Submitted:

27 July 2023

Posted:

28 July 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

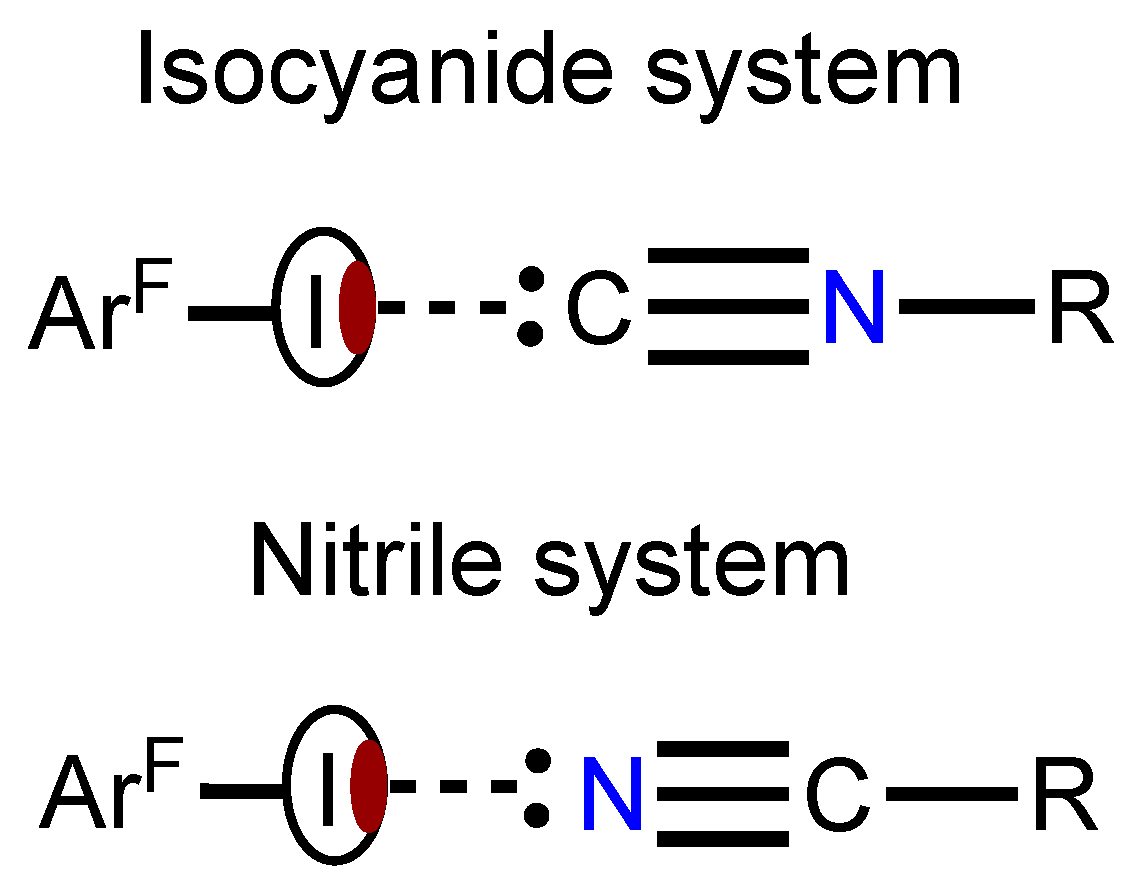

1. Introduction

2. Results

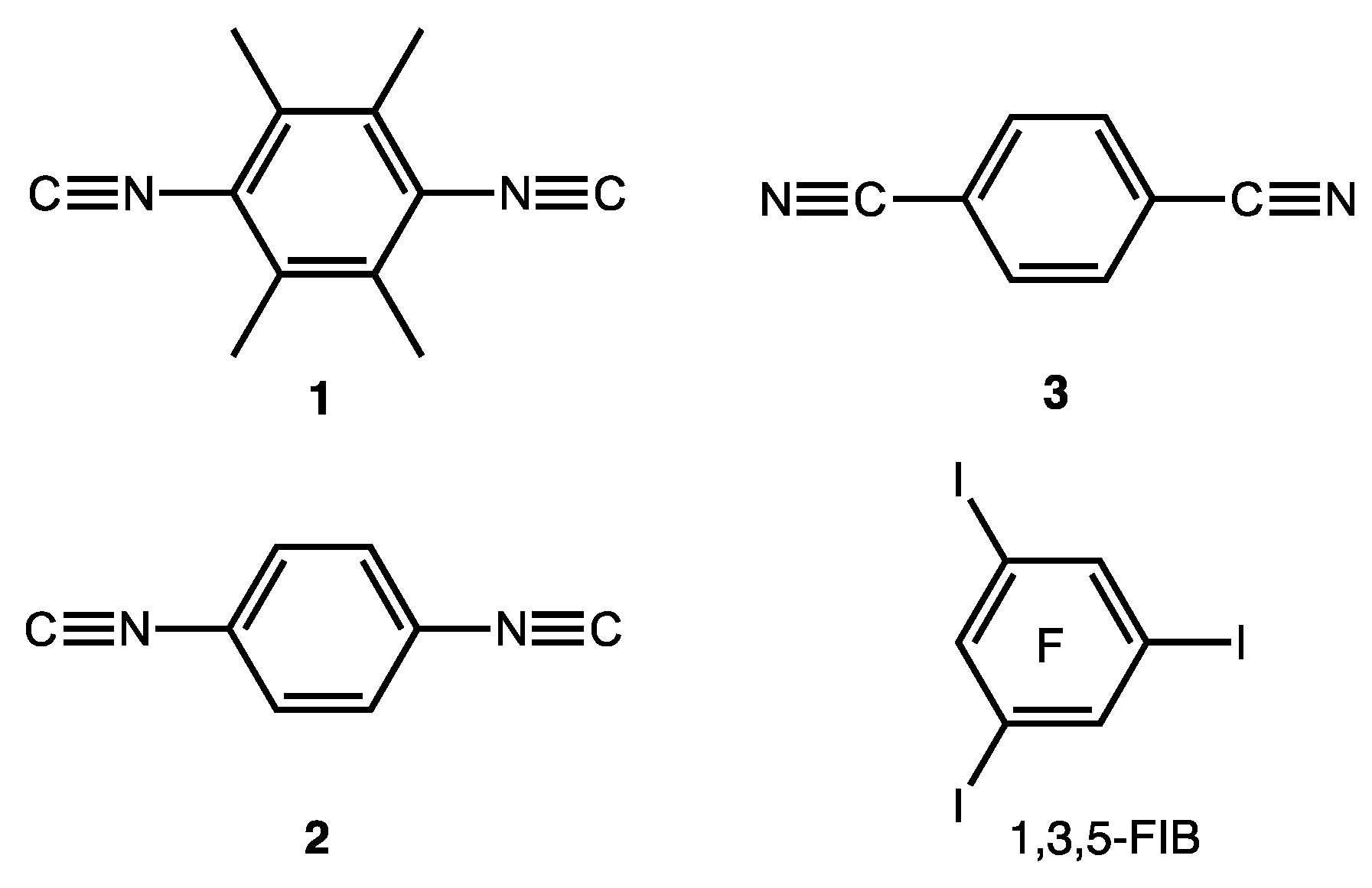

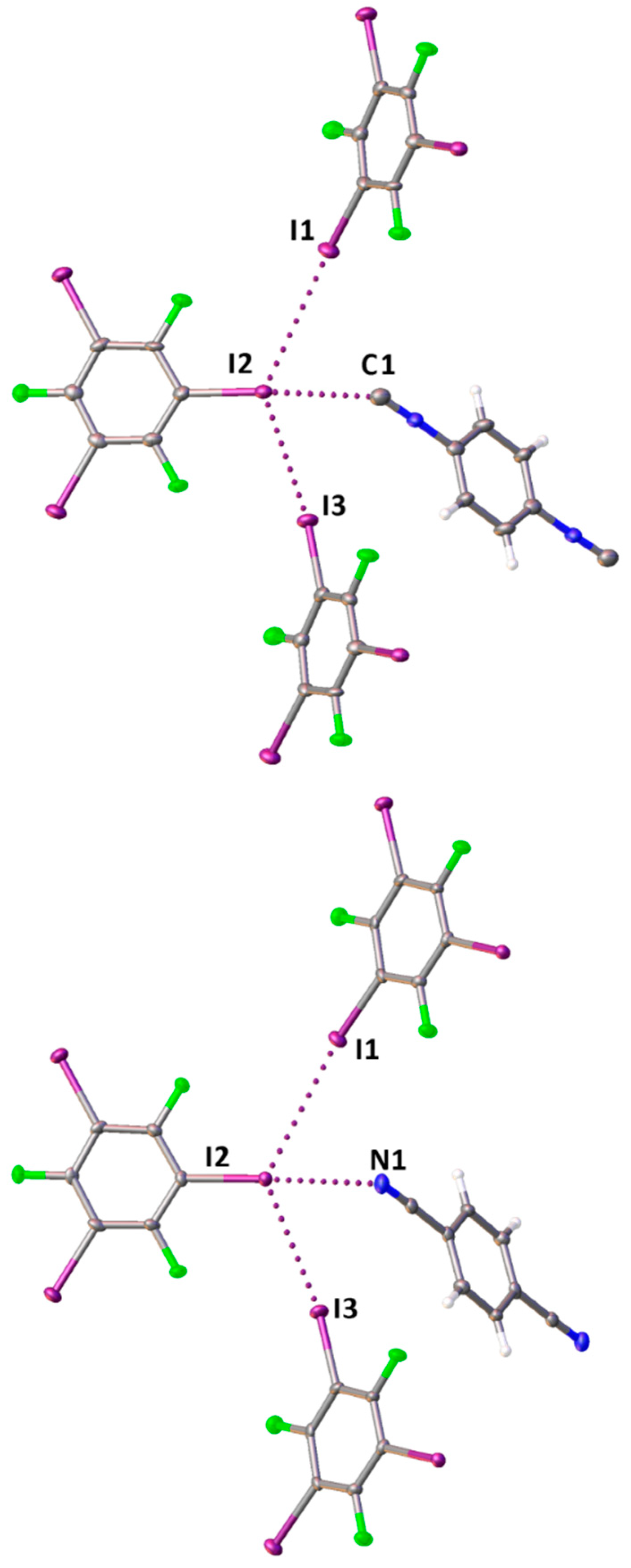

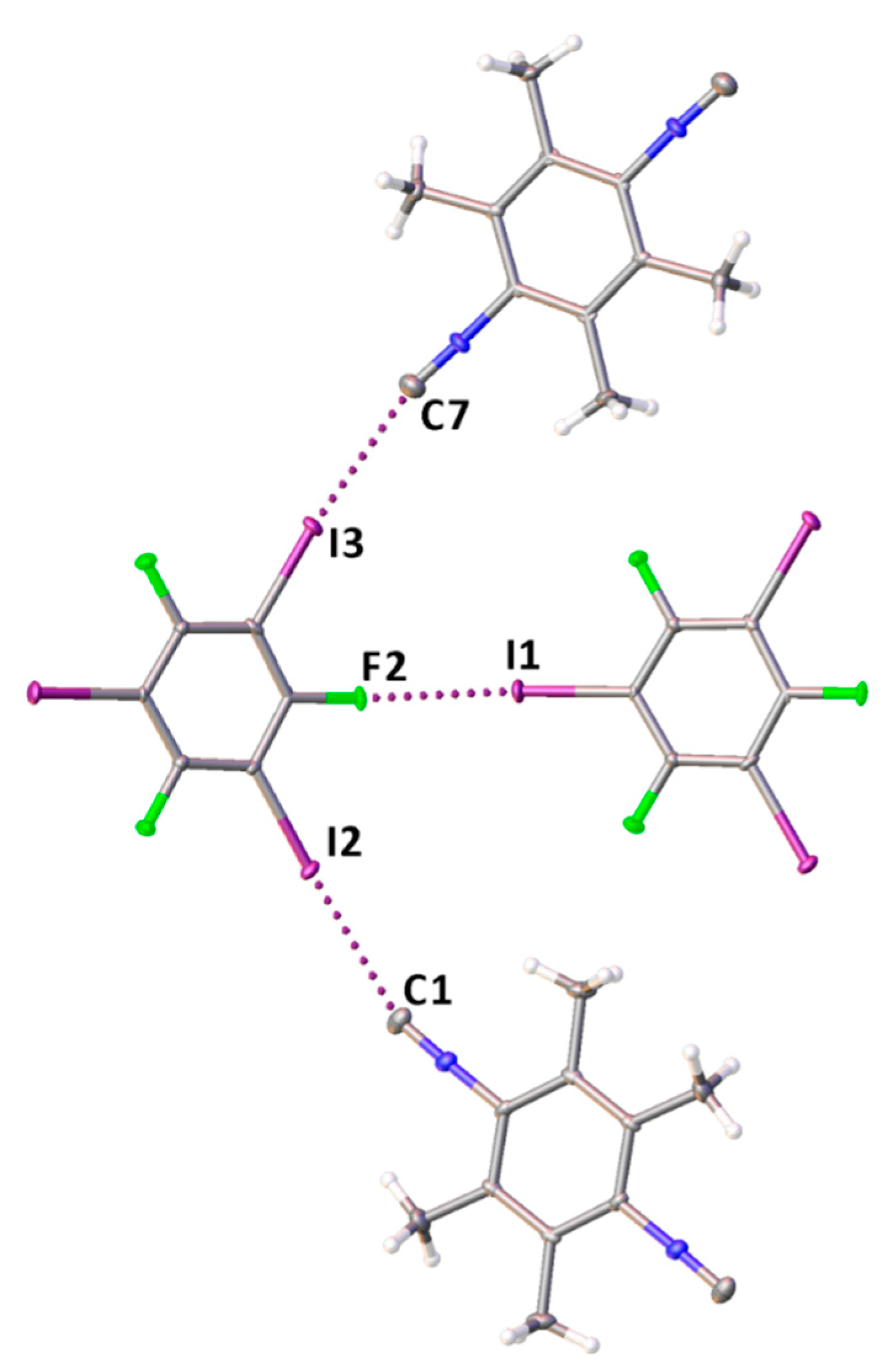

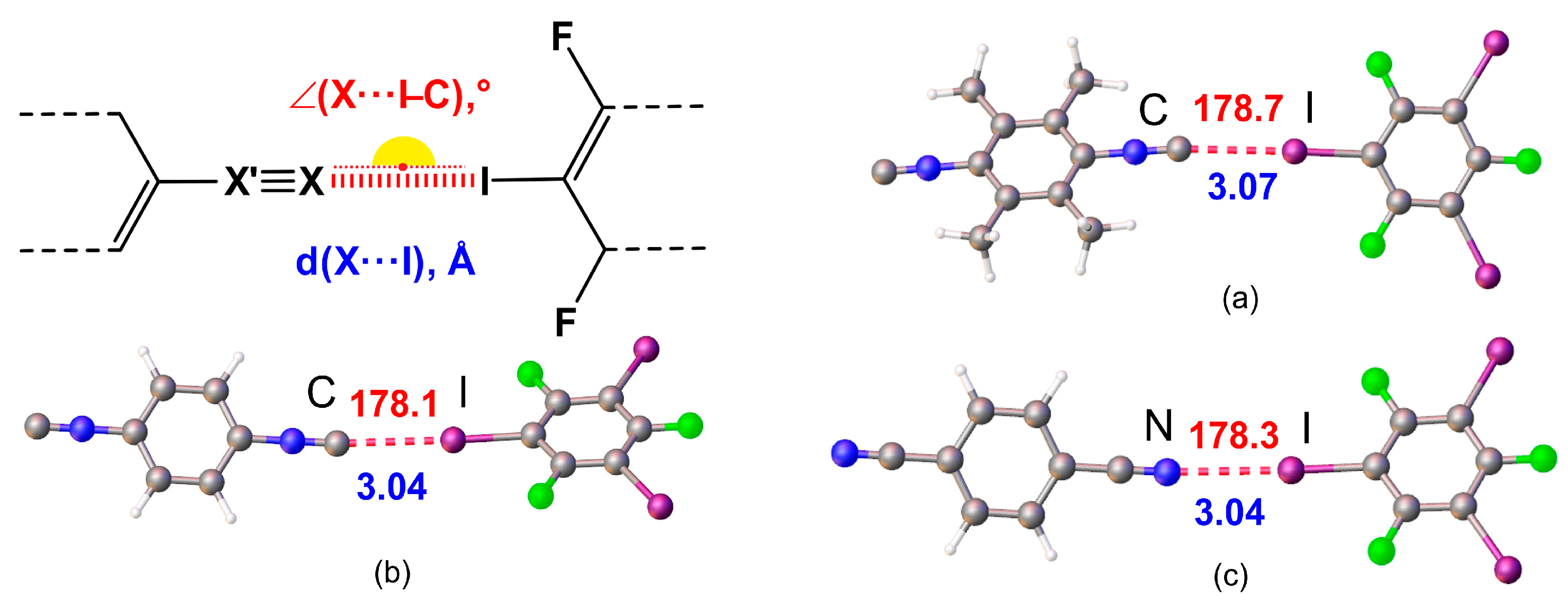

2.1. Crystal growth and structural motifs of the XRD structures

2.2. Theoretical calculations

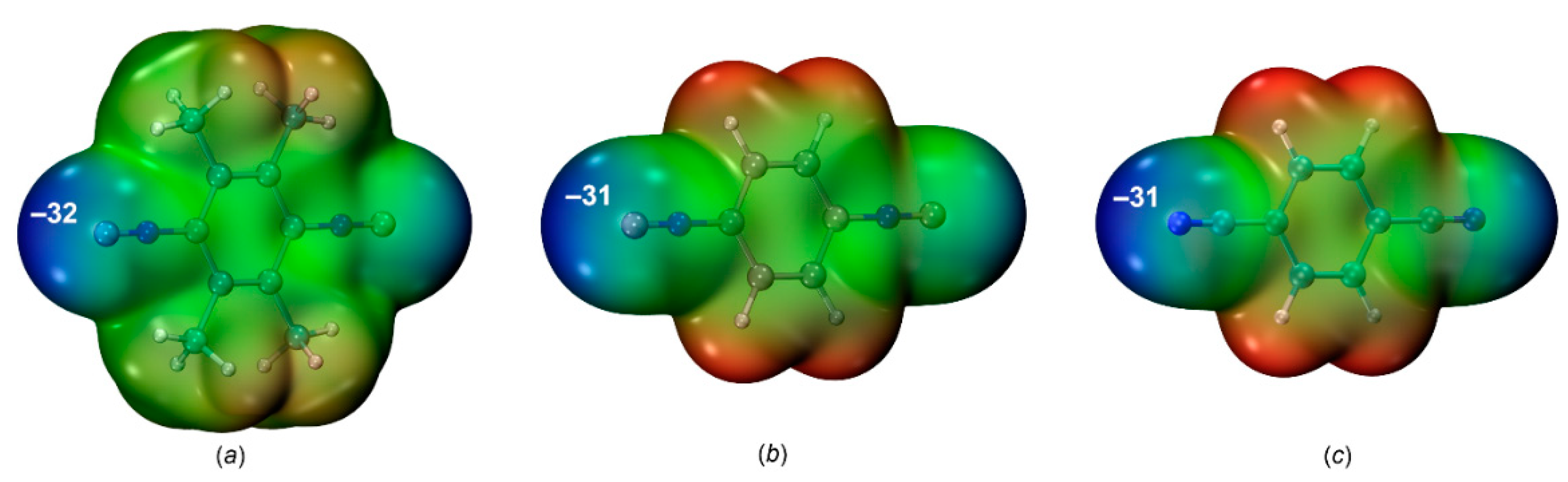

2.2.1. Nucleophilicity and molecular electrostatic potential.

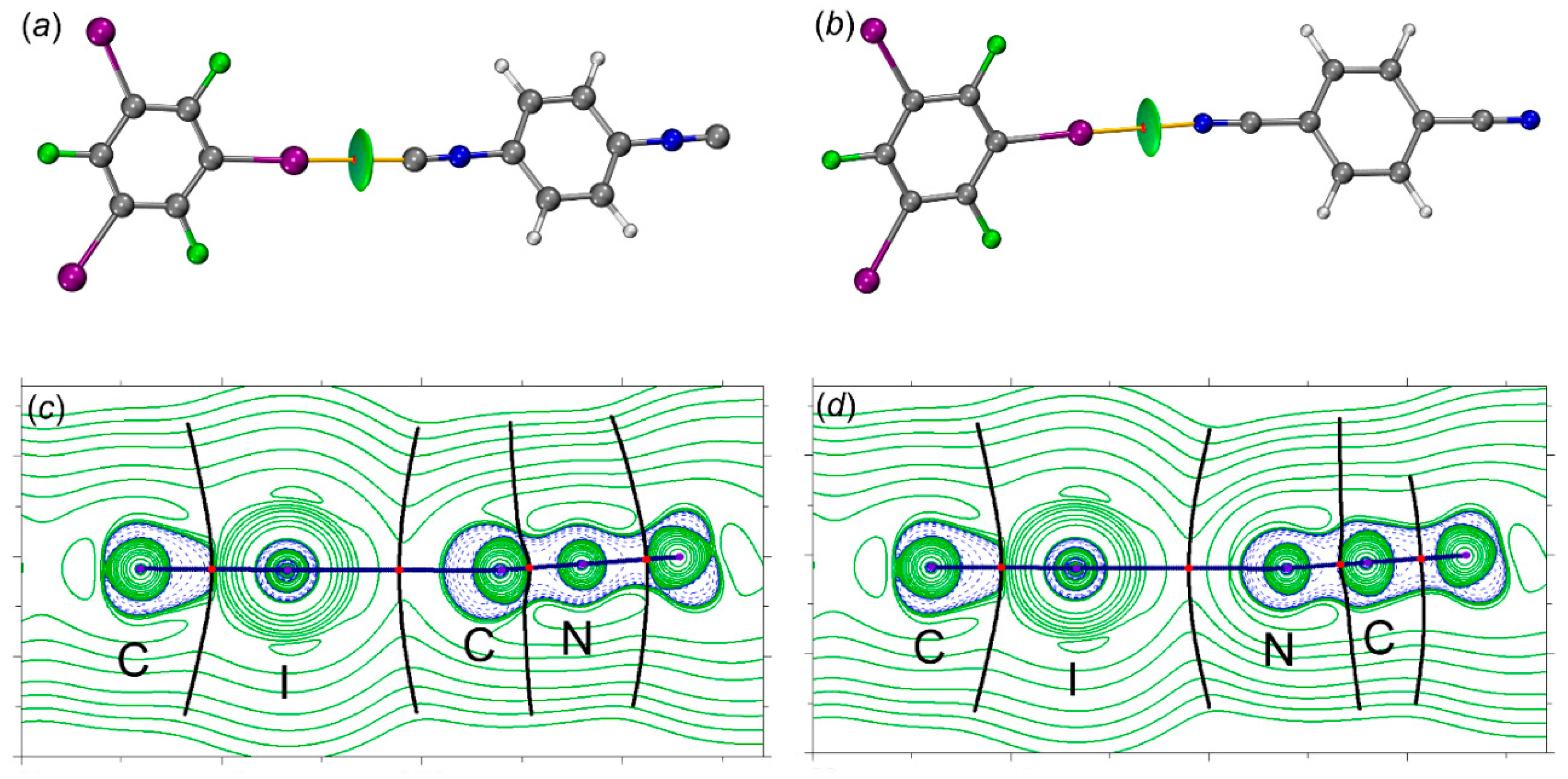

2.2.2. QTAIM-IGMH.

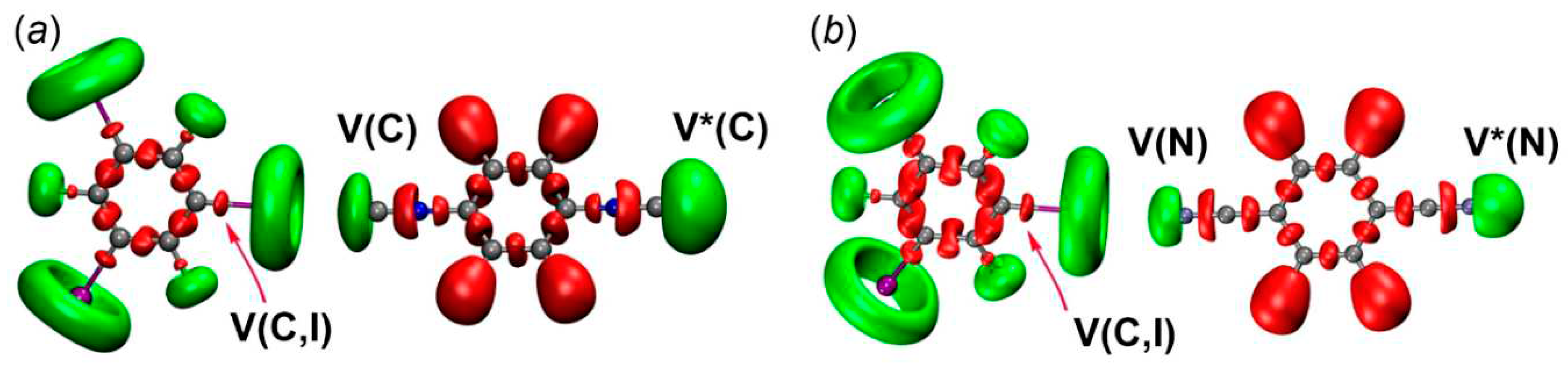

2.2.3. Electron localization function.

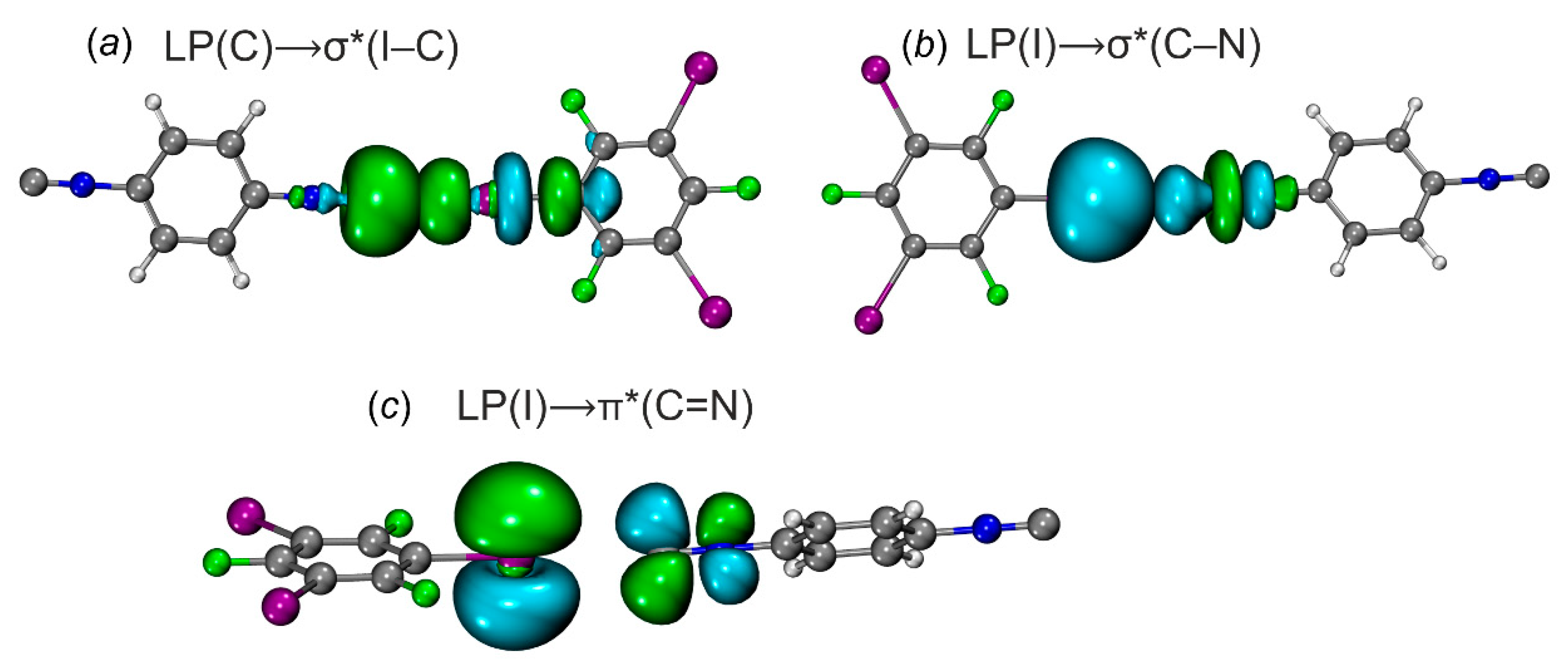

2.2.4. Natural Bond Orbital approach.

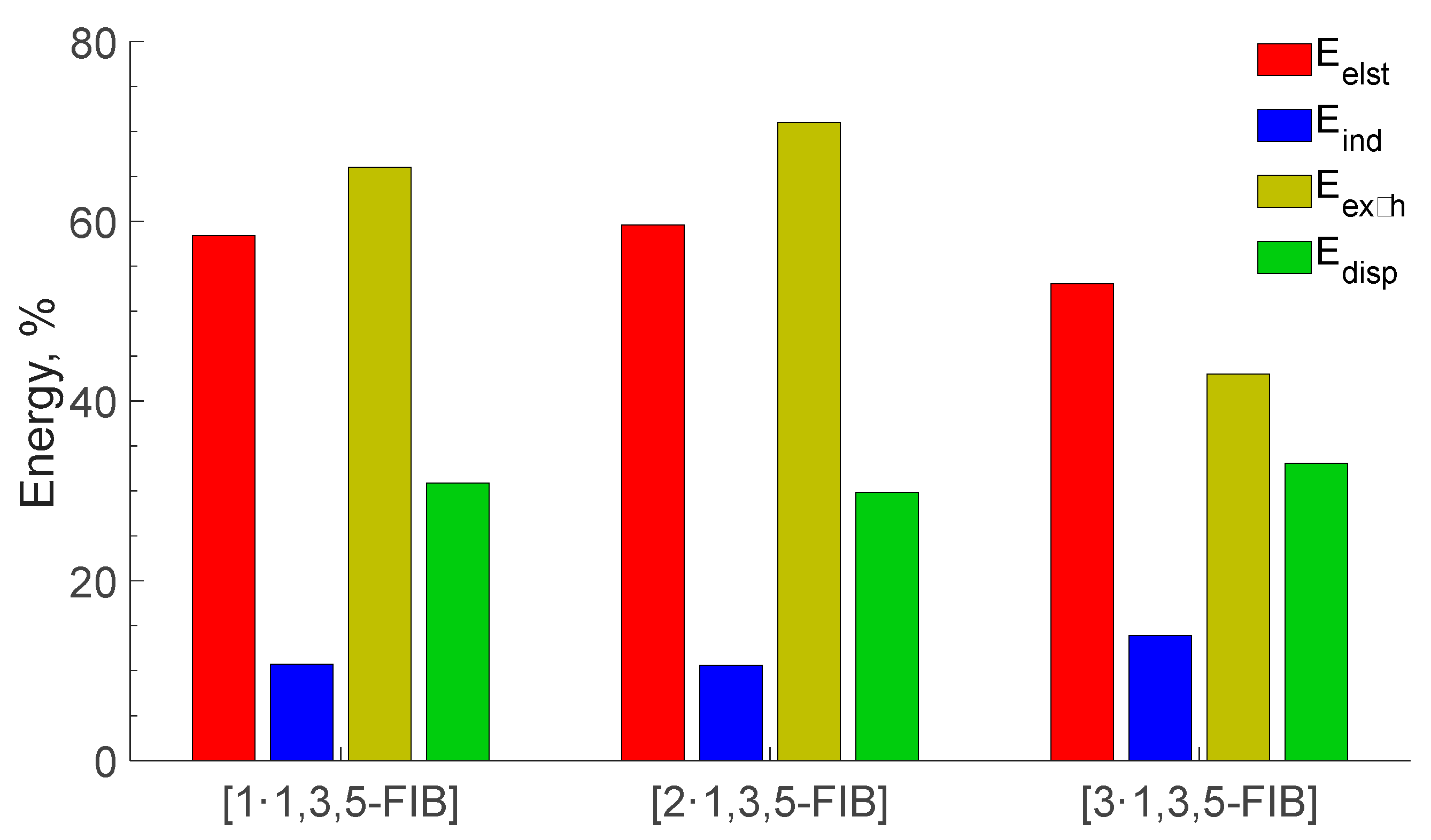

2.2.5. Energy.

3. Discussion

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Materials and Instruments

4.2. Cocrystal growth

4.3. XRD studies

4.4. Computational details

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Cornaton, Y.; Djukic, J.-P. Noncovalent Interactions in Organometallic Chemistry: From Cohesion to Reactivity, a New Chapter. Acc. Chem. Res. 2021, 54, 3828–3840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alkorta, I.; Elguero, J.; Frontera, A. Not Only Hydrogen Bonds: Other Noncovalent Interactions. Crystals 2020, 10, 180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frontera, A.; Bauzá, A. On the Importance of σ–Hole Interactions in Crystal Structures. Crystals 2021, 11, 1205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shukla, R.; Chopra, D. Chalcogen and pnictogen bonds: insights and relevance. Curr. Sci. 2021, 120, 1848–1853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, D.K.; Chernyshov, I.Y.; Torubaev, Y.V.; Rosokha, S.V. From weak to strong interactions: structural and electron topology analysis of the continuum from the supramolecular chalcogen bonding to covalent bonds. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2022, 8251–8259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Resnati, G.; Metrangolo, P. Celebrating 150 years from Mendeleev: The Periodic Table of Chemical Interactions. Coordination Chemistry Reviews 2020, 420, 213409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brammer, L. Halogen bonding, chalcogen bonding, pnictogen bonding, tetrel bonding: origins, current status and discussion. Faraday Discussions 2017, 203, 485–507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brammer, L.; Peuronen, A.; Roseveare, T.M. Halogen bonds, chalcogen bonds, pnictogen bonds, tetrel bonds and other [sigma]-hole interactions: a snapshot of current progress. Acta Crystallographica Section C 2023, 79, 204–216. [Google Scholar]

- Cavallo, G.; Metrangolo, P.; Milani, R.; Pilati, T.; Priimagi, A.; Resnati, G.; Terraneo, G. The Halogen Bond. Chemical Reviews 2016, 116, 2478–2601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, B.; Zang, S.-Q.; Wang, L.-Y.; Mak, T.C.W. Halogen bonding: A powerful, emerging tool for constructing high-dimensional metal-containing supramolecular networks. Coordination Chemistry Reviews 2016, 308, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tepper, R.; Schubert, U.S. Halogen Bonding in Solution: Anion Recognition, Templated Self-Assembly, and Organocatalysis. Angew Chem Int Ed Engl 2018, 57, 6004–6016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Non-covalent Interactions in the Synthesis and Design of New Compounds; Abel M. Maharramov, K.T.M., Maximilian N. Kopylovich, Armando J. L. Pombeiro, Ed.; Wiley: 2016.

- Saha, B.K.; Veluthaparambath, R.V.P.; Krishna G., V. Halogen⋯Halogen Interactions: Nature, Directionality and Applications. Chemistry – An Asian Journal 2023, 18, e202300067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gilday, L.C.; Robinson, S.W.; Barendt, T.A.; Langton, M.J.; Mullaney, B.R.; Beer, P.D. Halogen Bonding in Supramolecular Chemistry. Chem. Rev. 2015, 115, 7118–7195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mukherjee, A.; Tothadi, S.; Desiraju, G.R. Halogen Bonds in Crystal Engineering: Like Hydrogen Bonds yet Different. Accounts of Chemical Research 2014, 47, 2514–2524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xin, D.; Matti, T.; Matti, H. Halogen Bonding in Crystal Engineering. In Recent Advances in Crystallography, Jason, B.B., Ed.; IntechOpen: Rijeka, 2012; p. Ch. 7. [Google Scholar]

- Teyssandier, J.; Mali, K.S.; De Feyter, S. Halogen Bonding in Two-Dimensional Crystal Engineering. ChemistryOpen 2020, 9, 225–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ivanov, D.M.; Bokach, N.A.; Yu. Kukushkin, V.; Frontera, A. Metal Centers as Nucleophiles: Oxymoron of Halogen Bond-Involving Crystal Engineering. Chemistry – A European Journal 2022, 28, e202103173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hein, R.; Beer, P.D. Halogen bonding and chalcogen bonding mediated sensing. Chemical Science 2022, 13, 7098–7125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, J.; Suwardi, A.; Wong, C.J.E.; Loh, X.J.; Li, Z. Halogen bonding regulated functional nanomaterials. Nanoscale Advances 2021, 3, 6342–6357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cavallo, G.; Metrangolo, P.; Milani, R.; Pilati, T.; Priimagi, A.; Resnati, G.; Terraneo, G. The Halogen Bond. Chemical Reviews 2016, 116, 2478–2601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pancholi, J.; Beer, P.D. Halogen bonding motifs for anion recognition. Coordination Chemistry Reviews 2020, 416, 213281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahmudov, K.T.; Kopylovich, M.N.; da Silva, M.F.C.G.; Pombeiro, A.J. Noncovalent Interactions in Catalysis; Royal Society of Chemistry: 2019.

- Mahmudov, K.T.; Gurbanov, A.V.; Guseinov, F.I.; Guedes da Silva, M.F.C. Noncovalent interactions in metal complex catalysis. Coordination Chemistry Reviews 2019, 387, 32–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Breugst, M.; von der Heiden, D.; Schmauck, J. Novel Noncovalent Interactions in Catalysis: A Focus on Halogen, Chalcogen, and Anion-π Bonding. Synthesis 2017, 49, 3224–3236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benz, S.; Poblador-Bahamonde, A.I.; Low-Ders, N.; Matile, S. Catalysis with Pnictogen, Chalcogen, and Halogen Bonds. Angewandte Chemie International Edition 2018, 57, 5408–5412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bulfield, D.; Huber, S.M. Halogen Bonding in Organic Synthesis and Organocatalysis. Chemistry – A European Journal 2016, 22, 14434–14450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mahmudov, K.T.; Kopylovich, M.N.; Guedes da Silva, M.F.C.; Pombeiro, A.J.L. Non-covalent interactions in the synthesis of coordination compounds: Recent advances. Coordination Chemistry Reviews 2017, 345, 54–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berger, G.; Soubhye, J.; Meyer, F. Halogen bonding in polymer science: from crystal engineering to functional supramolecular polymers and materials. Polymer Chemistry 2015, 6, 3559–3580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mendez, L.; Henriquez, G.; Sirimulla, S.; Narayan, M. Looking Back, Looking Forward at Halogen Bonding in Drug Discovery. Molecules 2017, 22, 1397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ho, P.S. Halogen bonding in medicinal chemistry: from observation to prediction. Future Medicinal Chemistry 2017, 9, 637–640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dalpiaz, A.; Pavan, B.; Ferretti, V. Can pharmaceutical co-crystals provide an opportunity to modify the biological properties of drugs? Drug Discov Today 2017, 22, 1134–1138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, Y.; Liu, Y.; Xu, Z.; Li, H.; Liu, H.; Zhu, W. Halogen bonding for rational drug design and new drug discovery. Expert Opin Drug Discov 2012, 7, 375–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bayse, C.A. Halogen bonding from the bonding perspective with considerations for mechanisms of thyroid hormone activation and inhibition. New Journal of Chemistry 2018, 42, 10623–10632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marsan, E.S.; Bayse, C.A. A Halogen Bonding Perspective on Iodothyronine Deiodinase Activity. Molecules 2020, 25, 1328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mikherdov, A.S.; Novikov, A.S.; Boyarskiy, V.P.; Kukushkin, V.Y. The halogen bond with isocyano carbon reduces isocyanide odor. Nature Communications 2020, 11, 2921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mikherdov, A.S.; Popov, R.A.; Smirnov, A.S.; Eliseeva, A.A.; Novikov, A.S.; Boyarskiy, V.P.; Gomila, R.M.; Frontera, A.; Kukushkin, V.Y.; Bokach, N.A. Isocyanide and Cyanide Entities Form Isostructural Halogen Bond-Based Supramolecular Networks Featuring Five-Center Tetrafurcated Halogen···C/N Bonding. Crystal Growth & Design 2022, 22, 6079–6087. [Google Scholar]

- Smirnov, A.S.; Mikherdov, A.S.; Rozhkov, A.V.; Gomila, R.M.; Frontera, A.; Kukushkin, V.Y.; Bokach, N.A. Halogen Bond-Involving Supramolecular Assembly Utilizing Carbon as a Nucleophilic Partner of I⋅⋅⋅C Non-covalent Interaction. Chemistry – An Asian Journal 2023, 18, e202300037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arduengo, A.J.; Kline, M.; Calabrese, J.C.; Davidson, F. SYNTHESIS OF A REVERSE YLIDE FROM A NUCLEOPHILIC CARBENE. Journal of the American Chemical Society 1991, 113, 9704–9705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wasilewska, A.; Gdaniec, M.; Polonski, T. CCDC 618388: Experimental Crystal Structure Determination. 2006. [CrossRef]

- Britton, D.; Gleason, W.B. Dicyanodurene-p-tetrafluorodiiodobenzene (1/1). Acta Crystallographica Section E 2002, 58, o1375–o1377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watari, F. Vibrational frequencies, assignments and normal-coordinate analysis for the methyl isocyanide-borane complex. Inorganic Chemistry 1982, 21, 1442–1446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bell, A.; Walton, R.A.; Edwards, D.A.; Poulter, M.A. Cationic copper(I) isocyanide complexes, [Cu(CNR)4]+ (R = CH3, C(CH3)3 and 2,6-(CH3)2C6H3): Preparations, spectroscopic properties and reactions with neutral ligands. A comparison of the vibrational spectra of [Cu(CNCH3)4]+, [Cu(NCCH3)4]+ and [Cu(NCCD3)4]+. Inorganica Chimica Acta 1985, 104, 171–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tumanov, V.V.; Tishkov, A.A.; Mayr, H. Nucleophilicity Parameters for Alkyl and Aryl Isocyanides. Angewandte Chemie International Edition 2007, 46, 3563–3566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bader, R.F. A quantum theory of molecular structure and its applications. Chemical Reviews 1991, 91, 893–928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, P.S.V.; Raghavendra, V.; Subramanian, V. Bader’s Theory of Atoms in Molecules (AIM) and its Applications to Chemical Bonding. Journal of Chemical Sciences 2016, 128, 1527–1536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lefebvre, C.; Rubez, G.; Khartabil, H.; Boisson, J.-C.; Contreras-García, J.; Hénon, E. Accurately extracting the signature of intermolecular interactions present in the NCI plot of the reduced density gradient versus electron density. Physical Chemistry Chemical Physics 2017, 19, 17928–17936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Varadwaj, P.R.; Varadwaj, A.; Marques, H.M. Halogen Bonding: A Halogen-Centered Noncovalent Interaction Yet to Be Understood. Inorganics 2019, 7, 40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, S.; Asim Khan, M.; Wang, F.; Bano, Z.; Xia, M. Rapid removal of toxic metals Cu2+ and Pb2+ by amino trimethylene phosphonic acid intercalated layered double hydroxide: A combined experimental and DFT study. Chemical Engineering Journal 2020, 392, 123711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, W.; Lin, R.; Zhao, X.; Li, Q.; Huang, Y.; Ye, G. How does a weak interaction change from a reactive complex to a saddle point in a reaction? Computational and Theoretical Chemistry 2020, 1173, 112640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lefebvre, C.; Khartabil, H.; Boisson, J.-C.; Contreras-García, J.; Piquemal, J.-P.; Hénon, E. The Independent Gradient Model: A New Approach for Probing Strong and Weak Interactions in Molecules from Wave Function Calculations. ChemPhysChem 2018, 19, 724–735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klein, J.; Khartabil, H.; Boisson, J.-C.; Contreras-García, J.; Piquemal, J.-P.; Hénon, E. New Way for Probing Bond Strength. The Journal of Physical Chemistry A 2020, 124, 1850–1860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silvi, B.; Gillespie, R.J.; Gatti, C. Electron density analysis. In Comprehensive Inorganic Chemistry II, Reedijk, J., Poeppelmeier, K., Eds.; 2013; Volume 9, pp. 187-226.

- Fuster, F.; Sevin, A.; Silvi, B. Topological Analysis of the Electron Localization Function (ELF) Applied to the Electrophilic Aromatic Substitution. The Journal of Physical Chemistry A 2000, 104, 852–858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silvi, B.; Savin, A. Classification of chemical bonds based on topological analysis of electron localization functions. Nature 1994, 371, 683–686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riplinger, C.; Sandhoefer, B.; Hansen, A.; Neese, F. Natural triple excitations in local coupled cluster calculations with pair natural orbitals. The Journal of Chemical Physics 2013, 139, 134101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Altun, A.; Neese, F.; Bistoni, G. Local energy decomposition analysis of hydrogen-bonded dimers within a domain-based pair natural orbital coupled cluster study. Beilstein Journal of Organic Chemistry 2018, 14, 919–929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hohenstein, E.G.; Parrish, R.M.; Sherrill, C.D.; Turney, J.M.; Schaefer, H.F. , 3rd. Large-scale symmetry-adapted perturbation theory computations via density fitting and Laplace transformation techniques: investigating the fundamental forces of DNA-intercalator interactions. J Chem Phys 2011, 135, 174107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hohenstein, E.G.; Jaeger, H.M.; Carrell, E.J.; Tschumper, G.S.; Sherrill, C.D. Accurate Interaction Energies for Problematic Dispersion-Bound Complexes: Homogeneous Dimers of NCCN, P2, and PCCP. Journal of Chemical Theory and Computation 2011, 7, 2842–2851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hayes, I.; Stone, A. An intermolecular perturbation theory for the region of moderate overlap. Molecular Physics 1984, 53, 83–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeziorski, B.; Moszynski, R.; Szalewicz, K. Perturbation theory approach to intermolecular potential energy surfaces of van der Waals complexes. Chemical Reviews 1994, 94, 1887–1930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patkowski, K. Recent developments in symmetry-adapted perturbation theory. WIREs Computational Molecular Science 2020, 10, e1452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grant Hill, J.; Legon, A.C. On the directionality and non-linearity of halogen and hydrogen bonds. Physical Chemistry Chemical Physics 2015, 17, 858–867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adhikari, U.; Scheiner, S. Sensitivity of pnicogen, chalcogen, halogen and H-bonds to angular distortions. Chemical Physics Letters 2012, 532, 31–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stone, A.J.; Misquitta, A.J. Charge-transfer in Symmetry-Adapted Perturbation Theory. Chemical Physics Letters 2009, 473, 201–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- NETZSCH Proteus Software v.6.1, Netzsch-Gerätebau Bayern, Germany, 2013.

- Sheldrick, G. SHELXT - Integrated space-group and crystal-structure determination. Acta Crystallogr. Sect. A 2015, 71, 3–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dolomanov, O.V.; Bourhis, L.J.; Gildea, R.J.; Howard, J.A.K.; Puschmann, H. OLEX2: a complete structure solution, refinement and analysis program. J. Appl. Crystallogr. 2009, 42, 339–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perdew, J.P.; Burke, K.; Ernzerhof, M. Generalized gradient approximation made simple. Physical review letters 1996, 77, 3865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adamo, C.; Barone, V. Toward reliable density functional methods without adjustable parameters: The PBE0 model. The Journal of chemical physics 1999, 110, 6158–6170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grimme, S.; Ehrlich, S.; Goerigk, L. Effect of the damping function in dispersion corrected density functional theory. Journal of Computational Chemistry 2011, 32, 1456–1465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grimme, S.; Antony, J.; Ehrlich, S.; Krieg, H. A consistent and accurate ab initio parametrization of density functional dispersion correction (DFT-D) for the 94 elements H-Pu. The Journal of Chemical Physics 2010, 132, 154104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neese, F. The ORCA program system. WIREs Computational Molecular Science 2012, 2, 73–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neese, F. Software update: The ORCA program system—Version 5.0. WIREs Computational Molecular Science 2022, 12, e1606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weigend, F.; Ahlrichs, R. Balanced basis sets of split valence, triple zeta valence and quadruple zeta valence quality for H to Rn: Design and assessment of accuracy. Physical Chemistry Chemical Physics 2005, 7, 3297–3305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rolfes, J.D.; Neese, F.; Pantazis, D.A. All-electron scalar relativistic basis sets for the elements Rb–Xe. Journal of Computational Chemistry 2020, 41, 1842–1849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neese, F. An improvement of the resolution of the identity approximation for the formation of the Coulomb matrix. Journal of computational chemistry 2003, 24, 1740–1747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pantazis, D.A.; Neese, F. All-Electron Scalar Relativistic Basis Sets for the Actinides. Journal of Chemical Theory and Computation 2011, 7, 677–684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glendening, E.D.; Badenhoop, J.K.; Reed, A.E.; Carpenter, J.E.; Bohmann, J.A.; Morales, C.M.; Karafiloglou, P.; Landis, C.R.; Weinhold, F. NBO7, Theoretical Chemistry Institute, University of Wisconsin, Madison, 2018.

- Lu, T.; Chen, F. Multiwfn: A multifunctional wavefunction analyzer. Journal of Computational Chemistry 2012, 33, 580–592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lu, T.; Chen, F. Quantitative analysis of molecular surface based on improved Marching Tetrahedra algorithm. Journal of Molecular Graphics and Modelling 2012, 38, 314–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lu, T.; Chen, Q. Independent gradient model based on Hirshfeld partition: A new method for visual study of interactions in chemical systems. Journal of Computational Chemistry 2022, 43, 539–555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Humphrey, W.; Dalke, A.; Schulten, K. VMD: Visual molecular dynamics. Journal of Molecular Graphics 1996, 14, 33–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turney, J.M.; Simmonett, A.C.; Parrish, R.M.; Hohenstein, E.G.; Evangelista, F.A.; Fermann, J.T.; Mintz, B.J.; Burns, L.A.; Wilke, J.J.; Abrams, M.L. Psi4: an open-source ab initio electronic structure program. Wiley Interdisciplinary Reviews: Computational Molecular Science 2012, 2, 556–565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nunzi, F.; Cesario, D.; Belpassi, L.; Tarantelli, F.; Roncaratti, L.F.; Falcinelli, S.; Cappelletti, D.; Pirani, F. Insight into the halogen-bond nature of noble gas-chlorine systems by molecular beam scattering experiments, ab initio calculations and charge displacement analysis. Physical Chemistry Chemical Physics 2019, 21, 7330–7340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belpassi, L.; Infante, I.; Tarantelli, F.; Visscher, L. The Chemical Bond between Au(I) and the Noble Gases. Comparative Study of NgAuF and NgAu+ (Ng = Ar, Kr, Xe) by Density Functional and Coupled Cluster Methods. Journal of the American Chemical Society 2008, 130, 1048–1060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.; Lu, T.; Chen, Q. Intermolecular interaction characteristics of the all-carboatomic ring, cyclo[18]carbon: Focusing on molecular adsorption and stacking. Carbon 2021, 171, 514–523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Domingo, L.R.; Pérez, P. The nucleophilicity N index in organic chemistry. Organic & Biomolecular Chemistry 2011, 9, 7168–7175. [Google Scholar]

- Chattaraj, P.K.; Duley, S.; Domingo, L.R. Understanding local electrophilicity/nucleophilicity activation through a single reactivity difference index. Organic & Biomolecular Chemistry 2012, 10, 2855–2861. [Google Scholar]

| Cocrystal | Contact I···Nu (Nu = C, I, or F) |

Interatomic distance, Å | Nc1 | Angle C–I···Nu, ° |

Angle I···Nu–Y, ° |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1·1,3,5-FIB | I2···C1 | 3.084(5) | 0.84 | 173.22(16) | 153.4(4) |

| I3···C7 | 3.035(5) | 0.82 | 173.38(16) | 159.5(4) | |

| I1···F2 | 2.992(3) | 0.87 | 171.54(13) | 136.9(3) | |

| 2·2(1,3,5-FIB) | I2···C1 | 2.957(6) | 0.80 | 172.0(2) | 138.4(5) |

| I1···I2 | 3.9561(5) | 1.00 | 163.51(14) | 116.60(15) | |

| I3···I2 | 3.8022(4) | 0.96 | 172.52(14) | 110.56(14) | |

| 3·2(1,3,5-FIB) | I2···N1 | 2.935(5) | 0.80 | 173.79(19) | 135.9(5) |

| I1···I2 | 3.9625(6) | 1.00 | 163.79(14) | 116.95(18) | |

| I3···I2 | 3.8122(5) | 0.96 | 171.32(14) | 111.63(17) |

| 1 | 2 | 3 | |

|---|---|---|---|

| NNu, eV | 2.35 | 1.80 | 1.40 |

| NNuloc (C or N), e*eV | 0.33 | 0.30 | 0.23 |

| Contact | Clusters | ρb | ∇2ρb | Vb | Gb | Hb | λ2 | ELF | IBSI | δgpair |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| I···C | [1‧1,3,5-FIB] | 0.0177 | 0.0467 | –0.0101 | 0.0109 | 0.0008 | –0.0115 | 0.09 | 0.032 | 0.027 |

| I···C | [2‧1,3,5-FIB] | 0.0186 | 0.0494 | –0.0109 | 0.0116 | 0.0007 | –0.0123 | 0.09 | 0.034 | 0.028 |

| I···N | [3‧1,3,5-FIB] | 0.0150 | 0.0505 | –0.0094 | 0.0110 | 0.0016 | –0.0103 | 0.05 | 0.025 | 0.024 |

| Clusters | V(C or N), e [VELF, Ǻ3] | V(C,I), e |

|---|---|---|

| [1‧1,3,5-FIB] | 2.62 [100]; 2.63* [380] | 1.75; 1.67*; 1.67* |

| [2‧1,3,5-FIB] | 2.60 [170]; 2.61* [610] | 1.76, 1.68*; 1.68* |

| [3‧1,3,5-FIB] | 3.31 [90]; 3.31* [460] | 1.74, 1.67*; 1.67* |

| Clusters | Transition | E(2) | Δocc |

|---|---|---|---|

| [1‧1,3,5-FIB] | LP(C)⟶σ*(I–C) | 9.6 | 44 |

| LP(I)⟶σ*/π*(C≡N) | 2.1 | 15 | |

| [2‧1,3,5-FIB] | LP(C)⟶σ*(I–C) | 10.2 | 46 |

| LP(I)⟶σ*/π*(C≡N) | 2.3 | 16 | |

| [3‧1,3,5-FIB] | LP(N)⟶σ*(I–C) | 5.2 | 16 |

| LP(I)⟶σ*/π*(N≡C) | 1.8 | 12 |

| Cluster | Eelst | Eind (Ect) | Eexch | Edisp | EintSAPT* | EintSM | EbSM |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| [1‧1,3,5-FIB] | –8.7 | –1.6 (0.5) | 9.8 | –4.6 | –5.1 | –4.2 | –4.1 |

| [2‧1,3,5-FIB] | –9.0 | –1.6 (0.5) | 10.6 | –4.5 | –4.6 | –3.8 | –3.8 |

| [3‧1,3,5-FIB] | –6.1 | –1.6 (0.1) | 6.4 | –3.8 | –5.0 | –3.7 | –3.7 |

| Methods (Descriptors) | HaB I···Ciso vs I···Nnitr | Comments |

|---|---|---|

| Global Nucleophilicity (NNu) | NNiso > NNnitr | Diisocyanides are more nucleophilic than the dinitrile |

| Local Nucleophilicity (NNuloc) | NNuloc(iso) > NNuloc(nitr) | |

| MEP (Vs,min) | Vs,miniso ~ Vs,minnitr | Electrostatic potentials are nearly the same for both systems |

| QTAIM (ρb) | ρbiso > ρbnitr | The electron density values at the BCP of the HaB are slightly higher for the diisocyanide system; this indicates a stronger binding of the diisocyanides to 1,3,5-FIB |

| ELF (V(C,I)) | V(C,I)iso > V(C,I)nitr | Charge transfer effect is higher for the isocyanide systems |

| NBO (Δocc (σ*(I–C)) | Δocc iso > Δocc nitr | |

| DLPNO-CCSD(T) (EbSM) | Ebiso > Ebnitr | Bond energy between the coformers is larger for the diisocyanide structures |

| SAPT (Eexch) | Eexchiso > Eexchnitr | Repulsive Pauli energy for the I···C/N HaBs is higher for the isocyanides. This is in agreement with increased orbital interactions for the diisocyanide systems |

| SAPT (Eelst) | ΔEelstiso ~ ΔEelstnitrl | SAPT results indicate the dominance of Coulomb interactions in the HaB of both systems; they contribute approximately 60% to the sum of negative energy components. The dispersion contribution is no more than 30% |

| SAPT (Edisp) | ΔEdispiso ~ ΔEdispnitrl |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).