Submitted:

04 August 2023

Posted:

08 August 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

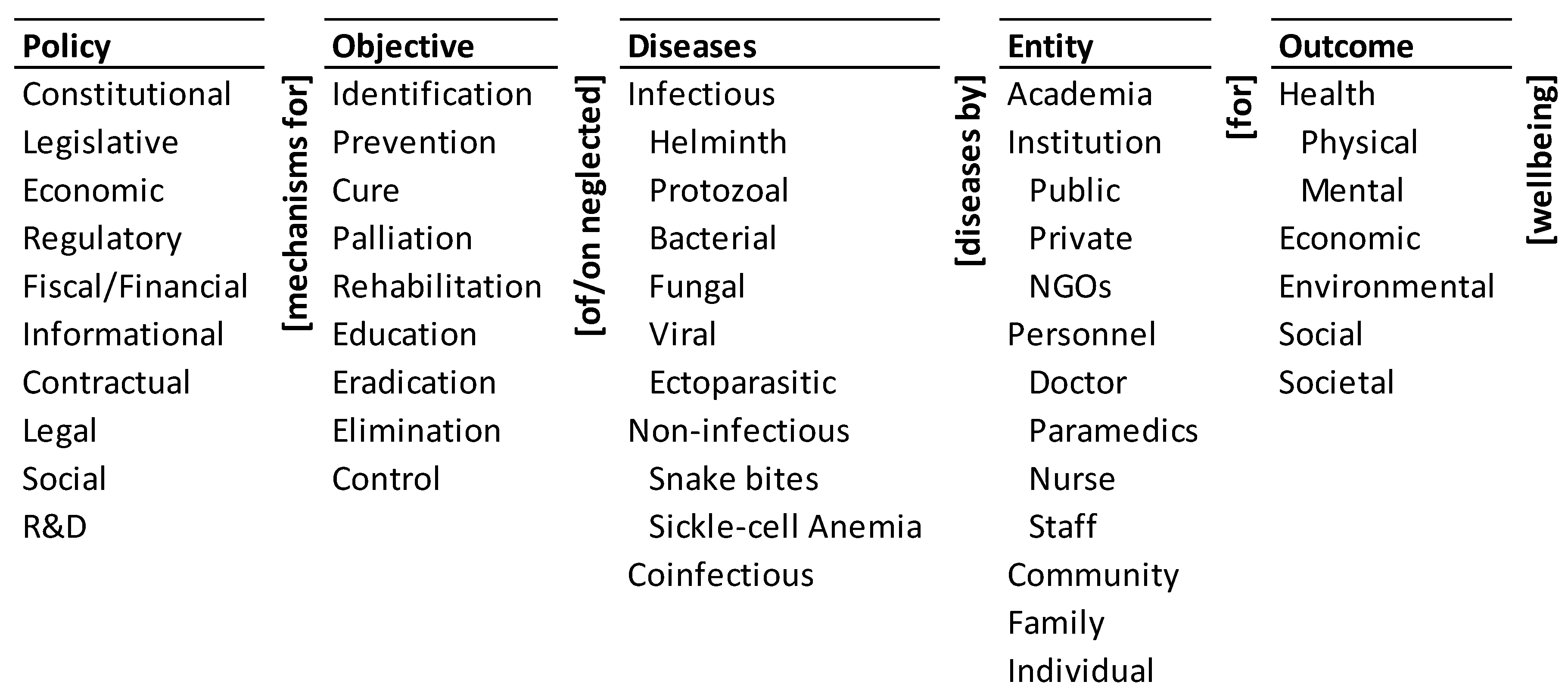

2. Materials and Methods – Ontology of Healthcare Policies to Eliminate Neglected Tropical Diseases (NTDs) in India

-

Fiscal/financial policy for the cure of infectious helminth diseases by public institutions for societal wellbeing.

- ○

- Funding for public health centers for identifying and curing infectious helminth diseases in a community. For example, financial resources of the government at various levels have not been adequate to provide sufficient budget support and personnel dedicated to prevention and control including human deworming in endemic areas [27].

- ○

- Economic incentives for academia for education on infectious helminth diseases in a community.

-

R&D policy for identification of co-infectious diseases by academia for physical wellbeing.

- ○

- Research agenda and grants for academic research on the prevalence of the effects of co-infectious diseases on physical wellbeing.

- ○

- Research agenda and grants for academic research on the assessment of the treatment of co-infectious diseases on physical wellbeing.

3. Results

State-of-the-Policies on Eliminating NTDs in India

- There are a few disease-specific policies/programs that are focused on the elimination of select NTDs primarily to improve the physical health and wellbeing of the target population. They give little attention to other objectives in managing the diseases and outcomes of management in the ontology.

- The policies/programs see the NTDs dominantly and narrowly as a community health problem to be addressed by personnel from public health institutions.

- There is a recognition of the very large scale and scope of NTDs in India. Yet, there is little reliable data on them except the selected few that have been targeted for elimination. There is no explicit informational policy to assist eliminating the NTDs.

- There are many healthcare policies that pay little or no explicit attention to NTDs but could be harnessed to address the challenge.

India’s Disease-Specific Policies and Programs

- Achieve and maintain elimination status of Leprosy by 2018, Kala-Azar by 2023 and Lymphatic Filariasis in endemic pockets by 2027.

- To achieve and maintain a cure rate of >85% in new sputum positive patients for TB and reduce the incidence of new cases, to reach elimination status by 2025.

- Establish regular tracking of the Disability Adjusted Life Years (DALY) Index as a measure of burden of disease and its trends by major categories by 2022.

India’s Community Health Approach

Scale and Scope of NTDs in India

India’s Healthcare Policies and NTDs

Summary of the State-of-Policies for Eliminating NTDs in India

State-of-the-Research on Policies for Eliminating NTDs in India

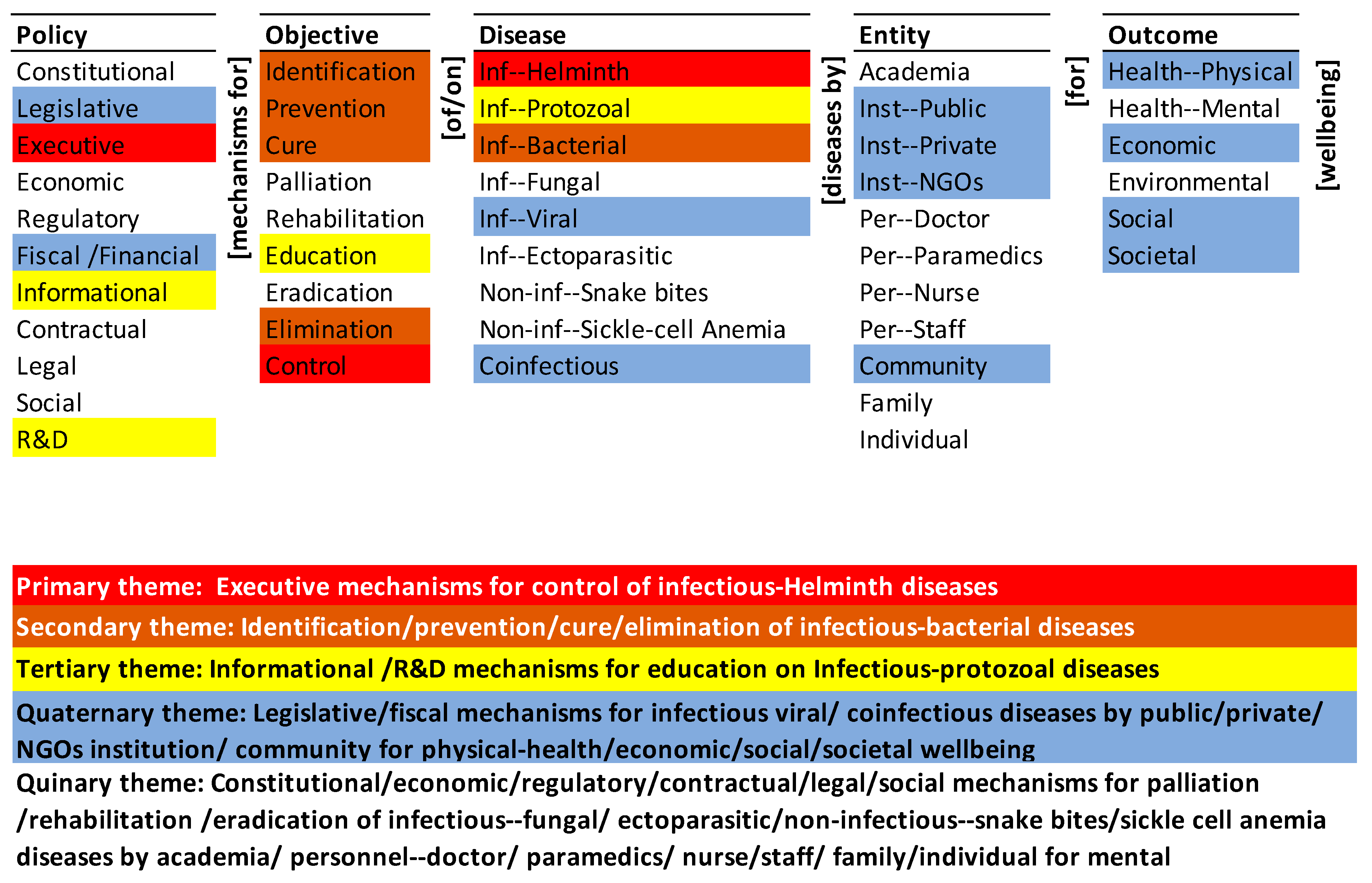

Monads Map

Themes Map

Summary of State-of-the-Research on Policies for Eliminating NTDs in India

4. Discussion – Policy Roadmap for Eliminating NTDs in India

Policies for Mapping the NTDs in India

- There is growing interest and commitment to the control of schistosomiasis and other so-called NTDs. Resources for control are inevitably limited, necessitating assessment methods that can rapidly and accurately identify and map high-risk communities so that interventions can be targeted in a spatially explicit and cost-effective manner. Research efforts should be undertaken to determine the optimal strategy of rapidly and simultaneously assessing several NTDs. An immediate question that arises is whether it is possible to develop an integrated rapid mapping approach [41] .

- A sound understanding of NTDs distribution and prevalence is an essential prerequisite for cost-effective control, with each national programme needing to be tailored to its specific context. Appropriate targeting of integrated MDA requires information on the geographical distribution of different NTDs, to identify areas that would benefit most from this approach. In the absence of such information, priority areas for control or elimination and the estimation of drug requirements is often based on expert opinion or out-of-date information [42].

- There is an urgent need for better surveillance and disease burden assessments for most of the NTDs, but especially for amebiasis, leptospirosis, and the major arbovirus infections, and for linking mass drug administration, vaccinations, integrated vector management, and improved surveillance together as part of overall efforts to strengthen health systems in the South Asian region [43].

- An ongoing census of the NTDs should form the baseline for the policies to eliminate NTDs in India. The census should be the basis for determining the scale and scope of the effort to eliminate a NTD and the synergy between the efforts to eliminate them. For instance, application of mobile-based management information system in rural and urban parts of Tanzania aided in control, accurate classification, diagnosis, and assessment of childhood illness [44].

- The census should describe, in depth and detail, the prevalence of NTDs in India. It should be the empirical basis for explaining the causes and consequences of the NTDs individually and in aggregate. It should be used to predict the trajectory of the NTDs and their effects. Last, it should be used to control their trajectory through continuous feedback and learning.

- Digital integration and use of technology are critical for devising sustainable surveillance response system for NTDs [45]. For instance, Brazil created LeishCare (mobile application which recorded patient information) to facilitate diagnosis, management, and timely treatment of patients with NTDs [46].

- India’s emerging digital infrastructure for healthcare must be used as the platform to manage the census of the NTDs in India.

- The census in conjunction with the medical, local, and personal knowledge of the entities in the ontology should determine the objectives regarding each NTD and the desired outcomes of fulfilling the objectives.

- The census should be the basis for local differentiation and national integration of the policies to eliminate NTDs.

- The census should be the basis of differentiation by diseases and integration across class of diseases. Digital public health paradigm in Africa, for instance, highlighted the importance of mHealth, eHealth, and electronic health records for improving health service access, service delivery, and monitoring outcomes in surveillance of infectious diseases [47].

- The above factors are critical for leveraging India’s National Digital Health Mission(NDHM) towards creating citizen centric holistic healthcare program[33]. In addition, India’s Health Data Management Policy, 2020 could be a potential catalyst for creation of digital health systems.

Policy Objectives for Managing the NTDs in India

- Snakebite envenoming requires establishment of dedicated rehabilitation programs, addressing both psychological and physical disability, will improve recovery of survivors, enabling more of them to return to useful, productive lives, therefore increasing economic productivity [48].

- Current NTDs control is not fully comprehensive, it contributes towards the preventative and curative strands of Universal Health Coverage, but the rehabilitative and palliative aspects of NTDs, and the intersection between NTDs and disability, are not well prioritized [49].

- First-line health services are for many people the first entry point into the health care system. Integration of the various care and service providers is important from an efficiency point of view. The provision of integrated care i.e., provision of curative and preventive care at first line is desirable for its effect on effectiveness [50].

- In this context the objectives for managing the NTDs in India must be clearly defined.

- Identification of many NTDs is difficult but must be the highest priority for all NTDs. It is essential for an accurate census. It must be a part of the agenda of all the entities in the ontology, with suitable educational support for them, and infrastructure (digital and non-digital) for them to record the same. Despite the high-rate prevalence of sickle cell anemia among the tribal population of India [51] it has been neglected in the themes map (Figure 3). Similarly, snake bites that are highly prevalent in India are not emphasized in the themes map. There is a need for systematic priority setting and targeted policies to ease the disease burden [52].

- Prevention of NTDs will be disease-dependent and may depend on one or a combination of entities. Its priority may be based on the scale and scope of prevalence, ease of prevention, and the impact on wellbeing. Preventive chemotherapy has been substantially used for treatment and control of NTDs. However, the need for improved diagnostics for NTDs are critical for devising treatment strategies across levels of control, interruption of transmission, elimination, and post-elimination surveillance [18].

- Prevention policies may be medical (for example, vaccination), personal (for example, habits), societal (for example, practices), or environmental (for example, water contamination). For instance, dracunculiasis eradication program mainly focuses on the preventive measures such as access to improved drinking-water sources, improved surveillance, encouraging self-reporting, and preventing infected individuals from swimming in drinking water sources, active case surveillance and vector control [53].

- Cure of NTDs will depend on the availability, accessibility, quality, and cost of healthcare available for a disease. Many NTDs do not have a cure. Policies on cure must address the design, development, and delivery of drugs to cure a disease. The priority of cure for an NTD should be based on the above factors.

- Palliation of the effects of an NTD may be an alternative if a cure is unavailable, or to manage the aftereffects of a cure. Its priority for a NTD will be determined by the efficacy of cure (if available), aftereffects of the cure, or the effects of the disease itself irrespective of the cure.

- Rehabilitation of a person that has suffered from a NTD, with or without it being cured, would depend on the residual effects of the disease and the treatment. The policy on rehabilitation must address the effects on the economic, social, and societal wellbeing of the individual, his/her family, and the community. The themes map (Figure 3) also reflects the least emphasis placed on palliation and rehabilitation which could be due to the absence of institutional mechanisms and follow -up actions [21].

- Education of the entities is central to all the other objectives, and all the outcomes. The policies on education must be comprehensive and contextual. It must be differentiated by the combinations of objective-disease-entity-outcome but integrated across all of them. Identification of and education on infectious NTDs [54,55] are critical.

- Eradication is the publicly stated objective for the NTDs but difficult to achieve. The policies regarding the earlier objectives are necessary but not sufficient for eradication. The cost of identifying and eradicating the last pocket of a neglected disease can be prohibitive. The policies must address identification based on the census of the diseases and the subsequent steps necessary for elimination. Devising policies with strategies for control of single diseases and multiple infectious diseases by involving medical personnel [56], community participation, government–community partnerships, private-public partnerships (PPPs), not-for-profit sector, civil societies, industries, and health services research[57] are critical for elimination of NTDs.

- Elimination policies may pose an even greater challenge than eradication. It will entail locating and eliminating the last genetic stores of the diseases.

- Control policies may be aimed at managing the occurrence of a NTD, its spread, and its recurrence. They may be aimed at the biological agents of a disease, the environmental enablers of a disease, or the entities responsible for managing the disease.

Policy Outcomes of Managing the NTDs in India

-

The priority of outcomes for an NTD or a class of NTDs must be differentiated by their geography and integrated across the geographies.

- ○

- The health (physical, mental), economic, environmental, social, and societal priorities for an NTD or class of NTDs must be geography specific. Contextual (intrinsic and extrinsic) determinants of NTDs [59] must be considered for comprehensive outcomes.

-

The priority of outcomes for an NTD or a class of NTDs must be aligned with the evidence about the disease, experience with managing the disease, and the objective of managing it.

- ○

- The health (physical, mental), economic, environmental, social, and societal priorities for an NTD or class of NTDs must be disease- or disease-class-specific.

-

The priority of outcomes for an NTD or a class of NTDs must be aligned with the priorities of the entities affected by it.

- ○

- The health (physical, mental), economic, environmental, social, and societal priorities for an NTD or class of NTDs must be specific to the corresponding individual, family, and community. For instance, educational, psychosocial, medical, and residential support were found to be major drivers for formulating social sustainability measures for people affected with leprosy [60].

Policies on Entities for Managing the NTDs in India

- All the entities must be empowered and enjoined to eliminate NTDs in India through their roles and responsibilities. The agencies of the entities must be differentiated and integrated accordingly.

- They should be proactive stakeholders and participants in conducting the census of the NTDs, formulating objectives for managing them, specifying the desired outcomes, and formulating the policies.

- They should be proactive generators and practitioners of both explicit and tacit knowledge about the NTDs, corresponding to their roles and responsibilities. The role of academia and public laboratories for engaging in drug innovation and repositioning is critical for India [64].

Policies for Managing the NTDs in India

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Trouiller, P.; Olliaro, P.; Torreele, E.; Orbinski, J.; Laing, R.; Ford, N. Drug Development for Neglected Diseases: A Deficient Market and a Public-Health Policy Failure. Lancet 2002, 359, 2188–2194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaudhuri, S. R&D for Development of New Drugs for Neglected Diseases in India. International Journal of Technology and Globalisation 2010, 5, 61–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mullin, R. Paying Attention to Neglected Diseases:The Drugs for Neglected Diseases Initiative Is Mobilizing Public/Private Partnerships. Chemical and Engineering News 2009, 87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Canning, D. Priority Setting and the ‘Neglected’ Tropical Diseases. Transactions of the Royal Society of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene 2006, 100, 499–504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Addiss, D. The 6th Meeting of the Global Alliance to Eliminate Lymphatic Filariasis: A Half-Time Review of Lymphatic Filariasis Elimination and Its Integration with the Control of Other Neglected Tropical Diseases. Parasites and Vectors 2010, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Allotey, P.; Reidpath, D.D.; Pokhrel, S. Social Sciences Research in Neglected Tropical Diseases: The Ongoing Neglect in the Neglected Tropical Diseases. Health Research Policy and Systems 2010, 8, 32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hotez, P.; Pecoul, B. “Manifesto” for Advancing the Control and Elimination of Neglected Tropical Diseases. PLoS Negl Trop Dis 2010, 4, e718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Narain, J.P.; Dash, A.P.; Parnell, B.; Bhattacharya, S.K.; Barua, S.; Bhatia, R.; Savioli, L. Elimination of Neglected Tropical Diseases in the South-East Asia Region of the World Health Organization. Bulletin of the World Health Organization 2010, 88, 206–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hotez, P. Enlarging the “Audacious Goal”: Elimination of the World’s High Prevalence Neglected Tropical Diseases. Vaccine 2011, 29, D104–D110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. Accelerating Work to Overcome the Global Impact of Neglected Tropical Diseases; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Karunamoorthi, K. Tungiasis: A Neglected Epidermal Parasitic Skin Disease of Marginalized Populations - A Call for Global Science and Policy. Parasitology Research 2013, 112, 3635–3643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pedrique, B.; Strub-Wourgaft, N.; Some, C.; Olliaro, P.; Trouiller, P.; Ford, N.; Pécoul, B.; Bradol, J.-H. The Drug and Vaccine Landscape for Neglected Diseases (2000–11): A Systematic Assessment. The Lancet Global Health 2013, 1, e371–e379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Global Health Progress. Action on Neglected Tropical Diseases in India; Global Health Progress, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Cashwell, A.; Tantri, A.; Schmidt, A.; Simon, G.; Mistry, N. BRICS in the Response to Neglected Tropical Diseases. Bull. World Health Organ. 2014, 92, 461–462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bai, J.; Li, W.; Huang, Y.-M.; Guo, Y. Bibliometric Study of Research and Development for Neglected Diseases in the BRICS. Infectious Diseases of Poverty 2016, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kant, L. Deleting the “Neglect” from Two Neglected Tropical Diseases in India. Indian J Med Res 2016, 143, 398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Michael, E.; Madon, S. Socio-Ecological Dynamics and Challenges to the Governance of Neglected Tropical Disease Control. Infect Dis Poverty 2017, 6, 35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peeling, R.W.; Boeras, D.I.; Nkengasong, J. Re-Imagining the Future of Diagnosis of Neglected Tropical Diseases. Computational and Structural Biotechnology Journal 2017, 15, 271–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hotez, P.; Damania, A. India’s Neglected Tropical Diseases. PLoS Negl Trop Dis 2018, 12, e0006038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saviano, M.; Barile, S.; Caputo, F.; Lettieri, M.; Zanda, S. From Rare to Neglected Diseases: A Sustainable and Inclusive Healthcare Perspective for Reframing the Orphan Drugs Issue. Sustainability 2019, 11, 1289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomas, Z.; Saha, G.K.; Gopakumar, K.M.; Ganguly, N.K. Can India Lead the Way in Neglected Diseases Innovation? BMJ 2019, 364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glenn, J.; Kamara, K.; Umar, Z.A.; Chahine, T.; Daulaire, N.; Bossert, T. Applied Systems Thinking: A Viable Approach to Identify Leverage Points for Accelerating Progress Towards Ending Neglected Tropical Diseases. Health Res Policy Sys 2020, 18, 56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ministry of Health and Family Welfare National Health Policy 2017 2017.

- Ministry of Health and Family Welfare National Policy for Treatment of Rare Diseases; MoHFW: India, 2018.

- Ministry of Science & Technology Science, Technology, and Innovation Policy 2020.

- Department of Pharmaceuticals (DoP) Draft National Pharamaceutical Policy. Pdf 2017.

- Tian, H.; Luo, J.; Zhong, B.; Huang, Y.; Xie, H.; Liu, L. Challenges in the Control of Soil-Transmitted Helminthiasis in Sichuan, Western China. Acta Tropica 2019, 199, 105132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- WHO WHO | Fact Sheets Relating to NTD. Available online: http://www.who.int/neglected_diseases/mediacentre/factsheet/en/ (accessed on 11 March 2020).

- Friedrich, M.J. WHO Declares India Free of Yaws and Maternal and Neonatal Tetanus. JAMA 2016, 316, 1141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ministry of Health and Family Welfare India’s Roadmap to Eliminate Lymphatic Filariasis (LF). Available online: https://pib.gov.in/pib.gov.in/Pressreleaseshare.aspx?PRID=1890935 (accessed on 16 June 2023).

- Ministry of Health and Family Welfare Annual Report 2020-21; Department of Health and Welfare: India, 2020.

- Tripathi, B.; Roy, N.; Dhingra, N. Introduction of Triple-Drug Therapy for Accelerating Lymphatic Filariasis Elimination in India: Lessons Learned. The American Journal of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene 2022, 106, 29–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- National Health Authority National Digital Health Mission 2020.

- Food and Drug Administration New Drugs at FDA: CDER’s New Molecular Entities and New Therapeutic Biological Products. Available online: https://www.fda.gov/drugs/development-approval-process-drugs/new-drugs-fda-cders-new-molecular-entities-and-new-therapeutic-biological-products (accessed on 17 June 2023).

- Department of Biotechnology National Biotechnology Development Strategy [2021-2025]; Ministry of Sciecne and Technology, GOI: India, 2020.

- Ministry of Commerce and Industry National National Intellectual Property Rights Policy. Available online: https://dpiit.gov.in/policies-rules-and-acts/policies/national-ipr-policy (accessed on 17 June 2023).

- Munteanu, C.; Schwartz, B. The Relationship between Nutrition and the Immune System. Frontiers in Nutrition 2022, 9. [Google Scholar]

- Ministry of Consumer Affairs, Food and Public Distribution National Food Security Act (NFSA). Available online: https://dfpd.gov.in/nfsa.htm (accessed on 17 June 2023).

- United Nations. Sustainable Development Goals- India; United Nations, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Remme, J.H.F.; Blas, E.; Chitsulo, L.; Desjeux, P.M.P.; Engers, H.D.; Kanyok, T.P.; Kayondo, J.F.K.; Kioy, D.W.; Kumaraswami, V.; Lazdins, J.K.; et al. Strategic Emphases for Tropical Diseases Research: A TDR Perspective. 2002, 6.

- Brooker, S.; Kabatereine, N.B.; Gyapong, J.O.; Stothard, J.R.; Utzinger, J. Rapid Mapping of Schistosomiasis and Other Neglected Tropical Diseases in the Context of Integrated Control Programmes in Africa. Parasitology 2009, 136, 1707–1718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sturrock, H.J.W.; Picon, D.; Sabasio, A.; Oguttu, D.; Robinson, E.; Lado, M.; Rumunu, J.; Brooker, S.; Kolaczinski, J.H. Integrated Mapping of Neglected Tropical Diseases: Epidemiological Findings and Control Implications for Northern Bahr-El-Ghazal State, Southern Sudan. PLOS Neglected Tropical Diseases 2009, 3, e537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lobo, D.A.; Velayudhan, R.; Chatterjee, P.; Kohli, H.; Hotez, P.J. The Neglected Tropical Diseases of India and South Asia: Review of Their Prevalence, Distribution, and Control or Elimination. PLOS Neglected Tropical Diseases 2011, 5, e1222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitchell, M.; Hedt-Gauthier, B.L.; Msellemu, D.; Nkaka, M.; Lesh, N. Using Electronic Technology to Improve Clinical Care - Results from a before-after Cluster Trial to Evaluate Assessment and Classification of Sick Children According to Integrated Management of Childhood Illness (IMCI) Protocol in Tanzania. BMC Med Inform Decis Mak 2013, 13, 95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoshioka, K.; Tercero, D.; Perez, B.; Nakamura, J.; Perez, L. Implementing a Vector Surveillance-Response System for Chagas Disease Control: A 4-Year Field Trial in Nicaragua. Infectious Diseases of Poverty 2017, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Da Silva, P.E.F.; Dos Santos Fonseca Junior, G.; Ambrozio, R.B.; Tiburcio, M.G.S.; Machado, G.B.; De Carvalho, S.F.G.; De Oliveira, E.J.; De Almeida Silva Teixeira, L.; Jorge, D.C. Development of a Software for Mobile Devices Designed to Help with the Management of Individuals with Neglected Tropical Diseases. Res. Biomed. Eng. 2021, 37, 881–881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tambo, E.; Xia, S.; Feng, X.-Y.; Xiao -Nong, Z. Digital Surveillance and Communication Strategies to Infectious Diseases of Poverty Control and Elimination in Africa. Infectious Diseases and Epidemiology 2018, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, D.J.; Faiz, M.A.; Abela-Ridder, B.; Ainsworth, S.; Bulfone, T.C.; Nickerson, A.D.; Habib, A.G.; Junghanss, T.; Fan, H.W.; Turner, M.; et al. Strategy for a Globally Coordinated Response to a Priority Neglected Tropical Disease: Snakebite Envenoming. PLOS Neglected Tropical Diseases 2019, 13, e0007059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamill, L.C.; Haslam, D.; Abrahamsson, S.; Hill, B.; Dixon, R.; Burgess, H.; Jensen, K.; D’Souza, S.; Schmidt, E.; Downs, P. People Are Neglected, Not Diseases: The Relationship between Disability and Neglected Tropical Diseases. Transactions of The Royal Society of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene 2019, 113, 829–834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marchal, B.; Van Dormael, M.; Pirard, M.; Cavalli, A.; Kegels, G.; Polman, K. Neglected Tropical Disease (NTD) Control in Health Systems: The Interface between Programmes and General Health Services. Acta Tropica 2011, 120, S177–S185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colah, R.B.; Mukherjee, M.B.; Martin, S.; Ghosh, K. Sickle Cell Disease in Tribal Populations in India. INDIAN J MED RES 2015, 7. [Google Scholar]

- Luo, C.; Ma, Y.; Liu, Y.; Lv, Q.; Yin, F. The Burden of Childhood Hand-Foot-Mouth Disease Morbidity Attributable to Relative Humidity: A Multicity Study in the Sichuan Basin, China. Sci Rep 2020, 10, 19394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Biswas, S.; Subramanian, A.; ELMojtaba, I.M.; Chattopadhyay, J.; Sarkar, R.R. Optimal Combinations of Control Strategies and Cost-Effective Analysis for Visceral Leishmaniasis Disease Transmission. PLoS ONE 2017, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garapati, P.; Pal, B.; Siddiqui, N.A.; Bimal, S.; Das, P.; Murti, K.; Pandey, K. Knowledge, Stigma, Health Seeking Behaviour and Its Determinants among Patients with Post Kalaazar Dermal Leishmaniasis, Bihar, India. PLoS ONE 2018, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mangalgi, S.; Sajjan, A.G.; Mohite, S.T.; Kakade, S.V. Serological, Clinical, and Epidemiological Profile of Human Brucellosis in Rural India. Indian Journal of Community Medicine 2015, 40, 163–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gautam, C.; Bhanwra, S. Neglected Tropical Diseases: Need for Sensitization of Medical Students. Indian Journal of Pharmacology 2008, 40, 132–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manderson, L.; Aagaard-Hansen, J.; Allotey, P.; Gyapong, M.; Sommerfeld, J. Social Research on Neglected Diseases of Poverty: Continuing and Emerging Themes. PLoS Negl Trop Dis 2009, 3, e332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bangert, M.; Molyneux, D.H.; Lindsay, S.W.; Fitzpatrick, C.; Engels, D. The Cross-Cutting Contribution of the End of Neglected Tropical Diseases to the Sustainable Development Goals. Infectious Diseases of Poverty 2017, 6, 73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ehrenberg, J.P.; Ault, S.K. Neglected Diseases of Neglected Populations: Thinking to Reshape the Determinants of Health in Latin America and the Caribbean. BMC Public Health 2005, 5, 119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jung, S.H.; Han, H.W.; Koh, H.; Yu, S.-Y.; Nawa, N.; Morita, A.; Ong, K.I.C.; Jimba, M.; Oh, J. Patients Help Other Patients: Qualitative Study on a Longstanding Community Cooperative to Tackle Leprosy in India. PLoS neglected tropical diseases 2020, 14, e0008016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ehrenberg, J.P.; Utzinger, J.; Fontes, G.; da Rocha, E.M.M.; Ehrenberg, N.; Zhou, X.-N.; Steinmann, P. Efforts to Mitigate the Economic Impact of the COVID-19 Pandemic: Potential Entry Points for Neglected Tropical Diseases. Infectious Diseases of Poverty 2021, 10, 4–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, N.; Amon, J.J. Addressing Inequity. Health Hum Rights 2018, 20, 11–25. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Mitjà, O.; Marks, M.; Bertran, L.; Kollie, K.; Argaw, D.; Fahal, A.H.; Fitzpatrick, C.; Fuller, L.C.; Izquierdo, B.G.; Hay, R.; et al. Integrated Control and Management of Neglected Tropical Skin Diseases. PLOS Neglected Tropical Diseases 2017, 11, e0005136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Padhy, B.M.; Gupta, Y.K. Drug Repositioning: Re-Investigating Existing Drugs for New Therapeutic Indications. Journal of Postgraduate Medicine 2011, 57, 153–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).