1. Introduction

Hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) is a global health issue in modern world and causes more than 600,000 deaths throughout the world per anum. Among cancers, HCC is the 5th most common type of cancer prevailing worldwide and the mortality is increasing day by day due to poor prognosis and therapeutic options availability [

1]. The incidence of HCC is slow and gradual that is why it can be diagnosed at an early stage but the survival rate is 60-70% due to ineffective treatment [

2,

3,

4]. Till the FDA approval of sorafenib for the systemic treatment of HCC there were no such therapeutic agents to properly treat the condition. It has been used for more than ten years for the targeted therapy of HCC [

5,

6].

Renal cell carcinoma (RCC) is actually a group of tumors which originates from highly diffused heterogeneous epithelium of renal tubules. After bladder and prostate cancer it is the third most common cancer as far as urological malignancy is concerned and accounts about 3% of all cancers [

7,

8]. The mortality rate is high i.e., ˃ 100,000 per anum and the incidence is ≥ 200,000 cases per anum [

8]. It is more common in men as compared to women i.e., 1.5 times higher and its presentation is higher in median age of 62 [

9,

10].

Pluronic F-127 having an amphiphilic characteristics is a tri-block (PEO-PPO-PEO), non-ionic surfactant, developed from two basic monomeric units i.e., poly ethylene oxide(hydrophobic) and poly propylene oxide (hydrophilic). Due to its biocompatible and non-toxic nature it is used as a drug carrier in many forms of cancer and skin diseases. Pluronic F-127 also inhibits efflux transport protein system (p-glycoprotein), resulting in increased permeation and diffusion of active compounds inside the tumor cells and ultimately stability of the compound [

11,

12].Pluronic F-127 can overcome the multidrug resistance (MDR) in cancers throughglutathione/glutathione-S-transferase detoxification system [

13]. The nanoparticles are usually phagocytized when recognized by the host immune system (Reticulo-endothelial System), and as a result are eliminated from the body. Therapeutic efficacy particularly in cancerous cells can be increased by prolonging circulation half-life and targeting the affected organ. This can be achieved by surface modification of nanoparticles with hydrophilic polymer or surfactants. Alternately, the biodegradable co-polymer such as pluronic/poloxamer, poly vinyl alcohol (PVA) and polyethylene glycol (PEG)are used as surface modifiers in order to decreases the opsonization of the nanoparticles by the macrophage system [

14].

As a chemotherapeutic agent sorafenib (SFB) has proven efficacy against various types of cancers such as HCC, RCC, thyroid cancer, soft tissue sarcoma, melanoma, cholangiocarcinoma and acute myeloid leukemia[

15]. SFB use is marred by its side effects which include hand-foot syndrome, diarrhea, nausea and fatigue. Reduced water solubility is another factor which has limited SFB use. To minimize the side effects of SFB, controlled and targeted drug delivery to the tumor can be achieved by using nanoformulation technology [

16]. PLGA is a synthetic, biodegradable and biocompatible polymer. Apart from its use in drug delivery systems, it is also used in sutures[

17], bone fixation and screws materials [18-20]. Krebs cycle is responsible for the removal of PLGA from the body without affecting the normal physiology of the body [

21]. PLGA effectiveness is dependent on the cell environment and fusion with lysosomes [

21,

22].

Nanoformulations containing biocompatible and biodegradable polymers improved the

in-vivo parameters such as pharmacokinetics and biodistribution resulting in enhanced chemotherapeutic effects [

23,

24]. Studies have revealed that EPR effect is responsible for increased accumulation of nanoparticulate in solid tumors [

25,

26]. Nanoparticles can also modulate the efflux of drug from tumor by overcoming MDR mediated by P-glycoprotein resulting in increased level of the drug inside the tumors [

27,

28,

29].

The polymeric nanoformulations have some drawbacks such as non-gradual and non-consistent drug release, stability problems and hemolytic activity. Embolization of vessels and local toxicities at the site of injection are problems associated with intravenous administration of hydrophobic anti-cancer drugs such as sorafenib.

2. Results

2.1. Physiochemical Characterization

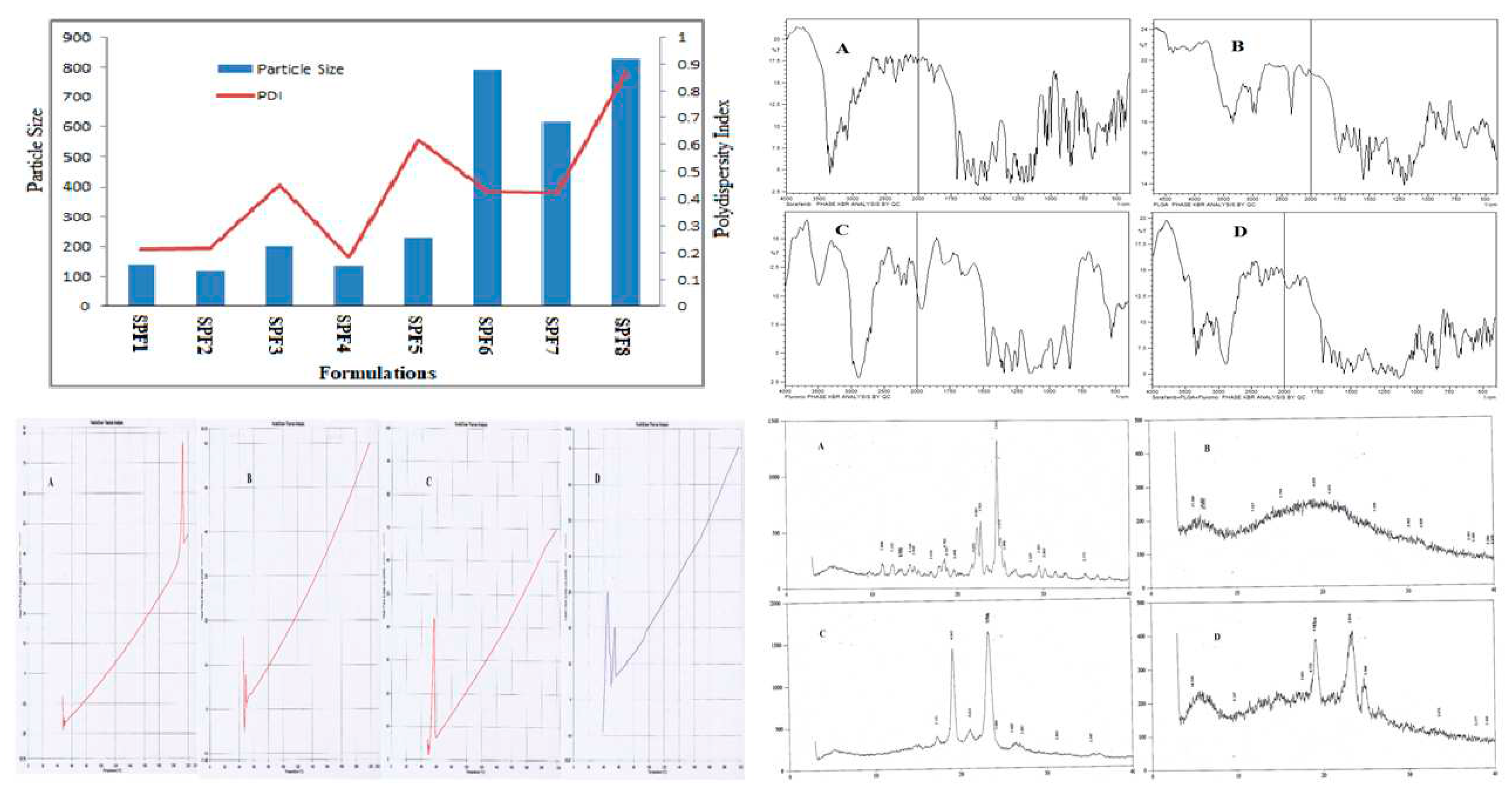

2.1.1. Dynamic Light Scattering

The quantity (10 mg) of Pluronic F-127 (1%) and PLGA was kept constant in the formulations. The particle size and PDI were in the range of 120-1792 nm and 0.184-0.874 as described in

Table 1. The increase in SFB concentration was directly proportional to the nanoparticles size. The monodispersity of the particles was changed to polydispersity down the table (0.214 to 0.874) as the concentration of the drug was increased as shown in

Table 1[

30].

Formulation prepared with pluronic showed negative zeta potential and it decreased as the concentration of drug has been increased. The values varied in between -10.7 to -4.8 mV (

Table 1).

2.1.2. Encapsulation Efficiency and Drug Loading

Pluronic is one of the most common stabilizers used because it encapsulates both hydrophilic and hydrophobic drugs. The values for %EE ranged from 99% to 60% while the %DL loading values are dependent on the drug to polymer ratios and varied in the range of 9.7 to 56.7 as shown in Table1.

2.1.3. FTIR analysis

The characteristic wave number for SFB were at 1598 cm−1 for carboxylic acid/derivatives, 3080 cm−1for C=CH2, 3288 cm−1 for high concentration of -OH and the -C=O double bond was observed at about 1740 cm-1. The presence of specific IR frequencyat1116cm−1 and 1384cm−1 was for C=C stretching of aromatic amine group. The PLGA 75:25 gave its characteristic bands such as OH stretching (3200-3500 cm-1), –CH (2850-3000 cm-1), carbonyl –C=O stretching (1700-1850 cm-1) and C–O stretching (1050-1250 cm-1).

The band located at 1100 cm

-1 was a characteristic peak for C–O–C stretching vibrations, while an -OH group trough was observed at 3200-3500 cm

-1 in pluronic F-127 as shown in

Figure 1.

2.1.4. Differential Scanning Calorimetry

These studies were carried out to determine the crystalline, disordered crystalline, and amorphous nature of PLGA, SFB and pluronic F-127.

The endothermic peaks of PLGA at 50 °C, and SFB at 210 °C confirming their amorphous and crystalline nature, respectively while Pluronic F-127 showed one endothermic peak at 55 °C[

31].

2.1.5. X-Ray Diffractometry

X-Ray diffraction studies were carried out at 3° (2θ) to 40° (2θ) using an XRD.

Peaks of SFB were detected at 22.7˚ and 24.8˚ (2θ) confirming its crystalline nature, while no peak was detected for PLGA [

32]. Similarly pluronic was detected at 19˚ and 23˚(

Figure 1), which were in accordance with the published standard powder X-ray diffraction pattern of PEO [

33].

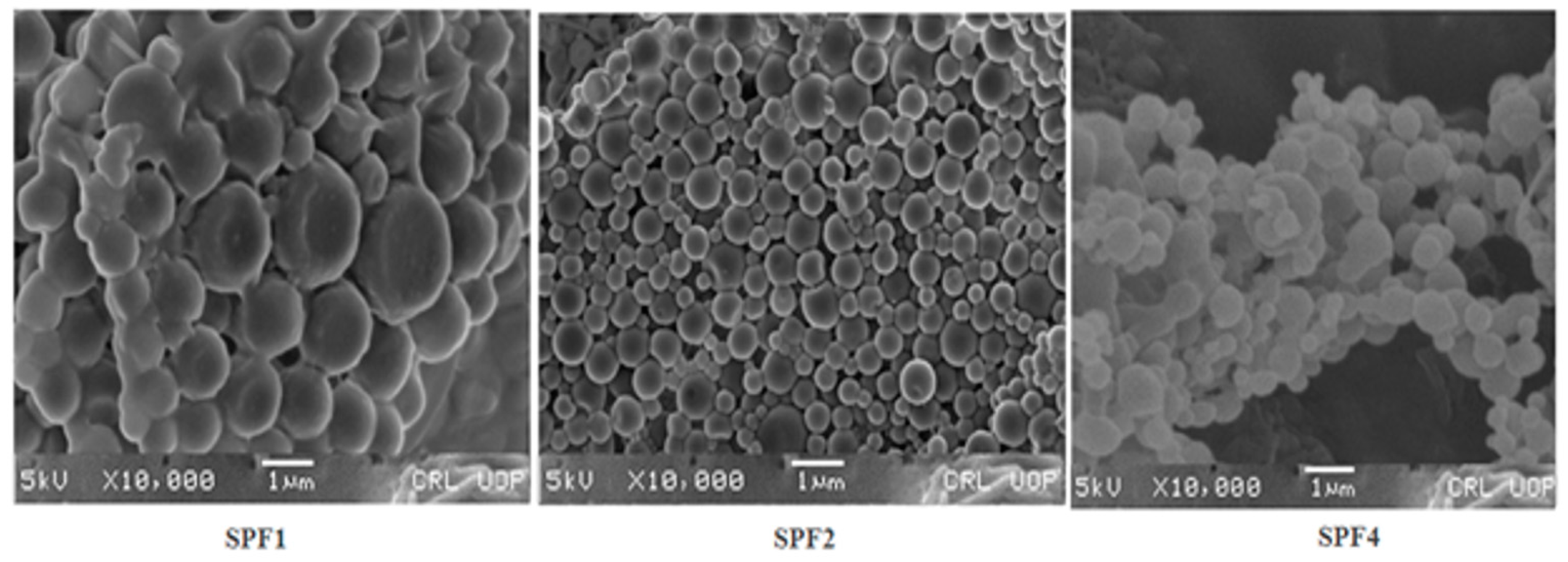

2.1.6. Scanning Electron Microscopy

The circulation time, cellular uptake and targeting of the tumor depend on the size, and morphology of the nanoparticles. These also affect the margination and adhesive properties of nanoparticles in blood vessels[

34,

35].

The nanoparticles prepared with Pluronic F-127(1%), were spherical in shape (

Figure 2), and remained stable for a longer period as confirmed by scanning electron microscopy.

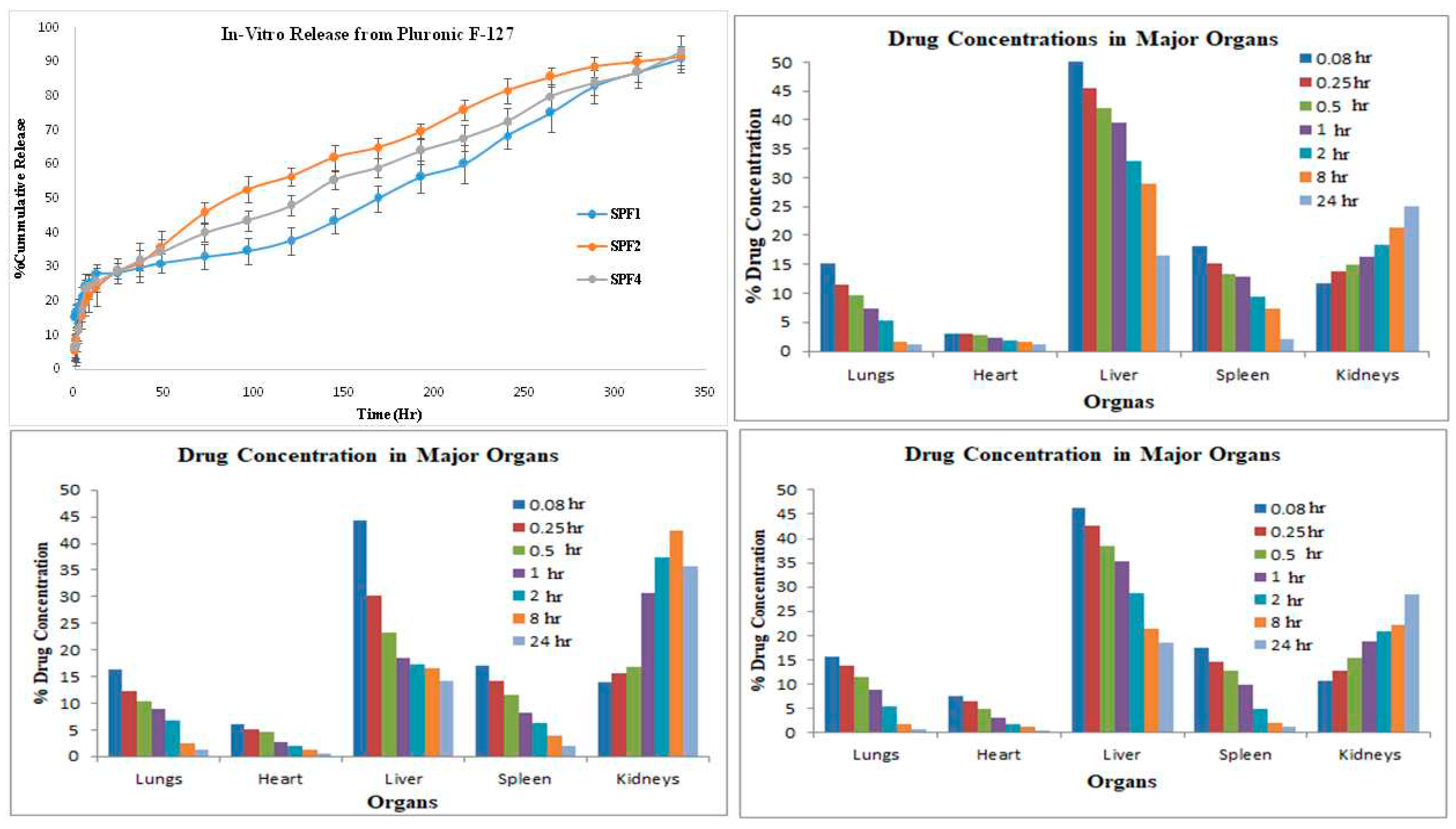

2.1.7. In-vitro Drug release kinetics

The release kinetics ofSPF2 and SPF4, formulations best fits to Higuchi model, while SPF1follow zero order kinetics as represented by regression coefficient (R

2) values. The “n” value represents the release mechanism of SFB from the formulations and is calculated at 60% release concentration as given in

Table 2. Diffusion followed by erosion is the most prevailing mechanism [

36].

The Higuchi and zero order models are the best to describe the transport and the release of SFB while the Korsemyer Peppas is a decisive model among all the models[

37].

2.1.8. In-vivo Drug Analysis

In-vivo studies were performed by observing the distrubition of nanoformulation throughout the body and evaluating pharmacokinetic parameters in the test animals. The SFB nanoformulations were injected intravenously to the rabbits and then its distribution in different organs and blood vessels was observed by gamma imaging and the pharmacokinetic parameters were evaluated after collection blood samples at specific time intervals.

The distribution of control SFB solution and SFB-PLGA nanoparticles in target organs was different. The clearance of control (SFB solution)was quicker as compared to its PLGA-nanoparticles due to increase mean residence time (MRT) of the nanoformulation (

Table 3).The radioactivity of blood has also been increased in case of nanoparticles formulations.

Distribution of SFB nanoparticles formulation (

Table 3, 4 and

Figure 3) was higher in liver as compared to control solution due to their smaller size (≤ 200 nm). The sterically stabilized small nanoparticles can easily penetrate into the endothelial lining of the liver. This make such nanoformulations to be used for targeting and treating the liver carcinoma [

38].

The uptake of control solution by spleen was initially higher in comparison with SFB nanoformulation. The control solution was eliminated quickly as compared to the nanoformulations.

The pharmacokinetic parameter suggested the higher circulation time of the SFB nanoparticles and decreased clearance might be helpful in the treatment of local tumors [

39]. The radioactivity of SFB nanoparticles in the heart is lower as compared to free control solution. Encapsulating SFB in nanoparticles can reduce the cardiotoxicity significantly [

40].

This distribution of SFB-PLGA nanoparticles in the lung has been increased while its clearance was decreased as compared to control solution. The formulation developed can therefore be used to treat lung cancer [

41].

3. Discussion

The increase in nanoparticles size is due to greater quantity of drug in the nano-emulsion droplets and saturation solubility of the internal phase in the external phase [

42].The concentration of the SFB in the internal organic phase is higher, which made viscous and larger emulsion droplets and resulted in larger nanoparticles.

The ester group of the PLGA chains on the surface particles and pluronic(PEO-PPO) was responsible for the negative potential of the nanoparticles which is also reported in other studies [

43]. The long hydrophilic chain in pluronic is responsible for the high negative potential values [

30]. The presence of negative charge improve the stability of nanoparticles i.e. electrostatic repulsion to form agglomerates which results in increased circulation time and increased cellular uptake due to the enhanced non-specific cell membrane affinity [

44].For the efficient accumulation nanoparticles at the tumor site, the particle size should be ~ 150nm with a zeta potential of ~ -15 mV as compared to more negative or positive particles or bigger particles[

45].The %EE has not been altered significantly by changing the ratio of SFB to polymer. The %DL to the polymer was efficient as compared other biodegradable polymers [

13].

The FTIR spectra revealed no interaction between the peaks/bands except a slight decrease in -OH stretching. It might be due to hydrogen bonding as –OH group is there in both PLGA and Pluronic. The main bands of pure PLGA remained the same, demonstrating that there was no interaction among the SFB, excipients and polymer as shown in the

Figure 1. It was further supported by thermograms obtained from DSC that the nanoformulations and physical mixtures of PLGA and pluronic F127 were unchanged showing no change in the structure of the polymer and stabilizer (

Figure 1).The two peaks in observed in XRD pattern confirmed the crystalline nature of the pluronic and formulation/physical mixture of SFB, PLGA and pluronic, however, the intensities showing the semi-crystalline nature of pluronic in the nanoformulations.

The SEM imaging showed (

Figure 2) that nanoparticles were spherical in shape and spherical particles are more stable thermodynamically, freely circulate in vessels, releasing drug in a sustained manner and having enhanced cellular uptake capabilities [

46,

47]. The change in external morphology of the different nanoparticles prepared with various emulsifiers is insignificant.

The bi-phasic release pattern has been shown by the developed nanoformulations (

Figure 3) consists of initial burst release in first 24 hours followed by sustained release, which are supported by the previous study[

48]. This initial phase is due to the entrapped drug on the surface of the nanoparticles, while the second phase the diffusion and erosion mechanisms are involved [

49]. The nanoparticles having smaller size release the drug more rapidly. However degradation of the polymer is dependent on the nature of and diameter of the polymer as polymers with larger diameter are degraded slowly [

50].

The possible mechanism for higher concentration of PLGA-SFB nanoformulations in target organs might be due to the phagocytic uptake of RES and therefore, it can passively target these organs. The pharmacokinetic data of the nanoformulation revealed that the nanoparticles have improved bioavailability (increased AUC, Cmax and MRT) while the clearance was decreased which will help in the treatment of local tumors [

39]. In this study, it is obvious that nanoparticles with smaller size can easily deliver to the target organs [

41].

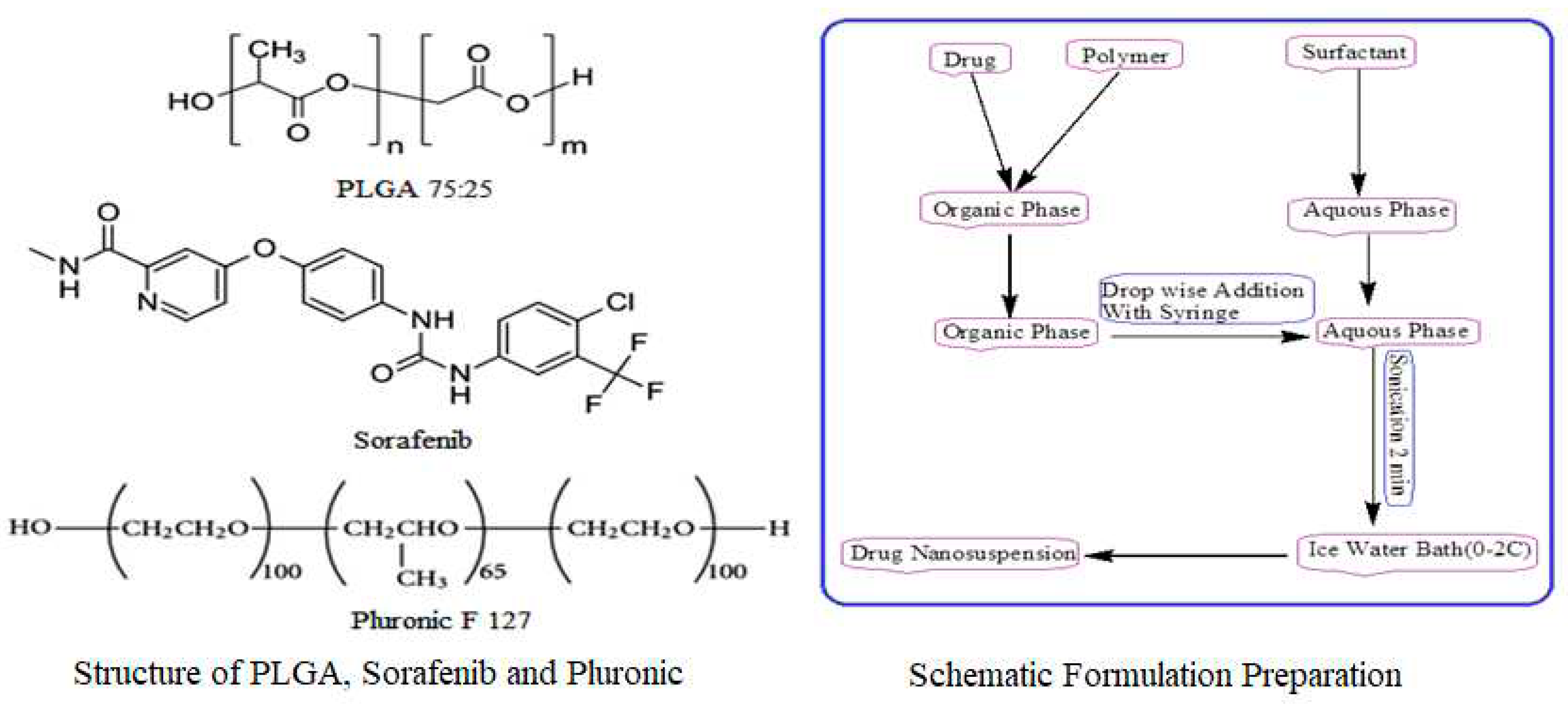

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Chemicals and equipment

Sorafenib, and Sodium Bicarbonate were purchased from Fluka, while Ethanol and Dimethyl Sulfoxide, Dialysis Tubing, Pluronic (F-127), Tween-80,Potassium Chloride, Sodium Chloride, Potassium Di-hydrogen Phosphate, Distilled water, HPLC-grade solvents, methanol acetonitrile were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich, Germany. PLGA was obtained from Evonik Germany. Ultra-pure distilled and De-ionized water was used in the study.

Probe Sonicator(Sanyo, UK.)., Vortex Mixer (Fisher Scientific®, USA) Magnetic Stirrer (Benchmark®, USA), Centrifuge (Centurion® Scientific, UK), shaking water bath (Korea), Zeta Sizer (Malvern Zetasizer ZS-90, U.K), Freeze Dryer (Telstar Cryodos-50, USA), Differential Scanning Calorimeter (Perkin Elmer, USA), X-Ray Diffractometer (JEOL, Japan), FTIR (Shimadzu, Japan), Scanning Electron Microscope (Jeol Japan), and UV-Visible Spectrophotometer (Perkin Elmer Series 200, Lambda, 25 using UV) were used in the study.

4.2. Preparation of Plain and Drug Loaded Nanoparticles

Modified solvent evaporation method was used for the preparation of nanoformulations. PLGA (75:25), 10 mg was dissolved in 3 ml ethyl acetate and 2 ml acetonitrile with varying concentration of sorafenib (1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8 mg). 1 % solution of stabilizer was prepared in water rand 10ml of it was utilized for formulation preparation as shown in

Figure 4. This was followed by adding drop-wise 5 ml of organic phase to 10 ml of aqueous solution of stabilizer with slow magnetic stirring at the rate of 70-80 rpm. The organic and aqueous mixture was then sonicated for 2 min by using a probe sonicator set at 99% level, under iced water bath using 15 W power. The organic phase was then removed through slow magnetic stirring, followed by high speed centrifugation at 15000 rpm for 30 min at 4 ˚C for nanoparticles collection. The nanoparticles were first washed thrice with sterile water and then lyophilized for future use and stability studies. PLGA nanoparticles without SFB were prepared in the same way.

4.3. Physicochemical Characterization

4.3.1. Dynamic Light Scattering

Malvern zeta sizer was used to find out the size, polydispersity (PDI) and zeta potential of nanoparticles, using dynamic light scattering technique. The nanoformulations samples can be analyzed as such or can be diluted if required with distilled water and the analysis is carried out at 25 °C with a 90° scattering angle. By using Malvern software average diameter and PDI were calculated. Statistical calculations for size and PDI were carried out in triplicate. The software of instruments was adjusted in such a way that it itself has taken the average of three readings and each reading has passed through 100 runs. Zeta potential actually determines the nanoparticles stability in dispersion.

4.3.2. Fourier Transform Infra-Red analysis

The FTIR spectroscopy was performed for the confirmation of polymer, drug and excipients and also to evaluate their compatibility. PerkinElmer spectrum BX FTIR (Waltham, MA, USA) was used for analysis and sample was prepared by potassium bromide (KBr) disc. For sample preparation 2mg of SFB was mixed with 100 mg KBr in a mortar and pestle. The mixture was compressed to obtain a pellet. The samples were analyzed at 4000-400 cm-1 against a blank KBr pellet with a resolution of 1.0 cm-1and the baseline correction was performed.

4.3.3. Differential Scanning Calorimetry

Sorafenib (API), PLGA, pluronic F-127, their physical mixture and lyophilized nanoformulations powder were analyzed by differential scanning Calorimetry (DSC). In the aluminium pan 10 mg sample was placed and sealed. Scanning was performed using a similar empty pan as a reference under nitrogen at a 10 ˚C/min heating rate. The temperature and energy scale of the instrument is calibrated using a standard aluminum material.

4.3.4. X-Ray Diffractometry

Crystalline/semi-crystalline or amorphous nature of SFB,PLGA, Pluronic F-127, physical mixture and NPs formulations was determined through XRD at 3° (2θ) to 40° (2θ).In order to control the curves, the amount of power must be in same quantity.

4.3.5. Scanning Electron Microscopy

The lyophilized powder was placed on the upper side of brass made stub and extra sample was removed by blade crapping. Sputtering technique was used to coat the sample with gold and this procedure was carried out for 1.30 min at 40 dm Ampunder vacuum (argon gas). Then it was placed in sample holder of scanning electron microscope (JSM-5910, Jeol Japan) to analyze its morphology (7 samples at a time).

4.3.6. Drug Entrapment Efficiency

To find out the drug entrapment efficiency, percent encapsulation efficiency (% EE) and percent drug loading (% DL) were found out. The developed nanoformulations were evaluated by centrifuging the sample at 30 ºC and 15000 rpm for 30 min. After centrifugation free amount of SFB present in the supernatant was determined by UV-Vis spectrophotometer at 271.10 nm. The following equations were used for %EE of SFB and %DL [

51]:

4.3.7. Formulation Optimization4.3.8. In-vitro Drug release

The release profile of the developed nanoparticles was determined by re-dispersing the lyophilized nanoparticles in 2 ml of PBS(pH 7.4),and placed in cellulose membrane (MW cutoff = 12-14 k Da) immersed in 100 ml of PBS at 37 °C in a water bath with gentle shaking at 100 rpm. Samples were collected at specified time intervals and volume was replaced PBS. The content of SFB was determined by UV-Visible spectrophotometer. The measurements were made in triplicate and then cumulative percent drug release was calculated.

4.3.9. In-vivo Drug Analysis

4.3.9.1. Imaging studies

The nanoformulations of SFB (150 μl) were incubated with 80 μl stannous chloride solution (reducing agent) at ambient temperature for 20 min and further incubated for 10 min with technetium-99m (300 μl). Loading efficiency of the radiolabelled formulation (2ml) was evaluated by TLC through Whattman paper No 1 using acetone as a mobile phase. Gamma counter was used in order to check the percent radioactivity of the formulation[

52].

4.3.9.2. Pharmacokinetic Evaluation

In-vivo studies were carried out in rabbits models weighing 2± 0.5 kg obtained from National Institute for Health (NIH), Islamabad, Pakistan. Approval of the experiments was taken from the Departmental Ethical committee, University of Peshawar vide letter number Pharm/8567.Water and food were provided and animals withany discomfort were excluded from the study.

5. Conclusions

The developed nanoformulation of SFB revealed that nanoparticles with desired physicochemical properties can be prepared by using different stabilizing agents in various concentrations. The development and optimization process used in this study were suitable for BCS-Class II drugs (hydrophobic drugs). Because of poor solubility these drugs have decreased bioavailability. Preparation of nano-drug delivery system may increase bioavailability, which will result in reduced dose, dosing frequency and may improve drug targeting. The idea can be utilized for other such problematic drugs, to carry them to their site of action.

The results of this study have shown higher concentration of nanoparticles in liver and kidney, so it can be utilized for the treatment of hepatic and renal malignancies. The study also suggests that by controlling the physicochemical characteristics such as smaller size (< 200 nm) and negative zeta potential tumor targeting of anticancer agents can be achieved through EPR effect. Further studies are recommended to investigate the antitumor, and tumor regression activities of SFB nanoparticles for the optimization of polymeric nanoparticles.

Author Contributions

“Conceptualization, Z.I.; I.K and A.K.; methodology, I.K.; formal analysis, L.A.; data curation, A.K.; writing—original draft preparation, I.K.; writing—review and editing, A.K.; and S.A.K.; supervision, Z.I.; funding acquisition, M.K. All authors have read and approved the final manuscript for publication.

Funding

“This research and APC was funded by the Researchers Supporting Project Number (RSP2023R301), King Saud University, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia.

Institutional Review Board Statement

“The animal study protocol was approved by the Ethical Committee of Department of Pharmacy, University of Peshawar vide letter number Pharm/8567, dated November 25, 2014.

Informed Consent Statement

“Not applicable.”

Data Availability Statement

The quantitative laboratory data used to support the findings of this study are included within the article. The supporting data of this study are available from corresponding author, Dr. Abad Khan upon request.

Acknowledgments

We are also thankful to the Higher Education Commission of Pakistan for facilitating the scholar.

Conflicts of Interest

“The authors declare no conflict of interest.”

References

- J.M. Llovet. Sorafenib in advanced hepatocellular carcinoma. New Engl J Med 2008, 359, 378–390. [CrossRef]

- J. Bruix.; J.M. Llovet. Major achievements in hepatocellular carcinoma. The Lancet 2009, 373, 614–616. [CrossRef]

- J. Bruix.; M. Sherman. Management of hepatocellular carcinoma. Hepatology 2005, 42, 1208–1236. [CrossRef]

- Bruix, J. Conclusions of the Barcelona-2000 EASL conference: European Association for the Study of the Liver. J Hepatol 2001, 35, 421–430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- J.M. Llovet.; J. Bruix. Systematic review of randomized trials for unresectable hepatocellular carcinoma: chemoembolization improves survival. Hepatology 2003, 37, 429–442. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- P. Lopez.; A. Villanueva.; J. Llovet. Systematic review: evidence-based management of hepatocellular carcinoma–an updated analysis of randomized controlled trials. Aliment Pharm Ther 2006, 23, 1535–1547. [CrossRef]

- H.T. Cohen.; F.J. McGovern. Renal-cell carcinoma. New Engl J Med 2005, 353, 2477–2490. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- B.I.Rini.; S.C. Campbell.; B. Escudier. Renal cell carcinoma. The Lancet 2009, 373, 1119–1132.

- J.M. Hollingsworth. Rising incidence of small renal masses: a need to reassess treatment effect. J Natl Cancer I 2006, 98, 1331–1334. [CrossRef]

- J.M. Hollingsworth, Five-year survival after surgical treatment for kidney cancer: a population-based competing risk analysis. Cancer 2007, 109, 1763–1768. [CrossRef]

- B.A.G., de Melo.; F.L. Motta.; M.H.A. Santana. The interactions between humic acids and Pluronic F127 produce nanoparticles useful for pharmaceutical applications. J Nanopart Res. 2015, 17, 1–11.

- B.A.G., de Melo.; F.L. Motta.; M.H.A. Santana. The interactions between humic acids and Pluronic F127 produce nanoparticles useful for pharmaceutical applications. J Nanopart Res 2015, 17, 400. [CrossRef]

- J.U. Menon. Effects of surfactants on the properties of PLGA nanoparticles. J Biomed Mater Res. Part A 2012, 100, 1998–2005.

- J.K. Jackson.Neutrophil activation by plasma opsonized polymeric microspheres: inhibitory effect of Pluronic F127. Biomaterials 2000, 21, 1483–1491. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- L. LiuSorafenib blocks the RAF/MEK/ERK pathway, inhibits tumor angiogenesis, and induces tumor cell apoptosis in hepatocellular carcinoma model PLC/PRF/5. Cancer Res 2006, 66, 11851–11858. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- X. Wang. Bioavailability and pharmacokinetics of sorafenib suspension, nanoparticles and nanomatrix for oral administration to rat. Intern J Pharm 2011, 419, 339–346. [CrossRef]

- T.Y. Lim.; C.K. Poh.; W. Wang. Poly (lactic-co-glycolic acid) as a controlled release delivery device. J Mater Sci. 2009, 20, 1669–1675.

- J.K. Park. Guided bone regeneration by poly (lactic-co-glycolic acid) grafted hyaluronic acid bi-layer films for periodontal barrier applications. Acta Biomat. 2009, 5, 3394–3403. [CrossRef]

- N. Vij. Development of PEGylated PLGA nanoparticle for controlled and sustained drug delivery in cystic fibrosis. J Nanobiotech 2010, 8, 1.

- N. Csaba.; A. Sanchez.; M.J. Alonso. PLGA: poloxamer and PLGA: poloxamine blend nanostructures as carriers for nasal gene delivery. J Controlled Release 2006, 113, 164–172. [CrossRef]

- N. Nafee. Relevance of the colloidal stability of chitosan/PLGA nanoparticles on their cytotoxicity profile. Int J Pharm 2009, 381, 130–139. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- D. Shenoy. Poly (ethylene oxide)-modified poly (β-amino ester) nanoparticles as a pH-sensitive system for tumor-targeted delivery of hydrophobic drugs. 1. In vitro evaluations. Mol Pharm 2005, 2, 357–366. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- P. Couvreur. Tissue distribution of antitumor drugs associated with polyalkylcyanoacrylate nanoparticles. J Pharm Sci 1980, 69, 199–202. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rolland. Clinical pharmacokinetics of doxorubicin in hepatoma patients after a single intravenous injection of free or nanoparticle-bound anthracycline. Int J Pharm 1989, 54, 113–121. [CrossRef]

- J.C.Leroux. Biodegradable nanoparticles—from sustained release formulations to improved site specific drug delivery. J Control Release 1996, 39, 339. [CrossRef]

- W.L. Monsky. Augmentation of transvascular transport of macromolecules and nanoparticles in tumors using vascular endothelial growth factor. Cancer Res 1999, 59, 4129–4135.

- S. Bennis. Enhanced cytotoxicity of doxorubicin encapsulated in polyisohexylcyanoacrylate nanospheres against multidrug-resistant tumour cells in culture. Eur J Cancer 1994, 30, 89–93. [CrossRef]

- A.J.J. Wood.; E.K. Rowinsky.; R.C. Donehower. Paclitaxel (taxol). New Engl J Med. 1995, 332, 1004–1014.

- A. Seelig. A general pattern for substrate recognition by P-glycoprotein. Eur J Biochem 2001, 251, 252–261.

- G. Gyulai. Preparation and characterization of cationic Pluronic for surface modification and functionalization of polymeric drug delivery nanoparticles. Express Polym Lett 2016, 10, 216–226. [CrossRef]

- C. Detroja.; S. Chavhan.; K. Sawant. Enhanced antihypertensive activity of candesartan cilexetil nanosuspension: formulation, characterization and pharmacodynamic study. Sci. Pharm. 2011, 79, 635. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- H. Ali. Budesonide Loaded PLGA Nanoparticles for Targeting the Inflamed Intestinal Mucosa—Pharmaceutical Characterization and Fluorescence Imaging. Pharm. Resear. 2016, 33, 1085–1092. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- S.X. Yin. Bioavailability enhancement of a COX-2 inhibitor, BMS-347070, from a nanocrystalline dispersion prepared by spray-drying. J Pharm Sci, 2005, 94, 1598–1607. [CrossRef]

- E. Blanco.; H. Shen, M. Ferrari, Principles of nanoparticle design for overcoming biological barriers to drug delivery. Nat. Biotech. 2015, 33, 941–951. [CrossRef]

- N.P.Truong. The importance of nanoparticle shape in cancer drug delivery. Expert Opin Drug Del 2015, 12, 129–142. [CrossRef]

- S. Dash. Kinetic modeling on drug release from controlled drug delivery systems. Acta Pol Pharm 2010, 67, 217–223.

- P. Costa.; J.M.S. Lobo. Modeling and comparison of dissolution profiles. Eu J Pharmac. Scienc 2001, 13, 123–133. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- S. Stolnik. Polylactide-poly (ethylene glycol) micellar-like particles as potential drug carriers: production, colloidal properties and biological performance. J.Drug Targ 2001, 9, 361–378. [CrossRef]

- G. Kaul.; M. Amiji. Biodistribution and targeting potential of poly (ethylene glycol)-modified gelatin nanoparticles in subcutaneous murine tumor model. J.Drug Targ. 2004, 12, 585–591. [CrossRef]

- M. Snehalatha. Etoposide loaded PLGA and PCL nanoparticles II: biodistribution and pharmacokinetics after radiolabeling with Tc-99m. Drug deliv. 2008, 15, 277–287. [CrossRef]

- C. P. Hollis. Biodistribution and bioimaging studies of hybrid paclitaxel nanocrystals: lessons learned of the EPR effect and image-guided drug delivery. J Control Release 2013, 172, 12–21. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- N. Sharma.; P. Madan.; S. Lin. Effect of process and formulation variables on the preparation of parenteral paclitaxel-loaded biodegradable polymeric nanoparticles: A co-surfactant study. Asia. J Pharm Sci 2016, 11, 404–416.

- E. Vega. PLGA nanospheres for the ocular delivery of flurbiprofen: drug release and interactions. J Pharm Sci 2008, 97, 5306–5317. [CrossRef]

- É. Kiss. Tuneable surface modification of PLGA nanoparticles carrying new antitubercular drug candidate. Colloids and Surfaces A: Physicoch. Eng. Aspec. 2014, 458, 178–186. [CrossRef]

- J.M. Morachis.; E.A. Mahmoud.; A. Almutairi. Physical and chemical strategies for therapeutic delivery by using polymeric nanoparticles. Pharmaco. reviews 2012, 64, 505–519. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Z. Yang. Shape-memory nanoparticles from inherently non-spherical polymer colloids. Nature materials 2005, 4, 486–490. [CrossRef]

- Y Liu. The shape of things to come: importance of design in nanotechnology for drug delivery. Therapeutic delivery 2012, 3, 181–194. [CrossRef]

- M. Halayqa.; U. Domańska. PLGA biodegradable nanoparticles containing perphenazine or chlorpromazine hydrochloride: effect of formulation and release. Int J Mol Sci 2014, 15, 23909–23923. [CrossRef]

- Corrigan.; X. Li. Quantifying drug release from PLGA nanoparticulates. Eu J Pharmac. Scienc 2009, 37, 477–485. [CrossRef]

- H. Redhead.; S. Davis.; L. Illum. Drug delivery in poly (lactide-co-glycolide) nanoparticles surface modified with poloxamer 407 and poloxamine 908: in vitro characterisation and in vivo evaluation. J Control Release 2001, 70, 353–363. [CrossRef]

- A. Yassin. Optimization of 5-fluorouracil solid-lipid nanoparticles: a preliminary study to treat colon cancer. Int J Med Sci 2010, 7, 398–408.

- B. de Carvalho Patricio.; M. de Souza Albernaz.; R. Santos-Oliveira. Development of nanoradiopharmaceuticals by labeling polymer nanoparticles with tc-99m. World J Nucl. Medic. 2013, 12, 24. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).