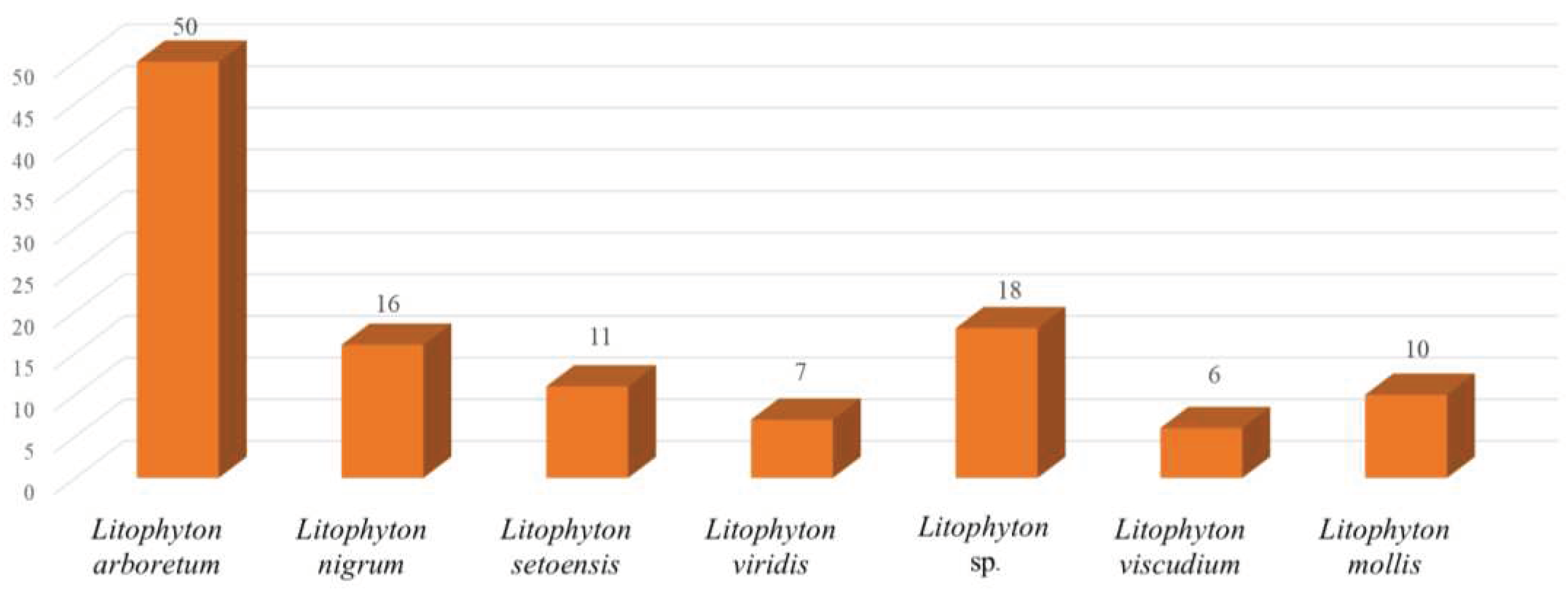

Chemical investigations have been conducted on the species Litophyton arboreum, Litophyton nigrum, Litophyton setoensis, Litophyton viridis, Litophyton viscudium, Litophyton mollis, and unclearly identified Litophyton spp. In terms of the numbers of isolated substances, the animals of L. arboreum were frequently studied members of this genus, yielding 50 compounds (Figure 31). The metabolites of L. arboreum comprised almost structural types of chemical compostions from the title genus, including 18 sesquiterpenes, five diterpenes, one tetraterpene, 12 steroids, two ceramides, four nucleotides, one prostaglandin, two γ-lactones, three fatty acids, and two glycerol ethers (Table S1). Interestingly, bicyclogermacrane, sec-germacrane, guaiane, pseudoguaiane, himachalene, eudesmane, seco-eudesmane, and tri-nor-eudesmane sesquiterpenes were only isolated and characterized from the alcyonarian L. arboreum, which could be regarded as a chemotaxonomic marker for this species (Table S1). Similarly, eremophilane, nornardosinane and seconeolemnane sesquiterpenes, especially a eremophilane-nardosinane bis-sesquiterpene could provide the chemotaxonomic evidence for the species L. nigrum (Table S1). Meanwhile, the chemotaxonomic characters of the species L. setoensis were serrulatane and 5,9-cyclized serrulatane diterpenes (Table S1).

Figure 31.

Number of compounds reported from different species of the genus Litophyton.

Figure 31.

Number of compounds reported from different species of the genus Litophyton.

These metabolites exhibited a wide spectrum of bioactivities including cytotoxic, anti-malarial, antibacterial, antifungal, anti-HIV, antifeedant, molluscicidal, PTP1B inhibitory, and insect growth inhibitory effects (

Table S1). The most frequently evaluated activity for the chemical compositions of the genus

Litophyton was cytotoxicity against a panel of human cancer cell lines, such as HeLa, K-562, HepG2, MDA, A549, MCF-7, HCT116, U937, SUN-398, HT-29, Capan-1, THP-1, HL-60, and P388, and quite a large quantity of the substances showed growth inhibitory activity. Although the molluscicidal activity against the muricid gastropod

D. fragum for eunicellane diterpenes [

36] and toxic activity to brine shrimp

A. salina for

γ-lactones [

50] were performed, more research to better understand the ecological roles of

Litophyton metabolites should be conducted.

As presented in this work, the soft corals of the genus

Litophyton harbor an array of structurally unique and diversely bioactive secondary metabolites. However, only six clearly indentified species have been investigated, which were a very small portion of the whole genus [

11]. It is clear that there is an urgent need for research on exploration of more species of this genus, which are hidden treasure troves of novel marine natural products.

Very recently, coral-encoded terpene cyclase genes that produce the eunicellane and cembrene diterpenes found in soft corals [

52,

53]. Investigation on the biogenesis of chemical compositions of the genus

Litophyton would be another significant and hot research topic in this field. Moreover, the discovery of novel terpene biosynthetic gene clusters could provide potential bioengineering applications for industry.