Submitted:

15 August 2023

Posted:

16 August 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Material and methods

2.1. Data analysis

2.2. Reference procedure

2.3. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

4. Discussion

References

- Bertolotto, M.; Campo, I.; Pavan, N.; Buoite Stella, A.; Cantisani, V.; Drudi, F.M.; et al. What Is the Malignant Potential of Small (<2 cm), Nonpalpable Testicular Incidentalomas in Adults? A Systematic Review. Eur Urol Focus.

- Nicol, D.; Berney, D.; Algaba, F.; Boormans, J.L.; di Nardo, D.; Fankhauser, C.D.; et al. EAU Guidelines on Testicular Cancer. Arnhem, The Netherlands: EAU Guidelines Office; 2023.

- Bieniek, J.M.; Juvet, T.; Margolis, M.; Grober, E.D.; Lo, K.C.; Jarvi, K.A. Prevalence and Management of Incidental Small Testicular Masses Discovered on Ultrasonographic Evaluation of Male Infertility. J Urol. 2018, 199, 481–486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Toren, P.J.; Roberts, M.; Lecker, I.; Grober, E.D.; Jarvi, K.; Lo, K.C. Small incidentally discovered testicular masses in infertile men--is active surveillance the new standard of care? J Urol. 2010, 183, 1373–1377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mazrani, W.; O’Malley, M.E.; Chung, P.W.; Warde, P.; Vesprini, D.; Panzarella, T. Lymph node growth rate in testicular germ cell tumours: implications for computed tomography surveillance frequency. Clin Oncol (R Coll Radiol). 2011, 23, 333–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Connolly, S.S.; D’Arcy, F.T.; Gough, N.; McCarthy, P.; Bredin, H.C.; Corcoran, M.O. Carefully selected intratesticular lesions can be safely managed with serial ultrasonography. BJU Int. 2006, 98, 1005–1007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rocher, L.; Ramchandani, P.; Belfield, J.; Bertolotto, M.; Derchi, L.E.; Correas, J.M.; et al. Incidentally detected non-palpable testicular tumours in adults at scrotal ultrasound: impact of radiological findings on management Radiologic review and recommendations of the ESUR scrotal imaging subcommittee. Eur Radiol. 2016, 26, 2268–2278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mehrara, E.; Forssell-Aronsson, E.; Ahlman, H.; Bernhardt, P. Specific growth rate versus doubling time for quantitative characterization of tumor growth rate. Cancer Res. 2007, 67, 3970–3975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Larici, A.R.; Farchione, A.; Franchi, P.; Ciliberto, M.; Cicchetti, G.; Calandriello, L.; et al. Lung nodules: size still matters. Eur Respir Rev. 2017, 26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scandura, G.; Verrill, C.; Protheroe, A.; Joseph, J.; Ansell, W.; Sahdev, A.; et al. Incidentally detected testicular lesions <10 mm in diameter: can orchidectomy be avoided? BJU Int. 2018, 121, 575–582. [Google Scholar]

- Huddart RA, Norman A, Moynihan C, Horwich A, Parker C, Nicholls E, et al. Fertility, gonadal and sexual function in survivors of testicular cancer. Br J Cancer. 2005, 93, 200–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tuinman, M.A.; Hoekstra, H.J.; Fleer, J.; Sleijfer, D.T.; Hoekstra-Weebers, J.E. Self-esteem, social support, and mental health in survivors of testicular cancer: a comparison based on relationship status. Urol Oncol. 2006, 24, 279–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsili, A.C.; Bertolotto, M.; Rocher, L.; Turgut, A.T.; Dogra, V.; Secil, M.; et al. Sonographically indeterminate scrotal masses: how MRI helps in characterization. Diagn Interv Radiol. 2018, 24, 225–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Konstantatou, E.; Fang, C.; Romanos, O.; Derchi, L.E.; Bertolotto, M.; Valentino, M.; et al. Evaluation of Intratesticular Lesions With Strain Elastography Using Strain Ratio and Color Map Visual Grading: Differentiation of Neoplastic and Nonneoplastic Lesions. J Ultrasound Med. 2019, 38, 223–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cantisani, V.; Di Leo, N.; Bertolotto, M.; Fresilli, D.; Granata, A.; Polti, G.; et al. Role of multiparametric ultrasound in testicular focal lesions and diffuse pathology evaluation, with particular regard to elastography: Review of literature. Andrology. 2021, 9, 1356–1368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bertolotto, M.; Muca, M.; Curro, F.; Bucci, S.; Rocher, L.; Cova, M.A. Multiparametric US for scrotal diseases. Abdom Radiol (NY). 2018, 43, 899–917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Drudi, F.M.; Valentino, M.; Bertolotto, M.; Malpassini, F.; Maghella, F.; Cantisani, V.; et al. CEUS Time Intensity Curves in the Differentiation Between Leydig Cell Carcinoma and Seminoma: A Multicenter Study. Ultraschall Med. 2016, 37, 201–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lewicki, A.; Freeman, S.; Jedrzejczyk, M.; Dobruch, J.; Dong, Y.; Bertolotto, M.; et al. Incidental Findings and How to Manage Them: Testis- A WFUMB Position Paper. Ultrasound Med Biol. 2021, 47, 2787–2802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zengerling, F.; Kunath, F.; Jensen, K.; Ruf, C.; Schmidt, S.; Spek, A. Prognostic factors for tumor recurrence in patients with clinical stage I seminoma undergoing surveillance-A systematic review. Urol Oncol. 2018, 36, 448–458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chung, P.; Daugaard, G.; Tyldesley, S.; Atenafu, E.G.; Panzarella, T.; Kollmannsberger, C.; et al. Evaluation of a prognostic model for risk of relapse in stage I seminoma surveillance. Cancer Med. 2015, 4, 155–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moore, N.; Laurila, T.; Jarrard, D.F. Sonographically documented stable seminoma: a case report. Int Urol Nephrol. 2007, 39, 1163–1165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giannarini, G.; Dieckmann, K.P.; Albers, P.; Heidenreich, A.; Pizzocaro, G. Organ-sparing surgery for adult testicular tumours: a systematic review of the literature. Eur Urol. 2010, 57, 780–790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reeves, A.P.; Chan, A.B.; Yankelevitz, D.F.; Henschke, C.I.; Kressler, B.; Kostis, W.J. On measuring the change in size of pulmonary nodules. IEEE Trans Med Imaging. 2006, 25, 435–450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mehrara, E.; Forssell-Aronsson, E.; Ahlman, H.; Bernhardt, P. Quantitative analysis of tumor growth rate and changes in tumor marker level: specific growth rate versus doubling time. Acta Oncol. 2009, 48, 591–597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rajpert-De Meyts, E.; McGlynn, K.A.; Okamoto, K.; Jewett, M.A.; Bokemeyer, C. Testicular germ cell tumours. Lancet. 2016, 387, 1762–1774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Klepp, O.; Flodgren, P.; Maartman-Moe, H.; Lindholm, C.E.; Unsgaard, B.; Teigum, H.; et al. Early clinical stages (CS1, CS1Mk+ and CS2A) of non-seminomatous testis cancer. Value of pre- and post-orchiectomy serum tumor marker information in prediction of retroperitoneal lymph node metastases. Swedish-Norwegian Testicular Cancer Project (SWENOTECA). Ann Oncol. 1990, 1, 281–288. [Google Scholar]

- Verhoeven, R.H.; Karim-Kos, H.E.; Coebergh, J.W.; Brink, M.; Horenblas, S.; de Wit, R.; et al. Markedly increased incidence and improved survival of testicular cancer in the Netherlands. Acta Oncol. 2014, 53, 342–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oldenburg, J.; Berney, D.M.; Bokemeyer, C.; Climent, M.A.; Daugaard, G.; Gietema, J.A.; et al. Testicular seminoma and non-seminoma: ESMO-EURACAN Clinical Practice Guideline for diagnosis, treatment and follow-up. Ann Oncol. 2022, 33, 362–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Parameter | Equation | Definition |

|---|---|---|

| Specific growth rate (SGR) | ln(V2/V1)/(t2-t1) (%volume/day) | percentage volume increase per unit of time |

| Doubling time (DT) | ln(2)/SGR (Days) | amount of time it takes for the lesion to double in volume |

| velocity of increase of the maximum diameter (∆Dmax) | (Dmax2-Dmax1)/(t2-t1) (mm/days) | velocity of increase of the maximum diameter |

| velocity of increase of the average diameter (∆Dav) | (Dav2-Dav1)/(t2-t1)(mm/days) | velocity of increase of the average diameter |

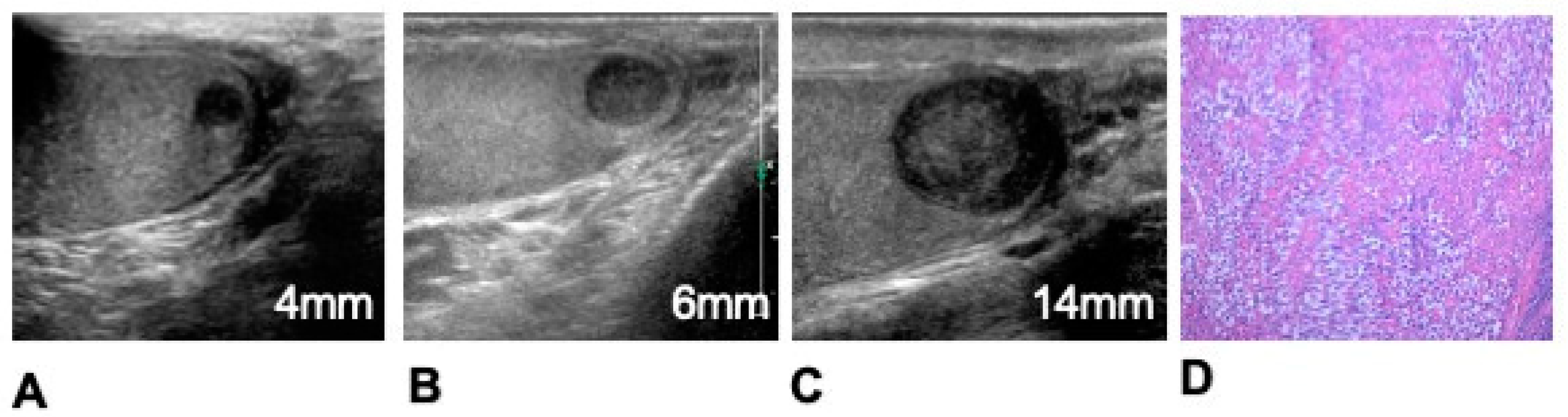

| Malignant tumours (n=18) | Growing (n=18) | Seminoma (n=17) Non-seminoma (n=1) |

|---|---|---|

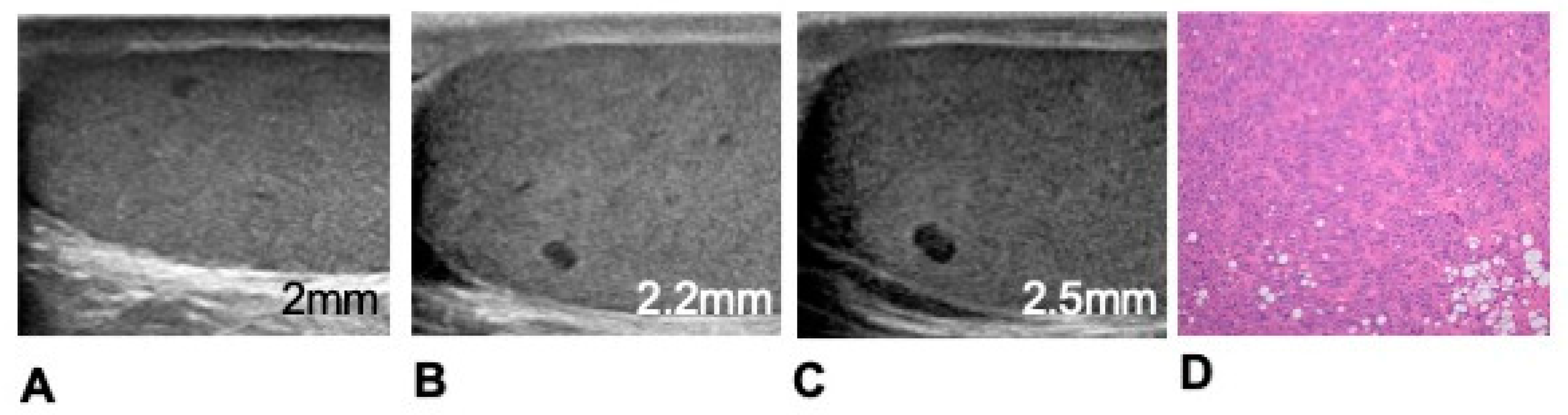

| Benign tumours (n=9) | Stable (n=1) | Leydigoma (n=1) |

| Growing (n=8) | Leydigoma (n=7) Capillary haemangioma (n=1) |

|

| Non-neoplastic lesions (n=12) | Stable (n=10) | Leydig cell hyperplasia (n=6) Fibrosis (n=3) Granulomatous orchitis (n=1) |

| Growing (n=2) | Leydig cell hyperplasia (n=2) |

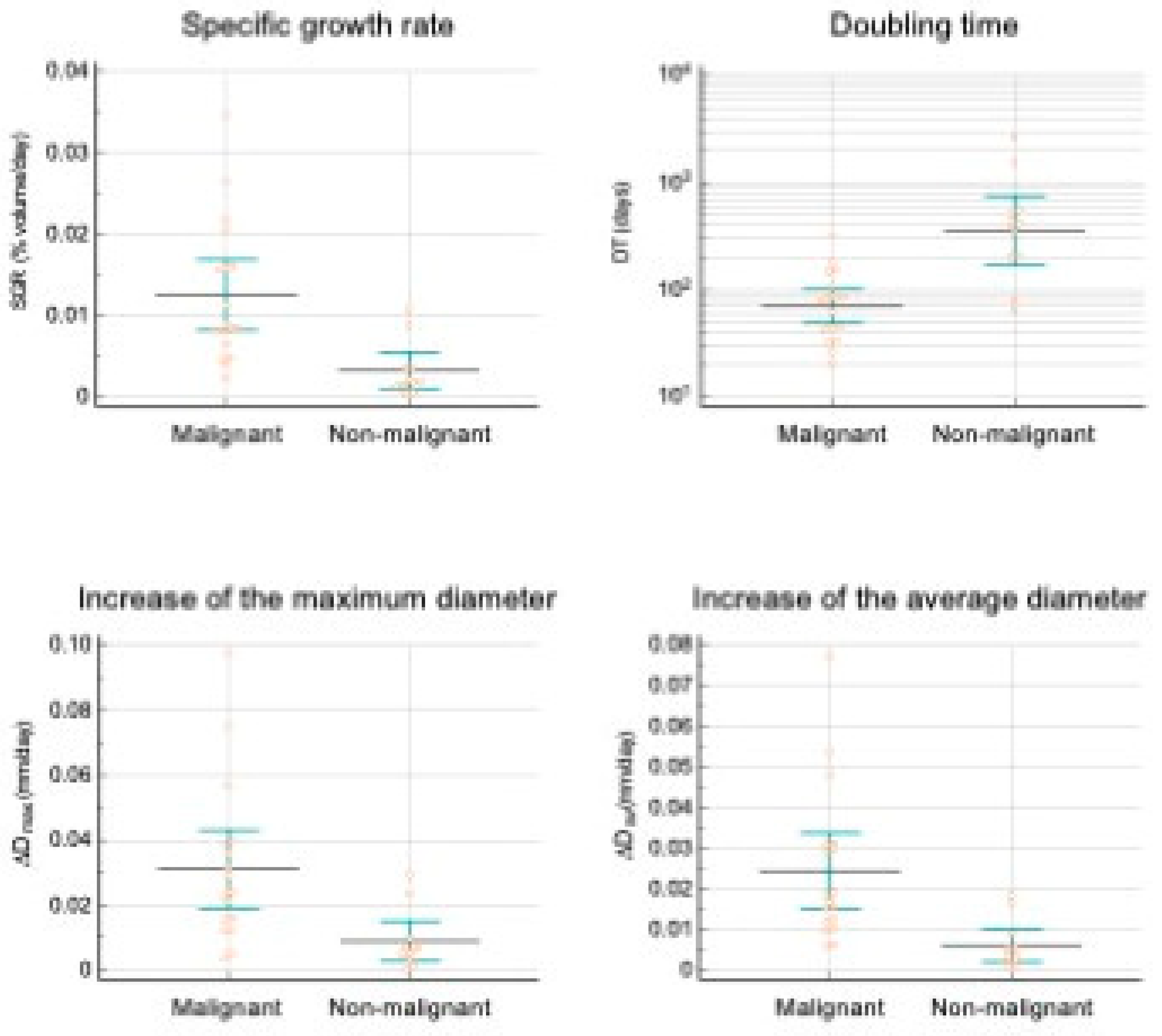

| Growth indicator | Malignant lesions* | Non malignant lesions* | P |

|---|---|---|---|

| SGR (%volume/day) | 11.4±2.11x10-3 | 3.47±1.1x10-3 | <0.003 |

| DT (days) | 90±17 | 535±236 | 0.093 |

| ∆Dmax | 31±6 x10-3 | 9±3 x10-3 | <0.003 |

| ∆Dav | 24±4 x10-3 | 7±2 x10-3 | <0.002 |

| Growth indicator | AUC* | Associated criterion (Youden index J) | Sensitivity | Specificity |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| SGR (%/day) | 0.883±0.075 | >3.47x10-3 | 94.44 | 80.00 |

| DT (days) | 0.883±0.075 | ≤179 | 94.44 | 80.00 |

| ∆Dmax | 0.839±0.082 | >10 x10-3 | 88.89 | 80.00 |

| ∆Dav | 0.889±0.071 | >5 x10-3 | 100.00 | 70.00 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).