Submitted:

06 July 2023

Posted:

07 July 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

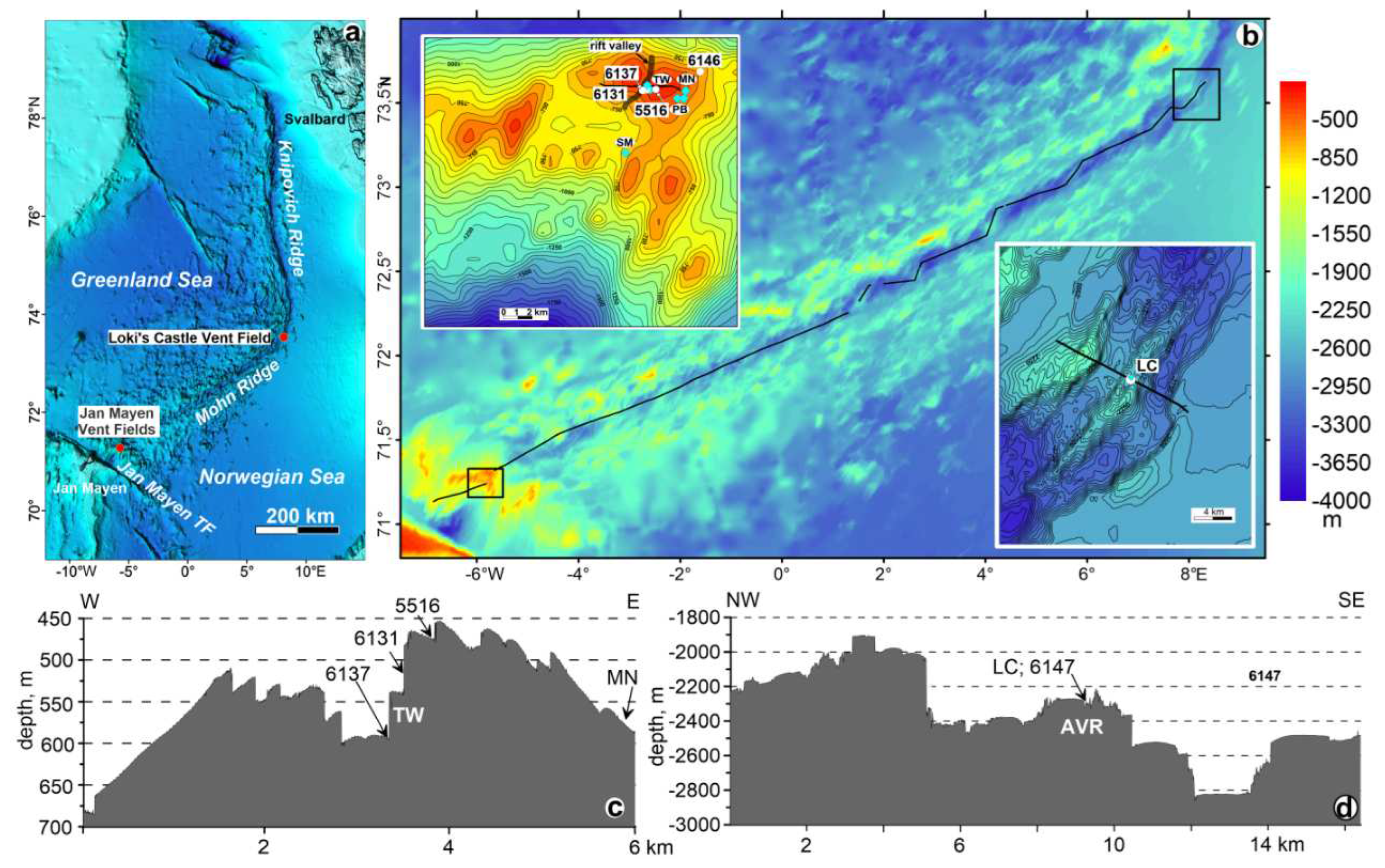

2. Geological Setting

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Study area

3.1.1. Jan Mayen AVR at 71°18' N and related hydrothermal systems

3.1.2. The AVR at 73°30' N and 8° E and related hydrothermal system

3.2. Field Observations and Sample Collection

3.3. Petrography and Mineralogy

3.4. XRF Analysis

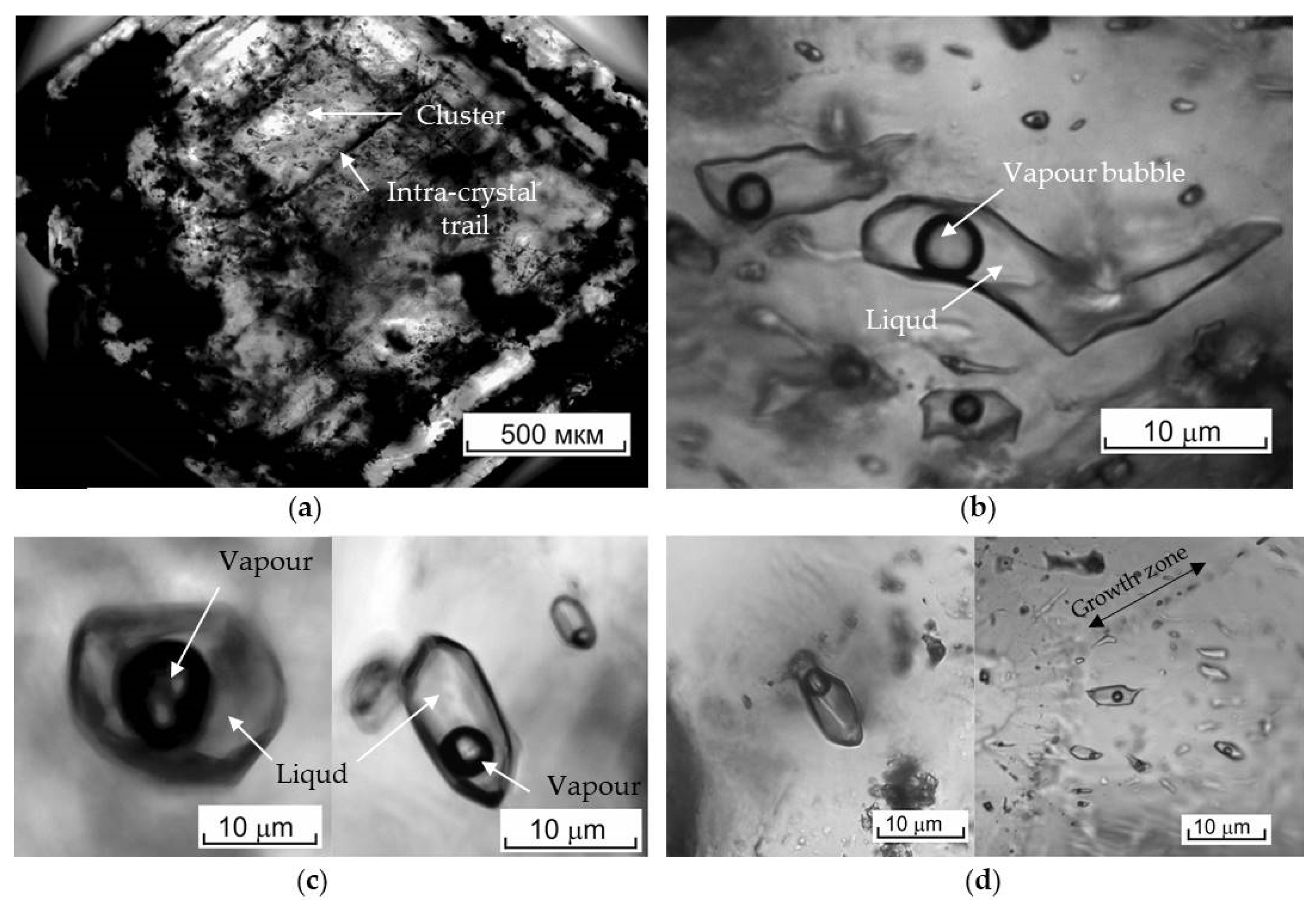

3.5. Sample Preparation and Fluid Inclusions Petrography

3.6. Fluid Inclusions Microthermonetry

4. Results

4.1. Temperature and Salinity of Ambient Seawater

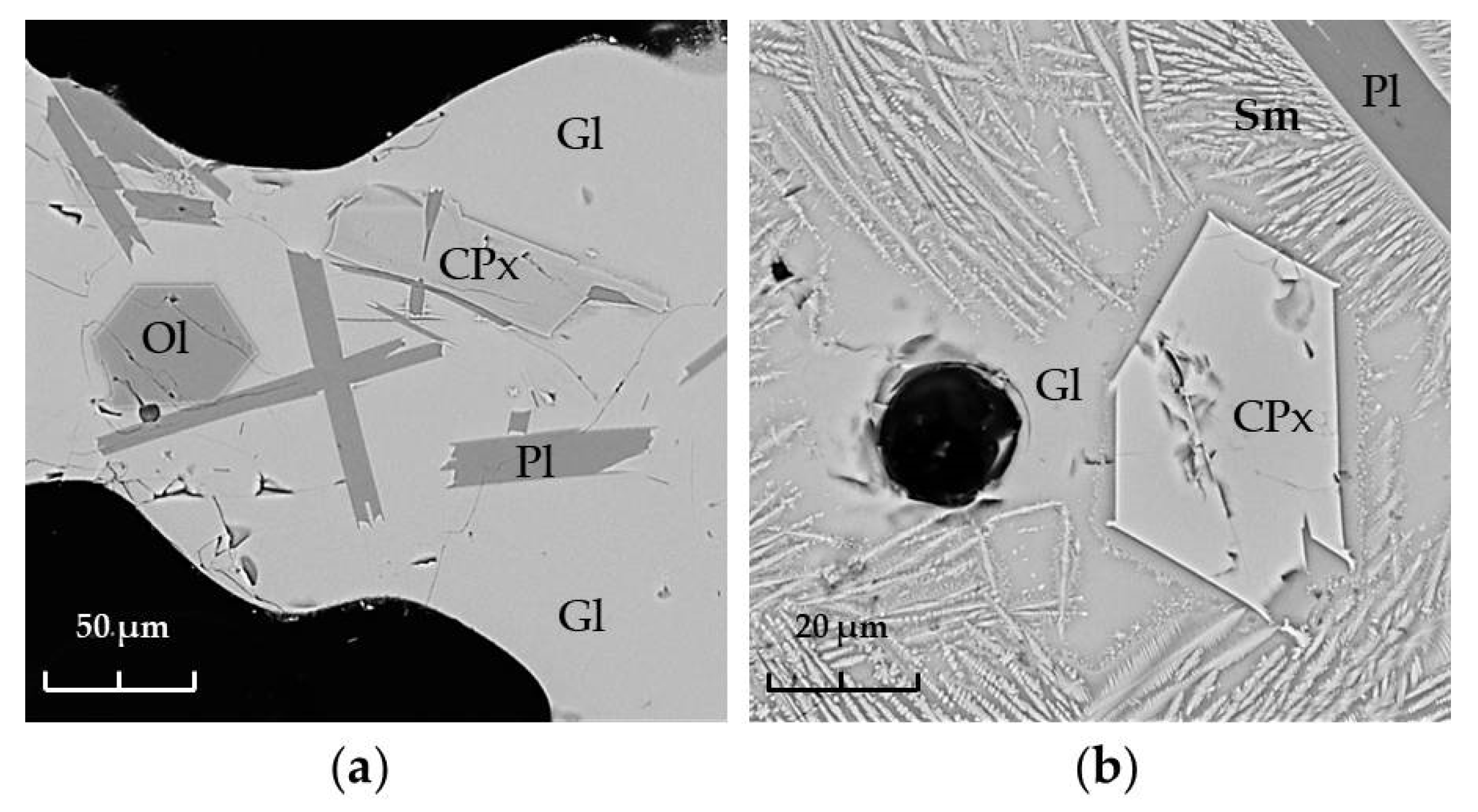

4.2. Petrography and Lithology

4.3. Mineralogy

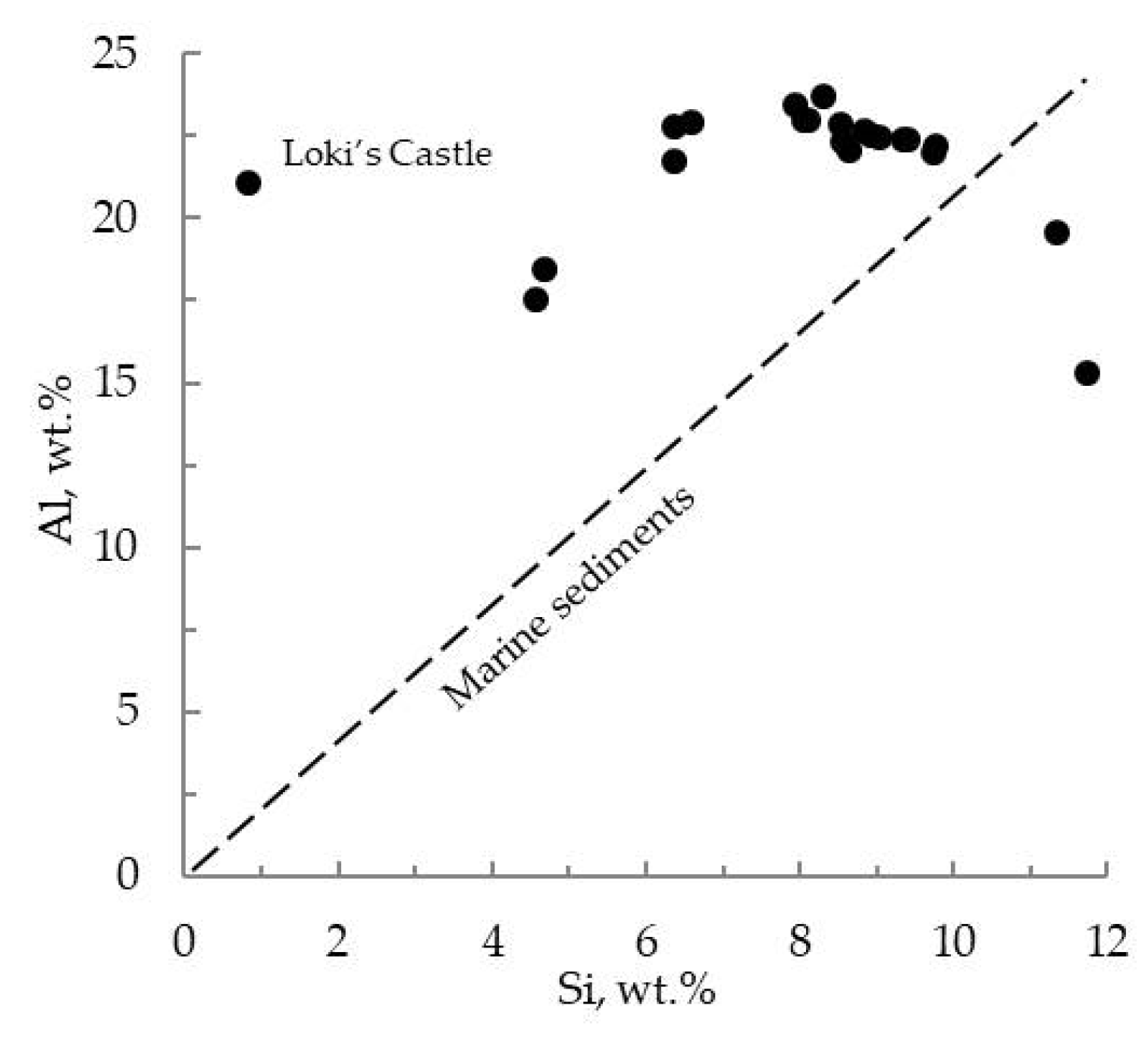

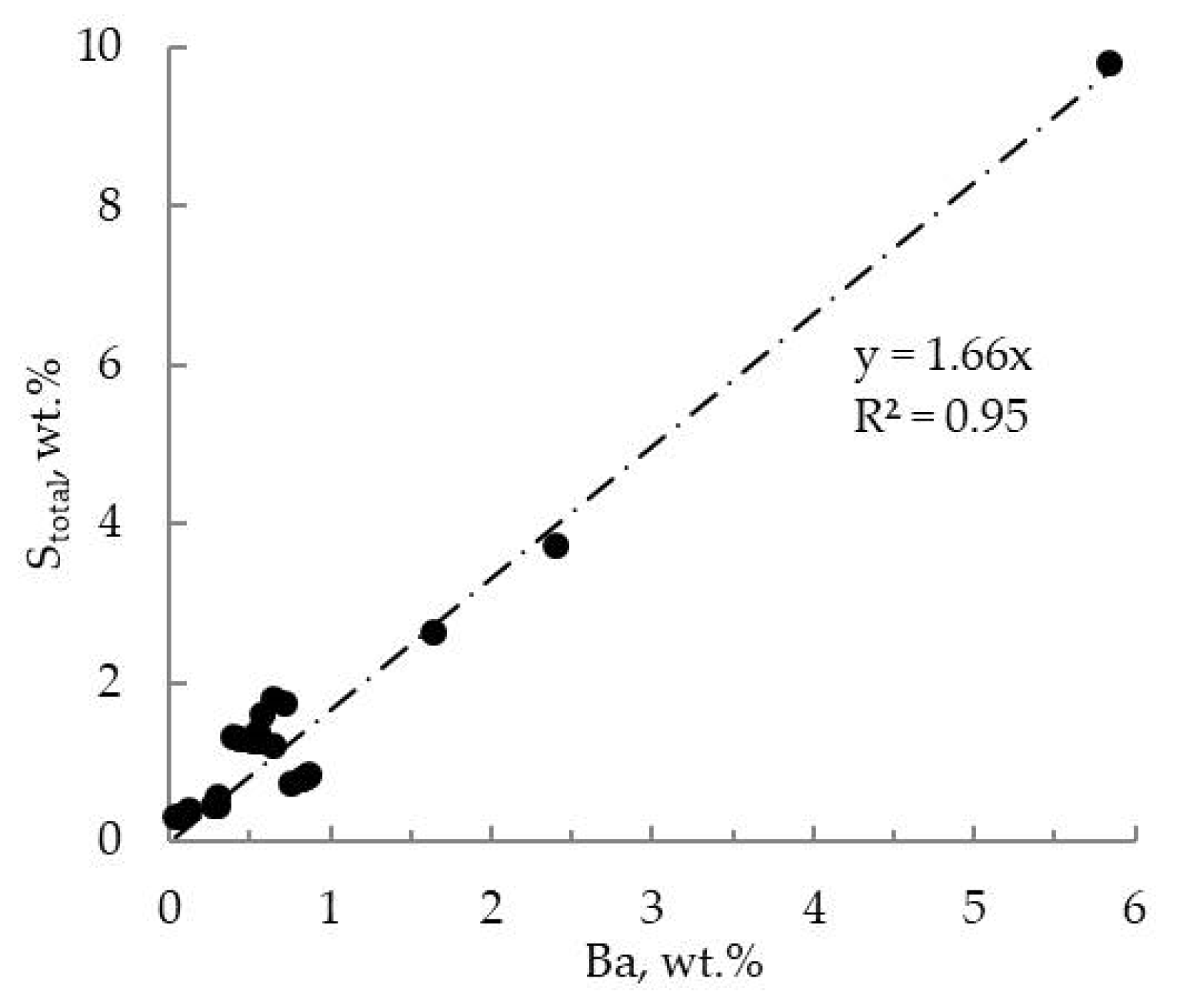

4.4. Wholerock Composition and Dominant Trace Elements

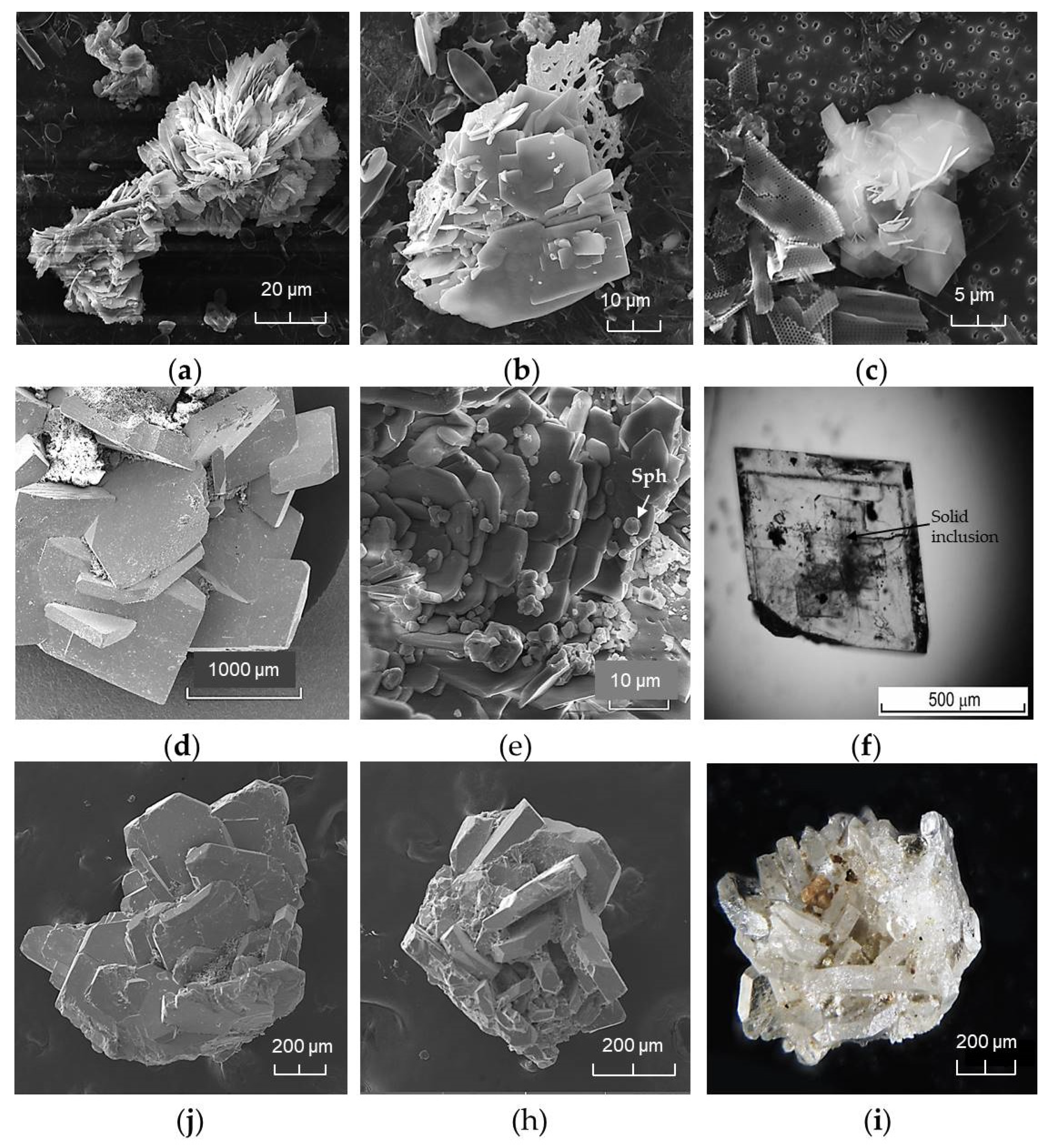

4.5. Barite Chrystal Morphology, Size and EDS Data

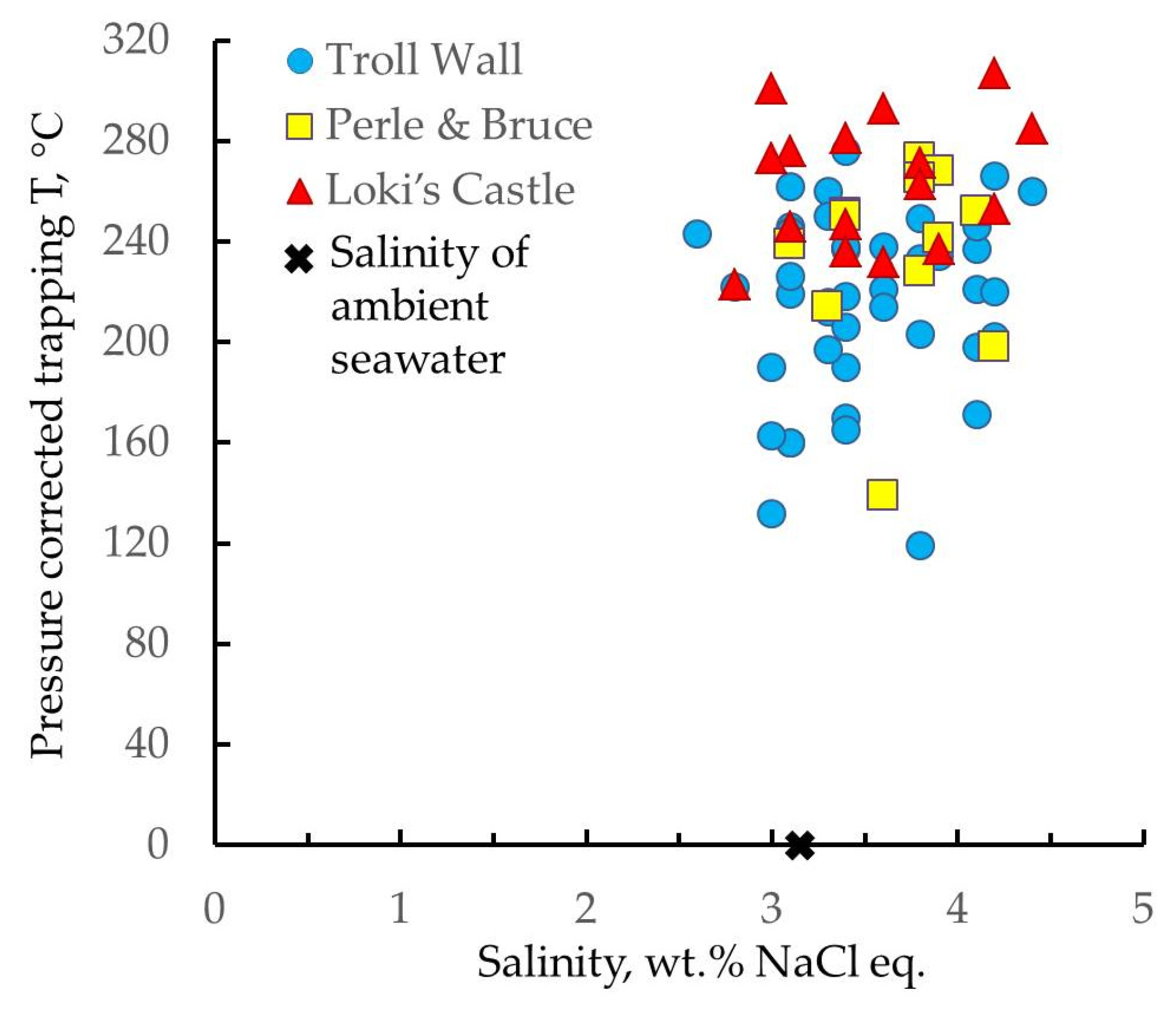

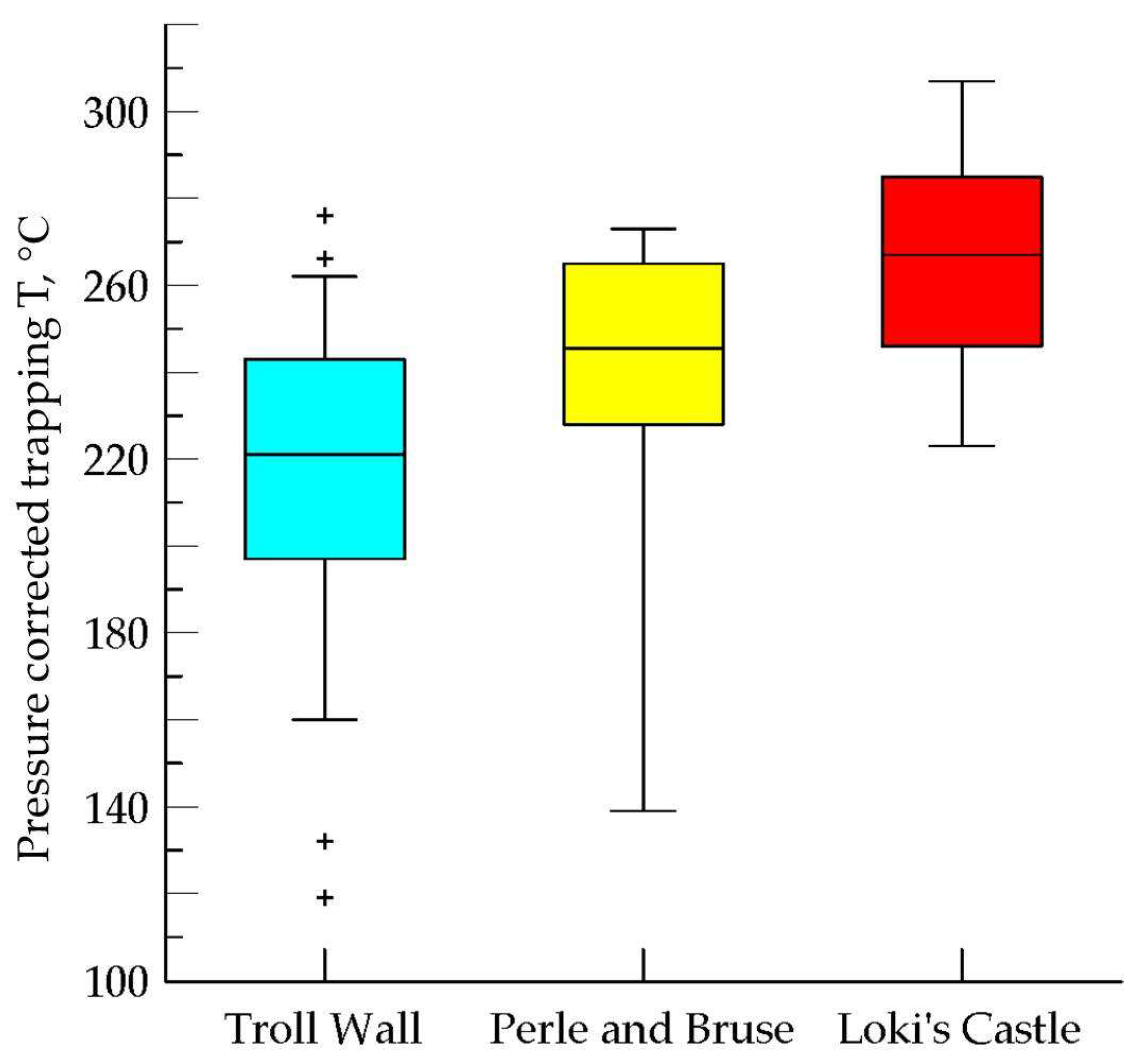

4.6. Fluid Inclusions Study

5. Discussion

5.1. Hydrothermal Vent Field Settings

5.2. Barite Hosted Rocks

5.3. Characterisation of Mineralised Material

5.4. Fluid Inclusions Hosted in Barites

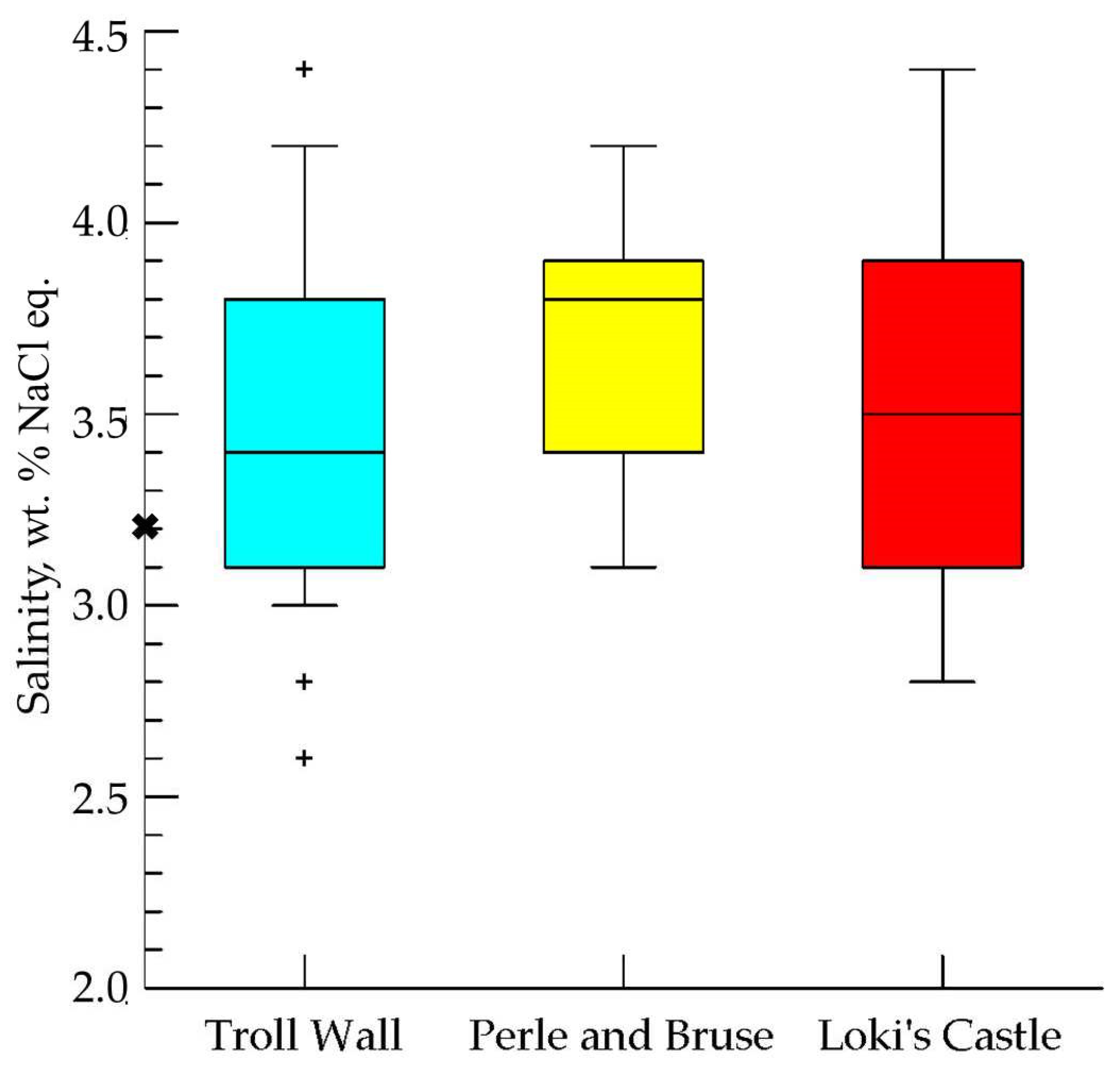

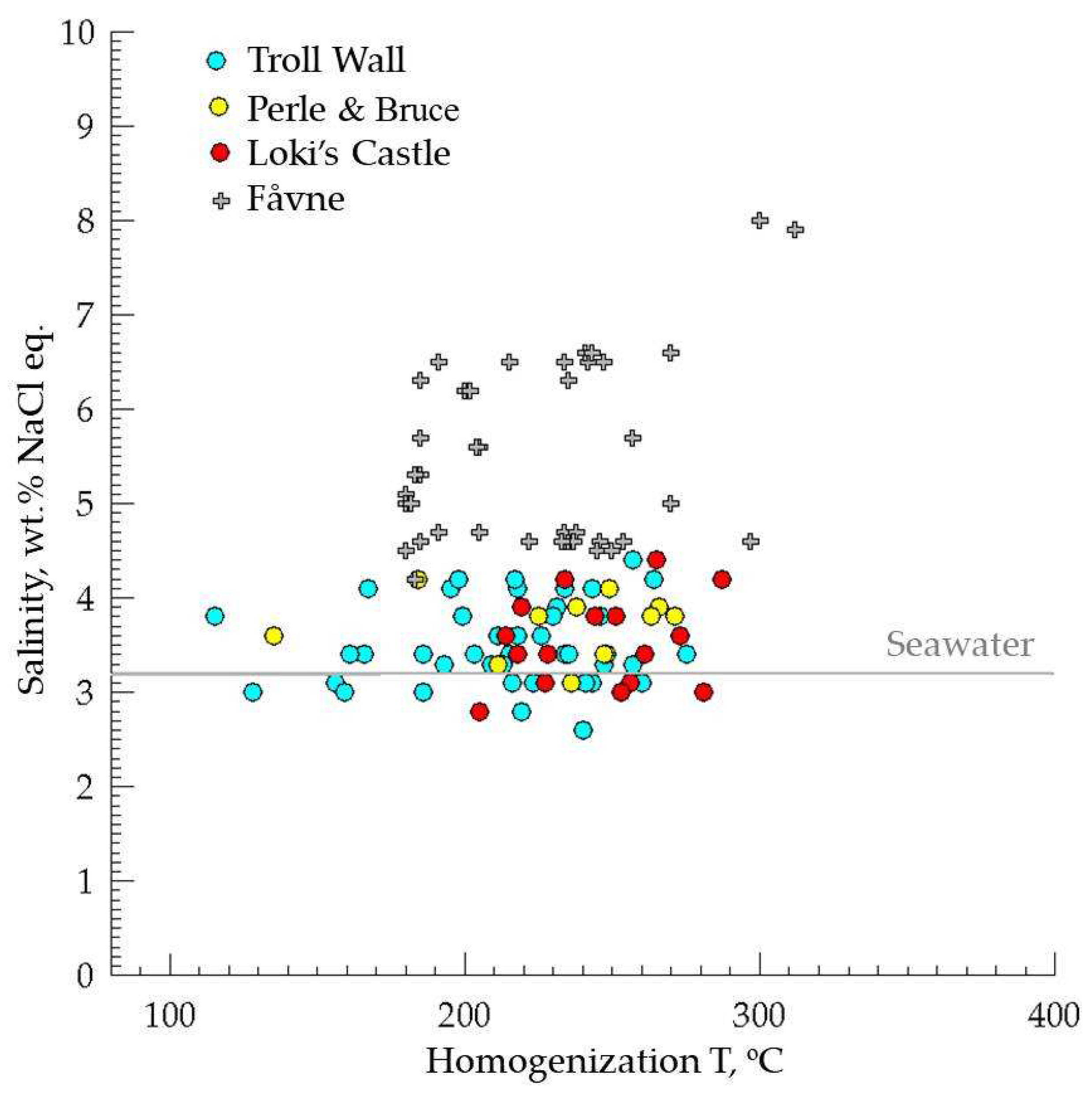

5.4.1. Troll Wall Vet Field

5.4.2. Perle & Bruce Vent Field

5.4.3. Loki’s Castel Vent Field

6. Conclusions and Perspectives

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Griffith, E.M.; Paytan, A. Barite in the ocean – occurrence, geochemistry and palaeoceanographic applications. Sedimentology 2012, 59, 1817–1835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chow, T.J.; Goldberg, E.D. On the marine geochemistry of barium. Geochimica et Cosmochimica Acta 1960, 20, 192–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horner, T.J.; Pryer, H.V.; Nielsen, S.G.; Crockford, P.W.; Gauglitz, J.M.; Wing, B.A.; Ricketts, R.D. Pelagic barite precipitation at micromolar ambient sulfate. Nature Communications 2017, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Horner, T.J.; Little, S.H.; Conway, T.M.; Farmer, J.R.; Hertzberg, J.E.; Janssen, D.J.; … Wuttig, K. Bioactive Trace Metals and Their Isotopes as Paleoproductivity Proxies: An Assessment Using GEOTRACES-Era Data. Global Biogeochemical Cycles 2021, John Wiley and Sons Inc. [CrossRef]

- Paytan, A.; Mearon, S.; Cobb, K.; Kastner, M. Origin of marine barite deposits: Sr and S isotope characterization. Geology 2002, 30, 747–750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lein, A.Y.; Kravchishina, M.D. Barium Geochemical Cycle in the Ocean. Lithology and Mineral Resources 2021, 56, 293–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martinez-Ruiz, F.; Paytan, A.; Gonzalez-Muñoz, M.T.; Jroundi, F.; Abad, M.M.; Lam, P.J.; … Kastner, M. Barite formation in the ocean: Origin of amorphous and crystalline precipitates. Chemical Geology 2019.; 511, 441–451. [CrossRef]

- Dean, W.E.; Schreiber, B.C. Marine evaporites. S.E.P.M. Short Course 4, Oklahoma City, 1978.

- Von Damm, K.L. Seafloor hydrothermal activity: black smoker chemistry and chimneys. Annual Review of Earth & Planetary Sciences 1990, 18, 173–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tivey, M.K. Generation of seafloor hydrothermal vent fluids and associated mineral deposits. Oceanography 2007, 20, 50–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lüders, V.; Pracejus, B.; Halbach, P. Fluid inclusion and sulfur isotope studies in probable modern analogue Kuroko-type ores from the JADE hydrothermal field (Central Okinawa Trough, Japan). Chemical Geology 2001, 173, 45–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peters, M.; Strauss, H.; Petersen, S.; Kummer, N.A.; Thomazo, C. Hydrothermalism in the Tyrrhenian Sea: Inorganic and microbial sulfur cycling as revealed by geochemical and multiple sulfur isotope data. Chemical Geology 2011, 280, 217–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eickmann, B.; Thorseth, I.H.; Peters, M.; Strauss, H.; Bröcker, M.; Pedersen, R.B. Barite in hydrothermal environments as a recorder of subseafloor processes: A multiple-isotope study from the Loki’s Castle vent field. Geobiology 2014, 12, 308–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Averyt, K.B.; Paytan, A. Empirical partition coefficients for Sr and Ca in marine barite: Implications for reconstructing seawater Sr and Ca concentrations. Geochemistry, Geophysics, Geosystems 2003, 4. [CrossRef]

- Albarède, F.; Michard, A.; Minster, J.F.; Michard, G. 87Sr86Sr ratios in hydrothermal waters and deposits from the East Pacific Rise at 21°N. Earth and Planetary Science Letters 1981, 55, 229–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monnin, C.; Jeandel, C.; Cattaldo, T.; Dehairs, F. The marine barite saturation state of the world’s oceans. Marine Chemistry 1999, 65, 253–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hannington, M.D.; Jonasson, I.R.; Herzig, P.M.; Petersen, S. Physical and chemical processes of seafloor mineralization at mid-ocean ridges. In Geophysical Monograph Series 1995, 91, pp–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jamieson, J.W.; Hannington, M.D.; Tivey, M.K.; Hansteen, T.; Williamson, N.M.B.; Stewart, M.; … Langer, J. Precipitation and growth of barite within hydrothermal vent deposits from the Endeavour Segment, Juan de Fuca Ridge. Geochimica et Cosmochimica Acta 2016, 173, 64–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lein, A.Y.; Bogdanov, Y.A.; Lisitzin, A.P. Processes of hydrothermal ore genesis in the World Ocean: The results of 35 years of research. Doklady Earth Sciences 2016, 466, 38–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsieh, Y.T.; Bridgestock, L.; Scheuermann, P.P.; Seyfried, W.E.; Henderson, G.M. Barium isotopes in mid-ocean ridge hydrothermal vent fluids: A source of isotopically heavy Ba to the ocean. Geochimica et Cosmochimica Acta 2021, 292, 348–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bogdanov, Y.A.; Lisitzin, A.P.; Binns, R.A.; Gorshkov, A.I.; Gurvich, E.G.; Dritz, V.A.; … Kuptsov, V.M. Low-temperature hydrothermal deposits of Franklin Seamount, Woodlark Basin, Papua New Guinea. Marine Geology 1997, 142, 99–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bogdanov, Y.A.; Lein, A.Y.; Sagalevich, A.M. Chemical composition of the hydrothermal deposits of the Menez Gwen vent field (Mid-Atlantic Ridge). Oceanology 2005, 45, 849–856. [Google Scholar]

- Lécuyer, C.; Dubois, M.; Marignac, C.; Gruau, G.; Fouquet, Y.; Ramboz, C. Phase separation and fluid mixing in subseafloor back arc hydrothermal systems; a microthermometric and oxygen isotope study of fluid inclusions in the barite–sulfide chimneys of the Lau Basin. Journal of Geophysical Research 1999, 104, 911–928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lein, A.Y.; Bogdanov, Y.A.; Maslennikov, V.V.; Li, S.; Ulyanova, N.V.; Maslennikova, S.P.; Ulyanov, A.A. Sulfide minerals in the Menez Gwen nonmetallic hydrothermal field (Mid-Atlantic Ridge). Lithology and Mineral Resources 2010, 45, 305–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Melekestseva, I.Y.; Tret’yakov, G.A.; Nimis, P.; Yuminov, A.M.; Maslennikov, V.V.; Maslennikova, S.P.; … Large, R. Barite-rich massive sulfides from the Semenov-1 hydrothermal field (Mid-Atlantic Ridge, 13°30.87’ N): Evidence for phase separation and magmatic input. Marine Geology 2014, 349, 37–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bodnar, R.J.; Vityk, M.O. Interpretation of microthermometric data for H2O−NaCl fluid inclusions. In Fluid inclusions in minerals: methods and applications. Pontignano: Siena, 1994; pp. 117−130.

- Bodnar, R.J.; Lecumberri-Sanchez, P.; Moncada, D.; Steele-MacInnis, M. Fluid Inclusions in Hydrothermal Ore Deposits. In Treatise on Geochemistry: Second Edition, Elsevier Inc.; 2014, Volume 13; pp. 119–142. [CrossRef]

- Prokofiev, V.Yu.; Naumov, V.B. Prokofiev V.Yu.; Naumov V.B. Physicochemical Parameters and Geochemical Features of Ore-Forming Fluids for Orogenic Gold Deposits Throughout Geological Time. Minerals 2020, 10 (1). 50.

- Prokofiev, V.Y.; Naumov, V.B. Ranges of Physical Parameters and Geochemical Features of Mineralizing Fluids at Porphyry Deposits of Various Types of the Cu-Mo-Au System: Evidence from Fluid Inclusions Data. Minerals 2022, (5), 529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elsgaard, L.; Isaksen, M.F.; Jørgensen, B.B.; Alayse, A.M.; Jannasch, H.W. Microbial sulfate reduction in deep-sea sediments at the Guaymas Basin hydrothermal vent area: Influence of temperature and substrates. Geochimica et Cosmochimica Acta 1994, 58, 3335–3343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chi, G.; Diamond, L.W.; Lu, H.; Lai, J.; Chu, H. Common problems and pitfalls in fluid inclusion study: A review and discussion. Minerals 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pedersen, R.B.; Rapp, H.T.; Thorseth, I.H.; Lilley, M.D.; Barriga, F.J.A.S.; Baumberger, T.; … Jorgensen, S.L. Discovery of a black smoker vent field and vent fauna at the Arctic Mid-Ocean Ridge. Nature Communications 2010, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baumberger, T.; Früh-Green, G.L.; Thorseth, I.H.; Lilley, M.D.; Hamelin, C.; Bernasconi, S.M.; … Pedersen, R.B. Fluid composition of the sediment-influenced Loki’s Castle vent field at the ultra-slow spreading Arctic Mid-Ocean Ridge. Geochimica et Cosmochimica Acta 2016, 187, 156–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stensland, A.; Baumberger, T.; Mork, K.A.; Lilley, M.D.; Thorseth, I.H.; Pedersen, R.B. 3He along the ultraslow spreading AMOR in the Norwegian-Greenland Seas. Deep-Sea Research Part I: Oceanographic Research Papers 2019, 147, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roedder, E. Fluid inclusions: Reviews in Mineralogy 1984, Volume 12, 646 p.

- Naumov, V.B.; Dorofeeva, V.A.; Mironova, O.F. (2009). Principal physicochemical parameters of natural mineral-forming fluids. Geochemistry International, 47(8), 777–802. [CrossRef]

- Sahlström, F.; Strmić Palinkaš, S.; Hjorth Dundas, S.; Sendula, E.; Cheng, Y.; Wold, M.; Pedersen, R.B. (2023). Mineralogical distribution and genetic aspects of cobalt at the active Fåvne and Loki’s Castle seafloor massive sulfide deposits, Arctic Mid-Ocean Ridges. Ore Geology Reviews. [CrossRef]

- Cruz, M.I.F.S. Mineralogy and Geochemistry of contrasting hydrothermal systems on the Arctic Mid Ocean Ridge (AMOR): The Jan Mayen and Loki's Castle vent fields. Doutoramento em Ciências do Mar. Univeridadae de Lisboa. Faculdade de Ciências. 2015. 257 p.

- Strmic Palinkas, S.; Pedersen, R.B.; Sahlström, F. (2020). Sulfide Mineralization and Fluid Inclusion Characteristics of Active Ultramafic- and Basalt-Hosted Hydrothermal Vents Located along the Arctic Mid-Ocean Ridges (AMOR) (pp. 2472–2472). Geochemical Society. [CrossRef]

- Fouquet, Y.; Cambon, P.; Etoubleau, J.; Charlou, J.L.; Ondréas, H.; Barriga, F.J.A.S.; … Rouxel, O. Geodiversity of hydrothermal processes along the Mid-Atlantic Ridge and ultramafic-hosted mineralization: A new type of oceanic Cu-Zn-Co-Au volcanogenic massive sulfide deposit. Geophysical Monograph Series 2013, 188, 321–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klingelhöfer, F.; Géli, L.; Matias, L.; Steinsland, N.; Mohr, J. Crustal structure of a super-slow spreading centre: A seismic refraction study of Mohns Ridge, 72°N. Geophysical Journal International 2000, 141, 509–526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Juliani, C.; Ellefmo, S.L. Probabilistic estimates of permissive areas for undiscovered seafloor massive sulfide deposits on an Arctic Mid-Ocean Ridge. Ore Geology Reviews 2018, 95, 917–930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geli, L.; Renard, V.; Rommevaux, C. Ocean crust formation processes at very slow spreading centers: a model for the Mohns Ridge, near 72°N, based on magnetic, gravity, and seismic data. Journal of Geophysical Research 1994, 99, 2995–3013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kokhan, A.V.; Dubinin, E.P.; Grokhol’sky, A.L. Geodynamic features of the structure generation in the spreading ridges of Arctic and Polar Atlantic // Vestnik KRAUNTS. Earth Sciences. 2012. №1. Vol.19. P. 59-77 (in Russian).

- Reimers, H. The Morphology of the Mohn's Ridge with Special Focus on Listric and Detachment Faults and their Link to the Formation of Seafloor-massive Sulfides. Thesis Norwegian University of Science and Technology, Department of Geoscience and Petroleum, 2017. https://ntnuopen.ntnu.no/ntnu-xmlui/bitstream/handle/11250/2452116/14120_FULLTEXT.pdf?sequence=1.

- Pedersen, R.B.; Thorseth, I.H.; Nygård, T.E.; Lilley, M.D.; Kelley, D.S. Hydrothermal Activity at the Arctic Mid-Ocean Ridges. In Diversity of Hydrothermal Systems on Slow Spreading Ocean Ridges, Wiley, 2013; pp. 67–89. [CrossRef]

- Schander, C.; Rapp, H.T.; Kongsrud, J.A.; Bakken, T.; Berge, J.; Cochrane, S.; … Pedersen, R.B. (2010). The fauna of hydrothermal vents on the Mohn Ridge (North Atlantic). Marine Biology Research. [CrossRef]

- Johannessen, K.C.; Vander Roost, J.; Dahle, H.; Dundas, S.H.; Pedersen, R.B.; Thorseth, I.H. Environmental controls on biomineralization and Fe-mound formation in a low-temperature hydrothermal system at the Jan Mayen Vent Fields. Geochimica et Cosmochimica Acta 2017, 202, 101–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Snook, B.; Drivenes, K.; Rollinson, G.K.; Aasly, K. Characterisation of mineralised material from the Loki’s castle hydrothermal vent on the Mohn’s ridge. Minerals 2018, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramirez-Llodra E, Hilario A, Paulsen E, Costa CV, Bakken T, Johnsen G and Rapp HT. Benthic Communities on the Mohn’s Treasure Mound: Implications for Management of Seabed Mining in the Arctic Mid-Ocean Ridge. Front. Mar. Sci. 2020, 7:490. [CrossRef]

- Elkins, L.J.; Hamelin, C.; Blichert-Toft, J.; Scott, S.R.; Sims, K.W.W.; Yeo, I.A.; … Pedersen, R.B. North Atlantic hotspot-ridge interaction near Jan Mayen Island. Geochemical Perspectives Letters 2016, 2, 55–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pedersen, RB, Bjerkgård, T. Sea-floor massive sulphides in Arctic waters. In: Mineral Resources in the Arctic. 2016; pp 209–216. Retrieved from https://www.ngu.no/upload/Aktuelt/CircumArtic/5_SMS.

- Kravchishina, M.D.; Kuznetsov, A.B.; Baranov, B.V.; Dara, O.M.; Starodymova, D.P.; Klyuvitkin, A.A.; … Lein, A.Y. Hydrothermal Genesis of Fe–Mn Crust in the Southernmost Segment of the Mohns Ridge, Norwegian Sea: REE Geochemistry and Sr and Nd Isotopic Composition. Doklady Earth Sciences 2022, 506, 734–739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klyuvitkin, A.A.; Kravchishina, M.D.; Nemirovskaya, I.A.; Baranov, B.V.; Kochenkova, A.I.; Lisitzin, A.P. Studies of Sediment Systems of the European Arctic during Cruise 75 of the R/V Akademik Mstislav Keldysh. Oceanology 2020, 60, 421–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kruber, C.; Thorseth, I.H.; Pedersen, R.B. Seafloor alteration of basaltic glass: Textures, geochemistry, and endolithic microorganisms. Geochemistry, Geophysics, Geosystems 2008, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stokke, R.; Reeves, E.P.; Dahle, H.; Fedøy, A.E.; Viflot, T.; Lie Onstad, S.; … Steen, I.H. Tailoring Hydrothermal Vent Biodiversity Toward Improved Biodiscovery Using a Novel in situ Enrichment Strategy. Frontiers in Microbiology 2020, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Humphris, S.E.; Tivey, M.K.; Tivey, M.A. The Trans-Atlantic Geotraverse hydrothermal field: A hydrothermal system on an active detachment fault. Deep-Sea Research Part II: Topical Studies in Oceanography 2015, 121, 8–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klyuvitkin, A.A.; Kravchishina, M.D.; Boev, A.G. Particle Fluxes in Hydrothermal Vent Fields of the Southern Part of the Mohns Ridge. Doklady Earth Sciences 2021, 497, 200–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kravchishina, M.D.; Novigatskii, A.N.; Savvichev, A.S.; Pautova, L.A.; Lisitsyn, A.P. Studies on Sedimentary Systems in the Barents Sea and Norwegian–Greenland Basin during Cruise 68 of the R/V Akademik Mstislav Keldysh. Oceanology 2019, 59, 158–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bezrukov, P.L.; Lisitzin, A.P. Classification of bottom sediments in modern marine reservoirs. Trudy Inst. Oceanol. 1960, 32, 3–14. (In Russian) [Google Scholar]

- Lisitzin, A.P. Oceanic Sedimentation: Lithology and Geochemistry. American Geophysical Union, Washington, D.C. 1996. [CrossRef]

- Brown, P.E. Brown P.E. & Lamb W M. P-V-T properties of fluids in the system H2O ± CO2 ± NaCl: New graphical presentations and implications for fluid inclusion studies // Geochimica et Cosmochimica Acta. 1989. V.53. № 6. P. 1209-1222.

- Borisenko A., S. Cryometric study of salt composition of gas–liquid inclusions in minerals. Russian Geol. and Geofis. 1977, No.8, 16–27. [Google Scholar]

- Brown, P. FLINCOR: a computer program for the reduction and investigation of fluid inclusion data // Amer. Mineralogist. 1989. V. 74. P. 1390–1393.

- et al. Geological Society of America Bulletin Distribution of the Elements in Some Major Units of the Earth ’ s Crust. Geological Society of America BulletinAmerica 1961, 72, 175–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boström, K.; Peterson, M.N.A.; Joensuu, O.; Fisher, D.E. Aluminum-poor ferromanganoan sediments on active oceanic ridges. Journal of Geophysical Research 1969, 74, 3261–3270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonatti, E.; Joensuu, O. Deep-sea iron deposit from the South Pacific. Science 1966, 154, 643–645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bonatti, E. Kraemer T.; Rydell H. Classification and genesis of submarine iron-manganese deposits, 1972.

- Stubseid, H.H.; Bjerga, A.; Haflidason, H.; Pedersen, R.B. Volcanic evolution of an ultraslow-spreading ridge. Nature Portfolio 2023, Preprint. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bas, M.J.L.; Maitre, R.W.L.; Streckeisen, A.; Zanettin, B. A chemical classification of volcanic rocks based on the total alkali-silica diagram. Journal of Petrology 1986, 27, 745–750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sushchevskaya, N. M., G. A. Cherkashev, T.I.; Tsekhonya, Yu. A.; Bogdanov, B.V. Belyatskiy, and N. N. Kononkova Magmatism of Mon and Knipovich ridges, polar Atlantics spreading zones, petrogeochemical study, Mid-Atlantic Ridge. Russian Journal of Earth Sciences 2000, 2, 243–267. [CrossRef]

- Langmuir, C.; Humphris, S.; D. ; Fomari, C. Van Dover, K. Von Damm, M.K. Tivey, D.; Colodner, J.-L. Charlou D.; Desonie, I. C.; Wilson, Y.; Fouquet, G.; Klinkhammer, H. BougaultHydrothermal vents near a mantle hot spot: the Lucky Strike vent field at 370 N on the Mid-Atlantic Ridge. Earth and Planetary Science Letters 1997, 48, 69–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eldridge, C.S.; Barton, P.B.; Ohmoto, H. Mineral Textures and Their Bearing on Formation of the Kuroko Orebodies. In The Kuroko and Related Volcanogenic Massive Sulfide Deposits. Society of Economic Geologists, 2019. [CrossRef]

- Kravchishina, M.D.; Lein, A.Y.; Boev, A.G.; Prokofiev, V.Y.; Starodymova, D.P.; Dara, O.M.; … Lisitzin, A.P. Hydrothermal Mineral Assemblages at 71° N of the Mid-Atlantic Ridge (First Results). Oceanology 2019, 59, 941–959. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feely, R.A.; Gendron, J.F.; Baker, E.T.; Lebon, G.T. Hydrothermal plumes along the East Pacific Rise, 8°40′ to 11°50′N: Particle distribution and composition. Earth and Planetary Science Letters 1994, 128, 19–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phase Equilibria, Crystallographic and Thermodynamic Data of Binary Alloys. Phase Equilibria, Crystallographic and Thermodynamic Data of Binary Alloys. Springer Berlin Heidelberg, 2016. [CrossRef]

- Kullerud, G. The FeS–ZnS system, a geological thermometer // Norsk Geologisk Tiddsskrift. 1953. V. 32. P. 61–147.

- Maslennikov, V.V.; Cherkashov, G.A.; Firstova, A.V.; Ayupova, N.R.; Beltenev, V.E.; Melekestseva, I.Y.; … Blinov, I.A. Trace Element Assemblages of Pseudomorphic Iron Oxyhydroxides of the Pobeda-1 Hydrothermal Field, 17°08.7′ N, Mid-Atlantic Ridge: The Development of a Halmyrolysis Model from LA-ICP-MS Data. Minerals 2023, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bortnikov, N.S.; Simonov, V.A.; Bogdanov, Y.A. Fluid inclusions in minerals from modern sulfide edifices: Physicochemical conditions of formation and evolution of fluids. Geology of Ore Deposits 2004, 46, 64–75. [Google Scholar]

- Fontaine, F.J.; Wilcock, W.S.D. Dynamics and storage of Brine in mid-ocean ridge hydrothermal systems. Journal of Geophysical Research: Solid Earth 2006, 111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dahle, H.; Le Moine Bauer, S.; Baumberger, T.; Stokke, R.; Pedersen, R.B.; Thorseth, I.H.; Steen, I.H. Energy landscapes in hydrothermal chimneys shape distributions of primary producers. Frontiers in Microbiology 2018, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bogdanov, Y.A.; Bortnikov, N.S.; Vikent’ev, I.V.; Lein, A.Y.; Gurvich, E.G.; Sagalevich, A.M.; … Apollonov, V.N. Mineralogical-geochemical peculiarities of hydrothermal sulfide ores and fluids in the rainbow field associated with serpentinites, Mid-Atlantic Ridge (36°C14’ N). Geologiya Rudnykh Mestorozhdenij 2002, 44, 510–543. [Google Scholar]

- Petersen, S.; Herzig, P.M.; Schwarz-Schampera, U.; Hannington, M.D.; Jonasson, I.R. Hydrothermal precipitates associated with bimodal volcanism in the Central Bransfield Strait, Antarctica. Mineralium Deposita 2004, 39, 358–379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Von Damm, K.L. Controls on the chemistry and temporal variability of seafloor hydrothermal fluids. In Geophysical Monograph Series, 1995, Volume 91, Blackwell Publishing Ltd.; pp. 222–247. [CrossRef]

- Von Damm, K.L. Systematics of and postulated controls on submarine hydrothermal solution chemistry. Journal of Geophysical Research 1988, 93, 4551–4561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kelley, D.S.; Gillis, K.M.; Thompson, G. Fluid evolution in submarine magma-hydrothermal systems at the Mid- Atlantic Ridge. Journal of Geophysical Research 1993, 98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kelley, D.S.; Shank, T.M. Hydrothermal systems: a decade of discovery in slow spreading environments. In: Rona, P.A., et al. (Eds.), “Diversity of Hydrothermal Systems on Slow Spreading Ocean Ridges” Geophysical monograph, 188, 2010; pp. 369–407.

- Bischoff, J.L.; Rosenbauer, R.J. Salinity variations in submarine hydrothermal systems by layered double-diffusive convection. Journal of Geology 1989, 97, 613–623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michael, P.J.; Cornell, W.C. Influence of spreading rate and magma supply on crystallization and assimilation beneath mid-ocean ridges: Evidence from chlorine and major element chemistry of mid-ocean ridge basalts. Journal of Geophysical Research: Solid Earth 1998, 103, 18325–18356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koschinsky, A.; Schmidt, K.; Garbe-Schönberg, D. Geochemical time series of hydrothermal fluids from the slow-spreading Mid-Atlantic Ridge: Implications of medium-term stability. Chemical Geology 2020, 552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tivey, M.K.; Mills, R.A.; Teagle, D.A.H. Temperature and salinity of fluid inclusions in anhydrite as indicators of seawater entrainment and heating in the TAG active mound. Proceedings of the Ocean Drilling Program: Scientific Results 1998, 158, 179–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petersen, S.; Herzig, P.M.; Hannington, M.D. Fluid inclusion studies as a guide to the temperature regime within the TAG hydrothermal mound, 26°N, Mid-Atlantic Ridge. Proceedings of the Ocean Drilling Program: Scientific Results 1998, 158, 163–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bortnikov, N.S.; Simonov, V.A.; Fouquet, Y.; Amplieva, E.E. Phase separation of fluid in the Ashadze deep-sea modern submarine hydrothermal field (mid-atlantic ridge, 12°58s’ N): Results of fluid inclusion study and direct observations. Doklady Earth Sciences 2010, 435, 1446–1449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The appendix contain the data supplemental to the main text for this article The appendix contain the data supplemental to the main text for this article Hou, Z.; Zhang, Q. CO2-Hydrocarbon fluids of the Jade hydrothermal field in the Okinawa trough: Fluid inclusion evidence. Science in China, Series D: Earth Sciences 1998, 41, 408–415. [CrossRef]

| Mineral | Formula | Abundance | Content range, wt. % |

|---|---|---|---|

| Troll Wall, proximal sediments | |||

| Smectite (partially hydrothermal) |

O | Major | 15–62 |

| Fe-Si oxyhydroxides | Fe amorphous silica | Major | n.d. |

| Barite | ) | Major | 3–85 |

| Gypsum | CaSO4 · 2H2O | Major | 1–11 |

| Pyrite | (cubic) | Major | 4–99 |

| Marcasite | (rhombic) | Major | 4–87 |

| Sphalerite | ZnS | Major | 1–10 |

| Chalcopyrite | CuFeS2 | Minor | 1–2 |

| Bernessite | (Na,Ca)0.5(Mn4+,Mn3+)2O4 · 1.5H2O | Minor | n.d. |

| Buserite I | Na4Mn14O27 · 21H2O | Minor | n.d. |

| Asbolane– Buserite | mixed-layer Mn formation | Minor | n.d. |

| Chlorite–smectite | mixed-layer cay formation | Minor | 0–37 |

| Wurtzite | (Zn,Fe)S | Rare | 2–5 |

| Goethite | α-FeO(OH) | Rare | 1–53 |

| Lepidocroquite | ɣ-FeO(OH) | Rare | 0–25 |

| X-ray amorphous clay | ultrafine structurally defective clay formation | Rare | n.d.* |

| Mordenite | O | Rare | 0–93 |

| Jarosite | (SO4)2(OH)6 | Rare | 13 |

| Perle & Bruse, distal sediments | |||

| Smectite (partially hydrothermal) |

O | Major | n.d. |

| Barite | ) | Major | 1–6 |

| Gypsum | CaSO4 · 2H2O | Major | 1–6 |

| Bernessite | (Na,Ca)0.5(Mn4+,Mn3+)2O4 · 1.5H2O | Major | n.d. |

| Buserite I | Na4Mn14O27 · 21H2O | Major | n.d. |

| Fe-oxydes | Fe2O3 | Major | n.d. |

| Pyrite | (cubic) | Minor | 1–2 |

| Smectite–illite (partially hydrothermal) |

mixed-layer clay formation | Rare | 2–4 |

| Buserite II | Na4Mn14O27 · 21H2O, heat resistant | Rare | n.d. |

| Asbolane | O | Rare | n.d. |

| Asbolane–Buserite | mixed-layer Mn formation | Rare | n.d. |

| Loki’s Castle, proximal sediments | |||

| Smectite (mostly hydrothermal) |

O | Major | 10–30 |

| Talc | Major | 1–95 | |

| Pyrite | (cubic) | Major | 3–18 |

| Pyrrhotite hexagonal | Major | 5–81 | |

| Chalcopyrite | CuFeS2 | Major | 2–75 |

| Sphalerite | ZnS | Major | 2–13 |

| Barite | ) | Major | 2–28 |

| Sulfur native | S | Major | 4–34 |

| Goethite | α-FeO(OH) | Major | 3–18 |

| Chlorite–smectite | mixed-layer clay formation | Minor | n.d. |

| Pyrrhotite monoclinic | Minor | 5–15 | |

| Marcasite | FeS2 (rhombic) | Minor | 3–30 |

| Lepidocroquite | ɣ-FeO(OH) | Minor | 1–24 |

| Gypsum | CaSO4 · 2H2O | Minor | 1–8 |

| Talc-like mineral–smectite | mixed-layer formation withMg-Fe phyllosilicate | Minor | n.d. |

| Galenite | PbS | Rare | 2–3 |

| Famatinite | Cu3SbS4 | Rare | 0–4 |

| Paratacamite | Cu3(Cu, Zn)(OH)6Cl2 | Rare | 0–58 |

| Jarosite | Rare | 0–35 | |

| Station, depth, layer |

Type of FIs* |

n |

Тhom, °С |

Тeut, °С |

Тice melt, °С |

Salinity, wt.% NaCl eq. |

d, g·сm-3 |

T**, °С |

Тcryst***, °С |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Troll Wall vent field, depth of 512–600 m | |||||||||

| 6131 | P | 8 | 275 | -33 | -2.1 | 3.4 | 0.80 | 1 | 276 |

| 512 m | P | 4 | 246 | -31 | -2.3 | 3.8 | 0.84 | 3 | 249 |

| 0–20 cm | P | 4 | 218 | -33 | -2.5 | 4.1 | 0.88 | 3 | 221 |

| P | 5 | 217 | -31 | -2.6 | 4.2 | 0.88 | 3 | 220 | |

| P-S | 3 | 195 | -31 | -2.5 | 4.1 | 0.90 | 3 | 198 | |

| P-S | 2 | 167 | -25 | -2.5 | 4.1 | 0.93 | 4 | 171 | |

| S | 2 | 115 | -27 | -2.3 | 3.8 | 0.98 | 4 | 119 | |

| 6131 | P | 7 | 264 | -33 | -2.6 | 4.2 | 0.82 | 2 | 266 |

| 512 m | P | 6 | 234 | -32 | -2.1 | 3.4 | 0.85 | 3 | 237 |

| 1–9 cm | P | 5 | 234 | -32 | -2.1 | 3.4 | 0.85 | 3 | 237 |

| P | 8 | 216 | -31 | -1.9 | 3.1 | 0.87 | 3 | 219 | |

| P | 6 | 215 | -34 | -2.1 | 3.4 | 0.88 | 3 | 218 | |

| P-S | 5 | 186 | -33 | -2.1 | 3.4 | 0.91 | 4 | 190 | |

| S | 3 | 156 | -34 | -1.9 | 3.1 | 0.94 | 4 | 160 | |

| S | 6 | 156 | -32 | -1.7 | 3.1 | 0.94 | 4 | 160 | |

| 6137 | P | 8 | 234 | -33 | -2.5 | 4.1 | 0.86 | 3 | 237 |

| 600 m | P | 6 | 231 | -34 | -2.4 | 3.9 | 0.86 | 3 | 234 |

| 0–5 cm | P | 7 | 230 | -32 | -2.3 | 3.8 | 0.86 | 3 | 233 |

| P | 4 | 223 | -30 | -1.9 | 3.1 | 0.86 | 3 | 226 | |

| P | 10 | 219 | -32 | -1.7 | 2.8 | 0.87 | 3 | 222 | |

| P | 6 | 218 | -30 | -2.2 | 3.6 | 0.87 | 3 | 221 | |

| P | 5 | 213 | -34 | -2.0 | 3.3 | 0.88 | 3 | 216 | |

| P | 7 | 211 | -33 | -2.2 | 3.6 | 0.88 | 3 | 214 | |

| P-S | 5 | 193 | -31 | -2.0 | 3.3 | 0.90 | 4 | 197 | |

| P-S | 5 | 166 | -32 | -2.1 | 3.4 | 0.93 | 5 | 170 | |

| P-S | 3 | 161 | -33 | -2.1 | 3.4 | 0.93 | 4 | 165 | |

| S | 4 | 159 | -30 | -1.8 | 3.0 | 0.93 | 4 | 163 | |

| 5516 | P | 3 | 260 | -35 | -1.9 | 3.1 | 0.81 | 2 | 262 |

| 540 m | P | 2 | 257 | -30 | -2.0 | 3.3 | 0.82 | 3 | 260 |

| 0–3 cm | P | 2 | 257 | -34 | -2.7 | 4.4 | 0.83 | 3 | 260 |

| P | 16 | 247 | -33 | -2.0 | 3.3 | 0.83 | 3 | 250 | |

| P | 3 | 243 | -31 | -2.5 | 4.1 | 0.85 | 3 | 246 | |

| P | 5 | 243 | -32 | -1.9 | 3.1 | 0.84 | 3 | 246 | |

| P | 3 | 241 | -31 | -1.9 | 3.1 | 0.84 | 3 | 244 | |

| P | 2 | 240 | -32 | -1.6 | 2.6 | 0.84 | 3 | 243 | |

| P | 2 | 235 | -32 | -2.1 | 3.4 | 0.85 | 3 | 238 | |

| P | 4 | 226 | -32 | -2.2 | 3.6 | 0.86 | 3 | 238 | |

| P | 8 | 209 | -30 | -2.0 | 3.3 | 0.88 | 3 | 212 | |

| P | 3 | 203 | -32 | -2.1 | 3.4 | 0.89 | 3 | 206 | |

| P | 5 | 199 | -31 | -2.3 | 3.8 | 0.90 | 4 | 203 | |

| P | 5 | 198 | -33 | -2.6 | 4.2 | 0.90 | 4 | 202 | |

| P | 4 | 186 | -33 | -1.8 | 3.0 | 0.91 | 4 | 190 | |

| P | 2 | 128 | -30 | -1.8 | 3.0 | 0.96 | 4 | 132 | |

| Perl & Bruce vent field, depth of 620 m | |||||||||

| 6146 | P | 3 | 271 | -30 | -2.3 | 3.8 | 0.80 | 2 | 273 |

| 620 m | P | 4 | 266 | -34 | -2.4 | 3.9 | 0.81 | 2 | 268 |

| 0–9 cm | P | 6 | 263 | -32 | -2.3 | 3.8 | 0.81 | 2 | 265 |

| P | 4 | 249 | -31 | -2.5 | 4.1 | 0.84 | 3 | 252 | |

| P | 3 | 248 | -31 | -2.1 | 3.4 | 0.83 | 3 | 251 | |

| P | 3 | 247 | -27 | -2.1 | 3.4 | 0.83 | 3 | 250 | |

| P | 6 | 238 | -34 | -2.4 | 3.9 | 0.85 | 3 | 241 | |

| P | 7 | 236 | -32 | -1.9 | 3.1 | 0.83 | 3 | 239 | |

| P-S | 4 | 225 | -33 | -2.3 | 3.8 | 0.87 | 3 | 228 | |

| P-S | 5 | 211 | -32 | -2.0 | 3.3 | 0.88 | 3 | 214 | |

| P-S | 2 | 184 | -30 | -2.6 | 4.2 | 0.92 | 4 | 198 | |

| S | 3 | 135 | -28 | -2.2 | 3.6 | 0.96 | 4 | 139 | |

| Loki’s Castle vent field, depth of 2376 m | |||||||||

| 6147 | P | 13 | 287 | -32 | -2.6 | 4.2 | 0.78 | 20 | 307 |

| 2376 m | P | 4 | 281 | -35 | -1.8 | 3.0 | 0.77 | 20 | 301 |

| 0–12 cm | P | 7 | 273 | -32 | -2.2 | 3.6 | 0.79 | 20 | 293 |

| P | 2 | 265 | -31 | -2.7 | 4.4 | 0.82 | 20 | 285 | |

| P | 4 | 261 | -33 | -2.1 | 3.4 | 0.81 | 20 | 281 | |

| P | 5 | 256 | -34 | -1.9 | 3.1 | 0.82 | 20 | 276 | |

| P | 6 | 253 | -33 | -1.8 | 3.0 | 0.82 | 20 | 273 | |

| P | 2 | 251 | -33 | -2.3 | 3.8 | 0.83 | 20 | 271 | |

| P | 3 | 244 | -30 | -2.3 | 3.8 | 0.84 | 19 | 263 | |

| P | 9 | 234 | -35 | -2.6 | 4.2 | 0.86 | 19 | 253 | |

| P | 6 | 228 | -34 | -2.1 | 3.4 | 0.86 | 19 | 247 | |

| P-S | 2 | 227 | -30 | -1.9 | 3.1 | 0.86 | 19 | 246 | |

| P-S | 6 | 219 | -31 | -2.4 | 3.9 | 0.88 | 18 | 237 | |

| P-S | 7 | 218 | -31 | -2.1 | 3.4 | 0.87 | 18 | 236 | |

| P-S | 5 | 214 | -33 | -2.2 | 3.6 | 0.88 | 18 | 232 | |

| P-S | 7 | 205 | -32 | -1.7 | 2.8 | 0.88 | 18 | 223 | |

| Grain | Ba | Sr | Ca | Fe | Co | S | O | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hydrothermally altered sediments of the Troll Wall | ||||||||

| 1 | 57.60 | 1.99 | 0.26 | 0.44 | n.d. | 14.68 | 24.53 | 99.50 |

| 2 | 55.58 | 3.20 | 0.21 | 0.71 | n.d. | 15.14 | 26.53 | 101.37 |

| 3 | 57.69 | 1.33 | n.d.* | 0.51 | n.d. | 14.62 | 25.52 | 99.68 |

| 4 | 57.19 | 2.03 | n.d. | 0.93 | n.d. | 15.13 | 25.95 | 101.24 |

| 5 | 56.03 | 2.79 | n.d. | 0.60 | n.d. | 14.84 | 23.80 | 98.06 |

| 6 | 58.28 | 1.18 | n.d. | 0.57 | n.d. | 14.66 | 25.47 | 100.15 |

| Mean | 57.06 | 2.09 | 0.24 | 0.63 | - | 14.85 | 25.30 | 100.16 |

| Buoyant hydrothermal plume of the Troll Wall | ||||||||

| 7 | 66.78 | 1.70 | 0.40 | n.d. | n.d. | 14.41 | 16.71 | 100.00 |

| 8 | 50.10 | 1.41 | 0.49 | n.d. | n.d. | 13.87 | 30.67 | 96.54 |

| 9 | 41.49 | 5.32 | 1.30 | n.d. | n.d. | 15.89 | 35.25 | 99.25 |

| Mean | 52.79 | 2.81 | 0.73 | - | - | 14.72 | 27.54 | 98.59 |

| Hydrothermally altered sediments of the Loki’s Castel | ||||||||

| 10 | 61.63 | 0.5 | 0.16 | 0.36 | n.d. | 14.66 | 35.85 | 113.16 |

| 11 | 60.18 | n.d. | 0.12 | 0.19 | 0.06 | 13.05 | 31.15 | 104.70 |

| 12 | 59.68 | 1.24 | 0.11 | 0.11 | n.d. | 13.89 | 35.49 | 110.52 |

| 13 | 51.31 | 1.22 | 0.05 | 2.16 | n.d. | 13.09 | 41.53 | 109.36 |

| 14 | 63.36 | 0.59 | 0.05 | 0.16 | 0.28 | 13.86 | 29.26 | 107.55 |

| 15 | 54.07 | 0.10 | n.d. | 0.13 | 0.17 | 12.38 | 35.97 | 102.74 |

| 16 | 57.76 | 0.94 | 0.10 | 0.29 | n.d. | 13.25 | 30.20 | 102.53 |

| Mean | 58.28 | 0.66 | 0.10 | 0.49 | 0.17 | 13.45 | 34.21 | 107.22 |

| Buoyant hydrothermal plume of the Loki’s Castel | ||||||||

| 17 | 43.06 | 5.07 | 1.54 | n.d. | 0.04 | 13.37 | 35.88 | 98.95 |

| Vent field | Location | Depth, m | Deposit type | Fluid salinity, wt.% NaCl eq. |

Fluid T*, °С |

Comment | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Troll Wall | 71º18' N, Mohns Ridge, AMOR | 550 | Chimney edifices | n.d.** | 260–270 | Direct measurements. | [32] |

| 512–600 | Hydrothermally altered sediments | n.d. | 130–290 | Sphalerite geothermometry, Kullerud’s method. | [74] | ||

| 512–600 | Hydrothermally altered sediments | 2.6–4.4 | 119–276 | Primary and secondary FIs in barite. Fluid phase separation indicated. | This work | ||

| Bruce |

71º18' N, Mohns Ridge, AMOR | 561 | Barite-rich chimney edifices | ~2.6 | 240–242 | Direct measurements: maximum temperature. Fluid phase separation indicated. | [56] |

| 560 | Barite-rich chimney edifices | ~2.5 | 229–270 | Direct measurements. Fluid phase separation indicated. | [81] | ||

| Perle & Bruce | 71º18' N, Mohns Ridge, AMOR | 620 | Hydrothermally altered sediments | 3.1–4.2 | 139–273 | Primary and primary–secondary FIs in barite. Fluid phase separation indicated. | This work |

| Soria Moria | 71º15' N, Mohns Ridge, AMOR | ~700 | Chimney edifices | ~3.1 | 50–270 | Direct measurements. | [81] |

| Loki’s Castle | 73°30' N, Mohns Ridge, AMOR | ~2,000 | Talc–anhydrite chimney edifices | ~2.9 | 280–317 | Direct measurements. Fluid phase separation indicated. | [33] |

| 2376 | Hydrothermally altered sediments | 2.8–4.4 | 223–307 | Primary and secondary FIs in barite. Fluid phase separation indicated. | This work | ||

| Fåvne | 72º45′ N, Mohns Ridge, AMOR | ~3,000 | Seafloor massive sulfide | 4.2–8.0 | 200–291 | Primary FIs in anhydrite. Fluid did not experience significant mixing with seawater. | [37] |

| Menez Gwen | 37°50′N, MAR, influenced by the Azores hot spot | 847–871 | Anhydrite and Anhydrite-barite edifices with disseminated sulfides | 2.2–2.3 | 271–284 | Direct measurements. Fluid phase separation indicated. | [22] |

| Lucky Strike | 37º N, MAR, influenced by the Azores hot spot | 1618–1730 | Sulfate–sulfide deposits | 2.9–3.5 | 202–325 | Direct measurements. Evidence for fluid phase separation. | [72] |

| Rainbow | 36° 14' N and 33°54' W, MAR | 2270–2320 | Sulfide edifices, field associated with serpentinites | 4.5–7.7 | 295–370 | Primary FIs in anhydrite associated with marcasite and chalcopyrite. Fluid phase separation proposed. | [82] |

| Broken Spur | 29° 10' N, 43º 10' W, MAR | ~3000 | Sulfide chimney, walls of a tube | 3.0–6.3 | 259–406 | Primary FIs in anhydrite. Fluid phase separation indicated. | [79] |

| TAG, Trans-Atlantic Geotraverse | 26° 08′ N, MAR | 3670 | Volcanogenic massive sulfides, edifices | 1.2–5.1 | 187–390 | Primary FIs in anhydrite. Fluid phase separation indicated. | [91] |

| Breccia, veins, quartz, massive granular pyrite | 1.9–6.2 | 212–390 | Primary FIs in anhydrite and quartz. Fluid phase separation indicated. | [92] | |||

| Logachev-1 | 14° 45' N, MAR | 2970 | Sulfide chimney, walls of a tube | 4.2–16.2 (max 26) |

271–365 | Primary FIs in anhydrite. Fluid phase separation indicated. | [79] |

| 1.9–6.2 | 212–390 | Primary FIs in anhydrite and quartz. Fluid phase separation indicated. | [92] | ||||

| Semenov-1 | 13°30′ N, MAR | 2,400–2,950 | Barite-rich massive sulfides | 0.6–3.8 | 83–244 | Primary FIs in barite. Fluid phase separation indicated. | [25] |

| Ashadze 1, Long Chimney |

12° 58' N, MAR | 4080 | Sulfide edifices | 5.0–7.0 | 295–345 | Primary FIs in anhydrite. Fluid phase separation indicated. | [93] |

| Embryo sulfide edifices | 5.0–7.8 | 235–355 | Primary FIs in anhydrite. Fluid phase separation indicated. | [93] | |||

| JADE | Central Okinawa Trough, N–W Pacific. Back-arc basin. | 1300–1600 | Sulfide-sulfate chimneys and mounds. Stockwork mineralizations. | 4.4–9.6 | 220–320 | Primary FIs in gypsum and barite. | [94] |

| 2.0–15.0 | 270–360 | Primary FIs in sphalerite. Fluid phase separation indicated. | [11] | ||||

| Endeavour Segment | Juan de Fuca Ridge, N–E Pacific | 2050–2700 | Barite-rich sulfide edifices | 5.7–9.4 | 124–283 | Primary FIs in barite. Fluid phase separation is not confirmed. | [18] |

| Vienna Wood | 3° 10' S, 150º 17' E, Manus basin, S–W Pacific | ~2500 | Barite–silica–sulfide chimney, top of an active tube | 4.7–7.6 | 165–235 | Primary and secondary FIs in barite. Fluid phase separation indicated. | [79] |

| 5.3–7.2 | 242–324 | Primary FIs in anhydrite. Fluid phase separation indicated. | [79] | ||||

| 4.1–8.5 | 160–247 | Primary FIs in anhydrite associated with chalcopyrite and sphalerite. Fluid phase separation proposed. | [82] | ||||

| Franklin seamount | 9° 55' S, 151º 50' E, Woodlark basin, S–W Pacific | 2143–2366 | Barite–sulfide edifices | 2.7–6.9 | 203–316 | Primary FIs in barite. Fluid phase separation indicated. | [79] |

| Lau back arc basin | 19º20'–22º50' S, Valu Fa Ridge, Tonga arc, S–W Pasific | 1735 | White Church, barite–sulfide chimneys | 1.6–2.6 | 170–230 | Primary FIs in barite. Fluid phase separation indicated. | [23] |

| Hook Ridge | 62º 11’ S, 57º 15’ W, Bransfield Strait, Antarctica | 990 | Chimney and massive barite slab. Arc-shaped composite volcano | 0.9–4.2 | 132–310 | Primary FIs in barite. Fluid phase separation indicated. | [83] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).