1. Introduction

Problems related to pregnancy, labor, and childbirth are public health problems. Each year, they affect millions of women and increase mortality and morbidity worldwide [

1,

2]. Dysfunctional uterine contractions can lead to difficulties during labor, such as premature delivery, postpartum hemorrhage, uterine atony, and dystocia [

3]. Indeed, the success of modern drugs used for labor induction is demonstrated. However, they sometimes cause adverse effects on mothers and infants when it's not well managed [

4]. Kothari et al. report that despite the availability of modern drugs, many mothers-to-be, out of concern for perinatal complications or lack of means, use herbal medicines to induce labor [

5]. Thus, it is one of the common indications for herbal medicine [

6]. Therefore, scientific research for new safe and effective uterotonic and tocolytic agents arouses considerable interest in public health [

7]. In the literature, the contractile effect of certain plants commonly used to induce labor and facilitate delivery has been demonstrated, among others,

Matricaria chamomilla (Asteraceae) [

5],

Lannea acida (Anacardiaceae) [

8],

Ananas comosus (Bromeliaceae) [

9],

Jussiaea repens (Onagraceae) [

10].

Anastatica hierochuntica L. is commonly called « Rose de Jéricho » and growing in North Africa and the Middle East and used most of the time in difficult childbirth and uterine bleeding [

11]. Moreover, all parts or the whole plant of

A. hierochuntica are prescribed in folk medicine alone or in combination with other plants for the treatment of infertility, uterine bleeding, inflammation, pain, arthritis, diabetes, heart diseases, depression, high blood pressure, headache, menstrual problems, insufficient milk, the expulsion of the placenta or dead fetuses [

12]. Previous pharmacological studies have reported that

A. hierochuntica possesses anti-nociceptive, anti-inflammatory [

12], antioxidant, and cytotoxic activity against Hela and AMN-3 cancer cell lines [

11,

12,

13]. In addition to these effects, the aqueous extract of the plant increased the levels of hormones such as FSH, LH, and Prolactin [

14]. The hypoglycemic and hypolipidemic effects [

15,

16], and hepatoprotective activities of

A. hierochuntica were also demonstrated [

17]. Daur et al. showed that all parts of

A. hierochuntica are rich in essential minerals (Fe, Ca, Cr, Mn, Zn, Fe, Cu, Co) [

18]. Considering the prevalent use of this plant in traditional medicine and the lack of pharmacological study on the contractile properties in the uterus, this research investigated the contractile effects of the aqueous and hydroethanolic extract of the plant of

Anastatica hierochuntica L. during labor using an animal model. Acute toxicity and extracts potential effects on inflammation and oxidative stress have also been defined.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Chemicals and Reagents

Ethanol, Sulfuric acid, Chloroform, hydrochloric acid, Butanol, Methanol, Ethyl acetate, formic acid, Dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO), NEU reagent, aluminum trichloride, iron chloride, ferric trichloride, Folin Ciocalteu reagent (FCR), Mayer reagent, sodium phosphate dibasic, monobasic potassium phosphate, Dragendorff’s reagent, 15-lipoxygenase (EC 1.13.11.12), linoleic acid, boric acid, sodium tetraborate, sodium bicarbonate, potassium hexacyanoferrate, trichloroacetic acid (TCA), thiobarbituric acid (TBA), hydrogen peroxide solution, 2,2-diphenyl-β-picrylhydrazyl (DPPH), 2,2’-azino bis-[3-éthylbenzothiazoline-6-sulfonique] (ABTS), and potassium persulfate were purchased from Sigma–Aldrich (St. Louis, MO, USA). Reference substances: Ascorbic acid, gallic acid, tannic acid, catechin, quercetin, trolox, and zileuton were supplied by Sigma Aldrich. Silica gel TLC plates F 254 grade was from Macherey-Nagel (Germany).

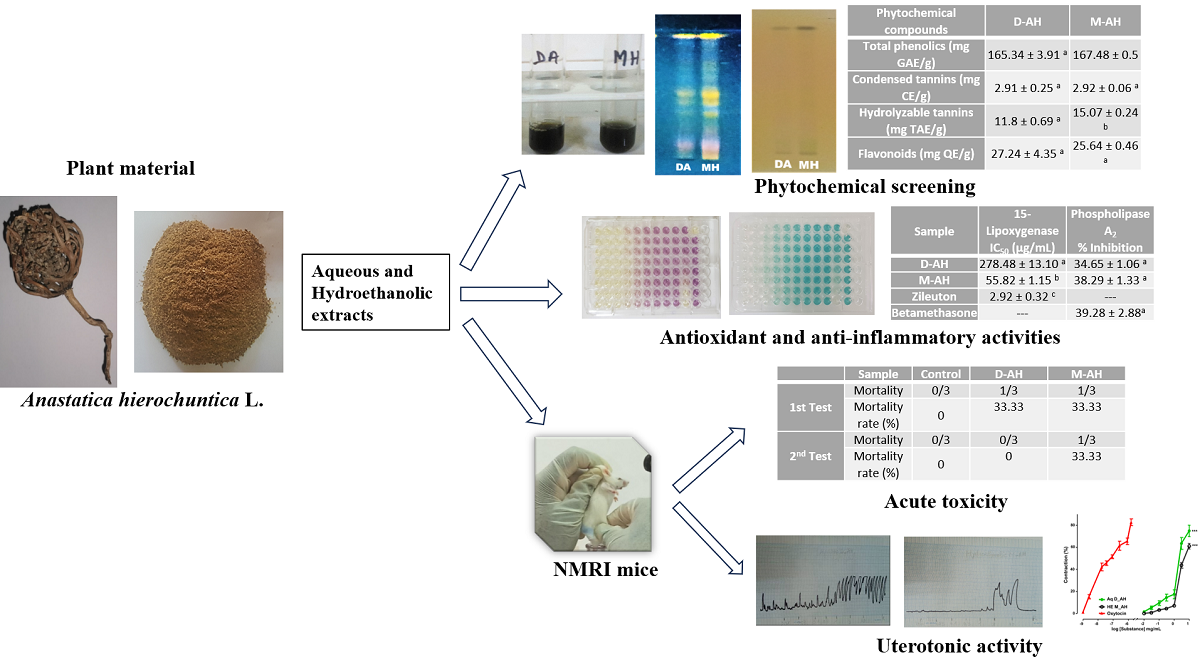

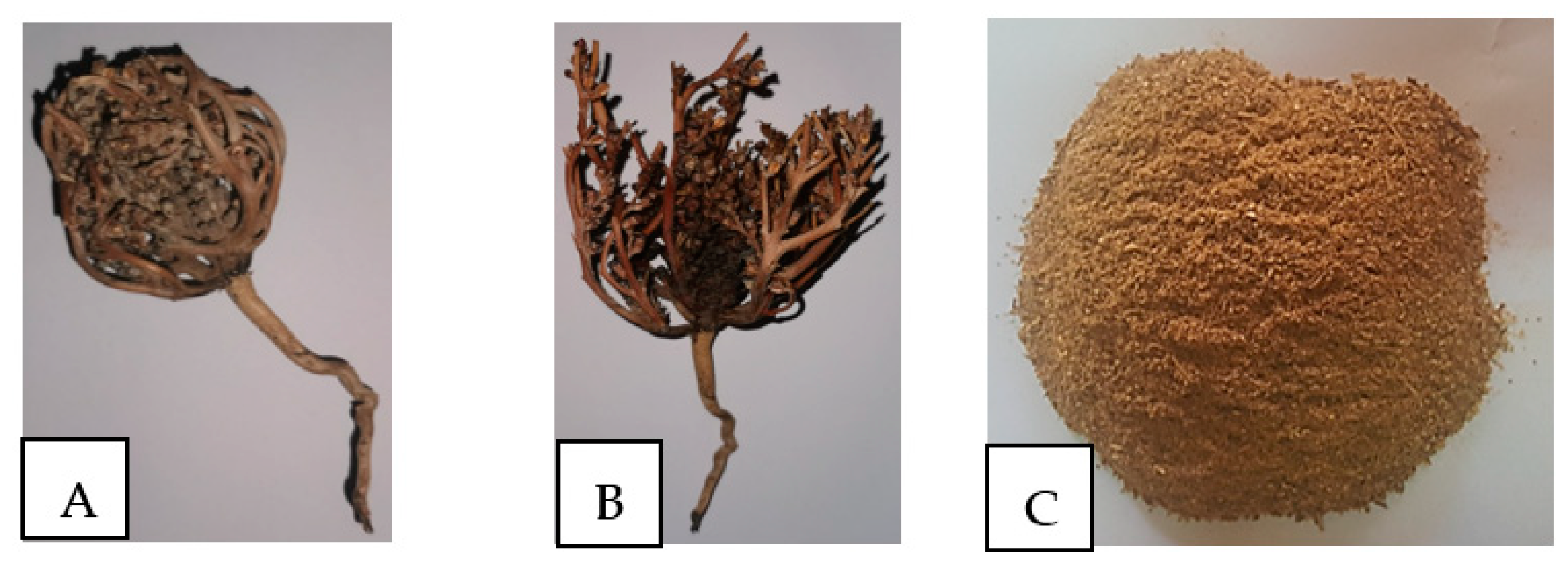

2.2. Plant Material

The plant material consisted of the whole dry plant of

Anastatica hierochuntica L. originally from the Asian continent, specifically Yemen. The plant was purchased in the Baskuy market in Ouagadougou (Burkina Faso). The herbal drug was kept away from dust and sunlight and then ground using a blade grinder (

Figure 1). The residual moisture content of the powder was determined according to the thermogravimetric method [

19].

2.3. Preparation of the Plant Extracts

Two extracts were prepared from the whole plant powder.

Aqueous decoction: 50 g of plant powder was dispersed in 500 mL of distilled water. After homogenization, the mixture was incubated for 15 min at room temperature and then boiled under reflux at 100˚C for 30 min. The cooled extract was filtered, frozen, and then freeze-dried to obtain the aqueous crude extract.

Hydroalcoholic maceration: 50 g of the vegetable powder was extracted in 500 mL of water and ethanol mixture in a proportion of 20: 80 (v/v). After 24 hours of mechanical stirring at room temperature, the extract was filtered, concentrated using a rotary evaporator (Rotavapor II), and lyophilized to get the hydro-ethanolic crude extract.

The extraction yield of the plant extracts was determined according to the following formula [

20]:

R: extraction yield (%), W: weight (g) of dry extract, W0: weight (g) of the crushed plant.

The two dried extracts after lyophilization were kept in a freezer until used for the biological tests.

2.4. Chemical Characterization Tests in Tubes

Chemical characterization tests of the crude aqueous and hydroethanolic extracts of

Anastatica hierochuntica were done to determine the presence or absence of various secondary metabolites, including phenolic compounds, tannins, flavonoids, alkaloids, saponins, coumarins, anthocyanosides, cardenolides and reducing compounds, using chemical characterization tests in tubes described by Ciulei [

21]. Different specific reagents were used to reveal these compounds.

2.5. High-Performance Thin-Layer Chromatography

High-performance thin-layer chromatography (HPTLC) was used to detect flavonoids and tannins in the extracts. It was carried out on chromatoplates (60 F254, 10 x 5 cm, glass support 10 x 20 cm, Merck) following the literature [

22]. Approximately 20 µL of each extract was streaked with a semi-automatic sample dispenser (CAMAG, Linomat 5, Switzerland) along the baseline 8 mm from the bottom edge of the plate. After deposition and drying, the plates were placed in a tank containing eluent previously saturated (20 × 10 cm, saturation time: 30 min). The solvent system used depended on the metabolite to be identified: Ethyl acetate/formic acid/H

2O, (80:10:10) for flavonoids and Ethyl acetate/formic acid/H

2O (18:2.4:2.1) for tannins. After migration over 8 cm in length, the plates were dried, and the Neu reagent for flavonoids and 5% FeCl

3 for tannins revealed the chromatographic profiles. The profiles were then observed under visible light and at UV wavelengths of 366 nm (only for the flavonoids).

2.6. Phenolic Compounds Content

2.6.1. Determination of Total Phenolics

Total phenolic content in the different extracts was determined using the Folin-Ciocalteu reagent (FCR) with slight modifications [

23]. Gallic acid was used as a reference compound to produce the standard curve. Briefly, 25 µL of sample at 1 mg/mL concentration of was mixed with 125 µL of FCR. 100 µL of 7.5% w/v sodium carbonate solution were added to the mixture. After one (1) h, the absorbance at 760 nm was measured using a microplate reader (Spectro UV, Epoch Biotek, USA). The results were expressed in mg of gallic acid equivalent (GAE) / g dry extract.

2.6.2. Determination of Total Hydrolyzable Tannins

The hydrolyzable tannins content was determined using tannic acid for the calibration curve with some modifications [

24]. 1 mL of each sample (5 mg/mL) was mixed with 5 mL of 2.5% w/v KIO

3. After 4 min, the absorbances at 550 nm were read (Shimadzu UV-Vis, Japan). The results were expressed in mg of tannic acid equivalent (TAE) / g of dry extract.

2.6.3. Determination of Total Condensed Tannins

The condensed tannins content was determined using catechin as the reference compound for the calibration curve [

25]. 500 µL of sample (5 mg/mL) was combined with 3 mL of 4% w/v vanillin solution and 1.5 mL of Hydrochloric acid. The mixture was incubated for 20 min at 20°C. The absorbances were recorded at 500 nm. The results were reported in mg of catechin equivalent (CE) per g of dry extract.

2.6.4. Determination of Total Flavonoids

Total flavonoid content was assessed using an aluminum chloride reagent [

26]. A standard calibration curve was plotted with quercetin as a reference. Briefly, 100 µL of each extract (1 mg/mL) was mixed with 100 µL of 2% w/v aluminum trichloride solution. After 10 min, the absorbance at 415 nm was measured with a spectrophotometer (Epoch Biotek, USA). The results were expressed in mg of quercetin equivalent (QE)/ g of dry extract.

2.7. Evaluation of Antioxidant Properties

2.7.1. 2,2-DPPH• Radical Scavenging Capacity

2,2-DPPH

• radical scavenging ability was assessed according to Adeyemi et al. using a microplate reader [

27]. On a 96-well microplate, 200 µL of a concentration of 0.004% freshly prepared DPPH in methanol was added to 100 µL of extracts and ascorbic acid at different concentrations. A spectrophotometer (Epoch Biotek Instruments, USA) was used to measure absorbances at 517 nm after incubation at room temperature in the dark for 30 min. The percent inhibition of the DPPH radical was calculated using the formula:

AE and AC represent the absorbances of extract/ascorbic acid and control (DPPH solution without sample).

The absorbance inhibition curve was drawn as a function of concentration for each extract or ascorbic acid to determine the 50% inhibitory concentration (IC50). The anti-radical power (ARP) was determined and defined as 1/IC50.

2.7.2. ABTS•+ Scavenging Capacity

The ability of the extracts to scavenge the ABTS radical cation was determined using the procedure of Re et al. [

28]. A solution of ABTS (7 mM) was prepared with potassium persulfate (2.45 mM). The mixture was kept away from light for 16 h. Subsequently, the solution was diluted with ethanol. Then, 200 µL of the diluted ABTS solution was added to 20 µL of sample solution at different concentrations (from a stock concentration of 1mg/mL) using a 96-well microplate. After 30 min of incubation in the dark, the absorbances were read at 734 nm by spectrophotometry (Epoch Biotek Instruments, USA). All the measurements were carried out in triplicate, and the percentage of inhibition was calculated according to the following formula:

AC: absorbance of the control (ABTS radical solution without sample); AE: absorbance of extract/ascorbic acid.

The IC50 and ARP were also determined.

2.7.3. Ferric-Reducing Power Assay

The reducing power was determined using potassium hexacyanoferrate [

29]. It measures the ability of extracts to reduce ferric iron to ferrous iron. Ferric iron, initially yellow, reduces and turns blue in proportion to the antioxidant activity. 1.25 mL of phosphate buffer (0.2 M, pH 6.6) and 1.25 mL of potassium hexacyanoferrate solution [K

3Fe (CN)

6] were added to 500 μL of extract at 1 mg/mL. The mixtures were incubated at 50°C in a water bath, and then 1.25 mL of trichloroacetic acid (10 %) was added. After centrifugation at 2000 rpm for 10 min, 625 µL of the supernatant was mixed with 625 µL of distilled water, followed by 125 µL of freshly prepared FeCl

3 (0.1 %). The spectrophotometer (Epoch Biotek Instruments, USA) was used for absorbances at 700 nm. The reducing potential of the extracts was expressed in millimole ascorbic acid equivalent (AAE) per 100g of dry extract.

2.7.4. Lipid Peroxidation Inhibition (LPO) Assay

The method described by Sombié et al. was used to assess the inhibitory capacity of lipid peroxidation activity [

30]. 1 mL of liver homogenate, 50 μL of FeCl

2 (0.5 mM), then 50 μL of H

2O

2 (0.5 mM) were added to 200 μL of extracts/ascorbic acid at a concentration of 1.5 mg/ mL of extracts or ascorbic acid (positive control). 1 mL of trichloroacetic acid (15%), then 1 mL of 2-thiobarbituric acid (0.67 %) were added after incubation at 37° C for 60 min. Subsequently, the mixture was incubated at 100°C for 15 min and centrifuged for 10 min at 2000 rpm. Absorbances were read at 532 nm with a spectrophotometer (Epoch Biotek Instruments, USA). All measurements were performed in triplicate.

The ability of the extracts to inhibit liver lipid peroxidation was expressed as a percentage of inhibition:

AC: absorbance of the control (without sample); AS: absorbance of extracts/ascorbic acid

2.8. Anti-Inflammatory Activity

2.8.1. Lipoxygenase Inhibition Assay

Lipoxygenase inhibition was determined using linoleic acid (1.25 mM) as substrate [

24]. The inhibitors (extracts/reference substance: zileuton) were prepared to obtain a final 100 μg/mL concentration. 146.25 μL of 15-lipoxygenase (820.51 U/ mL) solution was added to 3.75 μL of each inhibitor. Then, 150 μL of linoleic acid was added. A spectrophotometer (Epoch Biotek Instruments, USA) made it possible to measure the absorbances at 234 nm against blank without an enzyme. The tests were carried out in triplicate, and the percentage of lipoxygenase inhibition was calculated using the formula:

AE: Absorbance Enzyme test; AS: Absorbance Sample test

2.8.2. Phospholipase A2 (sPLA2) inhibition assay

Bee venom sPLA

2 activity was determined following the manufacturer instructions Abcam (Japan) described in catalog No. ab133089. A 96-well microplate was used to perform the sPLA

2 inhibition assay. For this purpose, a final concentration of 100 μg/mL of the extracts and ascorbic acid (reference compound) was used. The absorbances were read by spectrophotometry (Agilent 8453) at 415 nm against a blank that had not received the enzyme. The experiment was performed in triplicate, and the percentage inhibition of sPLA

2 at 100 μg/mL was calculated using the following formula:

AE: Absorbance Enzyme test; AS: Absorbance Sample test

2.9. Experimental Animals

Female NMRI mice weighing 27 ± 5 g were obtained from the Institute of Research in Health Sciences animal facility. All animals were maintained in a suitable environment (temperature of 20-25°C, 12 h/12 h light/dark cycle, and humidity of 60%) and nutritional (free access to food and water) conditions throughout the experiments. The experiments were conducted following the regulations on the care of laboratory animals defined by the Guide for the Care and Use of laboratory animals [

31] and validated by IRSS “Institut de Recherche en Sciences de la Santé” [

32].

2.10. Acute General Toxicity

The acute general toxicity test was conducted on mice under the Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development Guidelines 423 [

33]. Indeed, the treated mice received a single dose of 2000 mg/kg of each extract by gavage. The control group of mice received distilled water. After administering the extracts, the mice were observed for the first two hours to note the various symptoms of toxicity, then daily for 14 days. The animals were weighed on the first, second, third, seventh, and fourteenth days.

2.11. Evaluation of the Contractile Effect

2.11.1. Isolated Mouse Uterus Preparation

A mouse uterus was prepared according to the procedure described by [

8]. After cervical dislocation, the mice uteri were collected and promptly removed. Then, the connective tissue was cleaned and cut into strips about 1.5 cm. Each uterine strip was vertically mounted in an organ bath of 25 mL capacity containing fresh Tyrode solution of the following composition (mM): NaCl 118, KCl 4.7, NaHCO

3 25, CaCl

2 1.25, MgSO

4 7H

2O 1.4, KH

2PO

4, and Glucose 10, and thermostated at 37 °C. Strip tension was adjusted to 1 g, and the Tyrode solution was changed every 15 min for 45 min of equilibration. The potassium chloride (80 mM) test was carried out to check compliance with maximum contractility. Spontaneous and drug-induced myometrial contractions were recorded using an isometric force transducer (Harward dual-channel oscillograph recorder) connected to an amplifier (Harward Transducer type) and displayed on a monitor.

2.11.2. Drug Challenges

After equilibration, during which spontaneous contractions were saved, non-cumulative stimulation was noted for 5 min with potassium chloride (80 mmol/L). Before the start of each stimulation, the tissue was left to rest for 15 min after being washed by changing the bath solution. After observation of the regularity of the contractile activity of the uterus, oxytocin (2.5×10-9 – 1.56×10-6 mg/mL) and the two extracts (aqueous and hydroethanolic) of Anastatica hierochuntica (10-2 – 10 mg/mL) were tested by the administration in cumulative concentration. Before trying a new extract (drug), the organ bath was rinsed three (3) times and tested with KCl. The contractions were then related to the size of each ring at the end of the experiment. The experiment was repeated five times.

2.12. Statistical Analysis

Values are given as arithmetic means ± S.E.M. The significance of differences between means was conducted by GraphPad Prism in version 8.4.3, and ANOVA was followed by Dunnett and Tukey's multiple comparison tests for comparisons. The difference was considered statistically significant for a threshold of p-value < 0.05.

3. Results

3.1. Preliminary Phytochemical Investigation

3.1.1. Phytochemical Screening

The results of the yield of extracts, the residual moisture of powder, and the phytochemical analysis of hydroethanolic and aqueous extracts of A. hierochuntica are summarized in

Table 1. Steroids, triterpenes, flavonoids, coumarins, saponins, reducing compounds, and tannins were detected in all the extracts, while anthracenosides, cardenolides, and alkaloids were not.

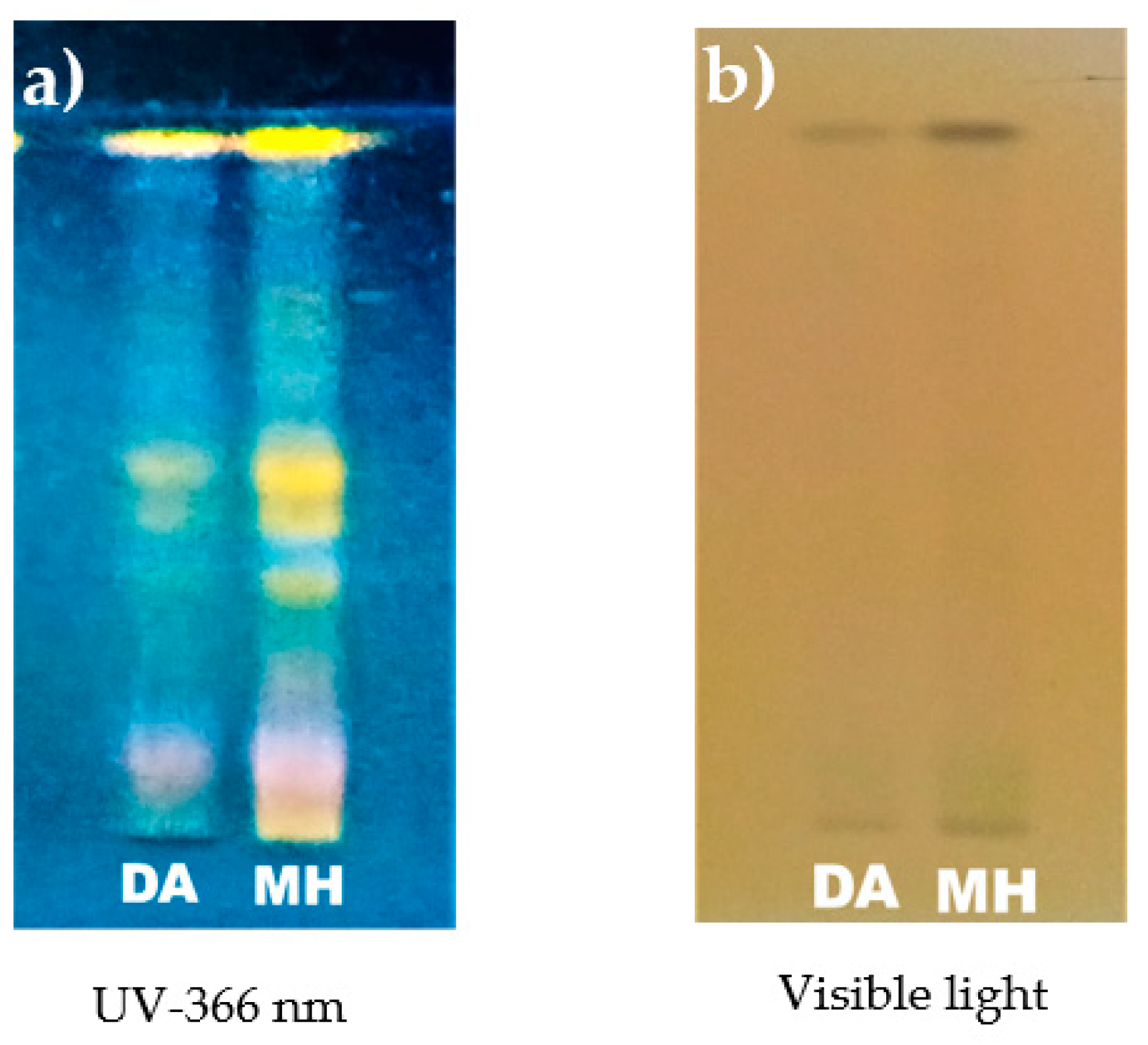

As shown in

Figure 2, the screening by TLC reveals the presence of flavonoids by the vision of yellow, yellow-orange, and sky-blue colorations and for the tannins by the appearance of black coloration.

3.1.2. Contents of Total Phenolics, Tannins, and Flavonoids

Table 2 presents the contents of total phenolics, condensed tannins, hydrolyzable tannins, and flavonoids contained in the two aqueous and hydroethanolic extracts of the whole

Anastatica hierochuntica L. The hydroethanolic extract has a higher content of hydrolyzable tannins than the aqueous decoction.

3.2. Biological Activities

3.2.1. Antioxidant Activity

The extracts of A. hierochuntica exhibited antioxidant activity, as indicated in

Table 3. The free radical scavenging ability of extracts was assessed using the DPPH and ABTS radical scavenging assays. Overall, the samples (extracts and ascorbic acid) were more active on ABTS than on DPPH radicals. In both tests, the reference substance was statistically better than the extracts (p < 0.05). The hydroethanolic extract was better than the aqueous extract in the DPPH anti-radical test. However, the opposite is observed in the case of the ABTS test. The ferric ion reduction capacity (FRAP) of the extracts varied from 12.6 ± 0.34 (aqueous extract) to 13.56 ± 0.43 mmol EAA/100g (hydroethanolic extract). Statistical data analysis did not show any significant difference between the two extracts. The lipid peroxidation inhibitory power of the extracts was expressed as a percentage (%) ranging from 66.97 ± 1.46 for the aqueous decoction to 73.97 ± 1.03 for the hydroethanolic maceration. These values are lower than ascorbic acid (reference substance), which had 94.95 ± 0.94% inhibition.

3.2.2. Anti-Inflammatory Activity

The evaluation of the anti-inflammatory activity of the extracts by inhibiting15-lipoxygenase and phospholipase A

2 are recorded in

Table 4. The results showed that the hydroethanolic extract exhibited the highest inhibitory effect (IC

50 = 55.82 ± 1.15) on 15-lipoxygenase. The aqueous extract showed weak anti-lipoxygenase activity (IC

50 = 278.48 ± 13.10). However, the Zileuton used as a reference compound in this inhibition test presented a better IC

50 (2.92 ± 0.32) than the extracts. The evaluation of the effect of the extracts on the activity of phospholipase A

2 expressed as a percentage of inhibition shows that there was no statistical difference between the extracts and Betamethasone (reference substance).

3.2.3. Acute Toxicity

Administration of

Anastatica hierochuntica extracts (aqueous and hydroethanolic) at 2000 mg/kg showed that during the first thirty minutes following administration, rapid breathing and drowsiness were observed in all mice. The somnolence persisted after one hour in the mice receiving the aqueous decoction.

Table 5 presents the toxicity test results concerning the mortality rate after 14 days of observation. The evaluation of the acute oral toxicity indicates that, in the first test, 48 hours after administration of the extracts, two mice deaths were noted, namely one in the batch having received the aqueous extract and the other hydroethanolic extract. For the second test, death was registered 24 hours later in the group receiving the hydroethanolic extract. According to OECD, the 50% lethal dose (LD

50) of the M-AH and D-AH were estimated respectively at 2500 mg/kg bw and 5000 mg/kg bw.

The weight of the animals recorded on the day of administration of the extracts (D0), the first three consecutive days (D1, D2, D3), a week (D7), and two weeks (D14) later were presented in

Table 6. During the test, a progressive increase in the body weight value of the mice in all groups was observed during the 14 days.

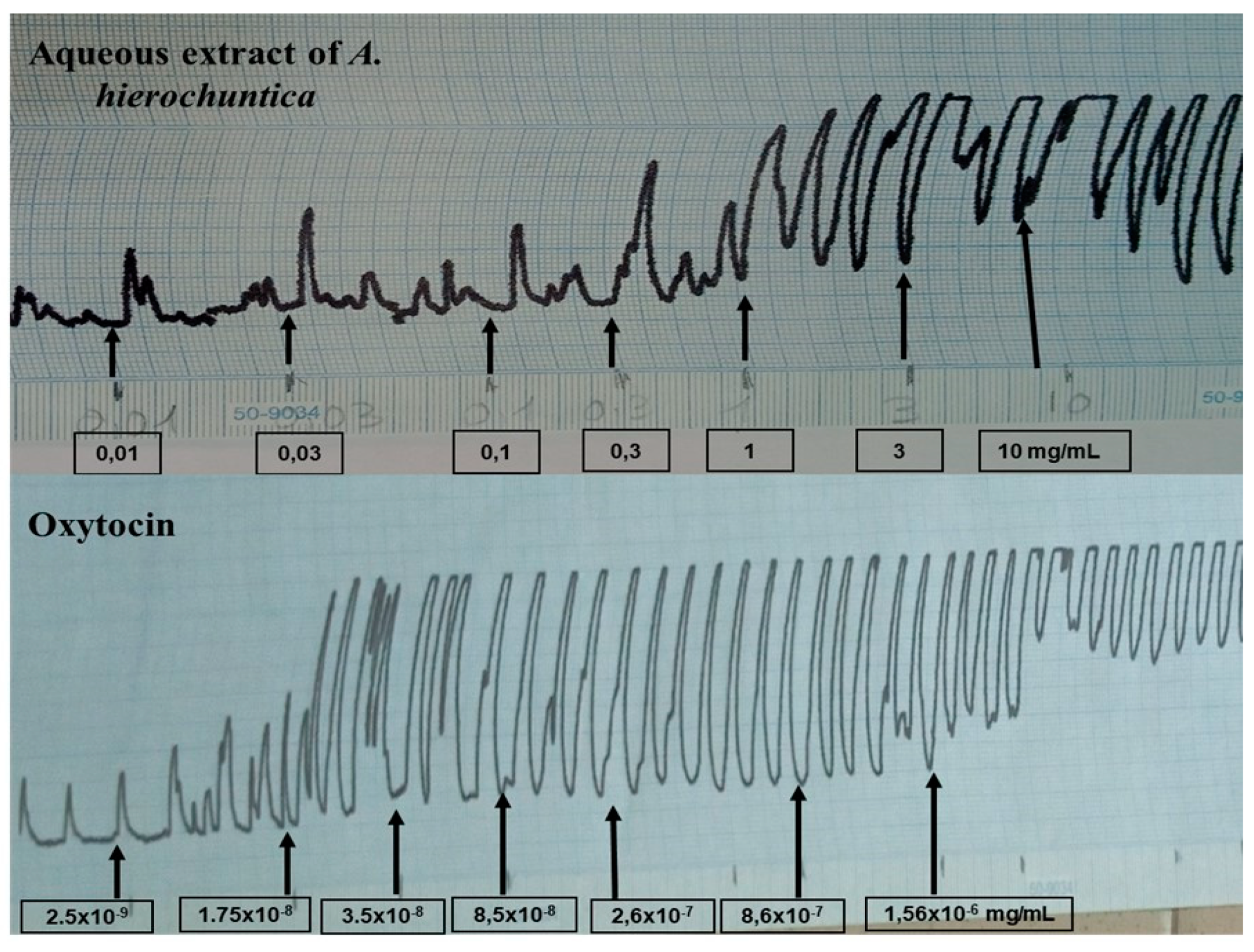

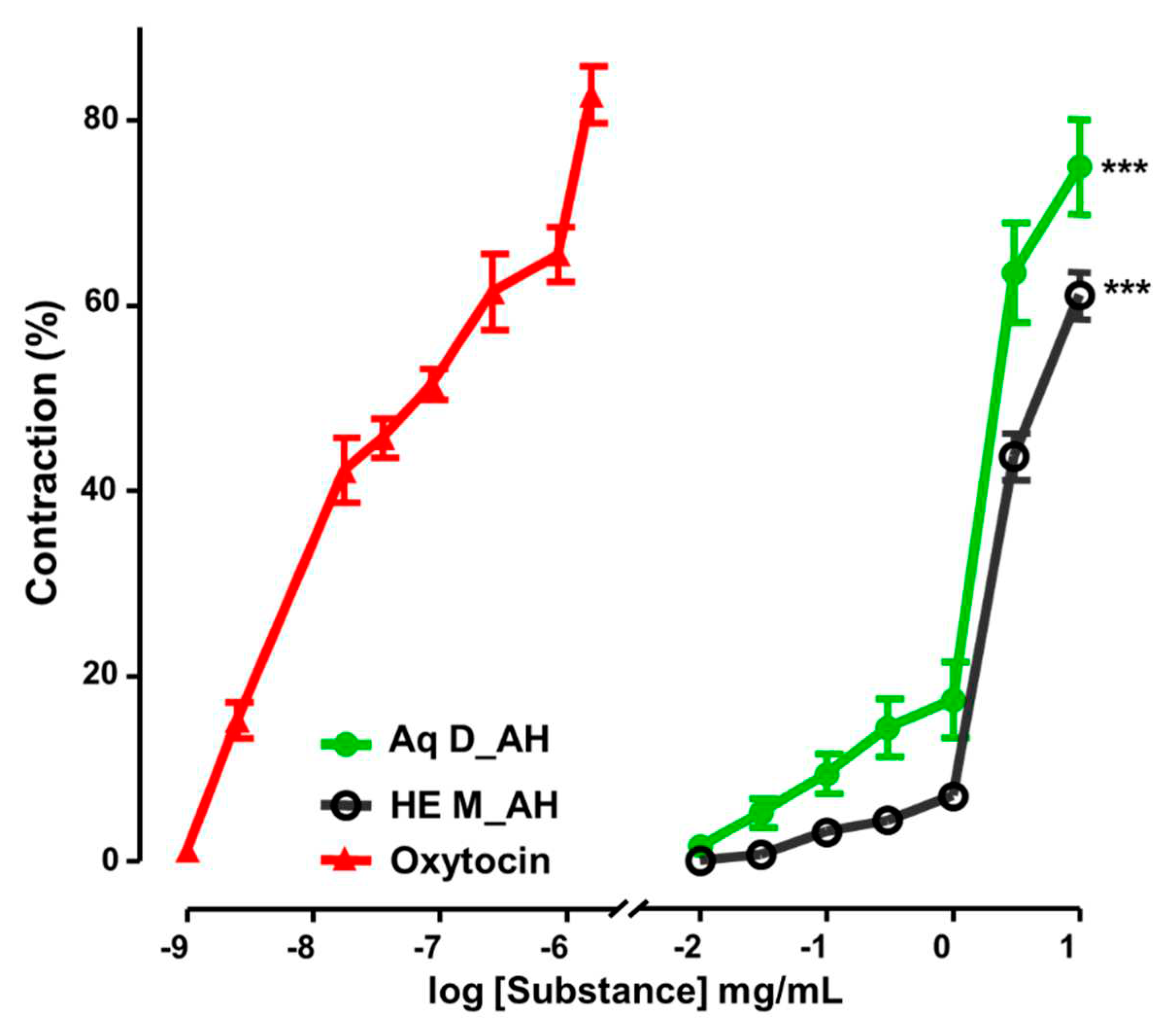

3.2.4. Uterine Contractility Effects of Extracts

Aqueous and hydroethanolic extracts of

Anastatica hierochuntica induced contraction of the uterine rings in a concentration-dependent manner. In contrast to the hydroethanolic extract, a more powerful and effective contractile effect was observed with the aqueous extract (

Figure 3) after cumulative administration in the single-organ tank.

The force of contraction increased progressively after administering both sections, but this vasoconstriction was less than that of oxytocin at low concentrations (

Figure 4). In addition, the most potent of the three substances capable of producing an amplitude of contraction of one cm at 50% effective concentrations (EC

50) was oxytocin (5.33×10

-8 ± 0.32 mg/mL), followed by the aqueous extract (1.51 ± 0.08 mg/mL) and finally the hydroethanolic extract (3.57 ± 0.61 mg/mL) (

Figure 5a). As for the efficacy of the substances, the maximum effects were 2.91 ± 0.21 A (cm)/uterus(cm), 1.84 ± 0.79 A (cm)/uterus (cm), and 2.30 ± 0.34 A (cm)/uterus (cm), respectively for oxytocin, aqueous extract, and hydroethanolic extract (

Figure 5b).

4. Discussion

Medicinal plants have been used for decades as first-line treatment despite various modern drugs [

34].

Anastatica hierochuntica is one of them, much women use for childbirth difficulties [

35]. The current study was to provide scientific evidence for this claim about the widespread use of the plant as a stimulant that can facilitate the labor of pregnant women. The residual moisture content of the whole plant powder was determined before the start of this work, and it was less than 10%. This suggests that the herbal drug was well preserved and protected from fermentations, proliferation of microorganisms, and degradation of phytochemicals [

19,

36]. Phytochemical investigations of both extracts show that the plant contains flavonoids, tannins, triterpenoids, steroids, coumarins, and saponins (Table1). The results demonstrated a moderate anti-free radical effect and a great inhibiting capacity of lipid peroxidation and phospholipase of the aqueous and hydroethanolic extracts (

Table 3). It is well-established that secondary metabolites in plant extracts are responsible for many therapeutic properties [

37]. That could justify the multiple uses of

A. hierochuntica in traditional medicine. The study that evaluated the safety made it possible to estimate the LD

50 of the hydroethanolic extract at 2500 mg/kg of bw and 5000 mg/kg bw for aqueous extract.

The myometrium remains a therapeutic target for inducing labor and managing preterm labor and postpartum hemorrhage [

7]. Indeed, one of the screening tools for exploring and creating new effective uterotonics and tocolytics is the study of contractile effects

ex vivo using myometrial tissue in organ baths [

38]. For ethical reasons regarding experimentation on pregnant women, uterine biologists mainly use animal models, namely rats, mice, and guinea pigs [

3]. The present study reports the possible contractile effects of whole

Anastatica hierochuntica on the myometrium of the NMRI mice model for the first time. The results showed that the aqueous and hydroethanolic extracts induce a spasmodic effect on the uterine tissue of mice. The aqueous extract exhibited the more potent and effective of the two extracts (

Figure 5).

This efficiency may be due, on the one hand, to the nature of the solvents and the extraction method. Many active constituents were easily extractable in water [

39]. On the other hand, the aqueous extract had the lowest anti-lipoxygenase activity, which may be beneficial in the induction of contraction. Corriveau et al. report that inhibiting lipoxygenase and cyclooxygenase leads to the reduction of contractions in vitro in pregnant women's myometrium [

40]. Leukotrienes (lipoxygenase products) have also been shown to be involved in the contractility of the porcine uterus [

41]. In addition, the contractile effects of the extracts were compared to the contractile effect of oxytocin, a powerful uterine contraction hormone. At low concentrations, oxytocin was more potent than extracts (

Figure 5). The exogenous oxytocin used in this study was a pure compound that could explain the more significant contraction. Indeed, oxytocin is synthesized by the hypothalamus and secreted mainly by the posterior pituitary and other tissues, such as the placenta, the corpus luteum, and the uterus [

42]. Oxytocin is synthesized by the hypothalamus and has a neuromodulatory action in the brain and a hormonal action on various peripheral tissues [

43]. It has a uterotonic action in the uterus by stimulating its receptors (OXTRs) and plays an essential role during parturition [

44]. In our study, the extracts induced concentration-dependent contraction like oxytocin (

Figure 4). However, the lack of other agonists (acetylcholine, histamine, etc.) and antagonists (atropine, etc.) limits the determination of the pharmacological targets involved in these spasmodic effects. However, this plant is traditionally used by women to facilitate childbirth. This suggests that the extracts partly stimulate OXTRs to increase contractions. Some researchers have hypothesized that the most crucial function of oxytocin is to increase the production of prostaglandins (potent inducers of uterine contractions) by inducing the expression of COX-2 via the activation of the pathway MAPK [

3,

45]. Astutik et al. demonstrated that administration of the hydroethanolic extract of

Anastatica hierochutica to pregnant mice leads to increased prostaglandin levels of PGE2 and PGF2α [

46]. Tannins, flavonoids, and saponins were highlighted in uterotonic plants. Tannins affect calcium availability to uterine tissue and heart muscle contraction, and flavonoids by direct action on estrogen receptors to cause uterine contraction [

47]. Thus, the pharmacological effect of the extracts from

A. hierochuntica on uterine contraction could be explained by the presence of secondary metabolites.

This plant could provide relief during childbirth in environments where women cannot access health services. Research into the molecules responsible for spasmodic uterine effects could also pave the way for new and existing remedies. However,

A. hierochuntica should not be used by women during pregnancy, as they can cause abortions, especially as they have spasmodic effects. Studies have warned against using certain plants during conception and pregnancy [

47].

5. Conclusions

The present research findings provide scientific evidence for obstetrical uses of Anastatica hierochuntica L. to induce or accelerate labor. This suggests that its intake is contraindicated during pregnancy. In the future, more research is needed to describe the aqueous extract mechanism of action on uterine contractility.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, W.L.M.E.B-K., B.S.O., E.K., and N.O.; Formal analysis, T.K.T.; Investigation, W.L.M.E.B-K., B.S.O., O.M.N., B.Y., B.K., and G.S.; Methodology, W.L.M.E.B-K., M.N., B.S.O., O.M.N., and B.Y.; Resources, N.O.; Supervision, N.O.; Validation, M.N., M.K., S.I., M.O., and N.O.; Writing – original draft, W.L.M.E.B-K.; Writing – review & editing, W.L.M.E.B-K., M.N., M.O., E.K., and N.O. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The experiments were conducted following the regulations on the care of laboratory animals defined by the 8th Edition of Guide for the Care and Use of laboratory animals and validated by Health science research institute (IRSS/Burkina Faso).

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable

Data Availability Statement

All data are available in the manuscript.

Acknowledgments

We thank “Laboratoire de Recherche-Développement de Phytomédicaments et Médicaments (LR-D/PM) / Institut de Recherche en Sciences de la Santé (IRSS)” and “Centre de Formation, de Recherche et d’Expertises en Sciences du Médicament” (CEA-CFOREM) that supported this research.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Creanga, A.A.; Syverson, C.; Seed, K.; Callaghan, W.M. Pregnancy-related mortality in the United States, 2011–2013. Obstet Gynecol. 2017, 130, 366–373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Say, L.; Chou D Gemmill, A.; Tunçalp, Ö.; Moller, A.; Daniels, J.; Gülmezoglu, A.M.; Temmerman, M.; Alkema, L. Global causes of maternal death: a WHO systematic analysis. Lancet Glob Health. 2014, 2, e323–e333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Malik, M.; Roh, M.; England, S.K. Uterine contractions in rodent models and humans. Acta Physiol. 2021, 231, e13607.

- Page, K.; McCool, W.; Guidera, M. Examination of the pharmacology of oxytocin and clinical guidelines for use in labor. J Midwifery Womens Health. 2017, 62, 425–433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kothari, B.; DeGolier, T. The contractile effects of Matricaria chamomilla on Mus musculus isolated uterine tissue. J. pharmacogn. Phytochem. 2022, 11, 303–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zamawe, C.; King, C.; Jennings, H.; Mandiwa, C.; Fottrell, E. Effectiveness and safety of herbal medicines for induction of labour: A systematic review and metaanalysis. BMJ Open. 2018, 8, e022499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siricilla, S., Iwueke, C.C.; Herington, J.L. Drug discovery strategies for the identification of novel regulators of uterine contractility. Curr Opin Physiol. 2020, 13, 71–86. [CrossRef]

- Ngadjui, E.; Kouam, J.Y.; Fozin, G.R.B.; Momo, A.C.T.; Deeh, P.B.D.; Wankeu-Nya, M.; Nguelefack, T.B.; Watcho, P. Uterotonic Effects of Aqueous and Methanolic Extracts of Lannea acida in Wistar Rats: An In Vitro Study. Reprod Sci. 2021, 28, 2448–2457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monji, F.; Adaikan, P.G.; Lau, L.C.; Bin-Said, B.; Gong, Y.; Tan, H.M.; Choolani, M. Investigation of uterotonic properties of Ananas comosus extracts. J Ethnopharmacol. 2016, 193, 21–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chakraborty, I.; Ghosal, S.; Pradhan, N. Jussiaea repens (L) acts as an uterotonic agent - an in vitro study. Int J Pharm Sci Rev Res. 2015, 27, 368–72. [Google Scholar]

- Abou-Elella, F.; Hanafy, E.A.; Gavamukulya, Y. Determination of antioxidant and antiinflammatory activities, as well as in vitro cytotoxic activities of extracts of Anastatica hierochuntica (Kaff Maryam) against HeLa cell lines. J Med Plants Res. 2016, 10, 77–87. [Google Scholar]

- Alatshan, A.; Esam, Q.; Wedyan, M.; Bseiso, Y.; Alzyoud, E.; Banat, R.; Alkhateeb, H. Antinociceptive and Antiinflammatory Activities of Anastatica hierochuntica and Possible Mechanism of Action. Indian J. Pharm. Sci. 2018, 80, 637–646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohammd, T.U.; Baker, R.K.; Al-Ameri; K.A.H.; Abd-Ulrazzaq, S.S. Cytotoxic Effect of Aqueous Extract of Anastatica hierochuntica L. on AMN-3 Cell Line in vitro. Adv. life sci. technol. 2015, 31, 59–63.

- Baker, R.K.; Mohammd, T.U.; Ali, B.H.; Jameel, N.M. The Effect Of Aqueous Extract Of Anastatica Hierochuntica On Some Hormones In Mouse Females. Ibn al-Haitham j. pure appl. sci. 2017, 26, 198–205. [Google Scholar]

- Rahmy, T.R.; El-Ridi, M.R. Action of Anastatica hierochuntica plant extract on Islets of Langerhans in normal and diabetic rats. Egypt. J. Biol. 2002, 4, 87–94. [Google Scholar]

- Feryal, S.; Hasan, F.A.; Ali, S.M. Effect of alcoholic Anastatica hierochuntica extract on some biochemical and histological parameters in alloxan induced diabetic rats. Iraqi J. Sci. 2011, 52, 445–455. [Google Scholar]

- Yoshikawa, M.; Xu, F.; Morikawa, T.; Ninomiya, K.; Matsuda, H. Anastatin A and B, new skeletal flavonoids with hepatoprotective activities from the desert plant Anastatica hierochuntica. Bioorganic Med. Chem. Lett. 2003, 13, 1045–1049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daur, H. Chemical properties of the medicinal herb Kaff Maryam (Anastatica hierochuntica L.) and its relation to folk medicine use. Afr. J. Microbiol. Res. 2012, 6, 5048–5051. [Google Scholar]

- Boly, R.; Yabre, Z.; Nitiema, M.; Yaro, B.; Yoda, J.; Belemnaba, L.; Ilboudo, S.; Youl, N.H.E.; Guissou, I.P.; Ouedraogo, S. Pharmacological Evaluation of the Bronchorelaxant Effect of Waltheria indica L. (Malvaceae) Extracts on Rat Trachea. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med. 2021, 2021, 5535727. [Google Scholar]

- Parker, J.E.; Chimere, U.Y.; Chinenye, N.P.; Uzoma, I.; Echezona, E.; Innocent, O.O.; Paul, N.A.C. Phytochemical and toxicological studies of methanol and chloroform fractions of Acanthus montanus leaves. J. Biol. Sci. 2021, 21, 52–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ciulei, I. Methodology for Analysis of Vegetable Drugs. Practical Manual on the Industrial Utilisation of Medicinal and Aromatic Plants, Ed. Ministry of chemical industry, Romania, 1982; pp. 1-62.

- Ouedraogo, W.R.C.; Belemnaba, L.; Nitiema, M.; Kabore, B.; Ouedraogo, N.; Koala, M.; Semde, R.; Ouedraogo, S. Antioxidant and Vasorelaxant Properties of Phaseolus vulgaris Linn (Fabaceae) Immature Pods Extract on the Thoracic Aorta of NMRI Mice. Biomed Pharmacol J. 2023, 16, 533–548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nitthikan, N.; Leelapornpisid, P.; Naksuriya, O.; Intasai, N.; Kiattisin, K. Potential and Alternative Bioactive Compounds from Brown Agaricus bisporus Mushroom Extracts for Xerosis Treatment. Sci. Pharm. 2022, 90, 59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belem-Kabré, W.L.M.E., Kaboré B, Compaoré-Coulibaly A., Traoré T.K., Thiombiano E.A.M., Nebié-Traoré M., Compaoré M., Kini F.B., Ouédraogo S., Kiendrebeogo M., Ouédraogo N., Phytochemical and biological investigations of extracts from the roots of Cocos nucifera L. (Arecaceae) and Carica papaya L. (Caricaceae), two plants used in traditional medicine, Afr. J. Biochem. Res. 2021, 15, 28-35.

- Kaboré, B.; Koala, M.; Ouedraogo, C.W.R.; Belemnaba, L.; Nitiema, M.; Compaoré, S.; Ouedraogo, S.; Ouedraogo, N.; Dabiré, C.M.; Kini, F.B.; Palé, E.; Ouedraogo, S. High-Performance Thin-Layer Chromatography Phytochemical Profiling, Antioxidant Activities, and Acute Toxicity of Leaves Extracts of Lannea velutina A. Rich. J. Med. Chem. Sci., 2023, 6, 410–423. [Google Scholar]

- Arvouet-Grand, A.; Vennat, B.; Pourrat, A.; Legret, P. Standardisation d’un extrait de Propolis et identification des principaux constituants. J Pharm Belg. 1994, 49, 462–468. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Adeyemi, J.O. In Vitro Cytotoxicity and Antioxidant Studies of Dovyallis caffra-Mediated Cassiterite (SnO2) Nanoparticles. Sci. Pharm. 2023, 91, 34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Re, R.; Pellegrini, N.; Poteggent, A.; Pannala, A.; Yang, M.; Rice-Evans, C. Antioxidant activity applying an improved ABTS radical cation decolorization assay. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 1999, 26, 1231–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moualek, I.; Aiche, G.I.; Guechaoui, N.M.; Lahcene, S.; Houali, K. Antioxidant and anti-inflammatory activities of Arbutus unedo aqueous extract. Asian Pac J Trop Biomed. 2016, 6, 937–944. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sombié, E.N.; Traoré, T.K.; Derra, A.N.; N’do, J.Y.P.; Belem-Kabré, W.L.M.E.; Ouédraogo, N.; Hilou, A.; Tibiri, A. Anti-Fibrotic Effects of Calotropis procera (Ait.) R.Br Roots Barks against Diethylnitrosamine-Induced Hepatic Fibrosis in Rats. J. Biosci. Med. 2023, 11, 332–349. [Google Scholar]

- National Research Council (US) Committee for the Update of the Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals. Guide For the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals, 8th Ed.; National Academies Press, Washington, 2011; 246p.

- Nitiéma, M.; Ilboudo, S.; Belemnaba, L.; Ouédraogo, G.G.; Ouédraogo, S.; Ouédraogo, N.; Ouedraogo, S.; Guissou, I.P. Acute and sub-acute toxicity studies of aqueous decoction of the trunk barks from Lannea microcarpa Engl. and K. Krause (Anacardiaceae) in rodents. World j. pharm. pharm. Sci. 2018, 7, 30–42. [Google Scholar]

- OECD/OCDE, Guidelines for the testing of chemicals. Guideline 423: Acute oral toxicity-Acute toxic class

method. revised method adopted 17th December 2001, Section 4.; 2001; pp. 1-14.

- Omwenga, E.O.; Hensel, A.; Pereira, S.; Shitandi, A.A.; Goycoolea, F.M. Antiquorum sensing, antibiofilm formation and cytotoxicity activity of commonly used medicinal plants by inhabitants of Borabu sub-county, Nyamira County, Kenya. Plos one. 2017, 12, e0185722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Md Zin, S.R.; Kassim, N.M.; Mohamed, Z.; Fateh, A.H.; Alshawsh, M.A. Potential toxicity effects of Anastatica hierochuntica aqueous extract on prenatal development of Sprague-Dawley rats. J Ethnopharmacol. 2019, 245, 112180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kausilya, S.R.; Farah, S.T.; Mazidah, M.Z.A.; Mohammad, R.I.S. Effect of pre-treatment and different drying methods on the physicochemical properties of Carica papaya L. leaf powder, J. Saudi Soc. Agric. Sci. 2019, 18, 150–156. [Google Scholar]

- Van Wyk, B.E.; Wink. M. Medicinal Plants of the World: An Illustrated Scientific Guide to Important Medicinal Plants and Their Uses, 1st ed.; Timber Press, Portland, 2004; 480p.

- Hansen, C.J.; Siricilla, S.; Boatwright, N.; Rogers, J.H.; Kumi, M.E.; Herington, J. Effects of Solvents, Emulsions, Cosolvents, and Complexions on Ex Vivo Mouse Myometrial Contractility. Reprod. Sci. 2022, 29, 586–595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Plaskova, A.; Mlcek, J. New insights of the application of water or ethanol-water plant extract rich in active compounds in food. Front Nutr. 2023, 28, 10:1118761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corriveau, S.; Rousseau, E.; Berthiaume, M.; Pasquier, J.C. Lipoxygenase and cyclooxygenase inhibitors reveal a complementary role of arachidonic acid derivatives in pregnant human myometrium. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2010, 203, 266.e1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Romaniewicz, M.; Całka, J.; Jana, B. Effects of Substance P and Neurokinin A on the Contractile Activity of Inflamed Porcine Uterus. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 13184. [Google Scholar]

- Blanks, A.M..; Shmygol, A.; Thornton, S. Regulation of oxytocin receptors and oxytocin receptor signaling. Semin. Reprod. Med. 2007, 25, 52–9. [CrossRef]

- Arrowsmith, S.; Wray, S. Oxytocin: its mechanism of action and receptor signalling in the myometrium. J. Neuroendocrinol. 2014, 26, 356–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Porta, M.; Boening, A.; Tiemann, J.; Zack, A.; Patel, A.; Sondgeroth, K. The Contractile Response to Oxytocin in Non-pregnant Rat Uteri Is Modified After the First Pregnancy. Reprod. Sci. 2023, 30, 2152–2165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Veiga, G.A.; Milazzotto, M.P.; Nichi, M.; Lúcio, C.F.; Silva, L.C.; Angrimani, D.S.; Vannucchi, C.I. Gene expression of estrogen and oxytocin receptors in the uterus of pregnant and parturient bitches. Braz J Med Biol Res. 2015, 48, 339–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Astutik, H.; Santoso, B.; Agil, M. The Effect of Anastatica hierochuntica L. Extract on the Histology of Myometrial Cells and Prostaglandin Levels (PGE2, PGF2α) in Pregnant Mice. Advances in Health Sciences Research. 2019, 22, 81–86. [Google Scholar]

- Adebisi, M.I; Alka, H. Uterotonic effect of aqueous extract of Launaea taraxacifolia Willd on rat isolated uterine horns. Afr. J. Biotechnol. 2019, 18, 399–407. [Google Scholar]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).