Submitted:

19 July 2023

Posted:

20 July 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

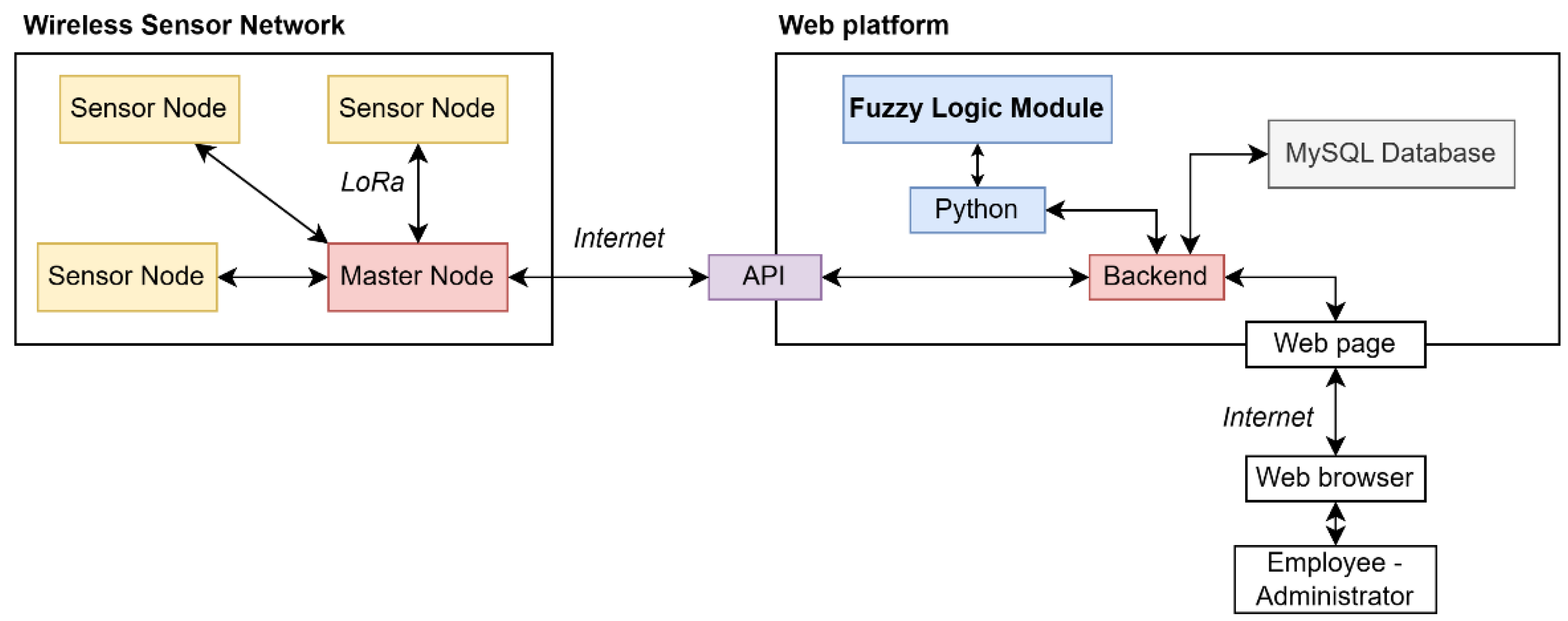

2.1. Wireless Sensor Network

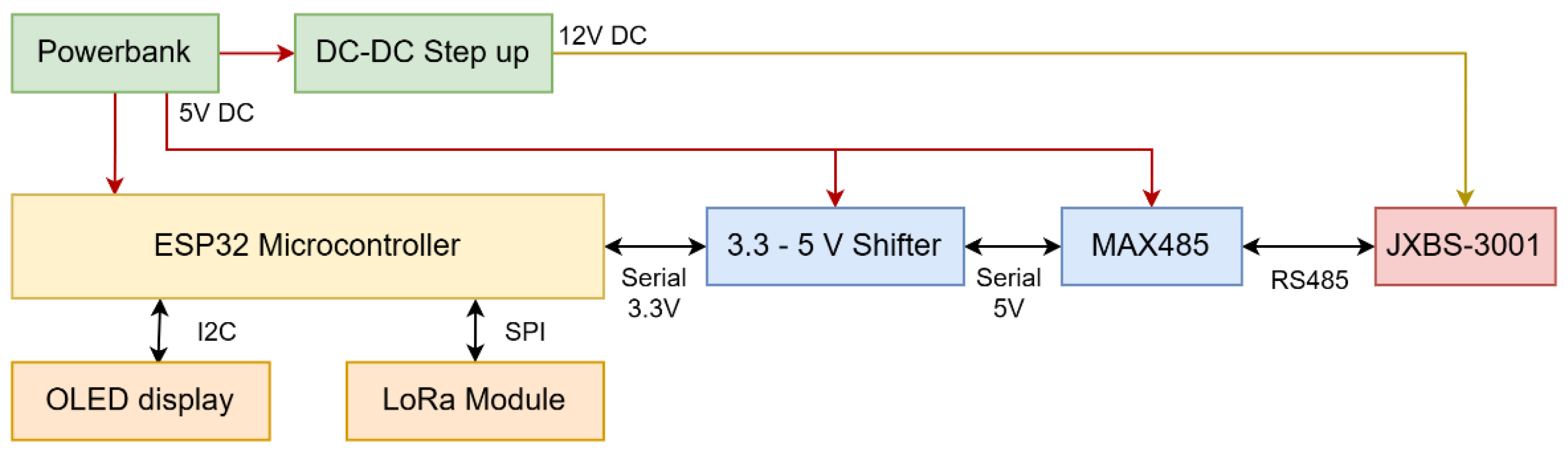

2.1.1. Hardware and Software

2.1.2. Data Transmission

2.1.3. Data Storage

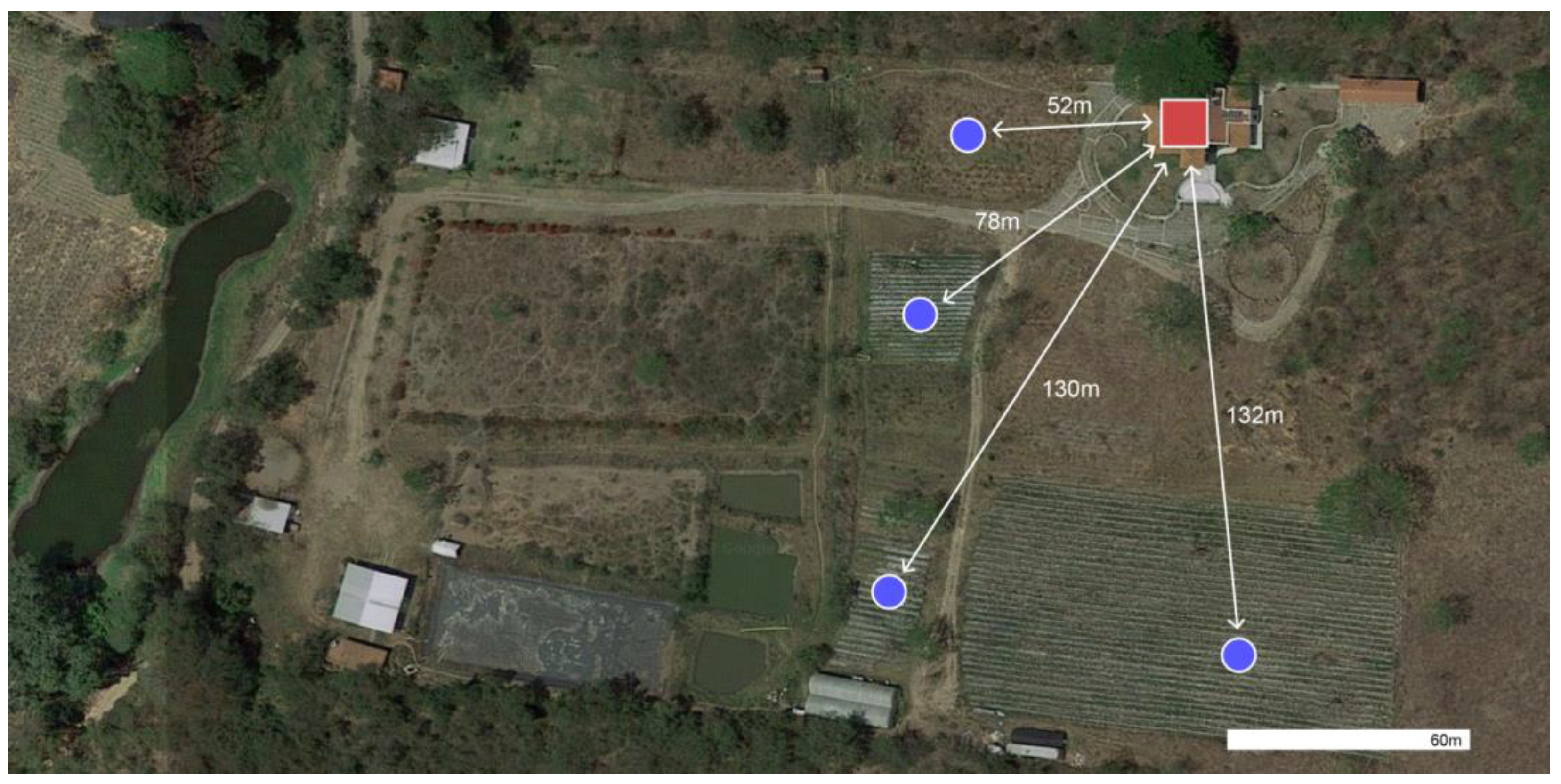

2.1.4. Implementation

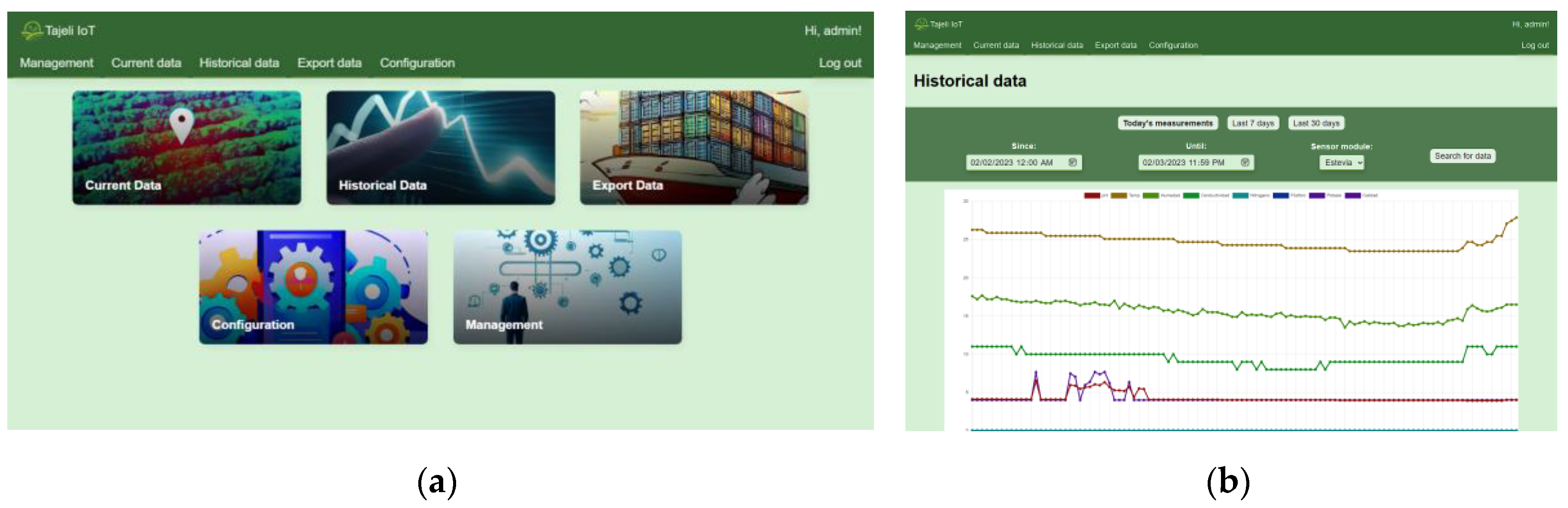

2.2. Web-Based Platform

2.2.1. Web-Platform Functionality (Use Cases)

2.2.2. Structure

2.2.3. Database

2.2.4. API Endpoints

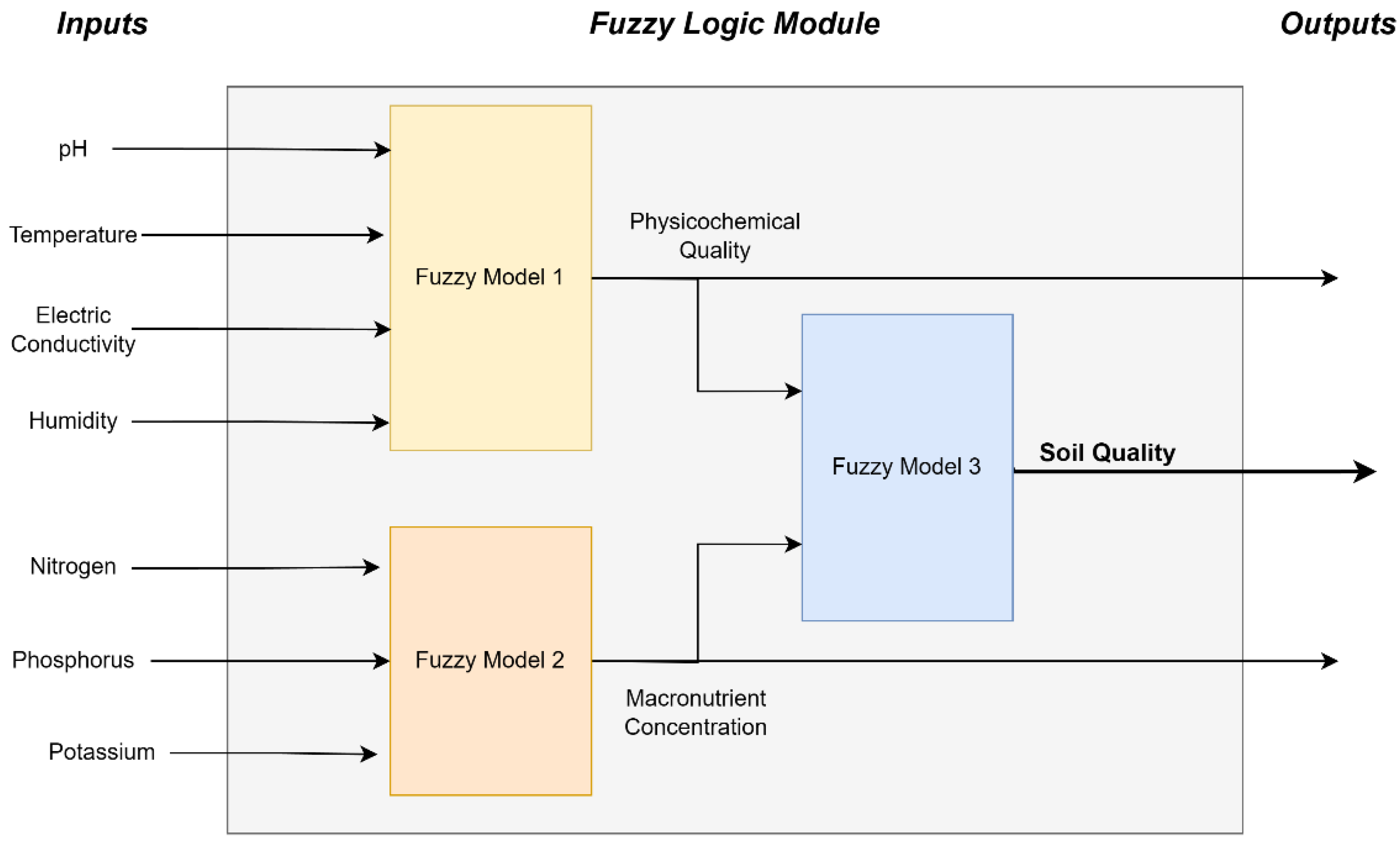

2.3. Fuzzy Logic Model (FLM)

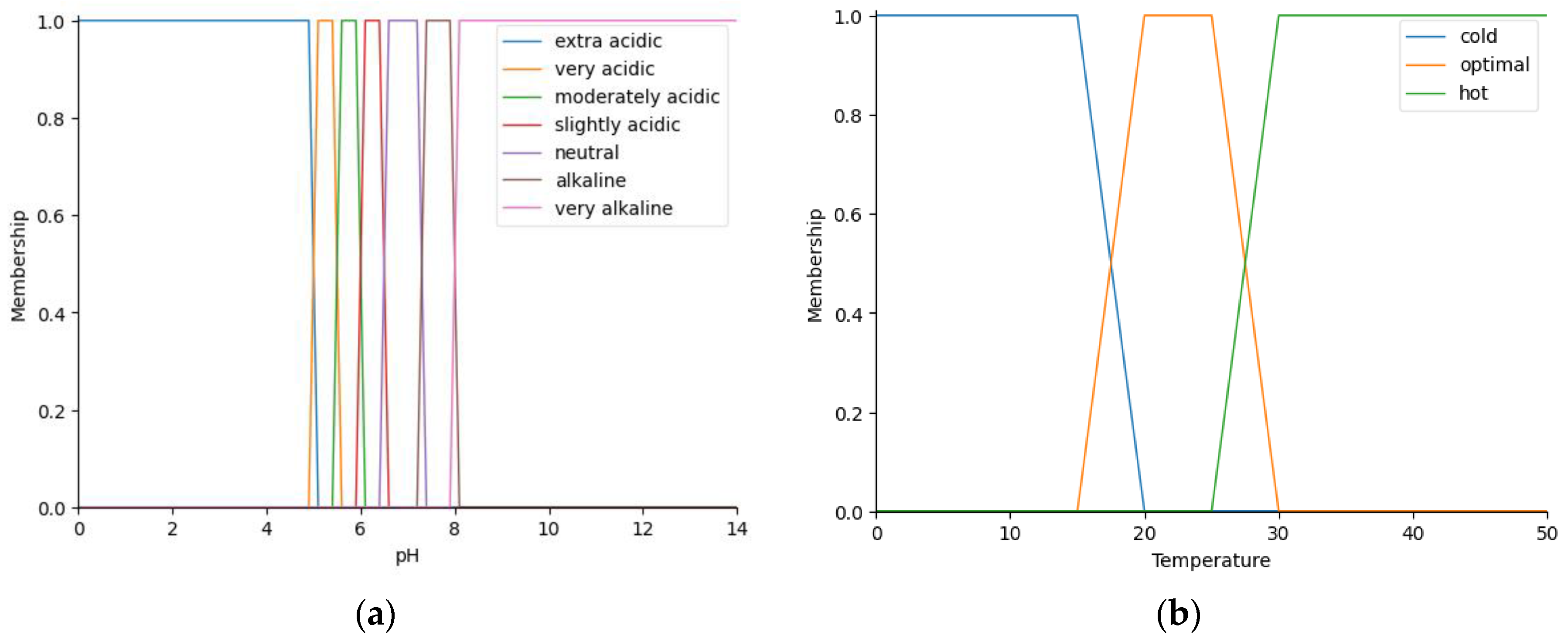

2.3.1. Inputs

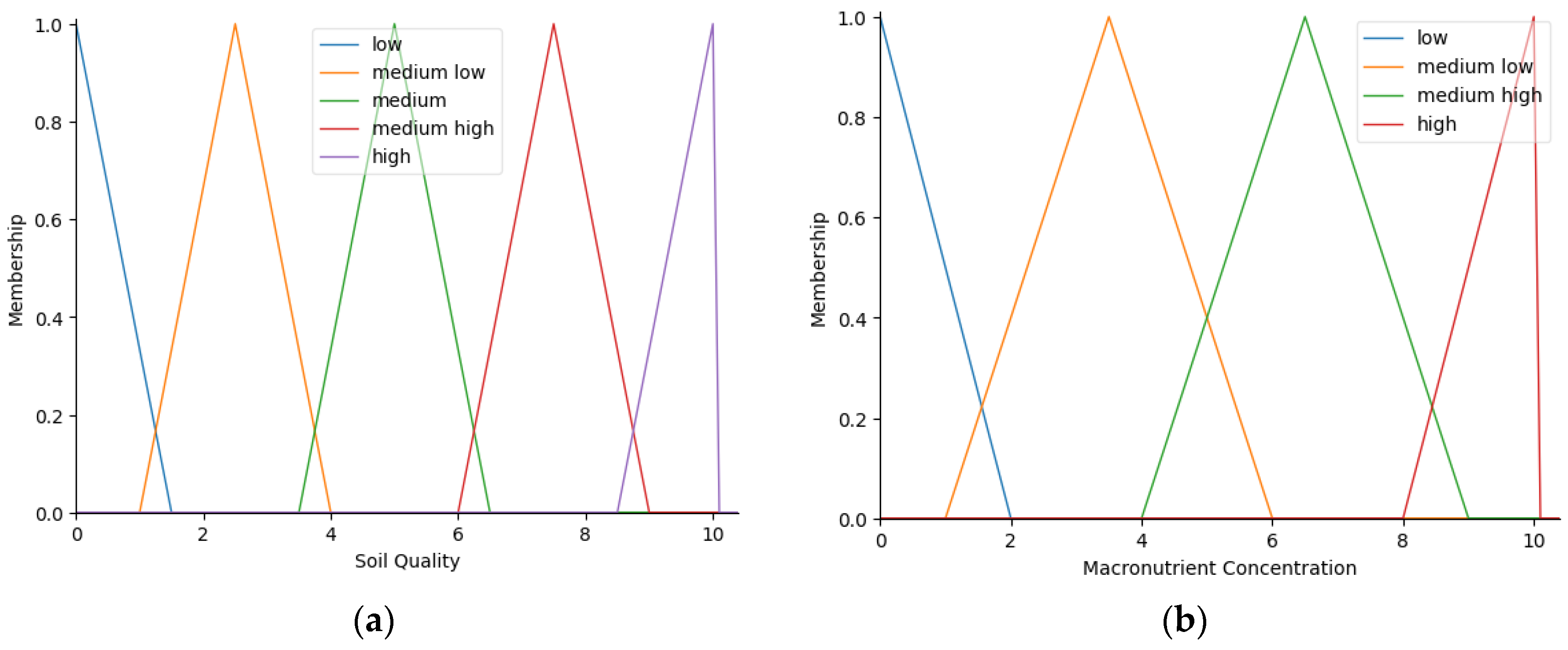

2.3.2. Outputs

2.3.3. Rules

IF pH IS neutral AND temperature IS optimal AND humidity IS optimal AND EC IS low, THEN the PQ IS high.

2.3.4. Implementation of the FLM

3. Results

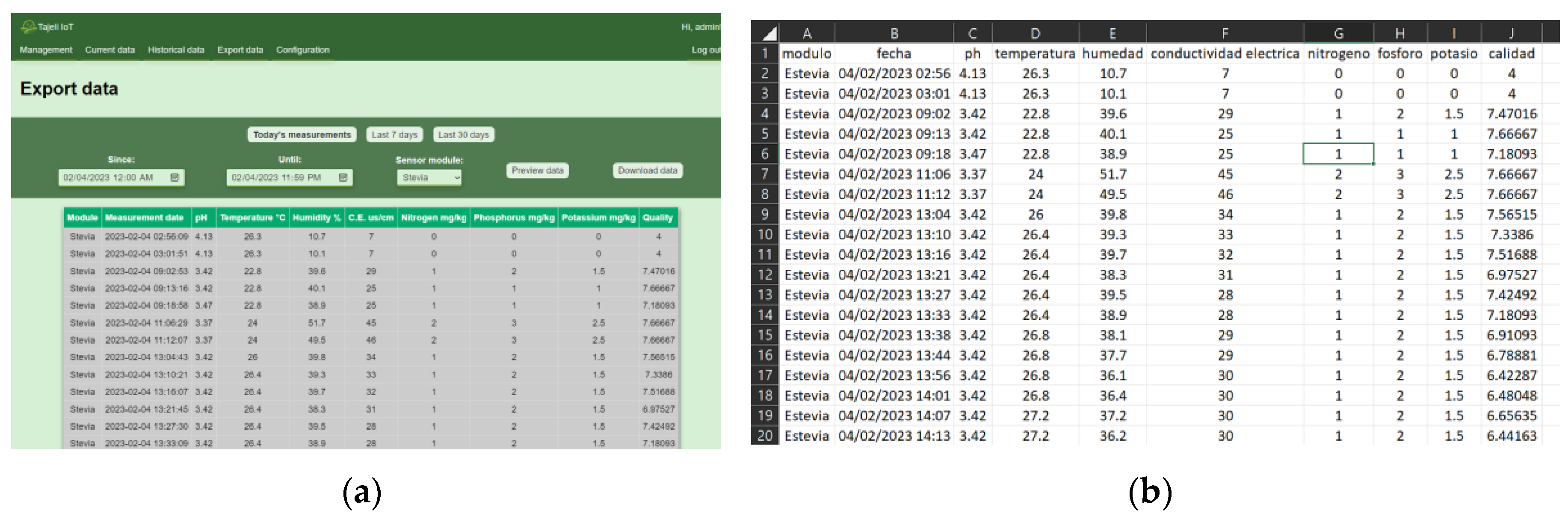

3.1. Web Platform Results

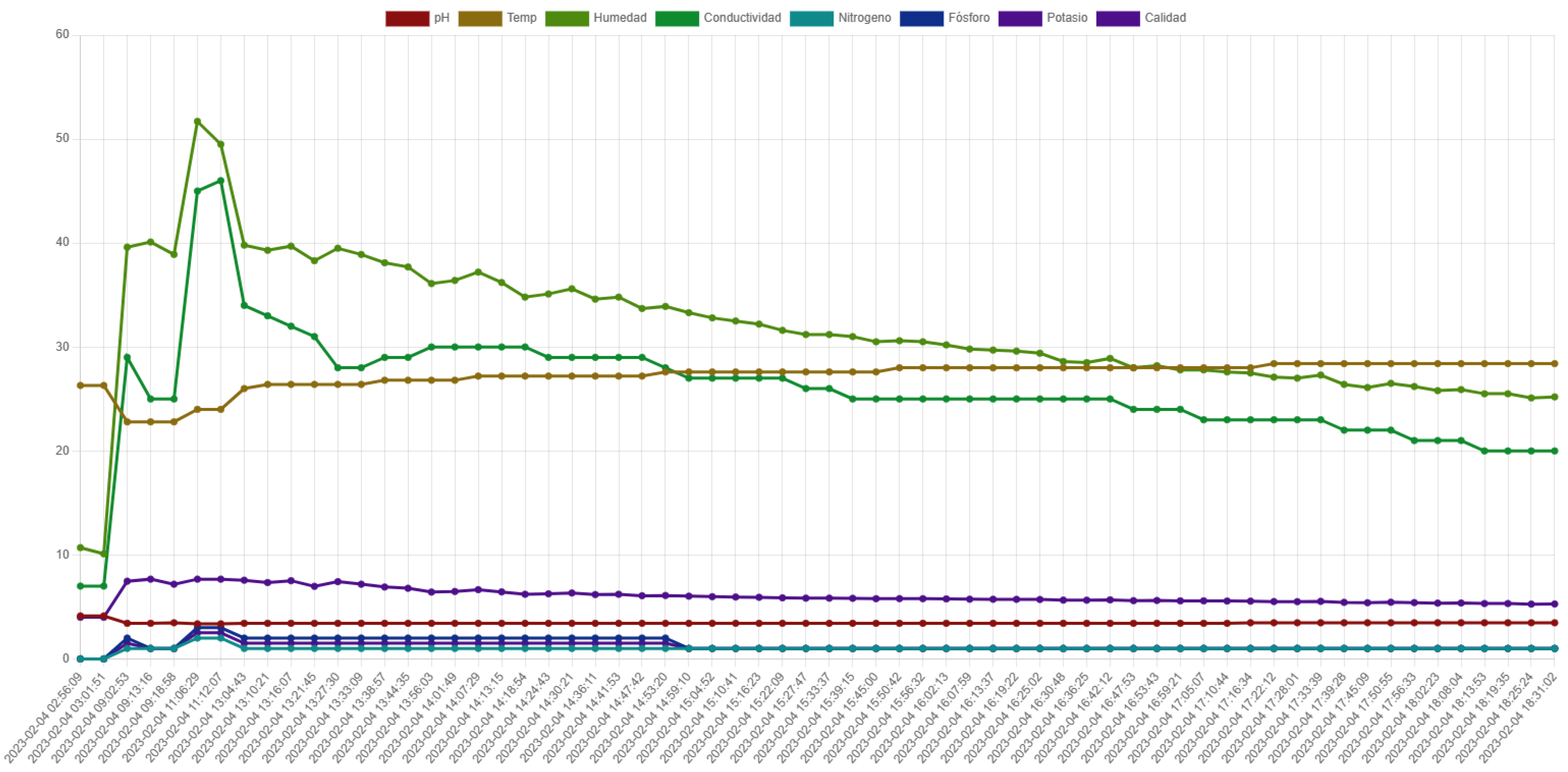

3.2. Wireless Sensor Network Results

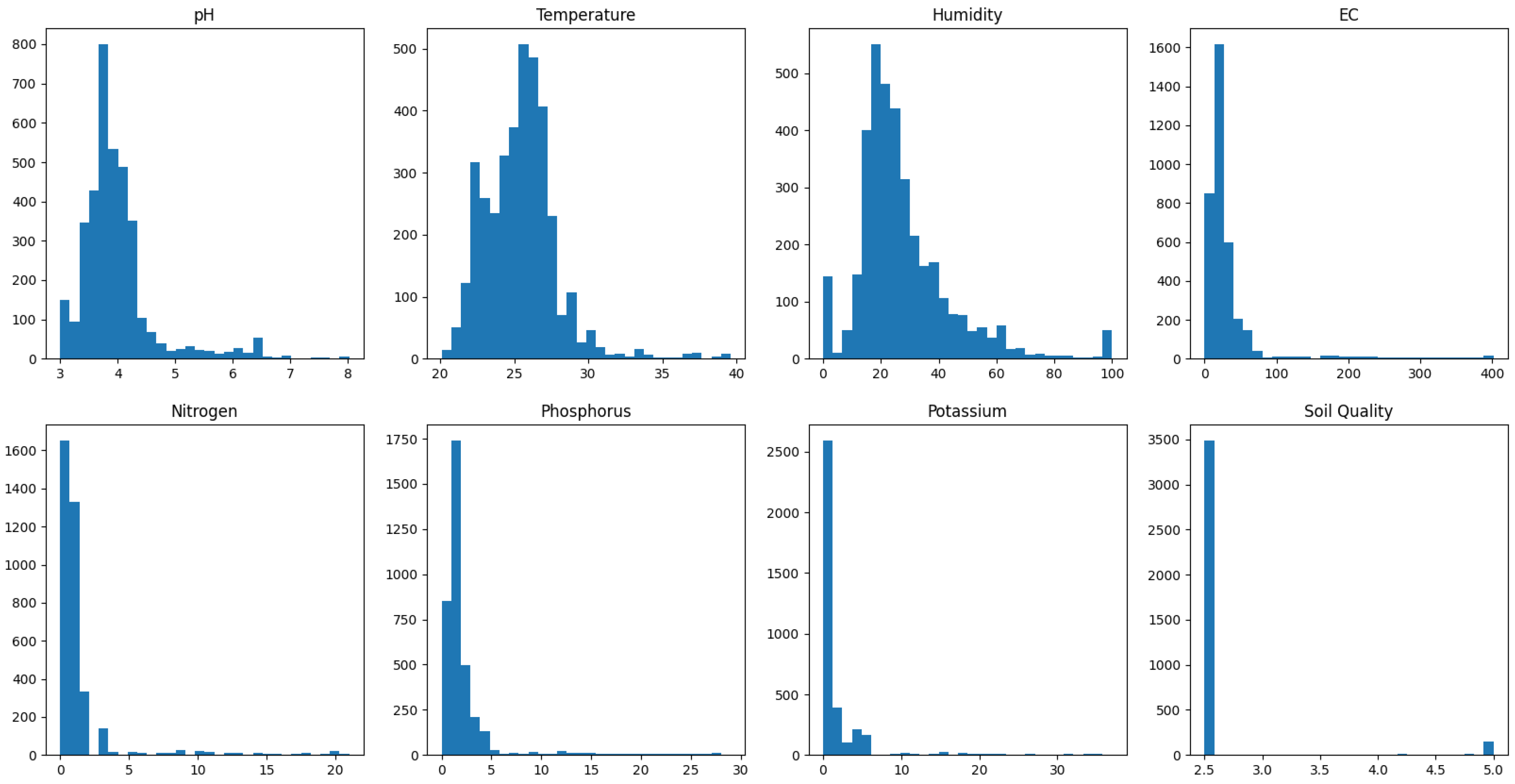

3.3. Collected Data

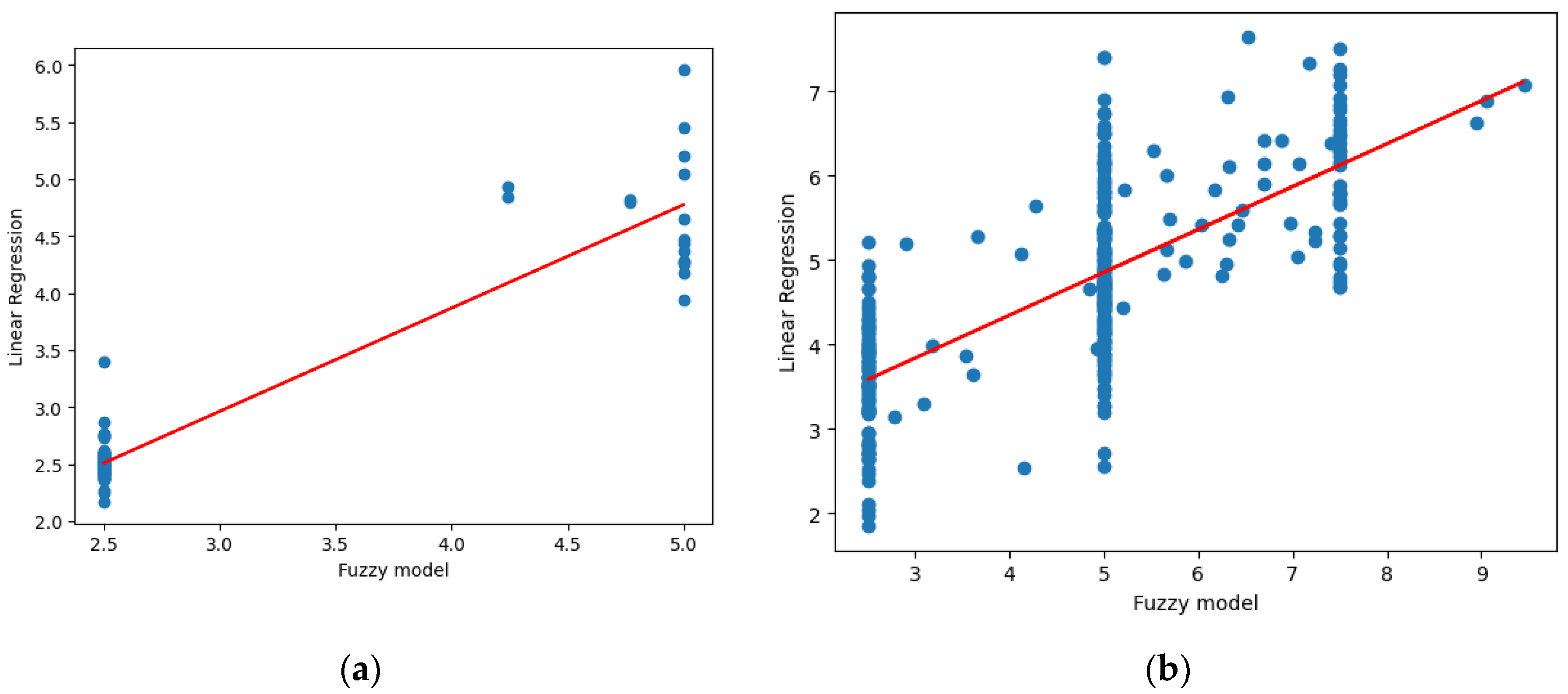

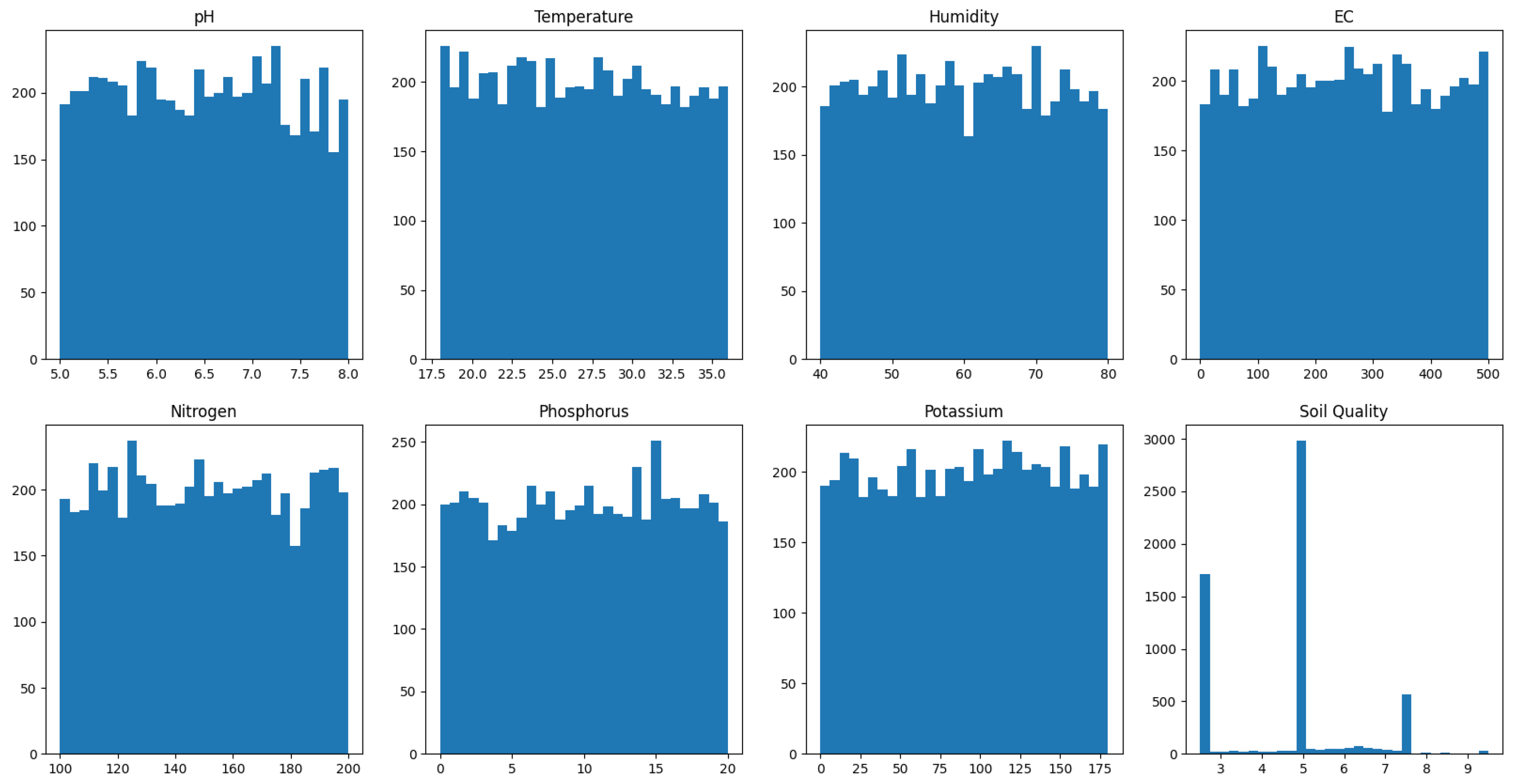

3.4. Fuzzy Model Validation

4. Discussion

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| pH | Temperature | Humidity | EC | Output’s activated MF | Corresponding output |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | low | Physicochemical Quality |

| 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | medium low | |

| 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | medium low | |

| 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | medium low | |

| 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | medium low | |

| 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | medium | |

| 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | medium | |

| 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | medium | |

| 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | medium | |

| 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | medium | |

| 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | medium | |

| 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | medium high | |

| 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | medium high | |

| 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | medium high | |

| 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | medium high | |

| 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | high |

| PQ | MC | Output’s activated MF | Corresponding output |

|---|---|---|---|

| low | low | low | Soil Quality |

| low | medium low | low | |

| low | medium high | medium low | |

| low | high | medium low | |

| medium low | low | medium low | |

| medium low | medium low | medium low | |

| medium low | medium high | medium low | |

| medium | low | medium low | |

| medium high | low | medium low | |

| medium low | high | medium | |

| medium | medium low | medium | |

| medium | medium high | medium | |

| medium | high | medium | |

| medium high | medium low | medium | |

| medium high | medium high | medium high | |

| medium high | high | medium high | |

| high | low | medium high | |

| high | medium low | medium high | |

| high | medium high | high | |

| high | high | high |

References

- Ramírez-Jaramillo, G.; Lozano-Contreras, M.G. LA PRODUCCIÓN DE Stevia Rebaudiana Bertoni EN MÉXICO. AP 2018, 10, 84–90. [Google Scholar]

- Aguilar Marín, S. B., Laitón Jiménez, L. A., Mejía García, F. E., & Felipe Barrera Sánchez, C. F. Desarrollo de un protocolo para el establecimiento in vitro de Stevia rebaudiana variedad Bertoni Morita II. RIAA 2016, 7, 99–106. [CrossRef]

- Leszczynska, T.; Piekło, B.; Kopec, A.; Zimmermann, B.F. Comparative Assessment of the Basic Chemical Composition and Antioxidant Activity of Stevia rebaudiana Bertoni Dried Leaves, Grown in Poland, Paraguay and Brazil—Preliminary Results. Appl. Sci. 2021, 11, 3634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iatridis, N.; Kougioumtzi, A.; Vlataki, K.; Papadaki, S.; Magklara, A. Anti-Cancer Properties of Stevia rebaudiana; More than a Sweetener. Molecules 2022, 27, 1362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stevia Market Size, Share, Trends, Growth, Forecast | Analysis Report, 2022-2030. Available online: https://www.emergenresearch.com/industry-report/stevia-market (accessed on 10/07/2023).

- Stevia Market Size is projected to reach USD 1.40 Billion by 2030, growing at a CAGR of 8.9%: Straits Research. Available online: https://www.globenewswire.com/en/news-release/2022/07/06/2475219/0/en/Stevia-Market-Size-is-projected-to-reach-USD-1-40-Billion-by-2030-growing-at-a-CAGR-of-8-9-Straits-Research.html (accessed on 10/07/2023).

- Le Bihan, Z.; Cosson, P.; Rolin, D.; Schurdi-Levraud, V. Phenological growth stages of stevia (Stevia rebaudiana Bertoni) according to the Biologische Bundesanstalt Bundessortenamt and Chemical Industry (BBCH) scale. A. of App. Biology 2020, 1-13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hirich, E.H.; Bouizgarne, B.; Zouahri, A.; Ibn Halima, O.; Azim, K. How Does Compost Amendment Affect Stevia Yield and Soil Fertility? Environ. Sci. Proc. 2022, 16, 46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Youssef, M. A.; Yousef, A. F.; Ali, M. M.; Ahmed, A. I.; Lamlom, S. F.; Strobel, W. R.; Kalaji, H. M. Exogenously applied nitrogenous fertilizers and effective microorganisms improve plant growth of stevia (Stevia rebaudiana Bertoni) and soil fertility. AMB Express 2021, 11(1), 133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tatli, S.; Mirzaee-Ghaleh, E.; Rabbani, H.; Karami, H.; Wilson, A.D. Prediction of Residual NPK Levels in Crop Fruits by Electronic-Nose VOC Analysis following Application of Multiple Fertilizer Rates. Appl. Sci. 2022, 12, 11263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chatziantoniou, A.; Papandroulakis, N.; Stavrakidis-Zachou, O.; Spondylidis, S.; Taskaris, S.; Topouzelis, K. Aquasafe: A Remote Sensing, Web-Based Platform for the Support of Precision Fish Farming. Appl. Sci. 2023, 13, 6122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, M.A.; Gallardo, J.L.; Zuniga, M.D.; Pedraza, M.A.; Carvajal, G.; Jara, N.; Carvajal, R. LoRa Based IoT Platform for Remote Monitoring of Large-Scale Agriculture Farms in Chile. Sensors 2022, 22, 2824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fathy, C.; Ali, H.M. A Secure IoT-Based Irrigation System for Precision Agriculture Using the Expeditious Cipher. Sensors 2023, 23, 2091. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Miao, H. Y.; Yang, C. T.; Kristiani, E.; Fathoni, H.; Lin, Y. S.; Chen, C. Y. On Construction of a Campus Outdoor Air and Water Quality Monitoring System Using LoRaWAN. Appl. Sci. 2022, 12, 5018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rokade, A.; Singh, M.; Malik, P.K.; Singh, R.; Alsuwian, T. Intelligent Data Analytics Framework for Precision Farming Using IoT and Regressor Machine Learning Algorithms. Appl. Sci. 2022, 12, 9992. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seyar, M.H.; Ahamed, T. Development of an IoT-Based Precision Irrigation System for Tomato Production from Indoor Seedling Germination to Outdoor Field Production. Appl. Sci. 2023, 13, 5556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsiropoulos, Z.; Gravalos, I.; Skoubris, E.; Poulek, V.; Petrík, T.; Libra, M. A Comparative Analysis between Battery- and Solar-Powered Wireless Sensors for Soil Water Monitoring. Appl. Sci. 2022, 12, 1130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tagarakis, A.C.; Kateris, D.; Berruto, R.; Bochtis, D. Low-Cost Wireless Sensing System for Precision Agriculture Applications in Orchards. Appl. Sci. 2021, 11, 5858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiménez-Buendía, M.; Soto-Valles, F.; Blaya-Ros, P.J.; Toledo-Moreo, A.; Domingo-Miguel, R.; Torres-Sánchez, R. High-Density Wi-Fi Based Sensor Network for Efficient Irrigation Management in Precision Agriculture. Appl. Sci. 2021, 11, 1628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López Rivero, A.J.; Martínez Alayón, C.A.; Ferro, R.; Hernández de la Iglesia, D.; Alonso Secades, V. Network Traffic Modeling in a Wi-Fi System with Intelligent Soil Moisture Sensors (WSN) Using IoT Applications for Potato Crops and ARIMA and SARIMA Time Series. Appl. Sci. 2020, 10, 7702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carucci, F.; Gagliardi, A.; Giuliani, M.M.; Gatta, G. Irrigation Scheduling in Processing Tomato to Save Water: A Smart Approach Combining Plant and Soil Monitoring. Appl. Sci. 2023, 13, 7625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andrade, R.O.; Yoo, S.G. A Comprehensive Study of the Use of LoRa in the Development of Smart Cities. Appl. Sci. 2019, 9, 4753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elfakki, A.O.; Sghaier, S.; Alotaibi, A.A. An Intelligent Tool Based on Fuzzy Logic and a 3D Virtual Learning Environment for Disabled Student Academic Performance Assessment. Appl. Sci. 2023, 13, 4865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hegazi, M.O.; Almaslukh, B.; Siddig, K. A Fuzzy Model for Reasoning and Predicting Student’s Academic Performance. Appl. Sci. 2023, 13, 5140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Yaari, M.; Aldhyani, T.H.H.; Rushd, S. Prediction of Arsenic Removal from Contaminated Water Using Artificial Neural Network Model. Appl. Sci. 2022, 12, 999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moayedi, H.; Tien Bui, D.; Dounis, A.; Ngo, P.T.T. A Novel Application of League Championship Optimization (LCA): Hybridizing Fuzzy Logic for Soil Compression Coefficient Analysis. Appl. Sci. 2020, 10, 67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zadeh, L. A. Fuzzy logic. Computer 1988, 21(4), 83–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, H.; Yang, S. A Trajectory Tracking Control Strategy of 4WIS/4WID Electric Vehicle with Adaptation of Driving Conditions. Appl. Sci. 2019, 9, 168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lambat, Y.; Ayres, N.; Maglaras, L.; Ferrag, M.A. A Mamdani Type Fuzzy Inference System to Calculate Employee Susceptibility to Phishing Attacks. Appl. Sci. 2021, 11, 9083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, H.; You, J.; Wang, Y.; Zhao, X. Offloading Strategy of Multi-Service and Multi-User Edge Computing in Internet of Vehicles. Appl. Sci. 2023, 13, 6079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosales-Manzo, D.; García-Díaz, N.; Ruiz-Tadeo, A.; García-Virgen, J.; Farías-Mendoza, N. Sistema difuso Takagi-Sugeno para predecir el riesgo de propagación de Sigatoka Negra Mycosphaerella fijiensis en el cultivo de plátano. Rev. Inter. de Inv. e Inn. Tec. 2020, 8(44), 12–24. [Google Scholar]

- Chopra, S., Dhiman, G., Sharma, A., Shabaz, M., Shukla, P., & Arora, M. Taxonomy of Adaptive Neuro-Fuzzy Inference System in Modern Engineering Sciences. Comp. Int. and N. 2021, 6455592. [CrossRef]

- JXBS-3001 Soil NPK sensor User Manual. Available online: https://5.imimg.com/data5/SELLER/Doc/2022/6/XB/EU/YX/5551405/soil-sensor-jxbs-3001-npk-rs.pdf (Accessed on 14/05/2023).

- Cardone, B.; Di Martino, F. A Fuzzy Rule-Based GIS Framework to Partition an Urban System Based on Characteristics of Urban Greenery in Relation to the Urban Context. Appl. Sci. 2020, 10, 8781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coutinho, R.M.; Sousa, A.; Santos, F.; Cunha, M. Contactless Soil Moisture Mapping Using Inexpensive Frequency-Modulated Continuous Wave RADAR for Agricultural Purposes. Appl. Sci. 2022, 12, 5471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Hawas, I.A.; Hassan, S.A.; AbdelDayem, H.M. Potential Applications in Relation to the Various Physicochemical Characteristics of Al-Hasa Oasis Clays in Saudi Arabia. Appl. Sci. 2020, 10, 9016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramirez-Builes, V.H.; Küsters, J.; Thiele, E.; Leal-Varon, L.A.; Arteta-Vizcaino, J. Influence of Variable Chloride/Sulfur Doses as Part of Potassium Fertilization on Nitrogen Use Efficiency by Coffee. Plants, 2023, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sadollah, A. Introductory Chapter: Which Membership Function is Appropriate in Fuzzy System? In Fuzzy logic based in optimization methods and control systems and its applications; IntechOpen, 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osorio, N. W. pH del suelo y disponibilidad de nutrientes. MISNV, 2012, 1, 1–4. [Google Scholar]

- Madhumathi, R.; Arumuganathan, T.; Shruthi, R. Soil NPK and Moisture analysis using Wireless Sensor Networks. In Proceedings of the 11th International Conference on Computing, Communication and Networking Technologies (ICCCNT), Bengaluru, India (1-6 July 2020). [Google Scholar]

- Cultivo de Stevia en el Huerto paso a paso: Poda, Riego, Cosecha y más. Available online: https://www.agrohuerto.com/cultivo-de-stevia-en-el-huerto/ (accessed on: 13/03/2023).

- Soriano Soto, M.D. Conductividad eléctrica del suelo, Obj. de ap. Art. Doc., 2018, 1, 1–4. [Google Scholar]

- Stevia. Available online: https://www.gob.mx/cms/uploads/attachment/file/726330/Stevia.pdf (accessed on: 14/03/2023).

- Mauri, P.V.; Parra, L.; Mostaza-Colado, D.; Garcia, L.; Lloret, J.; Marin, J.F. The Combined Use of Remote Sensing and Wireless Sensor Network to Estimate Soil Moisture in Golf Course. Appl. Sci. 2021, 11, 11769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Vos, B.; Cools, N.; Verstraeten, A.; Neirynck, J. Accurate Measurements of Forest Soil Water Content Using FDR Sensors Require Empirical In Situ (Re)Calibration. Appl. Sci. 2021, 11, 11620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chicco, D.; Warrens, M. J.; Jurman, G. The coefficient of determination R-squared is more informative than SMAPE, MAE, MAPE, MSE and RMSE in regression analysis evaluation. P. Com. Sci. 2021, 7, e623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Humphrey, W. S. A Discipline for Software Engineering. Addison-Wesley Professional. 1995. ISBN: 978-0201546101.

| Soil parameter | Universe of Disclosure | Linguistic term | Parameter unit | MF type | MF Parameters | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| a | b | c | d | |||||

| pH | extra acidic | - | Trapezoidal | 0 | 0 | 4.9 | 5.1 | |

| very acidic | Trapezoidal | 4.9 | 5.1 | 5.4 | 5.6 | |||

| moderately acidic | Trapezoidal | 5.4 | 5.6 | 5.9 | 6.1 | |||

| 0 - 14 | slightly acidic | Trapezoidal | 5.9 | 6.1 | 6.4 | 6.6 | ||

| neutral | Trapezoidal | 6.4 | 6.6 | 7.2 | 7.4 | |||

| alkaline | Trapezoidal | 7.2 | 7.4 | 7.9 | 8.1 | |||

| very alkaline | Trapezoidal | 7.9 | 8.1 | 14 | 14 | |||

| Temperature | cold | °C | Trapezoidal | 0 | 0 | 15 | 20 | |

| 0 - 50 | optimal | Trapezoidal | 15 | 20 | 25 | 30 | ||

| hot | Trapezoidal | 25 | 30 | 50 | 50 | |||

| Humidity | dry | % | Trapezoidal | 0 | 0 | 65 | 75 | |

| 0 - 100 | optimal | Trapezoidal | 65 | 75 | 85 | 95 | ||

| wet | Trapezoidal | 85 | 95 | 100 | 100 | |||

| Electric Conductivity | low | uS/cm | Trapezoidal | 0 | 0 | 450 | 550 | |

| 0 - 1500 | medium | Trapezoidal | 450 | 550 | 950 | 1050 | ||

| high | Trapezoidal | 950 | 1050 | 1500 | 1500 | |||

| Nitrogen | low | mg/kg | Trapezoidal | 0 | 0 | 106.6 | 126.6 | |

| 0 - 300 | medium | Trapezoidal | 106.6 | 126.6 | 177.5 | 197.5 | ||

| high | Trapezoidal | 177.5 | 197.5 | 300 | 300 | |||

| Phosphorus | low | mg/kg | Trapezoidal | 0 | 0 | 4.2 | 4.8 | |

| 0 - 20 | medium | Trapezoidal | 4.2 | 4.8 | 8.8 | 9.4 | ||

| high | Trapezoidal | 8.8 | 9.4 | 20 | 20 | |||

| Potassium | low | mg/kg | Trapezoidal | 0 | 0 | 44.1 | 54.1 | |

| 0 - 180 | medium | Trapezoidal | 44.1 | 54.1 | 111.6 | 121.6 | ||

| high | Trapezoidal | 111.6 | 121.6 | 180 | 180 | |||

| Output name | Universe of Disclosure | Linguistic term | MF type | MF Parameters | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| a | b | c | ||||

| Soil Quality | low | Triangular | 0 | 0 | 1.5 | |

| medium low | Triangular | 1 | 2.5 | 4 | ||

| 0 – 10 | medium | Triangular | 3.5 | 5 | 6.5 | |

| medium high | Triangular | 6 | 7.5 | 9 | ||

| high | Triangular | 8.5 | 10 | 10 | ||

| Macronutrient Concentration | low | Triangular | 0 | 0 | 2 | |

| 0 – 10 | medium low | Triangular | 1 | 3.5 | 6 | |

| medium high | Triangular | 4 | 6.5 | 9 | ||

| high | Triangular | 8 | 10 | 10 | ||

| Physicochemical Quality | low | Triangular | 0 | 0 | 1.5 | |

| medium low | Triangular | 1 | 2.5 | 4 | ||

| 0 -10 | medium | Triangular | 3.5 | 5 | 6.5 | |

| medium high | Triangular | 6 | 7.5 | 9 | ||

| high | Triangular | 8.5 | 10 | 10 | ||

| Nitrogen | Phosphorus | Potassium | Output’s activated MF | Corresponding output |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 0 | 0 | low | Macronutrient Concentration |

| 0 | 0 | 1 | medium low | |

| 0 | 1 | 0 | medium low | |

| 1 | 0 | 0 | medium low | |

| 0 | 1 | 1 | medium high | |

| 1 | 0 | 1 | medium high | |

| 1 | 1 | 0 | medium high | |

| 1 | 1 | 1 | high |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).