Since the advent of high-throughput next-generation sequencing (NGS) technologies [

1] and with the recent surge of long-read, single-cell and spatial RNA sequencing [

2], biomedical research has become intensely data-driven [

3,

4,

5]. Indeed, one of the major challenges of the post-genome era has been to store the large data volumes produced by these technologies. Cloud computing providers, such as Amazon Web Services (AWS) [

6], play an essential role in addressing this challenge by offering leading security standards, cost-effective data storage, easy data sharing, and real-time access to resources and applications [

7,

8,

9].

Nevertheless, cloud storage services require a stable network connection to complete a successful data transfer [

10]. Network congestion, for instance, can cause packet loss during data transmission, producing unintended changes to the original data, which could result in a corrupted final version of the transferred file. To identify these faulty data transfers in real-time, Amazon Simple Storage Service (Amazon S3) permits using checksum values through the AWS Command Line Interface (AWS CLI) tool. This approach consists of locally calculating the Content-MD5 or entity tag (ETag) number associated with the contents of a given file, and then including this checksum value within the AWS CLI command used to upload the file to an Amazon S3 bucket. If the checksum number assigned by Amazon S3 is identical to the local checksum calculated by the user, then both local and remote file versions will be the same and therefore the file's integrity will be proven.

However, this method has some disadvantages. First, the choice of which checksum number to calculate, either a Content-MD5 [

11] or ETag number, will depend on the characteristics of the file, such as its size or the server-side encryption selected. This requirement obliges the user to evaluate the characteristics of each file independently before deciding which checksum value to calculate. Secondly, the checksum number needs to be included within the AWS CLI command used to upload the file to an Amazon S3 bucket, thus requiring the user to upload each file individually. Finally, this process needs to be repeated for each individual file transferred to Amazon S3, which can exponentially increase the time required to complete a data transfer as the number of files forming the dataset increases.

To overcome these challenges, we have developed aws-s3-integrity-check, a bash tool to verify the integrity of a dataset uploaded to Amazon S3. The aws-s3-integrity-check tool offers a user-friendly and easy-to-use front-end that requires one single command with a maximum of three parameters to perform the complete integrity verification of all files contained within a given Amazon S3 bucket, regardless of their file size and extension. In addition, the aws-s3-integrity-check tool provides three unique features: (i) it is used during post-data upload, which provides the user with the freedom to transfer data in batches to Amazon S3 without having to manually calculate an individual checksum value for each individual file; (ii) to complete the integrity verification of all files contained within a given dataset, it only requires the submission of one single query to the Amazon S3 application programming interface (API), thus it does not congest the network; and (iii) it informs the user of the result from each checksum comparison, providing per-file detailed information. Considering the latter, aws-s3-integrity-check produces 4 different types of outputs: (i) the user does not have read access to the indicated Amazon S3 bucket and so it produces an error and stops the tool execution; (ii) a given file from the provided local folder does not exist within the indicated Amazon S3 bucket, thus it produces a warning message and continues the tool execution; (iii) the local file exists within the remote bucket but its local and remote checksum values do not match, which produces a warning message, and continuing the tool execution; (iv) the local file exists within the remote bucket and its local and remote checksum values match, hence the integrity of the file is proven. All outputs are shown on-screen and stored locally in a log file.

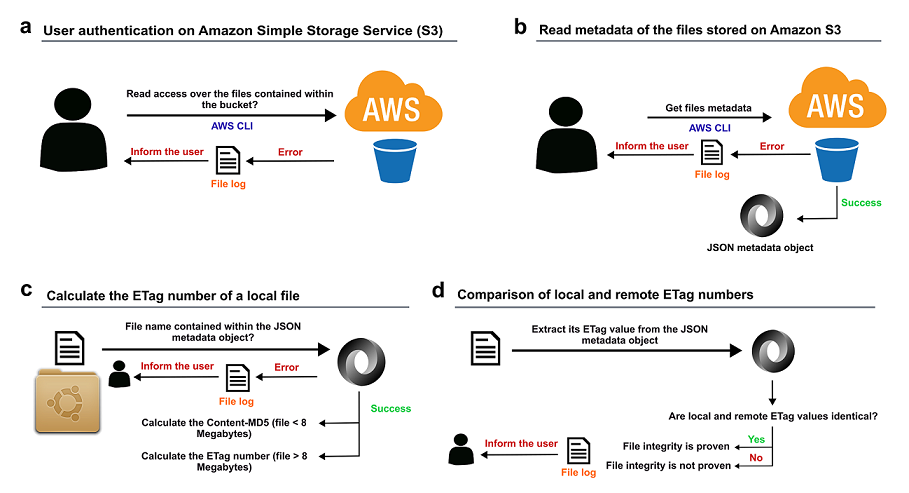

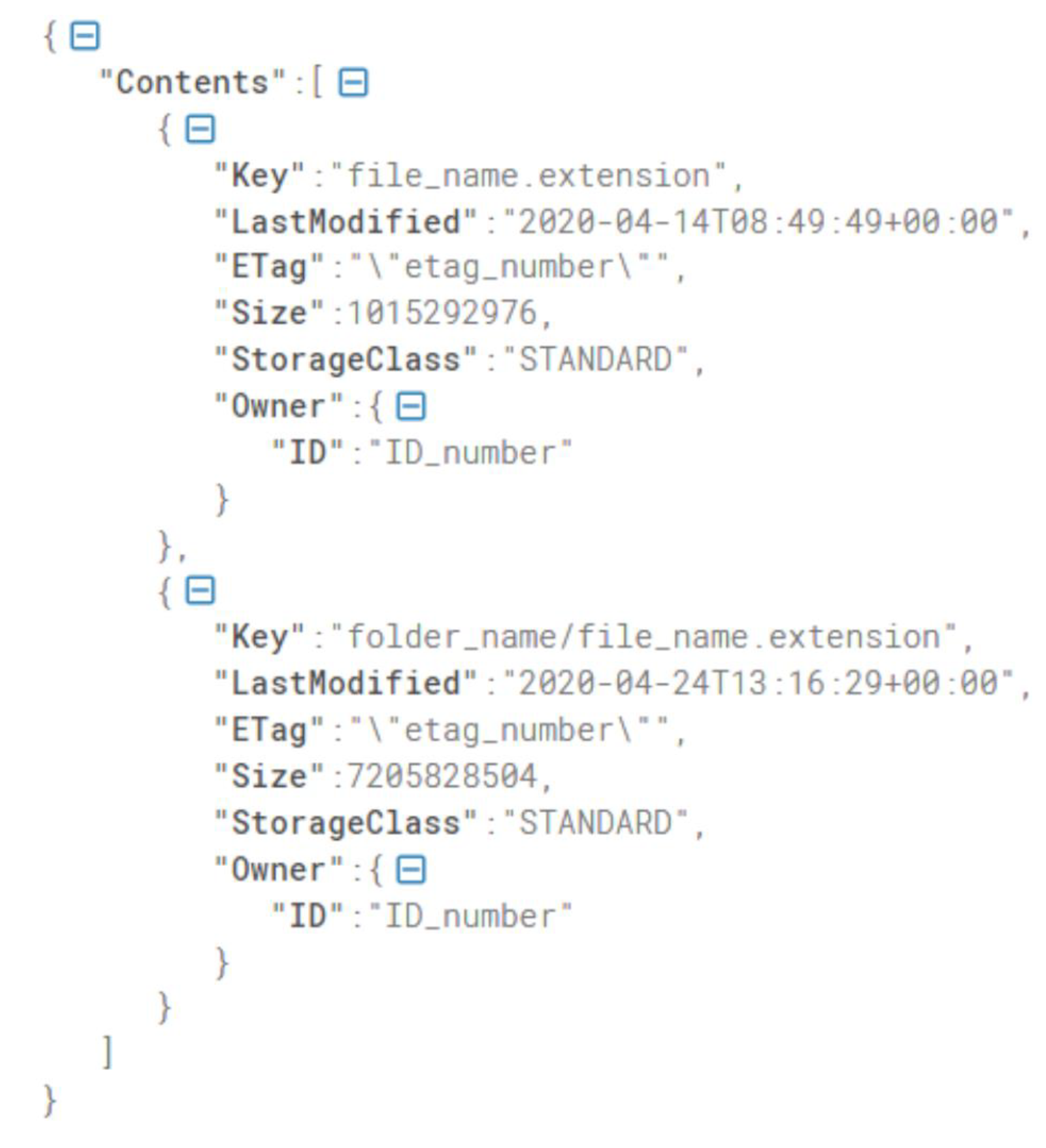

Our purpose is to enable the automatic integrity verification of a set of files transferred to Amazon S3, regardless of their file size and extension. To succeed in this mission, we have created the aws-s3-integrity-check tool, which: i) reads the metadata of the totality of files stored within a given Amazon S3 bucket by querying the Amazon S3 API only once; ii) calculates the checksum value associated with every file contained within a local folder by using the same algorithm applied by Amazon S3; and iv) compares local and remote checksum values, informing the user if both numbers are identical and, consequently, if the remote version of the S3 object coincides to its local version.

To identify different versions of a file, Amazon S3 uses ETag numbers, which remain unalterable unless the file object suffers any change to its contents. Amazon S3 uses different algorithms to calculate an ETag number, which depends on the characteristics of the transferred file. More specifically, an ETag number is an MD5 digest of the object data when the file is: i) uploaded through the AWS Management Console or using the PUT Object, POST Object, or Copy operation; ii) is plaintext; or iii) is encrypted with Amazon S3 managed keys (SSE-S3). On the contrary, if the object has been server-side encrypted with customer-provided keys (SSE-C) or with AWS Key Management Service (AWS KMS) keys (SSE-KMS) the ETag number assigned will not be an MD5 digest. Finally, if the object has been created as part of a

Multipart Upload or

Party copy operation, the ETag number assigned will not be an MD5 digest, regardless of the method of encryption [

12]. When an object is larger than a specific file size, it will be automatically uploaded using multipart uploads and the ETag number assigned will be a combination of the different MD5 digest numbers assigned to smaller sections of its data.

In order to match the default values published within the guidelines corresponding to the AWS CLI S3 transfer commands [

13], the

aws-s3-integrity-check tool establishes in 8 MB the default multipart chunk size and the maximum file size threshold for calculation of the ETag number. To automatise the calculation of the ETag value in cases where the file size exceeds the default value of 8 MB, the

aws-s3-integrity-check tool uses the

s3md5 bash script (version 1.2, [

14]). The s3md5 bash script consists of several steps. Using the same algorithm that Amazon S3 applies, the s3md5 script splits the files that are larger than 8 MB into smaller parts of that same size and calculates the MD5 digest corresponding to each chunk. Secondly, the s3md5 script concatenates all the bytes from the individual MD5 digest numbers produced, creating a single value and converting it into binary format before calculating its final MD5 digest number. Thirdly, it appends a dash with the total number of parts calculated to the MD5 hash. The resulting number produced represents the final ETag value assigned to the file.

Figure 1 shows a complete overview of the approach followed (please, refer to the Methods section for more details).

To test the

aws-s3-integrity-check tool, we used 1,045 files stored across 4 independent Amazon S3 buckets located within a private AWS account in the London region (eu-west-2). The rationale behind the inclusion of these different 4 datasets during the testing phase of the

aws-s3-integrity-check tool is the variability of their project nature, the different file types and file sizes they contain, and their availability within two different public repositories, the European Genome-phenome Archive (EGA) [

15] and the data repository GigaDB [

16].

These four datasets occupied ~935 GB of cloud storage space and contained files ranging between 5 Bytes and 10 GB that were individually uploaded to AWS using the AWS CLI

sync command (version 1 [

17]). No specific server-side encryption was indicated while using the

sync command. In addition, all the configuration values available for the

aws s3 sync command, which include

max_concurrent_requests, max_queue_size, multipart_threshold, multipart_chunksize and max_bandwidth, were not changed and used with default values. Details of the four datasets tested are shown in

Table 1.

Using the

aws-s3-integrity-check tool, we successfully verified the data integrity of multiple file types, which are detailed in

Table 2.

We performed two-sided tests. We used the aws-s3-integrity-check tool to 1) test the integrity of three datasets uploaded to Amazon S3, and 2) test the integrity of one dataset downloaded from Amazon S3.

To test the former approach, we downloaded three publicly available datasets corresponding to one EGA project and two GigaDB studies. Firstly, we requested access to the dataset with EGA accession number EGAS00001006380 and, after obtaining access approval, we downloaded the totality of its files to a local folder. Secondly, we downloaded from the GigaDB FTP server the files corresponding to the studies DOI:10.5524/102374 and DOI:10.5524/102379, by using the following Linux commands:

$ wget -r ftp://anonymous@ftp.cngb.org/pub/gigadb/pub/10.5524/102001_103000/102374/*

$ wget -r ftp://anonymous@ftp.cngb.org/pub/gigadb/pub/10.5524/102001_103000/102379/*

These three datasets (i.e. one EGA dataset and two GigaDB projects) were then uploaded to three different Amazon S3 buckets, which were respectively named

“rnaseq-d” (EGAS00001006380)

, “mass-spectrometry-imaging” (DOI: 10.5524/102374), and

“tf-prioritizer” (DOI: 10.5524/102379) (see

Table 1). In all three cases, the data was uploaded to Amazon S3 by using the following

aws s3 command:

$ aws s3 sync --profile aws_profile path_local_folder/ s3://bucket_name/

To verify that the data contents of the remote S3 objects were identical to the contents of their local version, we then run the aws-s3-integrity-check tool by using the following command structure:

$ bash aws_check_integrity.sh [-l|--local <path_local_folder>] [-b|--bucket <s3_bucket_name>] [-p|--profile <aws_profile>]

Next, we used the

aws-s3-integrity-check tool to test the integrity of a local dataset downloaded from an S3 bucket. In this case, we used data from the EGA project with accession number EGAS00001003065. Once we had obtained access approval to the EGAS00001003065 repository, we downloaded all its files to a local folder. We then uploaded this local dataset to an S3 bucket named

“ukbec-unaligned-fastq” (see

Table 1). Once the data transfer to Amazon S3 had finished, we downloaded these remote files to a local folder by using the S3 command

sync as follows:

$ aws s3 sync --profile aws_profile s3://ukbec-unaligned-fastq/ path_local_folder/.

To test that the local version of the downloaded files had identical data contents as their remote S3 version, we run the aws-s3-integrity-check tool, employing the following command synopsis:

$ bash aws_check_integrity.sh [-l|--local <path_local_folder>] [-b|--bucket <ukbec-unaligned-fastq>] [-p|--profile <aws_profile>].

Finally, we aimed to test whether the aws-s3-integrity-check tool was able to detect any differences between a given local file that had been manually modified and its S3 remote version and inform the user accordingly. With this in mind, we edited the file “readme_102374.txt” from the dataset DOI:10.5524/102374 and changed its data contents by running the following command:

$ (echo THIS FILE HAS BEEN LOCALLY MODIFIED; cat readme_102374.txt) > readme_102374.tmp && mv readme_102374.t{mp,xt}

We then run the aws-s3-integrity-check tool employing the following command synopsis:

$ bash aws_check_integrity.sh [-l|--local <path_local_folder>] [-b|--bucket <mass-spectrometry-imaging>] [-p|--profile <aws_profile>].

As expected, the

aws-s3-integrity-check tool was able to detect the differences in data contents between the local and S3 remote version of the

“readme_102374.txt” file by producing a different checksum number from the one originally provided by Amazon S3. The error message produced corresponded to

“ERROR: local and remote ETag numbers for the file 'readme_102374.txt' do not match.”. The output of this comparison can be checked on the log file

“mass-spectrometry-imaging.S3_integrity_log.2023.07.31-22.59.01.txt” (see

Table 1).

The aws-s3-integrity-check tool also demonstrated minimal use of computer resources by displaying an average CPU usage of only 2% across all tests performed.

The four datasets tested were stored across four Amazon S3 buckets located within the AWS London region (eu-west-2) (see

Table 1). All four S3 buckets had the file versioning enabled and a server-side SSE-S3 encryption key type selected.

The aws-s3-integrity-check tool is expected to work for files that have been uploaded to Amazon S3 by following these two uploading criteria:

Uploaded by command-line using any of the aws s3 transfer commands, which include the cp, sync, mv, and rm commands.

-

Using the default values established for the following aws s3 configuration parameters:

max_concurrent_requests - default: 10.

max_queue_size - default: 1000.

multipart_threshold - default: 8 (MB).

multipart_chunksize - default: 8 (MB).

max_bandwidth - default: none.

use_accelerate_endpoint - default: false.

use_dualstack_endpoint - default: false.

addressing_style - default: auto.

payload_signing_enabled - default: false.

The

aws-s3-integrity-check tool is expected to work across Linux distributions. With this in mind, testing was performed using an Ubuntu server 16.04 LTS with kernel version 4.4.0-210-generic and an Ubuntu server 22.04.1 LTS (Jammy Jellyfish) with kernel version 5.15.0-56-generic. To remove the OS barrier, the Dockerized version of the

aws-s3-integrity-check tool is available at

https://hub.docker.com/r/soniaruiz/aws-s3-integrity-check.

The source code corresponding to the

aws-s3-integrity-check tool is hosted on GitHub (

https://github.com/SoniaRuiz/aws-s3-integrity-check) and, from this repository, it is possible to create new issues and submit tested pull requests for review. Issues have been configured to choose between the “Bug report” and ”Feature request” categories, which ultimately facilitates the creation and submission of new triaged and labelled entries.

The

aws-s3-integrity-check tool relies on the

s3md5 bash script (version 1.2, [

14]) to function. To ensure the availability and maintenance of the s3md5 bash script to the users of the

aws-s3-integrity-check tool, the source s3md5 GitHub repository (

https://github.com/antespi/s3md5) has been forked and made available at

https://github.com/SoniaRuiz/s3md5. Any potential issues emerging on the s3md5 bash script that may affect the core function of the

aws-s3-integrity-check tool can be submitted via the Issues tab of the forked s3md5 repository. Any new issue will be triaged, maintained and fixed on the forked GitHub repository within the “Bug Report” category, before being submitted via a pull request to the project owner.

Here, we have presented a novel approach for optimising the integrity verification of a dataset transferred to/from the Amazon S3 cloud storage service. However, there are a few caveats to this strategy. First, the user has to have read/write access to an Amazon S3 bucket. Second, this tool requires that the user selects JavaScript Object Notation (JSON) as the preferred text-output format during the AWS authentication process. Third, the aws-s3-integrity-check tool is only expected to work for files that have been uploaded to Amazon S3 by using any of the aws s3 transfer commands available (i.e. cp, sync, mv, and rm) with all the configuration parameters set to default values, which include multipart_threshold and multipart_chunksize; it is essential that the file size threshold for the file multipart upload and the default multipart chunk size remain at the default 8 MB values. Fourth, the bash version of this tool is only expected to work across Linux distributions. Finally, the Dockerized version of this tool requires three extra arguments to mount three local folders required by the Docker image, which may increase the complexity of using this tool.

The main script is formed by a set of sequential steps whose methods are detailed below.

To parse command options and arguments sent to the

aws-s3-integrity-check bash tool, we used the Linux built-in function

getops [

24]. The arguments sent corresponded to (i)

[-l|--local <path_local_folder>], to indicate the path to the local folder containing the files to be tested; (ii)

[-b|--bucket <S3_bucket_name>], to indicate the name of the Amazon S3 bucket containing the remote version of the local files; (iii)

[-p|--profile <aws_profile>], to indicate the user’s AWS profile in case the authentication on AWS was done using single sign-on (SSO); and (iv)

[-h|--help], to show further information about the usage of the tool.

To test whether the user had read access over the files stored within the Amazon S3 bucket indicated through the argument

[-b|--bucket <S3_bucket_name>], we used the AWS CLI command

aws s3 ls (version 2, [

25]). In case this query returned an error, the tool informed the user and provided some suggestions about different AWS authentication options. For the correct performance of this tool, it is required that the user selects JavaScript Object Notation (JSON) as the preferred text-output format during the AWS authentication process.

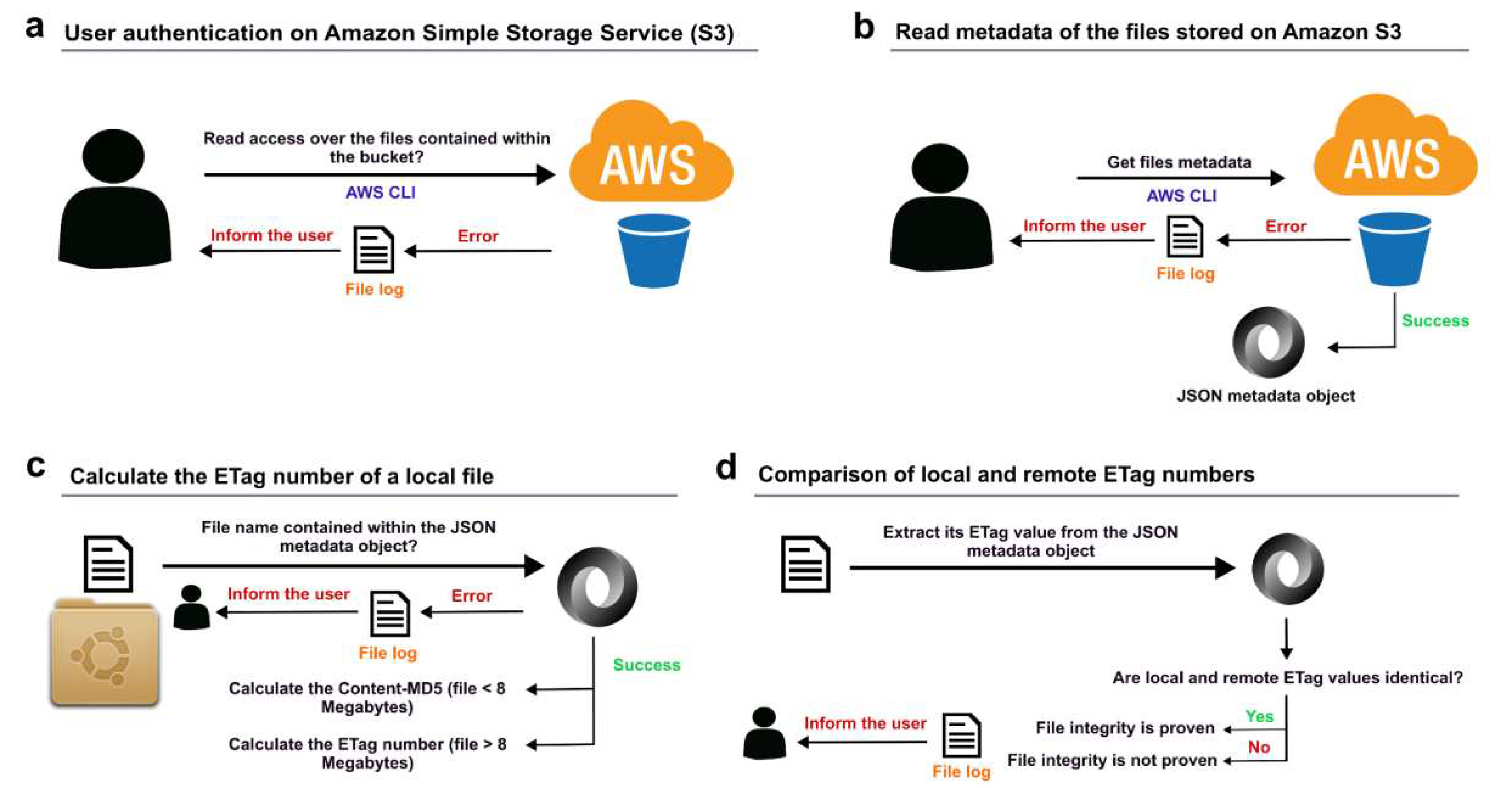

To obtain the ETag number assigned to the totality of the files contained within the indicated Amazon S3 bucket, we used the AWS CLI command

list-objects (version 1, [

26]) as follows:

$ aws s3api list-objects --bucket "$bucket_name" --profile "$aws_profile"’

In this way, we reduced to one the number of queries performed to the AWS S3 API, known as

s3api, which considerably reduced the overall network overload. The output from the function

list-objects corresponded to a JSON object (

Figure 2).

In case the local path indicated through the parameter

[-l|--local <path_local_folder>] existed, was a directory, and the user had read access over its contents, the tool looped through its files. For each file within the folder, the

aws-s3-integrity-check bash tool checked whether the filename was among the entries retrieved within the JSON metadata object, indicated within the

“Key” field. If that was the case, it meant that the local file existed on the indicated remote Amazon S3 bucket and we could proceed to calculate its checksum value. Before calculating the checksum value of the file, the tool evaluated the data content of the file. If it was smaller than 8 MB, the tool calculated its Content-MD5 value by using the function

md5sum [27, 28] (version 8.25, [

29]). On the contrary, if the file was larger than 8 MB, it used the function

s3md5 (version 1.2, [

14]) using the command

“s3md5 8 path_local_file”.

To obtain the ETag value that Amazon S3 assigned to the tested file at the moment it was stored on the remote bucket, we filtered the JSON metadata object by using the fields

“ETag” and

“Key” and the function

select (jq library, version jq-1.5-1-a5b5cbe, [

30]). We then compared the local and remote checksum values and, if both numbers were identical, the integrity of the local file was proven. We repeated this process for each of the files contained within the local folder

[-l|--local <path_local_folder>].

To inform the user about the outcome of each step, we used on-screen messages and logged this information within a local file in a .txt format. Log files are stored within a local folder named

“log/” and located in the same path in which the main bash script

aws-check-integrity.sh was located. In case a local

“log/” folder did not exist, the script created it.

Figure 1 shows a complete overview of the approach followed.

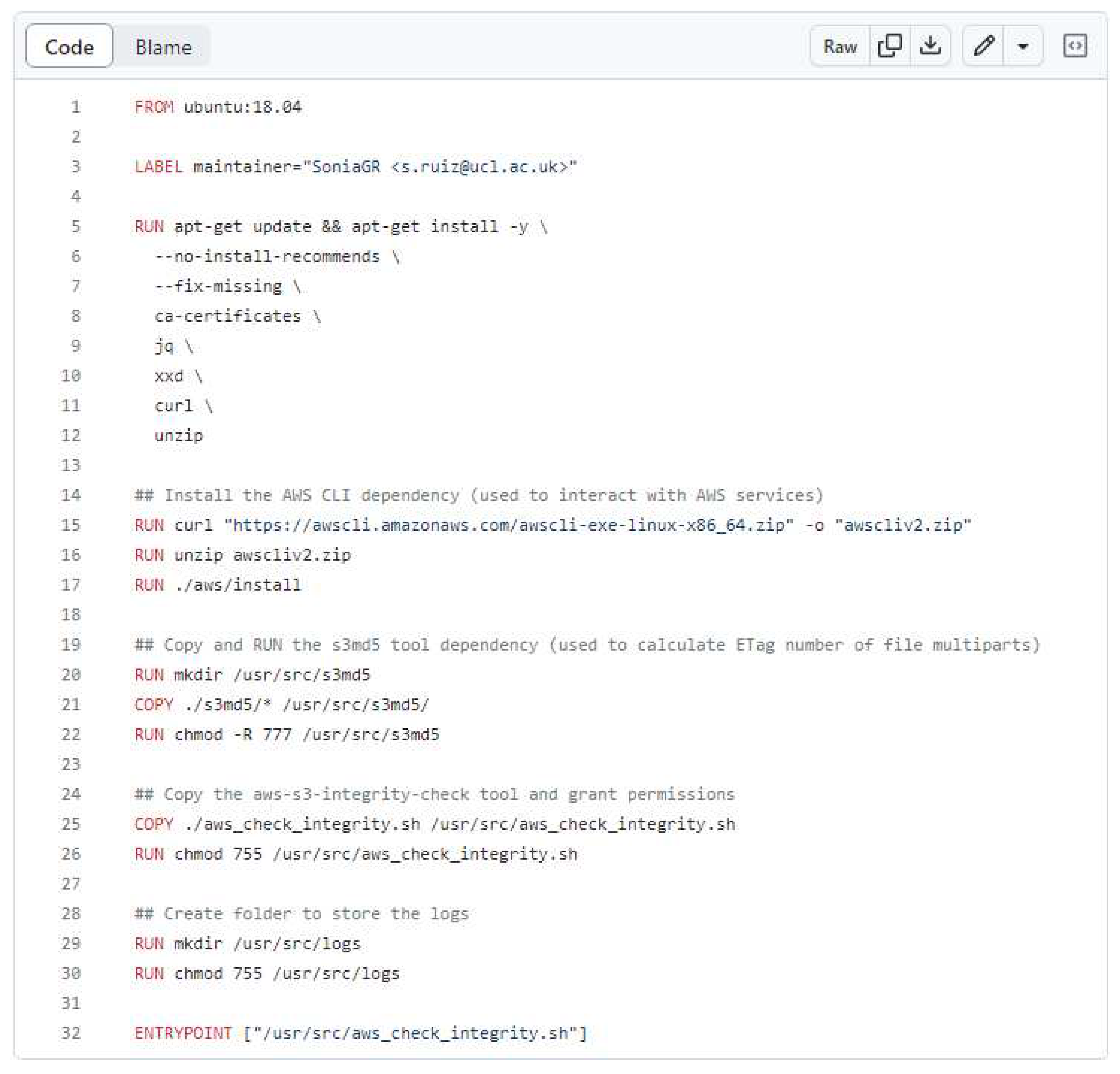

To create the Dockerized version of the

aws-s3-integrity-check tool (Docker, version 18.09.7, build 2d0083d, [

31]), we used the Dockerfile shown in

Figure 3.

The Dockerized version of the aws-s3-integrity-check tool requires the user to indicate the following additional arguments within the docker run command:

-

[-v <path_local_folder>:<path_local_folder>]. Required argument. This argument requires replacing the strings [<path_local_folder>:<path_local_folder>] with the absolute path to the local folder containing the local version of the remote S3 files to be tested. This argument is used to mount the local folder as a local volume to the Docker image, allowing Docker to have read access over the local files to be tested. Important: the local folder should be referenced by using the absolute path.

- ○

Example: -v /data/nucCyt:/data/nucCyt

[-v "$PWD/logs/:/usr/src/logs"]. Required argument. This argument should not be changed and, therefore, it should be used as it is shown. It represents the path to the local logs folder and is used to mount the local logs folder as a local volume to the Docker image. It allows Docker to record the outputs produced during the tool execution.

[-v "$HOME/.aws:/root/.aws:ro"]. Required argument. This argument should not be changed and, therefore, it should be used as it is shown. It represents the path to the local folder containing the information about the user authentication on AWS. This parameter is used to mount the local AWS credential directory as a read-only volume to the Docker image, allowing Docker to have read access to the authentication information of the user on AWS.

Below, there are two examples that show how to run the Dockerized version of the aws-s3-integrity-check tool. Each example differs on the method used by the user to authenticate on AWS:

Example #1 (if the user has authenticated on Amazon s3 using SSO):

Example #2 (if the user has authenticated on Amazon s3 using an IAM role (KEY + SECRET)):

Project name: aws-s3-integrity-check: an open-source bash tool to verify the integrity of a dataset stored on Amazon S3

Operating system: Ubuntu 16.04.7 LTS (Xenial Xerus), Ubuntu 18.04.6 LTS (Bionic Beaver), Ubuntu server 22.04.1 LTS (Jammy Jellyfish).

Programming language: Bash

-

Other requirements:

License: Apache-2.0 license

All datasets used during the testing phase of the aws-s3-integrity-check tool, are available within the EGA and GigaDB platforms.

The dataset stored within the Amazon S3 bucket

‘mass-spectrometry-imaging’ was generated by Guo A. et al [

18] and it is available on the GigaDB platform (DOI:10.5524/102374).

The dataset stored within the Amazon S3 bucket

‘tf-prioritizer’ was generated by Hoffmann M. et al. [

20], which is available on the GigaDB platform (DOI:10.5524/102379).

The dataset stored within the Amazon S3 bucket

‘rnaseq-pd‘ was generated by Feleke, Reynolds et al. [

19] and is available under request from EGA with accession number EGAS00001006380.

The dataset stored within the Amazon S3 bucket

‘ukbec-unaligned-fastq’ was a subset of the original dataset generated by Guelfi et al. [

21], which is available under request from EGA with accession number EGAS00001003065.

Author Contributions

S.G.R implemented the aws-s3-integrity-check bash tool, created the manuscript, provided the cloud computing expertise, designed the case study, created the Docker image and conducted the empirical experiments. R.H.R. provided new ideas for feature development and SSO knowledge. R.H.R., M.G-P, Z.C and A.F.-B. proofread the manuscript. R.H.R, E.K.G, J.W.B, M.G-P, A.F.-B and Z.C helped during the empirical experiments. M.R. supervised the tool implementation.

Acknowledgments

We acknowledge support from the AWS Cloud Credits for Research (to S.G.R.) for providing cloud computing resources. S.G.R., R.H.R., M.G-P., J.W.B and M.R. were supported through the award of a Tenure Track Clinician Scientist Fellowship to M.R. (MR/N008324/1). E.K.G. was supported by the Postdoctoral Fellowship Program in Alzheimer’s Disease Research from the BrightFocus Foundation (Award Number: A2021009F). Z.C. was supported by a clinical research fellowship from the Leonard Wolfson Foundation. A.F.-B. was supported through the award of a Biotechnology and Biological Sciences Research Council (BBSRC UK) London Interdisciplinary Doctoral Fellowship. We acknowledge Antonio Espinosa; James Seward; Alejandro Martinez; Andy Wu; Carlo Mendola; Marc Tamsky for their contributions to the GitHub repository.

Competing Interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Abbreviations

| Amazon S3 |

Amazon Simple Storage Service; |

| API |

Application Programming Interface; |

| AWS |

Amazon Web Services; |

| AWS CLI |

AWS Command Line Interface; |

| DOI |

Digital Object Identifier; |

| EGA |

European Genome-phenome Archive; |

| ETag |

Entity Tag; |

| FTP |

File Transfer Protocol; |

| GB |

Gigabytes; |

| JSON |

JavaScript Object Notation; |

| MB |

Megabytes; |

| NGS |

Next Generation Sequencing; |

| SSE-C |

Server-side encryption with customer-provided encryption keys; |

| SSE-KMS |

Server-side encryption with AWS Key Management Service keys; |

| SSE-S3 |

Server-side encryption with Amazon S3 managed keys; |

| SSO |

Single Sign-On; |

| TB |

Terabytes; |

References

- Goodwin S, McPherson JD, McCombie WR. Coming of age: ten years of next-generation sequencing technologies. Nat Rev Genet. 2016, 17, 333–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marx, V. Method of the year: long-read sequencing. Nat Methods. 2023, 20, 6–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Angerer P, Simon L, Tritschler S, Wolf FA, Fischer D, Theis FJ. Single cells make big data: New challenges and opportunities in transcriptomics. Current Opinion in Systems Biology. 2017, 4, 85–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmidt B, Hildebrandt A. Next-generation sequencing: big data meets high performance computing. Drug Discov Today. 2017, 22, 712–717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fang S, Chen B, Zhang Y, Sun H, Liu L, Liu S, et al. Computational approaches and challenges in spatial transcriptomics. Computational approaches and challenges in spatial transcriptomics. Genomics Proteomics Bioinformatics. 2022.

- Cloud Computing Services - Amazon Web Services (AWS). https://aws.amazon.com/. Accessed 14 Apr 2023.

- Langmead B, Schatz MC, Lin J, Pop M, Salzberg SL. Searching for SNPs with cloud computing. Genome Biol. 2009, 10, R134. [Google Scholar]

- Wall DP, Kudtarkar P, Fusaro VA, Pivovarov R, Patil P, Tonellato PJ. Cloud computing for comparative genomics. BMC Bioinformatics. 2010, 11, 259. [Google Scholar]

- Halligan BD, Geiger JF, Vallejos AK, Greene AS, Twigger SN. Low cost, scalable proteomics data analysis using Amazon’s cloud computing services and open source search algorithms. J Proteome Res. 2009, 8, 3148–3153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dickens PM, Larson JW, Nicol DM. Diagnostics for causes of packet loss in a high performance data transfer system. In: 18th International Parallel and Distributed Processing Symposium, 2004. Proceedings. IEEE; 2004. p. 55–64.

- RFC 1864 - The Content-MD5 Header Field. https://datatracker.ietf.org/doc/html/rfc1864. Accessed 14 Apr 2023.

- Checking object integrity - Amazon Simple Storage Service. https://docs.aws.amazon.com/AmazonS3/latest/userguide/checking-object-integrity.html. Accessed 31 Jul 2023.

- AWS CLI S3 Configuration — AWS CLI 1.27.115 Command Reference. https://docs.aws.amazon.com/cli/latest/topic/s3-config.html. Accessed 19 Apr 2023.

- antespi/s3md5: Bash script to calculate Etag/S3 MD5 sum for very big files uploaded using multipart S3 API. https://github.com/antespi/s3md5. Accessed 16 Apr 2023.

- Freeberg MA, Fromont LA, D’Altri T, Romero AF, Ciges JI, Jene A, et al. The European Genome-phenome Archive in 2021. Nucleic Acids Res. 2022, 50, D980–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sneddon TP, Zhe XS, Edmunds SC, Li P, Goodman L, Hunter CI. GigaDB: promoting data dissemination and reproducibility. Database (Oxford). 2014, 2014, bau018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- sync — AWS CLI 2.11.13 Command Reference. https://awscli.amazonaws.com/v2/documentation/api/latest/reference/s3/sync.html. Accessed 16 Apr 2023.

- GigaDB Dataset -. https://doi.org/10.5524/102374 - Supporting data for "Delineating Regions-of-interest for Mass Spectrometry Imaging by Multimodally C ... http://gigadb.org/dataset/102374. Accessed 12 May 2023.

- Feleke R, Reynolds RH, Smith AM, Tilley B, Taliun SAG, Hardy J, et al. Cross-platform transcriptional profiling identifies common and distinct molecular pathologies in Lewy body diseases. Acta Neuropathol. 2021, 142, 449–474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- GigaDB Dataset -. https://doi.org/10.5524/102379 - Supporting data for "TF-Prioritizer: a java pipeline to prioritize condition-specific transcription ... http://gigadb.org/dataset/102379. Accessed 12 May 2023.

- Guelfi S, D’Sa K, Botía JA, Vandrovcova J, Reynolds RH, Zhang D, et al. Regulatory sites for splicing in human basal ganglia are enriched for disease-relevant information. Nat Commun. 2020, 11, 1041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- time(1) - Linux manual page. https://man7.org/linux/man-pages/man1/time.1.html. Accessed 30 Jul 2023.

- NumPy documentation — NumPy v1.25.dev0 Manual. https://numpy.org/devdocs/index.html. Accessed 12 May 2023.

- IBM Documentation. https://www.ibm.com/docs/en/aix/7.1?topic=g-getopts-command. Accessed 16 Apr 2023.

- ls — AWS CLI 2.11.13 Command Reference. https://awscli.amazonaws.com/v2/documentation/api/latest/reference/s3/ls.html. Accessed 16 Apr 2023.

- list-objects — AWS CLI 1.27.114 Command Reference. https://docs.aws.amazon.com/cli/latest/reference/s3api/list-objects.html. Accessed 16 Apr 2023.

- md5sum invocation (GNU Coreutils 9.2). https://www.gnu.org/software/coreutils/manual/html_node/md5sum-invocation.html#md5sum-invocation. Accessed 14 Apr 2023.

- Rivest R. The MD5 Message-Digest Algorithm. RFC Editor; 1992.

- md5sum(1): compute/check MD5 message digest - Linux man page. https://linux.die.net/man/1/md5sum. Accessed 16 Apr 2023.

- jq. https://stedolan.github.io/jq/. Accessed 16 Apr 2023.

- Docker: Accelerated, Containerized Application Development. https://www.docker.com/. Accessed 16 Apr 2023.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).