1. Introduction

The objective of this study is to progress in the understanding and the modeling of polymers rheology during their crystallization and melting stages. It focuses at this step on the initial zone of linear viscoelastic behavior. The targeted applications are those that do not involve significant flow such as welding or, even more, the additive manufacturing of semi-crystalline polymers. This paper presents the first step, which includes an experimental study, as well as the proposal and the demonstration of the feasibility of a phenomenological approach that can be easily used.

Indeed, and for example, the recent developments in additive manufacturing of semi-crystalline polymers and its modeling [

1] renew the interest in the analysis of the impact of crystallization on rheology at low strain. In Laser Powder Bed Fusion (LPBF) as well as in fused deposition modeling (FDM), after being extruded the polymer crystallizes under more static conditions and under slow cooling rates in additive manufacturing, unlike conventional processes, where the main effects interacting with crystallization are high cooling rates, shear, and pressure effects [

2]. Additionally, fusion-crystallization cycles can occur for each deposited layer. The question that arises is more about the impact of a partial crystallization on the rheology rather than the effect of the flow on the kinetics of crystallization.

These two phase-changes (melting and crystallization) are completely asymmetrical. Indeed, crystallization is a process broken down into two stages: nucleation and growth of spherulites, while fusion is a more diffuse process where intra-spherulitic lamellae gradually disappear. Therefore, the same global crystallization ratio hides two different microstructures when the polymer crystallizes and when it melts. In one case, one will observe spherulites of equivalent crystallinity ratio, isolated in an amorphous "matrix". In the other, a contiguous structure of spherulites whose crystallinity decreases. Modeling can therefore no longer stop at the estimate of a crystallinity ratio using overall kinetics theories.

The current state of modeling mechanical and rheological properties of semi-crystalline polymers does not yet allow to consider a complete modeling of all these processes within the framework of the different techniques covered by additive manufacturing. Therefore, all experimental analyzes are useful for determining the physical quantities to be considered. In parallel, a pragmatic modeling effort, even an approximate one, could make it possible to take advantage of the numerical codes available via simple adjustments.

In this study, we focused on the understandings needed for the deposit (resp. fusion)/consolidation steps of the layers in FDM (resp. LPBF) additive manufacturing techniques. In such a case, regarding the mechanical aspect, it can be assumed that mechanical solicitations globally stay in the viscoelastic range at low deformation. In any case, the important issues of residual stresses and warpage [

3] makes it necessary to improve knowledge in the visco-elastic properties during crystallization.

The present paper aims at describing some of these latter aspects, i.e., what can be experimentally observed regarding the linear visco-elastic properties of polymers during crystallization and melting under low cooling (resp. heating) rates or under isothermal conditions. As a first step, we did not consider the melting or the crystallization of an initially partially crystallized polymer.

Following studies reported in the literature [

4,

5,

6,

7,

8,

9], investigations combined scanning calorimetry (DSC), optical microscopy (OM) and oscillatory rotational rheometry in separate tests. Rheometry allowed to assess linear visco elasticity during phase changes. DSC and OM allowed to assess crystallization (resp. melting) kinetics and growth rates, respectively. Crystallization was thus analyzed in a classical way, for which we remind its main aspects below.

Since early works [

10,

11,

12,

13] the semi-crystalline microstructure of polymers is described as the periodic stacks of an amorphous phase embedded between crystalline lamellae. The latter presents folding of the chains on its surface. They are connected by tie molecules. The two phases are organized in a spherical superstructure, named spherulite, formed by branched radial stacks growing from a central nucleus.

The small thickness of the crystal (order of magnitude less than 100 Å) and the chain folding structure explain that the crystallization and melting temperatures are strongly dependent on external conditions: cooling rate and pressure. Three characteristic temperatures must then be defined: a crystallization temperature depending on the crystallization modes, a melting temperature depending on the previous conditions, and a thermodynamic equilibrium temperature

supposed to be characteristic of the infinite crystal [

14].

Most of the time, growth rates of radial stacks are modeled by the theory of Hoffman and Lauritzen which combines the effects of enthalpy and medium viscosity [

15,

16].

Despite this background, and from a practical point of view, crystallization during processing is most often described at a more macroscopic level, i.e., at the level of the so-called “overall crystallization kinetics” (although the above theories are sometimes used as ingredients). Indeed, the spherical superstructure fits perfectly into this type of approach, which aims to model the fraction of volume that will be absorbed in a medium due to the nucleation and growth of uniformly distributed spheres. The Hoffman growth rate is then assimilated to the growth rate of spherulites.

Numerous papers have been devoted over time to overall kinetics and their uses in different conditions. A summary can be found in [

17]. The most popular approach is that of Avrami [

18] [

19,

20] who corrected the work of Johnson and Mehl [

21]. However, independently, the Kolmogoroff approach [

22] as well as the Evans approach [

23] have led to equivalent formal results.

Basically, they differ only in their mathematical treatments but are based on the same assumptions. They were revisited to apply them under non uniform, non-isothermal and/or not-quiescent conditions and were validated thanks to numerical simulation (see in example general review in [

17]).

Applied to polymers, they allow the calculation of the evolution of the volume fraction transformed into spherulites by assuming that the spherulites are initiated on nuclei that are uniformly distributed and that they all grow at the same rate, which depends only on the temperature. Theories initially make no assumption on the external thermal conditions but are not easy to use in the general case. Thus, they are mainly used in their isothermal limit. Nakamura suggested that any cooling rate can be modeled using those isothermal parameters experimentally available [

24,

25]. Ozawa expressed Avrami's model in the case where the cooling rate is constant [

26]. This approach allows the identification of kinetics parameters in a wider range of temperatures than isothermal measurements (required in Nakamura's approach) and could also be used in case of a non-constant cooling rate [

27].

More recently, the differential approaches [

28,

29] have shown their effectiveness in the numerical modeling of the transformation but have not improved the basic assumptions.

In the present study, we used a slightly revisited Evans’ approach to address crystallization kinetics. The modifications are like that of Nakamura or Ozawa, anyway. The motivation was that Evans’ way [

23] of solving the problem allows to give some simple elements concerning spherulitic microstructure in addition to transformed volume fraction over time. This is explained in the theoretical section below. DSC allowed to estimated Evan’s parameters and characteristics temperatures. Optical microscopy allowed to estimate growth rate.

The rheological measurements focused on the complex shear modulus. Steady state must be avoided not to induce crystallization under shear. The isothermal crystallization temperature must be high enough to ensure that crystallization is not initiated during the cooling step. In case of non-isothermal measurements, the cooling rate must be low to ensure that the temperature in the sample remains uniform. Consequently, the range of temperatures and rates are quite restricted, as in any equivalent study reported in the literature. For polypropylene, a polymer most often used as a model material, the range of crystallization temperatures is between 145 and 130°C. The cooling rate did not exceed a few degrees per minute. Despite of that, no general correlation could be drawn between crystallization kinetics estimated from DSC measurements and rheological measurements. For example, the transformed volume fraction leading to a 10-fold viscosity increase reported in the literature varies from 2 % to 40 % [

4,

5,

6,

7,

8,

9]. So additional measurements are still of interest to enlighten that point. This justifies experimental work that is described in this paper.

Regarding the rheological analysis, the first idea could be to correlate the moduli or viscosity to the crystallinity ratio using mixing laws [

30]. Unfortunately, it is well known that crystallinity ratio alone does not allow to accurately model mechanical characteristics of polymers in a general manner. The inner morphology of the spherulite might be modelled and accounted for. Some attempts already exist within the frame of micromechanics that are based on simplified microstructure and that are most often restricted to an elastic behavior [

31,

32]. Recently, such kind of approach was coupled with a numerical simulation of spherulite growth to model elastic components as a function of crystallization [

33]. Nevertheless, the above developments still need some improvements and remain tricky to incorporate in an engineering modelling of additive manufacturing.

In consequence, the main purpose of the present study is to propose an alternative, and simple, model that could help as a first approximation of the role of crystallization and melting on storage and loss moduli. To achieve that point, some macroscopic parameters, related to the microstructure, and that can be deduced from DSC and OM analyses, are defined. They are correlated to rheological measurements in isothermal conditions and under constant cooling rates. Finally, a phenomenological mathematical fitting is proposed and validated. Therefore, cycle heating-cooling at constant rate in rotational rheometry can be reproduced.

The parameters we choose, aimed at representing the microstructure even though they cannot describe it precisely. First is the transformed volume fraction that is related to the amount of crystalline phase. The second represents the number of spherulites; the third one is related to the average radius of spherulites over time. The last parameter is chosen from Evans theory, to assess the level of impingement of spherulites. They are deduced from DSC analysis, and the growth rate only, i.e., the most easily available experimental data.

The paper first describes the theoretical framework, second the main results are presented, third the correlation between crystallization and rheological measurements are discussed. This allows to significantly enrich general knowledge and enlightens the reason for the huge discrepancy between results in previous literature.

In a last step the parameters are defined and argued, and the model is developed and validated.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Materials

For this study, isotactic PolyPropylene (iPP) pellets supplied by Sigma Aldrich were used. The supplier indicates a number average molecular weight and a mass average molecular weight .

To carry out analyzes, pellets were pressed into 1 mm thick disks. The protocol consisted of heating the pellets up to 220 °C in an aluminum mold placed in a hot press. After being at this temperature for 5 minutes, a pressure of approximatively 0.7 MPa was applied on the mold and held for an additional 5 minutes. Finally, while maintaining the pressure, the mold was cooled down to room temperature thanks to a water-cooling system. Accurate cooling rates inside the mold are not known; All the characterizations mentioned below were conducted with a step at high temperature to erase thermal history.

2.2. Differential Scanning Calorimetry

Differential Scanning Calorimetry (DSC) analyses were performed under nitrogen flow on a DSC 8500 manufactured by PerkinElmer. The sample weighted about 4 mg. These analyses were conducted to investigate crystallization kinetics under both non- isothermal and isothermal conditions.

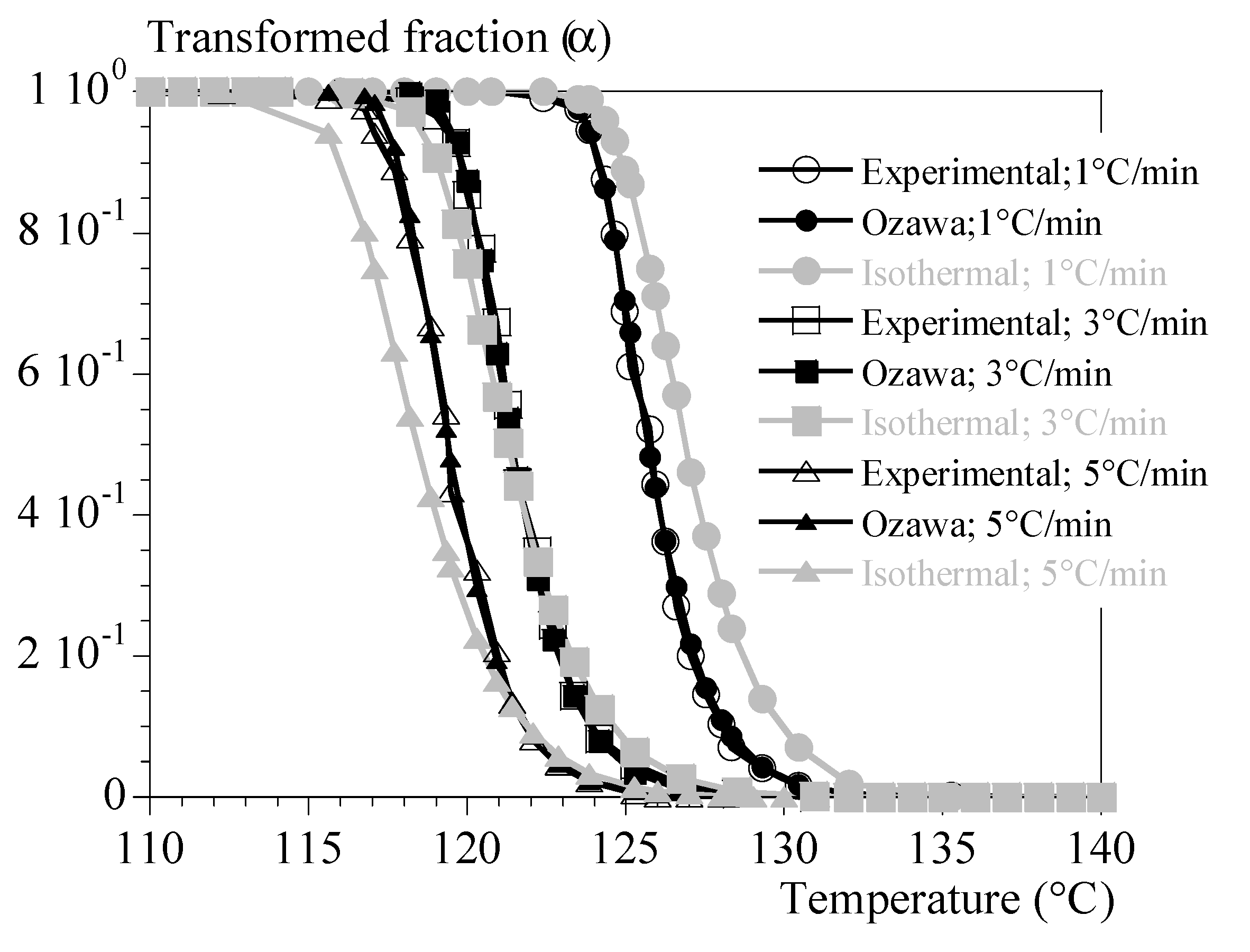

Under non-isothermal conditions, the sample was first heated to 200 °C to erase any previous thermal history. Then, the sample was cooled down to 100 °C at various rates (5 °C.min-1, 3 °C.min-1 and 1 °C.min-1) and heated to 200 °C at the same rate. The three cycles were performed successively on the same sample. First-order transition temperatures (melting temperature Tm and crystallization temperature Tc) were measured at the maximum of the peaks.

Crystallinity ratio,

, was deduced from the melting enthalpy,

accounting for the theoretical melting enthalpy of a fully crystalline PP,

, of 148 J.g

-1 [

34] (

.

Under isothermal conditions, the sample was also initially heated to 200 °C to erase thermal history. Then, the sample was cooled down at 20 °C.min-1 to constant temperature. This latter was chosen well above the previously determined crystallization temperature for this rate. Then, the heat flow evolution was recorded as a function of time. This protocol was performed on the same sample for five isotherms: 125 °C, 127.5 °C, 130°C, 132.5 °C and 135 °C.

2.3. Polarized Light Microscopy

Polarized Light Microscopy observations were carried out at different isothermal temperatures to determine growth rate of iPP spherulites. To observe spherulite growth, the sample needs to be thin enough (typically a few hundreds of µm) to allow light transmission. To obtain such thin samples, a little piece as cut using a razor blade and then placed on a glass slide. Thereafter, the glass slide was heated, thanks to the heating sample holder, up to a temperature of 200 °C (above melting temperature). Once the sample has melted, it was pressed under another glass slide in order to thin it.

Similar to isothermal calorimetric analyses, samples were then cooled at a rate of 20 °C.min-1 to reach different isothermal temperatures (125 °C, 127.5 °C, 130°C, 132.5 °C and 135 °C). Pictures of the sample were taken with a microscope at regular time intervals to record crystal growth. Analysis of each set of pictures (one for each temperature) was performed using ImageJ software. For each temperature, the radius of three spherulites was measured as a function of time and the growth rate was determined by performing a linear fit.

2.4. Rheological Analyses

Rheological Analyses were carried out on an MCR-302 stress-controlled rheometer manufactured by Anton Paar. Samples were analyzed using 25 mm diameter parallel plate geometries with an initial gap height between plates of about 1 mm. To accommodate the changes in sample thickness, particularly during crystallization and melting phenomena where the polymer density undergoes significant changes, a slight compressive force (0.05 N) was applied to the material to adjust the gap height accordingly. Strain and frequency were fixed at 0.03 % and 1 Hz, respectively. Under these conditions, the samples were solicited within their linear range for the entire temperature range allowing the determination of the storage

and loss

moduli or the complex viscosity,

Above 200 °C, this latter could be interpolated as a function of pulsation,

, and temperature, T, using classical Carreau-Yasuda model (equation (1)):

with

for

of 200 °C.

To study the influence of crystallization and melting phenomena on the mechanical behavior of iPP, experimental protocols similar to calorimetric analyses were carried out.

Under non-isothermal conditions, the sample was initially heated up to 200 °C to erase thermo-mechanical history. Thereafter, the sample was subjected to successive cooling-heating cycles (200 °C 100 °C 200 °C) at different temperature ramp rates identical to those used in DSC (5 °C.min-1, 3 °C.min-1 and 1 °C.min-1).

Under isothermal conditions, sample was also heated up to 200 °C. It was then cooled down to the isothermal temperature. Due to oven thermal inertia and sample dimensions, the ramp rate cannot be as fast as in calorimetric analyses. Therefore, to enhance the control of the sample temperature and to prevent crystallization during cooling, especially when approaching the crystallization isotherm, the experimental protocol comprises two steps: cooling from 200 °C to 150 °C at 10 °C.min-1 and then cooling from 150 °C to the crystallization isotherm at a rate of 5 °C.min-1. Isotherms were identical to those selected for calorimetric analyses: i.e., 125 °C, 127.5 °C, 130°C, 132.5 °C and 135 °C. Temperature sensor was located under the bottom plate of the rheometer.

3. Theoretical

3.1. Overall crystallization kinetics

The theories for overall crystallization kinetics are based on the physical description we briefly remind below:

In the molten phase, some nuclei are activated according to nucleation kinetics, i.e., the probability per unit of time for one of them to become a growing entity.

Growth starts immediately without any delay time.

Only the nuclei located in a liquid region can be activated.

Growth of entities stops when they impinge each other, i.e., no overlapping is allowed.

The objective of the overall kinetics theories is to describe the evolution of the entities volume fraction (resp., the probability for a given point in the medium to be absorbed by one of the entities), . It is important to note here that this quantity can be related to the degree of crystallinity if, and only if, all the spherulites possess the same constant crystallinity ratio.

In any case, the mathematical treatment would be straightforward only if the above constrains are not imposed, which would make the solution not physical. Advances in numerical solving has alleviated this difficulty, but in the 40’s authors had to overcome such limitation in an analytical manner. So, they focused their effort in finding under what conditions and how one can link this not-physical solution to the real situation. This led to the introduction of additional assumptions:

All the entities grow at the same rate in all accessible directions (spheres in the space, disk in a plane, etc.).

Total volume remains constant (isovolumic assumption).

Evans pointed out that the “not-physical problem” obeys a Poisson’s probability distribution. Then, the probability for any point to have been reached by exactly j entities at time, t, would be known (Eq. (2)).

E(t) is the mathematical expectancy, i.e., the average number of entities that would have been able to reach the given point between time 0 and time t. This function combines nucleation and growth kinetics.

If the second set of assumptions are followed, the probability that the point has

not been reached (j = 0) remains the same in both the “not physical case” and the “physical case”. This can be written as (Eq. (3)):

E is nothing else than the extended volume fraction defined by Avrami [

18,

19]. So, the question is then how to quantify E? This is possible when nucleation and growth kinetics are known.

If one describes the nucleation with an activation frequency, q (probability per unit of time for one nucleus to be activated), applied to an initial density of randomly distributed pre-existing potential nuclei and giving rise to spherical entities growing at the rate, , one can express E and, then (eqs. (3) and (4)).

To achieve that point, let’s consider that the probability for one nucleus per unit volume to be activated between any times

and

is given by

, where N is the density of residual nuclei. Only those nuclei that are within a distance of less than

can reach the point where E is calculated. Considering all directions in space, this define a sphere and finally:

E is the fictitious number of entities that would have been in a situation to contribute to the crystallization of one given point representative of the medium. The density of entities that effectively exists in the medium is given in Eq. (5).

In the case where the product

is very high compared to

(

i.e., activation is so fast that one can assume an instantaneous nucleation at the beginning of crystallization), Eqs. (4) and (5) can be simplified into Eq. (6) and

can be estimated by numbering spherulites.

In such a case, only the knowledge of

is required to model crystallization. Optical microscopy or even DSC measurement [

35] enables the assessment of this parameter as a function of temperature. Hoffman Lauritzen model [

15,

16] allows to model it.

In case

and

have equivalent influence over time, then nucleation occurs sporadically in time, and q and

have to be identified. Though some attempts exist to estimate them [

36], this is still difficult. At this stage, the isokinetic assumption [

19,

25,

26] that stipulates that q and

obey the same fundamental physical processes and then have the same type of dependence upon temperature (

allows for the simplification of Eq. (4) into Eq. (7).

Using a characteristic time defined by Avrami from q, a uniform set of equations can be proposed that is totally equivalent to Avrami’s set of equations (Eq. (8)).

In the case of an instantaneous nucleation, E is proportional to

and to

in the case of sporadic in time nucleation. In this work, we accepted the approximate form of E as given by (Eq. (9)).

If crystallization takes place in isothermal conditions or under a constant cooling rate,

, and accounting for the fact that q only depends on temperature, one can easily retrieve the so-called Avrami’s or Ozawa’s equations (Eq. (10)).

where:

with,

, the initial temperature and, T, the temperature at time, t.

is the kinetics parameter from Avrami. n is the Avrami’s exponent.

is kinetics parameter.

From a practical point of view, as q cannot be accessed experimentally, we preferred to reformulate Eq. (11) as a function of the growth rate. This was done thanks to isokinetics assumption.

3.2. Microstructure description

As explained in the introduction, some parameters that can be correlated to microstructure have been defined. The first of them could be the number of spherulites,

(Eq. (5)). Unfortunately, the initial density of potential nuclei,

, is unknown. In consequence, we decided to use N as the

first parameter that is only proportional to

(Eq. (12)) and can be expressed as a function of

and

only.

The

second parameter is an image of the maximum average radius (Eq. (13)). To calculate it, let us consider that the number of spherulites that were nucleated between times

and

is given by:

The maximum radius of those spherulites at time, t, is

. Thus, average maximum radius is:

Simple mathematical treatment allowed to conclude that

is proportional to a parameter we named, <R>, that depends on

and

(Eq. (15).

where R is given in Eq. (12).

Last parameters are deduced from Evans’ approach. Indeed, it is possible to know the probability for one point to be absorbed by exactly two entities in the fictitious case of a Poisson’s probability distribution,

(Eq. (2)). One can assume that as long as

is negligeable, transformation mainly results from

individual spherulites of maximum radius R. Transformed volume fraction is almost equal to

. When

becomes significant,

. At this stage, the presence of aggregates of two spherulites becomes probable, although it is not possible to provide an exact number. The same demonstration can be done with

that enables to know whether aggregates of three spherulites are probable or not.

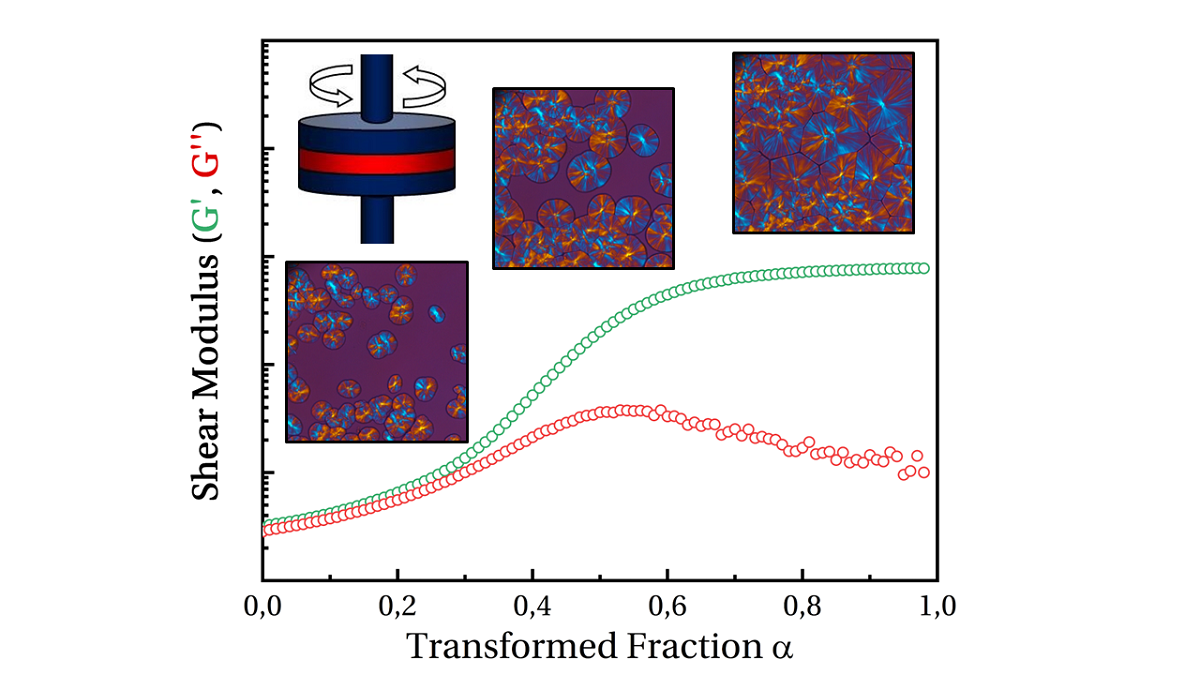

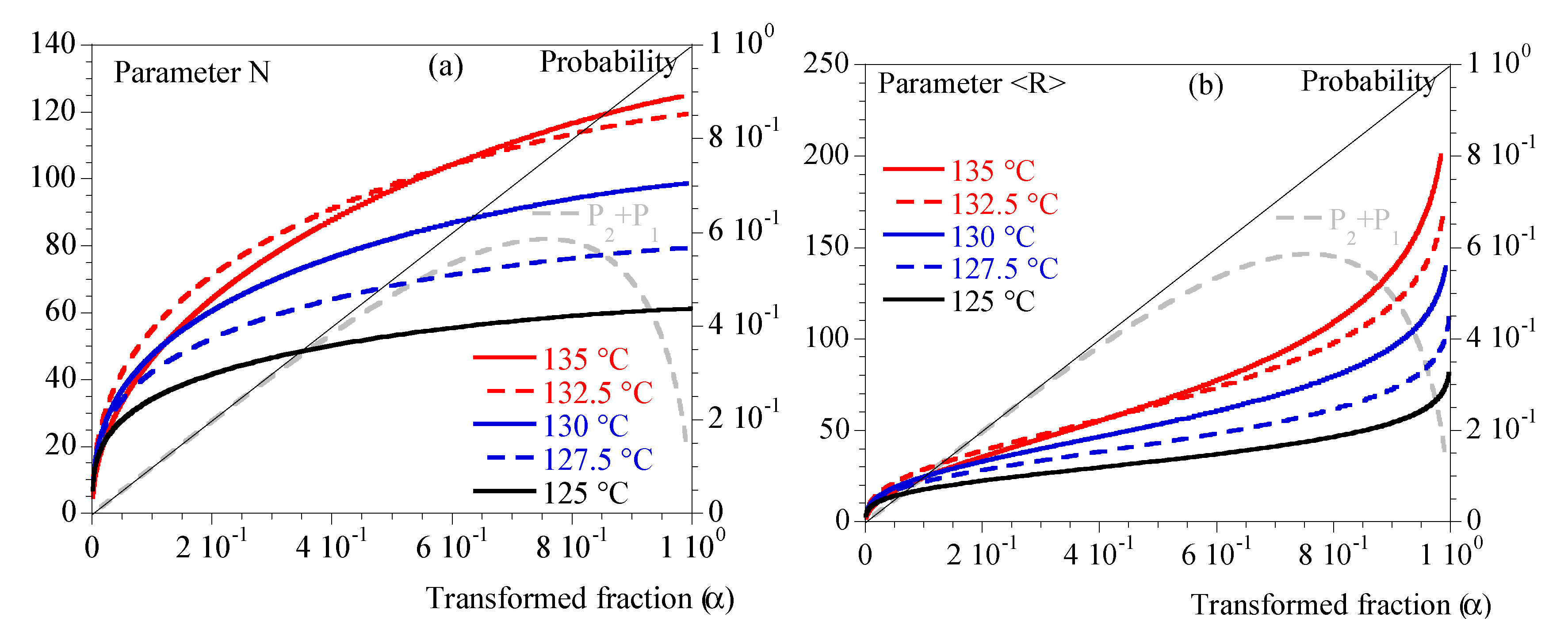

Figure 1 depicts the meaning of those parameters.

Figure 1 depicts the result of this analysis as a function of mathematical expectancy, E, making it an universal analysis that does not depend on nucleation and growth parameters. We used this picture to estimate the topology of the microstructure at the instant of significant change in rheology.

To summarize that:

Below 10 to 15 % of transformed volume fraction ( ), crystallization results mainly from the growth of statistically individual spherulites. During that period, the microstructure can be seen as individual semi-crystalline spheres per unit volume in a soft matrix. Maximum radius is R. The size distribution and the average radius depends on nucleation kinetics.

From 15 to 40 % impingement of spherulites two by two cannot be neglected. Obviously, Poisson’s analysis does not allow to evaluate the number of impingements. It only allows to say that it is probable that impingements had occurred. Then, microstructure results from single spherulites and isolated aggregates.

From 40 % presumably coalescence takes place. Progressively, the microstructure turns to a solid “skeleton” with embedded liquid poches.

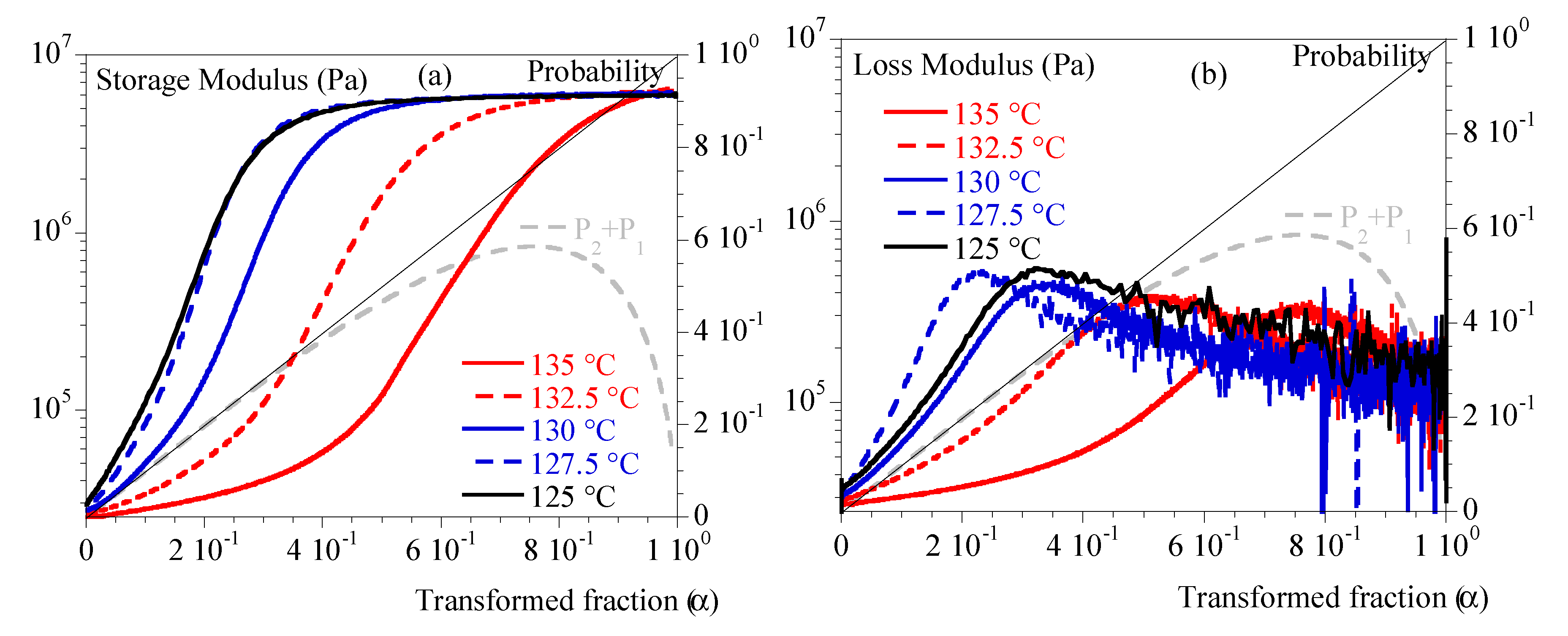

6. Results

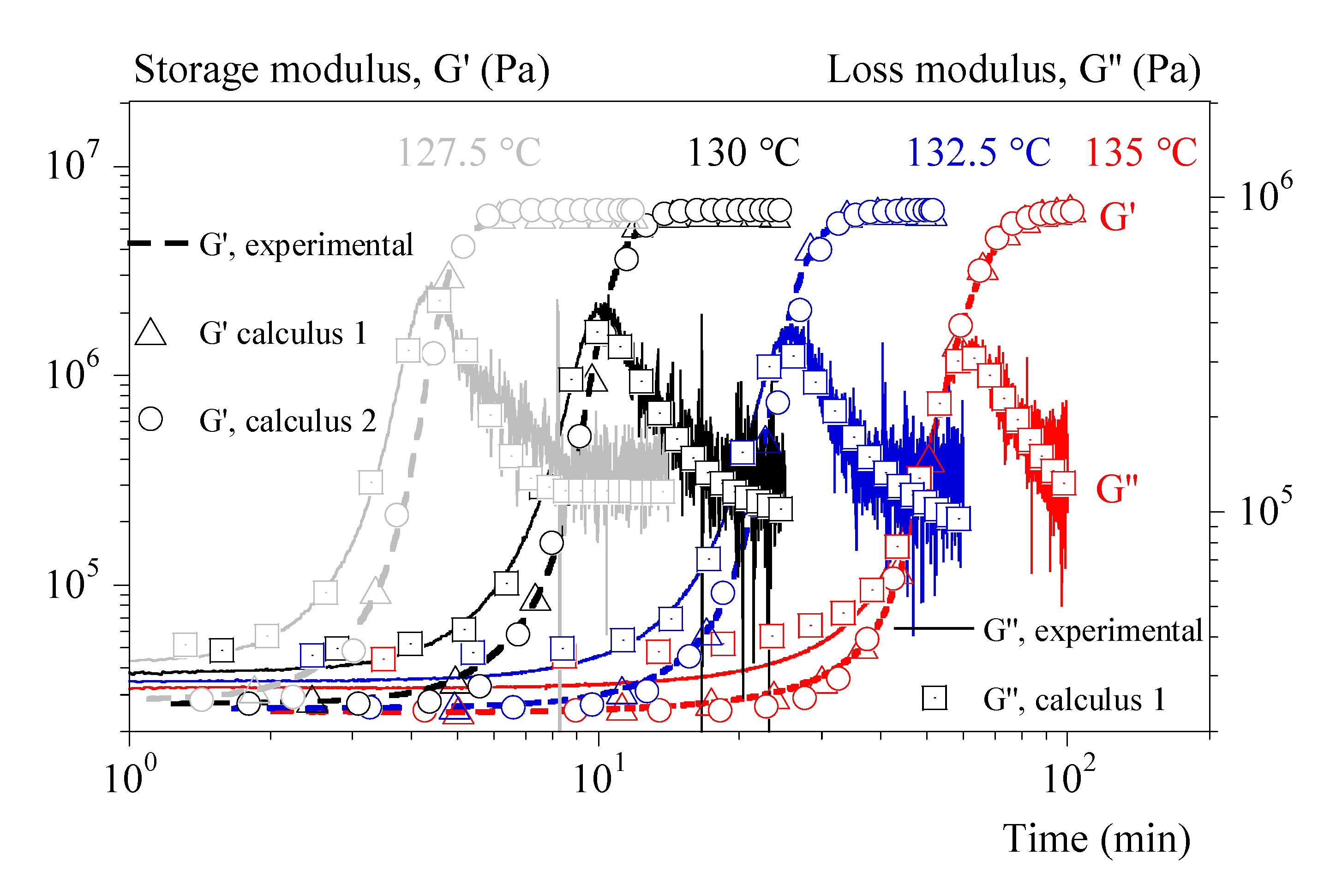

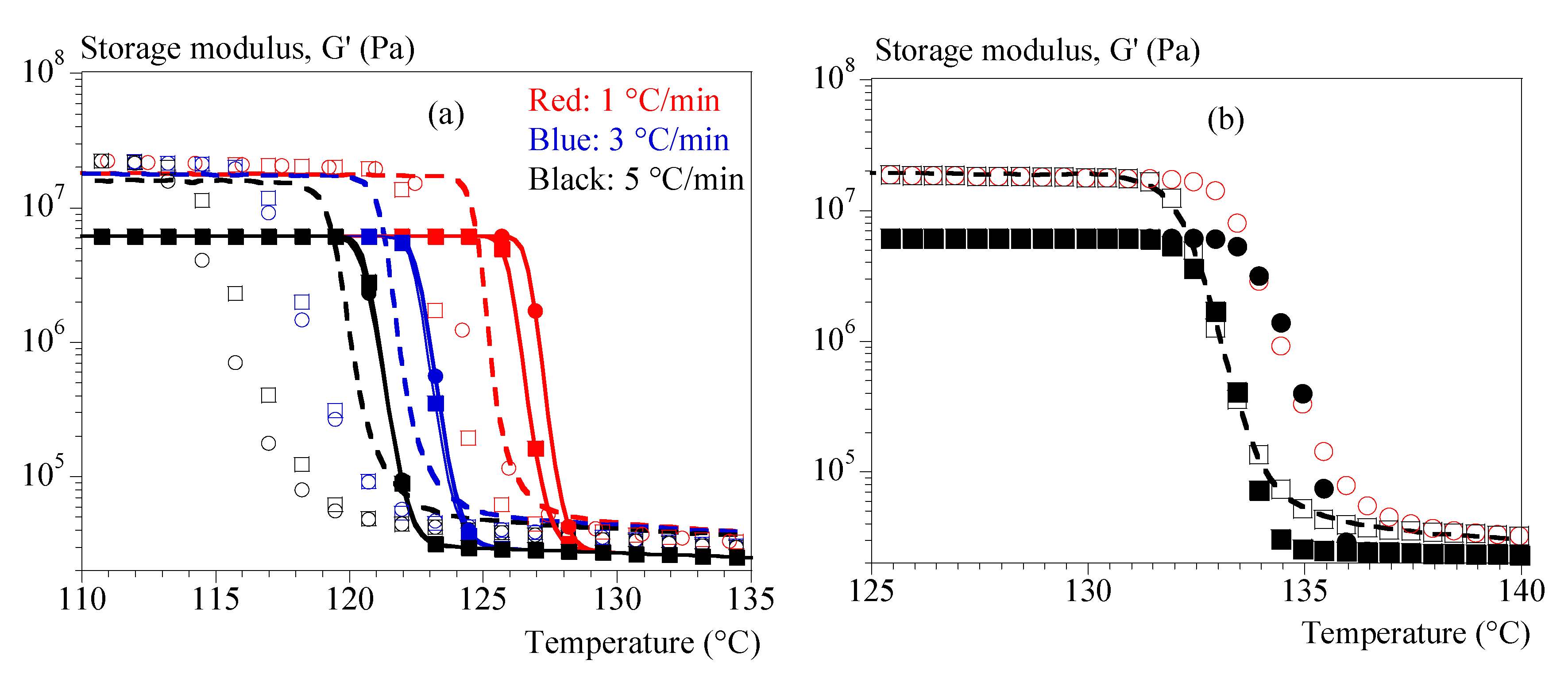

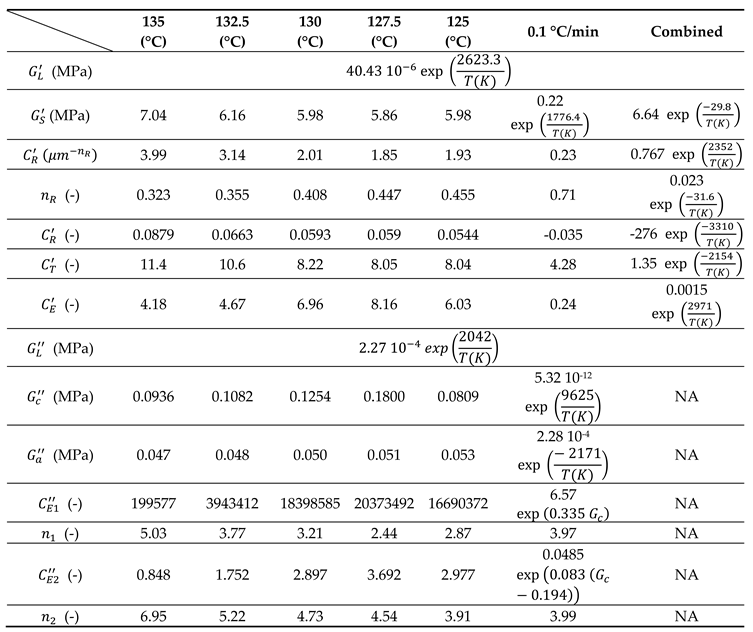

The equations (19) and the parameters of

Table 2 make possible to well reproduce isothermal evolution of G’ and G’’ whatever the protocol (

Figure 7). Nevertheless, only identification involving at the 0.1 °C/min could be extrapolated to non-isothermal tests.

Figure 8a displays the experimental (dashed lines) and calculated (symbols) evolutions of the modulus G' as a function of the temperature for cooling rates of 1, 3 and 5 °C/min. These tests were not used when identifying the parameters. This is therefore a validation. Only the formalism of the equation (19) was used. Parameters were identified in two ways:

1-by using only the test at 0.1 °C/min and interpolating the crystallization kinetics with Ozawa's formalism (eq. (10)).

2- by combining the test at 0.1 °C/min and the isothermal tests and interpolating the kinetics of not isothermal crystallization with the formalism of Ozawa (Eq. (10)).

Validations were adapted in 4 ways:

by using the coefficients 1 under the conditions of identification 1 (Ozawa crystallization, hollow squares).

by using the coefficients 1 and interpolating the crystallizations during the validation tests from the isothermal tests (hollow circles).

by using the coefficients 2 under the conditions of identification 2 (Ozawa crystallization, filled squares).

by using the coefficients 2 and interpolating the crystallizations during the validation tests from the isothermal tests (filled circles).

Figure 8b depicts the efficiency of those 4 routes for the test under cooling rate of 0.1 °C/min.

Our approach reproduces the effect of the cooling rate and the order of magnitude of the moduli. However, predictions of the rate effect are clearly better if the identification is done on a larger data set (identification 2). In parallel, it seems that a better estimation of the crystallization kinetics is favorable (Ozawa model). Finally, the model would deserve to be adjusted to better identify the modulus after crystallization. However, to achieve that point it will be necessary to consider the relaxations specific to the amorphous phase. Further study is therefore still needed.

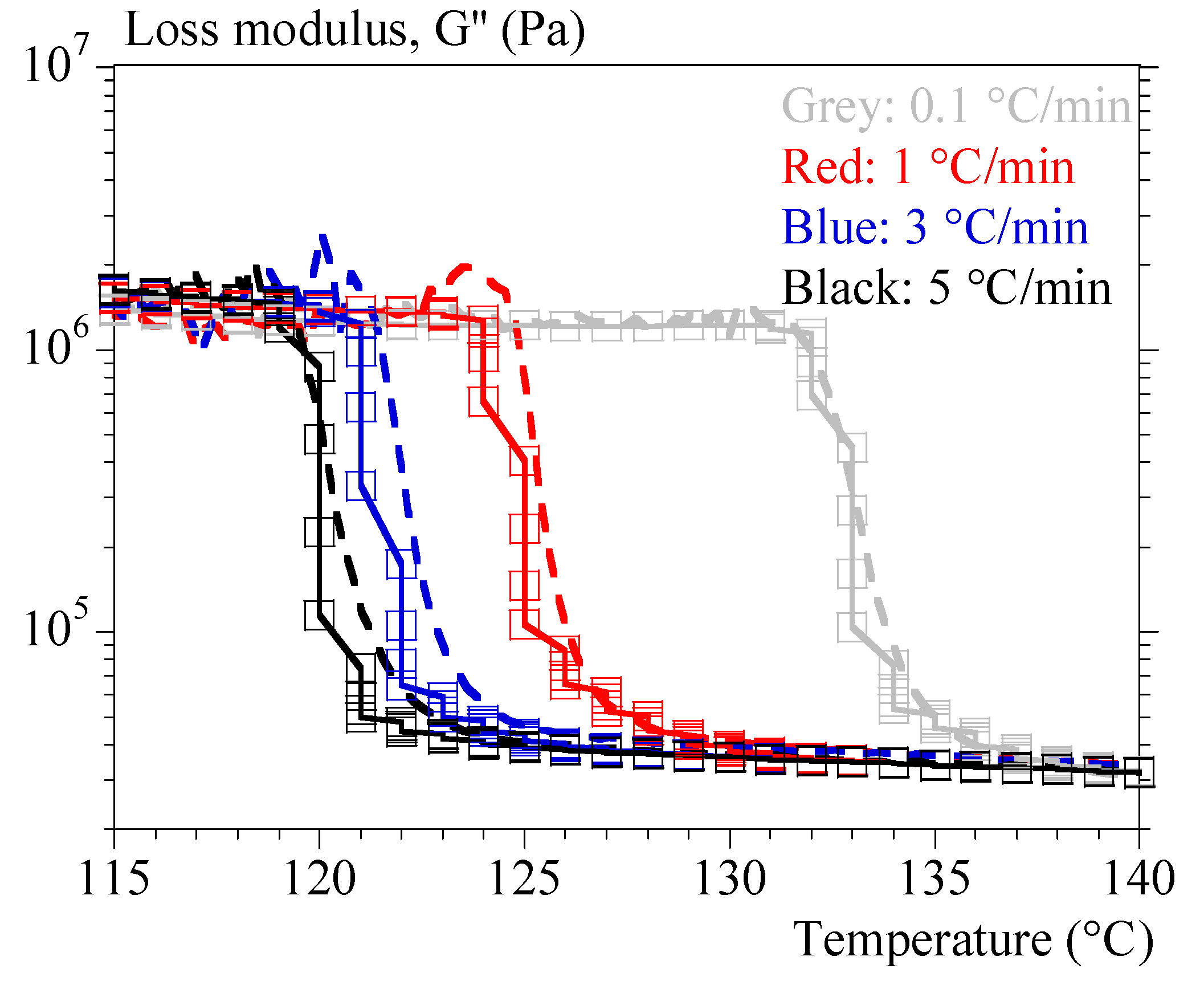

Regarding G'', the proposed formalism was able to independently reproduce the isothermal and the non-isothermal tests, but a unique set of parameters was not found. This difficulty in reproducing the two conditions through a single set of parameters is not surprising. G'' contains the viscoelastic effects and has therefore a particular relation to time. We could however propose a modeling of the cooling rate effect that was quite satisfactory from identification with the test at 0.1 °C/min (Figure 9).

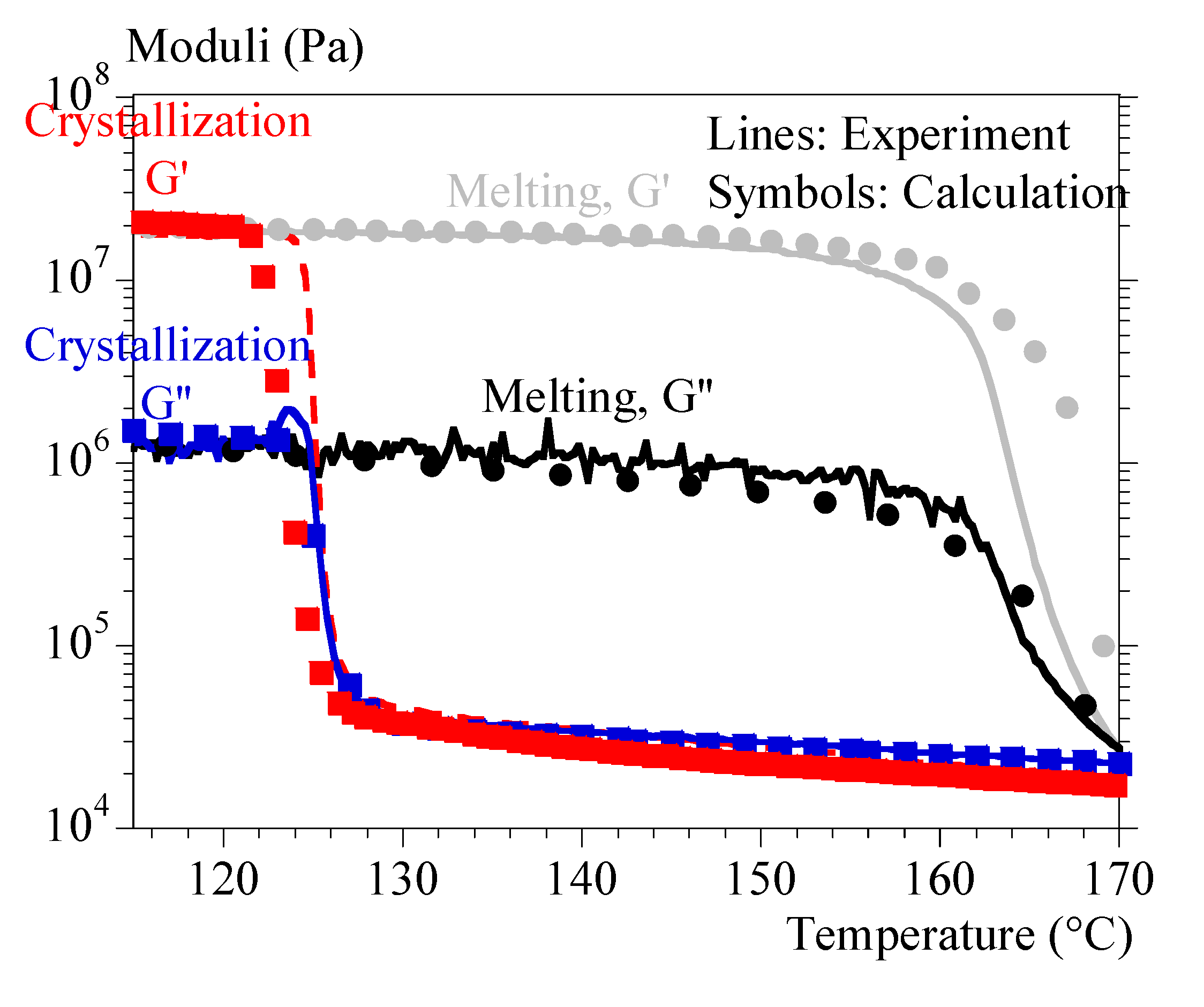

As for the melting tests, they were sufficiently well reproduced with the simple mixing law. It was then possible to reproduce cycle melting – crystallization with a good agreement (

Figure 10).

Note, however, that each condition was treated independently, assuming that the initial states were equilibrium: total and relaxed melting and complete crystallization at equilibrium. Cycle modeling will require considering intermediate crystalline states. In the same way, a complete modeling now requires accounting for the relaxations specific to the amorphous phase, in particular the principal relaxation. This will require further work.

Let us conclude here that the feasibility of the approach is validated. It represents a pragmatical and simple alternative to the necessary theoretical developments.

7. Conclusion

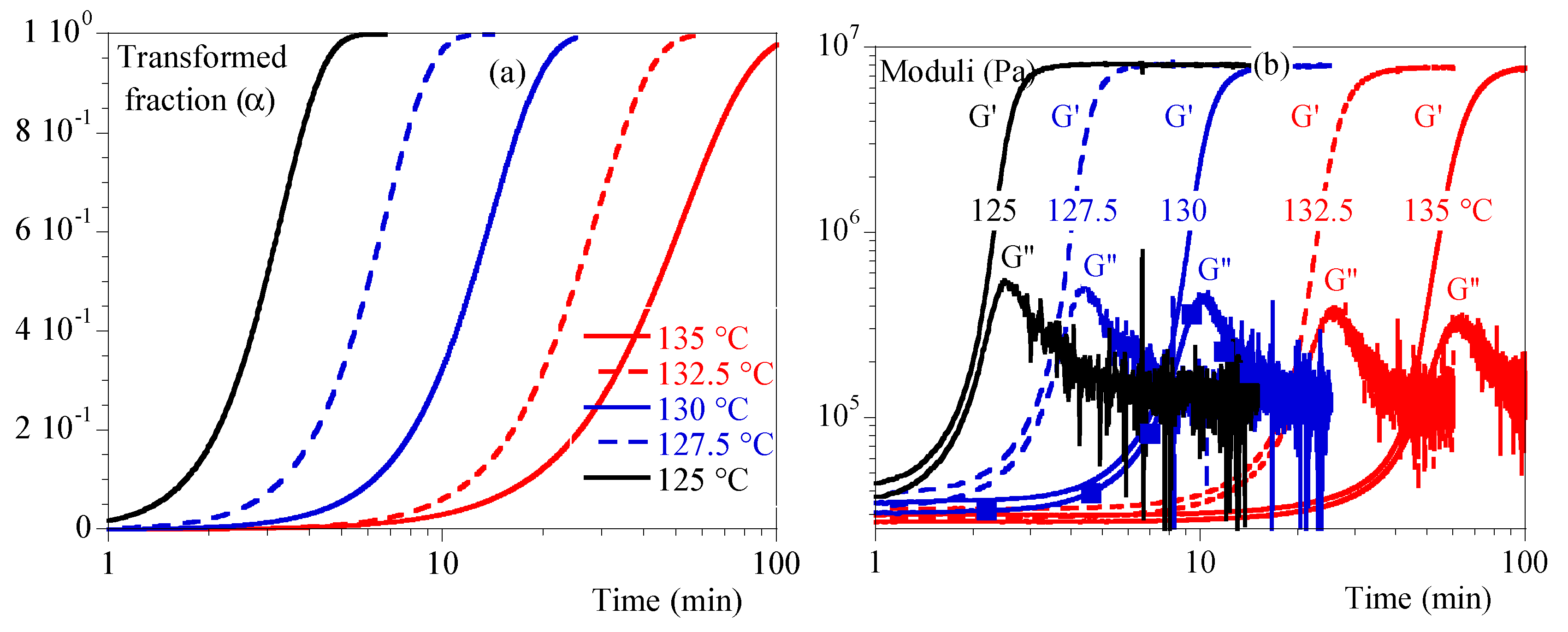

The viscoelastic properties of PP during crystallization were studied under isothermal conditions and at constant cooling rates. It was shown that, whatever the conditions, the mechanical effects of crystallization cannot be modelled by considering the degree of crystallinity alone.

In fact, the mechanical effects of crystallization are contemporaneous with the increase in the transformed volume fraction, but not simultaneously.

Stiffening can occur at different stages of crystallization, depending on the thermal conditions. This could be one of the reasons for the discrepancies and controversies in the literature.

In summary, the higher the crystallization temperature, the more coalescence between spherulites is involved when the modulus increases.

Consequently, the crystallizing medium must be composed of individual spherulites at low temperature (high cooling rate), aggregates at medium temperature or coalescing spherulites at high temperature (low cooling rate), for the storage and loss moduli to change significantly.

This represents a real improvement in knowledge in this area.

One reason for this could be that the contrast in the behavior between the two phases is of paramount importance in determining the properties of the crystallizing medium.

This justifies more in-depth studies aiming at combining microstructure modelling and micromechanical modelling of the mechanical behavior of the heterogeneous medium.

In a first approach, we show that one can refer to the microstructure at the spherulite scale in a simplified way to suggest phenomenological models for the storage and loss modules.

This represents a second important result of the study. It has been possible to propose simple mathematical models of the evolution of the two moduli as a function of the temperature for different cooling rates, which requires only classical crystallization analyses, growth rate measurements and rheometric tests to be used.

This could help to estimate residual stresses in additive manufacturing until more rigorous models are developed.

Figure 1.

Comparison of transformed volume fraction, , and . a) Schematic definition; b) Probability vs. mathematical expectancy, E.

Figure 1.

Comparison of transformed volume fraction, , and . a) Schematic definition; b) Probability vs. mathematical expectancy, E.

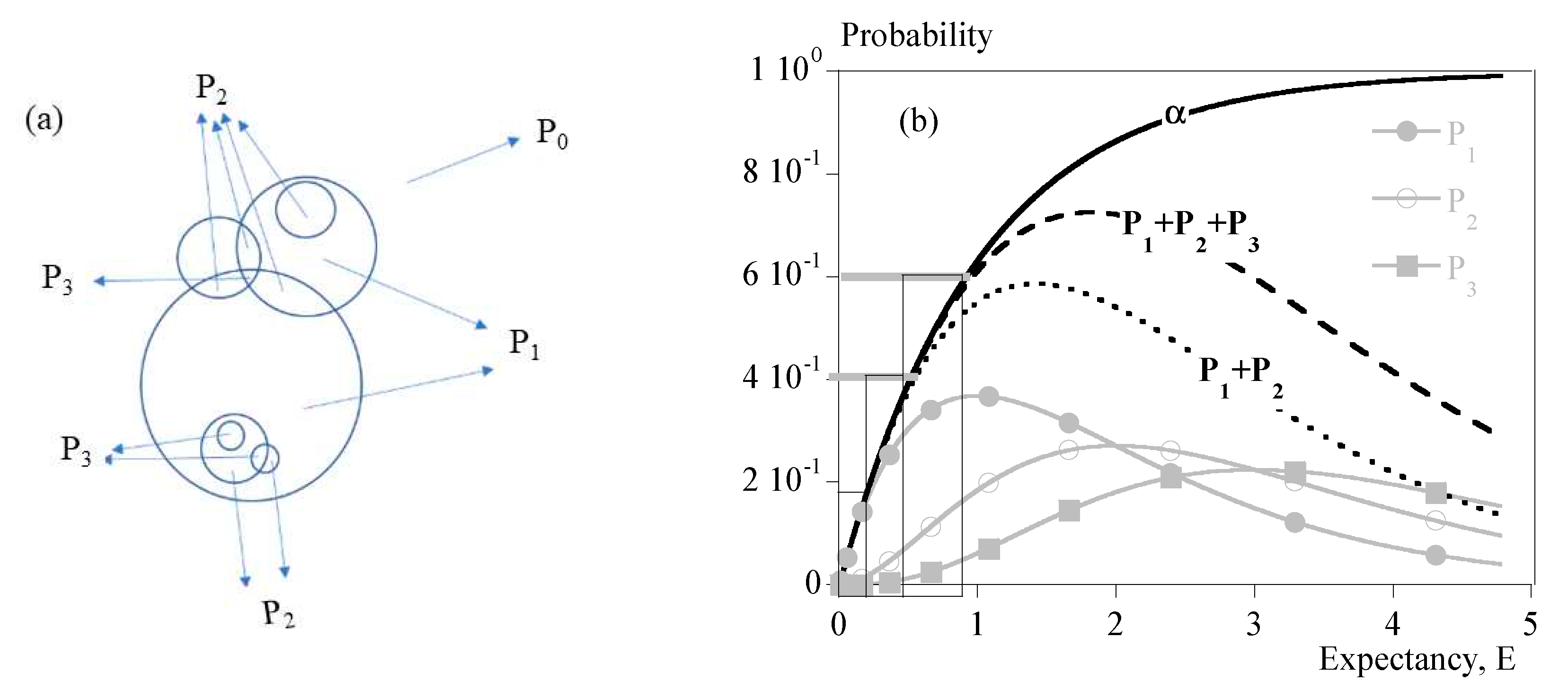

Figure 2.

Isothermal crystallization: comparison between 125, 127.5, 130, 132.5 and 135 °C. a) Transformed volume fraction vs. time. b) Storage module, G’, and loss modulus, G’’ vs. time.

Figure 2.

Isothermal crystallization: comparison between 125, 127.5, 130, 132.5 and 135 °C. a) Transformed volume fraction vs. time. b) Storage module, G’, and loss modulus, G’’ vs. time.

Figure 3.

Isothermal crystallization: comparison between 125, 127.5, 130, 132.5 and 135 °C. a) Storage modulus vs. transformed fraction. B) Loss modulus vs. transformed fraction. Straight line represents transformed fraction. Dashed grey line is (Eq. (2)).

Figure 3.

Isothermal crystallization: comparison between 125, 127.5, 130, 132.5 and 135 °C. a) Storage modulus vs. transformed fraction. B) Loss modulus vs. transformed fraction. Straight line represents transformed fraction. Dashed grey line is (Eq. (2)).

Figure 4.

Isothermal crystallization: comparison between 125, 127.5, 130, 132.5 and 135 °C. a) N (Eq. (12)) vs. transformed fraction. B) <R> (Eq. (15)) vs. transformed fraction. Straight line represents transformed fraction. Dashed grey line is (Eq. (2)).

Figure 4.

Isothermal crystallization: comparison between 125, 127.5, 130, 132.5 and 135 °C. a) N (Eq. (12)) vs. transformed fraction. B) <R> (Eq. (15)) vs. transformed fraction. Straight line represents transformed fraction. Dashed grey line is (Eq. (2)).

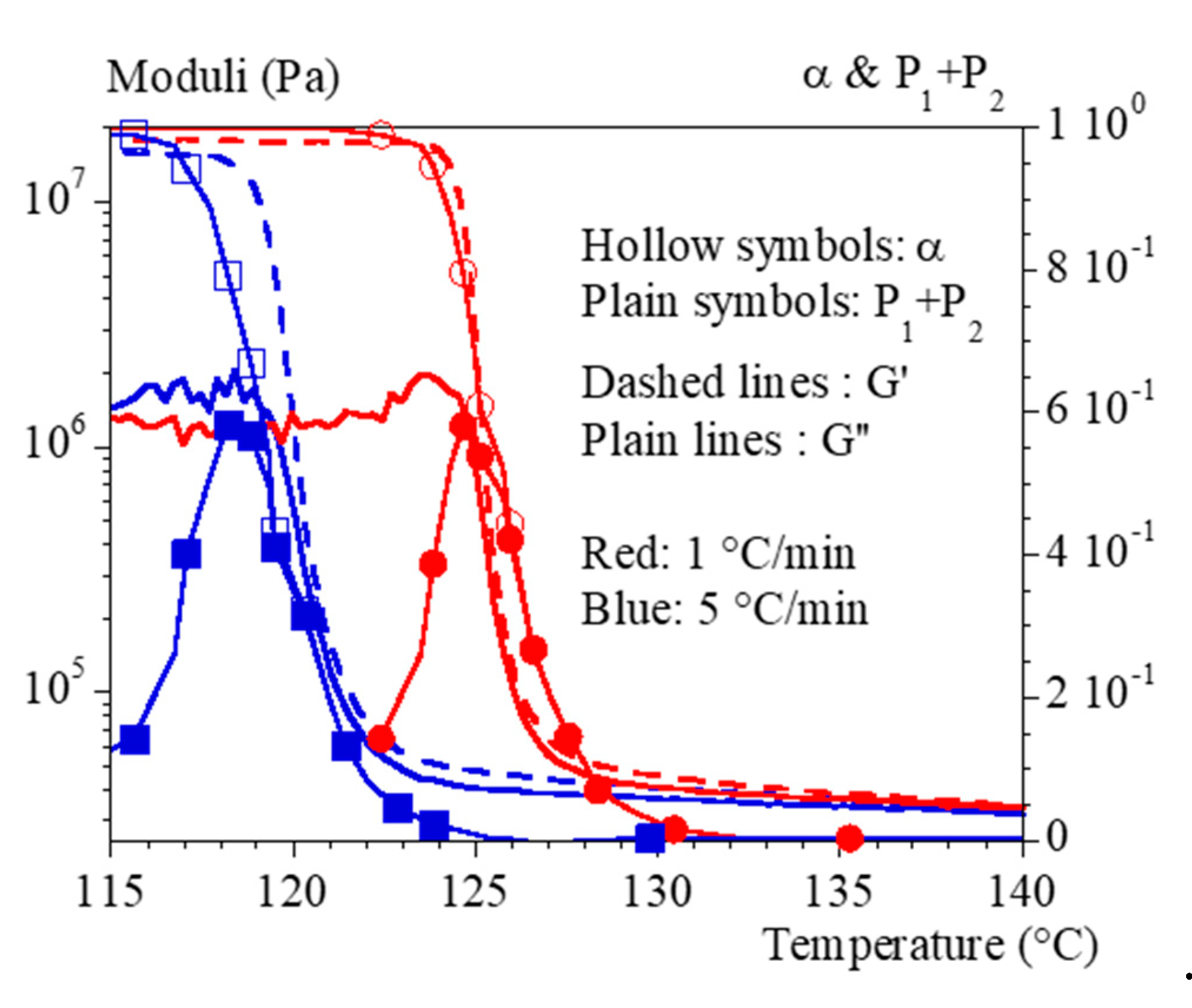

Figure 5.

Mechanical properties during crystallization performed under constant cooling rates. Comparison between 1 (blue) and 5 °C/min (red). Storage modulus, G’, is represented with dashed lines, loss modulus, G’’, with plain lines. Symbols represent (hollow symbols) and (plain symbols).

Figure 5.

Mechanical properties during crystallization performed under constant cooling rates. Comparison between 1 (blue) and 5 °C/min (red). Storage modulus, G’, is represented with dashed lines, loss modulus, G’’, with plain lines. Symbols represent (hollow symbols) and (plain symbols).

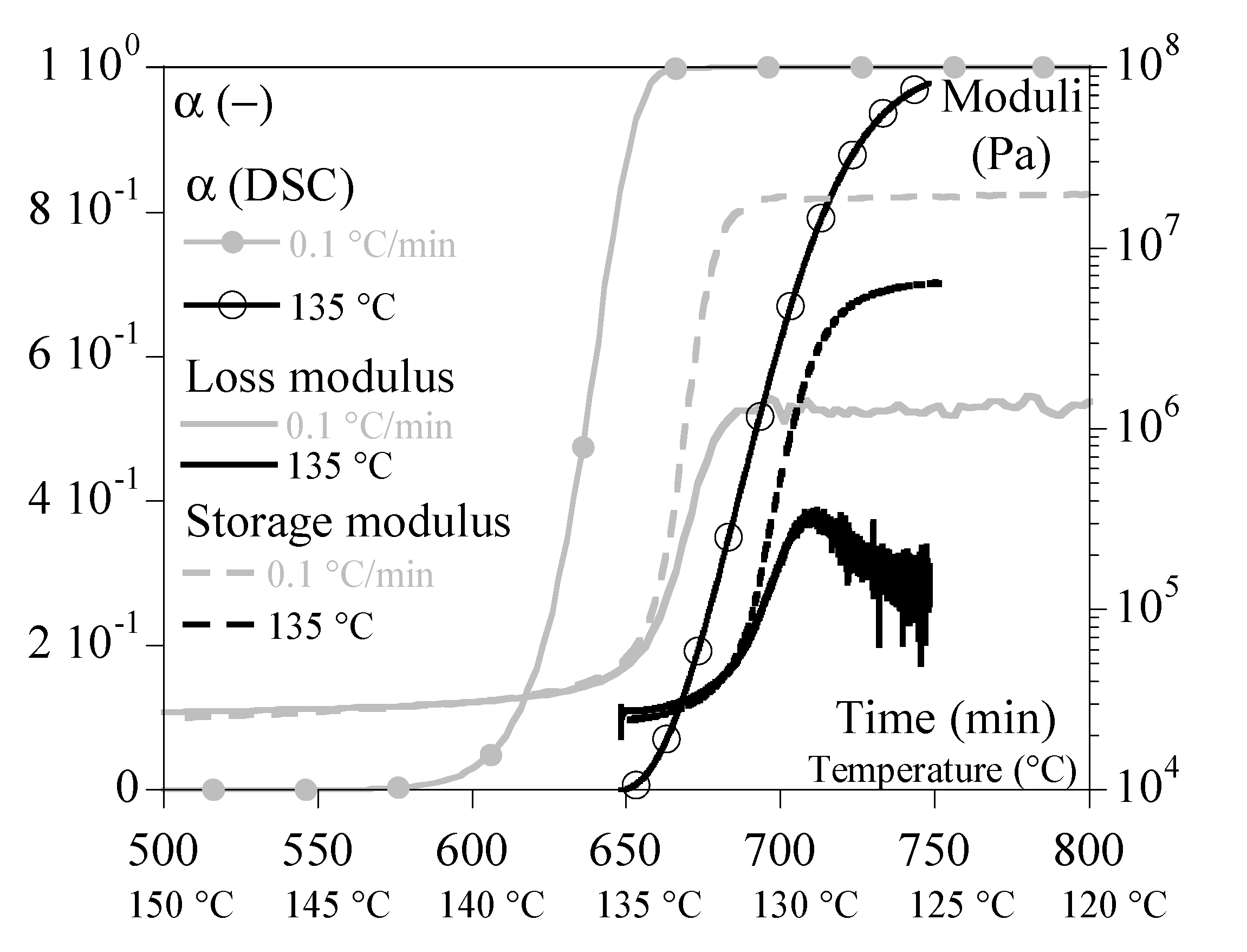

Figure 6.

Mechanical properties during crystallization performed under constant cooling rates at 0.1 °C/min (grey) compared to isothermal crystallization at 135 °C (black). Storage modulus, G’ is represented with dashed lines, loss modulus, G’’, with plain lines. Symbols represent .

Figure 6.

Mechanical properties during crystallization performed under constant cooling rates at 0.1 °C/min (grey) compared to isothermal crystallization at 135 °C (black). Storage modulus, G’ is represented with dashed lines, loss modulus, G’’, with plain lines. Symbols represent .

Figure 7.

Storage and loss moduli (G’ and G’’, resp.) vs. time during isothermal crystallization. Comparison between experiments (dashed and plain lines, resp.) and calculus. Calculus 1 is based on identification one by one. Calculus 2 combines isothermal tests and tests under 0.1 °C/min.

Figure 7.

Storage and loss moduli (G’ and G’’, resp.) vs. time during isothermal crystallization. Comparison between experiments (dashed and plain lines, resp.) and calculus. Calculus 1 is based on identification one by one. Calculus 2 combines isothermal tests and tests under 0.1 °C/min.

Figure 8.

Validation of equation (18) for storage modulus, G’. a) Comparison between experiments (dashed lines) and calculus (symbols). Colors refer to cooling rates; hollow squares: identification with tests at 0.1 °C/ and Ozawa crystallization; hollow circles: identification with tests at 0.1 °C/ and Avrami like crystallization; filled squares: combined with isothermal tests identification and Ozawa crystallization; filled circles: combined with isothermal tests identification and Avrami like crystallization. b) Results of a cooling rate of 0.1 °C/min.

Figure 8.

Validation of equation (18) for storage modulus, G’. a) Comparison between experiments (dashed lines) and calculus (symbols). Colors refer to cooling rates; hollow squares: identification with tests at 0.1 °C/ and Ozawa crystallization; hollow circles: identification with tests at 0.1 °C/ and Avrami like crystallization; filled squares: combined with isothermal tests identification and Ozawa crystallization; filled circles: combined with isothermal tests identification and Avrami like crystallization. b) Results of a cooling rate of 0.1 °C/min.

Figure 9.

Validation of equation (18) for loss modulus, G’’. Comparison between experiments (dashed lines) and calculus (symbols). Colors refer to cooling rates; hollow squares: identification with tests at 0.1 °C/ and Ozawa crystallization.

Figure 9.

Validation of equation (18) for loss modulus, G’’. Comparison between experiments (dashed lines) and calculus (symbols). Colors refer to cooling rates; hollow squares: identification with tests at 0.1 °C/ and Ozawa crystallization.

Figure 10.

Cycle heating – cooling at 1 °C/min; Comparison experiments – calculation.

Figure 10.

Cycle heating – cooling at 1 °C/min; Comparison experiments – calculation.

Table 1.

Isothermal characteristics for crystallization. Parameters are defined in Eqs. (10) and (11).

Table 1.

Isothermal characteristics for crystallization. Parameters are defined in Eqs. (10) and (11).

| Temperature(°C) |

125 |

127.5 |

130 |

132.5 |

135 |

(µm/min) |

20.8 |

13.2 |

7.93 |

4.68 |

2.69 |

(min-n) |

1.77 x 10-2

|

2.46 x 10-3

|

7.08 x 10-4

|

1.59 x 10-4

|

2.52 10-4

|

| N |

3.39 |

3.15 |

2.75 |

2.60 |

2.09 |

for n=3

(min-3) |

4.00 x 10-5

|

8.33 x 10-5

|

9.12 x 10-4

|

4.51 x 10-3

|

2.81 x 10-2

|

(µm-3.min3) |

3.13 x 10-6

|

2.00 x 10-6

|

1.78 x 10-6

|

7.96 x 10-7

|

2.10 x 10-6

|

Table 2.

Parameters of equation (18) to express G’ and G’’ as a function of T.

Table 2.

Parameters of equation (18) to express G’ and G’’ as a function of T.