For our hardware setup, we used a System76 Gazelle with quad-core 6 MB cache, 16 GB of DDR4 RAM, and a 3.5 GHz i7-6700HQ CPU. The operating system on this machine is Ubuntu 16.04 LTS.

4.1. Per-Face Popularity with β-Parameterization

The typical workflow with ndnSIM involves creating scenarios, which are implemented in typical C++ source files. The WAF build automation utility [

20] is then used to build and run the scenarios and support files. The scenarios are also often accompanied by the use of extensions, which are simply modifications (usually using inheritance from base classes of the simulator) or additional classes needed for the scenarios to function. The scenario file itself is where the entry point for the application lives.

One extension that we created was based on the Policy class. The Policy class in ndnSIM is the actual decision-maker as far as what items remain and what items are removed from the content store’s cache. We created a PopularityPolicy class as a subclass of Policy to define our cache replacement policy. In ndnSIM, data is automatically added to the cache, which is physically slightly bigger than the logical limit of the cache size. In Policy’s doAfterInsert method, a pure virtual function (method), is called immediately after a content object is added to the cache. Then, in this method, the decision can be made to remove any content object according to the cache replacement algorithm.

The PopularityPolicy class that we created maintains a pointer to the popularity manager (PopMan), which is also maintained in the ndnSIM’s NFD Forwarder class, which we modified. Therefore, the PopMan acts as an essential bridge from the forwarding strategy and fabric, to the cache replacement policy. The PopMan records when interests arrive, and over which face, so that ranking can be accomplished. This interest and face data is ultimately maintained in FaceContentFrequency objects, which maintain, as the name suggests, the frequency of requests for content, organized by specific faces. Each FaceContentFrequency object maintains all content requests and a ranked list for its face. This is the class responsible for determining an individual face’s contribution to the overall popularity. The PopMan, in turn, utilizes the contributions from its list of FaceContentFrequency objects, to determine what should be removed when it must decide on the next item to remove from the cache.

So, to summarize, the Policy (PopularityPolicy), in its doAfterInsert method, determines when the cache is full after an insert of a content object obtained from a returned data message. If the cache is full, the PopularityPolicy asks the popularity manager what content object must be removed from the cache. As described earlier, this decision is based on the overall contributions from all faces, normalized such that no single face has more influence than any other face. When this information is obtained, the PopularityPolicy sends an eviction signal to the content store, which evicts the corresponding object from the cache.

4.3. Simulation Results and Analysis

Firstly, we will discuss most of our results, which are derived from tests using the standard PFP-DA scheme. Then, we will discuss some of the early results we’ve obtained from the PFP-β experiments. We will demonstrate that our PFP-based schemes tend to perform substantially better than the current LFU-DA and LRU algorithms under most circumstances. The content space used in these tests consist of 10,000 content objects, using the Zipf-Mandelbrot distribution as implemented in ndnSIM . Unless otherwise noted, the following sections involve the PFP-DA scheme.

It should be noted that regular consumers will generally follow the Zipf-Mandelbrot distribution of requests, across all faces. In other words, the top requested content object would almost certainly be the top request content object on each of the faces. It is possible, however, once the Zipf-Mandelbrot rankings are lower that one face may request one item more than another that has a “higher ranking” based on the probabilities implemented in ndnSIM. In other words, item ranked 150 might be requested on one face more times than item 148, and vice versa. The distribution isn’t truly strict as implemented.

Attackers are expected to have some degree of coordination when spread across multiple faces, and in fact, we have implemented the scenarios so the attackers request in a generally uniform fashion across a small set of less popular items (by the Zipf-Mandelbrot distribution.)

4.3.1. Varying Cache Size

For these tests, one attacker is present for both the simple and advanced topologies, with a request frequency of 720 requests/second. Regular consumers request at 120 requests/second. For these tests in this section, only the cache size was varied, ranging from 100 items (1% of the total content space) to 500 items (5% of the total content space.)

The number of content objects requested by an attacker is equal to the cache size, so it is possible for the attacker to attempt to completely overwhelm the cache. For example, it is clear that if all the consumers attached to a router were attackers, then the cache would be entirely filled with only attacker content. The tests in this section and subsequent sections are to test variations and determine the robustness of the cache replacement algorithms.

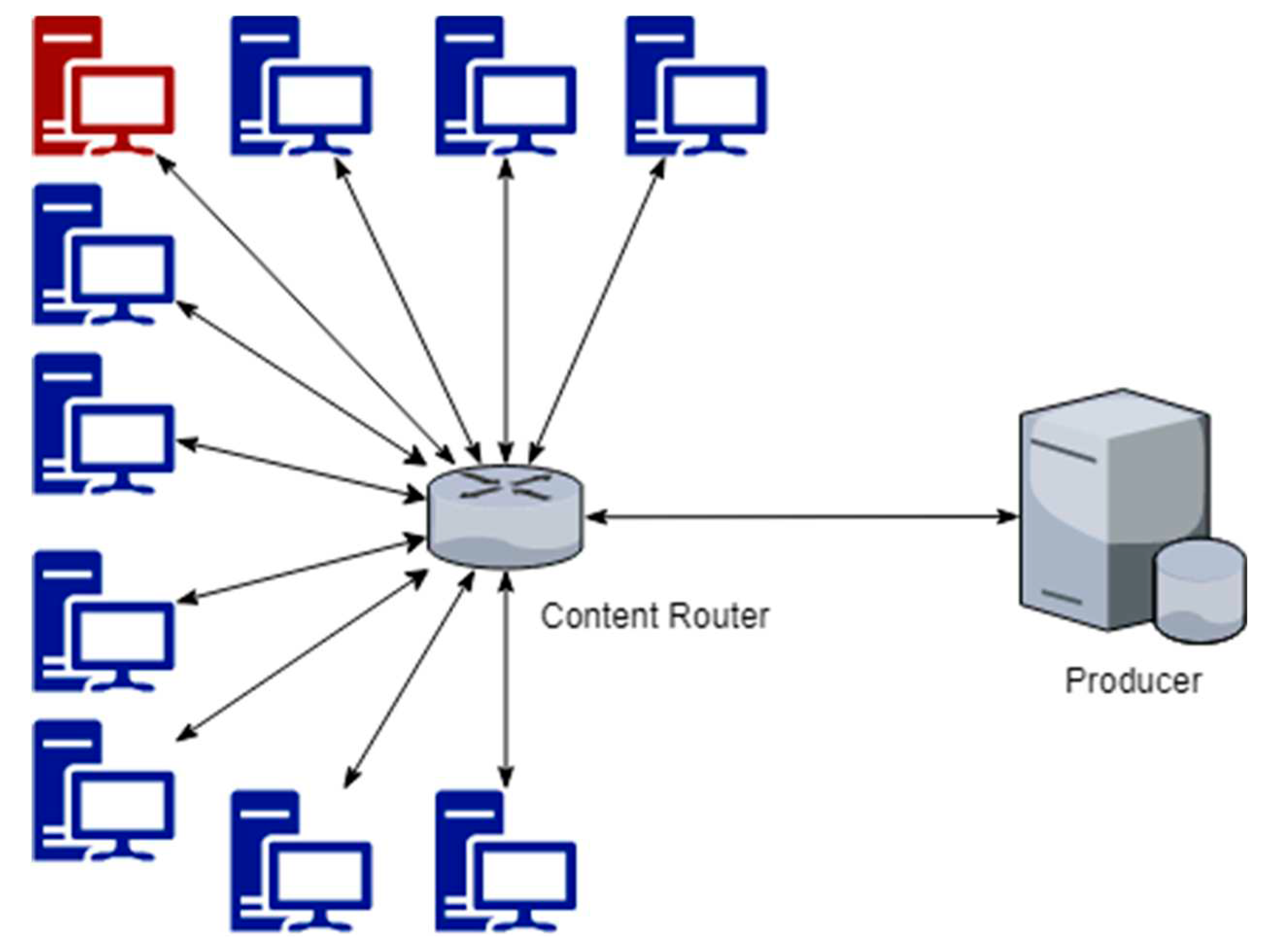

The data in

Table 3 gives us an interesting picture of how the cache size can affect both the pollution and hit rates. The pollution percentage indicates the percent of the cache at the router occupied by attacker content. The hit percentage (hit rate) is the percentage of legitimate consumer interests that are able to be satisfied by the content store’s cache upon arrival. We also look at the top 100 and top 50 items (according to Zipf-like distribution) to see how stable the algorithms are at maintaining the truly popular contents in the cache.

For all cache sizes, PFP-DA has both the lowest cache pollution percentages, and the highest hit rates. For example, even considering the smallest cache size (100, or 1%), LFU-DA does reasonably well, with an overall hit rate of 12.67%. But, this is over 6% less than PFP-DA. The percentages for the top 100 and top 50 objects are even more remarkable. LFU-DA, for example, maintains 50% to 81.03%, which is good, but PFP-DA maintains percentages from around 75% to nearly 99% for top 50 items. This shows overall excellent performance, and in specific, good resistance to the single attacker.

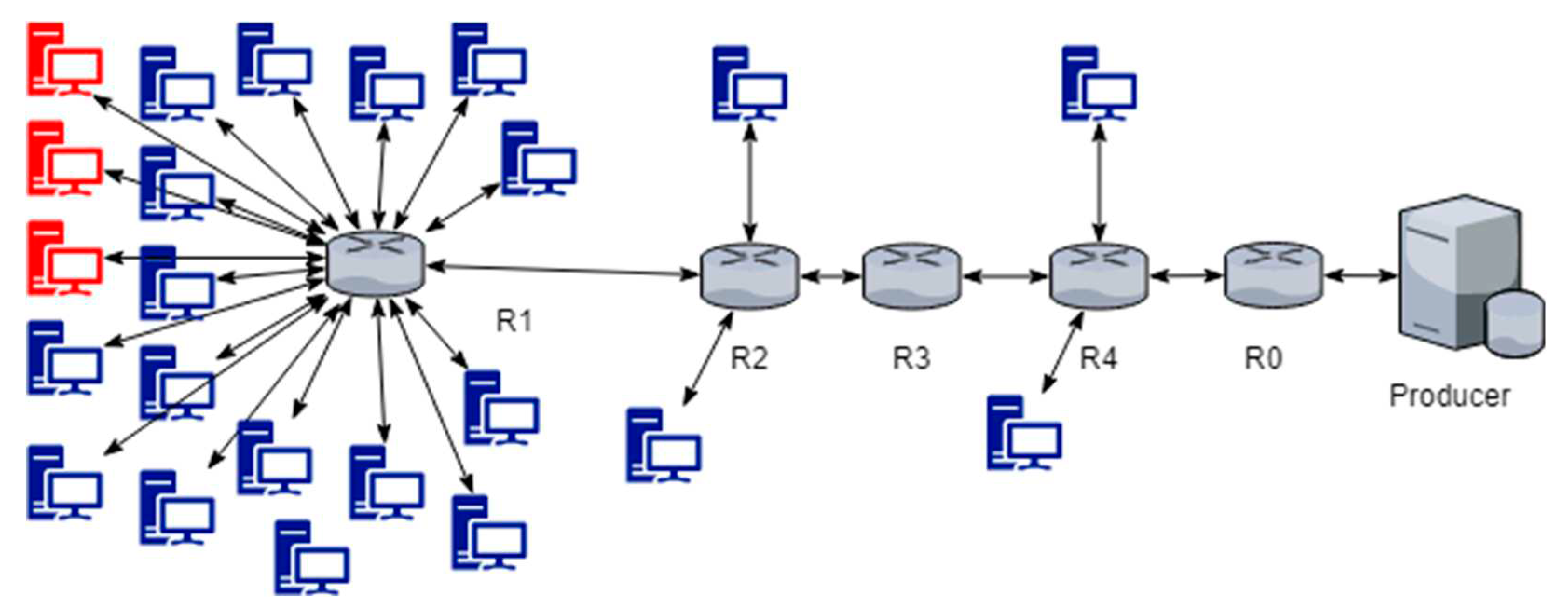

Now, let us consider the AT (Advanced Topology) results.

Both

Table 4 and

Table 5 show the data collected and summarized for the Advanced Topology (AT.) The R1 router is the router with most of the consumers attached, and with the single attacker attached as well. The routers R0, R2, R3, and R4 all demonstrate very low hit percentages, and sometimes higher cache pollution.

An interesting discovery is that overall cache pollution percentage is not necessarily an indicator of the hit rate. For example, on R2, PFP-DA maintains higher cache pollution percentages than do LFU-DA or LRU, but the hit rates are still better for PFP-DA than the other algorithms. This is because the cache pollution percentage does not capture information about the quality of items being cached (i.e., what rank in the Zipf-distribution they have.) However, in terms of hit rate, PFP-DA dominates on all hit rate metrics across all routers. Again, we see the top item hit rates on R1 in the 70% to nearly 100% range for PFP-DA.

4.3.2. Varying Attacker Request Frequencies (Single Attacker)

For these tests, one attacker is still present, but the attacker’s aggression is increased. Consumers still have a request frequency of 120, while attacker’s speed (request frequency) is varied from 360 up to 1200. That is to say, the speed varies from three times to ten times that of the normal consumer.

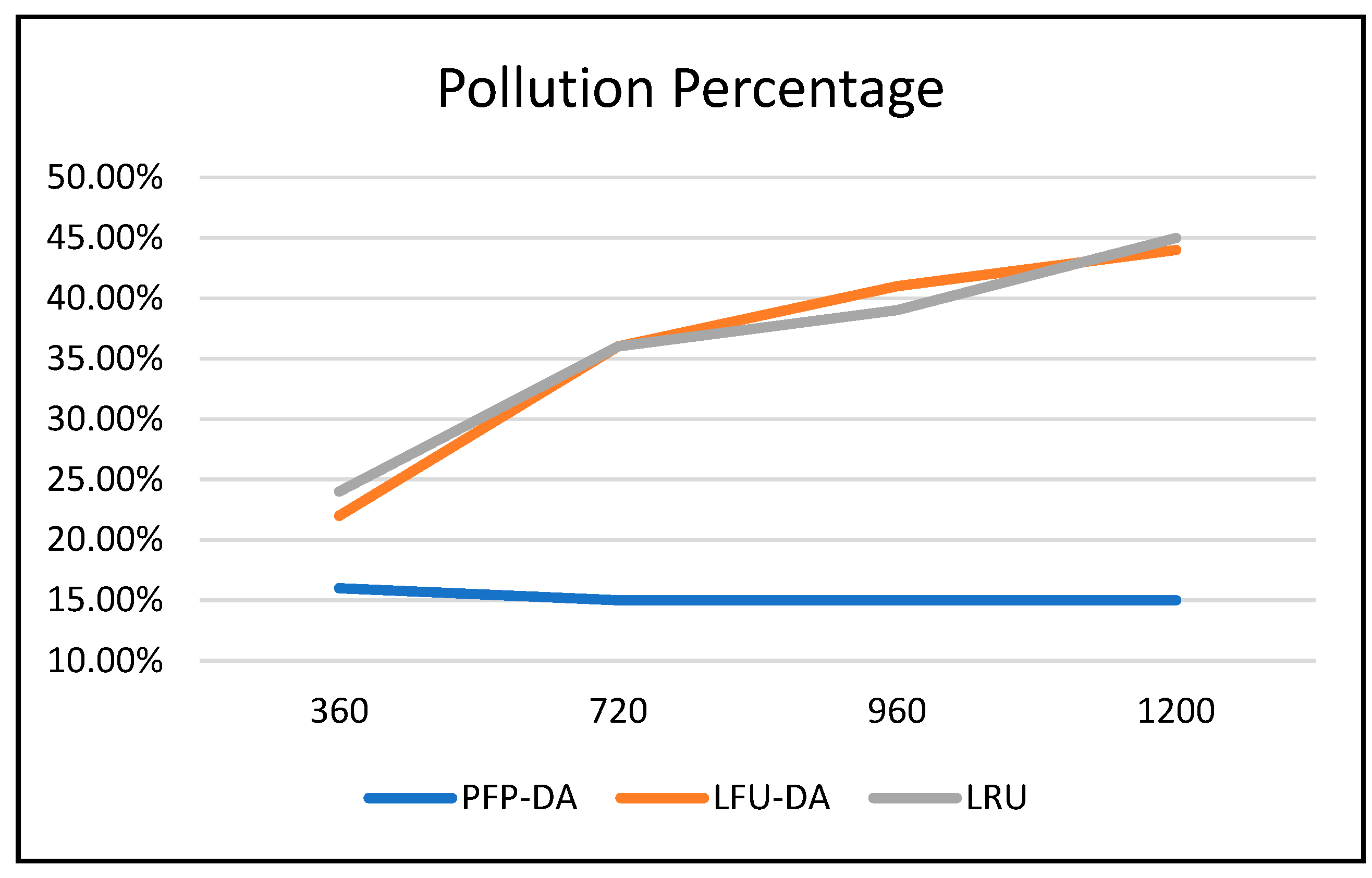

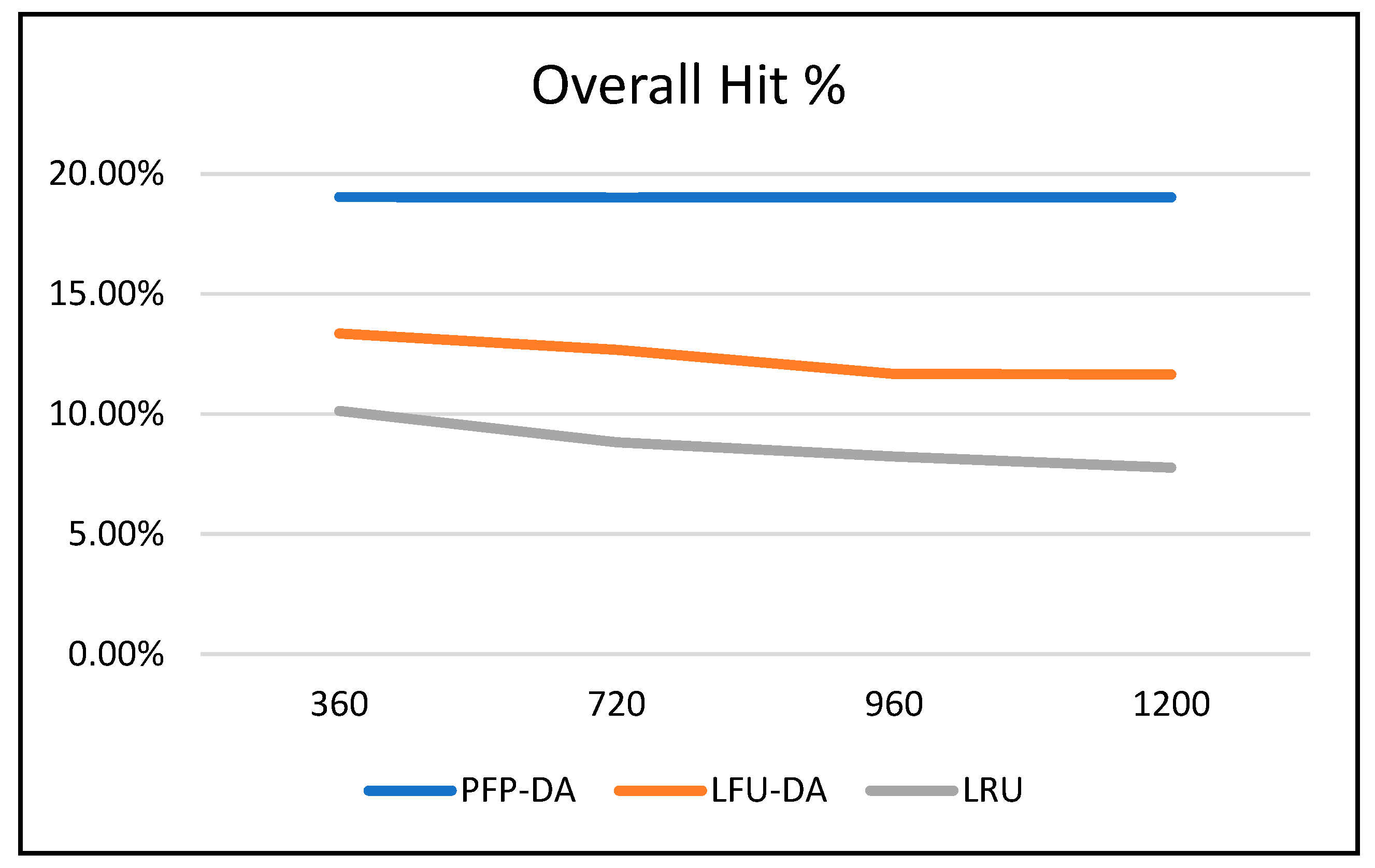

With the Simple Topology (ST), we observe in

Table 6 that the pollution percentages of the cache running PFP-DA remains essentially unaffected by the change in attacker request frequency. This is expected behavior, since the contributions from the faces are normalized. Thus, a single attacker (or more correctly, a single face being used as a conduit of attack, or realized attack vector), no matter how aggressive, cannot have any extreme effect on the cache other than what they would normally have if they were minimally, or not at all aggressive. The story is different for LFU-DA and LRU. While the percentage differences are not enormous, it is clear that both algorithms are susceptible to aggressive attacks.

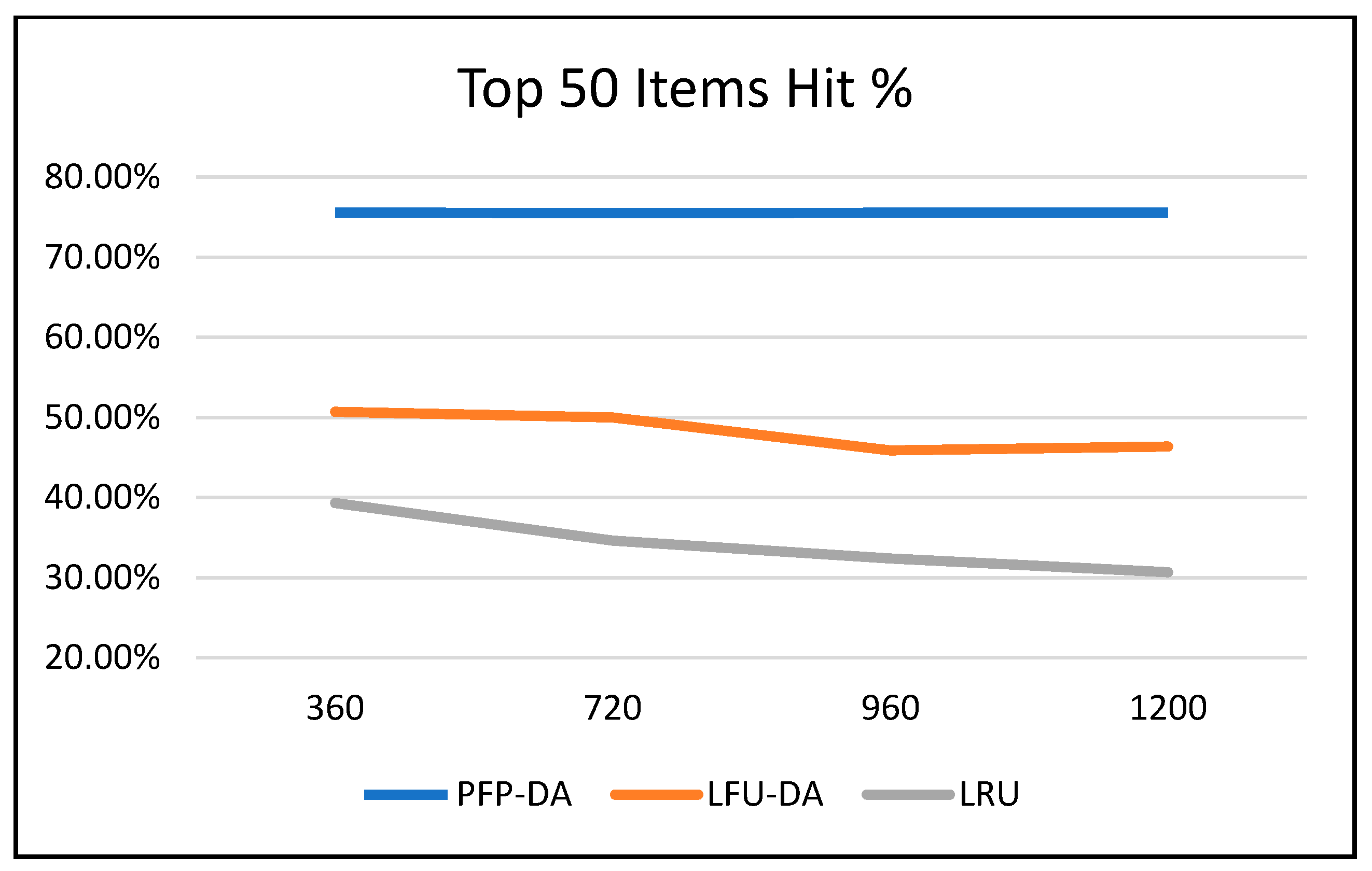

Figure 3,

Figure 4, and

Figure 5 all graphically demonstrate the data recorded in

Table 6. While the LFU-DA and LRU are affected by the increased attacker aggression, PFP-DA remains virtually unaffected. This is clearest when considering the pollution percentage in

Figure 3. While PFP-DA maintains a low, steady pollution percentage, both LFU-DA and LRU both increase significantly. And, while LFU-DA does maintain a reasonably good hit rate throughout, the percentage does drop, and interestingly, starts out substantially lower than with PFP-DA.

Let us consider the AT (Advanced Topology) test results, with a single attacker and varying of the request frequency.

Again, with the Advanced Topology in

Table 7 and

Table 8 we see that PFP-DA dominates the other two algorithms, especially in terms of hit rate. For routers R0, R2, R3, and R4, the hit rates are quite low, as before. This is largely due to them not being connected directly to any, or in the cases of R2 and R4, not many consumers. For a network design perspective, the routers with very low hit rates in such simulations might be good candidates to be regular non-storage routers, since their contributions are mostly negligible for all three algorithms.

We once again turn our attention to router R1. Running PFP-DA, R1 maintains around 16.6% to 16.9% hit rate throughout all attack frequencies. LFU-DA also appears to be reasonable resistant to attack, even increasing overall hit rate at 1200 attack frequency. This seems odd, but largely stems from natural fluctuations between launch scenarios.

There remains no question, however, as to which algorithm performs best. PFP-DA maintains the highest percentage of overall hit rate. Considering the top 50 items, PFP-DA has anywhere from 20-30% better hit rate than LFU-DA.

4.3.3. Varying Number of Attackers

To further understand how these three algorithms work under different conditions, we turn our attention to varying the number of attackers (or more correctly, the number of faces under attack that are dominated by the attackers.) In the scenarios used for these tests, the cache size is 100 (1%), the attackers’ request frequency is 720 requests/second, and the regular consumers request at 120 requests/second. Arguably it is reasonably difficult for attackers to overwhelm many faces on a content storage router, but we wanted to test out the algorithms’ performance under stressful conditions. If any attack variation will have a significant impact on PFP-DA, it would be a larger percentage of attackers. PFP-DA would not benefit from normalizing contributions directly, as it did with the single attacker, varying frequency scenarios.

The data in

Table 9 for the Simple Topology gives us insight into the typical performance of algorithms, including when there are no attacks occurring. For ST, since there are 10 total consumers, 1 attacker is 10%, 3 attackers is 30%, and so on. We tested variations from 0 attackers all the way up to 7 attackers, which is 70%.

In Figure 6, the pollution percentages for LFU-DA and LRU remain very similar, with PFP-DA outperforming both from about the 10% up to the 7-attacker (70%) scenarios. At around the higher percentage of attackers, the gap closes substantially, as PFP-DA is overcome with cache pollution.

Important to note, however, is that the quality of content remaining in the cache is not captured by the overall cache pollution percentage data. The hit rates give us a much better picture of this, in Figure 7 and Figure 8. Both the overall and top 50 item hit rates take on very similar shapes, graphically. LRU, largely by coincidence, overtakes LFU-DA around the 50% attacker mark. This is largely because LFU-DA is based on request frequency, while LRU is not. Therefore, LRU depends entirely on recency, and is affected only due to attacker content being more recently accessed as the number of attackers increase. Thus, the LRU data is arguably affected indirectly, whereas LFU-DA and PFP-DA are primarily affected by frequency, which means they are directly affected by incoming frequencies.

The difference between PFP-DA and both LRU and LFU-DA is remarkable. Even as the number of attackers increase, and PFP-DA is affected, it still performs substantially better than LRU and LFU-DA. We note that PFP-DA has a better hit rate (overall) by 5-9% during the increase of attacks. Even more interesting, is that PFP-DA still maintains almost 35% hit rate for the top 50 items, even as LFU-DA is entirely overwhelmed.

Perhaps most remarkable scenario is the 0% (no attacker) scenario. This clearly shows PFP-DA is superior to both LFU-DA and LRU by about 6% better hit rate overall, and around 30% for the top 50 items. This demonstrates that PFP-DA is the best cache replacement algorithm overall, even during periods where no attack is being launched. The explanation for this is that because of the normalization across the multiple faces, the items that remain in the cache give a truer and fair indication of what is popular, not just popular across one or two faces with higher frequencies of request. Depending on the traffic arriving at a given router, the popularity of content arriving at each of the faces are not necessarily homogenous, and in fact, might vary significantly based on origin of requests.

The results for the “no attacker” scenario are displayed graphically in Figure 9, which charts the moving average with an x-axis logarithmic scale. Clearly, PFP-DA outperforms LFU-DA and LRU for the top content objects, maintaining a very strong hit rate until around the item 100, where the results are less clear. Our previous results show that PFP-DA performs better with maintaining the most popular items in the cache, and this figure reinforces that PFP-DA is better, even with no active attack.

4.3.4. PFP-β Results

As discussed earlier, PFP-β (PFP-Beta) takes a β parameter, which acts as the exponent to the denominator for each of the contributions from faces, during the overall popularity calculation. Equation 4 is repeated below and expanded to demonstrate the use of β.

The lower the β, the smaller the numeric difference between the per-face contribution for each item and the top item. This causes content objects that have interests received from multiple faces to be favored substantially. The mechanism for this behavior is described in more detail in § 3.3.

The motivation for this variation on PFP-DA is to see if we can further lower cache pollution and increase hit rate. Through our initial tests, we have made some very interesting discoveries.

Table 10.

PFP- β with single attacker, cache size of 100, beta of 0.05, varying attack frequency.

Table 10.

PFP- β with single attacker, cache size of 100, beta of 0.05, varying attack frequency.

| Attacker Speed |

Pollution % |

Hit % |

top 100 |

top 50 |

| 720 |

0.00% |

22.76% |

87.98% |

98.83% |

| 840 |

0.00% |

22.81% |

87.97% |

98.83% |

| 960 |

0.00% |

22.84% |

87.98% |

98.83% |

Firstly, we can observe the effects (or lack thereof) of varying the attack speed of the single attacker. The pollution is 0%, which is impressive. The hit rates are substantially better than the single attacker scenarios we tested for PFP-DA (see

Table 6.) Of course, with PFP-DA, the regular Simple Topology was used, with 10 nodes attacked to the router, whereas our PFP- β was tested with the Larger Simple Topology (LST), which has 20. However, we will find that even with two attackers (10%) against the LST, considering the coordination and the consistency of percentage, the pollution will remain at 0%, with almost identical hit rates.

Therefore, we can conclude that if we consider the PFP-DA tests from earlier to be a special case of PFP- β where β = 1.0, that the smaller β = 0.05 for essentially the same variations, performs approximately 16% better in terms of cache pollution, approximately 3.7% better for overall hit rate, about 25% better for the top 100 items (by Zipf-like distribution), and about 23% better for top 50 items (98.83% vs 75.53%, for a rate of 720.) Astonishingly, the top 50 items experience just under 99% hit rate with our β = 0.05. Although 75.53% was incredibly good, and totally outperformed LFU-DA (50% top 50 hit rate), our β = 0.05 tests far surpass our previous PFP-DA tests in terms of small attacker percentage with varying attacker frequency.

Secondly, we tested variations of β value, keeping the number of attackers at 2 with attack frequencies of 720 each, a cache size of 100. As we see in

Table 11, increasing the β value increases the pollution percentage, and decreases the hit rates in these scenarios.

Ceteris paribus, as β moves toward the regular PFP-DA (β = 1.0), the performance drops.

Thirdly, we held the number of attackers at 2 with attack frequencies of 720 each, a constant β = 0.1, and varied the cache size. As more spaces become available, the pollution percentage increases extremely slightly. However, it is negligible, even for a cache size of 500 (5% of the content space), as only a few items, accounting for 0.4% of the entire cache, can make it in to the content store’s cache.

The overall hit rate increases significantly, as would be expected since more items can reside in the cache, overall. The top 100 and top 50 hit rates increase slightly, but they are so close to 100% already, there is little room for improvement.

In

Table 13 we see where the PFP-β falls short. Although the performance of PFP-β is better than PFP-DA for small percentages of attackers, PFP-β performs worse than PFP-DA when the number of attackers increases. In other words, it appears that lower β values are resistant to cache pollution under a small percentage of attackers (less than 15%, for example), but higher β values (such as the original PFP-DA, technically holding β = 1.0) allow for more resistance against larger percentages of attackers.