1. Introduction

With the acceleration of industrialization, industrial wastewater has tended toward increasing complexity [

1], often containing multiple heavy metals, multiple inorganic substances, and heavy metal–organic micropollutant complexes. In particular, the presence of heavy-metal dye [

2,

3,

4,

5] and heavy-metal–heavy-metal [

6] complexes have been widely reported in industrial wastewater. However, the management of bisphenol A (BPA)–dye composite wastewater has only been addressed recently. BPA detected in dye wastewater is derived from the conversion of the parent chemicals, including flame retardants used in certain fabrics and various chemicals in textiles used as coatings inside containers [

7]. BPA was detected in denim-dyeing wastewater and in textiles [

8]. This result can be attributed to the fact that BPA is often added as a plasticizer and antioxidant in the production of fabrics. Although BPA is found in low concentrations, it is biotoxic and carcinogenic and can therefore threaten human health even at low levels. In addition, because of possible synergistic effects, contamination from dye–BPA complexes is far more dangerous than that from single compounds [

2]. Conventional treatment processes in wastewater-treatment plants are not efficient in removing endocrine disruptors from composite wastewater for their discharge into natural water bodies. Therefore, the development of treatment technologies that can simultaneously remove multiple contaminants from wastewater is the only way to deal with today's complex wastewater systems and also a major trend in the development of wastewater-treatment technologies.

Adsorption technology occupies an extensive market share in the field of water treatment due to its simplicity, efficiency, and economy. Compared with traditional adsorbent materials such as chitosan and activated carbon, synthetic nanofiber materials possess excellent properties, such as large specific surface area, high porosity, excellent mechanical properties, adjustable structure, and the ability to carry other functionalized modified groups, making them very promising adsorbents. However, electrospun nanofiber membranes prepared from a single polymer usually exhibit poor separation performance. Therefore, functionalized modifications of the spinning material or of the electrospun membrane surface are used to facilitate the separation of contaminants. In particular, membrane-modification techniques have been shown to be an effective approach in improving membrane performance [

9]. Thermoplastic polyurethanes (TPUs) are excellent molding materials, and their application as spinning materials can enhance the mechanical strength of membranes. Modified nanofiber membranes exhibit excellent adsorption rates and capacities due to their laminar structure, and functional modifications of these layers can provide more adsorption sites for specific contaminants.

Polyethyleneimine (PEI), a polyamine polymer rich in repeating units and secondary amine groups [

10], is often employed in synthetic materials because of its dendritic morphology and water-soluble properties [

11]. Modifying a membrane by adding PEI can thus enrich the surface of the material with amino functional groups, consequently enhancing the effect of removal of pollutants, especially negatively charged anionic dyes, heavy-metal ions, etc. [

12]. For instance, core–shell Fe

3O

4@SiO

2 nanoparticles have been modified with PEI, enabling their maximum adsorption capacity for methyl orange (MO) and Congo red (CR) to reach 231.0 mg/g and 134.6 mg/g, respectively, under neutral conditions. In contrast, their adsorption capacity for methyl blue (MB) was relatively low [

13]. In addition, graphene oxide aerogels cofunctionalized with polydopamine (PDA) and PEI which were rapidly synthesized at room temperature and displayed effective adsorption of the anionic dyes MO (202.8 mg/g), amaranth red (196.7 mg/g), and organic solvents [

14]. This suggests that PEI and dopamine hydrochloride (DA) can be incorporated into TPU NFMs as modifying monomers to enhance the adsorption of anionic dyes. Some of the wastewater-treatment methods developed to date are predominantly effective for the adsorption of monomeric dyes or BPA [

15,

16]; however, a few studies have considered more complex contamination systems, especially for dye–BPA binary complexes.

Therefore, our aim was to develop a highly efficient adsorbent with a high adsorption capacity for BPA–dye composite wastewater and to clarify its adsorption mechanism. Accordingly, we grafted low-cost green PEI and DA coatings onto TPU nanofiber membranes using simple electrostatic-spinning and chemical codeposition methods, achieving efficient synergistic adsorption of BPA and dyes. Based on our previous study, which confirmed the excellent adsorption performance of PDA/PEI-TPU NFMs on BPA and dyes separately, we optimized the preparation conditions for PDA/PEI-TPU NFMs further by employing a dye–BPA composite wastewater system. Subsequent investigations considered the adsorption performance of these PDA/PEI-TPU NFMs for dye–BPA composite wastewater using adsorption kinetics and adsorption-isotherm experiments. We also analyzed the interaction between BPA and various dyes to determine the adsorption mechanisms in dye–BPA composite solutions.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Chemicals and materials

We used all the chemicals as obtained, without further purification. We purchased BPA (99%), PEI (99%), and DA (99%) from J&K Scientific Co., Ltd. (Beijing, China). The TPU powder was supplied by BASF Co., Ltd. (Shanghai, China). We purchased dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO, analytical purity) from Tianjin Yongda Chemical Reagent Co. (Tianjing, China). We obtained N, N-dimethylformamide (DMF, C3H7NO), acetone (C3H6O, AR), aqueous hydrochloric acid (HCl, AR), sodium hydroxide (NaOH, AR), CR (C32H22N6Na2O6S2, AR), and Eosin Y (C20H6Br4Na2O5, AR) from Chuandong Chemicals Co., Ltd. (Chongqing, China). We purchased sunset yellow (SY) (C16H10N2Na2O7S2, AR) from Shanghai Bide Pharmaceutical Technology Co. (Shanghai, China). We obtained tris(hydroxymethyl) aminomethane (C4H11NO3, AR) from Guangdong Guanghua Technology Co. Ltd. (Guangdong, China).

2.2. Characterization and measurement methods

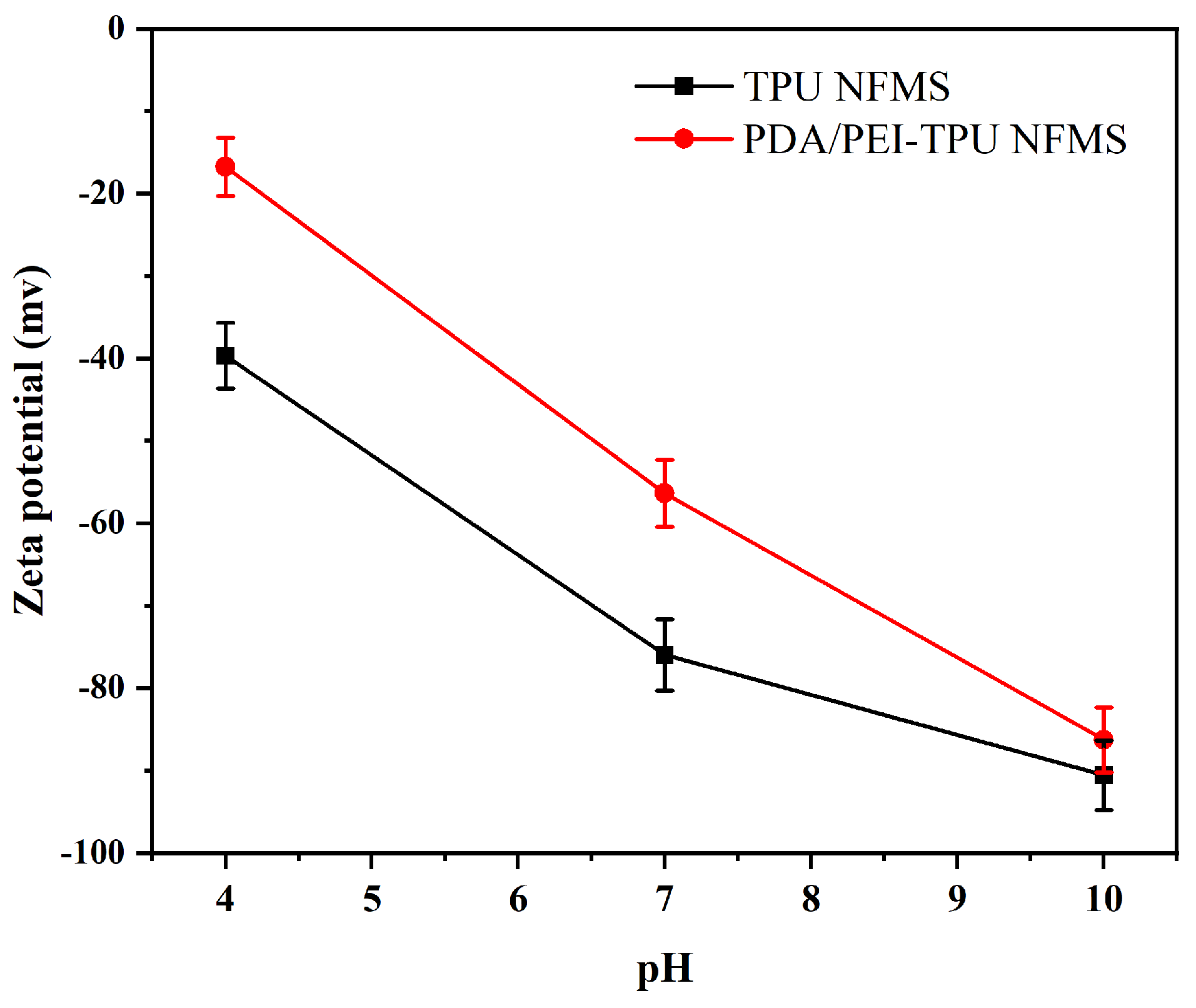

We measured the surface charge of the TPU NFMs and the PDA/PEI-TPU NFMs at pH 4, 7, and 10 using a zeta-potential meter (SurPASS, Austria). We measured the concentrations of the dyes quantitatively using an ultraviolet spectrophotometer (UV-vis-3150, Kyoto, Japan) from 800 to 200 nm, using deionized water for the background correction.

2.3. Optimization of synthesis conditions

The material-preparation processes have been reported in previous research publications from our group [

17,

18]. The ratio of the reaction monomers (DA and PEI) and the codeposition time affect the amount of PDA/PEI co-deposited layers that can be grafted onto the surface of a TPU NFM, which in turn affects the adsorption performance of the membrane. Therefore, the concentration of DA was fixed at 2 g/L, and the mass ratio of the two in the solution was controlled by varying the concentration of PEI. We used the following six concentration ratios: DA:PEI = 2:0, 2:0.5, 2:1, 2:1.5, 2:2, and 2:3 (g/L: g/L). In addition, the effect of five deposition times (12, 24, 36, 48, and 60 h) on the adsorption performance of the membranes was also observed. The effect of these two factors on the adsorption performance of the modified membranes was evaluated by the removal efficiency [Eq. (1)], using CR–BPA composite wastewater (200 mg/L CR and 50 mg/L BPA) as the target pollutant. The adsorption experiments were conducted as follows: First, 20 mg of TPU NFMs were accurately weighed and added to 20 mL of the CR–BPA composite wastewater system, and the pH remained unchanged to ensure neutrality. The composite wastewater was then shaken at room temperature for 24 h to reach adsorption equilibrium, and the residual concentrations of CR and BPA were determined by UV-vis spectrophotometry. We define the resulting removal efficiency as follows:

where

C0 represents the initial absorbance, and

Ce represents the absorbance after adsorption equilibrium.

2.4. Kinetic adsorption

To determine the adsorption capacity of adsorbents for dyes while taking into account the actual pH in industrial-dye wastewater, three sets of binary complex wastewater systems were selected for adsorption kinetics experiments: CR–BPA (pH = 7), SY–BPA (pH = 2), and EY–BPA (pH = 4).

The specific experimental procedure was as follows. First, 0.1 g of dried PDA/PEI-TPU NFM adsorbent was added to 100 mL of the binary composite wastewater system to produce a dosage of 1 g/L of adsorbent. The concentration of BPA for all three composite wastewater systems was 50 mg/L, that of CR was 300 mg/L, and those of SY and EY were 100 mg/L each. The wastewater containers were then shaken in a thermostatically controlled shaker at room temperature at 150 rpm, and samples were collected at regular intervals. Both SY–BPA and EY–BPA binary effluents were diluted five times, following which the concentrations of the remaining contaminants were determined. For these experiments, three sets of parallel samples were set up and the results were obtained by averaging the outcomes of each experiment. In addition, to compare the different adsorption capacities of the adsorbent in the monomeric and in the binary wastewater system, the monomeric adsorption experiment was conducted in the same way. To further investigate the adsorption process, the experimental data were fitted with pseudo-first-order and pseudo-second-order kinetic models using the following formulas:

Pseudo-first-order model:

Pseudo-second-order model:

Herein, Qe (mg/g) is the adsorption capacity at equilibrium and Qt (mg/g) is the adsorption capacity at time t. The quantity k1 (h−1 ) is the pseudo-first-order model rate constant and k2 [g/(mg·h)] is the pseudo-second-order model rate constant.

2.5. Equilibrium isotherms

We found remarkable differences in the adsorption capacities of the PDA/PEI-TPU NFMs for CR, SY, and EY in the monomeric system [

17,

18]. In order to more quantitatively analyze the adsorption patterns of the PDA/PEI-TPU NFMs for the dye–BPA binary composite wastewater system, a gradient setting was applied to the dye and BPA concentrations. As shown in

Table 1, the concentrations of BPA and EY were within the range 0–100 mg/L, and the concentrations of SY and CR were within the range 0–200 mg/L and 0–350 mg/L, respectively.

The experiment was conducted in three parts as follows: First, 20 mg of dried PDA/PEI-TPU NFMs were added to 20 mL of each of the three binary composite contaminant systems—CR–BPA (pH = 7), SY–BPA (pH = 2), and EY–BPA (pH = 4)—to achieve a dose of 1 g/L of adsorbent. Subsequently, the binary composite wastewater systems were shaken in a thermostatic shaker at room temperature at 150 rpm for 24 h. After attaining adsorption equilibrium, the SY–BPA and EY–BPA composite solutions were diluted five times, and the remaining contaminant concentrations were determined using a UV spectrophotometer. The adsorption capacity was calculated using equation (4):

where

m (g) is the weight of the membrane,

C0 (mg/L) is the initial concentration,

Ct (mg/L) represents the residual concentration at the time interval

t, and

V (L) is the volume of the dye solution.Three sets of parallel tests were conducted simultaneously to determine the mean of each set of data. In order to mitigate errors caused by the material and to compare the data for the monomeric and binary wastewater systems, the adsorption experiments were conducted for the monomeric wastewater system under the same conditions as that used for the binary wastewater systems.

In order to compare different adsorption capacities of the monomeric and binary systems in a more intuitive way, the adsorption capacity ratio (

Rq) was also analyzed using equation (5):

where

Qe,i is the adsorption capacity of pollutant

i in the binary composite wastewater system, and

Q0,i is the adsorption capacity of the same initial concentration of pollutant in the monomeric wastewater system.

3. Results and discussion

3.1. Zeta-potential analysis

Our group previously reported the successful synthesis of TPU NFMs and PDA/PEI-TPU NFMs [

17,

18]. In this study, the zeta potentials of both the TPU support membrane and PDA/PEI-modified membrane was measured to determine the type of charge carried by the materials under different pH levels, as this parameter is pertinent to the electrostatic adsorption between the materials and the contaminants. The zeta potentials of both the original TPU membrane and the modified membrane vary with the pH of the electrolyte solution, as shown in

Figure 1. In the measured range (pH = 4–10), the zeta potentials of both the support and modified membranes decreased with increasing pH. In other words, the zeta potential was higher under acidic conditions than under alkaline conditions. At pH = 4, the maximum zeta potentials of −40.06 and −18.11 mV were achieved for the original TPU and PDA/PEI-modified NFMs. This can be attributed to the fact that the TPU material possesses ester, ether, and formic-acid ester bonds on its surface, which are deprotonated in weakly acidic, neutral, and alkaline environments, resulting in a negative surface charge. Following modification, the PEI carries a positive charge due to protonation under acidic conditions because it contains rich imine groups and primary amino groups. The amino radical NH

2 acquires H

+ to form NH

3+, which increases the zeta potential of the modified membrane [

19]. This property also aids in the removal of negatively charged contaminants.

3.2. Optimization of synthesis conditions

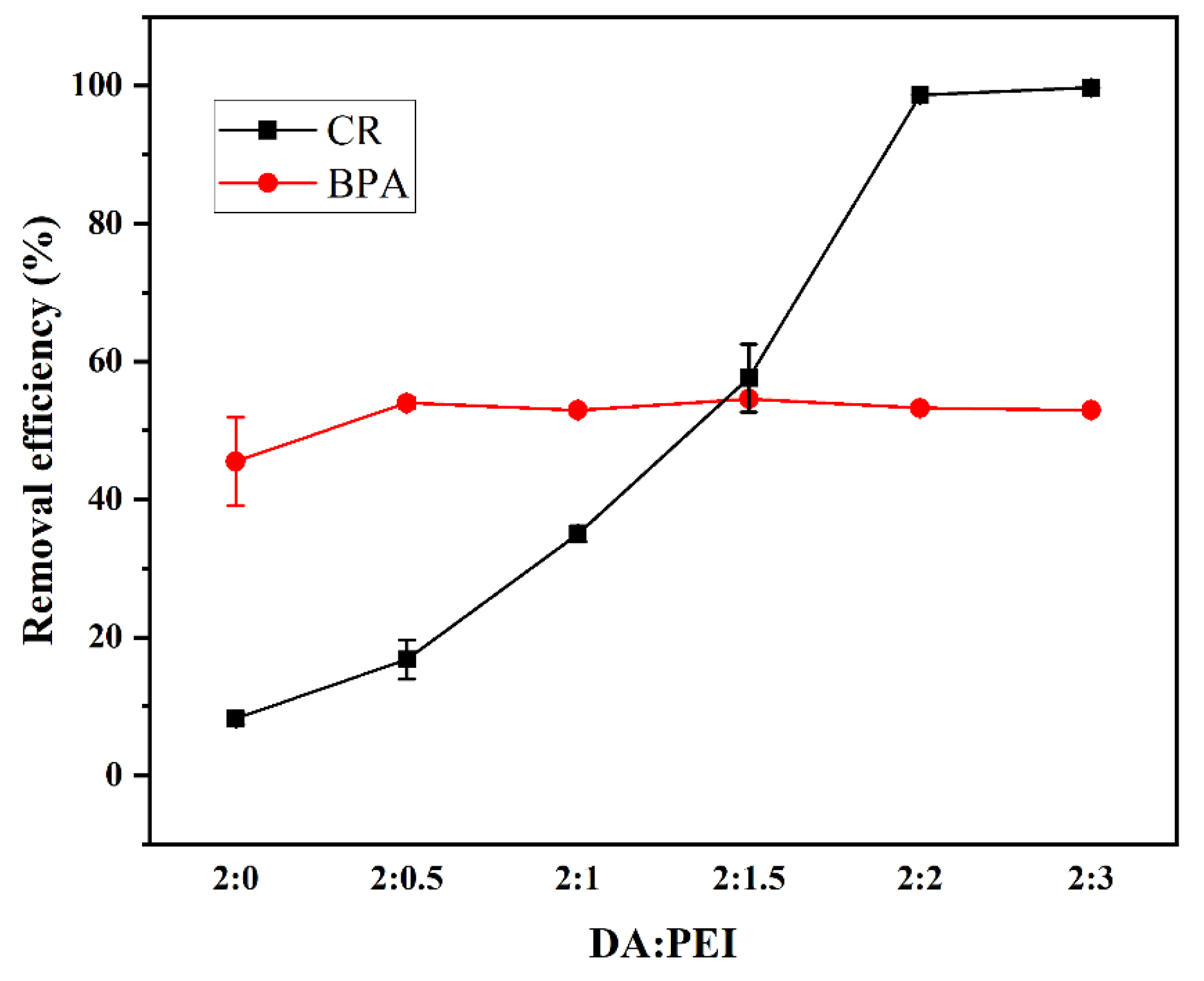

3.2.1. PEI/DA monomer ratio

For the CR monomeric system, the adsorption efficiencies increased gradually with the mass ratio of PEI to DA, as shown in

Figure 2. When the mass ratio is 2:2, a removal efficiency of approximately 100% can be achieved. This occurs because the amino groups in the PEI are positively charged by protonation under acidic conditions, which changes the charge distribution on the membrane surface. In turn, CR is adsorbed onto the membrane surface due to electrostatic effects [

20,

21,

22]. However, the amount of PEI grafted onto the membrane surface did not substantially promote or inhibit the adsorption of BPA, and its removal rate essentially remained stable at approximately 53%. Thus, it is possible to remove BPA and dyes simultaneously with PDA/PEI-TPU NFMs. Owing to the fact that an excessive PEI content would reduce the elasticity and tensile properties of the membrane, in conjunction with the observation that the CR removal efficiency no longer increases substantially at the mass concentration of 2:3, we selected the ratio DA/PEI = 2:2 as the optimum concentration of reaction monomers.

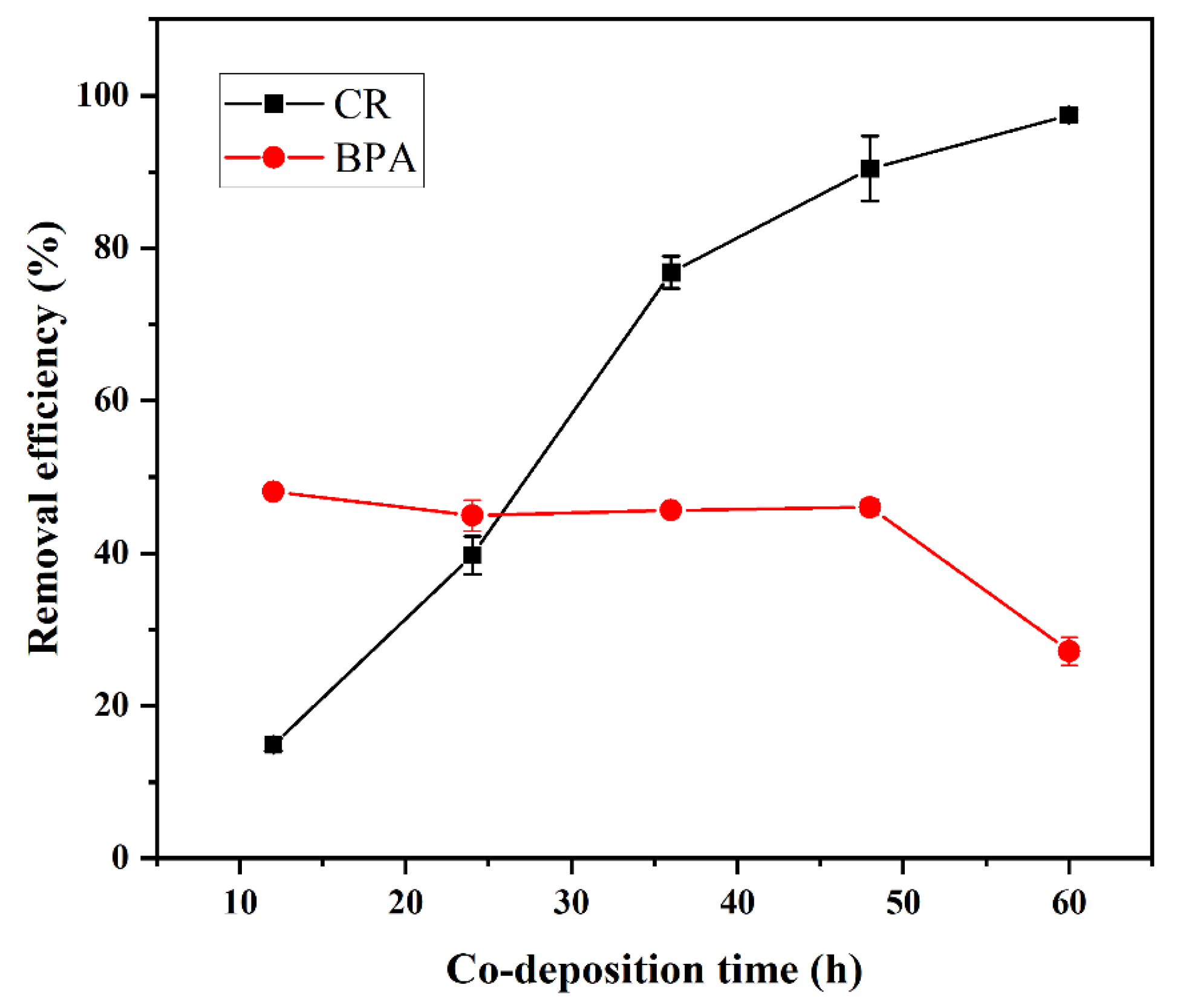

3.2.2. Effect of deposition time

The adsorption efficiencies for BPA and CR at different deposition times are shown in

Figure 3. The removal efficiency of CR increased sharply during the first 12–48 hours, whereas the removal efficiency of BPA remained relatively stable. As the deposition time exceeded 48 h, no remarkable increase was observed in the removal efficiency of CR; moreover, the removal rate of BPA tended to decrease. This result could be attributed to large particle aggregates blocking the membrane pores and preventing the BPA adsorption sites on the membrane surface from functioning. The optimal material preparation and deposition time is thus 48 h.

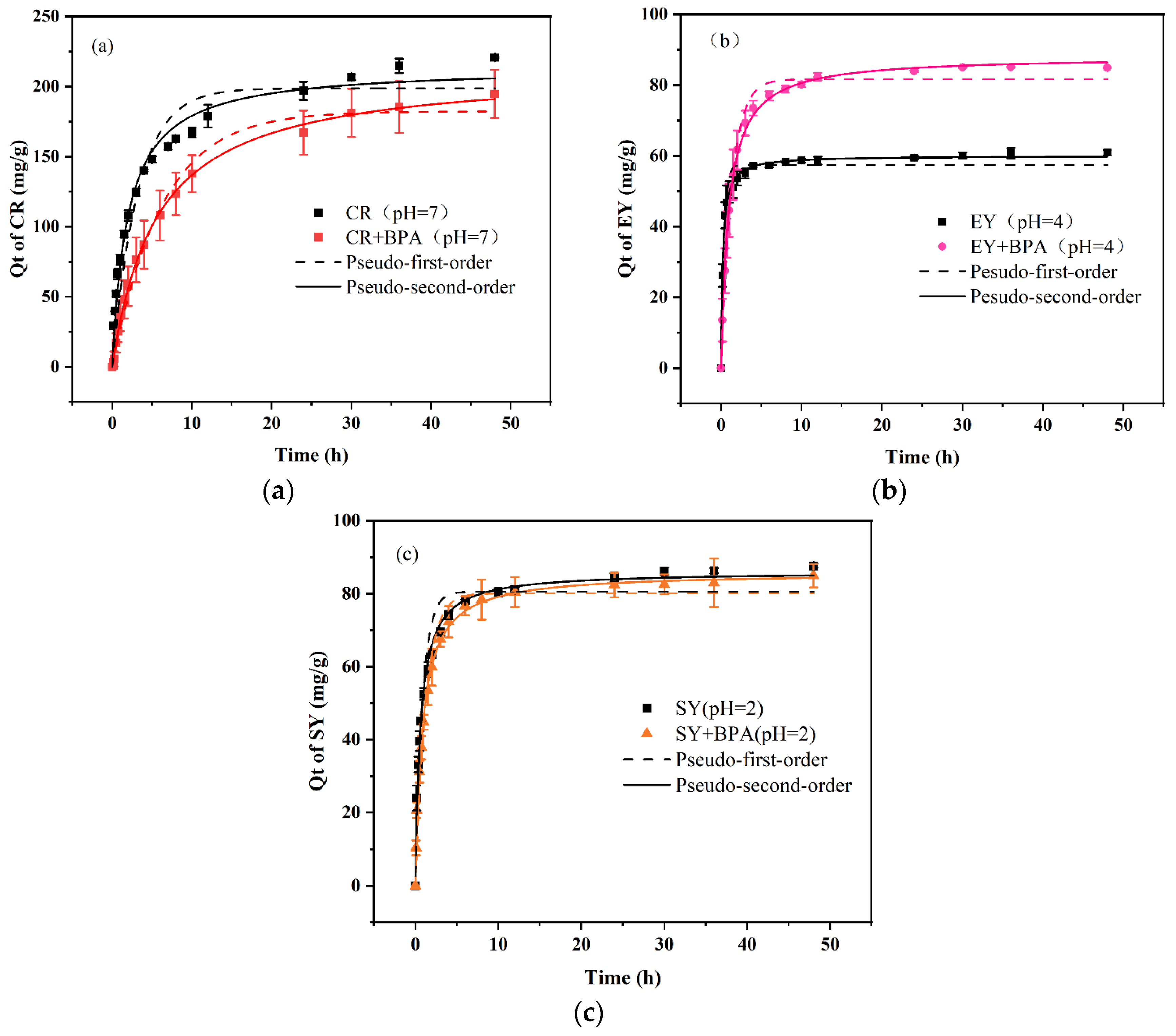

3.3. Adsorption kinetics

The adsorption capacities of the PDA/PEI-TPU NFMs for the three anionic dyes and BPA in both monomeric and binary wastewater systems as a function of time are shown in

Figure 4 and

Figure 5. The data and fitted curves for the adsorption capacity of SY in both the monomeric and the binary systems largely overlap, indicating that the presence of BPA does not affect the adsorption of SY. Similarly, the presence of SY does not affect the adsorption of BPA, as shown in

Figure 5(c). This demonstrates that the adsorption processes for SY and BPA are independent of each other. In contrast, the CR–BPA and EY–BPA binary wastewater systems exhibited adsorption processes that were markedly distinct from that of the SY–BPA binary wastewater system. The former exhibited an antagonistic effect, while the latter exhibited a synergistic effect. The presence of CR inhibited the adsorption of BPA, and the presence of BPA also reduced the adsorption capacity of CR. In contrast, EY and BPA each promoted an increase in adsorption capacity for the other. In particular, BPA substantially increased the adsorption capacity for EY. This can be explained by the adsorption force between the adsorbent and the dye.

The adsorption of SY depends on electrostatic interactions, which are related to the amino sites of the PEI in the PDA/PEI-TPU NFMs. In contrast, the adsorption of BPA depends on hydrogen bonding and on hydrophobic interactions, which are related to adsorption sites such as ether and ester bonds within TPU NFMs [

23]. Consequently, no competition exists between the two. In contrast, the primary adsorption mechanisms of CR are hydrogen bonding (occupying sites inside the TPU NFMs) and electrostatic adsorption (occupying amino sites on the surface layers), which possess the same adsorption sites for BPA. Thus, a competitive relationship exists between CR and BPA. In addition, the large molecular structure of CR may prevent BPA from entering the membrane pores, reducing the BPA adsorption capacity. In the EY–BPA binary wastewater system, BPA is a molecular compound in an acidic (pH = 4) solution. The –OH in its molecular structure undergoes weak interactions with the –COO– and C=O groups on the benzene ring of EY, which allows BPA to adsorb some of the EY in the form of bridging. Similarly, EY can adsorb some of the BPA by bridging, which promotes the adsorption of both.

After the adsorption had reached equilibrium, the experimental data were fitted with both a pseudo-first-order model and a pseudo-second-order model. These fits revealed that the pseudo-second-order model better describes the adsorption of dyes and BPA by the PDA/PEI-TPU NFMs in both monomeric and binary systems. In fact, all the coefficients of determination were exceeded R2 = 0.97, indicating that the pseudo-second-order model fitted the experimental data to an appreciable degree. The adsorption rates for CR and BPA decreased from 0.002 min−1 and 0.331 min−1 in the monomeric systems to 8.37 × 10−4 min−1 and 0.072 min−1, respectively, in the binary CR–BPA system. This demonstrates that when BPA and CR coexist in a wastewater system, they compete for adsorption sites, which greatly limits the adsorption rates. In contrast, in the SY–BPA and EY–BPA binary wastewater systems, the dyes and the BPA had a relatively subdued impact on each other’s adsorption rates. However, the adsorption rates of EY and BPA in the binary wastewater system were slightly lower than those in the monomeric system, decreasing from 0.079 min–1 and 0.269 min–1 to 0.012 min–1 and 0.086 min–1, respectively. The decrease in the adsorption rates of BPA was more substantial, indicating that there was indeed a bridging effect between EY and BPA. Two scenarios were likely to have occurred: either the EY occupied the amino sites on the surfaces of the PDA/PEI-TPU NFMs and then adsorbed the BPA by bridging, or bridging occurred between the EY and BPA before adsorption onto the membrane surface. In either case, the adsorption was slowed down by this bridging process. Overall, our experiments confirmed that the mutual presence of BPA with CR, SY, or EY in a binary wastewater system affected the adsorption performance, causing considerable differences.

Table 2.

Kinetic-model parameters for the adsorption of BPA and dyes onto PDA/PEI TPU NFMs in monomeric and binary systems.

Table 2.

Kinetic-model parameters for the adsorption of BPA and dyes onto PDA/PEI TPU NFMs in monomeric and binary systems.

| Contaminants |

Wastewater system |

Qe (exp)

mg/g |

Pseudo-first order |

Pseudo-second order |

|

Qe (mg/g) |

k1 (min−1) |

R2

|

Qe (mg/g) |

k2 (min−1) |

R2

|

| CR |

CR (pH = 7) |

220.67 |

182.25 |

0.160 |

0.989 |

214.30 |

0.002 |

0.983 |

| CR–BPA (pH = 7) |

192.69 |

198.75 |

0.307 |

0.939 |

213.31 |

8.37×10−4

|

0.998 |

| SY |

SY (pH = 2) |

87.60 |

80.52 |

1.123 |

0.943 |

86.07 |

0.019 |

0.993 |

| SY–BPA (pH = 2) |

84.92 |

80.07 |

0.792 |

0.975 |

85.83 |

0.013 |

0.994 |

| EY |

EY (pH = 4) |

60.91 |

57.46 |

2.732 |

0.966 |

60.02 |

0.079 |

0.997 |

| EY–BPA (pH = 4) |

85.08 |

81.62 |

0.747 |

0.989 |

88.15 |

0.012 |

0.997 |

| BPA |

BPA (pH = 2) |

21.73 |

21.49 |

4.082 |

0.991 |

23.42 |

0.256 |

0.970 |

| SY–BPA (pH = 2) |

23.01 |

22.11 |

3.715 |

0.893 |

22.61 |

0.305 |

0.978 |

| BPA (pH = 4) |

24.12 |

23.49 |

4.012 |

0.982 |

24.77 |

0.269 |

0.977 |

| EY–BPA (pH = 4) |

27.23 |

26.27 |

1.606 |

0.961 |

28.40 |

0.086 |

0.991 |

| BPA (pH = 7) |

24.95 |

24.27 |

4.852 |

0.980 |

25.47 |

0.331 |

0.996 |

| CR–BPA (pH = 7) |

19.94 |

19.81 |

1.177 |

0.999 |

21.84 |

0.072 |

0.984 |

3.4. Thermodynamic analysis

The adsorption capacities of PDA/PEI-TPU NFMs in both monomeric and binary wastewater systems are shown in

Figure 6. In this figure, the

X coordinate represents the initial concentration (

C0) of another influencing pollutant in the binary system, the

Y coordinate is the equilibrium concentration (

Ce) of the target pollutant, and the

Z coordinate is the adsorption capacity.

The quantity

Rq,i defined in equation (5) is a measure of the interaction between pollutants. From the literature, when

Rq,i > 1, other pollutants promote the adsorption of pollutant

i; when

Rq,i = 1, other pollutants have no effect on the adsorption capacity of pollutant

i; and when

Rq,i < 1, the presence of other pollutants inhibits the adsorption of pollutant

i [

2,

24]. We used this parameter to investigate and characterize the performance of PDA/PEI-TPU NFMs for the removal of dyes and BPA under binary conditions, as shown in

Figure 7.

The BPA and dyes in binary wastewater systems affect each other’s adsorption; moreover, the interactions between the three binary wastewater systems, CR–BPA, SY–BPA, and EY–BPA, were distinct. In the CR–BPA binary system, when the concentration of CR was low (<100 mg/L), the increase in BPA had a negligible impact on the adsorption of CR (see

Figure 6(d)). The isothermal adsorption experiments with CR in a monomeric system revealed that the maximum adsorption capacity (

Qmax)of the PDA/PEI-TPU NFMs for CR was as high as 208.3 mg/g. Therefore, although BPA competes with CR for the adsorption sites on the membrane, the membrane did not reach saturation capacity for this adsorbent, leaving behind an excess of CR adsorption sites on the membrane. The antagonistic effect between BPA and CR gradually appears as the concentration of CR is increased, and they compete with each other for adsorption sites. As the concentration of BPA was increased, the CR adsorption capacity decreased sharply, indicating that the adsorption of CR was inhibited by high concentrations of BPA. Similarly, CR directly inhibited the adsorption of BPA in the binary wastewater system, and the higher the concentration, the more obvious the antagonistic effect. Due to the fact that the affinity of the adsorbent for BPA is slightly weaker than it is for CR [

25], the

Qmax for BPA decreased from 26.7 to 22.8 mg/g. Therefore, as long as CR partially occupies the BPA adsorption sites, the adsorption of BPA will be affected, which is similar to the result obtained in previous study [

26].

However, in the EY–BPA binary system, the interaction exhibited a synergistic effect. The maximum adsorption capacities for EY and BPA were 60.0 mg/g and 35.6 mg/g, respectively, in the monomeric system, and 71.9 mg/g and 43.2 mg/g in the binary system. That is, the adsorption capacities in the binary system were higher than those in the monomeric system. In the EY–BPA binary system, the values of Rq,i for both EY and BPA were greater than 1, indicating that the coexistence of BPA and EY in the solution remarkably promoted the adsorption of both.

The SY–BPA binary system was slightly different from the first two systems. The SY and the BPA behaved independently of each other, and the adsorption process for one compound was less influenced by the other. The value of

Rq,i for this binary system was also approximately 1. This is similar to previous results wherein BPA was mixed with MO and MB, for which the kinetic adsorption capacities and adsorption curves were not remarkably different from those of the monomeric system [

27].

In conclusion the synergistic or antagonistic adsorption of BPA and various dyes was related both to the concentration of BPA and dyes, and the amount of adsorption was different for different dyes. These experiments are thus important for understanding the interaction between BPA and various dyes and for the application of PDA/PEI-TPU NFMs in the field of multi-dye wastewater treatment.

3.5. Mechanistic analysis

The characteristic absorption bands of TPU NFMs at 3355, 1727, and 1061 cm

−1 can be assigned to the N–H, C=O, and C–O–C stretching vibrations, respectively [

28]. After being coated with PDA/PEI, the intensity of a broad absorption band at 3100–3650 cm

−1 increased compared to its intensity in the TPU NFMs. This can be attributed to stretching vibrations of the O–H group in PDA and the N–H group in PEI. In the PDA/PEI-TPU NFMs, a new absorption band was observed at 1659 cm

−1, which can be attributed to stretching vibrations of the C=N bonds formed between PEI and PDA [

29]. The formation of these C=N bonds indicates the occurrence of Schiff-base reactions and Michael additions.

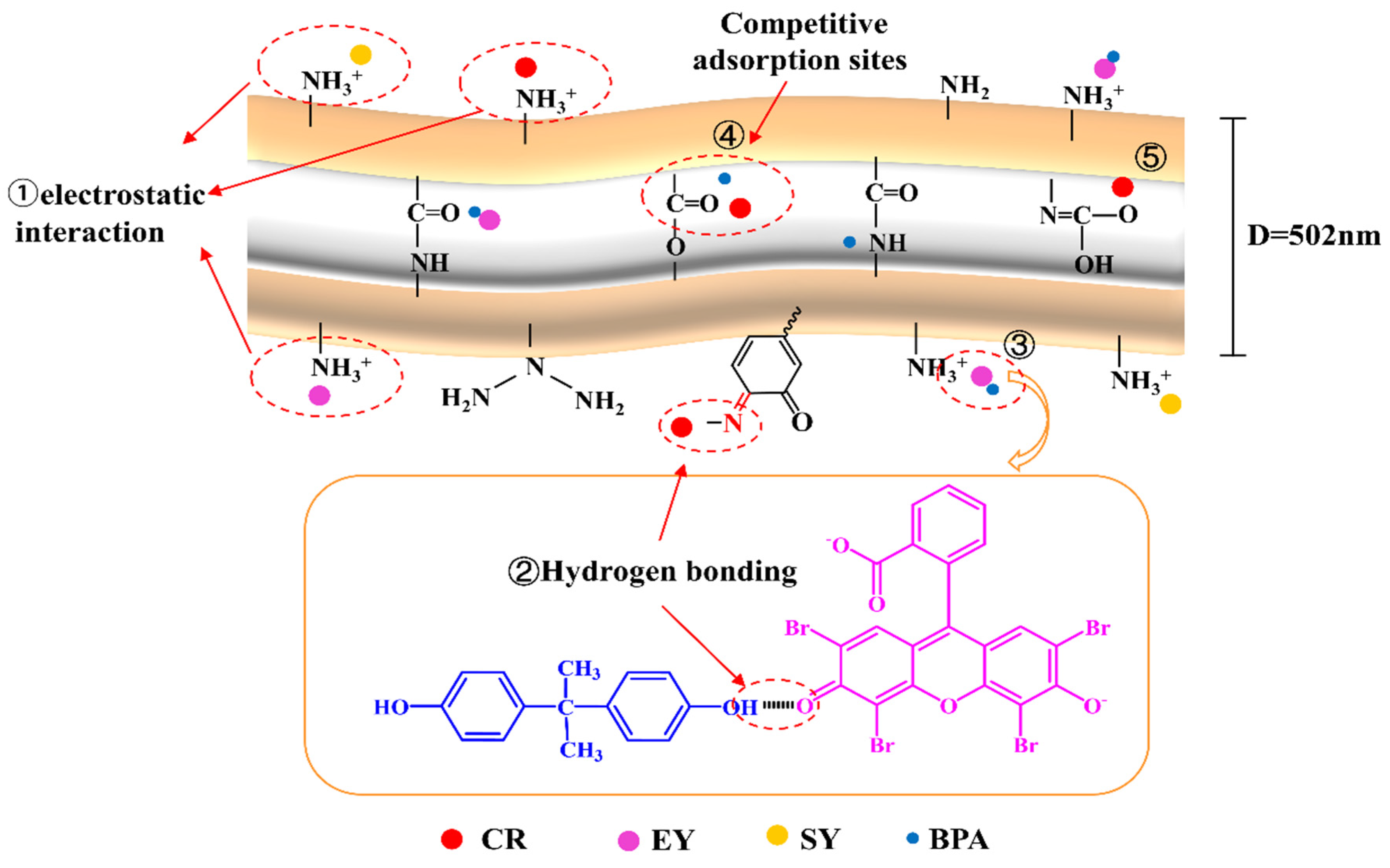

Due to the covalent cross-linking of DA in a tri-HCl buffer solution with PEI via Michael additions and Schiff-base reactions, the deposited layer of PDA/PEI was successfully grafted onto the membrane surface [

30,

31]. The surface layer therefore has many protonated amino adsorption sites, as well as the quinone hydroxyl groups in polydopamine, active C=N bonds, etc. [

32,

33]. The sulfonic acid groups in CR, SY, and EY ionize under acidic conditions to form –SO

3−, which is adsorbed by electrostatic interactions with the positively charged protonated amino groups (as shown in

Figure 8-①). In addition, CR can be adsorbed by hydrogen bonding with the C=N bond in PDA and with the functional groups within the PDA/PEI-TPU NFMs (as shown in

Figure 8-② and 8-⑤). Many studies of the BPA adsorption mechanism have been performed; they have shown that hydrophobic interactions and hydrogen bonding are the two main groups of adsorption mechanisms [

23,

34]. Similarly, the adsorption of BPA onto PDA/PEI-TPU NFMs is predominantly driven by hydrogen bonding and hydrophobic interactions. Hydrogen bonding occurs primarily between the H atoms in BPA and the O atoms in the amine ester groups, ethers, esters, and urea groups within the PDA/PEI-TPU NFMs. In contrast, for TPU NFMs, the hydrophobic interactions of BPA occur mainly between alkyl groups.

In the CR–BPA binary system, as shown in

Figure 8-④, –NH in the CR molecular structure and –OH and –COO– in the BPA molecular structure adsorb the contaminant to the material via hydrogen bonding. Because BPA and CR share the same adsorption sites, they compete with each other. As shown in

Figure 8-③, EY is adsorbed onto the surface of the membrane by electrostatic interactions. The adsorption of BPA continues due to interactions between the –OH group and EY, such as hydrogen bonding or π–π interactions between the BPA and the benzene ring, thus enabling the two to synergistically promote each other's adsorption. In contrast, SY and BPA do not interfere with each other, and the adsorption sites exist independently.

4. Conclusions

By optimizing the synthesis conditions of PDA/PEI-TPU NFMs, we obtained the optimal monomer ratio DA:PEI = 2:2 and the optimal deposition time of 48 h. Adsorption experiments with three different dyes revealed that the dye–BPA binary systems followed three distinct laws. In a CR–BPA binary wastewater system, the adsorption capacity for BPA and CR decreased, compared with that of the respective monomeric systems, because CR and BPA possessed the same adsorption sites and competed with each other. Hydrogen bonding between the O atoms in EY and the H atoms in BPA, along with π–π interactions involving the benzene rings, enabled the bridging of EY and BPA, thus promoting the adsorption of both pollutants. In the SY–BPA binary wastewater system, the two pollutants were adsorbed independently of each other. This study demonstrated the potential of PDA/PEI-TPU NFMs in removing dye–BPA composite pollutants. Furthermore, it revealed that binary systems of BPA with different dyes exhibit different adsorption effects.

Author Contributions

Writing—original draft and reviewing, visualization, Y.Q.; conceptualization, methodology, J.S.; investigation, data curation, visualization, Y.Z.; supervision, J.F.; investigation, methodology, Y.H. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by Science and Technology Research Project of Chongqing Municipal Education Commission (Project No. KJQN202200704), National Engineering Research Center for Inland Waterway Regulation (Project No. SLK2021B08) and Natural Science Foundation of Chongqing, China (Project No. cstc2020jcyj-msxm X0928).

Data Availability Statement

Data sharing not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

References

- Wang, D.; Wang, J. Electrospinning Polyvinyl alcohol/silica-based nanofiber as highly efficient adsorbent for simultaneous and sequential removal of Bisphenol A and Cu(II) from water. Chem. Eng. J. 2017, 314, 714–726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tovar-Gómez, R.; Rivera-Ramírez, D.A.; Hernández-Montoya, V.; Bonilla-Petriciolet, A.; Durán-Valle, C.J.; Montes-Morán, M.A. Synergic adsorption in the simultaneous removal of acid blue 25 and heavy metals from water using a Ca(PO3)2-modified carbon. J. Hazard. Mater. 2012, 199-200, 290–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Fan, Q.; Wu, Y.; Wang, X.; Chen, C.; Tang, Z. Magnetic polydopamine decorated with Mg–Al LDH nanoflakes as a novel bio-based adsorbent for simultaneous removal of potentially toxic metals and anionic dyes. J. Mater. Chem. A. 2016, 4, 1737–1746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, F.; Repo, E.; Yin, D.; Meng, Y.; Jafari, S. EDTA-Cross-Linked β-Cyclodextrin: An environmentally friendly bifunctional adsorbent for simultaneous adsorption of metals and cationic dyes. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2015, 49, 10570–10580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tao, X.; Wu, Y.; Cha, L. Shaddock peels-based activated carbon as cost-saving adsorbents for efficient removal of Cr (VI) and methyl orange. Environ. Sci. Pollut. R. 2019, 26, 19828–19842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qu, J.; Tian, X.; Jiang, Z.; Cao, B.; Akindolie, M.S.; Hu, Q.; Feng, C.; Feng, Y.; Meng, X.; Zhang, Y. Multi-component adsorption of Pb(II), Cd(II) and Ni(II) onto microwave-functionalized cellulose: Kinetics, isotherms, thermodynamics, mechanisms and application for electroplating wastewater purification. J. Hazard. Mater. 2020, 387, 121718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xue, J.; Liu, W.; Kannan, K. Bisphenols, Benzophenones, and bisphenol A diglycidyl ethers in textiles and infant clothing. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2017, 51, 5279–5286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y.; Hu, Y.; Huang, W.; Cheng, G.; Cui, C.; Lu, J. A novel amphoteric β-cyclodextrin-based adsorbent for simultaneous removal of cationic/anionic dyes and bisphenol A. Chem. Eng. J. 2018, 341, 47–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chlanda, A.; Kijeńska, E.; Rinoldi, C.; Tarnowski, M.; Wierzchoń, T.; Swieszkowski, W. Structure and physico-mechanical properties of low temperature plasma treated electrospun nanofibrous scaffolds examined with atomic force microscopy. Micron 2018, 107, 79–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geng, J.; Yin, Y.; Liang, Q.; Zhu, Z.; Luo, H. Polyethyleneimine cross-linked graphene oxide for removing hazardous hexavalent chromium: Adsorption performance and mechanism. Chem. Eng. J. 2019, 361, 1497–1510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ayalew, Z.M.; Guo, X.; Zhang, X. Synthesis and application of polyethyleneimine (PEI)-based composite/nanocomposite material for heavy metals removal from wastewater: A critical review. J. Hazard. Mater. A. 2022, 8, 100158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arshad, F.; Selvaraj, M.; Zain, J.; Banat, F.; AbuHaija, M. Polyethylenimine modified graphene oxide hydrogel composite as an efficient adsorbent for heavy metal ions. Sep. Purif. Technol. 2019, 209, 870–880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, B.; Liu, Y.; Li, B.; Wang, H.; Zeng, G. Adsorption mechanism of polyethyleneimine modified magnetic core–shell Fe3O4@SiO2 nanoparticles for anionic dye removal. Rsc. Adv. 2019, 9, 32462–32471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, J.; Du, P.; Bi, W.; Yao, G.; Li, S.; Liu, H. Graphene oxide aerogels co-functionalized with polydopamine and polyethylenimine for the adsorption of anionic dyes and organic solvents. Chem. Eng. Res. Des. 2020, 154, 192–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhatnagar, A.; Anastopoulos, I. Adsorptive removal of bisphenol A (BPA) from aqueous solution: A review. Chemosphere 2017, 168, 885–902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yagub, M.T.; Sen, T.K.; Afroze, S.; Ang, H.M. Dye and its removal from aqueous solution by adsorption: A review. Adv. Colloid. Interfac. 2014, 209, 172–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y.; Sun, J.; Zheng, H.; Fan, J.; Hu, Y. Adsorption behaviors of typical endocrine disrupting chemicals by TPU nanofiber membrane. China. Environ. Sci. 2021, 41, 5680–5687. (in Chinese). [Google Scholar]

- Sun, J.; Zhou, Y.; Jiang, X.; Fan, J. Different adsorption behaviors and mechanisms of anionic azo dyes on polydopamine–polyethyleneimine modified thermoplastic polyurethane nanofiber membranes. Water 2022, 14, 3865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mantripragada, S.; Deng, D.; Zhang, L. Remediation of GenX from water by amidoxime surface-functionalized electrospun polyacrylonitrile nanofibrous adsorbent. Chemosphere 2021, 283, 131235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Zheng, J.; Jin, P.; Xu, D.; Yuan, S.; Zhao, R.; Depuydt, S.; Gao, Y.; Xu, Z.; Bruggen, B.V. A PEI/TMC membrane modified with an ionic liquid with enhanced permeability and antibacterial properties for the removal of heavy metal ions. J. Hazard. Mater. 2022, 435, 129010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.; Zeng, J.; Huang, X.; Yuan, Z.; Liu, G.; Ding, J. Styrene-maleic anhydride/polyethersulfone blending membranes modified by PEI functionalized TiO2 to enhance separation and antifouling properties: Dye purification. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 2021, 9, 106040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kapusuz, Y.D. Exploring the structure of RNA-incorporated PEG/PEI modified silica network. Mater. Chem. Phys. 2022, 279, 125779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, X.; Wei, J.; Liu, K.; Liu, N.; Zhou, B. Adsorption of bisphenol A based on synergy between hydrogen bonding and hydrophobic interaction. Langmuir 2014, 30, 13861–13868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mohan, D.; Chander, S. Single, binary, and multicomponent sorption of iron and manganese on lignite. J. Colloid. Interf. Sci. 2006, 299, 76–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Usman, M.A.; Khan, A.Y. Selective adsorption of anionic dye from wastewater using polyethyleneimine based macroporous sponge: Batch and continuous studies. J. Hazard. Mater. 2022, 428, 128238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gurav, R.; Bhatia, S.K.; Choi, T.R.; Kim, H.J.; Choi, Y.K.; Lee, H.J.; Ham, S.; Cho, J.Y.; Kim, S.H.; Lee, S.H.; et al. Adsorptive removal of synthetic plastic components bisphenol-A and solvent black-3 dye from single and binary solutions using pristine pinecone biochar. Chemosphere 2022, 296, 134034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, J.P.; Luo, J.J.; Zhang, X.H.; Zhen, B.; Dong, C.Y.; Li, Y.C.; Shen, J.; Cheng, Y.T.; Chen, H.P. A novel electrospun β-CD/CS/PVA nanofiber membrane for simultaneous and rapid removal of organic micropollutants and heavy metal ions from water. Chem. Eng. J. 2019, 378, 122232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, C.Y.; Kwon, Y.N.; Leckie, J.O. Effect of membrane chemistry and coating layer on physiochemical properties of thin film composite polyamide RO and NF membranes: I. FTIR and XPS characterization of polyamide and coating layer chemistry. Desalination 2009, 242, 149–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, H.C.; Liao, K.J.; Huang, H.; Wu, Q.Y.; Wan, L.Y.; Xu, Z.K. Mussel-inspired modification of a polymer membrane for ultra-high water permeability and oil-in-water emulsion separation. J. Mater. Chem. A 2014, 2, 10225–10230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, J.; Chen, Y.; Fang, C.; Zhu, L. Regenerable adsorptive membranes prepared by mussel-inspired co-deposition for aqueous dye removal. Sep. Purif. Technol. 2022, 281, 119876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almasian, A.; Jalali, M.L.; Fard, G.C.; Maleknia, L. Surfactant grafted PDA-PAN nanofiber: Optimization of synthesis, characterization and oil absorption property. Chem. Eng. J. 2017, 326, 1232–1241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mavukkandy, M.O.; Ibrahim, Y.; Almarzooqi, F.; Naddeo, V.; Karanikolos, G.N.; Alhseinat, E.; Banat, F.; Hasan, S.W. Synthesis of polydopamine coated tungsten oxide@ poly (vinylidene fluoride-co-hexafluoropropylene) electrospun nanofibers as multifunctional membranes for water applications. Chem. Eng. J. 2022, 427, 131021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, H.-C.; Wu, M.-B.; Li, Y.-J.; Chen, Y.-F.; Wan, L.-S.; Xu, Z.-K. Effects of polyethyleneimine molecular weight and proportion on the membrane hydrophilization by codepositing with dopamine. J. Appl. Poly. Sci. 2016, 133, 43792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, Y.; Sun, Z.; Ayoko, G.A.; Frost, R.L. Bisphenol A sorption by organo-montmorillonite: Implications for the removal of organic contaminants from water. Chemosphere 2014, 107, 249–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).