Submitted:

09 August 2023

Posted:

09 August 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

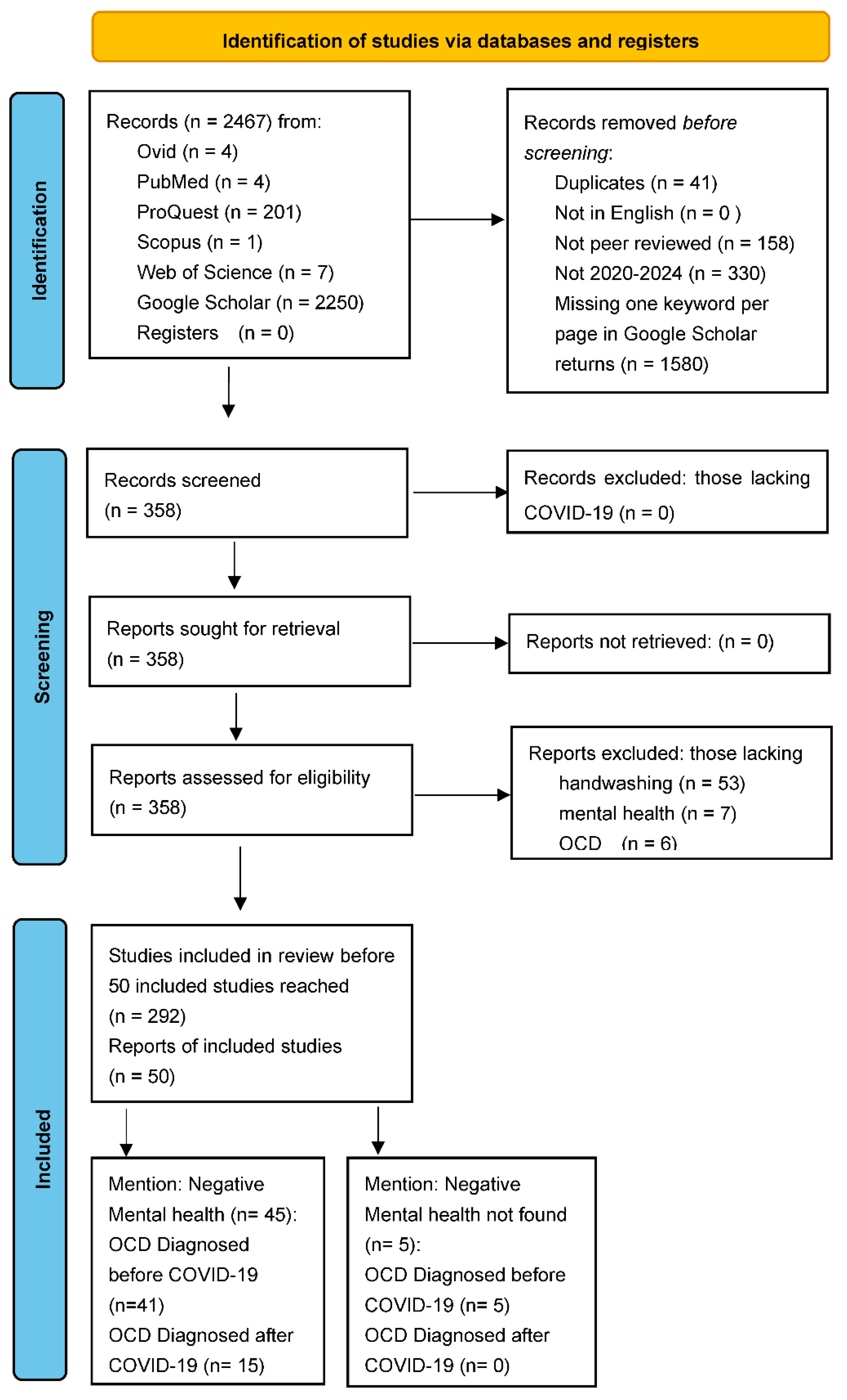

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results

3.1. Returns of the Primary Databases Searched

3.1.1. Searches Performed 21 July 2023

3.1.2. Searches Performed 23 July 2023

3.2. Comparing Duplications Regarding the Google Scholar Returns

3.3. Studies Included of the Unique Returns of Google Scholar

4. Discussion

4.1. Five Articles Not Finding Negative Mental Health in Those Diagnosed with OCD

4.2. Limitations

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Rodriguez-Morales, A.J.; Lopez-Echeverri, M.C.; Perez-Raga, M.F.; Quintero-Romero, V.; Valencia-Gallego, V.; Galindo-Herrera, N.; López-Alzate, S.; Sánchez-Vinasco, J.D.; Gutiérrez-Vargas, J.J.; Mayta-Tristan, P.; Husni, R.; Moghnieh, R.; Stephan, J.; Faour, W.; Tawil, S.; Barakat, H.; Chaaban, T.; Megarbane, A.; Rizk, Y.; Sakr, R.; … Ulloa-Gutiérrez, R. (2023). The global challenges of the long COVID-19 in adults and children. Travel Med. Infect. Diseases 2023, 54, 102606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lewis, D. COVID-19 rarely spreads through surfaces. So why are we still deep cleaning? Nature 2021, 590, 26–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, C.C.; Prather, K.A.; Sznitman, J.; Jimenez, J.L.; Lakdawala, S.S.; Tufekci, Z; Marr, L. C. Airborne transmission of respiratory viruses. Science 2021, 373, eabd9149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arienzo, A.; Gallo, V.; Tomassetti, F.; Pitaro, N.; Pitaro, M.; Antonini, G. A narrative review of alternative transmission routes of COVID 19: what we know so far. Pathogens Glob. Health 2023, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwiatkowska, A.; Granicka, L.H. Anti-Viral Surfaces in the Fight against the Spread of Coronaviruses. Membranes 2023, 13, 464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goldman, E. Exaggerated risk of transmission of COVID-19 by fomites. Lancet Infect. Dis. 2020, 20, 892–893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mondelli, M.U.; Colaneri, M.; Seminari, E.M.; Baldanti, F.; Bruno, R. Low risk of SARS-CoV-2 transmission by fomites in real-life conditions. The Lancet Infectious Diseases 2021, 21, e112–e112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, B.Y.; You Can Get Covid-19 From Coronavirus-Contaminated Surfaces, New Study Confirms. Forbes 2023, 8 April. Available online: https://www.forbes.com/sites/brucelee/2023/04/08/you-can-get-covid-19-from-coronavirus-contaminated-surfaces-new-study-confirms/?sh=1881b4cc68fd (accessed on 19 July 2023).

- Derqui, N.; Koycheva, A.; Zhou, J.; Pillay, T.D.; Crone, M.A.; Hakki, S.; Fenn, J.; Kundu, R.; Varro, R.; Conibear, E.; Madon, K. J.; Barnett, J.L.; Houston, H.; Singanayagam, A.; Narean, J.S.; Tolosa-Wright, M.R.; Mosscrop, L.; Rosadas, C.; Watber, P. … Ferguson, N.M. (2023). Risk factors and vectors for SARS-CoV-2 household transmission: a prospective, longitudinal cohort study. Lancet Microbe 2023, 4, e397–e408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nembhard, M.D.; Burton, D.J.; Cohen, J.M. Ventilation use in nonmedical settings during COVID-19: Cleaning protocol, maintenance, and recommendations. Toxicol. Indust. Health. 2020, 36, 644–653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morawska, L.; Tang, J.W.; Bahnfleth, W.; Bluyssen, P.M.; Boerstra, A.; Buonanno, G.; Cao, J.; Dancer, S.; Floto, A.; Franchimon, F.; Haworth, C. How can airborne transmission of COVID-19 indoors be minimised? Enviro. Inter. 2020, 142, 105832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. Handwashing an effective tool to prevent COVID-19, other diseases World Health Organization: South East Asia 2020, 15 October. Available online: https://www.who.int/southeastasia/news/detail/15-10-2020-handwashing-an-effective-tool-to-prevent-covid-19-other-diseases (accessed on 20 July 2023).

- Rundle, C.W.; Presley, C.L.; Militello, M.; Barber, C.; Powell, D.L.; Jacob, S.E.; Atwater, A.R.; Watsky, K.L.; Yu, J.; Dunnick, C.A. Hand hygiene during COVID-19: recommendations from the American Contact Dermatitis Society. J. Amer. Acad. Dermatol. 2020, 83, 1730–1737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parida, S.P.; Bhatia, V. (2020). Handwashing: a household social vaccine against COVID 19 and multiple communicable diseases. Int. J. Res. Med. Sci. 2020, 8, 2708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaçar, A.S. Obsessive-compulsive disorder during and after Covid-19 pandemic. In Mental health effects of COVID-19. Moustafa, A.A., Ed; . Academic Press: London, England, U.K, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-5®); American Psychiatric Association: Washington, DC, U.S.A., 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Van Ameringen, M.; Patterson, B.; Turna, J.; Lethbridge, G.; Goldman Bergmann, C.; Lamberti, N.; Rahat, M.; Sideris, B.; Francisco, A.P.; Fineberg, N.; Pallanti, S.; Grassi, G.; Vismara, M.; Albert, U.; Gedanke Shavitt, R.; Hollander, E.; Feusner, J.; Rodriguez, C.I.; Morgado, P.; Dell'Osso, B. Obsessive-compulsive disorder during the COVID-19 pandemic. J. Psychiat. Res. 2022, 149, 114–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Page, M.J.; Moher, D.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E.; Chou, R.; Glanville, J.; Grimshaw, J.M.; Hróbjartsson, A.; Lalu, M.M.; Li, T.; Loder, E.W.; Mayo-Wilson, E.; McDonald, S.; McGuinness, L.A.; Stewart, L.A.; Thomas, J.; Tricco, A.C.; Welch, V.A.; Whiting, P.; McKenzie, J.E. PRISMA 2020 explanation and elaboration: updated guidance and exemplars for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ, 2021, 372, n160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- National Institute for Health and Care Research. Accessing and completing the registration form. International Prospective Register of Systematic Reviews (PROSPERO). University of York: York, U.K., 2023. Available online: https://www.crd.york.ac.uk/prospero/#aboutregpage (accessed on 7 July 2023).

- Peters, M.D.J.; Marnie, C.; Colquhoun, H.; … Tricco, A.C. Scoping reviews: reinforcing and advancing the methodology and application. Syst. Rev. 2021, 10, 263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Augustus, C.; Long Health Sciences Library. PROSPERO: A registry for systematic review protocols. Columbia University Irving Medical Center: New York, NY, U.S.A. Available online: https://library.cumc.columbia.edu/insight/prospero-registry-systematic-review-protocols#:~:text=Systematic%20Reviews%20are%20comprehensive%2C%20in,analysis%20and%20synthesis%20of%20results. (accessed on 7 July 2023).

- Gusenbauer, M. Google Scholar to overshadow them all? Comparing the sizes of 12 academic search engines and bibliographic databases. Scientometrics 2019, 118, 177–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Healey, M.; Healey, R.L. Searching the Literature on Scholarship of Teaching and Learning (SoTL): An Academic Literacies Perspective: Part 1. Teach. Learn. Inq. 2023, 11, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gusenbauer, M.; Haddaway, N.R. (2020). Which academic search systems are suitable for systematic reviews or meta-analyses? Evaluating retrieval qualities of Google Scholar, PubMed, and 26 other resources. Res. Synth. Meth. 2020, 11, 181–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demaria, F.; Pontillo, M.; Di Vincenzo, C.; Di Luzio, M.; Vicari, S. Hand Washing: When Ritual Behavior Protects! Obsessive–Compulsive Symptoms in Young People during the COVID-19 Pandemic: A Narrative Review. J. Clin. Med. 2022, 11, 3191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dennis, D.; Radnitz, C.; Wheaton, M.G. A Perfect Storm? Health Anxiety, Contamination Fears, and COVID-19: Lessons Learned from Past Pandemics and Current Challenges. Int. J. Cognit. Ther. 2021, 14, 497–513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alateeq, D.A.; Almughera, H.N.; Almughera, T.N.; Alfedeah, R.F.; Nasser, T.S.; Alaraj, K.A. The impact of the coronavirus (COVID-19) pandemic on the development of obsessive-compulsive symptoms in Saudi Arabia. Saudi Med. J. 2021, 42, 750–760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abba-Aji, A.; Li, D.; Hrabok, M.; Shalaby, R.; Gusnowski, A.; Vuong, W.; Surood, S.; Nkire, N.; Li, X.-M.; Greenshaw, A.J.; et al. COVID-19 Pandemic and Mental Health: Prevalence and Correlates of New-Onset Obsessive-Compulsive Symptoms in a Canadian Province. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 6986. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hezel, D.M.; Rapp, A.M.; Wheaton, M.G.; Kayser, R.R.; Rose, S.V.; Messner, G.R.; Middleton, R.; Simpson, H.B. Resilience predicts positive mental health outcomes during the COVID-19 pandemic in New Yorkers with and without obsessive-compulsive disorder. J. Psychiatr. Res 2022, 150, 165–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ornell, F.; Braga, D.T.; Bavaresco, D.V.; Francke, I.D.; Scherer, J.N.; von Diemen, L.; Kessler, F.H.P. Obsessive-compulsive disorder reinforcement during the COVID-19 pandemic. Trends Psychiat. Psychother. 2021, 43, 81–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- de Jesus, S.; Costa, A.L.R.; Almeida, M.; Garrido, P.; Alcafache, J. (2023). Conradi-Hünerman-Happle Syndrome and Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder: a clinical case report. BMC Psychiatry 2023, 23, 87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gokhale, M.V.; Swarupa, C. A review of effects of pandemic on the patients of obsessive-compulsive disorder. Cureus 2022, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perkes, I.E.; Brakoulias, V.; Lam-Po-Tang, J.; Castle, D.J.; Fontenelle, L.F. Contamination compulsions and obsessive-compulsive disorder during COVID-19. Austra. New Zeal. J. Psychia. 2020, 54, 1137–1138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fiaschè, F.; Kotzalidis, G.D.; Alcibiade, A.; Antonio, D.C. (2023). Obsessive-compulsive disorder during the COVID-19 pandemic. Psychia.Inter. 2023, 4, 102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taher, T.M.J.; Al-fadhul, S.; Abutiheen, A.A.; Ghazi, H.F.; Abood, N.S. Prevalence of obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD) among iraqi undergraduate medical students in time of COVID-19 pandemic. Middle East Curr. Psychia. 2021, 28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bibawy, D.; Barco, J.; Sounboolian, Y.; Atodaria, P. A case of new-onset obsessive-compulsive disorder and schizophrenia in a 14-year-old male following the COVID-19 pandemic. Case Rep. Psychia. 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hassan, S.M.; Ring, A.; Tahir, N.; Gabbay, M. The impact of COVID-19 social distancing and isolation recommendations for muslim communities in north west england. BMC Public Health 2021, 21, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chakraborty, A.; Karmakar, S. (2020). Impact of COVID-19 on obsessive compulsive disorder (OCD). Iranian J. Psychia. 2020, 15, 256–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hisham, M.; Shuchita, S.; Mikael, M.; Aysun, T.; Romil, S.; Lundeen, J. . Rahul, K. The well-being of healthcare workers during the COVID-19 pandemic: A narrative review. Cureus 2022, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giordano, D.; Magliacano, A.; Bernardo, D.; Lamberti, H.; Luciani, A.; Mariniello, T.S. . de Bartolomeis, A. Effects of strict COVID-19 lockdown on patients with obsessive-compulsive disorder compared to a clinical and a nonclinical sample. Euro. Psychia. 2023, 66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costa, A.; Jesus, S.; Simões, L.; Almeida, M.; Alcafache, J. A case of obsessive-compulsive disorder triggered by the pandemic. Psych 2021, 3, 890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malas, O.; Tolsa, M.-D. The COVID-19 Pandemic and the Obsessive-Compulsive Phenomena, in the General Population and among OCD Patients: A Systematic Review. Euro. J. Mental Health 2022, 17, 132–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sulaimani, M.F.; Bagadood, N.H. (2021). Implication of coronavirus pandemic on obsessive-compulsive-disorder symptoms. Rev.Environ. Health 2021, 36, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, A.; Somani, A. Dealing with Corona virus anxiety and OCD. Asian J. Psychia. 2020, 51, 102053–102053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shafran, R.; Coughtrey, A.; Whittal, M. Recognising and addressing the impact of COVID-19 on obsessive-compulsive disorder. Lancet Psychia. 2020, 7, 570–572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Ameringen, M.; Patterson, B.; Turna, J.; Lethbridge, G.; Goldman Bergmann, C.; Lamberti, N.; Rahat, M.; Sideris, B.; Francisco, A.P.; Fineberg, N.; Pallanti, S.; Grassi, G.; Vismara, M.; Albert, U.; Gedanke Shavitt, R.; Hollander, E.; Feusner, J.; Rodriguez, C.I.; Morgado, P.; Dell’Osso, B. Obsessive-compulsive disorder during the COVID-19 pandemic. J. Psychia. Res. 2022, 149, 114–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, A.; Nayar, K.R. COVID 19 and its mental health consequences. J. Mental Health 2021, 30, 1–2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hassoulas, A.; Umla-Runge, K; Zahid, A. ; Adams, O.; Green, M.; Hassoulas, A.; Panayiotou, E. Investigating the Association Between Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder Symptom Subtypes and Health Anxiety as Impacted by the COVID-19 Pandemic: A Cross-Sectional Study. Psycholo.Rep. 2022, 125, 3006–3027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Matsunaga, H.; Mukai, K.; Yamanishi, K. Acute impact of COVID-19 pandemic on phenomenological features in fully or partially remitted patients with obsessive–compulsive disorder. Psychia. Clinic. Neurosci. 2020, 2020 74, 565–566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Linde, E.S.; Varga, T.V.; Clotworthy, A. Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder During the COVID-19 Pandemic-A Systematic Review. Front. Psychia. 2022, 13, 806872–806872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jassi, A.; Shahriyarmolki, K.; Taylor, T.; Peile, L.; Challacombe, F.; Clark, B.; Veale, D. OCD and COVID-19: a new frontier. Cogni. Behav. Thera. 2020, 13, e27–e27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Quittkat, H.L.; Düsing, R.; Holtmann, F.-J.; Buhlmann, U.; Svaldi, J.; Vocks, S. Perceived Impact of Covid-19 Across Different Mental Disorders: A Study on Disorder-Specific Symptoms, Psychosocial Stress and Behavior. Front. Psycholo. 2020, 11, 586246–586246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- French, I.; Lyne, J. Acute exacerbation of OCD symptoms precipitated by media reports of COVID-19. Irish J. Psycholo. Med. 2020, 37, 291–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sahoo, S.; Bharadwaj, S.; Mehra, A.; Grover, S. COVID-19 as a “nightmare” for persons with obsessive-compulsive disorder: A case report from India. J. Mental Health Human Behav. 2020, 25, 146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maye, C.E.; Wojcik, K.D.; Candelari, A.E.; Goodman, W.K.; Storch, E.A. Obsessive compulsive disorder during the COVID-19 pandemic: A brief review of course, psychological assessment and treatment considerations. J. OCRD 2022, 33, 100722–100722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berman, N.C.; Fang, A.; Hoeppner, S.S.; Reese, H.; Siev, J.; Timpano, K.R.; Wheaton, M.G. COVID-19 and obsessive-compulsive symptoms in a large multi-site college sample. J. OCRD 2022, 33, 100727–100727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davide, P.; Andrea, P.; Martina, O.; Andrea, E.; Davide, D.; Mario, A. (2020). The impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on patients with OCD: Effects of contamination symptoms and remission state before the quarantine in a preliminary naturalistic study. Psychia Res. 2020, 291, 113213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jain, A.; Bodicherla, K.P.; Bashir, A.; Batchelder, E.; Jolly, T.S. (2021). COVID-19 and obsessive-compulsive disorder: the nightmare just got real. Prim. Care Companion CNS Disord. 2021, 23, 29372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El Othman, R.; Touma, E.; El Othman, R.; Haddad, C.; Hallit, R.; Obeid, S.; Salameh, P.; Hallit, S. COVID-19 pandemic and mental health in Lebanon: a cross-sectional study. Int. J. Psychia. Clin. Pract. 2021, 25, 152–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cunning, C.; Hodes, M. , The COVID-19 pandemic and obsessive–compulsive disorder in young people: Systematic review. Clin. Child Psycholo. Psychia. 2022, 27, 18–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dar, S.A.; Dar, M.M.; Sheikh, S.; Haq, I.; Azad, A.M.U.D.; Mushtaq, M.; Shah, N.N.; Wani, Z.A. Psychiatric comorbidities among COVID-19 survivors in North India: A cross-sectional study. J. Educ. Health Promo. 2021, 10, 309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jalal, B.; Chamberlain, S.R.; Robbins, T.W.; Sahakian, B.J. Obsessive–compulsive disorder—contamination fears, features, and treatment: Novel smartphone therapies in light of global mental health and pandemics (COVID-19). CNS spectrums 2022, 27, 136–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sowmya, A.V.; Singh, P.; Samudra, M.; Javadekar, A.; Saldanha, D. mpact of COVID-19 on obsessive–compulsive disorder: A case series. Indus. Psychia. J. 2021, 30, S237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wheaton, M.G.; Ward, H.E.; Silber, A.; McIngvale, E.; Björgvinsson, T. How is the COVID-19 pandemic affecting individuals with obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD) symptoms? J. Anxiety Dis. 2021, 81, 102410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brewer, G.; Centifanti, L.; Caicedo, J.C.; Huxley, G.; Peddie, C.; Stratton, K.; Lyons, M. Experiences of mental distress during COVID-19: Thematic analysis of discussion forum posts for anxiety, depression, and obsessive-compulsive disorder. Illness, Crisis Loss 2022, 30, 795–811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samuels, J.; Holingue, C.; Nestadt, P.S.; Bienvenu, O.J.; Phan, P.; Nestadt, G. Contamination-related behaviors, obsessions, and compulsions during the COVID-19 pandemic in a United States population sample. J. Psychia. Res. 2021, 138, 155–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jelinek, L.; Moritz, S.; Miegel, F.; Voderholzer, U. Obsessive-compulsive disorder during COVID-19: Turning a problem into an opportunity? J. Anxiety Dis. 2021, 77, 102329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Darvishi, E.; Golestan, S.; Demehri, F.; Jamalnia, S. A cross-sectional study on cognitive errors and obsessive-compulsive disorders among young people during the outbreak of coronavirus disease 2019. Act. Nerv. Super. 2020, 62, 137–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sharma, L.P.; Balachander, S.; Thamby, A.; Bhattacharya, M.; Kishore, C.; Shanbhag, V.; Sekharan, J.T.; Narayanaswamy, J.C.; Arumugham, S.S.; Reddy, J.Y. Impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on the short-term course of obsessive-compulsive disorder. J. Nerv. Mental Dis. 2021, 209, 256–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grant, J.E.; Drummond, L.; Nicholson, T.R.; Fagan, H.; Baldwin, D.S.; Fineberg, N.A.; Chamberlain, S.R. Obsessive-compulsive symptoms and the Covid-19 pandemic: A rapid scoping review. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 2022, 132, 1086–1098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Siddiqui, M.; Wadoo, O.; Currie, J.; Alabdulla, M.; Al Siaghy, A.; AlSiddiqi, A.; Khalaf, E.; Chandra, P.; Reagu, S. The Impact of COVID-19 Pandemic on Individuals With Pre-existing Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder in the State of Qatar: An Exploratory Cross-Sectional Study. Front. Psychia. 2022, 13, 833394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Damirchi, E.S.; Mojarrad, A.; Pireinaladin, S.; Grjibovski, A.M. The role of self-talk in predicting death anxiety, obsessive-compulsive disorder, and coping strategies in the face of coronavirus disease (COVID-19). Iran. J. Psychia. 2020, 15, 182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva Moreira, P.; Ferreira, S.; Couto, B.; Machado-Sousa, M.; Fernández, M.; Raposo-Lima, C.; Sousa, N.; Picó-Pérez, M.; Morgado, P. Protective Elements of Mental Health Status during the COVID-19 Outbreak in the Portuguese Population. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 1910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zaccari, V.; D'Arienzo, M.C.; Caiazzo, T.; Magno, A.; Amico, G.; Mancini, F. , Narrative review of COVID-19 impact on obsessive-compulsive disorder in child, adolescent and adult clinical populations. Front. Psychia. 2021, 12, 575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alonso, P.; Bertolín, S.; Segalàs, J.; Tubío-Fungueiriño, M.; Real, E.; Mar-Barrutia, L.; Fernández-Prieto, M.; Carvalho, S.; Carracedo, A.; Menchón, J.M. , How is COVID-19 affecting patients with obsessive–compulsive disorder? A longitudinal study on the initial phase of the pandemic in a Spanish cohort. Euro. Psychia. 2021, 64, e45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neal, T.; Lienert, P.; Denne, E.; Singh, J.P. A general model of cognitive bias in human judgment and systematic review specific to forensic mental health. Law and human behavior 2022, 46, 99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Database | Research topic on COVID-19 and OCD |

|---|---|

| Ovid | Hand Washing: When Ritual Behavior Protects! |

| Ovid | A Perfect Storm? |

| Ovid | The Impact of the Coronavirus (COVID-19) Pandemic |

| Ovid | COVID-19 Pandemic and Mental Health |

| PubMed | Resilience Predicts Positive Mental Health Outcomes |

| PubMed | Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder Reinforcement |

| PubMed | Conradi-Hünerman-Happle Syndrome |

| ProQuest | A Review of Effects of Pandemic |

| ProQuest | Contamination Compulsions |

| ProQuest | Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder |

| ProQuest | Prevalence of Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder |

| ProQuest | A Case of New-Onset Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder |

| ProQuest | The Impact of COVID-19 Social Distancing |

| ProQuest | Impact of COVID-19 |

| ProQuest | The Well-Being of Healthcare Workers |

| ProQuest | Effects of Strict COVID-19 Lockdown |

| ProQuest | A Case of Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder |

| Web of Science | The COVID-19 Pandemic |

| Web of Science | Implications of Coronavirus Pandemic |

| Web of Science | Dealing with Corona Virus Anxiety |

| Page Number of Google Scholar Returns | Number of Unique Returns |

|---|---|

| 1 | 12 |

| 2 | 16 |

| 3 | 18 |

| 4 | 18 |

| 5 | 18 |

| 6 | 20 |

| 7 | 17 |

| 8 | 17 |

| 9 | 16 |

| 10 | 18 |

| 11 | 20 |

| 12 | 19 |

| 13 | 19 |

| 14 | 20 |

| 15 | 19 |

| 16 | 20 |

| 17 | 20 |

| Research topic on COVID-19 and OCD | OCD Diagnosed Before COVID-19 | OCD Diagnosed During COVID-19 | Negative Mental Health |

|---|---|---|---|

| Hand Washing: When Ritual Behavior Protects! | ✓ | ✕ | ✓ |

| A Perfect Storm? | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| The Impact of the Coronavirus (COVID-19) Pandemic | ✕ | ✓ | ✓ |

| COVID-19 Pandemic and Mental Health | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| Resilience Predicts Positive Mental Health Outcomes | ✓ | ✕ | ✕ |

| Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder Reinforcement | ✓ | ✕ | ✓ |

| Conradi-Hünerman-Happle Syndrome | ✓ | ✕ | ✓ |

| A Review of Effects of Pandemic | ✓ | ✕ | ✓ |

| Contamination Compulsions | ✓ | ✕ | ✕ |

| Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| Prevalence of Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| A Case of New-Onset Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder | ✕ | ✓ | ✓ |

| The Impact of COVID-19 Social Distancing | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| Impact of COVID-19 (India) | ✓ | ✕ | ✕ |

| The Well-Being of Healthcare Workers | ✓ | ✕ | ✓ |

| Effects of Strict COVID-19 Lockdown | ✓ | ✕ | ✓ |

| A Case of Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder | ✕ | ✓ | ✓ |

| The COVID-19 Pandemic | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| Implications of Coronavirus Pandemic | ✓ | ✕ | ✓ |

| Dealing with Corona Virus Anxiety | ✓ | ✕ | ✓ |

| Recognising and Addressing the Impact of COVID-19 | ✓ | ✕ | ✓ |

| Obsessive Compulsive Disorder During the COVID-19 | ✓ | ✕ | ✓ |

| COVID-19 and its Mental Health Consequences | ✓ | ✕ | ✓ |

| Investigating the Association | ✓ | ✕ | ✓ |

| Acute impact of COVID-19 Pandemic | ✓ | ✕ | ✓ |

| Obsessive Compulsive Disorder During the COVID-19 Pan. | ✓ | ✕ | ✓ |

| OCD and COVID-19: a New Frontier | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| Perceived Impact of COVID-19 | ✓ | ✕ | ✓ |

| Acute Exacerbation of OCD Symptoms | ✓ | ✕ | ✓ |

| Obsessive Compulsive Disorder During the COVID-19 Pand. | ✓ | ✕ | ✓ |

| COVID-19 and Obsessive-Compulsive Symptoms | ✓ | ✕ | ✓ |

| The Impact of the COVID-19 Pandemic | ✓ | ✕ | ✓ |

| COVID-19 and Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| COVID-19 Pandemic and Mental Health in Lebanon | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| The COVID-19 Pandemic and Obsessive–Compulsive Dis. | ✓ | ✕ | ✓ |

| Psychiatric Comorbidities Among COVID-19 Survivors | ✕ | ✓ | ✓ |

| Obsessive–Compulsive Disorder—Contamination Fears | ✓ | ✕ | ✓ |

| Impact of COVID-19 on Obsessive–Compulsive Disorder | ✓ | ✕ | ✓ |

| How is the COVID-19 Pandemic Affecting Individuals | ✓ | ✕ | ✓ |

| Experiences of Mental Distress during COVID-19 | ✓ | ✕ | ✕ |

| Contamination-Related Behaviors, Obsessions | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder During COVID-19 | ✓ | ✕ | ✓ |

| A Cross-Sectional Study on Cognitive Errors | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| Impact of the COVID-19 Pandemic | ✓ | ✕ | ✕ |

| Obsessive-Compulsive Symptoms and the Covid-19 Pandem. | ✓ | ✕ | ✓ |

| The Impact of COVID-19 Pandemic on Individuals | ✓ | ✕ | ✓ |

| The Role of Self-Talk in Predicting Death Anxiety | ✓ | ✕ | ✓ |

| Protective Elements of Mental Health Status | ✓ | ✕ | ✓ |

| Narrative Review of COVID-19 Impact | ✓ | ✕ | ✓ |

| How is COVID-19 Affecting Patients | ✓ | ✕ | ✓ |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).