1. Introduction

Areca nut (AN), the drupe fruit of the Areca palm (

Areca catechu), is chewed by an estimated 600 million people worldwide [

1], including the underserved Chamorro, Yapese, Palauan, Carolinian, and Chuukese ethnic minorities in Guam and Saipan of the Mariana islands in the western Pacific [

2]. During the years 2011 to 2015, approximately 11% of Guam’s population reported chewing on a regular basis [

3], whereas the corresponding prevalence in Saipan was estimated at 24% in 2009 [

4]. The majority of chewers in these islands prepare their AN wrapped in a pepper plant leaf (

Piper betle) with tobacco, slaked lime (calcium hydroxide), and sometimes other spices [

2] in what is referred to as a betel quid (BQ). According to the typology developed by Paulino et al. [

2], these individuals are classified as Class 2 chewers. By comparison, those who chew AN alone (with the occasional addition of slaked lime) are referred to as Class 1 chewers.

In 2004, compelling evidence suggested strong associations between AN chewing and an increased risk for developing oral cancer (particularly oral squamous cell carcinoma), leading to the classification of AN chewing both with and without tobacco as carcinogenic to humans by the International Agency for Research on Cancer [

5]. A subsequent meta-analysis further confirmed this association [

6]. Survival at 5 years among oral cancer cases as low as 20% have been reported in some countries in the western Pacific region, which is in stark contrast to the average worldwide 5-year survival of over 50% [

7].

Despite the global prominence of AN and BQ (ANBQ) and the devastating health burdens associated with its use, ANBQ remains an understudied research topic, and an unappreciated global public health issue [

8]. In addition, there is currently no established framework for ANBQ control, and evidence-based practices regarding prevention and cessation of ANBQ chewing are in nascent stages of development [

9].

One particularly neglected area of ANBQ research is randomized cessation intervention trials for ANBQ chewers who are trying to quit [

10]. Recently, researchers have identified this gap in the literature and have begun to address this issue. Lee et al. [

11], for example, conducted a qualitative study of ANBQ cessation among oral cancer patients in Taiwan. Tami-Maury et al. [

12] explored qualitatively the potential for ANBQ cessation strategies in dental settings in Taiwan. Papke et al. [

13] hypothesized that ANBQ cessation programs ultimately should include both behavioral and pharmaceutical components. Hung et al. [

14] recently conducted an eight-week randomized trial of anti-depressant medications for ANBQ cessation in Taiwan. Although their sample size was small (n<40 for treatment groups), the results were promising. Finally, Paulino et al. [

15] described our superiority randomized controlled trial to test the efficacy of an intensive behavioral ANBQ cessation program on the western Pacific islands of Guam and Saipan, aptly named The Betel Nut Intervention Trial (BENIT). BENIT is a registered clinical trial under the U.S. National Library of Medicine of the National Institutes of Health. This manuscript presents primary data consisting of self-reported cessation outcomes at the 22-day follow-up assessment.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design

The study design of BENIT was described in detail previously [

15]. In brief, BENIT is a two-arm superiority randomized controlled trial (registered at clinicaltrials.gov, trial number NCT02942745). All data were collected in Guam (University of Guam) or Saipan (Community clinic). Recruitment commenced in August 2016 and ended in January 2020. Data was collected between August 2016 and February 2020. Participants randomized to the intervention condition attended five in-person intensive behavioral intervention sessions administered over approximately 22 days. The intervention, which was developed using a smoking cessation intervention as an initial framework [

16], was adapted and improved upon using findings from both survey [

3,

17,

18] and pilot intervention research [

19] as part of a cumulative ANBQ research program. In addition to receiving the intensive intervention, participants also received a booklet containing information about the negative health effects of chewing ANBQ and advice for how to quit chewing ANBQ. Participants randomized to the control condition received only the booklet. This study received IRB approval from the University of Guam (#16-04). The University of Guam IRB monitored the study for both study locations (Guam and Saipan) because Saipan does not have an IRB suitable for monitoring a randomized trial. All participants provided written informed consent and were compensated for their time.

2.2. Target Population, Inclusion/Exclusion Criteria, and Recruitment

BENIT was conducted with Class 2 chewers residing in Guam and Saipan. This inclusion criterion was due to: 1) previous research that revealed a preponderance of Class 2 chewers in these locations [

2], and 2) the fact that Class 2 chewers generally have a bigger health burden than Class 1 chewers, as the ANBQ with added slaked lime and tobacco is more addictive and more carcinogenic than AN alone [

20].

Inclusion criteria were: 1) self-identified chewer of ANBQ with tobacco for at least one year with a minimum thrice weekly frequency, 2) at least 18 years of age, 3) willingness to attempt to quit chewing ANBQ during the intervention, 4) willingness to participate in five, hour-long intervention sessions to take place over approximately 22 days, and 5) English literacy. Pregnant women were excluded from participating.

Recruitment was conducted using a variety of methods. Some participants were identified from previous ANBQ-related studies conducted under the National Cancer Institute-sponsored University of Guam/University of Hawaii Cancer Center Partnership to Advance Cancer Health Equity, while others were recruited through local community activities, health coalitions and associations, dental clinics, community health centers, village mayoral offices, radio announcements and interviews, religious organizations, on-campus university events, and print and social media advertising.

2.3. Sample Size and Early Termination Plan

The target sample size for BENIT was 324, which was based on a difference of 13 percentage points between intervention and control for ANBQ chewing cessation prevalence at 22 days with α=0·05 (2-sided) and β=0.20. However, an early termination plan was developed to accommodate for the possibility of stronger-than-expected intervention effects. The specific plan employed the O’Brien-Fleming procedure for interim analysis to maintain the nominal type I error probability of 0.05. This procedure has been described previously [

15]. BENIT employed a five-stage model for early termination that allowed for significance testing at pre-determined sample sizes. The first opportunity to test for significance (i.e., Stage 1) required 30 participants per study arm. To terminate the study at Stage 1, an absolute Z-score value of 4·5617 or greater was needed, with a corresponding p-value of 0·000005 or less. The Stage 2 analysis required 59 participants per study arm and a Z-score of 3·22564 or greater, with a corresponding p-value of 0·0012 or less for early termination. BENIT outcomes failed to reach these thresholds at Stages 1 and 2. The current article presents the findings at Stage 3, which required 88 participants per study arm. The current analyses pertain to the first 176 participants to complete 22-day follow-up assessments.

2.4. Randomization

BENIT participants were randomized to each treatment condition within each island [

15]. Randomization schedules were stratified by location (Guam and Saipan) and used blocked randomization [

21], with random block sizes to avoid a large imbalance in size between the study groups during any particular timeframe. Separate randomization schedules were created for individuals and for groups, in order to balance the randomization group size variable between intervention and control conditions. Condition assignments based on the randomization schedules were placed in opaque envelopes that were opened at the time of enrollment. The Biostatistics Core of the University of Guam/University of Hawaii Cancer Center Partnership designed the random allocation procedures. An independent group of research staff opened the envelopes at enrollment and informed participants of their random assignment to intervention or control. The Biostatistics Core personnel were blinded to the condition assignment as groups were labeled A and B for purposes of data analyses.

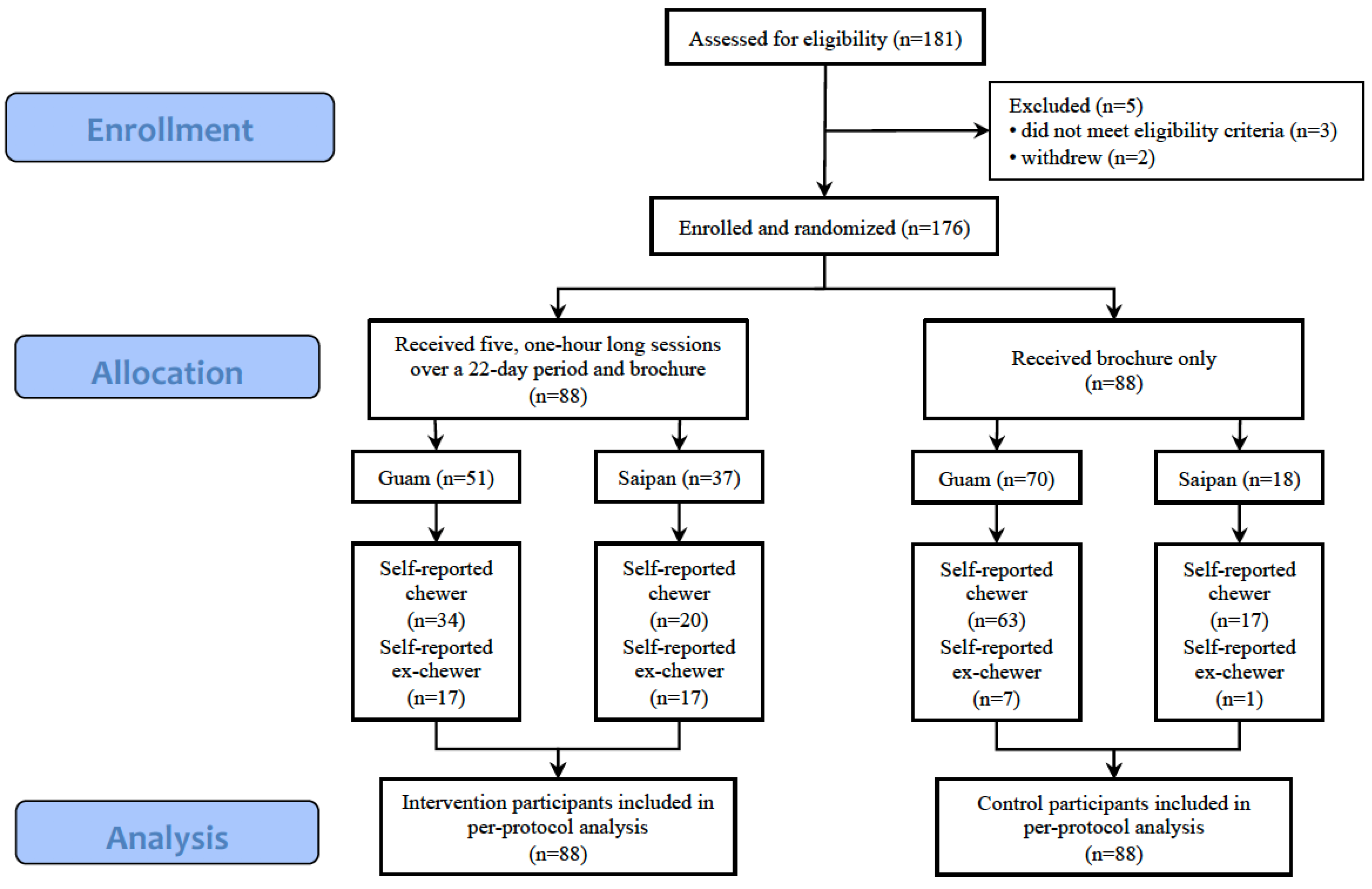

Figure 1 displays the CONSORT diagram for participants included in the current analyses.

2.5. Control Condition Procedures

Participants in the control condition received a single booklet created specifically for BENIT and was designed to encourage and facilitate ANBQ cessation. The booklet, entitled “Quitting Betel Nut,” included information about the health risks associated with ANBQ chewing, as well as advice and strategies for quitting and maintaining ANBQ abstinence. Participants assigned to the control condition met with study staff three times: baseline, 22-day follow-up, and six-month follow-up. At baseline, participants were provided with the ANBQ cessation booklet, completed a baseline survey assessment and provided a saliva sample. Participants also completed survey assessments and provided saliva samples at the 22-day and six-month follow-up sessions. Control condition participants received compensation for their time and specimen donation.

2.6. Intervention Condition Procedures

The BENIT intervention followed the general framework of intensive cognitive-behavioral therapy [

22], and was influenced by an evidence-based smoking cessation program [

16]. The intervention covered topics such as the negative health effects of ANBQ chewing, self-monitoring, triggers for chewing behaviors, substituting alternatives to chewing ANBQ, social support, and relapse prevention.

The intervention was comprised of five in-person sessions over a 22-day period. The BENIT program’s structure was such that participants were expected to attempt to quit chewing ANBQ at Session 3 (Day 15). Thus, Sessions 1 and 2 were intended to prepare participants for a quit attempt, whereas Sessions 3, 4, and 5 focused on relapse prevention. Saliva samples and survey assessments were collected at baseline (Session 1), at Session 5 (Day 22), and at 6-month follow-up (see

Table 1). Intervention condition participants received the same compensation as control condition participants.

2.7. Baseline Assessments

Baseline survey assessments included questions on demographics, current chewing behavior, chewing history, ANBQ dependence measured by the Betel Quid Dependence Scale (BQDS) [

17,

23], and other variables. The BQDS is a validated 16-item scale that measures psychological and behavioral aspects of BQ dependence. BQDS scores range from zero to 16, with 16 representing the highest possible level of dependence. Baseline survey items were identical for participants in both study arms.

2.8. Follow-Up Assessments

The first follow-up assessment was administered at the final intervention session (Session 5). This assessment was scheduled for approximately 22 days after the first intervention session. Participants at this assessment provided data regarding their experience with the BENIT program, and their chewing and quitting behaviors during the program. This follow-up assessment was identical for both intervention and control condition participants, except that control condition participants were not asked about the intervention program.

The current analyses employed an outcome measure for ANBQ that was a composite of two survey items. The first survey item read: “Which of the following do you consider yourself to be right now?” Response options were “Betel quid chewer” and “Ex-betel quid chewer.” The second survey item read: “Are you trying to quit chewing right now?” Response options were: “I already quit chewing,” “Yes, chewing but trying to quit,” and “No, chewing but not trying to quit.” For the current analyses, participants were coded as ex-chewers (quitters) if they responded “Ex-betel quid chewer” to the first survey item and “I already quit chewing” to the second survey item. We employed this composite variable to cross-verify self-reported cessation using two items with disparate wordings and response options. If the item responses provided a mixed (contradictory) response, the participant was categorized as a chewer. This composite outcome variable was employed for both intervention and control participants.

2.9. Statistical Analysis

Participant characteristics were compared between randomization groups. Proportional hazards regression model of the time until cessation was fit using randomization group as the independent variable, with and without adjustment for factors found to be out of balance between groups. The Wald test using a robust variance estimator accounting for the clustered (i.e., group) structure of the randomization was the test of the hypothesis.

3. Results

3.1. Baseline Characteristics

Demographic and ANBQ chewing history characteristics are presented in

Table 2 for the 176 participants included in the analyses. Participants were generally young, with a mean age of 28·5 years (SD 11·2), and 38·6% (n=68) were female. The sample was comprised entirely of Pacific Islanders with representation from several Pacific Islander ethnicities including Carolinian, Chamorro, Chuukese, Palauan, Pohnpeian, and Yapese. The majority of participants resided in Guam. More than half of all participants graduated from high school, and roughly one-third had at least some college education. Participants chewed a mean of 10·3 times (SD 12·7) per day and had a mean BQDS score of 8·7 (SD 3·9).

The following variables were compared between randomization groups: (a) age, (b) sex, (c) race/nationality, (d) study site, (e) participant group size, (f) number of ANBQ chews per day, (g) BQDS score, and (h) education level. The results revealed several substantial differences in baseline characteristics between the intervention and control conditions. Intervention condition participants were less likely to be female compared to control condition participants (30.7% versus 46.6%). Intervention condition participants also tended to be younger than control condition participants (mean years of 26.3 and 30.6 years, respectively), and participants in Guam were more likely to be randomized to the control condition as compared to participants in Saipan (see

Table 2).

3.2. Cessation Outcomes

The current analyses included 88 participants in the intervention group and 88 participants in the control group. All participants included in these analyses provided outcome data at the 22-day follow-up. Although we aimed to schedule the initial follow-up assessments exactly 22 days following baseline, scheduling and logistical issues required that 22 days be an approximate timeframe for the follow-up assessments. The results indicated that 34 out of 88 (38.6%) participants in the intervention condition had self-reported ANBQ cessation (i.e., ex-chewers, according to the 22-day survey assessment), whereas 8 of 88 (9.1%) control condition participants self-reported cessation.

The proportional hazards regression model revealed a significant effect for treatment group, with a Wald Chi-square test using a robust variance estimator (df = 1) = 7.6159, p = 0.0058. The Hazard Ratio for ANBQ chewing comparing the two randomization groups was 0.287 (95% CI: 0.123 – 0.592), indicating that the BENIT intervention led to a 71% reduction in ANBQ chewing as compared to the control condition. The Chi-square value of 7.6159 met the criteria for significance for early stopping at Stage 3 that Chi-square (df = 1) > 6.9365, or equivalently that |Z| > 2.63372. (A Chi-square statistic with 1 degree of freedom is equivalent to a squared Z statistic.) Thus, the null hypothesis that the cessation percentages for the intervention and control conditions are equal was rejected and the BENIT ceased recruitment after the Stage 3 assessment.

An additional analysis of the treatment effect adjusted for the participant characteristics that were not in balance between treatment groups: sex (male or female), age (continuous), and location (Saipan or Guam). This analysis revealed a significant effect for study condition, robust Wald Chi-square (df = 1) = 7.2017, p = 0.0073. The Hazard Ratio for ANBQ chewing between groups was 0.281 (95% CI: 0.111 – 0.710), indicating that the BENIT intervention led to a 72% reduction in ANBQ chewing as compared to the control condition, after adjustment.

4. Discussion

This analysis of BENIT outcomes revealed strong self-reported intervention effects at the 22-day post-baseline assessment. Participant self-reports of 38.6% cessation for those in the intervention condition versus 9.1% cessation for those in the control condition met the Stage 3 criteria for early termination of the trial. This finding suggests that intensive cessation programs such as BENIT should be further developed and implemented in larger populations.

Although the results of the current study are robust, several limitations should be noted. Because bio-verification results are pending, the current findings are based solely on trial participant self-reports. However, verification of self-reported ANBQ abstinence was cross-verified using two different survey items. Further, participants were aware that their survey answers would be bio-verified with saliva samples collected at each assessment point, which likely encouraged accurate self-reports of chewing status. The results presented are ‘per protocol’ and did not include 29 participants (14 for control and 15 for intervention) who withdrew from the study prior to the 22-day assessment. Randomization did not result in balanced arms for all important variables. Specifically, several substantial differences in baseline characteristics were observed between intervention and control condition participants, particularly with regard to sex and age, though controlling for age and sex did not affect the significance of the results. These differences likely were due to allowance for groups to be randomized together.

Despite these limitations, it appears that the rationale for BENIT is supported, and that a cessation program focused on ANBQ chewers who want to quit holds great potential for ANBQ chewers in Guam and Saipan, and possibly other countries in the western Pacific, and other regions where ANBQ consumption is high. The results suggest that additional studies of intensive ANBQ cessation interventions are warranted.

Mehrtash et al. [

9] recently suggested—and we agree—that progress in ANBQ research should build towards a framework similar to that which has been established for smoking cessation. Such a framework would entail elements such as clinical guidelines, evidence-based cessation and prevention interventions, validated bio-markers for ANBQ use, and an array of pharmaceutical products to aid cessation attempts. The success of the BENIT intervention makes a significant contribution towards that overarching goal.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization; funding acquisition; supervision; writing – original draft, T.A.H. Formal analysis, L.R.W. and G.B. Data curation; resources, A.J.M. Project administration; investigation, A.A.F. Project administration; investigation, P.P. Data curation, J.S.N.C, L.F.T., and P.P.S. Project administration; resources, C.T.K. Conceptualization; funding acquisition; writing – review & editing, Y.C.P.

Funding

This research was funded by the National Cancer Institute: The University of Guam/University of Hawaii Cancer Center Partnership to Advance Cancer Health Equity, Grant U54CA143728 (University of Guam, YCP)/Grant U54CA143727 (University of Hawaii Cancer Center, TAH and AAF) and the University of Hawaii Cancer Center Support Grant (P30CA071789, AAF).

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Institutional Review Board of the University of Guam (#16-04, approved May 13, 2016). The University of Guam IRB monitored the study for both study locations (Guam and Saipan) because Saipan does not have an IRB suitable for monitoring a randomized trial.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study and all participants were compensated for their time.

Data Availability Statement

Data will be shared pursuant to the data and sharing specimen poly and procedures of the Pacific Island Partnership for Cancer Health Equity (PIPCHE). Contact information: Hali R. Robinette at the University of Hawaii Cancer Center (hali@cc.hawaii.edu, ph: 808-564-5923).

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to gratefully thank Kennedy Benjamin, Mamie Ikeda, Claudine Atalig, Janet Santos, Arlene Sibetang, Dr. Robert Gatewood, Dr. Kenneth Pierson, Jonas Macapinlac, Michelle Conerly and Kyle Santos for assistance with the production of BENIT recruitment commercials; Dr. John Moss, Casierra Cruz and Tayna Belyeu-Camacho for assistance with the initial BENIT developmental research; Elua Mori and Chandra Legdesog for assistance with data collection; Mr. Juan Babauta, the Commonwealth Cancer Association, the Guam Comprehensive Cancer Control Coalition and the U54 University of Guam /University of Hawaii Cancer Center Communication Outreach Core for assistance with recruitment and referrals; and Jennifer Lai for assistance with manuscript edits and submission.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

References

- Gupta, P.C. and S. Warnakulasuriya, Global epidemiology of areca nut usage. Addict Biol, 2002. 7(1): p. 77-83. [CrossRef]

- Paulino, Y.C. , et al., Areca (Betel) Nut Chewing Practices in Micronesian Populations. Hawaii Journal of Public Health, 2011. 3(1): p. 19-29.

- Paulino, Y.C. , et al., Epidemiology of areca (betel) nut use in the mariana islands: Findings from the University of Guam/University of Hawai`i cancer center partnership program. Cancer Epidemiol, 2017. 50(Pt B): p. 241-246. [CrossRef]

- Ichiho, H.M., B. Robles, and N. Aitaoto, An assessment of non-communicable diseases, diabetes, and related risk factors in the commonwealth of the Northern Mariana Islands: a systems perspective. Hawaii J Med Public Health, 2013. 72(5 Suppl 1): p. 19-29.

- IARC, Betel-quid and areca-nut chewing and some areca-nut derived nitrosamines. IARC Monogr Eval Carcinog Risks Hum, 2004. 85: p. 1-334.

- Gupta, B. and N.W. Johnson, Systematic review and meta-analysis of association of smokeless tobacco and of betel quid without tobacco with incidence of oral cancer in South Asia and the Pacific. PLoS One, 2014. 9(11): p. e113385. [CrossRef]

- WHO, Review of areca (betel) nut and tobacco use in the Pacific: a technical report, WHO, Editor. 2012: Geneva.

- Warnakulasuriya, S., P. Chaturvedi, and P.C. Gupta, Addictive Behaviours Need to Include Areca Nut Use. Addiction, 2015. 110(9): p. 1533. [CrossRef]

- Mehrtash, H. , et al., Defining a global research and policy agenda for betel quid and areca nut. Lancet Oncol, 2017. 18(12): p. e767-e775. [CrossRef]

- Herzog, T.A. and P. Pokhrel, Introduction to the Special Issue: International Research on Areca Nut and Betel Quid Use. Subst Use Misuse, 2020. 55(9): p. 1383-1384. [CrossRef]

- Lee, C.Y. , et al., Qualitative study for betel quid cessation among oral cancer patients. PLoS One, 2018. 13(7): p. e0199503. [CrossRef]

- Tamí-Maury, I. , et al., A qualitative study of attitudes to and perceptions of betel quid consumption and its oral health implications in Taiwan. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol, 2019. 47(1): p. 58-64. [CrossRef]

- Papke, R.L., D. K. Hatsukami, and T.A. Herzog, Betel Quid, Health, and Addiction. Subst Use Misuse, 2020. 55(9): p. 1528-1532.

- Hung, C.C. , et al., Effect of antidepressants for cessation therapy in betel-quid use disorder: a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Epidemiol Psychiatr Sci, 2020. 29: p. e125. [CrossRef]

- Paulino, Y.C. , et al., Rationale and design of a randomized, controlled, superiority trial on areca nut/betel quid cessation: The Betel Nut Intervention Trial (BENIT). Contemp Clin Trials Commun, 2020. 17: p. 100544. [CrossRef]

- Brown, R. , Intensive behavioral treatment. The tobacco dependence treatment handbook: A guide to best practices, 2003: p. 118-177.

- Herzog, T.A. , et al., The Betel Quid Dependence Scale: replication and extension in a Guamanian sample. Drug Alcohol Depend, 2014. 138: p. 154-60. [CrossRef]

- Little, M.A. , et al., Intention to quit betel quid: a comparison of betel quid chewers and cigarette smokers. Oral Health Dent Manag, 2014. 13(2): p. 512-8.

- Moss, J. , et al., Developing a Betel Quid Cessation Program on the Island of Guam. Pac Asia Inq, 2015. 6(1): p. 144-150.

- Paulino, Y.C. , et al., Screening for oral potentially malignant disorders among areca (betel) nut chewers in Guam and Saipan. BMC Oral Health, 2014. 14: p. 151. [CrossRef]

- Friedman, L.M., C. D. Furberg, and D.L. DeMets, Fundamentals of clinical trials. 3rd ed. 1998, New York: Springer.

- Perkins, K.A., C. A. Conklin, and M.D. Levine, Cognitive-behavioral therapy for smoking cessation: a practical guidebook to the most effective treatments. 2008: Routledge.

- Lee, C.Y. , et al., Development and validation of a self-rating scale for betel quid chewers based on a male-prisoner population in Taiwan: the Betel Quid Dependence Scale. Drug Alcohol Depend, 2012. 121(1-2): p. 18-22. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).