1. Introduction

Over the last twenty years intensive research indicated that the revolution in adult brain functionality is largely depended on neural plasticity, a property describing the ability of the brain to adapt to various intrinsic and extrinsic stimuli by reorganizing its structure, function and connections [

1,

2,

3].

Accumulating evidence suggests that neurotrophins (NTs) along with their cognate tyrosine kinase receptors (Trks) hold key roles in neural plasticity, thus determining the development and function of the nervous system [

4,

5]. They belong to a family of neurotrophic factors that are secreted by presynaptic and postsynaptic neurons, microglia and glial cells, astrocytes and oligodendrocytes or other types of cells including muscle cells, and display paracrine and autocrine actions on these cells [

6,

7,

8,

9,

10,

11,

12,

13,

14,

15]. In particular, NTs determine the development of neuronal networks by regulating the growth of neuronal processes, the development of synapses and synaptic plasticity, as well as the neuronal survival, differentiation and myelination. They decisively affect cognitive functions, such as learning and memory, brain development and homeostasis, sensorial training and recovery from brain injury [

1].

NTs exert their effects on the central and sympathetic nervous system via activation of their specific tyrosine kinase (TrkA, TrkB and TrkC) receptors belonging to the family of tropomyosin-related kinase receptors [

16,

17]. The brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF) is the most abundant neurotrophin in the adult brain and one of the major regulators of neurotransmission and neural plasticity [

13,

18,

19]. It is an essential regulator of the cellular signaling underlying cognition, and in particular, synaptic efficacy, which is a determinant parameter in learning and memory [

20]. Deficits in BDNF signaling are associated with the pathogenesis of various neurological and psychiatric disorders, including Alzheimer’s disease (AD) and depression [

20,

21,

22], whereas BDNF administration attenuates amyloid-β peptide-induced memory deficits [

23].

Neurotrophin 3 (NT3) is structurally related to BDNF and is linked to neurogenesis mainly in the hippocampus as it promotes hippocampal cell growth, differentiation and survival. NT3 has also neuroprotective effects on sympathetic and sensory neurons [

24,

25]. Neurotrophin 4 (NT4/5) also plays a significant role in neurogenesis [

26] and affects neuritic morphology and synapse formation [

27]. It is worth noting that BDNF, NT3 and NT4/5 levels are decreased in the hippocampus of AD patients [

28].

Normal aging and neurodegenerative disorders are usually associated with cognitive deficits and researchers focus on finding compounds, which could prevent, delay or restore this cognitive deterioration. Polyphenols, such as resveratrol, isolated from medicinal plants, are intensively studied due to their beneficial effects on memory and neuroprotection [

29]. Other compounds including curcumin [

30,

31], fisetin [

31] and epicatechin [

32], were found to improve synaptic plasticity.

Oleuropein (OLE) and its hydrolysis product, hydroxytyrosol, are the main constituents of the leaves and unprocessed olive drupes of

Olea europaea. Preclinical studies reported that these compounds display pleiotropic health benefits, mainly associated with their cardioprotective [

33,

34,

35,

36,

37,

38,

39,

40], anti-inflammatory [

41], anti-diabetic [

42] and anti-oxidant properties [

43]. Current studies employing murine models of AD indicated that OLE also displays neuroprotective properties [

44,

45]. In particular, OLE ameliorated cognitive impairment and improved synaptic function in TgCRND8 mice, a well-known model of Alzheimer's Disease expressing a double mutant form of human amyloid-β precursor protein, via inhibition of β-amyloid peptide aggregation, which is associated with neural toxicity [

46]. Furthermore, OLE prevented the colchicine-induced cognitive dysfunction in rats [

47]. It is also of note that long-term treatment of old mice with phenol-rich extra-virgin olive oil improved their memory and learning ability [

48]. Olive oil also improved the performance of Senescence Accelerated Mouse-Prone (SAMP8) mice, a naturally occurring model of accelerated aging, in the T-maze test [

49].

Previous study reported that fenofibrate (FEN), a PPARα agonist, markedly activated the hippocampal peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-gamma coactivator-1 alpha (PGC-1α)/irisin/BDNF pathway and induced synaptic plasticity in rats following a high-fat, high-fructose diet [

50]. Therefore, the present study investigated the effect of OLE, a PPARα agonist [

39], on neural plasticity, emphasizing the role of this nuclear transcription factor in the OLE-mediated regulation of the neurotrophins, BDNF, NT3 and NT4/5. For this purpose, 129/Sv wild-type (WT) and

Pparα-null mice were treated with either OLE or FEN, a selective PPARα agonist. The data indicated that OLE up-regulated BDNF and its receptor TrkB in the PFC of mice, while it had no effect in their hippocampus, where though it increased the synthesis of NT4/5. FEN also triggered a strong induction of BDNF, NT3 and TrkB in the PFC of mice and increased the synthesis of NT4/5 in their hippocampus and PFC. The OLE- and FEN-induced effects on these important neural plasticity factors were PPARα-dependent, because they did not occur in the PPARα-deficient mice.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Animals

Adult male 129/Sv WT and

Ppara-null mice [

51,

52] were used in this study. The WT and

Pparα-null mice received

ad libitum the standard rodent chow diet (diet 1324 TPF, Altromin Spezialfutter GmbH & Co. KG). All animals were housed up to five per cage under a standard 12-h light, 12-h dark cycle and had continuous access to drinking water. There was a monitoring on a daily basis of each mouse for outward signs of distress or adverse health effects. All procedures involving animals were reviewed and approved by the ethics committee of the Medical School of the University of Ioannina. They conformed to the International European Ethical Standards (86/609-EEC) for the care and use of laboratory animals.

2.2. Drugs and treatment

OLE (100mg/kg) was administered daily in the food pellets for three consecutive weeks. The dosing regime of OLE was designed using findings from previous dose-response experiments [

40]. At the end of the experiment, mice were killed by CO

2 asphyxiation and trunk blood was collected in BD Microtainer Serum Separator Tubes (Becton, Dickinson and Company, USA) for biochemical analyses. Hippocampus and prefrontal cortex were dissected from the brain for total RNA and total cellular protein extraction. All brain tissues and serum samples were kept at -80

0C until assayed.

2.3. In vivo experiments

Adult male (129/Sv) WT and Ppara-null mice were randomly assigned to 6-7 mice per group. OLE (100 mg/kg) was administered daily in the food pellets for three consecutive weeks in both, WT and Ppara-deficient mice. Controls received the normal rodent diet.

The dose of OLE was based on our previous findings [

40,

53] and on the literature [

54]. OLE was administered in the food pellets, because it has been shown that, even under normal iso-osmotic luminal conditions, OLE is poorly absorbed. Its absorption can be significantly improved by solvent flux through paracellular junctions, made possible by hypotonic conditions in the intestinal lumen [

55]. The presence of glucose or amino acids in the intestinal lumen that follows a meal stimulates water flux

via the opening of paracellular junctions. It is possible that this mechanism has a similar effect on OLE absorption as a hypotonic solution [

56]. Although the pharmacokinetic profile of OLE has not been determined in mice, Boccio and colleagues indicated that a single oral dose of OLE (100 mg/kg) is absorbed in rats, reaching 200 ng/ml in tmax of 2 h [

57]. The experiment was terminated when mice of all groups were killed by CO

2 asphyxiation.

2.4. Quantitative real-time PCR

Total RNA from hippocampus and PFC was isolated using Trizol reagent (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) following the manufacturer’s protocol. The concentration of total RNA in each sample was determined spectrophotometrically. Quantitative real-time PCR (qPCR) was performed with cDNA, which was generated from 1 μg total RNA using a SuperScript II reverse transcriptase kit (Invitrogen). The sequences of the forward and reverse gene-specific primers that were used in this study are shown in

Table 1. The SYBR Green PCR Master Mix (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA) was used for the real-time reactions, which were performed employing a C1000 Touch thermal cycler with a real-time detection system (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Hercules, CA). Relative mRNA expression was normalized to β-actin levels (QuantiTect primer assay; QIAGEN, Valencia, CA), and values were quantified using the comparative threshold cycle method.

2.5. Western blot analysis

Immunoblot analysis of BDNF, TrkB, phospho-ERK, phospho-CREB and phospho-AKT protein levels was performed using total cellular extracts from hippocampus, PFC and differentiated into neurons human SH-SY5Y neuroblastoma cells. The total cellular proteins were extracted using the RIPA buffer supplemented with protease inhibitors, phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride (1mΜ), β-glycerophosphate (5mΜ), NaF (5mM), Na2MoO4 (2 mM) and NaVO3 (1 mM). The BCA Protein Assay Kit (Pierce, IL, USA) was used for the determination of protein concentration in the samples. Proteins were subjected to SDS-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis and immunoblotting using the following antibodies: Rabbit polyclonal BDNF-specific IgG (Santa Cruz Biotechnology), rabbit polyclonal phosphorylated (Ser133) CREB-1-specific IgG (Cell Signaling), rabbit monoclonal TrkB (Cell signaling), rabbit monoclonal phospho-ERK (Cell Signaling), rabbit monoclonal phospho-AKT (Cell Signaling). Secondary antibodies conjugated with horseradish peroxidase (Santa Cruz Biotechnology) were used, and proteins were detected by using an enhanced chemiluminescence detection kit (GE Healthcare, Chalfont St. Giles, Buckinghamshire, UK). Immunoblotting with either a-tubulin- or b-actin-specific antibodies (Santa Cruz Biotechnology) and anti-goat IgG horseradish peroxidase-conjugated secondary antibody was used as a loading control.

2.6. In vitro experiments

2.6.1. Cell culture

The human neuroblastoma cell line, SH-SY5Y, was obtained from the American Type Culture Collection (ATCC, Manassas, VA, USA). SH-SY5Y cells were cultured in a mixture of Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium (DMEM GlutaMAX) and Ham’s F12 NutrientMix (1:1), containing glucose (25 mM) and L- glutamine (2 mM). This medium was supplemented with 10% (v/v) heat-inactivated fetal bovine serum (FBS) and 1% penicillin-streptomycin (P/S). Cells kept at a confluence below 70% (100.000 cells per well) were cultivated in 12 well-plates at 37 °C with 5% CO2 and saturated humidity.

2.6.2. Cell differentiation and viability

Following incubation of 24hrs, the human neuroblastoma SH-SY5Y cells were differentiated into cholinergic neurons using retinoic acid (RA, 5μM), which was added to culture medium that did not contain FBS. Cell incubation lasted 5 days and the culture medium supplemented with fresh RA was changed every three days.

Following 5 days of incubation, differentiated human SH-SY5Y cells were treated for four hours with the culture medium without FBS, containing only either OLE (10μM) or FEN (10μM) or the highly selective PPARα agonist, Wy-14643 (10μM). Subsequently, either H2O2 (final concentration 750 μΜ) or 7PA2-CHO supernatant (final concentration 75% v/v) from a CHO (Chinese hamster ovary) cell line stably expressing a mutant form of the human amyloid precursor protein (APP) (Podlisay et al, 1995), was added in the cell culture in order to induce β-amyloid toxicity. CHO-K1 supernatant at final concentration 75% v/v was used in the control cell cultures. Following incubation of the differentiated cells for additional 48hrs, MTS reagent [20 μl of MTS (1.90 mg/ml)] was added and the plates were incubated at 37°C and 5% CO2 for 120 min. Absorbance was measured using a spectrophotometer at 492 nm and the results were expressed as % cell viability compared to DMSO- or medium-treated cells, which represent 100% of cell viability.

2.7. Statistical analysis

The present data are presented as the mean ± SE. They were analyzed using the one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) program followed by multiple comparisons employing the Bonferonni’s and Tuckey’s list honest significant difference methods. The significance level for all analyses was set at probability of less than 0.05.

3. Results

3.1. Assessment of chronic OLE treatment in neural plasticity indices in PFC

Treatment of WT mice with OLE, a PPARα agonist [

39], for 21 days increased BDNF mRNA and protein expression in their PFC and this effect was PPARα-dependent, because OLE did not increase

BDNF in

Ppara-null mice (

Figure 1A). Similarly, chronic treatment of WT mice with OLE increased TrkB mRNA and protein expression in their PFC, an effect apparently involving PPARα, because no change in

TrkB expression was observed in this brain region of

PPARα-null mice (

Figure 1B). Notably, OLE repressed BDNF mRNA and protein expression in the PFC of

Ppara-deficient mice (Figures 1A), an effect that underscores the distinct role of PPARα in the effects of OLE on BDNF in this brain area. Chronic treatment of WT mice with OLE had no effect on

NT3 and

NT4/5 mRNA expression in their PFC (Figures 1C and 1D, respectively). Interestingly, baseline

NT3 mRNA levels were higher in

Pparα-null than in WT mice and OLE repressed them (

Figure 1C). Constitutive

NT4/5 mRNA expression raged at lower levels in the PFC of

Pparα-null mice than in WT mice, and OLE further repressed it (

Figure 1D).

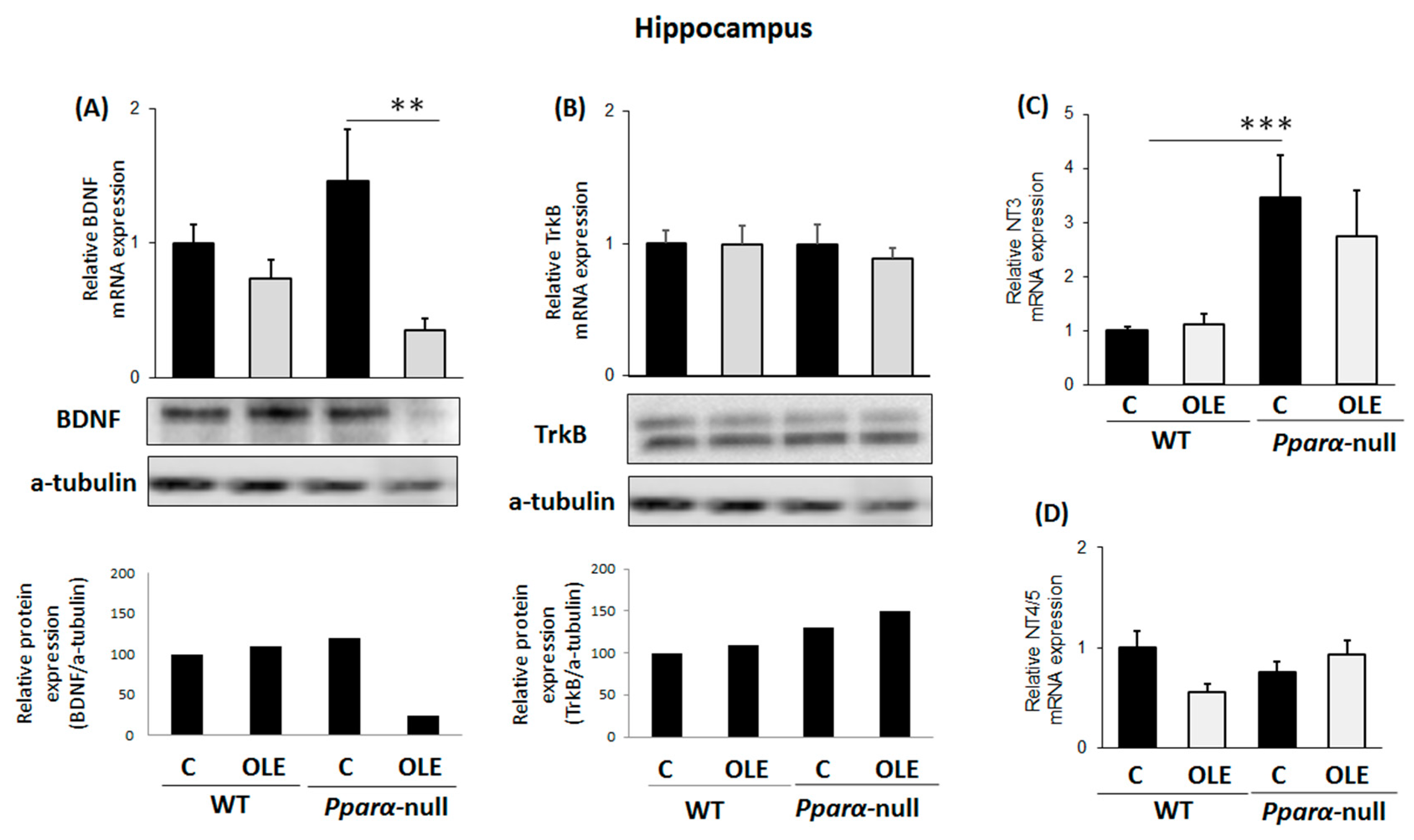

3.2. Assessment of chronic OLE treatment on neural plasticity indices in the hippocampus

Chronic treatment of WT mice with OLE did not affect BDNF and TrkB mRNA and protein expression in their hippocampus (Figures 2A and 2B, respectively). Importantly however, OLE significantly repressed BDNF mRNA and protein expression in the hippocampus of

Ppara-deficient mice (

Figure 2A), an effect that indicates the preventive role of PPARα in the OLE-mediated downregulation of BDNF in the hippocampus. In WT mice following chronic OLE treatment, no alteration was observed in

NT3 mRNA expression in their hippocampus compared to controls (

Figure 2C). Notably, constitutive

ΝΤ3 mRNA expression ranged at higher levels in the hippocampus of

Pparα-null mice than in WT mice (

Figure 2C). OLE did not affect

NT4/5 mRNA expression in the hippocampus of WT and

Pparα-null mice (

Figure 2D).

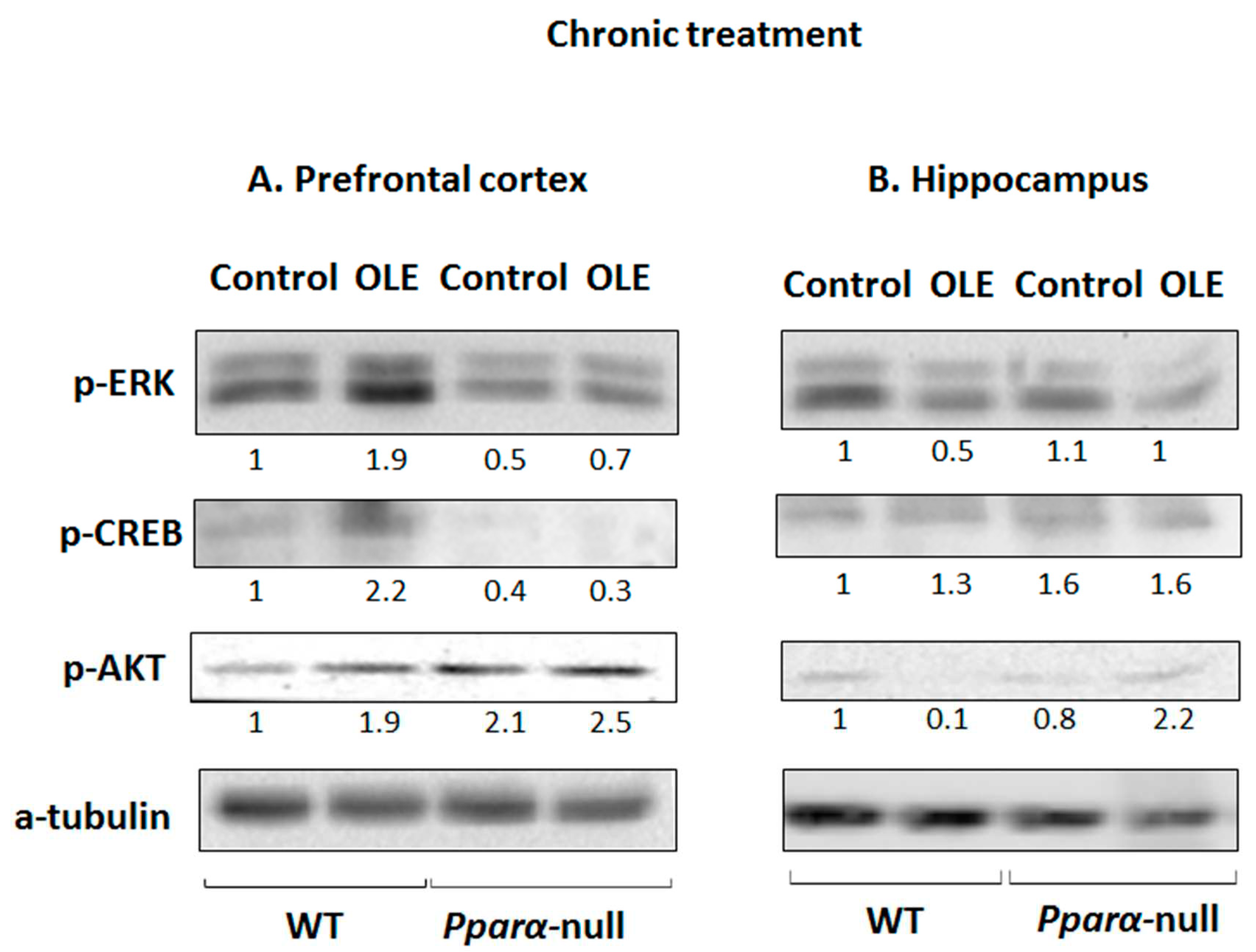

3.3. OLE-induced ERK, AKT and PKA/CREB activation

Chronic treatment of WT mice with OLE increased the phosphorylation of ERK1/2, CREB and AKT in their PFC compared to controls (

Figure 3A). The role of PPARα in ERK1/2, CREB and AKT activation by OLE appears to be determinant, because the drug did not affect the activation of these signaling pathways in

Pparα-null mice (

Figure 3A). Interestingly, pCREB protein levels were markedly lower in the PFC of

Pparα-deficient mice and OLE did not affect them (

Figure 3A). OLE had no similar activating effects on ERK1/2, AKT and PKA/CREB linked signaling pathways in the hippocampus of WT mice (

Figure 3B).

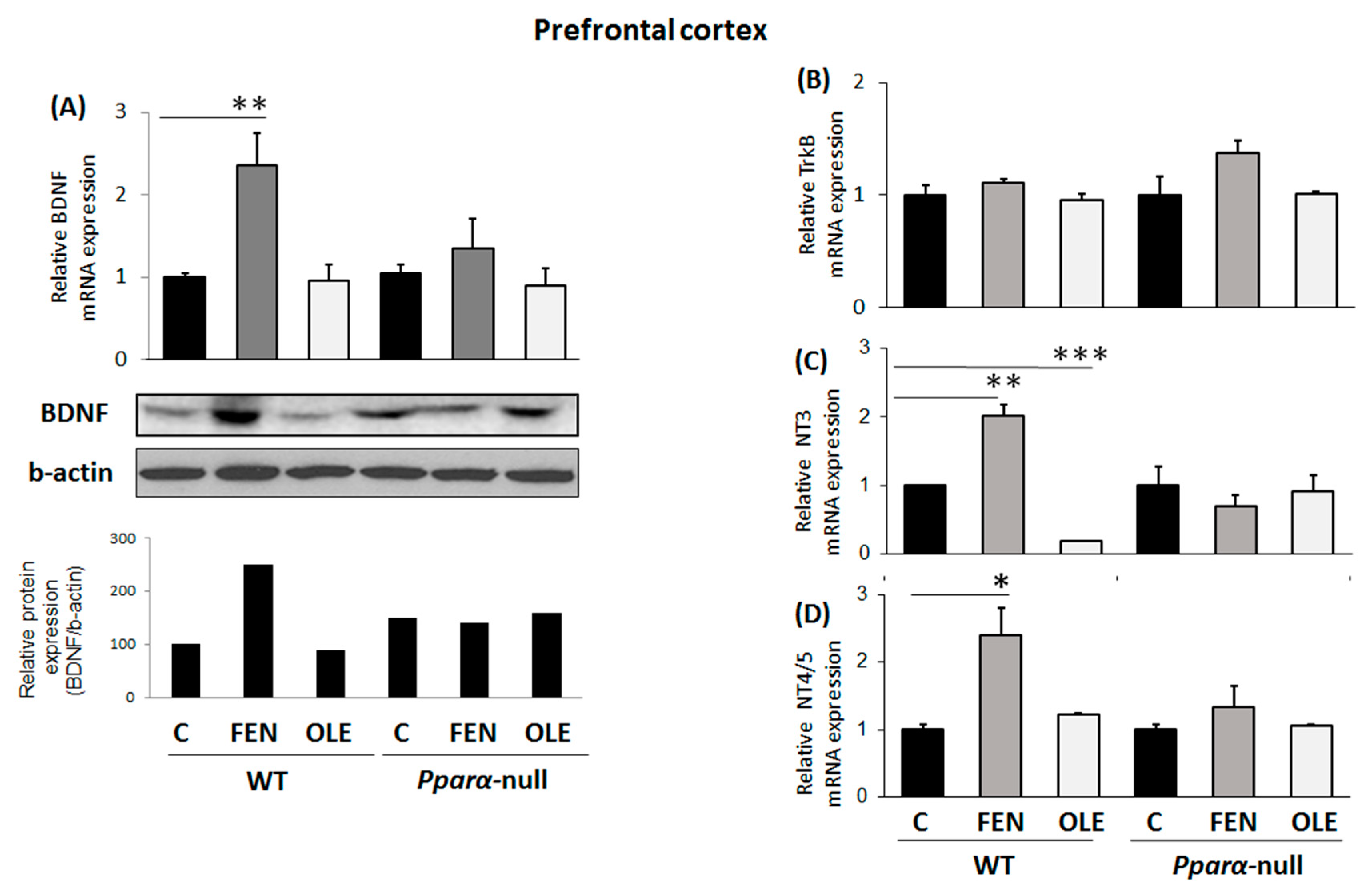

3.4. Assessment of subacute OLE treatment in neural plasticity indices in PFC

Treatment of WT mice with OLE for 4 days had no effect on BDNF mRNA and protein expression in their PFC compared to controls (

Figure 4A), but FEN, a more potent PPARα agonist, upregulated BDNF in this brain area (

Figure 4A). The inducing effect of FEN on BDNF expression in the PFC was PPARα-dependent, because the drug did not affect BDNF expression in the PFC of

Ppara-null mice (

Figure 4A).

As in the case of BDNF, subacute treatment of WT mice with OLE had no effect on

TrkB mRNA expression in their PFC when compared to controls (

Figure 4B). Interestingly though, OLE markedly repressed NT3 mRNA expression in the PFC of WT mice potentially via PPRAα activation, because no similar effect was observed in

Pparα-deficient mice (

Figure 4C). FEN upregulated both, NT3 and NT4/5, in the PFC of WT mice and this effect appears to be PPARα-dependent, because it was not observed in

Pparα-null mice (

Figure 4C and 4D).

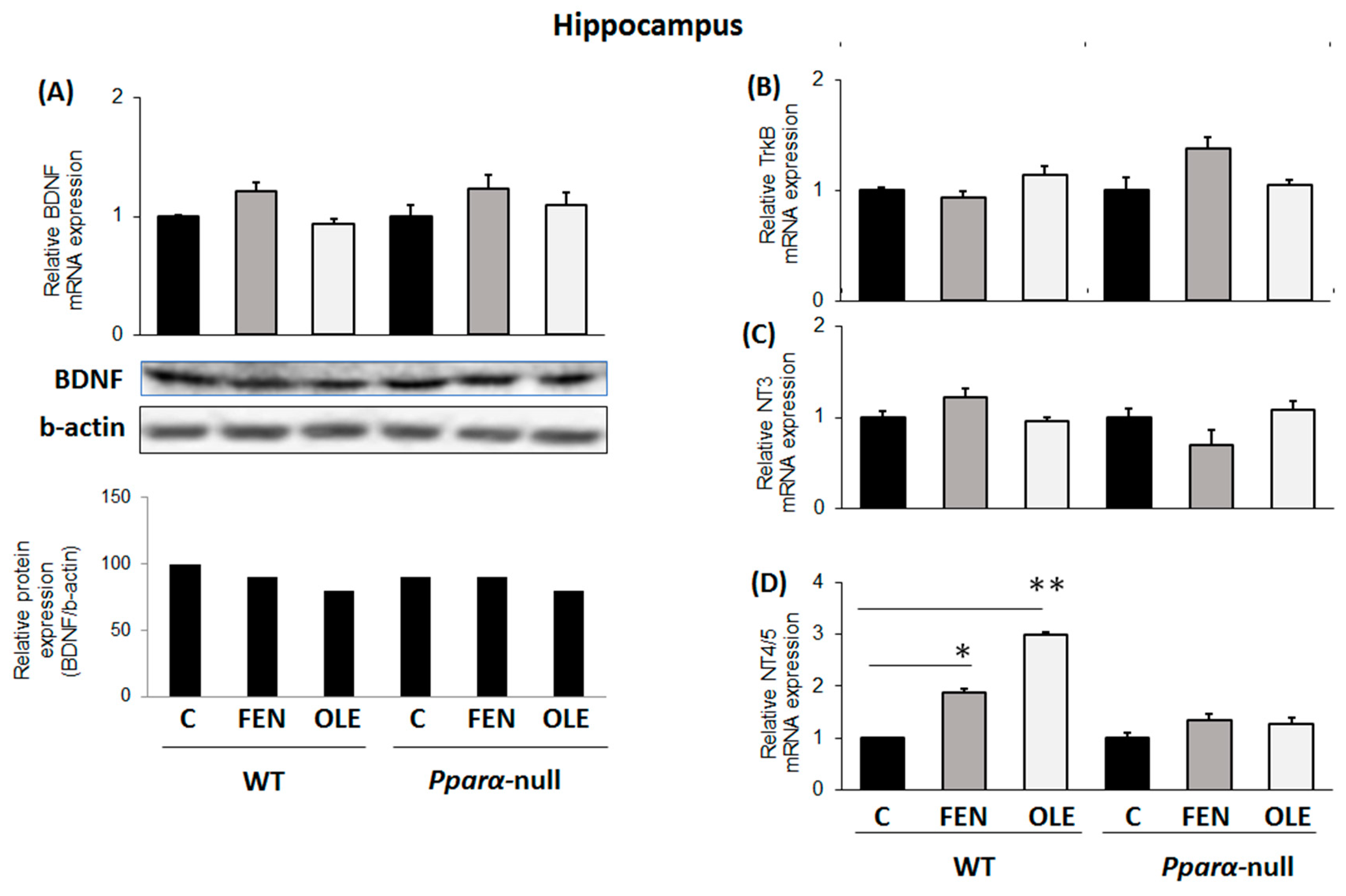

3.5. Assessment of subacute OLE treatment in neural plasticity indices in hippocampus

Treatment of mice with either OLE or FEN for 4 days had no effect on

BDNF,

TrkB and

NT3 expression in their hippocampus compared to controls (Figures 5A, 5B and 5C, respectively). Nonetheless, both drugs upregulated NT4/5 in the hippocampus and this upregulation appears to be PPARα-mediated, because no NT4/5 upregulation was induced by FEN and OLE in

Pparα-null mice (

Figure 5D).

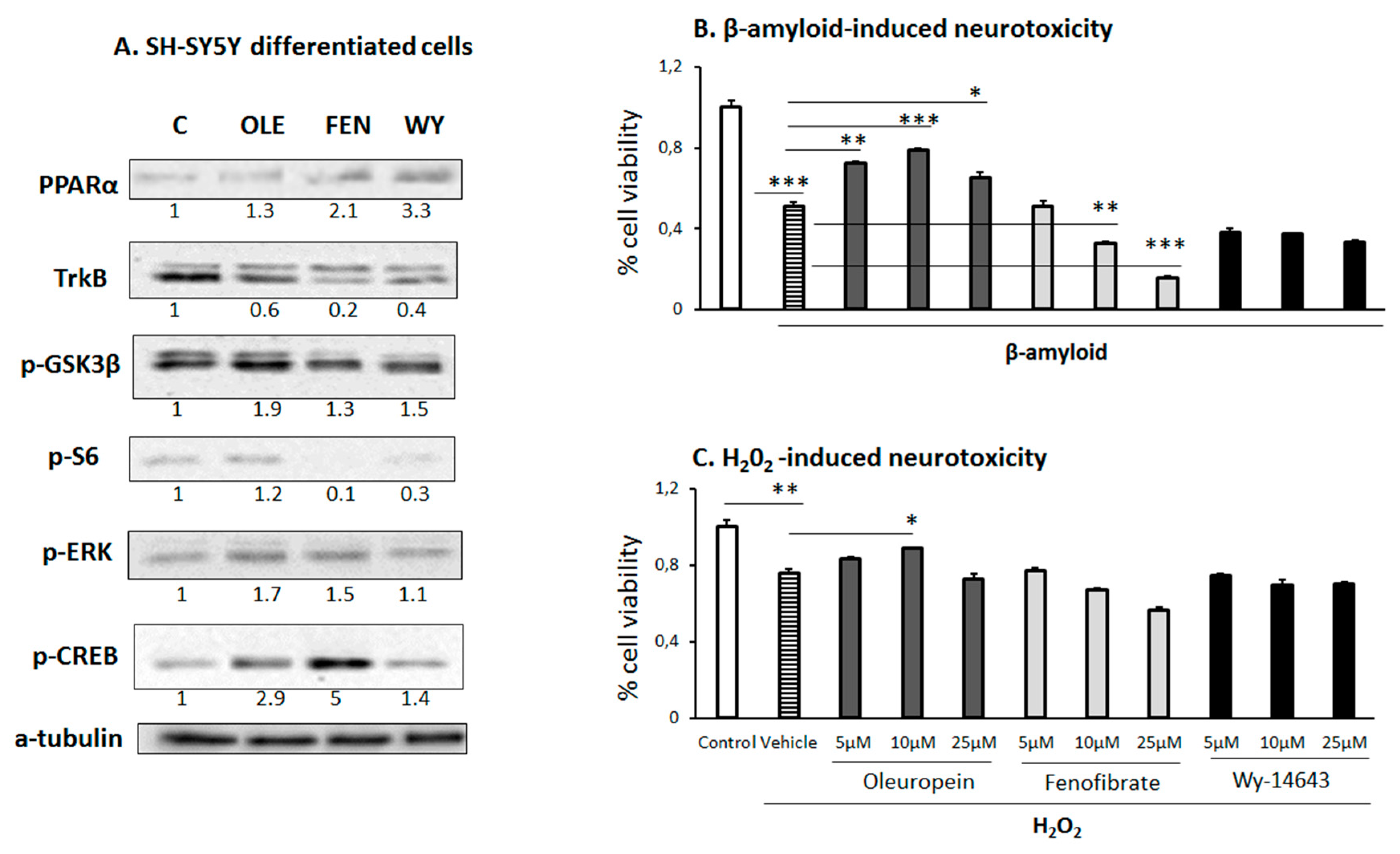

3.6. Effect of OLE on differentiated human SH-SY5Y neuroblastoma cells

In vitro investigation using human SH-SY5Y neuroblastoma cells differentiated into cholinergic neurons indicated that OLE and FEN activated both, ERK1/2 and PKA/CREB signaling pathways (

Figure 6A), whereas Wy-14643 did not affect these signaling pathways (

Figure 6A). Moreover, all three substances induced

PPARα expression in these cells. Interestingly, OLE increased the phosphorylation of GSK3β, whereas FEN and Wy-14643 had a weaker on it (

Figure 6A).

It is of note that preincubation of the differentiated SH-SY5Y cells with OLE (but not with FEN or Wy-14643), protected them most prominently from natural Amyloid β (Aβ) peptides (

Figure 6B) and to some extent from the H

2O

2-induced cell toxicity (

Figure 6C). In particular, OLE at a concentration of 5-10 μM provided 50% neuroprotection against Aβ-induced toxicity. These OLE-induced neuroprotective effects appear to be PPARα-independent, because two other more selective PPARα agonists, the Wy-14643 and FEN, either did not protect or even dose-dependently exaggerated, respectively the toxic effects of Aβ amyloid peptides (

Figure 6B).

4. Discussion

Current study investigated the impact of OLE on neural plasticity in the hippocampus and PFC of mice, emphasizing the role of the nuclear receptor and transcription factor, PPARα. The findings indicated that chronic treatment of WT mice with OLE increased the synthesis of BDNF, as previously reported [

58], and its receptor, TrkB, in their PFC as compared to controls, whereas the drug had no effect on them in the PFC of

Pparα-null mice. This finding underscores the crucial role of PPARα in the OLE-induced upregulation of these important indices of neural plasticity in the PFC, which is potentially triggered by activation of ERK1/2, AKT and PKA/CREB signaling pathways that possess crucial roles in the regulation of neurotrophins [

4], neural plasticity [

59,

60] and survival [

60,

61,

62,

63]. The present findings are in line with those of a previous study reporting that plant polyphenols including resveratrol and OLE, among others, improve synaptic plasticity by activating neuronal signaling pathways, which control the memory and long-term potentiation (LTP) of synapses. The OLE-induced LTP in the hippocampus indicates increased synaptic activity, that is usually followed by a long-lasting increase in signal transmission among neurons and is triggered by activation of signaling pathways including the PKA/CREB [

29,

64,

65].

Unlike long term OLE treatment, subacute administration of WT mice with the drug at the dose given, did not manage to increase BDNF and TrkB synthesis in their PFC. Nonetheless, subacute treatment of WT mice with FEN, a selective PPARα agonist [

66], upregulated BDNF in their PFC, but it did not affect

TrkB expression in this brain tissue. The FEN-induced BDNF upregulation in the PFC is PPARα-dependent, because the drug did not increase this neurotrophic factor in the PFC of

Pparα-null mice. Interestingly, FEN increased also the synthesis of NT3 in the PFC of WT mice and NT4/5 in both, PFC and hippocampus, via PPARα activation as no similar upregulating effects were detected in

Pparα-deficient mice. Both, long-term and subacute treatment with OLE had no upregulating effect on

NT3 expression in the PFC and hippocampus of WT mice. It is of note though that subacute OLE administration had a downregulating effect on

NT3 in the PFC of WT mice, whereas the drug upregulated NT4/5 in their hippocampus via a mechanism potentially involving PPARα activation, because it did not affect

NT4/5 expression in

Pparα-null mice. Unlike previous studies indicating that OLE can improve synaptic plasticity in the dentate gyrus of rat hippocampus, thus attenuating Alzheimer’s disease-like pathology [

67], the present study indicated that either chronic or subacute treatment of WT mice with OLE at the dose given, had no upregulating effect on BDNF and TrkB in their hippocampus, but subacute OLE increased the synthesis of NT4/5 in this brain region. Apparently, the effect of OLE on neuronal plasticity indices is species-, dose-and time-dependent.

It is also of note that OLE protected differentiated human SH-SY5Y neuroblastoma cells from β-amyloid- and H

2O

2-induced toxicity. This neuroprotective effect of OLE against the β-amyloid-induced toxicity was unrelated to PPARα activation, because both selective PPARα agonists, FEN and Wy-14643, did not prevent neurotoxicity in this

in vitro neuronal model. It appears that OLE may exploit both PPARα-dependent and independent pathways to promote neural plasticity and protect against oxidative stress and β-amyloid neurotoxicity. This hypothesis is supported by the findings of a previous study reporting that the neuroprotective effect of PPARα agonists do not necessarily directly depend on PPARα regulated pathways [

68]. Present findings along with those from previous studies reporting that OLE prevents the aggregation of β-amyloids, tau, amylin, α-synuclein and ubiquitin proteins in the brain, reduces neuronal apoptosis and activates several antioxidant pathways [

69], indicate that OLE and similar drugs, such as hydroxytyrosol, provide neuroprotection and could be used to prevent or delay the onset of neurodegenerative disorders, a subject that should be thoroughly investigated in the framework of clinical studies.

5. Conclusions

Present findings indicated that neuroprotection against oxidative stress and β-amyloid toxicity, as well as the induction of neural plasticity in several brain sites belong to the broad spectrum of the beneficial effects of OLE, the main constituent of olive products belonging to the basic constituents of the Mediterranean diet. In this concept, OLE and similar drugs acting predominantly as PPARα agonists, could modulate a diverse repertoire of functions in the central and peripheral nervous systems, as well as in non-neuronal tissues. Therefore, of particular interest for further investigation could be the potential beneficial effects of PPARα agonists on synaptic plasticity/function and dendritic outgrowth, which are critical parameters, among others, in the regulation of cognitive functions.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Maria Konstandi; Data curation, Foteini Malliou, Aristeidis Kofinas and Maria Konstandi; Formal analysis, Maria Konstandi; Funding acquisition, Maria Konstandi; Investigation, Foteini Malliou, Christina Andriopoulou, Aristeidis Kofinas, Allena Katsogridaki and Maria Konstandi; Methodology, Foteini Malliou, Christina Andriopoulou, Aristeidis Kofinas, Allena Katsogridaki, George Leodaritis, Marousa Darsinou and Maria Konstandi; Project administration, Maria Konstandi; Resources, Frank Gonzalez, Leandros Skaltsounis and Maria Konstandi; Supervision, Maria Konstandi; Validation, Christina Andriopoulou, George Leodaritis and Maria Konstandi; Writing – original draft, Maria Konstandi; Writing – review & editing, George Leodaritis, Frank Gonzalez, Theologos Michaelidis and Leandros Skaltsounis.

Funding

This research project has been funded by the European Union (European Regional Development Fund- ERDF) and Greek national funds through the Operational Program “THESSALY- MAINLAND GREECE AND EPIRUS-2007-2013” of the National Strategic Reference Framework (NSRF 2007-2013, Grant 346985/80753). We certify that the funding source had no involvement in the research conduct and/or preparation of the article, in study design, in the collection, analysis and interpretation of data, in the writing of the article, and the decision to submit the article for publication.

Conflicts of Interest

Authors declare no conflict of interest.

Abbreviations

| PPARα |

peroxisome proliferator activated receptor α |

| BDNF |

brain derived neurotrophic factor |

| TrkB |

tyrosine kinase receptor B |

| NT3 |

neurotrophic factor 3 |

| NT4/5 |

neurotrophic factor 4/5 |

| PGC-1α |

peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-gamma coactivator-1 alpha |

| OLE |

oleuropein |

| FEN |

fenofibrate |

| WY |

Wy-14643 |

| PFC |

prefrontal cortex |

| AD |

Alzheimer’s disease |

| WT |

wild type |

References

- Mateos-Aparicio, P. and A. Rodríguez-Moreno, The Impact of Studying Brain Plasticity. Frontiers in Cellular Neuroscience, 2019. 13(66).

- Cramer, S.C. and E.P. Bastings, Mapping clinically relevant plasticity after stroke. Neuropharmacology, 2000. 39(5): p. 842-51.

- Chen, R., L.G. Cohen, and M. Hallett, Nervous system reorganization following injury. Neuroscience, 2002. 111(4): p. 761-773.

- Reichardt, L.F., Neurotrophin-regulated signalling pathways. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci, 2006. 361(1473): p. 1545-64.

- Huang, E.J. and L.F. Reichardt, Neurotrophins: Roles in Neuronal Development and Function. Annual Review of Neuroscience, 2001. 24(1): p. 677-736.

- Bessis, A., et al., Microglial control of neuronal death and synaptic properties. Glia, 2007. 55(3): p. 233-238.

- Cao, L. , et al., Olfactory ensheathing cells promote migration of Schwann cells by secreted nerve growth factor. Glia, 2007. 55(9): p. 897-904.

- Fukuoka, T. , et al., Brain-Derived Neurotrophic Factor Increases in the Uninjured Dorsal Root Ganglion Neurons in Selective Spinal Nerve Ligation Model. The Journal of Neuroscience, 2001. 21(13): p. 4891-4900.

- Bagayogo, I.P. and C.F. Dreyfus, Regulated release of BDNF by cortical oligodendrocytes is mediated through metabotropic glutamate receptors and the PLC pathway. ASN Neuro, 2009. 1(1).

- Lessmann, V., K. Gottmann, and M. Malcangio, Neurotrophin secretion: current facts and future prospects. Progress in Neurobiology, 2003. 69(5): p. 341-374.

- Matsuoka, I., M. Meyer, and H. Thoenen, Cell-type-specific regulation of nerve growth factor (NGF) synthesis in non-neuronal cells: comparison of Schwann cells with other cell types. The Journal of Neuroscience, 1991. 11(10): p. 3165.

- Ohta, K. , et al., The effect of dopamine agonists: The expression of GDNF, NGF, and BDNF in cultured mouse astrocytes. Journal of the Neurological Sciences, 2010. 291(1): p. 12-16.

- Schinder, A.F. and M. Poo, The neurotrophin hypothesis for synaptic plasticity. Trends Neurosci, 2000. 23(12): p. 639-45.

- Verderio, C. , et al., Cross talk between vestibular neurons and Schwann cells mediates BDNF release and neuronal regeneration. Brain Cell Biology, 2006. 35(2): p. 187-201.

- Tae, Y.Y. , et al., Minocycline Alleviates Death of Oligodendrocytes by Inhibiting Pro-Nerve Growth Factor Production in Microglia after Spinal Cord Injury. The Journal of Neuroscience, 2007. 27(29): p. 7751.

- Becker, E. , et al., Development of survival responsiveness to brain-derived neurotrophic factor, neurotrophin 3 and neurotrophin 4/5, but not to nerve growth factor, in cultured motoneurons from chick embryo spinal cord. J Neurosci, 1998. 18(19): p. 7903-11.

- Lu, B., P. T. Pang, and N.H. Woo, The yin and yang of neurotrophin action. Nature Reviews Neuroscience, 2005. 6(8): p. 603-614.

- Bramham, C.R. and E. Messaoudi, BDNF function in adult synaptic plasticity: the synaptic consolidation hypothesis. Prog Neurobiol, 2005. 76(2): p. 99-125.

- Michael, E.G. , et al., New Insights in the Biology of BDNF Synthesis and Release: Implications in CNS Function. The Journal of Neuroscience, 2009. 29(41): p. 12764.

- Lu, B., G. Nagappan, and Y. Lu, BDNF and synaptic plasticity, cognitive function, and dysfunction. Handb Exp Pharmacol, 2014. 220: p. 223-50.

- Heldt, S.A. , et al., Hippocampus-specific deletion of BDNF in adult mice impairs spatial memory and extinction of aversive memories. Molecular Psychiatry, 2007. 12(7): p. 656-670.

- Prior, M. , et al., The neurotrophic compound J147 reverses cognitive impairment in aged Alzheimer's disease mice. Alzheimers Res Ther, 2013. 5(3): p. 25.

- Zhang, L. , et al., Brain-Derived Neurotrophic Factor Ameliorates Learning Deficits in a Rat Model of Alzheimer's Disease Induced by Aβ1-42. PLOS ONE, 2015. 10(4): p. e0122415.

- Middlemas, D. , Neurotrophin 3, in xPharm: The Comprehensive Pharmacology Reference, S.J. Enna and D.B. Bylund, Editors. 2007, Elsevier: New York. p. 1-3.

- Warner, S.C. and A.M. Valdes The Genetics of Osteoarthritis: A Review. Journal of Functional Morphology and Kinesiology, 2016. 1. [CrossRef]

- Kang, H. and E.M. Schuman, Long-lasting neurotrophin-induced enhancement of synaptic transmission in the adult hippocampus. Science, 1995. 267(5204): p. 1658-62.

- Vicario-Abejón, C. , et al., Role of neurotrophins in central synapse formation and stabilization. Nat Rev Neurosci, 2002. 3(12): p. 965-74.

- Hock, C. , et al., Region-specific neurotrophin imbalances in Alzheimer disease: decreased levels of brain-derived neurotrophic factor and increased levels of nerve growth factor in hippocampus and cortical areas. Arch Neurol, 2000. 57(6): p. 846-51.

- Wang, M. , et al., Oleuropein promotes hippocampal LTP via intracellular calcium mobilization and Ca(2+)-permeable AMPA receptor surface recruitment. Neuropharmacology, 2020. 176: p. 108196.

- Cheng, K.K. , et al., Highly Stabilized Curcumin Nanoparticles Tested in an In Vitro Blood–Brain Barrier Model and in Alzheimer’s Disease Tg2576 Mice. The AAPS Journal, 2013. 15(2): p. 324-336.

- Maher, P. , et al., A pyrazole derivative of curcumin enhances memory. Neurobiology of Aging, 2010. 31(4): p. 706-709.

- Praag, H.v. , et al., Plant-Derived Flavanol (−)Epicatechin Enhances Angiogenesis and Retention of Spatial Memory in Mice. The Journal of Neuroscience, 2007. 27(22): p. 5869-5878.

- Tuck, K.L. and P.J. Hayball, Major phenolic compounds in olive oil: metabolism and health effects. The Journal of Nutritional Biochemistry, 2002. 13(11): p. 636-644.

- Visioli, F., A. Poli, and C. Gall, Antioxidant and other biological activities of phenols from olives and olive oil. Medicinal Research Reviews, 2002. 22(1): p. 65-75.

- Visioli, F. and C. Galli, Oleuropein protects low density lipoprotein from oxidation. Life Sciences, 1994. 55(24): p. 1965-1971.

- Briante, R. , et al., Antioxidant activity of the main bioactive derivatives from oleuropein hydrolysis by hyperthermophilic beta-glycosidase. J Agric Food Chem, 2001. 49(7): p. 3198-203.

- Oi-Kano, Y. , et al., Oleuropein, a phenolic compound in extra virgin olive oil, increases uncoupling protein 1 content in brown adipose tissue and enhances noradrenaline and adrenaline secretions in rats. J Nutr Sci Vitaminol (Tokyo), 2008. 54(5): p. 363-70.

- Visioli, F. , et al., Biological activities and metabolic fate of olive oil phenols. European Journal of Lipid Science and Technology, 2002. 104(9-10): p. 677-684.

- Malliou, F. , et al., The olive constituent oleuropein, as a PPARα agonist, markedly reduces serum triglycerides. The Journal of Nutritional Biochemistry, 2018. 59: p. 17-28.

- Andreadou, I. , et al., The olive constituent oleuropein exhibits anti-ischemic, antioxidative, and hypolipidemic effects in anesthetized rabbits. J Nutr, 2006. 136(8): p. 2213-9.

- Qabaha, K. , et al., Oleuropein Is Responsible for the Major Anti-Inflammatory Effects of Olive Leaf Extract. Journal of Medicinal Food, 2017. 21(3): p. 302-305.

- Jemai, H., A. El Feki, and S. Sayadi, Antidiabetic and Antioxidant Effects of Hydroxytyrosol and Oleuropein from Olive Leaves in Alloxan-Diabetic Rats. Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry, 2009. 57(19): p. 8798-8804.

- Alirezaei, M. , et al., Antioxidant effects of oleuropein versus oxidative stress induced by ethanol in the rat intestine. Comparative Clinical Pathology, 2014. 23(5): p. 1359-1365.

- Luccarini, I. , et al., Oleuropein aglycone protects against pyroglutamylated-3 amyloid-ß toxicity: biochemical, epigenetic and functional correlates. Neurobiology of Aging, 2015. 36(2): p. 648-663.

- Nardiello, P. , et al., Diet Supplementation with Hydroxytyrosol Ameliorates Brain Pathology and Restores Cognitive Functions in a Mouse Model of Amyloid-β Deposition. Journal of Alzheimer's Disease, 2018. 63: p. 1161-1172.

- Grossi, C. , et al., The Polyphenol Oleuropein Aglycone Protects TgCRND8 Mice against Aß Plaque Pathology. PLoS ONE, 2013. 8(8): p. e71702.

- Pourkhodadad, S. , et al., Neuroprotective effects of oleuropein against cognitive dysfunction induced by colchicine in hippocampal CA1 area in rats. The Journal of Physiological Sciences, 2016. 66(5): p. 397-405.

- Pitozzi, V. , et al., Long-Term Dietary Extra-Virgin Olive Oil Rich in Polyphenols Reverses Age-Related Dysfunctions in Motor Coordination and Contextual Memory in Mice: Role of Oxidative Stress. Rejuvenation Research, 2012. 15(6): p. 601-612.

- Farr, S.A. , et al., Extra Virgin Olive Oil Improves Learning and Memory in SAMP8 Mice. Journal of Alzheimer's Disease, 2012. 28: p. 81-92.

- Rizk, F.H. , et al., Fenofibrate Improves Cognitive Impairment Induced by High-Fat High-Fructose Diet: A Possible Role of Irisin and Heat Shock Proteins. ACS Chem Neurosci, 2022. 13(12): p. 1782-1789.

- Akiyama, T.E. , et al., Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-alpha regulates lipid homeostasis, but is not associated with obesity: studies with congenic mouse lines. J Biol Chem, 2001. 276(42): p. 39088-93.

- Lee, S.S. , et al., Targeted disruption of the alpha isoform of the peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gene in mice results in abolishment of the pleiotropic effects of peroxisome proliferators. Mol Cell Biol, 1995. 15(6): p. 3012-22.

- Andreadou, I. , et al., Oleuropein prevents doxorubicin-induced cardiomyopathy interfering with signaling molecules and cardiomyocyte metabolism. J Mol Cell Cardiol, 2014. 69: p. 4-16.

- Impellizzeri, D. , et al., The effects of a polyphenol present in olive oil, oleuropein aglycone, in an experimental model of spinal cord injury in mice. Biochem Pharmacol, 2012. 83(10): p. 1413-26.

- Edgecombe, S.C., G. L. Stretch, and P.J. Hayball, Oleuropein, an antioxidant polyphenol from olive oil, is poorly absorbed from isolated perfused rat intestine. J Nutr, 2000. 130(12): p. 2996-3002.

- Pappenheimer, J.R. and K.Z. Reiss, Contribution of solvent drag through intercellular junctions to absorption of nutrients by the small intestine of the rat. J Membr Biol, 1987. 100(2): p. 123-36.

- Del Boccio, P. , et al., Liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry analysis of oleuropein and its metabolite hydroxytyrosol in rat plasma and urine after oral administration. J Chromatogr B Analyt Technol Biomed Life Sci, 2003. 785(1): p. 47-56.

- Xu, A.N. and F. Nie, Brain-derived neurotrophic factor enhances the therapeutic effect of oleuropein in the lipopolysaccharide-induced models of depression. Folia Neuropathol, 2021. 59(3): p. 249-262.

- Impey, S. , et al., Cross talk between ERK and PKA is required for Ca2+ stimulation of CREB-dependent transcription and ERK nuclear translocation. Neuron, 1998. 21(4): p. 869-83.

- Cañón, E. , et al., Rapid effects of retinoic acid on CREB and ERK phosphorylation in neuronal cells. Mol Biol Cell, 2004. 15(12): p. 5583-92.

- Bonni, A. , et al., Cell survival promoted by the Ras-MAPK signaling pathway by transcription-dependent and -independent mechanisms. Science, 1999. 286(5443): p. 1358-62.

- Nakagawa, S. , et al., Localization of phosphorylated cAMP response element-binding protein in immature neurons of adult hippocampus. J Neurosci, 2002. 22(22): p. 9868-76.

- Shaywitz, A.J. and M.E. Greenberg, CREB: a stimulus-induced transcription factor activated by a diverse array of extracellular signals. Annu Rev Biochem, 1999. 68: p. 821-61.

- Cooke, S.F. and T.V. Bliss, Plasticity in the human central nervous system. Brain, 2006. 129(Pt 7): p. 1659-73.

- Dinda, B. , et al., Therapeutic potentials of plant iridoids in Alzheimer's and Parkinson's diseases: A review. Eur J Med Chem, 2019. 169: p. 185-199.

- Balint, L.B. and L. Nagy, Selective Modulators of PPAR Activity as New Therapeutic Tools in Metabolic Diseases. Endocrine, Metabolic & Immune Disorders - Drug Targets, 2006. 6(1): p. 33-43.

- Fei-fei, P. , et al., Oleuropein Improves Long Term Potentiation at Perforant Path-dentate Gyrus Synapses in vivo. Chinese Herbal Medicines (CHM). 7(3): p. 255-260.

- Gelé, P. , et al., Recovery of brain biomarkers following peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor agonist neuroprotective treatment before ischemic stroke. Proteome Sci, 2014. 12: p. 24.

- Butt, M.S. , et al., Neuroprotective effects of oleuropein: Recent developments and contemporary research. Journal of Food Biochemistry, 2021. 45(12): p. e13967.

Figure 1.

The effect of chronic treatment with oleuropein (OLE) on neural plasticity indices in the prefrontal cortex (PFC) of mice. (A) Following treatment with OLE, brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF) mRNA levels were analyzed in 129/Sv wild-type (WT) and Pparα-null mice by qPCR and protein levels using western blot. TrkB receptor mRNA and protein levels were also analyzed using qPCR and western blot analysis, respectively. Neurotrophin NT3 and NT4/5 mRNA levels were also analyzed with qPCR. Values were normalized to β-actin and are expressed as mean ± SE (n=8-10). Comparisons were between controls (C) and OLE-treated mice. Treatment group differences were calculated using one-way ANOVA, followed by Bonferroni’s test. *P<0.05, **P<0.01, ***P<0.001.

Figure 1.

The effect of chronic treatment with oleuropein (OLE) on neural plasticity indices in the prefrontal cortex (PFC) of mice. (A) Following treatment with OLE, brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF) mRNA levels were analyzed in 129/Sv wild-type (WT) and Pparα-null mice by qPCR and protein levels using western blot. TrkB receptor mRNA and protein levels were also analyzed using qPCR and western blot analysis, respectively. Neurotrophin NT3 and NT4/5 mRNA levels were also analyzed with qPCR. Values were normalized to β-actin and are expressed as mean ± SE (n=8-10). Comparisons were between controls (C) and OLE-treated mice. Treatment group differences were calculated using one-way ANOVA, followed by Bonferroni’s test. *P<0.05, **P<0.01, ***P<0.001.

Figure 2.

The effect of chronic treatment with oleuropein (OLE) on neural plasticity indices in the hippocampus of mice. (A) Following treatment with OLE, brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF) mRNA levels were analyzed in 129/Sv wild-type and Pparα-null mice by qPCR and protein levels using western blot. TrkB receptor mRNA and protein levels were also analyzed using qPCR and western blot analysis, respectively. Neurotrophin NT3 and NT4/5 mRNA levels were also analyzed with qPCR. Values were normalized to β-actin and are expressed as mean ± SE (n=8-10). Comparisons were between controls (C) and OLE-treated mice. Treatment group differences were calculated using one-way ANOVA, followed by Bonferroni’s test. **P<0.01, ***P<0.001.

Figure 2.

The effect of chronic treatment with oleuropein (OLE) on neural plasticity indices in the hippocampus of mice. (A) Following treatment with OLE, brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF) mRNA levels were analyzed in 129/Sv wild-type and Pparα-null mice by qPCR and protein levels using western blot. TrkB receptor mRNA and protein levels were also analyzed using qPCR and western blot analysis, respectively. Neurotrophin NT3 and NT4/5 mRNA levels were also analyzed with qPCR. Values were normalized to β-actin and are expressed as mean ± SE (n=8-10). Comparisons were between controls (C) and OLE-treated mice. Treatment group differences were calculated using one-way ANOVA, followed by Bonferroni’s test. **P<0.01, ***P<0.001.

Figure 3.

The role of chronic treatment with oleuropein (OLE) in the activation of ERK1/2, PKA/CREB and PI3K/AKT signaling pathways. Phosphorylated ERK1/2, CREB and AKT expression levels were examined in proteins extracted from the prefrontal cortex and hippocampus of mice using Western blot analysis. WT: wild-type mice. The numbers underneath the lanes represent the relative protein expression that is defined as the ratio between the OLE-treated and control expression, which is set at 1.

Figure 3.

The role of chronic treatment with oleuropein (OLE) in the activation of ERK1/2, PKA/CREB and PI3K/AKT signaling pathways. Phosphorylated ERK1/2, CREB and AKT expression levels were examined in proteins extracted from the prefrontal cortex and hippocampus of mice using Western blot analysis. WT: wild-type mice. The numbers underneath the lanes represent the relative protein expression that is defined as the ratio between the OLE-treated and control expression, which is set at 1.

Figure 4.

The effect of subacute treatment with oleuropein (OLE) on neural plasticity indices in the prefrontal cortex (PFC) of mice. (A) Following treatment with either OLE or fenofibrate (FEN), brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF) mRNA levels were analyzed in 129/Sv wild-type (WT) and Pparα-null mice by qPCR and protein levels using western blot. TrkB receptor mRNA and protein levels were also analyzed using qPCR and western blot analysis, respectively. Neurotrophin NT3 and NT4/5 mRNA levels were also analyzed with qPCR. Values were normalized to β-actin and are expressed as mean ± SE (n=8-10). Comparisons were between controls (C) and OLE-treated mice. Treatment group differences were calculated using one-way ANOVA, followed by Bonferroni’s test. *P<0.05, **P<0.01, ***P<0.001.

Figure 4.

The effect of subacute treatment with oleuropein (OLE) on neural plasticity indices in the prefrontal cortex (PFC) of mice. (A) Following treatment with either OLE or fenofibrate (FEN), brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF) mRNA levels were analyzed in 129/Sv wild-type (WT) and Pparα-null mice by qPCR and protein levels using western blot. TrkB receptor mRNA and protein levels were also analyzed using qPCR and western blot analysis, respectively. Neurotrophin NT3 and NT4/5 mRNA levels were also analyzed with qPCR. Values were normalized to β-actin and are expressed as mean ± SE (n=8-10). Comparisons were between controls (C) and OLE-treated mice. Treatment group differences were calculated using one-way ANOVA, followed by Bonferroni’s test. *P<0.05, **P<0.01, ***P<0.001.

Figure 5.

The effect of subacute treatment with oleuropein (OLE) on neural plasticity indices in the hippocampus of mice. (A) Following treatment with either OLE or fenofibrate (FEN), brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF) mRNA levels were analyzed in 129/Sv wild-type (WT) and Pparα-null mice by qPCR and protein levels using western blot. TrkB receptor mRNA and protein levels were also analyzed using qPCR and western blot analysis, respectively. Neurotrophin NT3 and NT4/5 mRNA levels were also analyzed with qPCR. Values were normalized to β-actin and are expressed as mean ± SE (n=8-10). Comparisons were between controls (C) and OLE-treated mice. Treatment group differences were calculated using one-way ANOVA, followed by Bonferroni’s test. *P<0.05, **P<0.01.

Figure 5.

The effect of subacute treatment with oleuropein (OLE) on neural plasticity indices in the hippocampus of mice. (A) Following treatment with either OLE or fenofibrate (FEN), brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF) mRNA levels were analyzed in 129/Sv wild-type (WT) and Pparα-null mice by qPCR and protein levels using western blot. TrkB receptor mRNA and protein levels were also analyzed using qPCR and western blot analysis, respectively. Neurotrophin NT3 and NT4/5 mRNA levels were also analyzed with qPCR. Values were normalized to β-actin and are expressed as mean ± SE (n=8-10). Comparisons were between controls (C) and OLE-treated mice. Treatment group differences were calculated using one-way ANOVA, followed by Bonferroni’s test. *P<0.05, **P<0.01.

Figure 6.

The effect of oleuropein (OLE), fenofibrate (FEN) and Wy-14643 (WY), PPARα agonists, on (A) PPARα and TrkB protein expression and on the phosphorylated expression levels of GSK3β, S6, ERK1/2 and PKA/CREB in differentiated human SH-SY5Y neuroblastoma cells into cholinergic neurons, (B) β-amyloid neurotoxicity and (C) H2O2-induced neurotoxicity. Phosphorylated GSK3β, S6, ERK1/2 and CREB expression levels were analyzed in proteins extracted from differentiated human SH-SY5Y cells using Western blot analysis. The numbers underneath the lanes represent the relative protein expression that is defined as the ratio between the drug-treated and control expression, which is set at 1. Beta-amyloid- and H2O2-induced neurotoxicity was assessed using a spectrophotometric analysis of the samples at 492 nm to determine the percentage of cell viability. C: Control (DMSO treated cells).

Figure 6.

The effect of oleuropein (OLE), fenofibrate (FEN) and Wy-14643 (WY), PPARα agonists, on (A) PPARα and TrkB protein expression and on the phosphorylated expression levels of GSK3β, S6, ERK1/2 and PKA/CREB in differentiated human SH-SY5Y neuroblastoma cells into cholinergic neurons, (B) β-amyloid neurotoxicity and (C) H2O2-induced neurotoxicity. Phosphorylated GSK3β, S6, ERK1/2 and CREB expression levels were analyzed in proteins extracted from differentiated human SH-SY5Y cells using Western blot analysis. The numbers underneath the lanes represent the relative protein expression that is defined as the ratio between the drug-treated and control expression, which is set at 1. Beta-amyloid- and H2O2-induced neurotoxicity was assessed using a spectrophotometric analysis of the samples at 492 nm to determine the percentage of cell viability. C: Control (DMSO treated cells).

Table 1.

Oligonucleotide sequences for quantitation of gene mRNA concentration using quantitative PCR assays.

Table 1.

Oligonucleotide sequences for quantitation of gene mRNA concentration using quantitative PCR assays.

| Gene |

Sequences of primers |

| BDNF |

F |

5'-TGAGTCTCCAGGACAGCAAA-3' |

| R |

5'-GACGTTTACTTCTTTCATGGGC-3' |

| TrkB |

F |

5'-TGATGTTGCTCCTGCTCAAG-3' |

| R |

5'-CCCAGCCTTTGTCTTTCCTT-3' |

| NT3 |

F |

5'-CGGATGCCATGGTTACTTCT-3' |

| R |

5'-AGTCTTCCGGCAAACTCCTT-3' |

| NT4/5 |

F |

5'-AGCCGGGGAGCAGAGAAG-3' |

| R |

5'-CACCTCCTCACTCTGGGACT-3' |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).