1. Introduction

Incorporating various kind of additives like addition of nanoparticles for providing a new feature such as self-cleansing, antimicrobial property, protecting the UV rays, wood safeguarding, antifouling paints, fire-retardant, corrosion preventing [Hincapie et al., 2015]. To avoid the effect of sea water or aquatic microorganism affecting the ship hulls, antifouling paints will be used [E. Almeida et al., 2007]. The development of antifouling paints began in the middle of the 19th century. This displayed good effectiveness and contained resin binders that contained, arsenic, mercury oxide and copper oxide. [J. Readman et al., 2006]. Tributyltin (TBT), an organic metal substance, was first utilised in the 1950s and for almost two decades was detected in a significant number of ships globally. [D. M. Yebra et al., 2004]. However, despite having been shown to have economic benefits, at low concentrations it has a detrimental effect on marine life. [L. Gipperth et al., 2009].

Copper nanoparticles is used as an antimicrobial material globally as it is able to reduce the reactions of disease spreading pathogens. It has some distinctive and promising features like microbicidal property [G. Borkow et al.,2010, G. Borkow et al.,2009], wound dressing [A.P. Kornblatt et al.,2016, J.J. Ahire et al.,2016] which are utilized in research work to gather more information about copper nanoparticles. With the same approach the outstanding physical properties of Cu NPs are exploited in antibiotic applications. mostly the antimicrobial materials are colloidal copper nanoparticles [J. Ramyadevi et al.,2012, N. Cioffi et al.,2005]. Copper has closely related properties when compared to silver, gold and other noble metals [Muhammad Sani Usman et al.,2012] which is used in various branch of studies like environmental technology, storage and energy conversion, biological application, and chemical manufacturing [M.B. Gawande et al.,2011, S. Laurent et al.,2008]. The bactericidal reaction of copper nanoparticles is enhanced by its size. The antimicrobial activity of copper nanoparticles is upgraded by the action releasing metal ions into the solution [N. Cioffi et al.,2005, J. Ramyadevi et al.,2012 and Q. Xu et al.,2006]

Copper nanoparticles has good durability on matrix of disinfectant material, overlay on medical devices and catalysts [E.K. Athanassiou et al.,2006, Mohammad W. Amer et al.,2020, J.A. Rodriguez et al.,2007], heat transfer systems [C. H. Li et al.,2006], sensor [M. Tiwari et al.,2014, M.L. Kantam et al.,2007, R. Narayanan et al.,2004] which helps in exploiting its antimicrobial activity in industries. As said before the copper nanoparticles shows excellent bactericidal activity, wound healing action and opposes the growth of wound pathogen pseudomonas aeruginosa. Copper nanoparticles enhances wound healing properties by neovascularisation, acceleration of skin migration and proliferation [S. Alizadeh et al.,2019]. Copper is one of the most important elements in food and nutrition for humans. The Cu+ ions plays role in the function of the immune system, growth and formation of the bone, transfer of iron from tissue to the plasma, myelin sheath formation in nervous system and also helps in the incorporation of iron in hemoglobin. Cu++ ions functions as a cofactor for various enzymes in the human body. However, Cu++ is one of the crucial trace elements for bacterial cells. These ions involve in the biosynthesis of metallic proteins, such as electron-transport proteins. However, the ionic form of the copper metal is hazardous. Existing copper particles may be bind by a low molecular weight substance, by changing or inhibiting their biological function and activity [N.L Brown et al., 1992].

High consumption or inadequate intake of copper has led to reduction of immune system in animal bodies which involves lymphocyte proliferation [M. Pocino et al.,1991], phagocytic activity and neutrophil numbers [M.I. Yatoo et al.,2013], Antibiotic resistance of E-coli in pigs [G. E. Agga et al.,2014] and in dairy cows [R. W. Scaletti et al.,2012]. It can be reduced by copper supplementation where Cu deficiency has lower lymphocytes [M. Tiwari et al.,2014]. Copper helps in great body and physiological functions so it is used in antibiotics and other pharmacological formulations. Previously, methanolic root of the plant and Copper nanoparticles synthesised from the presence of root extract has been reported [Subha et al., 2022]. In this experiment we evaluate the antibacterial activity of biologically synthesized copper nanoparticles from the root extract of Asparagus racemosus by confirming the formation of copper nanoparticles through the following analysis- ultra violet spectroscopy, X-ray diffraction analysis, FTIR, zeta potential. The chemical constituents present in Asparagus racemosus has promoted the use of Cu NPs as antibacterial material. The copper nanoparticles synthesised from root extract shows a distinguishable peak at 650nm.The presence of carbohydrates can be confirmed by, Fehling’s test, Benedict’s test, Bial’s test, Molisch’s test Seliwanoff’s test, Barfoed’s test. FTIR analysis shows the presence of phytosteriods such as shatavarin I-IV. The biological synthesizing process does not require the use of high toxic chemicals, put up high pressure or temperature [A.K. Singh et al.,2010, S. Rajeshkumar et al.,2012].

2. Methods and Materials

The Chemicals used in the experiment were bought from SISCO Research Laboratories, Maharashtra and Villivakkam. Chemicals like Copper (II) sulfate, Asparagus racemosus were used without further modification. Double distilled water was used as aqueous solution.

2.1. Plant description

Shatavari the queen of herbal plants is a climber medicinal plant with scientifical name Asparagus racemosus. It belongs to the family Asparagaceae and species Asparagus. almost it grows under the temperature 25-400C [Arti Sharma et al.,2013] almost throughout the India [Jai Narayan Mishra et al.,2017]. Most of the parts of this plant has great medicinal use [R.N. Chopra et al.,1994]. The roots are used for the pharmacological studies where it is used in powdered form which is odorless and pale yellow in colour [Pooja Shaha et al.,2017]. In India, Asparagus racemosus plays a major role in medicinal use where Vitamin is the source [Sapna Thakur et al.,2018] and health tonics are made from root extracts of Shatavari. Various diseases and illness like menorrhagia and leucorrhoea [Anurag Mishra et al.,2015], [J.P. Kamat et al.,2000] antioxidant, dysentery and immune-modulatory activities, antiulcer activity, anti-diabetic and anti-diarrhoeal, female infertility, menopause related problems. It also boosts the good property in Galactagogic, regulates the immune system and decreases the response of inflammatory. It builds up protective antibodies to counter vaccines thus leading to protection from various diseases, bacterial and viral infections.

2.2. Chemical constituents

Asparagus racemosus has shatavarin I- shatavarin IV which are hold by essential bioactive components namely Steroidal saponins [S. Sharma et al.,1982, M. Tandon et al.,1990]. In Asparagus racemosus the shatavarin-IV component is made up of two molecules- glucose and asparagus rhamnose which is found in fruits, roots and leaf of the plant [Amit Chawla et al.,2011]. Traces of some elements like selenium, copper, manganese, calcium, cobalt, and potassium are found in this plant [B. Mohanta et al.,2003], and also the fruits and roots have been noted to contain steroidal saponins, glycosides of hyperosides, quercetin and Rutin which are the flavonoid [S. Sharma et al.,1984].

2.3. Preparation of ethanolic root extracts of Asparagus racemosus

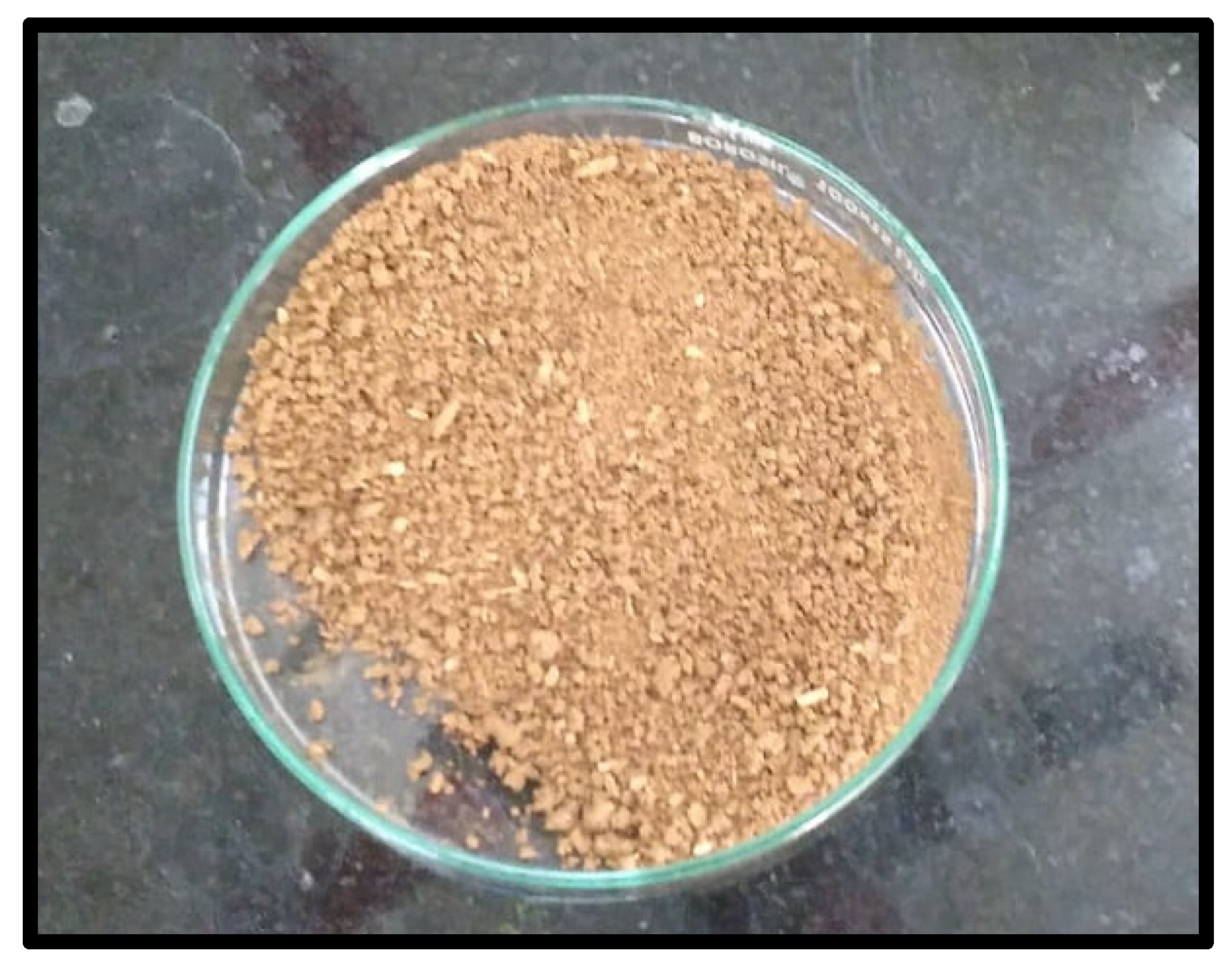

Dried roots of

Asparagus racemosus is collected and dried and later grinded into powder with mortar and Pestle. 5g of plant root powder was taken and soaked in 70% of ethanol (70ml ethanol and 30ml of water) for 24 hours or 12 hours. The solution was boiled for 30 minutes in a glass flask and cooled to room temperature. The filtrate was collected after filtering using WhattmanNo.1 filter paper and stored at 40

0 C for future use. The root powder and root extract of

Asparagus racemosus is displayed in

Figure 2 and

Figure 3.

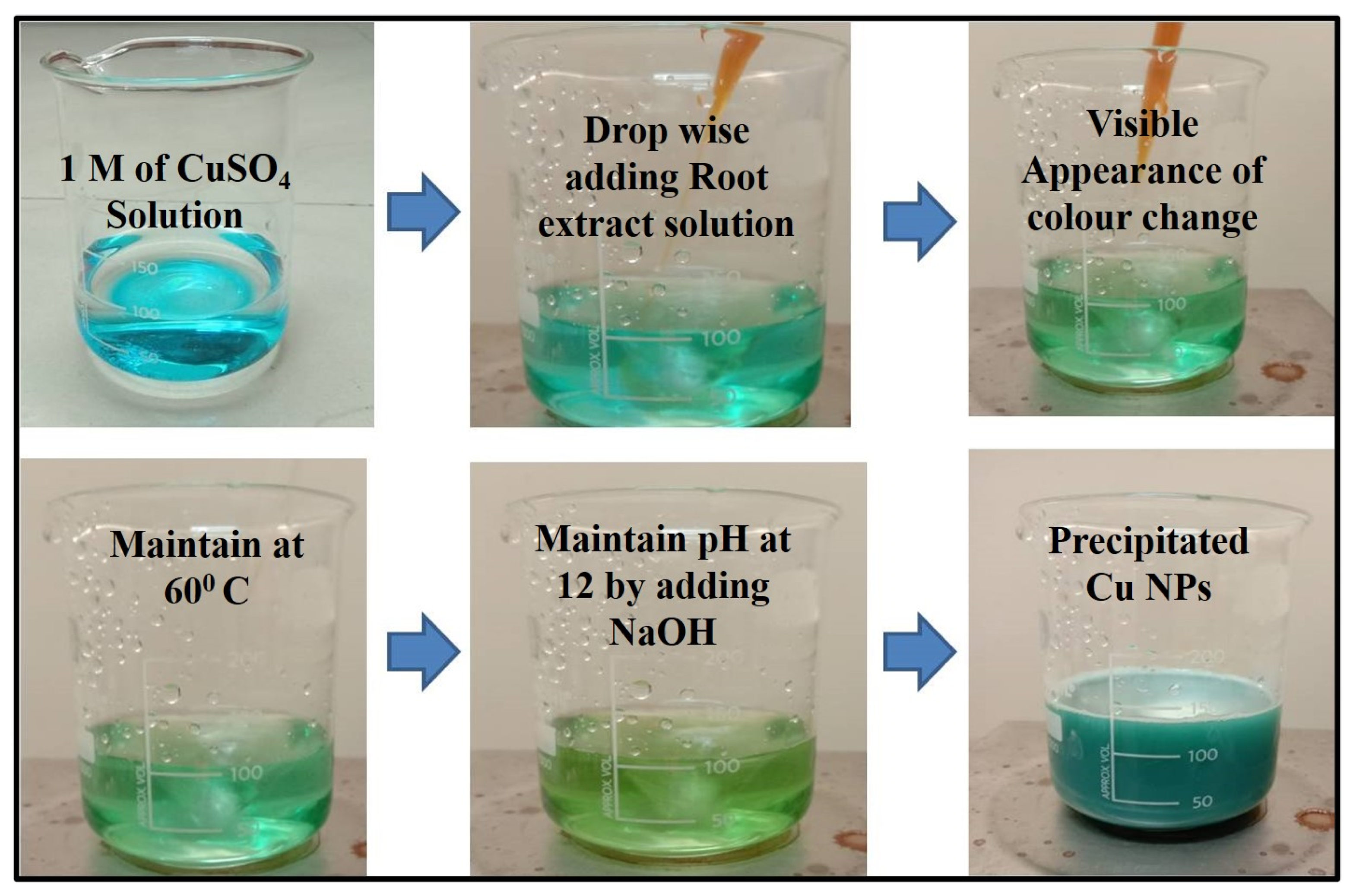

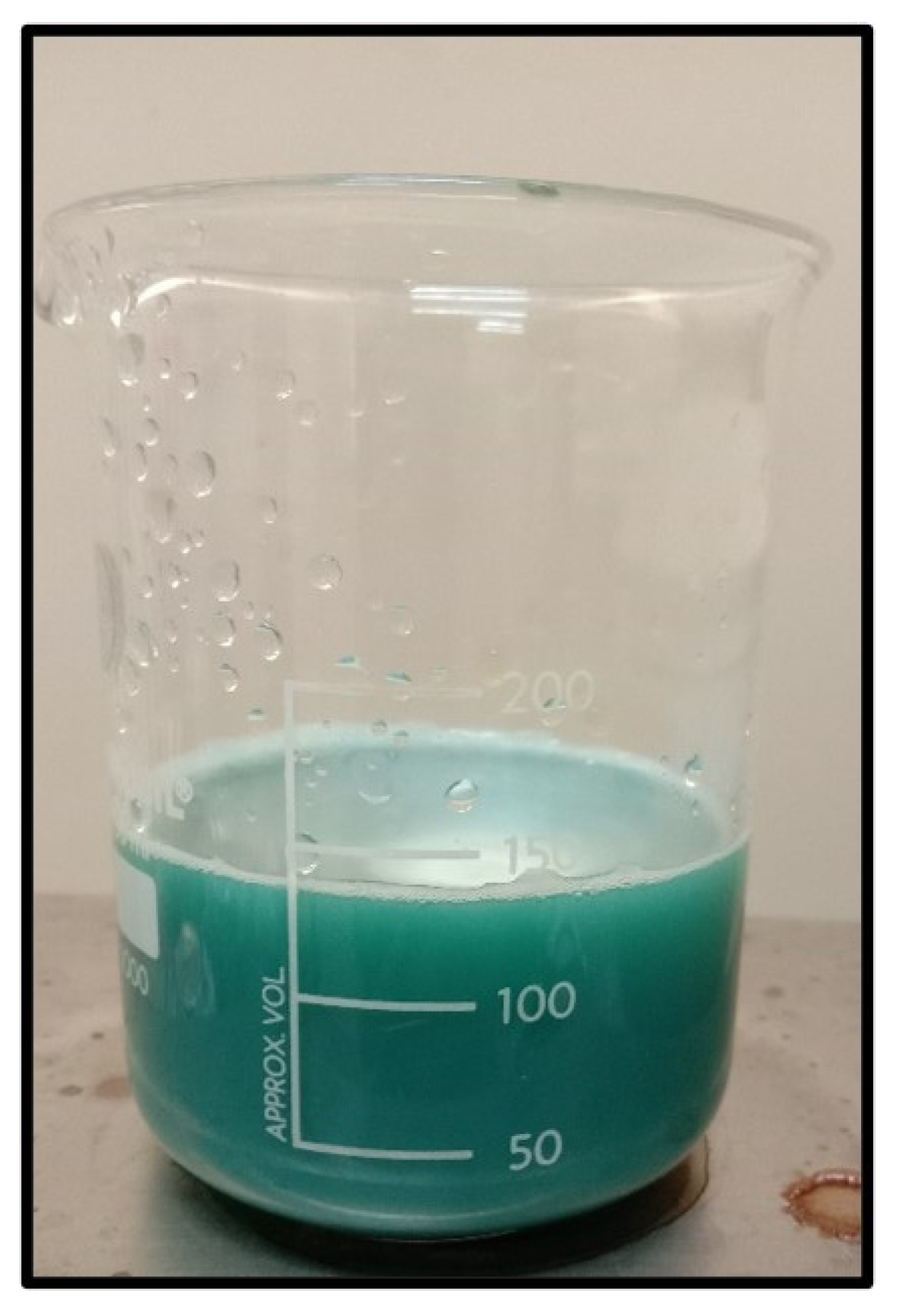

Figure 1.

Synthesis of Copper nanoparticles using root extract of A. racemosus.

Figure 1.

Synthesis of Copper nanoparticles using root extract of A. racemosus.

Figure 2.

Asparagus racemosus root Powder.

Figure 2.

Asparagus racemosus root Powder.

Figure 3.

Root extract of Asparagus racemosus.

Figure 3.

Root extract of Asparagus racemosus.

2.4. Preparation of copper nanoparticles

Copper sulphate solution was used to synthesize copper nanoparticles which is 1M (one molarity) of CuSo

4.5H

2O dissolved in 100ml of distilled water. 5ml of root extract (reducing agent) was added to the solution and constantly stirred for few minutes. NaOH was added dropwise to adjust the pH level to 12. The blue color of the solution changes to green in this process. Leave it for 4 to 5 hours, so that the particles settle down at the bottom of the beaker with clear solution on top. The particles which settled down were the copper nanoparticles which were collected and supernatant (clear solution) was discarded. These collected nanoparticles were dried in 80

0C.

Figure 4. Represents the biosynthesized copper nanoparticles.

3. Results and Discussion

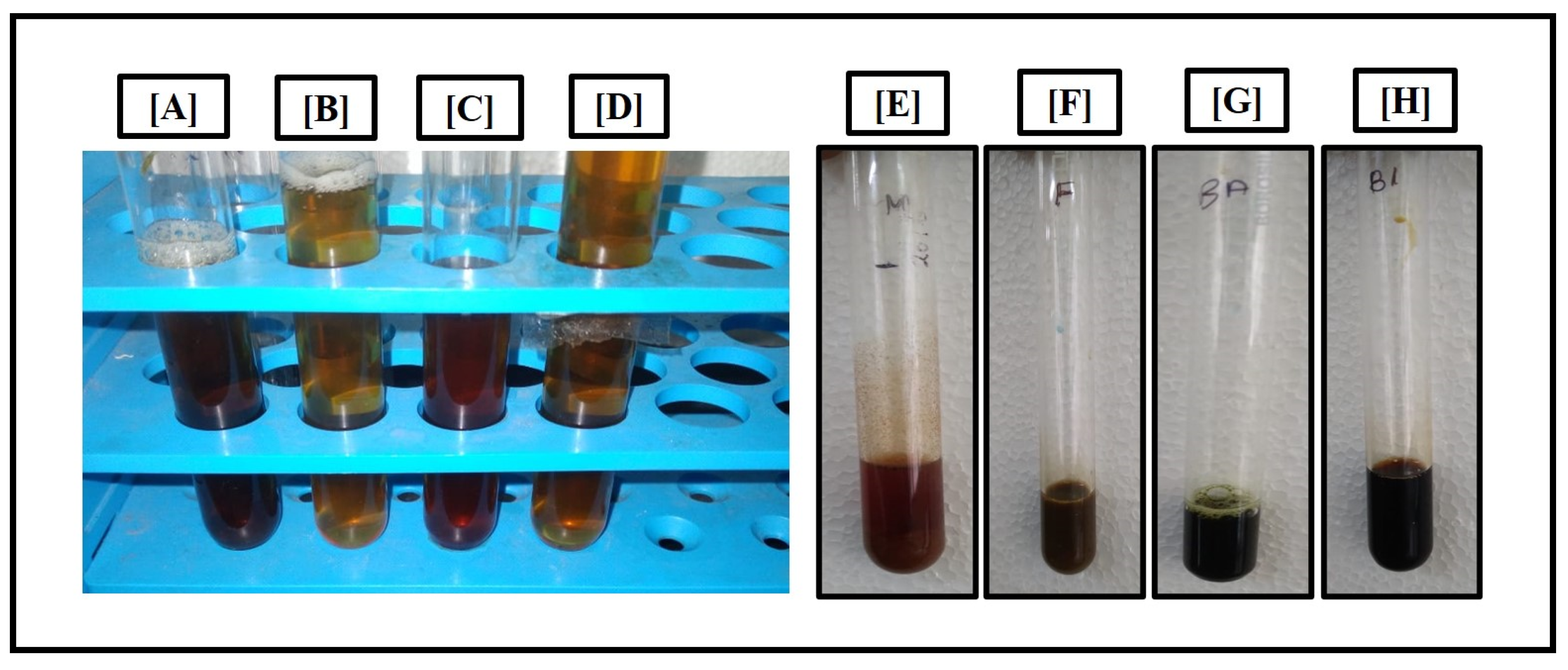

3.1. Test for Phytochemicals and carbohydrates

3.1.1. Test for Flavonoids

The presence of flavonoids in the plant extract was detected by the change of intense yellow color when added 2 ml of 2 % NaOH solution into the plant extract. It confirms the flavoids in the extract. It was authenticated by adding 2 ml of HCl to the solution resulting the disappearance of the color.

3.1.2. Test for Alkaloids

To 2ml of plant extract, 2ml of Mayer’s reagent was added. Appearance of a creamy cloud precipitate indicates the positive test for alkaloids.

3.1.3. Test for Saponins

To 2 ml of plant extract, 10 ml of distilled water was added. The test tube was stoppered and shaken well for 5 min. Allow it to stand for 30 min. The presence of a honeycomb froth indicates the positive test of saponins.

3.1.4. Test for Phenols

To 2 ml of plant extract, a few drops of fecl3 was added. Appearance of a purple or red precipitate indicates the positive test for phenols.

3.1.5. Molisch’s test

2 drops of α-naphthol solution were added to 2ml of test solution and H2SO4 (conc.) was added slowly along the sides of the test tubes. Appearance of violet color confirms the test.

3.1.6. Fehling’s test

2 ml of test solution was added to a mixture of equal amounts of Fehling A & Fehling B solution and raised to its boiling temperature. Appearance of brownish-red or yellow precipitate of cuprous oxide confirms the presence of reducing sugars.

3.1.7. Bial’s test

The pentose sugar in the plant extract was confirmed by the adding of 5ml of Bail’s reagent to the plant extract and allowed for boiling the given solution in a water bath. As a result, blue green color was appeared to authenticate the pentose sugar in the extract.

3.1.8. Barfoed’s test

2-3ml of Barfoed’s reagent was added to 2ml of test of test solution and kept in boiling water bath. Appearance of red precipitate of cuprous oxide at the bottom of the container confirms the presence of monosaccharides.

The following test shows the presence of carbohydrates in root extract represented

Figure 5. Carbohydrates, fats and proteins are the macronutrients present in plants. When consumed carbohydrates are metabolized into glucose and simple sugars and used for energy requirements.

Asparagus has many phytochemicals, other than carbohydrates.

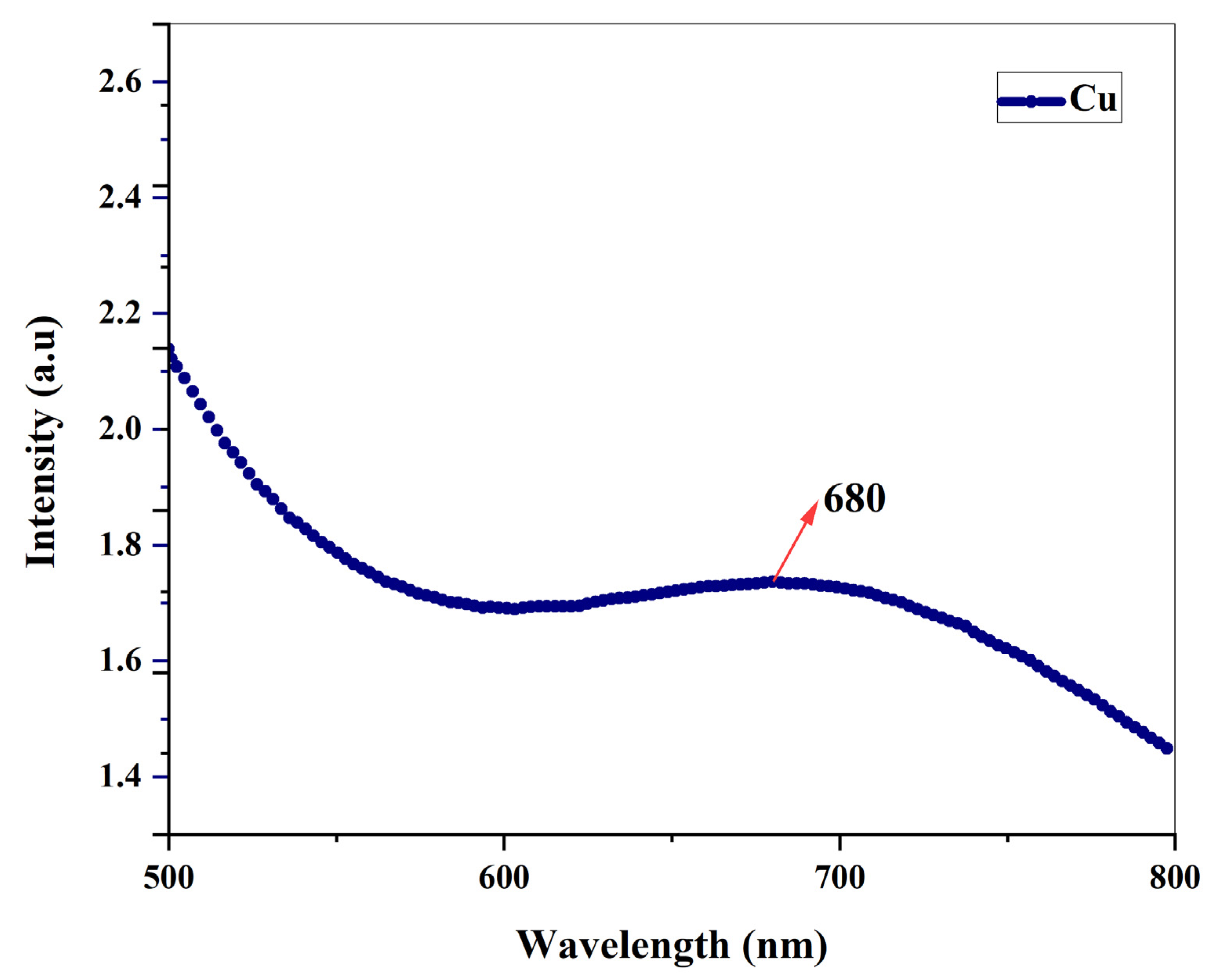

3.2. Ultraviolet spectroscopy

By using ultraviolet spectroscopy, it was possible to track how the root extract of Shatavari reduced copper sulphate ions into copper nanoparticles. The sample's absorbance spectrum was determined to be between 500 and 800nm. When copper nanoparticles are produced using NaOH without the addition of

A. racemosus root extracts, a single bend-like peak appears at 589 nm, was already discussed in our previous work [Subha et al., 2022] whereas when copper nanoparticles are synthesized using ethanolic root extract, a pronounced peak appears at 680 nm, indicating the presence of copper nanoparticles. The peak was only appeared after the addition of

A. racemosus root extract, and samples that did not contain root extract did not exhibit a peak, indicating that the plant's ethanolic root extract was the primary factor in the bio-reduction of copper ions into copper oxide nanoparticles. UV absorbance of copper NPs can be seen in

Figure 6. According to earlier research studies, Cu-NPs exhibit UV absorbances between the wavelengths of 570-700 nm [G. Caroling

et al.,2015].

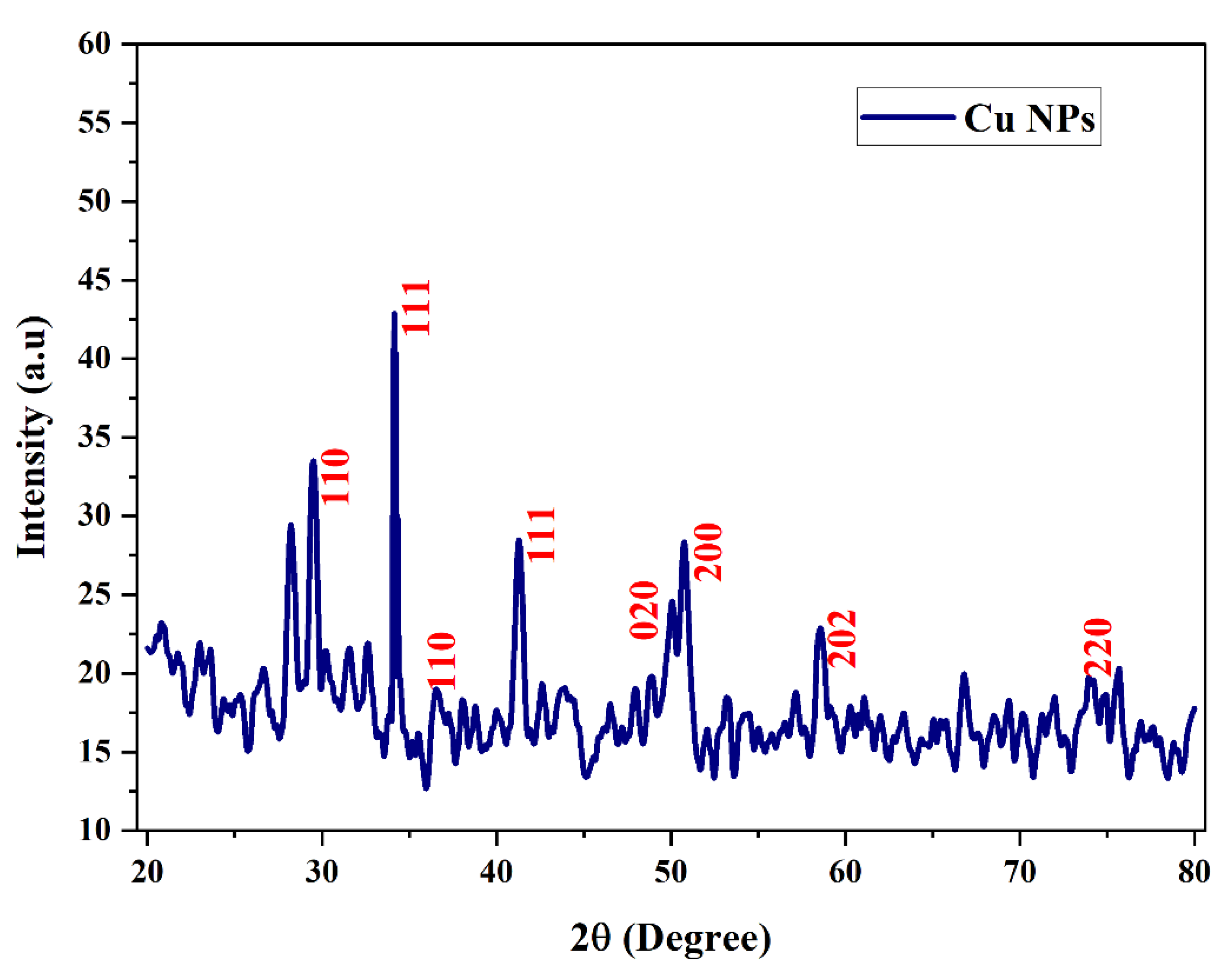

3.3. X-ray Diffraction

Figure 7 shows the XRD spectrum of copper nanoparticles with root extract. XRD peaks were indexed with the help of these JCPDS files (JCPDS card no: 89-5899). The X-ray diffraction patterns were used to confirm the size of a crystalline particle, crystalline phase and structure of synthesized copper nanoparticles. The Miller indices value (111) was supported using the high intensity peak created by the biosynthesized Cu-NPs at 34.16

0. The biosynthesized Cu-NPs shows a peak with high intensity, the 2θ and hkl values corresponding to

Figure 6. is 29.49

0, 34.16

0, 36.52

0, 41.28

0, 50.08

o, 50.76

o, 58.76

o,75.68 corresponding to (110), (111), (110), (111), (020), (200), (202) and (220) represents the monoclinic structure of copper. The position of the crystalline peak validates the purity of the synthesized Cu nanoparticles like in the case of copper oxide. The crystallization of bioorganic components on the surface of the nanoparticles can correspond to the display of the unassigned peaks. This evidently demonstrates that the Shatavari root extract shields them from rusting [ G. Caroling et al.,2015].

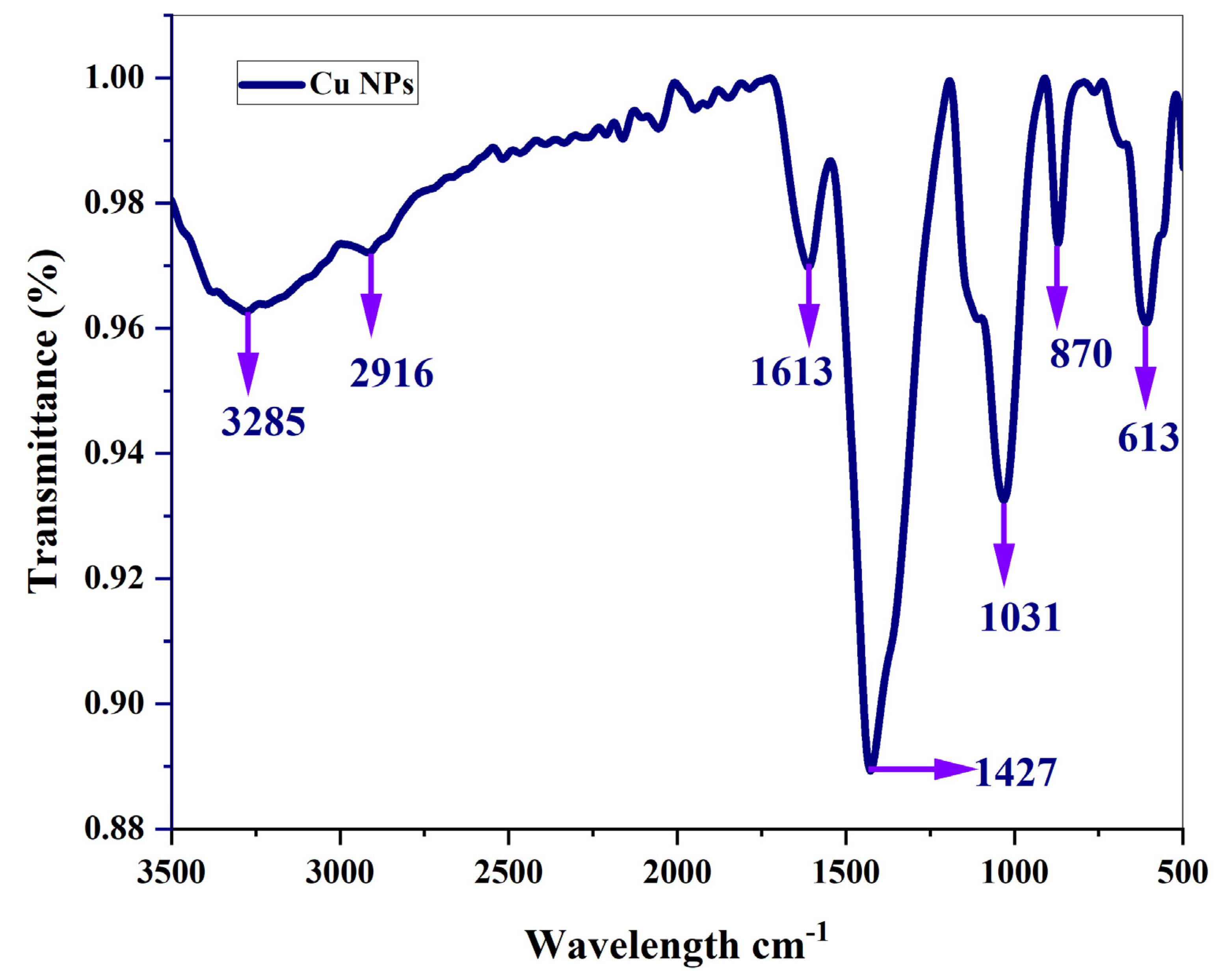

3.4. Fourier transformation infra-red spectroscopy

The obtained peak for copper nanoparticles which is synthesized from ethanolic root extract of

A.R with the absence of root extract of Cu NPs has been compared [Subha et al., 2022]. The presence of tannins and flavonoids can be understood by the presence of bands at 3275 cm

–1 Figure 8. This is caused by the O–H stretching mode of H-bonded compounds. The ν(C–H) stretching mode of methylene corresponds to the peaks recorded at 2916 cm

–1. This samples have strong absorption peaks at 1613 cm

–1 which may be due to C = O vibration present in lipids. As seen in the figure, Peaks centred around 1427 cm

–1 can be attributed to the C–H bending mode of lignin. Absorption peaks recorded at 1031 cm

–1 may be due to polysaccharides. The peak appearing at 1031 cm

–1 may be associated with the presence of carboxylic acid in a powder sample. This demonstrates that the sample exhibits the presence of

Asparagus racemosus active Phytoconstituents. It has been discovered that carboxylic acid is a key pharmaceutical ingredient in the treatment of edema, rheumatoid arthritis, jaundice, stomatitis, liver pain, ulcers, headaches, and fever, in addition to also resisting damage caused due to radiation. For oral administration,

Asparagus racemosus Willd Root is more suited and may end up being a more effective herbal remedy. The broad bands appearing at 567 cm

–1 and 600 cm

–1 respectively are attributed ring deformations for phenyl compounds present in the samples. The results of the FTIR confirm the presence of phytosteriods such shatavarin I–IV. This outcome demonstrates the involvement of phytosteriods in the reduction of Cu ions. Using the FTIR data, the functional groups and their molecules are identified. In this approach, phytosteriods aid in reducing PCOS, and shatavarin acts as an endometrial restorer. Shatavari, also known as “female tonic”, which is a key component, nourishes the ovaries and, by fostering growth, revitalizes its function and enriches ovulation. It also strengthens the female reproductive system and regulates the monthly cycle.

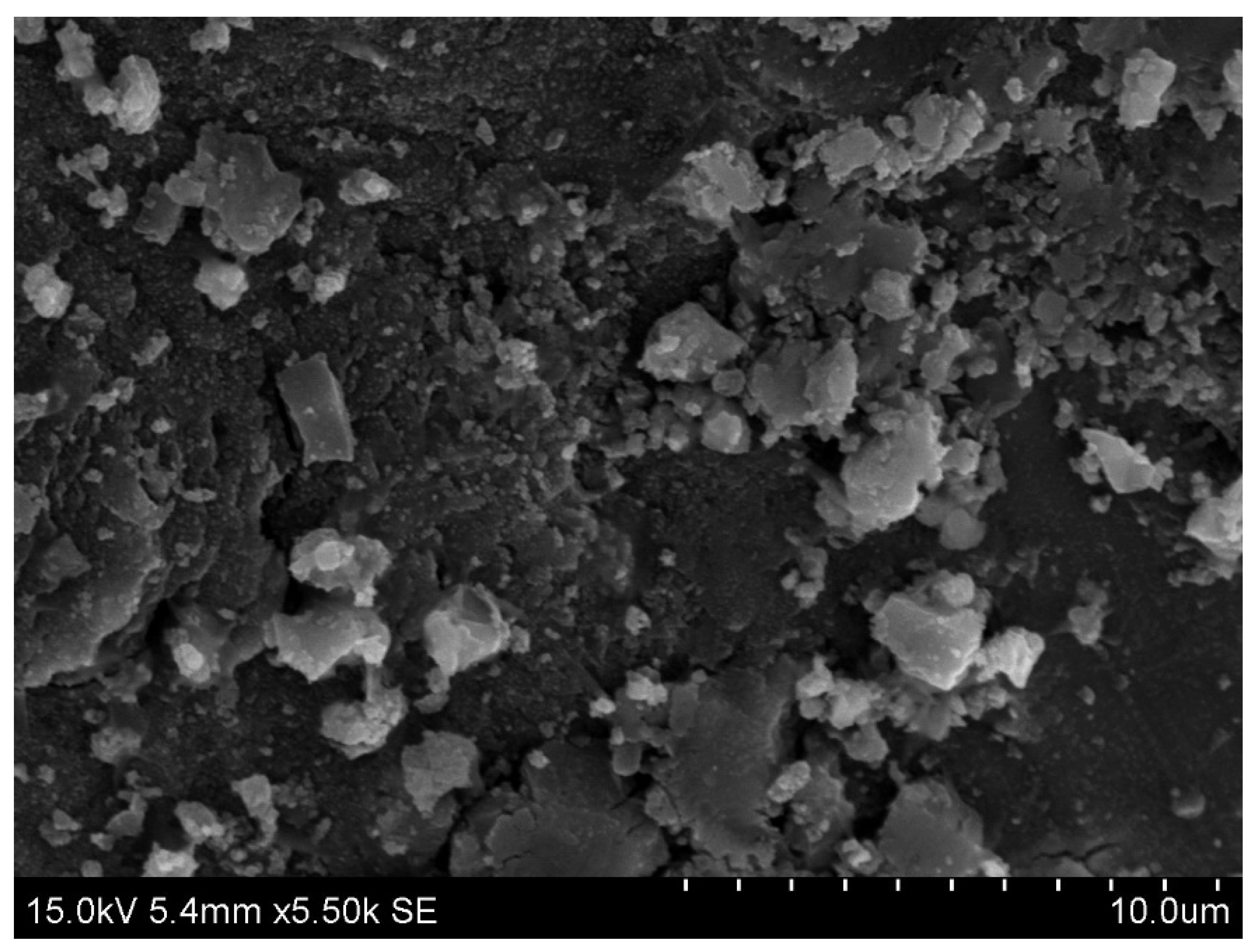

3.5. Scanning electron microscope

Figure 9 shows a scanning electron micrograph of the obtained nanoparticles. The micrograph demonstrates that the particles have a spherical form. Synthesized particles appear as bigger particles rather than as separate units. Cu nanoparticles range in size from 60 nm to 300 nm. The resulting SEM picture reveals that the product is mostly constituted of small sized Copper nanoclusters [Subha Veeramani

et al., 2017]. High magnification inspection, however, reveals that the smaller nanoparticles that make up these Cu nanoclusters have excellent homogeneity and uniformity with an average diameter of roughly 40 nm.

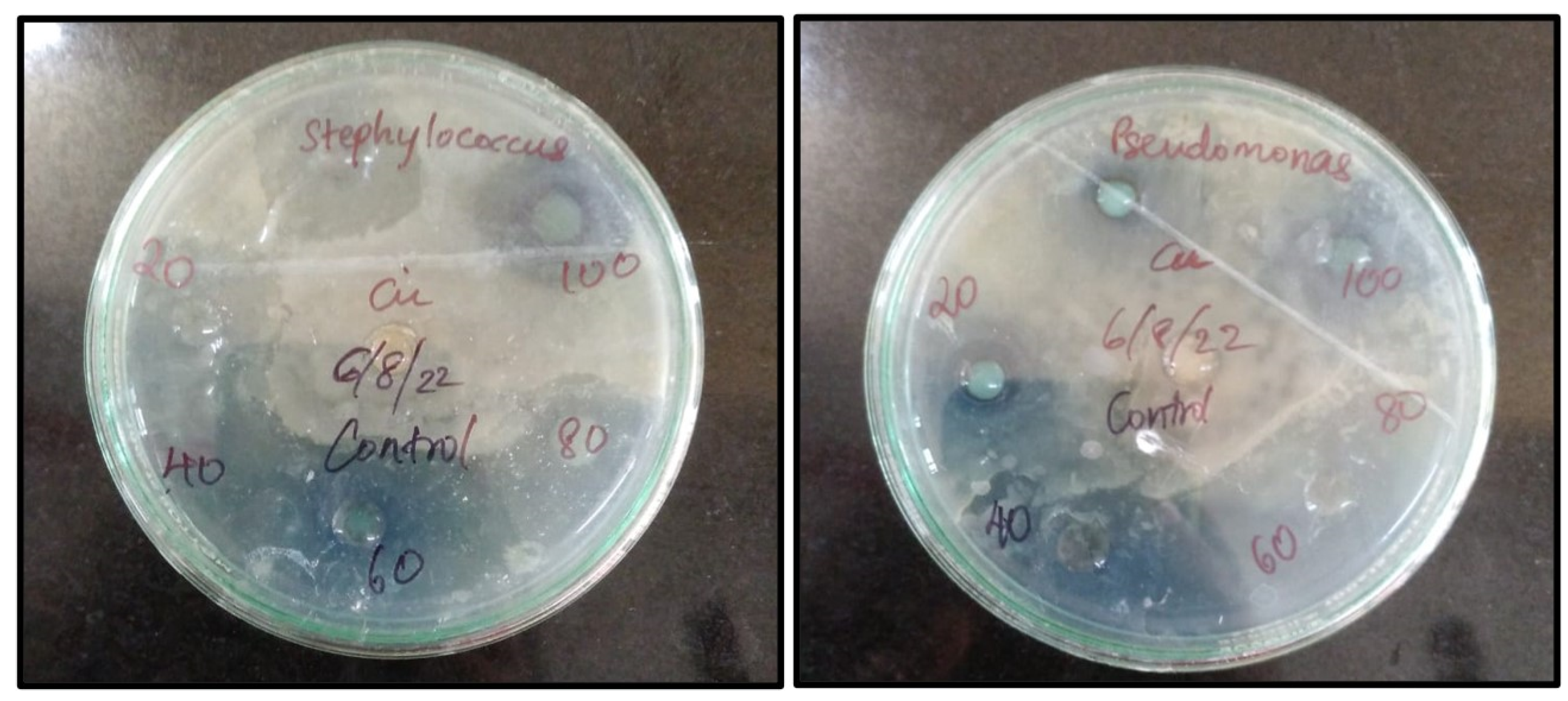

3.6. Study of Antibacterial work

Nowadays, the bactericidal effect of metal nanoparticles has received much attention. An Antibacterial element is a compound that eliminates or hinders the growth of microorganisms without causing harm to the environmental tissue. These compounds are primarily used in food industries (mainly during packaging), textile industries, pharmaceutical industries and are also used to disinfect waters. Different concentrations of Cu nanoparticles synthesized from root extract of

A. racemosus (20µg,40µg, 60µg, 80µg, 100µg.) were subjected to two bacterial pathogens,

Staphylococcus aureus being a gram +ve Bacteria and

Pseudomonas aeruginosa being a gram –ve bacteria.

Table 1 and

Figure 10 illustrate the zone of inhibition for these biosynthesized nanoparticles. The copper ions from these nanoparticles bind to the outermost membrane of these pathogens causing a bactericidal effect.[ G. Caroling

et al.,2015] When comparing Cu nanoparticles to previous studies related to silver nanoparticles, we can conclude that Cu is more reactive and thus has better bactericidal action against virus, yeast and bacteria than silver nanoparticles.[ N. Duran

et al.,2011, S. Prabhu

et al.,2012, A. Srivastava

et al.,2009, G. Grass

et al.,2011, C.E. Santo et al.,2012]This phenomenon is known as contact killing [ M. Raffi

et al.,2010, N.C. Cady

et al.,2011, A.K. Chatterjee

et al.,2012]. Recent studies have shown that natural copper nanoparticles can combat microbial contamination and are useful for many medical purposes such as wound healing and other routine applications due to its self-sanitizing property.

Figure 10.

Zone of Inhibition of Biosynthesized Copper nanoparticles.

Figure 10.

Zone of Inhibition of Biosynthesized Copper nanoparticles.

Tables

Table 1.

Inhibition zone of biosynthesized copper nanoparticles.

Table 1.

Inhibition zone of biosynthesized copper nanoparticles.

| Concentration(µg) |

Staphylococcus aureus (gram +ve)cm |

Pseudomonas aeruginosa (gram -ve)cm |

| (zone of inhibition expressed in cms) |

|---|

| 20 |

2.1 |

2 |

| 40 |

2.3 |

2.1 |

| 60 |

2.4 |

2.4 |

| 80 |

2.5 |

2.4 |

| 100 |

3 |

2.5 |

Table 2.

Phytochemical analysis and Carbohydrates test.

Table 2.

Phytochemical analysis and Carbohydrates test.

| SI. No. |

Phytochemicals |

Test |

Observation |

Results |

| 1. |

Flavonoids |

Alkaline reagent |

Intense yellow colour formation |

+ |

| 2. |

Saponins |

Foaming/froth |

Formation of froth was observed |

+ |

| 3. |

Alkaloids |

Mayer’s reagent |

Brown precipitate was observed |

+ |

| 4. |

Phenols |

Solution of FeCl3

|

Formation of black or blue colour |

+ |

| 5. |

Carbohydrates |

Molisch’s Reagent

Fehling’s A&B

Bial’s Test

Barfoed’s Reagents |

Formation of Red colour

Appearance of brownish-red or yellow precipitate of cuprous oxide

Formation of blue green product

Appearance of red precipitate |

+

+

+

+

+ |

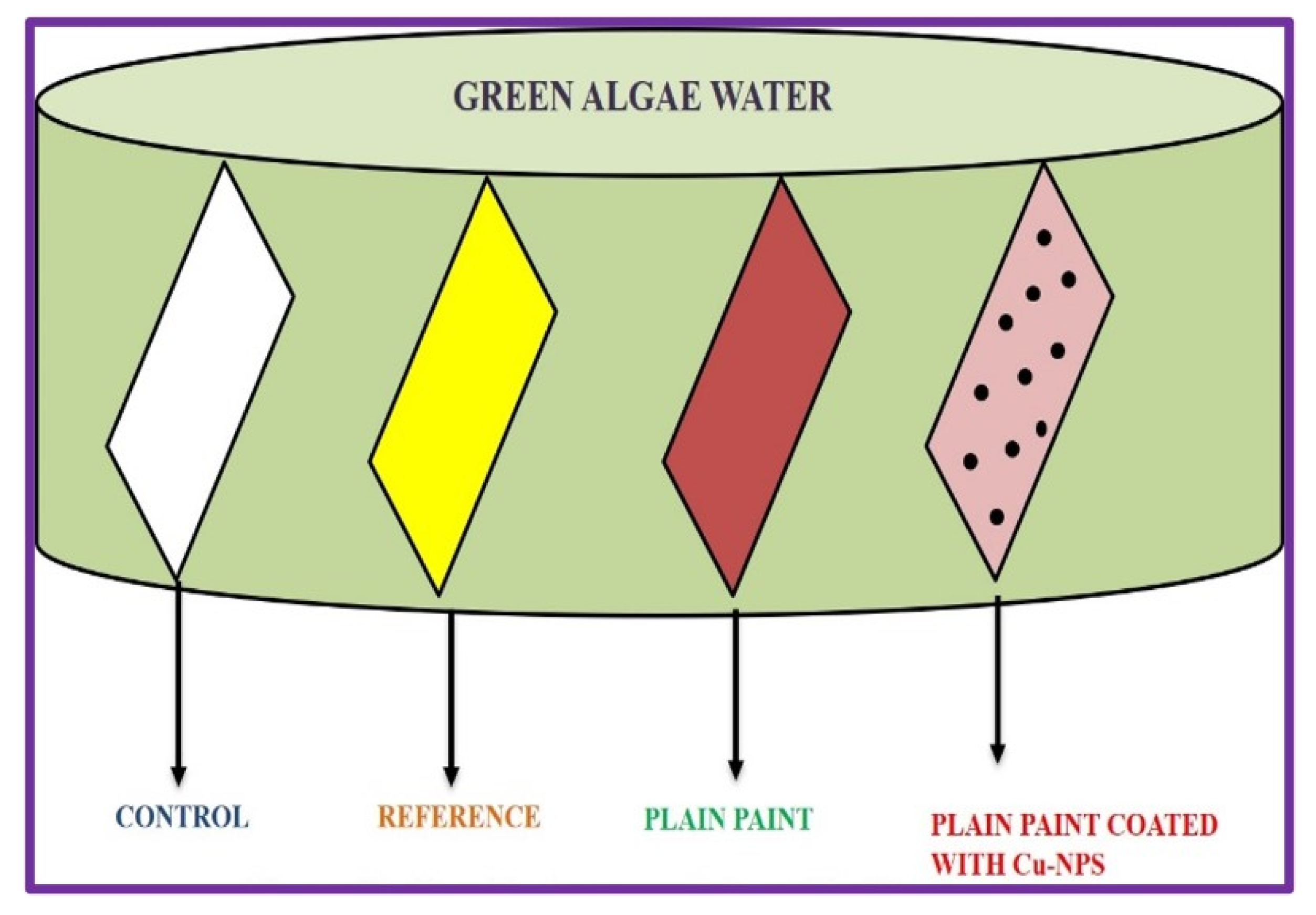

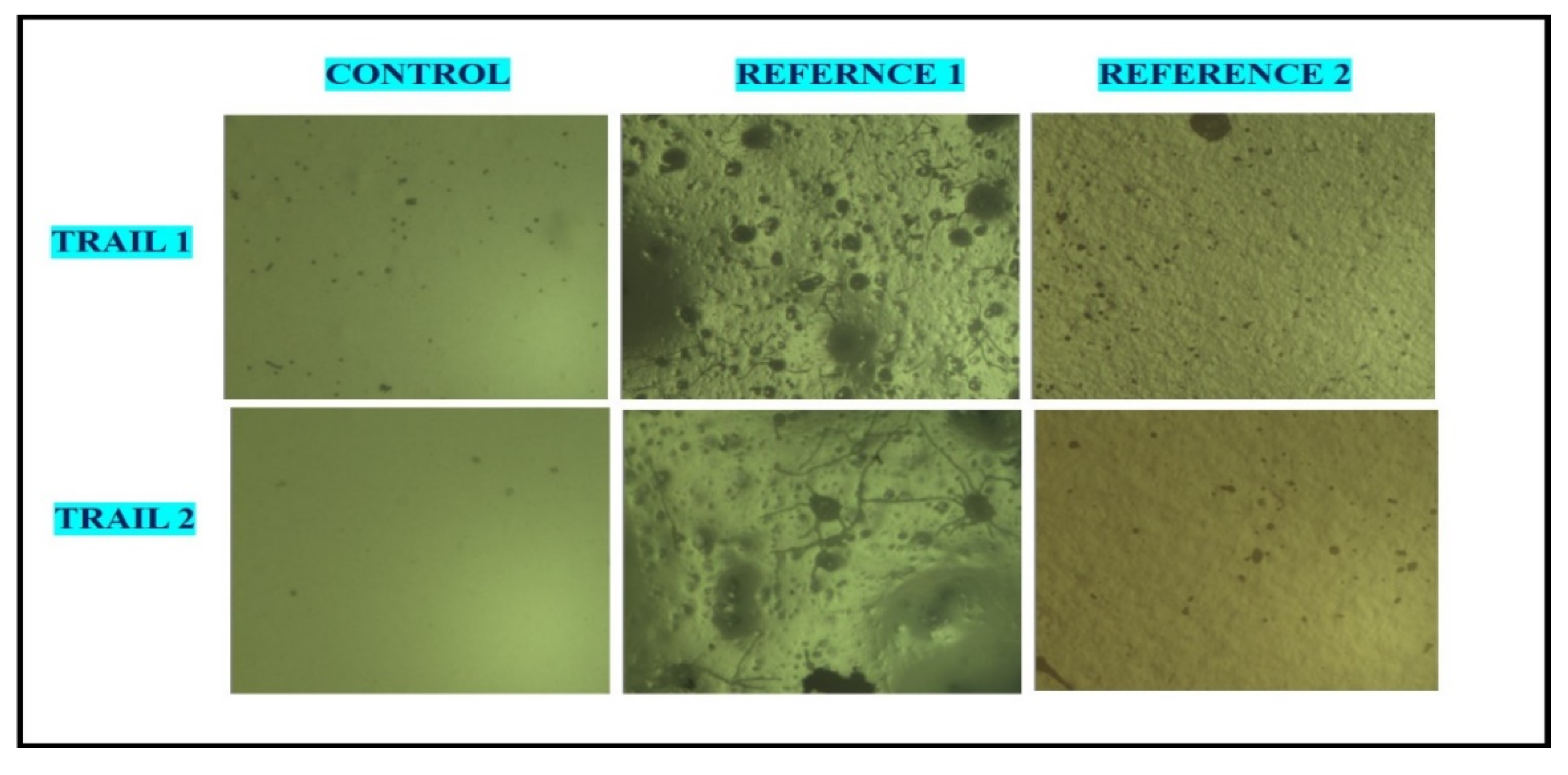

3.7. Determination of Antifouling in Copper nanoparticles

In addition to having antibacterial property, they also show excellent antifouling activity in algae water. In order to examine the biofouling activity, copper nanoparticles were doped in commercially available paints. The most widely used biocides that are commercially available in antifouling marine paints are copper oxides [ N. Cioffi

et al.,2004]. Water with intense green algae bloom was obtained from National centre for Nanoscience and nanotechnology and some bacterial strains were monitored growing in these waters. Four different glass slides were immersed in the green algae water tank. The first slide was a plain slide which acted as a control, the second slide was coated with commercially available antibacterial/biofouling paint, the third slide was coated with normal available paint and the last slide coated with biosynthesized Copper nanoparticle coated paint. The immersed slides were kept in sunlight for 15days and it was continuously being monitored. To increase the reliability and reproducibility, the experiment was repeated thrice.

Figure 13 shows the graphical representation of antifouling activity.

Figure 14 shows the inverted microscope images of control and paint coated slides. From this experiment we can conclude that the biosynthesized Cu nanoparticles have a wide range of use particularly in coating household materials, antibacterial paints, and more importantly to reduce the biofouling on ships [ Kelechi C. Anyaogu

et al.,2008].

Figure 11.

Graphical representation of Antifouling Study.

Figure 11.

Graphical representation of Antifouling Study.

Figure 12.

Phase contrast microscope images of antifouling study.

Figure 12.

Phase contrast microscope images of antifouling study.

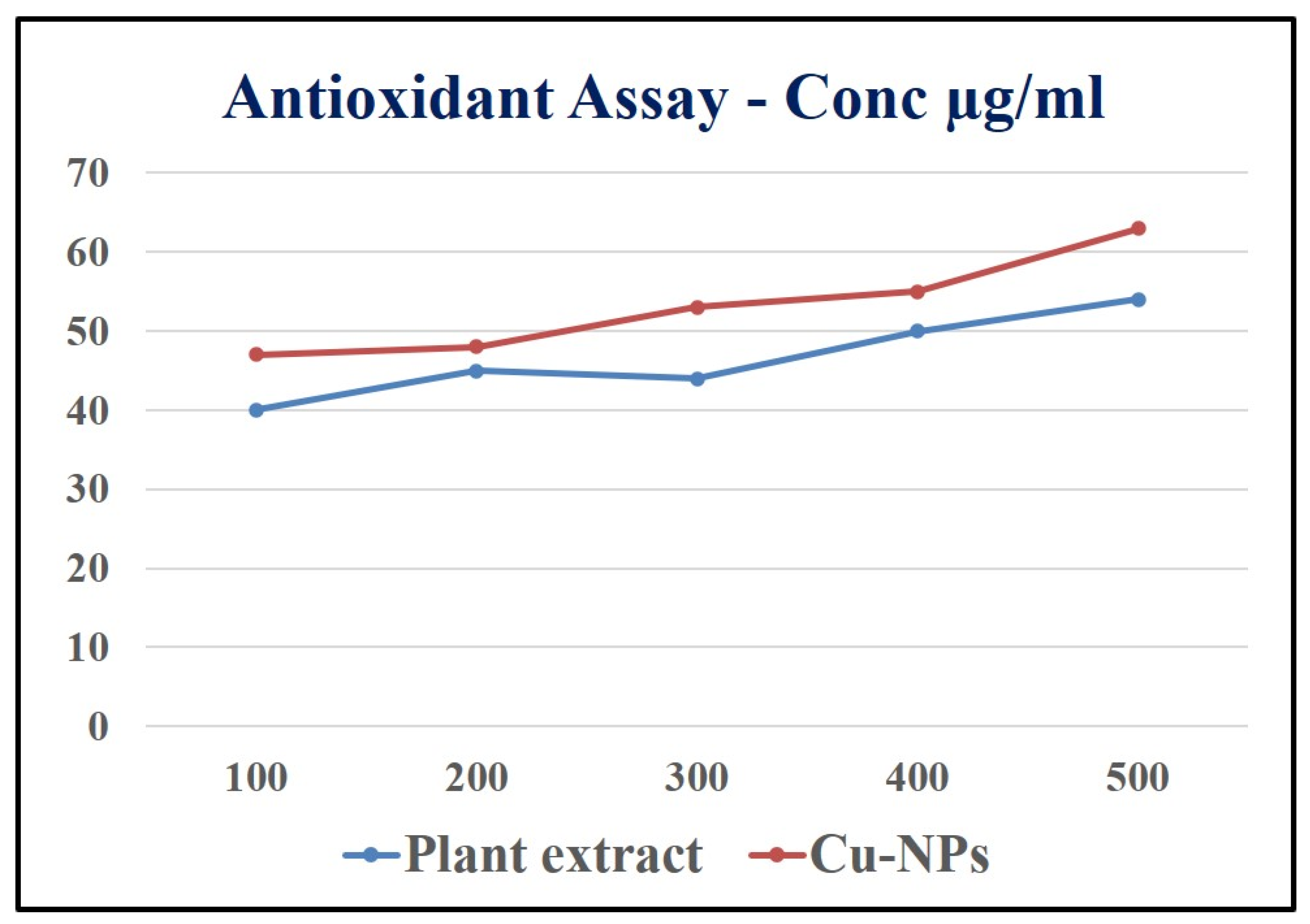

Figure 13.

Antioxidant activity of root extract and Cu-NPs.

Figure 13.

Antioxidant activity of root extract and Cu-NPs.

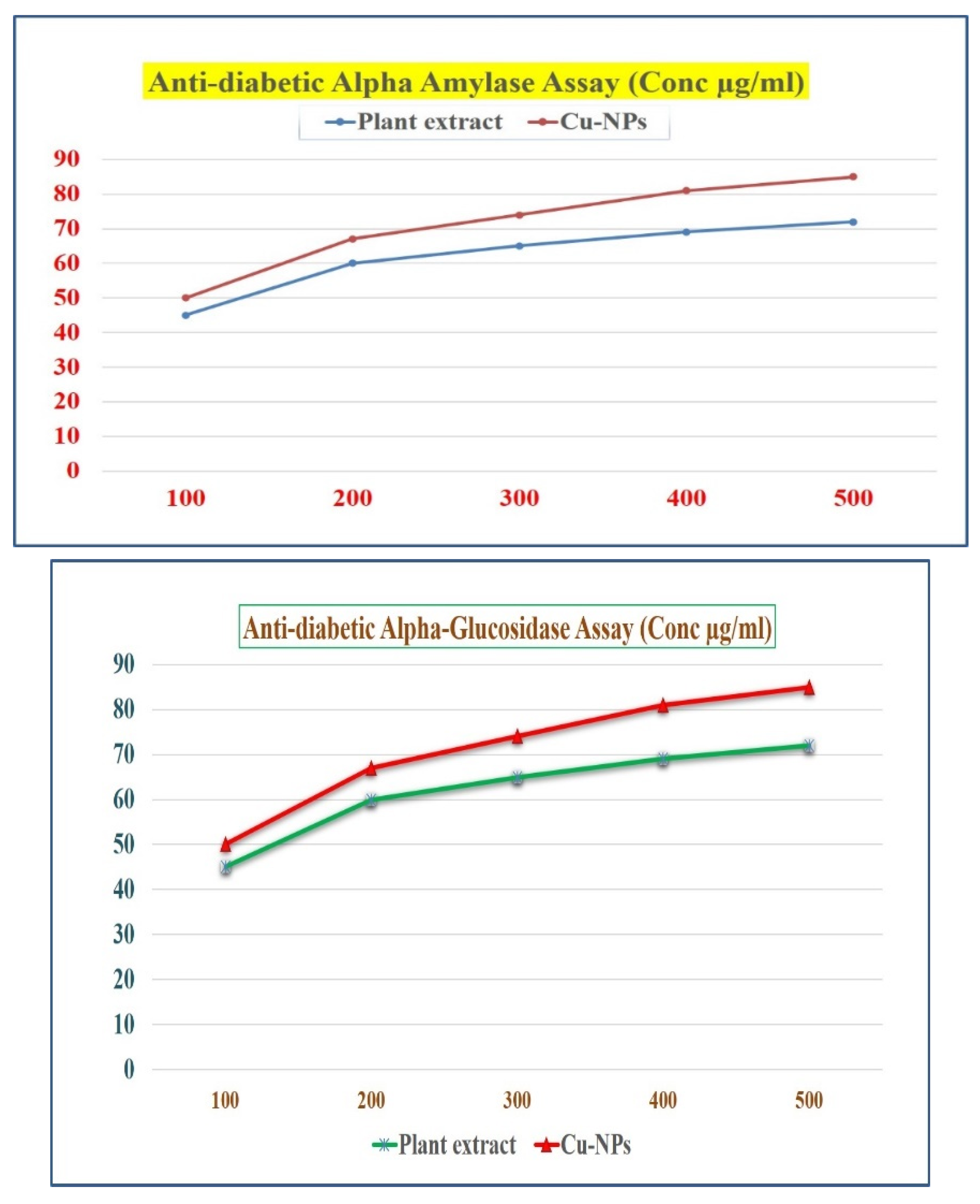

Figure 14.

Antidiabetic activity of root extract and Cu-NPs (a) Alpha amylase assay and (b) Alpha glycosidase assay.

Figure 14.

Antidiabetic activity of root extract and Cu-NPs (a) Alpha amylase assay and (b) Alpha glycosidase assay.

3.8. Antioxidant activity of Root extract and Cu-NPs

DPPH (2, 2-diphenyl-1-picrylhydrazyl) assay

Radical scavenging activity against (2, 2-diphenyl-1-picrylhydrazyl) DPPH was carried out by taking different concentrations (100, 200, 300, 400 and 500 μg/mL) of the root extract of Shatavari and in separate test tubes the biosynthesized Cu-NPs along with 2% of DPPH in methanol solution. The both samples were shacked well and endlessly, the test tubes samples were kept at 37 ◦C in dark incubation for about 30 minutes. The absorption of the sample was recorded at 517 nm against the blank sample [Subha Veeramani et al., 2020]. The scavenging activity of the sample was tested and the absorption values were calculated by using the below formula,

Scavenging activity (%) = [A control – A sample/A control] × 100

Here, the DPPH in methanol solution was used as control.

The antioxidant properties of Shatavari root extract and the biosynthesized Cu-NPs has many biomedicine benefits because, the Shatavari (

Asparagus racemosus) has an enormous number of properties such as antidiabetic, anti-ulcerogenic action, antioxidant etc [Karuna

et al., 2018]. Initially, free radicals in the outer most orbit was unpaired electron which is highly unstable and it is harmful to human body. Once free radical produced in a body it initiates the chain reaction and it may cause many disorders in our body. As shown in the

Figure 10 the root extract and Cu nanoparticles were taken in increasing concentration (100, 200, 300, 400 and500 μg/ml which brings the antioxidant properties in Shatavari root extract to overcome the many diseases such as blood pressure, Atherosclerosis, Diabetes etc. By increasing the concentration of root extract and Cu Nanoparticles, it could be identified that which concentration have higher Antioxidant activity. At 500 μg/ml concentration the root extract shows the highest DPPH free radicals. Then Cu nanoparticles also showed a significant antioxidant property. Thus, many medicinal plants help in synthesising nanoparticles and could also increase the antioxidant property when comparing to extract.

3.9. Antidiabetic activity of Root extract and Cu-NPs

3.9.1. α- Amylase inhibition assay and α -Glucosidase inhibition assay

From the existing protocol, this protocol was slightly changed [Subha Veeramani et al,. 2020]. In this study, we report that anti-diabetic property of shatavari and bio-synthesized Cu NPs were calculated by the inhibition assay. The enzymes concentration dependent on both Shatavari extract and the Cu-NPs. Due to Carbohydrates consumption is high, the enzymes activity was decreased [Guo et al., 2020, Idmhand et al., 2020, Wariyapperuma et al., 2020, Badeggi et al., 2020, and Sati et al., 2020]. The extract and Phyto fabricated Cu-NPs inhibited the maximum enzyme activity of α -Amylase and shows the maximum anti-diabetic property of 76% and 79% in the concentration of 500 μg/mL. The result obtained for α -Glucosidase inhibition is in increasing order, because of its effectiveness as a glucosidase inhibitor [Parveen et al., 2022 and Popli et al., 2018]. The maximum inhibition activity of α -Glucosidase for both root extract and Cu-NPs showed a 77 % and 81% at 500 μg/mL. The significant reason for maximum enzyme inhibition of Cu-NPs is due to the presence of phytochemicals like polyphenols, tannins, flavonoids etc present in the root extract, were already confirmed by the obtained FTIR results. Since the Phyto fabricated Cu-NPs can be used as a promising agent in various anti-diabetic drugs for the future studies due to exhibition of good antioxidant and anti-diabetic activity in the root extract. have reported that metal nanoparticles showed a notable inhibition on alpha glucosidase, because of α -Glucosidase playing a important role in reducing the glucose concentrations of postprandial. These properties of shatavari root extract and Phyto fabricated Cu-NPs makes them as promising anti-diabetic agent.

4. Conclusion

Biosynthesizing copper nanoparticles is an eco-friendly, green process as opposed to a chemical synthesis process. The UV peak at 650 nm and the XRD spectrum was used to confirm the formation and the monoclinic structure of copper nanoparticles respectively. The FTIR samples were used to recognise the significant groups of atoms present in the samples. Antibacterial activity which is performed at various concentrations shows excellent and promising results. Overall, this research opens up new opportunities for research and industry because of the ease with which copper nanoparticles can be synthesized. This can be very useful for a variety of potential applications in almost all fields in the upcoming days. At the present time, there is intense increase in examining the antifouling, antibacterial, antifungal properties and also other properties, by the use of nanomaterials. Different mechanisms have been hypothesised for these biocidal substances to kill bacteria or cells, but the biochemical process or method by which they operate on microorganisms is not yet fully understood.

Acknowledgments

We thank DST SERB NPDF for funding support. Dr Kirubanandan Shanmugam is grateful to Professor R. Ilangovan, National Centre for Nanoscience and Nanotechnology, University of Madras, Guindy Campus, India for allowed me to work as Post-Doctoral Researcher at this centre. Dr. K.Shanmugam is very much thankful to Saveetha University, Thandalam , India for selected him as Distinguished Assistant Professor (Research and Development).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

References

- Hincapie, I.; Caballero-Guzman, A.; Hiltbrunner, D.; Nowack, B. “Use of engineered nanomaterials in the construction industry with specific emphasis on paints and their flows in construction and demolition waste in Switzerland. Waste Management 2015, 43, 398–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almeida, E.; Diamantino, T.C.; de Sousa, O. Marine paints: the particular case of antifouling paints. Progress in Organic Coatings 2007, 59, 2–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agga, G.E.; Scott, H.M.; Amachawadi, R.G.; Nagaraja, T.G.; Vinasco, J.; Bai, J.; Norby, B.; Renter, D.G.; Dritz, S.S.; Nelssen, J.L.; Tokach, M.D. Effects of chlortetracycline and copper supplementation on antimicrobial resistance of fecal Pseudomonas aeruginosa from weaned pigs. Preventive Veterinary Medicine 2014, 114, 231–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ahire, J.J.; Hattingh, M.; Neveling, D.P.; Dicks, L.M.T. Copper-containing anti-biofilm nanofiber scaffolds as a wound dressing material. 2016, 11, e0152755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alizadeh, S.; Seyedalipour, B.; Shafieyan, S.; Kheime, A.; Mohammadi, P.; Aghdami, N. Copper nanoparticles promote rapid wound healing in acute full thickness defect via acceleration of skin cell migration, proliferation, and neovascularization. Biochemical and Biophysical Research Communications 2019, 517, 684–690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chawla, A.; Chawla, P.; Mangalesh; Roy, R.C. Asparagus racemosus (Wild): Biological Activities & its Active Principles. Indo-Global Journal of Pharmaceutical Sciences 2011, 1. Issue 2: bactericidal effect of silver nanoparticles. Nanotechnology 16:2346–53. [Google Scholar]

- Mishra, A.; Mishra, V.K.; Dwivedi, K.N.D. Uv-Vis Spectroscopic Study on Phytoconstituents of Asparagus racemosus Willd Root Tuber. 2015, 4, 1538–1547. [Google Scholar]

- Sharma, A.; Sharma, V. A Brief review of medicinal properties of Asparagus racemosus (Shatavari)International Journal of Pure & Applied Bioscience ISSN: 2320 – 7051 Int. J. Pure App. Bio science 2013, 1, 48–52. [Google Scholar]

- EAthanassiou, K.; Grass, R.N.; Stark, W.J. Large-scale production of carbon-coated copper nanoparticles for sensor applications. Nanotechnology 2006, 17, 1668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borkow, G.; Gabbay, J.; Dardik, R.; Eidelman, A.I.; Lavie, Y.; Grunfeld, Y.; Ikher, S.; Huszar, M.; Zatcoff, R.C.; Marikovsky, M. Molecular mechanisms of enhanced wound healing by copper oxide-impregnated dressings. Wound Repair Regen 2010, 18, 266–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borkow, G.; Zatcoff, R.C.; Gabbay, J. Reducing the risk of skin pathologies in diabetics by using copper impregnated socks. Med Hypotheses 2009, 73, 883–886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cady, N.C.; Behnke, J.L.; Strickland, A.D. Copper-based nanostructured coatings on natural cellulose: nanocomposites exhibiting rapid and efficient inhibition of a multidrug resistant wound pathogen, A. Baumannii, and mammalian cell biocompatibility in vitro. Advance Functional Mater 2011, 21, 2506–2514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caroling, G.; Vinodhini, E.; Ranjitham, A.M.; Shanthi, P. Biosynthesis of Copper Nanoparticles Using Aqueous Phyllanthus Embilica (Gooseberry) Extract- Characterisation and Study of Antimicrobial Effects. ( 2015. [CrossRef]

- Chatterjee, A.K.; Sarkar, R.K.; Chattopadhyay, A.P.; Aich, P.; Chakraborty, R.; Basu, T. A simple robust method for synthesis of metallic copper nanoparticles of high antibacterial potency against E. coli. Nanotechnology 2012, 23, 85–103. [Google Scholar]

- Chopra, R.N.; Chopra, I. Indigenous drugs of India; Calcutta Academic Publishers, 1994; Volume 496. [Google Scholar]

- Cioffi, N.; Torsi, L.; Ditaranto, N.; Tantillo, G.; Ghibelli, L.; Sabbatini, L. Copper nanoparticle/ polymer composites with antifungal and bacteriostatic properties. Chem Mater 2005, 17, 5255–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Subha, V.; Kirubanandan, S.; Renganathan, S. Green Synthesis of Copper Nanoparticles Using Methanol Extract of Passiflora foetida and Its Drug Delivery Applications Centre for Biotechnology, Alagappa College of Technology, Anna University, Chennai, India. International Journal of Green Chemistry 2017, 3. [Google Scholar]

- Duran, N.; Marcato, P.D.; Duran, M.; Yadav, A.; Gade, A.; Rai, M. Mechanistic aspects in the biogenic synthesis of extracellular metal nanoparticles by peptides, bacteria, fungi and plants. Appl Microbiol Biotechnology 2011, 90, 1609–1624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gawande, M.B.; Branco, P.S.; Parghi, K.; Shrikhande, J.J.; Pandey, R.K.; Ghumman, C.A.A.; Bundaleski, N.; Teodoro, O.; Jayaram, R.V. Synthesis and Characterization of Versatile MgO-ZrO2 Mixed Metal Oxide Nanoparticles and Their Applications. Catal. Sci. Technol. 2011, 1, 1653–1664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grass, G.; Rensing, C. Solioz M Metallic copper as an antimicrobial surface. Appl Environmental Microbiology 2011, 77, 1541–1547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mishra, J.N.; Verma, N.K. Asparagus racemosus: chemical constituents and pharmacological activities-a review. Eur. J. Biomed. Pharm. Sci. 2017, 4, 207–213. [Google Scholar]

- Veeramani Subha, Eswari Thulasimuthu, Rajangam Ilangovan, Bactericidal action of copper nanoparticles synthesized from methanolic root extract of Asparagus racemosus, (2022)National Centre for Nanoscience and Nanotechnology, University of Madras, Guindy Campus, Chennai 25, India. [CrossRef]

- Kamat, J.P.; Boloor, K.K.; Devasagayam, T.P.; Venkatachalam, S. Antioxidant Properties of Asparagus racemosus against Damage Induced by Gamma-Radiation in Rat Liver Mitochondria. J. Ethnopharmacology 2000, 71, 425–435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kantam, M.L.; Jaya, V.S.; Lakshmi, M.J.; Reddy, B.R.; Choudary, B.; Bhargava, S. Alumina supported copper nanoparticles for aziridination and cyclopropanation reactions. Catalysis Communications 2007, 8, 1963–1968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kornblatt, A.P.; Nicoletti, V.G.; Travaglia, A. The neglected role of copper ions in wound healing. J. Inorganic Biochemistry. 2016, 161, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laurent, S.; Forge, D.; Port, M.; Roch, A.; Robic, C.; Elst, L.V.; Muller, R.N. Magnetic Iron Oxide Nanoparticles: Synthesis, Stabilization, Vectorization, Physicochemical Characterizations, and Biological Applications. Chem Rev. 2008, 108, 2064–2110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C.H.; Peterson, G.P. Experimental investigation of temperature and volume fraction variations on the effective thermal conductivity of nanoparticle suspensions(nanofluids). Journal of Applied Physics 2006, 99, 084314–1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohammad W. Amer and Akl M. Awwad, Department of Chemistry, University of Jordan, Amman, Jordan, Department of Nanotechnology, Royal Scientific Society, Amman, Jordan (2020). ISSN 2410-9649.

- Mohanta, B.; Chakraborty, A.; Sudarshan, M.; Dutta, R.K.; Baruah, M. Elemental profile in some common medicinal plants of India. Its correlation with traditional therapeutic usage. Journal of Rad Analytical Nuclear Chemistry 2003, 258, 175–179. [Google Scholar]

- Usman, M.S.; Ibrahim, N.A.; Shameli, K.; Zainuddin, N.; Yunus, W.M.Z.W. Copper Nanoparticles Mediated by Chitosan: Synthesis and Characterization via Chemical Methods. Molecules 2012, 17, 14928–14936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Narayanan, R.; El-Sayed, M.A. Effect of Nano catalysis in Colloidal Solution on the Tetrahedral and Cubic Nanoparticle SHAPE: Electron-Transfer Reaction Catalysed by Platinum Nanoparticles. J. Phys. Chem.B 2004, 108, 5726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pooja Shaha, Anurag Bellankimath Department of Biotechnology, Basaveshwar Engineering College, Bagalkot- 587102, Karnataka, India, ejbps (2017), Volume 4, Issue 6, 207-213.

- Prabhu, S.; Poulose, E. Silver nanoparticles: mechanism of antimicrobial action, synthesis, medical applications, and toxicity effects. Intern Nano Lett 2012, 2, 32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raffi, M.; Mehrwan, S.; Bhatti, T.M. Investigations into the antibacterial behavior of copper nanoparticles against Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Ann Microbiol 2010, 60, 75–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rajeshkumar, S.; Kannan, C.; Annadurai, G. Green synthesis of silver nanoparticles using marine brown algae Turbinaria conoides and its antibacterial activity. J. Pharm. Bio. Sci 2012, 3, 502–510. [Google Scholar]

- Ramyadevi, J.; Jeyasubramanian, K.; Marikani, A.; Rajakumar, G.; Rahuman, A.A. Mater. Lett. 2012, 71, 114.

- Santo, C.E.; Quaranta, D.; Grass, G. Antimicrobial metallic copper surfaces kill Staphylococcus haemolyticus via membrane damage. Microbiology open 2012, 1, 46–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sapna Thakur, Sushma Sharma, Shweta Thakur and Radheshyam Rai., (2018). 2018. [CrossRef]

- Scaletti, R.W.; Harmon, R.J. Effect of dietary copper source on response to coliform mastitis in dairy cows. Journal of dairy science 2012, 95, 654–662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sharma, S.; Sharma, H. Oligofuroand spiro-stanosides of Asparagus adscendens Phytochemistry (1984), 23 (3): 645-648. [CrossRef]

- S. Sharma, R. Chand, and O. Sati, Steroidal saponins of Asparagus adscendens. Phytochemistry (1982), 21 (8): 2075-2078. [CrossRef]

- Singh, A.K.; Talat, M.; Singh, D.; Srivastava, O. Biosynthesis of gold and silver nanoparticles by natural precursor clove and their functionalization with amine group. Journal of Nanoparticle Research 2010, 12, 1667–1675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Readman, J. Development, occurrence and regulation of antifouling paint biocides: historical review and future trends. Antifouling Paint Biocides 2006, 5, 1–15. [Google Scholar]

- Yebra, D.M.; Kiil, S.; Dam-Johansen, K. Antifouling technology-past, present and future steps towards efficient and environmentally friendly antifouling coatings. Progress in Organic Coatings 2004, 50, 75–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gipperth, L. The legal design of the international and European Union ban on tributyltin antifouling paint: direct and indirect effects. Journal of Environmental Management 2009, 90, S86–S95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brown, N.L.; Rouch, D.A.; Lee, B.T.O. Copper resistance determinants in bacteria. Plasmid 1992, 27, 41–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Srivastava, A. Antiviral activity of copper complexes of isoniazid against RNA tumor viruses. Resonance 2009, 14, 754–760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tandon, M.; Shukla, Y.N.; Thakur, R.S. Steroid glycosides from Asparagus adscendens, Phytochemistry, (1990) 29 (9): 2957-2959. [CrossRef]

- Tiwari, M.; Narayanan, K.; Thakar, M.B.; Jagani, H.V.; Rao, J.V. Biosynthesis and wound healing activity of copper nanoparticles. IET Nanobiotechnology 2014, 8, 230–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, Q.; Zhao, Y.; Xu, J.Z.; Zhu, J.-J. Preparation of functionalized copper nanoparticles and fabrication of a glucose sensor. Sensors and Actuators B 2006, 114, 379–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pocino, M.; Baute, L.; Malavi, I. Influence of the oral administration of excess copper on the immune response. Fundamental and applied toxicology: official journal of the society of toxicology 1991, 16, 249–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yatoo, M.I.; Saxena, A.; Deepa, P.M.; Habeab, B.P.; Devi, S.; Jatav, R.S.; Dimri, U. Role of Trace elements in animals: a review. Veterinary World 2013, 6, 963–967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodriguez, J.A.; Liu, P.; Hrbek, J.; Evans, J.; Perez, M. Water Gas Shift Reaction on Cu and Au Nanoparticles Supported on CeO2(111) and ZnO(0001¯): Intrinsic Activity and Importance of Support Interactions Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. ( 2007), 119. [CrossRef]

- Sudhakar, S.; Joshi, L.K.; Sehgal, A. Assessment of antioxidant and anti-lipid peroxidation capability of Guduchi (Tinospora cordifolia). Research Journal of Pharmaceutical Biological and Chemical Sciences 2015, 6, 458–463. [Google Scholar]

- Karuna, D.S.; Dey, P.; Das, S.; Kundu, A.; Bhakta, T. In vitro antioxidant activities of root extract of Asparagus racemosus Linn. Journal of Traditional and Complementary Medicine 2018, 8, 60–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Subha Veeramani, P. Arya. Narayanan. Nigella sativa flavonoids surface coated gold NPs (Au-NPs) enhancing antioxidant and anti-diabetic activity. Process Biochemistry, (2020). [CrossRef]

- Anyaogu, K.C.; Fedorov, A.V.; Neckers, D.C. Synthesis Characterization, and Antifouling Potential of Functionalized Copper Nanoparticles. American Chemical Society (2008). [CrossRef]

- Cioffi, N.; Torsi, L.; Ditaranto, N.; Sabbatini, L.; Zambonin, P.G.; Tantillo, G.; Ghibelli, L.; D’Alessio, M.; Bleve-Zacheo, T.; Traversa, E. Antifungal activity of polymer-based copper nanocomposite coatings. Appl. Phys. Lett 2004, 85, 2417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, Y.; Jiang, N.; Zhang, L.; Yin, M. Green synthesis of gold NPsfrom Fritillaria cirrhosa and its anti-diabetic activity on streptozotocin induced rats, Arab. J. Chem. 2020, 13, 5096–5106. [Google Scholar]

- Idmhand, E.; Msanda, F.; Cheriti, K. Ethnopharmacological review of medicinal plants used to manage diabetes in morocco. Clin. Phytosci. 2020, 6, 1–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wariyapperuma, W.A.N.M.; Kannangara, S.; Wijayasinghe, Y.S.; Subramanium, S.; Jayawardena, B. In-vitro anti-diabetic effects and phytochemical profiling of novel varieties of cinnamomum zeylanicum (L. ) extract. Peer J. 2020, 8, e10070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Badeggi, U.M.; Ismail, E.; Adeloye, A.O.; Botha, S.; Badmus, J.A.; Marnewick, J.L.; Cupido, C.N.; Hussein, A.A. Green synthesis of gold NPs capped with procyanidins from cerrcosidea sericea as potential anti-diabetic and antioxidant agent. Biomolecules 2020, 10, 452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sati, S.C.; Kour, G.; Bartwal, A.S.; Sati, M.D. Biosynthesis of metal nanoparticles from leaves of ficus palmata and evaluation of their anti-inflammatory and anti-diabetic activities. Biochemistry 2020, 59, 3019–3025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parveen, A.; Farooq, M.A.; Kyunn, W.W. A new oleanane type saponin from the aerial parts of Nigella sativa with antioxidant and antidiabetic potential. Molecules 2020, 25, 2171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Popli, D.; Anil, V.; Subramanyam, A.B.; Namratha, N.M.N.; Ranjitha, V.R.; Rao, S.N.; Rai, R.V.; Govindappa, M. Cladosporium species-mediated synthesis of silver NPs possessing in vitro antioxidant, anti-diabetic and anti-Alzheimer activity, Artif. Cells Nanomed. Biotechnol. 2018, 46, 676–683. [Google Scholar]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).