Submitted:

27 June 2023

Posted:

28 June 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Bacteria strains, synthetic biology tools and growth conditions

2.2. Microbial fuel cell design and operation

2.3. Electrochemical measurements

2.4. Coulombic Efficiency

2.5. Transformation of Pseudomonas sp. strains

2.6. Growth curves

2.7. Plasmid replication, and structural and segregational stability

2.8. Fluorescence protein (mCherry and GFPlva) expression in BJa5

2.8.1. Promoter activity as a function of genomic context

2.8.2. Quantification of promoter activity

2.9. Heterologous expression of an endoglucanase Cel5A

2.10. Genome sequencing

2.11. Taxonomic affiliation of Pseudomonas sp. BJa5

3. Results and Discussion

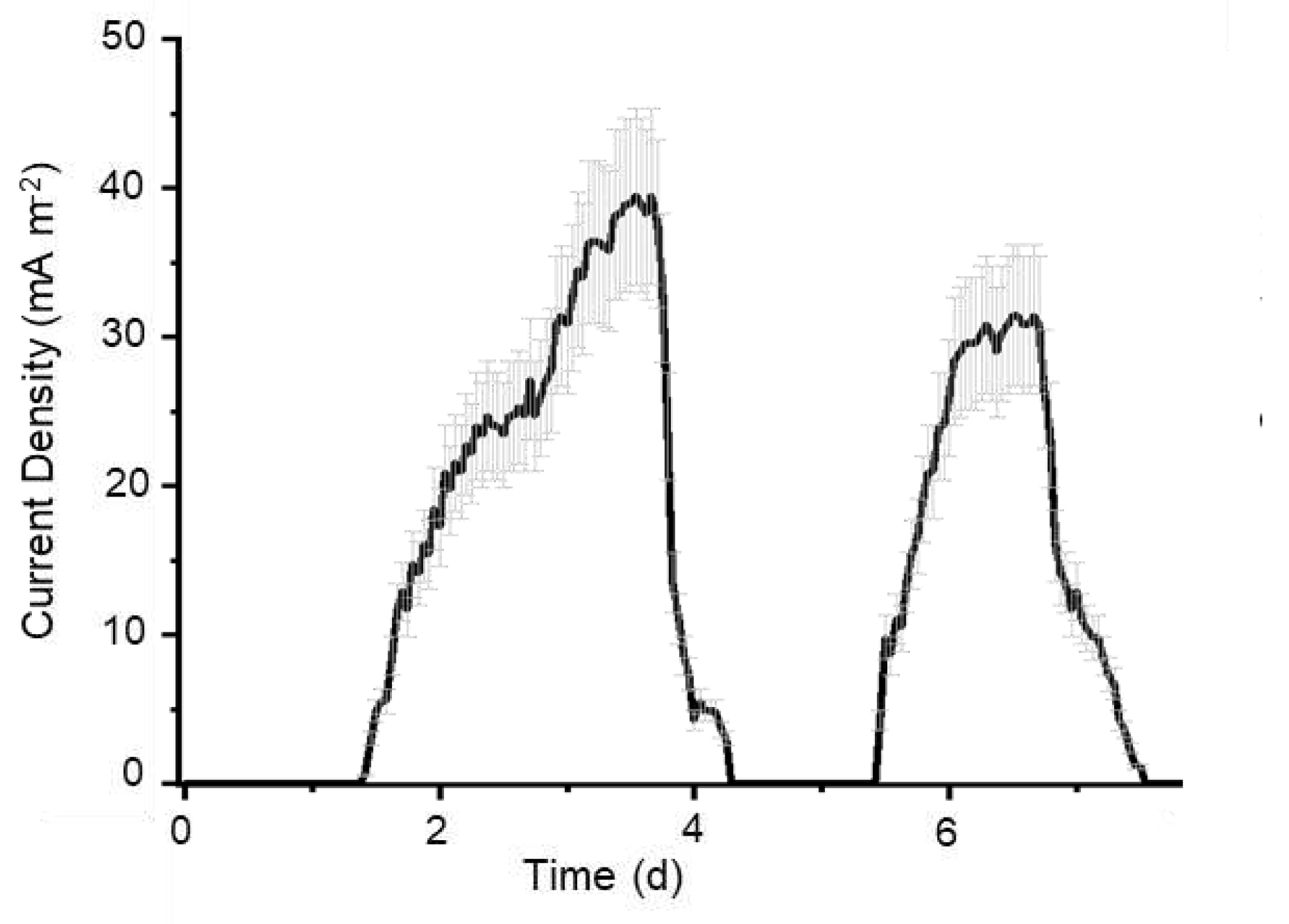

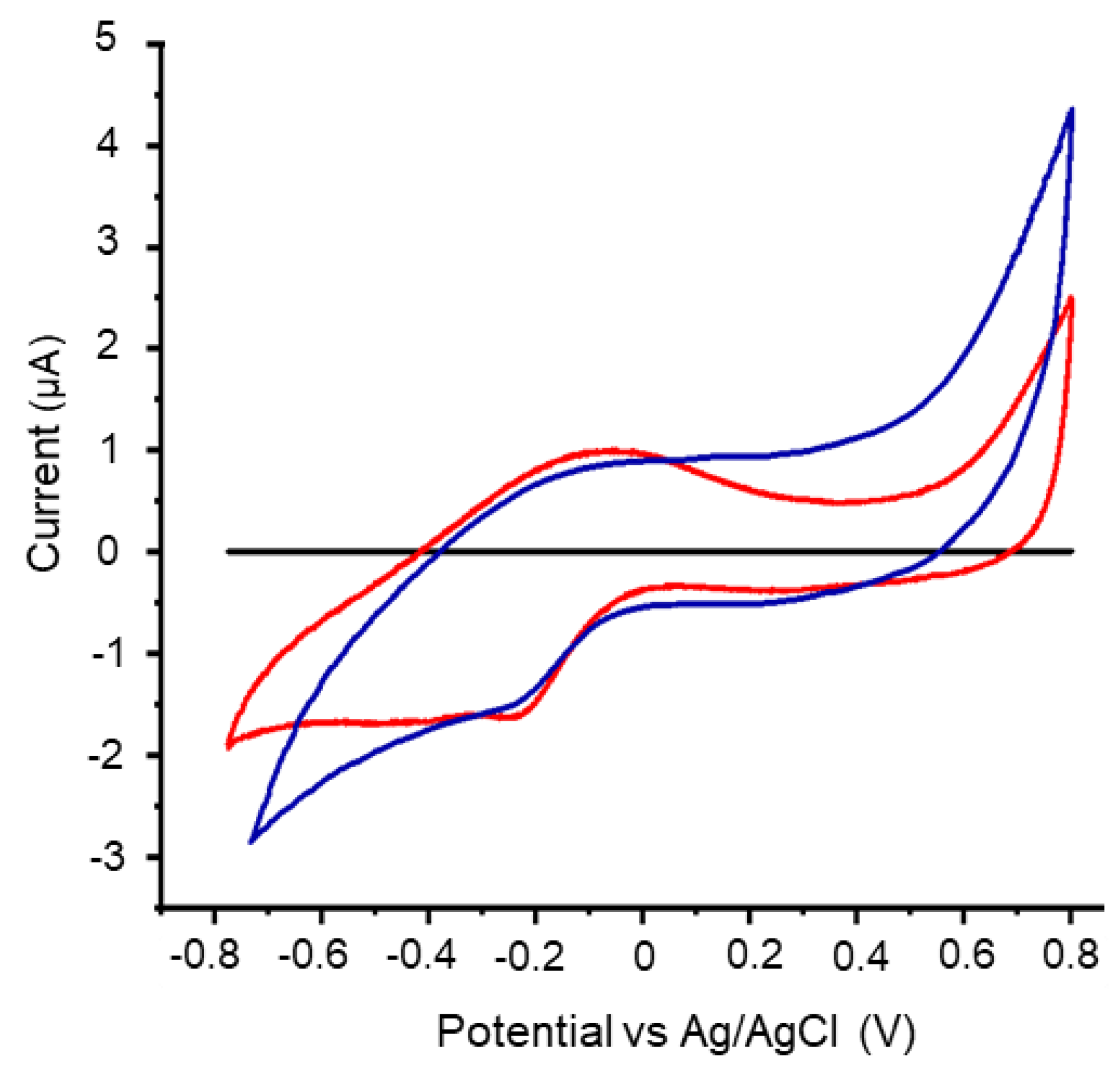

3.1. Production of bioelectricity and electrochemical activity of strain Bja5 is mediated by potential new redox molecules

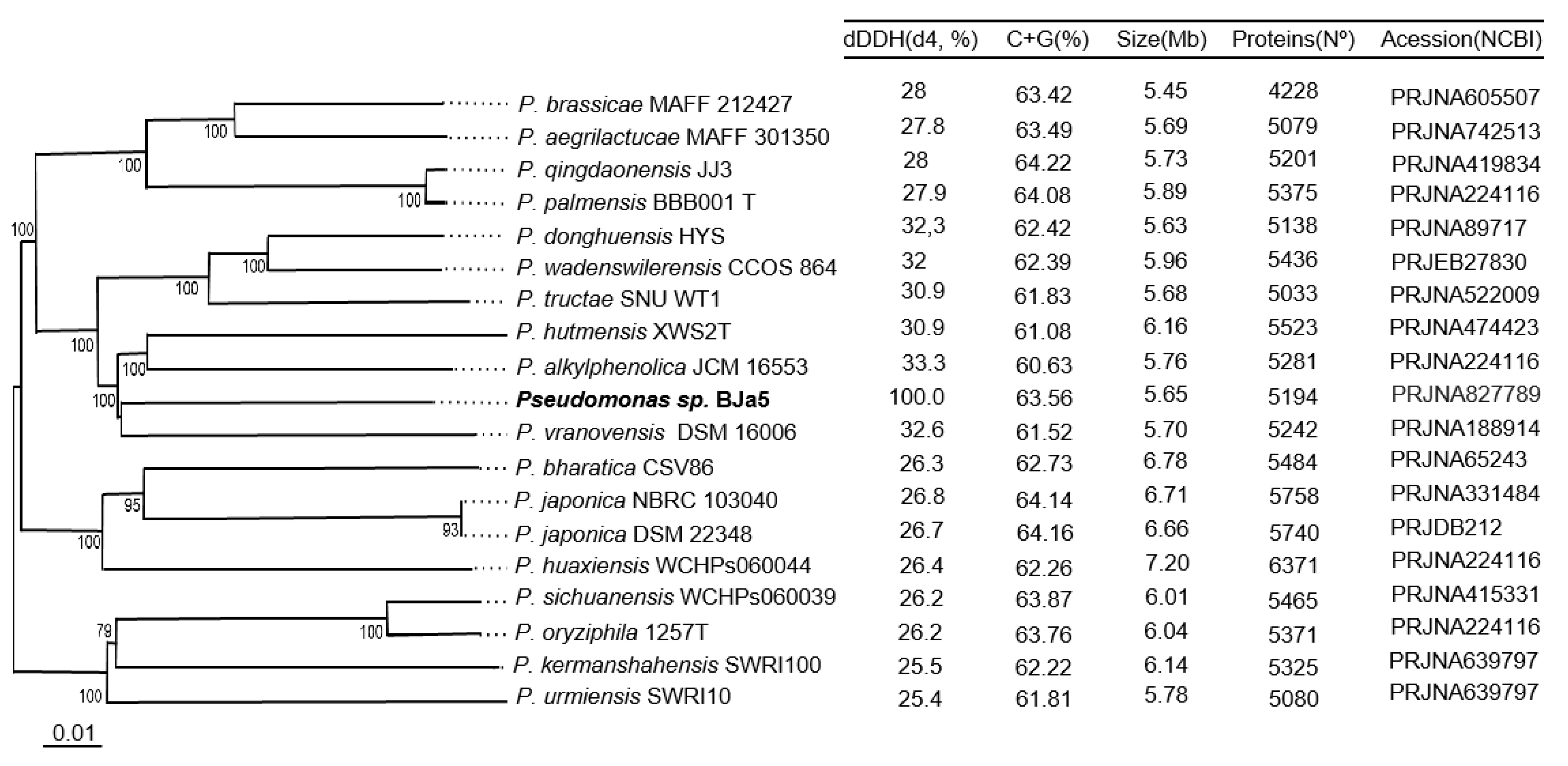

3.2. BJa5 strain is a potential new Pseudomonas species

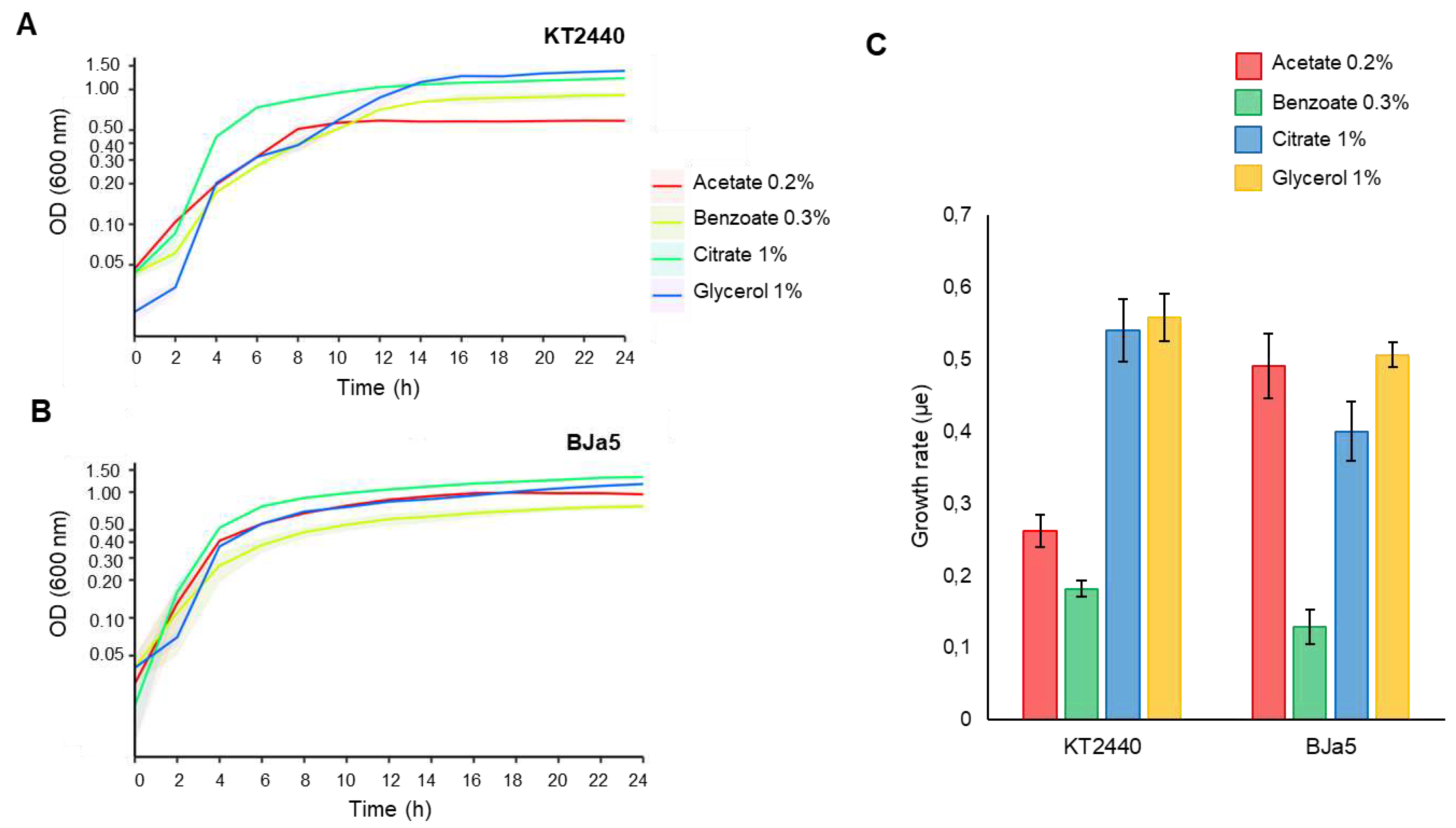

3.3. BJa5 can grow on different carbon sources of organic acids

3.4. Modular pSEVA plasmids are appropriate vectors for Pseudomonas sp. BJa5

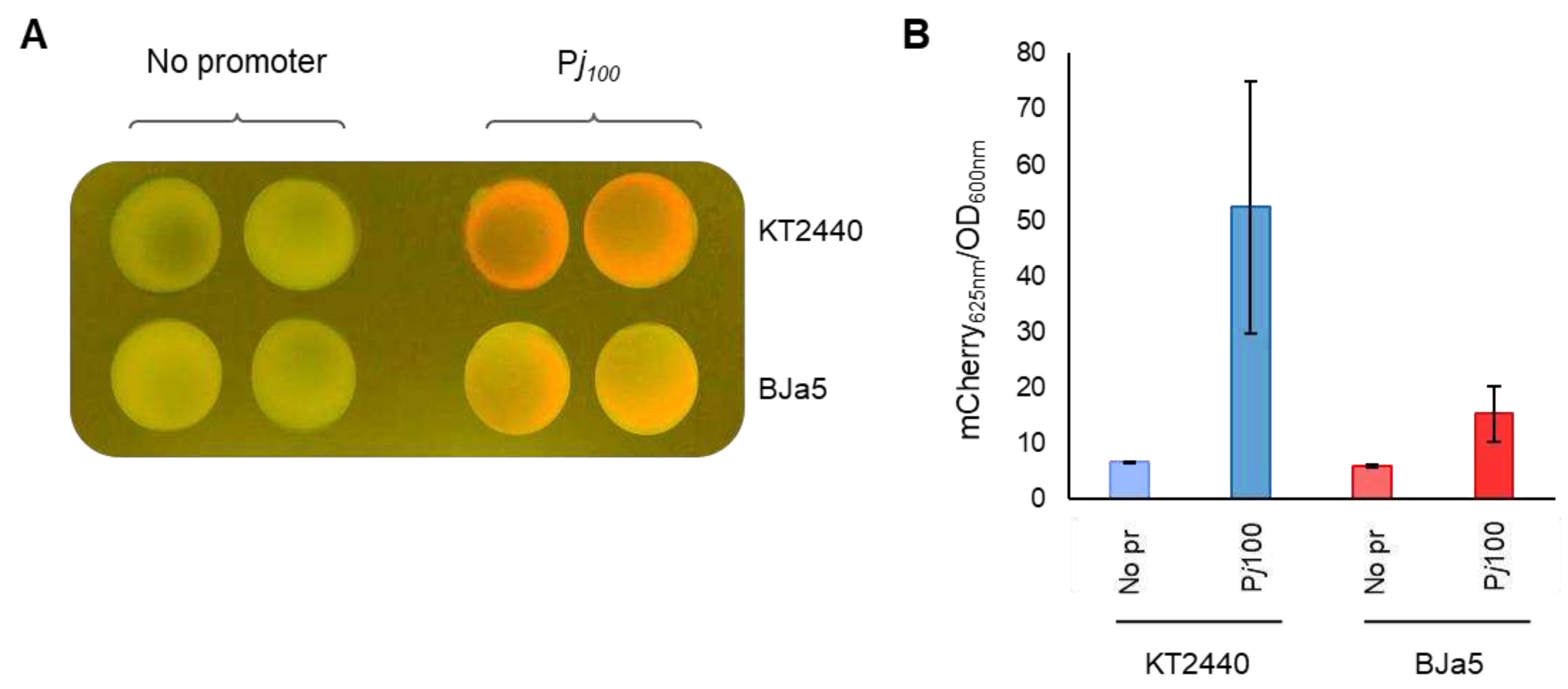

3.5. Pseudomonas sp. BJa5 recognizes the Pj100 canonical promoter

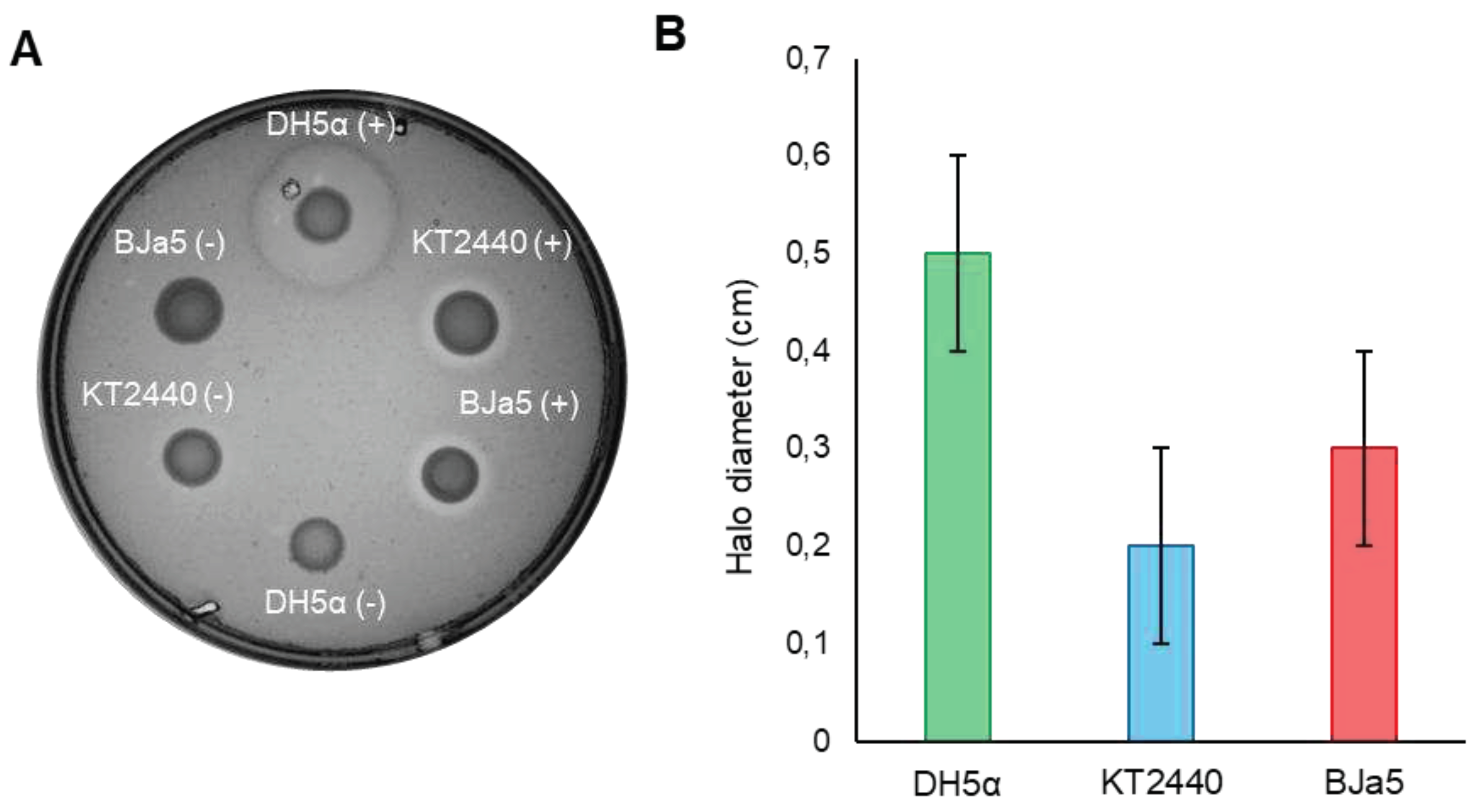

3.6. Pseudomonas sp. BJa5 strain expresses the heterologous enzyme Cel5A

4. Conclusion

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Tao, L.; Song, M.; Jiang, G. Enhanced Depolluting Capabilities of Microbial Bioelectrochemical Systems by Synthetic Biology. Synth. Syst. Biotechnol. 2023, 8, 341–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bajracharya, S.; Sharma, M.; Mohanakrishna, G.; Dominguez Benneton, X.; Strik, D.P.B.T.B.; Sarma, P.M.; Pant, D. An Overview on Emerging Bioelectrochemical Systems (BESs): Technology for Sustainable Electricity, Waste Remediation, Resource Recovery, Chemical Production and Beyond. Renew. Energy 2016, 98, 153–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, X.; Huang, X.; Liang, P.; Xiao, K.; Zhou, Y.; Zhang, X.; Logan, B.E. A New Method for Water Desalination Using Microbial Desalination Cells. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2009, 43, 7148–7152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chiranjeevi, P.; Mohanakrishna, G.; Venkata Mohan, S. Rhizosphere Mediated Electrogenesis with the Function of Anode Placement for Harnessing Bioenergy through CO2 Sequestration. Bioresour. Technol. 2012, 124, 364–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- ElMekawy, A.; Hegab, H.M.; Vanbroekhoven, K.; Pant, D. Techno-Productive Potential of Photosynthetic Microbial Fuel Cells through Different Configurations. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2014, 39, 617–627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harnisch, F.; Schröder, U. From MFC to MXC: Chemical and Biological Cathodes and Their Potential for Microbial Bioelectrochemical Systems. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2010, 39, 4433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, S.; Liu, H.; Logan, B.E. Power Densities Using Different Cathode Catalysts (Pt and CoTMPP) and Polymer Binders (Nafion and PTFE) in Single Chamber Microbial Fuel Cells. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2006, 40, 364–369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohanakrishna, G.; Venkata Mohan, S.; Sarma, P.N. Bio-Electrochemical Treatment of Distillery Wastewater in Microbial Fuel Cell Facilitating Decolorization and Desalination along with Power Generation. J. Hazard. Mater. 2010, 177, 487–494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chandrasekhar, K.; Kumar, G.; Venkata Mohan, S.; Pandey, A.; Jeon, B.-H.; Jang, M.; Kim, S.H. Microbial Electro-Remediation (MER) of Hazardous Waste in Aid of Sustainable Energy Generation and Resource Recovery. Environ. Technol. Innov. 2020, 19, 100997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patil, S.A.; Gildemyn, S.; Pant, D.; Zengler, K.; Logan, B.E.; Rabaey, K. A Logical Data Representation Framework for Electricity-Driven Bioproduction Processes. Biotechnol. Adv. 2015, 33, 736–744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Logan, B.E.; Wallack, M.J.; Kim, K.-Y.; He, W.; Feng, Y.; Saikaly, P.E. Assessment of Microbial Fuel Cell Configurations and Power Densities. Environ. Sci. Technol. Lett. 2015, 2, 206–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caizán-Juanarena, L.; Borsje, C.; Sleutels, T.; Yntema, D.; Santoro, C.; Ieropoulos, I.; Soavi, F.; ter Heijne, A. Combination of Bioelectrochemical Systems and Electrochemical Capacitors: Principles, Analysis and Opportunities. Biotechnol. Adv. 2020, 39, 107456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baudler, A.; Schmidt, I.; Langner, M.; Greiner, A.; Schröder, U. Does It Have to Be Carbon? Metal Anodes in Microbial Fuel Cells and Related Bioelectrochemical Systems. Energy Environ. Sci. 2015, 8, 2048–2055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hays, S.; Zhang, F.; Logan, B.E. Performance of Two Different Types of Anodes in Membrane Electrode Assembly Microbial Fuel Cells for Power Generation from Domestic Wastewater. J. Power Sources 2011, 196, 8293–8300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, H.-Y.; Wang, Y.-X.; He, C.-S.; Qin, Y.; Li, W.-Q.; Li, W.-H.; Mu, Y. Redox Mediator-Modified Biocathode Enables Highly Efficient Microbial Electro-Synthesis of Methane from Carbon Dioxide. Appl. Energy 2020, 274, 115292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, G.-Y.; Yang, S.-S.; Ding, J.; Chen, C.-X.; Zhong, L.; Ding, L.; Ma, M.; Sun, G.-S.; Huang, Z.-L.; Ren, N.-Q. Immobilized Redox Mediators on Modified Biochar and Their Role on Azo Dye Biotransformation in Anaerobic Biological Systems: Mechanisms, Biodegradation Pathway and Theoretical Calculation. Chem. Eng. J. 2021, 423, 130300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Shi, Z.; Shi, L.; White, G.F.; Richardson, D.J.; Clarke, T.A.; Fredrickson, J.K.; Zachara, J.M. Effects of Soluble Flavin on Heterogeneous Electron Transfer between Surface-Exposed Bacterial Cytochromes and Iron Oxides. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 2015, 163, 299–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castro, F.A.V.; Mariani, D.; Panek, A.D.; Eleutherio, E.C.A.; Pereira, M.D. Cytotoxicity Mechanism of Two Naphthoquinones (Menadione and Plumbagin) in Saccharomyces Cerevisiae. PLoS ONE 2008, 3, e3999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Speers, A.M.; Reguera, G. Electron Donors Supporting Growth and Electroactivity of Geobacter Sulfurreducens Anode Biofilms. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2012, 78, 437–444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, D.; Xing, D.; Mei, X.; Liu, B.; Guo, C.; Ren, N. Electricity Generation by Shewanella Sp. HN-41 in Microbial Fuel Cells. Int. J. Hydrog. Energy 2013, 38, 15568–15573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nastro, R.A.; Salvian, A.; Kuppam, C.; Pasquale, V.; Pietrelli, A.; Rossa, C.A. Inorganic Carbon Assimilation and Electrosynthesis of Platform Chemicals in Bioelectrochemical Systems (BESs) Inoculated with Clostridium Saccharoperbutylacetonicum N1-H4. Microorganisms 2023, 11, 735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.-W.; He, H.; Zeng, R.J.; Sheng, G.-P. Chitin Degradation and Electricity Generation by Aeromonas Hydrophila in Microbial Fuel Cells. Chemosphere 2017, 168, 293–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ilamathi, R.; Merline Sheela, A.; Nagendra Gandhi, N. Comparative Evaluation of Pseudomonas Species in Single Chamber Microbial Fuel Cell with Manganese Coated Cathode for Reactive Azo Dye Removal. Int. Biodeterior. Biodegrad. 2019, 144, 104744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Narayanasamy, S.; Jayaprakash, J. Improved Performance of Pseudomonas Aeruginosa Catalyzed MFCs with Graphite/Polyester Composite Electrodes Doped with Metal Ions for Azo Dye Degradation. Chem. Eng. J. 2018, 343, 258–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keogh, D.; Lam, L.N.; Doyle, L.E.; Matysik, A.; Pavagadhi, S.; Umashankar, S.; Low, P.M.; Dale, J.L.; Song, Y.; Ng, S.P.; et al. Extracellular Electron Transfer Powers Enterococcus Faecalis Biofilm Metabolism. mBio 2018, 9, e00626-14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guo, Y.; Wang, G.; Zhang, H.; Wen, H.; Li, W. Effects of Biofilm Transfer and Electron Mediators Transfer on Klebsiella Quasipneumoniae Sp. 203 Electricity Generation Performance in MFCs. Biotechnol. Biofuels 2020, 13, 162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chugh, B.; Sheetal; Singh, M. ; Thakur, S.; Pani, B.; Singh, A.K.; Saji, V.S. Extracellular Electron Transfer by Pseudomonas Aeruginosa in Biocorrosion: A Review. ACS Biomater. Sci. Eng. 2022, 8, 1049–1059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zani, A.C.B.; Almeida, É.J.R. de; Furlan, J.P.R.; Pedrino, M.; Guazzaroni, M.-E.; Stehling, E.G.; Andrade, A.R. de; Reginatto, V. Electrobiochemical Skills of Pseudomonas Aeruginosa Species That Produce Pyocyanin or Pyoverdine for Glycerol Oxidation in a Microbial Fuel Cell. Chemosphere 2023, 335, 139073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moradali, M.F.; Ghods, S.; Rehm, B.H.A. Pseudomonas Aeruginosa Lifestyle: A Paradigm for Adaptation, Survival, and Persistence. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 2017, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Askitosari, T.D.; Boto, S.T.; Blank, L.M.; Rosenbaum, M.A. Boosting Heterologous Phenazine Production in Pseudomonas Putida KT2440 Through the Exploration of the Natural Sequence Space. Front. Microbiol. 2019, 10, 1990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schalk, I.J.; Guillon, L. Pyoverdine Biosynthesis and Secretion in Pseudomonas Aeruginosa : Implications for Metal Homeostasis: Pyoverdine Biosynthesis. Environ. Microbiol. 2013, 15, 1661–1673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Slate, A.J.; Hickey, N.A.; Butler, J.A.; Wilson, D.; Liauw, C.M.; Banks, C.E.; Whitehead, K.A. Additive Manufactured Graphene-Based Electrodes Exhibit Beneficial Performances in Pseudomonas Aeruginosa Microbial Fuel Cells. J. Power Sources 2021, 499, 229938. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dell’Anno, F.; Vitale, G.A.; Buonocore, C.; Vitale, L.; Palma Esposito, F.; Coppola, D.; Della Sala, G.; Tedesco, P.; de Pascale, D. Novel Insights on Pyoverdine: From Biosynthesis to Biotechnological Application. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 11507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yong, X.-Y.; Yan, Z.-Y.; Shen, H.-B.; Zhou, J.; Wu, X.-Y.; Zhang, L.-J.; Zheng, T.; Jiang, M.; Wei, P.; Jia, H.-H.; et al. An Integrated Aerobic-Anaerobic Strategy for Performance Enhancement of Pseudomonas Aeruginosa-Inoculated Microbial Fuel Cell. Bioresour. Technol. 2017, 241, 1191–1196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Almeida, E.J.R.; Halfeld, G.G.; Reginatto, V.; de Andrade, A.R. Simultaneous Energy Generation, Decolorization, and Detoxification of the Azo Dye Procion Red MX-5B in a Microbial Fuel Cell. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 2021, 9, 106221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mancílio, L.B.K.; Ribeiro, G.A.; Lopes, E.M.; Kishi, L.T.; Martins-Santana, L.; de Siqueira, G.M.V.; Andrade, A.R.; Guazzaroni, M.-E.; Reginatto, V. Unusual Microbial Community and Impact of Iron and Sulfate on Microbial Fuel Cell Ecology and Performance. Curr. Res. Biotechnol. 2020, 2, 64–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kubannek, F.; Thiel, S.; Bunk, B.; Huber, K.; Overmann, J.; Krewer, U.; Biedendieck, R.; Jahn, D. Performance Modelling of the Bioelectrochemical Glycerol Oxidation by a Co-Culture of Geobacter Sulfurreducens and Raoultella Electrica. ChemElectroChem 2020, 7, 1877–1888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayta, E.N.; Ertelt, M.J.; Kretschmer, M.; Lieleg, O. Bacterial Materials: Applications of Natural and Modified Biofilms. Adv. Mater. Interfaces 2021, 8, 2101024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiang, L.; Li, G.; Wen, L.; Su, C.; Liu, Y.; Tang, H.; Dai, J. Biodegradation of Aromatic Pollutants Meets Synthetic Biology. Synth. Syst. Biotechnol. 2021, 6, 153–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alves, L. de F.; Meleiro, L.P.; Silva, R.N.; Westmann, C.A.; Guazzaroni, M.-E. Novel Ethanol- and 5-Hydroxymethyl Furfural-Stimulated β-Glucosidase Retrieved From a Brazilian Secondary Atlantic Forest Soil Metagenome. Front. Microbiol. 2018, 9, 2556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bagdasarian, M.; Lurz, R.; Rückert, B.; Franklin, F.C.H.; Bagdasarian, M.M.; Frey, J.; Timmis, K.N. Specific-Purpose Plasmid Cloning Vectors II. Broad Host Range, High Copy Number, RSF 1010-Derived Vectors, and a Host-Vector System for Gene Cloning in Pseudomonas. Gene 1981, 16, 237–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Amarelle, V.; Roldán, D.M.; Fabiano, E.; Guazzaroni, M.-E. Synthetic Biology Toolbox for Antarctic Pseudomonas Sp. Strains: Toward a Psychrophilic Nonmodel Chassis for Function-Driven Metagenomics. ACS Synth. Biol. 2023, 12, 722–734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- de Siqueira, G.M.V.; Guazzaroni, M.-E. Host-Dependent Improvement of GFP Expression in Pseudomonas Putida KT2440 Using Terminators of Metagenomic Origin. ACS Synth. Biol. 2023, 12, 1562–1566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lovley, D.R.; Phillips, E.J.P. Novel Mode of Microbial Energy Metabolism: Organic Carbon Oxidation Coupled to Dissimilatory Reduction of Iron or Manganese. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 1988, 54, 1472–1480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, H.; Logan, B.E. Electricity Generation Using an Air-Cathode Single Chamber Microbial Fuel Cell in the Presence and Absence of a Proton Exchange Membrane. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2004, 38, 4040–4046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hall, B.G. EXPERIMENTAL EVOLUTION OF A NEW ENZYMATIC FUNCTION. II. EVOLUTION OF MULTIPLE FUNCTIONS FOR EBG ENZYME IN E. COLI. Genetics 1978, 89, 453–465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dykhuizen, D.E.; Dean, A.M. Enzyme Activity and Fitness: Evolution in Solution. Trends Ecol. Evol. 1990, 5, 257–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva-Rocha, R.; Martínez-García, E.; Calles, B.; Chavarría, M.; Arce-Rodríguez, A.; de las Heras, A.; Páez-Espino, A.D.; Durante-Rodríguez, G.; Kim, J.; Nikel, P.I.; et al. The Standard European Vector Architecture (SEVA): A Coherent Platform for the Analysis and Deployment of Complex Prokaryotic Phenotypes. Nucleic Acids Res. 2013, 41, D666–D675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.-L.; Li, H.-N.; Song, H.-T.; Xiao, W.-J.; Xia, W.-C.; Liu, X.-P.; Jiang, Z.-B. Construction of a Trifunctional Cellulase and Expression in Saccharomyces Cerevisiae Using a Fusion Protein. BMC Biotechnol. 2018, 18, 43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bankevich, A.; Nurk, S.; Antipov, D.; Gurevich, A.A.; Dvorkin, M.; Kulikov, A.S.; Lesin, V.M.; Nikolenko, S.I.; Pham, S.; Prjibelski, A.D.; et al. SPAdes: A New Genome Assembly Algorithm and Its Applications to Single-Cell Sequencing. J. Comput. Biol. 2012, 19, 455–477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prjibelski, A.; Antipov, D.; Meleshko, D.; Lapidus, A.; Korobeynikov, A. Using SPAdes De Novo Assembler. Curr. Protoc. Bioinforma. 2020, 70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meier-Kolthoff, J.P.; Göker, M. TYGS Is an Automated High-Throughput Platform for State-of-the-Art Genome-Based Taxonomy. Nat. Commun. 2019, 10, 2182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dwivedi, A.; Agrawal, D.; Jha, A.; Mathiyazhagan, K. Studying the Interactions among Industry 5.0 and Circular Supply Chain: Towards Attaining Sustainable Development. Comput. Ind. Eng. 2023, 176, 108927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, N.; Anam, M.; Yousaf, S.; Maleeha, S.; Bangash, Z. Characterization of the Electric Current Generation Potential of the Pseudomonas Aeruginosa Using Glucose, Fructose, and Sucrose in Double Chamber Microbial Fuel Cell. Iran. J. Biotechnol. 2017, 15, 216–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- da Silva, G.P.; Mack, M.; Contiero, J. Glycerol: A Promising and Abundant Carbon Source for Industrial Microbiology. Biotechnol. Adv. 2009, 27, 30–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lovley, D.R. Powering Microbes with Electricity: Direct Electron Transfer from Electrodes to Microbes: Feeding Microbes Electricity. Environ. Microbiol. Rep. 2011, 3, 27–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bosire, E.M.; Rosenbaum, M.A. Electrochemical Potential Influences Phenazine Production, Electron Transfer and Consequently Electric Current Generation by Pseudomonas Aeruginosa. Front. Microbiol. 2017, 8, 892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghssein, G.; Ezzeddine, Z. A Review of Pseudomonas Aeruginosa Metallophores: Pyoverdine, Pyochelin and Pseudopaline. Biology 2022, 11, 1711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schalk, I.J.; Hannauer, M.; Braud, A. New Roles for Bacterial Siderophores in Metal Transport and Tolerance: Siderophores and Metals Other than Iron. Environ. Microbiol. 2011, 13, 2844–2854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meier-Kolthoff, J.P.; Auch, A.F.; Klenk, H.-P.; Göker, M. Genome Sequence-Based Species Delimitation with Confidence Intervals and Improved Distance Functions. BMC Bioinformatics 2013, 14, 60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saati-Santamaría, Z.; Peral-Aranega, E.; Velázquez, E.; Rivas, R.; García-Fraile, P. Phylogenomic Analyses of the Genus Pseudomonas Lead to the Rearrangement of Several Species and the Definition of New Genera. Biology 2021, 10, 782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Girard, L.; Lood, C.; Höfte, M.; Vandamme, P.; Rokni-Zadeh, H.; van Noort, V.; Lavigne, R.; De Mot, R. The Ever-Expanding Pseudomonas Genus: Description of 43 New Species and Partition of the Pseudomonas Putida Group. Microorganisms 2021, 9, 1766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lalucat, J.; Gomila, M.; Mulet, M.; Zaruma, A.; García-Valdés, E. Past, Present and Future of the Boundaries of the Pseudomonas Genus: Proposal of Stutzerimonas Gen. Nov. Syst. Appl. Microbiol. 2022, 45, 126289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, D.; Liu, C.-M.; Luo, R.; Sadakane, K.; Lam, T.-W. MEGAHIT: An Ultra-Fast Single-Node Solution for Large and Complex Metagenomics Assembly via Succinct de Bruijn Graph. Bioinformatics 2015, 31, 1674–1676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Palleroni, N.J.; Moore, E.R.B. Taxonomy of Pseudomonads: Experimental Approaches. In Pseudomonas; Ramos, J.-L., Ed.; Springer US: Boston, MA, 2004; pp. 3–44. ISBN 978-1-4613-4788-0. [Google Scholar]

- Rojo, F. Carbon Catabolite Repression in Pseudomonas : Optimizing Metabolic Versatility and Interactions with the Environment. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 2010, 34, 658–684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chong, H.; Yeow, J.; Wang, I.; Song, H.; Jiang, R. Improving Acetate Tolerance of Escherichia Coli by Rewiring Its Global Regulator CAMP Receptor Protein (CRP). PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e77422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, H.-M.; Jeon, B.-Y.; Oh, M.-K. Microbial Production of Ethanol from Acetate by Engineered Ralstonia Eutropha. Biotechnol. Bioprocess Eng. 2016, 21, 402–407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Huang, B.; Wu, H.; Li, Z.; Ye, Q.; Zhang, Y.-H.P. Production of Succinate from Acetate by Metabolically Engineered Escherichia Coli. ACS Synth. Biol. 2016, 5, 1299–1307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ni, C.; Wu, X.; Dan, J.; Du, D. Facile Recovery of Acetic Acid from Waste Acids of Electronic Industry via a Partial Neutralization Pretreatment (PNP) – Distillation Strategy. Sep. Purif. Technol. 2014, 132, 23–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Li, W.; Zhang, Z.-Z.; Tan, T.-W.; Li, Z.-J. Metabolic Engineering of Escherichia Coli for the Synthesis of Polyhydroxyalkanoates Using Acetate as a Main Carbon Source. Microb. Cell Factories 2018, 17, 102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shahid, S.; Mosrati, R.; Ledauphin, J.; Amiel, C.; Fontaine, P.; Gaillard, J.-L.; Corroler, D. Impact of Carbon Source and Variable Nitrogen Conditions on Bacterial Biosynthesis of Polyhydroxyalkanoates: Evidence of an Atypical Metabolism in Bacillus Megaterium DSM 509. J. Biosci. Bioeng. 2013, 116, 302–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fernández-Sandoval, M.T.; Huerta-Beristain, G.; Trujillo-Martinez, B.; Bustos, P.; González, V.; Bolivar, F.; Gosset, G.; Martinez, A. Laboratory Metabolic Evolution Improves Acetate Tolerance and Growth on Acetate of Ethanologenic Escherichia Coli under Non-Aerated Conditions in Glucose-Mineral Medium. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2012, 96, 1291–1300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rajaraman, E.; Agarwal, A.; Crigler, J.; Seipelt-Thiemann, R.; Altman, E.; Eiteman, M.A. Transcriptional Analysis and Adaptive Evolution of Escherichia Coli Strains Growing on Acetate. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2016, 100, 7777–7785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sanches-Medeiros, A.; Monteiro, L.M.O.; Silva-Rocha, R. Calibrating Transcriptional Activity Using Constitutive Synthetic Promoters in Mutants for Global Regulators in Escherichia Coli. Int. J. Genomics 2018, 2018, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Amarelle, V.; Sanches-Medeiros, A.; Silva-Rocha, R.; Guazzaroni, M.-E. Expanding the Toolbox of Broad Host-Range Transcriptional Terminators for Proteobacteria through Metagenomics. ACS Synth. Biol. 2019, 8, 647–654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nora, L.C.; Westmann, C.A.; Guazzaroni, M.-E.; Siddaiah, C.; Gupta, V.K.; Silva-Rocha, R. Recent Advances in Plasmid-Based Tools for Establishing Novel Microbial Chassis. Biotechnol. Adv. 2019, 37, 107433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Atkinson, J.T.; Campbell, I.; Bennett, G.N.; Silberg, J.J. Cellular Assays for Ferredoxins: A Strategy for Understanding Electron Flow through Protein Carriers That Link Metabolic Pathways. Biochemistry 2016, 55, 7047–7064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Bacterium | Characteristics | Reference |

|---|---|---|

| DH5α | F– φ80lacZΔM15 Δ(lacZYA-argF)U169 recA1 endA1 hsdR17(rK–, mK+) phoA supE44 λ–thi-1 gyrA96 relA1 | |

| DH5α pSEVA232 | DH5α carrying plasmid pSEVA232 (KmR) | [40] |

| DH5α pSEVA232_Cel5a | DH5α carrying plasmid pSEVA232_Cel5a, and endoglucanase from Bacillus subtilis 168 (KmR) | [40] |

| Pseudomonas putida KT2440 | Reference bacteria | [41] |

| KT2440 pSEVA 228 | KT2440 carrying plasmid pSEVA228 (KmR) | [42] |

| KT2440 pSEVA 232 | KT2440 carrying plasmid pSEVA232 (KmR) | [42] |

| KT2440 pSEVA 247y | KT2440 carrying plasmid pSEVA247Y (KmR) | [42] |

| KT2440 pVANT | KT2440 carrying plasmid pVANT (KmR) | [43] |

| KT2440 pVANT-Pj100mCherry | KT2440 carrying plasmid Pvant - Pj100 - mCherry (KmR) | This work |

| KT2440 pSEVA231 | KT2440 carrying plasmid pSEVA231 (KmR) | [42] |

| KT2440 pSEVA231-Pj100GFP | KT2440 carrying plasmid PSEVA231 - Pj100 - GFP (KmR) | [42] |

| KT2440 pSEVA231-Pj106GFP | KT2440 carrying plasmid PSEVA231 - Pj106 - GFP (KmR) | [42] |

| KT2440 pSEVA231-Pj114GFP | KT2440 carrying plasmid PSEVA231 - Pj114 - GFP (KmR) | [42] |

| KT2440 pSEVA232_Cel5a | KT2440 carrying plasmid Pseva232 – Cel5a (KmR) | [40] |

| Pseudomonas sp. BJa5 | Bacterium isolated from garden soil in Ribeirão Preto, Brazil | This work |

| BJa5 pSEVA 228 | BJa5 carrying plasmid pSEVA228 (KmR) | This work |

| BJa5 pSEVA 232 | BJa5 carrying plasmid pSEVA232 (KmR) | This work |

| BJa5 pSEVA 247y | BJa5 carrying plasmid pSEVA247Y (KmR) | This work |

| BJa5 pVANT | BJa5 carrying plasmid pVANT (KmR) | This work |

| BJa5 pVANT-Pj100mCherry | BJa5 carrying plasmid Pvant - Pj100 mCherry (KmR) | This work |

| BJa5 pSEVA231 | BJa5 carrying plasmid PSEVA231 (KmR) | This work |

| BJa5 pSEVA231-Pj100GFP | BJa5 carrying plasmid PSEVA231 - Pj100 - GFP (KmR) | This work |

| BJa5 pSEVA231-Pj106GFP | BJa5 carrying plasmid PSEVA231 - Pj106 - GFP (KmR) | This work |

| BJa5 pSEVA231-Pj114GFP | BJa5 carrying plasmid PSEVA231 - Pj114 - GFP (KmR) | This work |

| BJa5 pSEVA232_Cel5a | BJa5 carrying plasmid Pseva232 – Cel5a (KmR) | This work |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).