Submitted:

20 June 2023

Posted:

27 June 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

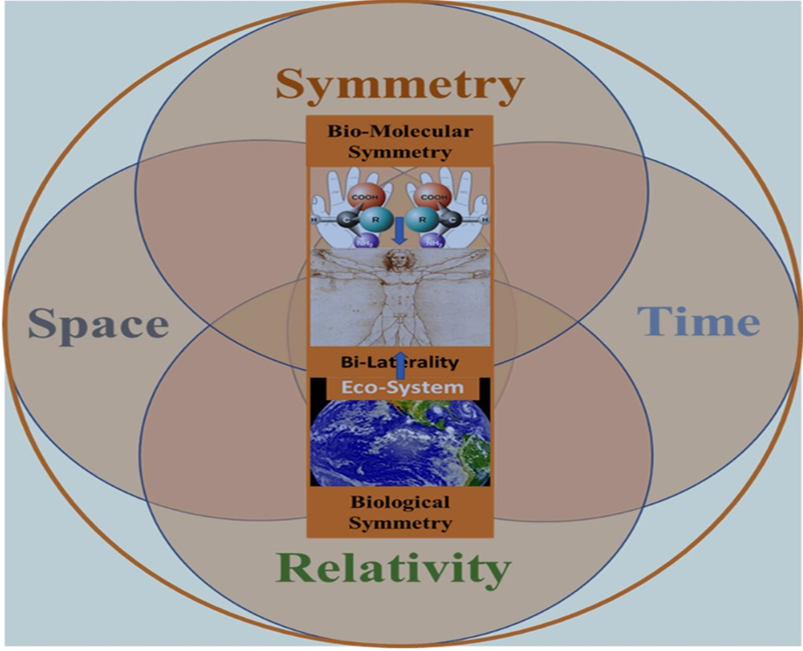

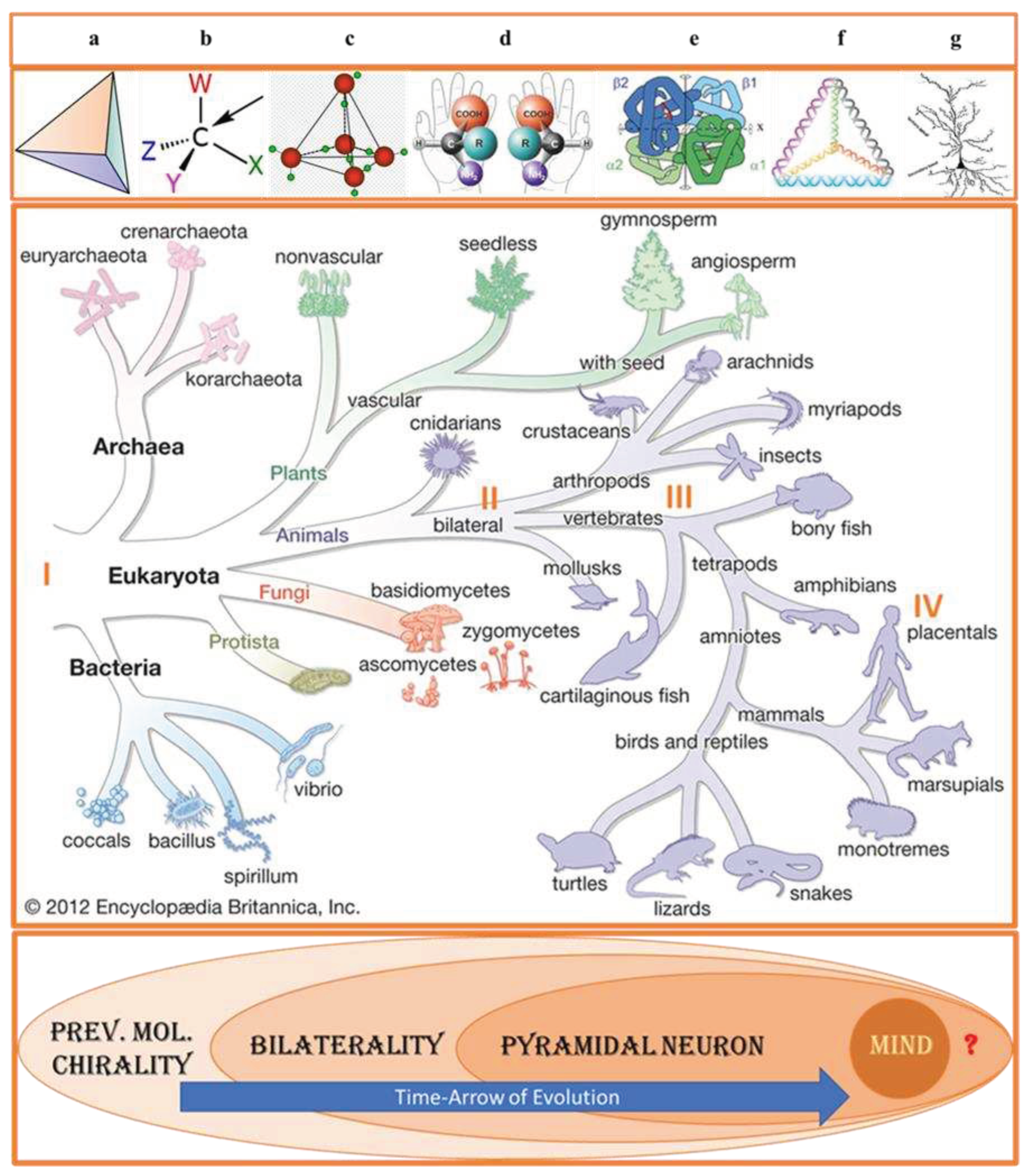

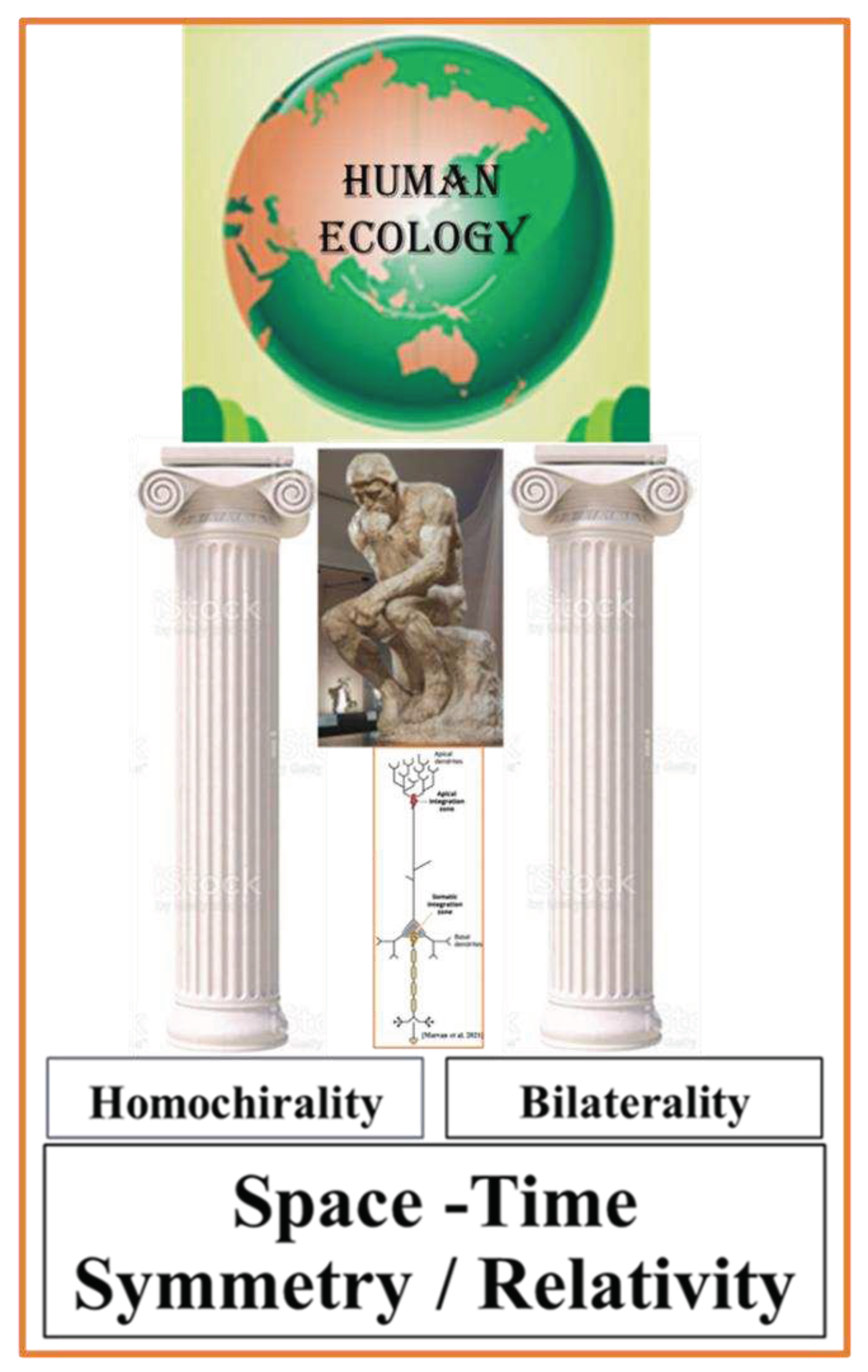

Introduction

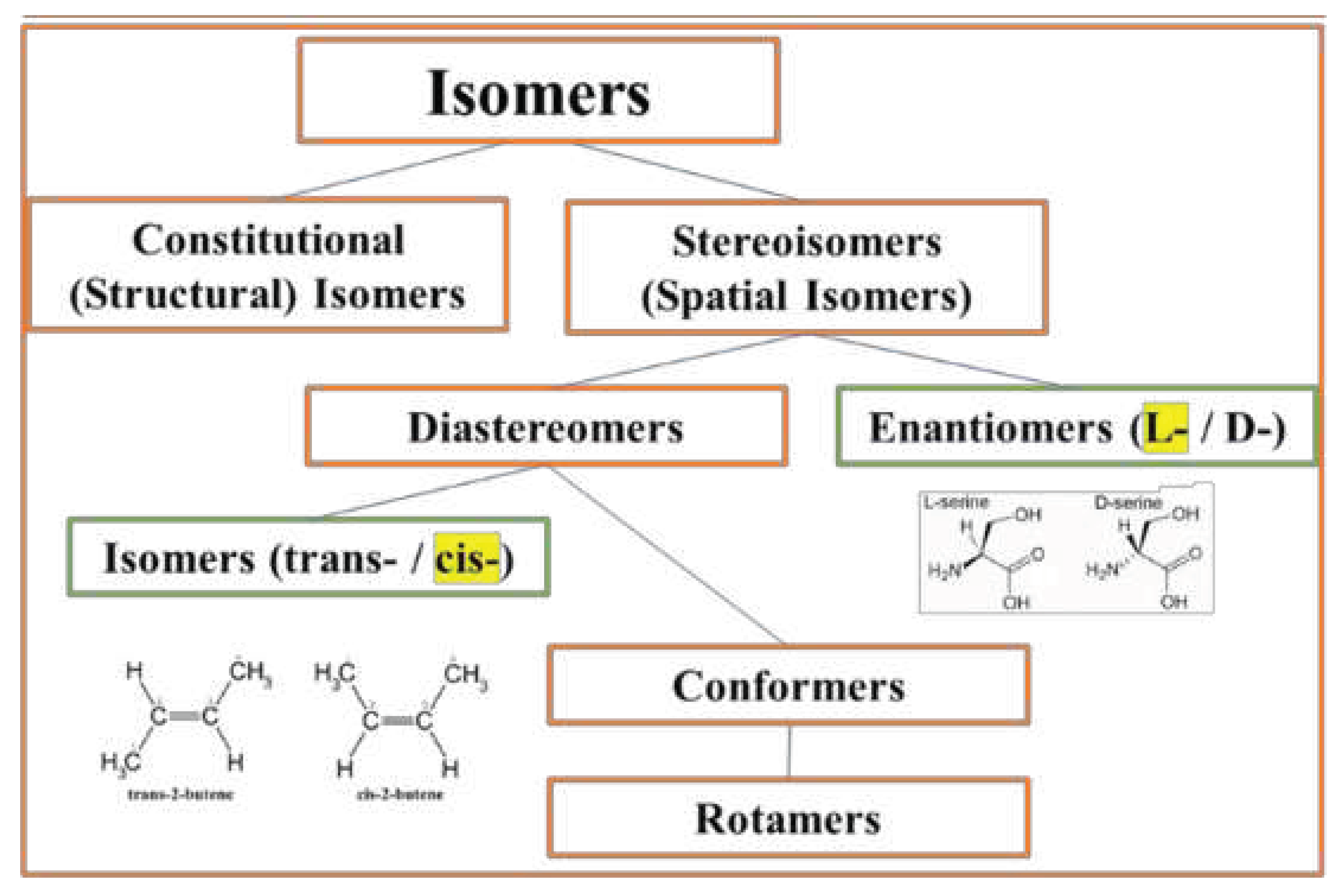

Molecular Chirality

Link of Physiological and Psychological Functions

Bilateral Organism: Symmetry-Function Interplay

Pyramidal Neurons

Conclusion

Author Contributions

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

References

- Betz, W. Distinction of two nerve centers in the brain. Q J Microsc Sci 1875, 15, 190–192. [Google Scholar]

- Dahanayake, J.N. and Mitchell-Koch, K.R. Entropy connects water structure and dynamics in protein hydration layer. Phys.Chem.Chem.Phys., 2018, 20, 14765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marvan, T.; Polák, M.; Bachmann, T. and Phillips, W.A. Apical amplification—a cellular mechanism of conscious perception? Neuroscience of Consciousness, 2021, 2021(2), 2021. [CrossRef]

- Kumar, P.; Buldyrev, S.V. and H. Eugene, H. A tetrahedral entropy for water. PNAS. 2009, 106 (52) 22130-22134. [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Ye, M.; Kuang, X.; Li, Y. and Hu, S. A simplified morphological classification scheme for pyramidal cells in six layers of primary somatosensory cortex of juvenile rats. IBRO Rep. 2018, 74–90. [CrossRef]

- Luine, V. and Frankfurt, M. Interactions between estradiol, BDNF and dendritic spines in promoting memory. Neuroscience. 2013, 239, 34–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sousa, A.M.M.; Meyer, K.A.; Santpere, G.; Gulden, F.O. and Sestan, N. Evolution of the Human Nervous System Function, Structure, and Development. Cell. 2017 Jul 13; 170(2): 226–247. [CrossRef]

- Mason, S.F. The development of concepts of chiral discrimination. Chirality 1989, 1(3), 183–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bastings, J.J.A.J.; van Eijk, H.M.; Damink. S.W.O and Sander S. Rensen, S.S. D-amino Acids in Health and Disease: A Focus on Cancer. Nutrients 2019, 11(9), 2205. [CrossRef]

- Kondepudi, D. Chiral Asymmetry in Nature, Ch. 1 in Chiral Analysis (Second Edition). Advances in Spectroscopy, Chromatography and Emerging Methods 2018, pg. 3-28. [CrossRef]

- Cristadoro, G., Degli Esposti, M. & Altmann, E.G. The common origin of symmetry and structure in genetic sequences. Sci Reports 2018, 8, 15817. [CrossRef]

- Dyakin, V.V. Fundamental Cause of Bio-Chirality: Space-Time Symmetry—Concept Review. Symmetry 2023, 15(1), 79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Inaki, M.; Liu, J. and Matsuno, K. Cell chirality: its origin and roles in left–right asymmetric development. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci. 2016, 371(1710). [CrossRef]

- Lin, YM. Creating chirality. Nat Chem Biol. 2008, 4, 330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takaoka, K.; Yamamoto, M.; and Hamada, H. Origin of body axes in the mouse embryo. Current Opinion in Genetics & Development 2007, 17(4}44-350. [CrossRef]

- Dyakin, V.V.; Lucas, J.; Dyakina-Fagnano, N.V.; Posner, E.P.; Vadasz, C. The Chain of Chirality Transfer as Determinant of Brain Functional Laterality. Breaking the Chirality Silence: Search for New Generation of Biomarkers; Relevance to Neurodegenerative Diseases, Cognitive Psychology, and Nutrition Science. Neurology and Neuroscience Research. 2017, 1(1),2. [CrossRef]

- Duan, P.; Cao, H.; Zhang, L.; Liu, M. Gelation induced supramolecular chirality: chirality transfer, amplification and application. Soft Matter. 2014, 10, 5428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vallortigara, G. The evolutionary psychology of left and right: costs and benefits of lateralization Dev Psychobiol. 2006 Sep;48(6):418-27. [CrossRef]

- Francks, C. Exploring human brain lateralization with molecular genetics and genomics Annals of The New York Academy of Sciences Issue: The Year in Cognitive Neuroscience. 2015, 1359, 1-13. [CrossRef]

- Stacho, M. and Manahan-Vaughan, D. Mechanistic flexibility of the retrosplenial cortex enables its contribution to spatial cognition. Trends in Neuroscience. 2022, 45(4), P284-296. 4. [CrossRef]

- Lee, T-W; Dolan, R.J.; and Critchley, H.D. Controlling Emotional Expression: Behavioral and Neural Correlates of Nonimitative Emotional Responses. Cerebral Cortex, 2008, 18(1), 104–113. [CrossRef]

- Yuan, J.; Lu, X.; Zhang, S.; Zheng, F.; Deng, Q.; Han, L. and Lu, Q. Molecular Chirality and Morphological Structural Chirality of Exogenous Chirality-Induced Liquid Crystalline Block Copolymers. Macromolecules 2022, 55, 5, 1566–1575. [CrossRef]

- [Jung. 1976] Book by C.G. Jung. Psychological Types (The Collected Works of C. G. Jung, Vol. 6) (Bollingen Series XX). (Part of the Jung’s Collected Works (#6) Series and Dzieła (#2) Series). Publisher: Princeton University Press. 1976. 1977.

- Assagioli, A. Dynamic Psychology and Psychosynthesis. Publisher: Psychosynthesis Research Foundation, inc 1958. Roberto Assagioli.

- Myers, S. The five functions of psychological type. Analytical Psychology 2016, 61(2), 183–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pillai, A.S. and Jirsa, V.K. Perspective. Symmetry Breaking in Space-Time Hierarchies Shapes Brain Dynamics and Behavior. Neuron 2017, 94(5), 1010-1026. [CrossRef]

- Jirsa, V. and Sheheitli, H. Entropy, free energy, symmetry and dynamics in the brain. Journal of Physics: Complexity 2022 3(1), 015007. [CrossRef]

- Dyakin, V.V. and Uversky, V.N. Arrow of Time, Entropy, and Protein Folding: Holistic View on Biochirality. Int J Mol Sci. 2022, 23(7):3687. [CrossRef]

- Iohnston, I.G.; Dingle,K.; Greenbury, S.F.; Camargo, C.Q.; Doye , J.P.K.; Ahnert, S.E. and Louis, A.A. Symmetry and simplicity spontaneously emerge from the algorithmic nature of evolution. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2022, 119(11), e2113883119. [CrossRef]

- Jammer, M. Concepts of Space: The history of Theories of Space in Physics, 3rd ed.; Dover: New York, NY, USA, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Capecchi, D. Development of the Concept of Space up to Newton Encyclopedia 2022, 2(3), 1528-1544. [CrossRef]

- Zinovyev et al. Manifestation of Supramolecular Chirality during Adsorption on CsCuCl3 and γ-Glycine Crystals. Symmetry 2023,15(2):498. [CrossRef]

- Ocklenburg & Mundorf. Ocklenburg S. and Mundorf, A. Symmetry and asymmetry in biological structures Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. PNAS. 2022, 119 (28), e2204881119. [CrossRef]

- Tasson, J.D. What Do We Know About Lorentz Invariance? Rep. Prog. Phys. 2014, 77, 062901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Comte, C. Symmetry, relativity and quantum mechanics. Nuov Cim B 1996, 111, 937–956. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Field, J.N. Space-Time Exchange Invariance: Special Relativity as a Symmetry Principle. American Journal of Physics 2001, 69, 569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajaltouni, Z.J. Symmetry and relativity: From classical mechanics to modern particle physics. Natural Science. 2014, 6(4), Article ID:43343,7 pages. [CrossRef]

- Auffray, C. and Nottale, L. Review. Scale relativity theory and integrative systems biology: 1: Founding principles and scale laws. Progress in Biophysics and Molecular Biology 2008, 97(1), 79-114,. [CrossRef]

- Noble, R.; Tasaki, K.; Noble, P.J. and Noble, D. Biological Relativity Requires Circular Causality but Not Symmetry of Causation: So, Where, What and When Are the Boundaries? Front. Physiol. Sec. Integrative Physiology 2019, 10. [CrossRef]

- Cornelissen, J.J.L.M.; Rowan, A.E.; Nolte, R.J.M. and Sommerdijk, N.A.J.M. Chiral Architectures from Macromolecular Building Blocks Chem. Rev. 2001, 101, 12, 4039–4070. [CrossRef]

- Todoroff, N.; Kunze, J.; Schreuder, H.; Hessler, G.; Baringhaus, K-H. and Schneider, G. (2014). Fractal Dimensions of Macromolecular Structures. Mol Inform. 2014, 33(9): 588–596. [CrossRef]

- Wang, J., Panagiotou, E. The protein folding rate and the geometry and topology of the native state. Sci Rep 12, 6384. [CrossRef]

- Pandey, S., Mandal, S., Danielsen, M.B. et al. Chirality transmission in macromolecular domains. Nat Common 2022, 13, 76. [CrossRef]

- Kim, N.H., Choi, H., Shahzad, Z.M. et al. Supramolecular assembly of protein building blocks: from folding to function. Nano Convergence 2022, 9(4). [CrossRef]

- Dhanavade, M.J. and Sonawane K.D. Amyloid beta peptide-degrading microbial enzymes and its implication in drug design. 3 Biotech. 2020, 10(6), 247. [CrossRef]

- Reetz, M.T. and Garcia-Borràs, M. The Unexplored Importance of Fleeting Chiral Intermediates in Enzyme-Catalyzed Reactions. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2021, 143, 37, 14939–14950. [CrossRef]

- Dyakin, V.V.; Dyakina-Fagnano, N.V.; Mcintire, L.B. and Uversky, V.N. Fundamental Clock of Biological Aging: Convergence of Molecular, Neurodegenerative, Cognitive and Psychiatric Pathways: Non-Equilibrium Thermodynamics Meet Psychology. Int J Mol Sci. 2022, 23(1), 285. [CrossRef]

- Dyakin, V.V.; Wisniewski T.M. and Lajtha, A. Chiral Interface of Amyloid Beta (Aβ): Relevance to Protein Aging, Aggregation and Neurodegeneration. Symmetry 2020, 12(4), 585. [CrossRef]

- Fujii, N.; Takata, T.; Fujii,N.; Aki K. & Sakaue, H. D-Amino Acid Residues in Proteins Related to Aging and Age-Related Diseases and a New Analysis of the Isomers in Proteins Chapter in the book (pg 241-245) by Yoshimura, T., Nishikawa, T., Homma, H. (eds) D-Amino Acids Springer, Tokyo. [CrossRef]

- Taniguchi, K.; Sawamura, H.; Ikeda, Y.; Tsuji, A.; Kitagishi,Y. and Matsuda, S. Omar Cauli, Academic Editor and Soraya L. Valles, Academic Editor D-Amino Acids as a Biomarker in Schizophrenia. Diseases. 2022, 10(1), 9. [CrossRef]

- Jacco J.A.J. Bastings, Hans M. van Eijk, Steven W. Olde Damink,and Sander S. Rensen. D-amino Acids in Health and Disease: A Focus on Cancer. Nutrients. 2019, 11(9): 2205. [CrossRef]

- Murtas, G. and Pollegioni, L. D-Amino Acids and Cancer: Friends or Foes? Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24(4), 3274. 4. [CrossRef]

- Wolosker, H., Balu, D.T. D-Serine as the gatekeeper of NMDA receptor activity: implications for the pharmacologic management of anxiety disorders. Transl Psychiatry 2020 10, 184. [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Han, H.; Yin, J.; Li, T.and Yina, Y. Role of D-aspartate on biosynthesis, racemization, and potential functions: A mini-review. Anim Nutr. 2018, 4(3): 311–315. [CrossRef]

- Saitoh, Y.; Katane, M.; Miyamoto, T.; Sekine, M.; Sakai-Kato, K. and Homma, H. D-Serine and D-Alanine Regulate Adaptive Foraging Behavior in Caenorhabditis elegans via the NMDA Recepto,r Journal of Neuroscience 2020, 40 (39) 7531-7544. [CrossRef]

- Kera, Y.; Aoyama, H.; Matsumura, H.; Hasegawa, Hisae Nagasaki, H. and Yamada, R. Presence of free d-glutamate and d-aspartate in rat tissues. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta (BBA) 1995, 1243(2), 282-286. [CrossRef]

- Mangas, A.; Coveñas,R.; Bodet, D.; Geffard, M.; Aguilar, L.A. and Yajeya, J. Immunocytochemical visualization of d-glutamate in the rat brain. Neuroscience 2007, 144(2), 654-664. [CrossRef]

- Lin CH, Yang HT, Lane HY. d-glutamate, d-serine, and d-alanine differ in their roles in cognitive decline in patients with Alzheimer’s disease or mild cognitive impairment. Pharmacol Biochem Behav 2019,185: 172760. [CrossRef]

- Luo, Q.; Hou, C.; Bai, Y.; Wang, R. and Liu, J. Protein Assembly: Versatile Approaches to Construct Highly Ordered Nanostructures. Chem. Rev. (American Chemical Society) 2016, 116, 22, 13571–13632. [CrossRef]

- Riccio, A.; Vitagliano, L.; di Prisco, G.; Zagari, A. and Mazzarella, L. The crystal structure of a tetrameric hemoglobin in a partial hemichrome state. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2002, 99(15), 9801–9806. [CrossRef]

- Ha, C-E. and Bhagavan, N.V. Hemoglobin Chapter in Essentials of Medical Biochemistry. eBook ISBN: 9780124166974. Sec Ed. Elsevier 2015.

- Goldstein, E. B. Crosstalk between psychophysics and physiology in the study of perception. In E. B. Goldstein (Ed.). Blackwell handbook of perception (pp. 1–23). Blackwell Publishing. 2001.

- Xu, X.; Hanganu-Opatz,I.L. and Bieler, M. Cross-Talk of Low-Level Sensory and High-Level Cognitive Processing: Development, Mechanisms, and Relevance for Cross-Modal Abilities of the Brain. Front. Neurorobot. 2020, 14. [CrossRef]

- Logothetis, N.K. and Pauls, J. Psychophysical and Physiological Evidence for Viewer-centered Object Representations in the Primate. Cerebral Cortex 1995, 3, 270–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mascalzoni, E.; Osorio, D.; Regolinm L. and Giorgio Vallortigara, G. Symmetry perception by poultry chicks and its implications for three-dimensional object recognition. Proc Biol Sci. 2012. 7;279(1730), 841-6. [CrossRef]

- Pizlo, Z. and de Barros, J. A. The Concept of Symmetry and the Theory of Perception Front. Comput. Neurosci., 2021, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakade, Y. ; Iwata,Y.; Furuichi, K.; Mita, M.; Hamase, K.; Konno, R. et al. Gut microbiota-derived D-serine protects against acute kidney injury. The Journal of Clinical Investigation Insight 2018 18, 3(20), e97957. [CrossRef]

- Freud, S. An outline of psychoanalysis. Std Edn. Vol. 23. London: Vintage. 1940.

- Wada, K.; Yamamoto, M. and Nakashima, K. Psychological function in aging. Nihon Rinsho (Janan) 2013, 71(10).1713-9.

- Bottaccioli, A.G.; Bologna, M. and Bottaccioli, F. Psychic Life-Biological Molecule Bidirectional Relationship: Pathways, Mechanisms, and Consequences for Medical and Psychological Sciences—A Narrative Review. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 3932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corballis, M. C., & Beale, I. L. Bilateral symmetry and behavior. Psychological Review 1970, 77(5), 451–464. 5. [CrossRef]

- Delvenne, J-F.; Castronovo, J.; Demeyere, N. and umphreys, G.W. Bilateral Field Advantage in Visual Enumeration PLOS 2011. [CrossRef]

- Tamaki Amano and Motomi Toichi. Zoi Kapoula, Editor. The Role of Alternating Bilateral Stimulation in Establishing Positive Cognition in EMDR. Therapy: A Multi-Channel Near-Infrared Spectroscopy Study. PLoS One, 2016; 11, e0162735. [CrossRef]

- Boukezzi, S.; Silva, C.; Nazarian, B.; Rousseau, P-F.; Guedj, E. and Valenzuela-Moguillansky, C. Bilateral Alternating Auditory Stimulations Facilitate Fear Extinction and Retrieval. Front. Psychol. Sec. Psychology for Clinical Settings 2017, 8. [CrossRef]

- Kasprian G, Langs G, Brugger PC, Bittner M, Weber M, Arantes M, et al. The prenatal origin of hemispheric asymmetry: an in-utero neuroimaging study. Cereb Cortex 2011, 21, 1076–1083. [CrossRef]

- Mitter, C.; Prayer, D.; Brugger, P.C.; Weber, M. and Kaspria, G. In Vivo Tractography of Fetal Association Fibers. PLOS. ONE 2015, 10(3), e011953. 3. [CrossRef]

- Than, K. Symmetry in Nature: Fundamental Fact or Human Bias. Live Science. 2005. Available online: https://www.livescience.com/4002-symmetry-nature-fundamental-fact-human-bias.html.

- Gunturkun, O and Ocklenburg, S. Ontogenesis of Lateralization. Neuron, 2017, 94(2), 249–263. [CrossRef]

- Mehler, M.F. Epigenetic Principles and Mechanisms Underlying Nervous System Functions in Health and Disease. Prog Neurobiol. 2008, 86(4): 305–341. [CrossRef]

- Zion, E. and Chen, X. Breaking Symmetry: The Asymmetries in Epigenetic Inheritance. Biochem (Lond). 2021. 43(1): 14–19. [CrossRef]

- Wan, L.Q.; Chin, A.S.; Worley, K.E. and Ray, P. Cell chirality: emergence of asymmetry from cell culture. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci. 2016, 371(1710), 20150413. [CrossRef]

- Sun. Na.; Dou, X.; Tang, Z.; Zhang, D.; Ni, N.; Wang, J.; Gao, H.; Ju, Y.; Dai, X.; Zhao, C.; Gu, P.; Ji, J. and Feng, C. Bio-inspired chiral self-assemblies promoted neuronal differentiation of retinal progenitor cells through activation of metabolic pathway. Bioactive Materials 2021, 6(4), 990-997. 4. [CrossRef]

- Dong, C., Madar, A.D. & Sheffield, M.E.J. Distinct place cell dynamics in CA1 and CA3 encode experience in new environments. Nat Commun 2021, 12, 2977. [CrossRef]

- Graham, H.K. and Duan, X. Molecular mechanisms regulating synaptic specificity and retinal circuit formation. Wiley Interdiscip Rev Dev Biol. 2021, 10(1), e379. 1. [CrossRef]

- Matho,K.S; Huilgol, D.; Galbavy, W.; He, M.; Kim, G.; Xu An, Xu.; Lu, J. et al. Genetic dissection of the glutamatergic neuron system in cerebral cortex. Nature. 2021, 598, 7879):182-187. [CrossRef]

- Bekkers. J.M. Pyramidal neurons. Current biology Curr Biol. 2011, 21(24), R975. 24. [CrossRef]

- Banovac, I.; Sedmak, D.; Džaja, D.; Jalšovec, D.; Milošević, N.J.; Rašin, [M.R. and Petanjek, Z. Somato-dendritic morphology and axon origin site specify von Economo neurons as a subclass of modified pyramidal neurons in the human anterior cingulate cortex. Journal of Anatomy 2019, 235, 3, 651-666. [CrossRef]

- Johns, P. Neurons and glial cells. Chapter 5 in Clinical Neuroscience, 2014, 61-69. [CrossRef]

- Sha, Z.; Schijven, D.; Carrion-Castillo, A.; Joliot, M.; Mazoyer, B.; Fisher, S.E.; Crivello, F. and Francks, C. The genetic architecture of structural left-right asymmetry of the human brain. Nature Human Behaviour 2021, 5, 1226–1239. [CrossRef]

- Krupic, J.; Bauza, M.; Burton, S.; Barry,C. and O’Keefe, J. Grid cell symmetry is shaped by environmental geometry. Nature. 2015, 518(7538): 232–235. [CrossRef]

- M. Oh, M.M.; Simkin, D. and Disterhoft, J.F. Intrinsic Hippocampal Excitability Changes of Opposite Signs and Different Origins in CA1 and CA3 Pyramidal Neurons Underlie Aging-Related Cognitive Deficits. Front. Syst. Neurosci. 2016, 10. [CrossRef]

- Constant M. and Mellet, E. The Impact of Handedness, Sex, and Cognitive Abilities on Left–Right Discrimination: A Behavioral Study. Front. Psychol. 2018, 9, 405. [CrossRef]

- Merrick, C.M.; Dixon, T.C.; Breska, A.; Lin, J.; Chang, E.F.; King-Stephens, D.; Laxer, K.D.; Weber, P.B.; Carmena, J.; Knight, R.T. and Ivry, R.B. Left hemisphere dominance for bilateral kinematic encoding in the human brain. eLife 2022, 11, e69977. [CrossRef]

- Jiang, S., Guan, Y., Chen, S. et al. Anatomically revealed morphological patterns of pyramidal neurons in layer 5 of the motor cortex. Sci Rep 2020, 10, 7916. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kawakami, R.; Shinohara, Y.; Kato, Y.; Sugiyama, H.; Shigemoto, R, and Itoauthors, I. Asymmetrical allocation of NMDA receptor ε2 subunits in hippocampal sircuitry. Science 2003, 300(5621), 990-994. [CrossRef]

- Shinohara, Y.; Hirase, H.; Watanabe, M, Makoto Itakura, M.; Masami Takahashi, M.and Shigemoto, R. Edited by Huganir,R.L. Left-right asymmetry of the hippocampal synapses with differential subunit allocation of glutamate receptors. PNAS. 2008,105 (49) 19498-19503. [CrossRef]

- Muller, J.F.; Mascagni, F. and McDonald. A.J. Pyramidal Cells of the Rat Basolateral Amygdala. Synaptology and Innervation by Parvalbumin-immunoreactive Interneurons. J Comp Neurol. 2006, 494(4): 635–650. [CrossRef]

- Lorente de Nó R, L. Cerebral cortex: architecture, intracortical connections and motor projections. In: Physiology of the nervous system, 3rd edn (Fulton JF, ed.), pp. 288–330. Oxford: Oxford University Press. 1949.

- Chan, C.H.; Godinho, L.N.; Thomaidou, D.; Tan, S.S. ; Gulisano, M and Parnavelas J. G. Emx1 is a Marker for Pyramidal Neurons of the Cerebral Cortex. Cerebral Cortex 2001, 11(12), 1191–1198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hawkins, J. and Ahmad, S. Hypothesis and theory article. Why Neurons Have Thousands of Synapses, a Theory of Sequence Memory in Neocortex. Front. Neural Circuits, 2016, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Parnavelas, JG.; Dinopoulos, A. and Davies SW. The central visual pathways. In: Handbook of chemical neuroanatomy, vol. 7. Integrated systems of the CNS, Part II (Björklund A, Hökfelt T, Swanson LW, eds), pp. 1–164. Amsterdam: Elsevier. 1989.

- Dallérac, G.; Li, X.; Lecouflet, P.; Morisot, N.; Sacchi, S.; Asselot, R.; Thu Ha Pham, T.H. et al. Dopaminergic neuromodulation of prefrontal cortex activity requires the NMDA receptor coagonist D-serine. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2021, 118(23): e2023750118. [CrossRef]

- O’Keefe, J. and Krupic, J. Do hippocampal pyramidal cells respond to nonspatial stimuli? Physiological review 2021, 101(3), 1427-145. [CrossRef]

- Purpura, D.P. and Suzuki, K. Distortion of neuronal geometry and formation of aberrant synapses in neuronal storage disease. Brain Research 1976, 116(1), 1-2. [CrossRef]

- Adámek, P.; Langová, V. Horáček, J. Early-stage visual perception impairment in schizophrenia, bottom-up and back again. Schizophrenia 2022 8, 27. [CrossRef]

- Granato, A. and De Giorgio, A. Alterations of neocortical pyramidal neurons: turning points in the genesis of mental retardation. Front. Pediatr. 2014. [CrossRef]

- Rennó-Costa, C. and Adriano Tort, A.B.L. Place and Grid Cells in a Loop: Implications for Memory Function and Spatial Coding. J Neurosci. 2017, 37(34), 8062-8076. [CrossRef]

- Kitanishi, T. , Ito, H.T., Hayashi, Y. et al. Network mechanisms of hippocampal laterality, place coding, and goal-directed navigation. J Physiol Sci, 2017; 67, 247–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhong, S.; He, Y.; Shu, H. and Gaolang Gong, G. Developmental Changes in Topological Asymmetry Between Hemispheric Brain White Matter Networks from Adolescence to Young Adulthood. Cerebral Cortex, 2017; 7, 2560–2570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goriounova, N.A.; Heyer, D.B.; Wilbers, R.; Verhoog, M.B.; Giugliano, M.; Christophe Verbist, C. et al. Large and fast human pyramidal neurons associated with intelligence. Elife. 2018, 18(7), e41714. [CrossRef]

- Kawakami, R.; Shinohara, Y. ; Kato,Y.; Sugiyama, H.; Shigemoto, R. and Ito, I. Asymmetrical Allocation of NMDA Receptor ε2 Subunits in Hippocampal Circuitry. Science New Series 2003, 300(621), 990-994. [CrossRef]

- Sá, M.J.; Ruela, C. and Madeira, M.D. Dendritic right/left asymmetries in the neurons of the human hippocampal formation: a quantitative Golgi study. Arq Neuropsiquiatr 2007, 65(4B), 1105-13. [CrossRef]

- Shinohara, Y.; Hirase, H.; Watanabe, M. ; +2, and Ryuichi Shigemoto, R. Left-right asymmetry of the hippocampal synapses with differential subunit allocation of glutamate receptors. PNAS 2008, 105 (49) 19498-19503. [CrossRef]

- Goto, K.; Kurashima, R.; Gokan, H.; Inoue, N.; Ito, I. and Watanabe, S. Left−Right Asymmetry Defect in the Hippocampal Circuitry Impairs Spatial Learning and Working Memory in iv Mice. PLOS ONE 2010, 5(11), e15468.

- Ukai, H.; Kawahara, A.; Hirayama, K.; Show all 17 Ito Isao, I. ItPirB regulates asymmetries in hippocampal circuitry. PLOS ONE 2017, 12(6). [CrossRef]

- Luengo-Sanchez, S.; Bielza, C.; Benavides-Piccione, R.; Fernaud-Espinosa, I.; DeFelipe, J. and Larrañaga, P. A univocal definition of the neuronal soma morphology using Gaussian mixture models. Front. Neuroanat., 2015, 9. [CrossRef]

- Rockland, K.S. Pyramidal Neurons: Looking for the origins of axons. Evolutionary Biology. Neuroscience 2022. [CrossRef]

- Abrous, D.N. , Koehl, M. & Lemoine, M. A. Baldwin interpretation of adult hippocampal neurogenesis: from functional relevance to physiopathology. Mol Psychiatry 2022. 27, 383–402. [CrossRef]

- Leguey, I.; Benavides-Piccione, R.; Rojo, C.; Larrañaga, P.; Bielza, C. and DeFelipe, J. Neurons in the Rat Somatosensory Cortex. eNeuro. 2019, 5(6). [CrossRef]

- Weiler, S.; Nilo, D.G.; Bonhoeffer, T.; Hübener, M.; Rose, T. and Scheuss, V. Orientation and direction tuning align with dendritic morphology and spatial connectivity in mouse visual cortex. Current Biology 2020, 32(8), 1743-1753.e7. [CrossRef]

- Wahle, P.; Sobierajski, E.; Gasterstädt, I. Lehmann,N.; Weber, S.; Lübke, H.R.; Engelhardt, M.; Distler, C. and Meyer, G. Neocortical pyramidal neurons with axons emerging from dendrites are frequent in non-primates, but rare in monkey and human. eLife. 2022, 11, e76101. [CrossRef]

- Musall, S. , Sun, X.R., Mohan, H. et al. Pyramidal cell types drive functionally distinct cortical activity patterns during decision-making. Nat Neurosci 2023. [CrossRef]

- Park, J.; Papoutsi, A.; Ash, R.T. et al. Contribution of apical and basal dendrites to orientation encoding in mouse V1 L2/3 pyramidal neurons. Nat Commun 10, 5372 (2019). [CrossRef]

- Elaine, M. Pinheiro, E.M.; Xie, Z.; Norovich, A.L.; Vidaki, M.; Tsai, L-H. and Gertler, F.B. Lpd depletion reveals that SRF specifies radial versus tangential migration of pyramidal neurons. Nat Cell Biol. 2011, 13(8), 989–995. [CrossRef]

- Hobert, O. Development of left/right asymmetry in the Caenorhabditis elegans nervous system: From zygote to postmitotic neuron. Genesis 2014, 52(6), 528–543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tee, Y. , Shemesh, T., Thiagarajan, V. et al. Cellular chirality arising from the self-organization of the actin cytoskeleton. Nat Cell Biol 2015.17, 445–457. [CrossRef]

- Radler, M.R.; Liu, X.; Peng, M.; Doyle, B.; Toyo-Oka, K. and Spiliotis, E.T.Pyramidal neuron morphogenesis requires a septin network that stabilizes filopodia and suppresses lamellipodia during neurite initiation. Current Biology 2023, 33(3), P434-448.E8. [CrossRef]

- Inaki, M.; Sasamura. T. and Kenji Matsuno, K. Review. Cell Chirality Drives Left-Right Asymmetric Morphogenesis. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 2018, 6. [CrossRef]

- Konietzny,A. ; Bär, J. and Mikhaylova, M. MINI REVIEW. Dendritic Actin Cytoskeleton: Structure, Functions, and Regulations. Front. Cell. Neurosci. Sec. Cellular Neurophysiology 2017, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Satir, P. Chirality of the cytoskeleton in the origins of cellular asymmetry Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci. 2016, 371(1710), 20150408. [CrossRef]

- Parato, J. and Bartolini, F.The microtubule cytoskeleton at the synapse Neurosci Lett. 2021, 14;753,135850. [CrossRef]

- Bocquet, A.; Berges, R.; Frank, R.; Robert, P.; Peterson, A.C. and Eyer, J. Neurofilaments Bind Tubulin and Modulate Its Polymerization. J Neurosci. 2009, 29(35), 11043–11054. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Uylings, H.B.; Jacobsen, A.M.; Zilles, K. and Amunts, K. Left-right asymmetry in volume and number of neurons in adult Broca’s area. Cortex. 2006, 42(4), 652-8. [CrossRef]

- El-Gaby, M.; Reeve, H.M. ; Lopes-dos-Santos,V.; Campo-Urriza, N.; Perestenko, P.V. Morley, A.; Strickland, L.A.M.; Lukács, I.P.; Paulsen, O. and Dupret, D. An Emergent Neural Coactivity Code for Dynamic Memory. Nat Neurosci. 2021, 24(5): 694–704. [CrossRef]

- Cullen, T.J.; Walker, M.A.; Eastwood, S.L.; Esiri, M.M.; Harrison, P.J. and Crow, T.J. Anomalies of asymmetry of pyramidal cell density and structure in dorsolateral prefrontal cortex in schizophrenia Br J Psychiatry 2006, 188:26-31. [CrossRef]

- Souta, R. An Introductory Perspective on the Emerging Application of qEEG. In the book Introduction to Quantitative EEG and Neurofeedback. Advsanced Theory and Applications. By Budzynski, T.H.; Washington, P.; Budzynski, H.K.; Washington, P.; Evans, J.R. and Abarbanel, A. Sec Ed. Acad. Press. 2009.

- Zhu, DY. , Cao, TT., Fan, HW. et al. The increased in vivo firing of pyramidal cells but not interneurons in the anterior cingulate cortex after neuropathic pain. Mol Brain. 2022, 15, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kong, X-Z.; Postema, M.C.; Guadalupe, T.; de Kovel, C.; Boedhoe, P.C.W.; Hoogman, M.; Mathias, S.R.; van Rooij, D.; Schijven, D.; Glahn, D.C.; Medland, S.E. et al., Mapping brain asymmety in health and disease through the ENIGMA consortium. Hum Brain Mapp. 2022, 43(1), 167–181. [CrossRef]

- Kay, J.W. and Phillips, W.A. Contextual Modulation in Mammalian Neocortex is Asymmetric. Symmetry 2020, 12(5), 815. [CrossRef]

- Tripathi, S. Dey,A.; Shanmugam, M.; Narayanan, R.S.and Chandrsekhar, V. Cobalt (II) Complexes as Single-Ion Magnets. Topics in Organometallic Chem 2019, 64. [CrossRef]

- Kagamiyama, H. and Hayashi, H. Crystallographic Structures. Branched-Chain Amino Acids, Part B. In book Methods in Enzymoligy. Elsevier 2000.

- Housecroft, C. E.; Sharpe, A. G. Inorganic Chemistry (2nd ed.). 2004. Prentice Hall. ISBN 978-0-13-039913-7.

- Gradišar, H.; Božič, S.; Doles, T.; Vengust, D.; Hafner-Bratkovič, I.; Mertelj, A.; Webb, B.; Šali, A.; Klavžar, S. and Roman Jerala, R. Design of a single-chain polypeptide tetrahedron assembled from coiled-coil segments. Nat Chem Biol. 2013, 9(6), 362–366. [CrossRef]

- Xie, N.; Liu, S.; Yang, X.; Xiaoxiao, He.; Huang, J. and Kemin Wang, K. DNA tetrahedron nanostructures for biological applications: biosensors and drug delivery. Analyst 2017, 18(142) 3322-3332. [CrossRef]

- Strychalski, W. 3D Computational Modeling of Bleb Initiation Dynamics. Front. Phys., Sec. Biophysics 2021, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoo, S.H. and Lee, H-S. Foldectures: 3D Molecular Architectures from Self-Assembly of Peptide Foldamers. Acc. Chem. Res. 2017, 50, 4, 832–841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sasaki, E. , Böhringer, D., van de Waterbeemd, M. et al. Structure and assembly of scalable porous protein cages. Nat Commun 2017, 8, 14663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quaye, I.K. Extracellular hemoglobin: the case of a friend turned foe. Front Physiol. 2015; 6, 96. [CrossRef]

- Eaton, A.W. Retrospective on statistical mechanical models for hemoglobin allostery editors-pick J. Chem. Phys. The Journal of Chemical Physics 2022, 157, 184104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Richter, F.; Meurers, B.H.; Zhu, C.; Medvedeva, V.P. and Chesselet, M-F. Neurons Express Hemoglobin α- and β-Chains in Rat and Human Brains. J Comp Neurol. 2009, 15(5): 538–547. [CrossRef]

- Walser, M.; Svensson, J.; Karlsson, Motalleb, R. ; Åberg, M.; Kuhn, H.G.; Isgaard, J. and Åberg, N.D. Growth Hormone and Neuronal Hemoglobin in the Brain—Roles in Neuroprotection and Neurodegenerative Diseases. Front. Endocrinol. Sec. Neuroendocrine Science 2021, 11. [CrossRef]

- Zheng, R.; Yan, Y.; Pu, J. and Zhang, B. Physiological and Pathological Functions of Neuronal Hemoglobin: A Key Underappreciated Protein in Parkinson’s Disease. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23(16), 9088. [CrossRef]

- Flynn, K.S. The cytoskeleton and neurite initiation. Bioarchitecture. 2013, 3(4): 86–109. [CrossRef]

- Giuliana Indelicato, Newton Wahome, Philippe Ringler. Shirley A. Müller, Mu-Ping Nieh, Peter Burkhard, Reidun Twarock. Principles Governing the Self-Assembly of Coiled-Coil Protein Nanoparticles. Biophysical Journal 2016, 110(3), P646-660. [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).