3.1. FE Simulation

As stated in section 2.2, the proper modeling of the silver sinter layer properties was a major part of the work on the simulation model. The silver sinter paste consists of two components: the metallic silver particle powder and an organic vehicle that serves as a matrix around the particles und converts the powder into an easily processible paste. As a result, it was necessary to determine the thermal conductivity of the paste as described in section 2.2. The results of the LaTIMA analysis are listed in

Table 4. The measured thermal conductivity values attract attention because the values decrease as the annealing temperatures rises. This behavior is unusual for sintered structures because with rising annealing temperatures the porosity in a sintered structure should decrease and thus, the thermal conductivity should rise. It can be presumed, that the sinter layer micro structure has an impact on the measured values, which will be discussed more detailed in section 3.5.

The resulting thermal dependent material properties of the silver paste were modeled like described in section 2.2.

Table 5 specifies the properties of the paste layer.

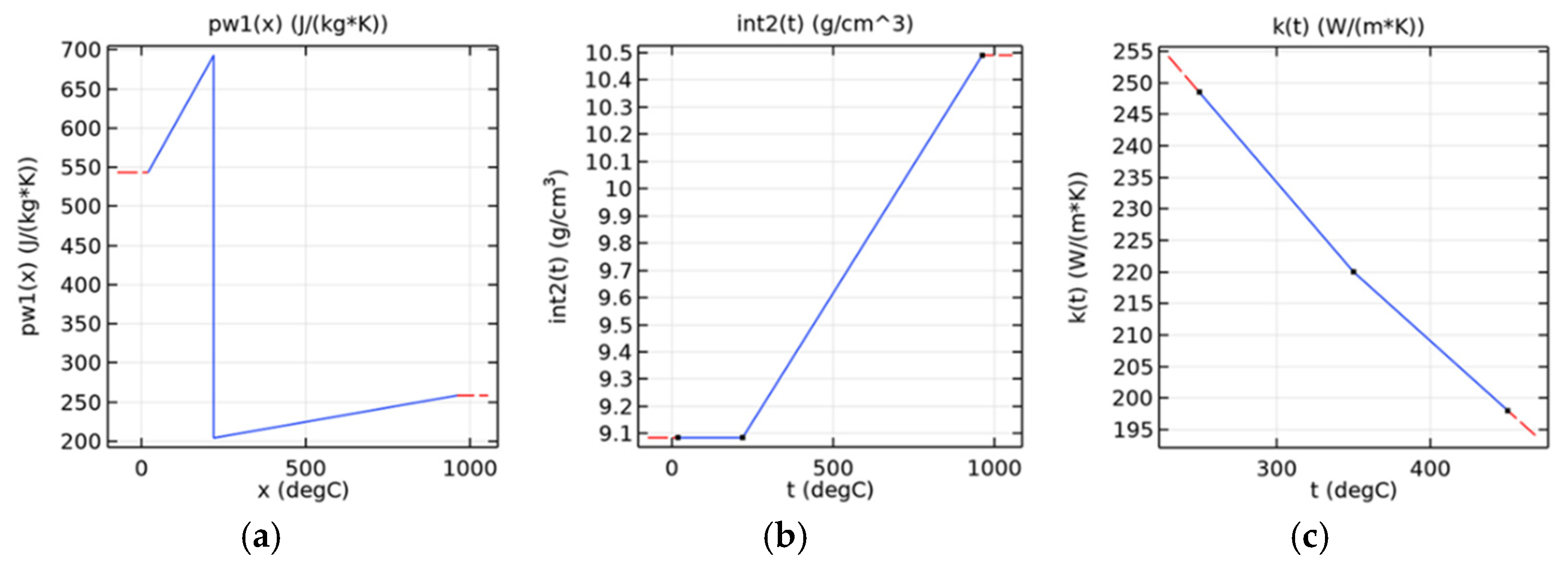

Figure 5 presents the associated modeled properties of heat capacity, density, and thermal conductivity as a function of temperature.

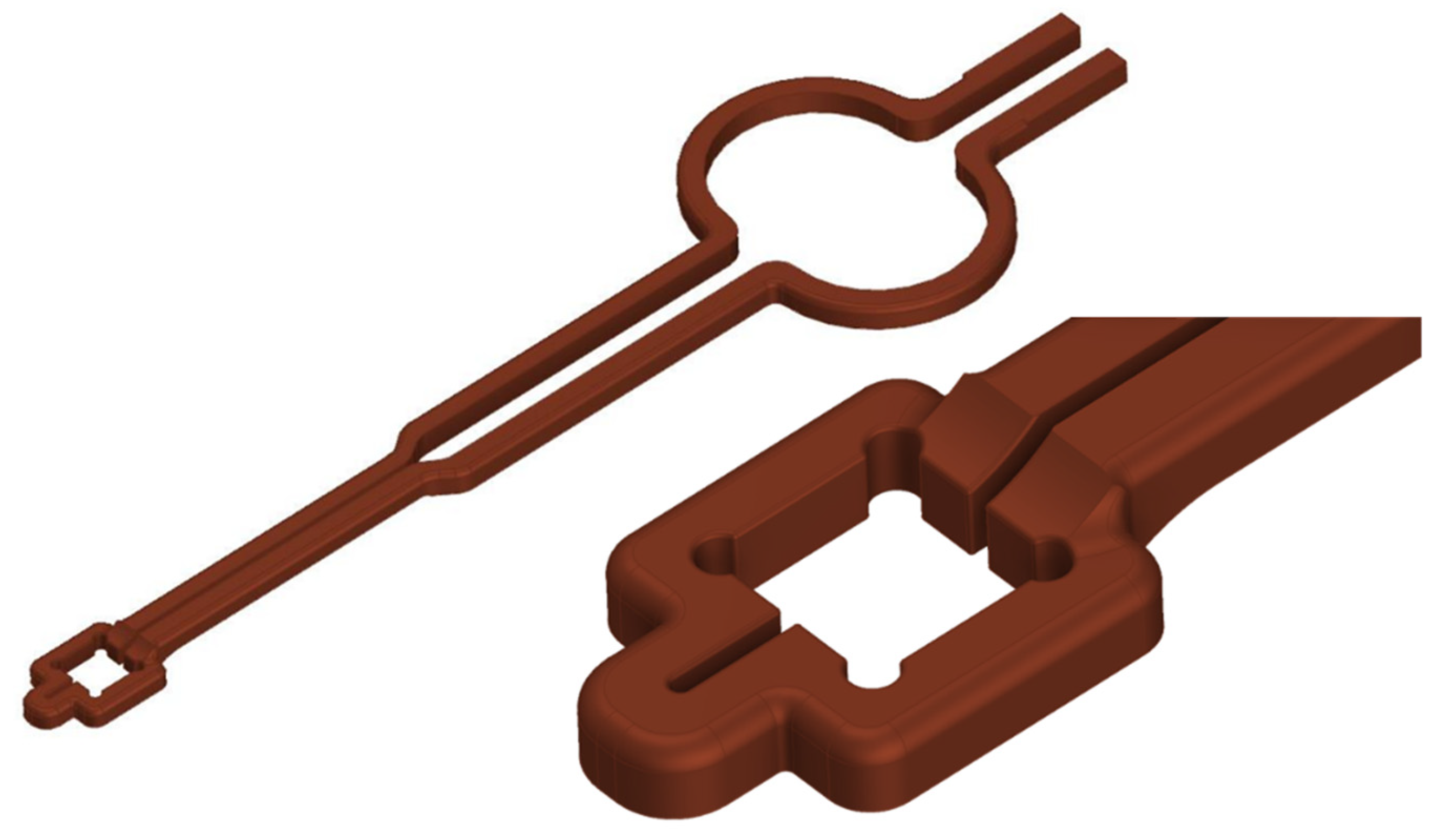

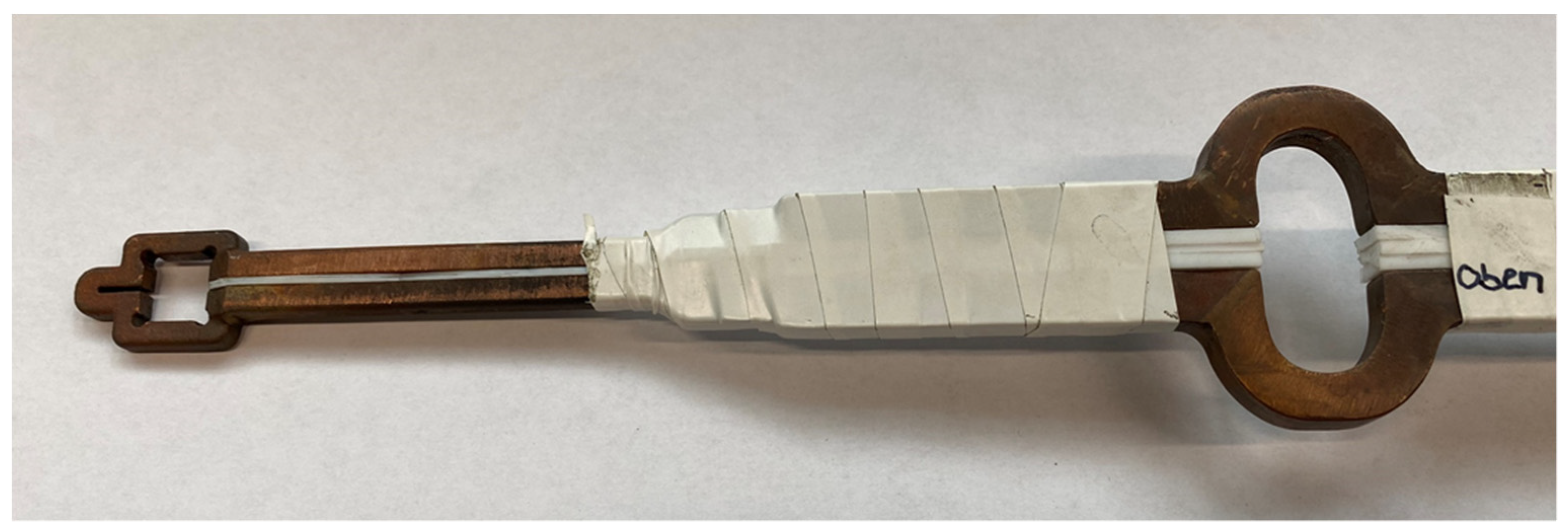

With the help of the simulation tools, it was possible to develop a suitable coil geometry for the single-chip bonding tests. The coil has a single convolution, which was subject to numerous iterative adjustments in design in order to focus the maximum heat input to the bonding area on the DBC substrate. As a result, good homogenization of the inductively generated heat could be realized, so that a uniform and selective heating of the bond zone is possible. An additional circular segment was realized in the rear part of the induction coil’s electric line, which allows to arrange a Rogowski coil at the coil, so that the current through the coil as well as the frequency of the alternating current could be measured in the experiments. A CAD image of the coil is shown in

Figure 6.

The developed coil was first analyzed virtually regarding its suitability for inductive heating of the stack.

Figure 7a demonstrates that with a coil current of

I = 1,280 A (peak-to-peak), a frequency of the electromagnetic field of

f = 1,022 kHz and a heating duration of

th = 7.0 s. FE simulations showed that sufficient heating (

Tsinter ≈ 230 °C) of the silver sintering pad can be realized. Areas of the DBC substrate that are below the coil convolution exhibit the highest temperatures, while temperatures decrease significantly with increasing distance from the convolution.

Figure 7b shows the surface temperature distribution within the silver sinter layer in detail. The temperatures at this location are 206.0 ≤

T ≤ 263.1 [°C]. A hot spot with

Tmax = 319.2 K is located at the lower edge of the DBC substrate because of the induced current accumulating there due to the skin effect. As a result of thermal conductivity, the bottom edge of the silver pad also exhibits a hot spot and the temperatures are decreasing significantly towards the silver pad top side. This temperature inhomogeneity (

ΔT = 57.1 K) within the silver pad could be problematic with regard to the formation of a homogeneous micro structure in the bond layer. Nevertheless, the temperatures in the bond zone are sufficiently high for the sintering reaction to take place. In addition, the peak temperatures in the bonding zone of

Tmax = 263.1 °C are not critical concerning the temperature stability of the semiconductor devices, so that no damage to them is to be expected during the induction based bonding process. The very short bonding times are also advantageous in terms of minimizing thermal stress in the diodes. The simulation results were verified by experimentally acquired results from heating tests, performed without the application of a bonding pressure, see section 3.3.

3.3. Heating Experiments

Heating experiments were carried out by heating the stack with the manufactured coil but without applying a bonding force. In the experiments, coil current ranges of 998 <

I < 1,434 [A] (peak-to-peak value), frequency ranges of 1,020 <

f < 1,022 [kHz] and heating times up to

t1 = 5.0 s as well as up to

t2 = 10.0 s were applied. The coupling distance in each experiment was

s1 = 1.0 mm. The selection of the process parameters was made with reference to the simulative investigations as described in section 2.3. Temperature measurement on the sample’s surface was performed by means of thermal camera.

Figure 9 shows an exemplary thermal camera picture of an inductively heated DBC substrate with a printed silver pad on it, which was captured during one of the heating test. This temperature measurement method was used in order to determine characteristic temperature values in the bond zone and in the surrounding DBC substrate area. A diode was not placed on the pad during the heating tests.

From the measured temperatures, it can be observed that the hottest area is a wedge-shaped area inside or directly below the coil convolution. Thus, most of the heat is generated in the bond zone. Areas outside of the convolution are significantly less heated. It can be stated that the experimentally determined heating pattern largely matches the simulated one (

Figure 7). For a more precise comparison of the results, the process parameters from

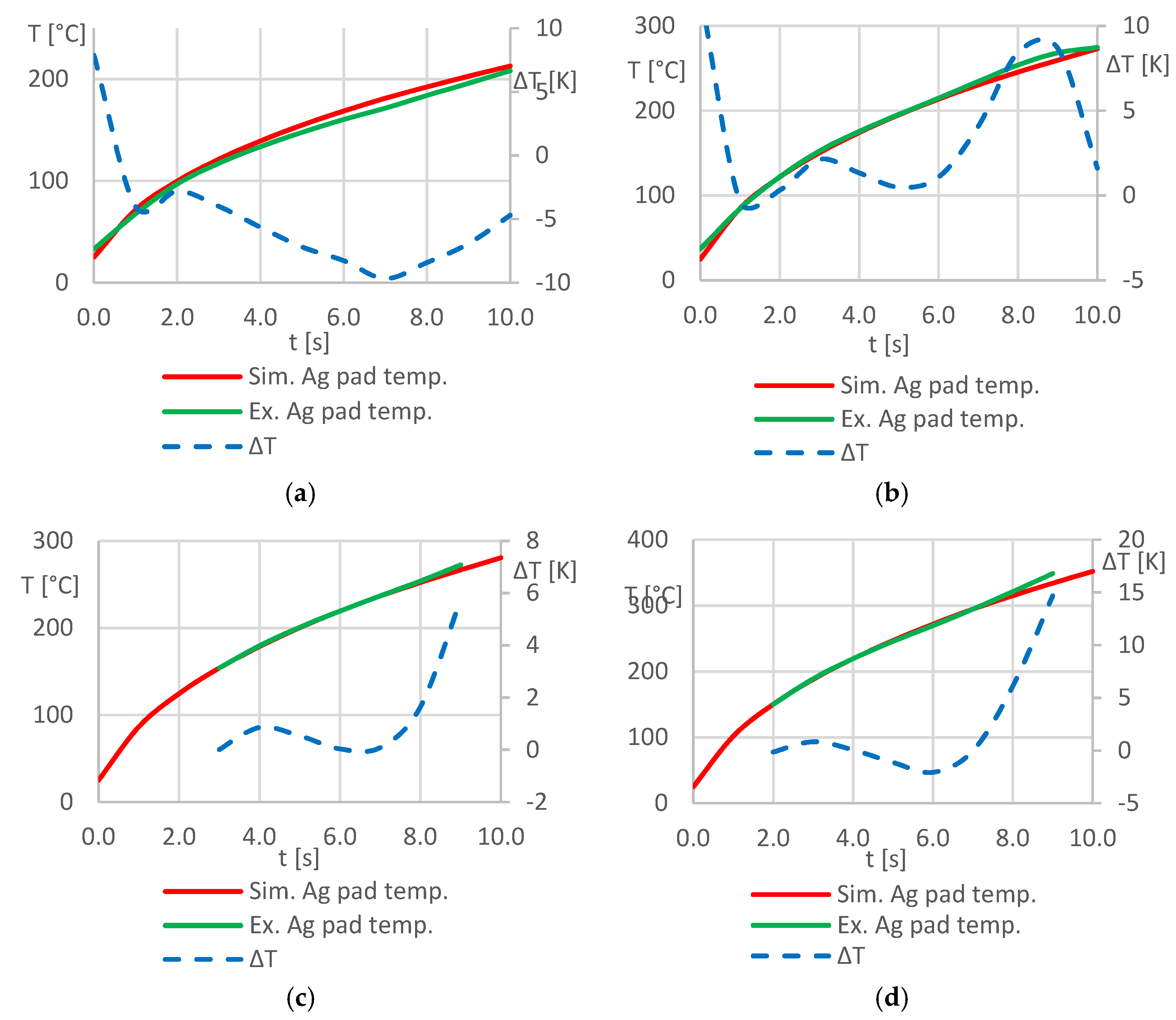

Table 6 were used in both, experiments and simulations, and the mean value of the surface temperature of the silver pad was measured and simulated, respectively. The resulting temperature-time graphs were plotted against each other as well as the absolute deviation of the temperature values.

Figure 10 shows the corresponding diagrams.

The diagrams clearly indicate that there is very good matching between simulated and measured temperature values. The mean values of the temperature deviations are

ΔTMV ≤ 5 K for all considered process parameter combinations. This suggests that the developed simulation model is robust and provides an accurate as well as time and space-resolved prediction of the temperatures in the stack in the investigated temperature range of 25 ≤

T ≤ 350 [°C]. In particular, larger deviations between measured and simulated temperature values can be observed at the beginning of the heating process in the experiments in

Figure 10a,b, as an initial temperature of

Tstart = 25 °C was selected as boundary condition for all simulations but could not be realized at the beginning of the experimental investigations.

3.5. REM Analysis

The bonded samples were cut into cross-sections (cut plane in the middle of the diode) and analyzed by SEM. In the following

Figure 11,

Figure 12 and

Figure 13, an overview of the bonded samples is presented. In the figures, the stack’s cross-section consists of the three-layered DBC substrate (DBC-Cu, DBC-Al

2O

3, DBC-Cu), the silver sinter layer and the diode (viewed from bottom to top). In each figure, four specimens from each test series (

Table 3) are depicted. For the four samples of each test series, the bonding pressure and the generator power were kept constant and the bonding time was varied. Because of different bonding times, different maximum temperatures were reached at the end of the heating process. The maximum temperatures are noted in the figures.

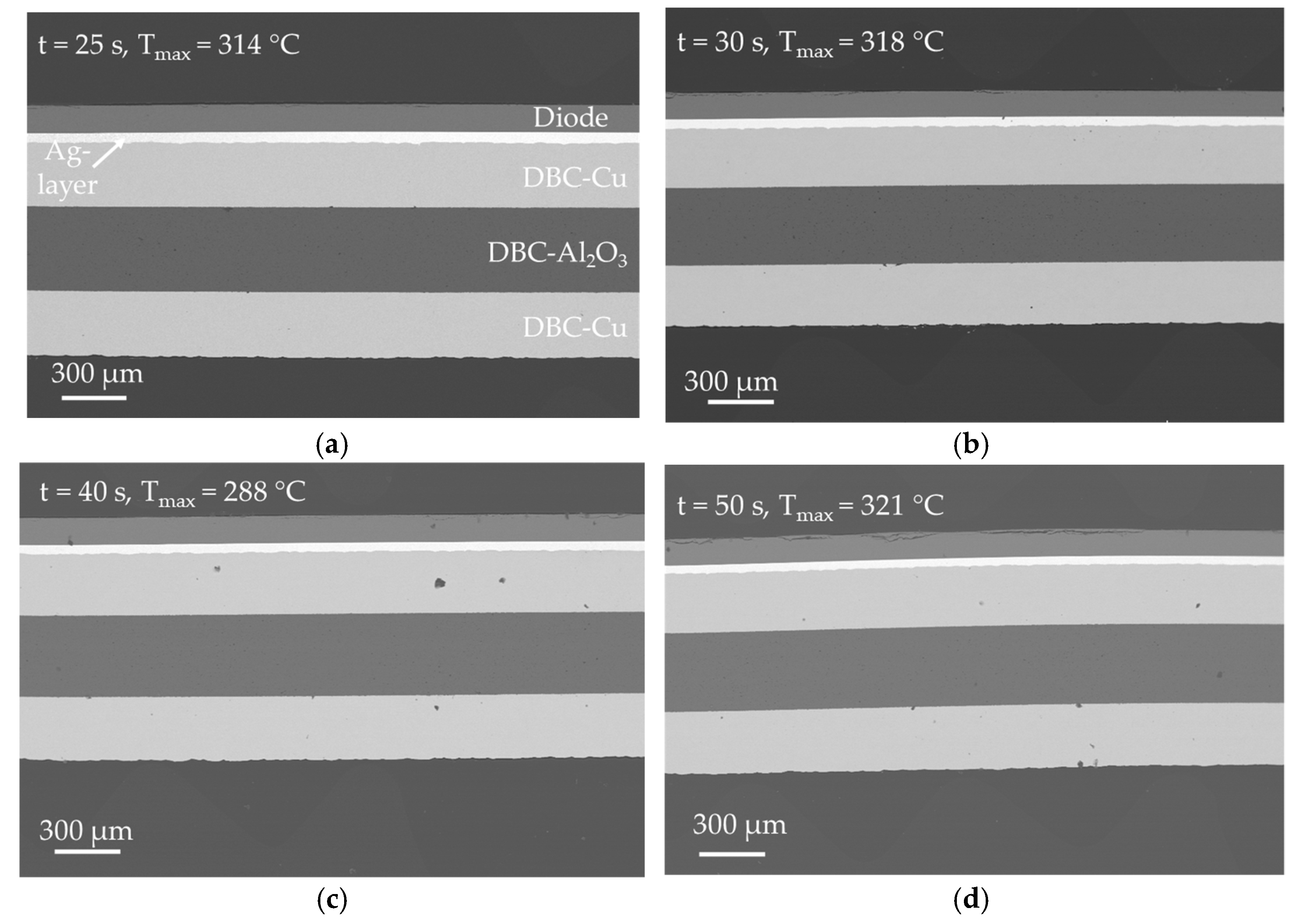

In

Figure 11, SEM images of the samples, which were produced at a bonding pressure of

p = 20.0 MPa (experimental series 1 in

Table 3) are shown. This value was selected as starting point of investigation because a bonding pressure between 20.0 MPa ≤

p ≤ 30.0 MPa is common in current industrial silver sintering processes for die-attach applications. The samples show a very good bonding between DBC substrate, silver layer and diode. The bond interface between DBC substrate and silver sintered layer as well as diode and silver sintered layer is free of defects or voids and the connection between the two components appears to be very firm. Likewise, the densification of the silver sintered layer appears to be very high. Based on the images, no difference in densification of the layers can be observed as a result of the different bonding times or the measured maximum temperature. In addition, almost no defects are visible in the DBC layers, which could be attributed to the bonding process. A few defects can be observed in the copper layers of the DBC substrates, especially in

Figure 11c, but in terms of distribution and size, they do not allow any conclusion to be drawn about a bond process-related formation. Several cracks on top of the diodes are likely the result of the high bonding pressure and the direct contact of the hard ceramic punch and the diode in the bonding process. The damage to the chips is particularly evident in

Figure 11d.

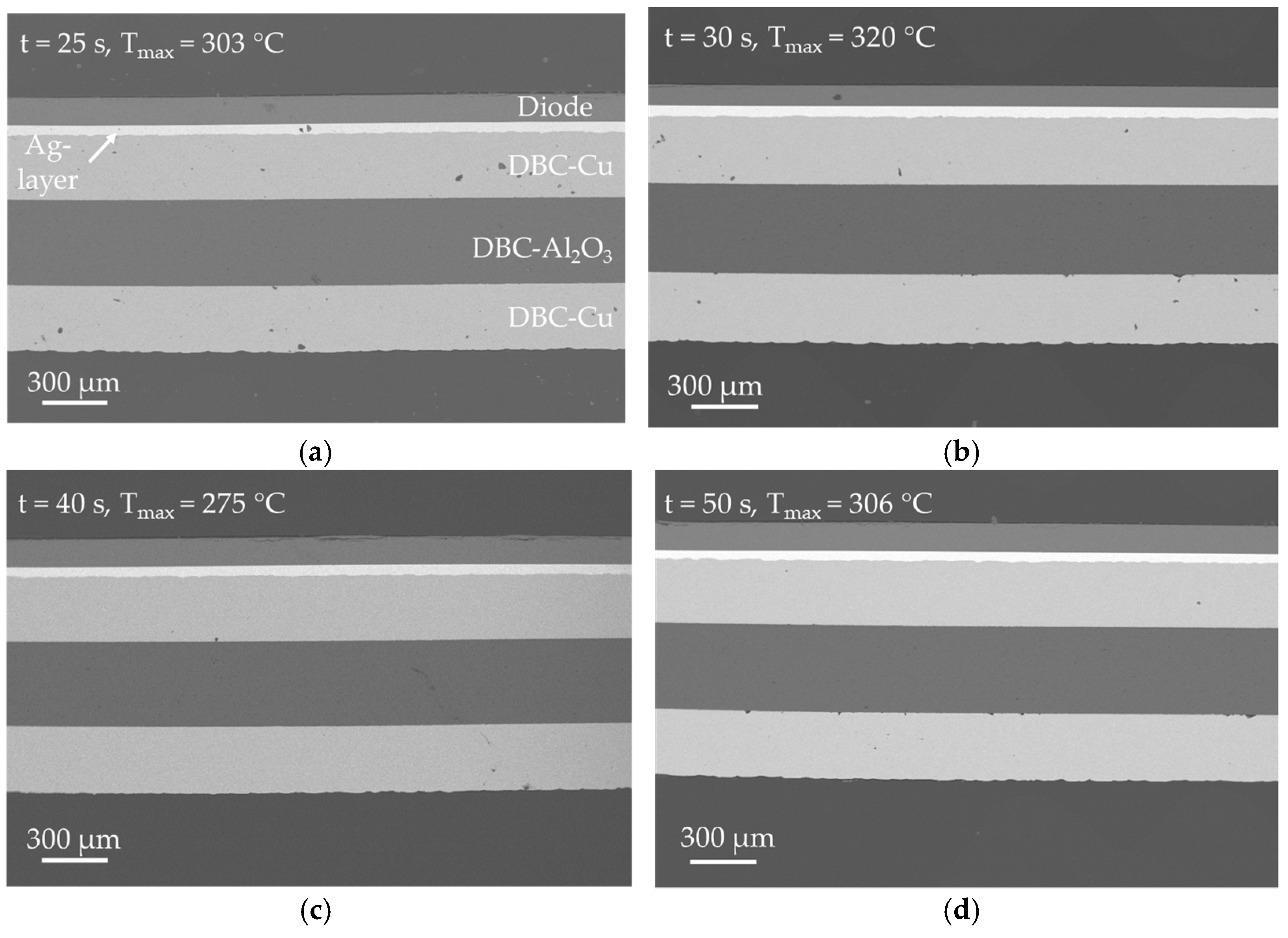

Cross-sectional SEM pictures of the samples, which were produced with a bonding pressure of

p = 10.0 MPa (experimental series 2 in

Table 3), can be seen in

Figure 12. From the images, an excellent bond between the DBC-Ag layer and the diode can be determined for all samples. The densification among all sintered layers in this figure is very high and can be compared to the samples from this experimental series 1 which were produced at a bonding pressure of

p = 20.0 MPa. In contrast, it is noticeable that a larger number of defects can be observed in the copper layers of the DBC substrate in the

Figure 12a,b. Since the number of defects is much less in

Figure 12c,d, which are the samples that were bonded for an even longer time at almost the same temperature, it is assumed that these defects were already present in the DBC substrate before bonding. It is also possible, that the sample was contaminated prior to the SEM analysis and the black dots are dust particles. Furthermore, a few cracks on the diode surface can be observed in

Figure 12c. It becomes evident, that the number of cracks is much lower, in comparison to the samples that were bonded at

p = 20.0 MPa. This shows, that a reduction of bonding pressure is beneficial with regard to production safety and quality. A more detailed analysis of the cracks is given later in this section.

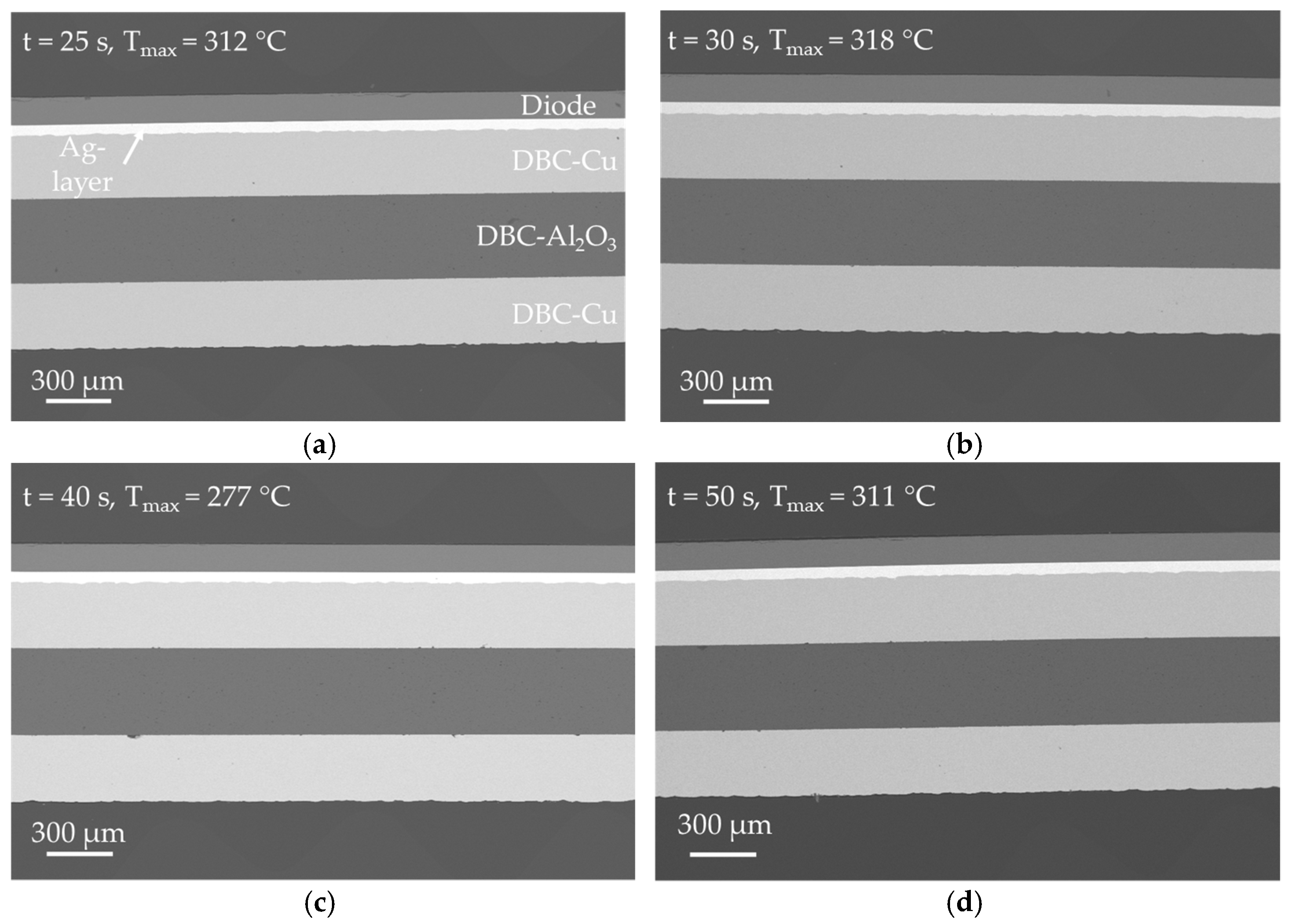

SEM analysis of the samples in

Figure 13 shows that a bonding pressure of

p = 5 MPa is already sufficient to produce high quality bonds between DBC substrate and diode. The morphology of the bond layers is identical to the previously analyzed samples and the bond to the diode as well as the DCB-Cu-layer is very well established. Several defects can be observed in

Figure 10c at the interface between DBC-Al

2O

3 and the bottom DBC-Cu layer. However, these are presumably a result of the manufacturing process of the DBC substrate. Almost no cracks in the diode could be found for the samples bonded at

p = 5 MPa.

Figure 14 shows a more detailed analysis of the bond zone of the samples from all three experimental series that were bonded for

t = 40.0 s according to

Table 3. In

Figure 14a,c,e, zoomed-in images of the layer system Diode-silver-DBC-Cu of the sample are shown. The samples were selected because the respective measured temperatures during the experiments were the lowest (

t ≈ 280 °C) and thus closest to the desired bonding temperature range of 230 <

TS ≤ 350 °C. As stated before, for all these samples a very good bonding between the diode and the silver sinter layer can be observed. For all three samples, the thickness of the silver sintering layer is

dAg = 44 µm. With regard to morphology and microstructure of the three silver sinter layers, they appear to be widely identical. However, for the samples bonded at

p = 20.0 MPa (

Figure 14a) and

p = 10.0 MPa (

Figure 14c), several cracks are visible on the diode’s top side, which is not the case for the sample bonded at

p = 5.0 MPa (

Figure 14e) where only a single small crack can be observed. Therefore, a bonding pressure of

p = 5.0 MPa is sufficient for inductive bonding with the silver sinter paste. By applying this very low bonding pressure, strong and defect-free bonds can be produced and the risk of damaging to the semiconductor components in the bonding process is reduced.

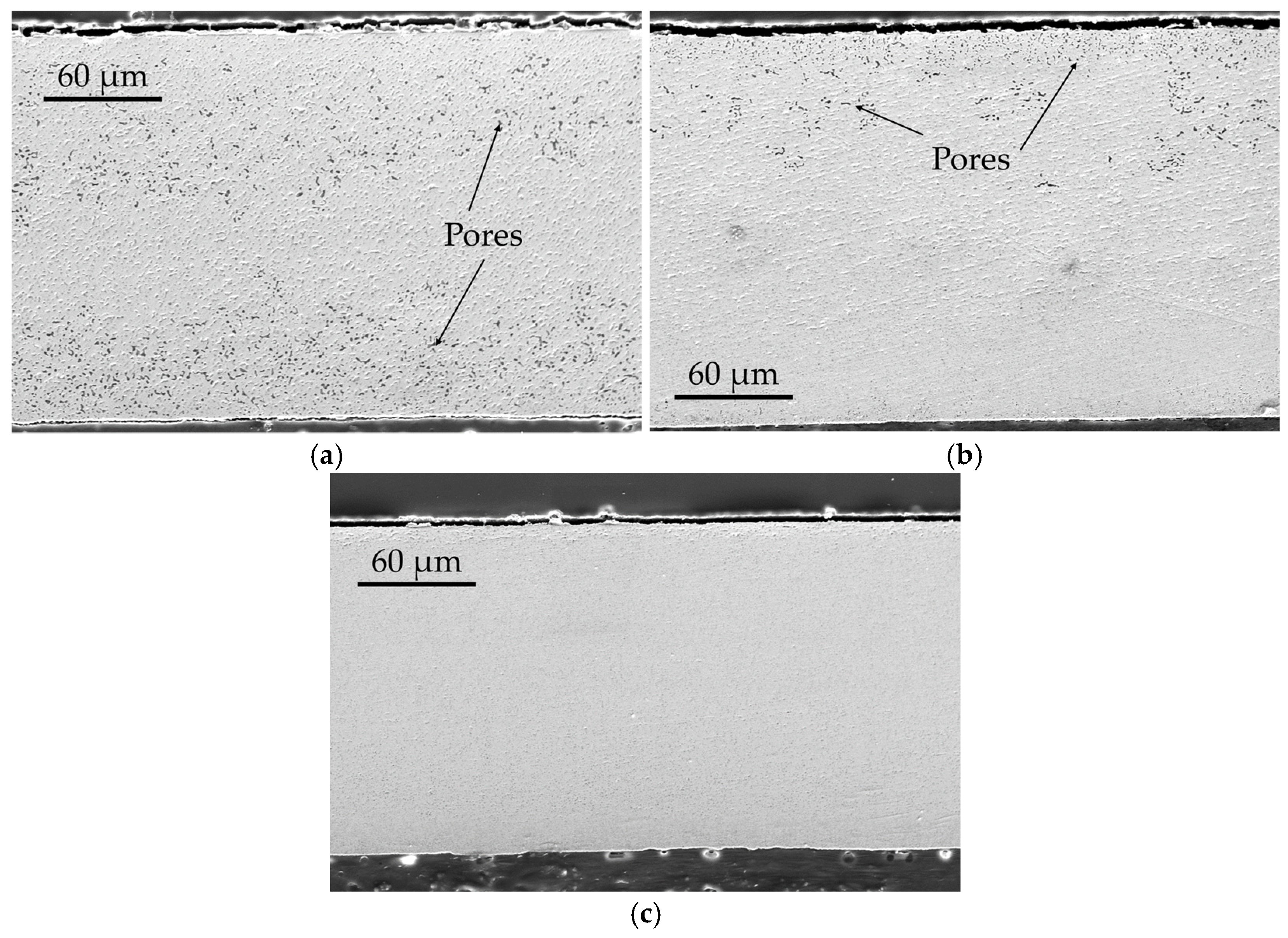

A detailed analysis of the silver sinter layers of the samples is given in the SEM images in

Figure 14b,d,f. It is clear that the densification is very high for all three samples. A certain residual porosity can be observed, but the overall structure and appearance of the layers is very homogeneous, as larger pores cannot be detected. Also, the investigations show that the temperature inhomogeneity during the heating process reported in section 3.3 has no impact on the silver layer morphology, because all investigated samples had an identical appearance throughout the whole cross sections. A more precise quantitative analysis of the layer porosity is to be carried out by means of focused ion beam (FIB) preparation and subsequent SEM analysis in future investigations. Additionally, the pictures prove that the interface between silver layer and diode is defect-free and the two components are tightly bonded. With regard to the very low bonding times and pressures as well as the very high densification of the sintered silver layers, it can be assumed that there is a positive effect on the sintering of the particles with each other as well as to the DBC substrate and diode because of the inductive heating method.

Furthermore, the detached sintered silver bars, which were previously examined by LaTIMA (

Table 6), were subsequently analyzed by means of SEM.

Figure 15 shows the SEM images of one LaTIMA sample for each annealing temperature. From the figures, it can be seen that the sample which was thermally treated at

T1 = 250 °C (

Figure 15a) exhibits a clearly visible residual porosity, which is particularly pronounced in the upper and lower thirds of the layer. In the center, there is a comparatively dense zone with hardly any pores to observe. However, the sample is already highly densified. The sintered sample, which was treated at

T2 = 350 °C (

Figure 15b), shows even less residual porosity, with a few pores primarily agglomerating in the upper third of the sample. Finally,

Figure 15c shows, that the sample which was treated at

T3 = 450 °C, no longer shows any visible pores. With increasing temperature, a higher densification of the sintered structure can be observed, although a sufficiently high densification of the structure can already be observed at a sintering temperature of

T1 = 250 °C.

In section 3.1, the results of the LaTIMA investigations were discussed. For the discussed samples, a decrease in thermal conductivity with increasing sintering temperature could be observed, which is against expectation. With the recently presented SEM analyses of the detached silver sinter layers, a more elaborated discussion of the results is possible. Generally, increasing the densification of a metallic sinter structure is accompanied by an increase in thermal conductivity of the structure. The reason for this is that poorly sintered structures contain gas inclusions which have, compared to metals, a lower thermal conductivity. Thus, as the densification of a sintered structure increases, the pore fraction decreases and the thermal conductivity should increase similarly. This correlation is not true for the samples investigated in this paper. In order to explain this effect, the mean free path of gas molecules becomes important, which is defined as the average distance a molecule travels in a volume until it collides with another molecule and thus exchanges thermal energy. As the pores become smaller into the nanoscale (d < 100 nm) during the sintering process, the mean free path of the gas molecules is greater than the effective space (the pore) in which the gas molecule is confined. This leads to a significant decrease in the number of gas molecule collisions with each other during a constant period and consequently to a strongly reduced thermal conductivity of the gas in the pore. As a result, the overall thermal conductivity of the nano-porous sintered structure decreases. This effect is known as the Knudsen effect and can be used specifically to produce highly heat-insulating materials [

29,

30].

It is possible that this effect is also present in the sintered metallic structures studied here. As the densification of the silver sinter layer progresses, the pores in it become smaller, but there is no complete densification of the sinter structure because there is no liquid metal that can enter the pores and seal them as the sintering process takes place without melting the silver particles. Instead, the particles sinter only by solid-phase diffusion, so that a certain residual porosity remains even after a long time of sintering. Due to the very small dimensions of the pores, they are no longer visible in the SEM images in the

Figure 15a–c. However, the thermodynamic influence of these very small pores on the overall thermal conductivity can be clearly seen from the LaTIMA measurements. Since a low thermal conductivity of the sintered layers is not desirable, this aspect of the sintering of silver particles during bonding requires further investigation and optimization.

3.6. Function Test

The results of the function tests by means of block voltage measurement are shown in

Table 7. The majority of the diodes endured the inductive bonding process without damage. For 10 out of 12 samples, an average leakage current of

IL_MW = 271 nA was measured, which corresponds to a failure-free functionality of the diodes. For sample diode 5, the measured leakage current is

IL = 5,000 nA. According to the measurement norm, this value is still below the limit for defective components (

IL_crit = 25,000 nA), but it is notably high compared to the other samples. It is therefore assumed that this sample is also defective.

Diode sample 7, on the other hand, is clearly defective: a leakage current of

IL = 30,000 nA was measured for it. With regard to the bonding process parameters for this sample (

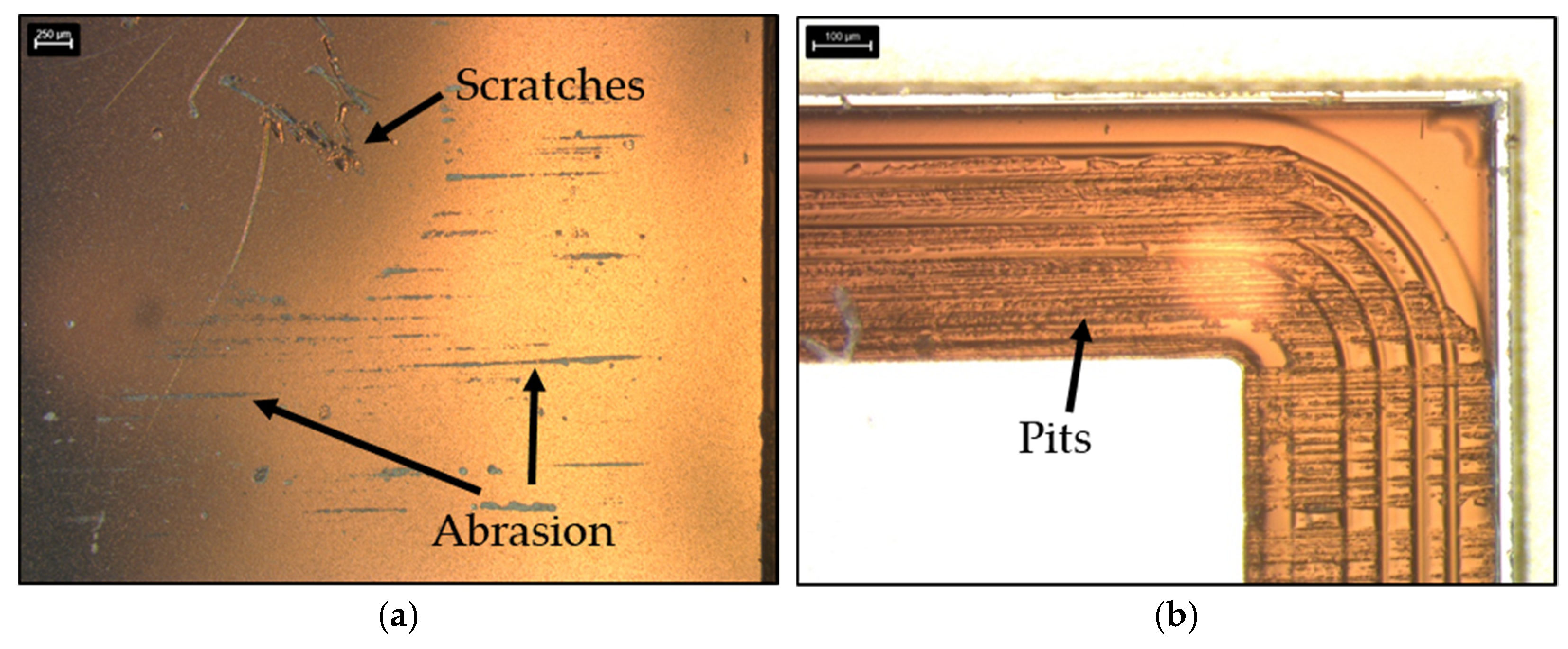

Table 7), no correlation can be found between them and the cause of the damage. Neither the bonding time, nor the bonding pressure or the measured diode surface temperature during the bonding process were exceptional high. It is therefore unlikely that the thermal-electromagnetic stress on the diode in the bonding process led to the failure. For this reason, this sample was subjected to further optical microscopic investigations. The optical microscope analysis of the diode’s top metal revealed numerous damages (

Figure 16a). In addition, the polyimide guarding at the frame of the diode was also damaged and deformed (

Figure 16b). All these damages were probably caused by the contact of the SiN punch with the diode during the bonding process. The mechanical impact of the punch on the diode surface presumably damaged the polyimide guarding to such an extent that functionally critical damage to the diode occurred.

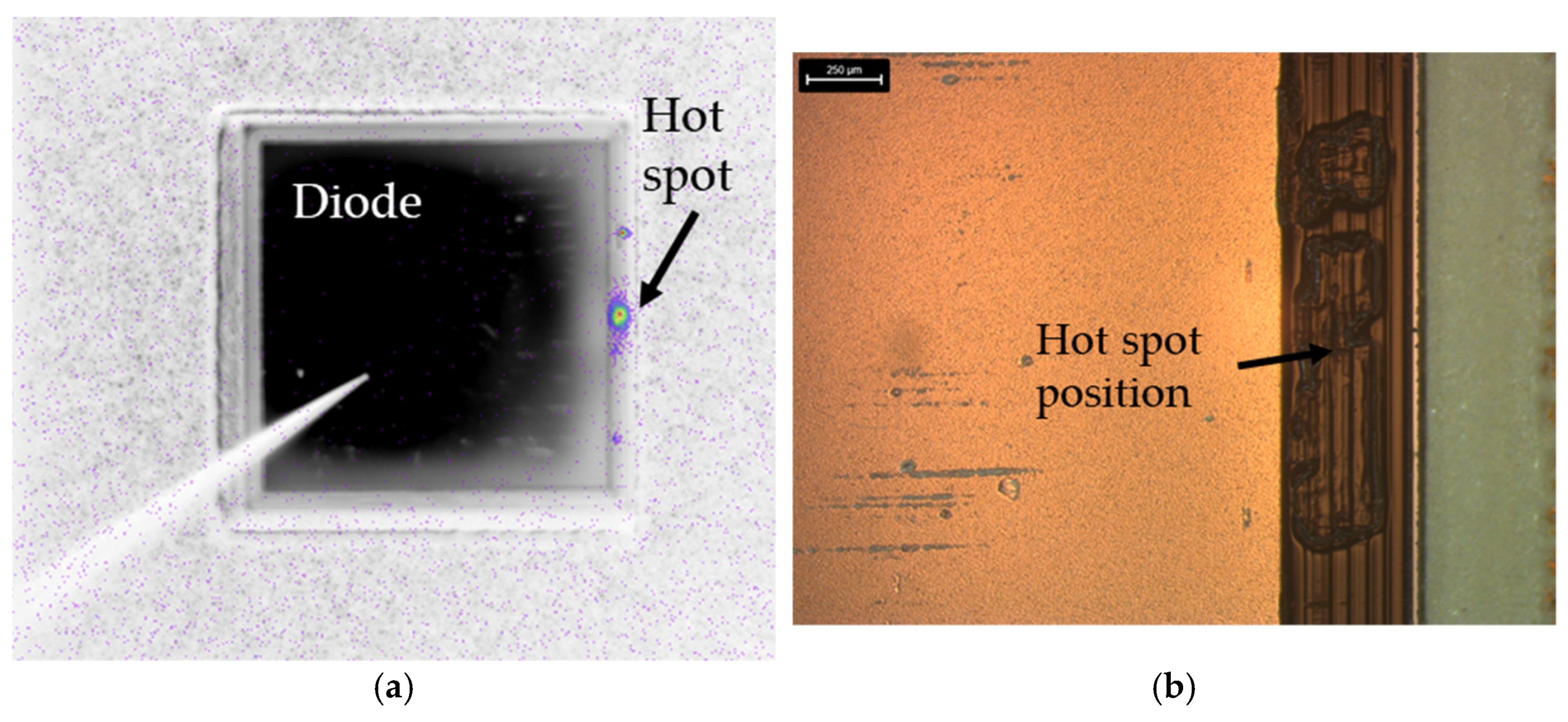

Lock-in thermography is a non-destructive testing method for locating damaged areas of a defective diode.

Figure 17a shows the results of the investigation for the sample diode 7 according to

Table 7. In this test method, a pulse current is applied to the diode and it is observed by means of a thermal camera. At the diode’s damaged locations, the leakage current flow is very high and as a result, the temperature increases significantly at these locations due to the Joule effect. During the investigations, a hot spot was detected on the right side of the sample diode. The optical microscopic analysis of the corresponding hot spot location is depictured in

Figure 17b. There, a pit in the polyimide guarding can be clearly observed. Like mentioned before, this pit was presumably caused by the mechanical impact of the SiN punch on the diode in the bonding process.

The results of the function test of the inductively bonded diodes showed that the inductive bonding process did not result in any damage to the semiconductor components. Instead, the observed damage could be attributed to the mechanical impact of the ceramic punch on the diodes’ surface. In future experiments, this problem will be overcome by technological adjustments to the test rig, for example by inserting a buffering polymer film between diode and ceramic punch. Therefore, there are no indications that the inductive bonding process itself did cause any damage to the diodes. Furthermore, evidence has been provided that this technological approach is potentially suitable for industrial application.