Submitted:

31 July 2023

Posted:

02 August 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

Introduction

Methods

Exploring Brainstem and Spinal Cord Functionality

Brainstem Auditory Evoked Potentials (BAEPs)

Somatosensory Evoked Potentials (SEPs)

Motor Evoked Potentials

Electromyography and Nerve Conduction Studies

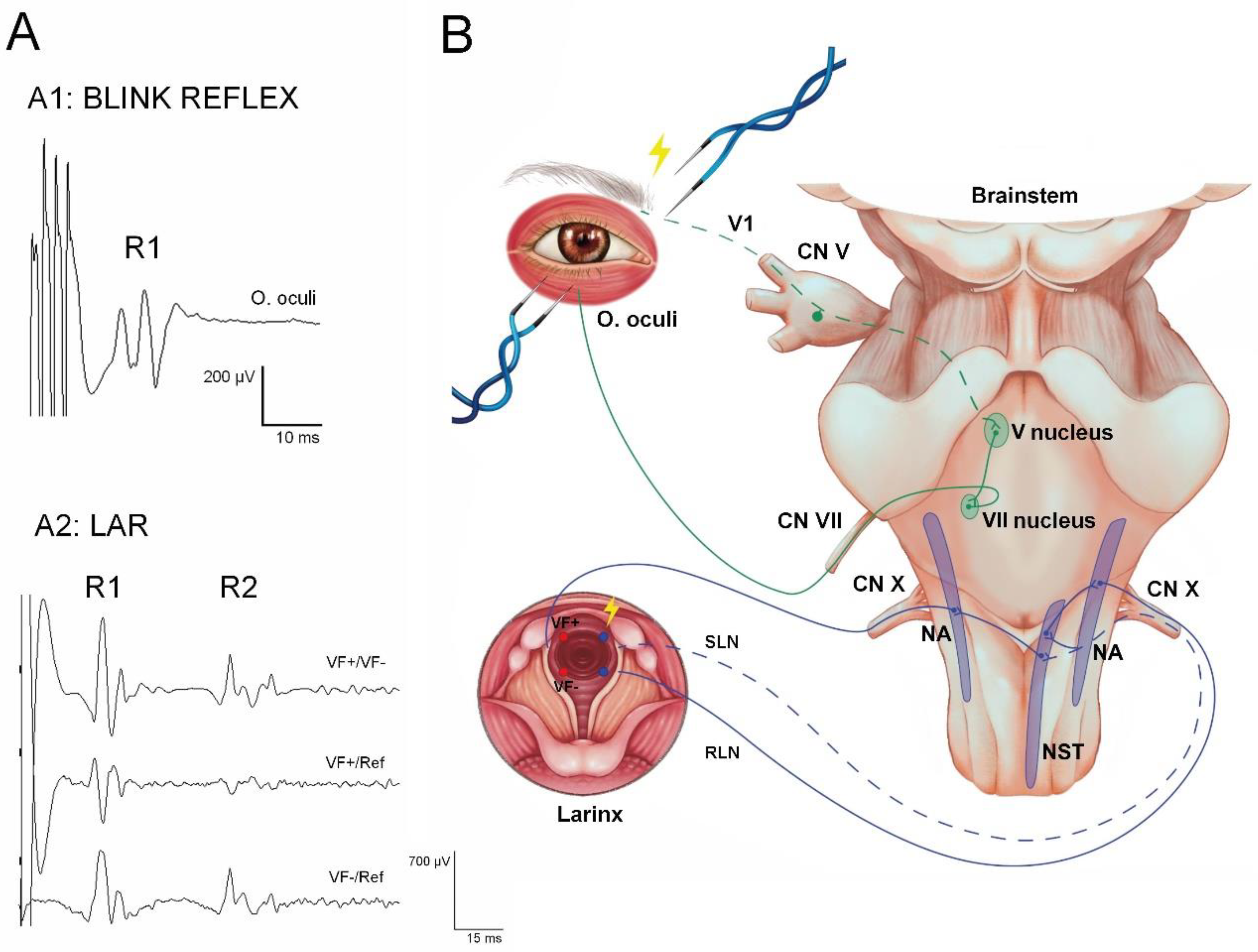

Brainstem Reflexes

Neurophysiological Limitations in the Developing Central Nervous System

Follow-Up Neurophysiological Studies in Patients with CM1

Brainstem Auditory Evoked Potentials

| Author | Year | N | Age/Sex | SYR | SCOL | BAEPs | SEPs | MEPs | EMG/NCS | Brainstem reflexes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cocito et al. [104] |

2022 | 100 Symptomatic CM1=34 CM1+SYR=53 SYR=13 |

23–75-y-o 25♂ / 75♀ |

66 | TMS of phrenic nerve: In 48%--> alt. C5-MEP. In 20%--> absence or delay of Cz-MEP Alterations of the Cz-MEP and C5-MEP were prevalent in patients with cervical SYR/syringobulbia, most associated with CM1 |

|||||

| Di Stefano et al. [90] | 2019 | Comparison between groups: IH = 18 CM1 = 18 SNHL= 20 Normal controls = 52 |

CM1 49 ± 11-y-o 12♂ / 6♀ |

Wave V, I—III, and III-V IPL were higher in CM1 than in controls | ||||||

| Guvenc et al. [98] | 2019 | T=27 | 15-62-y-o 7♂ / 20♀ |

Abnormal SEP in 22.2%. Much more frequent in PTN than in MN. There was a significant correlation between CSF flow disturbance, the degree of TE (P=0.038), and the presence of SEP abnormalities (P=0.016). CSF flow disturbance and SEP abnormalities are more frequently seen in patients with platybasia | ||||||

| Jayamanne et al. [111] | 2018 | T=1 Presenting as left foot drop |

6-y-o ♀ |

YES (holocord SYR) |

NCS: CPN, PTN, and sural nerve were normal. EMG at left TA revealed fibrillations and scant MUPs. EMG of left medial gastrocnemius and right TA were normal | |||||

| Stancanelli et al. [102] | 2018 | T=1 Presenting as excessive sweating on all the left side of the body |

22-y-o ♂ |

BAEPs were normal. | SEPs were normal. | MEP showed an asymmetric response with increased CMCT on the right upper and lower limbs |

Sudoscan test: Asymmetric sweating with a higher electrochemical skin conductance on the left hand and foot |

|||

| Moncho et al. [19] | 2016 | 200 | 15-70-y-o 58♂ / 142♀ CM0=14 CM1=137 CM1.5=49 |

YES (96) | Of all the variables introduced into the logistic regression, only age, the degree of TE, and lower cranial nerve dysfunction had a statistically significant influence on predicting abnormal BAEPs | Of all the variables introduced into the logistic regression model, only age and the degree of TE were statistically significant at predicting abnormal SEPs. BAEPs and SEPs play an essential role in clinically asymptomatic/oligosymptomatic patients |

||||

| Akakin et al. [96] | 2015 | T=1 | 34-y-o ♂ |

Large SYR from just below FM to T5 vertebral body. The spinal cord was thinned at these levels | Preoperatively, SEPs were abnormal: Increased N13-20 IPL of the MN SEP and reduced cortical AMP of the PTN SEP. After syringo-subarachnoid-peritoneal shunt insertion using a conventional lumbo-peritoneal shunt and a T-tub, the SEP test returned to normal | |||||

| Awai and Curt [101] | 2015 | T=7 SYR (1 CM1) |

32-53-y-o 6♂ / 1♀ MC1: 32-y-o ♂ |

YES | Differently affected dSEPs and dCHEPs. dCHEPs in at least one dermatome were abnormal in all patients | All patients had normal NCS and MEPs (of the upper limbs) | ||||

| Moncho et al. [20] | 2015 | 50 | 16-67-y-o 11 ♂ / 39♀ |

YES (20 patients) |

BAEPs were altered in 52%. The most common finding was increased I–V IPL and LAT of wave V (48%). A greater TE was observed in patients with pathological BAEPs compared with patients with normal BAEPs (but not statistically significant, possible type II error) | SEPs were altered by 50%. The most frequent alteration of MN SEP was increased N13-N20 IPL; the most frequent alteration of PTN SEP was an increased N22-P37 IPL, sometimes associated with alteration of the cervical potential. A greater TE was observed in patients with altered PTN SEPs and MN SEPs compared with patients with normal SEPs (but not statistically significant, possible type II error) |

||||

| Isik et al. [87] | 2013 | T= 44 SYR CM1= 32 |

14-71-y-o 24♂ / 20♀ |

YES | BAEP was only pathological in ten (31.2%) patients with CM1. Except for one patient, improvement was seen and correlated with neurological and radiological improvement (90%). This series suggested that BAEPs were more correlated with clinical and radiological findings than SEPs were | MN/PTN SEPs were abnormal in 54.2% of patients (Difficult to know the exact number of patients since the figures do not match). In this series, SEPs did not always correlate with the clinical findings |

||||

| Panda and Kaur [114] | 2013 | T=1 Rapidly progressive right foot drop |

16-y-o ♂ |

YES (holocord SYR) |

NCS: CPN normal BIL with absent bilateral F waves. PTN, sural, superficial peroneal, and saphenous nerve were normal. EMG: fibrillation potentials and positive sharp waves in the right TA, peroneus longus, medial gastrocnemius, gluteus medius, and lumbar paraspinal muscles confirming the lesion to be proximal (lumbar roots or anterior horn cell) |

|||||

| Vidmer et al. [89] | 2011 | T=66 (MC1 and 2) 1 MC1 |

3-months-60-y-o MC1: 9-y-o ♀ |

|

Peripheral or cochlear alteration in a single pediatric patient with CM1 | SEP of MN abnormal with increased LAT N20 and CCT UNIL Normal PTN SEP BIL |

||||

| Mc Millan et al. [113] | 2011 | T=2 Abrupt onset UNIL foot drop |

5 and 4.5-y-o 2♀ |

YES | Case 1) Not included or provided. Case 2) MN SEPs revealed prolonged cervical and cortical responses. PTN SEPs responses were poorly formed with normal latencies |

NCS: Case 1) CPN showed low motor AMP. EMG: fibrillation potentials and positive sharp waves confirming a proximal lesion. Case 2) EMG of the right TA revealed active denervation |

||||

| Saifudheen et al. [112] | 2011 | T=1 Rapidly progressive BIL foot drop |

14-y-o ♀ |

YES (holocord SYR) |

NCS: Low AMP CMAP and normal LAT and velocity for both peroneal and left ulnar nerves. The F wave was normal. Sensory median, ulnar, and sural nerves were normal. EMG: On both sides, chronic neurogenic changes in the first dorsal interossei, TA, and medial gastrocnemius muscles |

|||||

| Berciano et al. [100] | 2007 | T=1 Lancinating left cervico-brachial pain provoked by coughing fits |

54-y-o ♀ |

Cervico-dorsal SYR extending into the left posterolateral quadrant in axial sections passing through C7 and D1 vertebral levels | dSEPs left side: N20 of the C8 dermatome severely attenuated, both pre- and postoperatively. All other left-side dermatomes and right-hand dSEPs were normal Persistence of segmental hypoalgesia and altered SEPs despite the disappearance of SYR on MRI after PFD |

Bilateral motor and sensory conduction parameters of MN and UN, including F responses, were normal | ||||

| Henriques Filho and Pratesi [88] | 2006 | T=75 MC1=27 MC2=48 |

27 patients = 19-70-y-o 48 patients = 2-16-y-o |

First in frequency: alteration of wave I or cochlear level (“segment 1”) Second in frequency: alteration I-III or “between the acoustic nerve near the cochlea and the pontomedullary junction” (“segment 2”) Two patients with an abnormality in the AMP V/I ratio |

||||||

| Brookler [82] | 2005 | T=1 Dizziness |

63-y-o ♀ |

Delay of wave V and III-V BIL, with normal audiology | ||||||

| Utzig et al. [95] | 2003 | T=1 Headache, paresthesia, and SCOL |

15-y-o ♀ |

YES | YES | Left UN/ PTN SEPs: Absence of cortical responses. After SUR: Cortical responses of reduced amplitude for left extremities | ||||

| Hausmann et al. [144] | 2003 | T=100 MC1 =1 |

15.3 ± 2.2-y-o 20♂ / 80♀ |

3 | 100 | Normality in PTN SEPs in the patient with MC1 | ||||

| Muhn et al. [110] | 2002 | T=1 Rapidly progressive UNIL leg weakness |

5-y-o ♂ |

YES | NCS showed a low-amplitude CMAP for the left peroneal and normal sural nerve. EMG of the left TA, tibialis posterior, and medial gastrocnemius muscles showed fibrillation potentials at rest and reduced voluntary recruitment action potentials. A follow-up eight weeks after PFD showed improvement in leg strength with a co-temporal resolution of the previously observed fibrillation potentials | |||||

| Paulig and Prosiegel [107] | 2002 | T=1 Progressive dysphagia for a year |

78-y-o ♀ |

SEPs were normal | NRL examination: BIL paresis and atrophy of the tongue showed diffuse fibrillations. Further neurological examination was normal. NCS and EMG of various muscles of the upper and lower limbs were normal |

|||||

| Bagnato et al. [108] | 2001 | T=1 Presenting as spinal myoclonus |

48-y-o ♂ |

YES | Left MN SEPs revealed normal P14 and N20, while the N13, obtained after glottis reference, was nearly abolished | EMG: 1) Chronic partial denervation in C8/D1 muscles; 2) Rhythmic contractions in FDI and ABP muscles (spinal myoclonus), and 3) Peripheral silent period after supramaximal electrical stimulation of UN at FDI muscle | ||||

| Jacome [122] | 2001 | T = 4 CM1 presented with blepharoclonus |

17-52-y-o 1♂ / 3♀ |

1 | Facial EMG: complex repetitive discharges of the right mentalis muscle in one patient | Blink reflexes were abnormal in 3 patients | ||||

| Scelsa [109] | 2000 | T=1 Presenting as ulnar neuropathy at the elbow |

24-y-o ♀ |

YES | YES | NCS: Marked AMP reduction of the left ulnar CMAP without focal slowing or conduction block across the elbow. EMG: Fibrillations and high AMP MUP in left arm muscles innervated by C7-D1 spinal segments and the median and ulnar nerves |

||||

| Cheng et al. [99] | 1999 | T=164 MC1=12 |

10-20-y-o (m₁=14.2) (m₂=13.6) 22♂ / 142♀ |

6 | 164 | MN and PTN SEPs. Association between TE and SEP dysfunction (P<0.001; c.c 0.672 Spearman). No differences in the degree of TE in patients with normal SEPs and those with abnormal SEPs (P=0.864; Mann-Whitney) |

||||

| Hort-Legrand and Emery [86] | 1999 | T=79 SYR -Foraminal (64) -Meningitis (5) -Trauma (15) CM1=48 (CVJM=11 BI=7) |

SYR foraminal 16-71-y-o 27♂ / 22♀ |

YES | 11 | BAEPs were performed in all patients except 20, in whom the upper level of the SYR was in the lower cervical or the dorsal vertebrae. BAEPs were abnormal in 13 of the 59 patients studied (total cohort), 6 with CVJM. The more frequent finding was I-V IPL PROL UNIL, less frequently BIL. (They did not specify how many patients with CM1 underwent BAEP or what the results were in this subgroup) |

MN and PTN SEPs in all patients. Abnormality (PTN or MN) was noted in 77 of the 79 patients. The most frequent findings for MN SEPs were altered cervical N13 response, an anomaly of the P14-N20 interval, or altered cortical response. The most frequent findings of PTN SEP were an absence of cortical waves or a decrease in their amplitude. SEPs of the trigeminal nerve (V3) were recorded in 60 patients. Prolonged LAT UNIL (less frequently BIL). Much more sensitive than BAEPs: always altered when bulbar symptoms present, while MRI in no case showed syringobulbia. (They did not specify test results in the CM1 subgroup) |

MEPs of the upper limbs in 60 patients. More frequent findings were: PROL CCT, reduced AMP, or very polyphasic responses. (They did not specify test results in the CM1 subgroup) |

||

| Ahmmed et al. [85] | 1996 | T=1 Tinnitus and mild hearing loss in the left ear |

13-y-o ♀ |

Asymmetry in III, V LAT, and I-V IPL, more prolonged in the left ear that returned to normal values after PFD | ||||||

| Amoiridis et al. [121] | 1996 | T=1 Dysesthesia and weakness with urinary retention |

25-y-o ♂ Mild hydrocephalus |

YES | YES | PTN SEPs: No lumbar potential (N24; Ll/iliac crest) could be obtained, whereas a high cervical potential (N33; C2/Fz) and a cortical (P40; Cz' /Fz) potential with a normal latency was registered. The MN SEP was normal | AMP of the H reflex in the soleus muscle was low bilaterally, and the H reflex LAT was prolonged on the right. Motor and sensory NCS were normal. F waves in AH, EDB, or hypothenar muscles, all on the left, were not elicited |

BR: Rl was absent bilaterally, and R2 latency with left side stimulation was prolonged BIL | ||

| Kaneko et al. [120] | 1996 | T=5 | Mean age 18-y-o ♂ |

YES (cervical) | Absent or reduced cervical N13 SEP with preserved cortical responses of the upper limb were observed in 3 of the 5 patients | MEP latency and amplitude were normal in all patients | CMAP latency and amplitude were normal in all patients. Symptomatically, all patients showed diminished cutaneous silent periods (CSPs) up to a stimulus intensity of 15 times the sensory threshold. Diminished CSP was the only abnormal finding in 2 subjects. Also, CSP decrease was more sensitive to syringomyelic changes than abnormal cervical N13 SEP |

|||

| Cristante et al. [105] | 1994 | T=26 CM1 (8 with MEPs) |

YES (5) | Preoperative TMS MEPs: functionally impaired muscles with an abnormal recording. The postoperative functional motor recovery was not reflected by improvement in MEP parameters | ||||||

| Johnson et al. [84] | 1994 | T=1 Steadily progressive bilateral asymmetrical SNHL |

10-y-o ♂ |

NO | CCT or I-V BIL increased: Increased I-III in one ear and III-V in the other | |||||

| Strowitzki et al. [97] | 1993 | T=18 CM1=9 |

YES | MN SEPs: Abnormal in 4 patients. PTN SEPs: Abnormal in 7 patients. No cortical responses were found in 6 patients and delayed responses in 2 (does not specify MN or PTN) | ||||||

| Morioka et al. [94] | 1992 | T= 11 (cervical SYR) CM1= 10 |

24-56-y-o 3♂ / 7♀ |

YES | The most common MN SEP abnormality was UNIL attenuation or absence of N13 often with normal N20 potentials. Spinal EPs provided information regarding abnormality responsible for the dorsal column dysfunction: the syrinx, the TE, or both | |||||

| Nogués et al. [103] | 1992 | T=13 MC1=7 BI=1 | 19-53-y-o (m=37.4) 7♂ / 6♀ |

T=13 | SEPs: Alteration of cortical PTN and reduction or absence of cervical potential of MN | The most frequent finding was an increase in CMTC | ||||

| Gerard et al. [106] | 1992 | T=1 BI Presenting as velar insufficiency |

5-y-o ♀ |

Velar insufficiency: EMG BIL in levator palatini and anterior faucial pillars showed ample biphasic or polyphasic action potentials at rest; when the child cried, the frequency of these potentials increased poorly, and recruitment was impaired. Suspicion of denervation of the IX, X, and XI cranial nerves | ||||||

| Hendrix et al. [83] | 1992 | T=3 | 59,34, 64-y-o | BAEPs were abnormal in one patient: prolonged I-V IPL on the right side. The other two patients had normal BAEPs BIL |

||||||

| Restuccia and Maguière [39] | 1991 | T=24 MC1=16 (9 *) |

20-74-y-o (m=56) 10♂ / 14♀ |

T=24 | MN SEPs: abnormal or absent N13 in 83% of patients with cervical SYR. Good correlation between loss of thermoalgesic sensation and absence of tendon reflexes. With associated CM: increased P14-N20 IPL |

|||||

| Jabbari et al. [93] | 1990 | T=22 MC1=4 |

15-69-y-o (m=28) 15♂ / 7♀ |

T=22 | No significant relationship between SEPs in SYR when CM coexists: In 3 of 4 patients with SYR and CM, SEPs were normal | |||||

| Forcadas et al. [92] | 1988 | T=18 MC1=17 |

12 | MN SEPs: more frequent abnormal N11-N13 with or without abnormal CCT. Good correlation with clinical symptoms. Two of the three patients with normal N11-N13 and abnormal CCT had MC1 without SYR | ||||||

| Anderson et al. [91] | 1986 | T=9 MC1= 8 |

16-65-y-o (m=41) 1♂ / 8♀ |

T=9 | MN SEPs: AMP reduction or absence of the cervical potential, consistent with the clinically more affected side. Seven of the 8 cases with CM1 had a prolonged or asymmetric CCT. One case with MC-1 presented normal MN SEPs |

|||||

| Stone et al. [81] | 1983 | T=1 Classified by the authors as MC2 (but without overt spinal defects), probably CM1.5 |

16-y-o ♂ With associated hydrocephalus |

BAEPs: PROL I-III and I-V IPL in the left ear. Absence of wave III; I-V IPL more PROL in the right ear. Postoperative BAEPs showed BIL normalization |

Somatosensory Evoked Potentials

Motor Evoked Potentials

NCS, EMG, and other Peripheral Nerve Studies

Brainstem Reflexes

Intraoperative Neurophysiological Monitoring in CM1

Conclusions

Author contributions

Author Disclosure Statement

Acknowledgments

References

- Cleland, null Contribution to the Study of Spina Bifida, Encephalocele, and Anencephalus. J Anat Physiol 1883, 17, 257–292.

- Chiari H Über Veränderungen Des Kleinhirns Infolge von Hydrocephalie Des Grosshirns. Dtsch Med Wochenschr 1891, 17, 1172–1175. [CrossRef]

- Chiari H Über veränderungen des Kleinhirns, des Pons un der Medulla Oblongata in folge von congenitaler Hydrocephalie des Grosshirns. Denkschr Akad Wiss Wien 1896, 63, 71–116.

- Chiari, H. Concerning Alterations in the Cerebellum Resulting from Cerebral Hydrocephalus. 1891. Pediatr Neurosci 1987, 13, 3–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cruveilhier J L’anatomie Pathologique Du Corps Humain; Descriptions Avec Figures Lithographiées et Coloriées; Diverses Altérations Morbides Dont Le Corps Humain et Susceptible; Bailliere: Paris, 1829.

- Mortazavi, M.M.; Tubbs, R.S.; Brockerhoff, M.A.; Loukas, M.; Oakes, W.J. The First Description of Chiari I Malformation with Intuitive Correlation between Tonsillar Ectopia and Syringomyelia. J Neurosurg Pediatr 2011, 7, 257–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barkovich, A.J.; Wippold, F.J.; Sherman, J.L.; Citrin, C.M. Significance of Cerebellar Tonsillar Position on MR. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol 1986, 7, 795–799. [Google Scholar]

- Bogdanov, E.I.; Heiss, J.D.; Mendelevich, E.G.; Mikhaylov, I.M.; Haass, A. Clinical and Neuroimaging Features of “Idiopathic” Syringomyelia. Neurology 2004, 62, 791–794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Botelho, R.V.; Bittencourt, L.R.A.; Rotta, J.M.; Tufik, S. A Prospective Controlled Study of Sleep Respiratory Events in Patients with Craniovertebral Junction Malformation. J. Neurosurg. 2003, 99, 1004–1009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meadows, J.; Kraut, M.; Guarnieri, M.; Haroun, R.I.; Carson, B.S. Asymptomatic Chiari Type I Malformations Identified on Magnetic Resonance Imaging. J. Neurosurg. 2000, 92, 920–926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milhorat, T.H.; Nishikawa, M.; Kula, R.W.; Dlugacz, Y.D. Mechanisms of Cerebellar Tonsil Herniation in Patients with Chiari Malformations as Guide to Clinical Management. Acta Neurochir (Wien) 2010, 152, 1117–1127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sekula, R.F.; Jannetta, P.J.; Casey, K.F.; Marchan, E.M.; Sekula, L.K.; McCrady, C.S. Dimensions of the Posterior Fossa in Patients Symptomatic for Chiari I Malformation but without Cerebellar Tonsillar Descent. Cerebrospinal Fluid Res 2005, 2, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tubbs, R.S.; Iskandar, B.J.; Bartolucci, A.A.; Oakes, W.J. A Critical Analysis of the Chiari 1.5 Malformation. J. Neurosurg. 2004, 101, 179–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tubbs, R.S.; Demerdash, A.; Vahedi, P.; Griessenauer, C.J.; Oakes, W.J. Chiari IV Malformation: Correcting an over One Century Long Historical Error. Childs Nerv Syst 2015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ciaramitaro, P.; Massimi, L.; Bertuccio, A.; Solari, A.; Farinotti, M.; Peretta, P.; Saletti, V.; Chiapparini, L.; Barbanera, A.; Garbossa, D.; et al. Diagnosis and Treatment of Chiari Malformation and Syringomyelia in Adults: International Consensus Document. Neurol Sci 2022, 43, 1327–1342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Isik, N.; Elmaci, I.; Kaksi, M.; Gokben, B.; Isik, N.; Celik, M. A New Entity: Chiari Zero Malformation and Its Surgical Method. Turk Neurosurg 2011, 21, 264–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kyoshima, K.; Kuroyanagi, T.; Oya, F.; Kamijo, Y.; El-Noamany, H.; Kobayashi, S. Syringomyelia without Hindbrain Herniation: Tight Cisterna Magna. Report of Four Cases and a Review of the Literature. J. Neurosurg. 2002, 96, 239–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tubbs, R.S.; Elton, S.; Grabb, P.; Dockery, S.E.; Bartolucci, A.A.; Oakes, W.J. Analysis of the Posterior Fossa in Children with the Chiari 0 Malformation. Neurosurgery 2001, 48, 1050–1054, discussion 1054–1055. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Moncho, D.; Poca, M.A.; Minoves, T.; Ferré, A.; Cañas, V.; Sahuquillo, J. Are Evoked Potentials Clinically Useful in the Study of Patients with Chiari Malformation Type 1? J. Neurosurg. 2016, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moncho, D.; Poca, M.A.; Minoves, T.; Ferré, A.; Rahnama, K.; Sahuquillo, J. Brainstem Auditory and Somatosensory Evoked Potentials in Relation to Clinical and Neuroimaging Findings in Chiari Type 1 Malformation. J Clin Neurophysiol 2015, 32, 130–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferré, Á.; Poca, M.A.; de la Calzada, M.D.; Moncho, D.; Romero, O.; Sampol, G.; Sahuquillo, J. Sleep-Related Breathing Disorders in Chiari Malformation Type 1: A Prospective Study of 90 Patients. Sleep 2017, 40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferré, Á.; Poca, M.A.; de la Calzada, M.D.; Moncho, D.; Urbizu, A.; Romero, O.; Sampol, G.; Sahuquillo, J. A Conditional Inference Tree Model for Predicting Sleep-Related Breathing Disorders in Patients With Chiari Malformation Type 1: Description and External Validation. J Clin Sleep Med 2019, 15, 89–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moncho, D.; Poca, M.A.; Minoves, T.; Ferré, A.; Rahnama, K.; Sahuquillo, J. [Brainstem auditory evoked potentials and somatosensory evoked potentials in Chiari malformation]. Rev Neurol 2013, 56, 623–634. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Sahuquillo, J.; Moncho, D.; Ferré, A.; López-Bermeo, D.; Sahuquillo-Muxi, A.; Poca, M.A. A Critical Update of the Classification of Chiari and Chiari-like Malformations. Journal of Clinical Medicine 2023, 12, 4626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferré Masó, A.; Poca, M.A.; de la Calzada, M.D.; Solana, E.; Romero Tomás, O.; Sahuquillo, J. Sleep Disturbance: A Forgotten Syndrome in Patients with Chiari I Malformation. Neurologia 2011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferré, Á.; Poca, M.A.; de la Calzada, M.D.; Moncho, D.; Romero, O.; Sampol, G.; Sahuquillo, J. Sleep-Related Breathing Disorders in Chiari Malformation Type 1. A Prospective Study of 90 Patients. Sleep 2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Møller, A.R. Monitoring Auditory Evoked Potentials. In Intraoperative Neurophysiological Monitoring; Humana Press: Totowa, New Jersey, 2006; pp. 85–124. ISBN 978-1-59745-018-8. [Google Scholar]

- Guérit, Jean-Michel Les potentiels évoqués; 2e éd.; Masson (Paris), 1993; Vol. 1 vol; ISBN 2-225-84107-1.

- Desmedt, J.E. [Physiology and Physiopathology of Somatic Sensations Studied in Man by the Method of Evoked Potentials]. J. Physiol. (Paris) 1987, 82, 64–136. [Google Scholar]

- Cracco, R.Q.; Cracco, J.B. Somatosensory Evoked Potential in Man: Far Field Potentials. Electroencephalogr Clin Neurophysiol 1976, 41, 460–466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cruccu, G.; Aminoff, M.J.; Curio, G.; Guerit, J.M.; Kakigi, R.; Mauguiere, F.; Rossini, P.M.; Treede, R.-D.; Garcia-Larrea, L. Recommendations for the Clinical Use of Somatosensory-Evoked Potentials. Clin Neurophysiol 2008, 119, 1705–1719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cruccu, G.; Aminoff, M.J.; Curio, G.; Guerit, J.M.; Kakigi, R.; Mauguiere, F.; Rossini, P.M.; Treede, R.-D.; Garcia-Larrea, L. Recommendations for the Clinical Use of Somatosensory-Evoked Potentials. Clin Neurophysiol 2008, 119, 1705–1719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nair, D.; Kumaraswamy, V.M.; Braver, D.; Kilbride, R.D.; Borges, L.F.; Simon, M.V. Dorsal Column Mapping via Phase Reversal Method: The Refined Technique and Clinical Applications. Neurosurgery 2014, 74, 437–446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simon, M.V.; Chiappa, K.H.; Borges, L.F. Phase Reversal of Somatosensory Evoked Potentials Triggered by Gracilis Tract Stimulation: Case Report of a New Technique for Neurophysiologic Dorsal Column Mapping. Neurosurgery 2012, 70, E783–788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cruccu, G.; García-Larrea, L. Clinical Utility of Pain--Laser Evoked Potentials. Suppl Clin Neurophysiol 2004, 57, 101–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Garcia-Larrea L Pain Evoked Potentials. In Handbook of neurology; Elsevier: Amsterdam, 2006; Vol. 81, pp. 439–462.

- Cruccu, G.; Anand, P.; Attal, N.; Garcia-Larrea, L.; Haanpää, M.; Jørum, E.; Serra, J.; Jensen, T.S. EFNS Guidelines on Neuropathic Pain Assessment. Eur J Neurol 2004, 11, 153–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kakigi, R.; Inui, K.; Tamura, Y. Electrophysiological Studies on Human Pain Perception. Clin Neurophysiol 2005, 116, 743–763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Restuccia, D.; Mauguière, F. The Contribution of Median Nerve SEPs in the Functional Assessment of the Cervical Spinal Cord in Syringomyelia. A Study of 24 Patients. Brain 1991, 114 Pt 1B, 361–379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dotson, R.M.; Sandroni, P. CONTACT HEAT EVOKED POTENTIALS. In Clinical Neurophsyiology; Contemporary Neurology Series; OUP USA, 2009; pp. 688–692 ISBN 978-0-19-538511-3.

- Leandri, M.; Marinelli, L.; Siri, A.; Pellegrino, L. Micropatterned Surface Electrode for Massive Selective Stimulation of Intraepidermal Nociceptive Fibres. J Neurosci Methods 2018, 293, 17–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magnetic Stimulation in Clinical Neurophysiology; Hallett, M. , Chokroverty, S., Eds.; 2nd ed.; Elsevier Butterworth-Heinemann: Philadelphia, Pa, 2005; ISBN 978-0-7506-7373-0. [Google Scholar]

- Claus, D. Central Motor Conduction: Method and Normal Results. Muscle Nerve 1990, 13, 1125–1132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strommen, J.A. Motor Evoked Potentials. In Clinical Neurophsyiology; Contemporary Neurology Series; OUP USA, 2009; pp. 385–397 ISBN 978-0-19-538511-3.

- Kimura, J. Motor Evoked Potentials. In Electrodiagnosis in Diseases of Nerve and Muscle: Principles and Practice; Oxford University Press, 2013; pp. 526–551 ISBN 978-0-19-935316-3.

- Deletis, V.; Fernández-Conejero, I. Intraoperative Monitoring and Mapping of the Functional Integrity of the Brainstem. J Clin Neurol 2016, 12, 262–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deletis, V. Intraoperative Neurophysiology of the Corticospinal Tract of the Spinal Cord. Suppl Clin Neurophysiol 2006, 59, 107–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deletis, V.; Seidel, K.; Sala, F.; Raabe, A.; Chudy, D.; Beck, J.; Kothbauer, K.F. Intraoperative Identification of the Corticospinal Tract and Dorsal Column of the Spinal Cord by Electrical Stimulation. J. Neurol. Neurosurg. Psychiatry 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simon, M.V. Intraoperative Clinical Neurophysiology: A Comprehensive Guide to Monitoring and Mapping; Demos Medical: New York, 2010; ISBN 978-1-933864-46-4. [Google Scholar]

- Kugelberg, E. [Facial reflexes]. Brain 1952, 75, 385–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Smith, B.E. Cranial Reflexes and Related Techniques. In Clinical Neurophsyiology; OUP USA, 2009; pp. 529–542 ISBN 978-0-19-538511-3.

- Deletis, V.; Urriza, J.; Ulkatan, S.; Fernandez-Conejero, I.; Lesser, J.; Misita, D. The Feasibility of Recording Blink Reflexes under General Anesthesia. Muscle Nerve 2009, 39, 642–646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aydinlar, E.I.; Kocak, M.; Soykam, H.O.; Mat, B.; Dikmen, P.Y.; Sezerman, O.U.; Elmaci, İ.; Pamir, M.N. Intraoperative Neuromonitoring of Blink Reflex During Posterior Fossa Surgeries and Its Correlation With Clinical Outcome. J Clin Neurophysiol 2022, 39, 299–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernández-Conejero, I.; Ulkatan, S.; Deletis, V. Chapter 10 - Monitoring Cerebellopontine Angle and Skull Base Surgeries. In Handbook of Clinical Neurology; Nuwer, M.R., MacDonald, D.B., Eds.; Intraoperative Neuromonitoring; Elsevier, 2022; Vol. 186, pp. 163–176.

- Karakis, I.; Simon, M.V. Neurophysiologic Mapping and Monitoring of Cranial Nerves and Brainstem. In Intraoperative Neurophysiology; Simon, M.V., Ed.; Springer Publishing Company: New York, 2018; pp. 345–388. ISBN 978-1-62070-117-1. [Google Scholar]

- Mirallave Pescador, A.; Téllez, M.J.; Sánchez Roldán, M. de L.Á.; Samusyte, G.; Lawson, E.C.; Coelho, P.; Lejarde, A.; Rathore, A.; Le, D.; Ulkatan, S. Methodology for Eliciting the Brainstem Trigeminal-Hypoglossal Reflex in Humans under General Anesthesia. Clin Neurophysiol 2022, 137, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ishiwata, Y.; Ono, T.; Kuroda, T.; Nakamura, Y. Jaw-Tongue Reflex: Afferents, Central Pathways, and Synaptic Potentials in Hypoglossal Motoneurons in the Cat. J Dent Res 2000, 79, 1626–1634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lowe, A.A. The Neural Regulation of Tongue Movements. Prog Neurobiol 1980, 15, 295–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morimoto, T.; Kawamura, Y. Properties of Tongue and Jaw Movements Elicited by Stimulation of the Orbital Gyrus in the Cat. Arch Oral Biol 1973, 18, 361–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, P.; Zhang, J.; Yang, R.; Pendlebury, W. Neuronal Circuitry and Synaptic Organization of Trigeminal Proprioceptive Afferents Mediating Tongue Movement and Jaw-Tongue Coordination via Hypoglossal Premotor Neurons. Eur J Neurosci 2006, 23, 3269–3283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Godaux, E.; Desmedt, J.E. Human Masseter Muscle: H- and Tendon Reflexes. Their Paradoxical Potentiation by Muscle Vibration. Arch Neurol 1975, 32, 229–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kimura, J. H, T, and Masseter Reflexes and the Silent Period. In Electrodiagnosis in Diseases of Nerve and Muscle: Principles and Practice; Oxford University Press, 2013; pp. 216–218 ISBN 978-0-19-935316-3.

- Szentagothai, J. Anatomical Considerations on Monosynaptic Reflex Arcs. J Neurophysiol 1948, 11, 445–454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ulkatan, S.; Jaramillo, A.M.; Téllez, M.J.; Goodman, R.R.; Deletis, V. Feasibility of Eliciting the H Reflex in the Masseter Muscle in Patients under General Anesthesia. Clin Neurophysiol 2017, 128, 123–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sinclair, C.F.; Téllez, M.J.; Tapia, O.R.; Ulkatan, S.; Deletis, V. A Novel Methodology for Assessing Laryngeal and Vagus Nerve Integrity in Patients under General Anesthesia. Clin Neurophysiol 2017, 128, 1399–1405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sinclair, C.F.; Téllez, M.J.; Ulkatan, S. Noninvasive, Tube-Based, Continuous Vagal Nerve Monitoring Using the Laryngeal Adductor Reflex: Feasibility Study of 134 Nerves at Risk. Head Neck 2018, 40, 2498–2506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ludlow, C.L.; Van Pelt, F.; Koda, J. Characteristics of Late Responses to Superior Laryngeal Nerve Stimulation in Humans. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol 1992, 101, 127–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sasaki, C.T.; Suzuki, M. Laryngeal Reflexes in Cat, Dog, and Man. Arch Otolaryngol 1976, 102, 400–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Téllez, M.J.; Mirallave-Pescador, A.; Seidel, K.; Urriza, J.; Shoakazemi, A.; Raabe, A.; Ghatan, S.; Deletis, V.; Ulkatan, S. Neurophysiological Monitoring of the Laryngeal Adductor Reflex during Cerebellar-Pontine Angle and Brainstem Surgery. Clin Neurophysiol 2021, 132, 622–631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaneoka, A.; Pisegna, J.M.; Inokuchi, H.; Ueha, R.; Goto, T.; Nito, T.; Stepp, C.E.; LaValley, M.P.; Haga, N.; Langmore, S.E. Relationship Between Laryngeal Sensory Deficits, Aspiration, and Pneumonia in Patients with Dysphagia. Dysphagia 2018, 33, 192–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tarantino, V.; Stura, M.; Vallarino, R. [Development of Auditory Evoked Potentials of the Brainstem in Relation to Age]. Pediatr Med Chir 1988, 10, 73–76. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Reroń, E.; Sekuła, J. Maturation of the Acoustic Path-Way in Brain Stem Responses (ABR) in Neonates. Otolaryngol Pol 1994, 48, 363–369. [Google Scholar]

- Boor, R.; Goebel, B. Maturation of Near-Field and Far-Field Somatosensory Evoked Potentials after Median Nerve Stimulation in Children under 4 Years of Age. Clin Neurophysiol 2000, 111, 1070–1081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hameed, M.Q.; Dhamne, S.C.; Gersner, R.; Kaye, H.L.; Oberman, L.M.; Pascual-Leone, A.; Rotenberg, A. Transcranial Magnetic and Direct Current Stimulation in Children. Curr Neurol Neurosci Rep 2017, 17, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garvey, M.A. Transcranial Magnetic Stimulation in Children. In Magnetic stimulation in clinical neurophysiology; Hallett, M., Chokroverty, S., Eds.; Elsevier Butterworth-Heinemann: Philadelphia, Pa, 2005; pp. 429–433. ISBN 978-0-7506-7373-0. [Google Scholar]

- Kuntz, N.L. Chapter 6 - Clinical Neurophysiology of the Motor Unit in Infants and Children. In Clinical Neurophysiology of Infancy, Childhood, and Adolescence; Holmes, G.L., Jones, H.R., Moshé, S.L., Eds.; Butterworth-Heinemann: Philadelphia, 2006; pp. 130–145. ISBN 978-0-7506-7251-1. [Google Scholar]

- Sasaki, C.T.; Levine, P.A.; Laitman, J.T.; Crelin, E.S. Postnatal Descent of the Epiglottis in Man. A Preliminary Report. Arch Otolaryngol 1977, 103, 169–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, X.; Guo, R.; Zhao, W.; Pilowsky, P.M. Medullary Mediation of the Laryngeal Adductor Reflex: A Possible Role in Sudden Infant Death Syndrome. Respir Physiol Neurobiol 2016, 226, 121–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Costa, P.; Gaglini, P.P.; Tavormina, P.; Ricci, F.; Peretta, P. A Method for Intraoperative Recording of the Laryngeal Adductor Reflex during Lower Brainstem Surgery in Children. Clin Neurophysiol 2018, 129, 2497–2498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ulkatan, S.; Téllez, M.J.; Sinclair, C. Laryngeal Adductor Reflex and Future Projections for Brainstem Monitoring. Reply to “A Method for Intraoperative Recording of the Laryngeal Adductor Reflex during Lower Brainstem Surgery in Children.” Clin Neurophysiol 2018, 129, 2499–2500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stone, J.L.; Bouffard, A.; Morris, R.; Hovsepian, W.; Meyers, H.L. Clinical and Electrophysiologic Recovery in Arnold-Chiari Malformation. Surg Neurol 1983, 20, 313–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brookler, K.H. Vestibular Findings in a 62-Year-Old Woman with Dizziness and a Type I Chiari Malformation. Ear Nose Throat J 2005, 84, 630–631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hendrix, R.A.; Bacon, C.K.; Sclafani, A.P. Chiari-I Malformation Associated with Asymmetric Sensorineural Hearing Loss. J Otolaryngol 1992, 21, 102–107. [Google Scholar]

- Johnson, G.D.; Harbaugh, R.E.; Lenz, S.B. Surgical Decompression of Chiari I Malformation for Isolated Progressive Sensorineural Hearing Loss. Am J Otol 1994, 15, 634–638. [Google Scholar]

- Ahmmed, A.U.; Mackenzie, I.; Das, V.K.; Chatterjee, S.; Lye, R.H. Audio-Vestibular Manifestations of Chiari Malformation and Outcome of Surgical Decompression: A Case Report. J. LARYNGOL. OTOL. 1996, 110, 1060–1064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hort-Legrand, C.; Emery, E. Motor and sensory evoked potentials in syringomyelia. Neurochirurgie 1999, 45, 95–104. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Isik, N.; Elmaci, I.; Isik, N.; Cerci, S.; Basaran, R.; Gura, M.; Kalelioglu, M. Long-Term Results and Complications of the Syringopleural Shunting for Treatment of Syringomyelia: A Clinical Study. BRITISH JOURNAL OF NEUROSURGERY 2013, 27, 91–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Henriques Filho, P.S.A.; Pratesi, R. Abnormalities in Auditory Evoked Potentials of 75 Patients with Arnold-Chiari Malformations Types I and II. Arq Neuropsiquiatr 2006, 64, 619–623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vidmer, S.; Sergio, C.; Veronica, S.; Flavia, T.; Silvia, E.; Sara, B.; Valentini, L.G.; Daria, R.; Solero, C.L. The Neurophysiological Balance in Chiari Type 1 Malformation (CM1), Tethered Cord and Related Syndromes. Neurol. Sci. 2011, 32 Suppl 3, S311–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Stefano, V.; Ferrante, C.; Telese, R.; Caulo, M.; Bonanni, L.; Onofrj, M.; Franciotti, R. Brainstem Evoked Potentials and Magnetic Resonance Imaging Abnormalities in Differential Diagnosis of Intracranial Hypotension. Neurophysiol Clin 2019, 49, 217–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, N.E.; Frith, R.W.; Synek, V.M. Somatosensory Evoked Potentials in Syringomyelia. J. Neurol. Neurosurg. Psychiatr. 1986, 49, 1407–1410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forcadas, I.; Hurtado, P.; Madoz, P.; Zarranz, J.J. [Somatosensory Evoked Potentials in Syringomyelia and the Arnold-Chiari Anomaly. Clinical and Imaging Correlations]. Neurologia 1988, 3, 172–175. [Google Scholar]

- Jabbari, B.; Geyer, C.; Gunderson, C.; Chu, A.; Brophy, J.; McBurney, J.W.; Jonas, B. Somatosensory Evoked Potentials and Magnetic Resonance Imaging in Syringomyelia. Electroencephalogr Clin Neurophysiol 1990, 77, 277–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morioka, T.; Kurita-Tashima, S.; Fujii, K.; Nakagaki, H.; Kato, M.; Fukui, M. Somatosensory and Spinal Evoked Potentials in Patients with Cervical Syringomyelia. Neurosurgery 1992, 30, 218–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Utzig, N.; Burtzlaff, C.; Wiersbitzky, H.; Lauffer, H. [Evoked Potentials in Chiari-Malformation Type I with Syringomyelia--a Case History]. Klin Padiatr 2003, 215, 241–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akakın, A.; Yılmaz, B.; Ekşi, M.Ş.; Kılıç, T. Treatment of Syringomyelia Due to Chiari Type I Malformation with Syringo-Subarachnoid-Peritoneal Shunt. J. Korean Neurosurg. Soc. 2015, 57, 311–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Strowitzki, M.; Schwerdtfeger, K.; Donauer, E. The Value of Somato-Sensory Evoked Potentials in the Diagnosis of Syringomyelia. Acta Neurochir (Wien) 1993, 123, 184–187. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Guvenc, G.; Kızmazoglu, C.; Aydın, H.E.; Coskun, E. Somatosensory Evoked Potentials and Cerebrospinal Fluid Flow in Chiari Malformation. Annals of Clinical and Analytical Medicine 2019, 10, 348–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, J.C.; Guo, X.; Sher, A.H.; Chan, Y.L.; Metreweli, C. Correlation between Curve Severity, Somatosensory Evoked Potentials, and Magnetic Resonance Imaging in Adolescent Idiopathic Scoliosis. Spine 1999, 24, 1679–1684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berciano, J.; Poca, M.-A.; García, A.; Sahuquillo, J. Paroxysmal Cervicobrachial Cough-Induced Pain in a Patient with Syringomyelia Extending into Spinal Cord Posterior Gray Horns. J. Neurol. 2007, 254, 678–681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Awai, L.; Curt, A. Preserved Sensory-Motor Function despite Large-Scale Morphological Alterations in a Series of Patients with Holocord Syringomyelia. J. Neurotrauma 2015, 32, 403–410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stancanelli, C.; Mazzeo, A.; Gentile, L.; Vita, G. Unilateral Hyperhidrosis as Persistently Isolated Feature of Syringomyelia and Arnold Chiari Type 1. Neurol. Sci. 2018, 39, 1607–1608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nogués, M.A.; Pardal, A.M.; Merello, M.; Miguel, M.A. SEPs and CNS Magnetic Stimulation in Syringomyelia. Muscle Nerve 1992, 15, 993–1001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cocito, D.; Peci, E.; Garbossa, D.; Ciaramitaro, P. Neurophysiological Correlates in Patients with Syringomyelia and Chiari Malformation: The Cortico-Diaphragmatic Involvement. J Clin Med 2022, 11, 5080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cristante, L.; Westphal, M.; Herrmann, H.D. Cranio-Cervical Decompression for Chiari I Malformation. A Retrospective Evaluation of Functional Outcome with Particular Attention to the Motor Deficits. Acta Neurochir (Wien) 1994, 130, 94–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gerard, C.L.; Dugas, M.; Narcy, P.; Hertz-Pannier, J. Chiari Malformation Type I in a Child with Velopharyngeal Insufficiency. Dev Med Child Neurol 1992, 34, 174–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paulig, M.; Prosiegel, M. Misdiagnosis of Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis in a Patient with Dysphagia Due to Chiari I Malformation. JOURNAL OF NEUROLOGY NEUROSURGERY AND PSYCHIATRY 2002, 72, 270–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bagnato, S.; Rizzo, V.; Quartarone, A.; Majorana, G.; Vita, G.; Girlanda, P. Segmental Myoclonus in a Patient Affected by Syringomyelia. Neurol Sci 2001, 22, 27–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Scelsa, S. Syringomyelia Presenting as Ulnar Neuropathy at the Elbow. CLINICAL NEUROPHYSIOLOGY 2000, 111, 1527–1530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muhn, N.; Baker, S.K.; Hollenberg, R.D.; Meaney, B.F.; Tarnopolsky, M.A. Syringomyelia Presenting as Rapidly Progressive Foot Drop. J Clin Neuromuscul Dis 2002, 3, 133–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jayamanne, C.; Fernando, L.; Mettananda, S. Chiari Malformation Type 1 Presenting as Unilateral Progressive Foot Drop: A Case Report and Review of Literature. BMC Pediatr 2018, 18, 34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saifudheen, K.; Jose, J.; Gafoor, V.A. Holocord Syringomyelia Presenting as Rapidly Progressive Foot Drop. J Neurosci Rural Pract 2011, 2, 195–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McMillan, H.J.; Sell, E.; Nzau, M.; Ventureyra, E.C.G. Chiari 1 Malformation and Holocord Syringomyelia Presenting as Abrupt Onset Foot Drop. Child’s Nerv. Syst. 2011, 27, 183–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Panda, A.K.; Kaur, M. Rapidly Progressive Foot Drop: An Uncommon and Underappreciated Cause of Chiari I Malformation and Holocord Syrinx. BMJ Case Rep 2013, 2013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leis, A.A.; Kofler, M.; Ross, M.A. The Silent Period in Pure Sensory Neuronopathy. Muscle Nerve 1992, 15, 1345–1348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leis, A.A.; Stĕtkárová, I.; Berić, A.; Stokić, D.S. Spinal Motor Neuron Excitability during the Cutaneous Silent Period. Muscle Nerve 1995, 18, 1464–1470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McLellan, D.L. The Electromyographic Silent Period Produced by Supramaximal Electrical Stimulation in Normal Man. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 1973, 36, 334–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shefner, J.M.; Logigian, E.L. Relationship between Stimulus Strength and the Cutaneous Silent Period. Muscle Nerve 1993, 16, 278–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uncini, A.; Kujirai, T.; Gluck, B.; Pullman, S. Silent Period Induced by Cutaneous Stimulation. Electroencephalogr Clin Neurophysiol 1991, 81, 344–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaneko, K.; Kawai, S.; Fuchigami, Y.; Morita, H.; Ofuji, A. Cutaneous Silent Period in Syringomyelia. MUSCLE NERVE 1997, 20, 884–886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amoiridis, G.; Meves, S.; Schols, L.; Przuntek, H. Reversible Urinary Retention as the Main Symptom in the First Manifestation of a Syringomyelia. JOURNAL OF NEUROLOGY NEUROSURGERY AND PSYCHIATRY 1996, 61, 407–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jacome, D.E. Blepharoclonus and Arnold-Chiari Malformation. Acta Neurol Scand 2001, 104, 113–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, R.C.; Dowling, K.C.; Feldstein, N.A.; Emerson, R.G. Chiari I Malformation: Potential Role for Intraoperative Electrophysiologic Monitoring. J Clin Neurophysiol 2003, 20, 65–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zamel, K.; Galloway, G.; Kosnik, E.J.; Raslan, M.; Adeli, A. Intraoperative Neurophysiologic Monitoring in 80 Patients with Chiari I Malformation: Role of Duraplasty. J Clin Neurophysiol 2009, 26, 70–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, I.-K.; Wang, K.-C.; Kim, I.-O.; Cho, B.-K. Chiari 1.5 Malformation: An Advanced Form of Chiari I Malformation. J Korean Neurosurg Soc 2010, 48, 375–379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.A.; Coutin-Churchman, P.E.; Nuwer, M.R.; Lazareff, J.A. Suboccipital Craniotomy for Chiari I Results in Evoked Potential Conduction Changes. Surg Neurol Int 2012, 3, 165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kennedy, B.; Kelly, K.; Phan, M.; Bruce, S.; McDowell, M.; Anderson, R.; Feldstein, N. Outcomes after Suboccipital Decompression without Dural Opening in Children with Chiari Malformation Type I. JOURNAL OF NEUROSURGERY-PEDIATRICS 2015, 16, 150–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barzilai, O.; Roth, J.; Korn, A.; Constantini, S. The Value of Multimodality Intraoperative Neurophysiological Monitoring in Treating Pediatric Chiari Malformation Type I. Acta Neurochir (Wien) 2015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rasul, F.T.; Matloob, S.A.; Haliasos, N.; Jankovic, I.; Boyd, S.; Thompson, D.N.P. Intraoperative Neurophysiological Monitoring in Paediatric Chiari Surgery-Help or Hindrance? Childs Nerv Syst 2019, 35, 1769–1776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kawasaki, Y.; Uchida, S.; Onishi, K.; Toyokuni, M.; Okanari, K.; Fujiki, M. Intraoperative Neurophysiologic Monitoring for Prediction of Postoperative Neurological Improvement in a Child With Chiari Type I Malformation. J Craniofac Surg 2017, 28, 1837–1841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Krishnakumar, M.; Ramesh, V.; Goyal, A.; Srinivas, D. Utility of Motor Evoked Potential in Identification and Treatment of Suboptimal Positioning in Pediatric Craniovertebral Junction Abnormalities: A Case Report. A&A Practice 2020, 14, e01323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grossauer, S.; Koeck, K.; Vince, G.H. Intraoperative Somatosensory Evoked Potential Recovery Following Opening of the Fourth Ventricle during Posterior Fossa Decompression in Chiari Malformation: Case Report. JNS 2015, 122, 692–696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roser, F.; Ebner, F.H.; Liebsch, M.; Tatagiba, M.S.; Naros, G. The Role of Intraoperative Neuromonitoring in Adults with Chiari I Malformation. Clinical Neurology and Neurosurgery 2016, 150, 27–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heffez, D.S.; Golchini, R.; Ghorai, J.; Cohen, B. Operative Findings and Surgical Outcomes in Patients Undergoing Chiari 1 Malformation Decompression: Relationship to the Extent of Tonsillar Ectopia. Acta Neurochir (Wien) 2020, 162, 1539–1547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schaefer, J.; Atallah, E.; Tecce, E.; Thalheimer, S.; Harrop, J.; Heller, J.E. Utility of Intraoperative Neuromonitoring for Decompression of Chiari Type I Malformation in 93 Adult Patients. Journal of Neurosurgery 2022, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di, X. Endoscopic Suboccipital Decompression on Pediatric Chiari Type I. Minim Invasive Neurosurg 2009, 52, 119–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shah, A.; Patil, A.; Vutha, R.; Thakar, K.; Goel, A. Recovery of Transcranial Motor Evoked Potentials After Atlantoaxial Stabilization for Chiari Formation: Report of 20 Cases. World Neurosurg 2019, 127, e644–e648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Milhorat, T.H.; Kotzen, R.M.; Capocelli, A.L.; Bolognese, P.; Bendo, A.A.; Cottrell, J.E. Intraoperative Improvement of Somatosensory Evoked Potentials and Local Spinal Cord Blood Flow in Patients with Syringomyelia. J Neurosurg Anesthesiol 1996, 8, 208–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milhorat, T.H.; Capocelli, A.L.; Kotzen, R.M.; Bolognese, P.; Heger, I.M.; Cottrell, J.E. Intramedullary Pressure in Syringomyelia: Clinical and Pathophysiological Correlates of Syrinx Distension. Neurosurgery 1997, 41, 1102–1110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pencovich, N.; Korn, A.; Constantini, S. Intraoperative Neurophysiologic Monitoring during Syringomyelia Surgery: Lessons from a Series of 13 Patients. Acta Neurochir (Wien) 2013, 155, 785–791, discussion 791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sánchez-Roldán, M.A.; Moncho, D.; Rahnama, K.; Santa-Cruz, D.; Lainez, E.; Baiget, D.; Chocron, I.; Gandara, D.; Bescos, A.; Sahuquillo, J.; et al. Intraoperative Neurophysiological Monitoring in Syringomyelia Surgery: A Multimodal Approach 2023. [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Z.; Qiu, Y.; Wang, B.; Yu, Y.; Qian, B.; Zhu, F. Abnormal Spreading and Subunit Expression of Junctional Acetylcholine Receptors of Paraspinal Muscles in Scoliosis Associated with Syringomyelia. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 2007, 32, 2449–2454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eule, J.M.; Erickson, M.A.; O’Brien, M.F.; Handler, M. Chiari I Malformation Associated with Syringomyelia and Scoliosis: A Twenty-Year Review of Surgical and Nonsurgical Treatment in a Pediatric Population. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 2002, 27, 1451–1455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hausmann, O.N.; Böni, T.; Pfirrmann, C.W.A.; Curt, A.; Min, K. Preoperative Radiological and Electrophysiological Evaluation in 100 Adolescent Idiopathic Scoliosis Patients. Eur Spine J 2003, 12, 501–506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Z.; Yan, H.; Han, X.; Jin, M.; Xie, D.; Sha, S.; Liu, Z.; Qian, B.; Zhu, F.; Qiu, Y. Radiological Features of Scoliosis in Chiari I Malformation Without Syringomyelia. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 2016, 41, E276–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tubbs, R.S.; Beckman, J.; Naftel, R.P.; Chern, J.J.; Wellons, J.C.; Rozzelle, C.J.; Blount, J.P.; Oakes, W.J. Institutional Experience with 500 Cases of Surgically Treated Pediatric Chiari Malformation Type I. J Neurosurg Pediatr 2011, 7, 248–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sha, S.; Zhu, Z.; Lam, T.P.; Sun, X.; Qian, B.; Jiang, J.; Cheng, J.C.Y.; Qiu, Y. Brace Treatment versus Observation Alone for Scoliosis Associated with Chiari I Malformation Following Posterior Fossa Decompression: A Cohort Study of 54 Patients. Eur Spine J 2014, 23, 1224–1231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tan, H.; Lin, Y.; Rong, T.; Shen, J.; Zhang, J.; Feng, E.; Jiao, Y.; Liang, J.; Li, Z. Surgical Scoliosis Correction in Chiari-I Malformation with Syringomyelia Versus Idiopathic Syringomyelia. J Bone Joint Surg Am 2020, 102, 1405–1415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shi, B.; Qiu, J.; Xu, L.; Li, Y.; Jiang, D.; Xia, S.; Liu, Z.; Sun, X.; Shi, B.; Zhu, Z.; et al. Somatosensory and Motor Evoked Potentials during Correction Surgery of Scoliosis in Neurologically Asymptomatic Chiari Malformation-Associated Scoliosis: A Comparison with Idiopathic Scoliosis. Clin Neurol Neurosurg 2020, 191, 105689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brinzeu, A.; Sindou, M. Functional Anatomy of the Accessory Nerve Studied through Intraoperative Electrophysiological Mapping. JOURNAL OF NEUROSURGERY 2017, 126, 913–921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giampiccolo, D.; Basaldella, F.; Badari, A.; Squintani, G.M.; Cattaneo, L.; Sala, F. Feasibility of Cerebello-Cortical Stimulation for Intraoperative Neurophysiological Monitoring of Cerebellar Mutism. Child’s Nerv. Syst. 2021, 37, 1505–1514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caldarelli, M.; Novegno, F.; Vassimi, L.; Romani, R.; Tamburrini, G.; Di Rocco, C. The Role of Limited Posterior Fossa Craniectomy in the Surgical Treatment of Chiari Malformation Type I: Experience with a Pediatric Series. J. Neurosurg. 2007, 106, 187–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barzilai, O.; Roth, J.; Korn, A.; Constantini, S. Letter to the Editor: Evoked Potentials and Chiari Malformation Type 1. J. Neurosurg. 2016, 1–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Author | Year | No. of cases |

Study type | Patient characteristics | SEP | MEP | BAEP | BR or CN mapping | Alarm criteria | Alerts | Findings | Conclusion |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Schaefer et al. [135] | 2022 | 93 | Retrospective | 17-76-y-o SYR= 53 |

93 | 92 | 83 | ― | Decreased SEP AMP by 50%, increased SEP LAT by 10%, or decreased MEP AMP by 50%. A significant change in BAEPs is a decrease in wave V AMP of 50% or an increase in wave V LAT by 1 msec, or total loss of waves (I, III, and V) | 1 (1.1%), which resolved spontaneously after 10 minutes in a patient who had concomitant stenosis as a result of pannus formation at C1–2 (suboccipital craniectomy and C1–2 laminectomy with DP) | TE was significantly associated with unmonitorable MEPs but not with unmonitorable SEPs or BAEPs. SYR characteristics were not significantly associated with unmonitorable MEPs, SEPs, or BAEPs. Cerebellar symptoms were associated with unmonitorable MEPs and BAEPs but not SEPs | PFD in CM1 may be performed safely without IONM. In patients with additional occipitocervical pathology, IONM should be left as an option to be assessed by the surgeon on a case-by-case basis |

| Giampiccolo et al. [151] | 2021 | T = 10 CM1 = 1 |

An exploratory and preliminary study of cerebello-cortical stimulation |

6–73-y-o 2 children |

― | 1 | ― | ― |

N

o MEP was evoked with direct cerebellar stimulation in any of the patients. Paired cortico-transcortical stimulation: M1 stimulation occurred after cerebellar stimulation at fixed intervals between 8 and 24 ms. They observed significant modulation of MEPs in 8/10 patients. 5 patients showed MEP inhibition, 1 patient MEP facilitation, and 2 patients showed both conditions at different interstimulus intervals |

Electrical conditioning stimuli delivered to the exposed cerebellar cortex (cStim) alone did not produce any MEP. cStim preceding Tc Stim produced a significant inhibition at 8 ms (P <0.0001). This inhibition is likely the product of activity along the cerebello-dento-thalamo-cortical pathway | The authors show that monitoring efferent cerebellar pathways to the motor cortex is feasible in intraoperative settings. This study has promising implications for pediatric posterior fossa surgery to preserve the cerebello-cortical pathways and thus prevent cerebellar mutism | |

| Heffez et al. [134] | 2020 | 488 | Observational, prospective | > 18-y-o They divided patients into four groups depending on the position of the cerebellar tonsils: GR 1: 0-3 mm GR 2: 3-5 mm GR 3: 5-10 mm GR 4: > 10 mm They included some patients with tethered cord in GR 4 (CM2?) |

― | ― | 488 | ― | Any improvement or worsening was defined as a change of at least 0.1 msec from their initial BL | A reduction in III-V IPL of at least 0.1 msec was observed in 35-49% of patients | Reduction in III–V IPL was observed towards completing intradural dissection or during DP, with no statistical difference between groups | The observed reduction in IPLs indicates that even with minimal TE, there may be impairment of the function of at least one pathway within the brainstem similar to that seen with much more extreme TE and that this impairment improves after brainstem decompression |

| Krishnakumar et al. [131] | 2020 | 1 | Case report | 13-y-o ♂ with atlantooccipital dislocation, BI, hypoplastic C1 arch, and CM1 |

1 | 1 | ― | ― | N/A | After the prone position, there was a loss of MEP in all four limbs, so neck flexion was reduced by 15°, which reverted the changes in MEP. Following screw tightening, there was a loss of MEP in both upper limbs, and the decision to perform a C1 arch excision was made; MEP reappeared in both upper limbs following this step | IONM can contribute to safe surgical positioning and performance. It is essential for the team involved to promptly identify and rectify any changes in neuronal, structural, and vascular integrity to help minimize neurologic sequelae | |

| Shi et al. [149] | 2020 | 270 | Retrospective & case-matched subgroup analysis | Scoliosis surgery 60 asymptomatic CMS patients (48 presented with SYR) vs 210 IS patients. Case-matched patients: 60 CMS vs. 60 IS. -PFD was performed 8–12 months before correction surgery in whole patients with SYR |

270 | 258 | ― | ― | Absent SEPs, UNIL or BIL prolonged LAT. LAT normalized with body height and > 2.5 SD (P37 LAT = 0.277*height −7.144, SD = 1.071). And asymmetric LAT when interside difference of LAT or AMP > 2.5 SD of normal control |

In terms of SEP LAT and AMP as well as MEP amplitude, no significant difference was found between CMS and total IS patients. There was no significant difference in SEP LAT and AMP and MEP AMP between CMS and matched IS patients. The CMS patients with SYR were correlated with lower SEPs amplitudes |

Neurologically asymptomatic CMS patients showed similar absolute values of IONM, including SEP LAT and AMP, and MEP AMP as compared with IS patients. The SYR in CMS patients indicated more severe curvature and a lower SEP AMP even after PFD | |

| Tan et al. [148] | 2020 | 42 | Retrospective & case-matched | Scoliosis surgery 21 patients with SCOL secondary to CM1 and SYR matched with 21 patients with SCOL secondary to idiopathic SYR |

― | 42 | ― | ― | -Obvious MEP degeneration was defined as 40% to 80% MEP AMP loss. -Significant MEP loss with monitoring alerts was defined as >80% of MEP loss associated with high-risk surgical maneuvers |

-Obvious MEP degeneration in 5 patients -Significant MEP loss in none |

There were no differences in the successful recording of MEP BL | Although patients with CM1 had longer SYR, their IONM signals during the operation were similar to those of the SCOL secondary to idiopathic SYR group. The potential risk of SCOL surgery in patients with SYR-associated SCOL should not be ignored |

| Shah et al. [137] | 2019 | 20 | Observational, prospective | 7-52-y-o, with CM1 that were surgically treated by atlantoaxial stabilization surgery. No bone, dural, or neural decompression |

20 | 20 | ― | ― | N/A | All patients had immediate intraoperative improvement in their BL MEPs after fixation was completed, ranging from 20% to 35%. No change in SEPs during the entire surgery in any of the patients |

The improvement in electrophysiologic parameters after atlantoaxial fixation fortifies their belief that atlantoaxial instability is the cause of Chiari formation and atlantoaxial fixation is the treatment | |

| Rasul et al. [129] | 2019 | 37 | Retrospective | < 17-y-o undergoing PFD for CM1 SYR = 24 SCOL = 13 |

33 | ― | 19 | ― | N/A | SEP → 2/33 ↑AMP 18/33 ↓ AMP 31/33 ↓ LAT BAEP→ 13/19 ↓ LAT 4/19 ↑ LAT |

SEP LAT ↓ in 93.9% of patients. More than 50% of patients had a ↓ in their SEP AMP BAEPs ↓ in 68.4% of patients |

PFD for CM1 is associated with changes in SEPs and BAEPs. However, the authors were unable to identify a definite link between clinical outcomes and IONM |

| Brînzeu and Sindou [150] |

2017 | T=49 22 CM1 |

Research study about the functional anatomy of the accessory nerve (XI CN) studied through IONM (mapping) |

20-73-y-o Far-lateral decompression of the tonsils at the FM in addition to posterior decompression, followed by a Y-shaped dural incision without opening the arachnoid |

Rootlet and cranial root stimulation in the majority of CM1 patients | The CN XI pair is organized around two components: a cranial root and a spinal root with several cervical rootlets. The cranial component contributes at least to the motor innervation of the larynx. The spinal component largely contributes to the innervation of the sternocleidomastoid and trapezius with a precise craniocaudal myotopic organization; the rootlets destined to innervate the sternocleidomastoid are more cranial |

||||||

| Kawasaki et al. [130] | 2017 | 1 | Case report | Symptomatic 7-y-o boy who underwent surgery of PFD with tonsillectomy and DP for CM1 with cervicomedullary compression + pre-SYR state at the C3-4 dorsal spinal cord | 1 | 1 | ― | ― | Changes of 50% in AMP and 10% in LAT from the BL value were considered significant for intraoperative use both in MEPs and SEPs | MEPs improved, showing ↑ AMP and ↓ LAT after craniotomy and durotomy, whereas SEPs improved only after durotomy | The improvement in MEPs and SEPs observed during decompression may be a good indicator for the prediction of the clinical improvement seen postoperatively | |

| Roser et al. [133] | 2016 | 39 | Retrospective | 13–65-y-o patients with CM1, undergoing suboccipital decompression and DP SYR = 33 |

38 | 33 | ― | ― | N/A |

SEP→ Deterioration during positioning 2/39, ↑ >10% LAT in 4 recordings, ↓ or ↑ >50% AMP in 9 and 10 recordings; MEP→ Deterioration during positioning 2/39, ↓ and ↑ > 10% LAT in 11 and 10 recordings, ↓ and ↑ > 50% AMP in 14 and 17 recordings |

There were no significant differences in absolute BL and final LAT and AMP of MN and PTN SEPs. There were no significant differences in absolute BL and final LAT and AMP of APB and TA MEPs |

IONM during primary treatment of CM1 shows only subtle nonsignificant changes in SEPs and MEPs without clinical correlation during suboccipital decompression |

| Barzilai et al. [153] | 2015 | 22 | Retrospective | 21 pediatric patients aged 2–17-y-o with CM1 SYR =18 PFD + C1 (C2/C3) laminectomy (22 surgeries) |

22 | 22 | ― | ― | N/A | IONM position-related alarms in 3 patients: 1 attenuation only of SEPs, 1 attenuation only of MEPs, and one attenuation in SEPs and MEPs together | None of the 3 patients displayed new immediate postoperative deficits |

Multimodality IONM can be helpful in PFD surgery, particularly during patient positioning. MEP attenuations may occur independently of SEPs. The clinical implications of these monitoring alerts have yet to be defined |

| Grossauer et al. [132] | 2015 | 1 | Case report | A 32-y-o woman who underwent surgery for CM1 associated with extensive cervicothoracic SYR | 1 | ― | ― | ― | A change of 50% in N20 amplitude from the BL value and a change of 10% in N20 LAT from the BL value | From positioning to completion of dura opening, there were no significant changes in MN SEP. A few minutes after opening the IV ventricle, they observed a 230% ↑ in the N20 AMP and an 8% ↓ in the N20 LAT compared with the BL value. This clear SEP improvement persisted until the end of the operation |

Conduction improvement in SEPs during CM1 decompression may not always occur after bone decompression or DP. It may also happen after opening the IV ventricle and establishing CSF flow at the level of the CVJ. Additional studies are needed to adapt the degree of decompression to each CM1 patient based on IONM data | |

| Kennedy et al. [127] | 2015 | 156 | Retrospective | 7-20.6-y-o Suboccipital decompression without dural opening SYR = 68 SCOL = 18 m Cobb angle= 25° |

156? | ― | 156? | ― | N/A | N/A | BAEPs and SEPs were performed before (supine) and after (prone) positioning and throughout the surgery. 121 (78%) of patients exhibited at least UNIL improvement in I–V IPL after bony decompression, with a mean improvement of 0.26 msec. The remaining 34 patients had stable BAEPs throughout the surgery. Once a preoperative neck position was established in the prone position with SEPs unchanged from BL, there were no adverse changes in the SEPs during any patient’s surgery |

|

| Pencovich et al. [140] | 2013 | T= 13 CM1= 6 |

SYR Surgery 4-61-y-o →1 CM1= Syrinx drainage and PFD. Level T4-T5 →5 CM1= Syringo-subarachnoid shunt SYR approach: →4 midline →2 DREZ |

6 | 6 | ― | ― | SEP alert criteria included non-linear AMP ↓ beyond 50 % or LAT ↑ of over 10 %. Alert criteria for MEP were significant changes, including sudden attenuation beyond 85 % AMP in at least two reproducible traces after ruling out technical and anesthetic considerations |

In one, absent right leg MEP BL signal. While draining the SYR before PFD, severe attenuation of left leg MEP data was noted upon midline approach to the SYR. The catheter was subsequently removed, and the PFD was completed without SYR drainage. New neurologic deficit: Transient worsening of right hemiparesis with gradual improvement over a few days | This study demonstrates the reversibility of intraoperative neurological damage identified by IONM. An immediate response resulted in rapid recovery of cord functionality | Data collected in this study support routine usage of IONM in SYR surgeries. IONM can inform the surgeon of potential intraoperative threats to the functional integrity of the spinal cord, providing a helpful adjunct to spinal cord surgeries for the treatment of SYR. More extensive prospective studies are required to conclusively show that using IONM in these operations is indeed advantageous. The first study to specifically address the benefits of multimodality IONM during SYR surgery |

|

| Chen et al. [126] | 2012 | 13 | 2-17-y-o Suboccipital craniotomy for symptomatic CM1. In 3, the bone flap was not replaced (craniectomy), and in 9 cases, it was (craniotomy) SYR = 3 |

12 | ― | 9 | ― | N/A | MN or PTN SEP LAT improved in all patients. BAEPs improved in 8 patients. No significant SEP or BAEP deterioration was seen |

Improvements in neurophysiological parameters were sustained for the duration of the procedure. The interaction terms of the ANOVA were insignificant at the α =0.05 level | IONM may be used to perform suboccipital decompression in a step-by-step fashion, enlarging the craniectomy or adding additional procedures (laminectomy, DP) until positive changes are observed | |

| Di [136] | 2009 | 26 | Endoscopic suboccipital decompression 18 months-16-y-o 0° and 30° endoscopes were adapted to perform the procedure of suboccipital craniectomy and upper cervical laminectomies SYR = 5 SCOL = 1 |

11 | ― | ― | ― | SEPs were monitored throughout the entire procedure for the first 11 patients, and it was then discontinued due to lack of significant benefit for the patients |

SEP is still necessary, especially for the beginners of this procedure, to preclude the development of intraoperative spinal cord injury | |||

| Zamel et al. [124] | 2009 | 80 | Retrospective | 2-36-y-o Group A: PFD Group B: PFD+ DP SYR = 33 |

80 | ― | 80 | ― | BAEP waves I, III, and V were determined, and IPLs of waves I to III, III to V, and I to V were compared at BL, after positioning, immediately after bony decompression, and at closure | Neurophysiologic improvement in CCT was defined as a reduction in I-V IPL at closure compared with BL | A significant main interaction was found between the presence of SYR and reduction of I-V IPL from BL to decompression. Patients with SYR showed a significantly decreased I-V interval between BL and decompression compared with those without an SYR. No SEP findings were detailed |

PFD with bone removal alone significantly improves conduction time in most pediatric patients with CM1. DP allowed for a further but slight improvement in conduction time in only 20% of patients, beyond that achieved by decompression alone. None of the patients had any significant worsening of their BAEPs that would have alerted the neurosurgeon to modify the course of the surgery |

| Kim et al. [125] | 2004 |

11 | Retrospective | 1.5–17-y-o Significant BI and CM1 They underwent a novel treatment method involving decompression, manual reduction, and posterior instrumentation-augmented fusion. SYR= 3 |

11 | ― | ― | ― | N/A | ― | SEPs remained stable in 10 cases and improved intraoperatively after decompression and manual reduction in 1 case. Immediately after reduction and fusion, SEPs in 10 patients improved significantly, and in one, remained unchanged from BL | |

| Anderson et al. [123] | 2003 | 11 | Observational, prospective | 3-19-y-oSuboccipital decompressive procedure with DPSYR = 6 | 11 | ― | 11 | ― | N/A | In one case, the left MN SEP dramatically deteriorated after turning the patient to the prone position with neck flexion. The patient was immediately repositioned in a neutral position, improving the left MN SEP.BL BAEPs were abnormal, withdelayed I–III IPLs bilaterally. On flexion, BAEPs remained at BL | BAEPs: Decreased I-V IPLs after bone decompression but not after dural opening, statistically significant (compared with BL in supine).SEP for both sides in 10 patients remained stable throughout the procedure | Suggests that, in pediatric CM1 patients, the maximum improvement in conduction through the brainstem occurs after bony decompression and division of the atlantooccipital membrane rather than after dural opening. BAEPs and SEPs indicate that these patients are at risk for neurologic injury during operative positioning with neck flexion |

| Milhorat et al. [139] | 1997 | T=3221 CM1 | 5-72-y-o In SYR with CM1: Patients with CM1 underwent suboccipital craniectomies without opening the dura + SYR shunting procedures | 21 | ― | ― | ― | N/A | Eight patients had normal SEPs, and 6 had SEP abnormalities that were unchanged 30 minutes after SYR decompression. In 18 of 24 patients with pre-drainage abnormalities, there was a slight but consistent ↓ N20 LAT and less consistent ↑ of N20 AMP | Significant correlation between SEP findings and SYR morphology: Of 8 patients with normal SEPs, 6 had central core cavities, and 2 had central cavities that extended paracentrally. These types of cavities were more likely than eccentric cavities to be associated with SEP improvements after shunting (Pearson Χ2 = 6.47, P = 0.039) | The improvement in N20 LAT is indirect evidence of preexisting long tract compression, whereas improvements in N20 amplitudes were presumably caused by the decompression of perisyrinx neurons. These conclusions were less certain for patients with CM1 in whom SEP improvements may have been caused, in part, by decompression of the cerebellar hernia | |

| Milhorat et al. [138] | 1996 | T=1311 CM1 | 12-72-y-o In SYR with CM1: PFD and SYR shunt to the PF cisterns (syringo-cisternostomy) | 11 | ― | ― | ― | Continuous BL values recorded2-3 h before SYR shunting were compared with values obtained 30 min after shunting.SEP data were analyzed by the paired t-test | Bilateral MN SEPs: 30 min after SYR decompressiondemonstrated a significant ↓ N20 LAT and nonsignificant ↑ N20 AMP | Findings suggest that distended spinal cord cavities can produce regional ischemia possibly reflected by SEP abnormalities and reversed by SYR decompression. Preliminary, the IONM of SEPs can provide useful information during surgical procedures for SYR | ||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).