1. Introduction

Depression is considered a widespread mental health problem around the world. According to The World Health Organization [

1], it is estimated that 3.8% of the world's population suffers from depression, including 5.0% of adults and 5.7% of adults older than 60 years. In other words, depression affects about 280 million people. Depression is diagnosed based on Anhedonia, combined with symptoms that can appear as key symptoms of depression and emotional and neurocognitive symptoms, including suicidal thoughts, insomnia, and agitation [

2].

Anxiety is often described as anxiety, fear, or doubt. Anxiety includes anxiety, fatigue, muscle tension, insomnia, and difficulty concentrating [

3]. Moreover, depression and anxiety symptoms are very closely related, and it is known that the co-existence rate diagnosed simultaneously is high. About 85% of patients with depression experience significant anxiety symptoms, while 90% of patients with anxiety disorders are also reported to suffer from depression [

4]. Since the coexistence of these two diseases increases the risk of suicide, the treatment and preventive management of depression and anxiety are crucial for public health.

The treatment of patients with depression consists of medication and non-pharmacological treatments. Medication for patients with depression includes selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRI), serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors (SNRI), tricyclic agents, benzodiazepine, and prevaline [

5]. Among all treatment options, medication is maintained at the first line [

6]. However, long-term side effects of antidepressants can negatively affect daily life due to gastrointestinal symptoms, neurological symptoms, and sexual dysfunction, limiting the excessive use of medication [

7]. On the other hand, non-pharmacological treatment consists of cognitive behavioral therapy, psychotherapy, and mindfulness-based therapy [

8]. Forest healing is in the spotlight as non-pharmacological interventions.

Forest healing is an activity that improves mental and physical health by utilizing various elements of the forest, such as landscape, sound, and phytoncide [

9]. It has been scientifically proven that forest healing provides beneficial benefits for human psychological and physiological health [

10,

11,

12]. Forest healing is recommended as a form of low-cost preventive medicine that is safe and has no side effects [

13]. When exposed to forest environments, people unconsciously feel free and comfortable, and their minds are boosted and energized. The forest healing program is a program that combines various activities such as exercise, walking, breathing, and play activities using forest environmental factors to maximize the healing effect of the forest [

14]. Many previous studies have reported the positive effects of forest healing programs on mental health, such as reducing psychological stress or mental fatigue [

15,

16]. Among them, studies on the clinical effects of forest healing to improve depression and anxiety have been reported. For example, Chun et al. [

17] documented that the three-night, four-day forest healing program conducted on 92 Chronic alcoholics improved subjects' depressive symptoms and anxiety. In addition, Choi et al. [

18] showed that the eight sessions of a forest healing program for cancer patients reduce depression in cancer patients more than in daily activities. Kim et al. [

19] also indicated that the 3-day forest healing program reduced depression and anxiety compared to daily activities. Lim et al. [

20] showed that the 11 sessions of forest healing program conducted on 64 older people aged 65 or older significantly improved the depression of the elderly. Han et al. [

21] proposed that the one-night, two-day forest healing program conducted on 61 workers reduced the depressive symptoms of workers. In addition, previous meta-analyses evaluating the impact of forest healing on depression and anxiety confirmed forest healing is a very effective intervention in improving depression and anxiety [

22,

23,

24].

However, although many studies have contented that forest healing reduces subjects' depression and anxiety, previous studies are insufficient to reveal a direct link between forest healing and depression. This is because existing studies have evaluated the effectiveness of forest healing on depressive patients without clinical experts such as psychiatrists, making clinical judgment difficult. In addition, most studies were conducted on cancer or alcoholics patients, not depression patients, but on disease groups and healthy people. In addition, it has been conducted in deep forests, which are located far from cities and may be less accessible and less sustainable. Therefore, this study was conducted to determine whether the forest healing program could help alleviate anxiety and depression symptoms in depressive disorders.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Area

We conducted this study in Seoul Forest. The Seoul Forest is placed in Seondong-gu, Seoul Metropolitan City, Republic of Korea (

Figure 1). With a total area is 1,156,498 square meters, it is the third largest urban park in Seoul after Mapo-gu World Cup Park (3,305,785 square meters) and Songpa-gu Olympic Park (1,652,892 square meters). The Seoul Forest consists of four distinctive spaces: a culture and art park, an experiential learning center, an ecological forest, and a wetland ecological center, and it is in contact with the Han River, providing various cultural leisure spaces. The forest tree species are mainly composed of conifer (such as

Pinus strobus, Ginkgo biloba, Pinus densiflora, Metasequoia glyptostroboides) and broadleaf trees such as

Zelkova serrata,

Prunus serrulate, Cercidiphyllum japonicum, Malus Pumila Crataegus pinnatifida. The weather during the periods of the experiment was sunny, and the average temperature was 21.9 °C.

2.2. Subjects

A sample size calculation using G*Power 3.1 (University of Düsseldorf, Düsseldorf, Germany) resulted in 52 subjects. We added three more subjects to ensure potential dropouts would not reduce the sample size. The total sample size consisted of 55 subjects in this study. Subjects were recruited from four specialized mental health medical clinics in Seoul, Republic of Korea. Experienced psychiatrists within the mental health medical clinic informed the visiting depression patients about this study. Overall, sixty subjects participated in March to April 2022. Subjects were eligible for inclusion if they were (a) diagnosed with mild depressive disorder by psychiatrists in accordance with DSM-5 and identified through a structured clinical interview (SCID) for DSM disorders in Korean version, (b) age 20 to 60 years, and (c) patients with possible outdoor activities of more than 2 hours. In contrast, exclusion criteria were (a) person who has participated in a program similar to this forest healing program within the last three months and (b) having a history of being allergic to forests can exacerbate discomfort or difficulty in activities due to double diseases.

Fifty-five subjects were recruited for the study, but five subjects dropped out due to personal problems. So, fifty initial subjects were randomly assigned to the urban forest healing program (25 subjects) and outpatient control group (25 subjects). During experiments, three subjects were suspended from the urban forest healing program group for health reasons and personal reasons, and no subjects were eliminated in the control group. Therefore, the urban forest healing program group that completed this study was 22 subjects, including seven men and 15 women, with an average age of 37.8 ± 10.3 years old. The outpatient control group consisted of 25 subjects, one man and 24 women, and the average age was 38.9 ± 10.5 years. All subjects were explained the study’s purpose and procedures before the experiment.

The study has been approved by the Institutional Review Board of Chungbuk National University (CBNU-202203-HR-0041). We obtained written informed consent from all subjects and provided USD 200.00 compensation for the subjects in this study.

2.3. Design

This study is designed as a randomized controlled clinical trial in which individual experimental group (Urban Forest Healing Program) will be compared to control group (Treatment as usual). Randomization was executed per subjects by computer random number generator. We have created a list of random numbers from minimum 1 to maximum 50. The experimental group was assigned an odd number, and the control group was assigned an even number. A total of 50 subjects were randomly allocated to the experimental group (Urban Forest Healing Program) and the control group (Treatment as usual), with an allocation ratio of 1:1. The experiment was conducted between 10 a.m. and 12 p.m. from May 12 to June 18, 2022.

2.4. Study procedure

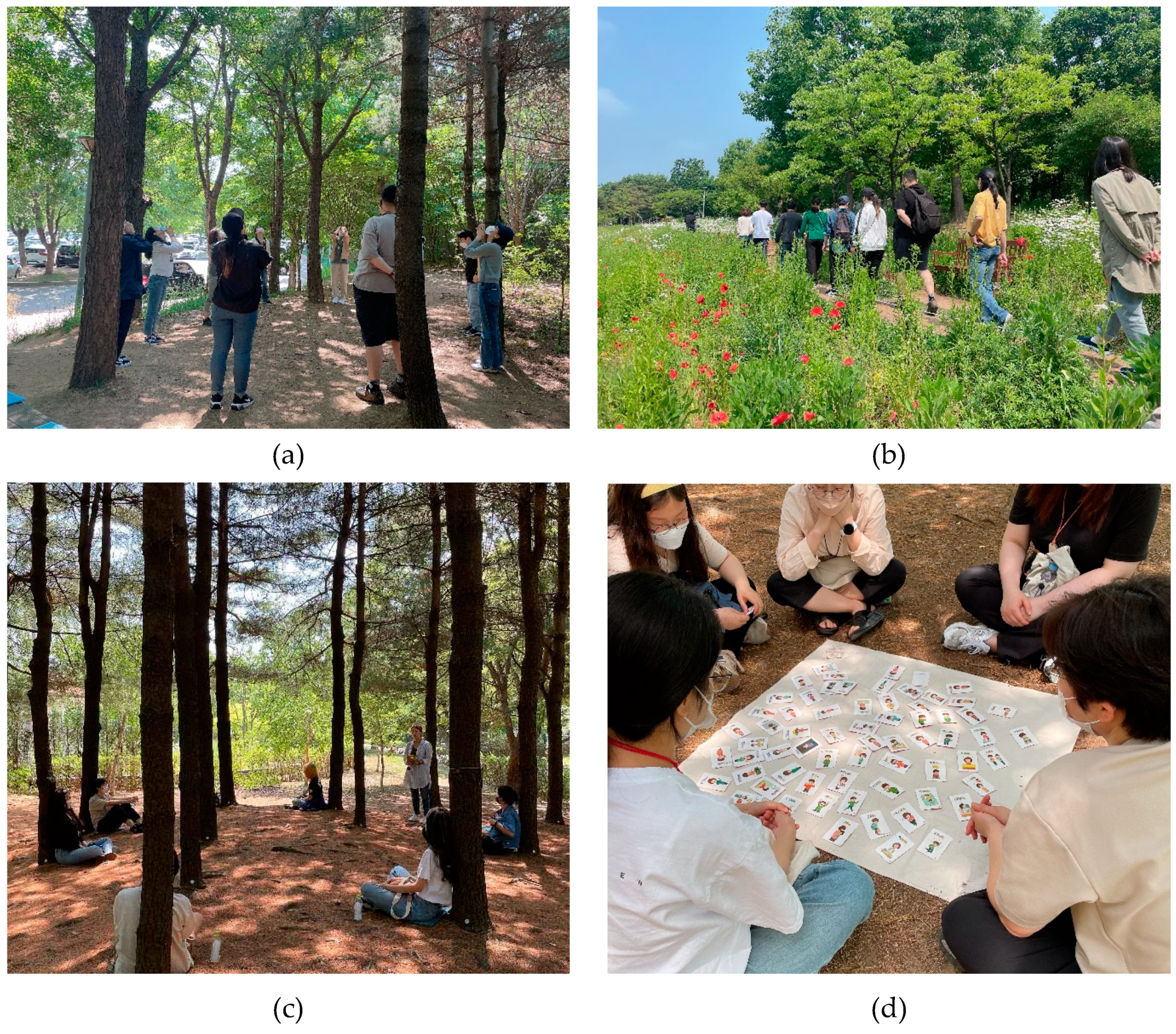

The experimental intervention was a structured forest healing program in urban forests (

Figure 2). All urban forest healing programs were provided by licensed forest healing therapists. Licensed forest healing instructors and two psychiatrists developed the urban forest healing program. In addition, counselors participated in the implementation of the program. It consists of six weekly sessions of 90 minutes. The intervention aims to reduce depressive and anxiety symptoms in adults with a depressive disorder. The modules of the core forest healing program are divided into three stages. The first step (first and second sessions) aimed to explore and clarify my feelings as a ‘recognition’ stage. The second step (third and fourth sessions) aimed to experience negative stops of thought through various activities in the urban forest as an ‘action’ stage. The third step (fifth and sixth sessions) aimed to induce a break in the ring of ruminative thinking in the ‘change’ stages as the last step. We aimed to ultimately improve the lifestyle of depressed patients by repeatedly learning the activities of stretching exercise, walking on the five senses (sense of sight, sound, smell, taste, and touch), emotional card play game, and breathing and meditation, step by step, and practicing them in daily life.

On the other hand, subjects in the control group did not receive any forest healing activities during the experiment and received treatment as usual. Treatment included medication and counseling as usual, and all subjects were continuously managed by a general physician. All subjects were maintained according to each patient's previous treatment schedule for six weeks.

2.5. Measurements

The psychological evaluations used the Montgomery-Asberg depression rating scale (MADRS), the Hamilton Anxiety Rating Scale (HARS), and the State-Trait Anxiety Inventory (STAI) questionnaires. The MADRS was developed by Montgomery and Åsberg [

25] and was a clinician-rated measure of depression severity. It consists of the following 10 items: (1) apparent sadness; (2) reported sadness; (3) inner tension; (4) reduced sleep; (5) reduced appetite; (6) concentration difficulties; (7) lassitude; (8) inability to feel; (9) pessimistic thoughts; and (10) suicidal thoughts. These items are clinician-rated on a seven-point Likert scale and are summed to produce a total scale score ranging from 0 to 60, with higher scores reflecting greater depression severity. Depression severity can be categorized into normal (0-6), mild depression (7–19), moderate depression (20–34), and severe depression (34–60). This study used the highly reliable Korean version of MADRS [

26]. The K–MADRS of this study reached a high reliability (Cronbach’s α = 0.96).

The HARS was developed by Hamilton [

27] and applied by the clinician to determine anxiety level and symptom distribution. It contains 14 questions, including sub-dimensions questioning both psychic and somatic symptoms. It is a five-point Likert-type scale (range 0–4). The total score is calculated by the sum of the scores obtained from each item. Severity of the anxiety can be categorized into normal (0–7), mild (8–14), moderate (15–23), and severe (24–64). In this study, we used the highly reliable Korean version of HARS [

28]. The K–HARS of this study reached a high reliability (Cronbach’s α = 0.98).

The STAI was used to evaluate the anxiety level of the subjects [

29]. It is a self-report questionnaire created to measure a person's level of anxiety. The STAI consists of two forms. The STAI-S measures anxiety in the present moment (20 items, state anxiety), and the STAI-T measures anxiety levels as a personal characteristic (20 items, trait anxiety). In this study, we used STAI-T. This scale has 20 items, each with a four-point Likert scale (1-4). Higher scores indicate higher levels of anxiety. We employed the highly reliable Korean version of the STAI-T [

30]. This study also showed high reliability (Cronbach’s α = 0.95). Since depression and anxiety disorder often occur together, it is vital to measure anxiety in patients with depression. Therefore, despite already measuring anxiety disorders in HAM-A, STAI was applied to the questionnaire. In addition, since HAM-A is for the clinician to evaluate the patient's current anxiety symptoms, STAI-T was applied during STAI to evaluate the anxiety characteristics felt by the patient himself.

2.6. Data analysis

Data analysis was conducted using SPSS 18.0 Windows (SPSS, Chicago, IL, USA).

The paired t-test was used to compare the improvement of depression and anxiety before and after each group (urban forest healing program and control). Group difference of benefits was compared by covariance analysis (ANCOVA). If significant differences were found in the covariance analysis, the Bonferroni test verified Post hoc analysis for group differences. A p-value of less than 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

3. Results

3.1. Montgomery-Asberg depression rating scale (MADRS)

Table 1 shows the pre-and post-test MADRS score for each group. The MADRS score of the urban forest healing program group was significantly lower after than before (from 31.64 ± 2.27 to 10.45 ± 1.76; t = 7.524,

p < 0.001). Also, there were significant changes in the control group subjects’ MADRS scores (from 29.00 ± 2.91 to 21.36 ± 2.80; t = 4.063,

p < 0.001).

In order to increase the verification power of the difference in MADRS scores according to the program's application, a covariance analysis was conducted in which the pre-test scores were controlled as covariates (

Table 2). As a result, the urban forest healing program group had a significantly lower MADRS score than the control group (F = 18.775,

p < 0.001).

3.2. Hamilton Anxiety Rating Scale (HARS)

Table 3 shows the pre-and post-test HARS score for each group. The HARS score of the urban forest healing program group was significantly lower after than before (from 26.05 ± 2.27 to 6.05 ± 0.87; t = 8.898,

p < 0.001). Also, there were significant changes in the control group subjects’ HARS scores (from 26.08 ± 2.73 to 18.00 ± 2.43; t = 5.502,

p < 0.001).

In order to increase the verification power of the difference in HARS scores according to the program's application, a covariance analysis was conducted in which the pre-test scores were controlled as covariates (

Table 4). As a result, the urban forest healing program group had a significantly lower HARS score than the control group (F = 35.916,

p < 0.001).

3.3. State-Trait Anxiety Inventory form trait (STAI-T)

Table 5 shows the pre-and post-test STAI-T score for each group. The STAI-T score of the urban forest healing program group was significantly lower after than before (from 57.18 ± 1.83 to 50.09 ± 1.90; t = 4.382,

p < 0.001). However, there were no significant changes in the control group subjects’ STAI-T scores (from 57.20 ± 20.4 to 55.60 ± 2.35; t = 1.389,

p < 0.178).

In order to increase the verification power of the difference in STAI-T scores according to the program's application, a covariance analysis was conducted in which the pre-test scores were controlled as covariates (

Table 6). As a result, the urban forest healing program group had a significantly lower STAI-T score than the control group (F = 8.017,

p = 0.007).

4. Discussion

This study investigated the benefits of an urban forest healing program on depression and anxiety symptoms of depression patients. This study demonstrated that combining general medication and urban forest healing programs significantly improves depression and anxiety symptoms in depression patients rather than performing general meditation alone.

Specifically, this study showed that the urban forest healing program decreased the MADRS score, which indicates the severity of depressive symptoms in patients with depression. Control group who received treatment as usual during the experimental period also showed a significant decrease in the MADRAS score. However, the control group did not change to “moderate depression“ in the pre-test (29.00 ± 2.91 score) and the post-test (21.36 ± 2.80 score). On the other hand, the urban forest healing program group changed from “moderate depression“ in the pre-test (31.64 ± 2.27 score) to “mild depression“ in the post-test (10.45 ± 1.76 score). In addition, even when comparing the differences between groups, the urban forest healing program showed statistically significantly lower MADRS score than the control group. This is consistent with previous studies that the forest healing program improves depressive symptoms in patients with major depressive disorder more than general treatment as usual [

31,

32]. For example, Woo et al. [

32] investigated the effectiveness of the forest healing program for patients with major depressive disorders by dividing it into four groups: forest healing program group, hospital program group, forest bathing group, and control group that perform treatment as usual. As a result, it was reported that the group that the forest healing program group had a significantly lower MADRS score than the control group that performed only treatment as usual.

Our results also showed that the urban forest healing program decreased the HARS score, which indicates the severity of anxiety symptoms in depression patients. Subjects in the control group also significantly reduce in HARS score. The control group changed from “severe” in the pre-test (26.08 ± 2.73 score) to “moderate” in the post-test (18.00 ± 2.43 score). On the other hand, the subjects in the urban forest healing program group improved from “severe” in the pre-test (26.05 ± 2.27 score) to “normal“ in the post-test (6.05 ± 0.87 score). This can be interpreted that the urban forest healing program group showed a treatment reaction as the total score of HARS decreased by more than half. On the other hand, the control group improved HARS score through outpatient treatment for 6 weeks, but did not show a treatment reaction.

This result is consistent with previous results in which cognitive behavioral therapy improved subjects' anxiety symptoms [

8,

33]. To our knowledge, it has never used a HARS measurement tool to investigate the effect of nature-based intervention on anxiety symptoms. In this study, it is meaningful to provide new evidence that urban forest healing programs have alleviated anxiety symptoms in patients with depression using HARS, which clinicians can evaluate.

The present study indicated that the urban forest healing program decreased the STAI-T scores of depression patients. Our results coincide well with previous studies of university students [

34] and patients with chronic stroke patients [

17] that forest healing program improved subject’s anxiety.

It is thought that reaching the complete recovery of social and professional functions is difficult only with pharmacological treatment. Despite pharmacological development, the depression response rate to antidepressant administration was found to be 50-70%, and the remission rate was only 30% [

35]. In addition, it is known that patients tend to be afraid of returning to their daily lives and rarely escape from dysfunction. It is already a habit to stay at home helplessly even though depressive symptoms have improved. Studies show that combining non-pharmacological and pharmacological treatments is beneficial in solving low compliance with antidepressant therapy, one of the biggest obstacles to depression treatment [

36,

37]. Therefore, an optimized treatment method that combines pharmacological and non-pharmacological treatment is required for better results.

Our findings suggest the use of forest healing as a non-pharmacological treatment. Most importantly, patients can interact with various environmental factors, including fresh air and open space, and five sensory stimuli, such as various visual, sound, scent, and touch from forests and trees. Previous studies have reported that five-sensory stimulation in a forest environment is effective in physical and mental relaxation [

38,

39,

40,

41]. Increasing patients' physical activity through forest healing programs is also likely effective in restoring patients' function. Physical activity is perceived to improve mental health, minimize side effects of drugs, and reduce depression in treating mental disorders such as depression [

42,

43,

44]. In addition, the subject site of this study was conducted in urban forests with excellent accessibility. Previous studies have reported that urban green spaces are a cost-effective, simple, and accessible way to prevent depression [

45,

46]. Accordingly, it is important to induce patients to use urban forests daily for health recovery actively.

Moreover, the forest environment can facilitate physical activity and psychological interaction. It is known that people can reconsider interpersonal problems in forest environments. The forest environment has resolved the sense of isolation by allowing them to connect with them through objects in nature and sharing their presence with empathy and support among subjects. According to Kim et al. [47], the forest healing program promotes social interactions, such as forming intimacy between subjects and improving interpersonal relationships. Hendee and Barown [48] also stated that collective forest experiences can provide social interaction and enhance bonding. This means that the more individuals share their feelings with others, the more cohesive they become between groups. Therefore, physical and psychological activities increase by inducing urban forest healing programs to interact with the forest environment, which has a significant therapeutic effect in this study.

This present study has limitations. First, the types and dosages of antidepressants the patients took in this study could not be identified. Future studies need to analyze the effects using dosages as covariates. Second, this study did not identify the subjects' usual exposure to nature. In future studies, the frequency and time of natural exposure of subjects need to be investigated and analyzed in detail. Third, present study showed a difference in gender ratio between the experimental group and the control group in the randomization process. There was no stratification of the randomization procedure, but in future studies, it is necessary to stratify gender to allocate the gender ratio equally. Fifth, this study did not investigate the long-term effects of urban forest healing programs. Future studies require a follow-up of continuous effects over 6 months.

Although these limitations exist, our findings provide evidence that urban forest programs using urban forests can be used as non-pharmacological interventions to improve depression and anxiety symptoms in depressive patients, along with pharmacological treatments.

5. Conclusions

This study demonstrated that supporting forest healing programs using urban forests in addition to general treatment significantly lowers depression and anxiety symptoms rather than providing only general treatment to patients with depression. These results show that urban forest healing programs can be used as non-pharmacological interventions combined with medication.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, P.-S.Y. and W.-S.S.; methodology, P.-S.Y. and J.-G.K.; development and practice of urban forest healing program, I.-O.K., S.-N.K., N.-E.L., G.-Y.K. and G.-M.M.; writing—original draft preparation, P.-S.Y. and J.-G.K.; writing—review and editing, J.-G.K. and W.-S.S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was supported by the R&D program for Forest Science Technology (project no. 2021403A00-2223-0102) funded by the Korea Forest Service (Korea Forestry Promotion Institute).

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Institutional Review Board of Chungbuk National University (CBNU-202203-HR-0041).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Acknowledgments

This work was conducted during the research year of Chungbuk National University in 2022. We appreciate the help of the forest therapy and forest welfare researchers at Chungbuk National University.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- World Health Organization. Depression disorder. Available online: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/depression (accessed on 29 May 2023).

- Malhi, G.S.; Mann, J.J. Depression. Lancet 2018, 392, 2299–2312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giacobbe, P.; Flint, A. Diagnosis and management of anxiety disorders. Continuum (Minneap, Minn). 2018, 24, 893–919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gorman, J.M. Comorbid depression and anxiety spectrum disorders. Depress Anxiety 1996, 4, 160–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Constable, P.A.; Al-Dasooqi, D.; Bruce, R. .; Prem-Senthil, M. A review of ocular complications associated with medications used for anxiety, depression, and stress. Clin. Optom 2022, 13–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tomlinson, C.L.; Patel, S.; Meek, C.; Herd, C.P.; Clarke, C. E; Stowe, R; et al. Physiotherapy intervention in Parkinson’s disease: systematic review and meta-analysis, BMJ 2012, 345, e5004. [Google Scholar]

- Luo, F.; Ye, M.; Lv, T.; et al. Efficacy of Cognitive Behavioral Therapy on Mood Disorders, Sleep, Fatigue, and Quality of Life in Parkinson's Disease: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Front. Psychiatry 2021, 12, 793804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sutanto, Y.S.; Ibrahim, D.; Septiawan, D.; Sudiyanto, A.; Kurniawan, H. Effect of cognitive behavioral therapy on improving anxiety, depression, and quality of life in pre-diagnosed lung cancer patients. APJCP 2021, 22, 3455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shin, W. Forest Policy and Forest Healing in the Republic of Korea. Available online: https://www.infom.org/news/2015/10/10.html (accessed on 4 July 2023).

- Rajoo, K.S.; Karam, D.S.; Abdullah, M. Z. The physiological and psychosocial effects of forest therapy: A systematic review. Urban For Urban Green 2020, 54, 126744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kotera, Y.; Richardson, M.; Sheffield, D. Effects of shinrin-yoku (forest bathing) and nature therapy on mental health: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Int J Ment Health Addict 2020, 1–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stier-Jarmer, M.; Throner, V.; Kirschneck, M.; Immich, G.; Frisch, D.; Schuh, A. 2021. The psychological and physical effects of forests on human health: A systematic review of systematic reviews and meta-analyses. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 1770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Ye, B. Forest therapy in Germany, Japan, and China: Proposal, development status, and future prospects. Forests 2022, 13, 1289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jung, W.H.; Woo, J.M.; Ryu, J.S. Effect of a forest therapy program and the forest environment on female workers’ stress. Urban For Urban Green 2015, 14, 274–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yi, Y.; Seo, E.; An, J. Does forest therapy have phys-io-psychological benefits? A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 10512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chun, H.R.; Choi, Y.Y.; Cho, I.; Nam, H.K.; Kim, G.; Park, S.; Cho, S.I. Indicators of the Psychosocial and Physiological Effects of Forest Therapy: A Systematic Review. Forests 2023, 14, 1407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chun, M. H.; Chang, M.C.; Lee, S.J. The effects of forest therapy on depression and anxiety in patients with chronic stroke. Int. J. Neurosci 2017, 127, 199–203. [Google Scholar]

- Choi, Y.H.; Ha, Y.S. The Effectiveness of a Forest-experience-integration Intervention for Community Dwelling Cancer Patients’ Depression and Resilience. J. Korean Acad. Community Health Nurs 2014, 25, 109–118. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, Y.G.; Lee, S.H.; Kim, Y.H.; Eum, J.O.; Yim, Y.R.; Ha, T.G.; Shin, C.S. The Influence of Forest Activity Intervention on Anxiety, Depression, Profile of Mood States(POMS) and Hope of Cancer Patients. J. Korean Inst. For. Recreat 2015, 19, 65–74. [Google Scholar]

- Lim, Y.S.; Kim, D.J.; Yeoun, P.S. Changes in Depression Degree and Self-esteem of Senior Citizens in a Nursing Home According to Forest Therapy Program. J. Korean Inst. For. Recreat 2014, 18, 1–11. [Google Scholar]

- Han, J.W.; Choi, H.; Jeon, Y.H.; Yoon, C.H.; Woo, J.M.; Kim, W. The effects of forest therapy on coping with chronic widespread pain: Physiological and psychological differences between participants in a forest therapy program and a control group. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2016, 13, 255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosa, C.D.; Larson, L.R.; Collado, S.; Profice, C.C. Forest therapy can prevent and treat depression: Evidence from meta-analyses. Urban For Urban Green 2021, 57, 126943. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yeon, P.S.; Jeon, J. Y.; Jung, M. S.; et al. Effect of forest therapy on depression and anxiety: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 12685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kang, M.J.; Kim, H.S.; Kim, J.Y. Effects of Forest-Based Interventions on Mental Health: A Meta-Analysis of Randomized Controlled Trials. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 4884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Montgomery, S.A.; Åsberg, M. A new depression scale designed to be sensitive to change. Br J Psychiatry 1979, 134, 382–389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ahn, Y.M.; Lee, K.Y.; Yi, J.S.; et al. A validation study of the Korean-version of the Montgomery-Asberg depression rating scale. Journal of Korean Neuropsychiatric Association 2005, 466–476. [Google Scholar]

- Hamilton, M. The assessment of anxiety states by rating. Br J Med Psychol 1956, 32, 50–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, C.Y.; Kim, K.H.; Kim, S.Y.; et al. Psychiatric assessment instruments; Hana bachelor of Medicine: Seoul, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Woo, J.M.; Park, S.M.; Lim, S.K.; Kim, W. Synergistic Effect of Forest Environment and Therapeutic Program for the Treatment of Depression. J. Korean For. Soc 2012, 101, 677–685. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Z.; Qiao, D.; Xu, Y.; et al. The efficacy of computerized cognitive behavioral therapy for depressive and anxiety symptoms in patients with COVID-19: randomized controlled trial. J. Medical Internet Res 2021, 23, e26883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, D.J.; Lee, S.S. Effects of Forest Therapy Program in School Forest on Employment Stress and Anxiety of University Students. J. Korean Soc. People Plants Environ 2014, 17, 107–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chun, M.H.; Chang, M.C.; Lee, S.J. The effects of forest therapy on depression and anxiety in patients with chronic stroke. Int. J. Neurosci 2017, 127, 199–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cipriani, A.; Furukawa, T.A.; Salanti, G.; Geddes, J.R.; Higgins, J.P.; Churchill, R. , et al. Comparative efficacy and acceptability of 12 newgeneration antidepressants: a multiple-treatments meta-analysis. Lancet 2009, 373, 746–758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hollon, S.D.; DeRubeis, R.J.; Evans, M.D.; et al. Cognitive therapy and pharmacotherapy for depression: singly and in combination. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1992, 49, 774–781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kocsis, J.H.; Gelenberg, A.J.; Rothbaum, B.O.; et al. REVAMP Investigators. Cognitive behavioral analysis system of psychotherapy and brief supportive psychotherapy for augmentation of antidepressant nonresponse in chronic depression: the REVAMP Trial. Arch Gen Psychiatry 2009, 66, 1178–1188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Anderson, A.P.; Mayer, M.D.; Fellows, A.M.; Cowan, D.R.; Hegel, M.T.; Buckey, J.C. Relaxation with Immersive Natural Scenes Presented Using Virtual Reality. Aerosp Med Hum Perform 2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ikei, H.; Song, C.; Miyazaki, Y. Physiological Effects of Touching Wood. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2017, 14, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.; Zhao, X.; Zeng, Z.; Qiu, X. The influence of audio-visual interactions on psychological responses of young people in urban green areas: A case study in two parks in China. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2017, 16, 1845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antonelli, M.; Donelli, D.; Barbieri, G.; Valussi, M.; Maggini, V.; Firenzuoli, F. Forest Volatile Organic Compounds and Their Effects on Human Health: A State-of-the-Art Review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 6506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashdown-Franks, G.; Firth, J.; Careney, R.; Carvalho, A.F.; Hallgren, M.; Koyanagi, A.; Rosenbaum, S.; Schuch, F.B.; Smith, L.; Solmi, M.; et al. Exercise as medicine for mental and substance use disorders: A meta-review of the benefits for neuropsychiatric and cognitive outcomes. Sports Med 2020, 50, 151–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gill, B.K.; Cant, R.; Lam, L.; Cooper, S.; Lou, V.W.Q. Non-pharmacological depression therapies for older Chinese adults: A systematic review & meta-analysis. Arch. Gerontol. Geriatr 2020, 88, 104037. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, Y.H.; Kim, H.; Cho, H. The Effectiveness of Physical Activity Interventions on Depression in Korea: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Healthc 2022, 10, 1886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Callaghan, A.; McCombe, G.; Harrold, A.; McMeel, C.; Mills, G.; Moore-Cherry, N.; Cullen, W. The impact of green spaces on mental health in urban settings: a scoping review. J Ment Health 2021, 30, 179–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, R.; Zheng, Y.J.; Yun, J.Y.; Wang, H.M. The Effects of Urban Green Space on Depressive Symptoms of Mid-Aged and Elderly Urban Residents in China: Evidence from the China Health and Retirement Longitudinal Study. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, J.G.; Shin, W.S. Forest therapy alone or with a guide: is there a difference between self-guided forest therapy and guided forest therapy programs? Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 6957. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hendee, J.; Brown, M. How Wilderness Experience Programs Facilitate Personal Growth: The Hendee/Brown Model; Institute of Education Sciences: Washington, DC, USA, 1987. [Google Scholar]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).