Submitted:

06 July 2023

Posted:

07 July 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

Introduction

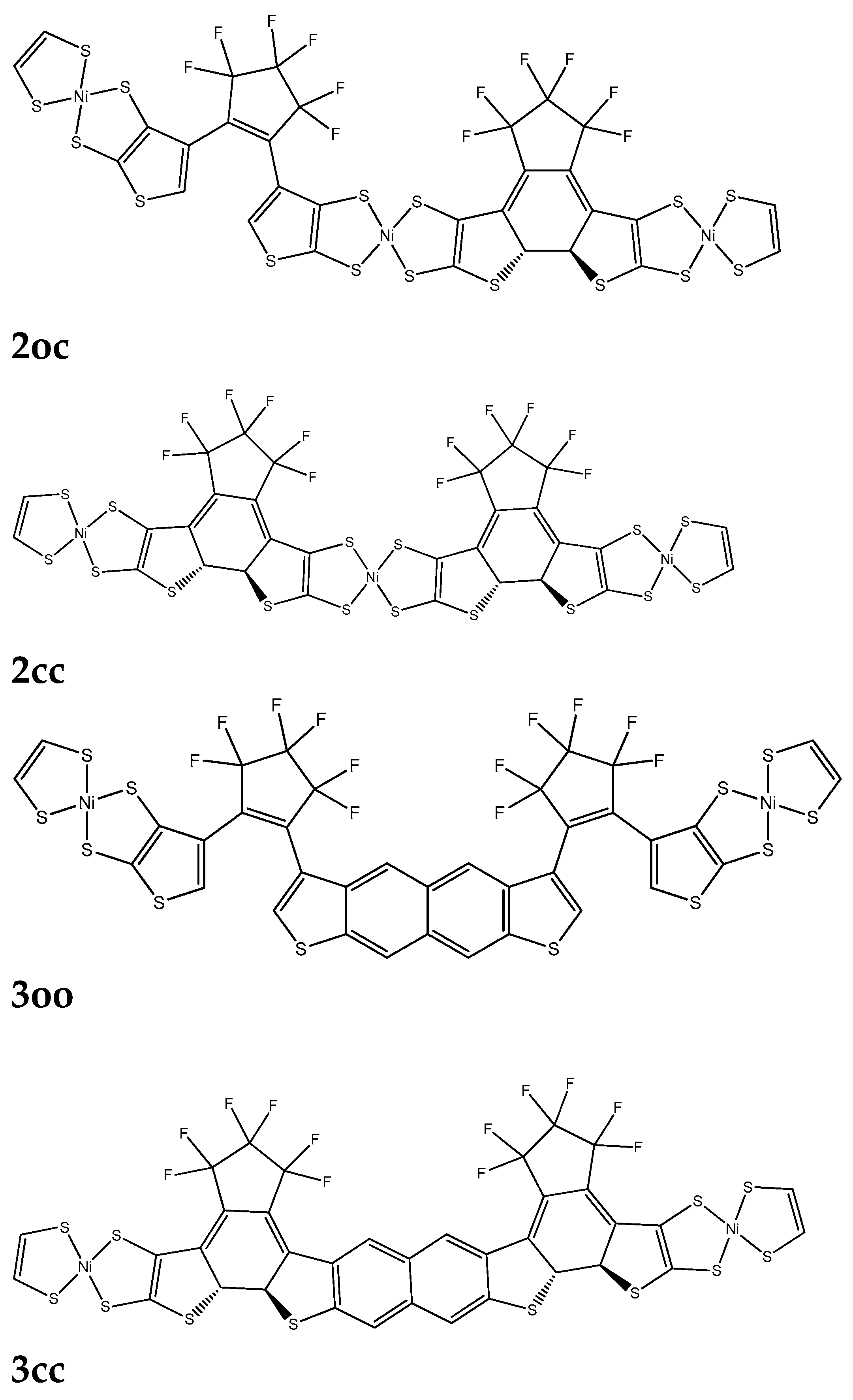

The effect of the bridge on the electronic coupling

Computation of EET

II. Methods

II.1. Definitions

II.2. Functionals and Basis sets

II.3 Two-photon absorption

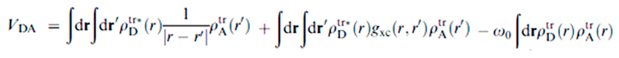

ΙΙ.4 Computation of the Electronic Coupling:

III. Results and Discussion

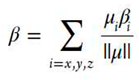

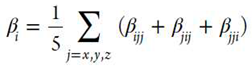

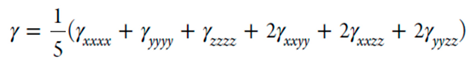

III.1 (Hyper)polarizabilities

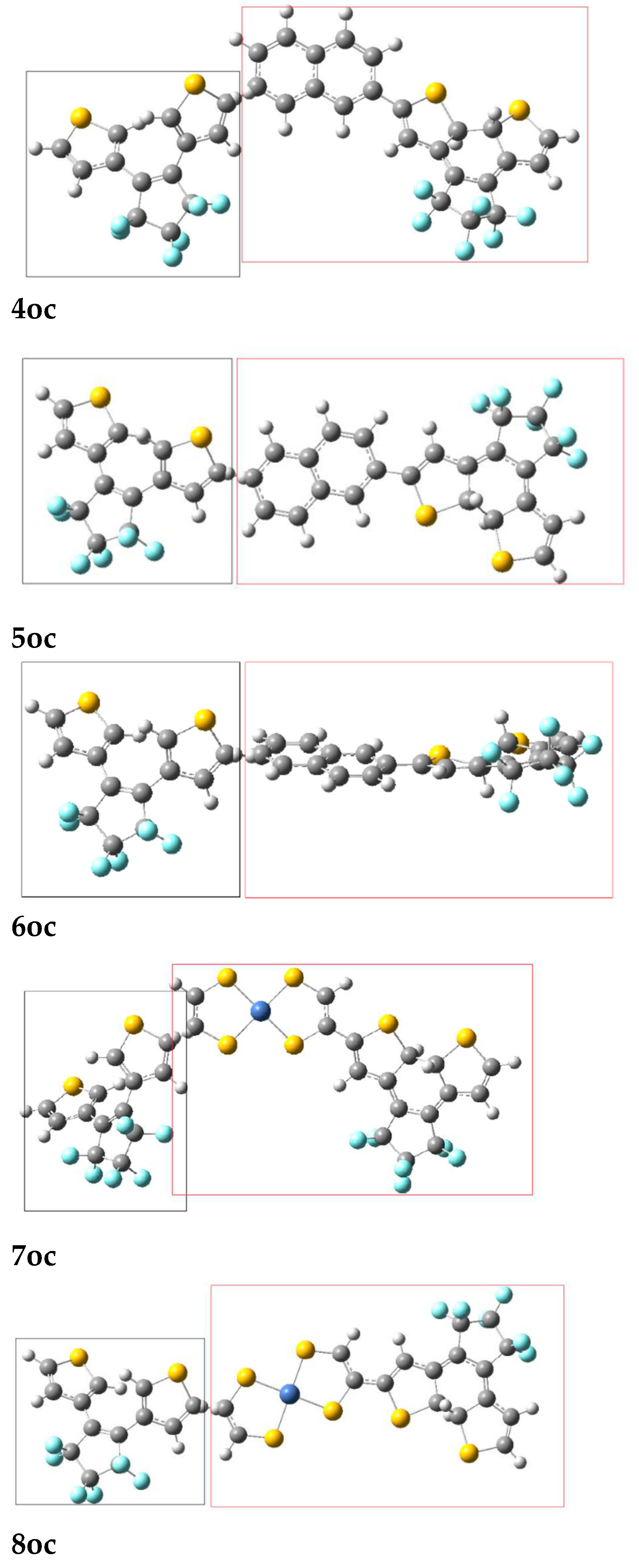

| α | β | γ (x103) | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| R | 1cc | 1co | 1oo | 1cc | 1co | 1oo | 1cc | 1co | 1oo |

| H | 972.6 1049.53 |

882.3 | 796.9 | 680 7903 |

14860 | 150 | 14111 146603 |

8476 | 4078 |

| Cl | 1025.4 1108.03 914.04 |

926.0 824.64 |

827.2 776.74 |

1200 12503 19604 |

20860 117004 |

243 1444 |

15635 162703 86544 |

9299 47194 |

4185 28374 |

| NO2 | 1123.8 | 988.8 | 842.5 | 257 | 48040 | 773 | 22841 | 13260 | 4284 |

| NH2 | 1024.4 | 918.9 | 822.2 | 530 | 401 | 486 | 16212 | 8949 | 4208 |

| Ph | 1239.1 | 1096.1 | 960.8 | -310 | 10140 | 150 | 23611 | 12378 | 4692 |

| NO2/ NH21 | 1094 | 930.0 | 832.4 | 71350 | 2950 | 4950 | 25370 | 9049 | 4272 |

| NO2/NH22 | 988.0 | 61260 | 14861 | ||||||

| Derivative | λ | α | β | γ(x103) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2oo | 622.31 | 880.31 | -4101 | 27411 |

| 2oc | 884.11 | 11631 12252 |

13491 13302 |

174001 192362 |

| 2cc | 994.31 | 1576.91 1652.52 |

-140761 -130802 |

678701 688902 |

| 3oo | 614.01 | 792.91 | 4321 | 14161 |

| 3cc | 878.91 | 1129.61 | 58001 | 139711 |

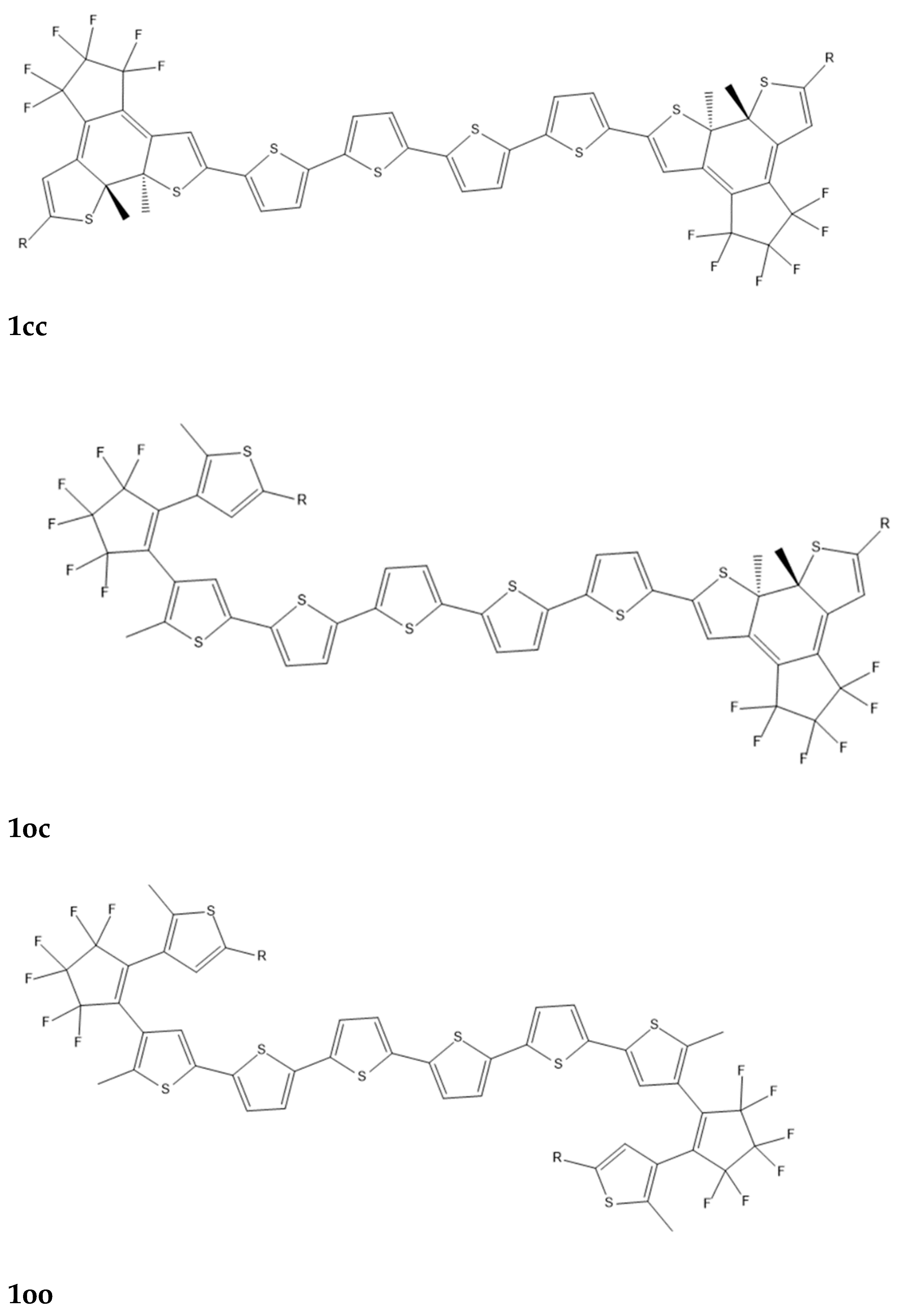

A. Oligothiophenes

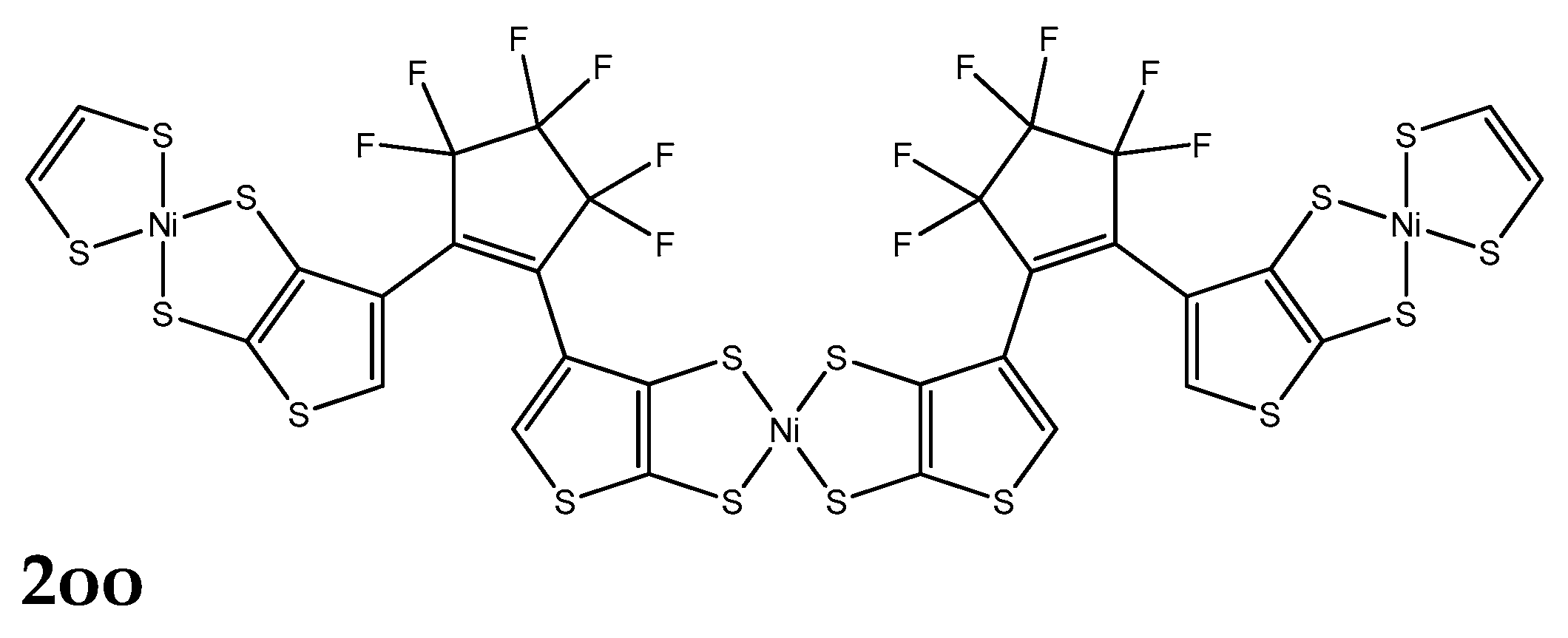

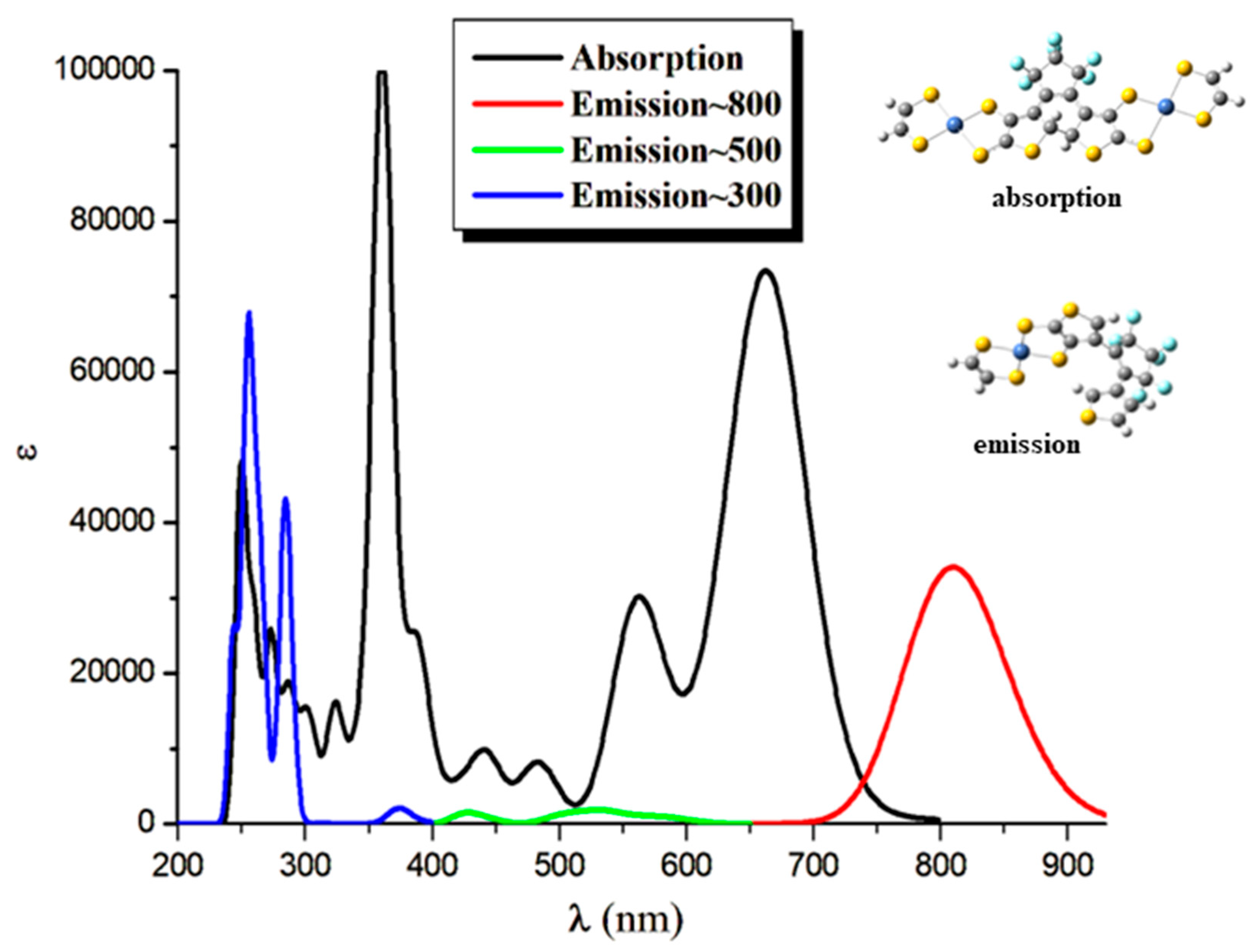

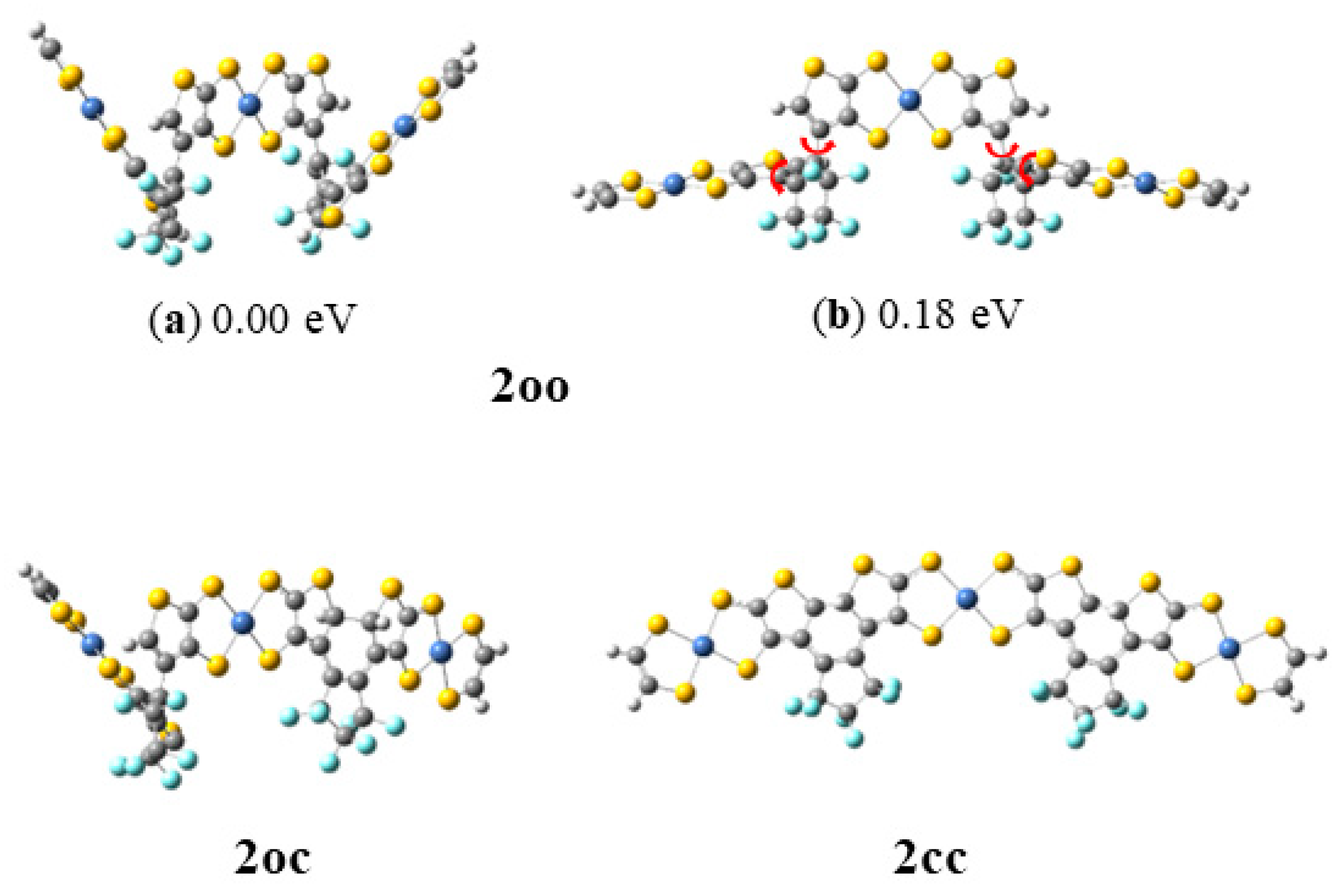

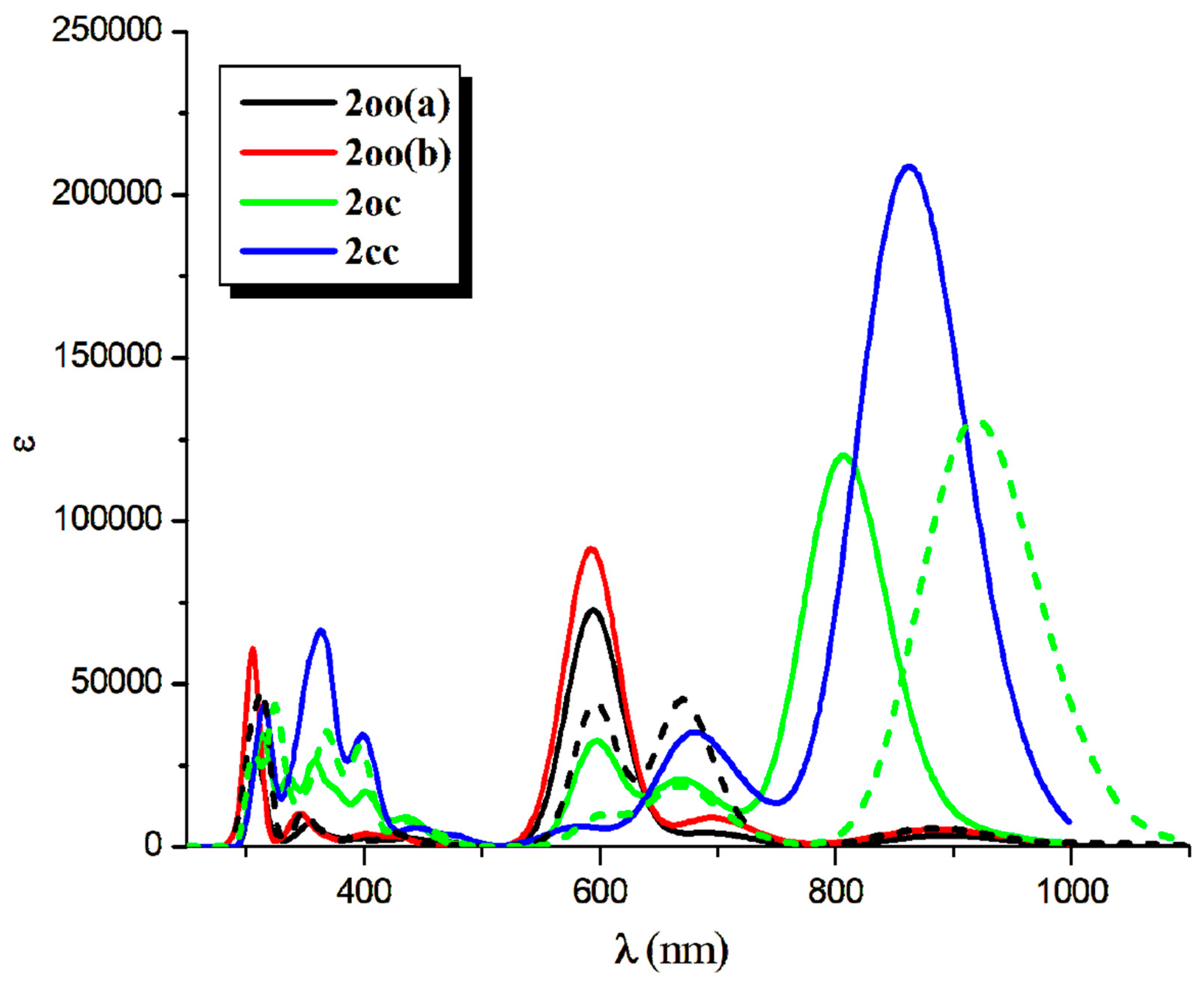

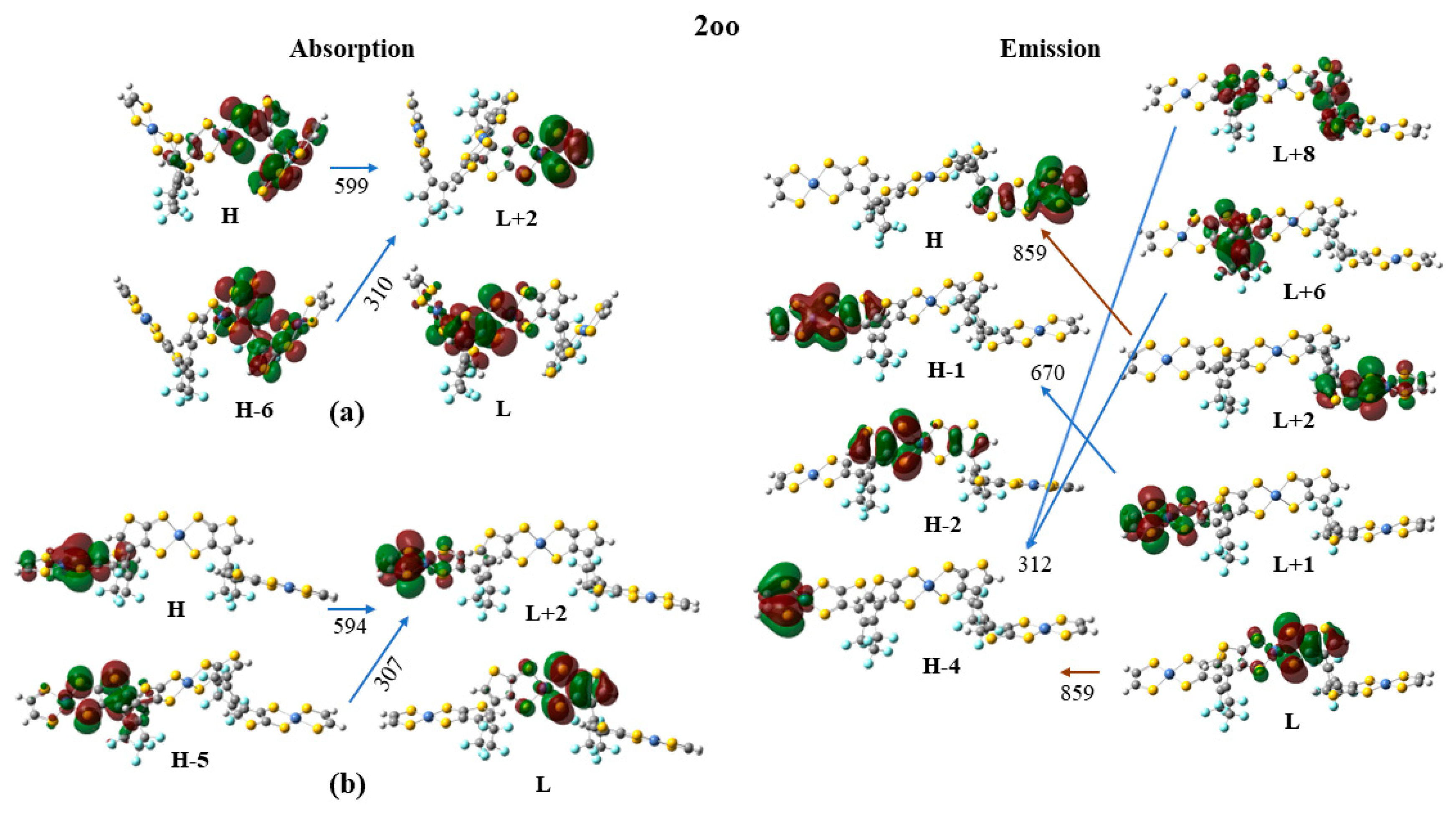

B. Derivatives Having NiBDT and Naphthalene as Linkers

III.2 Two-photon Absorption

ΙΙΙ. 3 Excitation Energy Transfer

Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Acknowledgments

References

- Fihey, A., R. Russo, L. Cupellini, D. Jacquemin, and B. Mennucci. "Is Energy Transfer Limiting Multiphotochromism? Answers from Ab Initio Quantifications." Physical Chemistry Chemical Physics 2017, 19, 2044-52. [CrossRef]

- Galanti, A., J. Santoro, R. Mannancherry, Q. Duez, V. Diez-Cabanes, M. Valasek, J. De Winter, J. Cornil, P. Gerbaux, M. Mayor, and P. Samori. "A New Class of Rigid Multi(Azobenzene) Switches Featuring Electronic Decoupling: Unravelling the Isomerization in Individual Photochromes." Journal of the American Chemical Society 2019, 141, 9273-83. [CrossRef]

- Hsu, C. P. "The Electronic Couplings in Electron Transfer and Excitation Energy Transfer." Accounts of Chemical Research 2009, 42, 509-18. [CrossRef]

- Nakamura, Y., N. Aratani, and A. Osuka. "Cyclic Porphyrin Arrays as Artificial Photosynthetic Antenna: Synthesis and Excitation Energy Transfer." Chemical Society Reviews 2007, 36, 831-45. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L. Y., R. A. Friesner, and R. B. Murphy. "Ab Initio Quantum Chemical Calculation of Electron Transfer Matrix Elements for Large Molecules." Journal of Chemical Physics 1997, 107, 450-59. [CrossRef]

- Headgordon, M., A. M. Grana, D. Maurice, and C. A. White. "Analysis of Electronic-Transitions as the Difference of Electron-Attachment and Detachment Densities." Journal of Physical Chemistry 1995, 99, 14261-70. [CrossRef]

- You, Z. Q., C. P. Hsu, and G. R. Fleming. "Triplet-Triplet Energy-Transfer Coupling: Theory and Calculation." Journal of Chemical Physics 2006, 124. [CrossRef]

- Iozzi, M. F., B. Mennucci, J. Tomasi, and R. Cammi. "Excitation Energy Transfer (Eet) between Molecules in Condensed Matter: A Novel Application of the Polarizable Continuum Model (Pcm)." Journal of Chemical Physics 2004, 120, 7029-40. [CrossRef]

- Scholes, G. D. "Long-Range Resonance Energy Transfer in Molecular Systems." Annual Review of Physical Chemistry 2003, 54, 57-87. [CrossRef]

- Kaieda, T., S. Kobatake, H. Miyasaka, M. Murakami, N. Iwai, Y. Nagata, A. Itaya, and M. Irie. "Efficient Photocyclization of Dithienylethene Dimer, Trimer, and Tetramer: Quantum Yield and Reaction Dynamics." Journal of the American Chemical Society 2002, 124, 2015-24.

- Chen, H. C., Z. Q. You, and C. P. Hsu. "The Mediated Excitation Energy Transfer: Effects of Bridge Polarizability." Journal of Chemical Physics 2008, 129. [CrossRef]

- Scholes, G. D., K. P. Ghiggino, A. M. Oliver, and M. N. Paddonrow. "Through-Space and through-Bond Effects on Exciton Interactions in Rigidly Linked Dinaphthyl Molecules." Journal of the American Chemical Society 1993, 115, 4345-49. [CrossRef]

- Oevering, H., M. N. Paddonrow, M. Heppener, A. M. Oliver, E. Cotsaris, J. W. Verhoeven, and N. S. Hush. "Long-Range Photoinduced through-Bond Electron-Transfer and Radiative Recombination Via Rigid Nonconjugated Bridges - Distance and Solvent Dependence." Journal of the American Chemical Society 1987, 109, 3258-69. [CrossRef]

- Pettersson, K., A. Kyrychenko, E. Ronnow, T. Ljungdahl, J. Martensson, and B. Albinsson. "Singlet Energy Transfer in Porphyrin-Based Donor-Bridge-Acceptor Systems: Interaction between Bridge Length and Bridge Energy." Journal of Physical Chemistry A 2006, 110, 310-18. [CrossRef]

- Cho, H. S., D. H. Jeong, M. C. Yoon, Y. H. Kim, Y. R. Kim, D. Kim, S. C. Jeoung, S. K. Kim, N. Aratani, H. Shinmori, and A. Osuka. "Excited-State Energy Transfer Processes in Phenylene- and Biphenylene-Linked and Directly-Linked Zinc(Ii) and Free-Base Hybrid Diporphyrins." Journal of Physical Chemistry A 2001, 105, 4200-10. [CrossRef]

- Smith, T. A., N. Lokan, N. Cabral, S. R. Davies, M. N. Paddon-Row, and K. P. Ghiggino. "Photophysics of Novel Donor-{Saturated Rigid Hydrocarbon Bridge}-Acceptor Systems Exhibiting Efficient Excitation Energy Transfer." Journal of Photochemistry and Photobiology a-Chemistry 2002, 149, 55-69.

- Kroon, J., A. M. Oliver, M. N. Paddonrow, and J. W. Verhoeven. "Observation of a Remarkable Dependence of the Rate of Singlet Singlet Energy-Transfer on the Configuration of the Hydrocarbon Bridge in Bichromophoric Systems." Journal of the American Chemical Society 1990, 112, 4868-73. [CrossRef]

- El-ghayoury, A., A. Harriman, A. Khatyr, and R. Ziessel. "Intramolecular Triplet Energy Transfer in Metal Polypyridine Complexes Bearing Ethynylated Aromatic Groups." Journal of Physical Chemistry A 2000, 104, 1512-23. [CrossRef]

- McConnell, H. M. "Intramolecular Charge Transfer in Aromatic Free Radicals." Journal of Chemical Physics 1961, 35, 508-15. [CrossRef]

- Kudernac, T., S. J. van der Molen, B. J. van Wees, and B. L. Feringa. "Uni- and Bi-Directional Light-Induced Switching of Diarylethenes on Gold Nanoparticles." Chemical Communications 2006, 34, 3597-99.

- Chen, J. X., J. Y. Wang, J. R. He, and X. F. Peng. "Photochromic Properties of Ruthenium Complexes with Dithienylethene-Ethynylthiophene." Dyes and Pigments 2021, 184.

- Chergui, M. "Ultrafast Molecular Photophysics in the Deep-Ultraviolet." Journal of Chemical Physics 2019, 150. [CrossRef]

- Munoz-Losa, A., C. Curutchet, B. P. Krueger, L. R. Hartsell, and B. Mennucci. "Fretting About Fret: Failure of the Ideal Dipole Approximation." Biophysical Journal 2009, 96, 4779-88. [CrossRef]

- Beljonne, D., C. Curutchet, G. D. Scholes, and R. J. Silbey. "Beyond Forster Resonance Energy Transfer in Biological and Nanoscale Systems." Journal of Physical Chemistry B 2009, 113, 6583-99. [CrossRef]

- Kenny, E. P., and I. Kassal. "Benchmarking Calculations of Excitonic Couplings between Bacteriochlorophylls." Journal of Physical Chemistry B 2016, 120, 25-32. [CrossRef]

- Sauer, K., R. J. Cogdell, S. M. Prince, A. Freer, N. W. Isaacs, and H. Scheer. "Structure-Based Calculations of the Optical Spectra of the Lh2 Bacteriochlorophyll-Protein Complex from Rhodopseudomonas Acidophila." Photochemistry and Photobiology 1996, 64, 564-76. [CrossRef]

- Krueger, B. P., G. D. Scholes, and G. R. Fleming. "Calculation of Couplings and Energy-Transfer Pathways between the Pigments of Lh2 by the Ab Initio Transition Density Cube Method." Journal of Physical Chemistry B 1998, 102, 5378-86.

- Kistler, K. A., F. C. Spano, and S. Matsika. "A Benchmark of Excitonic Couplings Derived from Atomic Transition Charges." Journal of Physical Chemistry B 2013, 117, 2032-44. [CrossRef]

- Scholes, G. D., and K. P. Ghiggino. "Electronic Interactions and Interchromophore Excitation Transfer." Journal of Physical Chemistry 1994, 98, 4580-90. [CrossRef]

- Munoz-Losa, A., C. Curutchet, B. P. Krueger, L. R. Hartsell, and B. Mennucci. "Fretting About Fret: Failure of the Ideal Dipole Approximation." Biophysical Journal 2009, 96, 4779-88. [CrossRef]

- Moerner, W. E. "Viewpoint: Single Molecules at 31: What's Next?" Nano Lett 2020, 20, 8427-29.

- Yang, Mino, and Graham R. Fleming. "Third-Order Nonlinear Optical Response of Energy Transfer Systems." The Journal of Chemical Physics 1999, 111, 27-39. [CrossRef]

- Coe, Benjamin J. "Molecular Materials Possessing Switchable Quadratic Nonlinear Optical Properties." Chemistry – A European Journal 1999, 5, 2464-71. [CrossRef]

- Castet, Frédéric, Vincent Rodriguez, Jean-Luc Pozzo, Laurent Ducasse, Aurélie Plaquet, and Benoît Champagne. "Design and Characterization of Molecular Nonlinear Optical Switches." Accounts of Chemical Research 2013, 46, 2656-65. [CrossRef]

- Beaujean, Pierre, Lionel Sanguinet, Vincent Rodriguez, Frédéric Castet, and Benoît Champagne. "Multi-State Second-Order Nonlinear Optical Switches Incorporating One to Three Benzazolo-Oxazolidine Units: A Quantum Chemistry Investigation." Molecules 2022, 27, 2770.

- Zhang, J. J., Q. Zou, and H. Tian. "Photochromic Materials: More Than Meets the Eye." Advanced Materials 2013, 25, 378-99. [CrossRef]

- Boixel, J., A. Colombo, F. Fagnani, P. Matozzo, and C. Dragonetti. "Intriguing Second-Order Nlo Switches Based on New Dte Compounds." European Journal of Inorganic Chemistry 2022, 2022. [CrossRef]

- Buckingham, A.D. "Permanent and Induced Molecular Moments and Long-Range Intermolecular Forces." In Advances in Chemical Physics 1967, 107-42.

- Cohen, H. D., and C. C. Roothaan. "Electric Dipole Polarizability of Atoms by Hartree-Fock Method .I. Theory for Closed-Shell Systems." Journal of Chemical Physics 1965, 43, S034-+.

- Romberg, W. "Vereinfachte Numerische Intergration." Kgl. Norske Vid. Selsk. Forsk 1955, 28, 30-36.

- Rutishauser, H. Ausdehnung Des Rombergschen Prinzips." Num. Math 1963, 5, 48-54. [CrossRef]

- Davis, P. J., and P. Rabinowitz. Numerical Intergration. London: Blaisdell, 1967.

- Takamuku, Shota, and Masayoshi Nakano. "Theoretical Study on Second Hyperpolarizabilities of Intramolecular Pancake-Bonded Diradicaloids with Helical Scaffolds." ACS Omega 2019, 4, 2741-49. [CrossRef]

- Frisch, M. J., G. W. Trucks, H. B. Schlegel, G. E. Scuseria, M. A. Robb, J. R. Cheeseman, G. Scalmani, V. Barone, G. A. Petersson, H. Nakatsuji, X. Li, M. Caricato, A. V. Marenich, J. Bloino, B. G. Janesko, R. Gomperts, B. Mennucci, H. P. Hratchian, J. V. Ortiz, A. F. Izmaylov, J. L. Sonnenberg, Williams, F. Ding, F. Lipparini, F. Egidi, J. Goings, B. Peng, A. Petrone, T. Henderson, D. Ranasinghe, V. G. Zakrzewski, J. Gao, N. Rega, G. Zheng, W. Liang, M. Hada, M. Ehara, K. Toyota, R. Fukuda, J. Hasegawa, M. Ishida, T. Nakajima, Y. Honda, O. Kitao, H. Nakai, T. Vreven, K. Throssell, J. A. Montgomery Jr., J. E. Peralta, F. Ogliaro, M. J. Bearpark, J. J. Heyd, E. N. Brothers, K. N. Kudin, V. N. Staroverov, T. A. Keith, R. Kobayashi, J. Normand, K. Raghavachari, A. P. Rendell, J. C. Burant, S. S. Iyengar, J. Tomasi, M. Cossi, J. M. Millam, M. Klene, C. Adamo, R. Cammi, J. W. Ochterski, R. L. Martin, K. Morokuma, O. Farkas, J. B. Foresman, and D. J. Fox. Gaussian 16 Rev. B.01,Gaussian, Inc., Wallingford CT, 2016.

- Becke, A. D. "A New Mixing of Hartree-Fock and Local Density-Functional Theories." Journal of Chemical Physics 1993, 98, 1372-77. [CrossRef]

- Serrano-Andres, L., A. Avramopoulos, J. Li, P. Labeguerie, D. Begue, V. Kello, and M. G. Papadopoulos. "Linear and Nonlinear Optical Properties of a Series of Ni-Dithiolene Derivatives." Journal of Chemical Physics 2009, 131, 134312. [CrossRef]

- Avramopoulos, A., H. Reis, G. A. Mousdis, and M. G. Papadopoulos. "Ni Dithiolenes - a Theoretical Study on Structure-Property Relationships." European Journal of Inorganic Chemistry 2013, 4839-50. [CrossRef]

- Avramopoulos, A., H. Reis, N. Otero, P. Karamanis, C. Pouchan, and M. G. Papadopoulos. "A Series of Novel Derivatives with Giant Second Hyperpolarizabilities, Based on Radiaannulenes, Tetrathiafulvalene, Nickel Dithiolene, and Their Lithiated Analogues." Journal of Physical Chemistry C 2016, 120, 9419-35. [CrossRef]

- Avramopoulos, Aggelos, Robert Zaleśny, Heribert Reis, and Manthos G. Papadopoulos. "A Computational Strategy for the Design of Photochromic Derivatives Based on Diarylethene and Nickel Dithiolene with Large Contrast in Nonlinear Optical Properties." The Journal of Physical Chemistry C 2020, 124, 4221-41. [CrossRef]

- Sutradhar, T., and A. Misra. "The Role of Pi-Linkers and Electron Acceptors in Tuning the Nonlinear Optical Properties of Bodipy-Based Zwitterionic Molecules." Rsc Advances 2020, 10, 40300-09. [CrossRef]

- Cao, L. L., and U. Ryde. "Influence of the Protein and Dft Method on the Broken-Symmetry and Spin States in Nitrogenase." International Journal of Quantum Chemistry 2018, 118. [CrossRef]

- Garcia-Borras, M., M. Sola, J. M. Luis, and B. Kirtman. "Electronic and Vibrational Nonlinear Optical Properties of Five Representative Electrides." Journal of Chemical Theory and Computation 2012, 8, 2688-97. [CrossRef]

- Areephong, Jetsuda, Johannes H. Hurenkamp, Maaike T. W. Milder, Auke Meetsma, Jennifer L. Herek, Wesley R. Browne, and Ben L. Feringa. "Photoswitchable Sexithiophene-Based Molecular Wires." Organic Letters 2009, 11, 721-24. [CrossRef]

- Jacquemin, Denis, Antoine Femenias, Henry Chermette, Ilaria Ciofini, Carlo Adamo, Jean-Marie André, and Eric A. Perpète. "Assessment of Several Hybrid Dft Functionals for the Evaluation of Bond Length Alternation of Increasingly Long Oligomers." The Journal of Physical Chemistry A 2006, 110, 5952-59. [CrossRef]

- Yanai, T., D. P. Tew, and N. C. Handy. "A New Hybrid Exchange-Correlation Functional Using the Coulomb-Attenuating Method (Cam-B3lyp)." Chemical Physics Letters 2004, 393, 51-57. [CrossRef]

- Francl, M.M., W.J. Pietro, W.J. Hehre, M.S Gordon, DeFees D.J., and J.A Pople. "Self-Consistent Molecular Orbital Methods. Xxiii. A Polarization-Type Basis Set for Second-Row Elements " Journal of Chemical Physics 1982, 77, 3654-65. [CrossRef]

- Hariharan, P.C., and J.A. Pople. "The Influence of Polarization Functions on Molecular Orbital Hydrogenation Energies." Theoretica Chimica Acta 1973, 28, 213-22. [CrossRef]

- Dunning, T. H. "Gaussian-Basis Sets for Use in Correlated Molecular Calculations .1. The Atoms Boron through Neon and Hydrogen." Journal of Chemical Physics 1989, 90, 1007-23. [CrossRef]

- Woon, D. E., and T. H. Dunning. "Gaussian-Basis Sets for Use in Correlated Molecular Calculations .3. The Atoms Aluminum through Argon." Journal of Chemical Physics 1993, 98, 1358-71. [CrossRef]

- Dolg, M., U. Wedig, H. Stoll, and H. Preuss. "Energy-Adjusted Abinitio Pseudopotentials for the 1st-Row Transition-Elements." Journal of Chemical Physics 1987, 86, 866-72.

- Bachler, V., G. Olbrich, F. Neese, and K. Wieghardt. "Theoretical Evidence for the Singlet Diradical Character of Square Planar Nickel Complexes Containing Two Omicron-Semiquinonato Type Ligands." Inorganic Chemistry 2002, 41, 4179-93. [CrossRef]

- Tzeli, Demeter, Giannoula Theodorakopoulos, Ioannis D. Petsalakis, Dariush Ajami, and Julius Rebek, Jr. "Conformations and Fluorescence of Encapsulated Stilbene." Journal of the American Chemical Society 2012, 134, 4346-54. [CrossRef]

- Tzeliou, Christina Eleftheria, and Demeter Tzeli. "3-Input and Molecular Logic Gate with Enhanced Fluorescence Output: The Key Atom for the Accurate Prediction of the Spectra." Journal of Chemical Information and Modeling 2022, 62, 6436-48. [CrossRef]

- Peach, Michael J. G., Peter Benfield, Trygve Helgaker, and David J. Tozer. "Excitation Energies in Density Functional Theory: An Evaluation and a Diagnostic Test." The Journal of Chemical Physics 2008, 128, 044118. [CrossRef]

- Dreuw, A., and M. Head-Gordon. "Single-Reference Ab Initio Methods for the Calculation of Excited States of Large Molecules." Chemical Reviews 2005, 105, 4009-37. [CrossRef]

- Casida, M. E., and M. Huix-Rotllant. "Progress in Time-Dependent Density-Functional Theory." Annual Review of Physical Chemistry, 2012, 63, 287-323. [CrossRef]

- Jacquemin, D., E. A. Perpete, G. E. Scuseria, I. Ciofini, and C. Adamo. "Td-Dft Performance for the Visible Absorption Spectra of Organic Dyes: Conventional Versus Long-Range Hybrids." Journal of Chemical Theory and Computation 2008, 4, 123-35. [CrossRef]

- Jacquemin, D., A. Planchat, C. Adamo, and B. Mennucci. "Td-Dft Assessment of Functionals for Optical 0-0 Transitions in Solvated Dyes." Journal of Chemical Theory and Computation 2012, 8, 2359-72. [CrossRef]

- Mahr, H. "Two-Photon Absorption Spectroscopy." In Quantum Electronics, edited by H. Rabin and C. L. Tang, 494. New York: Academic Press, 1975.

- R L Swofford, and, and A C Albrecht. "Nonlinear Spectroscopy." Annual Review of Physical Chemistry 1978, 29, 421-40.

- Bloembergen, Nicolaas. Nonlinear Optics, Nonlinear Optics, 1996.

- Olsen, Jeppe, and Poul Jo/rgensen. "Linear and Nonlinear Response Functions for an Exact State and for an Mcscf State." The Journal of Chemical Physics 1985, 82, 3235-64. [CrossRef]

- Monson, P. R., and W. M. McClain. "Polarization Dependence of the Two-Photon Absorption of Tumbling Molecules with Application to Liquid 1-Chloronaphthalene and Benzene." The Journal of Chemical Physics 1970, 53, 29-37. [CrossRef]

- Beerepoot, Maarten T. P., Daniel H. Friese, Nanna H. List, Jacob Kongsted, and Kenneth Ruud. "Benchmarking Two-Photon Absorption Cross Sections: Performance of Cc2 and Cam-B3lyp." Physical Chemistry Chemical Physics 2015, 17, 19306-14. [CrossRef]

- Schmidt, Michael W., Kim K. Baldridge, Jerry A. Boatz, Steven T. Elbert, Mark S. Gordon, Jan H. Jensen, Shiro Koseki, Nikita Matsunaga, Kiet A. Nguyen, Shujun Su, Theresa L. Windus, Michel Dupuis, and John A. Montgomery Jr. "General Atomic and Molecular Electronic Structure System." Journal of Computational Chemistry 1993, 14, 1347-63. [CrossRef]

- Zahariev, F., and M. S. Gordon. "Nonlinear Response Time-Dependent Density Functional Theory Combined with the Effective Fragment Potential Method." J Chem Phys 2014, 140, 18A523. [CrossRef]

- Zaleśny, Robert, N. Arul Murugan, Guangjun Tian, Miroslav Medved’, and Hans Ågren. "First-Principles Simulations of One- and Two-Photon Absorption Band Shapes of the Bis(Bf2) Core Complex." The Journal of Physical Chemistry B 2016, 120, 2323-32. [CrossRef]

- Beerepoot, Maarten T. P., Md Mehboob Alam, Joanna Bednarska, Wojciech Bartkowiak, Kenneth Ruud, and Robert Zaleśny. "Benchmarking the Performance of Exchange-Correlation Functionals for Predicting Two-Photon Absorption Strengths." Journal of Chemical Theory and Computation 2018, 14, 3677-85. [CrossRef]

- Choluj, M., M. M. Alam, M. T. P. Beerepoot, S. P. Sitkiewicz, E. Matito, K. Ruud, and R. Zalesny. "Choosing Bad Versus Worse: Predictions of Two-Photon-Absorption Strengths Based on Popular Density Functional Approximations." J Chem Theory Comput 2022, 18, 1046-60. [CrossRef]

- Iozzi, M. F., B. Mennucci, J. Tomasi, and R. Cammi. "Excitation Energy Transfer (Eet) between Molecules in Condensed Matter: A Novel Application of the Polarizable Continuum Model (Pcm)." J Chem Phys 2004, 120, 7029-40. [CrossRef]

- Blasiak, B., M. Maj, M. Cho, and R. W. Gora. "Distributed Multipolar Expansion Approach to Calculation of Excitation Energy Transfer Couplings." J Chem Theory Comput 2015, 11, 3259-66. [CrossRef]

- Förster, Th. "Zwischenmolekulare Energiewanderung Und Fluoreszenz." Annalen der Physik 1948, 437, 55-75. [CrossRef]

- Stone, A. J. "Distributed Multipole Analysis, or How to Describe a Molecular Charge Distribution." Chemical Physics Letters 1981, 83, 233-39. [CrossRef]

- Stone, Anthony. The Theory of Intermolecular Forces: Oxford University Press, 2013.

- Lu, Tian, and Feiwu Chen. "Multiwfn: A Multifunctional Wavefunction Analyzer." Journal of Computational Chemistry 2012, 33, 580-92. [CrossRef]

- Stone, Anthony J. "Distributed Multipole Analysis: Stability for Large Basis Sets." Journal of Chemical Theory and Computation 2005, 1, 1128-32. [CrossRef]

- Oliver, S., and C. Winter. "Metal Dithiolene Complexes for All-Optical Switching Devices." Advanced Materials 1992, 4, 119-21. [CrossRef]

- Matsuoka, R., R. Sakamoto, T. Kambe, K. Takada, T. Kusamoto, and H. Nishihara. "Ordered Alignment of a One-Dimensional Pi-Conjugated Nickel Bis(Dithiolene) Complex Polymer Produced Via Interfacial Reactions." Chemical Communications 2014, 50, 8137-39.

- Lei Zhang, Gilles H. Peslhebre, and Heidi M. Muchall. "A General Measure of Conjugation in Biphenyls and Their Radical Cations." Canadian Journal of Chemistry 2010, 88, 1175-85. [CrossRef]

- Serrano-Andres, L., A. Avramopoulos, J. Li, P. Labeguerie, D. Begue, V. Kello, and M. G. Papadopoulos. "Linear and Nonlinear Optical Properties of a Series of Ni-Dithiolene Derivatives." J Chem Phys 2009, 131, 134312. [CrossRef]

- Dobrowolski, Jan Cz, and Sławomir Ostrowski. "On the Homa Index of Some Acyclic and Conducting Systems." Rsc Advances 2015, 5, 9467-71. [CrossRef]

- Kauczor, Joanna, Patrick Norman, Ove Christiansen, and Sonia Coriani. "Communication: A Reduced-Space Algorithm for the Solution of the Complex Linear Response Equations Used in Coupled Cluster Damped Response Theory." The Journal of Chemical Physics 2013, 139, 211102. [CrossRef]

- Thanh Phuc, Nguyen, and Akihito Ishizaki. "Control of Excitation Energy Transfer in Condensed Phase Molecular Systems by Floquet Engineering." The Journal of Physical Chemistry Letters 2018, 9, 1243-48.

- Escudero, D., and K. Veys. "Anti-Kasha Fluorescence in Molecular Entities: Central Role of Electron-Vibrational Coupling." Accounts of Chemical Research 2022. [CrossRef]

- Veys, K., and D. Escudero. "Computational Protocol to Predict Anti-Kasha Emissions: The Case of Azulene Derivatives." Journal of Physical Chemistry A 2020, 124, 7228-37. [CrossRef]

- Escudero, D. "Revising Intramolecular Photoinduced Electron Transfer (Pet) from First-Principles." Accounts of Chemical Research 2016, 49, 1816-24. [CrossRef]

- Rohrs, M., and D. Escudero. "Multiple Anti-Kasha Emissions in Transition-Metal Complexes." Journal of Physical Chemistry Letters 2019, 10, 5798-804. [CrossRef]

| 1cc | 1oc | 1oo | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ΔE | f | <δ2PA> ×103 |

ΔE | f | <δ2PA> ×103 |

ΔE | f | <δ2PA> ×103 |

|

| S0→S1 | 2.162 | 2.3537 | <0.1 | 2.243 | 1.4665 | 7.0 | 2.820 | 2.5150 | <0.1 |

| S0→S2 | 2.344 | 0.0159 | 0.2 | 2.843 | 1.2518 | 113.3 | 3.543 | 0.0226 | 8.6 |

| S0→S3 | 2.885 | 0.6755 | 0.4 | 3.436 | 0.0660 | 1512.2 | 3.994 | 0.0236 | <0.1 |

| S0→S4 | 3.340 | 0.0008 | 6690.7 | 3.648 | 0.0164 | 2358.2 | 4.023 | 0.0380 | 126.0 |

| S0→S5 | 3.577 | 0.0002 | 3105.5 | 3.793 | 0.0868 | 19.5 | 4.156 | 0.0030 | 2023.3 |

| NO2 -1AB-NH2 | H-1AB-H | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AB | cc | co | oc | oo | cc | oc | oo |

| IHOMA | 0.827 | 0.806 | 0.807 | 0.778 | 0.843 | 0.812 | 0.790 |

| 1cc | 1oc | 1oo | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ΔE | f | <δ2PA> ×103 |

ΔE | f | <δ2PA> ×103 |

ΔE | f | <δ2PA> ×103 |

|

| S0→S1 | 2.169 | 2.1698 | <0.1 | 2.252 | 1.3319 | 3.2 | 2.819 | 2.4780 | <0.1 |

| S0→S2 | 2.344 | 0.0114 | 1.8 | 2.844 | 1.3222 | 94.1 | 3.544 | 0.0208 | 5.2 |

| S0→S3 | 2.878 | 0.7472 | 0.3 | 3.450 | 0.0534 | 1192.0 | 4.045 | 0.0252 | <0.1 |

| S0→S4 | 3.353 | 0.0002 | 5802.2 | 3.643 | 0.0144 | 2168.1 | 4.080 | 0.0337 | 431.2 |

| S0→S5 | 3.556 | 0.0002 | 2516.0 | 3.748 | 0.0822 | 25.3 | 4.162 | 0.0106 | 1657.9 |

| 1cc | 1oc | 1oo | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ΔE | f | <δ2PA> ×103 |

ΔE | f | <δ2PA> ×103 |

ΔE | f | <δ2PA> ×103 |

|

| S0→S1 | 2.161 | 2.4581 | <0.1 | 2.253 | 1.5232 | 2.8 | 2.817 | 2.5106 | <0.1 |

| S0→S2 | 2.353 | 0.0150 | 31.9 | 2.885 | 1.2299 | 41.8 | 3.540 | 0.0226 | 2.6 |

| S0→S3 | 2.935 | 0.5549 | 0.3 | 3.526 | 0.0218 | 1966.6 | 3.940 | 0.0263 | 1.0 |

| S0→S4 | 3.382 | 0.0005 | 9561.7 | 3.562 | 0.0402 | 1807.8 | 3.949 | 0.0974 | 13.5 |

| S0→S5 | 3.544 | 0.0002 | 1.6 | 3.905 | 0.0294 | 25.9 | 4.128 | 0.0018 | 1927.5 |

| 1cc | 1oc | 1oo | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ΔE | f | <δ2PA> ×103 |

ΔE | f | <δ2PA> ×103 |

ΔE | f | <δ2PA> ×103 |

|

| S0→S1 | 1.932 | 2.0938 | <0.1 | 1.984 | 1.1765 | 49.1 | 2.820 | 2.5449 | <0.1 |

| S0→S2 | 2.068 | 0.0024 | 39.1 | 2.691 | 1.4493 | 367.0 | 3.539 | 0.0248 | 20.3 |

| S0→S3 | 2.696 | 1.0551 | <0.1 | 3.229 | 0.1597 | 3058.4 | 3.840 | 0.0130 | 0.4 |

| S0→S4 | 3.089 | 0.0009 | 10167.0 | 3.374 | 0.1308 | 715.1 | 3.853 | 0.0056 | 20.2 |

| S0→S5 | 3.322 | 0.0006 | 4760.5 | 3.468 | 0.0753 | 9.2 | 3.912 | 0.0003 | <0.1 |

| 1cc | 1oca) | 1oo | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ΔE | f | <δ2PA> ×103 |

ΔE | f | <δ2PA> ×103 |

ΔE | f | <δ2PA> ×103 |

|

| S0→S1 | 1.951 | 1.7422 | 118.4 | 2.249 | 1.5157 | 8.3 | 2.817 | 2.5218 | 3.5 |

| S0→S2 | 2.243 | 0.6864 | 85.5 | 2.886 | 1.2587 | 9.6 | 3.538 | 0.0245 | 9.3 |

| S0→S3 | 2.704 | 0.3358 | 1286.2 | 3.528 | 0.0035 | 3251.3 | 3.799 | 0.0068 | 9.3 |

| S0→S4 | 3.002 | 0.3582 | 2916.7 | 3.542 | 0.0658 | 557.8 | 3.912 | 0.0002 | 0.2 |

| S0→S5 | 3.253 | 0.0042 | 1586.6 | 3.777 | 0.0015 | 0.6 | 3.951 | 0.0583 | 5.3 |

| 1oca | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| ΔE | f | <δ2PA> ×103 |

|

| S0→S1 | 1.972 | 1.2258 | 70.5 |

| S0→S2 | 2.650 | 1.3286 | 541.5 |

| S0→S3 | 3.195 | 0.2143 | 3036.5 |

| S0→S4 | 3.360 | 0.1164 | 743.6 |

| S0→S5 | 3.460 | 0.0732 | 11.5 |

| Dimer | VDA | Vc | Vxc |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1oca | 8.3 | 8.1 9,7b | 0.2 0.25b |

| 2oc | 10,3 | 9,7 | 0,6 |

| 4oc | 101.5 | 101.6 | -0.1 |

| 5oc | 113.0 | 111.3 | 1.7 |

| 6oc | 120.4 | 120.9 | -0.5 |

| 7oc | 32.3 | 30.9 | 1.4 |

| 8oc | 12.8 | 12.1 | 0.7 |

| Dimer | Dna | E/fb | Transition/(%) | Ana | E/fb | Transition/(%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1occ | D1 |

4.433/0.139 4.450/0.111d |

HOMO->LUMO/(100) | A7 |

4.233/0.04 4.320/0.01d |

HOMO-2->LUMO/21 HOMO-1->LUMO+4/19 HOMO->LUMO+4/27 |

| 2oc | D22 | 4,619/0,22 | HOMO-14->LUMO (50%) HOMO->LUMO+2 (12.5%) HOMO-5->LUMO+1 (14.5%) |

A55 | 4,607/0,04 | HOMO->LUMO+9(22%) HOMO-9->LUMO+4 (11%) HOMO-7->LUMO+3(5,8%) HOMO-1->LUMO+5(8%) |

| 4oc | D1 | 4.226/0.702 | HOMO->LUMO/(98) |

A4 A1 A2 |

4.176/0.124 2.628/0.458 3.892/0.121 |

HOMO->LUMO+1/67 HOMO->LUMO/95 HOMO-1->LUMO/54 HOMO-2->LUMO+1/32 |

| 5oc | D1 | 4.217/0.181 | HOMO->LUMO/(98) |

A4 A1 A2 A3 |

4.209/0.356 2.607/0.470 3.908/0.108 3.921/0.136 |

HOMO->LUMO+1/63 HOMO->LUMO/100 HOMO-2->LUMO/84 HOMO-1->LUMO/77 |

| 6oc | D1 | 4.217/0.702 | HOMO->LUMO/(98) |

A4 A1 A2 A3 |

4.210/0.356 2.607/0.689 3.909/0.108 3.921/0.136 |

HOMO->LUMO+1/63 HOMO->LUMO/100 HOMO-2->LUMO/84 HOMO-1->LUMO/77 |

| 7oc | D1 D2 D3 D4 |

2.482/0 3.147/0 3.627/0 4.231/0.174 |

HOMO->LUMO/(100) |

A6 A24 A42 A46 A50 |

1.345/0.37 2.650/0.28 3.770/0.15 4.040/0.06 4.160/0.06 |

HOMO->LUMO/92 HOMO->LUMO+1/84 HOMO-1->LUMO+1/79 HOMO-2->LUMO+1/84 HOMO-6->LUMO/29 HOMO-14->LUMO/25 HOMO-3->LUMO/8 |

| 8oc | D1 D2 D3 D4 |

2.456/0 3.140/0 3.620/0 4.205/0.173 |

HOMO->LUMO/(100) |

A6 A7 A24 A32 A40 A47 A50 |

1.383/0.51 2.607/0.02 2.600/0.215 3.109/0.04 3.730/0.141 4.095/0.06 4.136/0.01 |

HOMO->LUMO/92 HOMO-1->LUMO/79 HOMO->LUMO+1/87 HOMO-2->LUMO/44 HOMO-1->LUMO+1/79 HOMO-2->LUMO+1/40 HOMO->LUMO+2/37 |

| l+l’ Bridge |

0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | Analyt. Coulomba |

Analyt. EETa. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Naphthalene | 82.3 | 137.1 | 143.6 | 127.4 | 117.8 | 111.3 | 112.9 |

| NiBDT | 4.8 | 8.1 | 13.7 | 12.1 | 15.3 | 12.1 | 12.9 |

| Struct | ΔΕ | λmax | f | Excitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Absorption | ||||

| 2oo(a) | 1.805 | 686.9 | 0.0115 | 0.35|H-2 L+1> − 0.29|H L+2> + 0.28|H-1 L+1> + 0.26|H-2 L> |

| 2.071 | 598.7 | 0.1141 | 0.20|H L+2> + 0.16|H-1 L+2> − 0.21|H-10 L+5> | |

| 4.006 | 309.5 | 0.1252 | 0.19|H-6 L+2> − 0.13|H-1 L+6> | |

| 2oo(b) | 1.791 | 692.2 | 0.0447 | 0.56|H-1 L+1> − 0.36|H L+2> |

| 2.088 | 593.7 | 0.4031 | 0.42|H L+2> + 0.23|H-1 L+1> − 0.18|H-2 L> | |

| 4.044 | 306.6 | 0.2014 | 0.18|H-2 L+8> + 0.20|H-5 L+2> − 0.22|H-35 L> − 0.20|H-19 L+3> | |

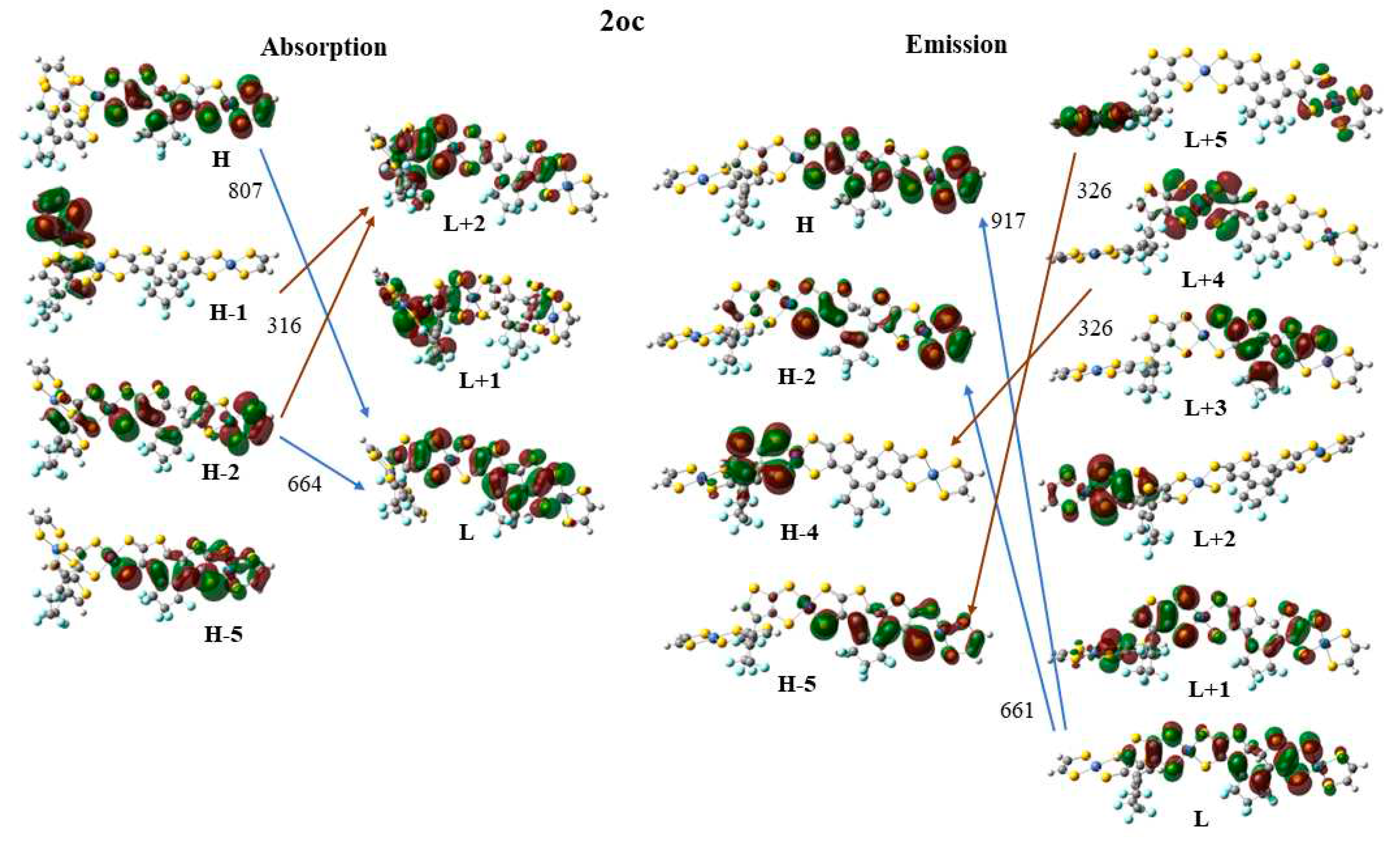

| 2oc | 1.537 | 806.9 | 0.7112 | 0.58|H L> − 0.23|H-5 L> |

| 1.868 | 663.7 | 0.0926 | 0.38|H-2 L> − 0.27|H-5 L> | |

| 3.925 | 315.9 | 0.0983 | 0.39|H-17 L> + 0.22|H-26 L> +0.31|H-26 L+2> | |

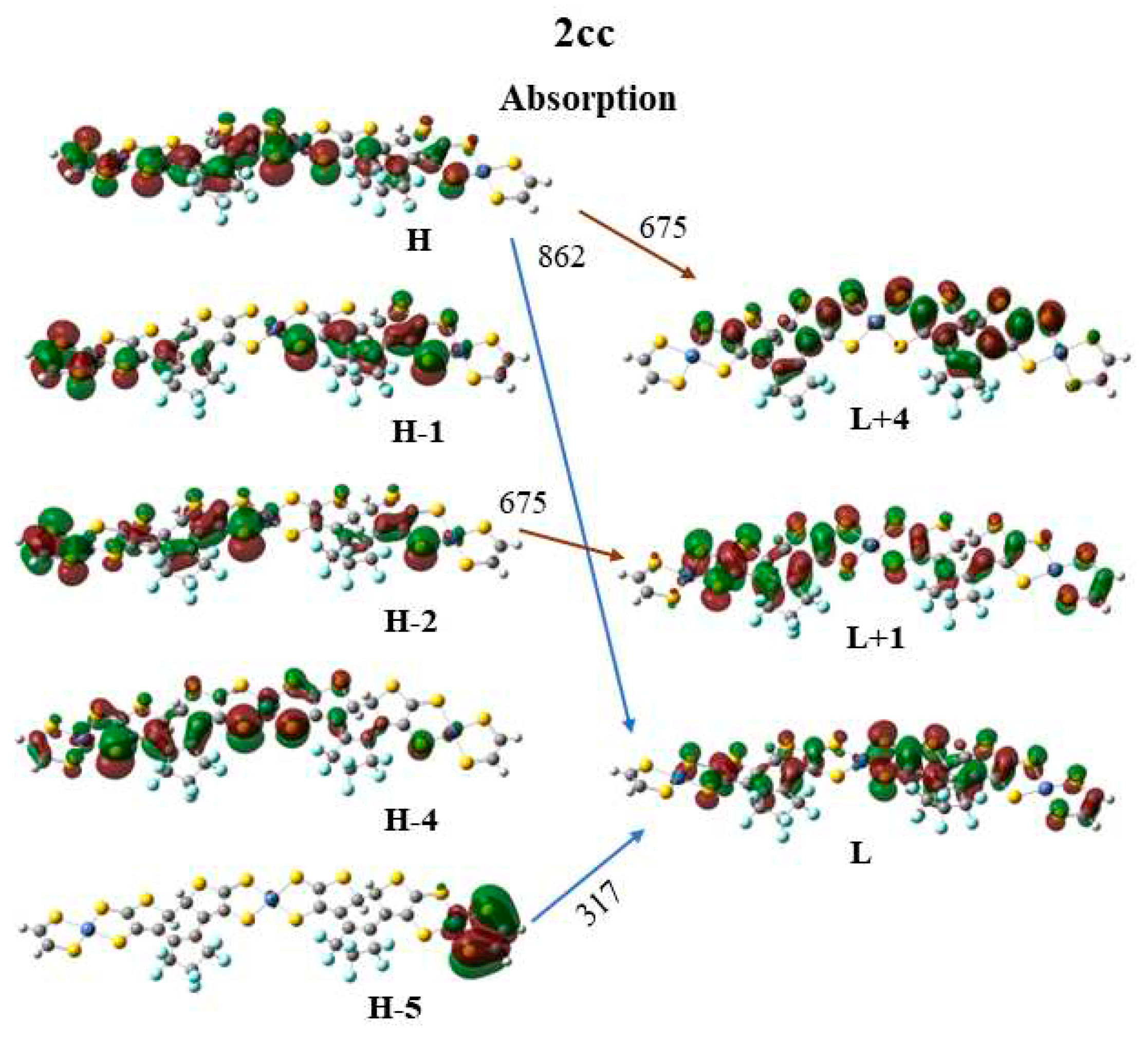

| 2cc | 1.438 | 862.3 | 1.3931 | 0.51|H L> + 0.30|H-1 L+1> |

| 1.837 | 675.1 | 0.1866 | 0.23|H L+4> + 0.20|H-4 L> − 0.23|H-2 L+1> + 0.18|H-1 L> | |

| 3.107 | 399.0 | 0.1077 | 0.28|H-1 L+1> + 0.21|H L+4> − 0.21|H-4 L+1>− 0.18|H-4 L> | |

| 3.369 | 368.0 | 0.1701 | 0.29|H-17 L> − 0.16|H-18 L> + 0.15|H-8 L> | |

| 3.519 | 352.4 | 0.1073 | 0.27|H-19 L+1> + 0.19|H-19 L> − 0.18|H-9 L+1>− 0.11|H-2 L+1> | |

| 3.917 | 316.5 | 0.1402 | 0.27|H-16 L+1> + 0.21|H-16 L>− 0.19|H-13 L>+ 0.26|H-5 L> | |

| Emission | ||||

| 2oo | 1.444 | 858.7 | 0.0170 | 0.65|H-4 L> − 0.15|H-2 L> |

| 1.851 | 669.7 | 0.1938 | 0.47|H-1 L+2> − 0.51|H-1 L+1> − 0.39|H-14 L+2>+ 0.27|H-12 L+2> + 0.21|H-14 L+1> | |

| 2.074 | 597.8 | 0.1588 | 0.52|H L+2> + 0.40|H-9 L+4> | |

| 3.966 | 312.6 | 0.2401 | 0.33|H-2 L+8> + 0.14|H-2 L+6> − 0.36|H-34 L> | |

| 2oc | 1.353 | 916.5 | 0.7071 | 0.57|H L> − 0.24|H-4 L> |

| 1.874 | 661.6 | 0.0774 | 0.32|H-5 L> + 0.29|H L+1> − 0.43|H-2 L>− 0.25|H H-19> | |

| 3.806 | 325.8 | 0.0748 | 0.31|H-15 L> + 0.23|H-4 L+4> − 0.25|H-5 L+5> | |

| 2oo | 2oc | 2cc | 2oo | 2oc | 2oo | 2oc |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| S0 → Si a | Si→ S0 b | S0 → Si c | ||||

| 1.81 (1.79)d | 1.54 | 1.44 | 1.44 | 1.35 | 1.67 | 1.40 |

| 2.07 (2.09)d | 1.87 | 1.84 | 1.85 | 1.86 | 1.98 | 1.87 |

| 4.01 (4.04)d | 3.92 | 3.11 | 3.97 | 3.81 | 4.00 | 3.88 |

| 3.37 | ||||||

| 3.52 | ||||||

| 3.92 | ||||||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).