1. Introduction

African swine fever (ASF) is a highly contagious and severe hemorrhagic transboundary swine viral disease with up to 100% mortality rate, which leading to a tremendous socio-economic loss worldwide [

1]. The causative agent, ASF virus (ASFV), is a large, enveloped virus containing a double-stranded DNA (dsDNA) genome of approximately 170-190 kilobase pairs (kbp) [

2]. A total of 24 ASFV genotypes (I-XXIV) have been described based on the ASFV p72 major capsid protein gene (

B646L) [

3]. The highly virulent ASFV genotype II that emerged in the Caucasus region in 2007 is responsible for the contemporary pandemic in Europe/Asia, and the outbreaks in Caribbean countries (Dominican Republic and Haiti) [

4,

5,

6,

7]. The first outbreak of ASF in Vietnam has been reported in early 2019 and quickly spread across the entire country with more than 8 million piglets depopulated, which equal to nearly 25 percent of the total pig population in 2020 [

8,

9,

10]. At present, ASFV genotype II becomes endemic and ASF outbreak is continuing to occur frequently in Vietnam, raising the greatest concerns not only for the government but also for the pig industries.

The lack of safe and efficacious ASF vaccines is the greatest challenge in the prevention and control of ASF. In the past several years, extensive efforts have been pursued to develop ASF vaccines which include inactivated vaccines, recombinant subunit vaccines (protein-based, DNA, viral-vectored), and live-attenuated strains (LAVs) [

11,

12,

13,

14]. Up to now, the inactivated and recombinant subunit vaccines have not yet been shown to be efficacious [

11,

15,

16,

17]. In contrast, recent promising results with LAVs provide hope for a safe and efficacious vaccine against ASF. Several groups have developed LAVs by the deletion of genes associated with virulence, which induced solid protective immunity against homologous strains. Among them, ASFV-G-ΔI177L, ASFV-G-ΔI177LΔLVR and ASFV-G-ΔMGF strains proved to be attenuated phenotype in pigs and conferred full protection against challenge of parental ASFV-Georgia strain [

18,

19,

20,

21,

22]. However, ideal LAVs which meet the commercial vaccine demands still face challenges related to stable cell lines for producing the LAV at a large scale, efficacy depends on the age of pigs, reversion to virulence, vaccine virus shedding, and differentiation of infected from vaccinated animals (DIVA) [

13,

14,

23,

24].

Since the identification of ASF outbreak in Vietnam, research towards vaccine development using field ASFV genotype II isolate has been initiated in our groups. Here, we report the generation of a safe and efficacious LAV vaccine VNUA-ASFV-LAVL2 from a field isolate by cell passage. VNUA-ASFV-LAVL2 not only can protect pigs 100% against virulent contemporary pandemic ASFV infection, but also can efficiently replicate in the commercially available 3D4/21 cell line.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Animals

Crossbred (Yorkshire-Landrate-Duroc) weaned specific-pathogen-free male and/or female piglets (4-7 weeks of age) were purchased from commercial vendors and used in this study. The pigs were fed with a standard commercial diet. In Vietnam, the pigs were housed in Animal Biosafety Research Facility of the Faculty of Veterinary Medicine, Vietnam National University of Agriculture (VNUA). In the United States, the pigs were housed under laboratory biosafety level III Agriculture (BSL3-Ag) conditions at the Biosecurity Research Institute (BRI), Kansas State University (KSU). Animal care and protocols were approved by Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee at Vietnam National University of Agriculture (VNUA-2021/01) and at Kansas State University (IACUC#4845). All animal experiments were done under strict adherence to the IACUC protocols.

2.2. Cells and Virus

Primary pulmonary alveolar macrophages (PAM) were prepared as described previously [

25]. PAM is maintained in medium including Dulbecco’s modified Eagle medium (DMEM, Life Technologies, Grand Island, NY, USA) supplemented with 10% heat-inactivated fetal bovine serum (FBS, Thermo Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA) and Antimycotic (Life Technologies, Grand Island, NY, USA) at 37℃ in 5% CO

2 incubator.

3D4/21 (immortalized porcine alveolar macrophage cell line, ATCC, CRL-2843) cells were cultured in medium RPMI high glutamine (RPMI, Life Technologies, Grand Island, NY, USA) adjusted to contain 1.5 g/L sodium bicarbonate (Thermo Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA), 4.5 g/L glucose (Thermo Scientific, Waltham, MA), 10 mM HEPES (Thermo Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA), 1.0 mM sodium pyruvate (Thermo Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA) supplemented with 1% MEM Non-Essential Amino Acids Solution (Thermo Scientific, Waltham, MA) and 10% heat-inactivated fetal bovine serum (FBS, Thermo Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA) at 37℃ in 5% CO2 incubator.

Virulent VNUA-ASFV-05L1 strain (genotype II) was isolated from the spleen of a domestic pig with typical acute ASF during an ASF outbreak in northern Vietnam in 2020 [

26]. It is kept in BSL-3 laboratories in Vietnam National University and at Kansas State University. This virus was used for generation of LAV and challenge studies in pigs in this study.

2.3. Virus Passage and Virus Replication Evaluation In Vitro

Wild-type virulent VNUA-ASFV-05L1 strain was passaged in PAM cells and 3D4/21 cells. We used the same culture medium for infection and passage VNUA-ASFV-05L1 strain in PAM cells. For 3D4/21 cells, we added 1.25% Dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) in the culture medium for improving its ability to support VNUA-ASFV-05L1 replication. Monolayers were infected with VNUA-ASFV-05L1 at the multiplicity of infection (MOI) of 1 and incubated for 4 days. Culture supernatant was then harvested, titrated, and passaged onto fresh monolayers at MOI of 1. The VNUA-ASFV-05L1 underwent 120 passages in PAM cells (65 passages) and 3D4/21 cells (55 passages) to generate VNUA-ASFV-LAVL2. Virus titers in the supernatants at each passage were titrated in PAMs. PAMs were pre-seeded (80-100% confluent) and incubated with 10-fold dilutions of the harvested supernatants. After 2 hours (hrs) incubation, 2% porcine red blood cells were added for hemadsorption (HAD) testing. After four days culture, the presence of ASFV was assessed by HAD under an inverted microscope. HAD

50 was calculated by using the method of Reed and Muench [

27].

For testing the in vitro replication characteristics of VNUA-ASFV-LAVL2 and its parental virus (VNUA-ASFV-05L1), monolayers of PAMs and 3D4/21 cells at 90% confluency in 24 well culture plates were infected with the viruses at MOI of 1. After 2 hrs incubation, the inoculum was removed. Cells were washed and replaced with fresh culture media. Cultures (including cells and culture medium) were collected at 0, 24, 36, 48, 60, 72, 84, and 96 hrs post-infection (HPI). The collected cultures were subjected to three freeze-thaw cycles. After spinning down the cell debris, virus titers in the supernatant were tested and calculated as described above. All experiments were performed in duplicate.

2.4. Safety Testing of LAV in Pigs

To test the safety of VNUA-ASFV-LAVL2 in pigs, groups of pigs (n = 5/group) were inoculated intramuscularly (i.m.) either with 102, 103, 104, and 105 HAD50/dose of VNUA-ASFV-LAVL2 or with 8x102 HAD50 of parental VNUA-ASFV-05L1. Control pigs (n = 3) were inoculated (i.m.) with DMEM medium. Blood, oral fluids, rectal swabs, and serum samples of pigs were collected at different days post-inoculation (DPI). The presence of clinical signs (anorexia, depression, fever, purple skin discoloration, staggering gait, diarrhea, and cough), body temperature, and survival rate were recorded daily throughout the experiment.

To further evaluate the safety of the LAV, we pooled the serum of 103 HAD50/dose of VNUA-ASFV-LAVL2 inoculated pigs and i.m. inoculated 1ml/dose in pigs (n=3) to obtain passage 1 (P1). At 9 DPI when the serum samples showed the highest Ct value with ASFV real-time PCR (RT-PCR), we pooled the collected serum samples from P1 pigs and i.m. inoculated 1ml/dose in pigs (n=3) to obtain P2. Five passages were performed with the same method and procedure. Blood and serum samples were collected at different DPI. Clinical signs, body temperature, and survival rate were recorded daily throughout the experiment.

2.5. Efficacy Evaluation of LAV in Pigs

At DPI 28, pigs in 102, 103, 104, and 105 HAD50/dose of VNUA-ASFV-LAVL2 inoculated groups and DMEM inoculated control group were challenged (i.m.) with 1x103 HAD50 of parental VNUA-ASFV-05L1. The blood, oral fluids, rectal swabs, and serum samples of pigs were collected at different days post-challenge (DPC). The presence of clinical signs, body temperature, and survival rate were recorded daily throughout the experiment. The dead pigs in the control group were assessed for typical signs of ASFV pathological lesions. Tissue samples including brain, kidney, liver, spleen, lung, heart, lymph nodes, stomach, small intestines, large intestines, and bone marrow were aseptically collected from all dead pigs during the experiment and euthanized pigs at 28 DPC.

In a separate animal study, to evaluate the efficacy of LAV against high doses of ASFV challenge, pigs (n=5/group) were inoculated (i.m.) with 102 or 103 HAD50/dose of VNUA-ASFV-LAVL2. Control pigs (n = 3) were i.m. inoculated with DMEM. In addition, we housed 2 contact pigs in the same cage of each vaccinated pig group. At DPI 28, 10 times higher (8x103 HAD50/dose) than the standard challenge dose (8x102 HAD50/dose) were used to challenge the immunized and control pigs. Sample collection, clinical sign observation, body temperature and survival rate recording were performed as above described.

2.6. DNA Extraction, Quantitative ASFV Real-Time PCR and Genome Sequencing

Quantitative RT-PCR was conducted to detect ASFV DNA in oral fluid and rectal swabs, blood, and tissue homogenates of the experimental pigs. DNA was extracted by using an automated King Fisher™ Duo Prime DNA/RNA extraction system (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA) with MagMAX CORE Nucleic acid purification kit (Life Sciences, NY, USA), according to the manufacturer’s protocols. ASFV DNA was then detected using Platinum SuperMix-UDG kit (Invitrogen, Waltham, MA, USA) on CFX Optus 96 Real-time PCR system (BioRad, Hercules, CA, USA) using p72 primers and probe developed by Haines et.al. [

28]. Samples with Ct values <40 were considered positive.

The ASFV genome next-generation sequencing and

de novo genome assembly were performed as described previously [

26]. LAV whole genome analysis and comparison with the parental virus VNUA-ASFV-05L1 (GenBank accession number MW465755.1) were performed using Genome Workbench from NCBI (

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/tools/gbench/) and CLC Sequence Viewer 8.0.0 (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany).

2.7. ASFV Specific Antibody Detection

The ASF blocking ELISA kit (INGEZIM PPA COMPAC 11.PPA.k3, Ingenasa, Madrid, Spain) was used to detect specific anti-ASFV antibodies in serum samples. The procedure of the commercial ELISA kit was carried out as described in the manufacturer’s instructions. For each sample, the competition percentage (S/N%) was calculated according to the manufacturer’s instructions. More than or equal to (≥) 50% was considered positive, between 40 and 50% was considered doubtful, and ≤40% was considered negative.

2.8. ELISPOT and ELISA to Evaluate IFN-γ and IL-10 Cellular Responses in Pigs

Interferon gamma (IFN-γ) production by peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMC) of pigs was determined by enzyme-linked immunospot assay (ELISPOT). Briefly, the PBMCs of pigs were isolated freshly by density-gradient centrifugation with Ficoll-Paque PREMIUM density gradient media 1.077g/ml (Cytiva, Marlborough, MA, USA) in SepMate™ tubes (STEMCELL Technologies Inc., Cambridge, MA, USA). The PBMCs suspensions (2 × 105/well) were added to MultiScreenHTS IP Filter Plates (Millipore Sigma, Lenexa, KS, USA) precoated with Mouse anti-pig IFNγ (BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA, USA). The PBMCs were incubated 18 hours at 37°C with 100μl/well of stimulatory agents: phorbol myristate acetate (PMA, 25 ng/ml)/Ionomycin (2.5μg/ml) (Millipore Sigma, Lenexa, KS, USA) combination as positive controls; 100μl/well of VNUA-ASFV-05L1 (105 HAD50/ml) as re-stimulation agents; 100μl/well of complete culture media as unstimulated controls. After washing, Biotin mouse anti-pig IFNγ (BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA, USA), HRP Streptavidin for ELIspot (BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA, USA), and fresh NovaRED Peroxidase Substrate (Vector Labs, Newark, CA, USA) were added according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Finally, the reaction was stopped by rinsing the plate with deionized water. The number of spots was determined using a CTL Spot Reader (CTL, New York, NY, USA).

The concentration of porcine IL-10 in serum samples of pigs were measured by porcine IL-10 Quantikine ELISA kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA) according to the manufacturer’s instructions.

2.9. Statistical Analysis

Statistical analysis was performed using GraphPad Prism 6.0 (GraphPad Software, CA, USA). The data from assays for virus titration in cell cultures, and blood samples in experimental piglets at different time points and efficacy studies were expressed as the mean log HAD ± SD (Standard deviation) for each group and analyzed by Student’s t-test. The data for antibody and cellular responses were expressed as mean readings ± SD for each group. The significance of differences between the experimental groups was analyzed by analysis of variance (ANOVA) followed by Turkey’s post-test. For all statistical analyses, P values less than 0.05 were considered statistically significant.

3. Results

3.1. VNUA-ASFV-LAVL2 Replicates Stably and Efficiently in both PAMs and 3D4/21 Cells

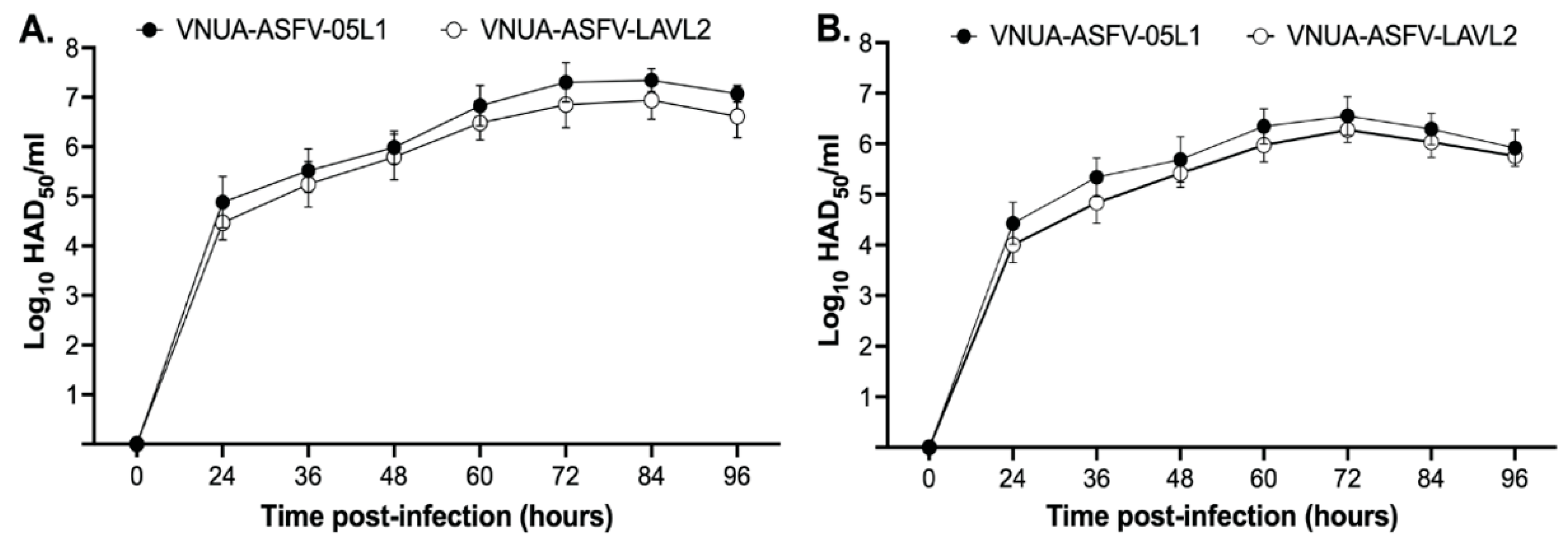

We compared the growth characteristics of VNUA-ASFV-LAVL2 with its parental virus VNUA-ASFV-05L in PAMs and 3D4/21 cells. VNUA-ASFV-LAVL2 showed growth at moderate titers around 10

5 HAD

50/ml for the first 15 passages, then at moderate to high titers around 10

5 to 10

6 HAD

50/ml in 3D4/21 cells. The virus retained the stable replication phenomenon (similar growth ability) from passage 110 to passage 120 with the highest titer 10

6 HAD

50/ml at 72 HPI. It (passage 120) showed comparable growth kinetics with less than 0.5 log

10 at each time points post-infection in both PAMs and 3D4/21 cells compared to that of parental VNUA-ASFV-05L1 strain (

Figure 1A,B).

3.2. Genome Comparison of VNUA-ASFV-LAVL2 with Parental Virus VNUA-ASFV-05L1

Next-generation sequence analysis data of VNUA-ASFV-LAVL2 (passage 120) indicate that it lacked a region corresponding to the multigene family (MGF) between 168,120 bp and 179,264 bp of VNUA-ASFV-05L1 (GenBank accession number MW465755.1), resulting in 13 gene deletions (MGF110-5-6L, MGF110-7L, 285L, MGF 110-8L, MGF 100-1R, MGF 110-9L, MGF 110-11L, MGF 110-14L, MGF 110-12L, MGF 110-13L, MGF360-4L, MGF360-6L, X69R) and 14 uncharacterized sequence deletions (

Table 1). Mutations which resulted in amino acid substitutions or protein disruptions are found in the genome of VNUA-ASFV-LAVL2 as well (

Table 1).

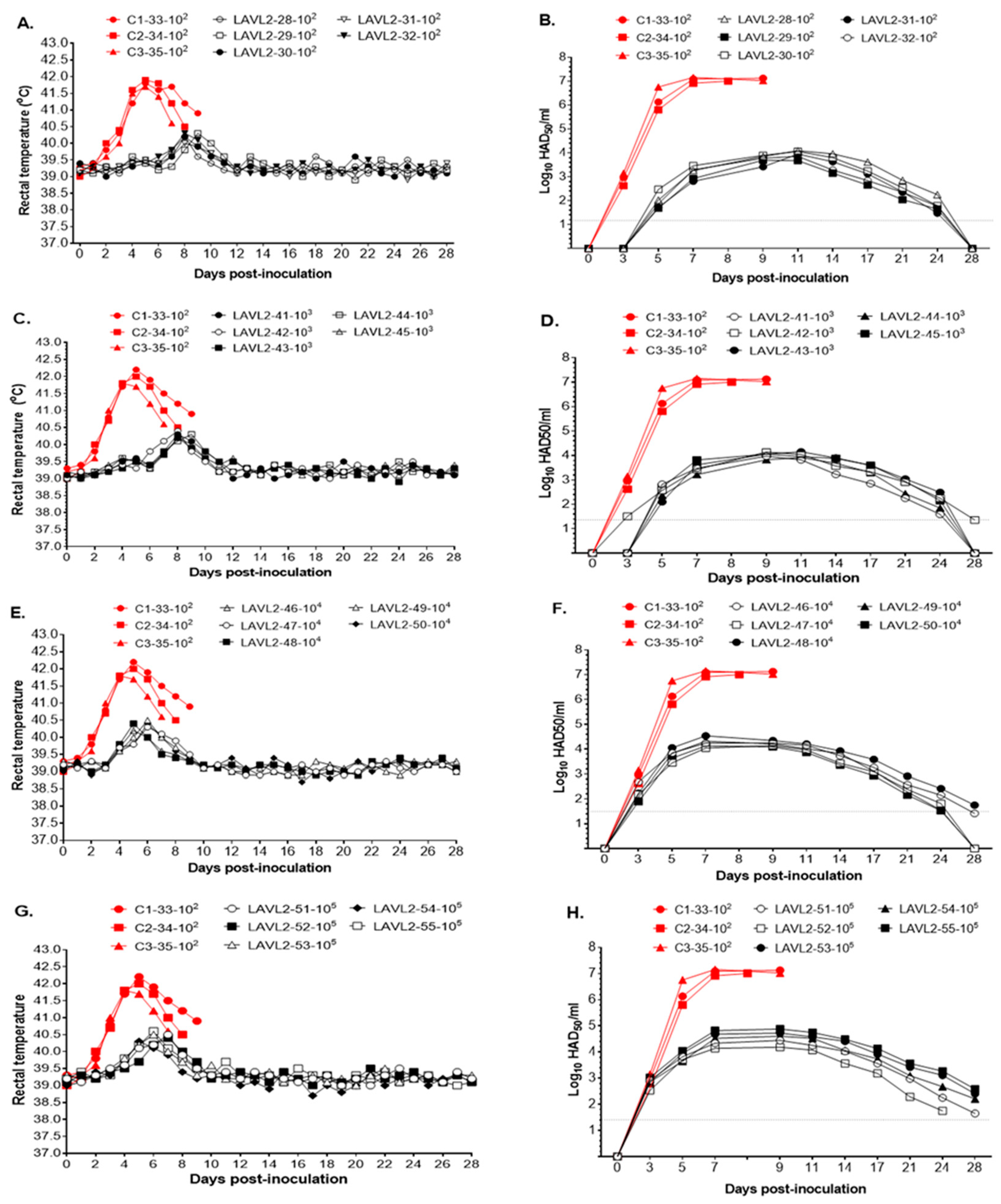

3.3. VNUA ASFV-LAVL2 is Significantly Attenuated and Highly Safe in Pigs

Pigs vaccinated with VNUA-ASFV-LAVL2 from low dose (10

2 HAD

50) to high dose (10

5 HAD

50) showed transient low fever (<40.6°C) by days of 7-10 DPI (

Figure 2A,C) and 5-7 DPI (

Figure 2E,G), then showed normal body temperature during the observation period of 28 days. No obvious ASFV specific clinical signs were observed for the vaccinated pigs. In contrast, the parental VNUA-ASFV-05L1 inoculated control pigs displayed clinical signs of ASF, including high fever, anorexia, cough, depression, staggering gait, and diarrhea. All control pigs died due to severe clinical symptoms during 8-10 DPI.

VNUA-ASFV-LAVL2 vaccinated pigs showed significant lower viremia than that of parental VNUA-ASFV-L2 inoculated control pigs. The control pigs reached peak titers of approximately 10

7 HAD

50/ml before they died. Whereas, VNUA-ASFV-LAVL2 vaccinated pigs reached the highest viremia titer 10

4 to 10

5 HAD50/ml at 7 to 11 DPI, and then were rapidly declined and almost cleared at 28 DPI (

Figure 2B,D,F,H).

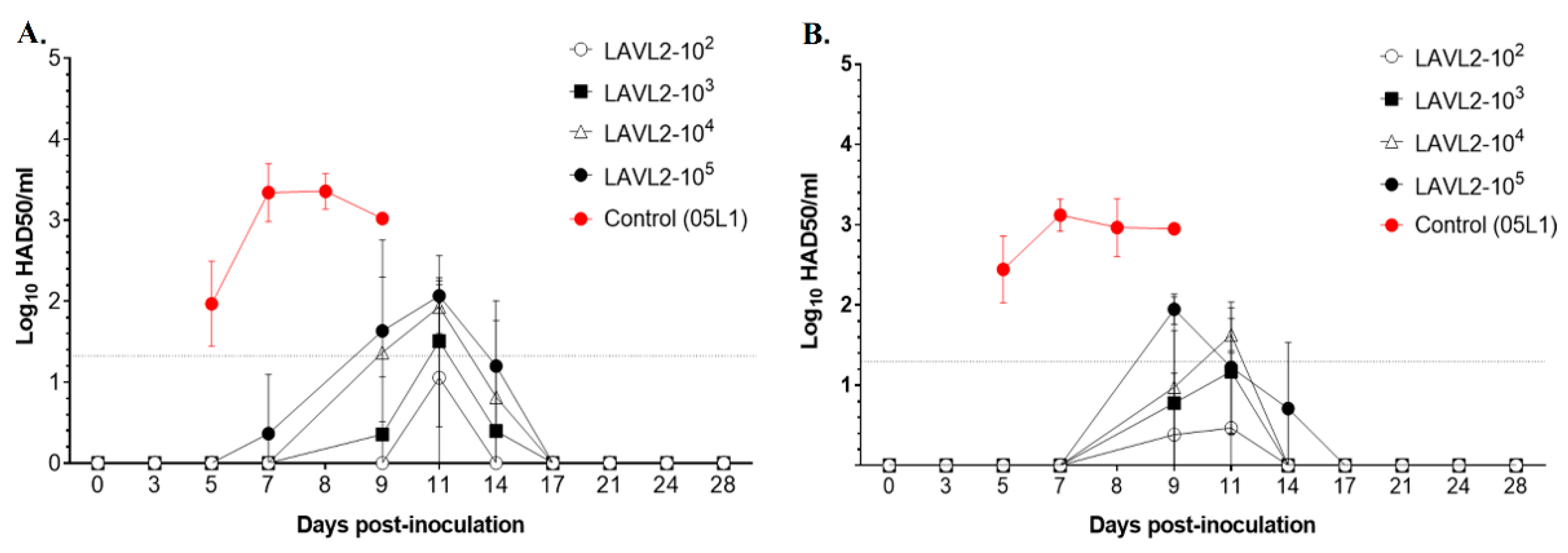

In oral fluid swabs (

Figure 3A) and rectal swabs (

Figure 3B), only very low viral titers (less than 10

2 HAD

50/ml) were detected in VNUA-ASFV-LAVL2 vaccinated pigs from 9 DPI to 14 DPI, and the VNUA-ASFV-LAVL2 viruses were rapidly cleared after 17 DPI. In contrast, for the VNUA-ASFV-05L1 inoculated control pigs, viral titer in oral fluid swabs and rectal swabs reached peak titers of approximately 3.5x10

3 HAD

50/ml and remained steady before they died.

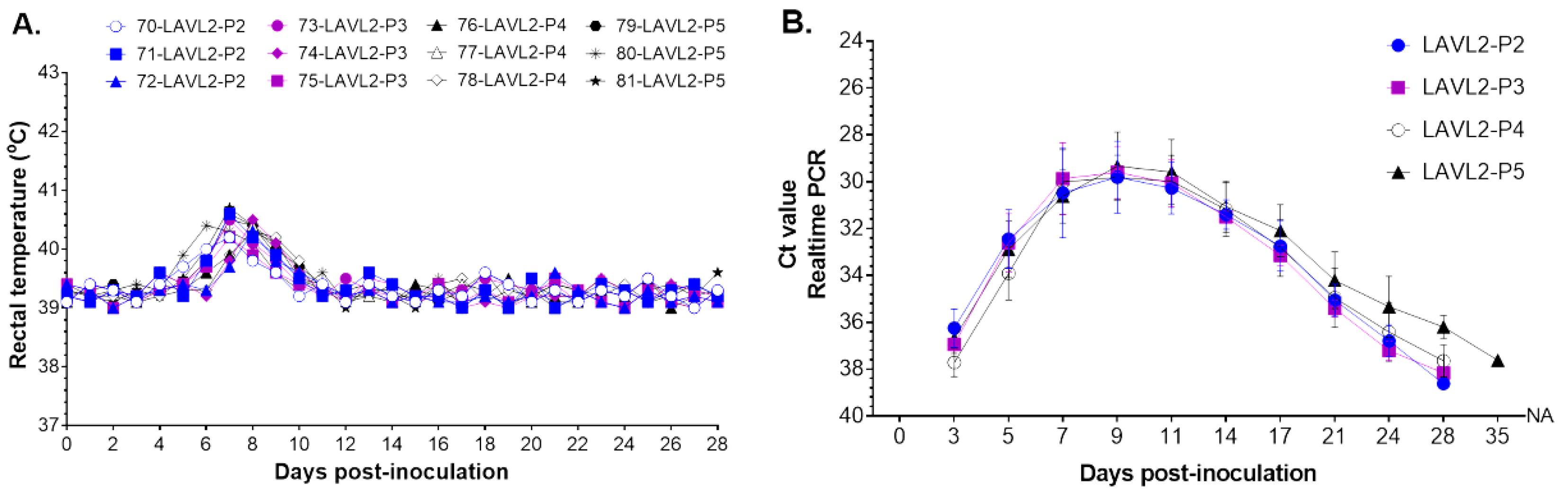

3.4. VNUA-ASFV-LAVL2 Maintained Safe and Attenuated Phenotype when Passages in Pigs with Pooled Serum Samples

To further evaluate the safety of VNUA-ASFV-LAVL2, we performed its serial passaging in pigs with pooled serum samples which showed the highest Ct values by ASFV RT-PCR. Totally five passages (P1 to P5) in pigs were completed in this study. Pigs in all passages showed transient low fever (<40.6°C) by days of 6-9 DPI , then showed normal body temperature during the obsevation period (

Figure 4A), and no obvious ASFV specific clinical signs were observed. All pigs maintained the good daily feed intake, healthy and 100% survival until the end of tests. Viremia study showed that replication of VNUA-ASFV-LAVL2 reached peak with Ct value about 30 at 9 DPI, and then rapidly decreased and cleared from the blood from 11 DPI to 35 DPI (

Figure 4B). All passages showed similar viremia and clearance rate of VNUA-ASFV-LAVL2 in inoculated pigs.

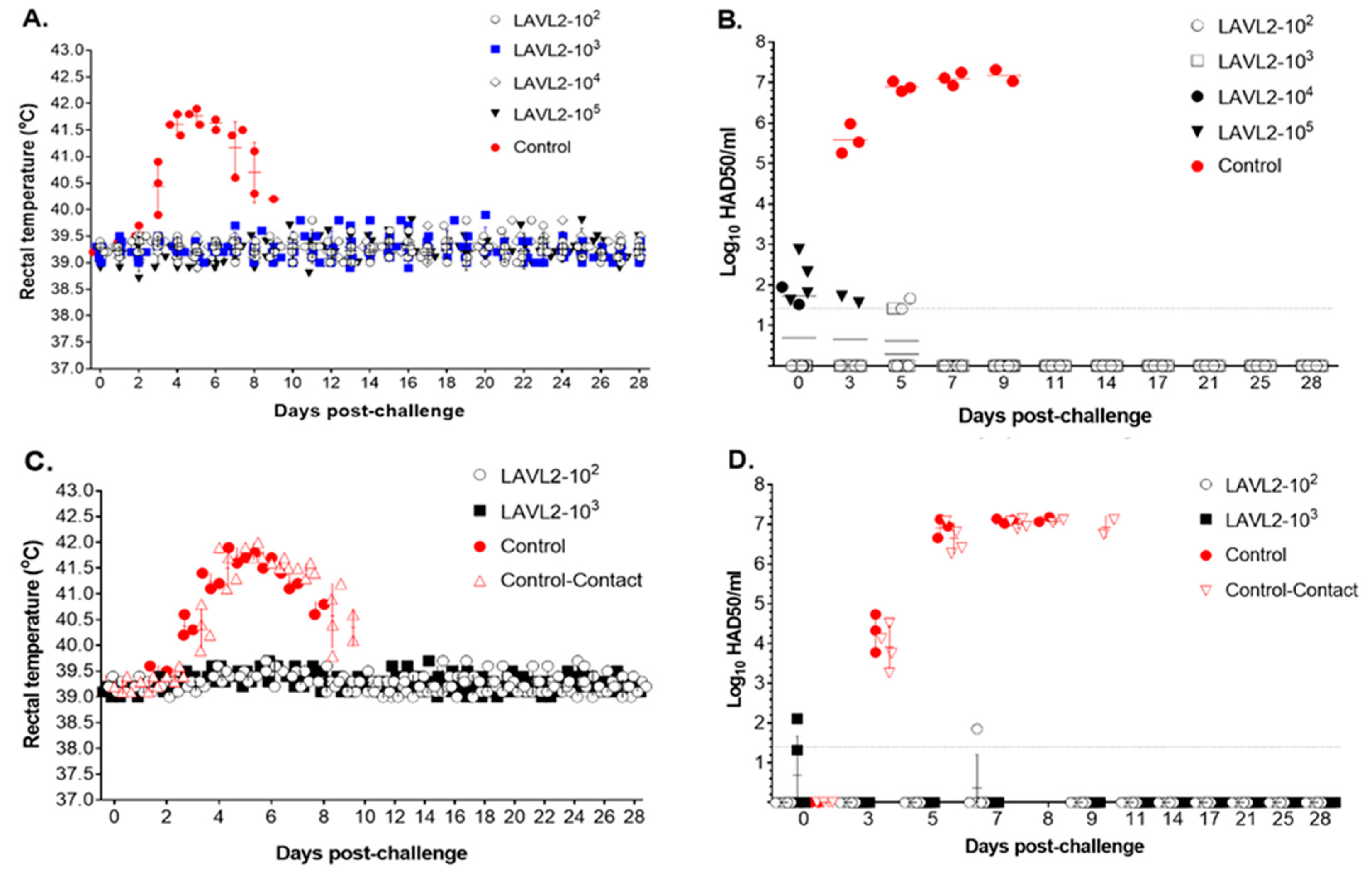

3.5. Pigs Vaccinated with VNUA-ASFV-LAVL2 were Fully Protected from Contemporary Pandemic ASFV Challenge

To test the efficacy of VNUA-ASFV-LAVL2, pigs in both vaccinated groups and the control group (inoculated with DMEM) were challenged with parental VNUA-ASFV-05L1, the contemporary pandemic genotype II ASFV. After challenge, pigs in the control group rapidly (from 5 to 9 DPC) displayed clinical signs of ASF, including high fever (

Figure 5A), anorexia, cough, depression, staggering gait, and diarrhea, and died from 8 to 9 DPC. In contrast, pigs vaccinated with VNUA-ASFV-LAVL2 (from low dose 10

2 HAD

50 to high dose 10

5 HAD

50) did not show elevated body temperature after challenge (

Figure 5A). The vaccinated pigs exhibited a high level of protection with 100% survival and healthy against virulent VNUA-ASFV-05L1 challenge. Remarkably, only very low level of ASFV was detected in the blood before 5 DPC (

Figure 5B), and ASFV was not detected in oral fluid or rectal swabs of all vaccinated groups. Whereas in control group, the ASFV was detected in blood samples from 3 to 5 DPC, and rapidly increased from 5 to 9 DPC (

Figure 5B).

To further test protective efficacy, we used a higher challenge dose (8x10

3 HAD

50) than the standard challenge dose for the VNUA-ASFV-LAVL2 vaccinated (10

2 and 10

3 HAD

50/dose) pigs. In addition, we housed 2 contact control pigs in the same cage of each pig group. The results showed that all vaccinated groups can induce full protection with 100% survival and healthy against challenges of high doses of virulent VNUA-ASFV-05L1 strain (

Figure 5C). Almost no ASFV was detected in blood (

Figure 5D), oral fluid and rectal swab samples of vaccinated pigs during the 28-day period of challenge. Whereas ASFV was detected in blood samples of control pigs and contact control pigs at 3 DPC, and reached the highest titer from 7 to 9 DPC. The pigs from control group and contact control group died within 7 to 9 DPC.

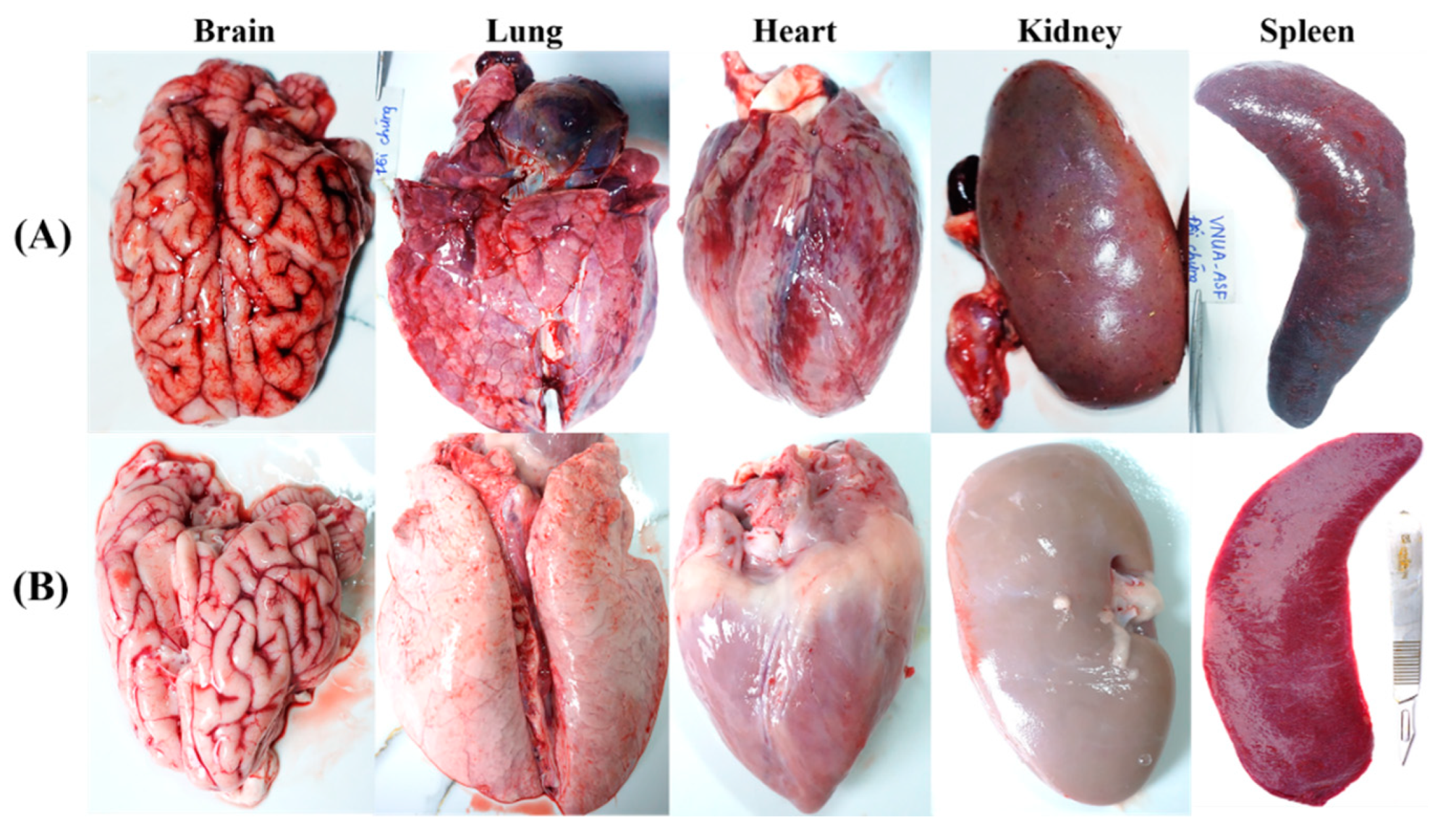

3.6. VNUA-ASFV-LAVL2 Vaccination prevents ASFV Replication and Pathological Lesions in Pigs

High titers (Ct value from 14.15 to 27.81) of ASFV were detected in multiple organs (brain, heart, lung, liver, stomach, spleen, kidney, bladder, tonsil, lymph node, and bone marrow) from the control pigs at 7-9 DPC (

Figure 5 and

Table 2). In contrast, pigs vaccinated with VNUA-ASFV-LAVL2 (from doses 10

2 HAD

50 to 10

5 HAD

50) had undetectable ASFV DNA in these organs by real-time PCR analysis (

Table 2) at 28 DPC.

Post

-mortem examination showed that non-immunized contol pigs displayed characteristic lesions and pathological signs of acute ASFV infection [

29]. Hemorrhages were observed in multiple organs including mandibular, pulmonary, mesenteric lymph nodes, renal cortex, pericardium, myocardium and cerebral meninges, with dark and enlarged spleen, swollen liver and gall bladder, and interstitial pulmonary oedema lung (

Figure 6A). In contrast, VNUA-ASFV-LAVL2 immunized pigs had no clinical and pathological signs or lesions in any of these organs (

Figure 6B).

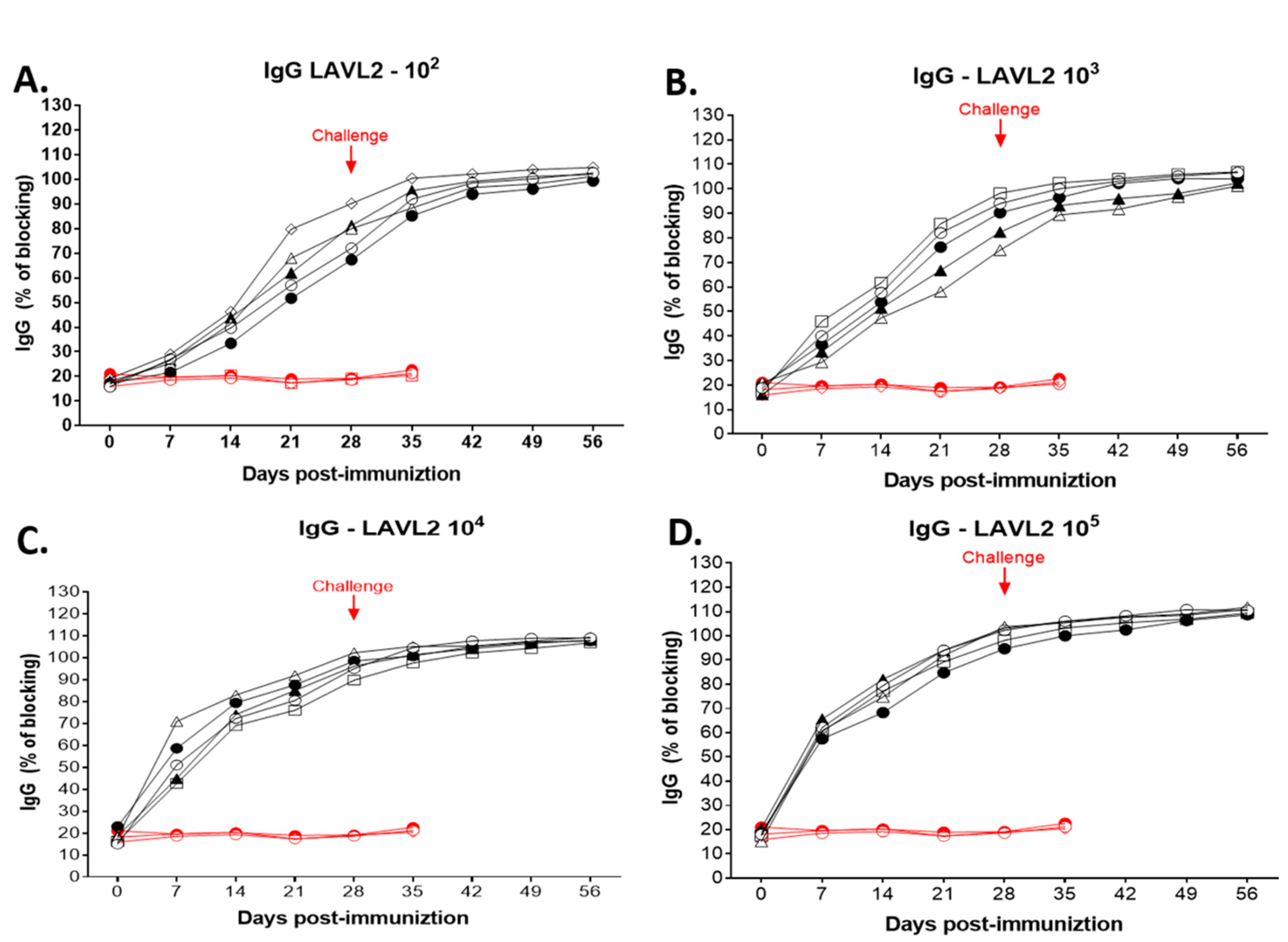

3.7. Pigs Vaccinated with VNUA-ASFV-LAVL2 Developed ASFV-Specific Antibodies after Vaccination and Challenge

As shown in

Figure 7, all vaccinated pigs developed ASFV-specific antibody after immunization. ASFV-specific antibodies were detected at 21 DPI (P<0.05) for low dose (10

2 HAD

50 and 10

3 HAD

50) immunized pigs (

Figure 7A,B), and at 7-14 DPI (P<0.01) for high dose (10

4 HAD

50 and 10

5 HAD

50) immunized pigs (

Figure 7C,D). At 28 DPI, the blocking percentage (%) of ASFV-specific antibodies reached approximately 87-102%, whereas no ASFV specific antibodies were detected in the control animals prior to the challenge. After the challenge, ASFV-specific antibody remained positive till the end of challenge observation period. ASFV-specific antibody was not detected in control pigs after the challenge.

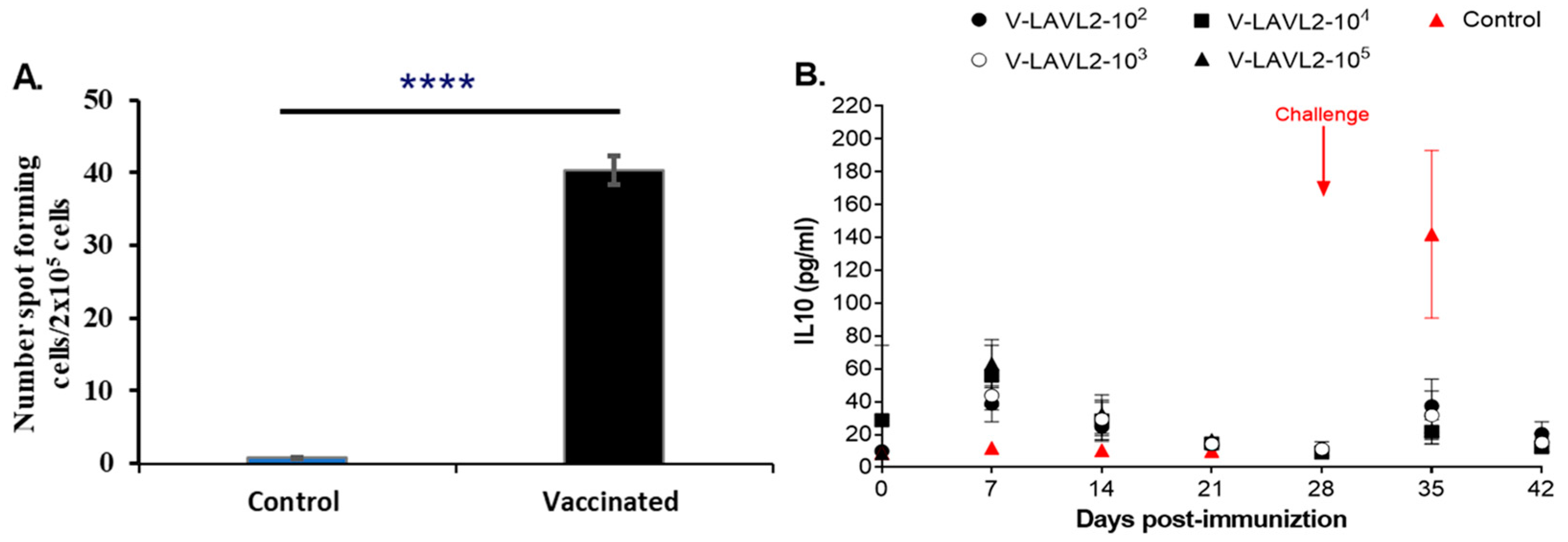

3.8. VNUA-ASFV-LAVL2 Induced Cellular Immunity in Vaccinated Pigs

ELISPOT assay results showed that PBMCs of VNUA-ASFV-LAVL2 vaccinated pigs produced IFN-γ after stimulation by the wild-type VNUA-ASFV-05L1. The numbers of spot forming cells from VNUA-ASFV-LAVL2 vaccinated pigs are significantly (p < 0.0001) higher than the cells from non-vaccinated pigs (

Figure 8A). Cytokine IL-10 ELISA analysis showed that vaccination of VNUA-ASFV-LAVL2 induced expression of IL-10 in pig serum and reach peak at 7 DPI. However, after challenge with the wild-type VNUA-ASFV-05L1, non-vaccinated control pigs showed significantly higher serum IL-10 levels than that of pigs vaccinated with VNUA-ASFV-LAVL2, and reach the peak at 7 DPC (35 DPI) (

Figure 8B).

4. Discussion

With the aim of developing a safe and efficacious ASF vaccine, we tried to generate LAVs by cell passage. 3D4/21 cell line is a single cell clone of 3D4 parent, a continuous cell line derived from porcine alveolar macrophages. It has been reported that 3D4/21 can support the growth of cell-adapted ASFV-Lisbon 61 and field isolate Lillie SI/85 [

30,

31], but was unable to maintain replication of the genotype II ASFV-HLJ/18 strain [

32]. However, a more recent study showed that the ASFV genotype II strain CN/GS/2018 can attach and enter into 3D4/21 cells and proceed to genome replication up to 10

6 copies/ml [

33]. Our result is consistent with this study. The cell-adapted genotype II ASFVs can infect and replicate efficiently in 3D4/21 with 1.25% final concentration of DMSO in the culture medium. We have developed several different LAV candidates using this technology and tested their safety in experimental pigs.

VNUA-ASFV-LAVL2 which derived from the field isolate (VNUA-ASFV-05L1, genotype II) showed one of the best attenuated phenotypes, and the best ability to induce protective immunity in pigs. Whole genome sequencing and analysis at passage 120 showed that VNUA-ASFV-LAVL2 harboring deletions of 13 known genes and 14 uncharacterized sequence deletions in MGF region of VNUA-ASFV-LAVL2 (

Table 1). VNUA-ASFV-LAVL2 can efficiently grow in both PAMs and 3D4/21 cells, and showed comparable growth kinetics with less than 0.5 log

10 at each time points post-infection compared to that of parental VNUA-ASFV-05L1 strain (

Figure 1). This phenomenon indicates that the deleted known genes and uncharacterized sequences play less role in the ASFV replication. Mutations or deletions in MGF region have been linked to replication ability and virulence attenuation of ASFV in cell culture and pigs [

19,

20,

21,

34,

35]. Therefore, it is not surprising that the deletion of these known MGF genes may play an important role in the attenuated phenotype of VNUA-ASFV-LAVL2 in experimental pigs. However, the replication and attenuation of VNUA-ASFV-LAVL2 in 3D4/21 cells may be associated with other deletions or mutations in the whole genome under the selective pressures during passaging in cells. To clarify the molecular mechanisms involved in the replication and attenuation of VNUA-ASFV-LAVL2, further investigations including comparison of the whole genome sequences of different passages of VNUA-ASFV-LAVL2 in 3D4/21 cells and their virulence in pigs are needed.

A variety of strategies have been described for developing ASFV LAVs that are able to persist for an extended period in host blood and tissues following immunization, and a correlation in terms of protection was found between enhanced clearance of virulent ASFV and persistence of LAVs [

12,

13,

23]. However, a potential drawback of using these LAVs in animals is the possibility of incomplete clearance of the vaccine strains that could result in reversion to virulence. Our findings from this study were particularly encouraging in that either the low doses (10

2 and 10

3 HAD

50) or the high doses (10

4 and 10

5 HAD

50) of VNUA-ASFV-LAVL2 were significantly attenuated and rapidly cleared from the blood, oral fluids and rectal feces of pigs, and the pigs were still able to sustain a protective immunity as evident from the challenge studies. VNUA-ASFV-LAVL2 was eliminated from blood by 28 DPI (

Figure 2), and from feces or oral fluids by 17 DPI (

Figure 3). Post-mortem examination showed that organs of VNUA-ASFV-LAVL2 immunized pigs had no clinical and pathological signs or lesions (

Figure 6). RT-PCR testing showed that VNUA-ASFV-LAVL2 was undetectable in these organs (

Table 2). These results collectively make VNUA-ASFV-LAVL2 an attractive and promising LAV candidate from both safety and efficacy perspectives. We further tested the safety of VNUA-ASFV-LAVL2 by passaging it in pigs with pooled serum samples which showed the highest ASFV RT-PCR Ct values from vaccinated pigs. VNUA-ASFV-LAVL2 remained safe and attenuated phenotype after five passages in pigs. The main reason for using serum sample instead of whole blood in the serial in vivo passage experiment in this study is our concern about the potential blood-related side effects (such as allergic reaction, fever, and so on), which may affect the observation of ASFV related clinical signs. However, serum samples only contain parts of ASFVs produced in the pigs. Next step, we will use the pool of whole blood samples and suspension of tissues to further test the safety (reversion-to-virulence) of VNUA-ASFV-LAVL2 in accordance with International Cooperation on Harmonisation of Technical Requirements for Registration of Veterinary Medicinal Products guideline 41 for the examination of live veterinary vaccines in target animals for absence of reversion to virulence (Reference number EMA/CVMP/VICH/1052/2004).

To identify correlates of protective immunity that could be used to predict the vaccine efficacy of VNUA-ASFV-LAVL2, we tested the humoral and cellular immune responses of pigs immunized by VNUA-ASFV-LAVL2. Pigs immunized with VNUA-ASFV-LAVL2 are capable of inducing ASFV-specific IgG antibodies. Studies have speculated that cellular immune responses may play an important role in ASFV protective immunity. In particular, a T helper cell type 1 (Th1) immune response (producing IFN-γ) seems crucial in the establishment of a protective response against ASFV [

36,

37,

38]. In this study, pigs vaccinated with VNUA-ASFV-LAVL2 possessed significantly higher number of ASFV-specific IFN-γ-producing cells than that in the non-vaccinated pigs. This observation is consistent with the previous reports [

36,

37,

38].

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Q.L.T., L.N.T., and J.S.; methodology, Q.L.T., J.S., L.W., R.M., Y.L, G.V.N.; formal analysis, Q.L.T., J.S., and L.W; investigation, Q.L.T., L.W., T.A.N., H.T.N., S.D.T., A.T.V., A.D.L., P.T.H., Y.T.N., L.T.L., T.N.V.,T.L.H.L., L.M.T.H., R.M., and Y.L.; resources, Q.L.T., L.N.T., J.S., T.A.N., H.T.N., S.D.T., A.T.V., A.D.L., P.T.H., and Y.T.N.; writing—original draft preparation, Q.L.T.; writing —review and editing, J.S., L.W., Q.L.T., and L.N.T.; supervision, Q.L.T., L.N.T., and J.S.; funding acquisition, Q.L.T., J.S., and L.N.T. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research is supported by Vietnam Ministry of Science and Technology, grant number [2012R1A1A4A01015303]; National Bio and Agro-Defense Facility Transition Fund, the USDA National Institute of Food and Agriculture, Hatch-Multistate project, grant number [1021491]; USDA ARS Non-Assistance Cooperative Agreements, grant numbers [58-8064-8-011, 58-8064-9-007, 58-3020-9-020, 59-0208-9-222]; USDA NIFA Award #2022-67015-36516 and USDA NIFA Subaward #25-6226-0633-002; National Pork Board Grant, grant number [18-059]; Department of Homeland Security, grant number [70RSAT19CB0000027].

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted according to the guidelines and approved protocols by Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC) at Vietnam National University of Agriculture (VNUA-2021/01) and at Kansas State University (IACUC#4845).

Informed Consent Statement

Not Applicable.

Data Availability Statement

All relevant data to support the findings described in the text are included in the main text. Additional data is available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Acknowledgments

We thank the research staff and student research groups in the Key Laboratory of Veterinary Biotechnology, Faculty of Veterinary Medicine, Vietnam National University of Agriculture for help with serological, molecular, and animal experiments. We thank the comparative Medicine staff and staff of Biosecurity Research Institute at Kansas State University for their technical help.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Dixon, L.K.; Stahl, K.; Jori, F.; Vial, L.; Pfeiffer, D.U. African swine fever epidemiology and control. Annu Rev Anim Biosci. 2020, 8, 221–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Karger, A.; Pérez-Núñez, D.; Urquiza, J.; Hinojar, P.; Alonso, C.; Freitas, F.B.; Revilla, Y.; Le Potier, M.F.; Montoya, M. An Update on African Swine Fever Virology. Viruses. 2019, 11, 864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Quembo, C.J.; Jori, F.; Vosloo, W.; Heath, L. Genetic characterization of African swine fever virus isolates from soft ticks at the wildlife/domestic interface in Mozambique and identification of a novel genotype. Transbound Emerg Dis. 2018, 65, 420–431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sánchez-Vizcaíno, J.M.; Mur, L.; Martínez-López, B. African swine fever (ASF): five years around Europe. Vet. Microbiol. 2013, 165, 45–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ge, S.; Li, J.; Fan, X.; Liu, F.; Li, L.; Wang, Q.; Ren, W.; Bao, J.; Liu, C.; Wang, H.; Liu, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Xu, T.; Wu, X.; Wang, Z. Molecular characterization of African swine fever virus, China, 2018. Emerg Infect Dis. 2018, 24, 2131–2133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cwynar, P.; Stojkov, J.; Wlazlak, K. African swine fever status in Europe. Viruses. 2019, 11, 310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruiz-Saenz, J.; Diaz, A.; Bonilla-Aldana, D.K.; Rodríguez-Morales, A.J.; Martinez-Gutierrez, M.; Aguilar, P.V. African swine fever virus: A re-emerging threat to the swine industry and food security in the Americas. Front Microbiol. 2022, 13, 1011891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, V.T.; Cho, K.H.; Mai, N.T.A.; Park, J.Y.; Trinh, T.B.N.; Jang, M.K.; Nguyen, T.T.H.; Vu, X.D.; Nguyen, T.L.; Nguyen, V.D.; Ambagala, A.; Kim, Y.J.; Le, V.P. Multiple variants of African swine fever virus circulating in Vietnam. Arch Virol. 2022, 167, 1137–1140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tran, H.T.T.; Truong, A.D.; Dang, A.K.; Ly, D.V.; Nguyen, C.T.; Chu, N.T.; Nguyen, H.T.; Dang, H.V. Genetic characterization of African swine fever viruses circulating in North Central region of Vietnam. Transbound Emerg Dis. 2021, 68, 1697–1699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Le, V.P.; Jeong, D.G.; Yoon, S.W.; Kwon, H.M.; Trinh, T.B.N.; Nguyen, T.L.; Bui, T.T.N.; Oh, J.; Kim, J.B.; Cheong, K.M.; Van Tuyen, N.; Bae, E.; Vu, T.T.H.; Yeom, M.; Na, W.; Song, D. Outbreak of African Swine Fever, Vietnam, 2019. Emerg Infect Dis. 2019, 25, 1433–1435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Zhao, S.; Zhang, H.; Qin, Z.; Shan, H.; Cai, X. Vaccines for African swine fever: an update. Front Microbiol. 2023, 14, 1139494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Z.; Chen, W.; Qiu, Z.; Li, Y.; Fan, J.; Wu, K.; Li, X.; Zhao, M.; Ding, H.; Fan, S.; Chen, J. African Swine Fever Virus: A Review. Life (Basel). 2022, 12, 1255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rock, D.L. Thoughts on African Swine Fever Vaccines. Viruses. 2021, 13, 943. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bosch-Camós, L.; López, E.; Rodriguez, F. African swine fever vaccines: a promising work still in progress. Porcine Health Manag. 2020, 6, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pikalo, J.; Porfiri, L.; Akimkin, V.; Roszyk, H.; Pannhorst, K.; Kangethe, R.T.; Wijewardana, V.; Sehl-Ewert, J.; Beer, M.; Cattoli, G.; Blome, S. Vaccination With a Gamma Irradiation-Inactivated African Swine Fever Virus Is Safe But Does Not Protect Against a Challenge. Front Immunol. 2022, 13, 832264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaudreault, N.N.; Richt, J.A. Subunit Vaccine Approaches for African Swine Fever Virus. Vaccines (Basel), 2019, 7, 56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brake, D.A. African Swine Fever Modified Live Vaccine Candidates: Transitioning from Discovery to Product Development through Harmonized Standards and Guidelines. Viruses. 2022, 14, 2619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borca, M.V.; Ramirez-Medina, E.; Silva, E.; Vuono, E.; Rai, A.; Pruitt, S.; Holinka, L.G.; Velazquez-Salinas, L.; Zhu, J.; Gladue, D.P. Development of a Highly Effective African Swine Fever Virus Vaccine by Deletion of the I177L Gene Results in Sterile Immunity against the Current Epidemic Eurasia Strain. J Virol 2020, 94, e02017-19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borca, M.V.; Rai, A.; Ramirez-Medina, E.; Silva, E.; Velazquez-Salinas, L.; Vuono, E.; Pruitt, S.; Espinoza, N.; Gladue, D.P. A Cell Culture-Adapted Vaccine Virus against the Current African Swine Fever Virus Pandemic Strain. J Virol. 2021, 95, e0012321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Donnell, V.; Holinka, L.G.; Gladue, D.P.; Sanford, B.; Krug, P.W.; Lu, X.; Arzt, J.; Reese, B.; Carrillo, C.; Risatti, G.R.; Borca, M.V. African Swine Fever Virus Georgia Isolate Harboring Deletions of MGF360 and MGF505 Genes Is Attenuated in Swine and Confers Protection against Challenge with Virulent Parental Virus. J Virol. 2015, 89, 6048–6056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, W.; Zhao, D.; He, X.; Liu, R.; Wang, Z.; Zhang, X.; Li, F.; Shan, D.; Chen, H.; Zhang, J.; Wang, L.; Wen, Z.; Wang, X.; Guan, Y.; Liu, J.; Bu, Z. A seven-gene-deleted African swine fever virus is safe and effective as a live attenuated vaccine in pigs. Sci China Life Sci 2020, 63, 623–634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tran, X.H.; Le, T.T.P.; Nguyen, Q.H.; Do, T.T.; Nguyen, V.D.; Gay, C.G.; Borca, M.V.; Gladue, D.P. African swine fever virus vaccine candidate ASFV-G-ΔI177L efficiently protects European and native pig breeds against circulating Vietnamese field strain. Transbound Emerg Dis. 2022, 69, e497–e504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Urbano, A.C.; Ferreira, F. African swine fever control and prevention: an update on vaccine development. Emerg Microbes Infect. 2022, 11, 2021–2033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, T.; Luo, R.; Sun, Y.; Qiu, H.J. Current efforts towards safe and effective live attenuated vaccines against African swine fever: challenges and prospects. Infect Dis Poverty. 2021, 10, 137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- de León, P.; Bustos, M.J.; Carrascosa, A.L. Laboratory methods to study African swine fever virus. Virus Res. 2013, 173, 168–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Truong, Q.L.; Nguyen, T.L.; Nguyen, T.H.; Shi, J.; Vu, H.L.X.; Lai, T.L.H.; Nguyen, V.G. Genome Sequence of a Virulent African Swine Fever Virus Isolated in 2020 from a Domestic Pig in Northern Vietnam. Microbiol Resour Announc. 2021, 10, e00193–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reed, L.J.; Muench, H. A simple method of estimating fifty percent end points. Am. J. Hyg. 1938, 27, 493–497. [Google Scholar]

- Haines, F.J.; Hofmann, M.A.; King, D.P.; Drew, T.W.; Crooke, H.R. Development and validation of a multiplex, real-time RT PCR assay for the simultaneous detection of classical and African swine fever viruses. PLoS One. 2013, 8, e71019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salguero, F.J. Comparative Pathology and Pathogenesis of African Swine Fever Infection in Swine. Front Vet Sci. 2020, 7, 282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weingartl, H.; Sabara, M.; Pasick, J.; van Moorlehem, E.; Babiuk, L. Continuous porcine cell lines developed from alveolar macrophages: Partial characterization and virus susceptibility. J Virol Methods. 2002, 104, 203–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meloni, D.; Franzoni, G.; Oggiano, A. Cell Lines for the Development of African Swine Fever Virus Vaccine Candidates: An Update. Vaccines (Basel). 2022, 10, 707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, T.; Wang, L.; Han, Y.; Pan, L.; Yang, J.; Sun, M.; Zhou, P.; Sun, Y.; Bi, Y.; Qiu, H. Adaptation of African swine fever virus to HEK293T cells. Transbound Emerg Dis. 2021, 68, 2853–2866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, Y.; Xia, T.; Bai, J.; Zhang, L.; Jiang, X.; Yang, X.; Zhang, K.; Jiang, P. African Swine Fever Virus Exhibits Distinct Replication Defects in Different Cell Types. Viruses. 2022, 14, 2642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, D.; Liu, Y.; Qi, X.; Wen, Y.; Li, P.; Ma, Z.; Liu, Y.; Zheng, H.; Liu, Z. African Swine Fever Virus MGF-110-9L-deficient Mutant Has Attenuated Virulence in Pigs. Virol Sin. 2021, 36, 187–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zani, L.; Forth, J.H.; Forth, L.; Nurmoja, I.; Leidenberger, S.; Henke, J.; Carlson, J.; Breidenstein, C.; Viltrop, A.; Hoper, D.; Sauter-Louis, C.; Beer, M.; Blome, S. Deletion at the 5’-end of Estonian ASFV strains associated with an attenuated phenotype. Sci Rep. 2018, 8, 6510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schäfer, A.; Franzoni, G.; Netherton, C.L.; Hartmann, L.; Blome, S.; Blohm, U. Adaptive cellular immunity against African swine fever virus infections. Pathogens. 2022, 11, 274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, L.; Wang, X.; Mao, R.; Zhou, Y.; Yin, J.; Sun, Y.; Yin, X. Research progress on live attenuated vaccine against African swine fever virus. Microb Pathog. 2021, 158, 105024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Franzoni, G.; Pedrera, M.; Sánchez-Cordón, P.J. African Swine Fever Virus Infection and Cytokine Response In Vivo: An Update. Viruses. 2023, 15, 233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Figure 1.

Growth curves of the VNUA ASFV-LAVL2 (passage 120) and parental VNUA-ASFV-05L1 in (A) PAMs and (B) 3D4/21 cells.

Figure 1.

Growth curves of the VNUA ASFV-LAVL2 (passage 120) and parental VNUA-ASFV-05L1 in (A) PAMs and (B) 3D4/21 cells.

Figure 2.

Rectal temperature and viremia of VNUA-ASFV-LAVL2 vaccinated pigs and parental VNUA-ASFV-05L1 inoculated control pigs. Daily rectal temperature of control pigs and vaccicated pigs with the dose of (A) 102, (C) 103, (E) 104, (G) 105 HAD50 of VNUA-ASFV-LAVL2, respectively. Daily viremia of control pigs and vaccinated pigs with the dose of (B) 102, (D) 103, (F) 104, (H) 105 HAD50 of VNUA-ASFV-LAVL2 strain, respectively. The dotted line represents the limit of detection.

Figure 2.

Rectal temperature and viremia of VNUA-ASFV-LAVL2 vaccinated pigs and parental VNUA-ASFV-05L1 inoculated control pigs. Daily rectal temperature of control pigs and vaccicated pigs with the dose of (A) 102, (C) 103, (E) 104, (G) 105 HAD50 of VNUA-ASFV-LAVL2, respectively. Daily viremia of control pigs and vaccinated pigs with the dose of (B) 102, (D) 103, (F) 104, (H) 105 HAD50 of VNUA-ASFV-LAVL2 strain, respectively. The dotted line represents the limit of detection.

Figure 3.

Viral titers in oral fluids swabs and rectal swabs of VNUA-ASFV-LAVL2 vaccinated pigs and parental VNUA-ASFV-05L1 inoculated control pigs. (A) shown are viral titers in oral fluids swabs. (B) shown are viral titers in rectal swabs. Data are mean ± SD for pigs per group. The dotted line represents the limit of detection.

Figure 3.

Viral titers in oral fluids swabs and rectal swabs of VNUA-ASFV-LAVL2 vaccinated pigs and parental VNUA-ASFV-05L1 inoculated control pigs. (A) shown are viral titers in oral fluids swabs. (B) shown are viral titers in rectal swabs. Data are mean ± SD for pigs per group. The dotted line represents the limit of detection.

Figure 4.

Safety of VNUA-ASFV-LAVL2 strain when passages in pigs. (A) shown are rectal temperatures of pigs from P2 to P5. (B) shown are Ct values of ASFV in blood samples of pigs from P2 to P5. Data are mean ± SD for pigs per group.

Figure 4.

Safety of VNUA-ASFV-LAVL2 strain when passages in pigs. (A) shown are rectal temperatures of pigs from P2 to P5. (B) shown are Ct values of ASFV in blood samples of pigs from P2 to P5. Data are mean ± SD for pigs per group.

Figure 5.

Rectal temperature and viremia of pigs after challenge with virulent VNUA-ASFV-05L1 genotype II strain. (A) Rectal temperature of vaccinated and nonvaccinated control pigs after challenged with standard dose of virulent VNUA-ASFV-05L1 strain. (B) Viremia of vaccinated and nonvaccinated control pigs after challenged with standard dose of virulent VNUA-ASFV-05L1 strain. (C) Rectal temperature of vaccinated, nonvaccinated and contact pigs after challenged with high dose of virulent VNUA-ASFV-05L1 strain. (D) Viremia of vaccinated, nonvaccinated and contact pigs after challenged with high dose of virulent VNUA-ASFV-05L1 strain. The dotted line represents the limit of detection.

Figure 5.

Rectal temperature and viremia of pigs after challenge with virulent VNUA-ASFV-05L1 genotype II strain. (A) Rectal temperature of vaccinated and nonvaccinated control pigs after challenged with standard dose of virulent VNUA-ASFV-05L1 strain. (B) Viremia of vaccinated and nonvaccinated control pigs after challenged with standard dose of virulent VNUA-ASFV-05L1 strain. (C) Rectal temperature of vaccinated, nonvaccinated and contact pigs after challenged with high dose of virulent VNUA-ASFV-05L1 strain. (D) Viremia of vaccinated, nonvaccinated and contact pigs after challenged with high dose of virulent VNUA-ASFV-05L1 strain. The dotted line represents the limit of detection.

Figure 6.

Pathological lesion findings of the organs of vaccinated and non-vaccinated pigs post-challenge at necropsy. (A) shown are pathological lesions of non-vaccinated control pigs. (B) shown are pathological lesions of pigs vaccinated with VNUA-ASFV-LAVL2.

Figure 6.

Pathological lesion findings of the organs of vaccinated and non-vaccinated pigs post-challenge at necropsy. (A) shown are pathological lesions of non-vaccinated control pigs. (B) shown are pathological lesions of pigs vaccinated with VNUA-ASFV-LAVL2.

Figure 7.

ASFV-specific antibodies were detected by ELISA only in pigs immunized with VNUA-ASFV-LAVL2. (A) ASFV-specific antibodies in serum samples of 102 HAD50 VNUA-ASFV-LAVL2 immunized pigs and control pigs. (B) ASFV-specific antibodies in serum samples of 103 HAD50 VNUA-ASFV-LAVL2 immunized pigs and control pigs. (C) ASFV-specific antibodies in serum samples of 104 HAD50 VNUA-ASFV-LAVL2 immunized pigs and control pigs. (D) ASFV-specific antibodies in serum samples of 105 HAD50 VNUA-ASFV-LAVL2 immunized pigs and control pigs. Black lines represent the pigs vaccinated with VNUA-ASFV-LAVL2. Red lines represent the non-vaccinated control pigs.

Figure 7.

ASFV-specific antibodies were detected by ELISA only in pigs immunized with VNUA-ASFV-LAVL2. (A) ASFV-specific antibodies in serum samples of 102 HAD50 VNUA-ASFV-LAVL2 immunized pigs and control pigs. (B) ASFV-specific antibodies in serum samples of 103 HAD50 VNUA-ASFV-LAVL2 immunized pigs and control pigs. (C) ASFV-specific antibodies in serum samples of 104 HAD50 VNUA-ASFV-LAVL2 immunized pigs and control pigs. (D) ASFV-specific antibodies in serum samples of 105 HAD50 VNUA-ASFV-LAVL2 immunized pigs and control pigs. Black lines represent the pigs vaccinated with VNUA-ASFV-LAVL2. Red lines represent the non-vaccinated control pigs.

Figure 8.

Figure 8. Cellular responses of VNUA-ASFV-LAVL2 vaccinated pigs and control pigs. (A) ELISPOT testing ASFV-specific IFN-γ-producing PBMCs at 28 DPI. (B) ELISA testing the serum IL-10 level of VNUA-ASFV-LAVL2 vaccinated pigs and control pigs during vaccination period and challenge period. p-values were determined by one-way ANOVA (**** p < 0.0001).

Figure 8.

Figure 8. Cellular responses of VNUA-ASFV-LAVL2 vaccinated pigs and control pigs. (A) ELISPOT testing ASFV-specific IFN-γ-producing PBMCs at 28 DPI. (B) ELISA testing the serum IL-10 level of VNUA-ASFV-LAVL2 vaccinated pigs and control pigs during vaccination period and challenge period. p-values were determined by one-way ANOVA (**** p < 0.0001).

Table 1.

Mutations of VNUA-ASFV-LAVL2 using the parental virus VNUA-ASFV-05L1 as a reference sequence.

Table 1.

Mutations of VNUA-ASFV-LAVL2 using the parental virus VNUA-ASFV-05L1 as a reference sequence.

| Genome position (bp) |

Mutation type |

Gene |

Nucleotide change |

Amino acid change |

Protein change |

| 3,797 |

Deletion |

MGF360-18R |

G |

P to R |

Disruption |

| 6,804 |

Substitution |

I7L |

T to A |

Y to N |

Single amino acid substitution |

| 12,450 |

Substitution |

I196L |

T to C |

I to I |

No change |

| 17,832 |

Deletion |

I267L |

A |

K to R |

Longer protein |

| 21,502 to 21,503 |

Substitution |

E199L |

AG to GA |

R to E |

Single amino acid substitution |

| 25,690 |

Substitution |

E184L |

A to G |

N to D |

Single amino acid substitution |

| 40,293 |

Substitution |

S237R |

A to G |

M to T |

Single amino acid substitution |

| 51,970 |

Substitution |

NP868R |

T to C |

Q to R |

Single amino acid substitution |

| 73,715 |

Substitution |

G1211R |

A to G |

V to A |

Single amino acid substitution |

| 84,062 |

Deletion |

Uncharacterized |

A |

Uncharacterized |

Uncharacterized |

| 99,910 |

Substitution |

C315R |

A to G |

V to A |

Single amino acid substitution |

| 105,303 |

Substitution |

C717R |

A to G |

V to A |

Single amino acid substitution |

| 108,102 |

Substitution |

Uncharacterized |

T to C |

Uncharacterized |

Uncharacterized |

| 113,352 |

Substitution |

EP402R |

T to C |

Y to C |

Single amino acid substitution |

| 123,504 |

Substitution |

K78R |

T to C |

N to S |

Single amino acid substitution |

| 133,757 |

Substitution |

A179L |

T to C |

M to T |

Single amino acid substitution |

| 140,235 |

Deletion |

A104R |

T |

K to S |

Disruption |

| 147,561 |

Substitution |

MGF505-6R |

A to G |

V to A |

Single amino acid substitution |

| 161,147 |

Deletion |

Uncharacterized |

A |

Uncharacterized |

Uncharacterized |

| 161,392 |

Deletion |

MGF360-10L |

A |

E to D |

Disruption |

| 166,165 |

Deletion |

MGF300-2R |

G |

D to I |

Disruption |

| 168,120 to168,159 |

Deletion |

Uncharacterized |

Deletion |

Deletion |

Deletion |

| 168,160 to168,369 |

Deletion |

X69R |

Deletion |

Deletion |

Deletion |

| 168,370 to 169,247 |

Deletion |

Uncharacterized |

Deletion |

Deletion |

Deletion |

| 169,248 to 170,375 |

Deletion |

MGF360-6L |

Deletion |

Deletion |

Deletion |

| 170,376 to 171,191 |

Deletion |

Uncharacterized |

Deletion |

Deletion |

Deletion |

| 171,192 to 172,355 |

Deletion |

MGF360-4L |

Deletion |

Deletion |

Deletion |

| 172,356 to 172,535 |

Deletion |

Uncharacterized |

Deletion |

Deletion |

Deletion |

| 172,536 to 173,360 |

Deletion |

MGF110-13L |

Deletion |

Deletion |

Deletion |

| 173,361 to173,445 |

Deletion |

Uncharacterized |

Deletion |

Deletion |

Deletion |

| 173,446 to 173,805 |

Deletion |

MGF110-12L |

Deletion |

Deletion |

Deletion |

| 173,806 to 173,994 |

Deletion |

Uncharacterized |

Deletion |

Deletion |

Deletion |

| 173,995 to 174,360 |

Deletion |

MGF110-14L |

Deletion |

Deletion |

Deletion |

| 174,361 to 174,449 |

Deletion |

Uncharacterized |

Deletion |

Deletion |

Deletion |

| 174,450 to 174,809 |

Deletion |

MGF110-11L |

Deletion |

Deletion |

Deletion |

| 174,810 to 175,099 |

Deletion |

Uncharacterized |

Deletion |

Deletion |

Deletion |

| 175,100 to 175,972 |

Deletion |

MGF110-9L |

Deletion |

Deletion |

Deletion |

| 175,973 to 176,130 |

Deletion |

Uncharacterized |

Deletion |

Deletion |

Deletion |

| 176,131 to 176,505 |

Deletion |

MGF100-1R |

Deletion |

Deletion |

Deletion |

| 176,506 to 176,722 |

Deletion |

Uncharacterized |

Deletion |

Deletion |

Deletion |

| 176,723 to 177,106 |

Deletion |

MGF110-8L |

Deletion |

Deletion |

Deletion |

| 177,107 to 177,234 |

Deletion |

Uncharacterized |

Deletion |

Deletion |

Deletion |

| 177,235 to 177,519 |

Deletion |

285L |

Deletion |

Deletion |

Deletion |

| 177,520 to 177,833 |

Deletion |

Uncharacterized |

Deletion |

Deletion |

Deletion |

| 177,834 to 178,247 |

Deletion |

MGF110-7L |

Deletion |

Deletion |

Deletion |

| 178,248 to 178,453 |

Deletion |

Uncharacterized |

Deletion |

Deletion |

Deletion |

| 178,454 to 179,071 |

Deletion |

MGF110-5L-6L |

Deletion |

Deletion |

Deletion |

| 179,072 to 179,259 |

Deletion |

Uncharacterized |

Deletion |

Deletion |

Deletion |

| 179,260 to 179,634 |

Deletion |

MGF110-4L |

Deletion |

Deletion |

Shorter protein |

Table 2.

Detection of ASFV in organs of vaccinated and control pigs after challenge.

Table 2.

Detection of ASFV in organs of vaccinated and control pigs after challenge.

| Groups |

Pig no. |

Challenge dose |

Real-time PCR (Ct value) |

| Brain |

Heart |

Lung |

Liver |

Stomach |

Spleen |

Kidney |

Bladder |

Tonsil |

ILN |

MLN |

SLN |

BM |

| 102 HAD50 vaccinated |

28 |

1x103 HAD50 of VNUA-ASFV-05L1 |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

| 29 |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

| 30 |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

| 103 HAD50 vaccinated |

41 |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

| 42 |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

| 43 |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

| 104 HAD50 vaccinated |

46 |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

| 48 |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

| 49 |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

| 105 HAD50 vaccinated |

53 |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

| 54 |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

| 55 |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

| Controls |

36 |

22.56 |

18.35 |

17.29 |

19.62 |

25.31 |

14.87 |

18.39 |

26.53 |

21.69 |

19.36 |

22.04 |

18.65 |

26.75 |

| 37 |

21.75 |

20.47 |

18.23 |

21.29 |

24. 37 |

15.31 |

20.62 |

24.87 |

23.59 |

21.29 |

22.59 |

19.54 |

27.81 |

| 38 |

21.18 |

19.59 |

18.62 |

20.47 |

25.59 |

14.15 |

19.57 |

25.18 |

21.37 |

20.57 |

23.18 |

20.47 |

27.17 |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).