Submitted:

12 July 2023

Posted:

13 July 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

1. Materials and Methods

1.1. Cell lines and Culture

1.1. Expression of dmrFABP5 in Escherichia coli cells

1.1. DmrFABP5 protein purification

1.1. Drug preparations and treatment plans

1.1. Cell Viability and Combination Index assays (CI)

1.1. Invasion Assays

1.1. Wound Healing Assay

1.1. Soft agar colony formation assay

1.1. Western Blot

1.1. Statistical analysis

1. Results

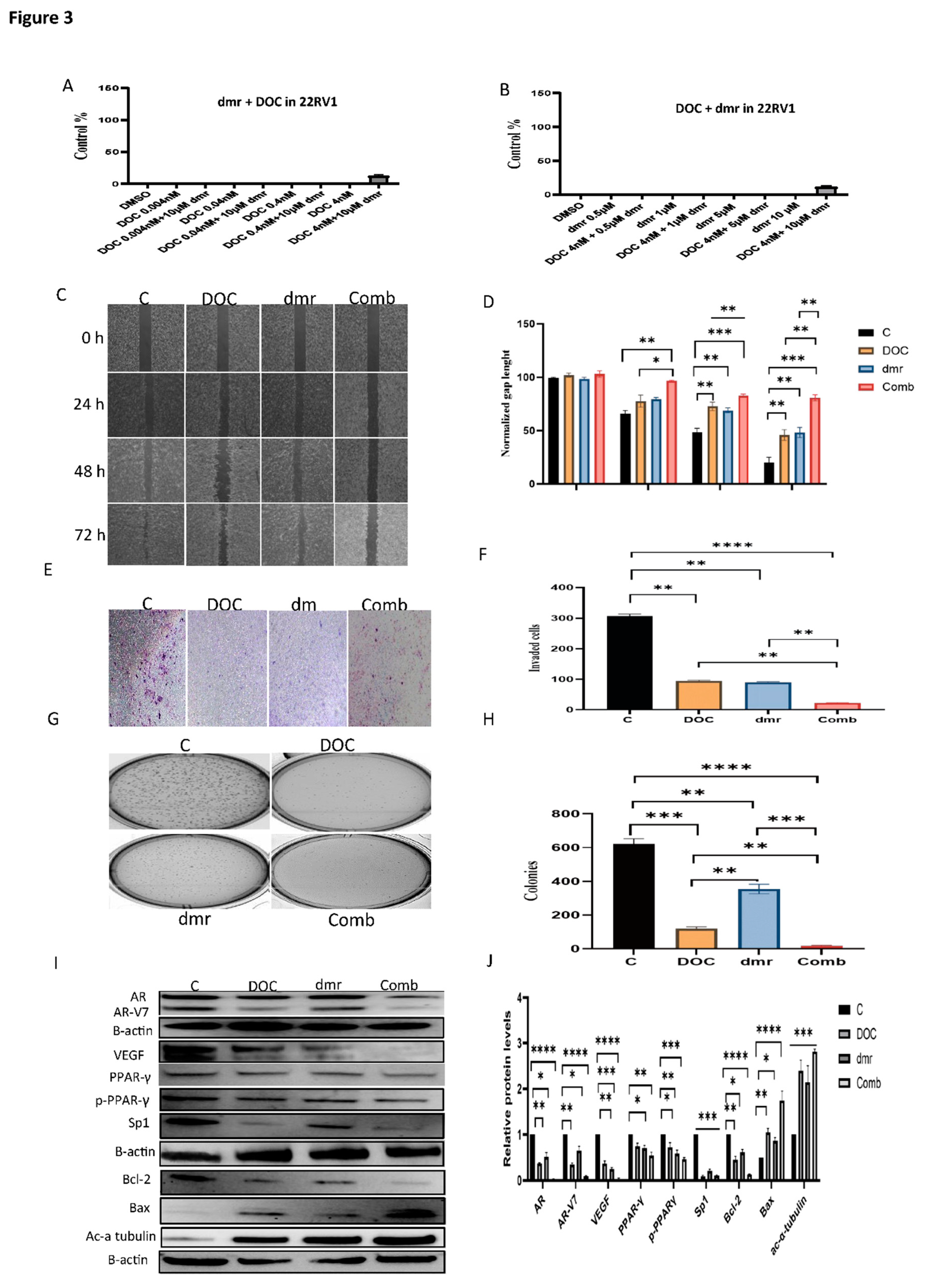

1.1. Compound concentrations used to achieve 50% growth inhibition of PCa cells (IC50)

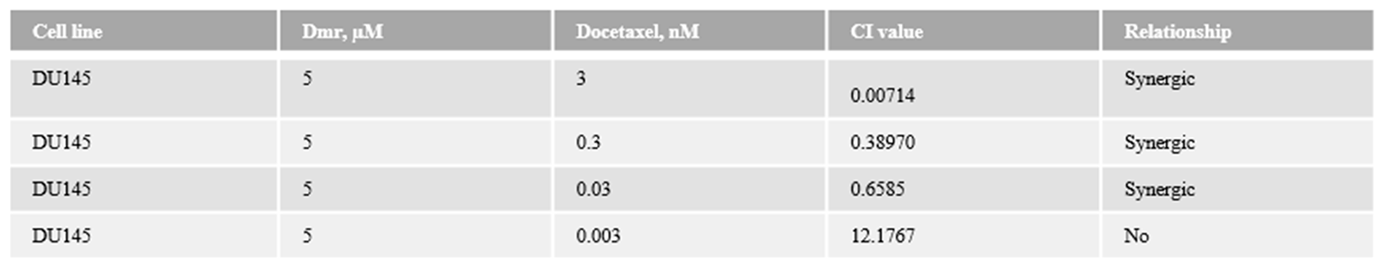

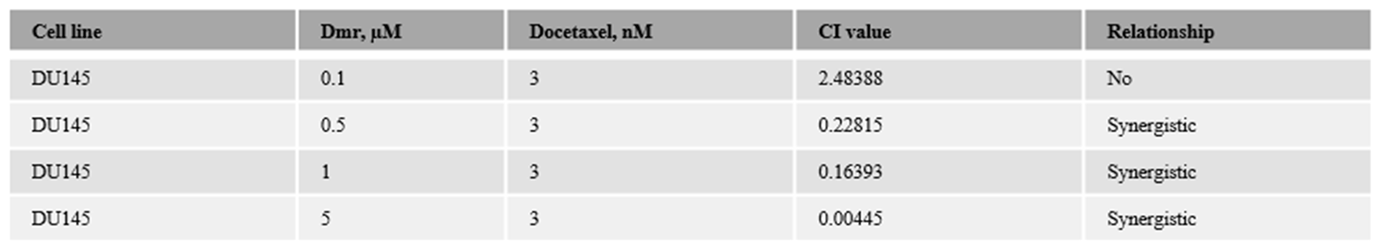

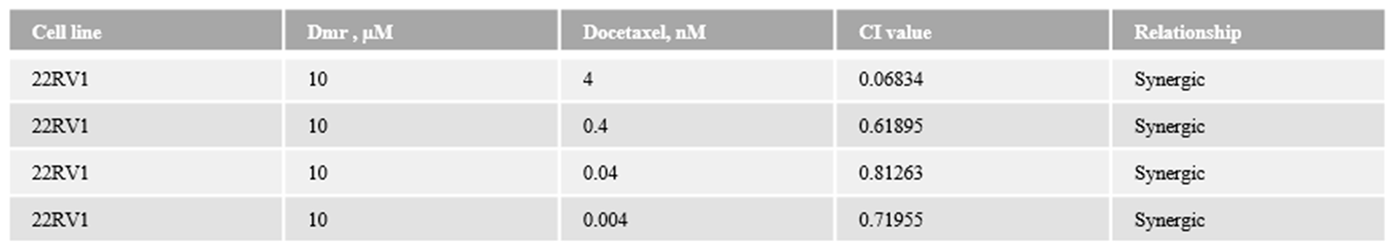

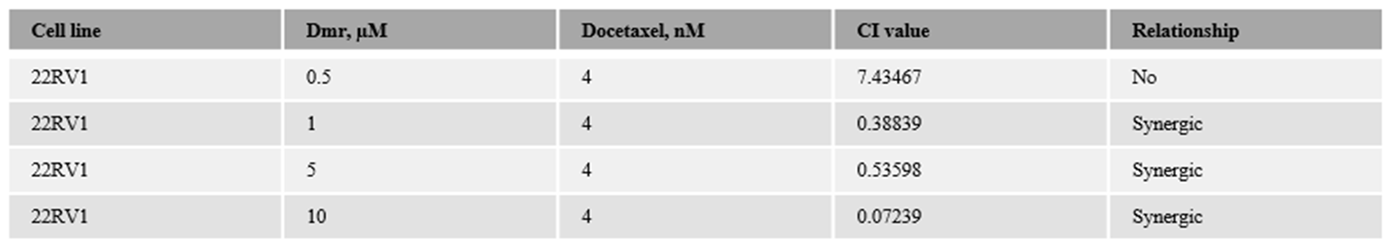

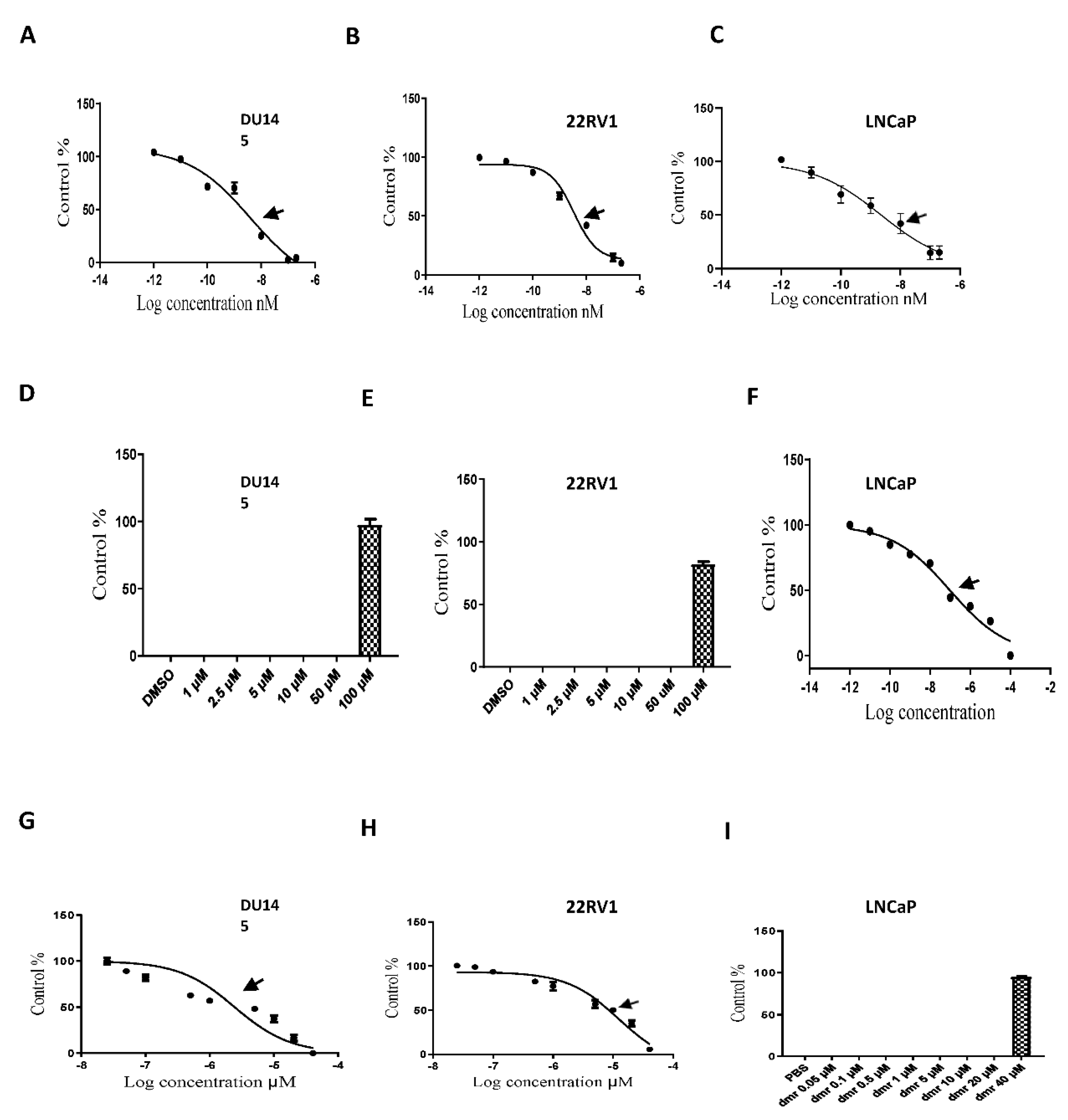

1.1. The combination effect assessment and maximum suppression of dmrFABP5 in combination with docetaxel in PCa cell lines

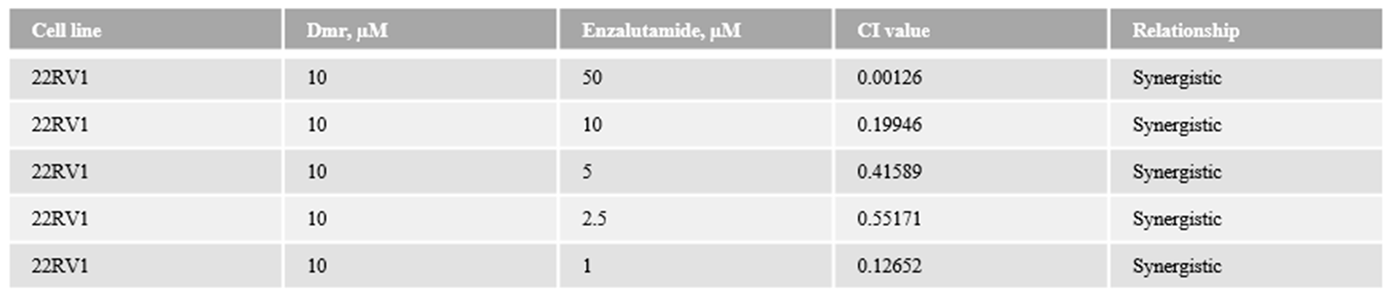

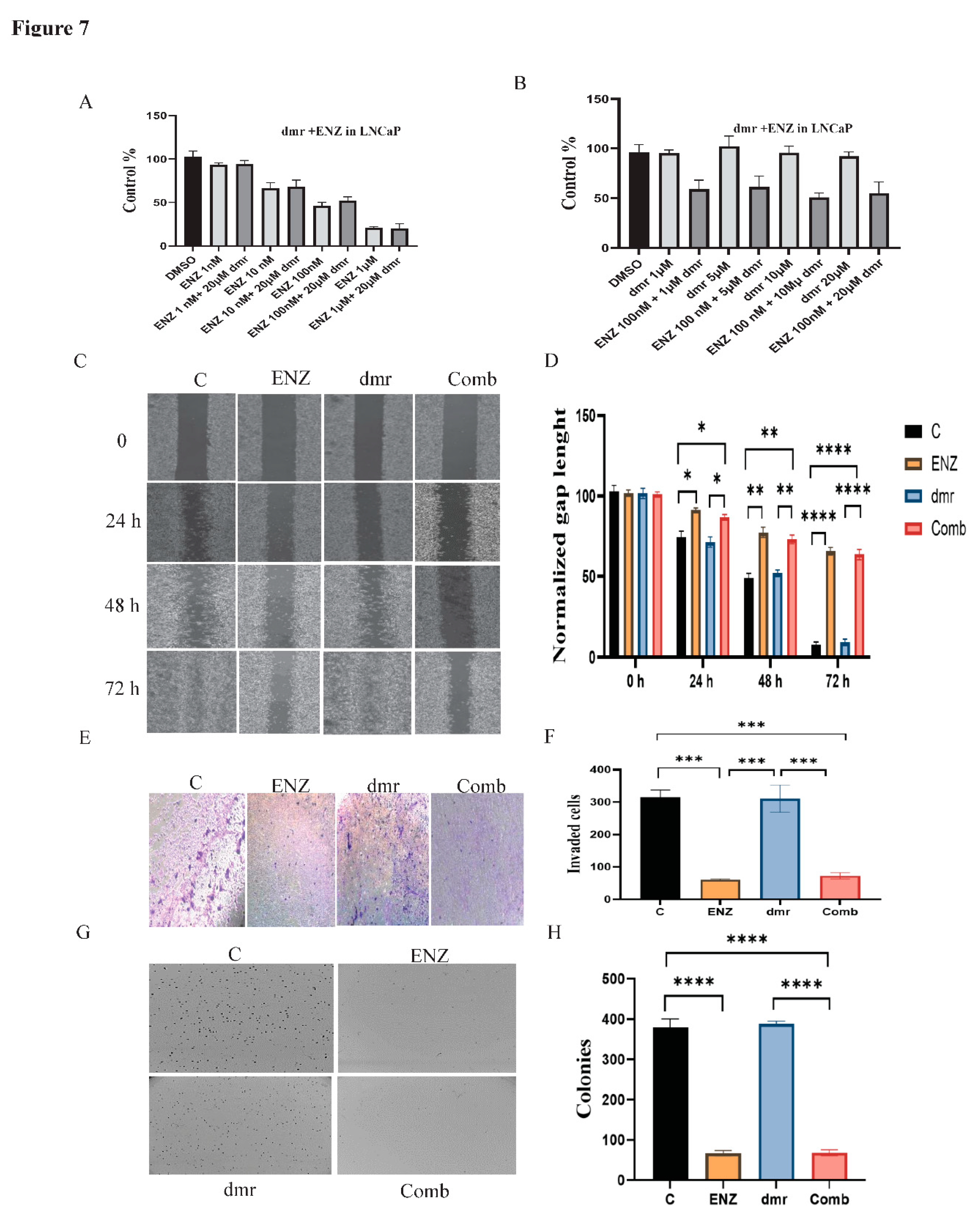

1.1. The combination effect assessment and maximum suppression of dmrFABP5 in combination with enzalutamide in PCa cell lines

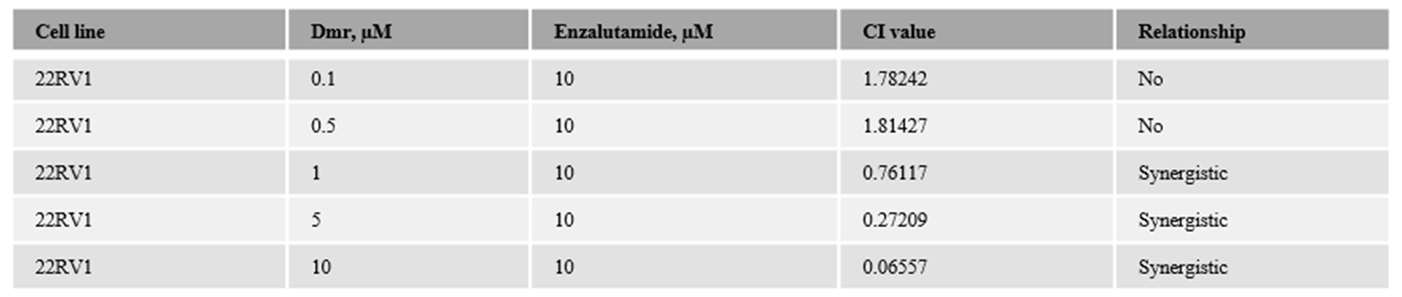

1.1. The effect of dmrFABP5 alone or in combination with docetaxel or enzalutamide on malignant characteristics of PCa cells

1.1.1. Motility assay

1.1.1. Invasion assay

1.1.1. Soft agar assay

1.1.1. Molecular mechanism involved in the combination treatments.

1. Discussion

1. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Sung, H.; Ferlay, J.; Siegel, R.L.; Laversanne, M.; Soerjomataram, I.; Jemal, A.; et al. Global cancer statistics 2020: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA: a cancer journal for clinicians 2021, 71, 209–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Frieling, J.S.; Basanta, D.; Lynch, C.C. Current and emerging therapies for bone metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer. Cancer Control 2015, 22, 109–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Deep, G.; Schlaepfer, I.R. Aberrant lipid metabolism promotes prostate cancer: role in cell survival under hypoxia and extracellular vesicles biogenesis. International Journal of Molecular Sciences 2016, 17, 1061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zadra, G.; Photopoulos, C.; Loda, M. The fat side of prostate cancer. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta (BBA)-Molecular and Cell Biology of Lipids 2013, 1831, 1518–1532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Apte, S.A.; Cavazos, D.A.; Whelan, K.A.; Degraffenried, L.A. A low dietary ratio of omega-6 to omega-3 Fatty acids may delay progression of prostate cancer. Nutrition and cancer 2013, 65, 556–562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levi, L.; Wang, Z.; Doud, M.K.; Hazen, S.L.; Noy, N. Saturated fatty acids regulate retinoic acid signalling and suppress tumorigenesis by targeting fatty acid-binding protein 5. Nature communications 2015, 6, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Forootan, F.S.; Forootan, S.S.; Malki, M.I.; Chen, D.Q.; Li, G.D.; Lin, K.; et al. The expression of C-FABP and PPAR gamma and their prognostic significance in prostate cancer. Int J Oncol 2014, 44, 265–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morgan, E.A.; Forootan, S.S.; Adamson, J.; Foster, C.S.; Fujii, H.; Igarashi, M.; et al. Expression of cutaneous fatty acid-binding protein (C-FABP) in prostate cancer: Potential prognostic marker and target for tumourigenicity-suppression. Int J Oncol 2008, 32, 767–775. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Jing, C.; Beesley, C.; Foster, C.S.; Rudland, P.S.; Fujii, H.; Ono, T.; et al. Identification of the messenger RNA for human cutaneous fatty acid-binding protein as a metastasis inducer. Cancer research 2000, 60, 2390–2398. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Fujita, K.; Kume, H.; Matsuzaki, K.; Kawashima, A.; Ujike, T.; Nagahara, A.; et al. Proteomic analysis of urinary extracellular vesicles from high Gleason score prostate cancer. Scientific reports 2017, 7, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bao, Z.; Malki, M.I.; Forootan, S.S.; Adamson, J.; Forootan, F.S.; Chen, D.; et al. A Novel Cutaneous Fatty Acid–Binding Protein-Related Signaling Pathway Leading to Malignant Progression in Prostate Cancer Cells. Genes & cancer 2013, 4, 297–314. [Google Scholar]

- Forootan, F.S.; Forootan, S.S.; Gou, X.; Yang, J.; Liu, B.; Chen, D.; et al. Fatty acid activated PPARγ promotes tumorigenicity of prostate cancer cells by up regulating VEGF via PPAR responsive elements of the promoter. Oncotarget 2016, 7, 9322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kawaguchi, K.; Kinameri, A.; Suzuki, S.; Senga, S.; Ke, Y.; Fujii, H. The cancer-promoting gene fatty acid-binding protein 5 (FABP5) is epigenetically regulated during human prostate carcinogenesis. Biochemical Journal 2016, 473, 449–461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Naeem, A.A.; Abdulsamad, S.A.; Rudland, P.S.; Malki, M.I.; Ke, Y. Fatty acid-binding protein 5 (FABP5)-related signal transduction pathway in castration-resistant prostate cancer cells: a potential therapeutic target. Precision Clinical Medicine 2019, 2, 192–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Jameel, W.; Gou, X.; Jin, X.; Zhang, J.; Wei, Q.; Ai, J.; et al. Inactivated FABP5 suppresses malignant progression of prostate cancer cells by inhibiting the activation of nuclear fatty acid receptor PPARγ. Genes & cancer 2019, 10, 80. [Google Scholar]

- Berger, W.T.; Ralph, B.P.; Kaczocha, M.; Sun, J.; Balius, T.E.; Rizzo, R.C.; et al. Targeting fatty acid binding protein (FABP) anandamide transporters–a novel strategy for development of anti-inflammatory and anti-nociceptive drugs. PloS one 2012, 7, e50968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaczocha, M.; Rebecchi, M.J.; Ralph, B.P.; Teng,Y. -H.G.; Berger, W.T.; Galbavy, W.; et al. Inhibition of fatty acid binding proteins elevates brain anandamide levels and produces analgesia. PloS one 2014, 9, e94200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J. Molecular mechanisms of the apoptosis-promoting activity of FABP5 inhibitors in prostate cancer cells. The University of Liverpool (United Kingdom); 2019.

- Tannock, I.F.; De Wit, R.; Berry, W.R.; Horti, J.; Pluzanska, A.; Chi, K.N.; et al. Docetaxel plus prednisone or mitoxantrone plus prednisone for advanced prostate cancer. New England Journal of Medicine 2004, 351, 1502–1512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galletti, G.; Leach, B.I.; Lam, L.; Tagawa, S.T. Mechanisms of resistance to systemic therapy in metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer. Cancer treatment reviews 2017, 57, 16–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, M.L.; Horbinski, C.M.; Garzotto, M.; Qian, D.Z.; Beer, T.M.; Kyprianou, N. Tubulin-targeting chemotherapy impairs androgen receptor activity in prostate cancer. Cancer research 2010, 70, 7992–8002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q.; Liu, X. The dual functions of α-tubulin acetylation in cellular apoptosis and autophage induced by tanespimycin in lung cancer cells. Cancer Cell International 2020, 20, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, X.L.; Lin, G.J.; Zhao, H.; Gao, Y.; Qian, L.P.; Xu, S.R.; et al. Inhibitory effects of docetaxel on expression of VEGF, bFGF and MMPs of LS174T cell. World journal of gastroenterology 2003, 9, 1995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, W.; Shiverick, K.T.; Namiki, K.; Sakai, Y.; Porvasnik, S.; Urbanek, C.; et al. Docetaxel and bortezomib downregulate Bcl-2 and sensitize PC-3-Bcl-2 expressing prostate cancer cells to irradiation. World journal of urology 2008, 26, 509–516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, J.X.; Liu, X.; Xu, B. Docetaxel induces apoptosis and influences the expression of P-gp, BCL-2 and BAX protein in HL-60/ADR cells. Zhongguo shi yan xue ye xue za zhi 2010, 18, 311–316. [Google Scholar]

- Higano, C.S.; Beer, T.M.; Taplin, M.E.; Efstathiou, E.; Hirmand, M.; Forer, D.; et al. Long-term safety and antitumor activity in the Phase 1–2 study of enzalutamide in pre-and post-docetaxel castration-resistant prostate cancer. European urology 2015, 68, 795–801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tran, C.; Ouk, S.; Clegg, N.J.; Chen, Y.; Watson, P.A.; Arora, V.; et al. Development of a second-generation antiandrogen for treatment of advanced prostate cancer. Science 2009, 324, 787–790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mostaghel, E.A.; Marck, B.T.; Plymate, S.R.; Vessella, R.L.; Balk, S.; Matsumoto, A.M.; et al. Resistance to CYP17A1 inhibition with abiraterone in castration-resistant prostate cancer: induction of steroidogenesis and androgen receptor splice variants. Clinical cancer research 2011, 17, 5913–5925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, W.; Ryan, C.J. Androgen receptor directed therapies in castration-resistant metastatic prostate cancer. Current treatment options in oncology 2012, 13, 189–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Miyamoto, H.; Messing, E.M.; Chang, C. Androgen deprivation therapy for prostate cancer: current status and future prospects. The Prostate 2004, 61, 332–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dehm, S.M.; Schmidt, L.J.; Heemers, H.V.; Vessella, R.L.; Tindall, D.J. Splicing of a novel androgen receptor exon generates a constitutively active androgen receptor that mediates prostate cancer therapy resistance. Cancer research 2008, 68, 5469–5477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, R.; Dunn, T.A.; Wei, S.; Isharwal, S.; Veltri, R.W.; Humphreys, E.; et al. Ligand-independent androgen receptor variants derived from splicing of cryptic exons signify hormone-refractory prostate cancer. Cancer research 2009, 69, 16–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, Z.; Yang, X.; Sun, F.; Jiang, R.; Linn, D.E.; Chen, H.; et al. A novel androgen receptor splice variant is up-regulated during prostate cancer progression and promotes androgen depletion–resistant growth. Cancer research 2009, 69, 2305–2313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Alsagabi, M.; Fan, D.; Bova, G.S.; Tewfik, A.H.; Dehm, S.M. Intragenic rearrangement and altered RNA splicing of the androgen receptor in a cell-based model of prostate cancer progression. Cancer research 2011, 71, 2108–2117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, R.; Isaacs, W.B.; Luo, J. A snapshot of the expression signature of androgen receptor splicing variants and their distinctive transcriptional activities. The Prostate 2011, 71, 1656–1667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Y.; Hwang, T.H.; Oseth, L.; Hauge, A.; Vessella, R.L.; Schmechel, S.C.; et al. AR intragenic deletions linked to androgen receptor splice variant expression and activity in models of prostate cancer progression. Oncogene 2012, 31, 4759–4767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Antonarakis, E.S.; Lu, C.; Wang, H.; Luber, B.; Nakazawa, M.; Roeser, J.C.; et al. AR-V7 and resistance to enzalutamide and abiraterone in prostate cancer. New England Journal of Medicine 2014, 371, 1028–1038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Harris, W.P.; Mostaghel, E.A.; Nelson, P.S.; Montgomery, B. Androgen deprivation therapy: progress in understanding mechanisms of resistance and optimizing androgen depletion. Nature clinical practice Urology 2009, 6, 76–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cella, D.; Peterman, A.; Hudgens, S.; Webster, K.; Socinski, M.A. Measuring the side effects of taxane therapy in oncology: The Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy–taxane (FACT-taxane). Cancer: Interdisciplinary International Journal of the American Cancer Society 2003, 98, 822–831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baker, J.; Ajani, J.; Scotté, F.; Winther, D.; Martin, M.; Aapro, M.S.; et al. Docetaxel-related side effects and their management. European journal of oncology nursing 2009, 13, 49–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Merseburger, A.S.; Haas, G.P.; von Klot, C.A. An update on enzalutamide in the treatment of prostate cancer. Therapeutic advances in urology 2015, 7, 9–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Naeem, A.A.; Abdulsamad, S.A.; Al-Bayati, A.; Zhang, J.; Malki, M.I.; Ma, H.; et al. Prostate Cell Lines. Journal of Oncology and Medicine 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Mitchell, S.; Abel, P.; Ware, M.; Stamp, G.; Lalani, E.N. Phenotypic and genotypic characterization of commonly used human prostatic cell lines. BJU international 2000, 85, 932–944. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forootan, F.S.; Forootan, S.S.; Malki, M.I.; Chen, D.; Li, G.; Lin, K.; et al. The expression of C-FABP and PPARγ and their prognostic significance in prostate cancer. Int J Oncol 2014, 44, 265–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chou, T.-C. Drug combination studies and their synergy quantification using the Chou-Talalay method. Cancer research 2010, 70, 440–446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ross, R.W.; Xie, W.; Regan, M.M.; Pomerantz, M.; Nakabayashi, M.; Daskivich, T.J.; et al. Efficacy of androgen deprivation therapy (ADT) in patients with advanced prostate cancer: association between Gleason score, prostate-specific antigen level, and prior ADT exposure with duration of ADT effect. Cancer: Interdisciplinary International Journal of the American Cancer Society 2008, 112, 1247–1253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Coutinho, I.; Day, T.K.; Tilley, W.D.; Selth, L.A. Androgen receptor signaling in castration-resistant prostate cancer: a lesson in persistence. Endocrine-related cancer 2016, 23, T179–T97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forootan, S.S.; Hussain, S.; Aachi, V.; Foster, C.S.; Ke, Y. Molecular mechanisms involved in the transition of prostate cancer cells from androgen dependant to castration resistant state. Journal of Andrology and Gynaecology 2014, 2, 1–9. [Google Scholar]

- Merseburger, A.S.; Haas, G.P.; von Klot, C.A. An update on enzalutamide in the treatment of prostate cancer. Ther Adv Urol 2015, 7, 9–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zobniw, C.M.; Causebrook, A.; Fong, M.K. Clinical use of abiraterone in the treatment of metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer. Res Rep Urol 2014, 6, 97–105. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Karantanos, T.; Corn, P.G.; Thompson, T.C. Prostate cancer progression after androgen deprivation therapy: mechanisms of castrate resistance and novel therapeutic approaches. Oncogene 2013, 32, 5501–5511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katzenwadel, A.; Wolf, P. Androgen deprivation of prostate cancer: Leading to a therapeutic dead end. Cancer letters 2015, 367, 12–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, K.; Ruan, H.; Xu, T.; Liu, L.; Liu, D.; Yang, H.; et al. Recent advances on the progressive mechanism and therapy in castration-resistant prostate cancer. Onco Targets Ther 2018, 11, 3167–3178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; He, G.; Jin, X.; Alenezi, B.T.; Naeem, A.A.; Abdulsamad, S.A.; et al. Molecular mechanisms on how FABP5 inhibitors promote apoptosis-induction sensitivity of prostate cancer cells. Cell Biology International 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, Z.; Li, J.; Liu, Y.; Shi, Z.; Xuan, Z.; Yang, K.; et al. The Crucial Role of AR-V7 in Enzalutamide-Resistance of Castration-Resistant Prostate Cancer. Cancers 2022, 14, 4877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Y.; Dalrymple, S.L.; Coleman, I.; Zheng, S.L.; Xu, J.; Hooper, J.E.; et al. Role of androgen receptor splice variant-7 (AR-V7) in prostate cancer resistance to 2nd-generation androgen receptor signaling inhibitors. Oncogene 2020, 39, 6935–6949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khurana, N.; Kim, H.; Chandra, P.K.; Talwar, S.; Sharma, P.; Abdel-Mageed, A.B.; et al. Multimodal actions of the phytochemical sulforaphane suppress both AR and AR-V7 in 22Rv1 cells: Advocating a potent pharmaceutical combination against castration-resistant prostate cancer. Oncology Reports 2017, 38, 2774–2786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carbonetti, G.; Wilpshaar, T.; Kroonen, J.; Studholme, K.; Converso, C.; d’Oelsnitz, S.; et al. FABP5 coordinates lipid signaling that promotes prostate cancer metastasis. Scientific reports 2019, 9, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forootan, S.S.; Bao, Z.Z.; Forootan, F.S.; Kamalian, L.; Zhang, Y.; Bee, A.; et al. Atelocollagen-delivered siRNA targeting the FABP5 gene as an experimental therapy for prostate cancer in mouse xenografts. Int J Oncol 2010, 36, 69–76. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).