Submitted:

15 August 2023

Posted:

16 August 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

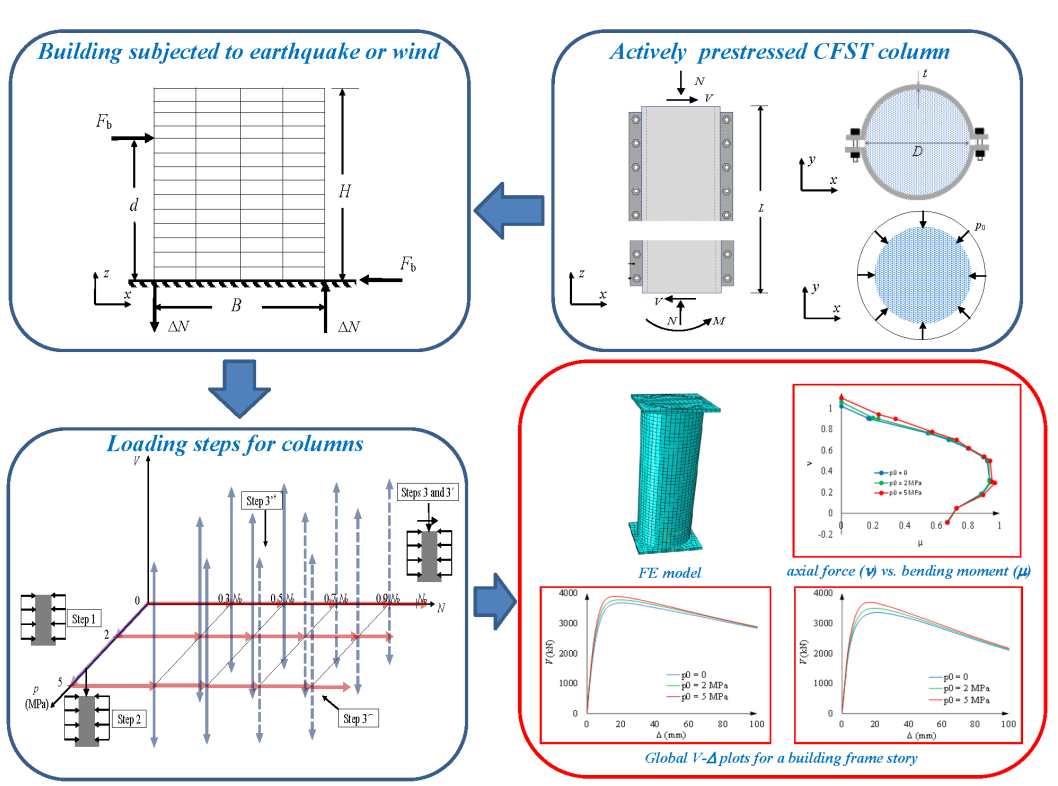

1. Introduction

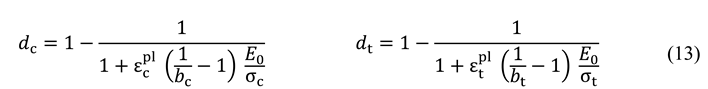

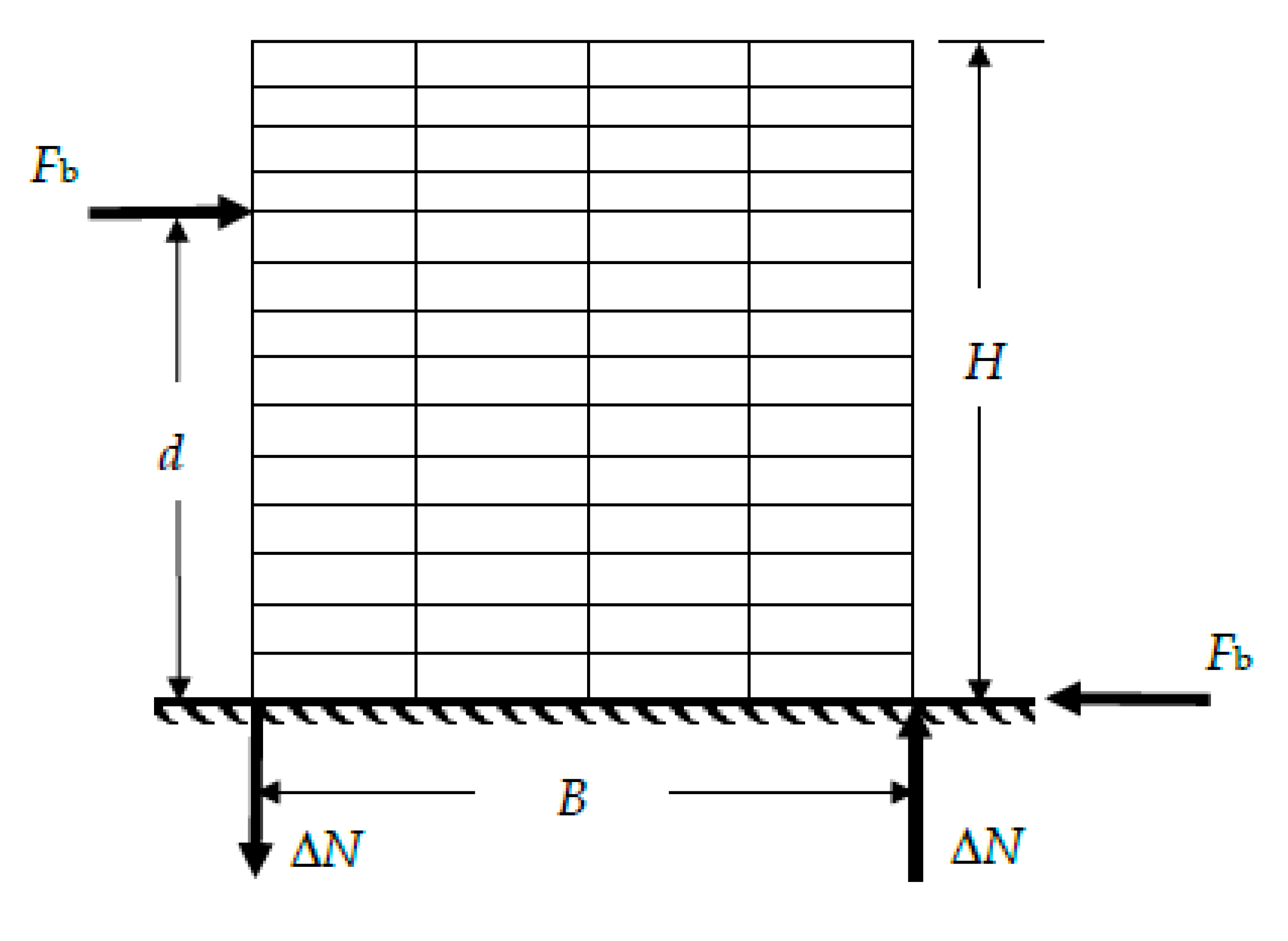

2. Analyzed column segments

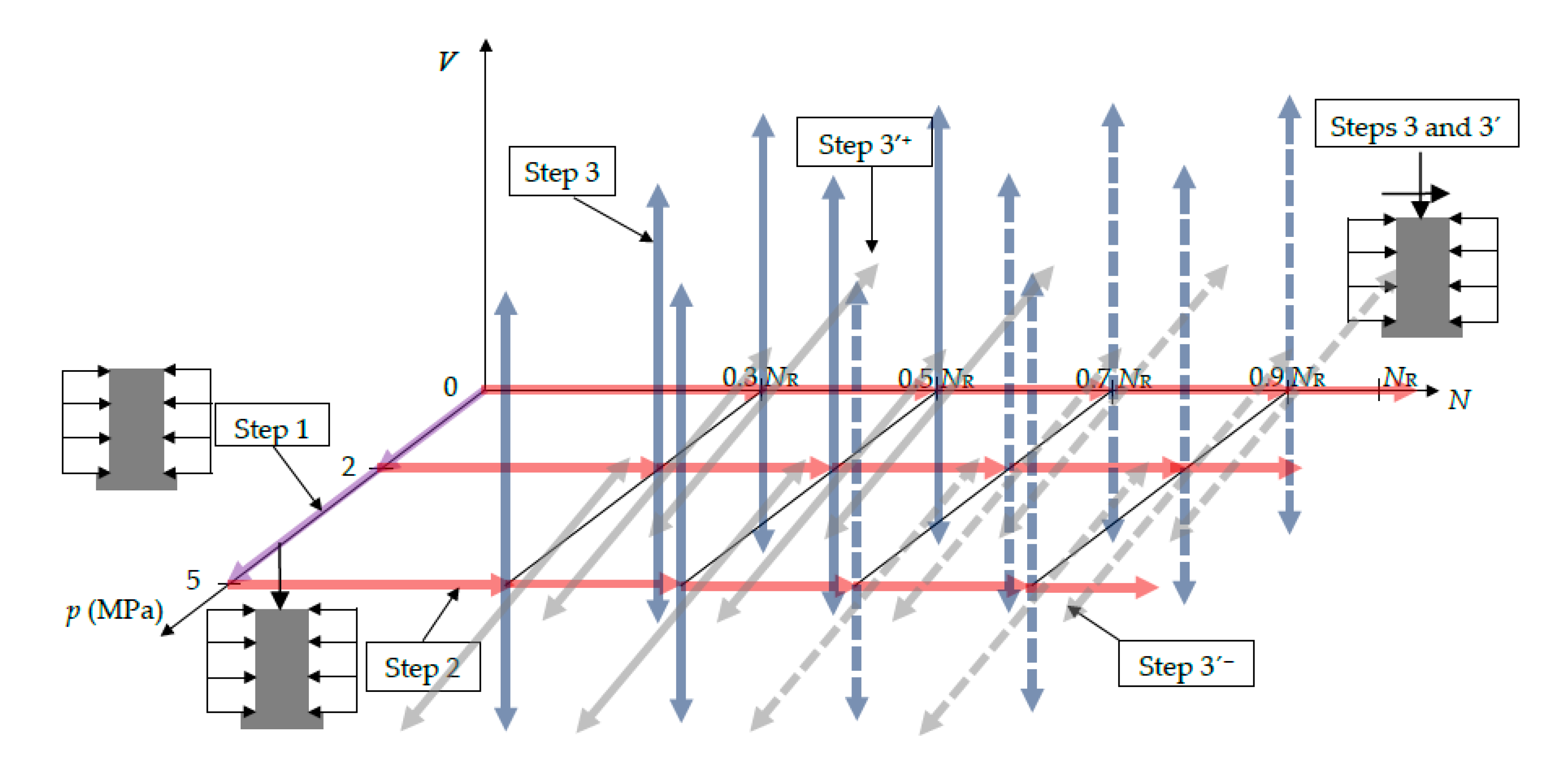

3. Loading steps of the column segments

- Internal columns. Step 1 corresponds to p0, and steps 2 and 3 to N and V, respectively.

- External columns. Steps 1 and 2 are the same than in the internal columns; regarding the last loading step, it is known as 3´, and involves variation of both N and V (these variations are represented by ΔN and V, respectively).

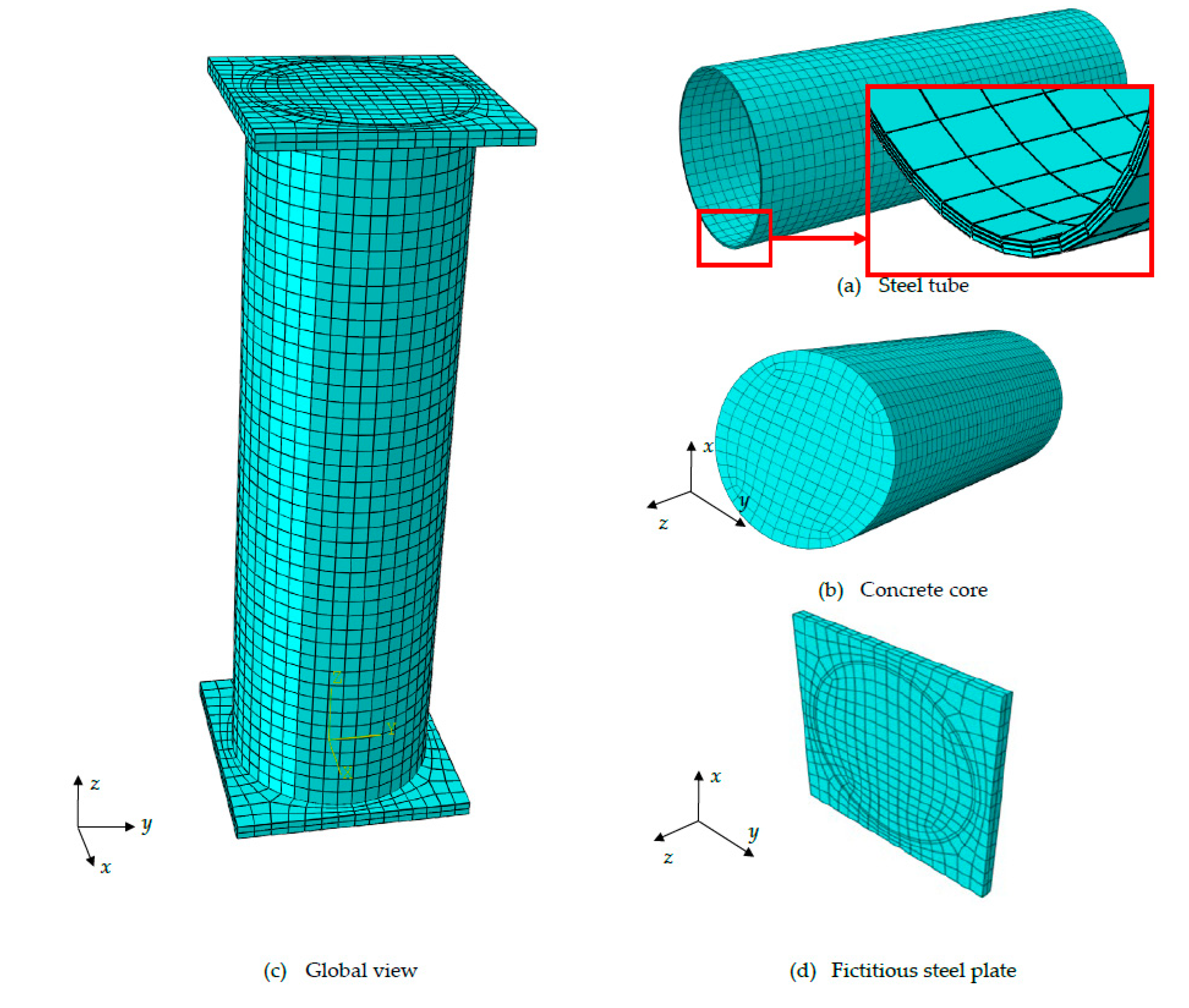

4. Numerical model of the column segments

4.1. Finite element mesh and boundary conditions

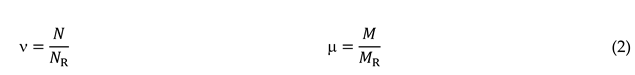

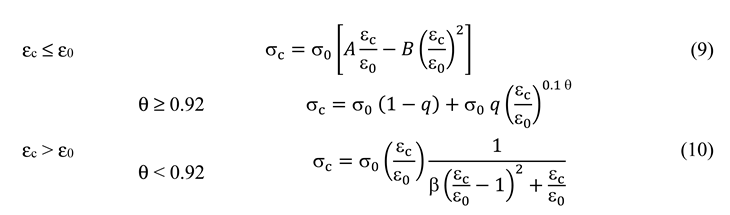

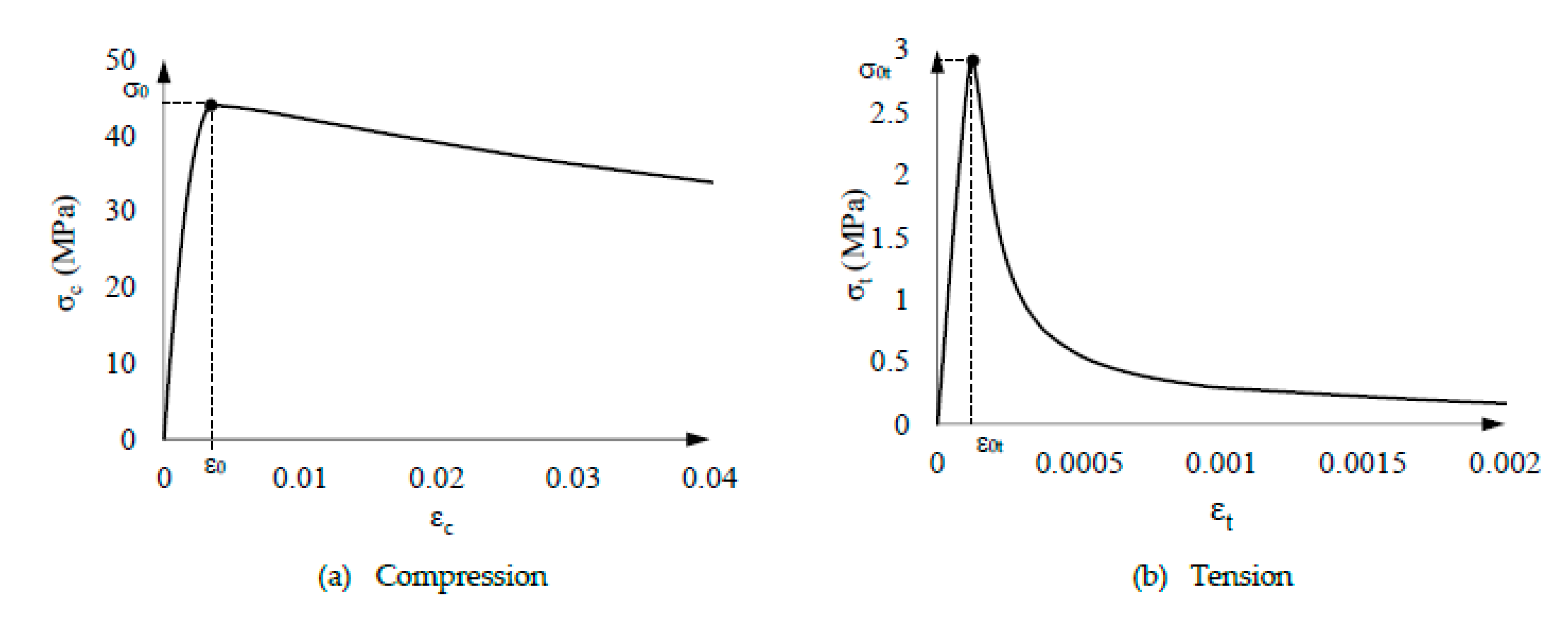

4.2. Concrete constitutive law

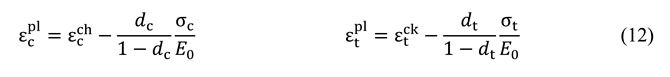

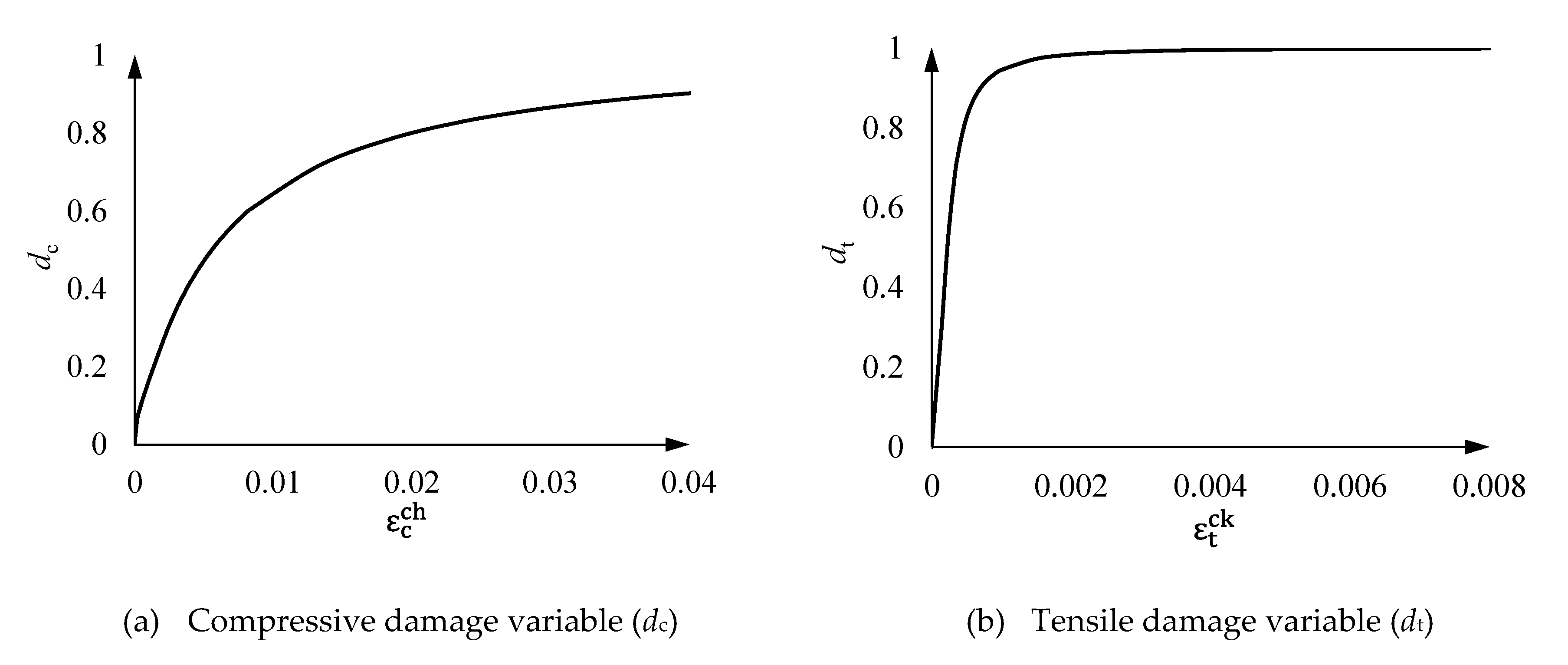

4.3. Concrete damage plasticity model

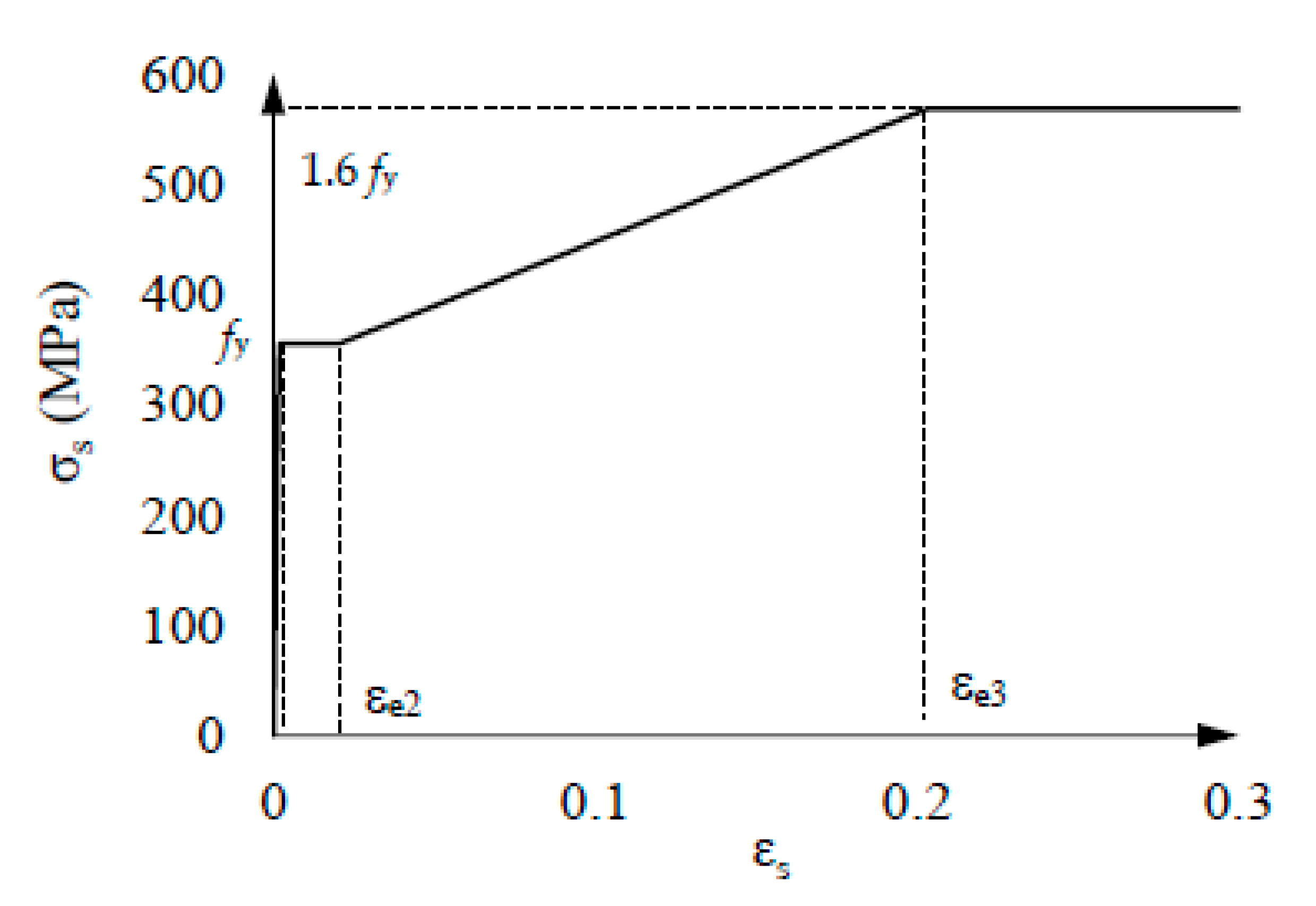

4.4. Steel constitutive law

4.5. Concrete-steel contact

4.6. Loads application

4.7. Numerical calculation

5. Numerical results of the column segments analyses

5.1. Loading step 1

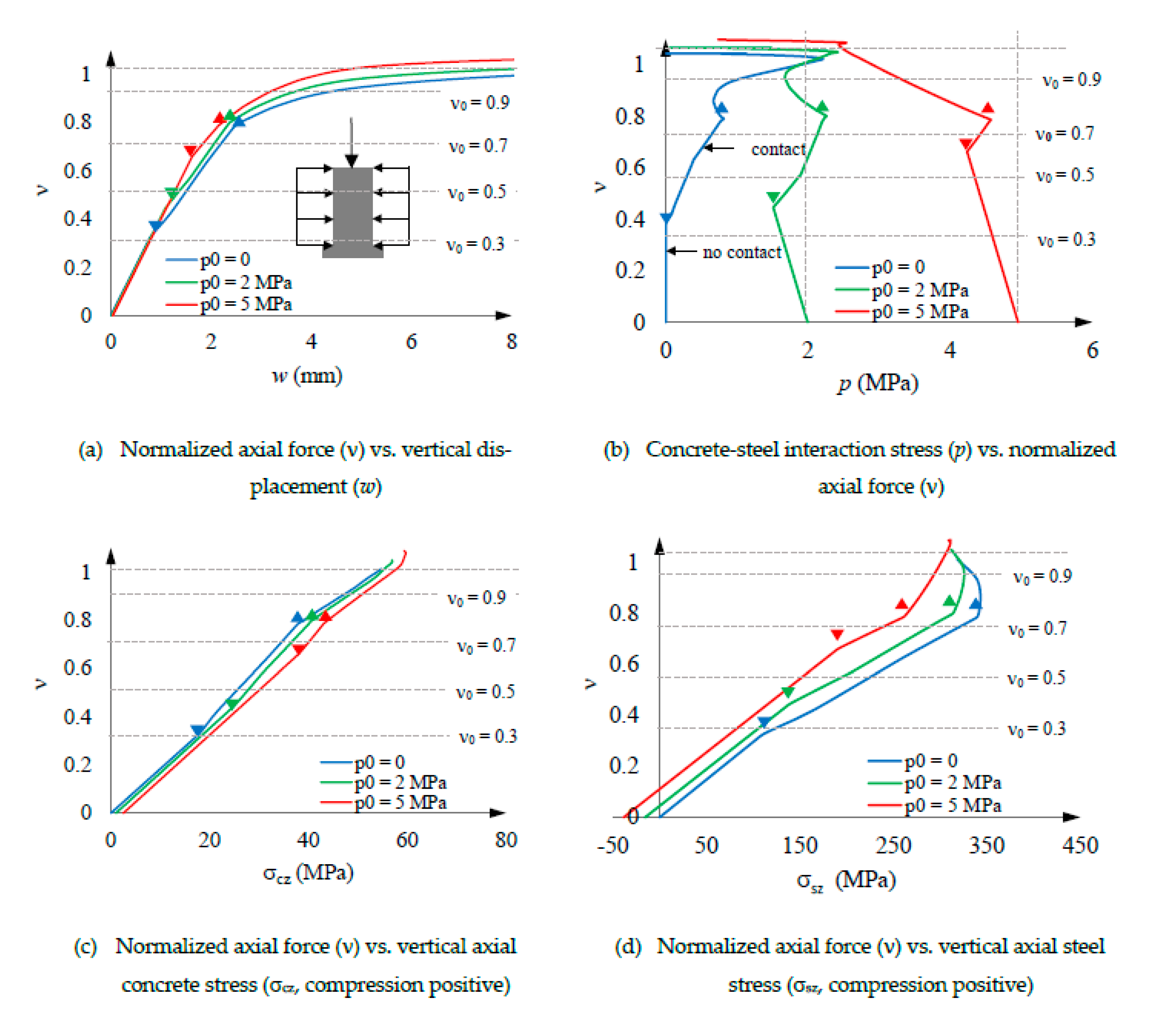

5.2. Loading step 2

- Initial segments. The initial segments exhibit different characteristics in the non-prestressed and prestressed cases. In the non-prestressed case (p0 = 0), initially (that is, for small values of ν), the steel tube separates from the concrete core (i.e., εct < εst), and p remains being zero (Figure 9.b) because it cannot be negative (subsection 4.5); then, slightly before ν reaches 0.4, concrete and steel resume contact (εct = εst) and p begins to take positive values. In the prestressed cases (p0 = 2 and 5 MPa), the situation is different, as the initial value of the interaction contact stress (p) is nonzero and, thus, can decrease from the very beginning without taking negative values. These circumstances can be explained (both for the non-prestressed and prestressed cases) because the initial steel Poisson ratio is higher than that of concrete and, thus, the numerator in equation (16) is positive. For the later segments (intermediate and final) equation (16) becomes less applicable, as the behavior is nonlinear.

- Intermediate segments. Figure 9 shows three different tendencies in these segments: the linear behavior terminates (indicated by the points ▼), p increases (Figure 9.b), and the vertical axial stress is progressively transferred from concrete to steel (Figure 9.c and Figure 9.d). The first and last trends can be explained by the onset of a relevant concrete nonlinear behavior (Figure 5.a), and the growth of p is due to an increase of the concrete Poisson ratio. Regarding this last issue, concrete crushing generates significant volume expansion, resulting in an unusually high apparent Poisson ratio νc (greatly exceeding 0.5).

- Final segments. In Figure 9, the end of the intermediate segments (indicated by the points ▲) correspond to high values of ν (close to 0.8), where the steel stiffness decreases drastically (Figure 7) and, hence, most of the load is taken by the concrete (Figure 9.c and Figure 9.d). Unsurprisingly, this steel yielding causes higher axial flexibility (Figure 9.a) and less confinement (Figure 9.b).

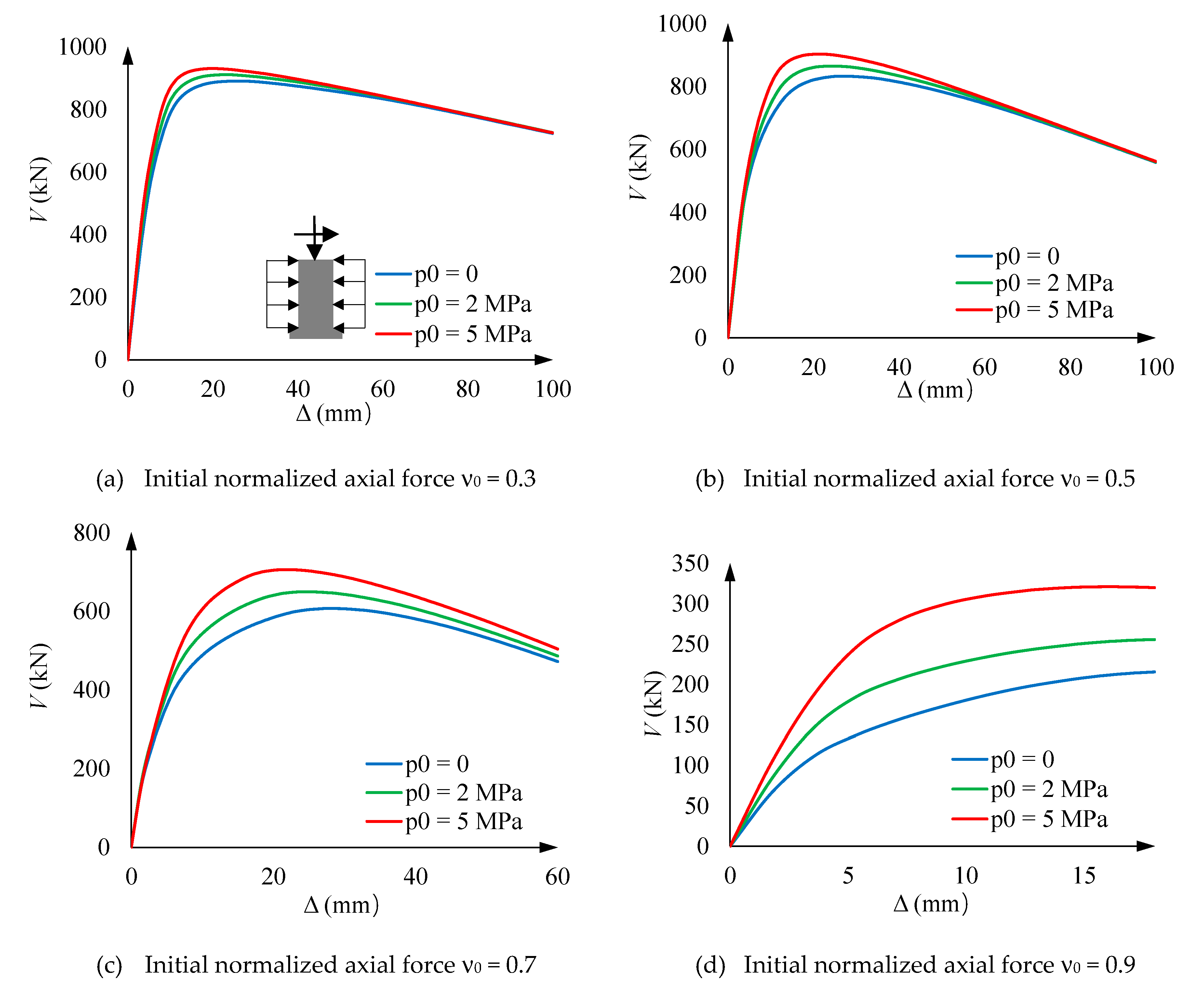

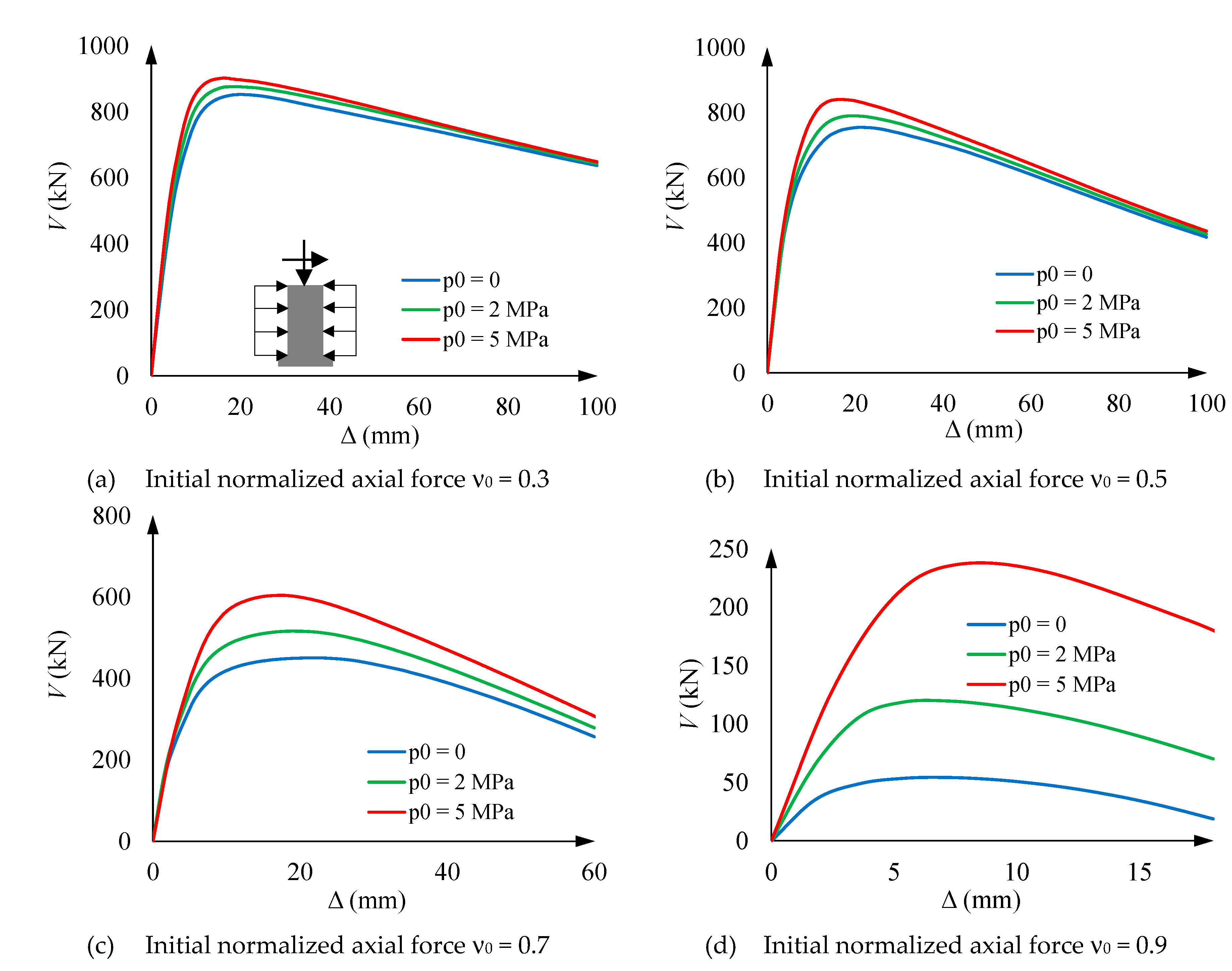

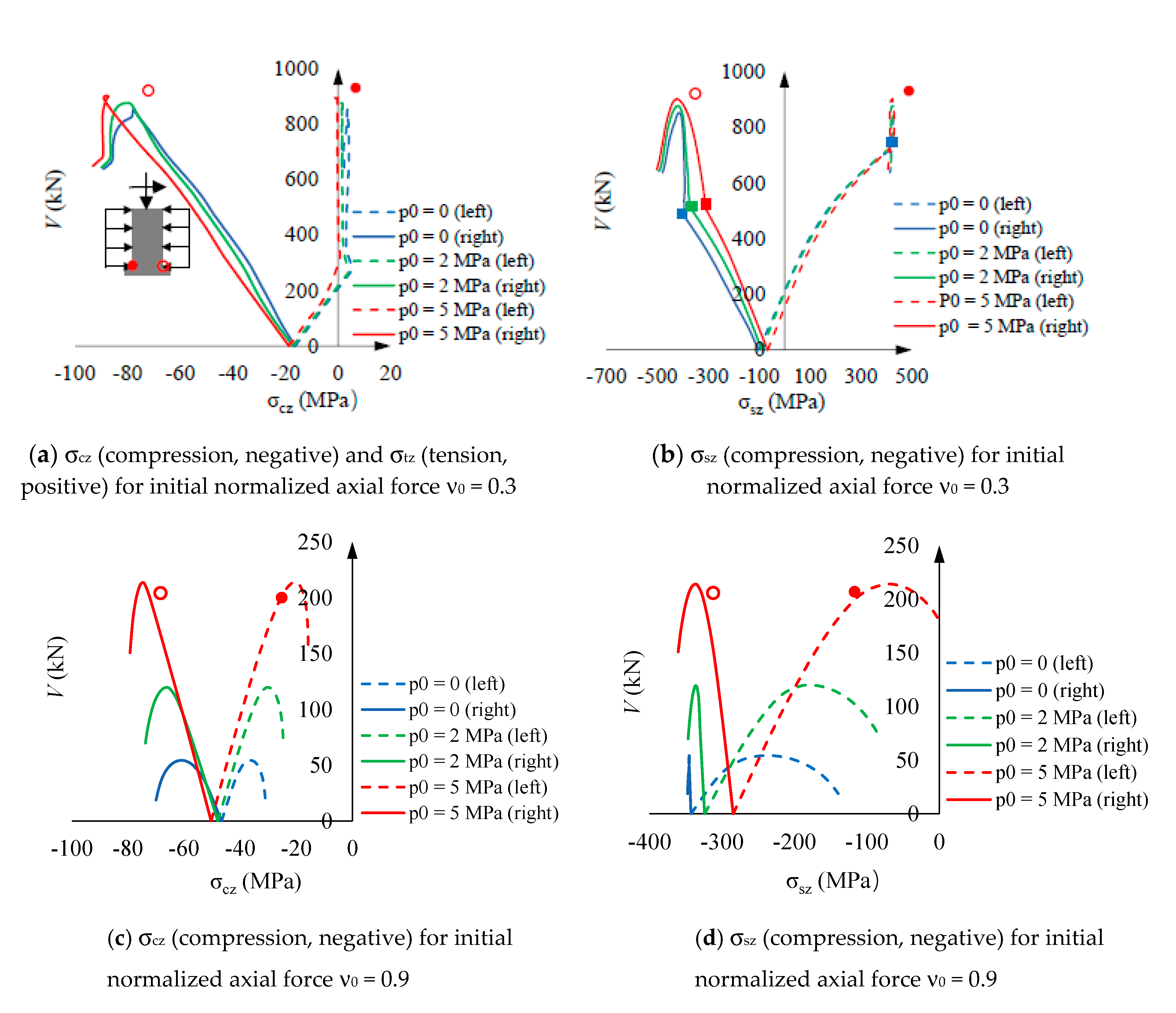

5.3. Loading step 3

- Vertical stress of concrete and steel for ν0 = 0.3. The behavior described by Figure 12.a and Figure 12.b agrees with Figure 11.a. More specifically,Figure 12.a and Figure 12.b show that the initial behavior is linear, and then, for approximately V = 300 kN, the tensile concrete stress (σtz) reaches its maximum capacity; this stress is progressively taken by steel, thus generating an increase of the concrete compressive stress is also generated. Figure 12.a shows that the concrete compressive stress reaches extraordinarily high values, clearly above σ0 (Figure 5); this circumstance highlights the importance of the steel confinement, being this effect rather independent of the hoop prestress. In Figure 12.b, points marked with ■ correspond to the steel yielding.

- Vertical stress of concrete and steel for ν0 = 0.9. Figure 12.c and Figure 12.d provide rather similar remarks than Figure 12.a and Figure 12.b (for ν0 = 0.3); perhaps the main differences lie in the fact that concrete is always under compression, and the steel branches for points ● and are asymmetric due to early steel yielding at point .

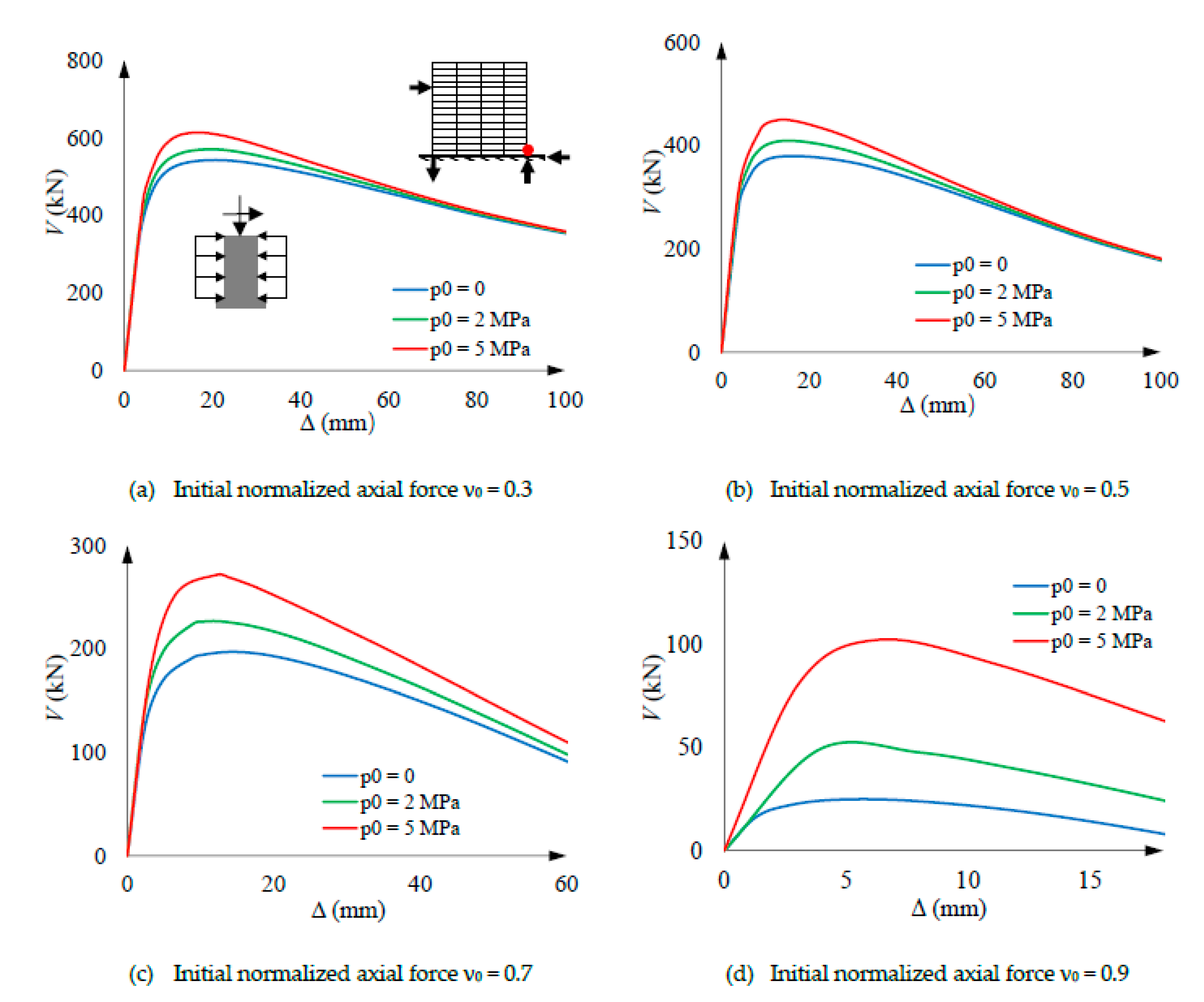

5.4. Loading step 3’

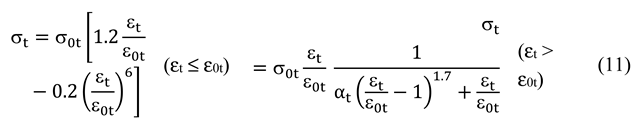

6. Column section capacity

7. Global structural behavior of the building

7.1. Story vertical behavior

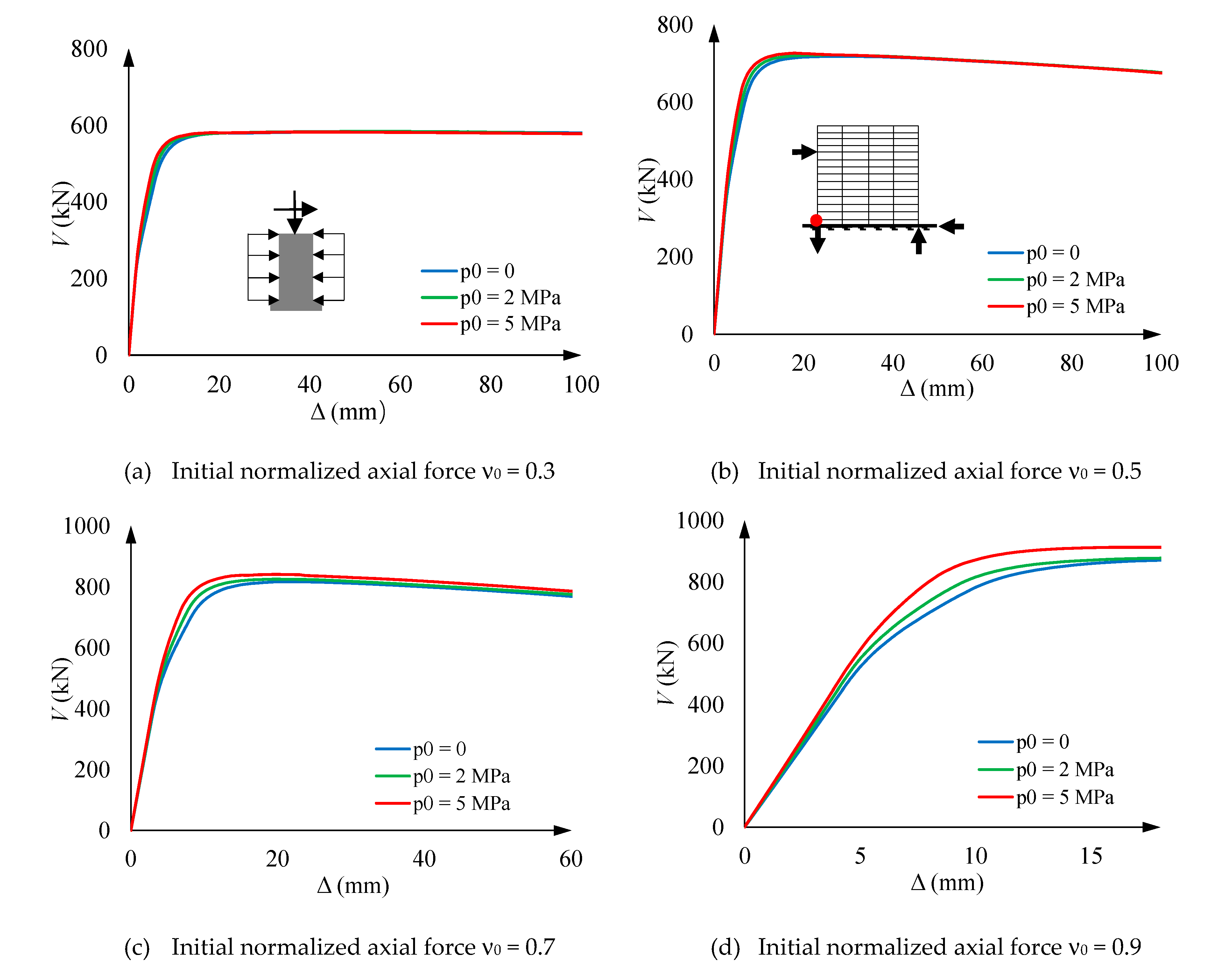

7.2. Story lateral behavior

- Wind. The horizontal shear force on a bottom story of a 2-D frame ranges approximately between 180 kN (12 stories, covered situation, span length 5 m, story height 3 m) and 1125 kN (25-story building, exposed situation, span length 8 m, story height 4.5 m).

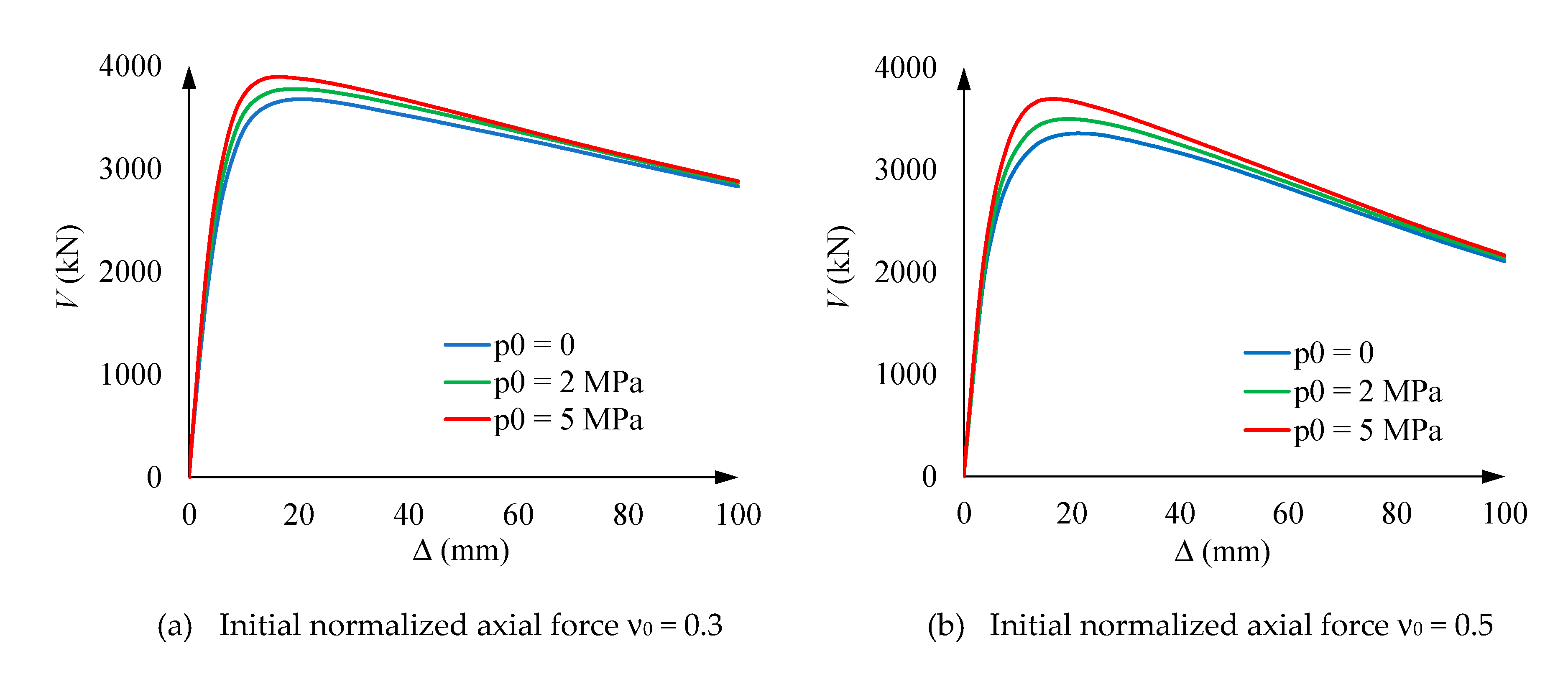

- Earthquakes. The equivalent static lateral force method shows that, for typical columns of mid-rise buildings (building fundamental period lying in the design spectrum plateau), the base shear force (V) ranges approximately between 0.4 ag W (rock-like soil, ordinary use, high response modification factor) and ag W (soft soil, essential use, moderate response modification factor), where W is the supported seismic weight (equal to the sum of the demanding axial forces N of each column) and ag is the seismic acceleration (corresponding to rock and 475 years return period) referred to the gravity acceleration (also commonly known as PGA, Peak Ground Acceleration). These considerations show that, for ν0 = 0.3, in a high seismicity area (ag = 0.4 g) the demanding base shear force for a 5-column frame like the one depicted by Figure 2 ranges between 3600 and 9000 kN; in a low seismicity area (ag = 0.1 g), such bounds become 900 and 2250 kN, respectively. Obviously, for ν0 = 0.5, these values must be multiplied by 5 / 3; the ranges are 6000-15000 kN (for ag = 0.4 g) and 1500-3750 kN (for ag = 0.1 g). It should be kept in mind that these lateral forces must be combined with the vertical ones that correspond to the seismic weight.

8. Conclusions

- Vertical loads (axial force). As expected, the strength of CFST columns for vertical centered axial compression is significant (subsection 5.2). The benefit of the active hoop prestress is relevant, although not outstanding; this circumstance can be explained by the tube transverse expansion (due to Poisson effect) that impairs the concrete core confinement (although not cancelling it totally).

- Lateral forces (bending). Also as expected, the bending strength of CFST columns is significant (subsections 5.3 and 5.4). The benefits of the active hoop prestress are smaller than for the axial load; this trend is seemingly due to the lack of sectional global lateral expansion during bending.

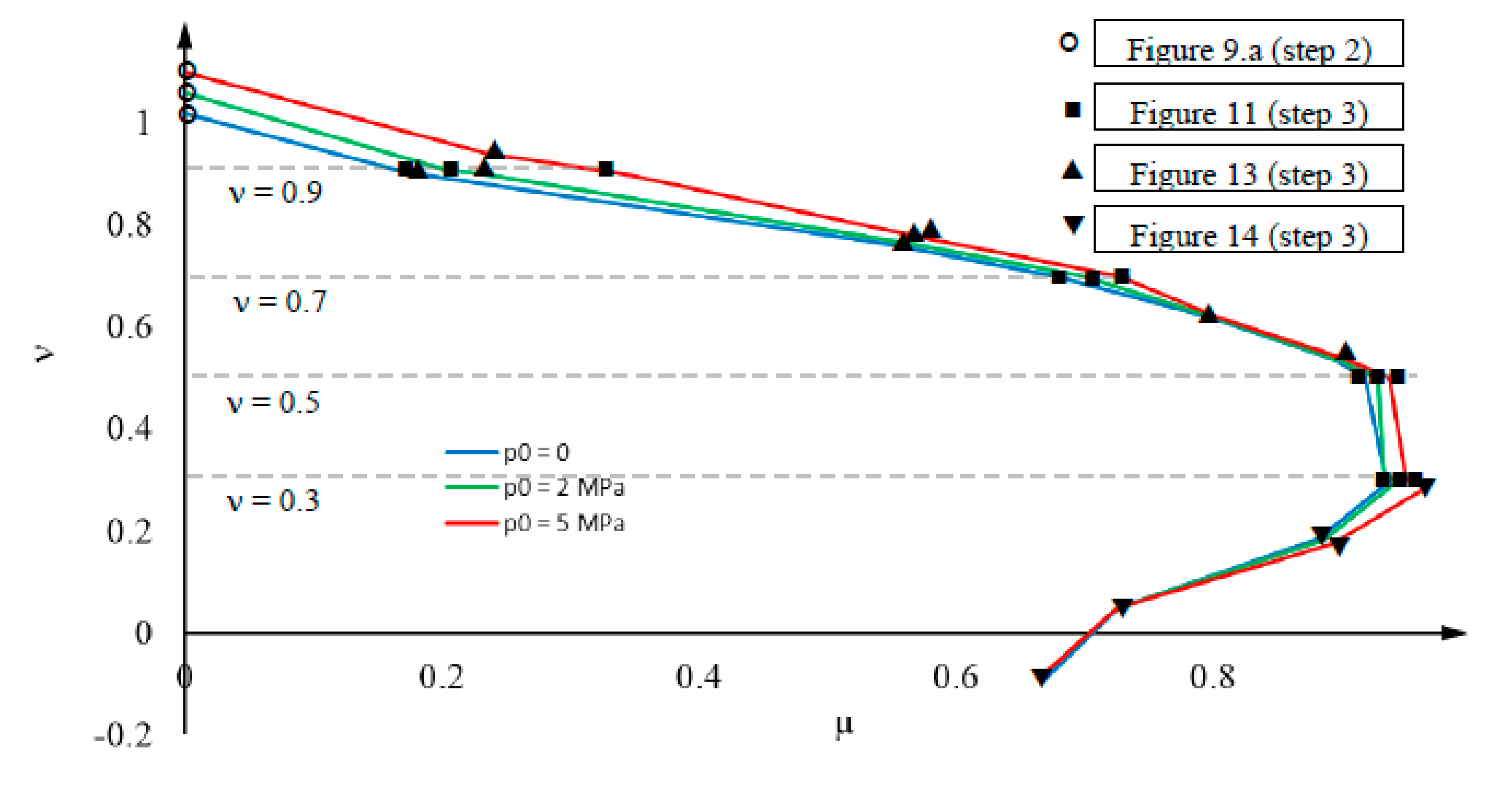

- Axial force-bending moment interaction. The strength for eccentric axial loads is pretty high; for moderate compression, the moment capacity is clearly higher than for pure bending (section 6). The influence of the active transverse prestress is higher for large axial compression; for pure bending and for axial tension, that influence is practically negligible.

- Gravity loads. Given the notable axial capacity of the CFST columns, a proper design can make available a satisfactory vertical strength.

- Lateral forces (wind and seismic). The story shear capacity provided by CFST columns is sufficient for moderate seismic ground motions (approximately, Peak Ground Acceleration 0.2 g). This conclusion refers to a rather high response modification factor; therefore, the columns would be significantly damaged, and, thus, high ductility is required. Regarding this last issue, the displacement ductility is rather satisfactory. Finally, about wind, the story shear strength is largely enough.

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A. List of symbols

References

- Romero, M.L.; Moliner, V.; Espinos, A.; Ibañez, C.; Hospitaler, A. Fire behavior of axially loaded slender high strength concrete-filled tubular columns. J. Constr. Steel Res. 2011, 67, 1953–1965. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, K.; Han, L.-H. Experimental performance of concrete-encased CFST columns subjected to full-range fire including heating and cooling. Eng. Struct. 2018, 165, 331–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Portolés, J.; Romero, M.; Bonet, J.; Filippou, F. Experimental study of high strength concrete-filled circular tubular columns under eccentric loading. J. Constr. Steel Res. 2011, 67, 623–633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hajjar JF, Denavit MD, Perea T, Leon RT. 2012. Seismic design and stability assessment of composite framing systems. 9th International Conference on Urban Earthquake Engineering. Tokyo, Japan.

- Ekmekyapar, Al-Eliwi BJM. 2016. Experimental behavior of circular concrete filled steel tube columns and design specifications. Thin-Walled Structures. 105:220-230.

- Wang, J.; Sun, Q.; Li, J. Experimental study on seismic behavior of high-strength circular concrete-filled thin-walled steel tubular columns. Eng. Struct. 2019, 182, 403–415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tao, Z.; Hasan, M.; Han, D.; Qin, Q.; Ghafar, W.A. Study of the Axial Compressive Behaviour of Cross-Shaped CFST and ST Columns with Inner Changes. Buildings 2023, 13, 423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ouyang, Y.; Kwan, A.; Lo, S.; Ho, J. Finite element analysis of concrete-filled steel tube (CFST) columns with circular sections under eccentric load. Eng. Struct. 2017, 148, 387–398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hajjar JF, Schiller PH. Molodan A. 1998. A distributed plasticity model for concrete-filled steel tube beam-columns with interlayer slip. Engineering Structures. 20(8):663-676.

- Albareda-Valls, A. 2013. Numerical analysis of concrete-filled tubes with stiffening plates under large deformation axial loading. Ph.D. Dissertation, Polytechnic University of Catalonia (UPC), Barcelona.

- Du GF, Bie MX. 2016. Numerical simulation of axial compression mechanical behavior of CFST column with concrete damaged plasticity (in Chinese). Journal of Shenyang Jianzhu University (Natural Science). 32(3):444-451.

- Milan, C.C.; Albareda-Valls, A.; Carreras, J.M. Evaluation of structural performance between active and passive preloading systems in circular concrete-filled steel tubes (CFST). Eng. Struct. 2019, 194, 207–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu X, Yongjiu Q. 2013a. Experiment study of reinforced concrete short column strengthened by circular steel tube under axial loading (in Chinese). Sichuan Building Science. 39(6):96-98.

- Hu X, Yongjiu Q. 2013b. Compressive behavior of reinforced concrete short column strengthened by circular steel tube under axial compressing (in Chinese). Journal of Highway and Transportation Research and Development. 30(6):100-108.

- Hu X. 2015. Research on compressive performance and bearing capacity of RC short columns strengthened with circular steel jacketing (in Chinese). PhD Thesis. Southwest Jiaotong University.

- Swami, G.; Thai, H.-T.; Liu, X. Structural robustness of composite modular buildings: The roles of CFST columns and inter-module connections. Structures 2023, 48, 1491–1504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, SH. 2003. Modern steel confined concrete structures (in Chinese). China Communication Press.

- CECS 28-90. 1992. Specification for design and construction of concrete-filled steel tubular structures (in Chinese). China Association for Engineering Construction Standardization.

- Smith, M. 2009. ABAQUS/Standard User's Manual, Version 6.9. Providence, RI: Dassault Systèmes Simulia Corporation.

- Sarir, P.; Jiang, H.; Asteris, P.G.; Formisano, A.; Armaghani, D.J. Iterative Finite Element Analysis of Concrete-Filled Steel Tube Columns Subjected to Axial Compression. Buildings 2022, 12, 2071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Susantha, K.; Ge, H.; Usami, T. Uniaxial stress–strain relationship of concrete confined by various shaped steel tubes. Eng. Struct. 2001, 23, 1331–1347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han LH, Feng J. 1995. The constitutive model of concrete and its application in numerical analysis of CFST (in Chinese). Journal of Harbin University of Architecture and Engineering. 28(5):26-32.

- GB 50010. 2010. Code for Design of Concrete Structures (in Chinese). China.

- Lubliner J, Oliver J, Oller S, Oñate E. 1989. A plastic-damage model for concrete. International Journal on Solids and Structures. 25(3):299-326.

- Hibbitt D, Karlson B, Sorensen P. 2003. ABAQUS Version 6.4: Theory manual, users’ manual, verification manual and example problems manual. Hibbitt, Karlson and Sorensen Inc.

- Long, X. 2014. Experimental and numerical investigations on concrete-filled steel tubular stub columns under axial compression (in Chinese). Master Degree Thesis. Hunan University.

- Lee, J.; Fenves, G.L. Plastic-Damage Model for Cyclic Loading of Concrete Structures. J. Eng. Mech. 1998, 124, 892–900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alfarah, B.; López-Almansa, F.; Oller, S. New methodology for calculating damage variables evolution in Plastic Damage Model for RC structures. Eng. Struct. 2017, 132, 70–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang J, Wang QY, Hu S, Wang C. 2008. Parameters verification of concrete damaged plastic model of ABAQUS (in Chinese). Building Structure. 38(8):127-130.

- Srinivasan, C.N.; Schneider, S.P. Axially Loaded Concrete-Filled Steel Tubes. J. Struct. Eng. 1999, 125, 1202–1206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, H.-T.; Huang, C.-S.; Wu, M.-H.; Wu, Y.-M. Nonlinear Analysis of Axially Loaded Concrete-Filled Tube Columns with Confinement Effect. J. Struct. Eng. 2003, 129, 1322–1329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhong, ST. 2006. Unified theory for CFST (in Chinese). Tsinghua University Press.

| Core diameter D (mm) | Tube thickness t (mm) | Segment length L (m) | Concrete compressive strength fck (MPa) | Steel yield point fy (MPa) | Active hoop prestress p0 (MPa) | Initial normalized axial compression ν0 |

| 500 | 8 | 1.5 | 30 | 355 | 0 / 2 / 5 | 0.3 / 0.5 / 0.7 / 0.9 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).