1. Introduction

Mining is finite, yet the consequences of mining may be enduring if they are not addressed with the necessary diligence. Furthermore, the extracted material may have adverse environmental consequences, too, which is the case when coal is used as a fuel. Together this makes coal mining unattractive form a wider society point of view and consequently many scientists and policy makers consider a (global) termination of coal mining. Consequently, even if coal mining is economically successful in some cases, a termination of the operation will occur, rather sooner than later due to the adverse environmental impacts. One important aspect of coalmine closure is mine water management.

During operation, mine water is pumped which drains the groundwater of the entire region up until the deepest depth of the mine, leaving shallower extraction levels above the water table. In the period of their abandonment, mine water drainage systems are no longer required, pumping is stopped, and consequently the mine water will rise until it reaches natural or a planned level. Typical questions arising in this context are related to the duration of mine water level rebound, the flow volumes and geochemical composition of mine water at decant points. From the analysis of 97 closed underground and open cut coal mines in Europe Gombert et al. 2019 [

1] conclude that the quantitative influence of coal mine water discharges is “substantial” and that “evaluating their environmental impact on surface and underground water is important”. Currently approximately 1600 active coalmines exist worldwide, whereby more than 50 % of these are underground operations [

2]. According to “Forum Bergbau Wasser” [

3], around 92 million cubic meters of mine water are pumped each year at the two largest mine sites in Germany alone. Therefore, the importance to know the potential contaminant sources and to understand the transport processes involved in order to mitigate the environmental impact caused by mine water is underlined.

This article focusses on mine water management and the mobilization, transport and discharge of contaminants contained in waste materials, deposited in underground coalmines. Within the Ruhr area, which is used as a case study in this article, diligent planning of mine water level rise has prevented adverse effects on the environment. Indeed, the quality of surface waters has significantly increased over the last decades. In order to achieve this goal detailed knowledge is required on

the quantity and type of wastes in underground coal mines

the extent of underground workings and connections between mines

the transport mechanisms of various types of contaminants

the use of specialized mine water modelling software as prediction tool.

2. Underground Mining in Ruhr Area

To shed light on the processes and prediction methods of contaminant transport during mine water rebound the underground mining region of the Ruhr area constitutes an exceptionally well documented example. The Ruhr area is located in western Germany and consists of several cities (see

Figure 1). Approximately 5,05 million inhabitants live in the Ruhr Area, which has a surface extent of 4.436 km

2, resulting in ~1.140 inhabitants/km

2 making it one of the most densely populated regions in Germany.

The former coal mining area is huge comprising dozens of neighboring and interconnected underground coalmines, where mining was performed for centuries. Coal mine closure and associated mine water rebound in the Ruhr area is a continuous and ongoing task. The last two coalmines in the Ruhr Area closed in 2018. Today the main water management challenge is to prevent the contact of the mine water with near surface ground water, which is used as drinking water resource. Another important aspect is the discharge of drained mine water into receiving waters (rivers) and therefore predicting mine water and surface water chemistry development.

In order to continuously reduce these unacceptable effects a mine water management concept was developed by the former coalmine operator, the RAG, in 2014 (see [

13] ). This initial concept is under constant review by the responsible mining authorities and, in addition, is being constantly optimized in order to reduce environmental effects caused by e.g. CO

2 emissions from ongoing mine water pumping.

As previously pointed out, the main wave of closures of the coal mines in the Ruhr area began in the 1960s. Due to close proximity of underground mines and hydraulic interconnectivity through roadways, water management had to be maintained in closed underground mine workings, to prevent water intrusion into neighboring (active) mines. As a result, the Ruhr Area has been subdivided into several so called water management provinces, with central water pumping stations. In 1969, for example, 25 drainage systems were used to drain mine water and protect the active mines [

18]. In the following years, as coalmine closure continued, the number of drainage systems was decreased/optimized. The current water management plan for the Ruhr Area [

13] envisages to use only six drainage installations for the entire Ruhr area (see

Figure 2 and

Table 2). The planning phase of this ambitious goal required extensive water rebound modelling and prediction.

2. Case study: Water Management in the Central Water Province of the Ruhr area - Germany

From a regulatory point of view, the discontinuation of mining and associated water management requires approval from authorities. In order to obtain approval, closure management plans need to be prepared, which require extensive documentation on all activities involved to close the mine. This includes most notably also water management activities. In order to assess the effects of mine water level rebound in the so called central water province of the Ruhr area from -1300 amsl to -630 amsl a feasibility study was prepared in 2020 by RAG [

19], prior to the actual closure management plan, which received approval from the authorities in 2021. For the feasibility study the Boxmodel was used to investigate and predict several aspects of the planned mine water level rise including substance mobilization, transport and discharge. The results of these investigations with regard to underground wastes are presented here.

The central water province has a surface extend of 1.155 km

2 (see

Figure 3 and

Figure 4). The province consists of a large number of mines, which operated in the last decades and were successively merged into larger units (see

Table 2). The Boxmodel distinguishes 82 sub-units (boxes), which are shown in

Figure 3. The boxes represent former individual mines with homogenous properties and interconnections. After the end of active coal mining in the last Prosper-Haniel mine still in operation in the region (by the end of 2018), water pumping was stopped there (2021) and in the Auguste Victoria mine to the north (May 2019). After that, there was also the option of stopping the Zollverein, Carolinenglück and Amalie dewatering systems and allowing the mine water level to rise over a large area.

2.1. Simulation of Mine Water Rebound and Hydraulic Situation

As already explained the plan is to install a central pumping station at the Lohberg sub province, which is capable of controlling the mine water level within the entire central water province. According to the water management concept, mine water level at Lohberg sub province will be kept at -630 masl. Fig. shows the catchment area of the planned system with the sub-provinces delineated in color.

Figure 5.

Water levels and the water flow directions in the central water province after stop of pumping in 2022/2023.

Figure 5.

Water levels and the water flow directions in the central water province after stop of pumping in 2022/2023.

In Fig. the water level and main flow paths in the central water province directly after cessation of the last 4 pumping stations in the south is shown. In the beginning of 2023 the plans of the feasibility study were implemented and these pumping stations in Zollverein, Carolinenglück and Amalie were stopped. Now the water level rises in these sub provinces but due to short time span the water levels show more or less still the last pumping levels, i.e. that they have since increased only in the range of 10 to 50 meters. In Fig. the predicted time dependent water level rise is presented. The current hydraulic situation is characterized by different water levels in the different boxes. In most of the sub provinces the water level currently is in rising phase with different rising speed. This is due to the different dewatering termination times and the distinct excavation / void volumes in the mining areas. In addition, naturally occurring inflow rates are variable, which are mainly concentrated in the southern area. The model is calibrated by using historic mine water level and pumping rate monitoring data for each individual mine.

Figure 6.

Simulated (solid lines) and monitoring data (symbols) of the pumping rate and water levels (dashed lines) in the central water province. Note that between 2022 and 2030 water pumping out was stopped.

Figure 6.

Simulated (solid lines) and monitoring data (symbols) of the pumping rate and water levels (dashed lines) in the central water province. Note that between 2022 and 2030 water pumping out was stopped.

Figure 7.

Predicted water levels and the water flow directions in the central water province in final situation.

Figure 7.

Predicted water levels and the water flow directions in the central water province in final situation.

Fig. shows the predicted water levels in the central water province with the preferential water flow directions (blue arrows) after installation of the Lohberg pumping station. It is expected that at -600 m additional pump is needed to transfer water from ZV-Stinnesdam to Lohberg. Following this initial prediction of the mine water rise it must be investigated if the rising of water level can cause unacceptable effects such as water contamination. Even if in this case the mine water level is kept below sensitive groundwater bodies, this question of quality is of fundamental importance for the discharge of the mine water into the receiving water. Thus, simulation of mine water rising and predicting of water quality and potentially contaminants is of crucial importance.

6.2. Simulation of Solute Transport

The water composition in coal mining regions is mainly influenced by the chemical composition of the inflow waters, pyrite oxidation, and water mixing with mineral precipitation and sedimentation as well as microbial activities such as sulfate reducing bacteria. All these processes are considered in the Boxmodel. The model takes various processes into account to describe the mass transport: solute transport as dissolved aquatic species, and colloidal transport for non-dissolved components (PCB transport). Typical developments in mine water are explained below using a few important components, the behavior of which can serve as a representative of the various groups of substances in mine water. This is shown for the substance developments that were determined in the last water drainage systems in the Lohberg water province, in order to illustrate both the variability of the inflows and the model calibration and the forecast based on it.

As a highly soluble component representing the total salinity of mine water, chloride is a suitable parameter for understanding flow and water mixing processes, which is hardly subject to chemical precipitation reactions and thus behave like a tracer. The time dependent chloride concentration in the central water province is shown in Fig.

Results reveal a high salinity in the central deep Emschermulde (Zollverein Stinnesdamm) with a Cl concentration of ~57 g/L and a low salinity in the south (Water Overflow Amalie (WO Amalie), Cl ≃ 2g/L), where, however, high flow rates exist. After the water rise in the central water province mixing of inflow waters result in a mine water with about 20 g/L chloride. Highly saline mine water from the northern AV/Lippe sub province also contributes to the mixture (WO AV), whose calibration dates are not shown here.

There is no clear evidence for a relevant mobilization of chloride during water rise, as one might assume from the dissolution of the salt deposits in drifts. Probably these amounts are too small compared to the total amounts in the mine water. Therefore, chloride mobilization is not considered in the model and all the chloride discharged comes from the various inflows of the mine water. This also applies for numerous other salts such as ammonium, boron, sodium, potassium, etc., whose content is usually also closely correlated with chloride.

Figure 8.

Simulated (lines) and monitoring data (symbols) of chloride concentration in the central water province.

Figure 8.

Simulated (lines) and monitoring data (symbols) of chloride concentration in the central water province.

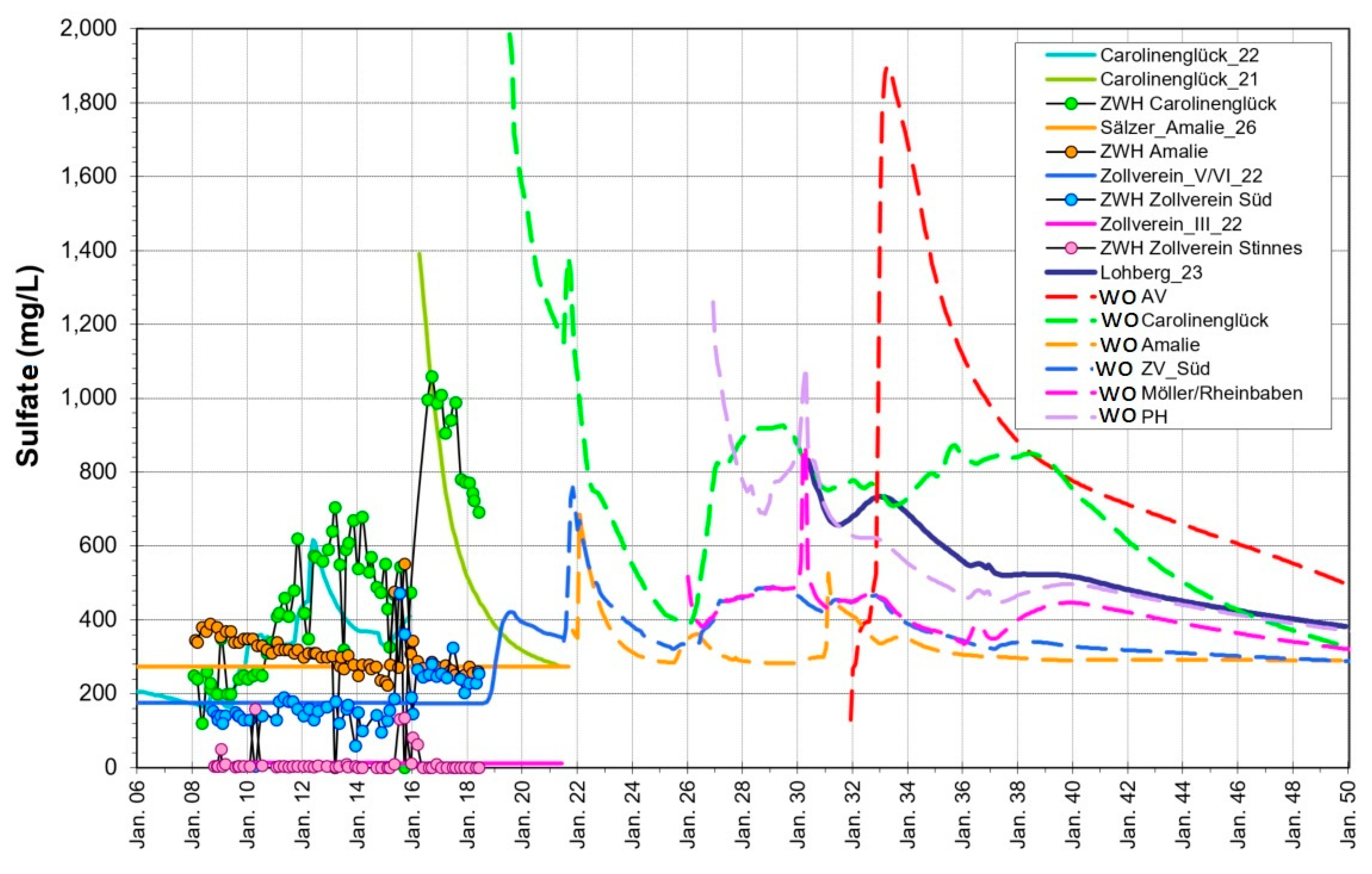

In order to study the contaminants mobilization and transport, the development of sulfate in the mine water plays a major role, since the mobilization of sulfate from pyrite oxidation in the water rise has a crucial effect here. Sulfur, as the main component of pyrite (FeS

2), is especially affected by the oxidation process and the subsequent dissolution of the resulting salts and appears as sulfate in the mine water. In Fig. the concentrations of sulfate in the central water province are presented. Sulfate concentrations show clear peaks after flooding, then decrease exponentially due to exchange of mine water in the post water-rising phase.

Figure 9 shows that the highest SO

4 contents appears in the south part (WÜ Carolinenglück with a concentration of ~2 g/L). This is due to the seepage waters from the surface in which a higher amount of pyrite oxidation has happened. In contrast, low concentration of sulfate are observed in the central Emschermulde (Zollverein, SO

4 < 50 mg/L). This is because of a high content of barium in the deep inflows and consequently precipitation of barite and decrease of sulfate in the mine water. Barium is a constituent of saline waters, accompanied by radium in a very constant ratio. Barium sulfate precipitates quite rapidly when a water containing-barium mixes with sulfate-containing waters. Barium can also serve as an indicator of radioactive contamination by radium 226 and radium 228, which are also present in the precipitated barium sulfate due to correlated co-precipitation of radium. Conversely, sulfate-containing waters in the south are barium-free. The overall balance after water rising is a sulfate-containing barium-free mine water with no treatment requirements for barium/radium.

Figure 9.

Simulated (lines) and monitoring data (symbols) of sulfate concentration in the central water province.

Figure 9.

Simulated (lines) and monitoring data (symbols) of sulfate concentration in the central water province.

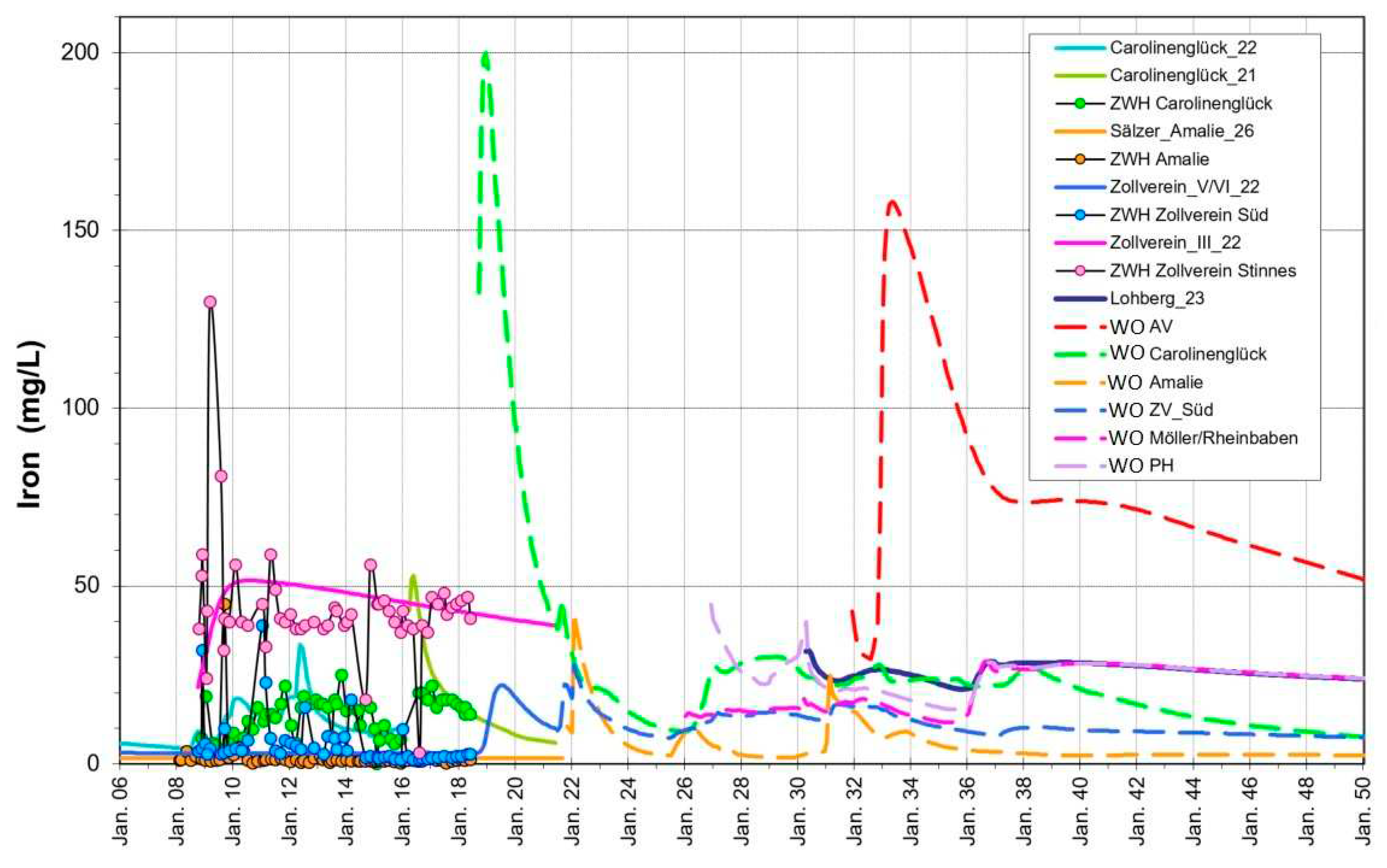

As the second main component of the pyrite oxidization, iron is mobilized in the water rise. This process is analogous to sulfate and can preferably be recognized in the Carolinenglück and AV/Lippe province (

Figure 10). In principle, however, it can be assumed that iron mobilization is a universal process. On the basis of iron it is found that the flushing of the substances present in the mine water after the water rise in the deep Emschermulde is very slow (the inflowing water contains in the mixture 13 mg/L). A large volume of impounded water is replaced from small inflow rate quantities here. The Carolinenglück province reacts disproportionately more dynamically to hydraulic changes. The highest primary iron concentrations come from the Auguste Victoria mine. In addition, due to the mineralization, high material inputs are also to be expected from this area in the future. In the overall mixture, iron levels of between 20 and 40 mg/l can be expected upon discharge. The extent to which this is compatible with the limit values in the receiving river Rhine must be the subject of corresponding investigations.

Figure 10.

Simulated (lines) and monitoring data (symbols) of iron concentration in the central water province.

Figure 10.

Simulated (lines) and monitoring data (symbols) of iron concentration in the central water province.

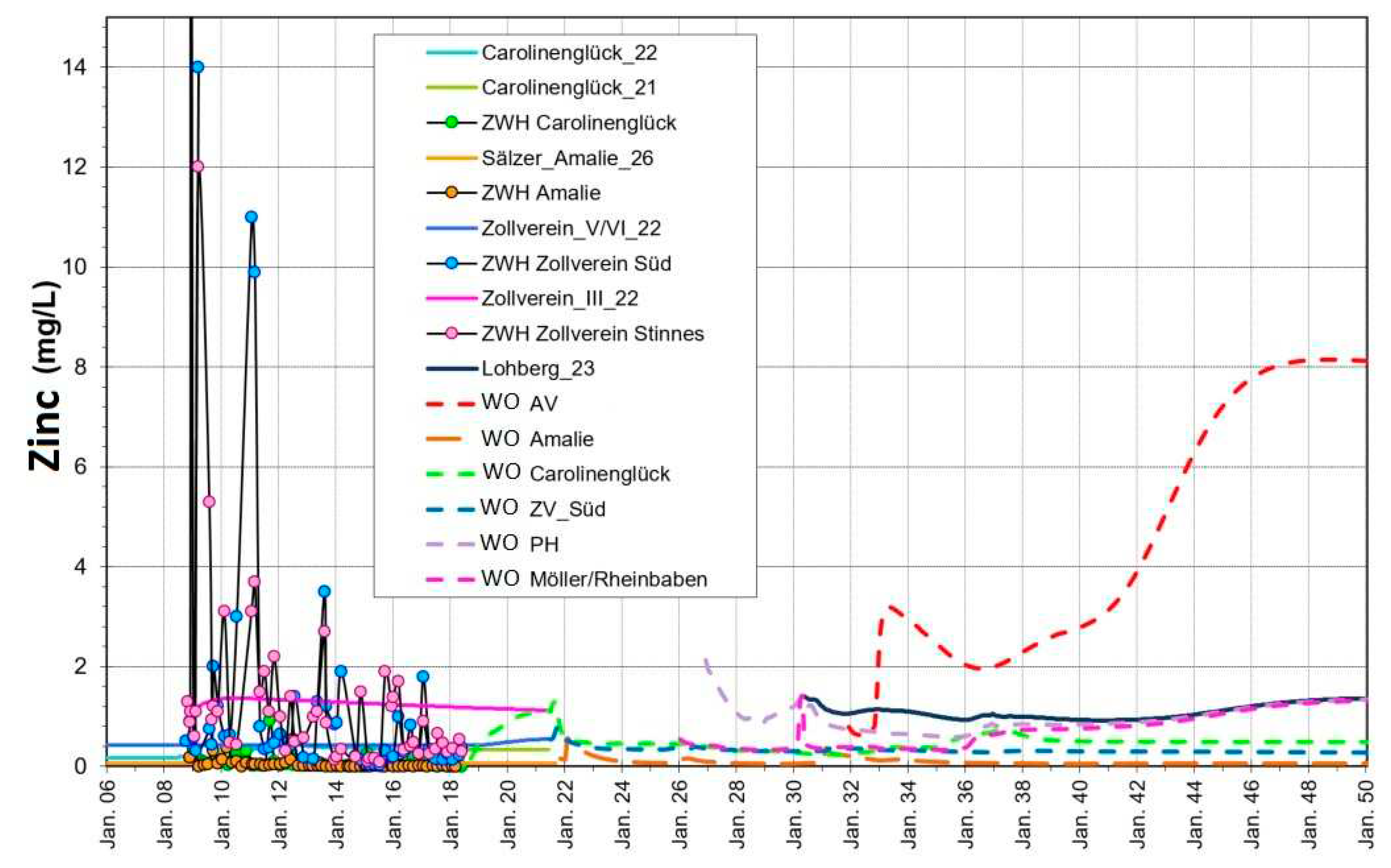

Metal contamination in the mine water is the most severe problem and has been reported in many mining regions worldwide. Zinc is one of the most abundantly found metals in contaminated mine waters. Zinc contents in the central water province fluctuate frequently as can be seen in

Figure 11. A mobilization analogous to iron from pyrite oxidation can be assumed for zinc in the water rise. Observations imply that, in addition to zinc, nickel and copper are also mobilized from pyrite or as a result of pyrite oxidation. At the Auguste Victoria mine (WÜ AV) the pH value is lower compared to the other provinces, mainly due to the inflows from the previously mined mineralization zone and its subsequent flooding. This is expected to result locally in an unusual high concentration of zinc. However, this zinc hot spot influences the water quality of the entire area and represents the greatest impact for future discharge.

Figure 11.

Simulated (lines) and monitoring data (symbols) of zinc concentration in the central water province.

Figure 11.

Simulated (lines) and monitoring data (symbols) of zinc concentration in the central water province.

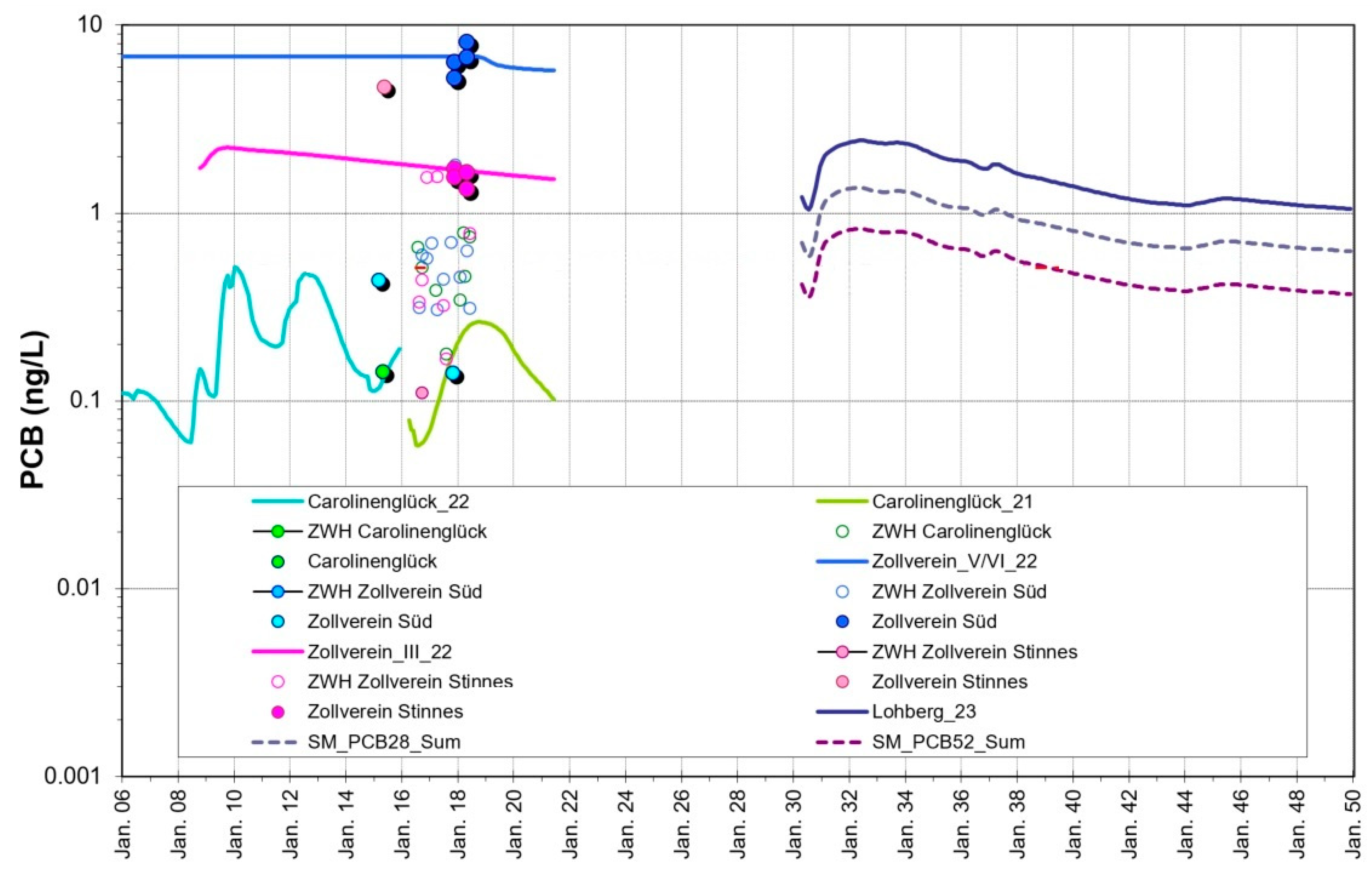

6.3. Simulation of PCB Transport

Like other high-molecular organic compounds, PCB has a very low solubility in water and a high tendency to bind to particle surfaces, therefore it can be transported in a high content on particles [

17]. Numerous investigations have shown that this is also the case in mine water. The Boxmodel was therefore upgraded for the particulate transport of PCBs, but would in principle also be able to take dissolved PCBs into account. According to this modelling approach, PCB levels in mine water are essentially a result of the suspended matter content in the water and the PCB concentration of this suspended matter [

4]. In contrast to soluble species, the solid particles are eroded in turbulent water flow and accumulated again at low flow velocities.

The concentrations calculated from inflows, water flow in the mine and finally the rebound mine water are influenced by the mining conditions and the corresponding inputs of the different particle types:

Particles containing PCB, whose mobilization and transport behavior are considered in the model.

PCB-free particles, which are also taken into account with fractions in the model.

The relationship between the two particle types results from the area ratio of the respective mining elevation (PCB use (1964-1991) or PCB free) in the various hydraulically connected levels.

The model calculates a mixture of the particle contents transported by the inflows during the water rebound and mobilized by additional erosion. In general, the reduction in the particle content after flooding by diminution of turbulent flow and increased laminar flow in now the water-filled galleries leads to a significant decrease in PCB concentration [

23].

Fig. shows the PCB concentration in the central water province. Results show a wide spread in PCB contents of the mine waters in the sub-provinzes. This is due to the spatial heterogeneity in the remained PCB in underground mines from the mining activity period.

In standard analysis 7 PCB-congeners are determined as representative indicator compounds which are also considered as separate substances in the Boxmodel. The chemical properties of the different PCB congeners depend on the chlorine content [

19]. Due to the nature of the PCB-containing liquids used in mining, besides the sum of the 7 congeners the PCB-28 and PCB-52 as main components are of particular importance. The analytically determined particle levels of a few mg/L and PCB levels in the solid of several 100 mg/kg result in particle-bound concentrations of a few ng/L, which nevertheless can represent a relevant load when discharged into the receiving water, especially immediately after pumping has started.

Figure 12.

Simulated (lines) and monitoring data (symbols) of PCB content of the particulate solid in the central water province of Ruhr area.

Figure 12.

Simulated (lines) and monitoring data (symbols) of PCB content of the particulate solid in the central water province of Ruhr area.

6.4. Monitoring and Water Treatment

In general the qualitative and quantitative monitoring data of inflows and pumped mine water is an essential tool for model calibration and predicting a long-term mine water drainage. This made it obvious that mine water contains various contaminants or even natural components that can become a pollutant when discharged into a surface water. For this reason, the question of a possible water treatment must always be considered in planning for a water rise and subsequent dewatering.

In result of the water rise due to stopping the water-pumps, the monitoring water quality through regular sampling of this water is inapplicable. During the mine water rise the hydraulic situation is changing, and depending on the distribution of inflow rates and the fillable residual void volume, the flow conditions in the mine change constantly until activation of a new pumping level and/or location are re-established. In order to obtain knowledge about the condition of the mine water outside the remaining water elevation points under these conditions, extensive monitoring is already being carried out by RAG in shafts that have access to the mine water. In addition to measuring water levels, this also includes taking and analyzing water samples. This is necessary in order to know a possible need for water treatment in general or to determine its urgency and extent.

The necessary access to the underground mine is provided by shafts and boreholes. Mine water samples must meet several conditions to allow a representative conclusion on the underground conditions. The basic requirement is that the sample be taken outside the guide pipe in which the sampling vessel is lowered. The sampler must therefore enter the free shaft and be opened there at a defined level. This location must also be chosen in such a way that its position in the flow is known on the one hand and that it also represents a relevant mine water flow.

Based on the monitoring data and the results of the calibrated models, the requirements of suitable mine water treatment plants will be evaluated. Depending on the situation, different goals are relevant. These include the metal- or sulfate-containing waters described in Chapter 5.2, but also PCB, radioactivity or the salinity of the water.

In the past, mine water treatment in the German hard coal mining industry was only carried out to a limited extent and in some cases underground. One exception is the Ibbenbüren site, where acidic water with a high metal content has been treated for many decades. Mine water drainage in the past also benefited from the fact that large parts of the mine water were discharged into the Emscher river, which had been converted into a wastewater canal. Now that the Emscher has been re-naturalized, the hurdles for the discharge of mine water have increased. Limits for discharge of mine water into surface rivers are specified in the Federal Water Act and in the Surface Water Act, which have adapted the specifications of the Water Framework Directive. If these limits are exceeded in the future, water treatment for the pollutants contained in the mine water (whether from anthropogenic waste materials, substances mobilized from the rock by mining, or from natural sources) is a suitable option for environmentally safe discharge. The technology used, but also the targeted capture rates, must always take into account the usually high flow rates of the mine water, which in the case study described sum up to more than 45 m³.

For the following mine water components at different locations a requirement of treatment have been identified and the methods for reducing the concentration have been applied, tested, developed or examined:

- -

Iron and metals

- -

sulfate

- -

salts

- -

Barium/radium

- -

Hydrogen sulfide

- -

PCB

In principle, different methods are available to remove waste material contaminants from mine water. However, in some cases the effort is very high (e.g. desalination, sulfate, PCB) and aspects of proportionality have to be considered. In some cases, however, the necessary adaptation of the process to the conditions of the mine waters is still missing (e.g. PCB). Model prediction has proven to be the most important tool for the planning of such concepts, as only it can provide a basis for the expected substance contents. After all, planning, approval and construction of such a plant always require a lead time of several years.

2. Conclusion and Suggestions

Understanding the interaction of different types of waste materials in underground mines with rising mine water is of great environmental importance. Uncontrolled mine water level rebound may result in pollution of drinking water resources due to the mine water contact with wastes or natural substances that impair water quality. In coal mining from last centuries the use of flame resistant material PCB/PCDM together with the backfill materials are two major sources of anthropogenic wastes. In case the backfill material contains metals it must be ensured that these are not mobilized during flooding process, specifically when the pyrite oxidation has the potential to reduce the pH of the mine water. In addition, mineral oil products have been used for underground machine operation for many decades.

Simulation of hydrodynamics and hydrogeochemical processes occurring during the mine water rebound can reduce the risk of surface and ground water contamination and prevent environmental hazards. In this regard, the DMT Boxmodel has been developed and introduced, which predicts the effects of mine water level rise and the associated hydrogeochemical processes in a large complex underground mining area. It has been successfully applied in several mining regions in Germany and worldwide.

Modelling results provided by the Boxmodel for the central water province of Ruhr area predicted the mobilization and transport of contaminants in the mine water during and shortly after the mine water rebound. Intensive monitoring and controlling the water quality and quantity in inflows and mine water is an essential tool for model calibration and predicting a long-term mine water drainage. Based on the monitoring data and the results of the calibrated models, the requirements of suitable mine water treatment plants will be evaluated.

So far, the RAG and the RAG foundation have successfully undertaken substantial efforts to ensure drinking water quality. The use of contaminant transport modelling with the DMT Boxmodel has provided the baseline for successful water management.