Submitted:

31 July 2023

Posted:

02 August 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

Statistical analysis

Ethical approval

3. Results

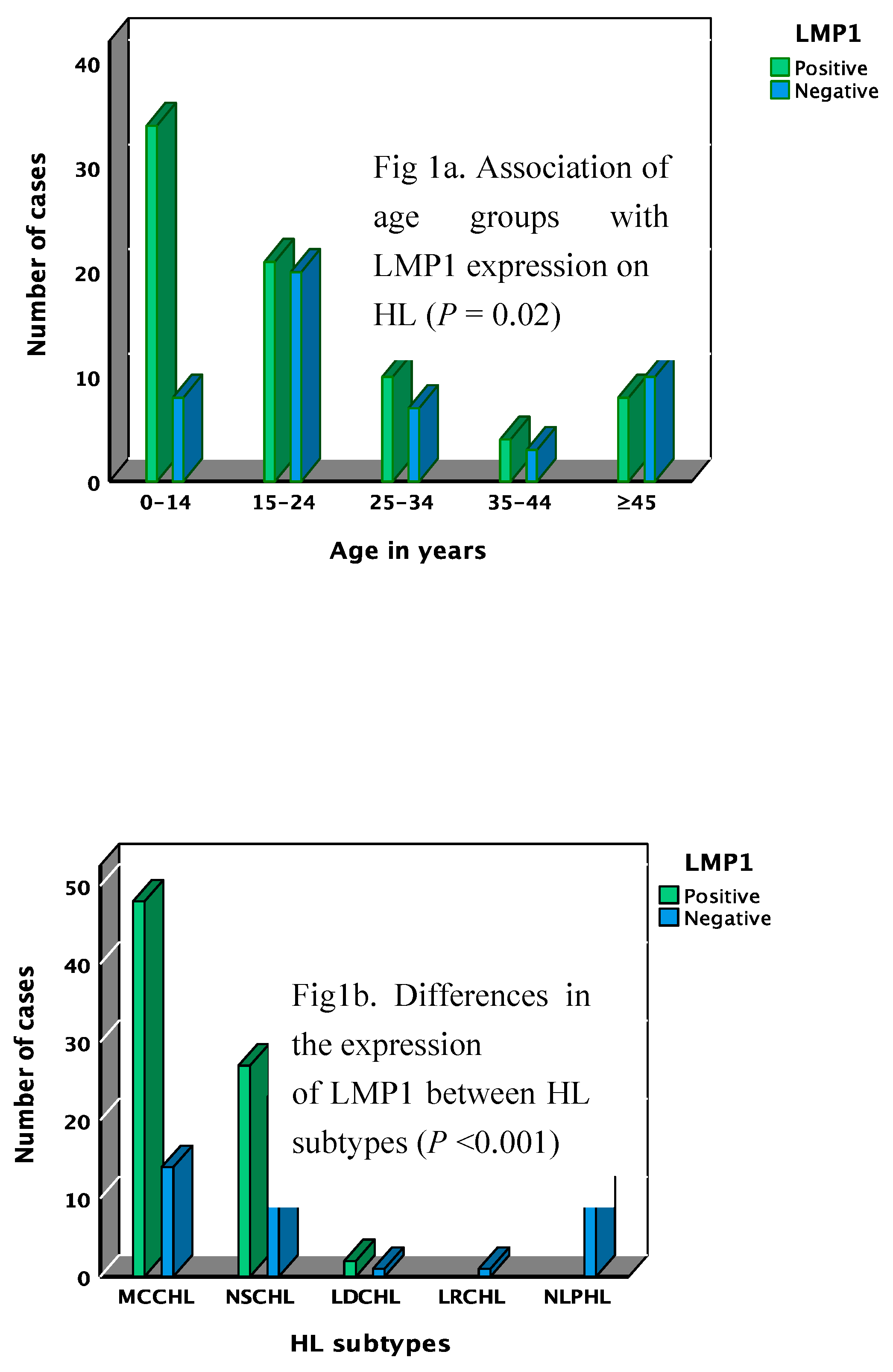

Detection of LMP1/EBER in tumor cells

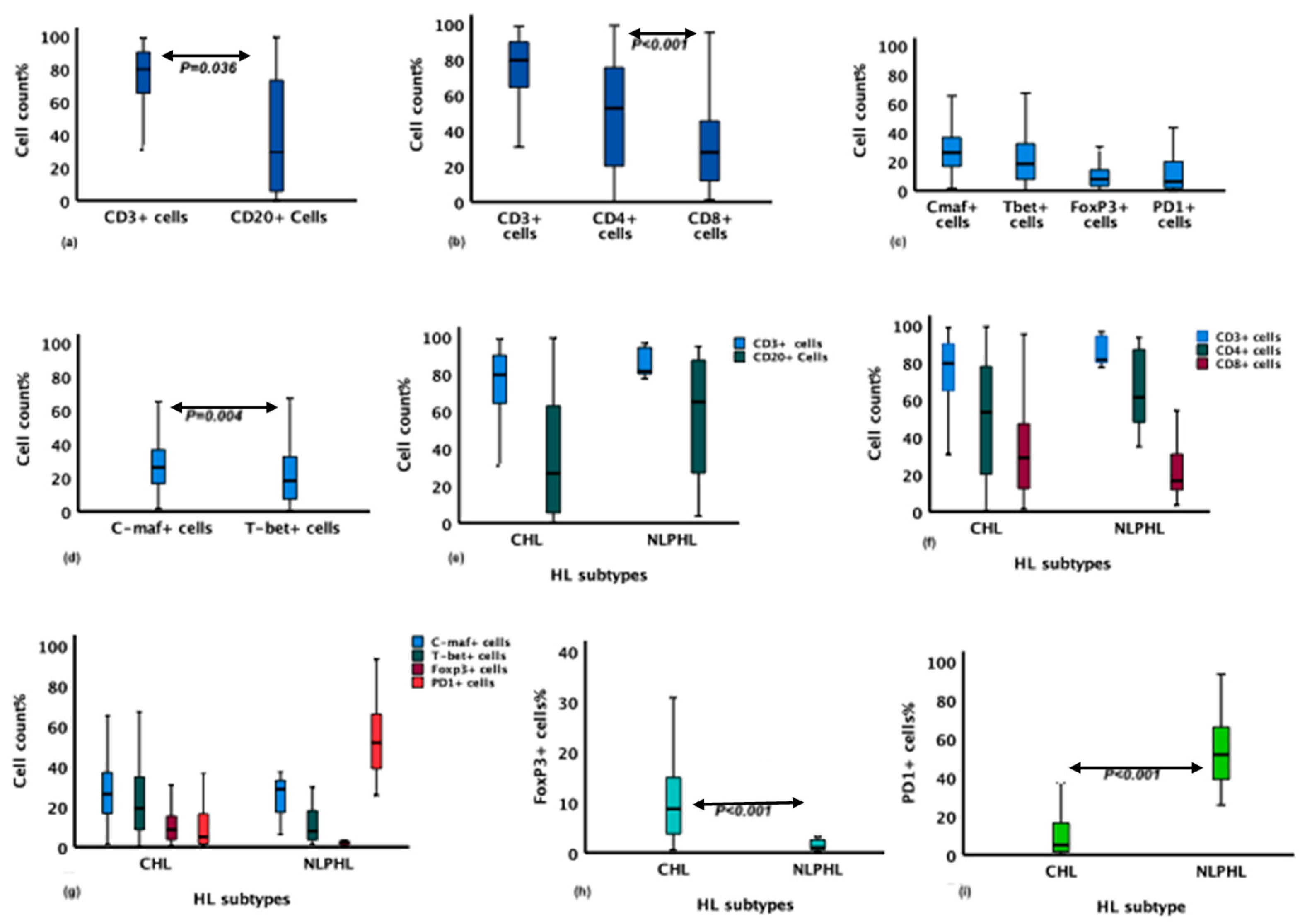

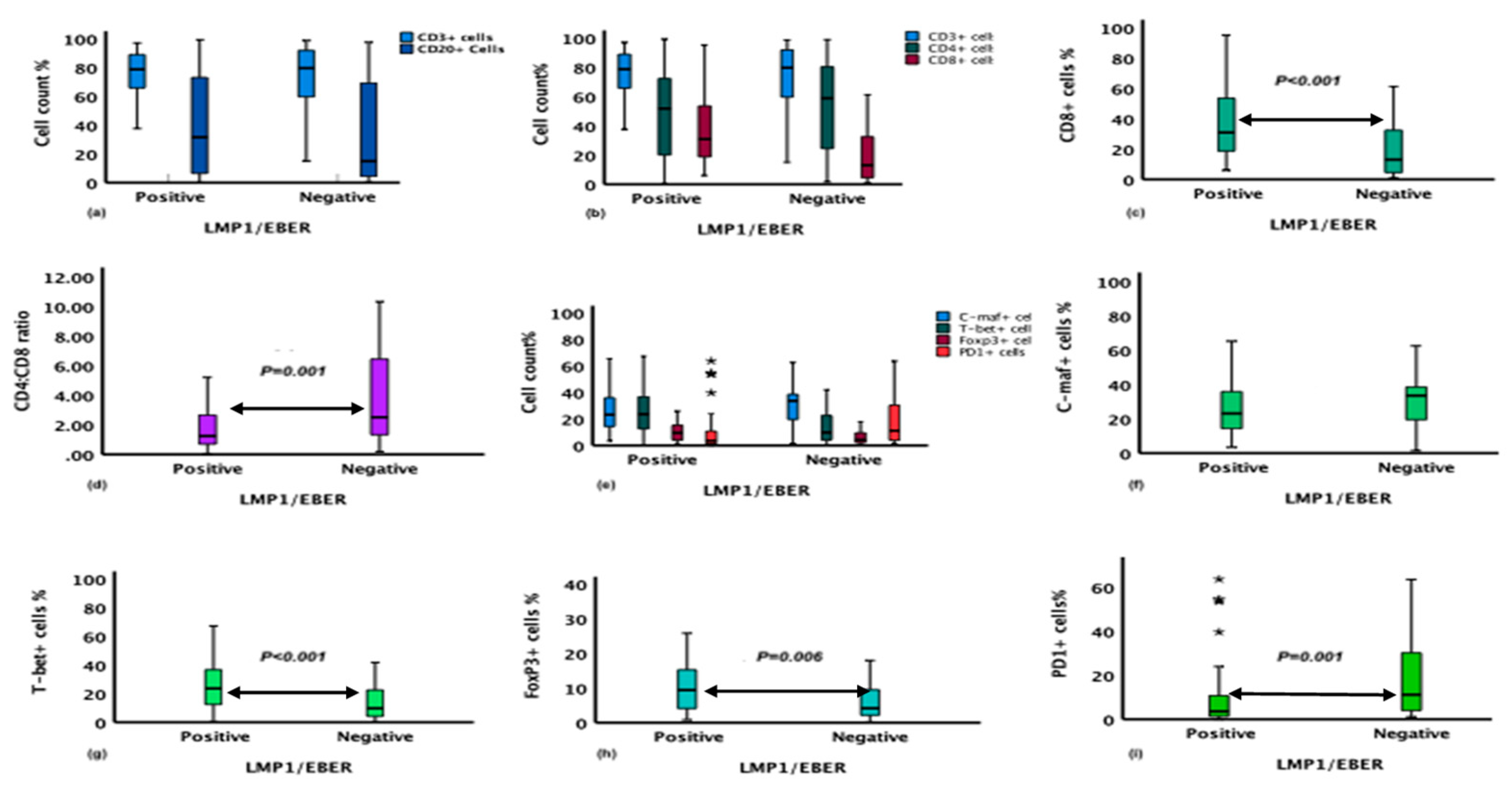

The association of the immune cells in the microenvironment of HL with clinicopathological features

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Thorley-Lawson, D.A.; Gross, A. Persistence of the Epstein–Barr virus and the origins of associated lymphomas. New England Journal of Medicine 2004, 350, 1328–1337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fitzmaurice, C.; Allen, C.; Barber, R.M.; Barregard, L.; Bhutta, Z.A.; Brenner, H.; Dicker, D.J.; Chimed-Orchir, O.; Dandona, R.; Dandona, L. Global, regional, and national cancer incidence, mortality, years of life lost, years lived with disability, and disability-adjusted life-years for 32 cancer groups, 1990 to 2015: a systematic analysis for the global burden of disease study. JAMA oncology 2017, 3, 524–548. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Biggar, R.J.; Henle, W.; Fleisher, G.; Böcker, J.; Lennette, E.T.; Henle, G. Primary Epstein-Barr virus infections in African infants. I. Decline of maternal antibodies and time of infection. International journal of cancer 1978, 22, 239–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, J.I. Epstein–Barr virus infection. New England journal of medicine 2000, 343, 481–492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gopal, S.; Wood, W.A.; Lee, S.J.; Shea, T.C.; Naresh, K.N.; Kazembe, P.N.; Casper, C.; Hesseling, P.B.; Mitsuyasu, R.T. Meeting the challenge of hematologic malignancies in sub-Saharan Africa. Blood, The Journal of the American Society of Hematology 2012, 119, 5078–5087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, C.M.; Kelly, J.Y.; Mbulaiteye, S.M.; Hildesheim, A.; Bhatia, K. The extent of genetic diversity of Epstein-Barr virus and its geographic and disease patterns: a need for reappraisal. Virus research 2009, 143, 209–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomas, R.; Re, D.; Zander, T.; Wolf, J.; Diehl, V. Epidemiology and etiology of Hodgkin's lymphoma. Annals of oncology 2002, 13, 147–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dinand, V.; Dawar, R.; Arya, L.S.; Unni, R.; Mohanty, B.; Singh, R. Hodgkin’s lymphoma in Indian children: prevalence and significance of Epstein–Barr virus detection in Hodgkin’s and Reed–Sternberg cells. European Journal of Cancer 2007, 43, 161–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glaser, S.L.; Lin, R.J.; Stewart, S.L.; Ambinder, R.F.; Jarrett, R.F.; Brousset, P.; Pallesen, G.; Gulley, M.L.; Khan, G.; O'Grady, J. Epstein-Barr virus-associated Hodgkin's disease: epidemiologic characteristics in international data. International journal of cancer 1997, 70, 375–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, K.C.; Chen, P.C.H.; Jones, D.; Su, I.J. Changing patterns in the frequency of Hodgkin lymphoma subtypes and Epstein–Barr virus association in Taiwan. Cancer science 2008, 99, 345–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Salam, S.; John, A.; Daoud, S.; Chong, S.M.; Castella, A. Expression of Epstein–Barr virus in Hodgkin lymphoma in a population of United Arab Emirates nationals. Leukemia & lymphoma 2008, 49, 1769–1777. [Google Scholar]

- Castillo, J.J.; Beltran, B.E.; Miranda, R.N.; Paydas, S.; Winer, E.S.; Butera, J.N. Epstein-Barr virus–positive diffuse large B-cell lymphoma of the elderly: what we know so far. The Oncologist 2011, 16, 87–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mwakigonja, A.R.; Kaaya, E.E.; Heiden, T.; Wannhoff, G.; Castro, J.; Pak, F.; Porwit, A.; Biberfeld, P. Tanzanian malignant lymphomas: WHO classification, presentation, ploidy, proliferation and HIV/EBV association. BMC Cancer 2010, 10, 344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Swerdlow, S.H.; Campo, E.; Pileri, S.A.; Harris, N.L.; Stein, H.; Siebert, R.; Advani, R.; Ghielmini, M.; Salles, G.A.; Zelenetz, A.D.; et al. The 2016 revision of the World Health Organization classification of lymphoid neoplasms. Blood 2016, 127, 2375–2390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kusuda, M.; Toriyama, K.; Kamidigo, N.O.; Itakura, H. A comparison of epidemiologic, histologic, and virologic studies on Hodgkin's disease in western Kenya and Nagasaki, Japan. The American journal of tropical medicine and hygiene 1998, 59, 801–807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moskowitz, C.H.; Ribrag, V.; Michot, J.-M.; Martinelli, G.; Zinzani, P.L.; Gutierrez, M.; De Maeyer, G.; Jacob, A.G.; Giallella, K.; Anderson, J.W. PD-1 blockade with the monoclonal antibody pembrolizumab (MK-3475) in patients with classical Hodgkin lymphoma after brentuximab vedotin failure: preliminary results from a phase 1b study (KEYNOTE-013). Blood 2014, 124, 290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ansell, S.M.; Lesokhin, A.M.; Borrello, I.; Halwani, A.; Scott, E.C.; Gutierrez, M.; Schuster, S.J.; Millenson, M.M.; Cattry, D.; Freeman, G.J. PD-1 blockade with nivolumab in relapsed or refractory Hodgkin's lymphoma. New England Journal of Medicine 2015, 372, 311–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steidl, C.; Connors, J.M.; Gascoyne, R.D. Molecular pathogenesis of Hodgkin's lymphoma: increasing evidence of the importance of the microenvironment. Journal of Clinical Oncology 2011, 29, 1812–1826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ansell, S. Novel agents in the therapy of Hodgkin lymphoma. American Society of Clinical Oncology Educational Book 2015, 35, e479–e482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marshall, N.A.; Christie, L.E.; Munro, L.R.; Culligan, D.J.; Johnston, P.W.; Barker, R.N.; Vickers, M.A. Immunosuppressive regulatory T cells are abundant in the reactive lymphocytes of Hodgkin lymphoma. Blood 2004, 103, 1755–1762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greaves, P.; Clear, A.; Owen, A.; Iqbal, S.; Lee, A.; Matthews, J.; Wilson, A.; Calaminici, M.; Gribben, J.G. Defining characteristics of classical Hodgkin lymphoma microenvironment T-helper cells. Blood, The Journal of the American Society of Hematology 2013, 122, 2856–2863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, R.; Sattarzadeh, A.; Rutgers, B.; Diepstra, A.; van den Berg, A.; Visser, L. The microenvironment of classical Hodgkin lymphoma: Heterogeneity by Epstein–Barr virus presence and location within the tumor. Blood cancer journal 2016, 6, e417–e417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Poppema, S.; van den Berg, A. Interaction between host T cells and Reed–Sternberg cells in Hodgkin lymphomas, Seminars in cancer biology, Elsevier, 2000, pp 345-350.

- Schreck, S.; Friebel, D.; Buettner, M.; Distel, L.; Grabenbauer, G.; Young, L.S.; Niedobitek, G. Prognostic impact of tumour-infiltrating Th2 and regulatory T cells in classical Hodgkin lymphoma. Hematological oncology 2009, 27, 31–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wherry, E.J.; Ha, S.-J.; Kaech, S.M.; Haining, W.N.; Sarkar, S.; Kalia, V.; Subramaniam, S.; Blattman, J.N.; Barber, D.L.; Ahmed, R. Molecular signature of CD8+ T cell exhaustion during chronic viral infection. Immunity 2007, 27, 670–684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ahmadzadeh, M.; Johnson, L.A.; Heemskerk, B.; Wunderlich, J.R.; Dudley, M.E.; White, D.E.; Rosenberg, S.A. Tumor antigen–specific CD8 T cells infiltrating the tumor express high levels of PD-1 and are functionally impaired. Blood, The Journal of the American Society of Hematology 2009, 114, 1537–1544. [Google Scholar]

- Yamamoto, R.; Nishikori, M.; Kitawaki, T.; Sakai, T.; Hishizawa, M.; Tashima, M.; Kondo, T.; Ohmori, K.; Kurata, M.; Hayashi, T. PD-1–PD-1 ligand interaction contributes to immunosuppressive microenvironment of Hodgkin lymphoma. Blood, The Journal of the American Society of Hematology 2008, 111, 3220–3224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nishimura, H.; Nose, M.; Hiai, H.; Minato, N.; Honjo, T. Development of lupus-like autoimmune diseases by disruption of the PD-1 gene encoding an ITIM motif-carrying immunoreceptor. Immunity 1999, 11, 141–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carbone, A.; Gloghini, A.; Cabras, A.; Elia, G. Differentiating germinal center-derived lymphomas through their cellular microenvironment. American journal of hematology 2009, 84, 435–438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muenst, S.; Hoeller, S.; Dirnhofer, S.; Tzankov, A. Increased programmed death-1+ tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes in classical Hodgkin lymphoma substantiate reduced overall survival. Human pathology 2009, 40, 1715–1722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aldinucci, D.; Gloghini, A.; Pinto, A.; De Filippi, R.; Carbone, A. The classical Hodgkin's lymphoma microenvironment and its role in promoting tumour growth and immune escape. The Journal of Pathology: A Journal of the Pathological Society of Great Britain and Ireland 2010, 221, 248–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adam, M.; Bekueretsion, Y.; Abubeker, A.; Tadesse, F.; Kwiecinska, A.; Howe, R.; Petros, B.; Jerkeman, M.; Gebremedhin, A. Clinical Characteristics and Histopathological Patterns of Hodgkin Lymphoma and Treatment Outcomes at a Tertiary Cancer Center in Ethiopia. JCO Global Oncology 2021, 7, 277–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, D.; Xiong, S.; Xiong, W.C. General introduction to in situ hybridization protocol using nonradioactively labeled probes to detect mRNAs on tissue sections. Methods Mol Biol 2013, 1018, 165–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Weinreb, M.; Day, P.J.; Niggli, F.; Green, E.K.; Nyong'o, A.O.; Othieno-Abinya, N.A.; Riyat, M.S.; Raafat, F.; Mann, J.R. The consistent association between Epstein-Barr virus and Hodgkin's disease in children in Kenya. Blood 1996, 87, 3828–3836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Enblad, G.; Sandvej, K.; Sundstrom, C.; Pallesen, G.; Glimelius, B. Epstein-Barr Virus Distribution in Hodgkin's Disease in an Unselected Swedish Population. Acta Oncologica 1999, 38, 425–429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Trimèche, M.; Bonnet, C.; Korbi, S.; Boniver, J.; de Leval, L. Association between Epstein-Barr virus and Hodgkin's lymphoma in Belgium: a pathological and virological study. Leuk Lymphoma 2007, 48, 1323–1331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ferressini Gerpe, N.M.; Vistarop, A.G.; Moyano, A.; De Matteo, E.; Preciado, M.V.; Chabay, P.A. Distinctive EBV infection characteristics in children from a developing country. International Journal of Infectious Diseases 2020, 93, 139–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Keresztes, K.; Miltenyi, Z.; Bessenyei, B.; Beck, Z.; Szollosi, Z.; Nemes, Z.; Olah, E.; Illes, A. Association between the Epstein-Barr Virus and Hodgkin’s Lymphoma in the North-Eastern Part of Hungary: Effects on Therapy and Survival. Acta Haematologica 2006, 116, 101–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cozen, W.; Katz, J.; Mack, T.M. Risk patterns of Hodgkin's disease in Los Angeles vary by cell type. Cancer Epidemiology and Prevention Biomarkers 1992, 1, 261–268. [Google Scholar]

- Cartwright, R.A.; Gurney, K.A.; Moorman, A.V. Sex ratios and the risks of haematological malignancies. British journal of haematology 2002, 118, 1071–1077. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shenoy, P.; Maggioncalda, A.; Malik, N.; Flowers, C.R. Incidence patterns and outcomes for hodgkin lymphoma patients in the United States. Adv Hematol 2011, 2011, 725219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, K.L.; Albújar, P.F.; Chen, Y.-Y.; Johnson, R.M.; Weiss, L.M. High Prevalence of Epstein-Barr Virus in the Reed-Sternberg Cells of Hodgkin’s Disease Occurring in Peru. Blood 1993, 81, 496–501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Glaser, S.L.; Jarrett, R.F. The epidemiology of Hodgkin's disease. Baillieres Clin Haematol 1996, 9, 401–416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nurieva, R.I.; Duong, J.; Kishikawa, H.; Dianzani, U.; Rojo, J.M.; Ho, I.; Flavell, R.A.; Dong, C. Transcriptional regulation of th2 differentiation by inducible costimulator. Immunity 2003, 18, 801–811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Atayar, Ç.; van den Berg, A.; Blokzijl, T.; Boot, M.; Gascoyne, R.D.; Visser, L.; Poppema, S. Hodgkin’s lymphoma associated T-cells exhibit a transcription factor profile consistent with distinct lymphoid compartments. Journal of clinical pathology 2007, 60, 1092–1097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Henry, M.; Buck, S.; Savaşan, S. Flow cytometry for assessment of the tumor microenvironment in pediatric Hodgkin lymphoma. Pediatric blood & cancer 2018, 65, e27307. [Google Scholar]

- Menéndez, V.; Solórzano, J.L.; Fernández, S.; Montalbán, C.; García, J.F. The Hodgkin Lymphoma Immune Microenvironment: Turning Bad News into Good. Cancers 2022, 14, 1360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daussy, C.; Damotte, D.; Molina, T.J.; Roussel, M.; Fest, T.; Varin, A.; Perrot, J.-Y.; Ouafi, L.; Merle-Béral, H.; Julia, P. CD4: CD8 T-cell ratio differs significantly in diffuse large B-cell lymphomas from other lymphoma subtypes independently from lymph node localization. Int Trends Immun 2013, 1, 45–48. [Google Scholar]

- Gunduz, E.; Sermet, S.; Musmul, A. Peripheral blood regulatory T cell levels are correlated with some poor prognostic markers in newly diagnosed lymphoma patients. Cytometry Part B: Clinical Cytometry 2016, 90, 449–454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chetaille, B.; Bertucci, F.; Finetti, P.; Esterni, B.; Stamatoullas, A.; Picquenot, J.M.; Copin, M.C.; Morschhauser, F.; Casasnovas, O.; Petrella, T. Molecular profiling of classical Hodgkin lymphoma tissues uncovers variations in the tumor microenvironment and correlations with EBV infection and outcome. Blood, The Journal of the American Society of Hematology 2009, 113, 2765–3775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duffield, A.S.; Ascierto, M.L.; Anders, R.A.; Taube, J.M.; Meeker, A.K.; Chen, S.; McMiller, T.L.; Phillips, N.A.; Xu, H.; Ogurtsova, A. Th17 immune microenvironment in Epstein-Barr virus–negative Hodgkin lymphoma: Implications for immunotherapy. Blood advances 2017, 1, 1324–1334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kieser, A.; Sterz, K.R. The Latent Membrane Protein 1 (LMP1). Curr Top Microbiol Immunol 2015, 391, 119–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liao, C.; Zhou, Q.; Zhang, Z.; Wu, X.; Zhou, Z.; Li, B.; Peng, J.; Shen, L.; Li, D.; Luo, X.; et al. Epstein-Barr virus-encoded latent membrane protein 1 promotes extracellular vesicle secretion through syndecan-2 and synaptotagmin-like-4 in nasopharyngeal carcinoma cells. Cancer Sci 2020, 111, 857–868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kis, L.L.; Takahara, M.; Nagy, N.; Klein, G.; Klein, E. Cytokine mediated induction of the major Epstein–Barr virus (EBV)-encoded transforming protein, LMP-1. Immunology Letters 2006, 104, 83–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Assis, M.C.; Campos, A.H.; Oliveira, J.S.; Soares, F.A.; Silva, J.M.; Silva, P.B.; Penna, A.D.; Souza, E.M.; Baiocchi, O.C. Increased expression of CD4+ CD25+ FOXP3+ regulatory T cells correlates with Epstein–Barr virus and has no impact on survival in patients with classical Hodgkin lymphoma in Brazil. Medical oncology 2012, 29, 3614–3619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morales, O.; Mrizak, D.; François, V.; Mustapha, R.; Miroux, C.; Depil, S.; Decouvelaere, A.V.; Lionne-Huyghe, P.; Auriault, C.; de Launoit, Y. Epstein–Barr virus infection induces an increase of T regulatory type 1 cells in Hodgkin lymphoma patients. British journal of haematology 2014, 166, 875–890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W.-t.; Zhu, G.-l.; Xu, W.-q.; Zhang, W.; Wang, H.-z.; Wang, Y.-b.; Li, Y.-x. Association of PD-1/PD-L1 expression and Epstein-–Barr virus infection in patients with invasive breast cancer. Diagnostic Pathology 2022, 17, 61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Antigen | Clone | Dilution | Supplier | Antigen-retrieval method |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CD20cy | L26 | 1:500 | Agilent/DAKO | PT-Link pH9 |

| CD3 | A0452 | 1:200 | Agilent/DAKO | PT-Link pH9 |

| LMP1 | CS1-4 | 1:100 | CellMarque | PT-Link pH9 |

| CD4 | 4B12 | 1:60 | Agilent/DAKO | PT-Link pH9 |

| CD8 | C8/1244B | 1:100 | Agilent/DAKO | PT-Link pH9 |

| FoxP3 | 236A/E7 | 1:200 | Abcam | PT-Link pH9 |

| T-bet | EPR9302 | 1:500 | Abcam | PT-Link pH9 |

| C-maf | EPR16484 | 1:200 | Abcam | PT-Link pH9 |

| PD-1 | NAT105 | 1:100 | CellMarque | 2100 Retiever pH6 |

| EBV Marker/ Characteristics | Wald x2(1) | COR** (95% CI) P* | Wald x2(1) | Adj OR*** (95% CI), P* |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| N = 126 | ||||

| LMP1 | ||||

| Age | 4.2 | 1.02 (1.001-1.06), 0.03 | 3.03 | 1.03 (0.9-1.05), 0.08 |

| Sex | 6.3 | 3 (1.3-7), 0.012 | 4.9 | 2.9 (1.1-7), 0.026 |

| CHL subtypes§ | 5.05 | 2 (1.09-3.6), 0.025 | 6.6 | 2.3 (1.2-4.2), 0.01 |

| Biomarker/HL characteristics | Count/mm2 | Perecent/mm2 |

|---|---|---|

| Adj OR (95% CI), P* | Adj OR (95%CI), P* | |

| CD8 | ||

| LMP1 | 2.3 (183-2625), 0.025 | 2.7 (2-21), 0.012 |

| Sex | -1.4 (-2310-397), 0.2 | -1.5 (-18-2), 0.1 |

| CHL subtype§ | -1.3 (-1351-301), 0.2 | -0.9 (-9-3), 0.4 |

| FOXP3 | ||

| LMP1 | 3 (237-1094), 0.003 | 2.1 (0.16-7), 0.04 |

| Sex | 2.2 (47-958), 0.03 | 2.3 (0.5-8), 0.026 |

| CHL subtypes§ | -0.9 (-414-148), 0.4 | -0.3 (-2.6-1.9), 0.7 |

| Age | 1.8 (-1-27), 0.08 | 1.6 (-0.02-0.2), 0.1 |

| T-bet | ||

| LMP1 | 3.5 (709-2578), <0.001 | 4 (7-21), <0.001 |

| Age | 2.3 (5-70), 0.021 | 2.5 (0.07-0.56), 0.014 |

| PD1 | ||

| LMP1 | -2.3 (-2030-(-162)), 0.02 | -2.3 (-15-(-1)), 0.02 |

| Age | 1.8 (-2-60), 0.07 | 1.2 (-0.1-0.4), 0.3 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).