1. Introduction

SARS-CoV-2 is the new coronavirus that caused the disease known as COVID-2019, described in late 2019 after cases were reported in China. By January 2023, SARS-CoV-2 was responsible for infecting over 753 million people worldwide, of which 746 million people survived and 6 million 800 thousand deaths occurred, with a fatality rate of 0.90% [

1].

Despite being able to overcome the disease, survivors are subject to the condition of Long COVID, which is defined as a group of more persistent symptoms that usually begin between 30 days and 3 months after onset in confirmed SARS-CoV-2 individuals and tends to persist for at least 2 months (may last for more than 7 months). These symptoms cannot be better explained by an alternative diagnosis [

2]. They affect an average of 85% of recovered patients, who present cognitive dysfunctions that include: mental confusion, attention difficulties, impairment in executive functions, slowing of movement, agnosia, among others, as the main persistent symptoms [

2], [

3]. In addition to neurological and cognitive symptoms, they may present cardiovascular, musculoskeletal, immune and autoimmune, gastrointestinal, dermatological, pulmonary, neuropsychiatric, among other alterations [

4]. There is an estimate that approximately 200 million people may experience long-term sequelae, even those individuals who have been vaccinated [

5].

Mental confusion and difficulty concentrating (cognitive symptoms) are more common symptoms than coughing (most common physical symptom) during the long course of COVID-19 [

6]. A large number of those affected by the disease report the presence of at least one cognitive symptom during the initial weeks, with it persisting long term, while other symptoms such as memory problems are usually reported weeks later. In general, these symptoms impair the normal functioning of affected individuals' daily routine [

7].

For this study, we developed two hypotheses. First, we hypothesized that the condition caused by Long COVID may lead to neurological syndromes, resulting in significant damage to cognitive functions such as memory, attention, and executive functions. Second, we hypothesized that patients who experienced the disease had significant losses in their physical, mental, and social capacities, which allowed the emergence or worsening of behavioral symptoms of depression and anxiety following the SARS-CoV-2 infection.

Many studies have sought to better understand the side effects of Long Covid. However, it has not yet been possible to perceive a standardization of the neuropsychological assessment model used. Some studies only use screening tests, while others employ more complex batteries, resulting in different collected results. Another factor justifying this study is the limited research with the Brazilian population, specifically with patients who have experienced mild symptoms of Long Covid. This group has been less studied due to not presenting more severe symptoms of the disease.

The present study had as primary objective to assess the current cognitive profile of patients affected by long COVID, by (a) examining their neurocognitive functions; (b) evaluating whether they showed behavioral changes related to depression and mood in the months following the disease; (c) examining whether the time elapsed since long COVID directly impacted these cognitive functions. To achieve these objectives, patients were subjected to a comprehensive neuropsychological evaluation that investigated various cognitive abilities and mood.

2. Materials and Methods

We conducted a cross-sectional observational study documenting neuropsychological effects in 65 adults who developed Long COVID sequelae between 30 days and 3 months after confirmation of SARS-CoV-2 infection. Data were collected between April 2022 and April 2023. Patients diagnosed with COVID-19 confirmed by RT-PCR were recruited. Participants were pre-screened through an online platform (RedCap), where it was necessary to respond to the Long COVID Symptoms Assessment Questionnaire - A-PASC [

8] and present any score on the cognitive symptoms list of the questionnaire. Upon exceeding a score of 10 in the online screening questionnaire, participants were invited to the Psychiatry Institute of the Clinical Hospital, Faculty of Medicine of São Paulo - HC-FMUSP for an evaluation- by a trained physician who confirmed or ruled out a diagnosis of Long COVID symptoms. Subsequently, a battery of neuropsychological tests was applied to the participants at the same location. The assessment was performed after the participant read and signed the written informed consent form.

The sample included patients aged 20 to 75 years with a positive diagnosis of COVID-19 confirmed by RT-PCD nasal swab and the presence of cognitive symptoms between 30 days and 3 months after infection confirmation. We excluded participants with: (1) severe neurological conditions such as major neurocognitive disorders, stroke, lacunar infarct, cerebral atrophy, and others; (2) severe psychiatric disorders such as untreated mood disorders, personality disorders, or psychotic disorders; (3) unstable clinical conditions; (4) less than 8 years of education; (5) use of medications (such as benzodiazepines and anticonvulsants) that can impair cognition; (6) pathological neuroimaging findings (e.g., acute or subacute lacunar or hemorrhagic stroke, and others); (7) a previous history of neurodegenerative and ischemic diseases and complaints of cognitive deficit before SARS-CoV-2 infection. The neuropsychological evaluation was performed in-person in a single session of 1.5 to 2.5 hours. The neuropsychologist provided appropriate instructions for all tests. Responses were recorded in a spreadsheet for non-computerized tests. For each measure, scores were transformed into z-scores.

The following variables were considered: (a) cognition: cognitive screening, estimated premorbid IQ, memory, language, attention, and executive functions; (b) mood: depression and anxiety.

The study was conducted at the Psychiatry Institute of the Clinical Hospital, Faculty of Medicine of the University of São Paulo (IPq-HC/FMUSP) and at the Institute of Psychology of USP (IP-USP) and was approved by the ethics committee under CAAE 52917821.1.0000.0068.

2.1. Neuropsychological Assessment

Tests and scales were applied to evaluate the cognitive functions of patients, including: MoCA to screen for dementia processes; WAT to estimate premorbid IQ; RAVLT to assess verbal memory and learning; Rey Complex Figure Test to evaluate perceptual activity and visual memory, in the copy and memory reproduction phases; Number and Letter Sequencing to assess working memory; Verbal Fluency Test to evaluate attention and executive functions; Naming and Visual Recognition Test (TENOM) to evaluate language; TEADI and TEACO to assess concentrated and divided attention; Five-Digit Test (FDT) to measure individual speed and efficiency, and State-Trait Anxiety Inventory (STAI), Quick Inventory of Depressive Symptomatology (QIDS-SR-16), Barkley Executive Dysfunction Rating Scale (BDEFS) to evaluate Mood and behavioral changes and possible deficits in executive functions, and the WHOQOL-BREF developed and recommended by the World Health Organization (WHO), which emphasizes individual perception and can evaluate quality of life in various groups and situations, regardless of educational level.

All tests performed were corrected using the respective normative criteria of each tool. The MoCA test and the QIDS, STAI-Trait, STAI-State, and WHOQOL scales were evaluated and classified based on their overall score, while the TEACO and TEADI tests had percentiles as their criterion, and all other tests had their scores converted into Z-scores. Covariates associated with participants' neuropsychological performance, such as age, education, and gender, were also considered.

2.2. Statistical Methods

Statistical analysis was performed using SPSS 20.0 software (Statistical Package for the Social Sciences).

According to the aim of our study, the participants were analyzed through two main variables: (a) long covid duration; (b) mood scales (anxiety and depression).

We used descriptive statistics expressed in median, quartiles, and percentages to describe the basic characteristics of our sample and to classify the results of each cognitive test according to its normative table.

The Shapiro-Wilk normality test was performed for the long covid duration and mood scales variables, and all had a non-normal distribution (p < 0.05). Therefore, the analyses were performed using Spearman's correlation.

3. Results

3.1. Demographic Characteristics

The demographic and clinical characteristics of the 65 participants are presented in

Table 1. The mean age of enrolled participants was 44.4 ± 12.45 years, with 18 (27.7%) men and 47 (72.3%) women. The mean time between SARS-CoV-2 infection and the onset of cognitive symptoms was 13.8 months.

Among the participants, 60 (92.3%) reported complaints related to slowed thinking/mental confusion, attention difficulty, memory difficulty, 61 (93.8%) reported difficulty in finding words, 50 (76.9%) reported difficulty in performing more than one task at the same time, and 58 (89.2%) reported the presence of mental fatigue. Additionally, 13 (20.3%) participants experienced these symptoms in the last 6 months, and 51 (79.7%) reported the presence of symptoms for more than 6 months.

3.2. Cognitive Impairments

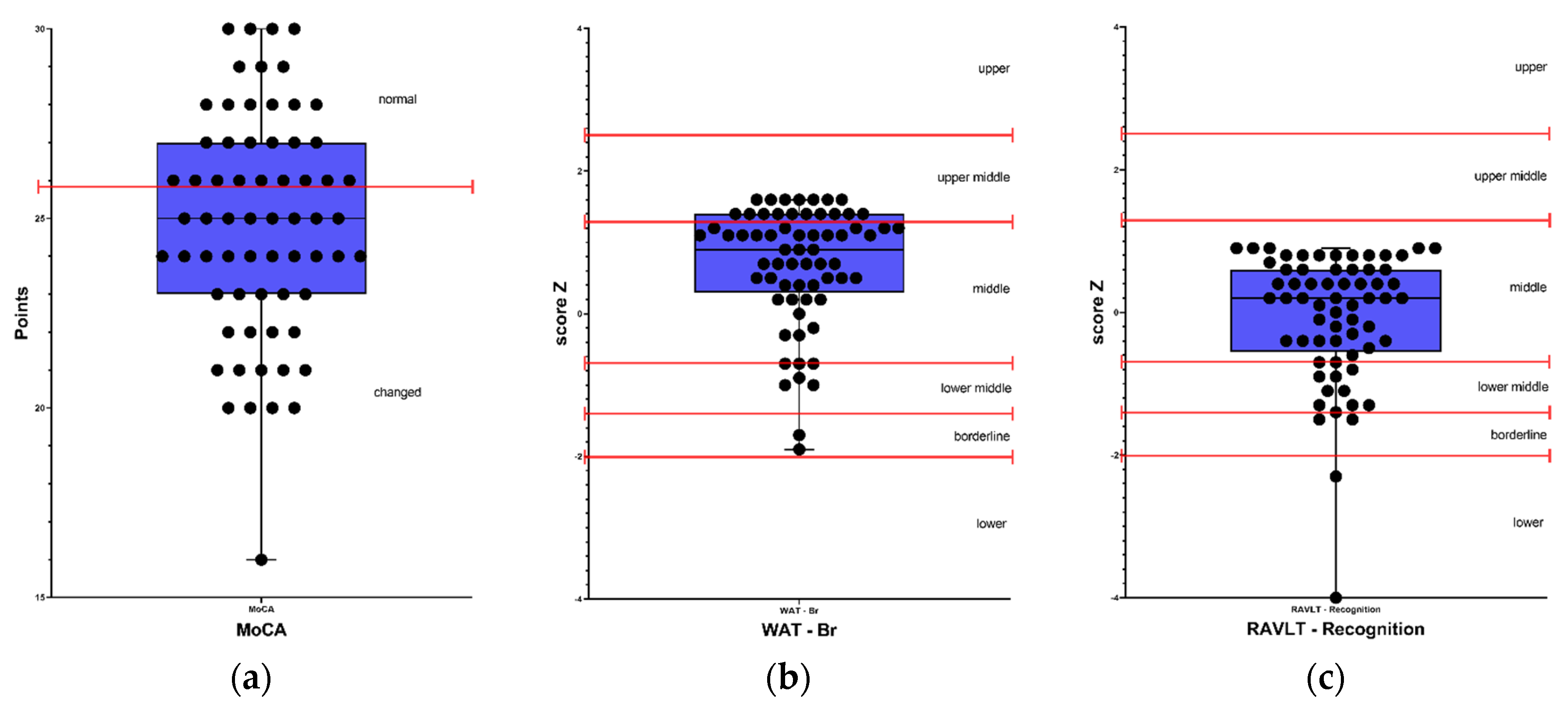

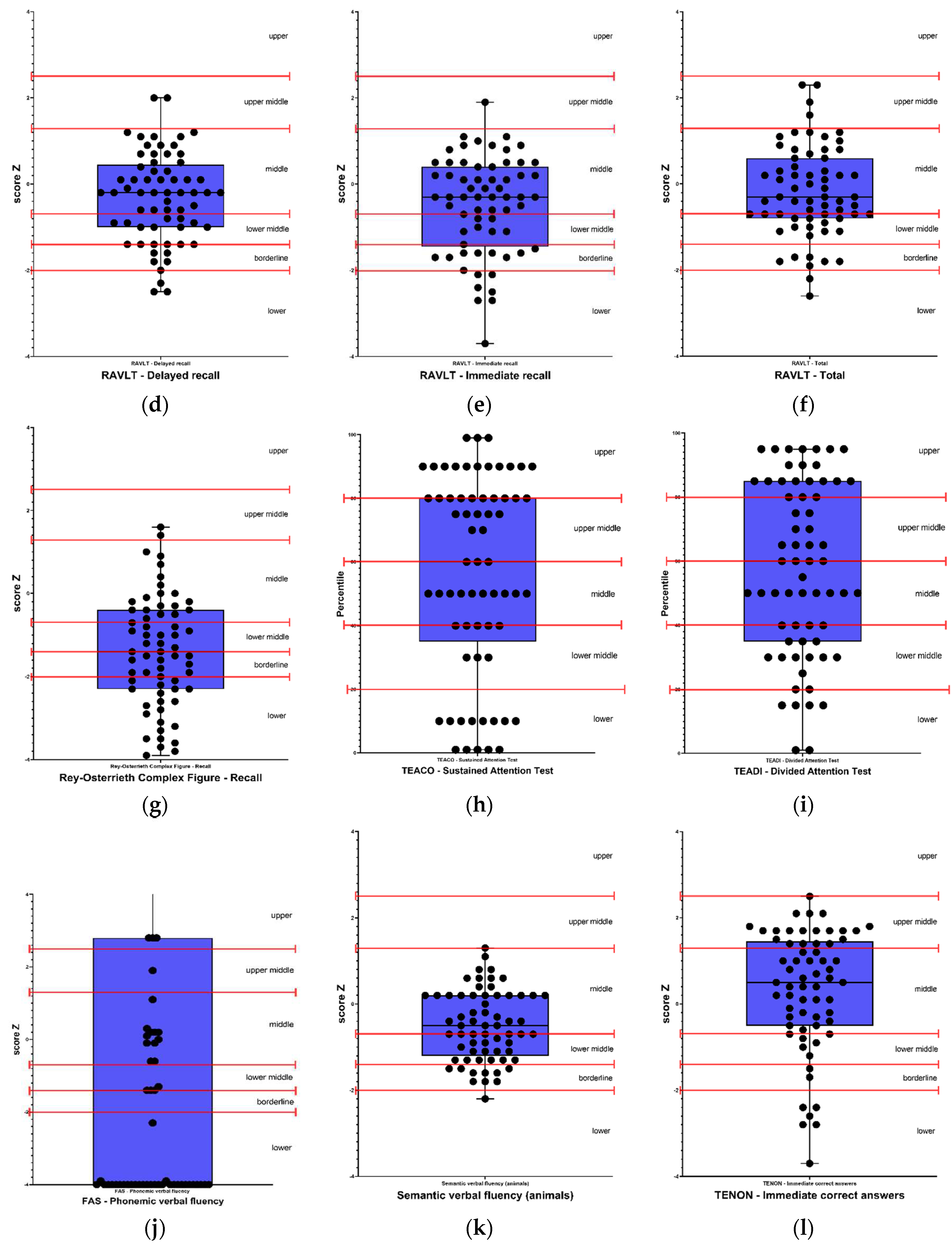

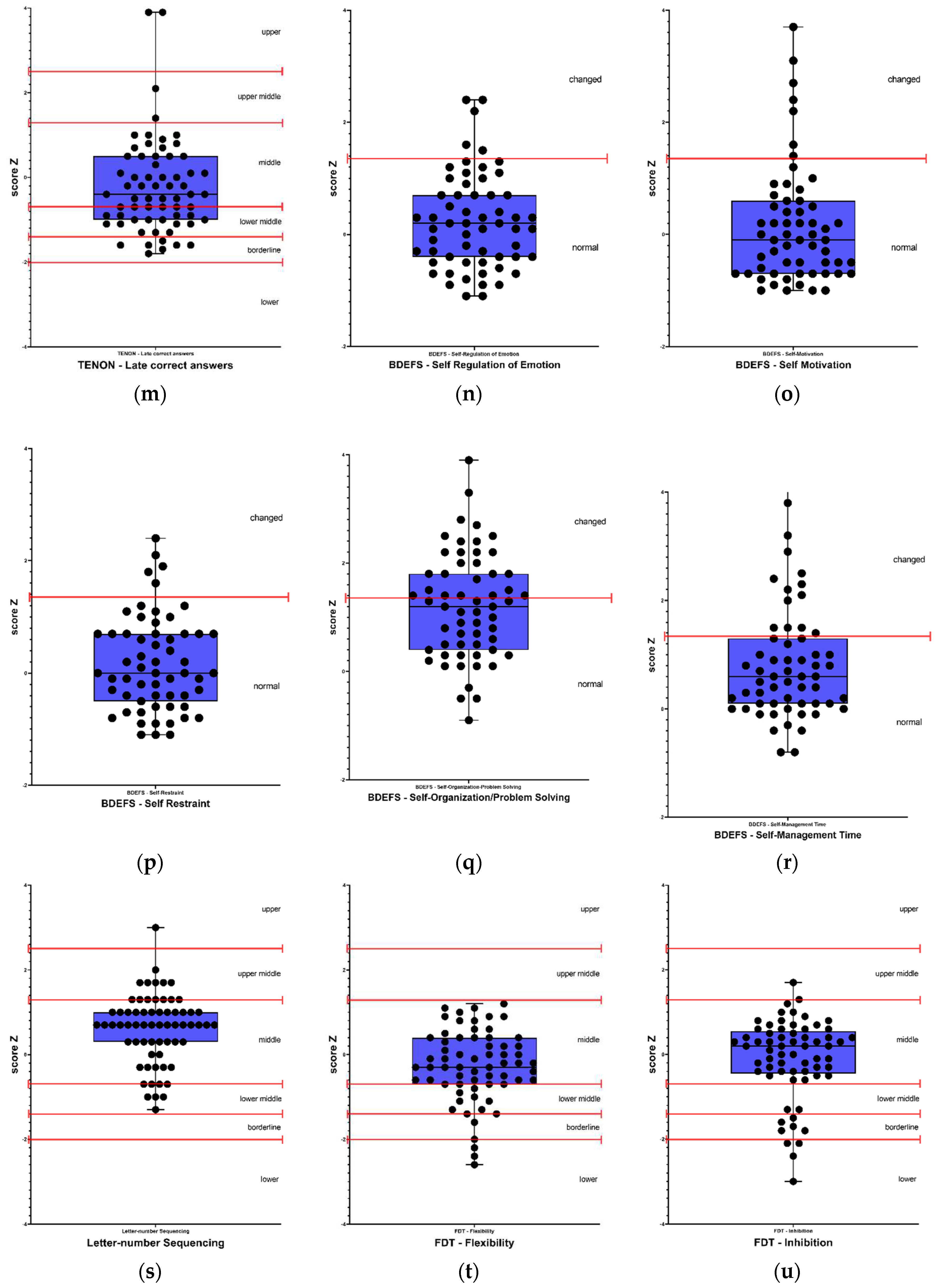

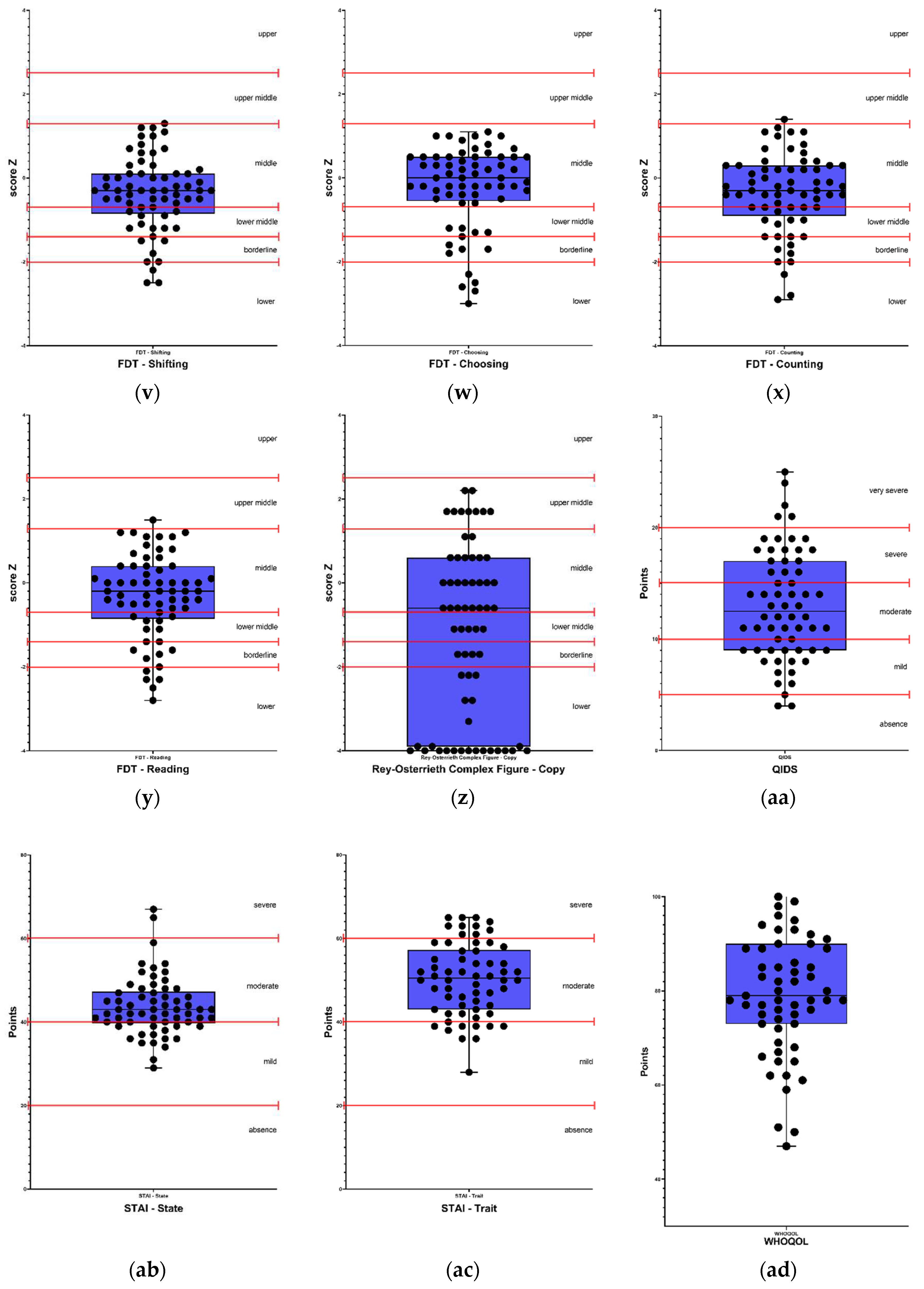

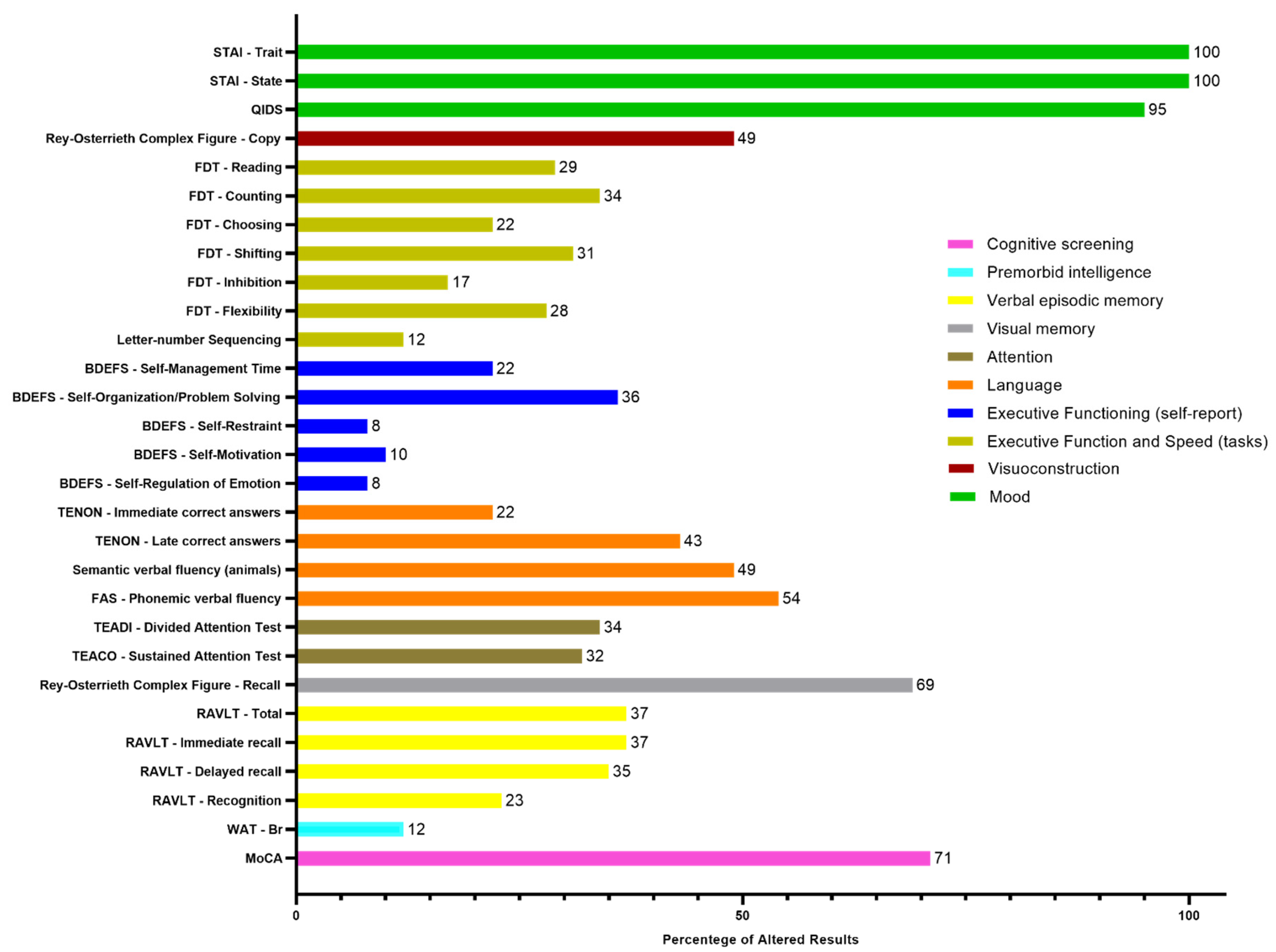

The detailed descriptive classification of the neuropsychological evaluation and the percentages of altered results for each subtest are presented in

Figure 1 and

Figure 2, respectively.

Results classified as below average, borderline, and low were considered as altered results. Therefore, in the cognitive screening, out of the 65 participants, 71% (46) presented alterations in the MoCA test, 12% (8) were altered in premorbid intelligence in the WAT-Br test. Regarding verbal episodic memory, 37% (24) presented alteration in the RAVLT - Total and RAVLT - Immediate recall tests; 35% (23) in RAVLT - Delayed recall and 23% (15) in RAVLT - Recognition test. Regarding visual memory, 69% (45) presented alterations in the Rey Complex Figure - Memory test. In the attention tests, 32% (20) presented alterations in the TEACO - Sustained Attention Test, and 34% (22) presented alterations in the TEADI - Divided Attention Test. In language ability, 54% (35) of participants presented impairments in the FAS - Phonemic Verbal Fluency test, 49% (32) in the Semantic Verbal Fluency test (animals), 43% (28) in the TENON - Late Correct Answers test, and 22% (14) in the TENON - Self-Regulation of Emotion test.

Self-reported perception of executive functions, showed impairment in 8% (5) for self-regulation of emotion and self-restraint, 10% (6) in self-motivation, 22% (13) in self-management time, and 36% (21) in self-organization/problem-solving. On the other hand, in executive function tests, 12% (8) of participants presented alterations in the Letter-Number Sequencing test, 17% (11) in the FDT - Inhibition test, 22% (14) in the FDT - Choosing test, 28% (18) in the FDT - Flexibility test, 29% (19) in the FDT - Reading test, 31% (20) in the FDT - Shifting test, and 34% (22) in the FDT - Counting test. Regarding visuoconstruction abilities, 49% (32) of participants presented alterations in the Rey Osterrieth Complex Figure - Copy test.

Regarding the scales used to evaluate mood, 95% (59) of participants presented depression levels according to the QIDS scale, and 100% (65) of participants presented alterations in anxiety levels both in trait and state, according to the STAI - State and STAI - Trait scales.

3.3. Variables Associated with Cognitive Impairments

The correlations between the duration of Long COVID, anxiety, depression, and cognitive symptoms are present in

Table 2.

As shown by the Spearman correlation coefficient, the longer the participants persisted with Long Covid symptoms, the slower their ability to recall object names became, demonstrating language impairment (ρs=-0.267, p=0.032). The association remained statistically significant even when controlling for the effects of sex, age, and education. On the other hand, anxiety levels tended to decrease (ρs=-0.300, p=0.018).

It was also found that higher levels of anxiety are associated with lower scores in pre-morbid intelligence indices (ρs=-0.347, p=0.006), greater difficulty in time management (ρs=0.280, p=0.032), emotional regulation (ρs=0.284, p=0.029), and less self-control (ρs=0.320, p=0.013). However, the association did not remain statistically significant when controlling for age, sex, and education, as the variables of age and education were significant in explaining the outcome. The association between anxiety and self-control remained statistically significant even after controlling for sex, age, and education (p=0.037).

The results of the depression variable indicate that higher levels of depression are associated with lower performance in semantic verbal fluency (ρs=-0.310, p=0.014). It was also found that higher levels of depression are associated with more difficulty in time management (ρs=0.520, p<0.0001), problem-solving/organization (ρs=0.425, p=0.001), self-control (ρs=0.362, p=0.005), maintaining motivation (ρs=0.386, p=0.003), and emotional regulation (ρs=0.442, p<0.0001). For all of these correlations, the association remained statistically significant even when controlling for the effects of sex and education, although age also significantly influenced the association.

In addition, the greater the cognitive impairment due to time of long COVID sequelae, the higher the level of depression (ρs=,478, p<,0001), the greater the reported difficulty in executive functions such as time management (ρs=,606, p<,0001), ability to organize and solve problems (ρs=,562, p<,0001), self-control (ρs=,319, p=,014), motivation (ρs=,297, p=,022), emotion regulation (ρs=,429, p=,001), and worse the result in the sequence of numbers and letters test (ρs=-,248, p=,046). All of these associations remained statistically significant even when controlling for the effects of sex, age, and education.

Finally, it was also possible to observe a weak but significant negative correlation (ρs=-0.267, p=0.036) between the depression index and trait anxiety. This result indicates that higher values of the depression index are associated with lower values of trait anxiety index.

4. Discussion

The present study examined cognitive functions based on objective testing and self-reported symptoms in 65 participants at an average of 13.8 months after COVID-19 infection. The cognitive results indicate that 71% of participants had changes in cognitive screening, a finding that is consistent with other reports in which the same screening tool was used [

9], [

10] a tool that was used as the main mechanism of evaluation in initial studies on Long COVID and cognition. The most impaired cognitive function was visual memory, with a total of 69% of participants showing at least mild changes, followed by language with 54%, visuospatial abilities with 49% [

11], [

12], verbal episodic memory with 37% [

13], executive functions with 34%, consistent with other findings [

10], [

12], [

14]–[

18], and 34% showing dysfunction in attention. In terms of premorbid intelligence, only 12% of participants had changes, meaning that 88% of participants had preserved cognitive abilities before Long COVID symptoms.

Many studies have used few tools for neuropsychological evaluation or simply used screening tests to consider the results [

20]–[

25], which implies that their conclusions were based on a superficial assessment [

5], [

6], [

26]. To avoid this problem, we conducted a thorough analysis of the tools that would best meet our objectives and for this reason we used a more comprehensive assessment battery, as can be found in other studies [

6], [

12], [

27]–[

32].

These reports were mainly explained by the level of depression, which was observed in 95% of the evaluated participants. In total, 100% of participants presented at least mild changes in anxiety levels related to trait and state. These results agree with studies that show considerable alterations in memory and mood disorders

The reported problems with executive functions were mainly explained by the level of depression, which was observed in 95% of the evaluated participants. In total, 100% of participants presented at least mild changes in anxiety levels related to trait and state. These results are consistent with studies that show considerable alterations in memory and mood disorders [

12], [

20], [

29], [

33].

The linear regression analysis of cognitive symptoms assessed by the neuropsychological test battery showed significant consistency with the level of depression and impairments in executive functions [

34], even when controlled for the effects of sex, age, and education. This demonstrates that participants' perception of their cognitive limitations is consistent with the reality of the evaluation results [

29]. These data also suggest that people with depression are an important risk group for impairments in executive functions when presenting Long COVID symptoms [

12], [

18], [

35].

With the exception of processing speed, the duration of Long COVID did not show a strong correlation with the results of the other cognitive abilities assessed in neuropsychological tests. Age, education, and mood were important predictors of the presented outcomes, as demonstrated in

Table 2 of correlations.

The present study shows that there is no strong correlation between the duration of long COVID symptoms and cognitive impairments. When searching for these answers in other studies, we could see different correlations: some point to the possibility of worsening symptoms [

36], while others indicate an improvement of symptoms over time [

18], [

37], [

38].

When we seek to compare the results of this study with previous studies, we realize a difficulty since many of the selected tests are not applicable in the reality of the Brazilian population. We also notice differences in the criteria for defining impaired functions, the severity of the condition, and the length of long COVID.

This study aimed to evaluate patients with mild cognitive impairment (without the need for hospitalization due to COVID), and the results presented here are consistent with other studies that have reported significant alterations in asymptomatic patients [

12], [

39], [

40].

In general, we can also consider other independent variables such as age and education as important factors for the cognitive impairment reported in the results of this study.

We acknowledge that our study had some limitations. First, we did not compare our sample with a healthy control group of individuals without COVID-19 or cognitive complaints. This absence of a COVID-19 free group to serve as a control group is due to the difficulty in establishing the condition given the facts that COVID-19 is often asymptomatic. However, we used the normative tables of each test, considering age, education, and sex, thus supporting the validity of our results. Secondly, we evaluated a group of patients with mild cognitive symptoms of Long COVID, and it is possible that patients with more severe symptoms may present significant alterations. Nevertheless, our study is one of the few published that focused on the group with mild symptoms.

This sample also had a higher level of education than the general population and consisted mostly of women. These characteristics may be explained by cultural issues related to access to medical care and/or help-seeking behaviors, which are not predominant in the male public.

5. Conclusions

In conclusion, this study investigated patients with mild COVID-19 symptoms and later self-reported and physician-diagnosed Long COVID symptoms. The results presented here corroborate the scientific literature that has been reporting the effect of these sequelae on cognition and mood. In general, they point to the need for physical, cognitive, and emotional treatment, considering that anxiety and depression are highly correlated with Long COVID. In addition, new studies should be carried out to investigate the remission time of this disease and the medium and long-term effects on the daily functioning and cognition of affected patients.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.L., D.F.V., KS and K..S.; methodology, A.L.; software, A.R.B.; validation, D.F.V; formal analysis, P.S. and K.S.; investigation, B.C. and A.L.; resources, D.F.V and A.R.B.; data curation, L.B, A.L. and B.C.; writing—original draft preparation, A.L., K.V., P.S. and D.F.V.; writing—review and editing, A.L., K.V., P.S. and D.F.V; visualization, K.S. and D.F.V.; supervision, K.S., A.R.B. and D.F.V.; project administration, B.C., P.S. and J.S.; funding acquisition, A.R.B and D.F.V. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the São Paulo State Research Foundation (FAPESP 2022/00191-0 to DFV and 2019/06009-6 to ARB), by Brazilian National Research Council CNPq 1A Research Productivity Grant to DFV (314630/2020-1) and by Academy of Medical Sciences (NAFR12_1010).

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted at the Institute of Psychiatry of the Medical School of the University of Sao Paulo (IPq-HC/FMUSP) in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the ethics committee under CAAE 52917821.1.0000.0068.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

All data are available from the main article and supplemental information.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare the following financial interests/personal relationships which may be considered as potential competing interests: AL: No disclosures. BC: No disclosures. PS: No disclosures. BP: No disclosures. RP: No disclosures. JS: No disclosures. LB: No disclosures. MB: No disclosures. AA: No disclosures. ARB SoterixMedical, Flow-Neuroscience and MagVenture, also has small equity in FlowNeuroscience. KS: No disclosures. DFV: No disclosures

References

- WHO, “COVID-19 Weekly Epidemiological Update,” 2023.

- Y. Huang et al., “COVID Symptoms, Symptom Clusters, and Predictors for Becoming a Long-Hauler: Looking for Clarity in the Haze of the Pandemic,” medRxiv the preprint sever for helth sciences, Mar. 2021. [CrossRef]

- L. L. O’Mahoney et al., “The prevalence and long-term health effects of Long Covid among hospitalised and non-hospitalised populations: A systematic review and meta-analysis,” EClinicalMedicine, vol. 55, Jan. 2023. [CrossRef]

- H. E. Davis et al., “Characterizing long COVID in an international cohort: 7 months of symptoms and their impact,” EClinicalMedicine, vol. 38, Aug. 2021. [CrossRef]

- M. C. Campos, T. Nery, A. C. Starke, A. C. de Bem Alves, A. E. Speck, and A. S Aguiar, “Post-viral fatigue in COVID-19: A review of symptom assessment methods, mental, cognitive, and physical impairment,” Neuroscience and Biobehavioral Reviews, vol. 142. Elsevier Ltd, Nov. 01, 2022. [CrossRef]

- M. Ariza et al., “Neuropsychological impairment in post-COVID condition individuals with and without cognitive complaints,” Front Aging Neurosci, vol. 14, Oct. 2022. [CrossRef]

- P. Guo et al., “COVCOG 1: Factors Predicting Physical, Neurological and Cognitive Symptoms in Long COVID in a Community Sample. A First Publication From the COVID and Cognition Study,” Front Aging Neurosci, vol. 14, Mar. 2022. [CrossRef]

- T. Eilam-Stock, A. George, M. Lustberg, R. Wolintz, L. B. Krupp, and L. E. Charvet, “Telehealth transcranial direct current stimulation for recovery from Post-Acute Sequelae of SARS-CoV-2 (PASC),” Brain Stimulation, vol. 14, no. 6. Elsevier Inc., pp. 1520–1522, Nov. 01, 2021. [CrossRef]

- M. Calabria et al., “Post-COVID-19 fatigue: the contribution of cognitive and neuropsychiatric symptoms,” J Neurol, vol. 269, no. 8, pp. 3990–3999, Aug. 2022. [CrossRef]

- B. Biagianti et al., “Cognitive Assessment in SARS-CoV-2 Patients: A Systematic Review,” Frontiers in Aging Neuroscience, vol. 14. Frontiers Media S.A., Jul. 01, 2022. [CrossRef]

- Lauria et al., “Neuropsychological Measures of Long COVID-19 Fog in Older Subjects,” Clinics in Geriatric Medicine, vol. 38, no. 3. W.B. Saunders, pp. 593–603, Aug. 01, 2022. [CrossRef]

- K. Krishnan, A. K. Miller, K. Reiter, and A. Bonner-Jackson, “Neurocognitive Profiles in Patients With Persisting Cognitive Symptoms Associated With COVID-19,” Archives of Clinical Neuropsychology, vol. 37, no. 4, pp. 729–737, Jun. 2022. [CrossRef]

- L. Diana et al., “Monitoring cognitive and psychological alterations in COVID-19 patients: A longitudinal neuropsychological study,” J Neurol Sci, vol. 444, Jan. 2023. [CrossRef]

- L. Muccioli et al., “Cognitive and functional connectivity impairment in post-COVID-19 olfactory dysfunction.,” Neuroimage Clin, vol. 38, p. 103410, Apr. 2023. [CrossRef]

- K. Schild et al., “Multidomain cognitive impairment in non-hospitalized patients with the post-COVID-19 syndrome: results from a prospective monocentric cohort,” J Neurol, vol. 270, no. 3, pp. 1215–1223, Mar. 2023. [CrossRef]

- E. Herrera et al., “Cognitive impairment in young adults with post COVID-19 syndrome,” Sci Rep, vol. 13, no. 1, p. 6378, Dec. 2023. [CrossRef]

- M. Godoy-González et al., “Objective and subjective cognition in survivors of COVID-19 one year after ICU discharge: the role of demographic, clinical, and emotional factors,” Crit Care, vol. 27, no. 1, p. 188, Dec. 2023. [CrossRef]

- Kirchberger et al., “Subjective and Objective Cognitive Impairments in Non-Hospitalized Persons 9 Months after SARS-CoV-2 Infection,” Viruses, vol. 15, no. 1, p. 256, Jan. 2023. [CrossRef]

- Mannan et al., “A multi-centre, cross-sectional study on coronavirus disease 2019 in Bangladesh: clinical epidemiology and short-term outcomes in recovered individuals,” New Microbes New Infect, vol. 40, Mar. 2021. [CrossRef]

- R. Hadad et al., “Cognitive dysfunction following COVID-19 infection,” J Neurovirol, 2022. [CrossRef]

- P. Ortelli et al., “Neuropsychological and neurophysiological correlates of fatigue in post-acute patients with neurological manifestations of COVID-19: Insights into a challenging symptom,” J Neurol Sci, vol. 420, Jan. 2021. [CrossRef]

- P. Ortelli et al., “Altered motor cortex physiology and dysexecutive syndrome in patients with fatigue and cognitive difficulties after mild COVID-19,” Eur J Neurol, vol. 29, no. 6, pp. 1652–1662, Jun. 2022. [CrossRef]

- M. B. Hammerle et al., “Cognitive Complaints Assessment and Neuropsychiatric Disorders After Mild COVID-19 Infection,” Arch Clin Neuropsychol, vol. 38, no. 2, pp. 196–204, Mar. 2023. [CrossRef]

- F. Alemanno et al., “COVID-19 cognitive deficits after respiratory assistance in the subacute phase: A COVID rehabilitation unit experience,” PLoS One, vol. 16, no. 2 February, Feb. 2021. [CrossRef]

- E. N. Aiello et al., “Episodic long-term memory in post-infectious SARS-CoV-2 patients,” Neurological Sciences, vol. 43, no. 2, pp. 785–788, Feb. 2022. [CrossRef]

- Saucier et al., “Cognitive inhibition deficit in long COVID-19: An exploratory study,” Front Neurol, vol. 14, 2023. [CrossRef]

- D. Andriuta et al., “Clinical and Imaging Determinants of Neurocognitive Disorders in Post-Acute COVID-19 Patients with Cognitive Complaints,” Journal of Alzheimer’s Disease, vol. 87, no. 3, pp. 1239–1250, 2022. [CrossRef]

- C. García-Sánchez et al., “Neuropsychological deficits in patients with cognitive complaints after COVID-19,” Brain Behav, vol. 12, no. 3, Mar. 2022. [CrossRef]

- C. Delgado-Alonso et al., “Cognitive dysfunction associated with COVID-19: A comprehensive neuropsychological study,” J Psychiatr Res, vol. 150, pp. 40–46, Jun. 2022. [CrossRef]

- R. Ng, G. Vargas, D. T. Jashar, A. Morrow, and L. A. Malone, “Neurocognitive and Psychosocial Characteristics of Pediatric Patients With Post-Acute/Long-COVID: A Retrospective Clinical Case Series,” Arch Clin Neuropsychol, vol. 37, no. 8, pp. 1633–1643, Dec. 2022. [CrossRef]

- M. Ariza et al., “COVID-19 severity is related to poor executive function in people with post-COVID conditions,” J Neurol, May 2023. 20 May. [CrossRef]

- S. Bonizzato, A. Ghiggia, F. Ferraro, and E. Galante, “Cognitive, behavioral, and psychological manifestations of COVID-19 in post-acute rehabilitation setting: preliminary data of an observational study,” Neurological Sciences, vol. 43, no. 1, pp. 51–58, Jan. 2022. [CrossRef]

- W. Braga et al., “Neuropsychological manifestations of long COVID in hospitalized and non-hospitalized Brazilian Patients,” NeuroRehabilitation, vol. 50, no. 4, pp. 391–400, 2022. [CrossRef]

- Ö. F. Bolattürk and A. C. Soylu, “Evaluation of cognitive, mental, and sleep patterns of post-acute COVID-19 patients and their correlation with thorax CT,” Acta Neurol Belg, Jun. 2022. [CrossRef]

- S. Albu, N. R. Zozaya, N. Murillo, A. Garciá-Molina, C. A. F. Chacón, and H. Kumru, “What’s going on following acute COVID-19? Clinical characteristics of patients in an out-patient rehabilitation program,” NeuroRehabilitation, vol. 48, no. 4, pp. 469–480, 2021. [CrossRef]

- P. Voruz et al., “Frequency of Abnormally Low Neuropsychological Scores in Post-COVID-19 Syndrome: the Geneva COVID-COG Cohort,” Archives of Clinical Neuropsychology, vol. 38, no. 1, pp. 1–11, Jan. 2023. [CrossRef]

- F. Mattioli, C. Stampatori, F. Righetti, E. Sala, C. Tomasi, and G. De Palma, “Neurological and cognitive sequelae of Covid-19: a four month follow-up,” J Neurol, vol. 268, no. 12, pp. 4422–4428, Dec. 2021. [CrossRef]

- H. Del Brutto, D. A. Rumbea, B. Y. Recalde, and R. M. Mera, “Cognitive sequelae of long COVID may not be permanent: A prospective study,” Eur J Neurol, vol. 29, no. 4, pp. 1218–1221, Apr. 2022. [CrossRef]

- S. Amalakanti, K. V. R. Arepalli, and J. P. Jillella, “Cognitive assessment in asymptomatic COVID-19 subjects,” Virusdisease, vol. 32, no. 1, pp. 146–149, Mar. 2021. [CrossRef]

- H. A. Baker, S. A. Safavynia, and L. A. Evered, “The ‘third wave’: impending cognitive and functional decline in COVID-19 survivors,” British Journal of Anaesthesia, vol. 126, no. 1. Elsevier Ltd, pp. 44–47, Jan. 01, 2021. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).