Submitted:

21 June 2023

Posted:

22 June 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

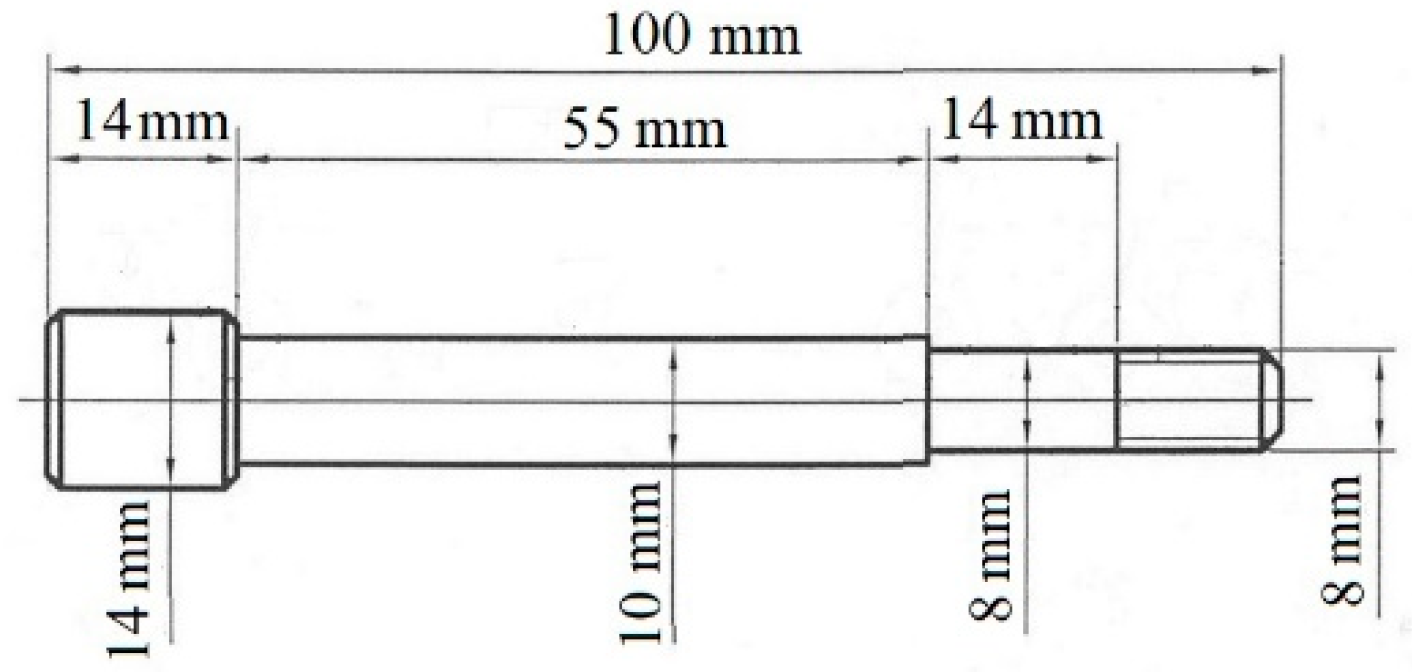

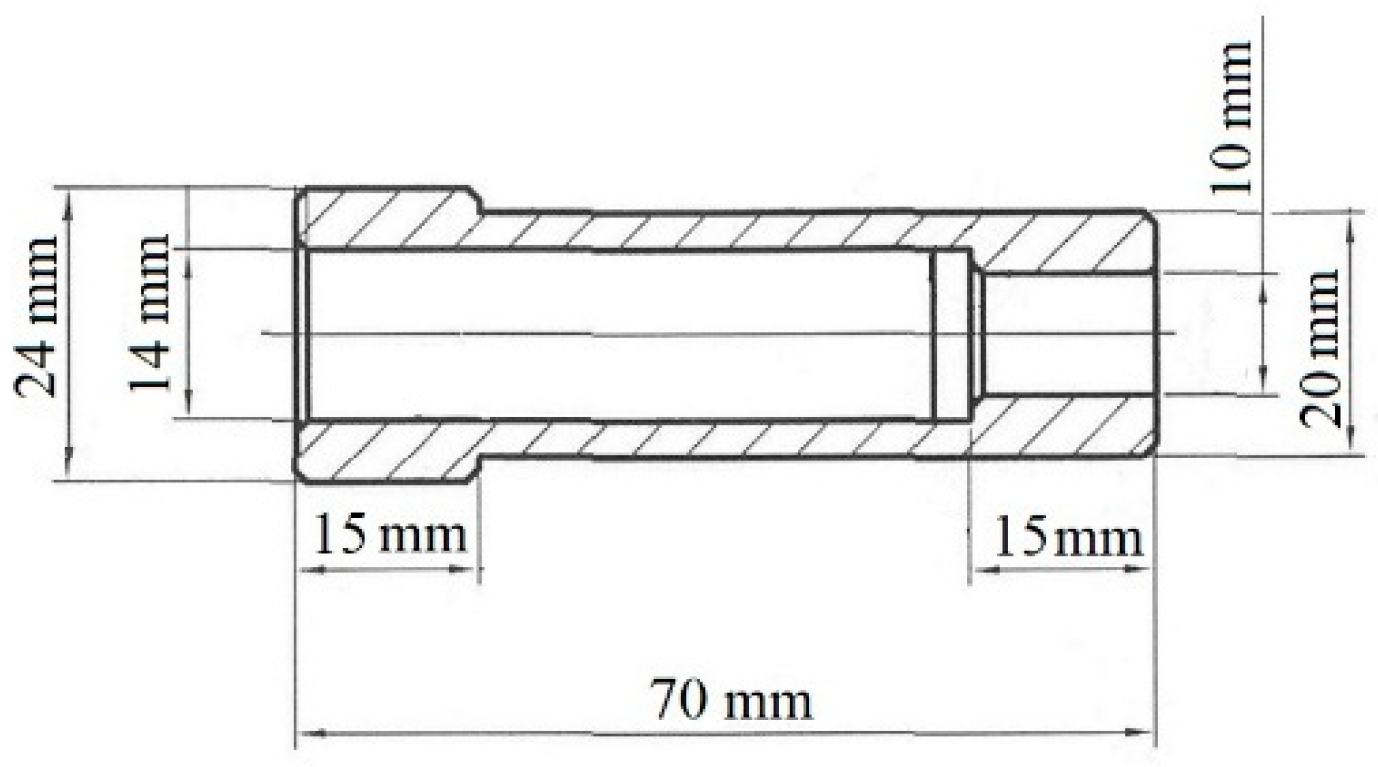

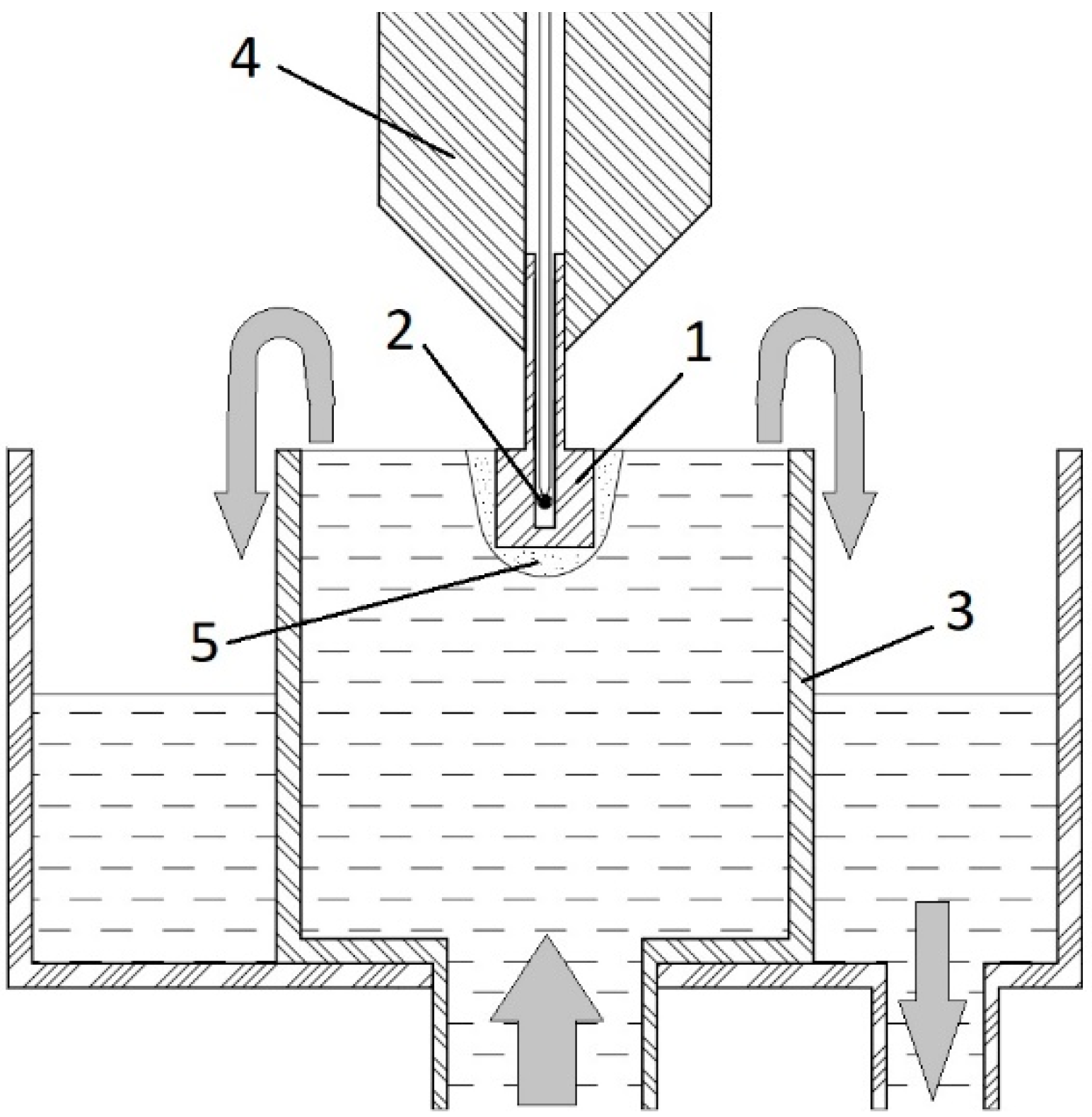

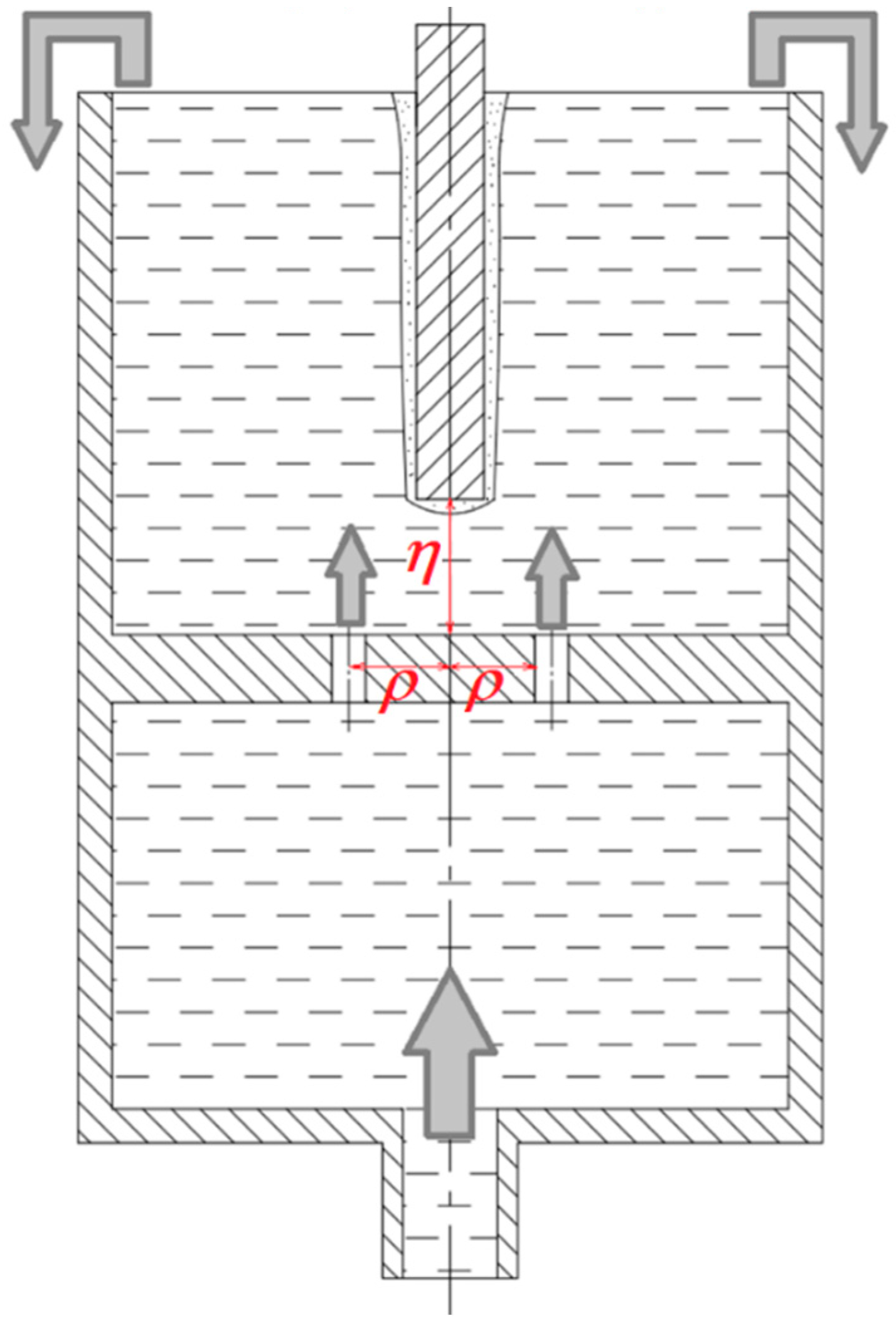

2.1. Samples Processing

2.2. Study of Phase Composition

2.3. The Microhardness Measurement

2.4. Study of the Surface Morphology and Microstructure

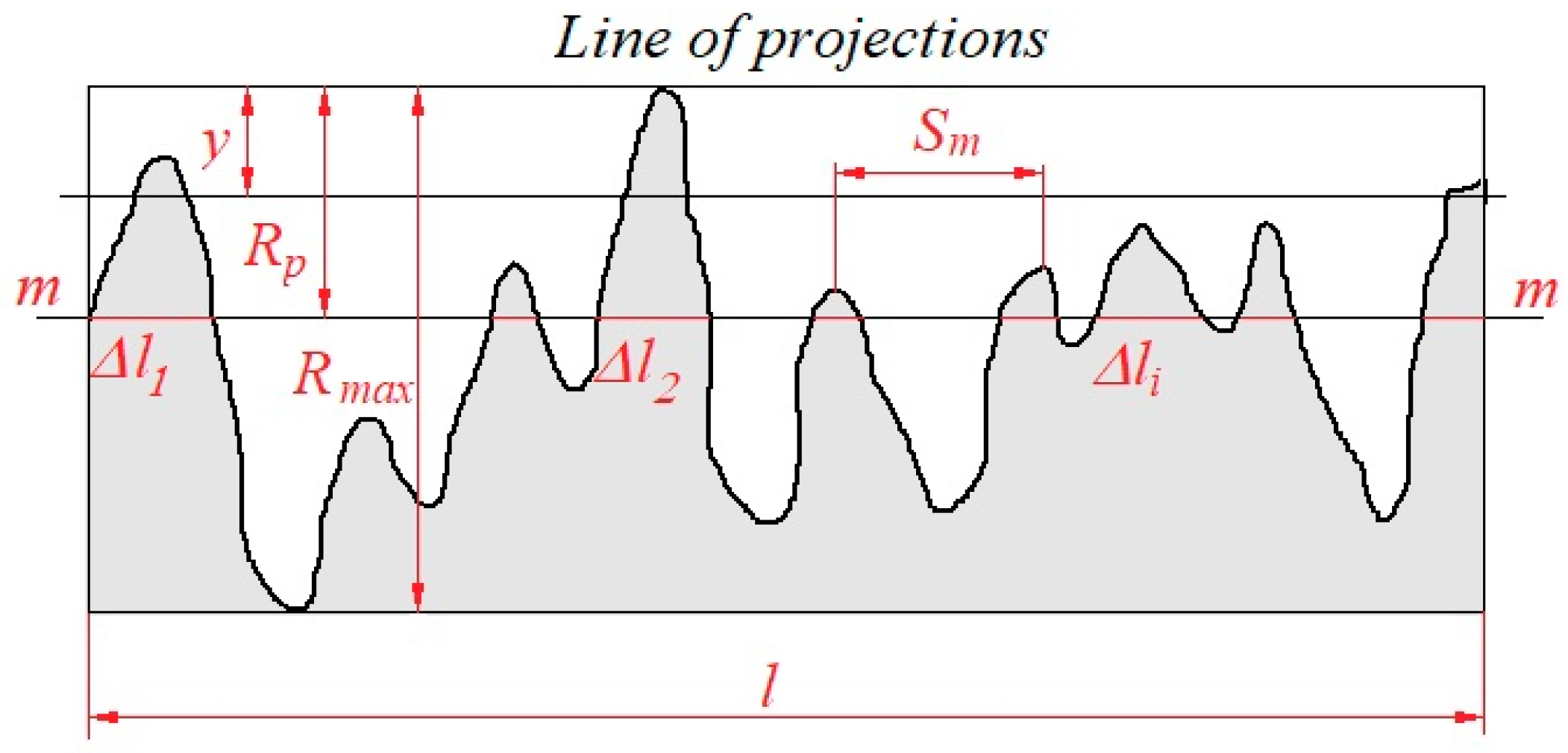

2.5. Surface Roughness and Weight of Samples Measurement

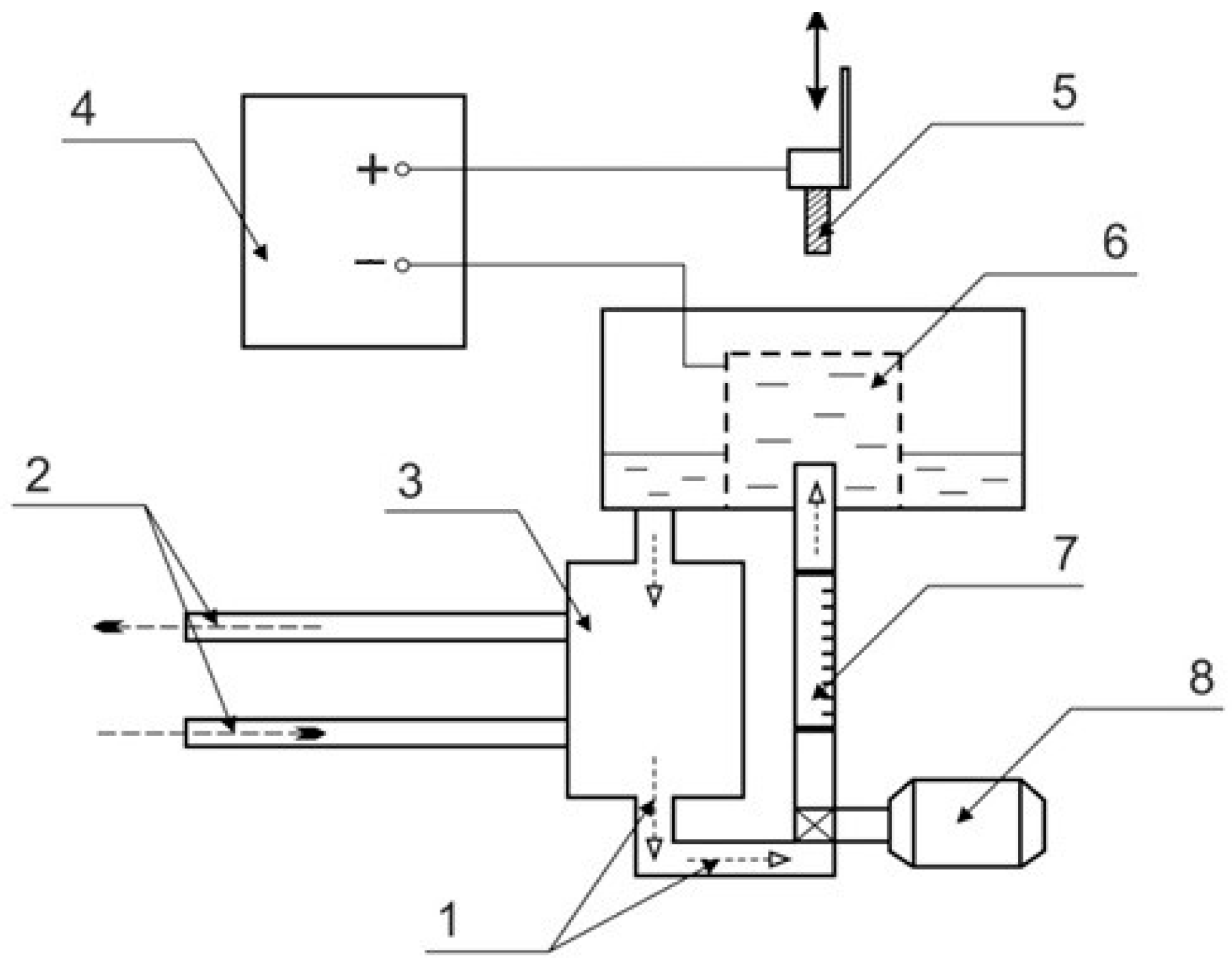

2.6. Study of Tribological Properties

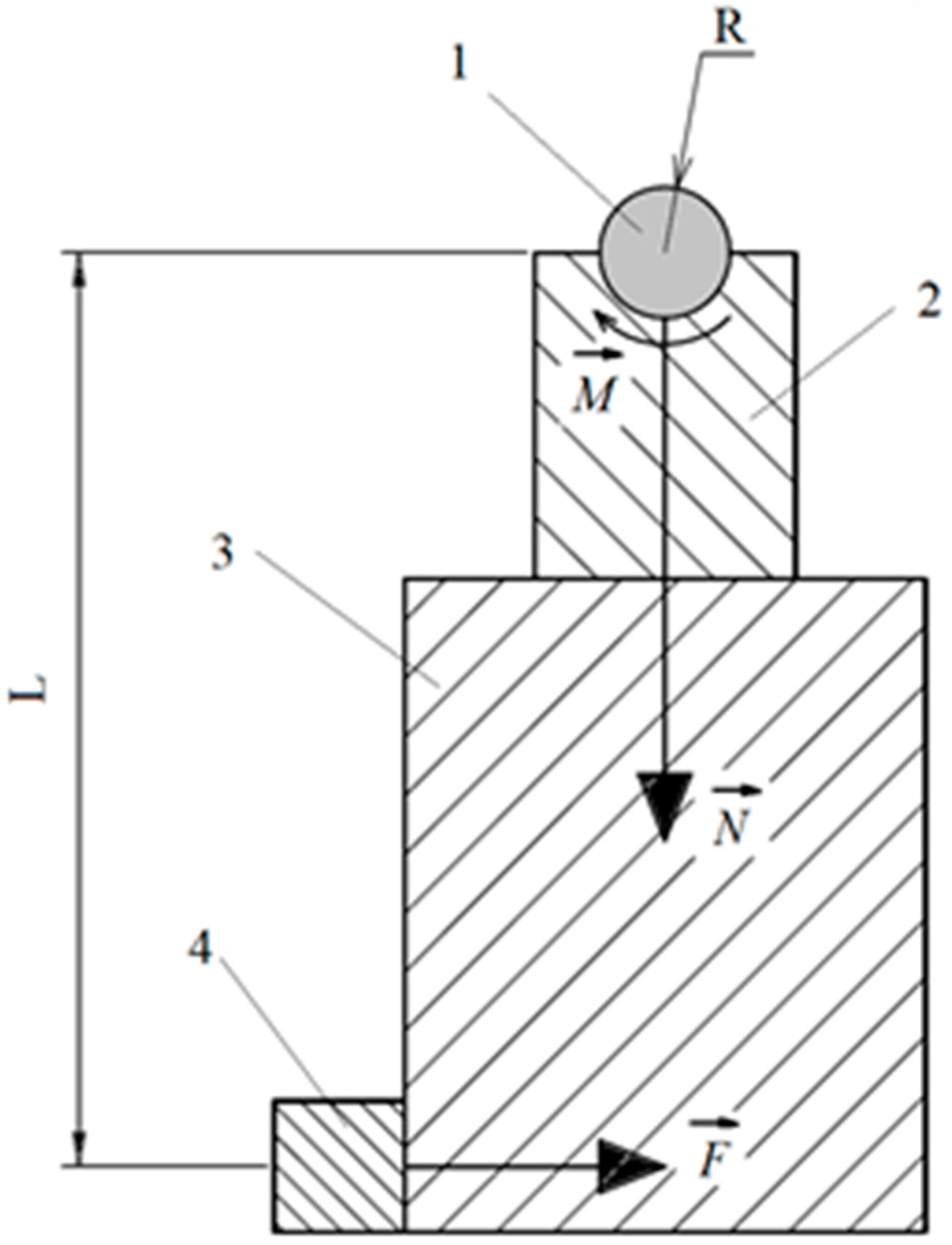

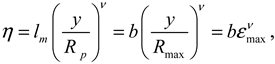

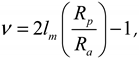

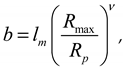

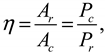

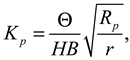

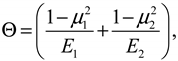

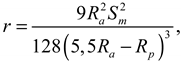

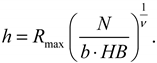

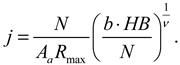

2.7. Contact Stiffness Calculation

| Parameter | Untreated (control) | PENC temperature (°С) | ||||||

| 550 | 600 | 650 | 700 | 750 | 800 | 850 | ||

| r (μm) | 67± 2 |

39± 1 |

43± 1 |

58± 1 |

155± 4 |

153± 4 |

127± 3 |

147± 4 |

| h (μm) | 6.4± 0.2 |

3.6± 0.1 |

3.8± 0.1 |

3.9± 0.1 |

2.5± 0.1 |

2.8± 0.1 |

2.9± 0.1 |

2.6± 0.1 |

| Δ | 0.88± 0.05 |

0.29± 0.02 |

0.28± 0.02 |

0.30± 0.02 |

0.10± 0.01 |

0.11± 0.01 |

0.10± 0.01 |

0.11± 0.01 |

| Kp | 16.8± 5.7 |

5.2± 0.2 |

4.1± 0.2 |

2.8± 0.1 |

1.4± 0.1 |

3.1± 0.1 |

2.1± 0.1 |

1.9± 0.1 |

| j (МPa/ μm) | 0.045± 0.001 |

0.080± 0.002 |

0.076± 0.002 |

0.074± 0.002 |

0.116± 0.003 |

0.103± 0.003 |

0.100± 0.003 |

0.111± 0.003 |

3. Results

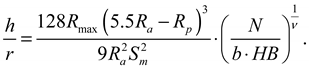

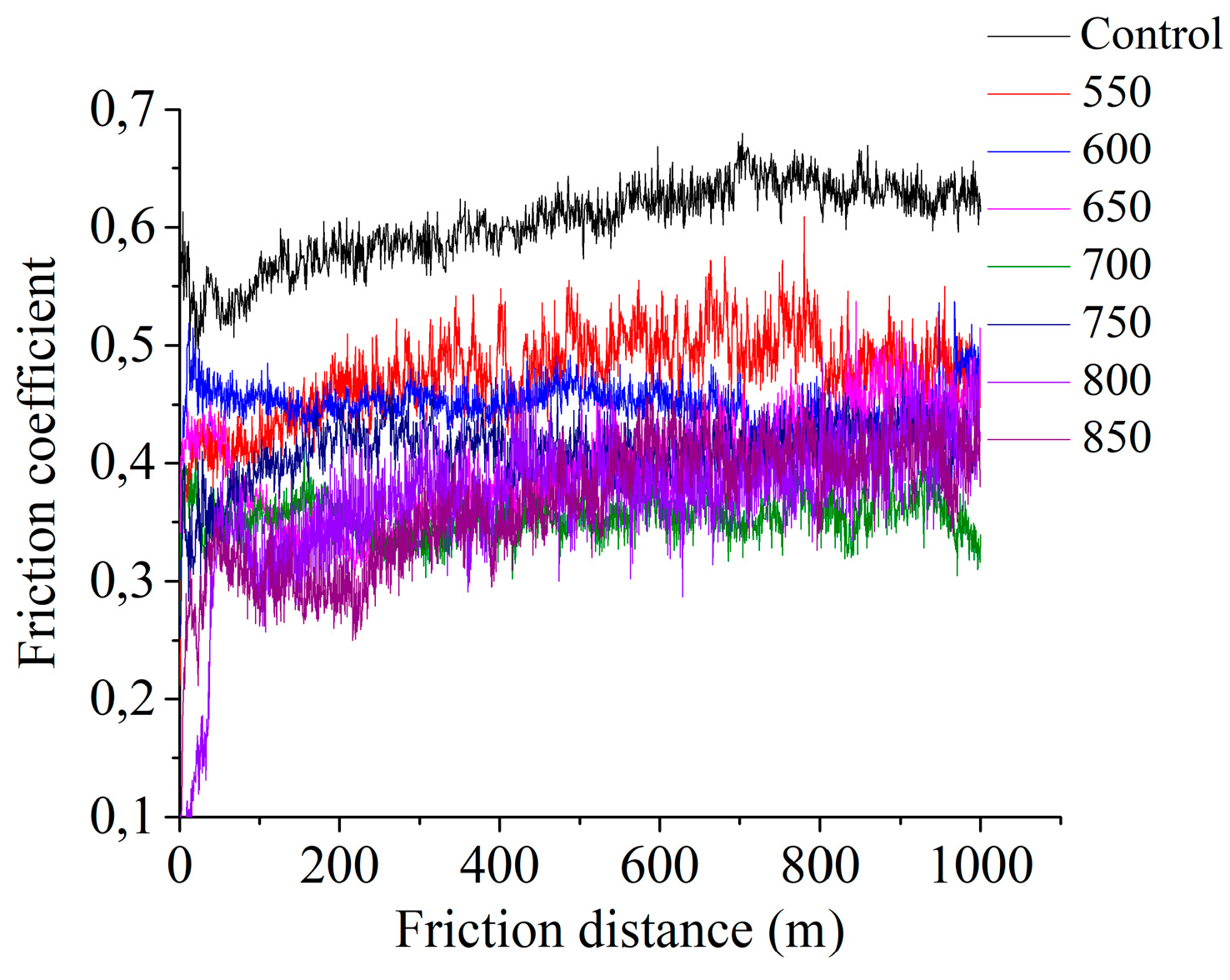

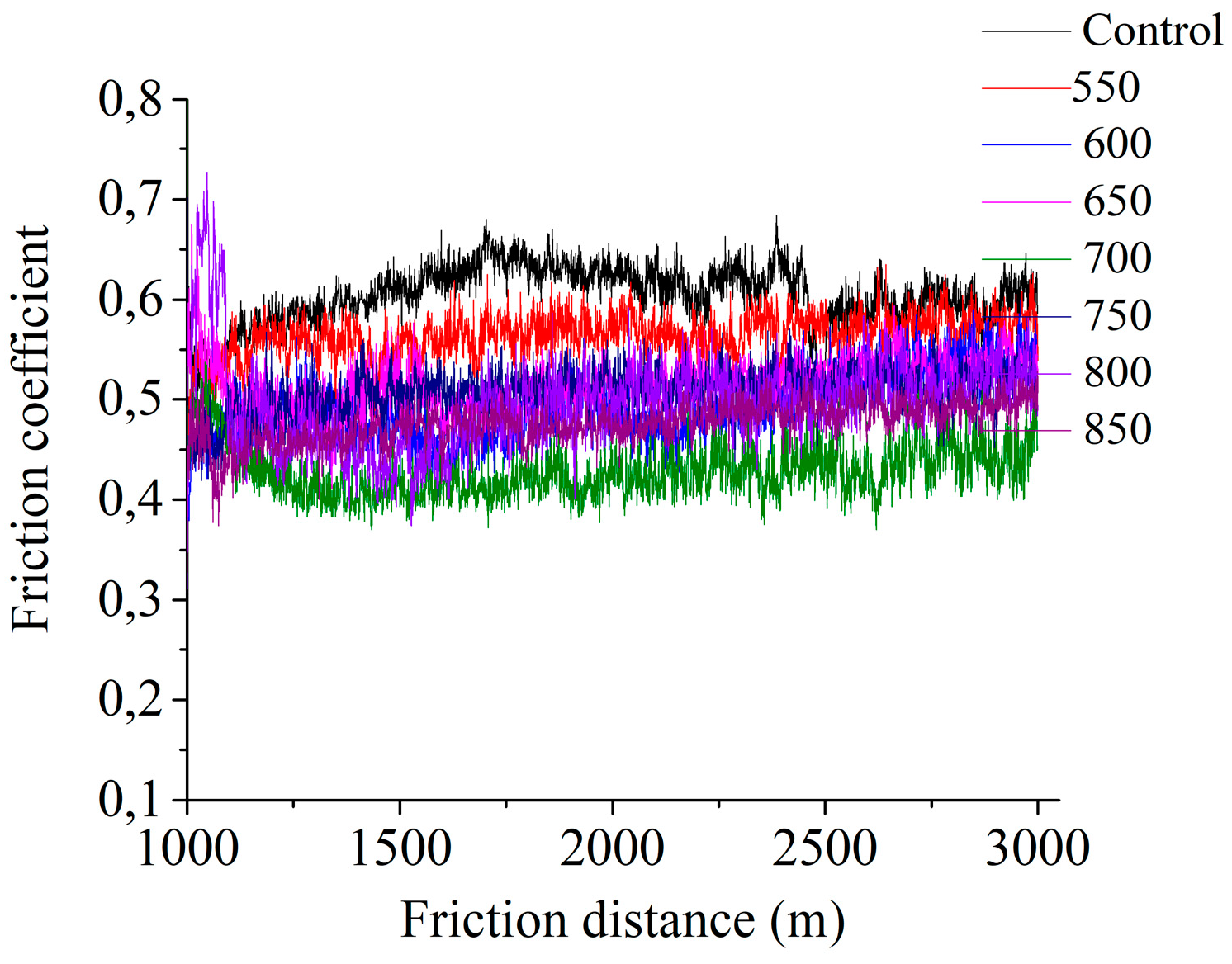

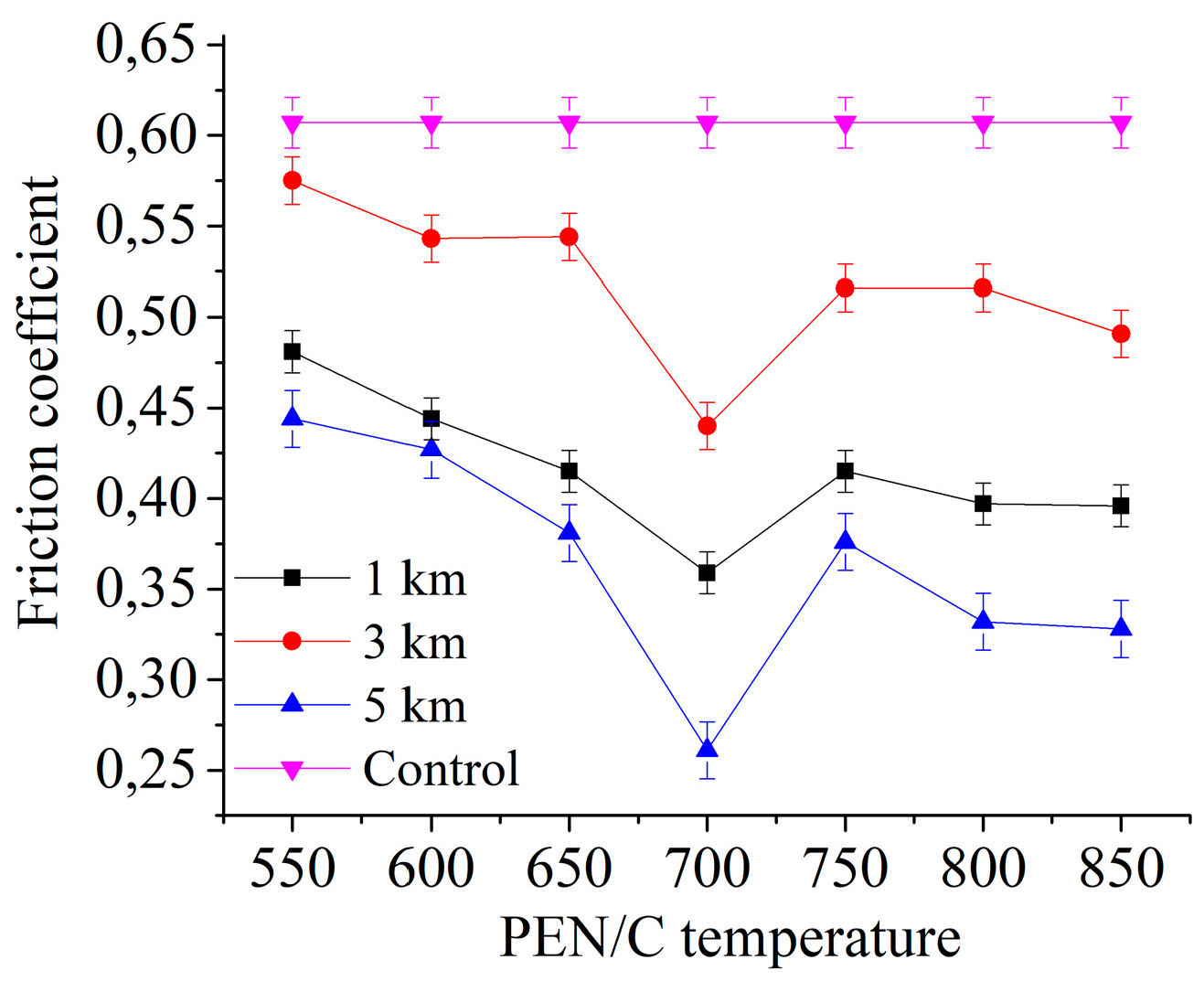

3.1. Friction Coefficient

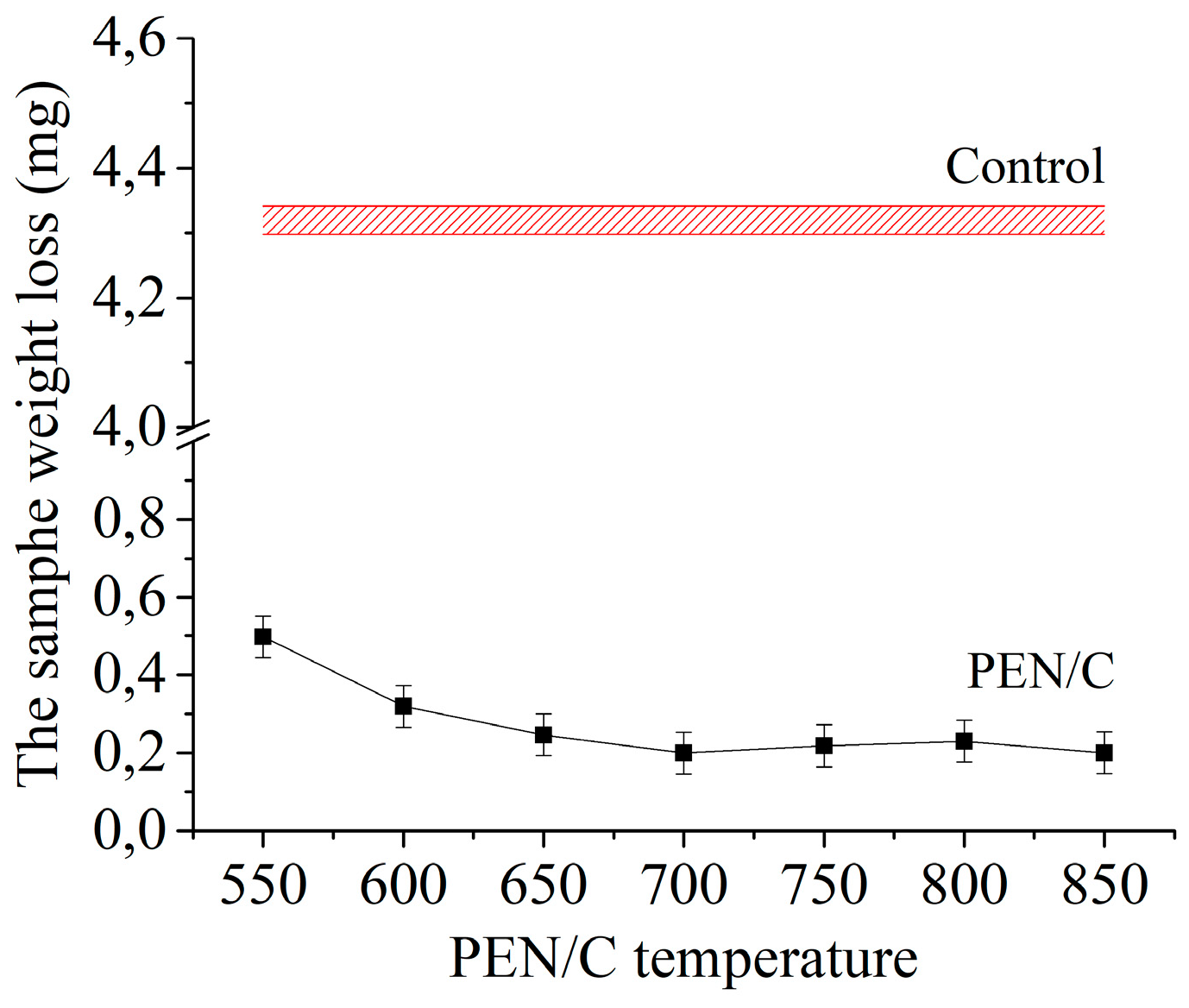

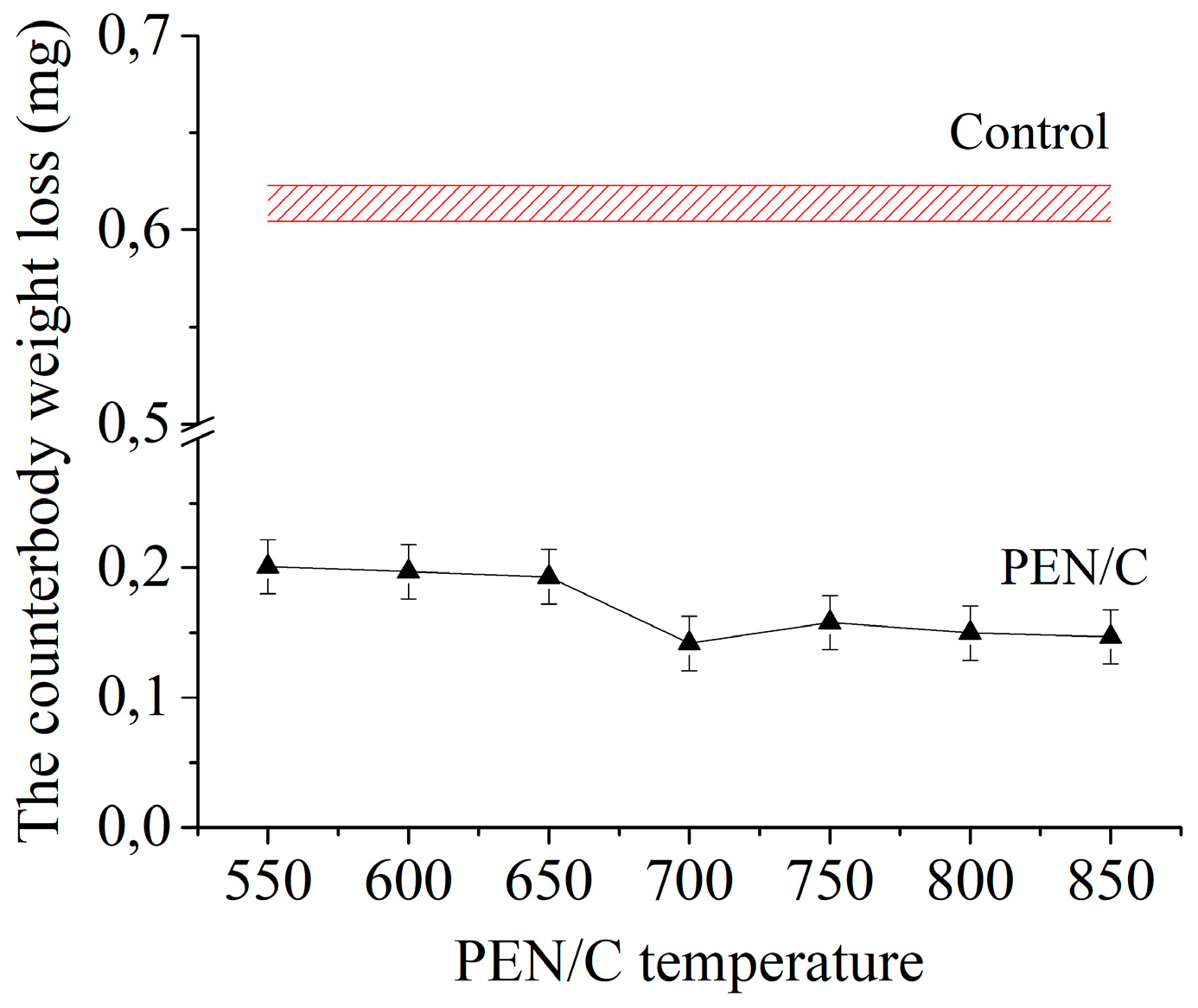

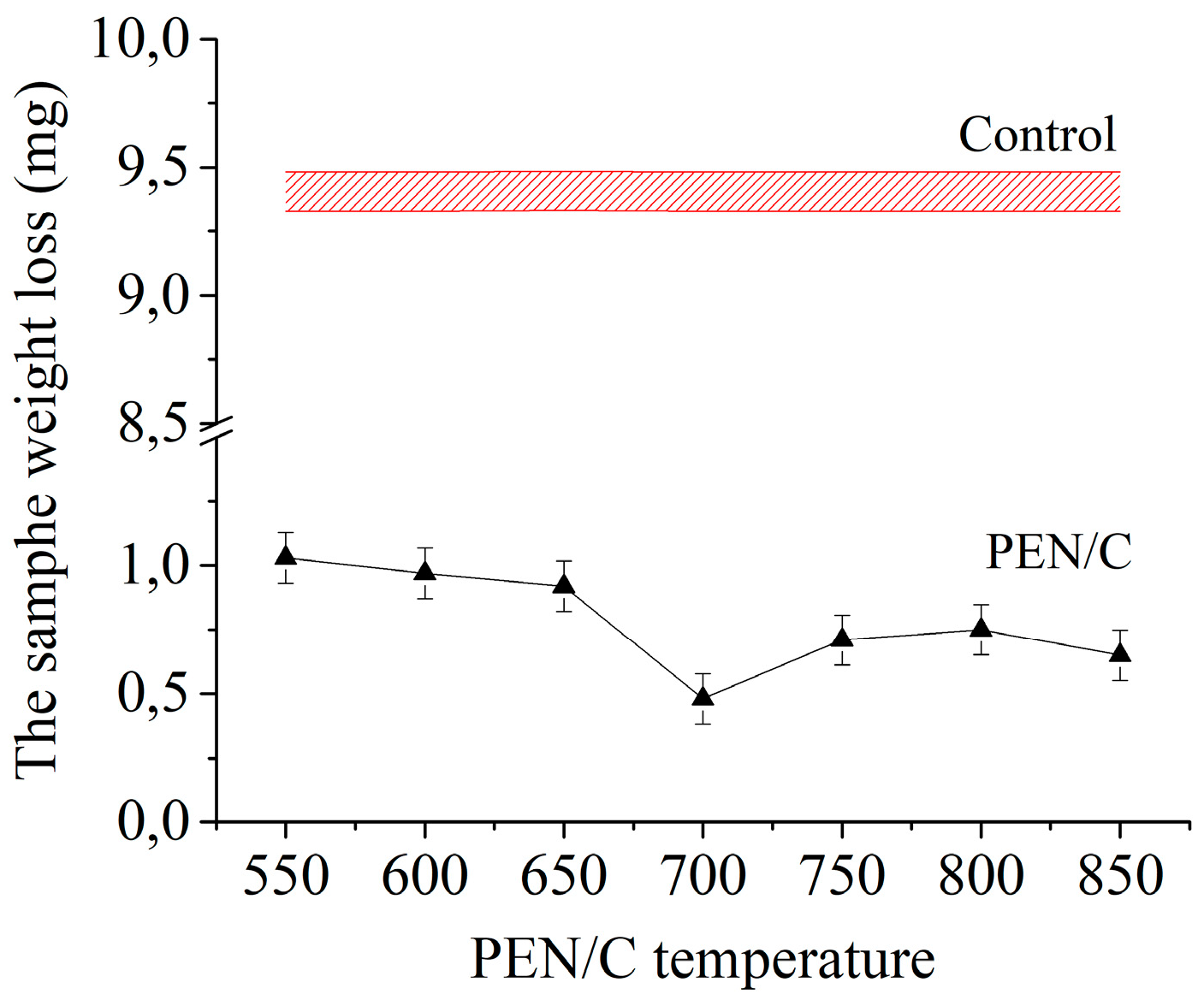

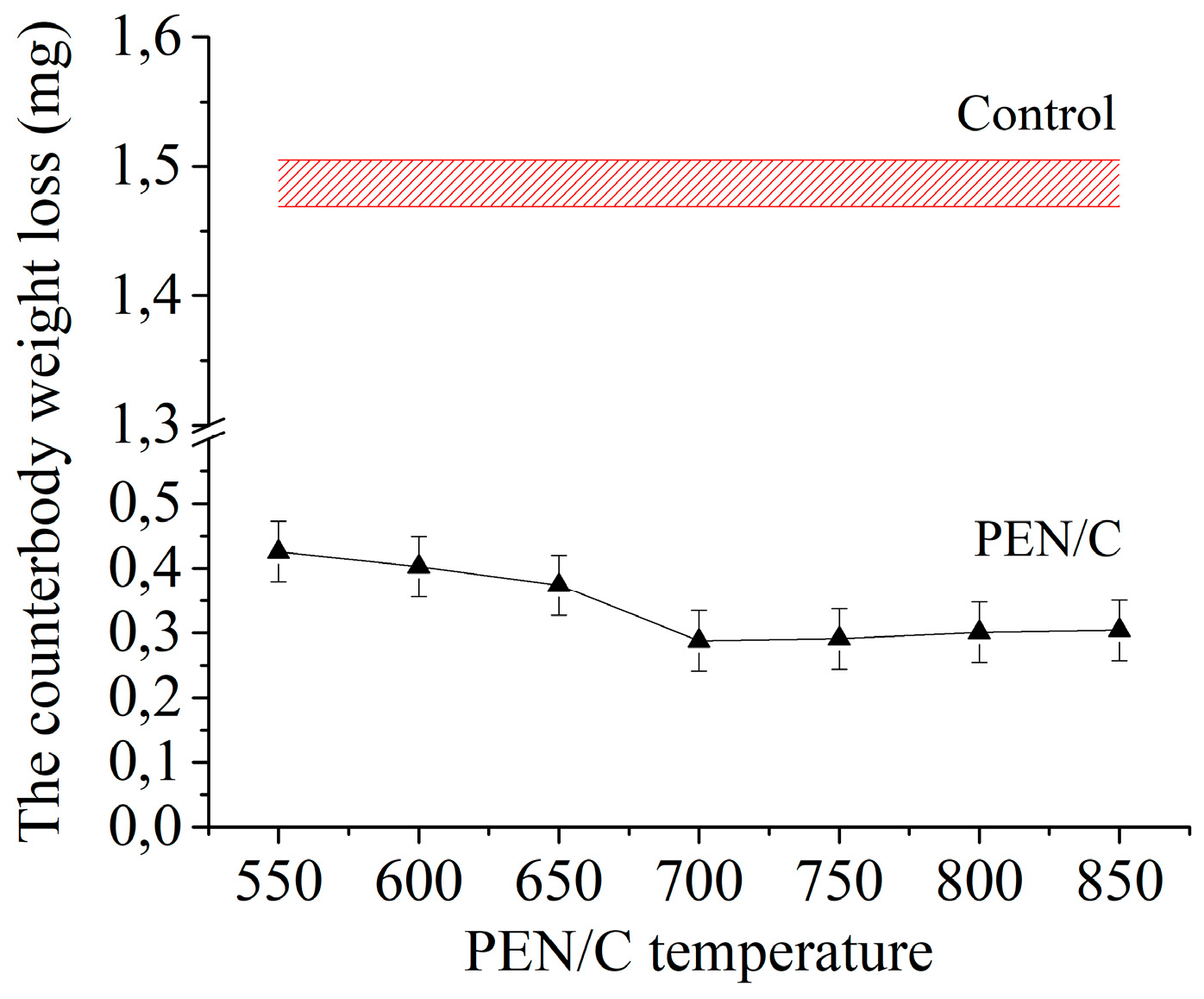

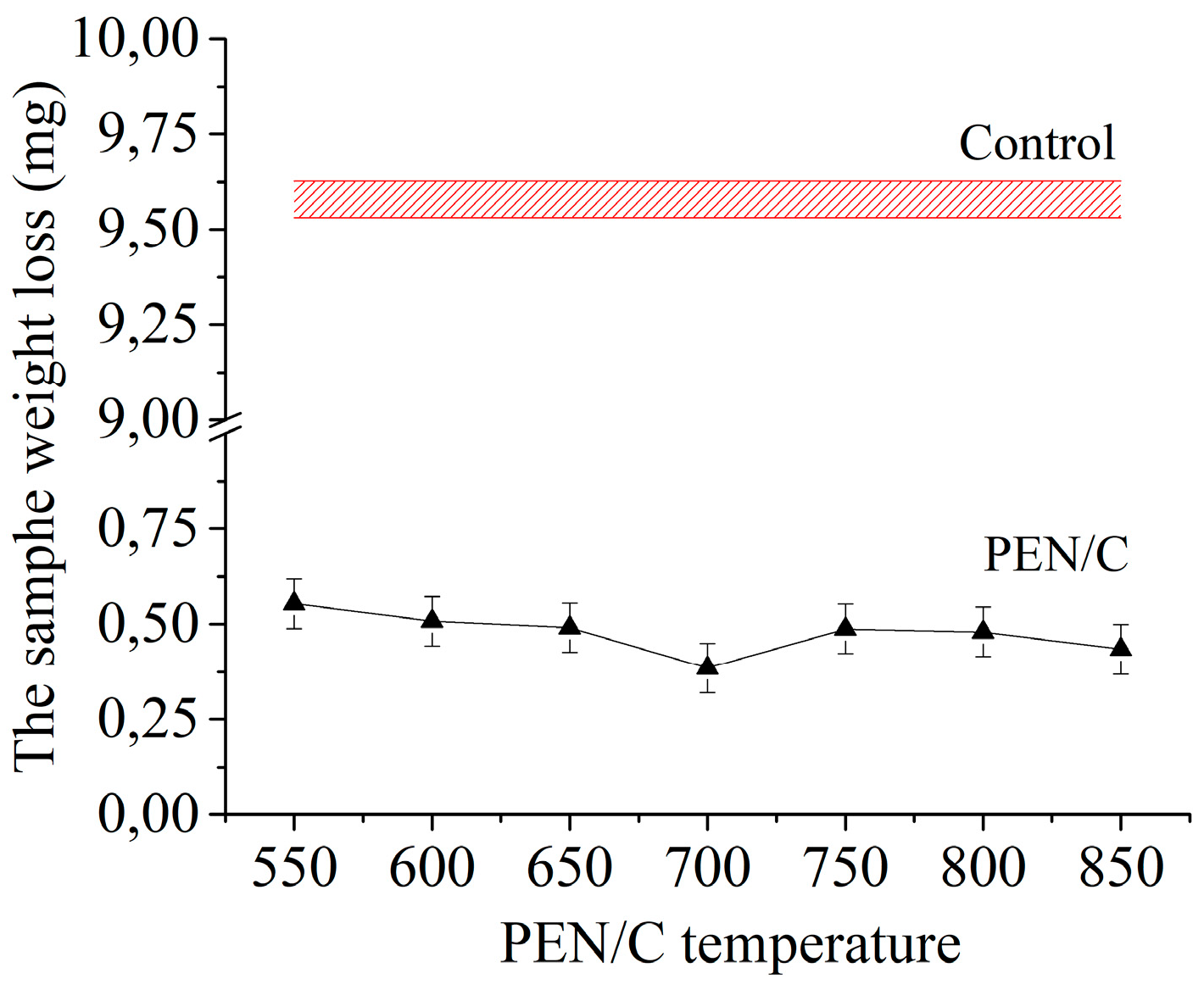

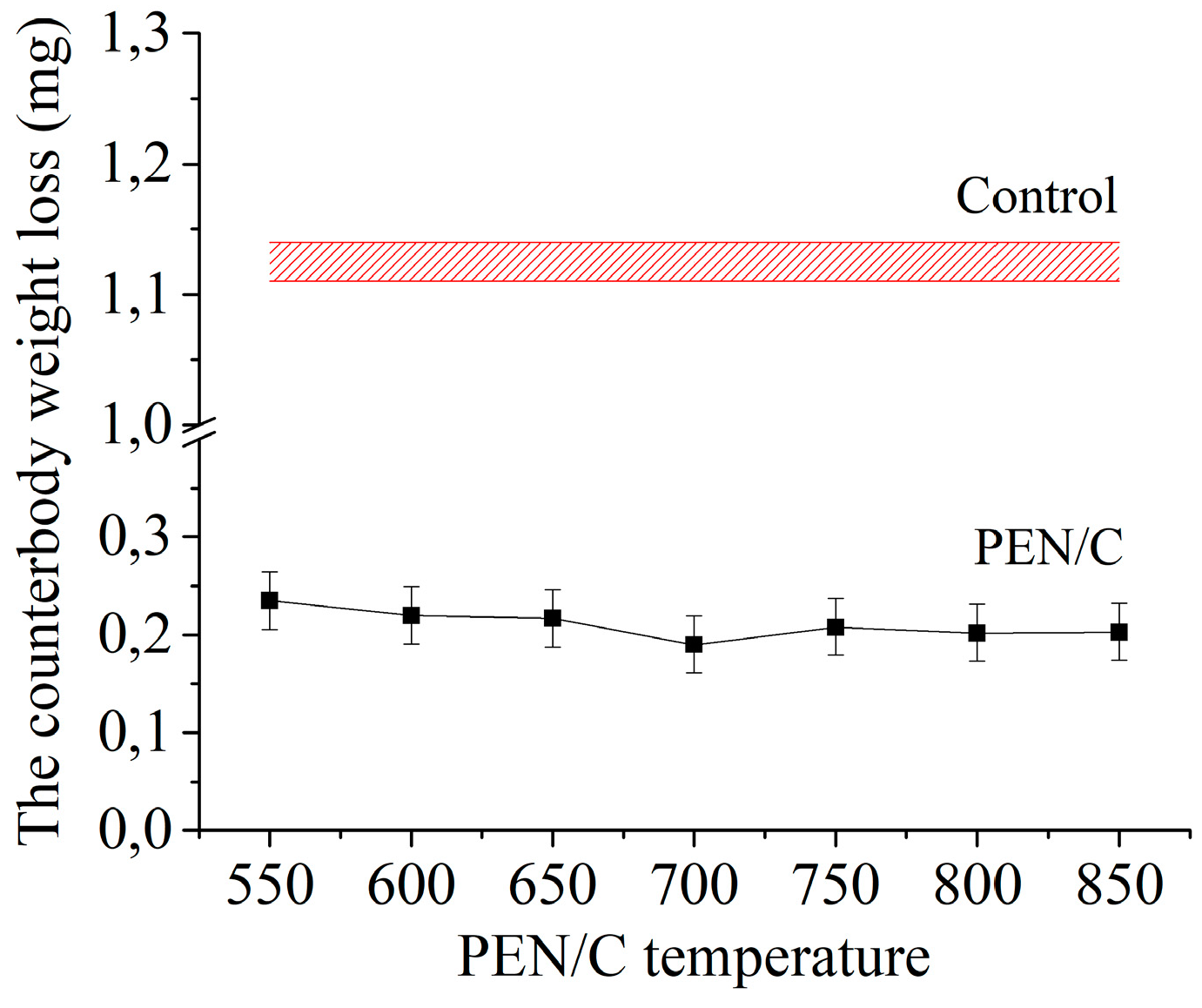

3.2. Wear Resistance

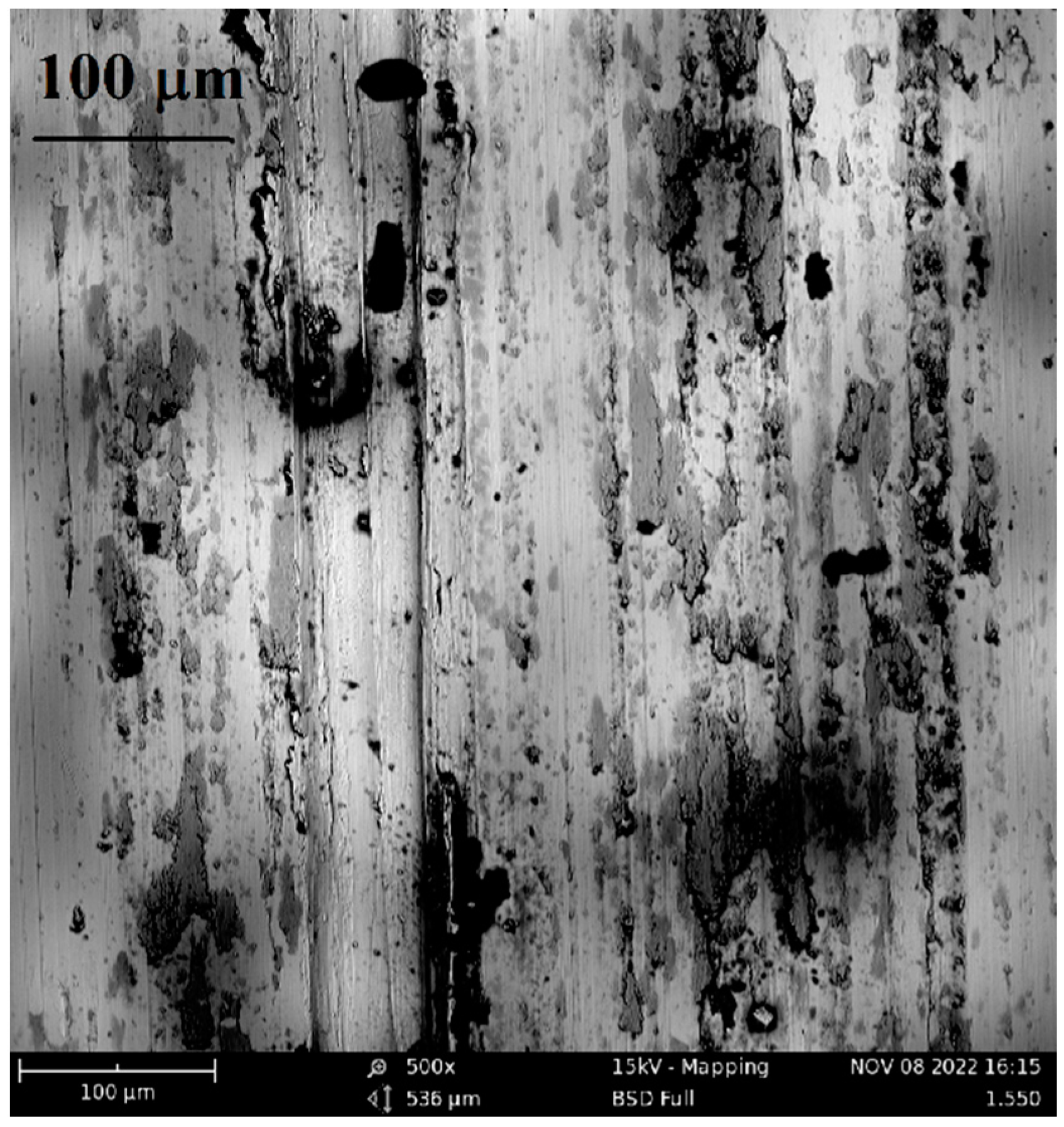

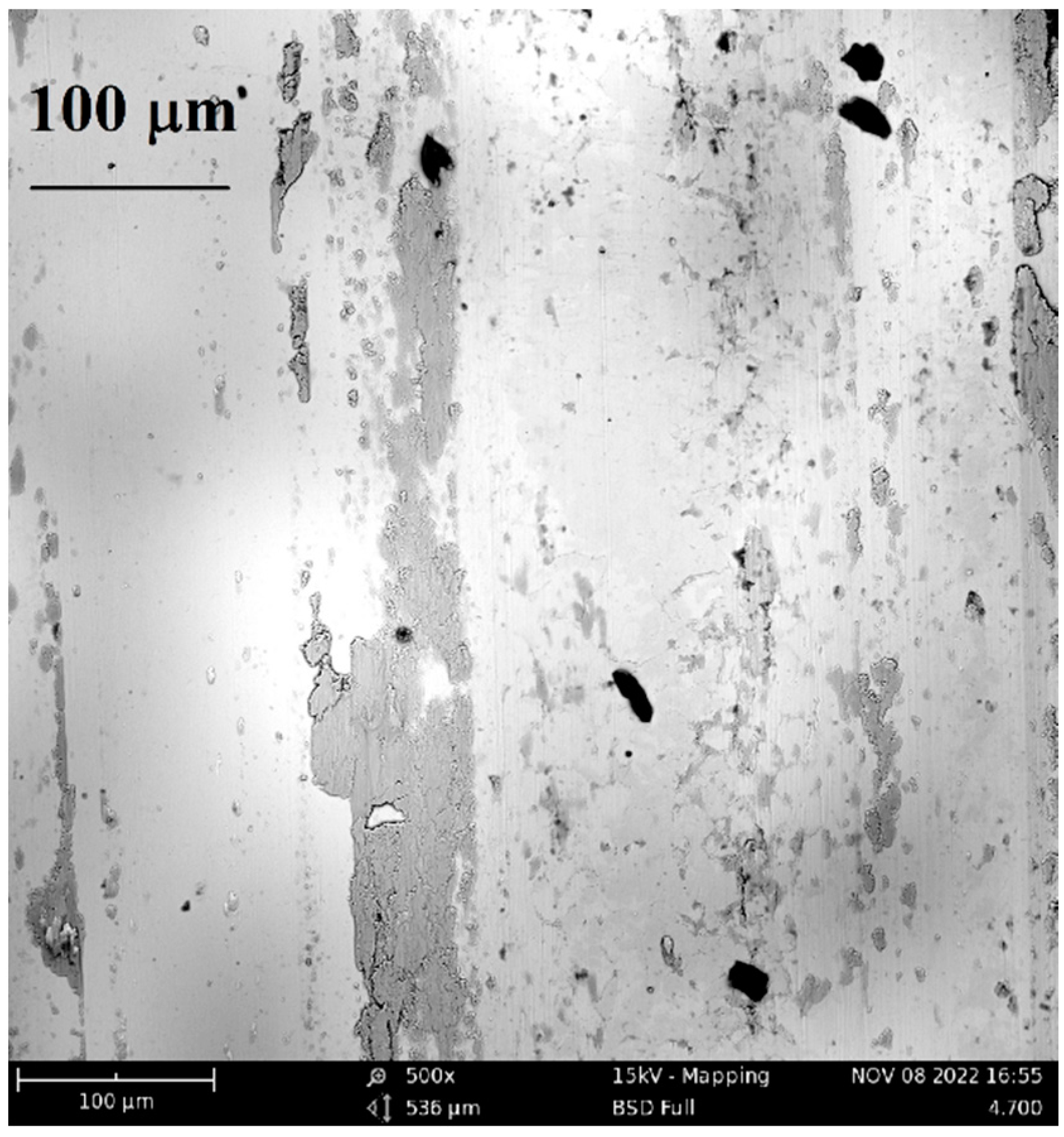

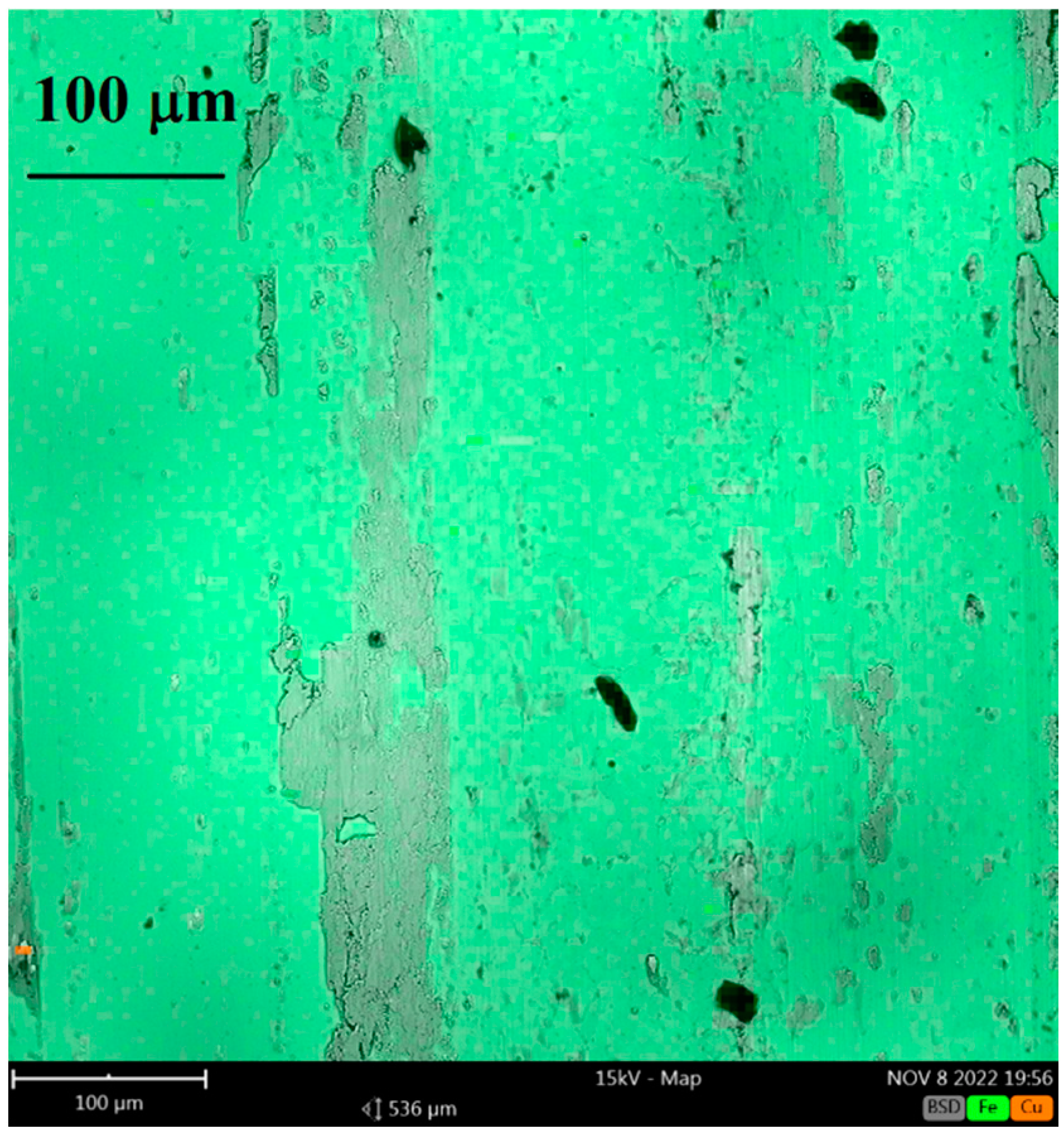

3.3. Friction Track Analysis

3.4. Surface Microgeometry Parameters

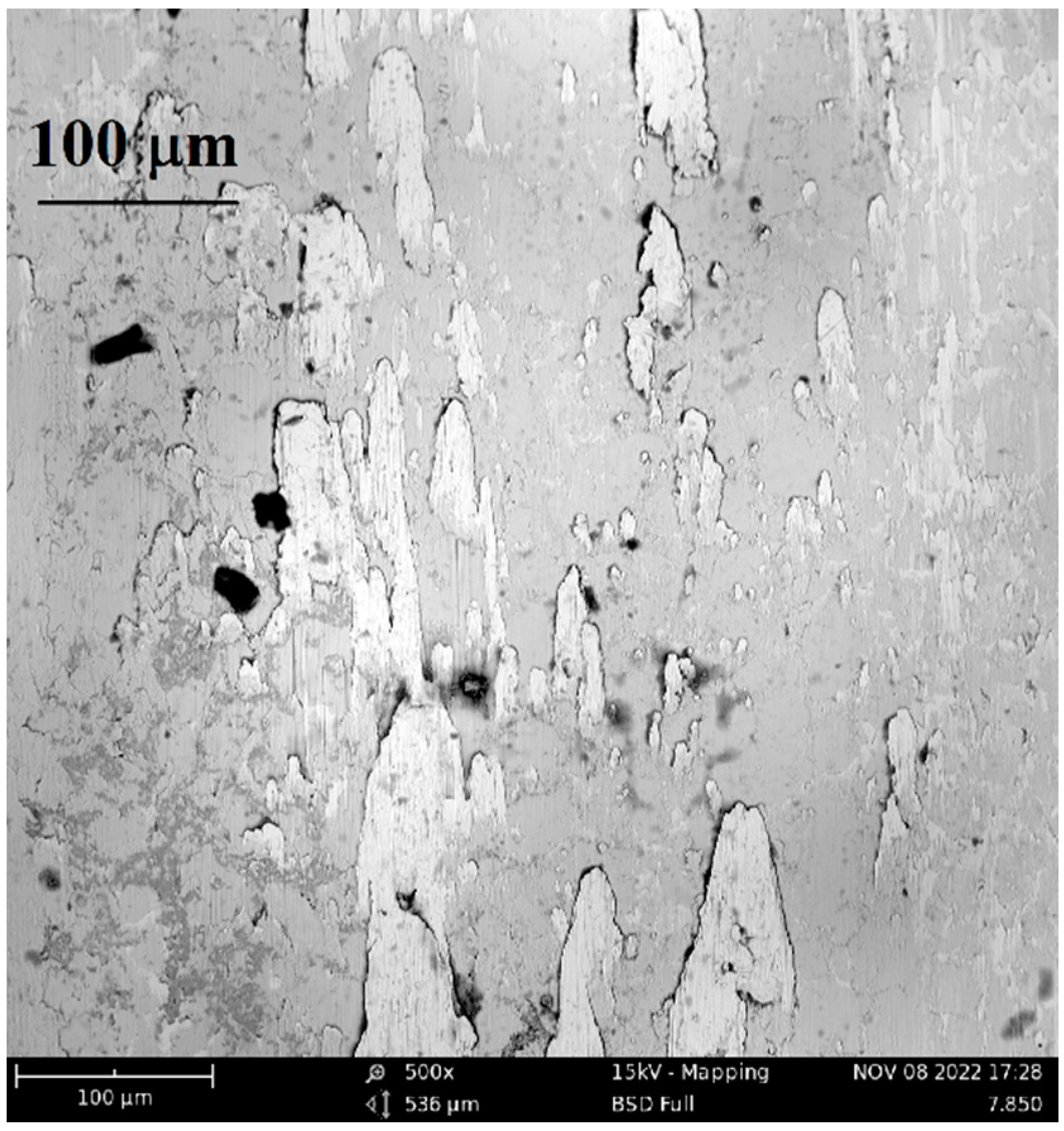

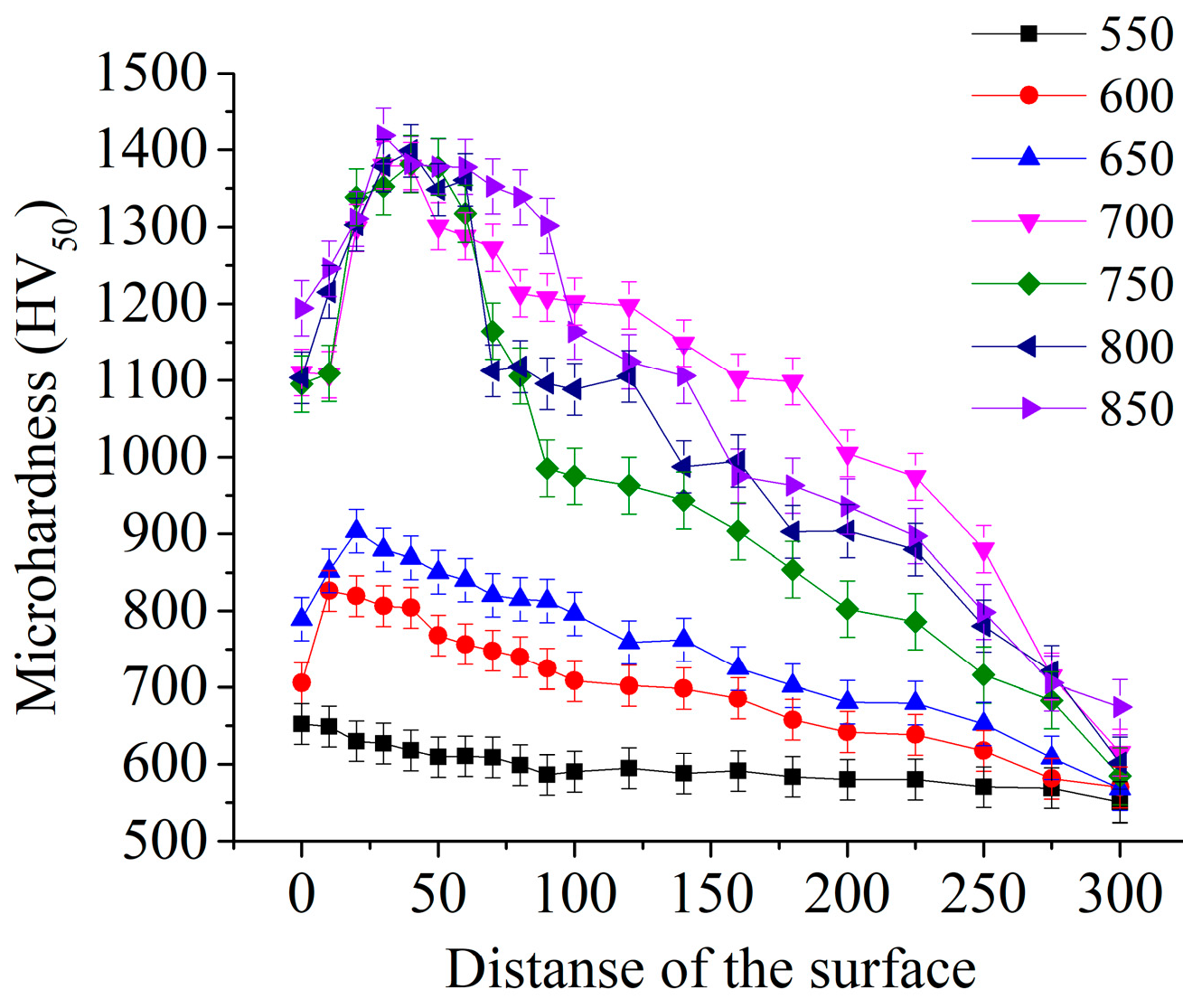

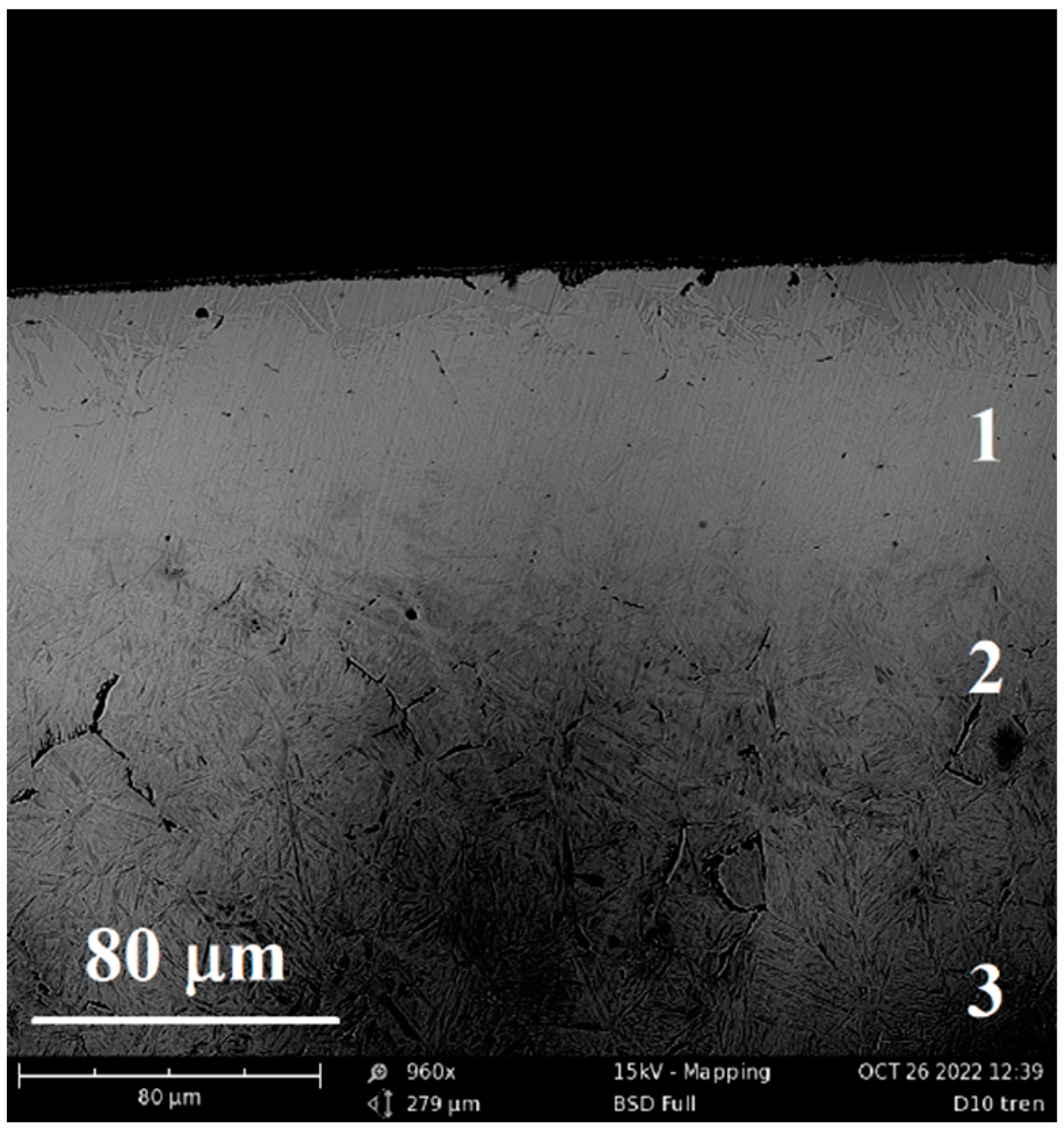

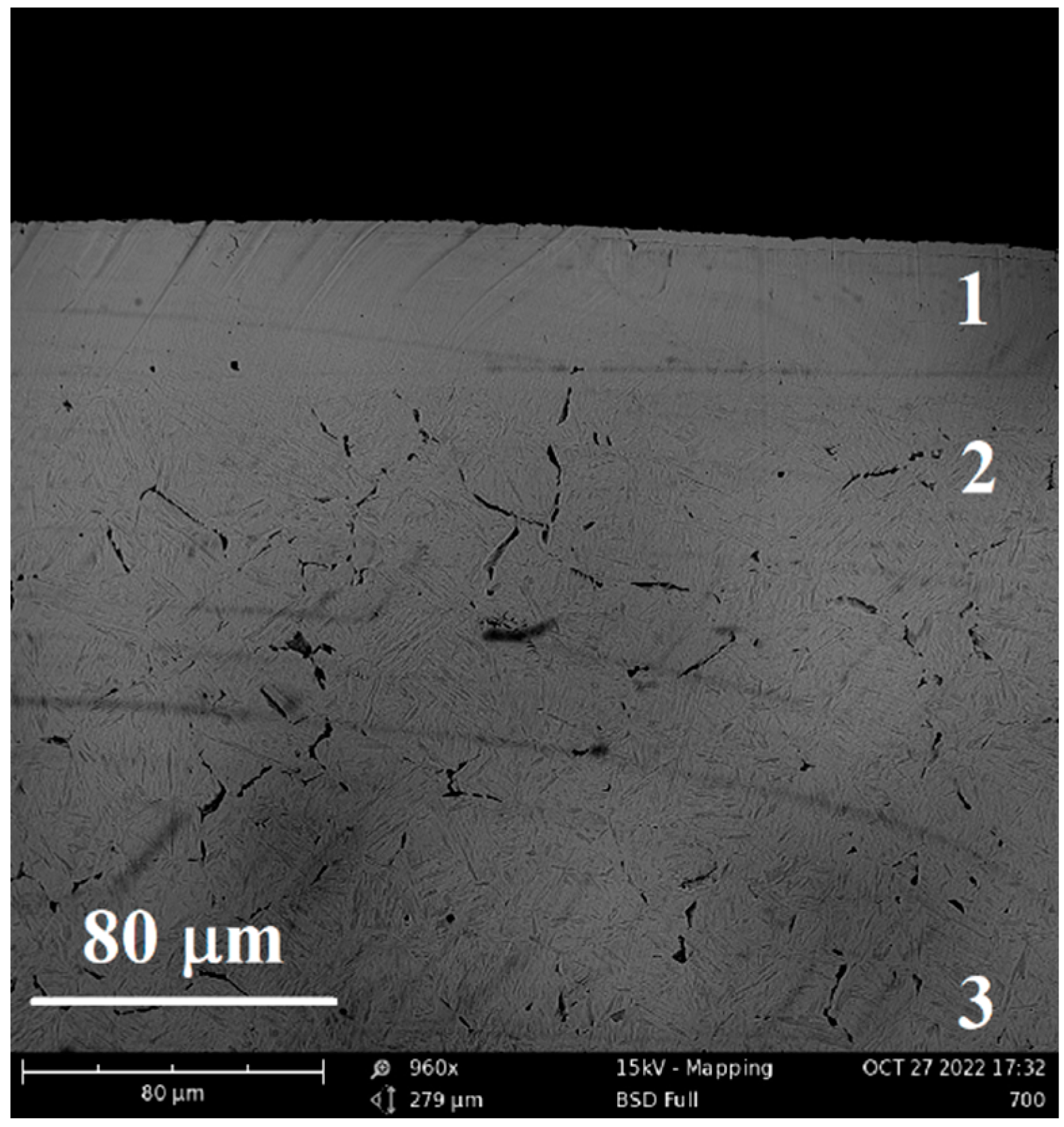

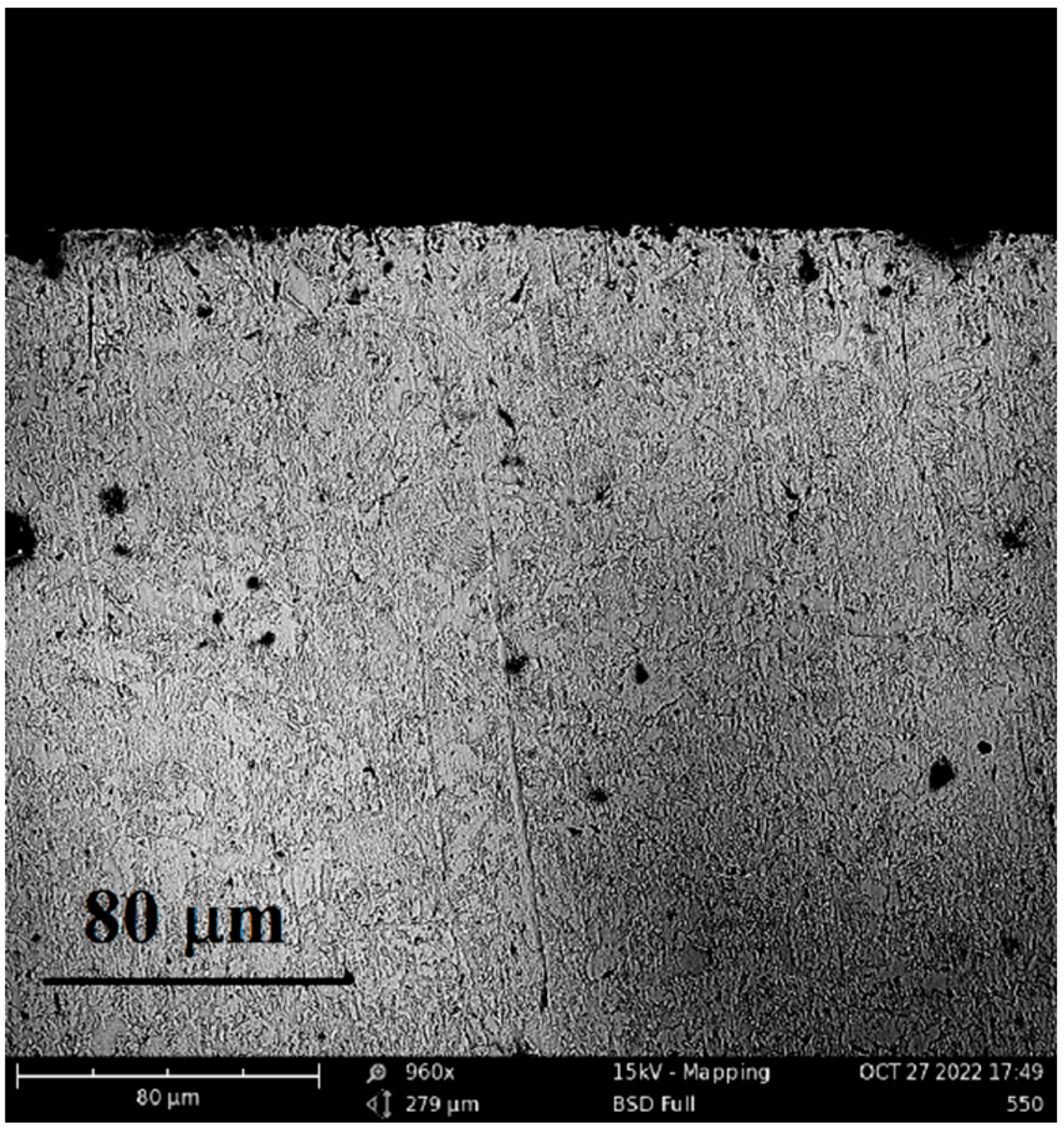

3.5. Structure and Microhardness of the Nitrocarburized Layer

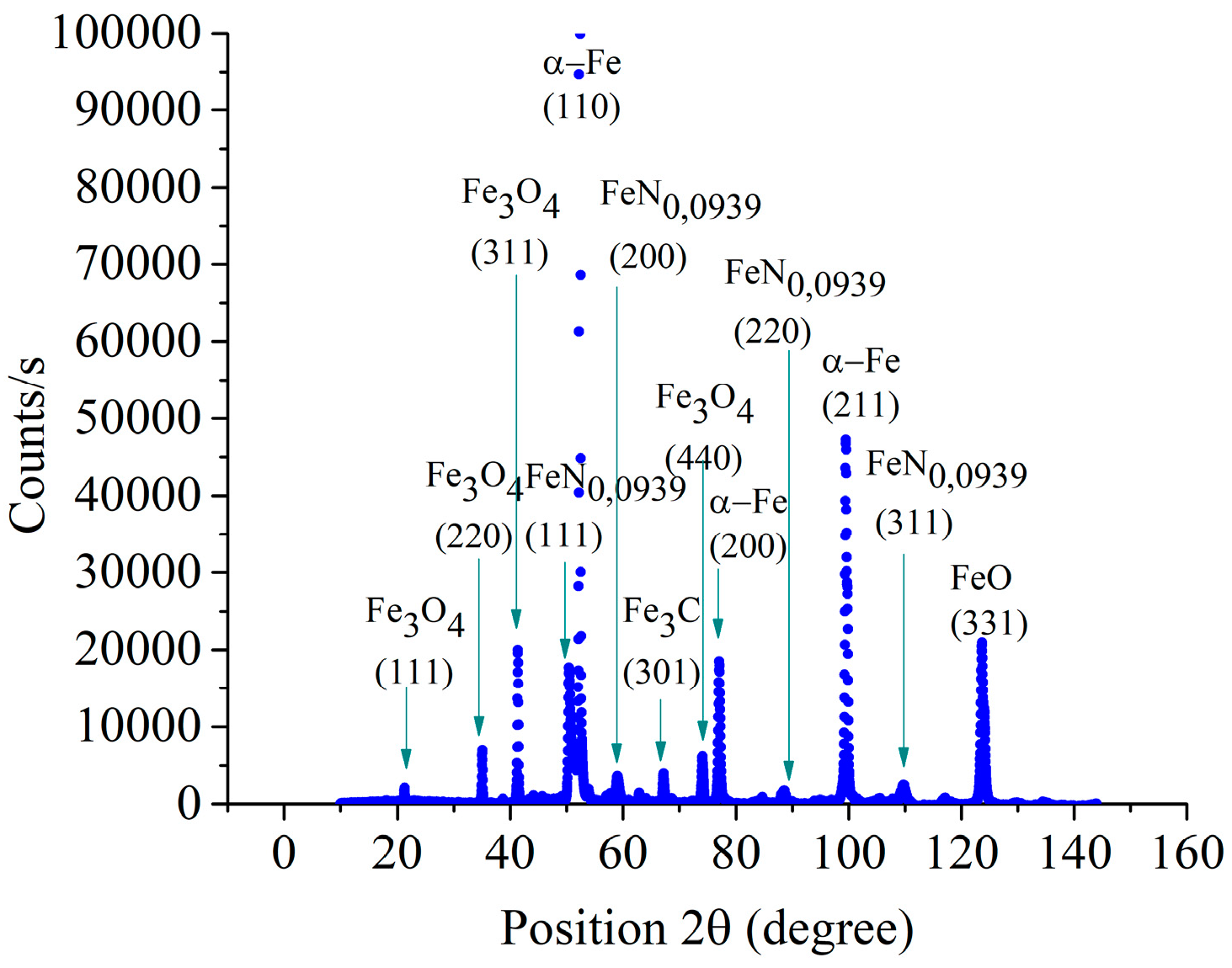

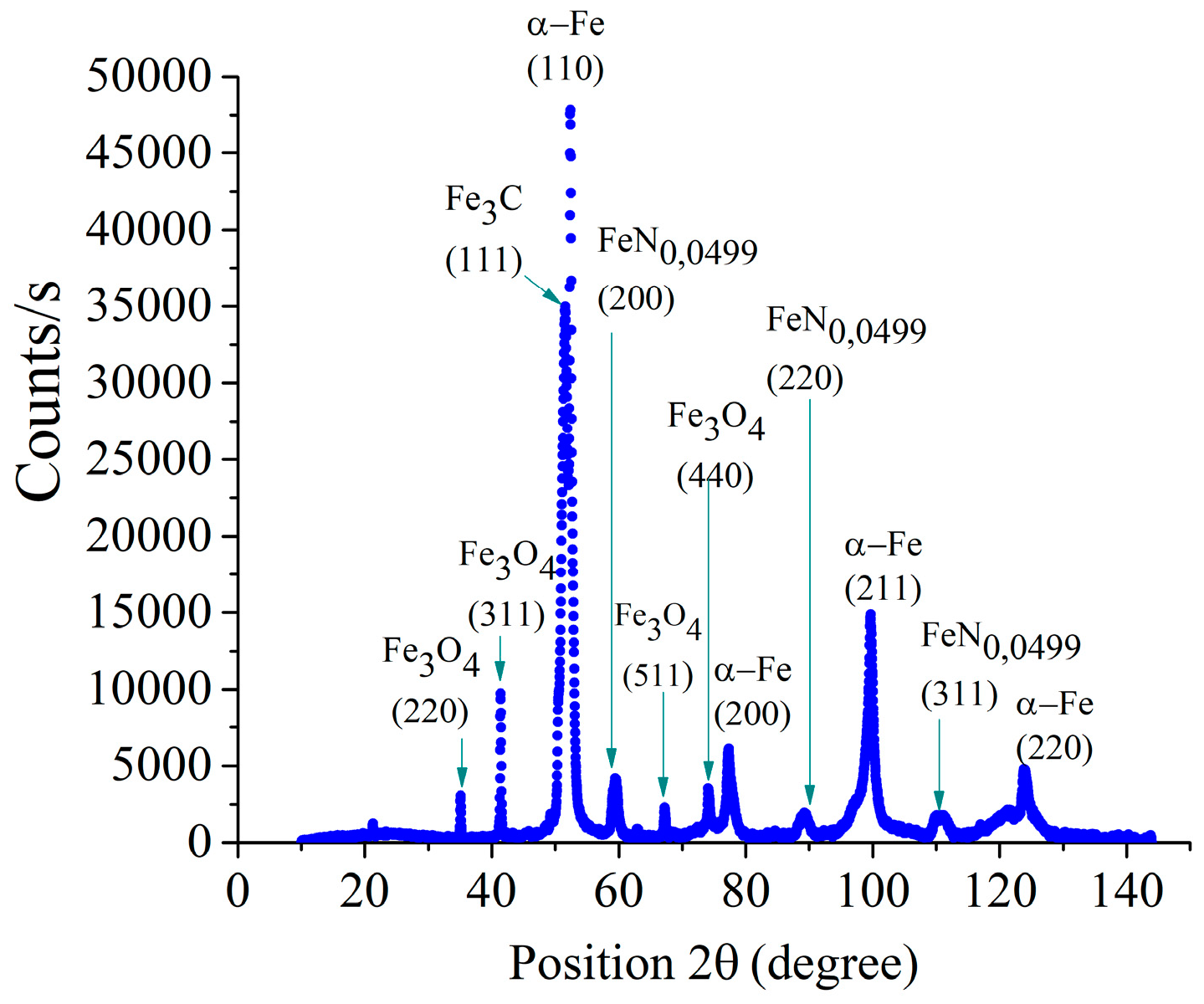

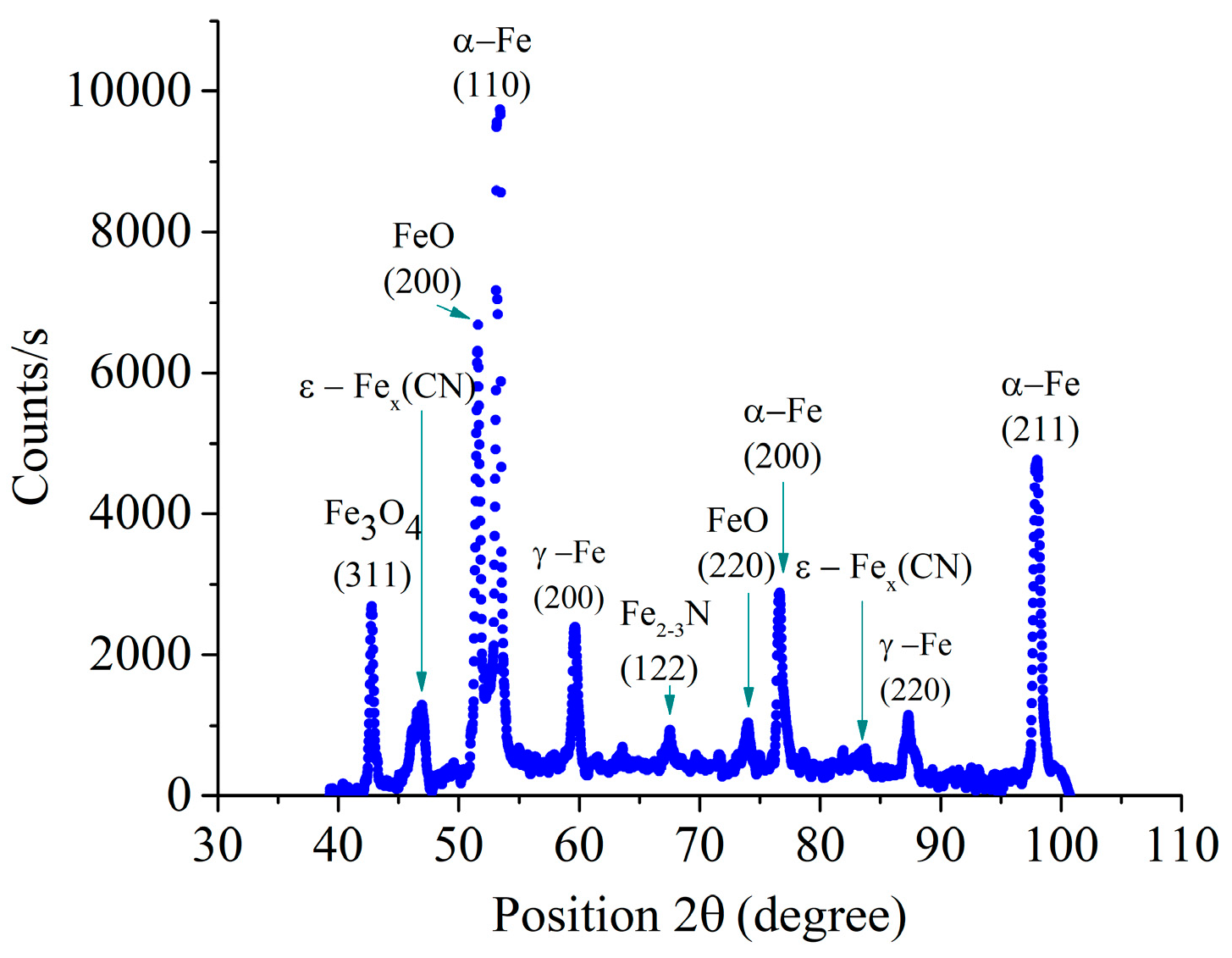

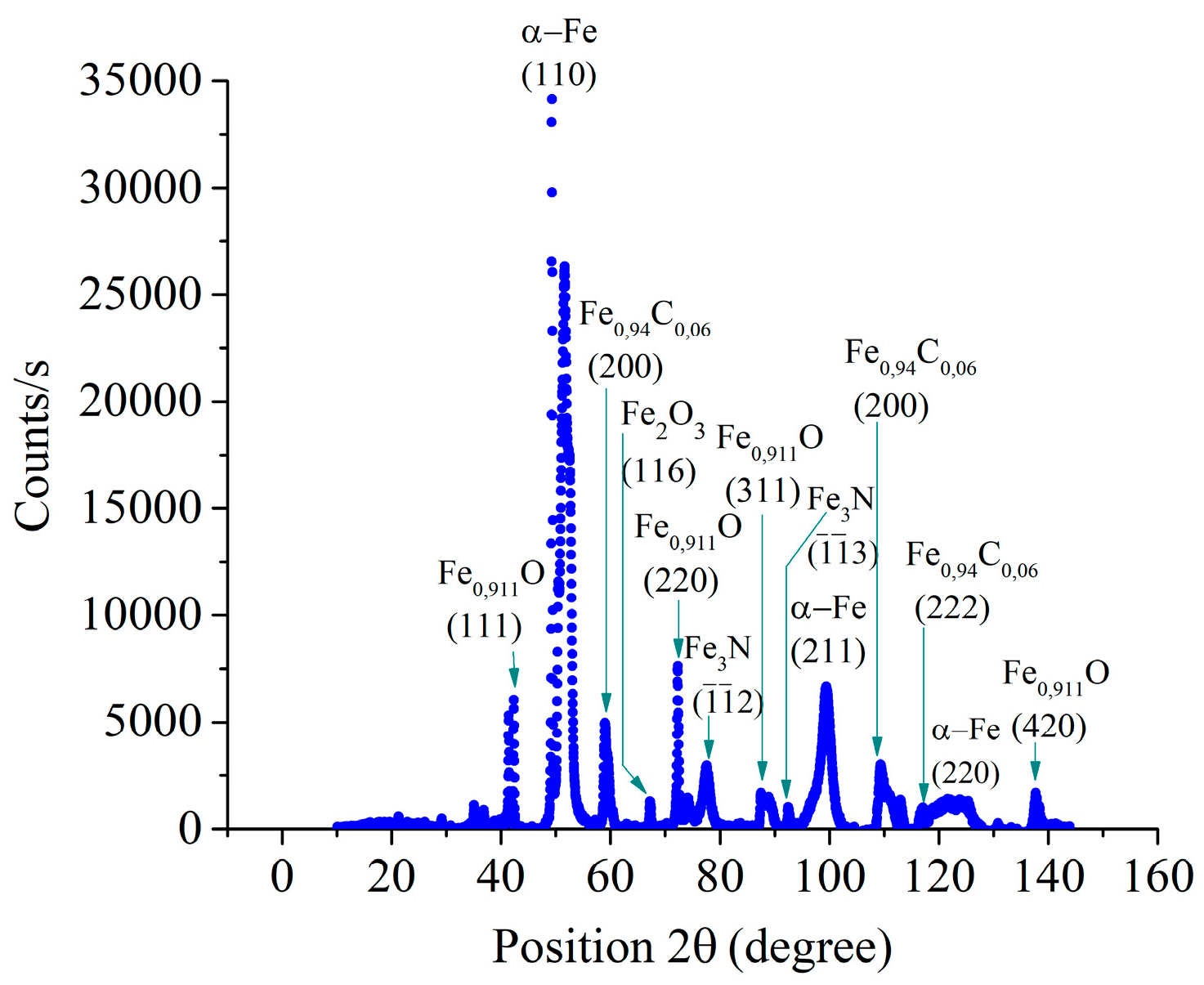

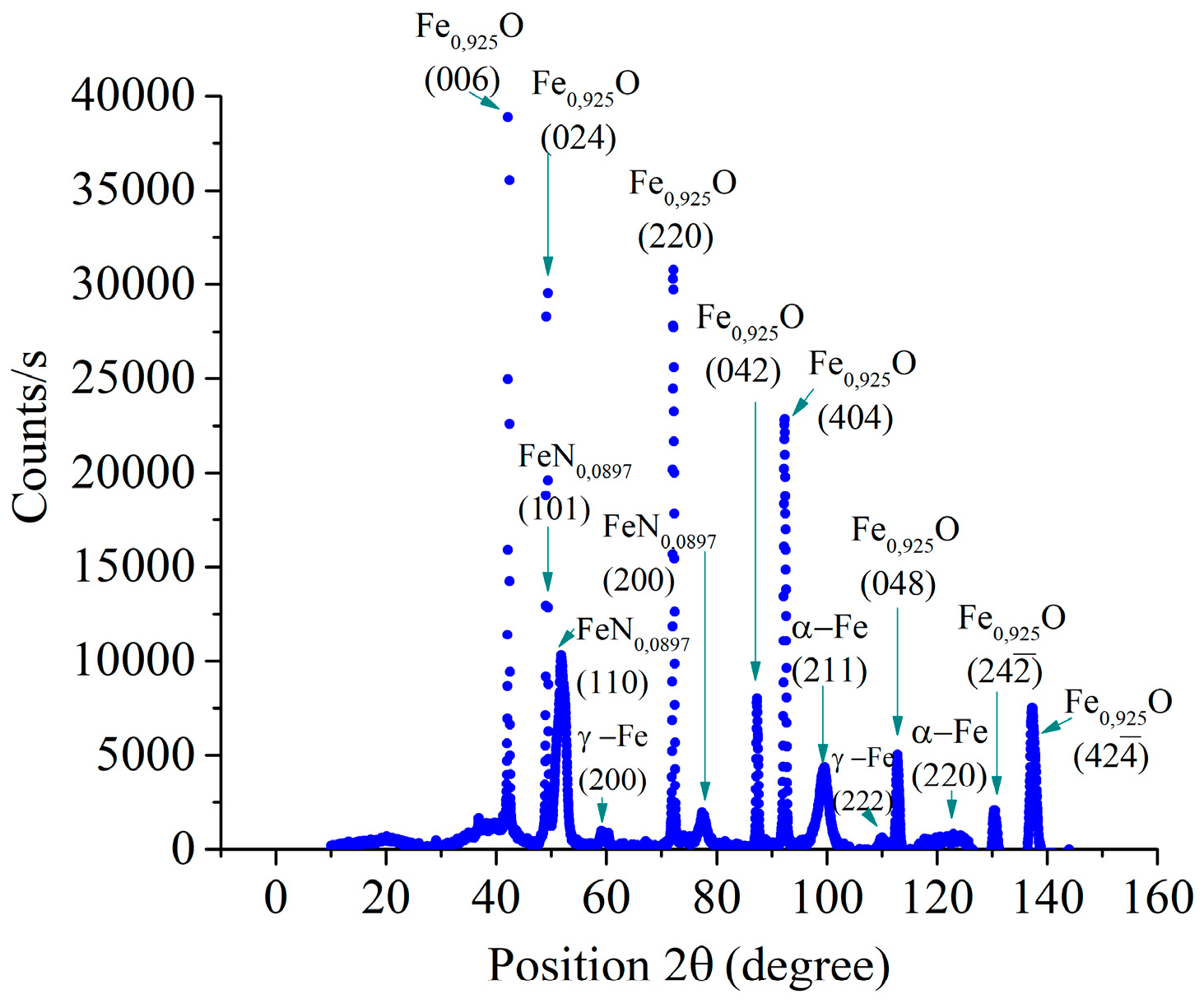

3.6. Phase Composition of the Nitrocarburized Surface

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Shugurov, A.R.; Kuzminov, E.D.; Garanin, Yu.A. Structure and Mechanical Properties of Ti-Al-Ta-N Coatings Deposited by Direct Current and Middle-Frequency Magnetron Sputtering. Metals 2023, 13, 512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shugurov, A.R.; Kuzminov, E.D. Mechanical and tribological properties of Ti-Al-Ta-N/TiAl and Ti-Al-Ta-N/Ta multilayer coatings deposited by DC magnetron sputtering. Surf. Coat. Technol. 2022, 441, 128582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mora-Sanchez, H.; Pixner, F.; Buzolin, R.; Mohedano, M.; Arrabal, R.; Warchomicka, F.; Matykina, E. Combination of Electron Beam Surface Structuring and Plasma Electrolytic Oxidation for Advanced Surface Modification of Ti6Al4V Alloy. Coatings 2022, 12, 1573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perez, H.; Vargas, G.; Magdaleno, C.; Silva, R. Article: Oxy-Nitriding AISI 304 Stainless Steel by Plasma Electrolytic Surface Saturation to Increase Wear Resistance. Metals 2023, 13, 309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marcuz, N.; Ribeiro, R.P.; Rangel, E.C.; Cristino da Cruz, N.; Correa, D.R.N. The Effect of PEO Treatment in a Ta-Rich Electrolyte on the Surface and Corrosion Properties of Low-Carbon Steel for Potential Use as a Biomedical Material. Metals 2023, 13, 520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belkin, P.N.; Kusmanov, S.A.; Zhirov, A.V.; Belkin, V.S.; Parfenyuk, V.I. Anode Plasma Electrolytic Saturation of Titanium Alloys with Nitrogen and Oxygen. J. Mat. Sci. Tech. 2016, 32, 1027–1032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belkin, P.N.; Kusmanov, S.A. Plasma electrolytic nitriding of steels. J. Surf. Investig. X-ray Synchrotron Neutron Tech. 2017, 11, 767–789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuzin, V.V.; Grigor’ev, S.N.; Volosova, M.A. Effect of a TiC Coating on the Stress-Strain State of a Plate of a High-Density Nitride Ceramic Under Nonsteady Thermoelastic Conditions. Refract. Ind. Ceram. 2014, 54, 376–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vereschaka, A.; Tabakov, V.; Grigoriev, S.; Sitnikov, N.; Milovich, F.; Andreev, N.; Bublikov, J. Investigation of wear mechanisms for the rake face of a cutting tool with a multilayer composite nanostructured Cr–CrN-(Ti,Cr,Al,Si)N coating in high-speed steel turning. Wear 2019, 438-439, 203069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grigoriev, S.; Vereschaka, A.; Milovich, F.; Tabakov, V.; Sitnikov, N.; Andreev, N.; Sviridova, T. Bublikov, J. Investigation of multicomponent nanolayer coatings based on nitrides of Cr, Mo, Zr, Nb, and Al. Surf. Coat. Technol. 2020, 401, 126258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Volosova, M.; Grigoriev, S.; Metel, A.; Shein, A. The Role of Thin-Film Vacuum-Plasma Coatings and Their Influence on the Efficiency of Ceramic Cutting Inserts. Coatings 2018, 8, 287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grigoriev, S.N.; Volosova, M.A.; Vereschaka, A.A.; Sitnikov, N.N.; Milovich, F.; Bublikov, J.I.; Fyodorov, S.V.; Seleznev, A.E. Properties of (Cr,Al,Si)N-(DLC-Si) composite coatings deposited on a cutting ceramic substrate. Ceram. Int. 2020, 46, 18241–18255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Apelfeld, A.; Borisov, A.; Dyakov, I.; Grigoriev, S.; Krit, B.; Kusmanov, S.; Silkin, S.; Suminov, I.; Tambovskiy, I. Enhancement of Medium-Carbon Steel Corrosion and Wear Resistance by Plasma Electrolytic Nitriding and Polishing. Metals 2021, 11, 1599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grigoriev, S.; Peretyagin, N.; Apelfeld, A.; Smirnov, A.; Morozov, A.; Torskaya, E.; Volosova, M.; Yanushevich, O.; Yarygin, N.; Krikheli, N.; Peretyagin, P. Investigation of Tribological Characteristics of PEO Coatings Formed on Ti6Al4V Titanium Alloy in Electrolytes with Graphene Oxide Additives. Materials 2023, 16, 3928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kusmanov, S.A.; Dyakov, I.G.; Belkin, P.N.; Gracheva, I.A.; Belkin, V.S. Plasma electrolytic modification of the VT1-0 titanium alloy surface. J. Surf. Investig. X-ray Synchrotron Neutron Tech. 2015, 9, 98–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belkin, P.N.; Borisov, A.M.; Kusmanov, S.A. Plasma Electrolytic Saturation of Titanium and Its Alloys with Light Elements. J. Surf. Investig. X-ray Synchrotron Neutron Tech. 2016, 10, 516–535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kusmanov, S.A.; Tambovskii, I.V.; Korableva, S.S.; Mukhacheva, T.L.; D’yakonova, A.D.; Nikiforov, R.V.; Naumov, A.R. Wear resistance increase in Ti6Al4V titanium alloy using a cathodic plasma electrolytic nitriding. Surf. Eng. Appl. Electrochem. 2022, 58(5), 451–455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mukhacheva, T.; Kusmanov, S.; Suminov, I.; Podrabinnik, P.; Khmyrov, R.; Grigoriev, S. Increasing Wear Resistance of Low-Carbon Steel by Anodic Plasma Electrolytic Sulfiding. Metals 2022, 12, 1641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kusmanov, S.A.; Kusmanova, Y.V.; Smirnov, A.A.; Belkin, P.N. Modification of steel surface by plasma electrolytic saturation with nitrogen and carbon. Mater. Chem. Phys. 2016, 175, 164–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tambovskiy, I.; Mukhacheva, T.; Gorokhov, I.; Suminov, I.; Silkin, S.; Dyakov, I.; Kusmanov, S.; Grigoriev, S. Features of Cathodic Plasma Electrolytic Nitrocarburizing of Low-Carbon Steel in an Aqueous Electrolyte of Ammonium Nitrate and Glycerin. Metals 2022, 12, 1773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shelekhov, E.V.; Sviridova, T.A. Programs for X-ray analysis of polycrystals. Metal Sci. Heat Treat. 2000, 42, 309–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grazulis, S.; Chateigner, D.; Downs, R.T.; Yokochi, A.T.; Le Bail, A. Crystallography open database—An open-access collection of crystal structures. J. Appl. Cryst. 2009, 42, 726–729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kragelsky, I.V.; Dobychin, M.N.; Kombalov, V.S. Friction and Wear Calculation Methods; Pergamon Press Ltd.: Oxford, UK, 1982; Available online: https://books.google.ru/books?id=QLcgBQAAQBAJ&hl=ru (accessed on 24 May 2023).

- Demkin, N.B.; Izmailov, V.V. Surface topography and properties frictional contacts. Trib. Int. 1991, 24, 21–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National standard of the Russian Federation. Geometrical Product Specifications (GPS). Moscow, Standartinform, 2015. http://docs.cntd.ru/document/1200116337.

- Mukhacheva, T.L.; Belkin, P.N.; Dyakov, I.G.; Kusmanov, S.A. Wear mechanism of medium carbon steel after its plasma electrolytic nitrocarburising. Wear 2020, 462–463, 203516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matlin, M.M.; Kazankina, E.M.; Kazankin, V.A. Calculation of the actual contact area between a single microasperity and the smooth surface of a part when the hardnesses of their materials are similar. J. Frict. Wear 2011, 32, 140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- I.V. Kragelsky, N.М. Mihin, Friction units of machines: Reference, Engineering manufacture, Moscow, 1984.

- Du, E.H., Van Voorthuysen Marchie, Boerma, D.O., Chechenin, N.C. Low-temperature extension of the Lehrer diagram and the iron-nitrogen phase diagram. Metallurgical and Materials Transactions. A. 2002. V. 33A.

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).