Submitted:

28 June 2023

Posted:

29 June 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Results

3. Discussion

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Physical Measurements

4.2. Spectroscopic Determinations

4.3. Biological assays

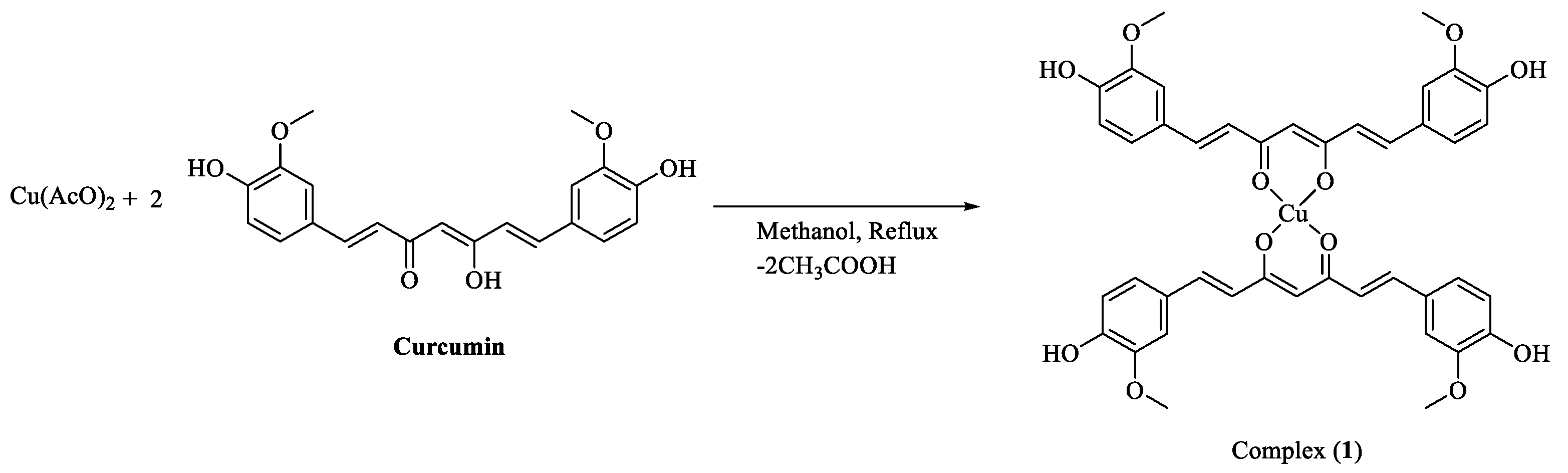

4.4. Synthesis of complex 1

4.5. X-ray Crystallography

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgements

Conflicts of Interest

Sample Availability

References

- Hewlings, S.J.; Kalman, D.S. Curcumin: A Review of Its Effects on Human Health. Foods 2017, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Prasad, S.; Dubourdieu, D.; Srivastava, A.; Kumar, P.; Lall, R. Metal–Curcumin Complexes in Therapeutics: An Approach to Enhance Pharmacological Effects of Curcumin. Int J Mol Sci 2021, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mishra, S.; Palanivelu, K. The Effect of Curcumin (Turmeric) on Alzheimer′s Disease: An Overview. Ann Indian Acad Neurol 2008, 11, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boarescu; Boarescu; Bocșan; Gheban; Bulboacă; Nicula; Pop; Râjnoveanu; Bolboacă Antioxidant and Anti-Inflammatory Effects of Curcumin Nanoparticles on Drug-Induced Acute Myocardial Infarction in Diabetic Rats. Antioxidants 2019, 8, 504. [CrossRef]

- Hussain, H.; Ahmad, S.; Shah, S.W.A.; Ullah, A.; Rahman, S.U.; Ahmad, M.; Almehmadi, M.; Abdulaziz, O.; Allahyani, M.; Alsaiari, A.A.; et al. Synthetic Mono-Carbonyl Curcumin Analogues Attenuate Oxidative Stress in Mouse Models. Biomedicines 2022, 10, 2597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Witika, B.A.; Makoni, P.A.; Matafwali, S.K.; Mweetwa, L.L.; Shandele, G.C.; Walker, R.B. Enhancement of Biological and Pharmacological Properties of an Encapsulated Polyphenol: Curcumin. Molecules 2021, 26, 4244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ghosh, S.; Banerjee, S.; Sil, P.C. The Beneficial Role of Curcumin on Inflammation, Diabetes and Neurodegenerative Disease: A Recent Update. Food and Chemical Toxicology 2015, 83, 111–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chauhan, G.; Rath, G.; Goyal, A.K. In-Vitro Anti-Viral Screening and Cytotoxicity Evaluation of Copper-Curcumin Complex. Artif Cells Nanomed Biotechnol 2013, 41, 276–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reddy, R.C.; Vatsala, P.G.; Keshamouni, V.G.; Padmanaban, G.; Rangarajan, P.N. Curcumin for Malaria Therapy. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 2005, 326, 472–474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mahady GB, P.S.Y.G.L.Z. Turmeric (Curcuma Longa) and Curcumin Inhibit the Growth of Helicobacter Pylori, a Group 1 Carcinogen. Anticancer Res 2002, 22, 4179–4181. [Google Scholar]

- Ghorbani, Z.; Hekmatdoost, A.; Mirmiran, P. Anti-Hyperglycemic and Insulin Sensitizer Effects of Turmeric and Its Principle Constituent Curcumin. Int J Endocrinol Metab 2014, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Quispe, C.; Herrera-Bravo, J.; Javed, Z.; Khan, K.; Raza, S.; Gulsunoglu-Konuskan, Z.; Daştan, S.D.; Sytar, O.; Martorell, M.; Sharifi-Rad, J.; et al. Therapeutic Applications of Curcumin in Diabetes: A Review and Perspective. Biomed Res Int 2022, 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lei, F.; Li, P.; Chen, T.; Wang, Q.; Wang, C.; Liu, Y.; Deng, Y.; Zhang, Z.; Xu, M.; Tian, J.; et al. Recent Advances in Curcumin-Loaded Biomimetic Nanomedicines for Targeted Therapies. J Drug Deliv Sci Technol 2023, 80, 104200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Waure, C.; Bertola, C.; Baccarini, G.; Chiavarini, M.; Mancuso, C. Exploring the Contribution of Curcumin to Cancer Therapy: A Systematic Review of Randomized Controlled Trials. Pharmaceutics 2023, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kong, W.-Y.; Ngai, S.C.; Goh, B.-H.; Lee, L.-H.; Htar, T.-T.; Chuah, L.-H. Is Curcumin the Answer to Future Chemotherapy Cocktail? Molecules 2021, 26, 4329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zoi, V.; Galani, V.; Lianos, G.D.; Voulgaris, S.; Kyritsis, A.P.; Alexiou, G.A. The Role of Curcumin in Cancer Treatment. Biomedicines 2021, 9, 1086. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jalili-Nik, M.; Soltani, A.; Moussavi, S.; Ghayour-Mobarhan, M.; Ferns, G.A.; Hassanian, S.M.; Avan, A. Current Status and Future Prospective of Curcumin as a Potential Therapeutic Agent in the Treatment of Colorectal Cancer. J Cell Physiol 2018, 233, 6337–6345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Devassy, J.G.; Nwachukwu, I.D.; Jones, P.J.H. Curcumin and Cancer: Barriers to Obtaining a Health Claim. Nutr Rev 2015, 73, 155–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ravindran, J.; Prasad, S.; Aggarwal, B.B. Curcumin and Cancer Cells: How Many Ways Can Curry Kill Tumor Cells Selectively? AAPS J 2009, 11, 495–510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Anand, P.; Kunnumakkara, A.B.; Newman, R.A.; Aggarwal, B.B. Bioavailability of Curcumin: Problems and Promises. Mol Pharm 2007, 4, 807–818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prasad, S.; Tyagi, A.K.; Aggarwal, B.B. Recent Developments in Delivery, Bioavailability, Absorption and Metabolism of Curcumin: The Golden Pigment from Golden Spice. Cancer Res Treat 2014, 46, 2–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sohn, S.-I.; Priya, A.; Balasubramaniam, B.; Muthuramalingam, P.; Sivasankar, C.; Selvaraj, A.; Valliammai, A.; Jothi, R.; Pandian, S. Biomedical Applications and Bioavailability of Curcumin—An Updated Overview. Pharmaceutics 2021, 13, 2102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, L.; Ji, H.-F. The Pharmacology of Curcumin: Is It the Degradation Products? Trends Mol Med 2012, 18, 138–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, J.; Wei, D.; Jiang, B.; Liu, T.; Ni, J.; Zhou, S. Two Copper(II) Complexes of Curcumin Derivatives: Synthesis, Crystal Structure and in Vitro Antitumor Activity. Transition Metal Chemistry 2014, 39, 553–558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Basile, V.; Ferrari, E.; Lazzari, S.; Belluti, S.; Pignedoli, F.; Imbriano, C. Curcumin Derivatives: Molecular Basis of Their Anti-Cancer Activity. Biochem Pharmacol 2009, 78, 1305–1315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Medigue, N.E.H.; Bouakouk-Chitti, Z.; Bechohra, L.L.; Kellou-Taïri, S. Theoretical Study of the Impact of Metal Complexation on the Reactivity Properties of Curcumin and Its Diacetylated Derivative as Antioxidant Agents. J Mol Model 2021, 27, 192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wanninger, S.; Lorenz, V.; Subhan, A.; Edelmann, F.T. Metal Complexes of Curcumin - Synthetic Strategies, Structures and Medicinal Applications. Chem Soc Rev 2015, 44, 4986–5002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barik, A.; Mishra, B.; Kunwar, A.; Kadam, R.M.; Shen, L.; Dutta, S.; Padhye, S.; Satpati, A.K.; Zhang, H.Y.; Indira Priyadarsini, K. Comparative Study of Copper(II)-Curcumin Complexes as Superoxide Dismutase Mimics and Free Radical Scavengers. Eur J Med Chem 2007, 42, 431–439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- H. M. Leung, M.; Harada, T.; W. Kee, T. Delivery of Curcumin and Medicinal Effects of the Copper(II)-Curcumin Complexes. Curr Pharm Des 2013, 19, 2070–2083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vajragupta, O. Manganese Complexes of Curcumin and Its Derivatives: Evaluation for the Radical Scavenging Ability and Neuroprotective Activity. Free Radic Biol Med 2003, 35, 1632–1644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khalil, M.I.; Al-Zahem, A.M.; Al-Qunaibit, M.H. Synthesis, Characterization, Mössbauer Parameters, and Antitumor Activity of Fe(III) Curcumin Complex. Bioinorg Chem Appl 2013, 2013, 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Al-Noor, T.H.; Ali, A.M.; Al-Sarray, A.J.A.; Al-Obaidi, O.H.; Obeidat, A.I.M.; Habash, R.R. A Short Review: Chemistry of Curcumin and Its Metal Complex Derivatives. 2022.

- Portolés-Gil, N.; Lanza, A.; Aliaga-Alcalde, N.; Ayllón, J.A.; Gemmi, M.; Mugnaioli, E.; López-Periago, A.M.; Domingo, C. Crystalline Curcumin BioMOF Obtained by Precipitation in Supercritical CO2 and Structural Determination by Electron Diffraction Tomography. ACS Sustain Chem Eng 2018, 6, 12309–12319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, H.; Sun, F.; Jia, J.; He, H.; Wang, A.; Zhu, G. A Highly Porous Medical Metal–Organic Framework Constructed from Bioactive Curcumin. Chemical Communications 2015, 51, 5774–5777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wazir, S.M.; Ghobrial, I. Copper Deficiency, a New Triad: Anemia, Leucopenia, and Myeloneuropathy. J Community Hosp Intern Med Perspect 2017, 7, 265–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sierpinska, T.; Konstantynowicz, J.; Orywal, K.; Golebiewska, M.; Szmitkowski, M. Copper Deficit as a Potential Pathogenic Factor of Reduced Bone Mineral Density and Severe Tooth Wear. Osteoporosis International 2014, 25, 447–454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Percival, S. Copper and Immunity. Am J Clin Nutr 1998, 67, 1064S–1068S. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Collins, J.F.; Klevay, L.M. Copper. Advances in Nutrition 2011, 2, 520–522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Desai, V.; Kaler, S.G. Role of Copper in Human Neurological Disorders. Am J Clin Nutr 2008, 88, 855S–858S. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, G.; Wang, J.; Liu, T.; Wang, M.; Zhou, S.; Wu, B.; Jiang, M. Synthesis and Crystal Structure of a Novel Copper(II) Complex of Curcumin-Type and Its Application in in Vitro and in Vivo Imaging. J Mater Chem B 2014, 2, 3659–3666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pi, Z.; Wang, J.; Jiang, B.; Cheng, G.; Zhou, S. A Curcumin-Based TPA Four-Branched Copper(II) Complex Probe for in Vivo Early Tumor Detection. Materials Science and Engineering C 2015, 46, 565–571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, W.; Chen, C.; Shi, H.; Yang, M.; Liu, Y.; Ji, P.; Chen, H.; Tan, R.X.; Li, E. Curcumin Is a Biologically Active Copper Chelator with Antitumor Activity. Phytomedicine 2016, 23, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Angulo, J.; Delgado-Villanueva, J. Preparación y Caracterización de Complejos de Curcumina Con Zinc(II), Níquel(II), Magnesio(II), Cobre(II) y Su Evaluación Frente a Bacterias Grampositiva y Gramnegativa. Revista Politécnica 2023, 51, 63–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, H.; He, H.; Tian, Y.; Zhao, N.; Sun, F.; Zhang, X.; Jiang, Q.; Zhu, G. Syntheses and Characterizations of Two Curcumin-Based Cocrystals. Inorg Chem Commun 2015, 55, 92–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matlinska, M.A.; Wasylishen, R.E.; Bernard, G.M.; Terskikh, V. V.; Brinkmann, A.; Michaelis, V.K. Capturing Elusive Polymorphs of Curcumin: A Structural Characterization and Computational Study. Cryst Growth Des 2018, 18, 5556–5563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McKinnon, J.J.; Jayatilaka, D.; Spackman, M.A. Towards Quantitative Analysis of Intermolecular Interactions with Hirshfeld Surfaces. Chemical Communications 2007, 3814–3816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Spackman, M.A.; McKinnon, J.J. Fingerprinting Intermolecular Interactions in Molecular Crystals. CrystEngComm 2002, 4, 378–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allen, F.H. The Cambridge Structural Database: A Quarter of a Million Crystal Structures and Rising. Acta Crystallogr B 2002, 58, 380–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Caruso, F.; Rossi, M.; Benson, A.; Opazo, C.; Freedman, D.; Monti, E.; Gariboldi, M.B.; Shaulky, J.; Marchetti, F.; Pettinari, R.; et al. Ruthenium-Arene Complexes of Curcumin: X-Ray and Density Functional Theory Structure, Synthesis, and Spectroscopic Characterization, in Vitro Antitumor Activity, and DNA Docking Studies of (p-Cymene)Ru(Curcuminato)Chloro. J Med Chem 2012, 55, 1072–1081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pettinari, R.; Marchetti, F.; Di Nicola, C.; Pettinari, C.; Cuccioloni, M.; Bonfili, L.; Eleuteri, A.M.; Therrien, B.; Batchelor, L.K.; Dyson, P.J. Novel Osmium( <scp>ii</Scp> )–Cymene Complexes Containing Curcumin and Bisdemethoxycurcumin Ligands. Inorg Chem Front 2019, 6, 2448–2457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pettinari, R.; Petrini, A.; Marchetti, F.; Di Nicola, C.; Scopelliti, R.; Riedel, T.; Pittet, L.D.; Galindo, A.; Dyson. , P.J. Influence of Functionalized η 6 -Arene Rings on Ruthenium(II) Curcuminoids Complexes. ChemistrySelect 2018, 3, 6696–6700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- da Silva, B.A.; Pitasse-Santos, P.; Sueth-Santiago, V.; Monteiro, A.R.M.; Marra, R.K.F.; Guedes, G.P.; Ribeiro, R.R.; de Lima, M.E.F.; Decoté-Ricardo, D.; Neves, A.P. Effects of Cu(II) and Zn(II) Coordination on the Trypanocidal Activities of Curcuminoid-Based Ligands. Inorganica Chim Acta 2020, 501, 119237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hussain, A.; Somyajit, K.; Banik, B.; Banerjee, S.; Nagaraju, G.; Chakravarty, A.R. Enhancing the Photocytotoxic Potential of Curcumin on Terpyridyl Lanthanide( <scp>iii</Scp> ) Complex Formation. Dalton Trans. 2013, 42, 182–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Banerjee, S.; Prasad, P.; Hussain, A.; Khan, I.; Kondaiah, P.; Chakravarty, A.R. Remarkable Photocytotoxicity of Curcumin in HeLa Cells in Visible Light and Arresting Its Degradation on Oxovanadium(Iv) Complex Formation. Chemical Communications 2012, 48, 7702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Halevas, E.; Pekou, A.; Papi, R.; Mavroidi, B.; Hatzidimitriou, A.G.; Zahariou, G.; Litsardakis, G.; Sagnou, M.; Pelecanou, M.; Pantazaki, A.A. Synthesis, Physicochemical Characterization and Biological Properties of Two Novel Cu(II) Complexes Based on Natural Products Curcumin and Quercetin. J Inorg Biochem 2020, 208, 111083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Triantis, C.; Tsotakos, T.; Tsoukalas, C.; Sagnou, M.; Raptopoulou, C.; Terzis, A.; Psycharis, V.; Pelecanou, M.; Pirmettis, I.; Papadopoulos, M. Synthesis and Characterization of Fac -[M(CO) 3 (P)(OO)] and Cis-Trans -[M(CO) 2 (P) 2 (OO)] Complexes (M = Re, 99m Tc) with Acetylacetone and Curcumin as OO Donor Bidentate Ligands. Inorg Chem 2013, 52, 12995–13003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

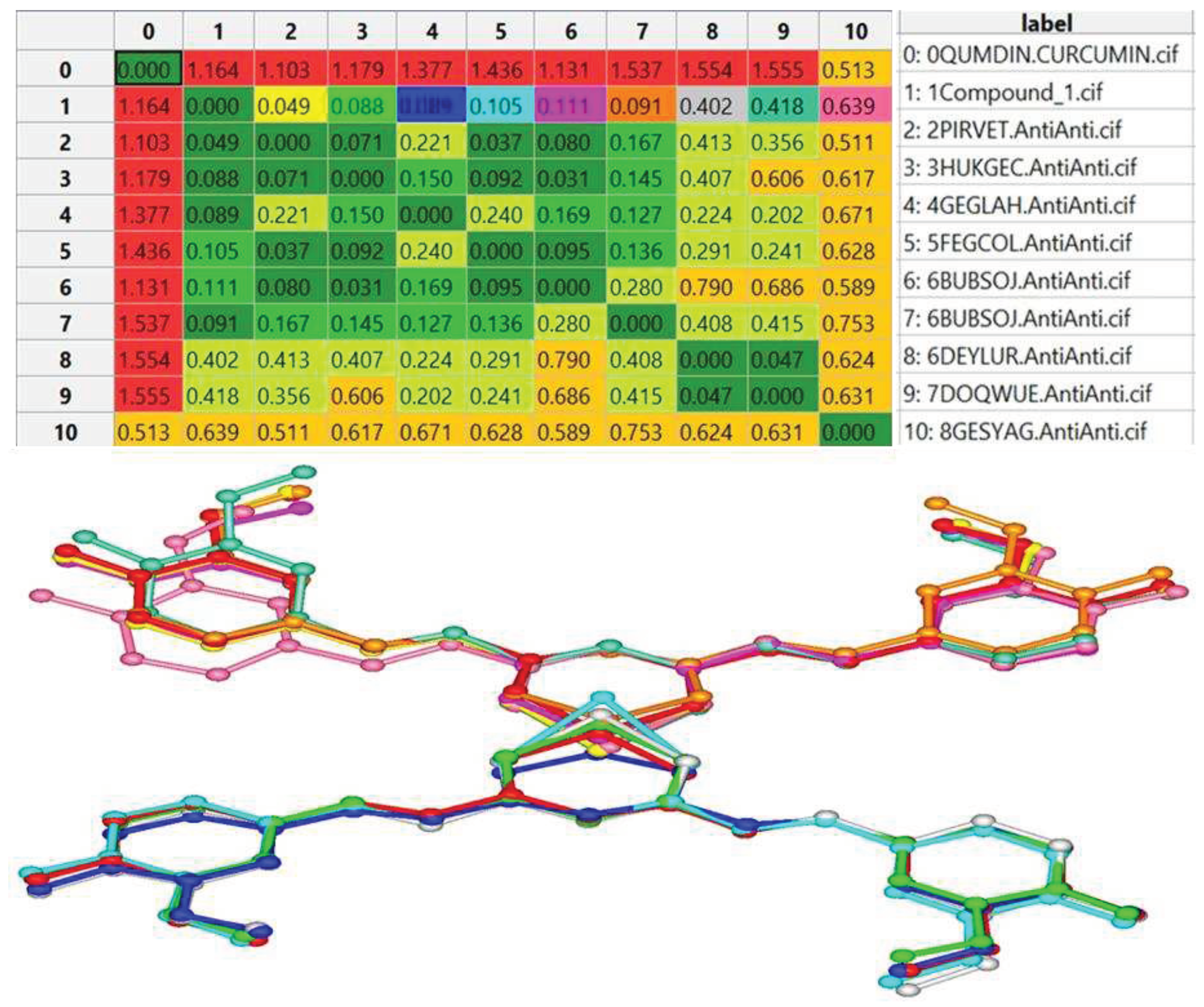

- Rohlíček, J.; Skořepová, E.; Babor, M.; Čejka, J. CrystalCMP : An Easy-to-Use Tool for Fast Comparison of Molecular Packing. J Appl Crystallogr 2016, 49, 2172–2183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, F.-S.; Sun, J.-L.; Xie, W.-H.; Shen, L.; Ji, H.-F. Neuroprotective Effects and Mechanisms of Curcumin–Cu(II) and –Zn(II) Complexes Systems and Their Pharmacological Implications. Nutrients 2017, 10, 28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zebib, B.; Mouloungui, Z.; Noirot, V. Stabilization of Curcumin by Complexation with Divalent Cations in Glycerol/Water System. Bioinorg Chem Appl 2010, 2010, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khorasani, M.Y.; Langari, H.; Sany, S.B.T.; Rezayi, M.; Sahebkar, A. The Role of Curcumin and Its Derivatives in Sensory Applications. Materials Science and Engineering: C 2019, 103, 109792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shakeri, A.; Panahi, Y.; Johnston, T.P.; Sahebkar, A. Biological Properties of Metal Complexes of Curcumin. BioFactors 2019, 45, 304–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shahabadi, N.; Falsafi, M.; Moghadam, N.H. DNA Interaction Studies of a Novel Cu(II) Complex as an Intercalator Containing Curcumin and Bathophenanthroline Ligands. J Photochem Photobiol B 2013, 122, 45–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meza-Morales, W.; Alvarez-Ricardo, Y.; Obregón-Mendoza, M.A.; Arenaza-Corona, A.; Ramírez-Apan, M.T.; Toscano, R.A.; Poveda-Jaramillo, J.C.; Enríquez, R.G. Three New Coordination Geometries of Homoleptic Zn Complexes of Curcuminoids and Their High Antiproliferative Potential. RSC Adv 2023, 13, 8577–8585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- S. , Priya.R.; S., Balachandran.; Daisy, Joseph.; V., Mohanan.P. Reactive Centers of Curcumin and the Possible Role of Metal Complexes of Curcumin as Antioxidants. Universal Journal of Physics and Application 2015, 9, 6–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jakubczyk, K.; Drużga, A.; Katarzyna, J.; Skonieczna-żydecka, K. Antioxidant Potential of Curcumin—a Meta-Analysis of Randomized Clinical Trials. Antioxidants 2020, 9, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Obregón-Mendoza, M.A.; Meza-Morales, W.; Alvarez-Ricardo, Y.; Estévez-Carmona, M.M.; Enríquez, R.G. High Yield Synthesis of Curcumin and Symmetric Curcuminoids: A “Click” and “Unclick” Chemistry Approach. Molecules 2022, 28, 289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ng, T.B.; L. F.; W.Z.T. Antioxidative Activity of Natural Products from Plants. Life Sci 2000, 66, 709–723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meza-Morales, W.; Alejo-Osorio, Y.; Alvarez-Ricardo, Y.; Obregón-Mendoza, M.A.; Machado-Rodriguez, J.C.; Arenaza-Corona, A.; Toscano, R.A.; Ramírez-Apan, M.T.; Enríquez, R.G. Homoleptic Complexes of Heterocyclic Curcuminoids with Mg(II) and Cu(II): First Conformationally Heteroleptic Case, Crystal Structures, and Biological Properties †. Molecules 2023, 28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ohkawa, H.; Ohishi, N.; Yagi, K. Assay for Lipid Peroxides in Animal Tissues by Thiobarbituric Acid Reaction. Anal Biochem 1979, 95, 351–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheldrick, G.M. SHELXT – Integrated Space-Group and Crystal-Structure Determination. Acta Crystallogr A Found Adv 2015, 71, 3–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sheldrick, G.M. Crystal Structure Refinement with SHELXL. Acta Crystallogr C Struct Chem 2015, 71, 3–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hübschle, C.B.; Sheldrick, G.M.; Dittrich, B. ShelXle : A Qt Graphical User Interface for SHELXL. J Appl Crystallogr 2011, 44, 1281–1284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

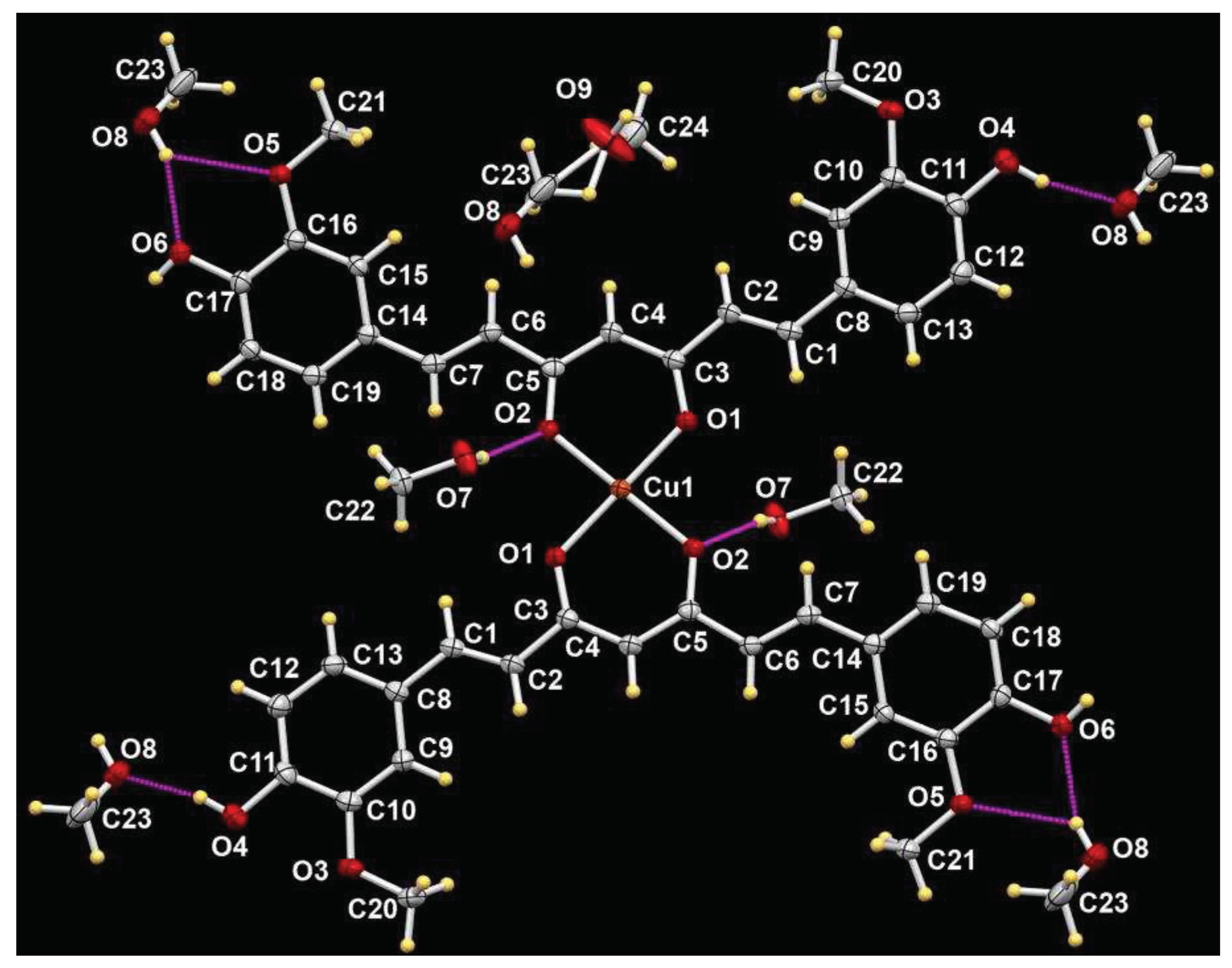

| Empirical formula | C42H38O12Cu·5MeOH |

|---|---|

| Formula weight | 958.47 |

| Temperature/K | 130(2) |

| Crystal system | triclinic |

| Space group | P-1 |

| a/Å | 8.3372(7) |

| b/Å | 8.7677(4) |

| c/Å | 16.3052(12) |

| α/° | 75.664(5) |

| β/° | 84.240(6) |

| γ/° | 84.636(5) |

| Volume/Å3 | 1146.02(14) |

| Z | 1 |

| σcalc g/cm3 | 1.389 |

| μ/mm-1 | 0.551 |

| F(000) | 505.0 |

| Crystal size/mm3 | 0.33 × 0.13 × 0.06 |

| Radiation | MoKα (λ = 0.71073) |

| 2Θ range for data collection/° | 6.852 to 59.284 |

| Index ranges | -11 ≤ h ≤ 11, -12 ≤ k ≤ 11, -22 ≤ l ≤ 22 |

| Reflections collected | 25565 |

| Independent reflections | 5848 [Rint = 0.0466, Rsigma = 0.0476] |

| Data/restraints/parameters | 5848/120/377 |

| Goodness-of-fit on F2 | 1.047 |

| Final R indexes [I>=2σ (I)] | R1 = 0.0498, wR2 = 0.1160 |

| Final R indexes [all data] | R1 = 0.0706, wR2 = 0.1293 |

| Bond | length | Bond | length |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cu(1)-O(1) | 1.9189(15) | C(3)-C(4) | 1.407(3) |

| Cu(1)-O(2) | 1.9191(14) | C(4)-C(5) | 1.389(3) |

| O(1)-C(3) | 1.280(2) | C(5)-C(6) | 1.469(3) |

| O(2)-C(5) | 1.292(2) | C(6)-C(7) | 1.344(3) |

| C(1)-C(2) | 1.340(3) | C(7)-C(14) | 1.457(3) |

| C(1)-C(8) | 1.458(3) | ||

| C(2)-C(3) | 1.466(3) | ||

| Bonds | Angle | Bonds | Angle |

| O(1)-Cu(1)-O(2)#1 | 85.99(6) | C(1)-C(2)-C(3)-O(1) | -10.6(3) |

| O(1)-Cu(1)-O(2) | 94.01(6) | C(1)-C(2)-C(3)-C(4) | 169.6(2) |

| C(2)-C(1)-C(8) | 126.4(2) | O(1)-C(3)-C(4)-C(5) | 7.7(4) |

| C(1)-C(2)-C(3) | 123.3(2) | C(2)-C(3)-C(4)-C(5) | -172.5(2) |

| O(1)-C(3)-C(4) | 124.7(2) | Cu(1)-O(2)-C(5)-C(4) | -5.3(3) |

| O(1)-C(3)-C(2) | 118.2(2) | Cu(1)-O(2)-C(5)-C(6) | 175.8(1) |

| C(4)-C(3)-C(2) | 117.1(2) | C(3)-C(4)-C(5)-O(2) | 0.0(4) |

| C(5)-C(4)-C(3) | 125.2(2) | C(3)-C(4)-C(5)-C(6) | 178.9(2) |

| O(2)-C(5)-C(4) | 124.3(2) | O(2)-C(5)-C(6)-C(7) | -9.4(3) |

| O(2)-C(5)-C(6) | 117.0(2) | C(4)-C(5)-C(6)-C(7) | 171.6(2) |

| C(4)-C(5)-C(6) | 118.6(2) | C(5)-C(6)-C(7)-C(14) | 175.3(2) |

| C(7)-C(6)-C(5) | 122.2(2) | C(2)-C(1)-C(8)-C(9) | 8.5(3) |

| C(6)-C(7)-C(14) | 127.6(2) | C(6)-C(7)-C(14)-C(15) | -2.2(3) |

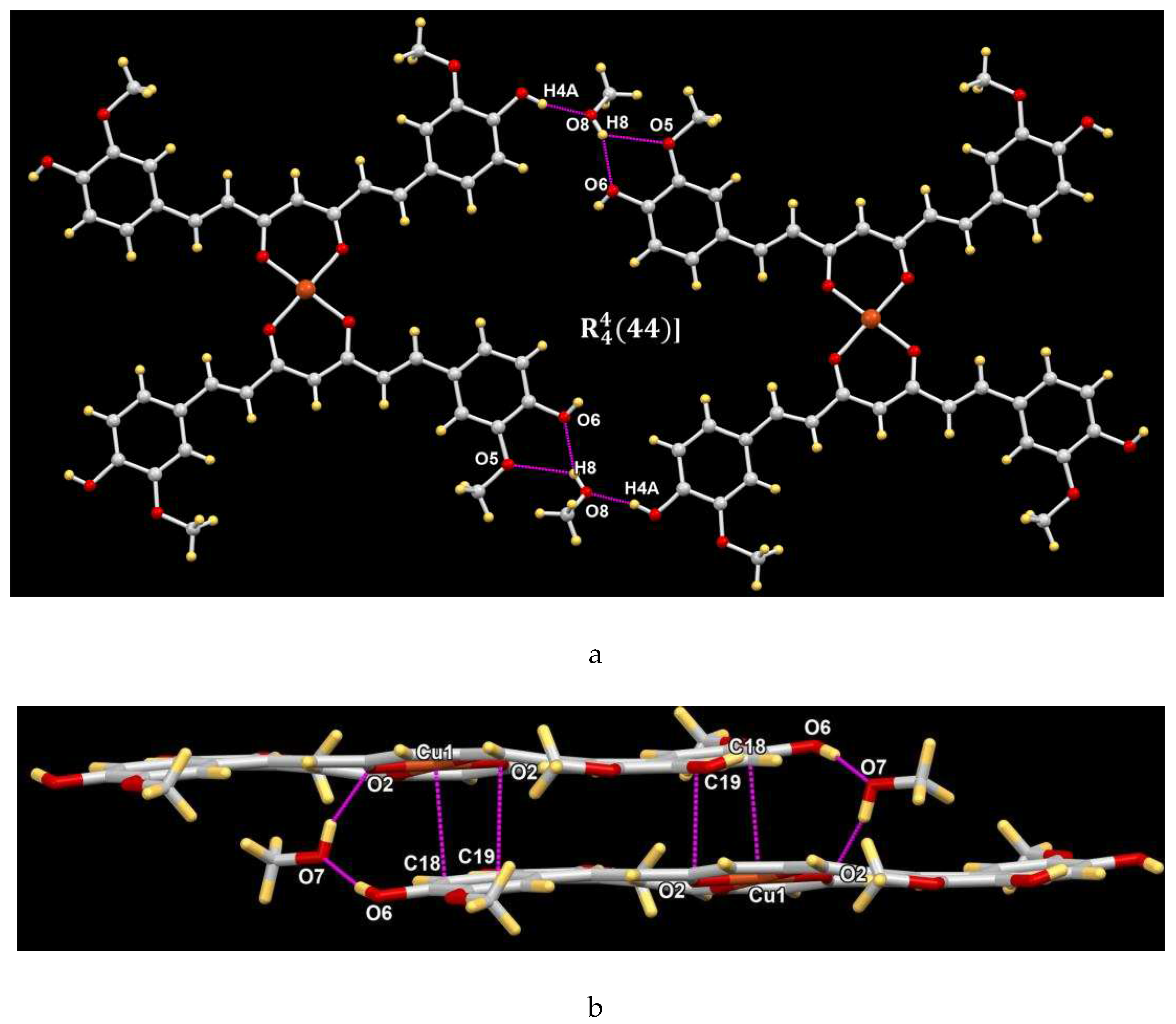

| D-H···A | d(D-H) | d(H···A) | d(D···A) | <(DHA) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| O(4)-H(4A)...O(8)#1 | 0.83 | 1.76 | 2.552(12) | 160.9 |

| O(4)-H(4A)...O(8B)#1 | 0.83 | 1.88 | 2.694(12) | 166.7 |

| O(6)-H(6A)...O(7)#2 | 0.76 | 2.02 | 2.767(12) | 170.1 |

| O(6)-H(6A)...O(7B)#2 | 0.76 | 1.82 | 2.574(10) | 174.9 |

| C(9)-H(9)...O(9B) | 0.95 | 2.52 | 3.431(9) | 161.0 |

| C(18)-H(18)...O(7)#2 | 0.95 | 2.53 | 3.197(12) | 127.4 |

| C(20)-H(20A)...O(9B) | 0.98 | 2.41 | 3.208(9) | 138.4 |

| C(21)-H(21A)...O(4)#3 | 0.98 | 2.64 | 3.580(3) | 161.1 |

| O(7)-H(7A)...O(2)#4 | 0.84 | 1.96 | 2.734(15) | 153.2 |

| O(8)-H(8)...O(5)#5 | 0.80 | 2.42 | 2.988(12) | 129.3 |

| O(8)-H(8)...O(6)#5 | 0.80 | 2.04 | 2.801(12) | 159.7 |

| C(23)-H(23C)...O(5)#6 | 0.98 | 2.46 | 3.129(10) | 125.1 |

| O(7B)-H(7B)...O(2)#4 | 0.84 | 1.99 | 2.786(14) | 158.5 |

| O(8B)-H(8B)...O(5)#5 | 0.84 | 2.39 | 3.070(11) | 138.5 |

| O(8B)-H(8B)...O(6)#5 | 0.84 | 2.11 | 2.861(11) | 148.8 |

| O(9)-H(9A)...O(4)#6 | 0.83 | 1.94 | 2.768(9) | 179.3 |

| C(24B)-H(24F)...O(4)#7 | 0.98 | 2.62 | 3.303(13) | 126.9 |

| Complex | U-251 (IC50 = mM) | K562 (IC50 = mM) |

|---|---|---|

| Complex (1) | 5.3±0.2 | 9.6±0.3 |

| Curcumin* | 20.5±1.7 | 16.4±0.04 |

| Complex | IC50 = μM) |

|---|---|

| Complex (1) | 1.26±0.08 |

| Curcumin | 3.03±0.15 |

| BHT | 1.22±0.44 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).