Submitted:

11 August 2023

Posted:

14 August 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

Introduction

Materials and Methods

Patient Collective

Immunohistochemical analysis

Statistical analysis

Results

Patients’ characteristics

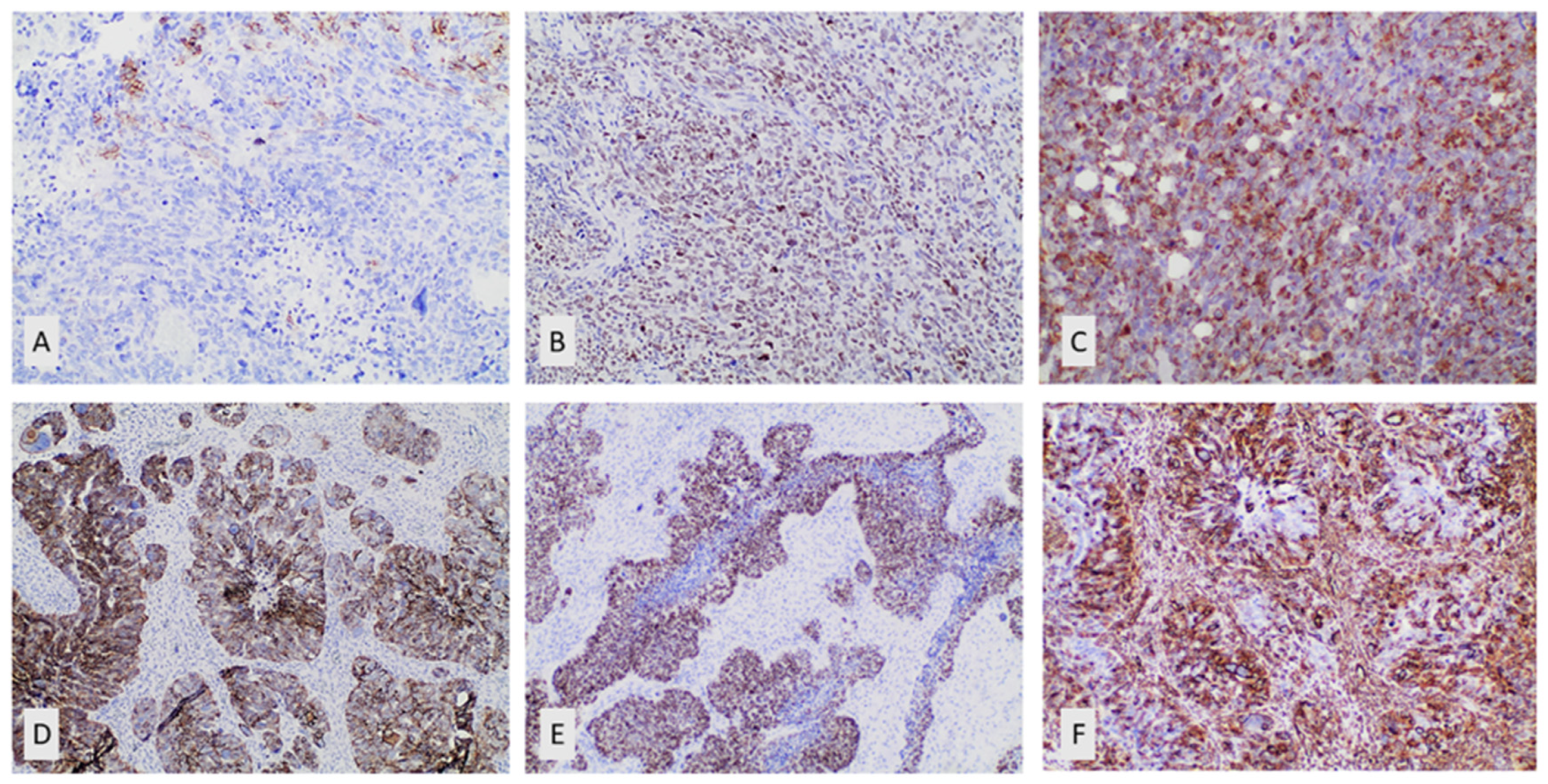

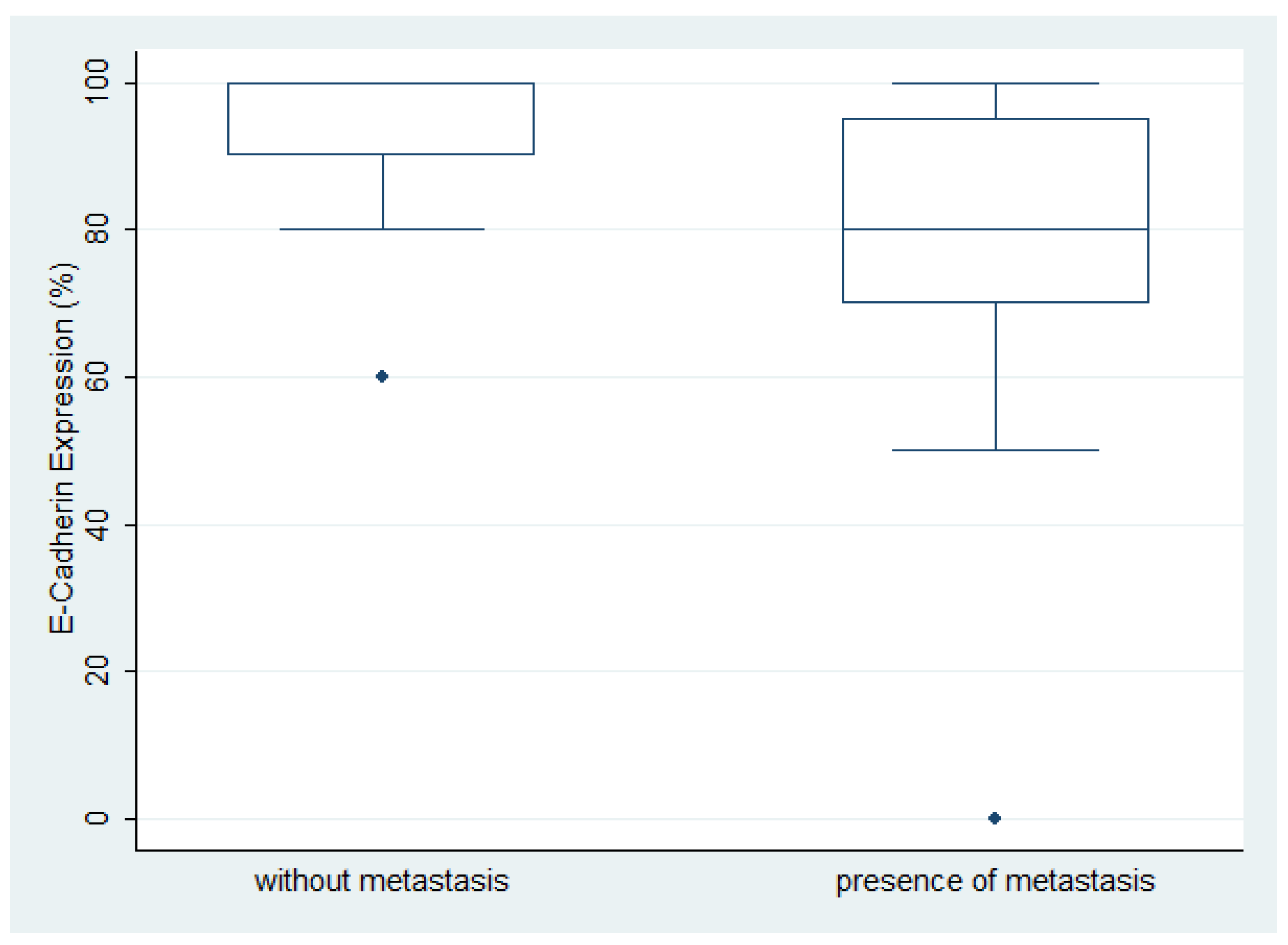

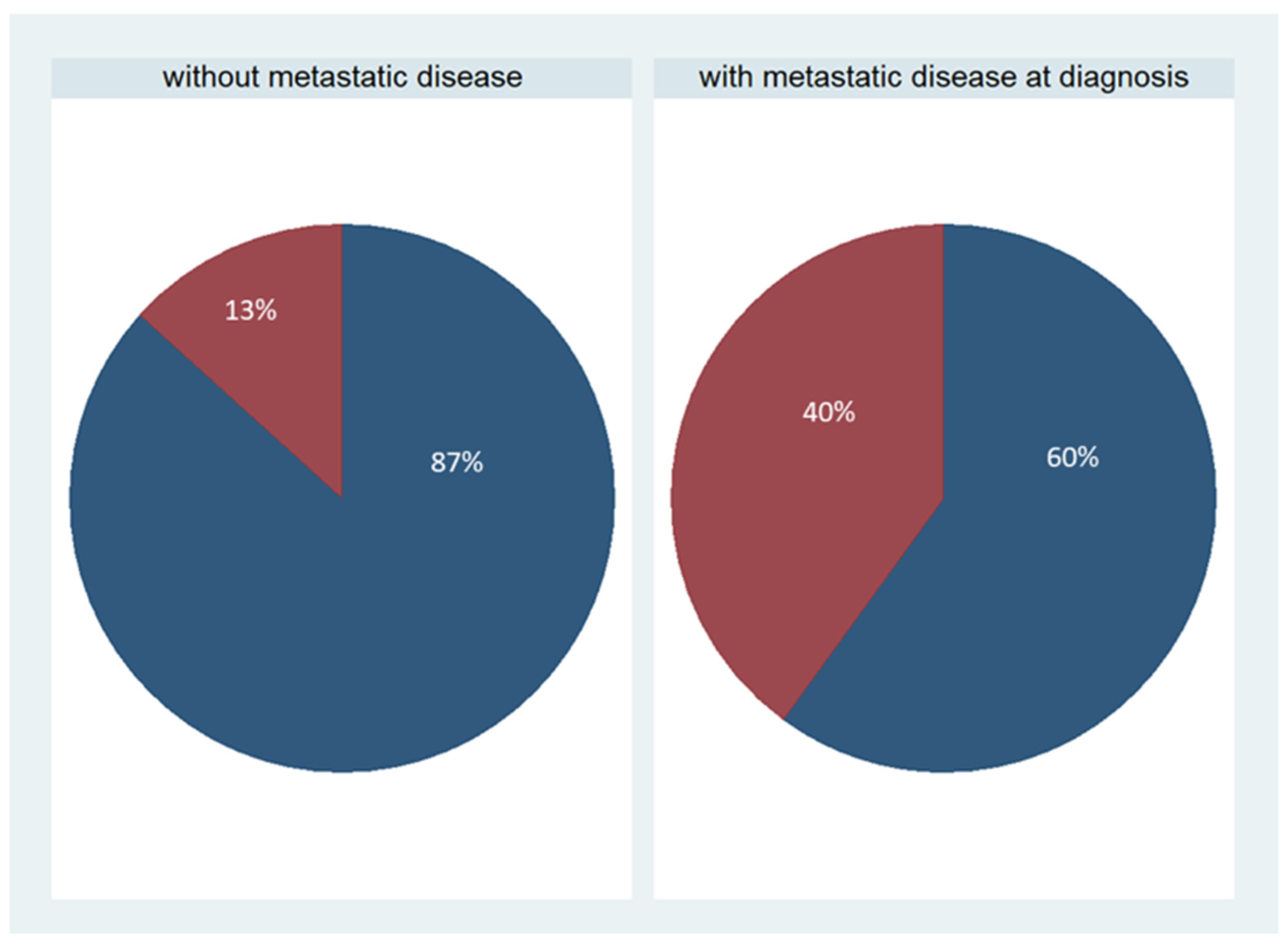

Immunohistochemical expression of E-Cadherin in ovarian serous carcinoma

Immunohistochemical expression of Vimentin in ovarian serous carcinoma

Immunohistochemical expression of SOX11 in ovarian serous carcinoma

Associations between the examined molecules

Discussion

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Society AC. Key Statistics for Ovarian Cancer: American Cancer Society 2023 [Available from: https://www.cancer.org/cancer/types/ovarian-cancer/about/key-statistics.html.

- Prat J. Ovarian carcinomas: five distinct diseases with different origins, genetic alterations, and clinicopathological features. Virchows Arch. 2012;460(3):237-49.

- Seebacher V, Reinthaller A, Koelbl H, Concin N, Nehoda R, Polterauer S. The Impact of the Duration of Adjuvant Chemotherapy on Survival in Patients with Epithelial Ovarian Cancer - A Retrospective Study. PLoS One. 2017;12(1):e0169272.

- Psilopatis I, Sykaras AG, Mandrakis G, Vrettou K, Theocharis S. Patient-Derived Organoids: The Beginning of a New Era in Ovarian Cancer Disease Modeling and Drug Sensitivity Testing. Biomedicines. 2022;11(1).

- Society AC. Survival Rates for Ovarian Cancer: American Cancer Society 2023 [Available from: https://www.cancer.org/cancer/types/ovarian-cancer/detection-diagnosis-staging/survival-rates.html.

- Society AC. Tests for Ovarian Cancer: American Cancer Society; 2022 [Available from: https://www.cancer.org/cancer/types/ovarian-cancer/detection-diagnosis-staging/how-diagnosed.html.

- Kalluri R, Neilson EG. Epithelial-mesenchymal transition and its implications for fibrosis. J Clin Invest. 2003;112(12):1776-84.

- Kalluri R, Weinberg RA. The basics of epithelial-mesenchymal transition. J Clin Invest. 2009;119(6):1420-8.

- Yang J, Weinberg RA. Epithelial-mesenchymal transition: at the crossroads of development and tumor metastasis. Dev Cell. 2008;14(6):818-29.

- Brabletz T, Jung A, Reu S, Porzner M, Hlubek F, Kunz-Schughart LA, Knuechel R, Kirchner T. Variable beta-catenin expression in colorectal cancers indicates tumor progression driven by the tumor environment. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2001;98(18):10356-61.

- Fidler IJ, Poste G. The "seed and soil" hypothesis revisited. Lancet Oncol. 2008;9(8):808.

- Thiery JP. Epithelial-mesenchymal transitions in tumour progression. Nat Rev Cancer. 2002;2(6):442-54.

- Lefebvre V, Dumitriu B, Penzo-Mendez A, Han Y, Pallavi B. Control of cell fate and differentiation by Sry-related high-mobility-group box (Sox) transcription factors. Int J Biochem Cell Biol. 2007;39(12):2195-214.

- Penzo-Mendez AI. Critical roles for SoxC transcription factors in development and cancer. Int J Biochem Cell Biol. 2010;42(3):425-8.

- de Bont JM, Kros JM, Passier MM, Reddingius RE, Sillevis Smitt PA, Luider TM, den Boer ML, Pieters R. Differential expression and prognostic significance of SOX genes in pediatric medulloblastoma and ependymoma identified by microarray analysis. Neuro Oncol. 2008;10(5):648-60.

- Jay P, Goze C, Marsollier C, Taviaux S, Hardelin JP, Koopman P, Berta P. The human SOX11 gene: cloning, chromosomal assignment and tissue expression. Genomics. 1995;29(2):541-5.

- Harrison G, Hemmerich A, Guy C, Perkinson K, Fleming D, McCall S, Cardona D, Zhang X. Overexpression of SOX11 and TFE3 in Solid-Pseudopapillary Neoplasms of the Pancreas. Am J Clin Pathol. 2017;149(1):67-75.

- Weigle B, Ebner R, Temme A, Schwind S, Schmitz M, Kiessling A, Rieger MA, Schackert G, Schackert HK, Rieber EP. Highly specific overexpression of the transcription factor SOX11 in human malignant gliomas. Oncol Rep. 2005;13(1):139-44.

- Zhang LN, Cao X, Lu TX, Fan L, Wang L, Xu J, Zhang R, Zou ZJ, Wu JZ, Li JY, et al. Polyclonal antibody targeting SOX11 cannot differentiate mantle cell lymphoma from B-cell non-Hodgkin lymphomas. Am J Clin Pathol. 2013;140(6):795-800.

- Shepherd JH, Uray IP, Mazumdar A, Tsimelzon A, Savage M, Hilsenbeck SG, Brown PH. The SOX11 transcription factor is a critical regulator of basal-like breast cancer growth, invasion, and basal-like gene expression. Oncotarget. 2016;7(11):13106-21.

- Oliemuller E, Newman R, Tsang SM, Foo S, Muirhead G, Noor F, Haider S, Aurrekoetxea-Rodriguez I, Vivanco MD, Howard BA. SOX11 promotes epithelial/mesenchymal hybrid state and alters tropism of invasive breast cancer cells. Elife. 2020;9.

- Meinhold-Heerlein I, Fotopoulou C, Harter P, Kurzeder C, Mustea A, Wimberger P, Hauptmann S, Sehouli J, Kommission Ovar of the AGO. Statement by the Kommission Ovar of the AGO: The New FIGO and WHO Classifications of Ovarian, Fallopian Tube and Primary Peritoneal Cancer. Geburtshilfe Frauenheilkd. 2015;75(10):1021-7.

- Huh S, Kang C, Park JE, Nam D, Kim SI, Seol A, Choi K, Hwang D, Yu MH, Chung HH, et al. Novel Diagnostic Biomarkers for High-Grade Serous Ovarian Cancer Uncovered by Data-Independent Acquisition Mass Spectrometry. J Proteome Res. 2022;21(9):2146-59.

- Atallah GA, Abd Aziz NH, Teik CK, Shafiee MN, Kampan NC. New Predictive Biomarkers for Ovarian Cancer. Diagnostics (Basel). 2021;11(3).

- Loh CY, Chai JY, Tang TF, Wong WF, Sethi G, Shanmugam MK, Chong PP, Looi CY. The E-Cadherin and N-Cadherin Switch in Epithelial-to-Mesenchymal Transition: Signaling, Therapeutic Implications, and Challenges. Cells. 2019;8(10).

- Na TY, Schecterson L, Mendonsa AM, Gumbiner BM. The functional activity of E-cadherin controls tumor cell metastasis at multiple steps. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2020;117(11):5931-7.

- Loret N, Denys H, Tummers P, Berx G. The Role of Epithelial-to-Mesenchymal Plasticity in Ovarian Cancer Progression and Therapy Resistance. Cancers (Basel). 2019;11(6).

- Brennan DJ, Ek S, Doyle E, Drew T, Foley M, Flannelly G, O'Connor DP, Gallagher WM, Kilpinen S, Kallioniemi OP, et al. The transcription factor Sox11 is a prognostic factor for improved recurrence-free survival in epithelial ovarian cancer. Eur J Cancer. 2009;45(8):1510-7.

- Sernbo S, Gustavsson E, Brennan DJ, Gallagher WM, Rexhepaj E, Rydnert F, Jirstrom K, Borrebaeck CA, Ek S. The tumour suppressor SOX11 is associated with improved survival among high grade epithelial ovarian cancers and is regulated by reversible promoter methylation. BMC Cancer. 2011;11:405.

- Davidson B, Holth A, Hellesylt E, Tan TZ, Huang RY, Trope C, Nesland JM, Thiery JP. The clinical role of epithelial-mesenchymal transition and stem cell markers in advanced-stage ovarian serous carcinoma effusions. Hum Pathol. 2015;46(1):1-8.

- Fang G, Liu J, Wang Q, Huang X, Yang R, Pang Y, Yang M. MicroRNA-223-3p Regulates Ovarian Cancer Cell Proliferation and Invasion by Targeting SOX11 Expression. Int J Mol Sci. 2017;18(6).

- Xiao Y, Xie Q, Qin Q, Liang Y, Lin H, Zeng D. Upregulation of SOX11 enhances tamoxifen resistance and promotes epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition via slug in MCF-7 breast cancer cells. J Cell Physiol. 2020;235(10):7295-308.

- Saitoh M. Involvement of partial EMT in cancer progression. J Biochem. 2018;164(4):257-64.

- Norgard RJ, Pitarresi JR, Maddipati R, Aiello-Couzo NM, Balli D, Li J, Yamazoe T, Wengyn MD, Millstein ID, Folkert IW, et al. Calcium signaling induces a partial EMT. EMBO Rep. 2021;22(9):e51872.

| Patients’ characteristics | Median value | Value range |

|---|---|---|

| Age (in years) | 61,5 | 46-92 |

| FIGO stadium | Number of patients | Percentage |

| I | 7 | 23% |

| II | 3 | 10% |

| III | 11 | 37% |

| IV | 9 | 30% |

| Tumor grade | Number of patients | Percentage |

| Low grade | 5 | 17% |

| High grade | 25 | 83% |

| Metastasis | Number of patients | Percentage |

| Metastatic cancer | 15 | 50% |

| Non-metastatic cancer | 15 | 50% |

| Residual disease | ||

| None/minimal | 25 | 83% |

| >2cm | 5 | 17% |

| Event | Number of patients | Percentage |

| Death of disease | 6/21 (follow-up: 3,4-35 months) | 28% |

| Censored | 15/21 (follow-up: 5-68 months) | 71% |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).