3.2.2. Rhythm and Rhyme Violations

In poetry, poetic devices play a fundamental role, in particular in the tradition of the sonnets in Elizabethan times. Sonnets in their Elizabethan variety, had a stringent architecture which required the reciter to organize the presentation according to logical structure in the stanza structure, on the one side – introducing the main theme, expanding and developing the accompanying subthemes, exploring consequences, finding some remedies to solve the dilemma or save the protagonist. On the other side, the line by line structure required the reciter to respect the alternate rhyming patterns which were usually safeguarded by end-stopped lines. Thus, the audience expectations were strongly influenced by any variation related to rhyming and rhythm as represented by the sequence of breath groups and intonational groups. Whenever the rhyming pattern introduced a new unexpected pronunciation – not in other contexts – of a rhyming word, the audience was stunned: say a common word like love was pronounced to rhyme with prove. The same effect must have been produced with enjambments, whenever lines had to run-on because meaning required the syntactic structure to be reconstructed – as for instance in lines ending in a head noun which had its prepositional-of modifier in the beginning of the following line. Breath groups and intonational groups had to be recast to suit the unexpected variation, but rhyming had to be preserved. We will explore these aspects of the sonnets thoroughly in this section.

In a previous paper [

23] we discussed the problem of (pseudo) rhyme violations as it has been presented in the literature on Shakespeare. In particular we referred to the presence of more than 100 apparent rhyme violations, that is rhyming end of line words which according to current pronunciation do not allow the rhyming scheme of the stanza to succeed, but it did in the uncertain grammar of Early Modern English. For instance, in sonnet 1 we find two lines 2-4, with the stanza rhyme scheme ABAB, ending with the words die-memory. In this case, the second word

memory should undergo a phonological transformation and be pronounced “memo’ry”[

memoray] ending in a diphthong at the end and sounding like “die”/[

dye]. This theme has been discussed and reported in many papers and also on a website -

http://originalpronunciation.com/ - by linguist David Crystal. In particular he collects and comments rhyming words whose pronunciation is different from Modern RP English pronunciation listing more than 130 such cases in the Sonnets. However, he does not provide a rigorous proposal to cope with the problem of rhyme violation, and the list of transformations contains many mistakes when compared with the full transcription of the sonnets published in [

24]. The solution is lexical as we showed in a number of papers[

22,

23], i.e. variations should be listed in a specific lexicon of violations and the choice determined by an algorithm. Here below an excerpt of the table, where we indicated the number of the sonnet, the line number, the rhyming word pair, their normal phonetic transcription using ARPAbet and in the last column the adjustment provided by the lexicon as shown here below.

Table 6.

Example of lexical treatment of rhyme violation.

Table 6.

Example of lexical treatment of rhyme violation.

| Sonnet No. |

Line

No. |

Rhyme

violation |

Arpabet

phoneme |

Adjusted

phoneme |

| Sonnet 1 |

2-4 |

die-memory |

d_ay-m_eh1_m_er_iy |

iyay |

Variants are computed by an algorithm that takes as input the rhyming word and its stressed vowel from the first line in a rhyming pair and compares it with the rhyming word and vowel of the alternate line

3. In case of failure, the lexicon of Elizabethan variants is searched. The same stressed vowel may undergo a number of different transformations so it is the lexicon that drives the change, and it is impossible to establish phonological rules at feature level. Some words may be pronounced in two manners according to rhyming constraints, thus it is the rhyming algorithm that will decide what to do with the lexicon of variants. The lexicon in our case has not been built manually but automatically, by taking into account all rhyming violations and transcribing the pair of word at line end on a file. The algorithm searches couples of words in alternate lines inside the same stanza and in sequence when in the couplet, and whenever the rhyme is not respected it writes the pair in output. Take for instance the pair LOVE/PROVE, in that order in alternate lines within the same stanza: in this case it is the first word that has to be pronounced like the second. The order is decided by the lexicon: LOVE is included in the lexicon with the rule for its transformation, PROVE is not. In some other cases it is the second word that is modified by the first one, as in CRY/JOLLITY, again the criterion for one vs the other choice is determined by the lexicon.

In the table below, we list the total number of violations we found subdividing them by 5 phases as we did before, in order to verify whether the conventions dictated by Early Modern English grammars of the time did eventually impose a standard in the last period, beginning of XVIIth century. After Total we indicate the total number of violations found followed by slash and the number of sonnets. The ratio gives a weighted number that can be used to compare different occurrences in the five phases. As can be noted, the highest number of violations are to be found in the first two phases. Then there is a decrease from Phase II to Phase IV which is eventually followed by a slight increase in Phase V which however is lower than what we found in previous phases. The first two phases then have numbers well over the average: the decrease in the following phases testifies to a tendency in Shakespeare’s work to fix pronunciation rules in the sonnets as more and more grammarians tried to document what constituted the rules for Early Modern English.

Table 7.

Number of Rhyme Violations x five Phases.

Table 7.

Number of Rhyme Violations x five Phases.

| |

Sonnets

Interval |

No. Rhyme

Violations /

No. Sonnets |

Ratio

% |

| Phase I |

1-17 |

22 / 17 |

1.2941 |

| Phase II |

18-51 |

40 / 34 |

1.1765 |

| Phase III |

52-96 |

34 / 45 |

0.7556 |

| Phase IV |

97-126 |

18 / 30 |

0.6 |

| Phase V |

127-154 |

23 / 28 |

0.8214 |

| Total |

|

137 / 154 |

0.8896 |

We call these (pseudo) rhyming violations because current reciters available on Youtube don’t dare use the old pronunciation required and produce a rhyming violation by using Modern English pronunciation. One of these reciter is the famous actor John Gilgoud, who when reading Sonnet 66 correctly pronounces DESERT with its original meaning, but then in Sonnet 116 produces three violations when rhyming pairs required transformations that were clearly mandatory in Early Modern English, and they are: |love| to be pronounced with the vowel of |remove| in lines 2/4, |come| to be pronunced with the vowel of |doom| in lines 10/12, and |loved| to be pronounced with the vowel of |proved| in the couplet. How do we know that these words should be pronounced in that manner and not in the opposite way – say |remove| as |love|, |doom| as |come| and |proved| as |loved| as is being asserted by Ben Crystal son of David. There are three criteria that determine the way in which words should rhyme: first one is the rhyming constraints which were so stringent at the time owing to the fact that poetry was only recited and not read on books. Ok, then, there are rhyming constraints but how do they work, in which direction? The direction is determined by two factors: the first one is determined by universal phonological principles, as for instance the one the governs phonological variations of vowel sounds – in Vowel Shift of verbs or nouns due to morphological changes - which systematically changed “low” and “mid” features into “high” features and not viceversa

1. The other factor is simply lexical: i.e. not all words will be subject to a transformation in that period: as a result some words had double pronunciation. This was extensively documented in books and articles published at the time and written by famous poets like Ben Jonson and a great number of grammarians of the XVI and XVII century. All this information are made available by the famous historical phonologist Wilhelm Vietor of the XIX century in a book published at first in 1889

4, by the title “A Shakespeare Phonology” which we have adopted as our reference. Variants are then lexically determined. Some words involved in the transformation are listed below using Arpabet as phonetic alphabet in the excerpt taken from the lexicon. As can be easily noticed, variants are related also to stress position, but also to consonant sounds.

Lexicon 1.

shks(despised,d_ih2_s_p_ay1_s_t,ay1,ay1)

shks(dignity,d_ih2_g_n_ah_t_iy1,iy1,ay1).

shks(gravity,g_r_ae2_v_ah_t_iy1,iy1,ay1).

shks(history,hh_ih2_s_t_er_iy1,iy1,ay1).

shks(injuries,ih2_n_jh_er_iy1_z,iy1,iy1).

shks(jealousy,jh_eh2_l_ah_s_iy1,iy1,ay1).

shks(jollity,jh_aa2_l_t_iy1,iy1,ay1).

shks(majesty,m_ae2_jh_ah_s_t_iy1,iy1,ay1).

shks(memory,m_eh2_m_er_iy1,iy1,ay1).

shks(nothing,n_ah1_t_ih_ng,ah1,ow1).

It is now clear that variants need to interact with information coming from the rhyming algorithm that alone can judge whether the given word, usually at line end - but the word can also be elsewhere -, has to undergo the transformation or not. The lexicon in our case has not been built manually but automatically, by taking into account all rhyming violations and transcribing the pair of word at line end on a file. The algorithm searches couple of words in alternate lines inside the same stanza and whenever the rhyme is not respected it writes the pair in output. Take for instance the pair LOVE/PROVE, in that order in alternate lines within the same stanza: in this case it is the first word that has to be pronounced like the second. The order is decided by the lexicon: LOVE is included in the lexicon with the rule for its transformation, PROVE is not. In some other cases it is the second word that is modified by the first one, as in CRY/JOLLITY, again the criterion for one vs the other choice is determined by the lexicon. Thus the system SPARSAR has a lexicon of possible transformations which are checked by an algorithm that whenever a violation is found, it is searched for the word to be modified and alters the phonetic description. In case both words of the rhyming pair are in the lexicon, the type of variation to be selected is determined by the overall sound map of the sonnet: Shakespeare produced a careful sound harmony in the choice of rhyming pairs including four or at least three sound classes.

3.2.2.1. Commenting on David Crystal’s resources

David Crystal makes available on his website the full phonetic transcription of the sonnets. However, as said above, this transcriptions contain many mistakes. There are two vague explanations Crystal finds to support his transcriptions in his OP (Old Pronunciation) and the first is a tautology: the “pronunciation system has changed since the 16th century”: this is what he calls “a phonological perspective” (ibid.:298). In section 2. entitled “Phonological rhymes” he writes:

“Far more plausible is to take on board a phonological perspective, recognizing that the reason for rhymes fail to work today is because the pronunciation system has changed since the 16th century. …. a novel and illuminating auditory experience, and introduced audiences to rhymes and puns which modern English totally obscures. The same happens when the sonnets are rendered in OP. In sonnet 154, the vowel of “warmed” echoes that of “disarmed”, “remedy” echoes “by”, the final syllable of “perpetual” is stressed and rhymes with “thrall”, and the vowel of “prove” is short and rhymes with “love”.

And further on (ibid:299):

“Ben Jonson… wrote an “English Grammar” in which he gives details about how letters should be pronounced. How do we know that “prove” rhymed with “love”? This is what he says about letter “O” in Chapter 4: “It naturally soundeth…..In the short time more flat, and akind to “u;” as “cosen”, “dosen”, “mother”, “brother”, “love”, “prove” “. And in another section, he brings together “love, glove” and “move”. This is not to deny, of course, that other pronunciations existed at the time…. “Love” may actually have had a long vowel in some regional dialects, as suggested by John Hard (a Devonshire man) in 1570 ( and think of the lengthening we sometimes hear from singers today, who croon “I lurve you”). But the overriding impression from the orthoepists is that the vowel in “love” was short. It is an important point, because this word alone affects the reading of 19 sonnets….”

The second one, is the need to respect puns (ibid. 298) which work in OP but not in modern English; and finally the idiosyncratic spellings in the First Folio and Quarto and the description of contemporary orthoepists, who often give real detail about how pronunciations were in those days. No phonological rules, not even a uniform criterion that underlies the variations. The first reason was expressed as follows at the beginning of the paper: “The pronunciation of certain words has changed between Early Modern English and today, so that these lines (referring to sonnet 154 lines) would have rhymed in Shakespeare’s time. The list of pronunciation variations in the Appendix of his paper [

25] is messy and confusing but what is more important it also contains many mistakes, and we will comment on the first 10 items below.

First of all, the new rhyming transformation of “loved” is not mentioned in the Appendix where according to Crystal “a complete” list should have appeared (ibid.:299). But the most disturbing fact is the recital performed by Ben Crystal (his son and actor in the Globe Theater), which is corageously made publicly available on Youtube (at

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=gPlpphT7n9s). We are given a reading of Sonnet 116 which is illuminating of the type of OP Crystal is talking about. (see time point 6:12 of total 10:21). The reading in fact does not start there but further on in the last stanza. The first contradictory assertion is just here, in the first stanza where lines B should rhyme and LOVE should be made to rhyme with REMOVE (as it is suggested in the Appendix). The question is that in sonnet 154, the same rhyming pair in the same order LOVE—>REMOVE, is transcribed with the opposite pronunciation. In the same paper he asserts that “the vowel of PROVE is short and rhymes with LOVE” (ibid.:298) referring to the couplet of Sonnet 154 which we assume should be also applied to the B rhyming pair in sonnet 116 and not give us lav/rimav, but rather luv/rimuv. Here an important additional series of alliteration would be fired if we adopt this pronunciation which in fact is the rule all over the Sonnets: TRUE would rhyme with LOVE and REMOVE/R. But also further on as we will see LOVE will rhyme with FOOL and DOOM.

p.296:

Let me not to the marriage of true minds

Admit impediments, love is not love

Which alters when it alteration finds,

Or bends with the remover to remove.

The recital starts in third stanza, continuing with the couplet.

Love's not Time's fool, though rosy lips and cheeks

Within his bending sickle's compass come;

Love alters not with his brief hours and weeks,

But bears it out even to the edge of doom:

If this be error and upon me proved,

I never writ, nor no man ever loved.

In the Appendix, we find another mistake or contradiction, where Crystal wrongly transcribes “doom” to rhyme with “come” (came/dam) rather than the opposite (cum/dum) and “loved” to rhyme with “proved” (pravd/lavd) which again should be the opposite, (pruvd/luvd). Here as elsewhere, for instance in Sonnet 55, DOOM rhymes with ROOM in the correct order, ROOM/DOOM, and with the correct sound. Again let’s consider Crystal’s wrongly reporting in the Appendix the rhyming pair LOVE/APPROVE as rhyming in the opposite manner, i.e. LOVE is being pronounced as APPROVE which is just the contrary in the transcription, APPROVE is being pronounced as LOVE with a short open-mid back sounds

5. It is important to note that the first element in most cases appears as SECOND rhyming word in the pair, but in some other cases as first word of the pair. But then we find a long list of mistakes if we compare the expected pronunciation encoded in the Appendix with the complete transcription of the sonnets made available by David Crystal in a pdf file in the same website, where results are turned upside down. For instance LOVED = PROVED (116) has been implicitly turned into PROVED = LOVED, that is the transcription of the stressed vowel of “proved” is the same as the one of “loved” and not the opposite. More mistakes in the list can be found where words like TOMB and DOOM are wrongly listed in the opposite manner. In particular DOOM is made to rhyme with the vowel of COME and not the opposite; also TOMB is made to rhyme with COME and DUMB reverting in both cases the order of the rhyming pair and of the transformation. The phonetic transcription file confirms the mistakes: in the related sonnets we find the same short mid-front vowel instead of a short U. dumb/tomb both in sonnet 83 and 101. In all of these cases, the head (the rhyming word of the first line) should be made to rhyme with the dependent (the rhyming word of the second line) as it happens in Sonnet 1 with MEMORY/DIE and in the great majority of cases. So two elements must be taken into account: the order of the two words of the rhyming pair and then the commanding word, i.e. the word that governs the transformation. In the case of MEMORY/DIE, DIE is the head or the commanding word of the transformation, and comes first in the stanza; whereas MEMORY is the dependent word and comes as second line of the rhyming pair. We list below only the wrong cases and comment the type of mistake made: i.e. either as reverted order - the first element of the pair comes before and it should be read as second; reverted order, the first element is in fact the one deciding the type of vowel to be used; else the order is correct, but the pronunciation chosen is wrong. To comment on the wrong pronunciation required by the rhyme we use sometimes the pronunciation indicated by Vietor in his book, and the phonetic transcription of all the sonnets Crystal made in his pdf file

6.

There are more mistakes in the Appendix as discussed above. We solved the problem by creating a lexicon of phonetic transformations and an algorithm that looked at first for a match in the rhyming word pair positioned in alternate lines if in stanza, and in a sequence if in couplet. In case there was no match, the algorithm looks up the second word in the lexicon, and then the first word and chooses the one that is present. In case both are present in the lexicon, the decision is taken according to position of the rhyming pair in the sonnet with respect to previous rhymes.

3.2.3. Rhyming Constraints and Rhyme Repetition Rate

If on the one side we have rhyme apparent violations using the EME pronunciation to suit the rhyme scheme of the sonnet, on the other side the Sonnets show a high “Repetition Rate” as computed on the basis of rhyming words alone. Due to the requirements imposed by the Elizabethan sonnet rhyme scheme, violations are very frequent, but they are not sufficient to allow the poet with the needed quantity of rhyming words. For this reason it can be surmised Shakespeare was obliged to use a noticeable amount of identical rhyming word pairs. The level of rhyming repetition is in fact fairly high in the sonnets if compared with other poets of the same period, as can be gathered from the tables below. This topic has not gone unnoticed, as for instance in [

30], who indicates repetition of rhyming words as occurring in a limited number of consecutive adjacent sonnets, but doesn’t give an overall picture of the phenomenon. In fact, as will be clear from the data reported below, the level of rhyming repetition is fairly high and reaches 65% of all rhyming pairs. In [

26] we also find an attempt at listing all sonnets violating rhyme schemes which according to him amount to 25. However as can be easily noticed in the list reported in the Appendix, the number of sonnets violating rhyme scheme is much higher than that.

To enumerate rhyming repetitions we collected all end-of-line words with their phonetic transcription and joined them in alternate or sequential order as required by the sonnet rhyme scheme 1-3, 2-4, 5-7, 6-8, 9-11, 10-12, 13-14 – apart from sonnet 126 with only 12 lines and a scheme in couplets aabbccddeeff, and sonnet 99 with 15 lines. Seven rhyming pairs for a total of 1078, i.e. 154 sonnets multiplied by 14 equal 2156 divided by two – less one 2155. In the tables reported as an Appendix

7, we only consider at first pairs with a frequency occurrence higher than 4, and we group together singular and plural of the same noun, and third person present indicative, d/n past with base form for verbs. We list pairs considering first occurrence as the “head” and following line as the “dependent”. Rhyme may be sometimes determined by rules for rhyme violations as is the case with “eye”. We include under the same heading all morphologically viable word forms as long as word stress is preserved in the same location, as said above, including derivations. We decided to separate highly frequent rhyming heads in order to verify whether less frequent ones really matter in the sense of modifying the overall sound image of the sonnets. For that purpose, we produce a first sound map below, limited to higher frequency rhyming pairs and only in a separate count we consider less frequent ones, i.e. hapax, trislegomena and bislegomena.

In many cases the same pair is repeated in inverted order as for instance “thee/me” and “me/thee”, “heart/part” and “part/heart”, “love/prove” and “prove/love” but also “love/move” and “love/remove” and “approve/love” and “love/approve”, “moan/gone” and “foregone/moan”, “alone/gone” and “gone/alone”, “counterfeit/set” and “unset/counterfeit”, “worth/forth” and “forth/worth”, “elsewhere/near” and “near/there”, etc. “Thee” is made to rhyme with “me”, but also with “melancholy”, “posterity”, “see”. “Eye/s” are made to rhyme with almost identical monosyllabic sounding words like “die”, “lie”, “cries”, “lies”, “spies”; but also with “alchemy”, “gravity”, “history”, “majesty”, “remedy”, which require the conversion of the last syllable into a diphthong /ay/ preceded by the current consonant. Most of the rhyming pairs evoke a semantic or symbolic relation which is asserted or suggested by the context in the surrounding lines of the stanza that contain them. Just consider the pairs listed above where relations are almost explicit. However, as remarked by [

26], rhyme repetition inside the same sonnet may have a different goal: linking lines at the beginning of the sonnet to lines at the end as is the case with sonnet 134 and the rhyme pair “free/me” which reappears in the couple in reversed order. Similar results are suggested by repetition of rhyme pair “heart/part” in sonnet 46.

We did the same count with two other famous poets writing poetry in the same century, Sir Philip Sydney and Edmund Spenser. We wanted to verify whether the high level of rhyming pairs repetition might also apply to other poets writing love sonnets. The results show some remarkable differences in the degree of repetitivity. In

Table 9 repeated rhyming pairs are compared to unique ones or hapax rhyming pairs in three Elizabethan poets. Percentages reported are a ratio of all occurrences of rhyming pairs. In first column types are considered and Sydney overruns Shakespeare and Spenser. When we come to Token repeating rate - i.e. counting all occurrences of each type and summing them up, we still have the same picture. Eventually unique or unrepeated rhyming pairs are higher in Spenser than in Shakespeare and Sydney.

Now let us consider the distribution of rhyming words into the corpus of the sonnets. As to general frequency data, the Sonnets contain a number of tokens equal to 18,283 with 3085 types; so-called Vocabulary Richness that is used to measure the ability of a writer to use different words in a corpus, corresponds to 16.87%, a high value for that time when compared with other poets (see [

27]). Also number of Hapax and Rare Words (indicating the union of Hapax, Dis and TrisLegomena) corresponds to average values for other poets, respectively to 56%, the first type and 79% the second one. If we look at similar data for rhyming words we see that Rare Words cover more than 65% of all as can be gathered from table 9 below:

Table 9.

Rhyme Repetition Word Class-Frequency Distribution for Shakespeare’s Sonnets.

Table 9.

Rhyme Repetition Word Class-Frequency Distribution for Shakespeare’s Sonnets.

X

Typ |

FX

Tok |

Sum

FX |

Sum

FX+X |

% Sum

FX+X |

| 28 |

1 |

28 |

28 |

2.72 |

| 17 |

1 |

17 |

45 |

4.37 |

| 14 |

2 |

28 |

73 |

7.09 |

| 12 |

2 |

24 |

97 |

9.43 |

| 10 |

1 |

10 |

107 |

10.4 |

| 9 |

5 |

45 |

152 |

14.77 |

| 8 |

3 |

24 |

176 |

17.1 |

| 7 |

1 |

7 |

183 |

17.78 |

| 6 |

6 |

36 |

219 |

21.28 |

| 5 |

10 |

50 |

269 |

26.14 |

| 4 |

29 |

116 |

385 |

37.41 |

| 3 |

37 |

111 |

496 |

48.2 |

| 2 |

87 |

174 |

670 |

65.11 |

| 1 |

359 |

359 |

1029 |

100.0 |

We report for each word frequency type in column 1 – there is only one head word (

thee) with frequency 28 -, the corresponding number of tokens in table 9, followed by the sum of tokens, the incremental sum and the corresponding percentage with respect to total corpus. As can be noticed from the last column, where incremental percent of rhyme-pair words corpus coverage is reported, the total of rare words, i.e. type rhyme-pair with frequency of occurrence lower than 4, is 62.59%, a fairly low value if compared to the measure evaluated on simple type/token ratios. If we look at most important English poets as documented in a previous paper [

27] we can see that the average value for Rare words is 77.88%. However, we are here dealing with rhyming words and the comparison may not be so relevant.

3.2.4. The Sound-Sense Harmony visualized in charts

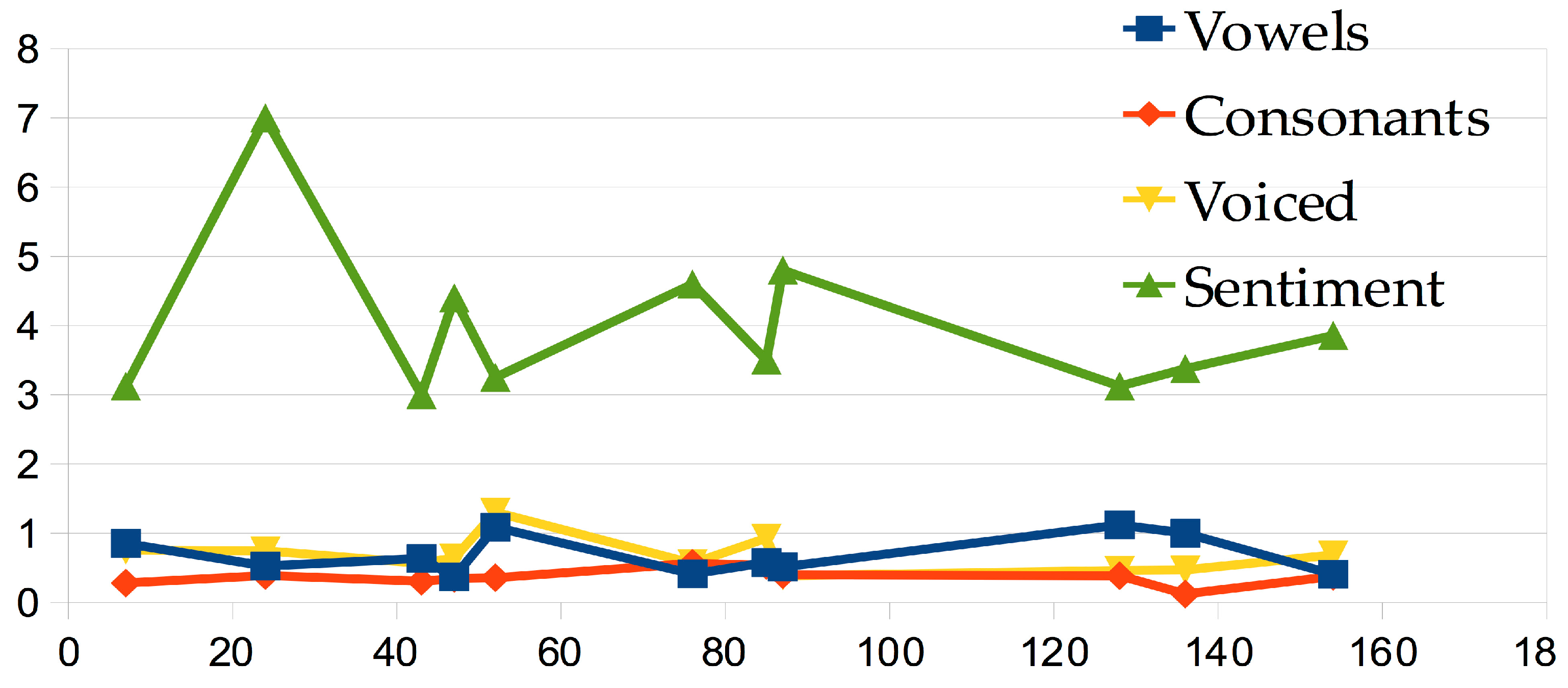

As will appear clearly from the charts below, all the data show a contrasting behaviour which will be attested by correlation values. Where sentiment values increase, the corresponding values for vowels and consonants decrease. To allow better perusing of the trends we split the sonnets into separate tables according to whether their sentiment values are positive or negative. The first chart contains the eleven sonnets which received highest positive sentiment values. All the charts are drawn from the tables of data derived from the analysis files in xml format, which will be made available as supplementary data.

Figure 2.

The eleven most positively marked sonnets: 7, 24, 43, 47, 52, 76, 85, 87, 128, 136, 154.

Figure 2.

The eleven most positively marked sonnets: 7, 24, 43, 47, 52, 76, 85, 87, 128, 136, 154.

As can be easily noticed, all sound data seem to agree showing a trend which is very close for the three variables. On the contrary the sentiment variable has strong peaks and its values are set apart from the sound values. However the interval of variability for sound variables does remain below or close to 1, thus indicating an opposite trend. In particular, consonants are all below 1, vowels oscillate in three cases – 52, 128, 136, voiced in two cases – 52, 85 in this case still below 1 but very close 93% in favour of unvoiced.

We interpret consistently contrasting values as a way to convey ironic, sarcastic and sometimes parodistic meaning. More on this interpretation below. Sonnet 136 is the one highly ambiguous and consequently ironic, celebrating the “Will” or simply “will”. Sonnet 128 is all devoted to music and playing with a wooden instrument which is the target of the ironic vein and the double meaning of words like “tickle”. Finally, sonnet 52 is the celebration of the beloved as a “chest” where the rich keep their treasure, and which must be enjoyed “seldom”. Sonnet 85 is a celebration of silent thought, and for this theme it is filled with consonants which are continuants |h,f,th| and are unvoiced, but many words are marked by a sonorant syllable, thus voiced.

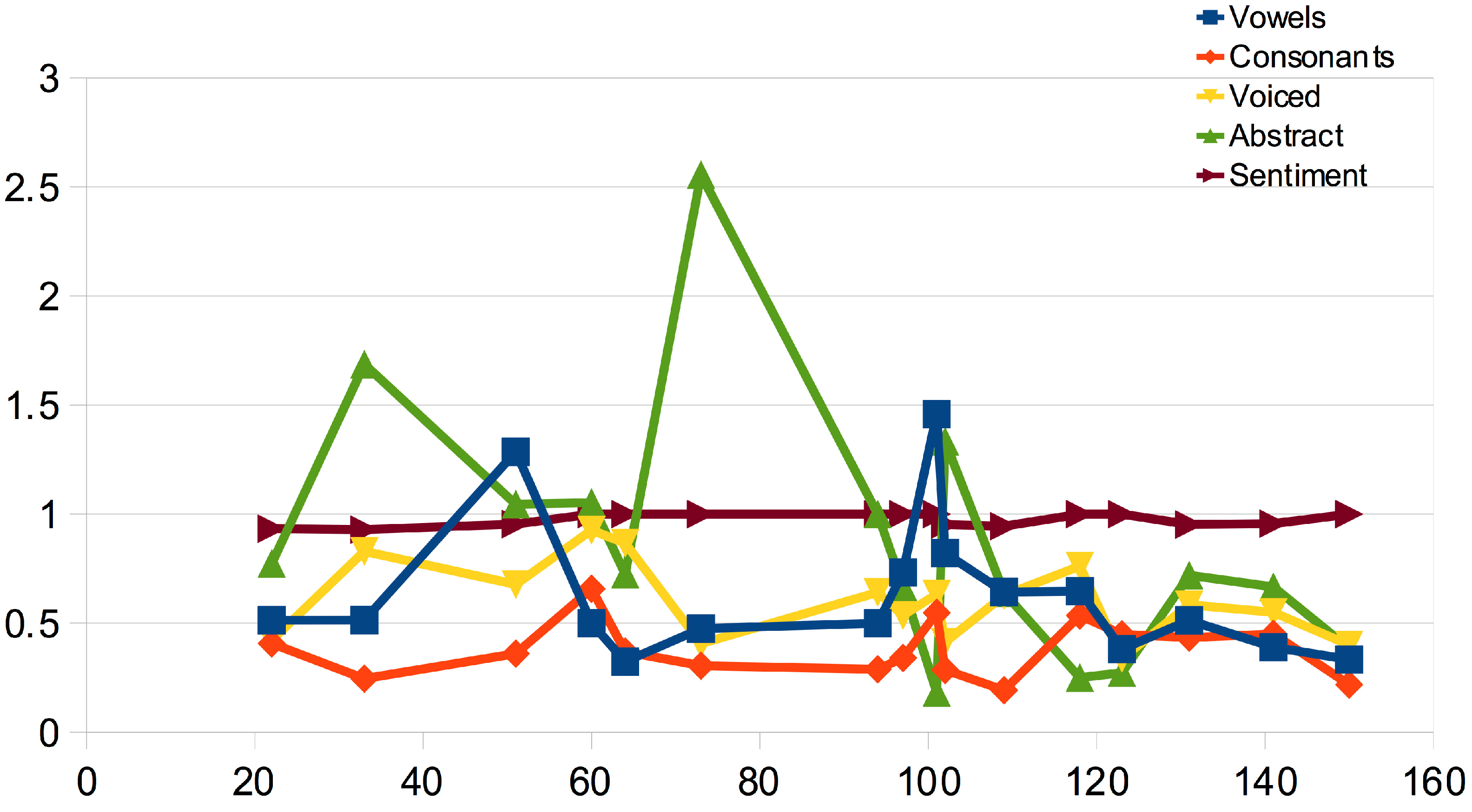

We now separate 16 sonnets which have sentiment equal to 1 or slightly lower than 1 but always higher than 92% in favour of positively marked. They are the following: 22, 33, 51, 60, 64, 73, 94, 97, 101, 102, 109, 118, 123, 131, 141, 150.

Figure 3.

Chart of the 16 borderline sonnets positively marked for sentiment.

Figure 3.

Chart of the 16 borderline sonnets positively marked for sentiment.

In this chart we added the ratio for Abstract/Concrete which shows a peak for sonnet 73. As the chart clearly shows, the line for Sentiment borders 1, as to the remaining variables, Vowels is the one oscillating most after Abstract. Voiced and Consonants are fairly always aligned apart from sonnet 33 and 102. In both sonnets the number of “Obstruents” (|b,d,p,t,k,g|) is very low and real consonants are substituted by “Continuants” (|s,sh,th,f,v,h|) both voiced and unvoiced. In the following analysis for this reason I will only consider Voicing as the relevant variable for consonants and this will show better agreement in the overall data. Now we show charts for all negatively marked sonnets using only three variables.

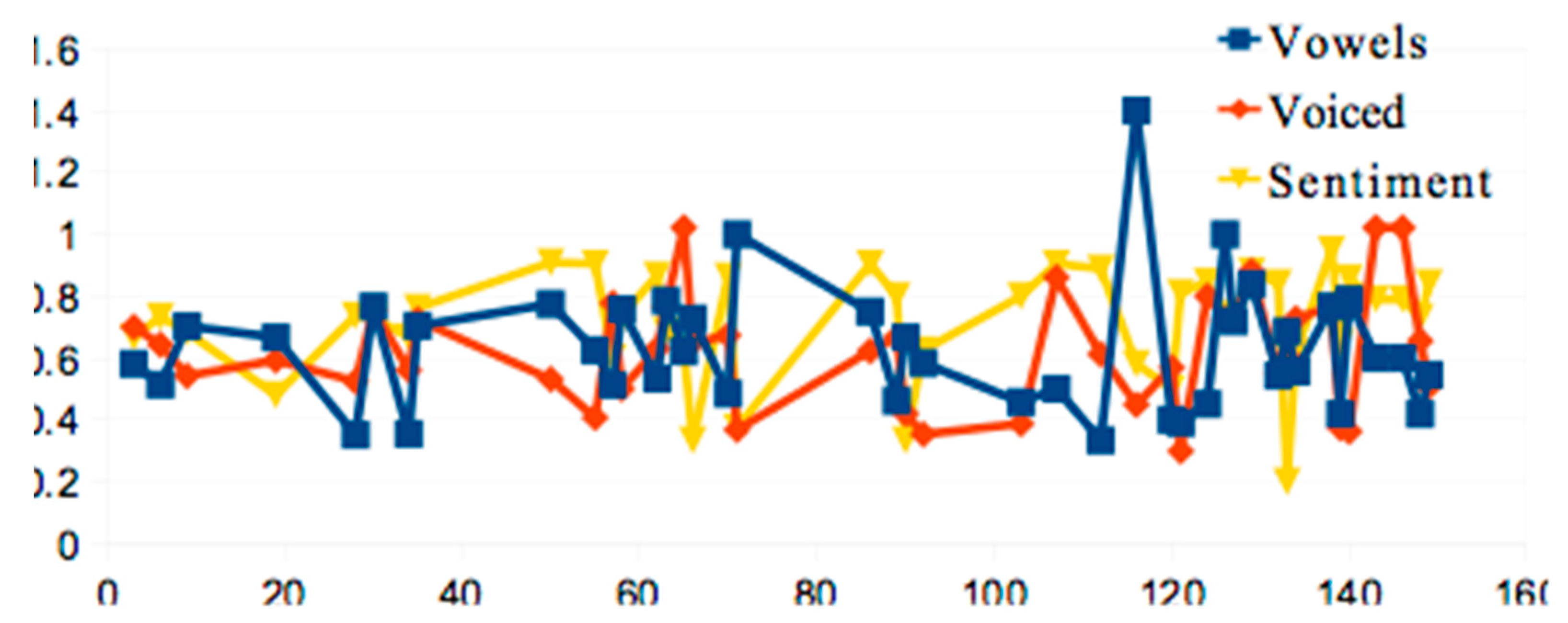

Figure 4.

Chart of the 42 negatively marked sonnets: 3, 8, 9, 19, 28, 30, 34, 35, 50, 55, 57, 58, 60, 62, 63, 65, 66, 71, 86, 89, 92, 103, 107, 112, 116, 120, 121, 124, 126, 127, 129, 132, 133, 134, 138, 139, 140, 143, 146, 148, 149.

Figure 4.

Chart of the 42 negatively marked sonnets: 3, 8, 9, 19, 28, 30, 34, 35, 50, 55, 57, 58, 60, 62, 63, 65, 66, 71, 86, 89, 92, 103, 107, 112, 116, 120, 121, 124, 126, 127, 129, 132, 133, 134, 138, 139, 140, 143, 146, 148, 149.

As can be easily seen, the Sentiment variable is always below 1 but the two remaining variables oscillate up and down, the vowel one oscillating most. In this case, the contrast is even stronger and correlations show a negative trend between Vowels and Sentiment: the one has a decreasing trend while the other has it increasing, apart from a few exceptions, sonnets 30, 35 and 127 which have almost identical values for the three variables. The other correlation between Voicing and Sentiment is positive but very weak, 0.1769. Now we repeat the chart for sonnets positively marked for sentiment and measure the correlation.

Correlation between Vowel and Sentiment is positive but very week; correlation between the Voicing parameter and Sentiment is again negative and very week, -0,0065037. Thus, results for the 42 sonnets negatively marked by sentiment show that we have negative correlation between vowels and voicing, and vowels and sentiment, but positive correlation between voicing and sentiment. So it is just the opposite of what we get with positively marked sonnets. And finally the eleven most positively marked sonnets showing the same contrasting results.

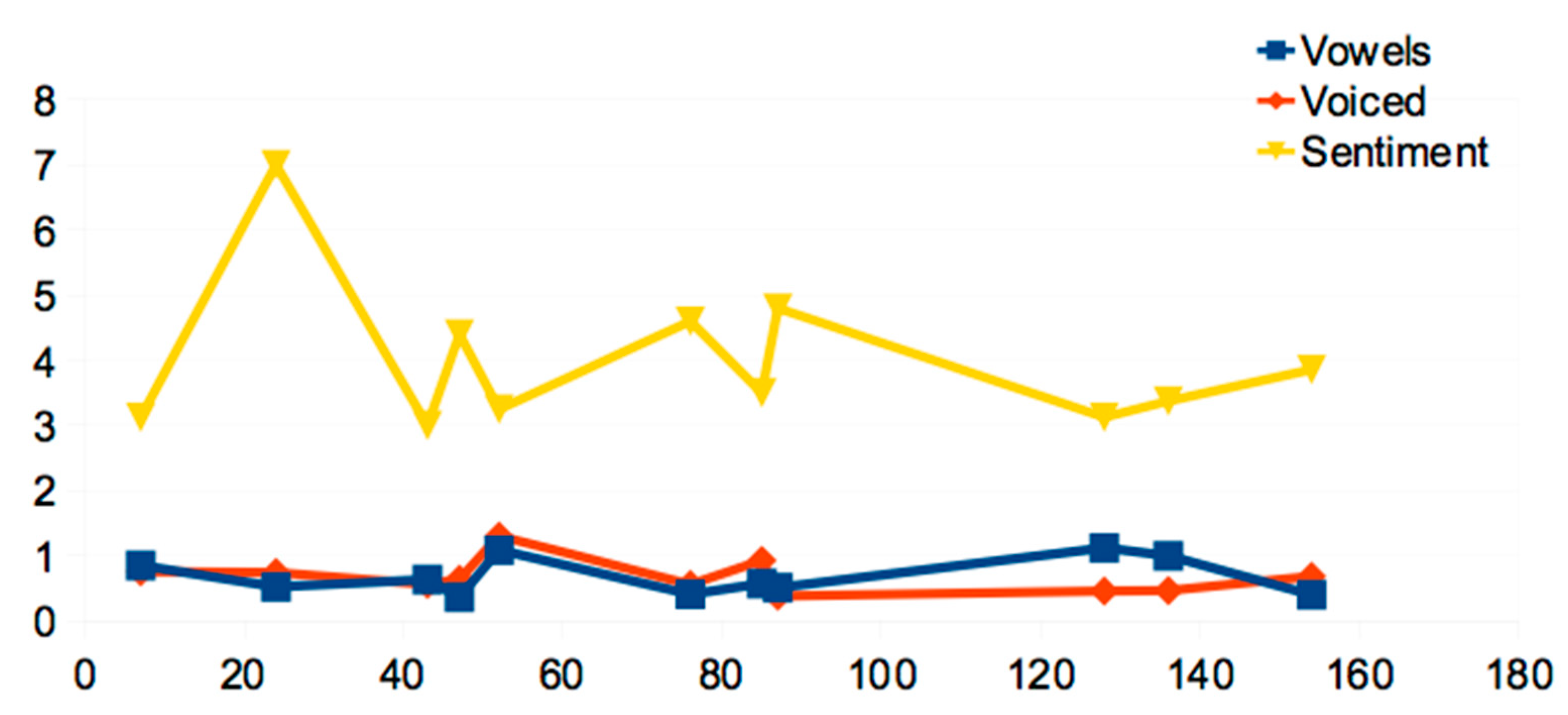

Figure 5.

The eleven most positively marked sonnets show the same slightly positive correlation for Vowels-Voicing but very strong negative correlation between Vowels-Sentiment and slightly negative for Voicing/Sentiment, -0.11423482.

Figure 5.

The eleven most positively marked sonnets show the same slightly positive correlation for Vowels-Voicing but very strong negative correlation between Vowels-Sentiment and slightly negative for Voicing/Sentiment, -0.11423482.

The conclusion we may draw is that the sound-sense harmony in Shakespeare's sonnets is represented by a strong extended disharmony: in particular in all the sonnets we have an inverse correlation, that is the two most important variables, Voicing (whether a consonant is a real Obstruent or not) and Sentiment. Voicing includes real obstruents and unvoiced continuants: |p,t,k,s,sh,f,th|. When the pair Voicing/Sentiment assumes a positive correlation value, the other pair Vowel/Sentiment shows the opposite and is negative. In particular, in those sonnet which are positively marked for sentiment, the Correlations between Vowel and Sentiment is positive but the correlation between Voicing and Sentiment is negative. Sonnets negatively marked for sentiment have a positive correlation between Voicing and Sentiment, but a negative correlation between Vowel and Sentiment. In other words the behaviour is just reversed: when meaning is positively marked the sound harmony verges towards a negative feeling. On the contrary when the meaning is negatively marked the sound harmony verges, bends towards a positive sound harmony. I assume what Shakespeare intended to produce in this way was a cognitive picture of ironic poetic creation.

3.2.5. From Sentiment to Deep Semantic and Pragmatic Analysis with ATF

The final part of the analysis takes us deep into the hidden meaning that the sonnets in what they communicate, i.e. irony. To do that we need to substitute sentiment analysis with a much more semantically consistent framework that could allow us to enter the more complex system of relational meanings that are governed by pragmatics. In this case, neither a word by word analysis a propositional level one would be sufficient. We need to capture sequences of words which may have a non-literal meaning and associate appropriate labels: this is what Appraisal Theory Framework can be useful for.

We have devised a sequence of steps in order to confirm experimentally our intuitions. The preliminary results obtained using sentiment analysis cannot be regarded as fully satisfactory for the simple reason that both the lexical and the semantic approach based on predicate-argument structures are unable to cope with the use of non-literal language. Poetic language is not only ambiguous but it contains metaphors which require abandoning the usual compositional operations for a more complex restructuring sequence of steps.

This has been carefully taken into account when annotating the sonnets by means of Appraisal Theory Framework (hence ATF). In our approach we have followed the so-called incongruity presumption or incongruity-resolution presumption. Theories connected to the incongruity presumption are mostly cognitive-based and related to concepts highlighted for instance, in [

28]. The focus of theorization under this presumption is that in humorous texts, or broadly speaking in any humorous situation, there is an opposition between two alternative dimensions. As a result, we have been looking for contrast in our study of the sonnets, produced by the contents of manual classification. Thus we have used the Appraisal Framework Theory [

29] - which can be regarded as the most scientifically viable linguistic theory for this task, as has already been done in the past by other authors (see [

30,

31] but also [

32,

33]), showing its usefulness for detecting irony, considering its ambiguity and its elusive traits.

Thus we proceeded like this: we produced a gold standard containing strong hints in its classification in terms of humour, by collecting most important literary critics' reviews of the 154 sonnets (the gold standard will be made available as supplementary material). To show how the classification has been organized we report here below two examples:

SEQUENCE: 1-17 Procreation MAIN THEME: One against many ACTION: Young man urged to reproduce METAPHOR: Through progeny the young man will not be alone NEG.EVAL: The young man seems to be disinterested POS.EVAL: Young man positive aesthetic evaluation CONTRAST: Between one and many

SEQUENCE: 18-86 Time and Immortality MAIN THEME: Love ACTION: The Young man must understand the sincerity of poet’s love METAPHOR: True love is sincere NEG.EVAL: The young man listens the false praise made by others POS.EVAL: Young Man positive aesthetic evaluation CONTRAST: Between true and fictitious love.

As can be seen, the classification is organized using 7 different linguistic components: we indicate SEQUENCE for the thematic sequence into which the sonnet is included; this is followed by MAIN THEME which is the theme the sonnet deals with; ACTION reports the possible action proposed by the poet to the protagonist of the poem; METAPHOR is the main metaphor introduced in the poem sometimes using words from a specialized domain; NEG.EVAL and POS.EVAL stand for Negative Evaluation and Positive Evaluation contained in the poem in relation to the theme and the protagonist(s); finally, CONTRAST is the key to signal presence of opposing concrete or abstract concepts used by Shakespeare to reinforce the arguments purported in the poem. Not all the sonnets were amenable to a pragmatic/linguistic classification. We ended up with 98 sonnets classified over 154, corresponding to a percentage of 63.64%, the rest have been classified as Blank. Many sonnets have received more than one possible pragmatic category. This is due to the difficulty in choosing one category over another. In particular, it has been particular hard to distinguish Irony from Satire, and Irony from Sarcasm. Overall, we ended up with 54 sonnets receiving a double marking over 98. This was also one of the reasons to use ATF: often literary critics were simply hinting at "irony" or "satire", but the annotation gave us a precise measure of the level of contrast present in each of the sonnets regarded generically as "ironic".

The annotation has been organized around only one category, Attitude, and its direct subcategories, in order to keep the annotation at a more workable level, and to optimize time and space in the XML annotation. Attitude includes different options for expressing positive or negative evaluation, and expresses the author’s feelings. The main category is divided into three primary fields with their relative positive or negative polarity, namely:

Affect is every emotional evaluation of things, processes or states of affairs, (e.g. like/dislike), it describes proper feelings and any emotional reaction within the text aimed towards human behaviour/process and phenomena.

Judgement is any kind of ethical evaluation of human behaviour, (e.g. good/bad), and considers the ethical evaluation on people and their behaviours.

Appreciation is every aesthetic or functional evaluation of things, processes and state of affairs (e.g. beautiful/ugly; useful/useless), and represent any aesthetic evaluation of things, both man-made and natural phenomena.

Eventually, we ended up with six different classes:

Affect Positive,

Affect Negative,

Judgement Positive,

Judgement Negative,

Appreciation Positive,

Appreciation Negative. Overall in the annotation there is a total majority of positive polarities with a ratio of 0.511, in comparison to negative annotations with a ratio of 0.488. In short, the whole of the positive poles is 607, and the totality of the negative poles is 579 for a total number of 1186 annotations.

Judgement is the more interesting category because it allows social moral sanction, which is then split into two subfields,

Social Esteem and

Social Sanction - which however we decided not to mark. In particular, whereas the positive polarity annotation of

Judgement extends to

Admiration and

Praise, the negative polarity annotation deals with

Criticism and

Condemnation or

Social Esteem and

Social Sanction (see [

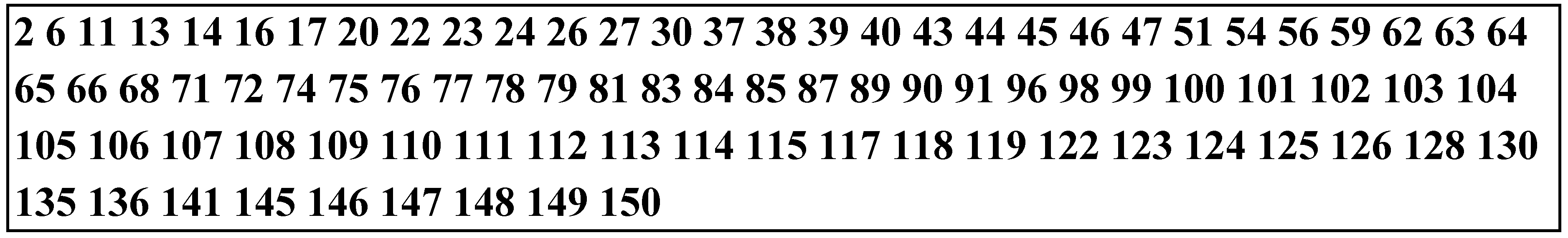

33], p.52). Here below the list of 77 sonnets manually classified with ATF over 98 matching critics' evaluation.

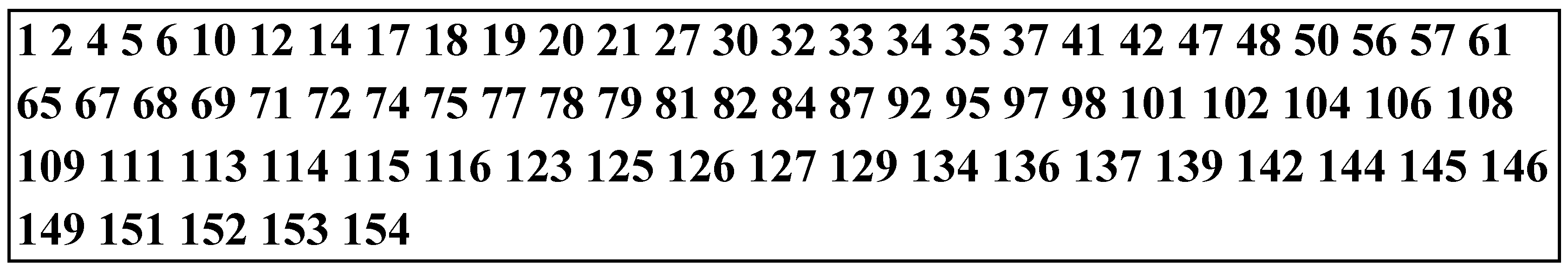

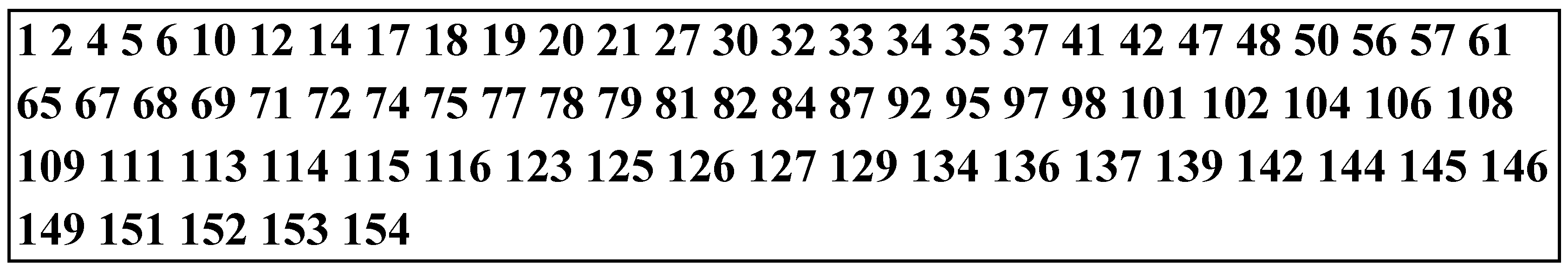

List of 77 successfully classified sonnets matching critics’ evaluation

As a first result, we may notice a very high convergence existing between critics’ opinions and the output of manual annotation by

Appraisal classes: 77 over 98 correesponds to a percentage of 78%. As to the sonnets' structure,

Judgement is found mainly in the final couplet of the sonnets.(for more details see [

37]). As to interpretation criteria, we assumed that the sonnets with the highest contrast could belong to the category of

Sarcasm. The reason for this is justified by the fact that a high level of

Negative Judgements accompanied by

Positive Appreciations or

Affect is by itself interpretable as the intention to provoke a sarcastic mood. As a final result, there are 44 sonnets that present the highest contrast and are specifically classified according to the six classes above. There is also a group that contains ambiguity sonnets which have been classified with a double class, mainly by

Irony and

Sarcasm. As a first remark, in all these sonnets, negative polarity is higher than positive polarity with the exception of sonnet 106. In other words, if we consider this annotation as the one containing the highest levels of

Judgement, we come to the conclusion that a possible

Sarcasm reading is mostly associated with presence of

Judgement Negative and in general with high

Negative polarity annotations.

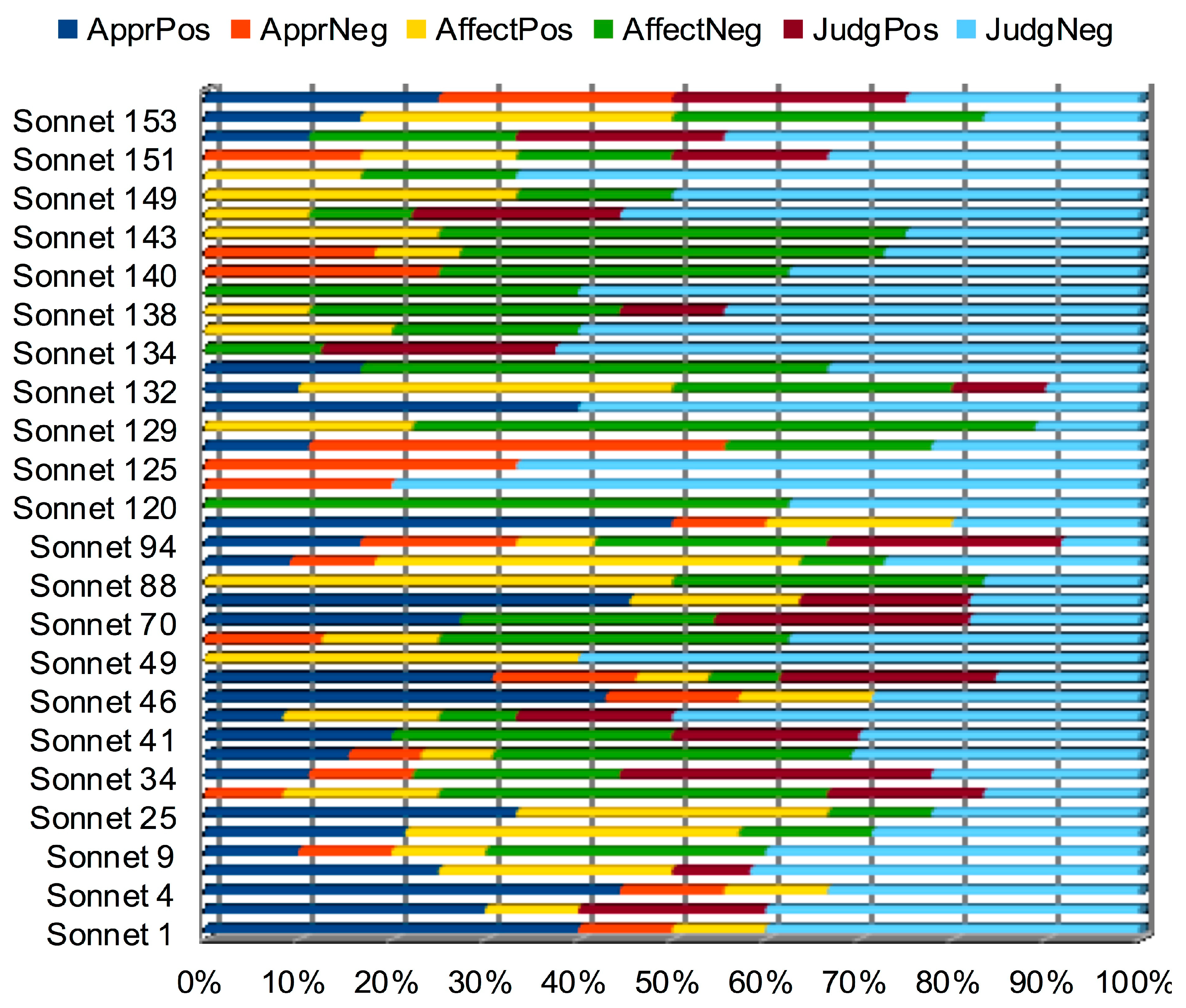

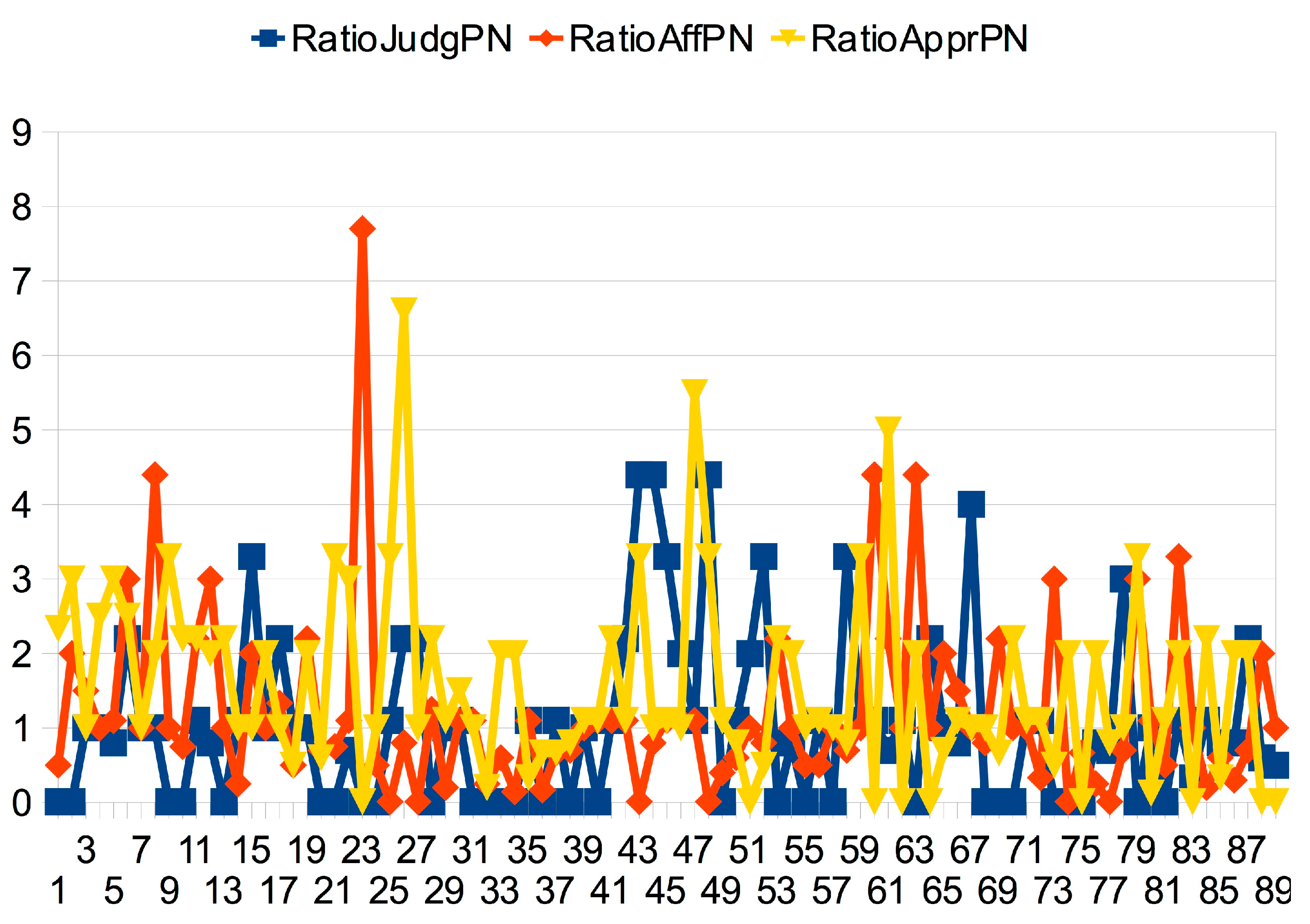

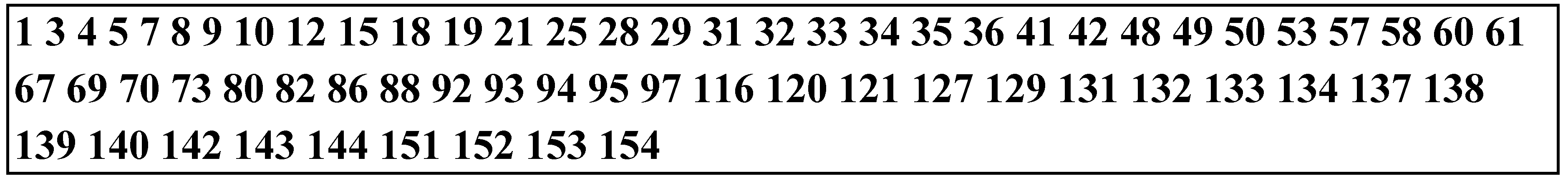

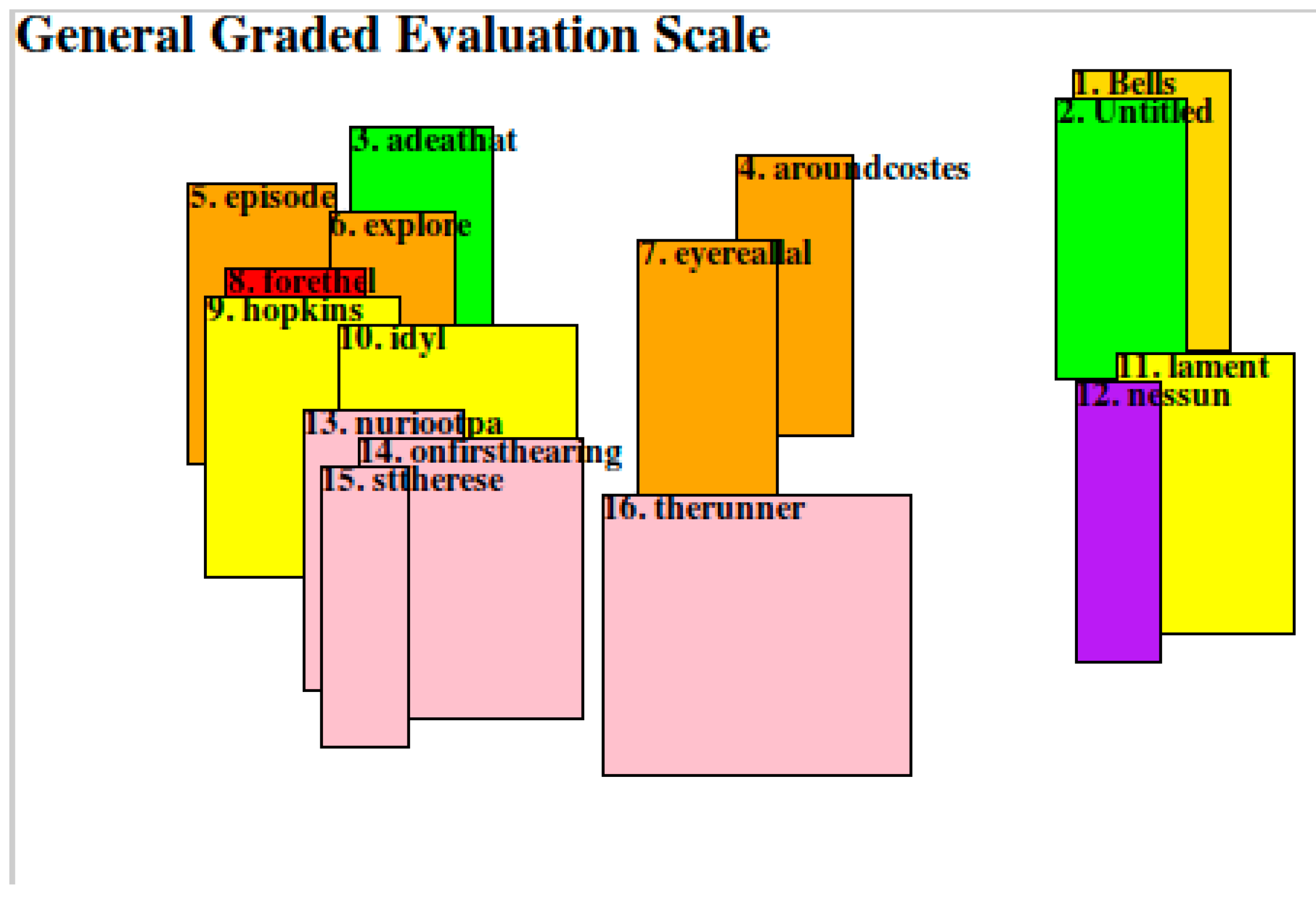

Figure 6.

44 sonnets classified with Sarcasm with the highest level of Judgements.

Figure 6.

44 sonnets classified with Sarcasm with the highest level of Judgements.

We associated different colours to make the subdivision into the six classes visually clear. It is possible to note the high number of Judgements both Negative (in orange) and Positive (in pale blue): in case Judgement Positive is missing it is substituted by Affect Positive (pale green) or by Appreciation Positive (blue). This applies to all 44 sonnets apart from sonnets 120 and 121 where Judgement Negative is associated to Affect Negative and to Appreciation Negative. In other words, if we consider this annotation as the one containing the highest levels of Judgement, we come to the conclusion that possible Sarcasm reading is mostly associated with presence of Judgement Negative and in general with high Negative polarity annotations. As a first result we may notice a very high correlation existing between critics’ opinions as classified by us with the label highest contrast and the output of manual annotation by Appraisal classes.

Table 10.

Quantitative data for six appraisal classes for sonnets with highest contrast.

Table 10.

Quantitative data for six appraisal classes for sonnets with highest contrast.

| |

Appr.Pos |

Appr.Neg |

Affct.Pos |

Affct.Neg |

Judgm.Pos |

Judgm.Neg |

| Sum |

56 |

25 |

53 |

77 |

32 |

122 |

| Mean |

2.533 |

1.133 |

2.4 |

3.466 |

1.444 |

5.466 |

| St.Dev. |

8.199 |

3.691 |

7.732 |

11.202 |

4.721 |

17.611 |

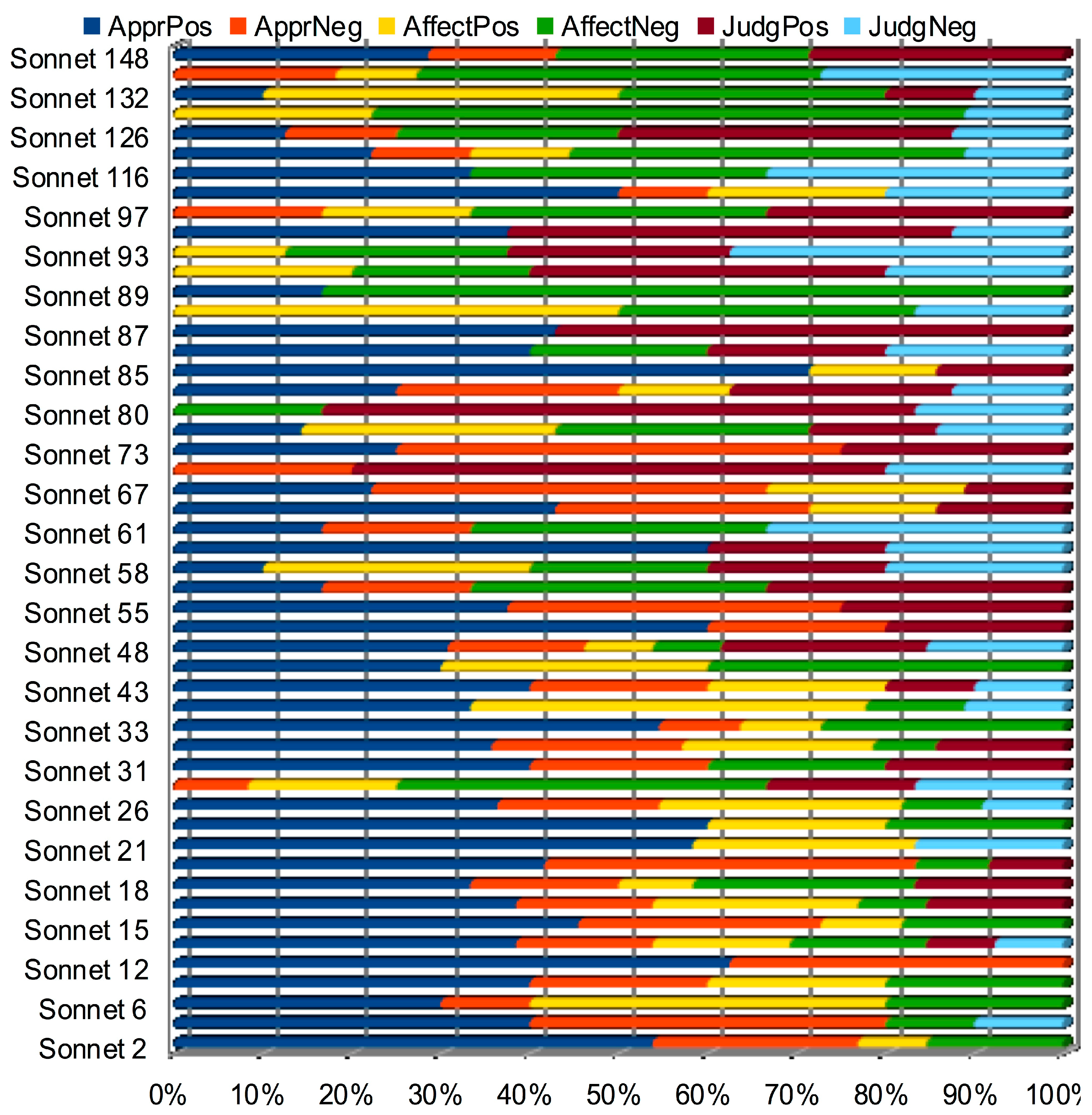

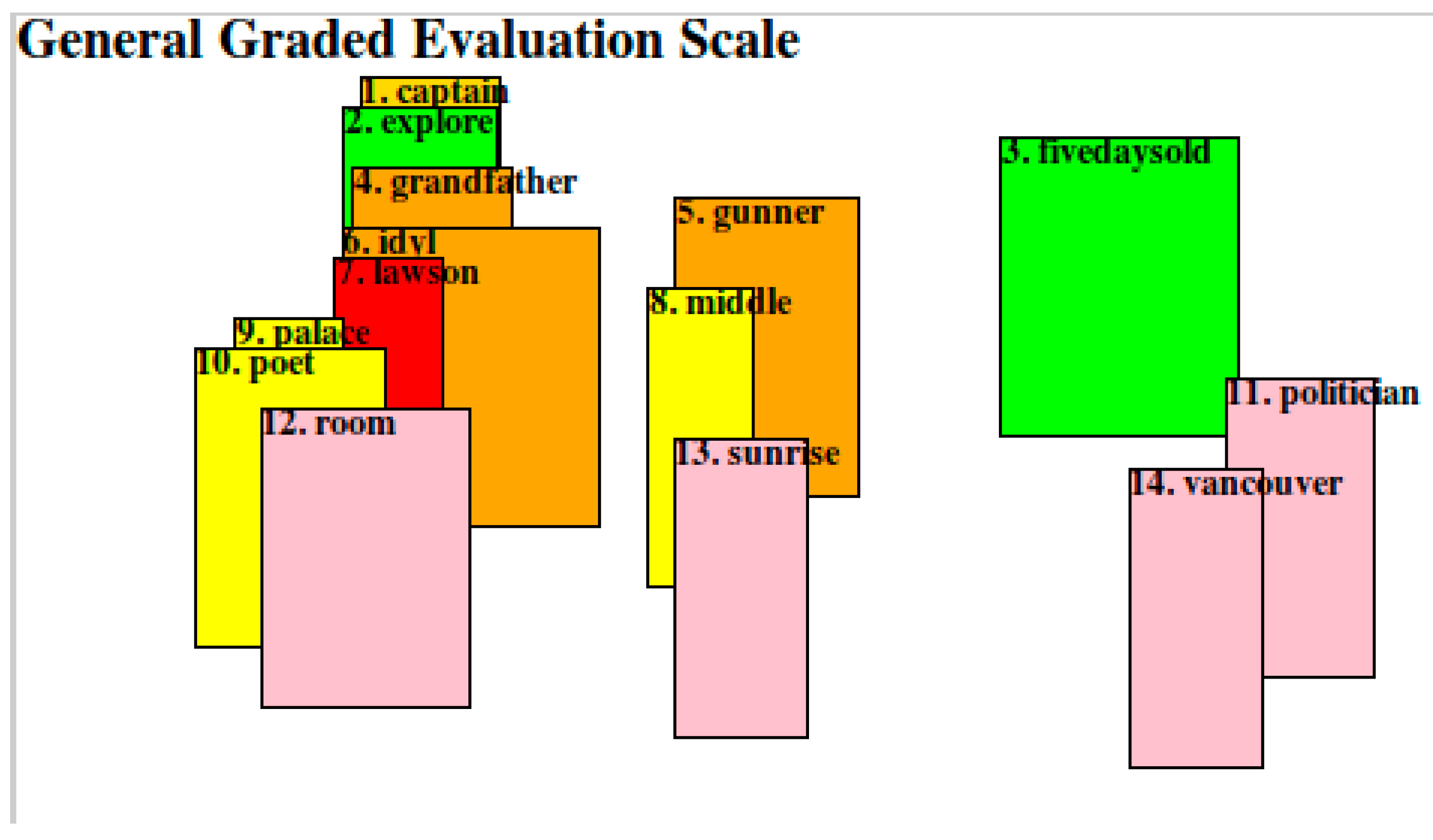

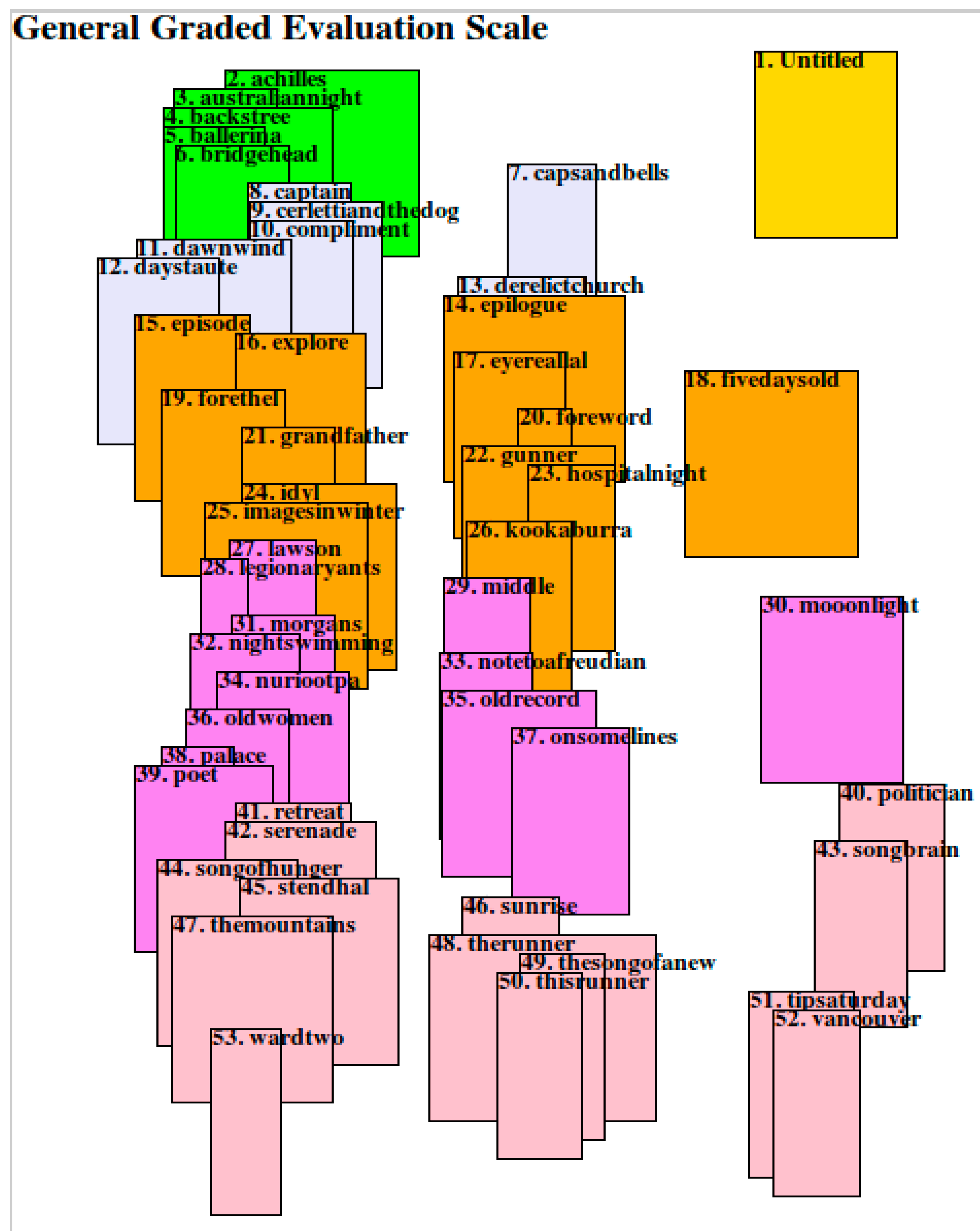

We now show the group of 50 sonnets classified, mainly or exclusively, with Irony and check their compliance with Appraisal classes.

Figure 7.

50 sonnets classified with Irony, with a lower level of Judgement Negative but higher Affect Negative.

Figure 7.

50 sonnets classified with Irony, with a lower level of Judgement Negative but higher Affect Negative.

As can be easily noticed, the presence of Judgement Negative is much lower than in the previous diagram for Sarcasm. In fact in only half of them – 25 – has annotation for that class, the remain half introduces two other negative classes: mainly Affect Negative, but also Appreciation Negative. As to the main Positive class, we can see that it is no longer Judgement Positive, but Affect Positive which is present in 33 sonnets.

Table 11.

Quantitative data for six appraisal classes for sonnets with lowest contrast.

Table 11.

Quantitative data for six appraisal classes for sonnets with lowest contrast.

| |

Appr.Neg |

Appr.Pos |

Affct.Pos |

Affct.Neg |

Judgm.Pos |

Judgm.Neg |

| Sum |

139 |

65 |

64 |

81 |

59 |

37 |

| Mean |

5.346 |

2.5 |

2.461 |

3.115 |

2.269 |

1.423 |

| St.Dev. |

18.82 |

8.843 |

8.707 |

11.009 |

8.029 |

5.047 |

In other words we can now consider that Sarcasm is characterized by a majority of negative evaluations 146/224 while Irony is characterized by a majority of Positive evaluations 262/183 and that the values are sparse and unequally distributed.

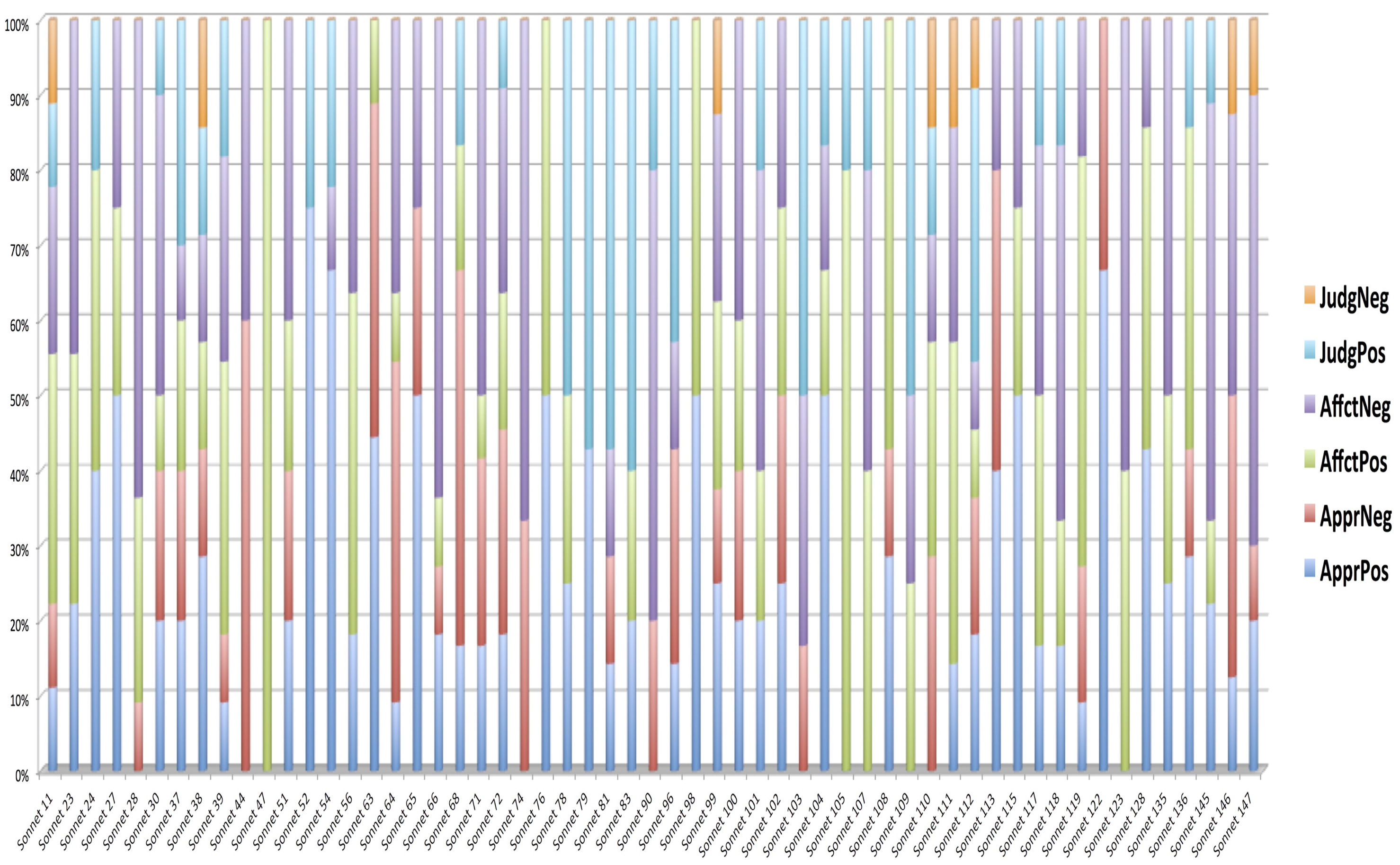

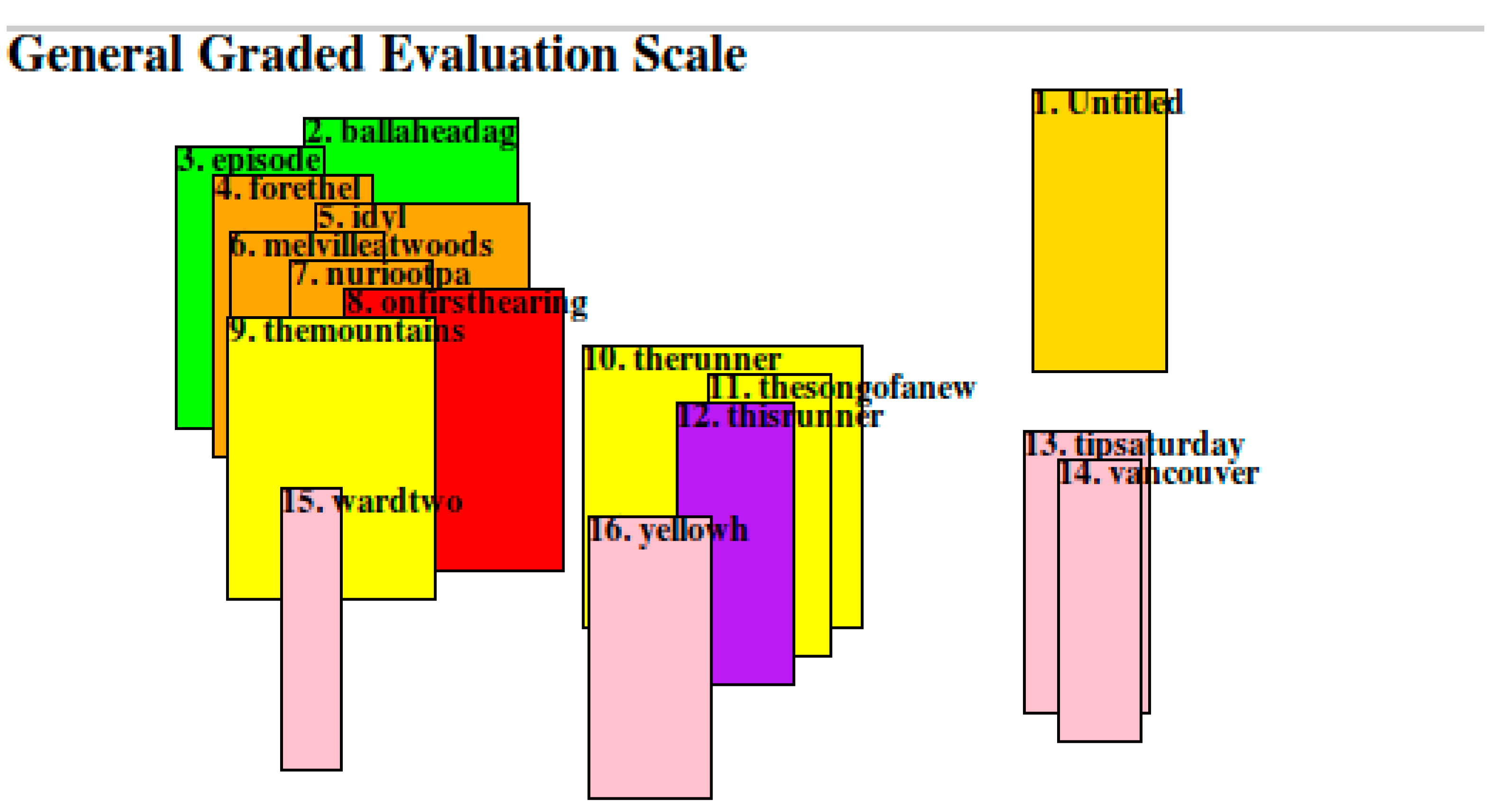

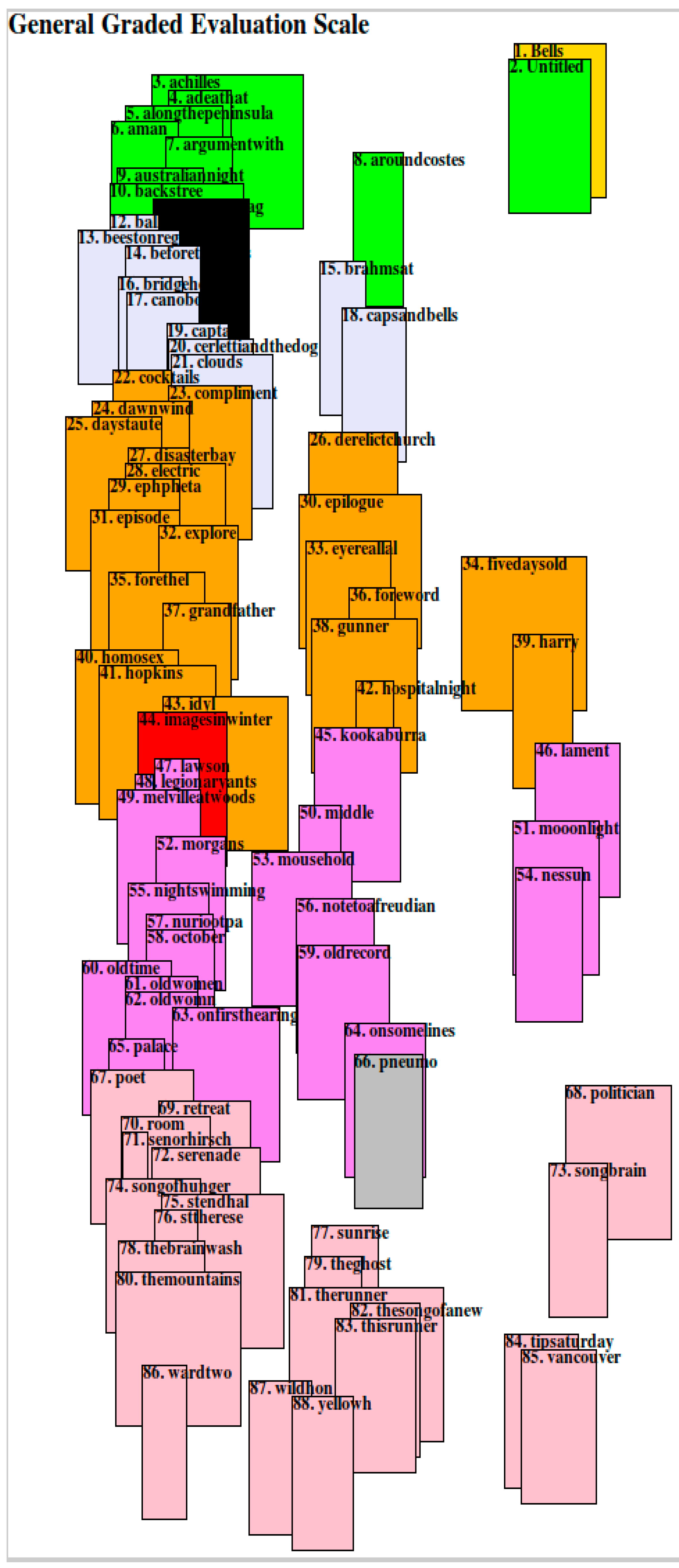

The final figure concerns the number of sonnets with blank or neutral evaluation by critics which amount to 60. As a rule, this group of sonnets should look different from the two groups we already analysed.

Figure 8.

60 Sonnets classified by critics as neutral.

Figure 8.

60 Sonnets classified by critics as neutral.

As expected, this figure looks fairly different from the previous two. The prevailing colour is pale blue i.e. Judgement Positive; orange i.e. Appraisal Negative, is only occasionally present; green is perhaps the second prominent colour, i.e. Affect Positive. In order to know how much is the difference we can judge it from the quantities shown in the table below.

Table 4.

Quantitative data for six appraisal classes for sonnets with no contrast.

Table 4.

Quantitative data for six appraisal classes for sonnets with no contrast.

| |

Appr.Pos |

Appr.Neg |

Affct.Pos |

Affct.Neg |

Judgm.Pos |

Judgm.Neg |

| Sum |

88 |

59 |

89 |

109 |

49 |

8 |

| Mean |

3.034 |

2.034 |

3.068 |

3.758 |

1.689 |

0.275 |

| St.Dev. |

1.268 |

7.638 |

11.482 |

14.052 |

6.368 |

1.079 |

3.2.6. Matching ATF classes with the Sound-Sense Harmony

The experiment with ATF classes matching critics' evaluation has been fairly successful, but how do these classes gauge with the sound-sense harmony? In order to check this we transferred the data related to vowels and consonants and matched them with ratios of the three main ATF categories: Appreciation Positive/Negative, Affect Positive/Negative, Judgement Positive/Negative. As in previous computation, all data below 1 will be interpreted as a case of superior Negative Polarity and the opposite when data are above 1. In order to get a better view of the overall data, we split them into sonnets with contrast a first group, and sonnets with no contrast a second group. This time, however, we used our classification and abandoned the critics' one.

Figure 9.

Distribution of 89 sonnets manually classified by ATF with no contrast.

Figure 9.

Distribution of 89 sonnets manually classified by ATF with no contrast.

The data in

Figure 10 show the distribution of sound-sense variable for the three parameters: we didn’t introduce variables for vowels and voicing which are however present in the same table and allow us to evaluate the correlation between ATF and sound, which as can be seen below is negative for both

Judgement and

Affect:

Correlation between Vowels and Judgement: -0.1254

Correlation between Voicing and Judgement: -0.1468

Correlation between Vowels and Affect: -0.08859

Correlation between Voicing and Affect: -0.01346

Correlation between Judgement and Affect: -0.1376

Correlation between Affect and Appraisal: -0.0351

Correlations of sound data with Appraisal are on the contrary both positive. If we consider now the remaining 65 sonnets which have been classified by ATF with contrast we get a different picture. In this case, we have separated each class and projected them with sound data, Vowels and Voicing in the following three diagrams.

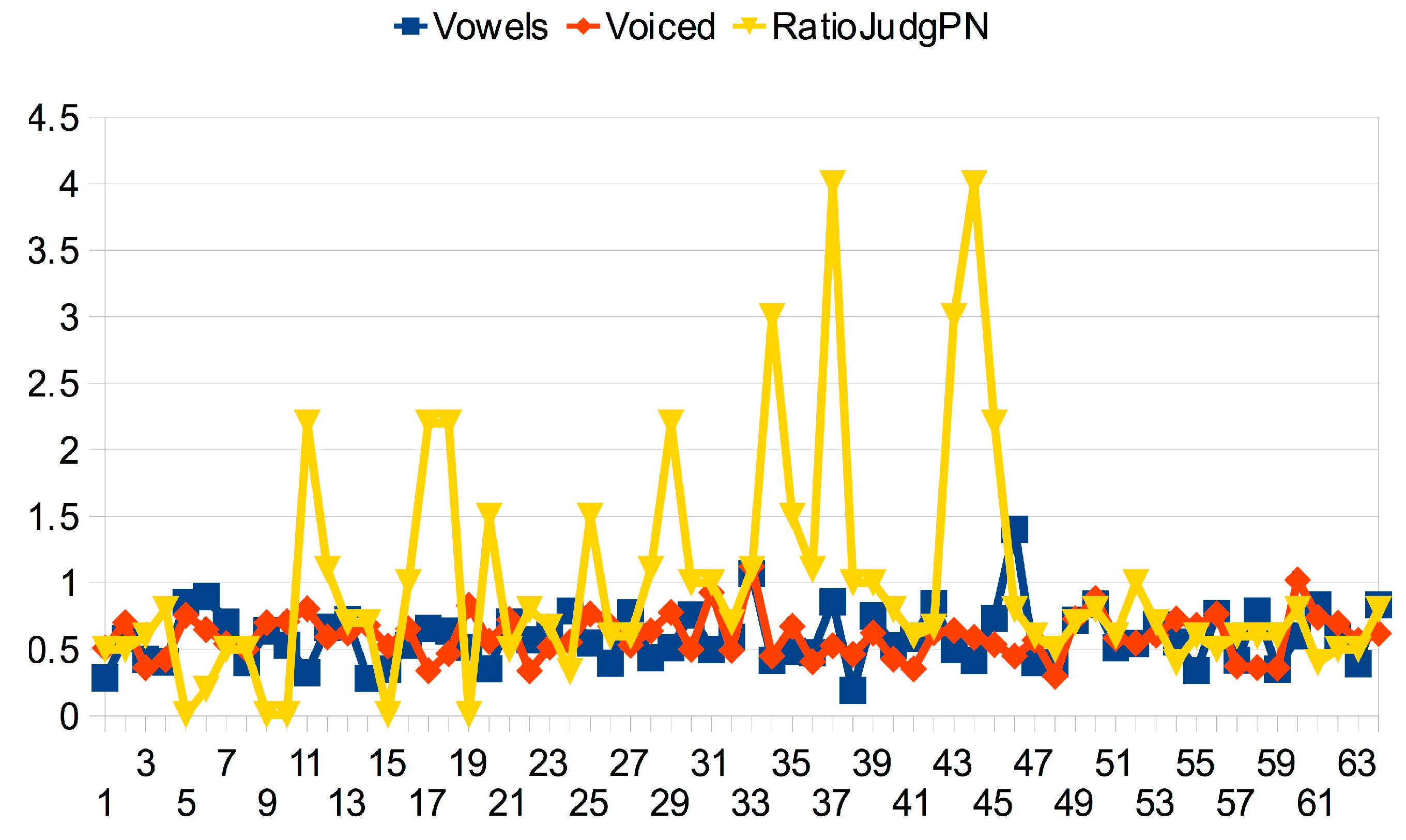

Figure 10.

Distribution of 65 sonnets classified as Judgements with contrast and their sound data.

Figure 10.

Distribution of 65 sonnets classified as Judgements with contrast and their sound data.

All correlation measures with Judgements are negative:

Correlation between Vowels and Judgements: -0.0594

Correlation between Voicing and Judgements: -0.0677

Correlation between Judgement and Affect: -0.0439

Correlation between Judgement and Appraisal: -0.0522

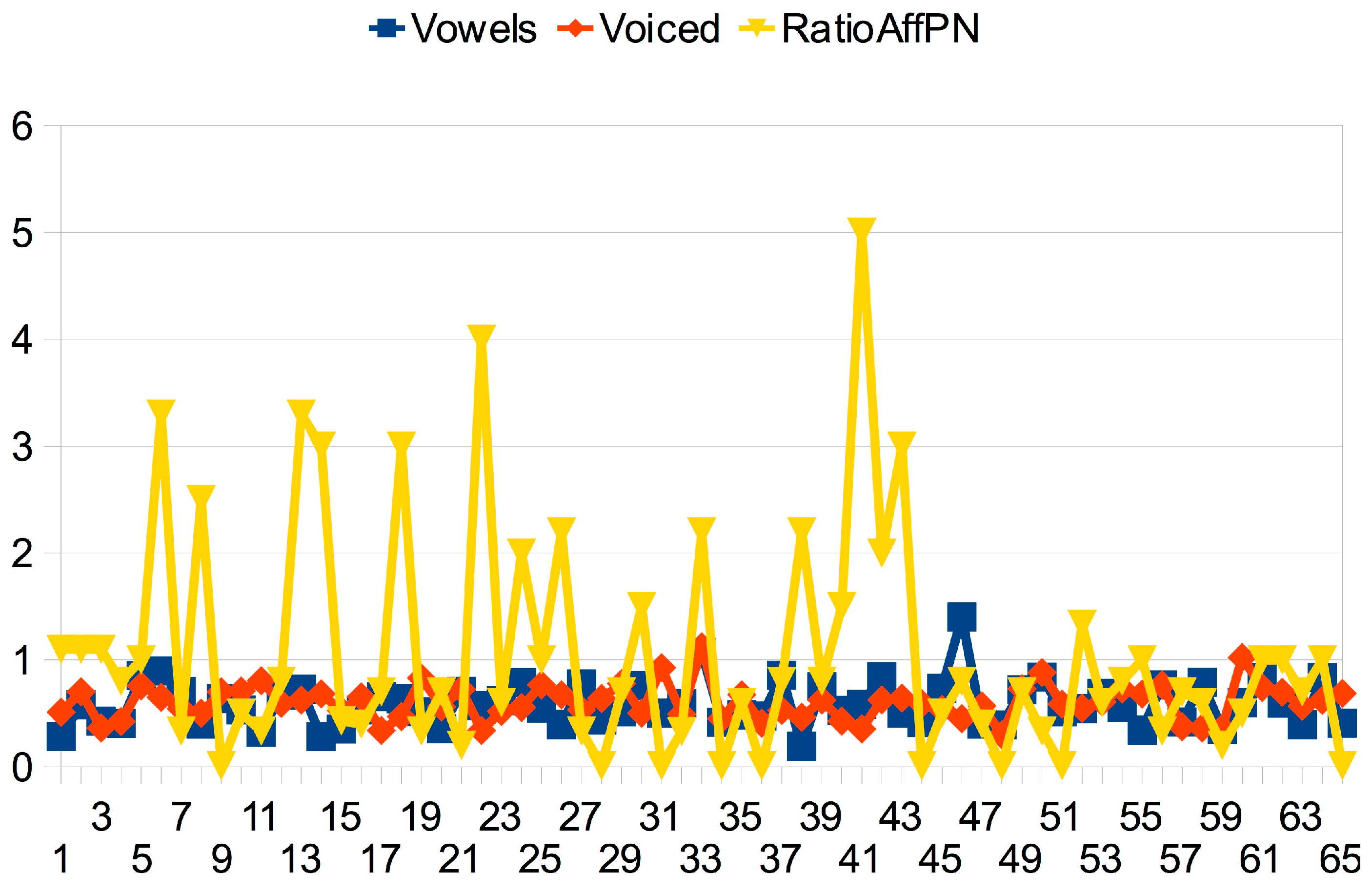

Figure 11.

Distribution of 65 sonnets classified by ATF as Affect with contrast and their sound data.

Figure 11.

Distribution of 65 sonnets classified by ATF as Affect with contrast and their sound data.

Correlation data for Affect are only partly negative:

Correlation between Vowels and Affect: 0.09

Correlation between Voicing and Affect: -0.1435

Correlation between Affect and Appraisal: 0.2594

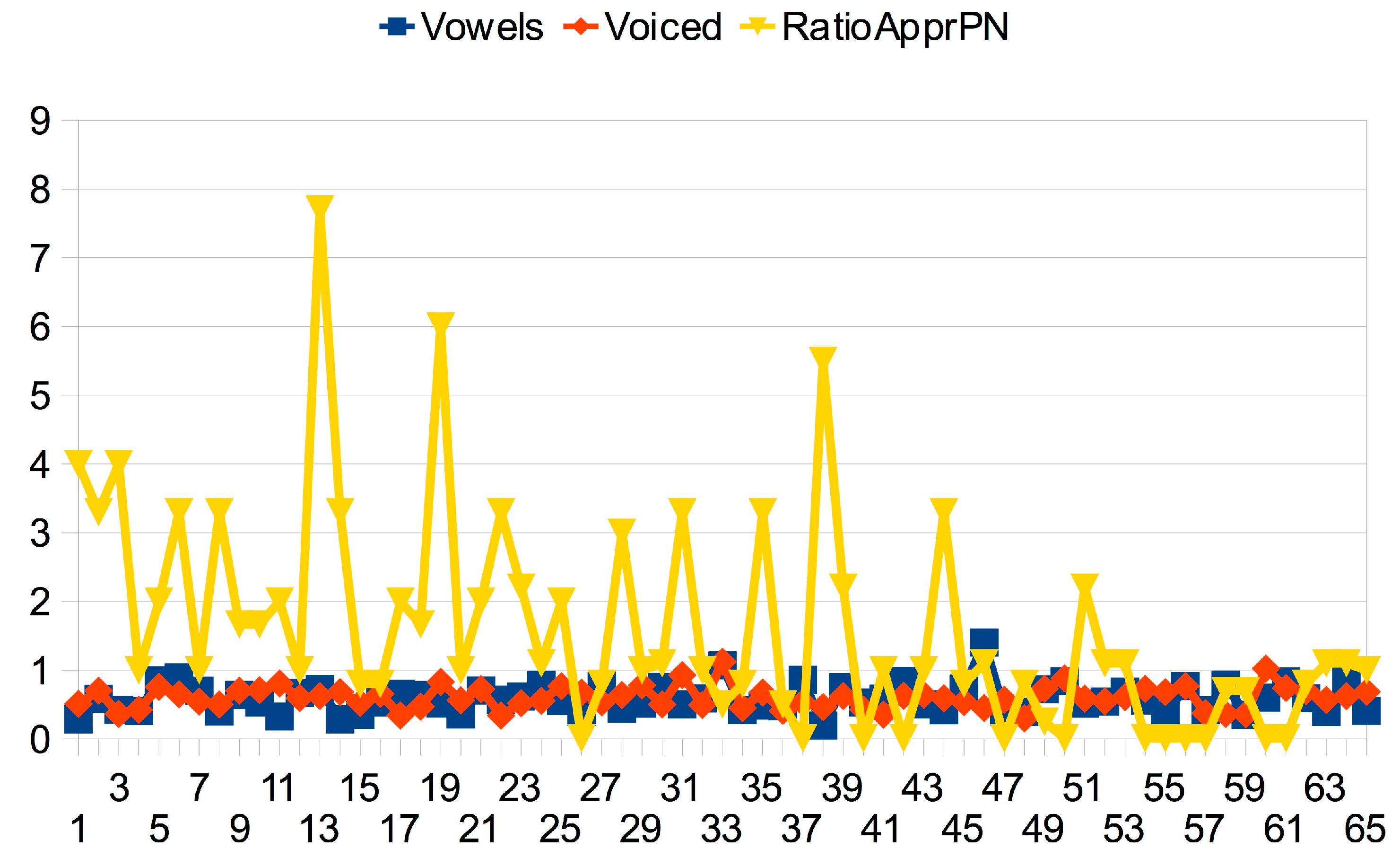

Figure 12.

Distribution of 65 sonnets classified by ATF as Appraisal with contrast and their sound data.

Figure 12.

Distribution of 65 sonnets classified by ATF as Appraisal with contrast and their sound data.

Eventually, the correlations for Appraisal are also both negative:

Now the only positive correlations are the ones shown by Affect with Vowels and with Appraisal, the remaining correlations are all negative. The subdivision operated now using our manual classification with ATF seems more consistent than the one made before using the critics' evaluation. As a first comment, these data confirm our previous evaluation made on the basis of Sentiment analysis, i.e. the sonnets are all disharmonic due to Shakespeare's intention to produce ironic effects on the audience. Here below the list of the 89 sonnets classified by our manual ATF labeling as having no contrast:

List of 89 sonnets manually classified by ATF as having no contrast

List of 65 sonnets manually classified by ATF as having contrast

Comparing the "contrast" criterion with the sentiment-based classification is not possible however, the "contrast" group of sonnets is included in majority in the "negatively" marked sonnets, with the exception of 16 sonnets which are the following ones:

What these sonnets have in common is an identical number of Appraisal Positive/Negative feature (28), a high number of Affect Negative feature (38) vs Positve ones (11), and the relatively lowest number of Judgement Negative features (10) vs Positive ones (18). In other words, by decomposing Negative Polarity items into three classes shows the weakness of Sentiment Analysis, where Negativity is a cover all class.