Submitted:

21 July 2023

Posted:

24 July 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results

| Crop | Cultivar | Number of samples |

|---|---|---|

| Winter Wheat | Aksiniya Gubernator Dona Asket Anka Karavan Korona |

3 6 7 1 1 1 |

| Winter Barley | Onega Vosxod Rubezh Espada Master Toma |

5 3 2 1 1 1 |

| Oats | Verny‘j Skakun Podgorny‘j - |

1 1 1 1 |

| Cereal mix (Triticale; wheat and barley) | - | 1 |

| Cereal-legume mix | - | 1 |

3.1. Bacteria identification

| Crop | Cultivar | Isolate № | Primers | Result of identification |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Winter wheat | Aksiniya | 10 | 27f-907r | Frigoribacterium sp. |

| 11 | 8UA-519B | Pantoea sp. | ||

| 12 | 8UA-519B | Pantoea sp. | ||

| Winter wheat | Aksiniya | 14 | 27f-907r | Ochrobactrum sp. |

| 15 | 27f-907r | Frigoribacterium sp. | ||

| Winter wheat | Aksiniya | 17 | 27f-907r | Pantoea agglomerans |

| Winter wheat | Gubernator Dona | 25 | 27f-907r | Arthrobacter sp. |

| 26 | 8UA-519B | Pantoea sp. | ||

| 27 | 27f-907r | Erwinia sp. | ||

| Winter wheat | Gubernator Dona | 28 | 27f-907r | Clavibacter michiganensis |

| 29 | 8UA-519B | Pantoea agglomerans | ||

| 30 | 27f-907r | Erwinia aphidicola | ||

| Winter wheat | Asket | 36 | 27f-907r | Pantoea sp. |

| 37 | 27f-907r | Erwinia sp. | ||

| 38 | 8UA-519B | Ochrobactrum sp. | ||

| 39 | 8UA-519B | Pantoea agglomerans | ||

| Winter wheat | Gubernator Dona | 43 | 27f-907r | Rosenbergiella sp. |

| 45 | 27f-907r | Pantoea ananatis | ||

| Winter wheat | Gubernator Dona | 46 | 27f-907r | Erwinia sp. |

| 47 | 27f-907r | Erwinia sp. | ||

| 48 | 27f-907r | Rosenbergiella sp. | ||

| 49 | 8UA-519B | Pantoea agglomerans | ||

| 50 | 27f-907r | Stenotrophomonas sp. | ||

| 51 | 27f-907r | Erwinia sp. | ||

| Winter wheat | Gubernator Dona | 52 | 27f-907r | Rosenbergiella sp. |

| 53 | 27f-907r | Erwinia sp. | ||

| Winter wheat | Gubernator Dona | 55 | 8UA-519B | Rosenbergiella sp. |

| 57 | 27f-907r | Erwinia sp. | ||

| 58 | 8UA-519B | Pantoea sp. | ||

| 59 | 27f-907r | Pantoea sp. | ||

| 60 | 8UA-519B | Pantoea sp. | ||

| Winter wheat | Asket | 61 | 8UA-519B | Uncultured bacterium |

| 62 | 27f-907r | Erwinia sp. | ||

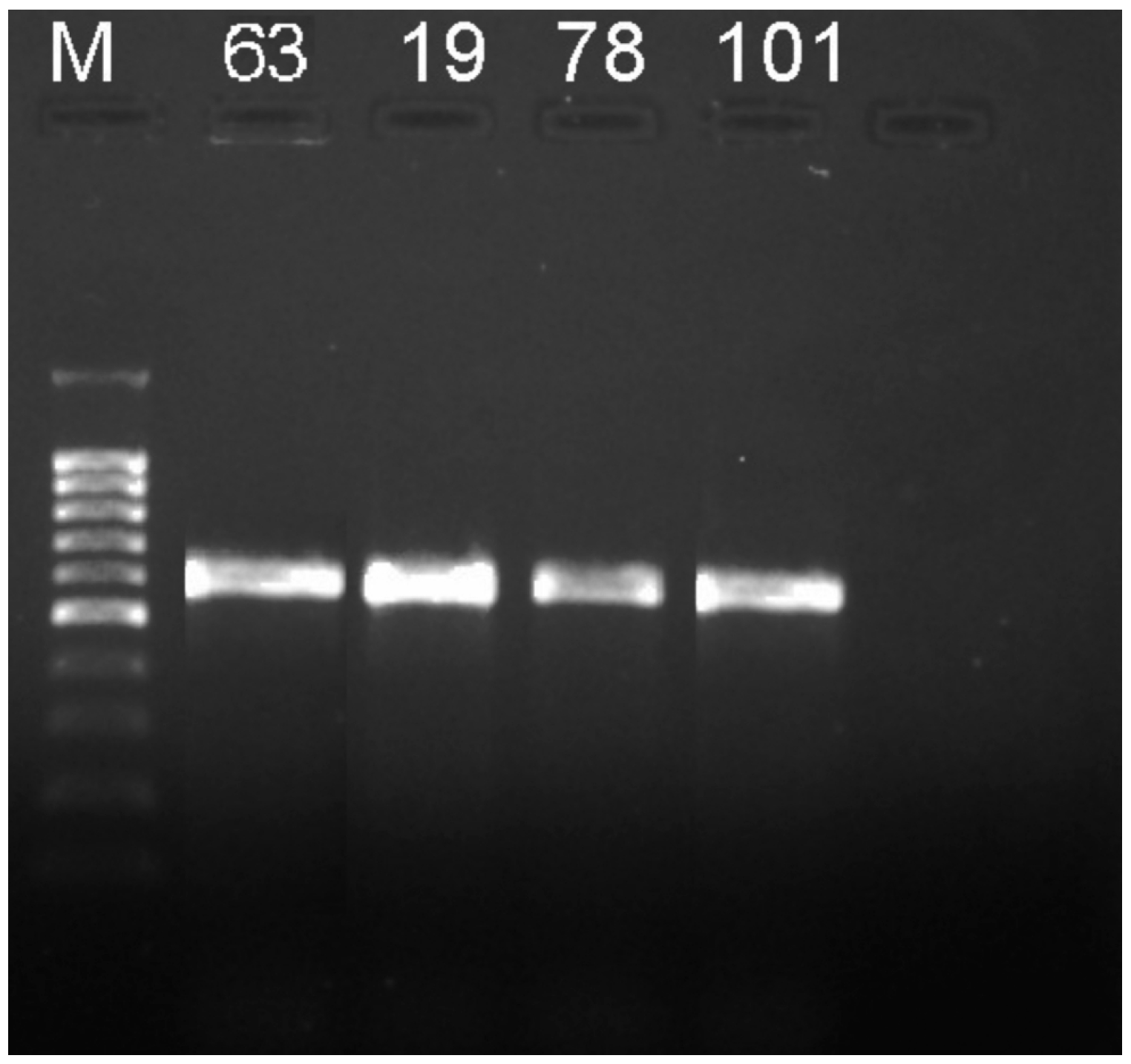

| 63 | PSf- PSr | Pseudomonas sp. | ||

| 64 | 27f-907r | Exiguobacterium sp. | ||

| Winter wheat | Asket | 75-2 | 27f-907r | Pantoea sp. |

| Winter wheat | Asket | 76 | 27f-907r | Pantoea sp. |

| Winter wheat | Asket | 77 | 8UA-519B | Pantoea sp. |

| 78 | PSf- PSr | Pseudomonas sp. | ||

| Winter wheat | Asket | 79 | 27f-907r | Pantoea agglomerans |

| Winter wheat | Asket | 81 | 27f-907r | Plantibacter sp. |

| 82 | 27f-907r | Bacteria | ||

| Winter wheat | Anka | 87 | 27f-907 | Rosenbergiella sp. |

| Winter wheat | Karavan | 88 | 27f-907 | Rosenbergiella sp. |

| Winter wheat | Korona | 102 | 27f-907 | Pantoea agglomerans |

| Crop | Cultivar | Isolate № | Primers | Result of identification |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Winter barley | Onega | 1 | 8UA-519B | Ochrobactrum sp. |

| 2 | 27f-907r | Erwinia aphidicola | ||

| 3 | 27f-907r | Rathayibacter festucae | ||

| 4 | 27f-907r | Arthrobacter sp. | ||

| 5 | 27f-907r | Arthrobacter sp. | ||

| 7 | 27f-907r | Stenotrophomonas maltophilia | ||

| 8 | 27f-907r | Erwinia sp. | ||

| 9 | 27f-907r | Bacteria | ||

| Winter barley | Vosxod | 18 | 27f-907r | Frigoribacterium sp. |

| 19 | PSf- PSr | Pseudomonas poae | ||

| 20 | 8UA-519B | Plantibacter flavus | ||

| 21 | 8UA-519B | Frigoribacterium sp. | ||

| 22 | 8UA-519B | Erwinia rhapontici | ||

| 24 | 8UA-519B | Erwinia rhapontici | ||

| Winter barley | Vosxod | 31 | 8UA-519B | Erwinia sp. |

| Winter barley | Vosxod | 32 | 27f-907r | Pantoea sp. |

| 33 | 27f-907r | Erwinia sp. | ||

| 34 | 27f-907r | Curtobacterium sp. | ||

| 35 | 27f-907r | Ochrobactrum sp. | ||

| Winter barley | Onega | 41 | 8UA-519B | Enterobacter sp. |

| 42 | 27f-907r | Uncultured bacterium | ||

| Winter barley | Onega | 66 | 27f-907r | Exiguobacterium sp. |

| 67 | 27f-907r | Stenotrophomonas sp. | ||

| 68 | 27f-907r | Stenotrophomonas sp. | ||

| Winter barley | Onega | 69 | 8UA-519B | Pseudomonas sp. |

| 70 | 27f-907r | Plantibacter sp. | ||

| 71 | 27f-907r | Stenotrophomonas sp. | ||

| 72 | 27f-907r | Stenotrophomonas sp. | ||

| 73 | 27f-907r | Agrococcus jenensis | ||

| Winter barley | Onega | 74-1 | 8UA-519B | Pantoea vagans |

| 74-2 | 27f-907r | Frigoribacterium sp. | ||

| 75-1 | 27f-907r | Rosenbergiella sp. | ||

| Winter barley | Rubezh | 83 | 27f-907r | Pantoea pleuroti |

| 84 | 27f-907 | Pantoea sp. | ||

| 85 | 8UA-519B | Microbacterium sp. | ||

| Winter barley | Espada | 86 | 27f-907 | Uncultured bacterium |

| Winter barley | Master | 95 | 27f-907 | Curtobacterium sp. |

| 96 | 27f-907 | Clavibacter michiganensis | ||

| Winter barley | Rubezh | 97 | 27f-907 | Microbacterium sp. |

| Winter barley | Toma | 98 | 8UA-519B | Enterococcus mundtii |

| 98-2 | 27f-907 | Frigoribacterium sp. |

| Crop | Cultivar | Isolate № | Primers | Result of identification |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Oats | Verny‘j | 89 | 27f-907 | Pantoea sp. |

| 90 | 27f-907 | Curtobacterium sp. | ||

| Oats | Skakun | 91 | 27f-907 | Rosenbergiella sp |

| 92 | 27f-907 | Pseudomonas sp. | ||

| Oats | Podgorny‘j | 93 | 27f-907 | Pantoea agglomerans |

| 94 | 27f-907 | Pantoea sp. | ||

| Oats | – | 101 | PSf- PSr | Pseudomonas sp. |

| Triticale, wheat, barley | – | 99 | 27f-907 | Arthrobacter sp. |

| Cereal-legume mix | – | 100 | 27f-907 | Frigoribacterium sp. |

| Genus | Frequency % | Species | Frequency % |

|---|---|---|---|

| Pantoea | 28.95 |

Pantoea agglomerans Pantoea ananatis Pantoea vagans Pantoea pleuroti |

18.42 2.63 2.63 2.63 |

| Erwinia | 28.95 |

Erwinia rhapontici Erwinia aphidicola |

2.63 5.26 |

| Rosenbergiella | 18.42 | - | - |

| Frigoribacterium | 15.79 | - | - |

| Stenotrophomonas | 7.89 | Stenotrophomonas maltophilia | 2.63 |

| Pseudomonas | 13.16 | Pseudomonas poae | 2.63 |

| Ochrobactrum | 10.53 | - | - |

| Arthrobacter | 10.53 | - | - |

| Uncultured bacterium | 7.89 | Uncultured bacterium - | 7.89 |

| Exiguobacterium | 5.26 | - | - |

| Curtobacterium | 7.89 | - | - |

| Microbacterium | 5.26 | - | - |

| Clavibacter | 5.26 | Clavibacter michiganensis | 5.26 |

| Bacteria | 5.26 | Bacteria | 5.26 |

| Rathayibacter | 2.63 | Rathayibacter festucae | 2.63 |

| Enterococcus | 5.26 | Enterococcus mundtii | 5.26 |

| Agrococcus | 2.63 | Agrococcus jenensis | 2.63 |

| Plantibacter | 5.26 | Plantibacter flavus | 2.63 |

| Enterobacter | 2.63 | - | - |

4. Discussion

5. Conclusion

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Eurasian Research Institute (ERI) 2020. An Overview of Agricultural Development of Russia. https://www.eurasian-research.org/publication/an-overview-of-agricultural-development-of-russia/. Accessed 30.12.2022.

- Kapoguzov, E.A., Chupin, R.I., Aleshchenko, V.V. and Bykov, A.A. cereals export factors and impact on wheat price in Russian regions. J. Sib. Fed. Univ. Humanit. soc. sci., 2021/14(12), 1782–1794. DOI: 10.17516/1997-1370-0858. [CrossRef]

- FAO. 2017 Phytosanitary certificates. International Plant Protection Convention https://www.ippc.int/static/media/files/publication/en/2017/10/ISPM_12_2014_En_2017-10-26_InkAm.pdf Accessed 30.12.2022.

- Observatory of Economic Complexity (OEC) 2023 https://oec.world/en/profile/bilateral-product/wheat/reporter/rus?redirect=true Accessed 15.05.2023.

- Fitzgerald TL, Powell JJ, Schneebeli K, Hsia MM, Gardiner DM, Bragg JN, McIntyre CL, Manners JM, Ayliffe M, Watt M, Vogel JP, Henry RJ, Kazan K. Brachypodium as an emerging model for cereal-pathogen interactions. Ann Bot. 2015 Apr;115(5):717-31. doi: 10.1093/aob/mcv010. PMID: 25808446; PMCID: PMC4373291. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sadia Latif, Sameeda Bibi, Rabia Kouser, Hina Fatimah, Saba Farooq, Samar Naseer, Rizwana Kousar, Characterization of bacterial community structure in the rhizosphere of Triticum aestivum L. Genomics, 2020 112(6) 4760-4768.

- Guilbaud C, Morris CE, Barakat M, Ortet P, Berge O. Isolation and identification of Pseudomonas syringae facilitated by a PCR targeting the whole P. syringae group. FEMS Microbiol Ecol. 2016 Jan;92(1): fiv146. doi: 10.1093/femsec/fiv146. Epub 2015 Nov 25. PMID: 26610434. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- FAO 2023. Global body adopts new measures to stop the spread of plant pests https://www.fao.org/news/story/en/item/1118322/icode/. Accessed 19.03.2023.

- Slovareva O.Y. Detection and identification of wheat and barley phytopathogens in the Russian Federation. Microbiology Independent Research Journal MIR Journal. 2020;7(1):13-23. https://doi.org/10.18527/2500-2236-2020-7-1-13-23. [CrossRef]

- Dutta B, Gitaitis RD, Sanders FH, Booth C, Smith S, Langston DB. First Report of Bacterial Leaf Spot of Pumpkin Caused by Xanthomonas cucurbitae in Georgia, United States. Plant Dis. 2013 Oct;97(10):1375. doi: 10.1094/PDIS-03-13-0317-PDN. PMID: 30722167. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Honda-Takinami R., Hata J., Matsuoka K., Hoshi S., Koguchi T., Sato Y., Akaihata H., Kataoka M., Ogawa S., Nishiyama K., Suzutani T., Kojima Y. Association between the presence of bacteria in prostate tissue and histopathology in biopsies from men not complaining of lower urinary tract symptoms. Fukushima Journal of Medical Science, 2022, 68(3): 161-167 (doi: 10.5387/fms.2022-34). [CrossRef]

- Mao DP, Zhou Q, Chen CY, Quan ZX. Coverage evaluation of universal bacterial primers using the metagenomic datasets. BMC Microbiol. 2012 May 3; 12:66. doi: 10.1186/1471-2180-12-66. PMID: 22554309; PMCID: PMC3445835. [CrossRef]

- Kazempour M.N, Kheyrgoo M., Pedramfar H., Rahimian H. Isolation and identification of bacterial glum blotch and leaf blight on wheat (Triticum aestivum L.) in Iran. African Journal of Biotechnology, 2010, 9(20): 2860-2865.

- Белкин Д.Л., Бoндаренкo Г.Н., Яремкo А.Б., Уварoва Д.А. Метoд секвенирoвания в видoвoй идентификации карантинных вредных oрганизмoв. Карантин растений. Наука и практика, 2019, 28(2): 31-34.

- Минаева Л.П., Самoхвалoва Л.В., Завриев С.К., Стахеев А.А. Первoе выявление гриба Fusarium coffeatum на территoрии Рoссийскoй Федерации. Сельскoхoзяйственная биoлoгия, 2022, 57(1): 131-140 (doi: 10.15389/agrobiology.2022.1.131rus). [CrossRef]

- Krawczyk, K.; Foryś, J.; Nakonieczny, M.; Tarnawska, M.; Bereś, P.K. Transmission of Pantoea ananatis, the causal agent of leaf spot disease of maize (Zea mays), by western corn rootworm (Diabrotica virgifera virgifera LeConte). Crop Prot. 2020.

- Harada H, Oyaizu H, Kosako Y, Ishikawa H. Erwinia aphidicola, a new species isolated from pea aphid, Acyrthosiphon pisum. J Gen Appl Microbiol. 1997 Dec;43(6):349-354. doi: 10.2323/jgam.43.349. PMID: 12501306. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bruisson S, Zufferey M, L’Haridon F, Trutmann E, Anand A, Dutartre A, De Vrieze M, Weisskopf L. Endophytes and Epiphytes from the Grapevine Leaf Microbiome as Potential Biocontrol Agents Against Phytopathogens. Frontiers in Microbiology. 2019. 10.3389/fmicb.2019.02726 ISSN=1664-302X. [CrossRef]

- Yang Y, Yang J, Wu WM, Zhao J, Song Y, Gao L, Yang R, Jiang L. "Biodegradation and Mineralization of Polystyrene by Plastic-Eating Mealworms: Part 2. Role of Gut Microorganisms". Environ. Sci. Technol. 2015 49 (20): 12087–93. Bibcode:2015EnST...4912087Y. doi: 10.1021/acs.est.5b02663. PMID 26390390. [CrossRef]

- Carobbi A, Di Nepi S, Fridman CM, Dar Y, Ben-Yaakov R, Barash I, Salomon D, Sessa G. An antibacterial T6SS in Pantoea agglomerans pv. betae delivers a lysozyme-like effector to antagonize competitors. Environ Microbiol. 2022 Oct;24(10):4787-4802. doi: 10.1111/1462-2920.16100. Epub 2022 Jun 20. PMID: 35706135; PMCID: PMC9796082. [CrossRef]

- van Teeseling MCF, de Pedro MA and Cava F. Determinants of Bacterial Morphology: From Fundamentals to Possibilities for Antimicrobial Targeting. Front. Microbiol.2017. 8:1264. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2017.01264. [CrossRef]

- Krawczyk K, Wielkopolan B, Obrępalska-Stęplowska A. Pantoea ananatis, A New Bacterial Pathogen Affecting Wheat Plants (Triticum aestivum L.) in Poland. Pathogens. 2020 Dec 21;9(12):1079. doi: 10.3390/pathogens9121079. PMID: 33371529; PMCID: PMC7767503. [CrossRef]

- Yu L, Yang C, Ji Z, Zeng Y, Liang Y, Hou Y. Complete Genomic Data of Pantoea ananatis Strain TZ39 Associated with New Bacterial Blight of Rice in China. Plant Dis. 2022 Feb;106(2):751-753. doi: 10.1094/PDIS-08-21-1845-A. Epub 2022 Feb 9. PMID: 34597149. [CrossRef]

- Tahir M, Khan MB, Shahid M, Ahmad I, Khalid U, Akram M, Dawood A, Kamran M. Metal-tolerant Pantoea sp. WP-5 and organic manures enhanced root exudation and phytostabilization of cadmium in the rhizosphere of maize. Environ Sci Pollut Res Int. 2022 Jan;29(4):6026-6039. doi: 10.1007/s11356-021-16018-3. Epub 2021 Aug 25. PMID: 34431061. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang Z, Liu H, Song W, Ma W, Hu W, Chen T, Liu L. Accumulation of U(VI) on the Pantoea sp. TW18 isolated from radionuclide-contaminated soils. J Environ Radioact. 2018 Dec; 192:219-226. doi: 10.1016/j.jenvrad.2018.07.002. Epub 2018 Jul 6. PMID: 29982006. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dutkiewicz J, Mackiewicz B, Kinga Lemieszek M, Golec M, Milanowski J. Pantoea agglomerans: a mysterious bacterium of evil and good. Part III. Deleterious effects: infections of humans, animals and plants. Ann Agric Environ Med. 2016 Jun 2;23(2):197-205. doi: 10.5604/12321966.1203878. PMID: 27294620. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gitaitis, R.D.; Walcott, R.R.; Wells, M.L.; Perez, J.C.D.; Sanders, F.H. Transmission of Pantoea ananatis, Causal Agent of Center Rot of Onion, by Tobacco Thrips, Frankliniella fusca. Plant Dis. 2003, 87, 675–678.

- Gitaitis, R.D.; Walcott, R.R.; Wells, M.L.; Perez, J.C.D.; Sanders, F.H. Transmission of Pantoea ananatis, Causal Agent of Center Rot of Onion, by Tobacco Thrips, Frankliniella fusca. Plant Dis. 2003, 87, 675–678.

- Coutinho, T.A.; Venter, S.N. Pantoea ananatis: An unconventional plant pathogen. Mol. Plant Pathol. 2009, 10, 325–335.

- Krawczyk, K.; Wielkopolan, B.; Obrępalska-Stęplowska, A. Pantoea ananatis, A New Bacterial Pathogen Affecting Wheat Plants (Triticum L.) in Poland. Pathogens 2020, 9, 1079.

- Murrell, A.; Dobson, S.J.; Yang, X.; Lacey, E.; Barker, S.C. A survey of bacterial diversity in ticks, lice and fleas from Australia. Parasitol. Res. 2003, 89, 326–334.

- Yuan T, Huang Y, Luo L, Wang J, Li J, Chen J, Qin Y, Liu J. Complete Genome Sequence of Pantoea ananatis strain LCFJ-001, Isolated from Bacterial Wilt Mulberry. Plant Dis. 2023 Jan 23. doi: 10.1094/PDIS-10-22-2473-A. Epub ahead of print. PMID: 36691281. [CrossRef]

- Usuda Y, Nishio Y, Nonaka G, Hara Y. Microbial Production Potential of Pantoea ananatis: From Amino Acids to Secondary Metabolites. Microorganisms. 2022 May 31;10(6):1133. doi: 10.3390/microorganisms10061133. PMID: 35744651; PMCID: PMC9231021. [CrossRef]

- Chen X, Sun Q, Tang L, Guo T, Huang S, Mo J, Li Q. First Report of Bacterial Necrosis Caused by Pantoea vagans in Mango in China. Plant Dis. 2022 Nov 9. doi: 10.1094/PDIS-08-22-1950-PDN. Epub ahead of print. PMID: 36350723. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brady CL, Venter SN, Cleenwerck I, Engelbeen K, Vancanneyt M, Swings J, Coutinho TA. Pantoea vagans sp. nov., Pantoea eucalypti sp. nov., Pantoea deleyi sp. nov. and Pantoea anthophila sp. nov. Int J Syst Evol Microbiol. 2009 Sep;59(Pt 9):2339-45. doi: 10.1099/ijs.0.009241-0. Epub 2009 Jul 20. PMID: 19620357. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Silvana Díaz Herreraa, Cecilia Grossi, Myriam Zawoznika, María Daniela Groppa. Wheat seeds harbour bacterial endophytes with potential as plant growth promoters and biocontrol agents of Fusarium graminearum. Microbiological Research. 2016 37–43.

- Ma Y, Yin Y, Rong C, Chen S, Liu Y, Wang S, Xu F. Pantoea pleuroti sp. nov., Isolated from the Fruiting Bodies of Pleurotus eryngii. Curr Microbiol. 2016 Feb;72(2):207-212. doi: 10.1007/s00284-015-0940-5. Epub 2015 Nov 19. PMID: 26581526. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pan MK, Feng GD, Yao Q, Li J, Liu C, Zhu H. Erwinia phyllosphaerae sp. nov., a novel bacterium isolated from phyllosphere of pomelo (Citrus maxima). Int J Syst Evol Microbiol. 2022 Apr;72(4). doi: 10.1099/ijsem.0.005316. PMID: 35416765. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sagar A, Sing A., Labhane N., Riyazuddin R., Marker S., Parihar D.K and Ramteke P.W. Native bacterium Erwinia sp. (PR16) enhances growth and yield of wheat variety AAI-W6 under reduced level of NPK. International Journal of Life Sciences and Applied Sciences. 2020, 2 27-36.

- Campillo T, Luna E, Portier P, Fischer-Le Saux M, Lapitan N, Tisserat NA, Leach JE. Erwinia iniecta sp. nov., isolated from Russian wheat aphid (Diuraphis noxia). Int J Syst Evol Microbiol. 2015 Oct;65(10):3625-3633. doi: 10.1099/ijsem.0.000466. PMID: 26198254. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morohoshi T, Nameki K, Someya N. Comparative genome analysis reveals the presence of multiple quorum-sensing systems in plant pathogenic bacterium, Erwinia rhapontici. Biosci Biotechnol Biochem. 2021 Jul 23;85(8):1910-1914. doi: 10.1093/bbb/zbab104. PMID: 34100908. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Krawczyk, K.; Wielkopolan, B.; Obrępalska-Stęplowska, A. Pantoea ananatis, A New Bacterial Pathogen Affecting Wheat Plants (Triticum L.) in Poland. Pathogens 2020, 9, 1079.

- Halpern M, Fridman S, Atamna-Ismaeel N, Izhaki I. Rosenbergiella nectarea gen. nov., sp. nov., in the family Enterobacteriaceae, isolated from floral nectar. Int J Syst Evol Microbiol. 2013 Nov;63(Pt 11):4259-4265. doi: 10.1099/ijs.0.052217-0. Epub 2013 Jul 5. PMID: 23832968. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Asif M, Eudes F, Randhawa H, Amundsen E, Yanke J, Spaner D. Cefotaxime prevents microbial contamination and improves microspore embryogenesis in wheat and triticale. Plant Cell Rep. 2013 Oct;32(10):1637-46. doi: 10.1007/s00299-013-1476-4. Epub 2013 Jul 30. PMID: 23896731. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ryan RP, Monchy S, Cardinale M, Taghavi S, Crossman L, Avison MB, Berg G, van der Lelie D, Dow JM. The versatility and adaptation of bacteria from the genus Stenotrophomonas. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2009 Jul;7(7):514-25. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro2163. PMID: 19528958. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Haque MM, Mosharaf MK, Khatun M, Haque MA, Biswas MS, Islam MS, Islam MM, Shozib HB, Miah MMU, Molla AH, Siddiquee MA. Biofilm Producing Rhizobacteria with Multiple Plant Growth-Promoting Traits Promote Growth of Tomato Under Water-Deficit Stress. Front Microbiol. 2020 Nov 26;11 :542053. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2020.542053. PMID: 33324354; PMCID: PMC7727330. [CrossRef]

- Gilligan PH, Lum G, VanDamme PAR, Whittier S. Murray PR, Baron EJ, Jorgensen JH, et al. (eds.). Burkholderia, Stenotrophomonas, Ralstonia, Brevundimonas, Comamonas, Delftia, Pandoraea, and Acidivorax. In: Manual of Clinical Microbiology (8th ed.). 2003 ASM Press, Washington, DC. pp. 729–748. ISBN 978-1-55581-255.

- Euzéby JP. List of Bacterial Names with Standing in Nomenclature: a folder available on the Internet. Int J Syst Bacteriol. 1997 Apr;47(2):590-2. doi: 10.1099/00207713-47-2-590. PMID: 9103655. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Anzai Y, Kim H, Park JY, Wakabayashi H, Oyaizu H. Phylogenetic affiliation of the pseudomonads based on 16S rRNA sequence. Int J Syst Evol Microbiol. 2000 Jul;50 Pt 4:1563-1589. doi: 10.1099/00207713-50-4-1563. PMID: 10939664. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arnold DL, Preston GM. Pseudomonas syringae: enterprising epiphyte and stealthy parasite. Microbiology (Reading). 2019 Mar;165(3):251-253. doi: 10.1099/mic.0.000715. Epub 2018 Nov 14. PMID: 30427303. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Krawczyk, K.; Wielkopolan, B.; Obrępalska-Stęplowska, A. Pantoea ananatis, A New Bacterial Pathogen Affecting Wheat Plants (Triticum L.) in Poland. Pathogens 2020, 9, 1079.

- Diggle SP, Whiteley M. Microbe Profile: Pseudomonas aeruginosa: opportunistic pathogen and lab rat. Microbiology (Reading). 2020 Jan;166(1):30-33. doi: 10.1099/mic.0.000860. Erratum in: Microbiology (Reading). 2021 Aug;167(8): PMID: 31597590; PMCID: PMC7273324. [CrossRef]

- Padda KP, Puri A, Chanway C. Endophytic nitrogen fixation - a possible ’hidden’ source of nitrogen for lodgepole pine trees growing at un-reclaimed gravel mining sites. FEMS Microbiol Ecol. 2019 Nov 1;95(11): fiz172. doi: 10.1093/femsec/fiz172. PMID: 31647534. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yuan QS, Wang L, Wang H, Wang X, Jiang W, Ou X, Xiao C, Gao Y, Xu J, Yang Y, Cui X, Guo L, Huang L, Zhou T. Pathogen-Mediated Assembly of Plant-Beneficial Bacteria to Alleviate Fusarium Wilt in Pseudostellaria heterophylla. Front Microbiol. 2022 Mar 30;13: 842372. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2022.842372. PMID: 35432244; PMCID: PMC9005978. [CrossRef]

- Irshad U, Yergeau E. Bacterial Subspecies Variation and Nematode Grazing Change P Dynamics in the Wheat Rhizosphere. Front Microbiol. 2018 Sep 5;9: 1990. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2018.01990. PMID: 30233510; PMCID: PMC6134019. [CrossRef]

- Oh EJ, Hwang IS, Park IW, Oh CS. Comparative Genome Analyses of Clavibacter michiganensis Type Strain LMG7333T Reveal Distinct Gene Contents in Plasmids from Other Clavibacter Species. Front Microbiol. 2022 Feb 1;12: 793345. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2021.793345. PMID: 35178040; PMCID: PMC8844524. [CrossRef]

- Eichenlaub R, Gartemann KH. The Clavibacter michiganensis subspecies: molecular investigation of gram-positive bacterial plant pathogens. Annu Rev Phytopathol. 2011; 49:445-64. doi: 10.1146/annurev-phyto-072910-095258. PMID: 21438679. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baek KY, Lee HH, Son GJ, Lee PA, Roy N, Seo YS, Lee SW. Specific and Sensitive Primers Developed by Comparative Genomics to Detect Bacterial Pathogens in Grains. Plant Pathol J. 2018 Apr;34(2):104-112. doi: 10.5423/PPJ.OA.11.2017.0250. Epub 2018 Apr 1. PMID: 29628816; PMCID: PMC5880354. [CrossRef]

- Shree P. Thapa, Sivakumar Pattathil, Michael G. Hahn, Marie-Agnès Jacques, Robert L. Gilbertson, and Gitta Coaker. Genomic Analysis of Clavibacter michiganensis Reveals Insight into Virulence Strategies and Genetic Diversity of a Gram-Positive Bacterial Pathogen. Molecular Plant-Microbe Interactions. 2017 30 (10), 786-802.

- Lymperopoulou DS, Coil DA, Schichnes D, Lindow SE, Jospin G, Eisen JA, Adams RI. Draft genome sequences of eight bacteria isolated from the indoor environment: Staphylococcus capitis strain H36, S. capitis strain H65, S. cohnii strain H62, S. hominis strain H69, Microbacterium sp. strain H83, Mycobacterium iranicum strain H39, Plantibacter sp. strain H53, and Pseudomonas oryzihabitans strain H72. Stand Genomic Sci. 2017 Jan 31; 12:17. doi: 10.1186/s40793-017-0223-9. PMID: 28163826; PMCID: PMC5282799. [CrossRef]

- Lymperopoulou DS, Coil DA, Schichnes D, Lindow SE, Jospin G, Eisen JA, Adams RI. Draft genome sequences of eight bacteria isolated from the indoor environment: Staphylococcus capitis strain H36, S. capitis strain H65, S. cohnii strain H62, S. hominis strain H69, Microbacterium sp. strain H83, Mycobacterium iranicum strain H39, Plantibacter sp. strain H53, and Pseudomonas oryzihabitans strain H72. Stand Genomic Sci. 2017 Jan 31; 12:17. doi: 10.1186/s40793-017-0223-9. PMID: 28163826; PMCID: PMC5282799. [CrossRef]

- Tarlachkov SV, Starodumova IP, Dorofeeva LV, Prisyazhnaya NV, Roubtsova TV, Chizhov VN, Nadler SA, Subbotin SA, Evtushenko LI. 2021. Draft genome sequences of 28 actinobacteria of the family Microbacteriaceae associated with nematode-infected plants. Microbiol Resour Announc 10: e01400-20. https://doi.org/10.1128/MRA.01400-20. [CrossRef]

- Tarlachkov SV, Ospennikov YV, Demidov AV, Starodumova IP, Dorofeeva LV, Prisyazhnaya NV, Chizhov VN, Subbotin SA, Evtushenko LI. Draft Genome Sequences of 9 Actinobacteria from the Family Microbacteriaceae Associated with Insect- and Nematode-Damaged Plants. Microbiol Resour Announc. 2022 Oct 20;11(10):e0048722. doi: 10.1128/mra.00487-22. Epub 2022 Aug 31. PMID: 36043868; PMCID: PMC9584284.]. [CrossRef]

- Mayer E, Dörr de Quadros P, Fulthorpe R. Plantibacter flavus, Curtobacterium herbarum, Paenibacillus taichungensis, and Rhizobium selenitireducens Endophytes Provide Host-Specific Growth Promotion of Arabidopsis thaliana, Basil, Lettuce, and Bok Choy Plants. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2019 Sep 17;85(19): e00383-19. doi: 10.1128/AEM.00383-19. PMID: 31350315; PMCID: PMC6752021. [CrossRef]

- Dimkić I, Bhardwaj V, Carpentieri-Pipolo V, Kuzmanović N, Degrassi G. The chitinolytic activity of the Curtobacterium sp. isolated from field-grown soybean and analysis of its genome sequence. PLoS One. 2021 Nov 3;16(11): e0259465. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0259465. PMID: 34731210; PMCID: PMC8565777. [CrossRef]

- Kariluoto S, Edelmann M, Herranen M, Lampi AM, Shmelev A, Salovaara H, Korhola M, Piironen V. Production of folate by bacteria isolated from oat bran. Int J Food Microbiol. 2010 Sep 30;143(1-2):41-7. doi: 10.1016/j.ijfoodmicro.2010.07.026. Epub 2010 Aug 11. PMID: 20708290. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bastas KK and Sahin F. Evaluation of seedborne bacterial pathogens on common bean cultivars grown in central Anatolia region. Turkey. European Journal of Plant Pathology, 2017 147, 239–253.

- EFSA Panel on Plant Health (EFSA PLH Panel); Jeger M, Bragard C, Caffier D, Candresse T, Chatzivassiliou E, Dehnen-Schmutz K, Gilioli G, Grégoire JC, Jaques Miret JA, MacLeod A, Navajas Navarro M, Niere B, Parnell S, Potting R, Rafoss T, Rossi V, Urek G, Van Bruggen A, Van der Werf W, West J, Winter S, Tegli S, Hollo G, Caffier D. Pest categorisation of Curtobacterium flaccumfaciens pv. flaccumfaciens. EFSA J. 2018 May 31;16(5): e05299. doi: 10.2903/j.efsa.2018.5299. PMID: 32625922; PMCID: PMC7009624. [CrossRef]

- Mei L, Piao Z, Hu J, Shi L, Bai Y, Yin S. Lysinimonas yzui sp. nov., isolated from cattail root soil from mine tailings. Int J Syst Evol Microbiol. 2020 Mar;70(3):2003-2007. doi: 10.1099/ijsem.0.004013. PMID: 32234114. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dorofeeva LV, Evtushenko LI, Krausova VI, Karpov AV, Subbotin SA, Tiedje JM. Rathayibacter caricis sp. nov. and Rathayibacter festucae sp. nov., isolated from the phyllosphere of Carex sp. and the leaf gall induced by the nematode Anguina graminis on Festuca rubra L., respectively. Int J Syst Evol Microbiol. 2002 Nov;52(Pt 6):1917-1923. doi: 10.1099/00207713-52-6-1917. PMID: 12508848. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dorofeeva LV, Evtushenko LI, Krausova VI, Karpov AV, Subbotin SA, Tiedje JM. Rathayibacter caricis sp. nov. and Rathayibacter festucae sp. nov., isolated from the phyllosphere of Carex sp. and the leaf gall induced by the nematode Anguina graminis on Festuca rubra L., respectively. Int J Syst Evol Microbiol. 2002 Nov;52(Pt 6):1917-1923. doi: 10.1099/00207713-52-6-1917. PMID: 12508848. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dhanjal S, Kaur I, Korpole S, Schumann P, Cameotra SS, Pukall R, Klenk HP, Mayilraj S. Agrococcus carbonis sp. nov., isolated from soil of a coal mine. Int J Syst Evol Microbiol. 2011 Jun;61(Pt 6):1253-1258. doi: 10.1099/ijs.0.024745-0. Epub 2010 Jul 2. PMID: 20601492. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lau KJX, Junqueira ACM, Uchida A, Purbojati RW, Houghton JNI, Chénard C, Wong A, Kolundžija S, Clare ME, Kushwaha KK, Putra A, Gaultier NE, Heinle CE, Premkrishnan BNV, Vettah VK, Drautz-Moses DI, Schuster SC. Complete Genome Sequence of Agrococcus sp. Strain SGAir0287, Isolated from Tropical Air Collected in Singapore. Microbiol Resour Announc. 2019 Aug 8;8(32): e00616-19. doi: 10.1128/MRA.00616-19. PMID: 31395637; PMCID: PMC6687924. [CrossRef]

- Fisher K, Phillips C. The ecology, epidemiology and virulence of Enterococcus. Microbiology (Reading). 2009 Jun;155(Pt 6):1749-1757. doi: 10.1099/mic.0.026385-0. Epub 2009 Apr 21. PMID: 19383684. [CrossRef]

- Yimin Cai. Identification and Characterization of Enterococcus Species Isolated from Forage Crops and Their Influence on Silage Fermentation. Journal of Dairy Science. 1999. 82 (11) 2466-2471.

- Gaetano Guida, Raimondo Gaglio, Alessandro Miceli, Vito Armando Laudicina, Luca Settanni. Biological control of Listeria monocytogenes in soil model systems by Enterococcus mundtii strains expressing mundticin KS production. Applied Soil Ecology. 2022. 170.

- Halpern M, Fridman S, Atamna-Ismaeel N, Izhaki I. Rosenbergiella nectarea gen. nov., sp. nov., in the family Enterobacteriaceae, isolated from floral nectar. Int J Syst Evol Microbiol. 2013 Nov;63(Pt 11):4259-4265. doi: 10.1099/ijs.0.052217-0. Epub 2013 Jul 5. PMID: 23832968. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Caneschi WL, Felestrino ÉB, Fonseca NP, Villa MM, Lemes CGC, Cordeiro IF, Assis RAB, Sanchez AB, Vieira IT, Kamino LHY, do Carmo FF, Garcia CCM, Moreira LM. Brazilian Ironstone Plant Communities as Reservoirs of Culturable Bacteria with Diverse Biotechnological Potential. Front Microbiol. 2018 Jul 23; 9:1638. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2018.01638. PMID: 30083146; PMCID: PMC6064971. [CrossRef]

- Li AH, Liu HC, Xin YH, Kim SG, Zhou YG. Glaciihabitans tibetensis gen. nov., sp. nov., a psychrotolerant bacterium of the family Microbacteriaceae, isolated from glacier ice water. Int J Syst Evol Microbiol. 2014 Feb;64(Pt 2):579-587. doi: 10.1099/ijs.0.052670-0. Epub 2013 Oct 24. PMID: 24158943. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang HF, Zhang YG, Chen JY, Guo JW, Li L, Hozzein WN, Zhang YM, Wadaan MAM, Li WJ. Frigoribacterium endophyticum sp. nov., an endophytic actinobacterium isolated from the root of Anabasis elatior (C. A. Mey.) Schischk. Int J Syst Evol Microbiol. 2015 Apr;65(Pt 4):1207-1212. doi: 10.1099/ijs.0.000081. Epub 2015 Jan 21. PMID: 25609679. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Poszytek K, Karczewska-Golec J, Ciok A, Decewicz P, Dziurzynski M, Gorecki A, Jakusz G, Krucon T, Lomza P, Romaniuk K, Styczynski M, Yang Z, Drewniak L, Dziewit L. Genome-Guided Characterization of Ochrobactrum sp. POC9 Enhancing Sewage Sludge Utilization-Biotechnological Potential and Biosafety Considerations. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2018 Jul 16;15(7):1501. doi: 10.3390/ijerph15071501. PMID: 30013002; PMCID: PMC6069005. [CrossRef]

- Patel, J.K., Gohel, K., Patel, H. et al. Wheat Growth Dependent Succession of Culturable Endophytic Bacteria and Their Plant Growth Promoting Traits. Curr Microbiol 78, 4103–4114 (2021).

- Li X, Li S, Wu Y, Li J, Xing P, Wei G, Shi P. Arthrobacter rhizosphaerae sp. nov., isolated from wheat rhizosphere. Arch Microbiol. 2022 Aug 6;204(9):543. doi: 10.1007/s00203-022-03150-y. PMID: 35932431. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang Y, Yang J, Wu WM, Zhao J, Song Y, Gao L, Yang R, Jiang L. Biodegradation and Mineralization of Polystyrene by Plastic-Eating Mealworms: Part 2. Role of Gut Microorganisms. Environ Sci Technol. 2015 Oct 20;49(20):12087-93. doi: 10.1021/acs.est.5b02663. Epub 2015 Oct 1. PMID: 26390390. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Collins MD, Lund BM, Farrow JA, Schleifer KH (1983). "Chemotaxonomic study of an alkaliphilic bacterium, Exiguobacterium aurantiacum gen nov., sp. nov". J. Gen. Microbiol. 1983 129 (7): 2037–2042.

- Lymperopoulou DS, Coil DA, Schichnes D, Lindow SE, Jospin G, Eisen JA, Adams RI. Draft genome sequences of eight bacteria isolated from the indoor environment: Staphylococcus capitis strain H36, S. capitis strain H65, S. cohnii strain H62, S. hominis strain H69, Microbacterium sp. strain H83, Mycobacterium iranicum strain H39, Plantibacter sp. strain H53, and Pseudomonas oryzihabitans strain H72. Stand Genomic Sci. 2017 Jan 31; 12:17. doi: 10.1186/s40793-017-0223-9. PMID: 28163826; PMCID: PMC5282799. [CrossRef]

- Wang C, Wu W, Wei L, Feng Y, Kang M, Xie Y, Zong Z. Enterobacter wuhouensis sp. nov. and Enterobacter quasihormaechei sp. nov. recovered from human sputum. Int J Syst Evol Microbiol. 2020 Feb;70(2):874-881. doi: 10.1099/ijsem.0.003837. PMID: 31702537. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang Z, Liu H, Karani H, Mallen J, Chen W, De A, Mani S, Tang JX. Enterobacter sp. Strain SM1_HS2B Manifests Transient Elongation and Swimming Motility in Liquid Medium. Microbiol Spectr. 2022 Jun 29;10(3): e0207821. doi: 10.1128/spectrum.02078-21. Epub 2022 Jun 1. PMID: 35647691; PMCID: PMC9241836. [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).