1. Introduction

In today's healthcare settings, technology has advanced and become more complex. As a result, healthcare services emphasize evidence-based practice [1-3], and nurses are facing new challenges of immediate clinical management to provide safer and higher quality of patient care [

4,

5]. Nurses are required to be more independent and competent in managing a wide range of complex situations. Therefore, it is essential to train nursing students to achieve the required competence standard for complex clinical situations, which includes problem-solving (PS) and clinical reasoning (CR) skills [5-7]. High-fidelity patient simulation (HFPS) is an innovative and effective methods that provides a learning environment for students to apply integrated knowledge and psychomotor skills in a simulated case scenario [8-10]. This real-life learning opportunity allows students to develop higher intellectual skills, such as PS and CR, for more appropriate clinical decision-making [

11]. A HFPS guideline is essential to e provide clear directions to guide students step by step from preparation to debriefing after HFPS and enable them to learn more effectively [

12]. Students are required to be engaged in the activity and perform with their learned knowledge and skills [

8,

10,

13]. In the current nursing curriculum, HFPS is employed in various nursing disciplinary courses and clinical learning workshops to enhance students’ understanding about patients’ conditions and related treatment and care. A HFPS guideline provides systematic approaches to allow students to engage in their learning tasks, perform what they have learned, and evaluate how they have performed throughout the learning process of HFPS. It is necessary to examine the effects of structured HFPS guidelines on PS and CR abilities.

With the increased complexity of healthcare services, nurses are expected to have greater accountability and independence to provide appropriate quality of patient care [

2]. In current nursing education, students are required to equip themselves with sophisticated skills and knowledge to achieve the highest competent standards for better quality and safer patient care [

14,

15]. It is crucial to allow students to develop abilities in clinical judgement and decision-making by applying evidence-based knowledge and skills [

16]. Classroom and laboratory learning limit students’ personal experience in performing knowledge and skills through an explicit thinking process to real situations. This thinking process involves PS and CR, which are essential abilities that facilitate students to make appropriate decisions considering multiple factors [

16,

17].

PS is the intellectual and analytic process that finds solutions to problems in specific contexts [

18], while CR is the ability to integrate and apply the learned knowledge and experience, use and weigh the relevant evidence, and think critically about arguments until the final decision is made [

19]. PS and CR are intertwined and crucial for competent practice and clinical judgements in nursing practice, embedding a series of critical thinking, integration of knowledge and skills, professional and personal experiences, and analysis [

20,

21]. Facing more obligation in clinical judgement and decision-making, nursing students are trained to manage complex situations using various teaching–learning modes.

HFPS is an advanced and innovative teaching-learning method that uses a computerised manikin with a simulated real-life scenario to allow students to integrate their knowledge and skills based on their clinical decisions [

22]. HFPS has been extensively and favourably used in educational and clinical training in the past decades to strengthen students’ PS and CR abilities [

2,

9]. This method provides a better learning environment for nursing students to practice in simulated diverse clinical situations [

23]. Through HFPS, students practise self-directed learning in preparation and processing of CR and PS for effective and appropriate decision-making targeting complex and uncertain situations [

20,

21]. Students also experience their roles and responsibilities in a simulated clinical setting and understand more about their strengths and weaknesses so that they can improve accordingly [

23]. In that sense, CR and PS are vital abilities to enhance students’ competence in clinical performance [

19,

21]. Moreover, HFPS provides a learning environment for team collaboration through small group works. Students working in a small group can develop collaborative attributes, better learning motivation, and higher intellectual skills [24-27]. Therefore, students can interact and collaborate with their peers to exchange their learning experience, enhancing their competence in nursing practice and teamwork skills in HFPS. Student learning can also be more dynamic and definite to incorporate more CR and PS. However, PS has been reported to remain unaffected by HFPS among nursing students due to the lack of a systematic educational strategy [

2,

17]. Hence, a HFPS guideline with education and management strategies was designed to enhance students’ knowledge acquisition and skill development. This study aimed to examine the effects of a HFPS guideline on PS and CR skills among undergraduate nursing students.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Design

This pre-and post-experimental was conducted at a single tertiary professional training institution.

2.2. Participants

Students who 1) were in the first-year undergraduate programmes and 2) were aged ≥18 years were recruited. Those who 1) had been enrolled in another course with HFPS or 2) have had clinical placement were excluded to avoid contamination.

The sample size was calculated to reach a desired power of 0.95 and a type I error of 0.05 with an effect size of 0.5 using G-Power. The required calculated minimum number of participants was 176 students. The eligible students were requested to join a group at their favourable timeslot. When the group size reached 8 to 10 students, the research assistant (RA) would inform the educator. The RA was not involved in the implementation of HFPS.

2.3. A HFPS Guideline as the Study Framework

This study utilized a HFPS guideline provide a systematic approach in four major sessions of HFPS, including preparation, pre-briefing and orientation, simulation role-playing, and debriefing, to guide educators and students in the simulated activities. During the pre-briefing, students were required to read rules and regulations, learning objectives, and learning materials for the HFPS. The learning materials contained information about the health problem of the simulated patient and its related medical and nursing care. Additionally, students were introduced to the simulation environment and equipment before the role-play session. A scenario was designed for the simulation-based intervention. During the role-play session, students worked in small groups and provided nursing care based on the health needs of the simulated patient. Finally, in the debriefing, students were required to reflect on their learning based on their role-playing performance. The educator served as the facilitator during the HFPS.

2.4. Instruments

2.4.1. Problem-Solving Inventory (PSI)

The PSI developed by Heppner and Petersen [

28] is used to measure individuals’ perceptions regarding their PS abilities and styles in daily life. It consists of 32 items scored on a 6-point Likert scale, ranging from 1 (strongly agree) to 6 (strongly disagree). The PSI includes three subscales: Problem-Solving Confidence (PSC) (11 items), Approach-Avoidance Style (AAS) (16 items), and Personal Control (PC) (5 items). The PSC subscale assesses self-perceived confidence, belief, and self-assurance in effectively solving problems. Higher scores indicate lower levels of PS confidence. The AAS subscale measures an individual’s tendency of response to approach or avoid problems. Higher scores reflect avoidance rather than approaching problems. The PC subscale assesses elements of self-control on emotions and behaviours. Higher scores indicate a more negative perception of personal control of problems. The total PSI score ranges from 32 to 192. Lower total PSI scores indicate more functional PS abilities. The reliability of the subscales and the overall scale was good to very good with Cronbach’s alpha of PSC, AAS, PC, and overall PS at 0.819, 0.810, 0.710, and 0.892, respectively.

2.4.2. Nurses Clinical Reasoning Scale (NCRS)

The NCRS developed by Liou et al. [

29] assesses students’ CR competence. This self-reported tool includes 15 items scored on a five-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree). Higher scores indicate higher CR competence. The Cronbach’s alpha of the NCRS was 0.952, indicating excellent reliability.

2.4.3. Data Collection

The RA was responsible for student recruitment by sending emails with the study purpose and information to all potential students. Once a group was formed, the RA contacted the eligible students and assigned them into their groups. Students in the intervention group were asked to join the HFPS using the newly structured HFPS guideline and those in the control group using the standard HFPS instruction. Two researchers were the facilitators – one in the intervention group and the other in the control group. Different venues were assigned to avoid contamination. On the day of HFPS, the students were divided into three small groups and took turns to provide care for the simulated patient. While one small group was performing in the simulation, another two small groups were requested to watch the real-time simulation and write down their comments on the performance of the group. Each small group had 20 minutes to perform in the simulation. After the simulation, debriefing was performed for improvement.

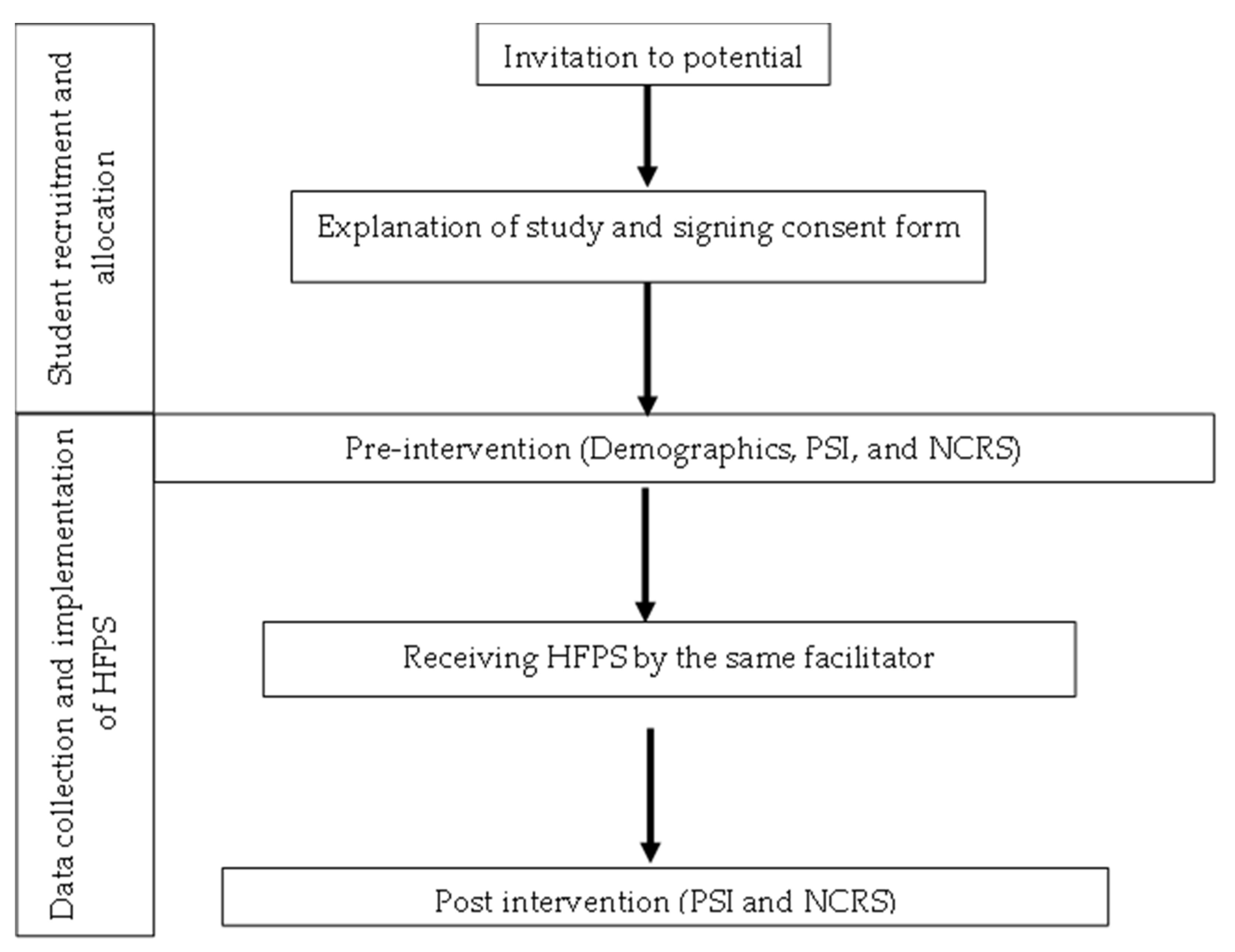

Figure 1 illustrates the flow of data collection and study implementation.

4.2.4. Ethical Consideration

Ethical approval (REC2021102) was sought from our Institutional Research Committee. Informed consent was obtained from the students after the study purpose and procedure were explained to them. All data related to personal information were kept confidential.

4.2.5. Data Analysis

Statistical analyses were performed using IBM SPSS version 26. Descriptive statistics were used for the demographic variables, including age, sex, study year, and study programme, and the outcomes of the intervention and control groups were presented separately. A paired t-test was performed to compare the PS and CR abilities before and after the HFPS. All statistical tests involved were two-sided, and p-values of <0.05 were considered statistically significant.

3. Results

3.1. Student Characteristics

A total of 189 students participated in this RCT without attrition. The mean age was 20.56 years (standard deviation=3.14).

Table 1 shows the detailed demographic characteristics.

3.2. PS and CR Abilities of the Two Groups

Table 2 illustrates the descriptive results of the PS and CR abilities before and after the HFPS. The descriptive analysis showed that the PS and CR abilities had certain improvements after the HFPS. The bivariate analysis revealed that only age was negatively associated with the PSC subscale score (γ = -0.161, p = 0.027) and overall PSI score (γ = -0.147, p = 0.044).

3.3. Comparison bewteen Two Periods

In the paired samples t-test (

Table 3), there were significant differences observed in the PSC subscale score (p < 0.001), overall PSI score (p < 0.001), and NCRS score (p < 0.001) between the two periods of HFPS.

4. Discussion

HFPS is an innovative teaching‒learning method used to develop students’ PS and CR abilities to enhance their clinical judgement and decision-making skills [

2,

7,

19]. This study revealed that HFPS effectively enhances the PS and CR abilities in first-year students. Comparing the PS domains and CR between the two periods, the PSC subscale score (p < 0.001), overall PSI score (p < 0.001), and NCRS score (p < 0.001) significantly improved. Notably, the HFPS significantly improves students’ PS confidence leading to improve their PS ability and increases their CR ability. The HFPS provides a good learning and practice environment to students to apply their knowledge and skills to the simulated patient [

9,

12,

23]. Students have their PS and CR improvement is attributed to the guideline with four sessions – preparation, pre-briefing and orientation, simulation role-playing, and debriefing. The guideline provides adequate instruction to facilitate student learning and guidance to allow students to be engaged in each HFPS session.

In the pre-briefing, students receive related learning materials to prepare and the orientation of the simulation environment for their role play in the HFPS. Through students’ self-study and environmental recognition, they were able to increase their knowledge and apply their skills, so they had more confidence to handle clinical situations. Pre-reading relevant learning materials related to the simulated patient can foster students’ confidence in PS to cope with problems more effectively and hence develop their clinical judgement ability [

7,

9]. Substantial evidence shows that HFPS is a crucial component in enhancing clinical experience and clinical management skills [

16,

30]. A case scenario designed with a specific health problem for the HFPS allows students to experience clinical practice and patient care. During the role-playing, students are required to be more engaged in the simulated clinical scenario. Adequate preparation enhances students’ awareness and application of learned knowledge and skills in the simulated clinical situation. It also helps them express high levels of critical thinking and PS abilities for the provision of safe and appropriate patient care during HFPS [

31]. The simulated patient’s concerns are challenging, and their responses are promising, increasing their confidence in real clinical practice. Accordingly, the PS and CR abilities of the two groups in this study improved. HFPS also focuses on teamwork and enables students to provide immediate management according to the client’s needs and condition [

9]. Working in a small group is beneficial in enhancing knowledge and developing skills, including high intellectual skills, such as communication, PS, critical thinking, and collaborative skills [24-26]. Since students are required to work as a team in HFPS, they collaborate with other team members for decision-making and develop their personal and professional strengths altogether.

During the role-playing and the debriefing, the facilitator plays an important role in engaging students in learning through the HFPS more effectively [

23,

30]. The facilitator provides timely guidance for students to perform and react to problems in various environmental diversions. In the debriefing, the facilitator allows students to reflect on their learning and provides appropriate guidance for more effective clinical judgments and decision-making accordingly [

13]. Both self and peer reflection can further enhance students’ understanding to perform more competently.

Based on the findings of PS and CR improvement through HFPS, the HFPS guideline with adequate instruction, learning materials, and expected learning outcomes is essential to positively provide students systematic direction and support so that students achieve PS and CR development more effectively. Taken together, this study successfully demonstrated the benefits of the structured HFPS guideline for student learning and skill development, including better preparation to increase knowledge acquisition and skill application, development of collaborative attributes, and enhancement of higher intellectual skills, such as PS and CR. Therefore, the structured guideline should be added to the courses with HFPS in the nursing curriculum. The results also promote the awareness of nurse educators to design HFPS guidelines and further enhance students’ PS and CR abilities that are crucial for clinical judgement and decision-making, even in junior years.

Strengths and Limitations

This study enables a direct comparison of the outcome measures between two stages of HFPS, providing reliable and accurate evidence of the intervention’s effects. However, the recruitment of students at a single professional training institution limits the generalisability of the results and the ability to draw causal inferences. To increase generalisability, a similar study should be conducted in multiple centres.

5. Conclusions

HFPS has recently emerged as a highly favourable teaching‒learning method. The HFPS guideline in this study provides clear directions for students to prepare and enhance their knowledge and skills in clinical judgement and decision-making. Additionally, the HFPS guideline significantly improves PS and CR abilities before and after participating HFPS. Throughout the learning process of HFPS, students not only apply their knowledge and skills but also increase their awareness and application of appropriate practice, embedding a series of PS and CR.

This study has significant implications for nursing education. As the use of HFPS continues to increase in professional training, including nursing, the findings highlight the importance of a HFPS guideline to improve student learning and competence in practising through HFPS, leading to better development of PS and CR abilities. Therefore, a HFPS guideline is crucial in enhancing students’ personal and professional development for more appropriate and safer clinical decisions and judgements.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, F.W.; methodology, F.W., A.C. & N.L; validation, F.W., A.C. & N.L; formal analysis, F.W. A.C., & N.L; investigation, F.W. A.C., & N.L., K.L.; resources, F.W. A.C., & N.L., K.L.; data curation, F.W. A.C., & N.L., K.L..; writing—original draft preparation, F.W.; writing—review and editing, F.W. A.C., & N.L., K.L.; visualization, F.W.; & A.L.; supervision, F.W.; project administration, F.W. A.C., & N.L., K.L.; funding acquisition, F.W. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by Tung Wah College, grant number SRG21040.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Institutional Review Board of Tung Wah College (protocol code REC2021102 and approval on 23 September 2021).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Acknowledgments

We would like to acknowledge Professor Heppner and Peterson and Dr. Liou for their kind generosity of their permission to use their instruments, Problem-Solving Inventory (PSI) and Nurses Clinical Reasoning Scale (NCRS), respectively, in our study.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

References

- Cadorin, L.; Suter, N.; Dante, A.; Williamson, S.N.; Devetti, A.; Palese, A. Self-directed learning competence assessment within different healthcare professionals and amongst students in Italy. Nurse Educ Pract. 2012, 12, 153–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, J.; Lee, Y.; Lee, S.; Bae, J. Effects of high-fidelity patient simulation led clinical reasoning course: Focused on nursing core competencies, problem solving, and academic self-efficacy. Jpn J Nurs Sci. 2016, 13, 20–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, G.F.; Jiang, X.Y. Self-directed learning readiness and nursing competency among undergraduate nursing students in Fujian province of China. IJNSS 2014, 1, 255–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ironside, P.M.; Jeffries, P.R.; Martin, A. Fostering patient safety competencies using multiple-patient simulation experiences. Nurs Outlook. 2009, 57, 332–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Levett-Jones, T. Clinical Reasoning: Learning to Think Like a Nurse, 2nd ed.; Pearson, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Dalton, L.; Gee, T.; Levett-Jones, T. Using clinical reasoning and simulation-based education to ‘flip’ the enrolled nurse curriculum. AJAN. 2015, 33, 2–15. [Google Scholar]

- Gopalakrishnan, P.; Sethuraman, K.R.; Suresh, P. Efficacy of high-fidelity simulation in clinical problem-solving exercises - Feedback from teachers and learners. SBV JBCAHS. 2018, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gates, M.G.; Parr, M.B.; Hughen, J.E. Enhancing nursing knowledge using high-fidelity simulation. J Nurs Educ. 2012, 51, 9–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Powell, E.; Scrooby, B.; van Graan, A. Nurse educators’ views on implementation and use of high-fidelity simulation in nursing programmes. Afr. J. Health Prof. Educ. 2020, 12, 215–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Welman, A.; Spies, C. High-fidelity simulation in nursing education: Considerations for meaningful learning. Trends in Nursing 2016, 3, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Linn, A.; Khaw, C.; Kildea, H.; Tonkin, A. Clinical reasoning: A guide to improving teaching and practice. AFP. 2021, 41, 18–20. [Google Scholar]

- Silva, J.L.G.; Oliveira-Kumakura, A.R.S. Clinical simulation to teach nursing care for wounded patients. Revista Latino-Americana de Enfermagem 2018, 71 (Suppl. 4), 1785–1790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tawalbeh, L.I.; Tubaishat, A. Effect of simulation on knowledge of advanced cardiac life support, knowledge retention, and confidence of nursing students in Jordan. J. Nurs. Educ. 2014, 53, 38–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blum, C.A.; Borglund, S.; Parcells, D. High-fidelity nursing simulation: Impact on student self-confidence and clinical competence. Int J Nurs Educ Scholarsh. 2010, 7, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shirazi, F.; Kazemipoor, H.; Tavakkoli-Moghaddam, R. Fuzzy decision analysis for project scope change management. Decision Science Letters 2017, 6, 395–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaliyaperumal, R.; Raman, V.; Kannan, L.; Ali, M.D. Satisfaction and self-confidence of nursing students with simulation teaching. IJHSR. 2021, 11, 44–50. [Google Scholar]

- Kelleci, M.; Yilmaz, F.T.; Aldemir, K. The effects of high-fidelity simulation training on critical thinking and problem solving in nursing students in Turkey. Educ. Res. Rev. 2018, 7, e83966. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jonassen, D.H.; Hung, W. Problem solving. In Seel N. M. (Ed.) Encyclopedia of the sciences of learning. 2012. Springer, Boston, MA. [CrossRef]

- Hong, S.; Lee, J.; Jang, Y.; Lee, Y. A cross-sectional study: What contributes to nursing students’ clinical reasoning competence? IJERPH. 2021, 18, 6833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guerrero, J.G.; Ali, S.A.A.; Attallah, D.M. The acquired critical thinking skills, satisfaction, and self-confidence of nursing students and staff nurse through high-fidelity simulation experience. Clin Simul Nurs. 2022, 64, 24–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vyas, D.; Ottis, E.J.; Caligiuri, F.J. Teaching clinical reasoning and problem-solving skills using human patient simulation. Am J Pharm Educ. 2011, 75, 189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cura, S.Ü.; Kocatepe, V.; Yıldırım, D.; Küçükakgün, H.; Atay, S.; Ünver, V. Examining knowledge, skill, stress, satisfaction, and self-confidence levels of nursing students in three different simulation modalities. Asian Nurs Res. 2020, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Huang, F.F.; Chen, S.S.; Wang, A.; Guo, Y. The learning effectiveness of high-fidelity simulation teaching among Chinese nursing students: A mixed-methods study. J Nurs Res. 2021, 29, e141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wong, F.M.F. A cross-sectional study: Collaborative learning approach enhances learning attitudes of undergraduate nursing students. GSTF JNHC. 2017, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong, F.M.F. A phenomenological research study: Perspectives of student learning through small group work between undergraduate nursing students and educators. Nurse Educ Today. 2018, 68, 153–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wong, M.F.F. Development of higher-level intellectual skills through interactive group work: Perspectives between students and educators. Med Clin Res. 2020, 5, 164–169. [Google Scholar]

- Wong, F.M.F.; Tang, A.C.Y.; Cheng, W.L.S. Factors associated with self-directed learning among undergraduate nursing students: A systematic review. Nurse Educ Today. 2021, 104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heppner, P.P.; Petersen, C.H. The development and implications of a personal problem-solving inventory. J Couns Psychol. 1982, 29, 66–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liou, S.R.; Liu, H.C.; Tsai, H.M.; Tsai, Y.H.; Lin, Y.C.; Chang, C.H.; Cheng, C.Y. The development and psychometric testing of a theory-based instrument to evaluate nurses' perception of clinical reasoning competence. JAN. 2016, 72, 707–717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hustad, J.; Johannesen, B.; Fossum, M.; Hovland, O. J. Nursing students’ transfer of learning outcomes from simulation-based training to clinical practice: A focus-group study. BMC Nurs. 2019, 18, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lewis, D.; Ciak, A. The impact of a simulation lab experience for nursing students. Nurs Educ Perspect. 2011, 32, 256–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).