Submitted:

24 July 2023

Posted:

26 July 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

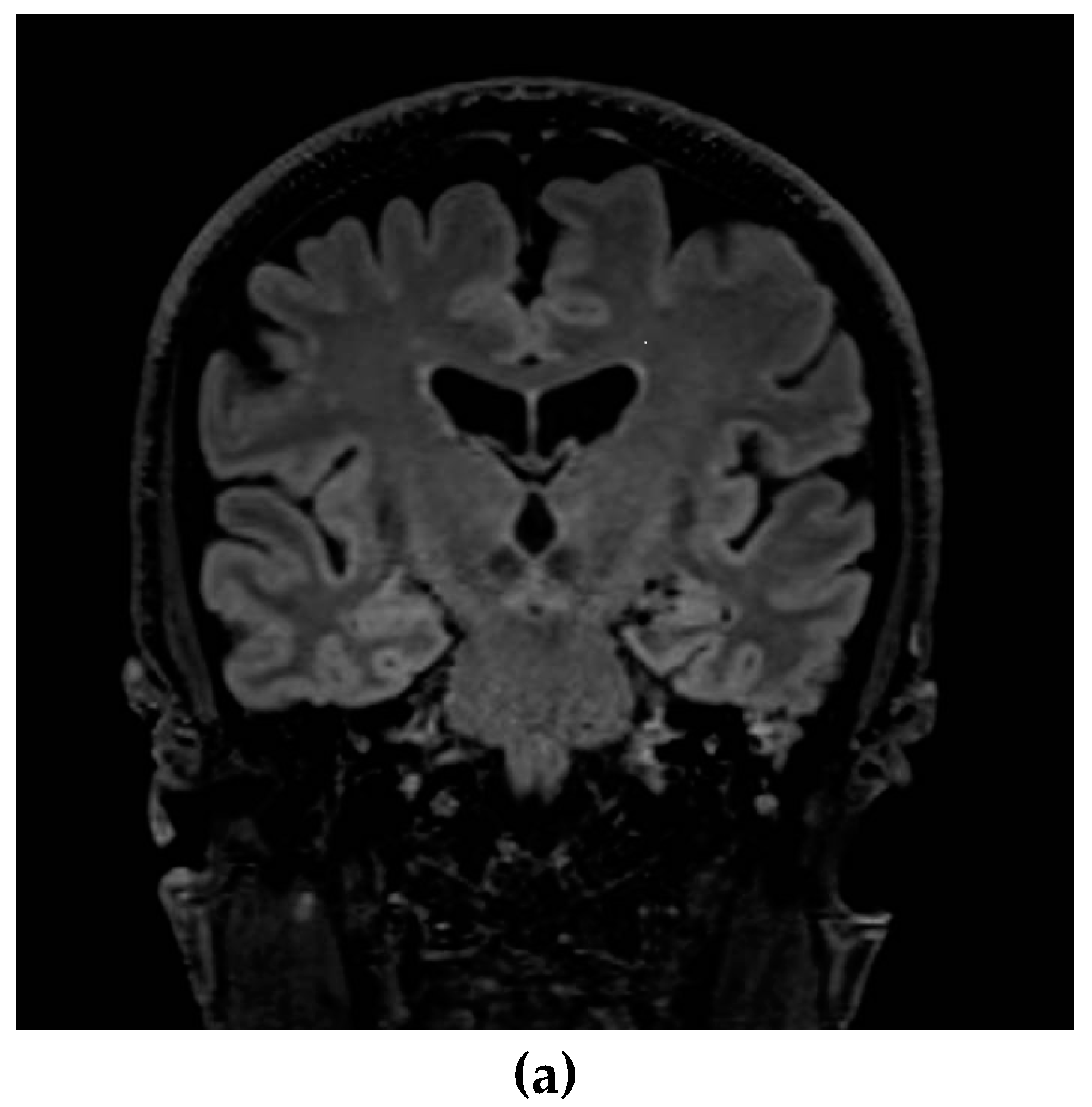

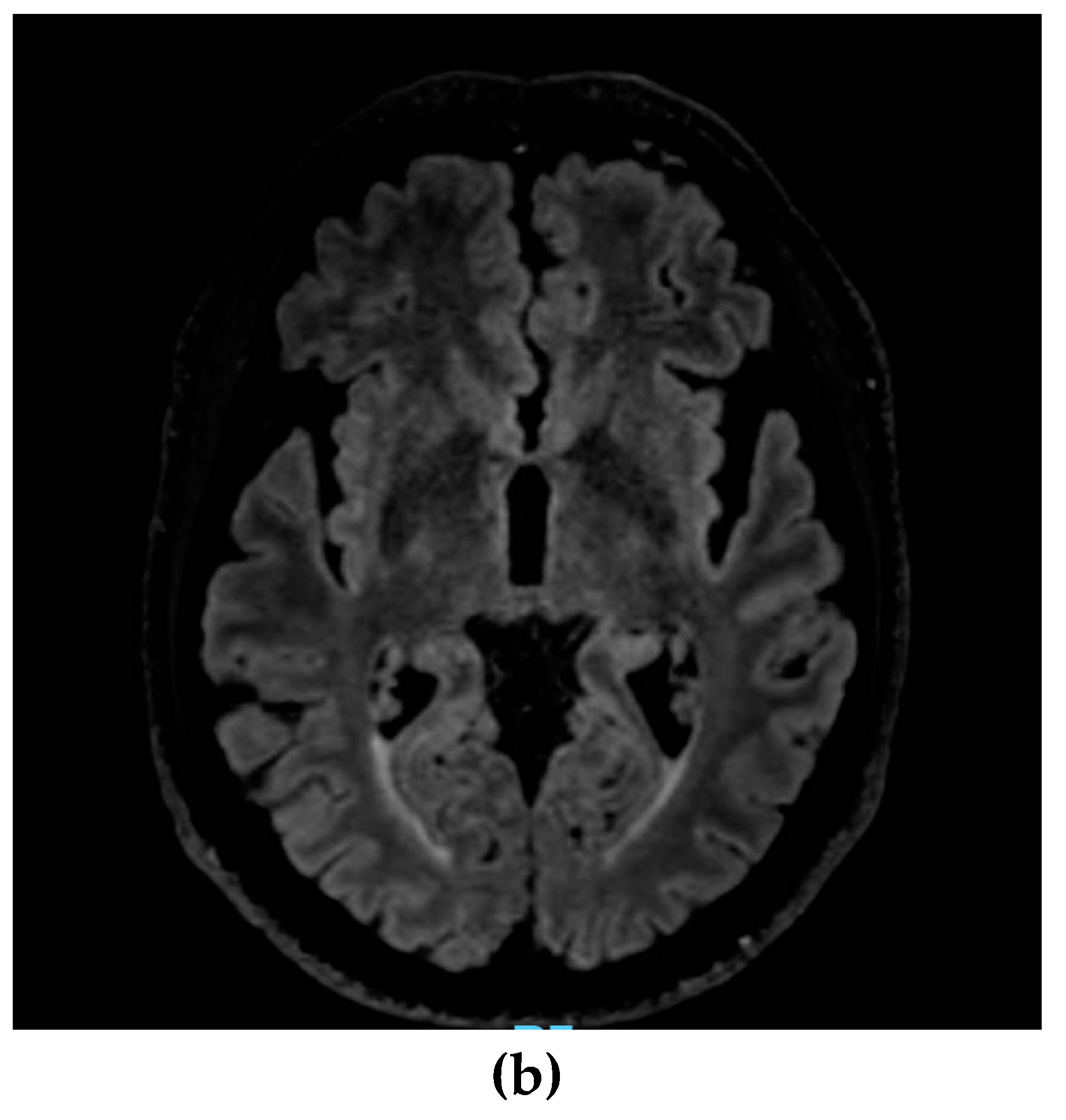

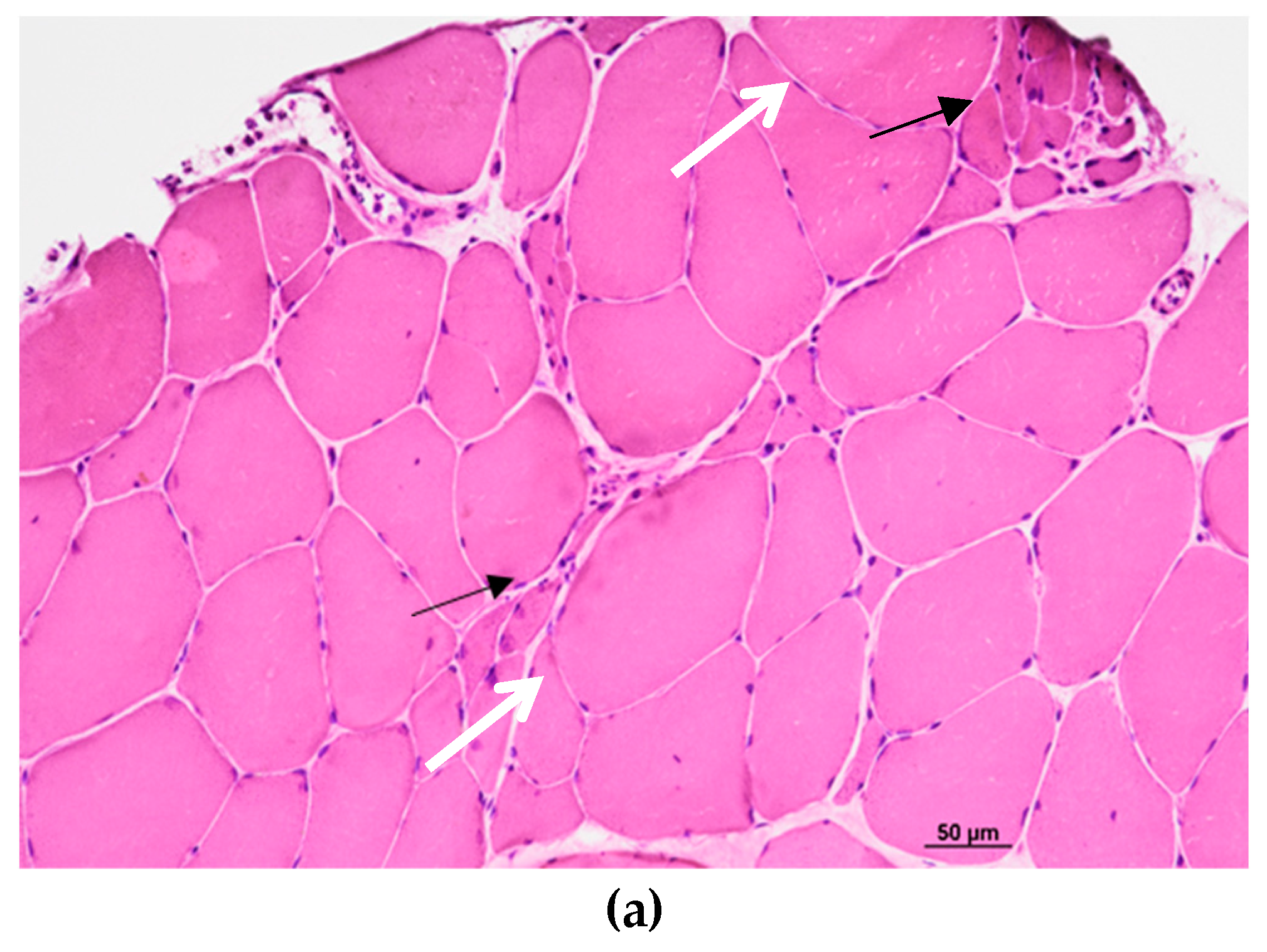

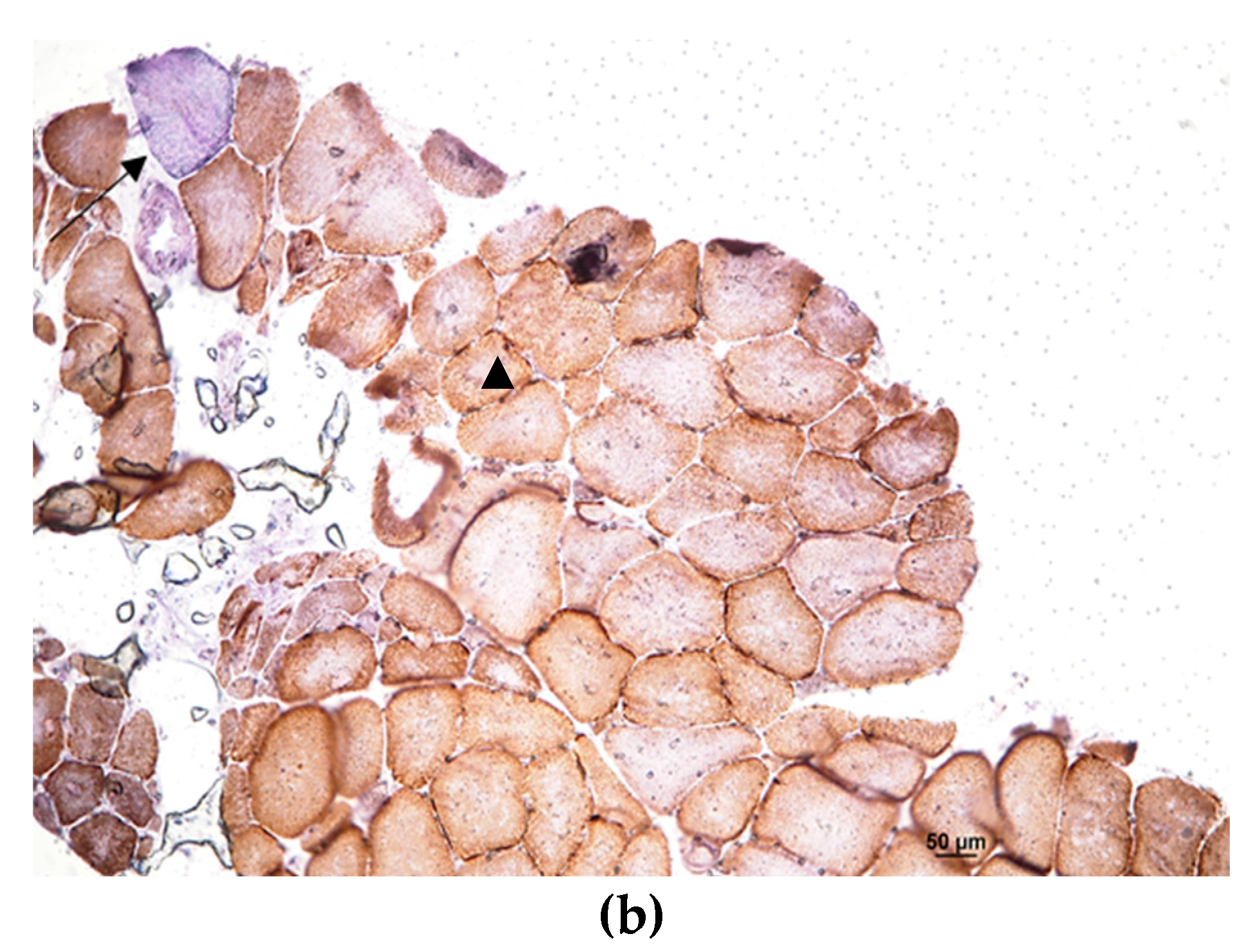

2. Case presentation

3. Discussion

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Goutman, S.A.; Hardiman, O.; Al-Chalabi, A.; Chió, A.; Savelieff, M.G.; Kiernan, M.C.; Feldman, E.L. Emerging insights into the complex genetics and pathophysiology of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Lancet Neurol. 2022, 21, 465–479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryan, M.; Heverin, M.; McLaughlin, R.L.; Hardiman, O. Lifetime Risk and Heritability of Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis. JAMA Neurol. 2019, 76, 1367–1374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Chalabi, A.; Calvo, A.; Chio, A.; Colville, S.; Ellis, C.M.; Hardiman, O.; Heverin, M.; Howard, R.S.; Huisman MHB, Keren, N. ; Leigh, P.N.; Mazzini, L.; Mora, G.; Orrell, R.W.; Rooney, J.; Scott, K.M.; Scotton, W.J.; Seelen, M.; Shaw, C.E.; Sidle, K.S.; Swingler, R.; Tsuda, M.; Veldink, J.H.; Visser, A.E.; van den Berg, L.H.; Pearce, N. Analysis of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis as a multistep process: a population-based modelling study. Lancet Neurol. 2014, 13, 1108–1113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Blitterswijk, M.; van Es, M.A.; Hennekam, E.A.; Dooijes, D.; van Rheenen, W.; Medic, J.; Bourque, P.R.; Schelhaas, H.J.; van der Kooi, A.J.; de Visser, M.; de Bakker, P.I.; Veldink, J.H.; van den Berg, L.H. Evidence for an oligogenic basis of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Hum Mol Genet. 2012, 21, 3776–3784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Rheenen, W.; van der Spek RAA, Bakker MK et al (2021) Common and rare variant association analyses in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis identify 15 risk loci with distinct genetic architectures and neuron-specifc biology. Nat Genet 53, 1636–1648. [CrossRef]

- Amore, G.; Vacchiano, V.; La Morgia, C.; Valentino, M.L.; Caporali, L.; Fiorini, C.; Ormanbekova, D.; Salvi, F.; Bartoletti-Stella, A.; Capellari, S.; Liguori, R.; Carelli, V. Co-occurrence of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis and Leber's hereditary optic neuropathy: is mitochondrial dysfunction a modifier? J Neurol. 2023, 270, 559–564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, M.; Xi, Z.; Ghani, M.; Jia, P.; Pal, M.; Werynska, K.; Moreno, D.; Sato, C.; Liang, Y.; Robertson, J.; Petronis, A.; Zinman, L.; Rogaeva, E. Genetic and epigenetic study of ALS-discordant identical twins with double mutations in SOD1 and ARHGEF28. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2016, 87, 1268–1270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Visani, M.; de Biase, D.; Bartolomei, I.; Plasmati, R.; Morandi, L.; Cenacchi, G.; Salvi, F.; Pession, A. A novel T137A SOD1 mutation in an Italian family with two subjects affected by amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Amyotroph Lateral Scler. 2011, 12, 385–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Origone, P.; Caponnetto, C.; Verdiani, S.; Mantero, V.; Cichero, E.; Fossa, P.; Bellone, E.; Mancardi, G.; Mandich, P. T137A variant is a pathogenetic SOD1 mutation associated with a slowly progressive ALS phenotype. Amyotroph Lateral Scler. 2012, 13, 398–399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pinto, S.; de Carvalho, M. Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis patients and ocular ptosis. Clin Neurol Neurosurg. 2008, 110, 168–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shindo, K.; Satake, A.; Fukao, T.; Ichinose, Y.; Takiyama, Y. Palpebral ptosis as the initial symptom of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Neurol Sci. 2020, 41, 211–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Marchi, F.; Corrado, L.; Bersano, E.; Sarnelli, M.F.; Solara, V.; D'Alfonso, S.; Cantello, R.; Mazzini, L. Ptosis and bulbar onset: an unusual phenotype of familial ALS? Neurol Sci. 2018, 39, 377–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Giordano, C.; Iommarini, L.; Giordano, L.; Maresca, A.; Pisano, A.; Valentino, M.L.; Caporali, L.; Liguori, R.; Deceglie, S.; Roberti, M.; Fanelli, F.; Fracasso, F.; Ross-Cisneros, F.N.; D'Adamo, P.; Hudson, G.; Pyle, A.; Yu-Wai-Man, P.; Chinnery, P.F.; Zeviani, M.; Salomao, S.R.; Berezovsky, A.; Belfort, R., Jr.; Ventura, D.F.; Moraes, M.; Moraes Filho, M.; Barboni, P.; Sadun, F.; De Negri, A.; Sadun, A.A.; Tancredi, A.; Mancini, M.; d'Amati, G.; Loguercio Polosa, P.; Cantatore, P.; Carelli, V. Efficient mitochondrial biogenesis drives incomplete penetrance in Leber's hereditary optic neuropathy. Brain 2014, 137 Pt 2, 335–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hudson, G.; Carelli, V.; Spruijt, L.; Gerards, M.; Mowbray, C.; Achilli, A.; Pyle, A.; Elson, J.; Howell, N.; La Morgia, C.; Valentino, M.L.; Huoponen, K.; Savontaus, M.L.; Nikoskelainen, E.; Sadun, A.A.; Salomao, S.R.; Belfort, R., Jr.; Griffiths, P.; Yu-Wai-Man, P.; de Coo, R.F.; Horvath, R.; Zeviani, M.; Smeets, H.J.; Torroni, A.; Chinnery, P.F. Clinical expression of Leber hereditary optic neuropathy is affected by the mitochondrial DNA-haplogroup background. Am J Hum Genet. 2007, 81, 228–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bolze, A., Mendez, F., White, S., Tanudjaja, F., Isaksson, M., Rashkin, M., Bowes, J. er al. Selective constraints and pathogenicity of mitochondrial DNA variants inferred from a novel database of 196, 554 unrelated individuals. bioRxiv. 2019; (Preprint at) https://doi.org/10.1101/798264. [CrossRef]

- Watson, E.C.; Davis, R.L.; Ravishankar, S.; Copty, J.; Kummerfeld, S.; Sue, C.M. Low disease risk and penetrance in Leber hereditary optic neuropathy. Am J Hum Genet. 2023, 110, 166–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mackey, D.A.; Ong, J.S.; MacGregor, S.; Whiteman, D.C.; Craig, J.E.; Lopez Sanchez MIG, Kearns, L. S.; Staffieri, S.E.; Clarke, L.; McGuinness, M.B.; Meteoukki, W.; Samuel, S.; Ruddle, J.B.; Chen, C.; Fraser, C.L.; Harrison, J.; Howell, N.; Hewitt, A.W. Is the disease risk and penetrance in Leber hereditary optic neuropathy actually low? Am J Hum Genet. 2023, 110, 170–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nguyen, H.P.; Van Broeckhoven, C.; van der Zee, J. ALS Genes in the Genomic Era and their Implications for FTD. Trends Genet. 2018, 34, 404–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, H.; Yu, W.; Luo, S.S.; Yang, Y.J.; Liu, F.T.; Zhang, Y.; Chen, Y.; Sun, Y.M.; Wu, J.J. Association of the TBK1 mutation p.Ile334Thr with frontotemporal dementia and literature review. Mol Genet Genomic Med. 2019, 7, e547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freischmidt, A.; Wieland, T.; Richter, B.; Ruf, W.; Schaeffer, V.; Müller, K.; Marroquin, N.; Nordin, F.; Hübers, A.; Weydt, P.; Pinto, S.; Press, R.; Millecamps, S.; Molko, N.; Bernard, E.; Desnuelle, C.; Soriani, M.H.; Dorst, J.; Graf, E.; Nordström, U.; Feiler, M.S.; Putz, S.; Boeckers, T.M.; Meyer, T.; Winkler, A.S.; Winkelman, J.; de Carvalho, M.; Thal, D.R.; Otto, M.; Brännström, T.; Volk, A.E.; Kursula, P.; Danzer, K.M.; Lichtner, P.; Dikic, I.; Meitinger, T.; Ludolph, A.C.; Strom, T.M.; Andersen, P.M.; Weishaupt, J.H. Haploinsufficiency of TBK1 causes familial ALS and fronto-temporal dementia. Nat Neurosci. 2015, 18, 631–636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hirano, M.; Angelini, C.; Montagna, P.; Hays, A.P.; Tanji, K.; Mitsumoto, H.; Gordon, P.H.; Naini, A.B.; DiMauro, S.; Rowland, L.P. Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis with ragged-red fibers. Arch Neurol. 2008, 65, 403–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vijayvergiya, C.; Beal, M.F.; Buck, J.; Manfredi, G. Mutant superoxide dismutase 1 forms aggregates in the brain mitochondrial matrix of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis mice. J Neurosci. 2005, 25, 2463–2470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pasinelli, P.; Belford, M.E.; Lennon, N.; Bacskai, B.J.; Hyman, B.T.; Trotti, D.; Brown RH, Jr. Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis-associated SOD1 mutant proteins bind and aggregate with Bcl-2 in spinal cord mitochondria. Neuron 2004, 43, 19–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bille, A.; Jónsson, S.Æ.; Akke, M.; Irbäck, A. Local unfolding and aggregation mechanisms of SOD1: a Monte Carlo exploration. J Phys Chem B. 2013, 117, 9194–9202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vande Velde, C.; McDonald, K.K.; Boukhedimi, Y.; McAlonis-Downes, M.; Lobsiger, C.S.; Bel Hadj, S.; Zandona, A.; Julien, J.P.; Shah, S.B.; Cleveland, D.W. Misfolded SOD1 associated with motor neuron mitochondria alters mitochondrial shape and distribution prior to clinical onset. PLoS One 2011, 6, e22031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sasaki, S.; Iwata, M. Mitochondrial alterations in the spinal cord of patients with sporadic amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol. 2007, 66, 10–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Vos, K.J.; Chapman, A.L.; Tennant, M.E.; Manser, C.; Tudor, E.L.; Lau, K.F.; Brownlees, J.; Ackerley, S.; Shaw, P.J.; McLoughlin, D.M.; Shaw, C.E.; Leigh, P.N.; Miller CCJ, Grierson, A. J. Familial amyotrophic lateral sclerosis-linked SOD1 mutants perturb fast axonal transport to reduce axonal mitochondria content. Hum Mol Genet. 2007, 16, 2720–2728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, L.; Chen, L.; Li, L. The TBK1-OPTN Axis Mediates Crosstalk Between Mitophagy and the Innate Immune Response: A Potential Therapeutic Target for Neurodegenerative Diseases. Neurosci Bull. 2017, 33, 354–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richter, B.; Sliter, D.A.; Herhaus, L.; Stolz, A.; Wang, C.; Beli, P.; Zaffagnini, G.; Wild, P.; Martens, S.; Wagner, S.A.; Youle, R.J.; Dikic, I. Phosphorylation of OPTN by TBK1 enhances its binding to Ub chains and promotes selective autophagy of damaged mitochondria. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2016, 113, 4039–4044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harding, O.; Evans, C.S.; Ye, J.; Cheung, J.; Maniatis, T.; Holzbaur ELF. ALS- and FTD-associated missense mutations in TBK1 differentially disrupt mitophagy. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2021, 118, e2025053118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carelli, V.; Ghelli, A.; Bucchi, L.; Montagna, P.; De Negri, A.; Leuzzi, V.; Carducci, C.; Lenaz, G.; Lugaresi, E.; Degli Esposti, M. Biochemical features of mtDNA 14484 (ND6/M64V) point mutation associated with Leber's hereditary optic neuropathy. Ann Neurol. 1999, 45, 320–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baracca, A.; Solaini, G.; Sgarbi, G.; Lenaz, G.; Baruzzi, A.; Schapira, A.H.; Martinuzzi, A.; Carelli, V. Severe impairment of complex I-driven adenosine triphosphate synthesis in leber hereditary optic neuropathy cybrids. Arch Neurol. 2005, 62, 730–736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).