1. Introduction

While catastrophic tanker accidents resulting in marine pollution have dramatically reduced in recent decades, to the order even of 90% from their levels in the 1970s [

1], oil trade by sea along with tanker tonnage continued to increase. On the basis of the latest full data for maritime trade, oil carried by sea has multiplied by a factor of two between 1971, before the oil shock of 1973, and 2021 [

2]. Following demand developments, the deadweight tonnage of the world tanker fleet followed a similar course, occasional corrections - such as the first year of the COVID-19 pandemic – notwithstanding [

2], despite the continuous reduction of the oil tanker fleet share in global tonnage as the dry fleet took the top place within the first ten years of this century [

2,

3]. More recently, geopolitical factors, ranging from trade sanctions to open wars, have resulted in the reshuffling of trade routes, leading to extensive use of transshipment practices, compounding thus the risk of marine pollution through operational mishaps. Such exogenous disturbances to optimal routing and operations refocus the interest on vessel incidents with oil spill potential and on the factors which may lead them to develop into full accidents with disastrous consequences.

In general, while the long-term impact of regulatory and operational developments has yielded spectacular results on marine pollution incidents, the probability of a catastrophic accident has not been zeroed. As literature has underlined in the past, the stochastic element in the evolution of exogenous unpredictable factors [

4], especially of the ones in the termed by [

5] “Black Swan” category [

6], impacting on oil spills and their distribution. In the case of tanker accidents, research had pointed earlier to the need of preparedness in terms of appropriately educating populations at risk to facilitate optimal management of tanker accidents as the latter evolve [

7]. Also, as oil spills can be created through leaked marine bunkers, accidents in other categories of vessels such as recently these involving containerships highlight again the issue of public awareness [

8].

With a view to limiting public misinformation, the paper advances the E-S.A.V.E online platform, part of the risk management research project AEGIS+ funded by Greece and the European Union, as suitable support to responsible and accessible information of the general public in case of marine accidents with pollution potential. The platform: a) meets the needs of different users as revealed by a survey run across groups of them, b) uses an appropriate Web Geographic Information Systems (webGIS) environment, c) cooperates with public authorities, for the reliable update of automated systems, and d) employs an artificial intelligence (AI) supported tool for social media monitoring. It is expected that the E- S.A.V.E platform, providing also through its site access to educational and information resource-national and international - on marine environmental protection and sustainable maritime logistics, can minimize the misinformation of the public and, indirectly - but eventually significantly - maritime transport risks also. After providing a general overview of the impact of significant oil tanker environmental disasters on the evolution of the regulatory framework, the authors review in

Section 2 research on the role of information in population reactions during the management of marine accidents.

Section 3 presents the survey design for exploring the usefulness of the information platform Electronic Shore Awareness of Vessel Emergencies (E-S.A.V.E). Informed by the survey results, the authors showcase in

Section 4 the steps for constructing this original platform for mitigating misinformation of populations exposed to the risk of marine pollution during shipping traffic incidents in coastal and inland areas.

2. Materials and Methods: literature review of the potential of E-S.A.V.E

2.1. Oil spill marine accidents and impact on regulation

As pointed earlier in [

7], despite the extensive regulation and measures for marine pollution mitigation and compensation (

Table 1), residual effects of shipping accidents, especially involving tankers, linger long not only in terms of traceable residues in the marine environment but also in terms of reputation for produce and local resources in general, impacting negatively on regional economies.

Oil tanker accidents are historically the most important source of major oil spills, yet they are not an exclusive one. Oil leaks in the marine environment from drilling, such as this due to a rig accident in the Gulf of Mexico in 2010, have attracted public interest as well as they created considerable marine pollution, with the Deepwater Horizon spill considered one of the two major oil pollution accidents to affect US waters [

9]. Still, as

Table 1 shows, major regulatory changes at the international (or regional) level have been often historically a direct or indirect result of major damage to the marine environment, following major vessel accidents turning the focus onto shipping activities. In this respect, the 2002 Prestige oil tanker accident has been a watershed event, putting under the research spotlight the role of reactions of the public beyond the traditionally perceived ones related to compensation claims, protests and involvement in clean-up operations.

As the incident unfolded, from November 13 to the sinking of the vessel six days later [

13], local population reactions and pressures on the political establishment to secure a quick departure of the damaged vessel -instead of proceeding to a transshipment operation- played evidently a role in the sub-optimal chosen course of action which led to the pointing of the role of information in the process [

14]. As the spilling of an estimated amount of around 60000 tons in total of oil to the marine environment -mainly affecting the Galician coast- was completed, intervention of the population to the local and national politicians showcased its potential role in the chain of events which led to that environmental disaster.

2.2. Population reaction to marine pollution: literature review

Public awareness in terms of marine pollution is considered overall a positive factor especially in terms of the Power of Consumer [

15].

However, following the chain of events which ultimately led to the failure to contain Prestige oil spill outside the Galician coast both during the unfolding of the incident and after the sinking of the vessel, highlights the importance of the critical events which led the operation away from a containable transshipment of the vessel’s cargo under strict conditions - eventually minimizing the impact to the environment - to an uncontrollable course of the damaged vessel to the open seas abruptly stopped by the -early in that final voyage- sinking of the ship.

2.3. Oil pollution potential and the role of information networks

Engagement of the general public is one of the aims sought to be achieved through the Ε-S.A.V.E, turning its users from uncoordinated passive receivers of information they may distrust, to even active contributors the way it has been observed in post-accident population involvement in cleanup operations mentioned in [

7] on the basis of [

16].

As a vessel incident with marine pollution potential unfolds, distrust in official sources or placement of trust in media coverage geared towards the sensational instead of the scientifically accurate is not rare; this is either on purpose, for attracting audiences, or through lack of appropriate resources, leading to a distorted perception of the appropriate course among the range of alternative options. Such a distortion can easily be created through these factors alone and can be easily compounded further by the lack of information the general public is bound to have.

Thanopoulou [

7], in their original approach of creating a remedy to this problem, suggested that appropriate information dissemination can address both the issues of distrust in public information and counter media sensationalism. At the start of the 2010s, the S.A.V.E network concept was advanced for educating coastal populations to react in an informed way during vessel incidents based on ad-hoc trained members of coastal and island communities sourced from the sea-related tourist professions to serve as a trusted education and information source in their local communities.

The general idea of such as network was presented to the local media in the summer of 2011 at the Maria Tsakos Foundation – International Centre for Maritime Research and Tradition [

17] followed by a survey to test the level of appeal and applicability of that initial concept in an island or coastal community. However, the analysis of the survey results at the time and the observed negative reactions of the representatives of Seamen Guilds in Galicia [

18] during the Prestige incident [

19], [

20] showed the need for a more comprehensive direct approach putting the emphasis on countering potential media impact on the basis of the familiarization of the public with electronic platforms including for accessing information on risk-creating events.

2.4. Calibrating the E-S.A.V.E platform targeted use: initial platform design

The E-S.A.V.E platform has been designed and constructed by the authors as a solution to public misinformation during marine pollution incidents involving vessels. The general concept was to use AIS data, provided by one of the three original - industry or benevolent Foundations - volunteer supporters of the E-S.A.V.E/AEGIS+ project; it also includes visualized webGIS data for real or near real time monitoring of incidents with a marine pollution potential across the Greek seas. It has been originally designed to interact with social media networks and to offer web links and directions for finding information material on marine environmental protection issues (

Table 2).

2.5. Survey methodology, ID and Questionnaire distribution

Data collection took place in Greece, a world shipping leader and major incoming tourism country with a most significant island and coastal population dispersion, and a major maritime traffic corridor also. The survey ran between August 2022 to March 2023; while this was a wide timespan, no extreme shipping incidents involving oil tanker or other marine pollution took place during that time to influence the perception of respondents during that period. Questionnaires (in Greek) were distributed electronically as a distributed link for completion through a Google form or in their printed version and were completed anonymously. Survey distribution channels were relevant to shipping and marine pollution, a key one being through the Newsletter of one of the project’s original supporters, HELMEPA (Hellenic Marine Environment Protection Association), delivered electronically to thousands of email addresses. In addition, distribution in a printed form took place during conferences relevant to shipping, and seminars/lectures running at the University of the Aegean.

Despite the lengthy and wide-range effort, the number of completed usable questionnaires was 128 out of an initial number of 129 (68 electronically completed and 60 through hard copies). While the sample size could allow some inferences with a degree of certainty, the sample was rather a case of convenience sampling whereby inferences should be considered tentative [

21]. Almost 60% of the respondents had a relationship of work or study with the shipping sector, while two thirds from that group - about 40% of total respondents - had also at least one family member or more related in some form to the sector, with the remaining 40% of the respondents being members of the general public with no connection with shipping.

Targeting a mix of potential respondents, the survey questions (in Greek) were formulated on the basis of simple terms as, to a large extent, the questionnaire was bound to be replied electronically with no supervision. Questions (Qs) were thus calibrated towards average education levels and minimum degree of familiarization with marine operations/pollution related incidents.

3. Results

3.1. Validating platform design through survey feedback

All survey results were considered valuable input by the authors. However, the opinions and suggestions of the aforementioned 40% of respondents, who were not connected to shipping, were considered even more valuable as falling into the general target group of platforms such as E-S.A.V.E; this was especially so for the open ended question included in the survey.

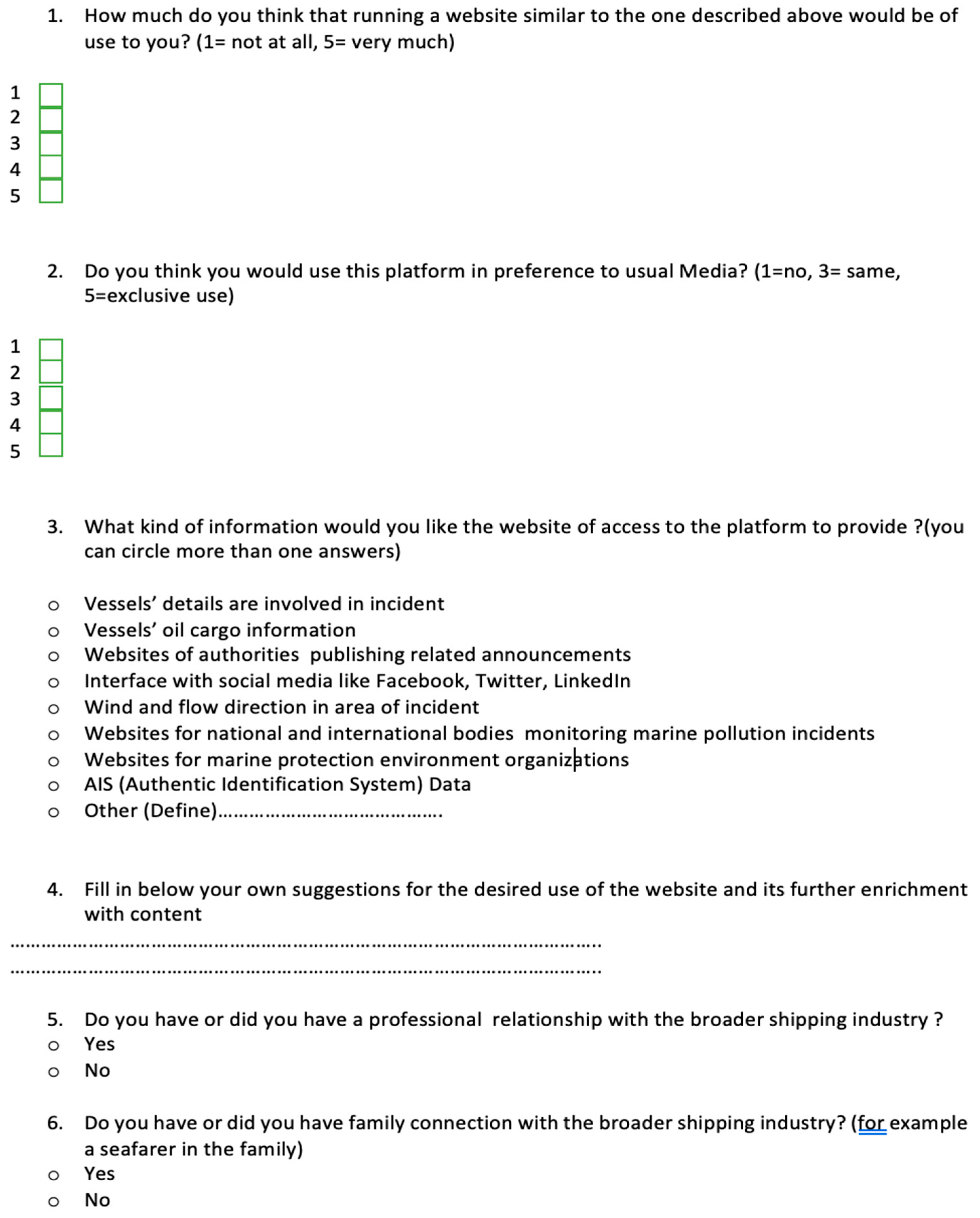

Descriptive statistics for the first two questions on value and alternative use of the E-S.A.V.E platform, i.e., Q1 “How much do you think that running a website similar to the one described above would be of use to you?” and Q2 “Do you think you would use this platform in preference to usual Media?” are presented in

Figure 1.

Figure 1 shows the mean, median, standard error, variance and sample mode values of the provided answers for Qs 1 & 2. The Likert scale provided ranged from 1 to 5, corresponding in linguistic terms from ‘No use at all’ to “Very much” or ‘Exclusive use’ respectively, as shown in detail in

Appendix A.

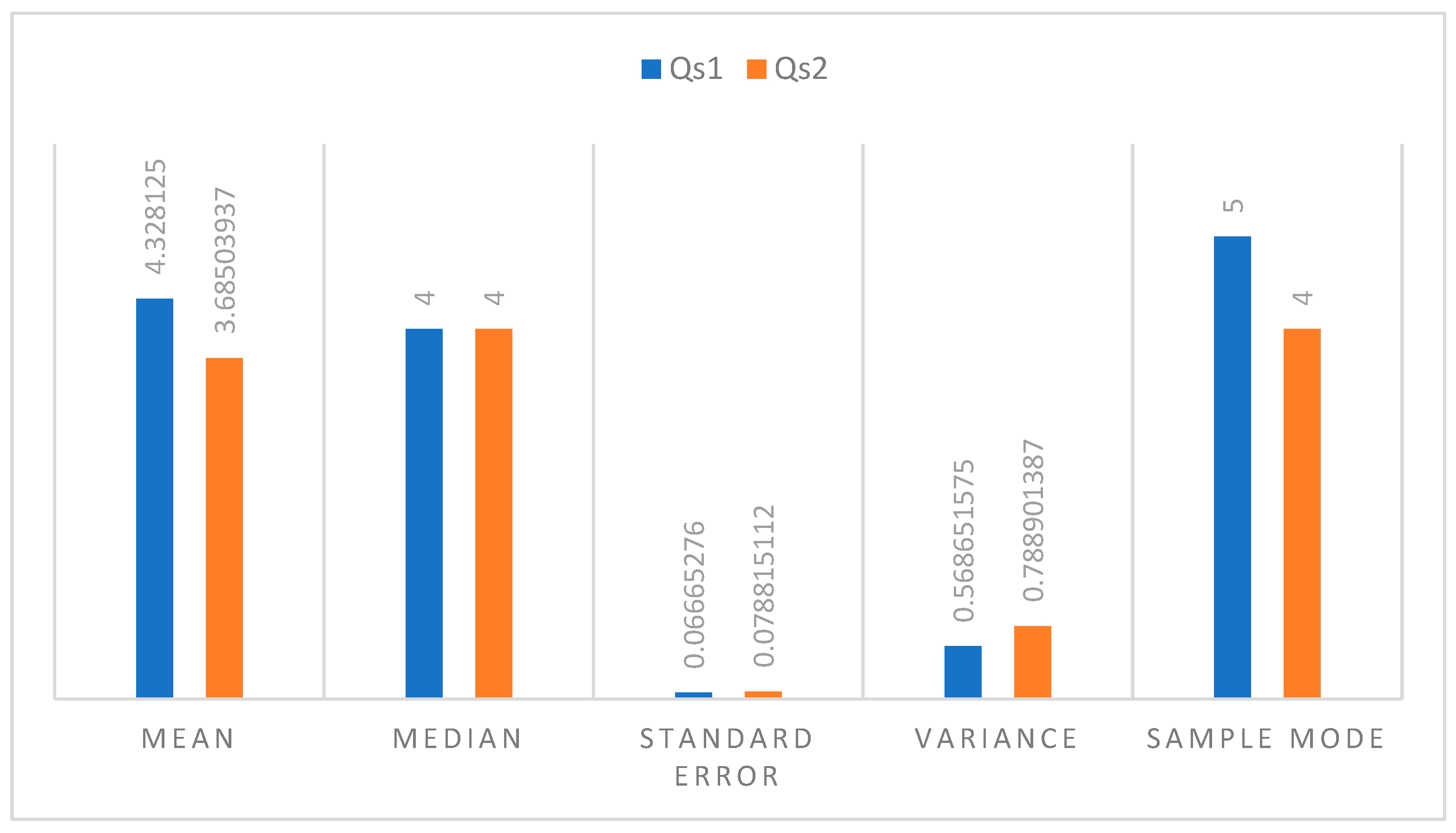

Answers given for Q1 averaged to 4.33 showing the perceived high value of developing a research-based website platform with information related to marine accidents and oil spills; moreover, the central tendency of the answers was at the greatest value range as shown in

Figure 2, below.

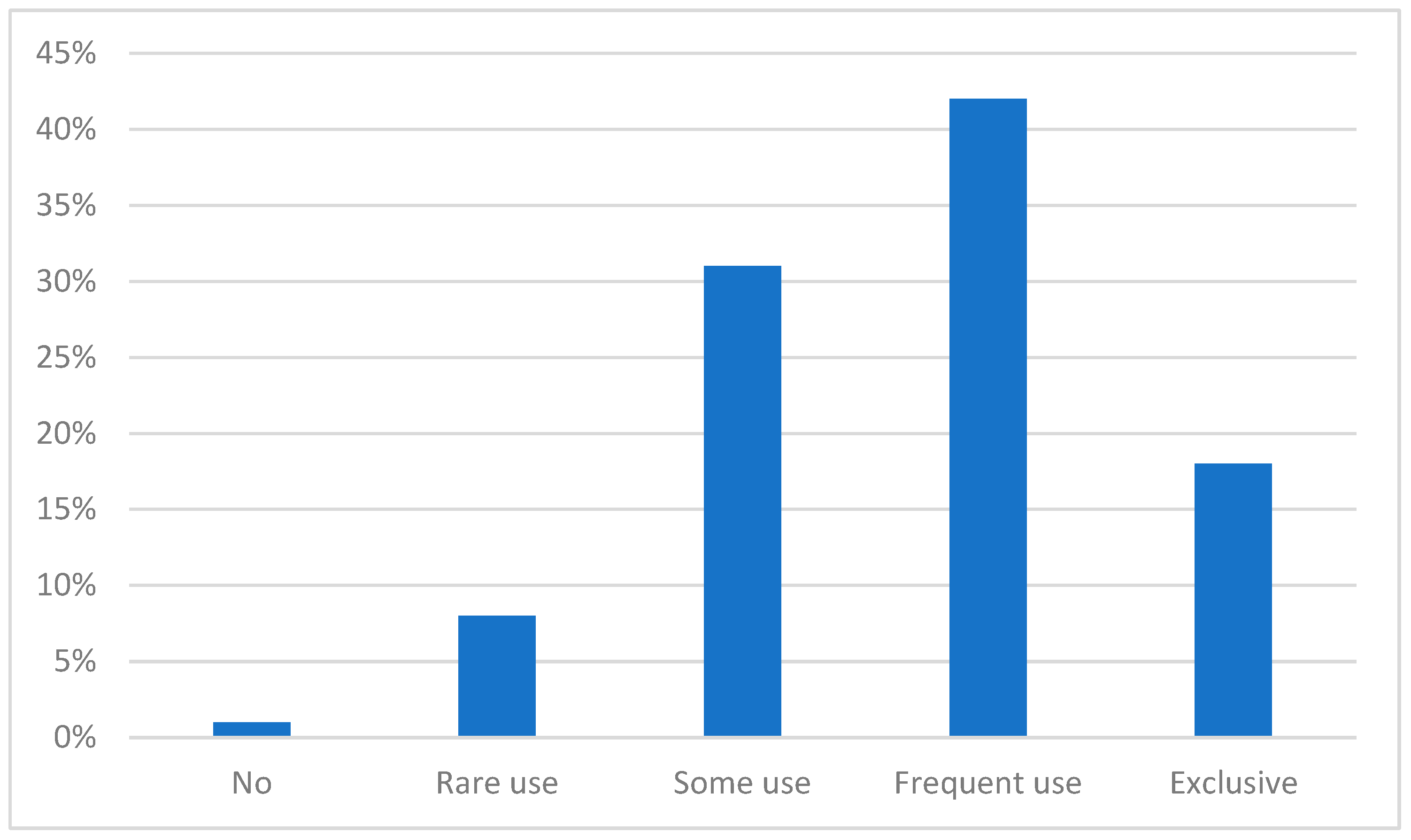

Q2 (

Figure 3 below) required evaluating the use of a platform like E-S.A.V.E in preference to usual media (

Appendix A) on the basis of a five-point Likert scale.

The mean value for responses to the question is 3.68 which is less than the value of 4 corresponding to ‘Frequent use’ so the expectation is that the platform will be used more than usual media. In addition, as 42% of participants anticipate a frequent use of platform, overall frequent and exclusive use add to 60% of respondents finding the E-S.A.V.E proposition more attractive or of exclusive attraction as a source of information.

Furthermore, answers from open question (Qs 3) -at which user were invited to complete suggestions for site enrichment- could be classified in six groups:

As much information about the incident as possible: Such proposed was recorded as: map area of incident; weather conditions; local authorities contact information; P&I clubs and classification societies; contact information of tugs; salvage; antipollution and offshore support vessels; medical instructions; type of incident; local weather; protected areas, nearest volunteer teams.

Audio-visual material (either informative from similar situations historically, or real time during progress of incident)

Continuous update of site with free access without advertisements and creation of a Newsletter.

Findings of recent (involved) vessel inspections.

Incident outcomes and stakeholder impacts (qualitative and quantitative)

Information about responsibility for incident

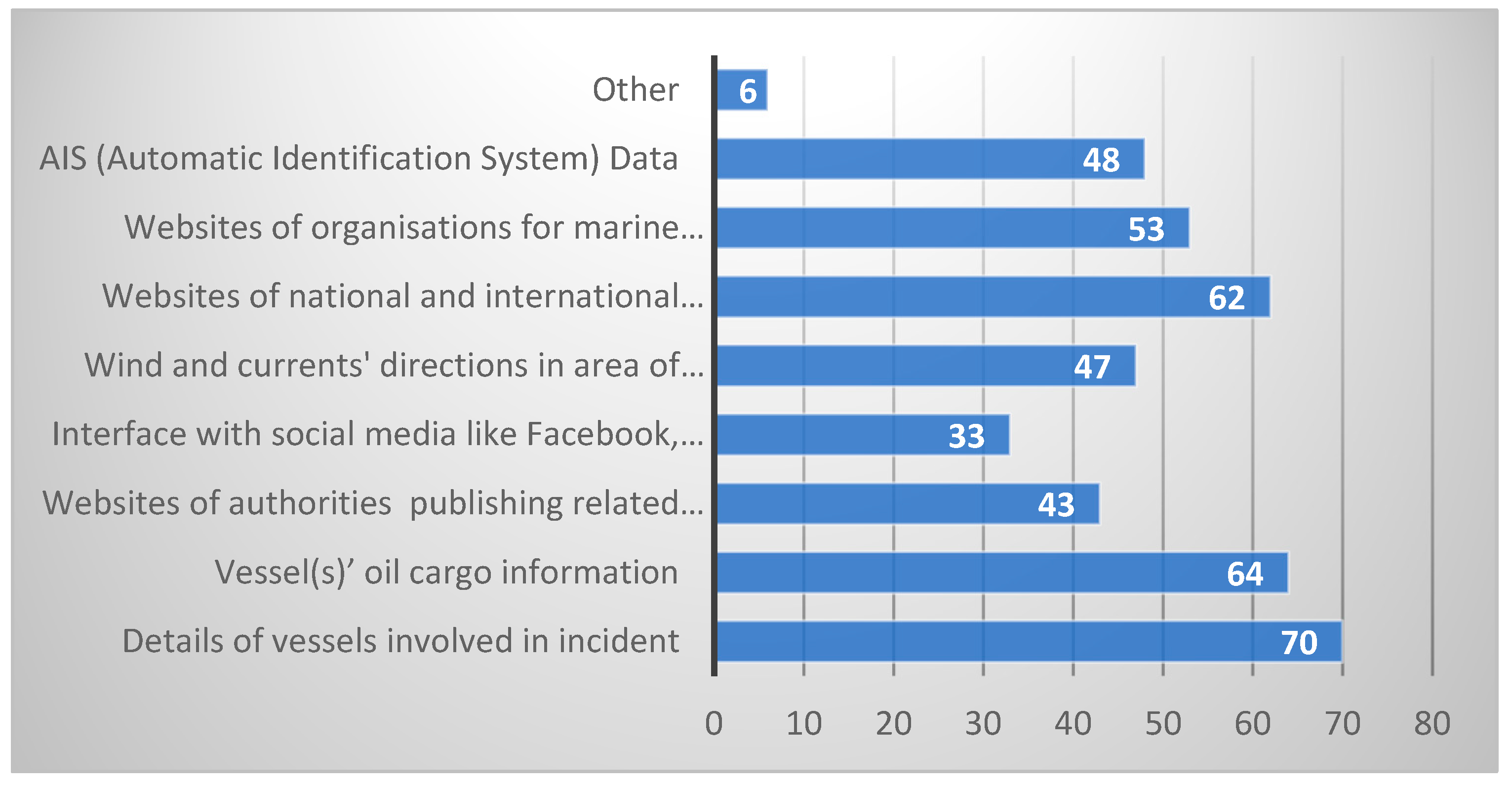

In terms of frequency, as shown in

Figure 4, the most frequent types of information that users think must be provided through the platform and the webpage are:

Vessel(s) details for the ones involved in the incident

Vessels’ oil cargo information

Links for national and international bodies which are monitoring marine pollution incidents

Links for marine environmental protection organizations

AIS (Automatic Identification System) Data

3.2. Survey limitations

In relation to the 2023 survey data, it must be noted that the general public element may not be robustly measured due to electronic responses as unsupervised respondents could ultimately be related to shipping, even if they did not so declare. The reason for hypothesizing this is the survey dissemination channels which to a large extent were related to maritime researchers or shipping related courses at various levels. An effort to rectify this by targeting the general public through airport passengers resulted in no uptake due eventually to lack of visibility of the unstaffed survey booth installed before departures at the local -for most of the researchers involved in the survey- airport. However, as the platform is a pilot project, with crowdsourcing of use cases among both the general public and people involved in shipping, this was a target achieved to a satisfactory extent through the number of questionnaires completed as there was a large number of answers and suggestions to the open-ended question.

3.3. Constructing the E-S.A.V.E platform: website components and essential software

3.3.1. Using Web GIS as the canvas: Web GIS in general

WebGIS applications are designed to be applied to specific case studies with a specific database. A typical web GIS application consists of a server that hosts the web services, a GIS Server for geospatial data and related web services (1. WMS – Web Map Services, 2. WFS – Web Feature Service, 3. WCS – Web Coverage Service, 4. WMTS – Web Map Tile Services, 5. WPS – Web Processing Services, 6. WCPS – Web Coverage Processing Service), and a client, which can be any web browser [

22,

23]. The use of webGIS technology has enhanced the free use of GIS by contributing to a) easy access and dissemination of spatial data, b) visualization and navigation of spatial data, and c) processing, analysis, and modeling of spatial data [

24].

WebGIS applications have several advantages over standard GIS, but also some limitations; their major advantage is that they incorporate all the benefits of the internet, such as mass access to highly accurate geospatial information, which is available worldwide simultaneously due to internet access.

Unlike standard GIS, where the geodatabase resides in a single location, webGIS allows data to be accessed by anyone with an internet connection. Furthermore, this access is free for end users, while the purchase of relevant software for standard GIS can be quite expensive.

Additionally, webGIS applications typically have a user-friendly interface, incorporating limited tools and functions that are relevant to their intended application. This can be seen as an advantage compared to standard GIS, as non-specialized users can become familiar with them more quickly than with complex desktop GIS [

25].

However, webGIS applications also have some disadvantages. The speed of data transfer and processing can be slower compared to standard GIS, depending on internet connectivity [

26]. In conclusion, the advantages of webGIS applications outweigh their limitations. However, they cannot completely replace conventional systems. Nevertheless, when there is a need for many people to access a spatial database, the use of webGIS applications becomes inevitable.

3.3.2. Software selection for constructing the E-S.A.V.E platform

The development of the webGIS application for E-S.A.V.E is designed using ESRI’s software, specifically ArcGIS 10.8.1 Desktop for managing, storing and analyzing spatial data and ArcGIS Enterprise for hosting the GIS Server that provides the web services. The web application provides a user-friendly environment with a simple architecture consisting of the following components:

The spatial database which includes: (i) online maps; are services (map services) published on the GIS Server to be available online and (ii) basemaps provided by the ESRI library.

Auxiliary tools are spatial analysis tools (e.g. measurement tool), or data manipulation tools (e.g. print a map, save attributes etc) available from the ESRI library. These tools facilitate data visualization and presentation.

Navigation tools that assist in exploring the study area.

3.4. The content of the E-S.A.V.E platform

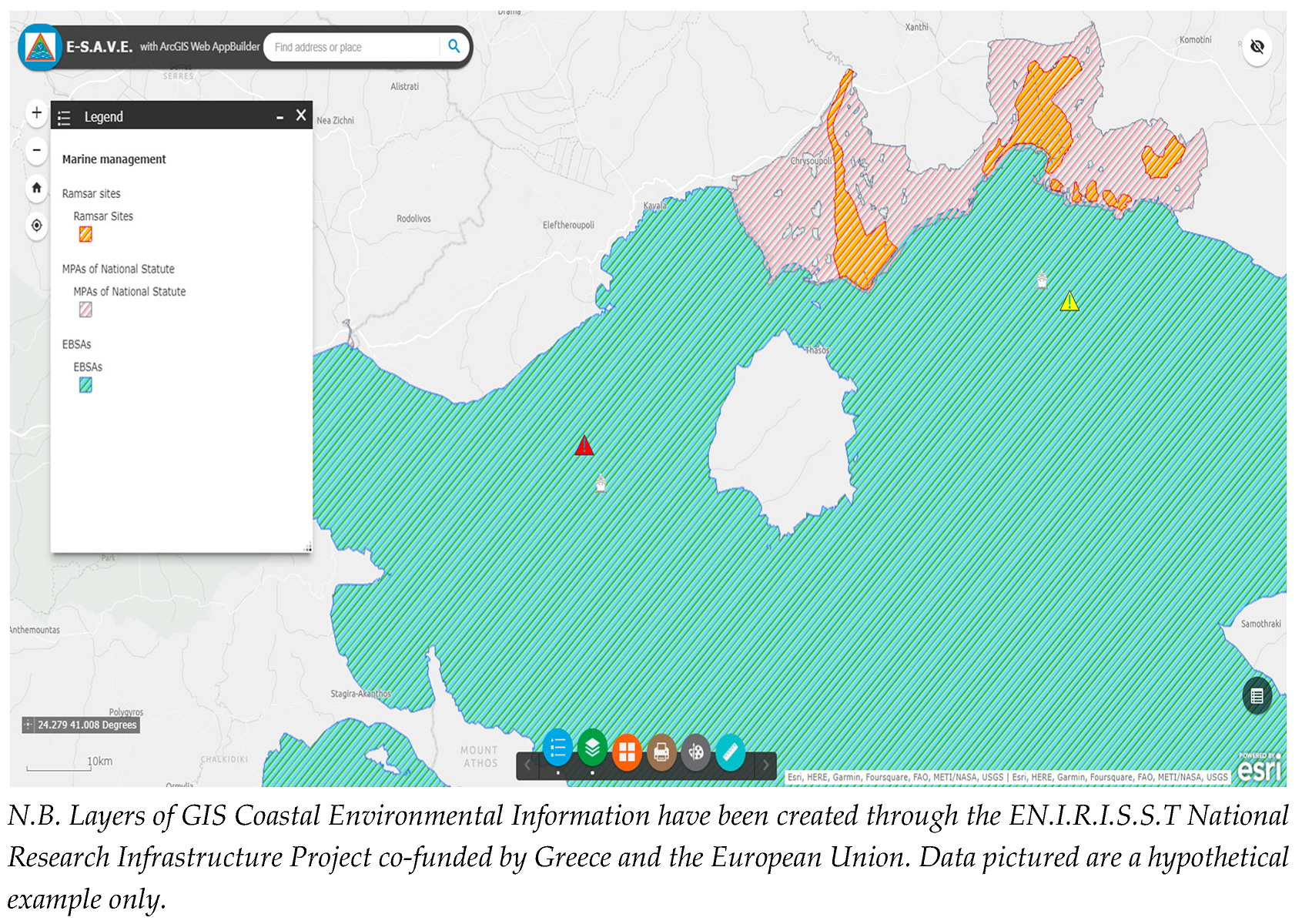

The web interface of E-S.A.V.E has been designed to provide spatial information about both marine incidents and data related to the marine environment through screens similar to

Figure 5 below, where the yellow triangle signals a declared incident and the red one an accident with ascertained marine pollution; the distinction and verification remains with the authorities through the Greek Ministry of Merchant Marine.

The available marine environmental data are divided into the following main groups:

Geographical demarcation of ecological features and habitats, such as seagrass meadows, coastal lagoons, coralligenous aggregations, wetlands, marine caves, important bird areas and habitats of cetaceans, monk seals, and turtles.

Mapping of human activities and infrastructure, including ports, fish farming, recreational and touristic areas (scuba diving locations, bathing waters, etc.)

Designated marine management and protected areas, such as Natura 2000 areas, fisheries restricted areas, Ramsar sites, marine protected areas of National statute (MPAs) and Ecologically or Biologically Significant Marine Areas (EBSMAs).

3.5. Overall architecture of the E-S.A.V.E platform

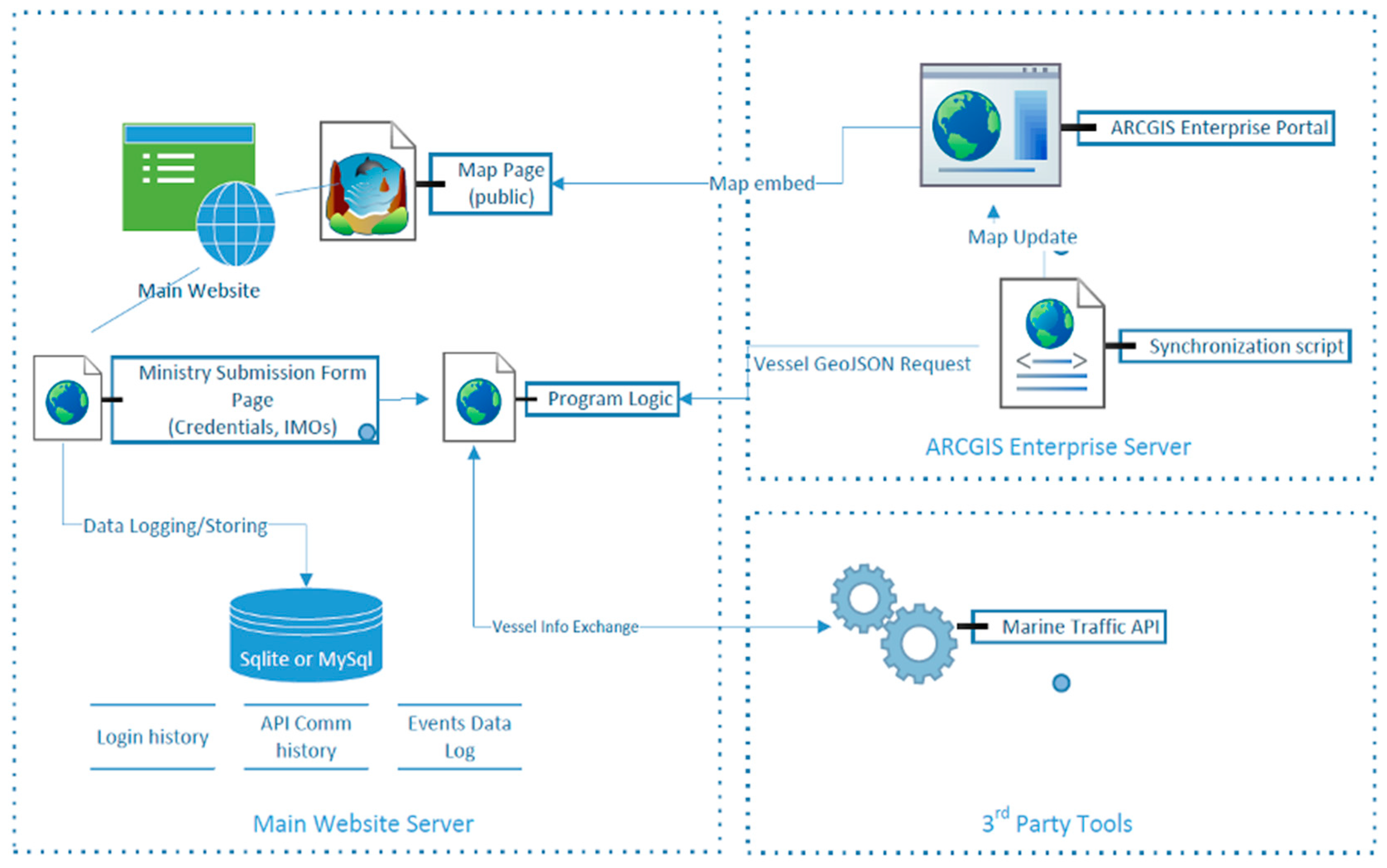

The entities involved in the E-SAVE platform architecture and their communication are as in

Figure 6 below.

The system logic is separated into three major groups: a. The main server; b. the third-party APIs and c. the Geospatial server.

The main server hosts the web portal that is accessed by the public in order to be informed about any occurring incident. It also hosts the private page where the authorities through the relevant ministry submit an incident - via the International Maritime Organization (IMO) number of - at least - one vessel involved - to trigger the information system mechanism.

The backend mechanism firstly checks on the submitter authentication. If the submitter is certified, the log entry of the submitter is written in the login database table and the communication with the Marine Traffic API is triggered. To initiate the communication an authentication token is generated and is used to begin the communication loop. In turn, the communication loop consists of two steps with each one targeting a different API endpoint.

The first step uses the IMO(s) numbers and calls the endpoint that retrieves position and info of each of the ships that are involved in the incident.

The second step uses a mean center of the points of the ships to calculate a bounding box of approximately 15 miles around it and calls the endpoint that returns the positions and info of specific types of vessels (coast guard vessels, oil-spill response vessels, etc) inside the aforementioned bounding box. The whole loop is repeated at regular intervals until the incident is declared resolved or the ship(s) involved sinks or moves away from the bounding area. All of the information of the incident is being recorded into the event table of the database for future reference.

The related data are then transformed to a format compatible with ArcGIS for the ArcGIS portal to retrieve the features layer and in its turn publish the feature layer to the map. The portal refreshes the features status and geolocation in regular intervals and the resulting map is embedded inside the public website hosted in the main server.

The technology described is based on REST APIs, PHP, SQLite and Python and has been developed following a Rapid Application Development (RAD) approach with emphasis in simplicity and stability.

3.6. Feedback from public reactions: E-S.A.V.E as Update - Comment Website from the platform social media account

An innovative application harnessing the power of Twitter and leverages natural language processing techniques to retrieve and analyze comments associated with potential accidents. Our aim is to provide the admin(s) with a robust search algorithm that enables real-time information gathering from Twitter. By extracting valuable insights, our app facilitates timely response and informed decision-making. The Specification Report thoroughly outlines the technical requirements, key functionalities, and design considerations essential for the seamless development and integration of both the website and the Python application.

As part of the task, our objective was to design and implement an application that assists administrators by providing user information in the event of an incident. The developed system focuses on extracting pertinent knowledge from user comments on the social network Twitter related to specific events such as pollution, oil spills, ecological disasters, shipwrecks, sinkings, and more. By leveraging this information, administrators can gain valuable insights to effectively respond to and address the incident.

In the implementation of the application, we have incorporated Machine Learning techniques to enable automated evaluation of key comments, providing administrators with accurate and valuable information. By leveraging Machine Learning, the application can effectively analyze and classify the most relevant comments, ensuring that administrators receive valid insights to make informed decisions.

The application serves a multi-faceted purpose, offering more than just early incident detection and identification of affected communities. It plays a crucial role in directing marine pollution containment efforts, fostering effective communication between stakeholders, and raising environmental awareness. By disseminating information to the public and signaling their main concerns, the app empowers individuals who seek to stay informed and actively engage in combating marine environmental disasters. It enables both individuals and organizations to take immediate and well-informed action, effectively contributing to mitigating impact through trusted channels of feedback communication between stakeholder categories. Upon completion of the execution, administrators are provided with the capability to collect the data and perform cross-referencing of false and malicious comments. This functionality enables them to identify misleading or harmful content and take appropriate actions, such as imposing sanctions if necessary. This ensures the integrity and reliability of the information gathered, fostering a safer and more trustworthy environment within the application. The designed application scans user comments in both Greek and English, searching for specific keywords. The list in

Table 3, below, outlines these keywords in both languages.

The tool-highlighted keywords will be renewed in short intervals providing feedback on the objective and subjective impact of the incident and its consequences on populations affected.

4. Discussion - Conclusions

Public misinformation remains a potential risk in the management of marine pollution accidents originating from vessel traffic. An electronic platform by the symbolic name of E-S.A.V.E (Electronic Shore Awareness of Vessel Emergencies) is being completed for informing the public on developing marine pollution incidents using potential users’ feedback, open software and access to web resources for trustworthy information and marine environmental education promoting sustainable maritime logistics.

E-S.A.V.E presents benefits for both audiences related to shipping, ranging from students to seafarers and shipping and port executives to public authorities and consultancy and research communities. It is also an example of the advantages of open software for the creation of user-friendly electronic platforms providing not only information but also access to educational free resources as well empowering the public and increasing environmental awareness but also familiarization with the operations of the backbone of maritime logistics, i.e. the international shipping industry.

The results from the survey, seeking to gauge the fullest range of use cases, are encouraging since a significant majority finds the platform under development of high or very high value, as it transpires from the mean rating of answers to key survey questions for the value and the role of the platform vis-a-vis traditional media. Design specifications have been validated and further enriched through specific user suggestions, increasing the potential benefit from the construction of the E-S.A.V.E platform. Surveys beyond the one annexed in this paper, will take place at the validation stage at the end of the project in late 2023, as well as in the first year of the platform’s operations addressing users for feedback, following the planned validation with which the designed research effort will be completed.

A voluntary questionnaire for anonymous collection of user profile data will be also linked to the main page opening a google excel menu although such data can be considered as indicative due to lack of control of repetitive submissions. An email esave@aegean.gr will be created to allow further user feedback while such feedback will be made feasible through the platform’s - already created social media.

In terms of further research prospects, data collection through the webpage will be encouraged either via the E-S.A.V.E website, through an open data policy applying all personal data protection provisions to users and contributors.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Helen Thanopoulou, George Georgoulis, Anastasia Patera; Methodology, Helen Thanopoulou, Orestis Moresis, Anastasia Patera, Vassilis Zervakis, Athanasios Kanavos, Orestis Papadimitriou; Software, Athanasios Kanavos, Orestis Papadimitriou, Orestis Moresis; Validation, Vassilis Zervakis, Ioannis Dagkinis; Formal Analysis, Vassiliki Lioumi, Helen Thanopoulou; Investigation, Helen Thanopoulou, George Georgoulis; Data Curation, Vicky Lioumi; Writing – all authors; Writing – Review & Editing, Vassilis Zervakis and Ioannis Daginis; Visualization, Orestis Moresis, Helen Thanopoulou, Anastasia Patera, Vicky Lioumi, Ioannis Dagkinis; Supervision, Vassilis Zervakis; Helen Thanopoulou; Funding Acquisition, Vassilis Zervakis.

Funding

The present article is supported by the research project “Coastal Environment Observatory and Risk Management in Island Regions AEGIS+” (MIS 5047038), implemented within the Operational Programme “Competitiveness, Entrepreneurship and Innovation” (NSRF 2014-2020), co-financed by the Hellenic Government (Ministry of Development and Investments) and the European Union (European Regional Development Fund). Layers of GIS Coastal Environmental Information, planned to cooperate with the E-S.A.V.E platform, have been created through the support of the EN.I.R.I.S.S.T National Research Infrastructure Project (MIS 5027930) funded by the Operational Programme “Competitiveness, Entrepreneurship and Innovation” (NSRF 2014-2020) and co-financed by Greece and the European Union co-funded by Greece and the European Union (European Regional Development Fund).

Informed Consent Statement

Although the appended questionnaire contains no identification or other sensitive personal data provision or questions of a personal sensitive nature, a request for clearance of the questionnaire has been submitted in due course by the authors who participated in the survey design to the Bioethics Committee of the University of the Aegean (not in session currently).

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

The authors have benefitted from comments of referees in the journal submission process and by discussions and encouragement by the now Member of the Greek Parliament Rear Admiral (rtd) of the Hellenic Coast Guard Mr. Stavros Michailidis when Director of the Maria Tsakos Foundation in Chios; thanks are owed as well to the former First Deputy Commandant of the Hellenic Coast Guard Rear Admiral (rtd) Giannis Argirakis and to the officer of the Greek Coast Guard, Commodore Giorgos Maragos (Head of Division) who both took the project under their wing as well as to Commander Georgios Kalogerakis, committed in his role as liaison officer with the research team. Thanks are due to the team of Marine Traffic honoring their support commitment of 2019 as well as to the Director General and top executives of HELMEPA, the third supporter of the research proposal, for distributing our survey link. Thanks are owed also to the team of Marathon Data for their cooperation.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest. N.B. The corresponding author has worked pro bono for the project, in token of the commitment of the entire research team to marine environmental protection and sustainability.

Appendix A. TRANSLATED SURVEY QUESTIONNAIRE (original in Greek)

References

- ITOPF, 2023. Oil tanker spill statistics, 2022. Available online: https://www.itopf.org/knowledge-resources/data-statistics/statistics/ (accessed on 7 July 2023).

- UNCTAD, 2022. Review of Maritime Transport. Geneva: UNCTAD. Annual.

- Gratsos, G.A.; Thanopoulou, H.A.; Veenstra, A.W. The Blackwell Companion to Maritime Economics, Dry bulk shipping, 2012, pp.185-204.

- Georgoulis, G.; Thanopoulou, H.; Vaneslslander, T. Routing and port choice under uncertainty: lessons from a vacuum. Presentation at the ECONSHIP Conference, 2011, Chios Island, June 22-24.

- Taleb, N.N. The black swan: The impact of the highly improbable2007, (Vol. 2). Random house.

- Thanopoulou, H.; Strandenes, S.P. A theoretical framework for analysing long-term uncertainty in shipping. Case Studies on Transport Policy 2017, 5(2), pp.325-331. [CrossRef]

- Thanopoulou, H.; Ventikos, N.; Georgoulis, G.; Moulatzikos, L. Proactive Involvement of Local Population in Oil Spill Incidents: Gauging The Potential Of Informal Information Networks. SPOUDAI-Journal of Economics and Business 2014, Volume 64(2), pp.50-63.

- Wan, S.; Yang, X.; Chen, X.; Qu, Z.; An, C.; Zhang, B.; Lee, K.; Bi, H. Emerging marine pollution from container ship accidents: Risk characteristics, response strategies, and regulation advancements. Journal of Cleaner Production 2022, pp.134-266. [CrossRef]

- Atlas, R.M.; Hazen, T.C. Oil Biodegradation and Bioremediation: A Tale of the Two Worst Spills in U.S. History. Environmental Science & Technology 2011, 45, 6709–6715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- EMSA (European Maritime Safety Agency), 2013. Available online: http://91.231.216.7/ operations/ cleanseanet.html.

- IMO, 2023a. Available online: https://www.imo.org/en/About/Conventions/Pages/International-Convention-for-the-Prevention-of-Pollution-from-Ships-(MARPOL) (accessed on 1 July 2023).

- IMO, 2023b. Available online: https://www.imo.org/en/About/Conventions/Pages/ListOfConventions.aspx (accessed on 1 July 2023).

- Lennon, M.; Mariette, V.; Coat, A.; Verbeque, V.; Mouge, P.; Borstad, G.A.; Willis, P.; Kerr, R.; Alvarez, M. Detection and mapping of the November 2002 Prestige tanker oil spill in Galicia, Spain, with the airborne multispectral CASI sensor. In 3rd EARSEL workshop on Imaging Spectroscopy 2003, pp. 13-16.

- Gimémez, E. The Prestige catastrophe: Political decisions, scientific counsel, missing markets and the need for an international maritime protocol. Universidad de Vigo 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Jacobs, S.; Sioen, I.; De Henauw, S.; Rosseel, Y.; Calis, T.; Tediosi, A.; Nadal, M.; Marques, A.; Verbeke, W. Marine environmental contamination: public awareness, concern and perceived effectiveness in five European countries. Environmental Research 2015, 143, 4–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hur, J-Y. Disaster management from the perspective of governance: case study of the Hebei Spirit oil spill. Disaster Prevention and Management 2012, 21, 288–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pyliotis, T. 2011. Available online: http://www.era-aegean.gr/index.php/en-katakleidi/9-2010-10-25-23-27- 51/1711-2011-07-15-08-41-49 (accessed on 15 July 2011).

- Oceanographic conditions in Galicia and the Southern Bay of Biscay and their influence on the Prestige oil spill. Paper presented at the Vertimar , Symposium on Marine Accidental Oil Spills. Available online: http://otvm.uvigo.es/red_mar../documentos/libro_resumos_vertimar2005.pdf.

- Albaigés, J.; Morales-Nin, B.; Vilas, F. The Prestige oil spill: a scientific response. Marine Pollution Bulletin 2006, 53, 205–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ruiz-Villarreal, R.M.; Gonzalez-Pola; C., Otero, P.; Diaz del Rio, G.; Lavin, A.; Cabanas, J.M. 2005.

- Kitchenham, B.; Pfleeger, S. Principles of survey research: part 5: populations and samples. ACM SIGSOFT Software Engineering Notes 2002, 27, 17–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alesheikh, A.A.; Helali, H.; Behroz, H. Web GIS: Technologies and Its Applications. P. Geospatial Theory, Processing and Applications. 2002, Ottawa, Canada.

- Agrawal, S.; Gupta, R.D. Web GIS and its architecture: a review. Arabian Journal of Geosciences 2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dragićević, S. The potential of web-based GIS. Journal of Geographical Systems 2004, 6, 79–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaig, A. An Overview of Web based Geographic Information Systems 2001.

- Peng, Zhong-Ren. An assessment framework for the development of Internet GIS. Environment and Planning B: Planning and Design, 1999; 26, 117–132.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).