1. Introduction

Dialogue state tracking (DST) is a critical component in task-oriented dialogue systems. It is responsible for inferring the user’s goals and intentions by tracking the slots and their corresponding values in the dialogue. DST aims is to provide a compact representation of the dialogue, known as the dialogue state, which consists of triples <domain, slot, value>, used by the system to determine the next action. Therefore, the accuracy of dialogue state tracking is crucial for the performance of the system.

DST methods typically involve predefined slots and their possible values, known as ontology, to guide the tracking of dialogue states [

1]. These methods assume that all possible slot-value pairs are known, allowing for direct matching of predefined slots and values during the dialogue to update the state. These slots and intents are often represented as abbreviations, such as train-leaveat and hotel-internet, indicating the target information to track in the task domain. In this approach, scores are typically assigned to all possible slot-value pairs in the ontology, and the highest scoring pair is selected as the predicted dialogue state. In recent years, dialogue state tracking has gained increasing attention, leading to the development of various classical models [

2,

3,

4].

Despite the progress made by neural network-based dialogue state tracking methods, these approaches often overlook the correlations between slots when making predictions for each slot. For instance, in the second round of the human-computer dialogue shown in

Figure 1, the user’s last utterance is “A 3-star hotel in the same area and price range as my restaurant”. This sentence indicates that the hotel should have the same area and price range as the restaurant, and the predicted values should be <hotel, price range, expensive> and <hotel, area, south>. However, since the words “expensive” and “south” are not explicitly mentioned in the sentence, they cannot be extracted. Some researchers have recognized the importance of modeling slot correlations to some extent [

5,

6]. In these works, the correlations between slot names have been considered [

7], or prior knowledge has been incorporated [

5], where artificially set slot correlation coefficients are assigned a value of 1. However, these approaches only consider the association between slot names.

Table 1.

In a task-oriented multi-turn dialogue example, the values of the slots “hotel-pricerange” and “hotel-area” should correspond to the same values as the slots “restaurant-pricerange” and “restaurant-area”.

Table 1.

In a task-oriented multi-turn dialogue example, the values of the slots “hotel-pricerange” and “hotel-area” should correspond to the same values as the slots “restaurant-pricerange” and “restaurant-area”.

| User: |

Can you help me find a place to eat in the expensive price range in the south part of town? |

| Sys: |

What about the Cambridge chop house. The address is: 1 kings Parade. Do you like me to book a table? |

| User: |

Yes! Can you book for 2 people at 14:15 on this Sunday? |

| Sys: |

I was able to book your party of 2 into The Chop House on Sunday at 14:15 Reference: MUWLBLLW. |

| User: |

Actually yes I will be needing somewhere to stay too please. A 3 star hotel in the same area and price range |

| |

as my restaurant. |

| Sys: |

I have one matching result. It is the lensfield hotel. Do you want to reserve a room? |

| User: |

Yes please, two people for two nights on Sunday. |

To address this issue, Ye [

8] proposed the Slot Self-Attentive Dialogue State Tracking (STAR) model, which utilizes both the slot names and the context related to the slots to capture slot relationships more accurately through slot self-attention. It learns the correlations between slots in a fully data-driven manner without any manual effort or prior knowledge. However, it learns the relationships between multi-domain slots from a single sample, which may introduce bias during prediction and potentially involve redundant information from other slots.

In this work, a dialogue state tracking model, ER-DST, is proposed to enable the learning of relationships between multi-domain slots from global samples. The model utilizes an external slot relation memory, consisting of keys and values, to capture the relationship characteristics between slots and learn a dictionary of relationships for multi-domain slots. A small-scale filter is employed to reduce the weight of irrelevant slots, thereby excluding interference from other slots. By leveraging the external slot relation memory to learn the most discriminative features of slot relationships, the proposed approach achieves joint goal accuracy of 54.76% on MultiWOZ 2.0 [

9] and 56.75% on MultiWOZ 2.1 [

10], while maintaining linear complexity.

2. Related Work

Traditional dialogue state tracking models heavily rely on extracting triplet information from natural language understanding to predict the current dialogue state [

11,

12,

13]. However, these models rely on manually crafted rules and domain-specific delexicalization, which incurs significant manual effort and limits the models’ generalization ability in multi-domain conversations.

With the rise of deep learning, researchers have applied various deep neural networks to the task of dialogue state tracking. Henderson [

14] utilized a deep fully connected neural network to calculate the probabilities of all slot values for each slot, predicting the slot values. Mrkić [

1] proposed the Neural Belief Track (NBT) model, which leverages representation learning to embed candidate slot-value pairs and dialogue embeddings into dense word vectors and infers their representations during decoding to determine whether the slot-value pair appears in the dialogue. Models such as TRADE [

15] combine the copy mechanism and generation mechanism, weighting the probability distributions obtained from both mechanisms at each decoding step of a slot value and using recurrent neural networks to capture semantic correlations between dialogue contexts to improve prediction capabilities. SOM-DST [

16] treats the dialogue state as a selectively rewritable storage structure, decoupling dialogue state tracking into two subtasks: state operation prediction and slot value generation. TripPy [

6] proposes the simultaneous use of three copy mechanisms to fill in slots, addressing the issue of open vocabulary. Gao [

17] adopts a reading comprehension approach for state updates. In [

18], an attention-based pointer network is used to copy and slot values from the dialogue context. Guo [

19] proposes the DiCoS-DST model, which implements a dynamic selection method for dialogue history. However, the models mentioned above treat slot tracking and dialogue history modeling as independent components without explicitly modeling their relationship.

In recent years, pre-trained language models [

20,

21] have demonstrated excellent semantic encoding capabilities in downstream tasks and have received significant attention. For example, the SUMBT model proposed by Lee [

3] encodes slot representations and dialogue representations using BERT and models the relationship between slots and dialogues through attention mechanisms. Zhu [

22] uses a fusion network that combines context and pattern graphs to model dialogue states. Li [

23] explores the hierarchical semantics of ontologies and enhances the relationships between slots through masked hierarchical attention. The LUNA model proposed by Wang [

24] explicitly aligns each slot with its most relevant utterances and designs a slot ranking auxiliary task to learn the temporal correlations between slots. Feng [

25] propose a method that dynamically integrates previous slot-domain member relationships and dialogue-aware dynamic slot relationships to generate pattern graphs. Jiao [

26] addresses the issue of insufficient contextual understanding in dialogues by introducing a hierarchical DST framework that models second-order slot interaction. The STAR model proposed by Ye [

8] simultaneously utilizes slot names and context related to slots to capture the relationships between slots using slot self-attention more accurately. Although the above methods consider slot relationships to some extent, learning slot relationships from a single sample narrows the model’s learning scope and makes it difficult to capture the fundamental connections between slots. There is often a problem with introducing interference information.

3. Model

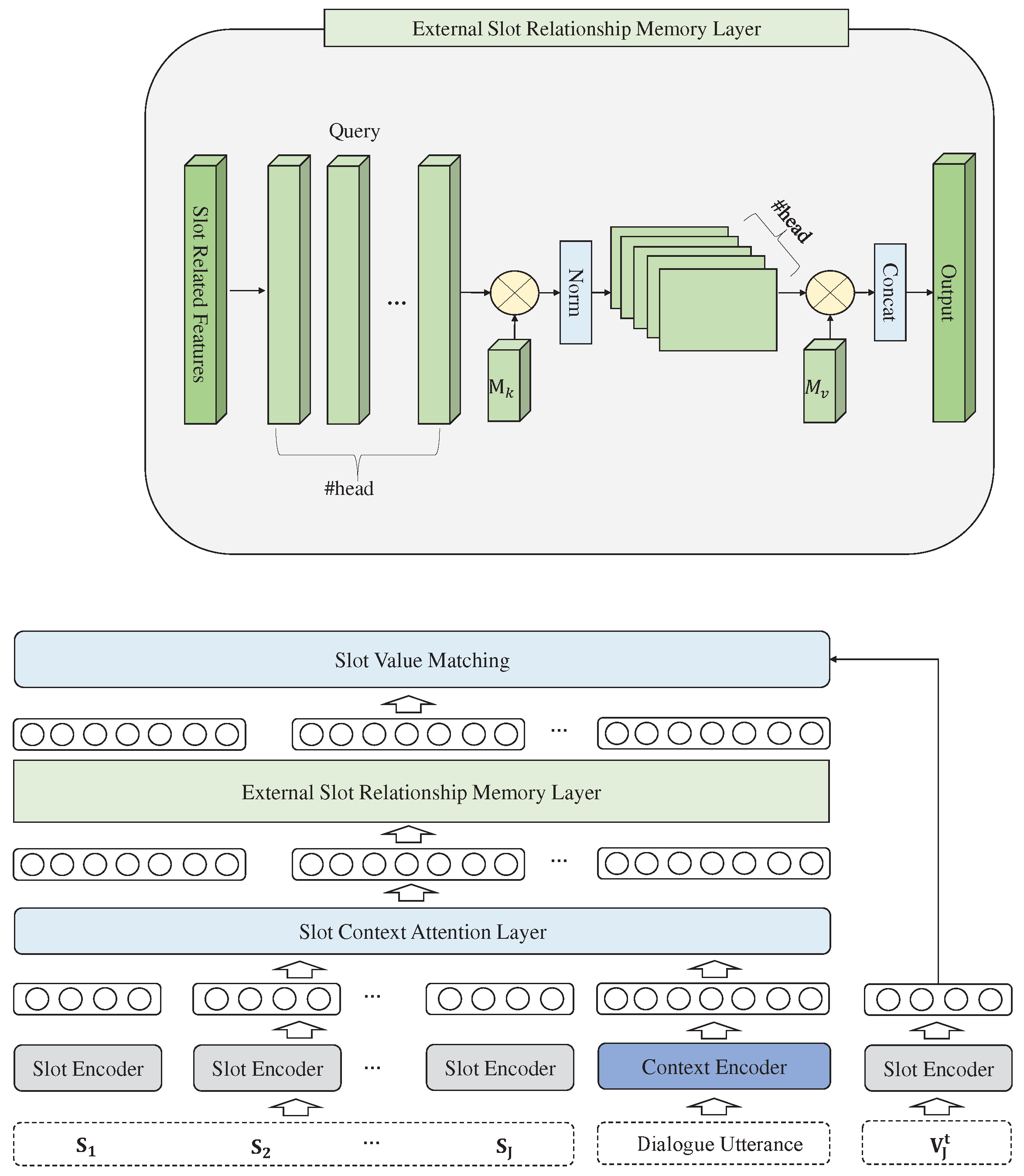

Figure 1 illustrates an overview of the model, which consists of four main parts. Firstly, the Context Encoder encodes the input dialogue and outputs a semantic vector representation. The second part is the Slot Attention, which extracts slot-related information from the encoded context. The third part is the External Attention layer, which models the relationships between slots, allowing the model to learn important information from multiple domains in the dialogue and exclude interference information from other slots.

3.1. Problem definition

In the dialogue domain, the important information to be tracked is defined as a set of slots, denoted as

, where J represents the number of slots.

represents the dialogue history up to the t-th round.

represents the dialogue utterance in the t-th round, where

and

represent the user and system utterances, respectively.

represents the dialogue state in the t-th round, where

represents the j-th slot and its corresponding slot value in the t-th round. Specifically,

is empty in the first round. The goal of dialogue state tracking is to predict the current dialogue state

based on the given dialogue context composed of

,

, and

, denoted as:

3.2. Context Encoder

In recent years, BERT [

20], a pre-trained language model, has demonstrated powerful contextual semantic representation capabilities in various downstream tasks. Therefore, in this paper, we adopt the BERT pre-trained model for encoding the context. At dialogue turn T, the dialogue history is defined as

, which is a collection of system responses R and user utterances U, where

and

. We define

as the dialogue state at each turn, where each

represents a collection of J slot-value pairs.The context encoder takes the dialogue history up to turn t, which can be represented as

, as input and generates the context vector representation

as its output. For each slot

and its corresponding value

, we encode them using

, where we use the output vector corresponding to the special token [CLS] as the slot representation. During training, we keep the model parameters fixed.

3.3. Slot Contextual Information Extraction Layer

In the context of a dialogue, each slot pays attention to different parts of the dialogue context. To predict the state of a specific slot, it is necessary to extract slot-specific feature information from the dialogue history. To achieve this, we employ a slot attention mechanism based on multi-head attention [

27]. This mechanism allows the model to focus on relevant parts of the dialogue utterances that are informative for predicting a specific slot, thereby improving prediction accuracy. It enables the subsequent layers of the model to capture the semantic information and contextual information specific to each slot, thus capturing the interrelationships between slots effectively.

The parameters

,

,

,

,

, and

are linear layer parameters used to map the queries, keys, and values, respectively. Here,

, where

represents the hidden size of the model and N is the number of heads in the multi-head attention mechanism.

3.4. External Slot Relationship Memory

Despite the Slot-Context Attention layer extracting contextual information for each slot, the model still struggles to effectively capture the contextual information of slots that have co-reference or co-referential relationships due to the diverse expressions in natural language dialogues. Additionally, the Slot-Context Attention layer computes contextual relevance information for individual slots without considering the relationships between slots. Inspired by [

19], in this work, an External Slot Relationship Memory is constructed to capture the correlations between different slots. Two external memory units are treated as a dictionary of relationships between slots. Given a feature map

, it calculates the input features and the external memory unit

using the following equation:

Where M is a learnable parameter independent of the input, serving as a memory for capturing the relationships between multi-domain slot-related information. A is a relationship weight graph inferred from prior knowledge learned from multi-domain data. We utilize two separate memory processing units,

and

, as keys and values. The computational complexity of the external attention is O(dJN), where d and J are hyperparameters.

To filter out redundant information in slot relations, we adopt the double-normalization technique proposed in [

28], which normalizes both the feature rows and feature columns. The single external layer computation process can be described as follows:

And we utilize the Multi-head external layer, which is represented as follows:

Where

represents the index of the head, H represents the total number of heads, and

is a linear learnable parameter matrix.

The final slot vector representation is denoted as , where represents the representation of a specific slot information.

3.5. Slot Value Matching

Using Euclidean distance for value prediction of each slot: Normalize the slot feature vectors, calculate the distance between the feature vectors and the candidate values. Then, select the closest value for updating.

Where d(·) is the Euclidean distance function and

represents the value space for slot

. The training objective of this model is to maximize the joint objective accuracy of all slots, with the loss for each round being the negative log-likelihood sum.

4. Experiments

4.1. Datasets

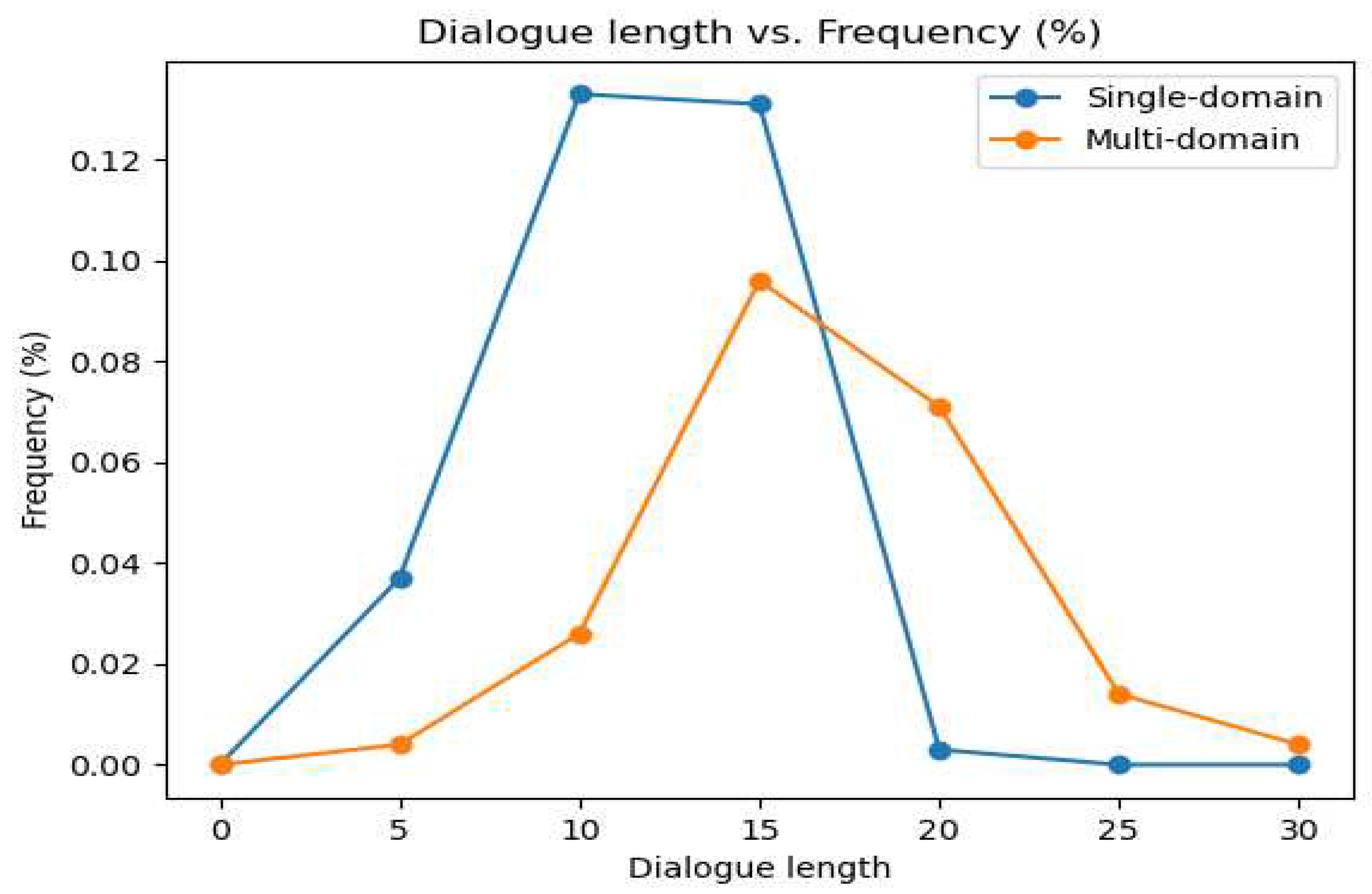

MultiWOZ is a task-oriented, multi-domain, manually annotated multi-turn dialogues dataset. It is currently the largest annotated dialogue dataset for task-oriented dialogue systems. The dataset consists of seven domains: attraction, hospital, police, hotel, restaurant, taxi, and train. It contains a total of 10,438 dialogue instances. Approximately 70% of the dialogues consist of more than ten turns, showcasing the complexity of the corpus. As shown in

Figure 2, the average number of turns for single-domain and multi-domain dialogues is 8.93 and 15.39, respectively, totaling 115,434 turns. MultiWOZ decomposes the dialogue modeling task into three subtasks to evaluate the quality of the dialogue model based on the performance of each subtask: dialogue state tracking, dialogue act-text generation, and dialogue context-text generation. In this paper, we experiment with the proposed ER-DST model using the MultiWOZ 2.0 [

9] and MultiWOZ 2.1 [

10] as the testing benchmarks.

4.2. Experimental Settings

The experiment used BERT-base-uncased to encoder the dialogue context. Additionally, another BERT-base-uncased model, which was not fine-tuned during training, was used to encode the slots and slot values. The Adam optimizer was employed for model training with a learning rate of 1e-4, a dropout rate of 0.1, a batch size of 64, and 16 epochs. The experimental code was developed and executed using Python 3.7.0 and PyTorch 1.7.1, with CUDA 11.1.0 utilized for accelerated training. We trained our model on the training set and employed early stopping based on the performance of the validation set. After completing the model training, we conducted a final performance evaluation on the test set.

4.3. Evaluation Metrics

In terms of evaluation metrics, we uses Joint Goal Accuracy (JGA) as the evaluation metric. JGA considers the model’s accuracy in predicting multiple goals, making it suitable for evaluating its ability to track multiple user goals in multi-turn dialogues. Specifically, for a dialogue system with N goals, the model needs to predict each goal’s slot values(e.g., date, time, location). JGA is calculated by evaluating the overall predictions of the model for all goals. A successful prediction is counted when all the predictions for all the goals are correct; otherwise, it is counted as a failure. Therefore, a higher JGA value indicates better performance in tracking dialogue states. Due to its challenging nature, JGA is considered a stringent metric, as it requires all the <domain, slot, value> triplets to be correctly predicted in each turn to consider the dialogue state prediction as correct.

4.4. Baseline Models

In order to demonstrate the effectiveness of our proposed method, we primarily compared it with four existing methods on the MultiWOZ dataset. Among them, CSFN-DST [

22] constructs a pattern graph to model the dependency relationships between slots and used BERT encoding for dialogue information. SOM-DST [

16] treats the dialogue state as a fixed-sized memory and selectively overwritten it at each turn. TripPY [

6] utilizes three mechanisms to obtain slot-value information. STAR [

8] uses self-attention to capture the relationships between slots.

Table 2 presents the methods available, allowing us to examine the effectiveness of our approach in modeling slot relationships for dialogue state tracking.

5. Experimental Results

5.1. Main Results

Table 3 presents the main results of our approach, where we compare ER-DST with several other state-of-the-art (SOTA) methods. Like these methods, we evaluate the performance of our model using Joint Goal Accuracy (JGA). ER-DST refers to our proposed model with the external slot relation memory. As shown in

Table 3, ER-DST achieves the significant performance on both datasets. On the MultiWOZ 2.0, our method achieves Joint Goal Accuracy of 54.76%. For the improved MultiWOZ 2.1, we achieve a Joint Goal Accuracy of 56.75%.

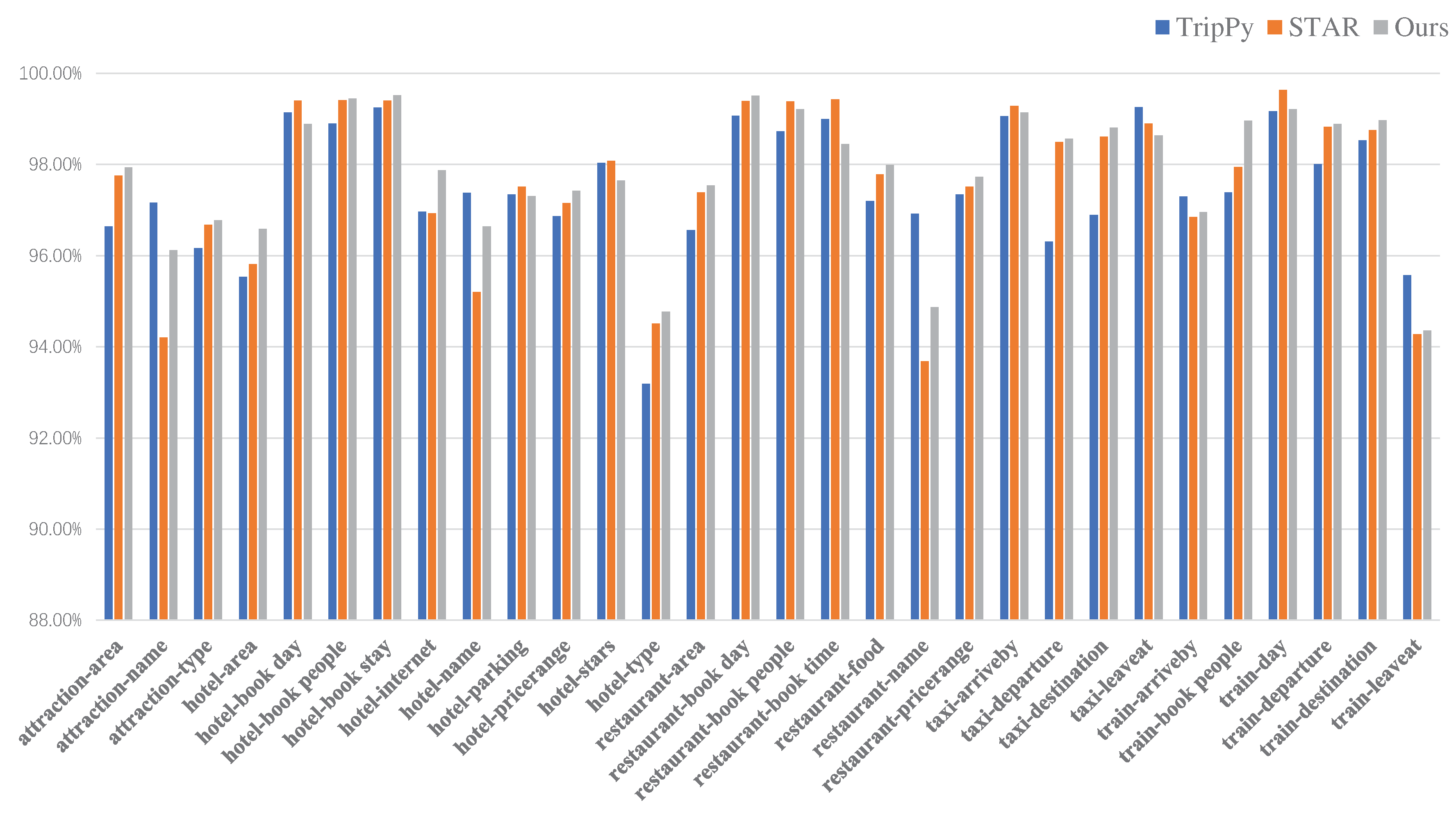

The experimental results of the ER-DST model and the baseline models on the specific domain slot accuracy in the MultiWOZ2.1 dataset are shown in

Table 4. It can be observed that ER-DST outperforms the STAR baseline model in the specific domains of Attraction, Hotel, and Taxi. ER-DST achieves the significant JGA in the domains of Hotel and Taxi, where the data is, relatively limited, with accuracies of 53.21% and 66.85% respectively. This is because ER-DST learns the most stable relationships between slots from the entire dataset, which optimizes the domains with initially fewer training samples.

5.2. Ablation Study

The purpose of this ablation experiment was to evaluate the impact of the external slot relationship memory component on the model’s performance and observe its effect on capturing slot relations.We designed four methods to evaluate the model’s performance. (1) Removing the slot relationship component. (2) Using self-attention alone to capture slot relations. (3) Incorporating layer normalization in the external slot relationship memory component. (4) Incorporating double-normalization in the external slot relationship memory component. We used the MultiWOZ 2.1 dataset for our experiments and employed the same train-validation-test split. The model architecture and hyperparameter settings remained consistent.

As shown in

Table 5, we observed the effectiveness of the external slot relationship memory in our model. On the other hand, the use of double-normalization to filter out irrelevant slot information had a significant impact on the external slot relation memory component.

5.3. Results Analysis

The experimental results of the ER-DST model and the baseline model on the MultiWOZ 2.1 dataset are shown in

Table 3. It can be observed that the ER-DST model outperforms the STAR baseline model in the Attraction, Hotel, and Taxi domains. Specifically, the ER-DST model achieves the significant JGA in the Hotel and Taxi domains, which have relatively fewer training samples, with accuracies of 53.21(%) and 66.85(%) respectively. Additionally,

Figure 3 displays the accuracy of the 30 specific slots in the entire MultiWOZ 2.1, where 17 slots achieve better results compared to the baseline. These results indicate that the proposed external slot memory in the ER-DST enhances the perception of slot relationships. However, for some slots with numerical values as values, such as time, there is still room for improvement for this type of non-enumerable slot.

6. Conclusions

Regarding the existing problems in multi-domain DST models: (1) Learning the relationships between multi-domain slots from a single sample reduces the model’s learning capacity and fails to capture the most important features between slots. (2) It is challenging to exclude irrelevant slot information, leading to redundant information. In this paper, we propose ER-DST, which leverages an external slot relation memory. In our approach, we first utilize an additional key-value memory to learn relationships between multiple domain slots from the entire dataset, which serves as a dictionary for slot relations. Then, we introduce a small constraint mechanism to reduce the weight of unrelated slot information. To evaluate the performance of our method, we conducted experiments on two large-scale, multi-domain task-oriented dialogue systems, MultiWOZ 2.0 and MultiWOZ 2.1. From the experimental results, it can be observed that the external slot relation memory has improved the model’s ability to predict slot values to some extent.

However, in our model, the slot-value matching approach is relatively limited, which can lead to missing slot values, especially for difficult-to-enumerate slot value types such as time, and for unseen domain and slot combinations. In future work, we plan to address this issue in the following ways: (1) by incorporating two approaches - selecting slot values from system responses and slot descriptions - to increase the flexibility of slot value selection and further enhance the model’s capability, and (2) by adopting slot value generation techniques to improve the model’s performance in few-shot and zero-shot scenarios. This will enable the model to effectively handle unseen domain and slot as well.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, X.X.; methodology, C.Y.; software, D.L.; validation, C.Y., D.L. and P.C.; formal analysis, X.Z.; investigation, D.T.; resources, P.C.; data curation, D.T.; writing—original draft preparation, C.Y.; writing—review and editing, X.X.; visualization, D.L.; supervision, X.X.; project administration, X.Z., Y.Y; funding acquisition X.Z.. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by the Scientific Research Foundation of Chongqing University of Technology (Grant No.2021ZDZ025) and Chongqing Technical Innovation and Application Development Special Project (cstc2021jscx dxwtBX0019).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Mrkšić, N.; Séaghdha, D.O.; Wen, T.H.; Thomson, B.; Young, S. Neural belief tracker: Data-driven dialogue state tracking. arXiv preprint 2016, arXiv:1606.03777 2016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhong, V.; Xiong, C.; Socher, R. Global-locally self-attentive encoder for dialogue state tracking. In Proceedings of the 56th Annual Meeting of the Association for Computational Linguistics (Volume 1: Long Papers); 2018; pp. 1458–1467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, H.; Lee, J.; Kim, T.Y. SUMBT: Slot-utterance matching for universal and scalable belief tracking. arXiv preprint 2019, arXiv:1907.07421 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nouri, E.; Hosseini-Asl, E. Toward scalable neural dialogue state tracking model. arXiv preprint 2018, arXiv:1812.00899 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, J.; Yang, Y.; Chen, C.; He, L.; Yu, Z. SAS: Dialogue state tracking via slot attention and slot information sharing. In Proceedings of the 58th annual meeting of the association for computational linguistics; 2020; pp. 6366–6375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heck, M.; van Niekerk, C.; Lubis, N.; Geishauser, C.; Lin, H.C.; Moresi, M.; Gašić, M. Trippy: A triple copy strategy for value independent neural dialog state tracking. arXiv preprint 2020, arXiv:2005.02877 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Ouyang, Y.; Chen, M.; Dai, X.; Zhao, Y.; Huang, S.; Chen, J. Dialogue state tracking with explicit slot connection modeling. In Proceedings of the 58th annual meeting of the association for computational linguistics; 2020; pp. 34–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, F.; Manotumruksa, J.; Zhang, Q.; Li, S.; Yilmaz, E. Slot self-attentive dialogue state tracking. In Proceedings of the Web Conference; 2021; 2021, pp. 1598–1608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Budzianowski, P.; Wen, T.H.; Tseng, B.H.; Casanueva, I.; Ultes, S.; Ramadan, O.; Gašić, M. MultiWOZ–a large-scale multi-domain wizard-of-oz dataset for task-oriented dialogue modelling. arXiv preprint 2018, arXiv:1810.00278 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eric, M.; Goel, R.; Paul, S.; Kumar, A.; Sethi, A.; Ku, P.; Goyal, A.K.; Agarwal, S.; Gao, S.; Hakkani-Tur, D. MultiWOZ 2.1: A consolidated multi-domain dialogue dataset with state corrections and state tracking baselines. arXiv preprint 2019, arXiv:1907.01669 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Henderson, M.; Thomson, B.; Williams, J.D. The second dialog state tracking challenge. In Proceedings of the 15th annual meeting of the special interest group on discourse and dialogue (SIGDIAL); 2014; pp. 263–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henderson, M.; Thomson, B.; Williams, J.D. The third dialog state tracking challenge. 2014 IEEE Spoken Language Technology Workshop (SLT); IEEE, 2014; pp. 324–329. [Google Scholar]

- Sun, K.; Chen, L.; Zhu, S.; Yu, K. The SJTU system for dialog state tracking challenge 2. In Proceedings of the 15th Annual Meeting of the Special Interest Group on Discourse and Dialogue (SIGDIAL); 2014; pp. 318–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henderson, M.; Thomson, B.; Young, S. Deep neural network approach for the dialog state tracking challenge. In Proceedings of the SIGDIAL 2013 Conference; 2013; pp. 467–471. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, C.S.; Madotto, A.; Hosseini-Asl, E.; Xiong, C.; Socher, R.; Fung, P. Transferable multi-domain state generator for task-oriented dialogue systems. arXiv preprint 2019, arXiv:1905.08743 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.; Yang, S.; Kim, G.; Lee, S.W. Efficient dialogue state tracking by selectively overwriting memory. arXiv preprint 2019, arXiv:1911.03906 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, S.; Sethi, A.; Agarwal, S.; Chung, T.; Hakkani-Tur, D. Dialog state tracking: A neural reading comprehension approach. arXiv preprint 2019, arXiv:1908.01946 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, P.; Hu, Q. An end-to-end approach for handling unknown slot values in dialogue state tracking. arXiv preprint 2018, arXiv:1805.01555 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, J.; Shuang, K.; Li, J.; Wang, Z.; Liu, Y. Beyond the Granularity: Multi-Perspective Dialogue Collaborative Selection for Dialogue State Tracking. arXiv preprint 2022, arXiv:2205.10059 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Devlin, J.; Chang, M.W.; Lee, K.; Toutanova, K. Bert: Pre-training of deep bidirectional transformers for language understanding. arXiv preprint 2018, arXiv:1810.04805 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Radford, A.; Wu, J.; Child, R.; Luan, D.; Amodei, D.; Sutskever, I.; others. Language models are unsupervised multitask learners. OpenAI blog 2019, 1, 9. [Google Scholar]

- Zhu, S.; Li, J.; Chen, L.; Yu, K. Efficient context and schema fusion networks for multi-domain dialogue state tracking. arXiv preprint 2020, arXiv:2004.03386 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Li, Q.; Wu, W.; Yin, Q. Generation and Extraction Combined Dialogue State Tracking with Hierarchical Ontology Integration. In Proceedings of the 2021 Conference on Empirical Methods in Natural Language Processing; 2021; pp. 2241–2249. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Y.; Zhao, J.; Bao, J.; Duan, C.; Wu, Y.; He, X. Luna: Learning slot-turn alignment for dialogue state tracking. arXiv preprint 2022, arXiv:2205.02550 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, Y.; Lipani, A.; Ye, F.; Zhang, Q.; Yilmaz, E. Dynamic schema graph fusion network for multi-domain dialogue state tracking. arXiv preprint 2022, arXiv:2204.06677 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiao, F.; Guo, Y.; Huang, M.; Nie, L. Enhanced Multi-Domain Dialogue State Tracker With Second-Order Slot Interactions. IEEE/ACM Transactions on Audio, Speech, and Language Processing 2022, 31, 265–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaswani, A.; Shazeer, N.; Parmar, N.; Uszkoreit, J.; Jones, L.; Gomez, A.N.; Kaiser, Ł.; Polosukhin, I. Attention is all you need. Advances in neural information processing systems 2017, 30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Li, Y.; Zhang, H.; Shan, Y. Towards real-world blind face restoration with generative facial prior. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition; 2021; pp. 9168–9178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).