Submitted:

16 June 2023

Posted:

16 June 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

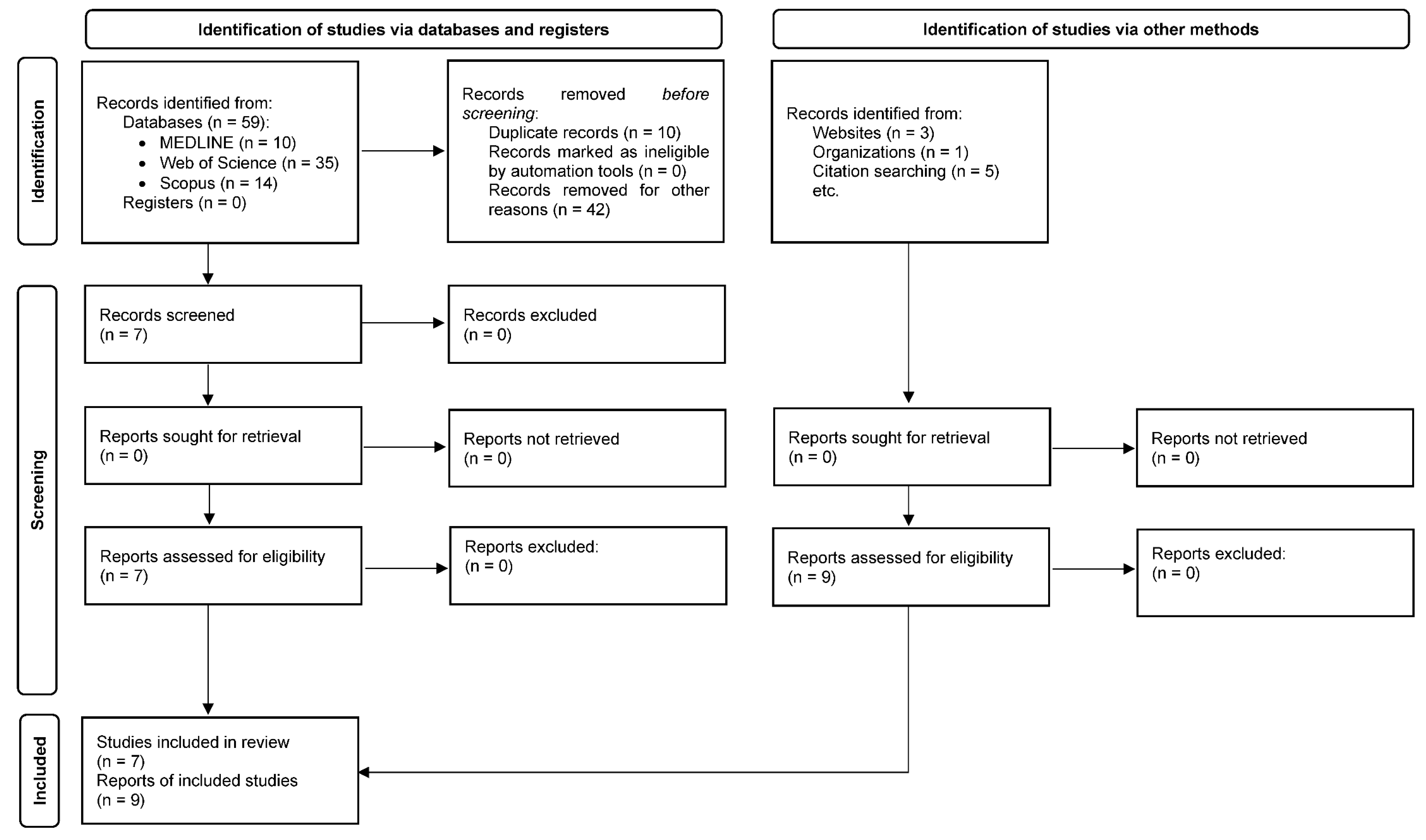

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Design and Procedure

2.2. Source of Data Collection

2.3. Information Search

- -

- Population: adults with ESRD aged 18 years or older.

- -

- Intervention: medication review.

- -

- Outcome: DRPs and NOMs.

2.4. Study Selection

- 1)

- Articles written in a language other than English, Portuguese, or Spanish.

- 2)

- Articles without an abstract.

- 3)

- Articles that do not mention any MRF in patients with ESRD.

- 4)

- Articles that do not mention DRPs or NOMs in patients with ESRD.

- 5)

- Articles mentioning patients under 18 years of age.

- 6)

- Articles without a methods section, review articles, or case reports.

2.5. Data extraction

2.6. Study Variables

- -

- Author, year and country: first author of the article selected, year of publication of the article, and location where the study took place.

- -

- Study design and duration: procedures, methods, and techniques through which the article was accepted for review. Duration of the study.

- -

- Population studied: adults with ESRD (age, ethnicity, sex).

- -

- Study aim: objective or aim of the study.

- -

- DRPs: Total, type, and frequency of DRPs.

- -

- NOMs: Total, type, and frequency of NOMs.

- -

- Pharmacist interventions: Total and relevant findings of pharmacist interventions related to DRPs and NOMs.

- -

- Types of medication most commonly associated with DRPs/NOMs.

2.7. Methodological Quality Assessment

3. Results

3.1. Study Characteristics and Quality

3.2. Medication Review with Follow-up Method

3.3. Drug-Related Problems

3.4. Negative Outcomes Associated with Medication

3.5. Pharmacist’s Interventions

3.6. Quality

4. Discussion

5. Conclusion

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Lv J, Zhang L. Prevalence and disease burden of chronic kidney disease. Adv Exp Med Biol. 2019;1165:3–15. [CrossRef]

- Salgado TM, Moles R, Benrimoj SI, Fernandez-Llimos F. Pharmacists’ interventions in the management of patients with chronic kidney disease: a systematic review. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2012;27:276–92. [CrossRef]

- Levey AS, Atkins R, Coresh J et al. Chronic kidney disease as a global public health problem: approaches and initiatives – a position statement from Kidney Disease Improving Global Outcomes. Kidney Int. 2007;72:247–59. [CrossRef]

- de Boer IH, Caramori ML, Chan JCN et al. KDIGO 2020 clinical practice guideline for diabetes management in chronic kidney disease. Kidney Int. 2020;98:S1–S115. [CrossRef]

- International Society of Nephrology. KDIGO 2012 Clinical Practice Guideline for the Evaluation and Management of Chronic Kidney Disease. 2013.

- Levin A, Stevens PE, Bilous RW et al. Kidney disease: improving global outcomes (KDIGO) CKD work group. KDIGO 2012 clinical practice guideline for the evaluation and management of chronic kidney disease. Kidney Int Suppl. 2013;3:1–150.

- Brück K, Stel VS, Gambaro G et al. CKD prevalence varies across the European general population. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2016;27:2135–47. [CrossRef]

- Pai AB, Cardone KE, Manley HJ et al. Medication reconciliation and therapy management in dialysis-dependent patients: need for a systematic approach. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2013;8:1988–99. [CrossRef]

- Manley HJ, Cannella CA, Bailie GR, St Peter WL. Medication-related problems in ambulatory hemodialysis patients: a pooled analysis. Am J Kidney Dis. 2005;46:669–80. [CrossRef]

- Alruqayb WS, Price MJ, Paudyal V, Cox AR. Drug-related problems in hospitalised patients with chronic kidney disease: a systematic review. Drug Saf. 2021;44:1041–58. [CrossRef]

- Adibe MO, Igboeli NU, Ukwe CV. Evaluation of drug therapy problems among renal patients receiving care in some tertiary hospitals in Nigeria. Trop J Pharm Res. 2017;16:697–704. [CrossRef]

- Arroyo Monterroza DA, Castro Bolivar JF. Seguimiento farmacoterapéutico en pacientes con insuficiencia renal crónica. Farm Hosp. 2017;41:137-49. [CrossRef]

- Ramadaniati HU, Anggriani Y, Wowor VM, Rianti A. Drug-related problems in chronic kidneys disease patients in an Indonesian hospital: do the problems really matter? Int J Pharm Pharm Sci. 2016;8:298–302. [CrossRef]

- Alkatheri A. Pharmacist effectiveness in reducing medication related problems in dialysis patients. Saudi Pharm J. 2004;12:54–59.

- Belaiche S, Romanet T, Bell R, Calop J, Allenet B, Zaoui P. Pharmaceutical care in chronic kidney disease: experience at Grenoble University Hospital from 2006 to 2010. J Nephrol. 2012;25:558–65. [CrossRef]

- Gheewala PA, Peterson GM, Curtain CM, Nishtala PS, Hannan PJ, Castelino RL. Impact of the pharmacist medication review services on drug-related problems and potentially inappropriate prescribing of renally cleared medications in residents of aged care facilities. Drugs Aging. 2014;31:825–35. [CrossRef]

- Manley HJ, Carroll CA. The clinical and economic impact of pharmaceutical care in end-stage renal disease patients. Semin Dial. 2002;15:45–49. [CrossRef]

- Via-Sosa MA, Lopes N, March M. Effectiveness of a drug dosing service provided by community pharmacists in polymedicated elderly patients with renal impairment—a comparative study. BMC Fam Pract. 2013;14:96. [CrossRef]

- Belaiche S, Romanet T, Allenet B, Calop J, Zaoui P. Identification of drug-related problems in ambulatory chronic kidney disease patients: a 6-month prospective study. J Nephrol. 2012;25:782–88. [CrossRef]

- Manley HJ, Drayer DK, Muther RS. Medication-related problem type and appearance rate in ambulatory hemodialysis patients. BMC Nephrol. 2003;4:10. [CrossRef]

- Manley HJ, McClaran ML, Overbay DK et al. Factors associated with medication-related problems in ambulatory hemodialysis patients. Am J Kidney Dis. 2003;41:386–93. [CrossRef]

- Njeri LW, Ogallo WO, Nyamu DG, Opanga SA, Birichi AR. Medication-related problems among adult chronic kidney disease patients in a sub-Saharan tertiary hospital. Int J Clin Pharm. 2018;40:1217–24. [CrossRef]

- Quintana-Bárcena P, Lord A, Lizotte A, Berbiche D, Lalonde L. Prevalence and management of drug-related problems in chronic kidney disease patients by severity level: a subanalysis of a cluster randomized controlled trial in community pharmacies. J Manag Care Spec Pharm. 2018;24:173–81. [CrossRef]

- Song Y, Jeong S, Han N et al. Effectiveness of clinical pharmacist service on drug-related problems and patient outcomes for hospitalized patients with chronic kidney disease: a randomized controlled trial. J Clin Med. 2021;10:1788. [CrossRef]

- Garedow AW, Mulisa Bobasa E, Desalegn Wolide A et al. Drug-related problems and associated factors among patients admitted with chronic kidney disease at Jimma University Medical Center, Jimma Zone, Jimma, Southwest Ethiopia: a hospital-based prospective observational study. Int J Nephrol. 2019;2019:1504371. [CrossRef]

- Arroyo Monterroza DA, Castro Bolivar JF. Pharmaceutical care practice in patients with chronic kidney disease. Farm Hosp. 2017;41:137–49. [CrossRef]

- Mason NA, Bakus JL. Strategies for reducing polypharmacy and other medication-related problems in chronic kidney disease. Semin Dial. 2010;23:55–61. [CrossRef]

- Kim AJ, Lee H, Shin E et al. Pharmacist-led collaborative medication management for the elderly with chronic kidney disease and polypharmacy. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2021;18:4370. [CrossRef]

- Susilawati NM, Halimah E, Saidah S. Pharmacists’ strategies to detect, resolve, and prevent DRPs in CKD patients. Pharmacia. 2021;68:619–26. [CrossRef]

- Chemello C, Aguilera M, Calleja-Hernández MA, Faus MJ. Efecto del seguimiento farmacoterapéutico en pacientes con hiperparatiroidismo secundario tratados con cinacalcet. Farm Hosp. 2012;36:321–27. [CrossRef]

- Cardone KE, Parker WM. Medication management in dialysis: barriers and strategies. Semin Dial. 2020;33:449–56. [CrossRef]

- Manley HJ, Carroll CA. The clinical and economic impact of pharmaceutical care in end-stage renal disease patients. Semin Dial. 2002;15:45–49. [CrossRef]

- Pharmaceutical Care Network Europe (PCNE). The Definition of Drug-Related Problems. 2009.

- Faus-Dáder MJ, Amariles-Muñoz P, Martínez-Martínez F. Atención farmacéutica. Servicios farmacéuticos orientados al paciente. 2nd edn. Granada: Técnica Avicam, 2022.

- Varas-Doval R, Gastelurrutia MA, Benrimoj SI et al. Evaluating an implementation programme for medication review with follow-up in community pharmacy using a hybrid effectiveness study design: translating evidence into practice. BMJ Open. 2020;10:e036669. [CrossRef]

- Pai AB, Cardone KE, Manley HJ et al. Medication reconciliation and therapy management in dialysis-dependent patients: need for a systematic approach. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2013;8:1988–99. [CrossRef]

- Chemello C. Atención farmacéutica al paciente con insuficiencia renal crónica: seguimiento farmacoterapéutico y farmacogenética. Granada: Universidad de Granada, 2011.

- Chemello C, Aguilera-Gómez M, Calleja-Hernández MA, Faus-Dader MJ. Implantación del método Dáder para el seguimiento farmacoterapéutico de pacientes tratados con cinecalcet. Ars Pharmaceutica Suppl.1. 2009;50:45–46.

- Varas-Doval R, Gastelurrutia MA, Benrimoj SI, García-Cárdenas V, Sáez-Benito L, Martinez-Martínez F. Clinical impact of a pharmacist-led medication review with follow up for aged polypharmacy patients: a cluster randomized controlled trial. Pharm Pract (Granada). 2020;18:2133. [CrossRef]

- Griese-Mammen N, Hersberger KE, Messerli M et al. PCNE definition of medication review: Reaching agreement. Int J Clin Pharm. 2018;40:1199–1208. [CrossRef]

- Alruqayb WS, Price MJ, Paudyal V, Cox AR. Drug-related problems in hospitalised patients with chronic kidney disease: a systematic review. Drug Saf. 2021;44:1041–58. [CrossRef]

- Cardone KE, Bacchus S, Assimon MM, Pai AB, Manley HJ. Medication-related problems in CKD. Adv Chronic Kidney Dis. 2010;17:404–12. [CrossRef]

- Page MJ, McKenzie JE, Bossuyt PM et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: an updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ. 2021;372:n71. [CrossRef]

- Pereira-Céspedes A, Jiménez-Morales A, Martínez-Martínez F, Calleja-Hernández MÁ. A systematic review of medication review with follow-up for end stage renal disease: drug related problems and negative outcomes associated with medication. PROSPERO 2022 CRD42022324729. 2022.

- Vandenbroucke JP, von Elm E, Altman DG et al. Strengthening the reporting of observational studies in epidemiology (STROBE): explanation and elaboration. Int J Surg. 2014;12:1500–24. [CrossRef]

- Possidente CJ, Bailie GR, Hood VL. Disruptions in drug therapy in long-term dialysis patients who require hospitalization. Am J Health Syst Pharm. 1999;56:1961–64. [CrossRef]

- Chisholm MA, Vollenweider LJ, Mulloy LL, Jagadeesan M, Wade WE, DiPiro JT. Direct patient care services provided by a pharmacist on a multidisciplinary renal transplant team. Am J Health Syst Pharm. 2000;57:1994–96. [CrossRef]

- George CR, Jacob D, Thomas P, Ravinandan AP, Srinivasan R, Thomas J. Study of drug related problems in ambulatory hemodialysis patients. IOSR J Pharm Biol Sci (IOSR-JPBS). 2017;12:32–36.

- Peri, Nasution A, Nasution AT. The role of pharmacists’ interventions in improving drug-related problems, blood pressure, and quality of life of patients with stage 5 chronic kidney disease. Pharmacia. 2022;69:175–80. [CrossRef]

- Chua PCP, Low CL, Lye WC. Drug-related problems in hemodialysis patients. Hemodial Int. 2003;7:73–104.

- Alshamrani M, Almalki A, Qureshi M, Yusuf O, Ismail S. Polypharmacy and medication-related problems in hemodialysis patients: a call for deprescribing. Pharmacy (Basel). 2018;6(3):76. [CrossRef]

- Lumbantobing R, Sauriasari R, Andrajati R. Role of pharmacists in reducing drug-related problems in hemodialysis outpatients. Asian J Pharm Clin Res. 2017;10:108-13. [CrossRef]

- Grabe DW, Low CL, Bailie GR, Eisele G. Evaluation of drug-related problems in an outpatient hemodialysis unit and the impact of a clinical pharmacist. Clin Nephrol. 1997;47:117–21.

- Wang HY, Chan ALF, Chen MT, Liao CH, Tian YF. Effects of pharmaceutical care intervention by clinical pharmacists in renal transplant clinics. Transplant Proc. 2008;40:2319–23. [CrossRef]

- Mirkov S. Implementation of a pharmacist medication review clinic for haemodialysis patients. N Z Med J. 2009;122:25–37.

- Chen LL. A preliminary review of the medication management service conducted by pharmacists in haemodialysis patients of Singapore General Hospital. Proc Singapore Healthcare. 2013;22:103–06.

- Manley HJ, Aweh G, Weiner DE et al. Multidisciplinary medication therapy management and hospital readmission in patients undergoing maintenance dialysis: a retrospective cohort study. Am J Kidney Dis. 2020;76:13–21. [CrossRef]

- Daifi C, Feldpausch B, Roa P-A, Yee J. Implementation of a clinical pharmacist in a hemodialysis facility: a quality improvement report. Kidney Med. 2021;3:241–47.e1. [CrossRef]

- Strand LM, Morley PC, Cipolle RJ, Ramsey R, Lamsam GD. Drug-related problems: their structure and function. DICP. 1990;24:1093–97. [CrossRef]

| Participants, demographics | DRPs | NOMs | Pharmacist interventions | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| First author, year, country, ref. no. | Study design (duration) | Study setting | N (at baseline) | Sex n (%) |

Age mean (SD) | Ethnicity (%) | Aim | Total (n) | Type and frequency (%) | Total (n) | Type and frequency. (%) | Total (n) | Relevant findings | Types of medication most commonly associated with DRPs/NOMs |

| Grabe 1997 U.S.A. [53] |

Observational retrospective (1 month) | Outpatient HD unit | 45 HD | 24 (53.3) male, 21 (46.7) female. | 52 (16) | Not reported | To identify DRPs in hemodialysis outpatients by performing medication reviews, make appropriate recommendations, determine the significance of any interventions, and estimate outcome in terms of any changes in number of medications/ patient or doses/day. | 126 | Drug interactions (27.5). | Not reported | Not reported | 102 | Most of the interventions were significant and possibly led to better therapeutic outcomes. | Not reported |

| Possidente 1999 U.S.A. [46] |

Observational prospective (1 month) | University teaching hospital | 37 (31 HD, 6 PD) | 19 (51.4)male, 18 (48.7) female | 65.9 (12.7) | Caucasian (97.3), Hispanic (2.7) | To evaluate the continuity of drug therapy and identify and resolve DRPs during the complete hospitalization process in patients receiving long-term dialysis. | 161 | Failure to receive a prescribed drug (41.0), problems related to drug dosage, either overdosage or underdosage (25.5), drug interactions (1.9), therapeutic duplication (2.5), and ADRs (1.2) | Not reported | Not reported | Not reported | Physicians agreed with 96% of the pharmacist recommendations, indicating strong support for pharmacist assistance in monitoring drug therapy. | Medications for mineral bone disorder, antianemic preparations, and anti-infectives |

| Chisholm 2000 U.S.A. [47] |

Observational prospective (18 months) | Ambulatory care RT | 201 KT | Not reported | Not reported | Not reported | To document the number and types of recommendations made by a pharmacist to the multidisciplinary renal transplant team, to determine the rate of acceptance of the recommendations, and to determine the potential impact of the recommendations on patient care. | 811 | Untreated indication (28.4), overdose (26.6), subtherapeutic dosage (18.1), medication use without an indication (10.1), ADRs (7.6), improper medication selection (7.0), failure to receive medication (2.1). | Not reported | Not reported | 844 | 96% (n = 811) were accepted. Nearly all (99%) of the accepted recommendations were judged to have a significant, very significant, or extremely significant potential impact on patient care | Immunosuppressants and cardiovascular medications |

| Manley 2003 U.S.A. [20] |

Clinical trial randomly selected controlled (10 months) | Non-profit outpatient dialysis unit | 133 HD (66 pharmaceutical care group; 79 usual care group). | 74 (55.6) male, 59 (44.4) female |

62.8 (15.0) | Black (78.2), Caucasian (17.3), other (4.5) | To determine the rate, number, type, severity, and appearance of DRPs, as identified through pharmaceutical care activities, in patients with ambulatory HD. | 354 | Medication dosing problems (33.5), ADRs (20.7), and an indication that was not currently being treated (13.5) | Not reported | Not reported | Not reported | Not reported | Cardiovascular medications (29.7%), endocrine medications (15.5%), and specific medications (medications for mineral bone disorder, antianemic preparations) (15%) |

| Chua 2003 Singapore [50] |

Observational prospective (3 months) | HD center | 31 HD | Not reported | Not reported | Not reported | To identify DRPs in HD patients, intervene, and resolve them. | 83 | Drug underdose (35) | Not reported | Not reported | 73 | 62% of the accepted recommendations were classified as significant | Not reported |

| Wang 2008 Taiwan [54] |

Clinical trial enrolled subjects uncontrolled (15 months) | RT clinics | 37 KT | 20 (54.1) female, 17 (45.9) male |

Not reported Age range 22-60 years | Not reported | To investigate the effects on treatment results of clinical pharmacists joining RT clinics to provide pharmaceutical care. | 55 | Medication selection (84.5), improper laboratory data (12.7), dosage adjustment (14.5), ADRs (10.9), untreated indications and medication use without an Indication (9.1), failure to receive medication (5.5), other (3.6) | Not reported | Not reported | 55 | 81.8% were classified as clinically significant. The mean acceptance rate of physicians for the types of recommendation was 96.0% | Cardiovascular medications (32.6%), immunosuppressants (23.9%), and antimetabolites (26.1%) |

| Mirkov 2009 New Zealand [55] |

Observational prospective (7 months) | HD units | 64 HD | 39 (60.9) female, 25 (39.1) male |

65 (Not reported) Age range 24–82 years |

Pacific People (46.9),New Zealand Maori (25),European (20.3),Other (7.8) | To implement the pharmacist medication review clinic and establish a sustainable clinical pharmacy service. | 278 | Non-adherence to medication regimen (33.0), medication requiring dose decrease (9.3), indication requiring new medication (8.6). | Not reported | Not reported | 493 | Not reported | Not reported |

| Chemello 2012 Spain [30,37] |

Quasi-experimental pre-post-intervention study (12 months) | Hospital | 34 (19 HD, 15 KT) | 17 (50.0) female, 17 (50.0) male |

51.5 (12.4) | Not reported | To assess the effect of pharmaceutical intervention on the identification of DRPs, improve desired clinical outcomes, and evaluate the effectiveness of cinacalcet in achieving clinical outcomes recommended by the Kidney Disease Outcomes Quality Initiative (KDOQI) Clinical Guidelines. | 29 | Non adherence (51.7), ADRs (13.8), Drug interaction (3.5), therapeutic duplication (3.5), wrong dosage administered (6.9) | 9 | Untreated health problem (11.1), quantitative ineffectiveness (22.2), non-quantitative safety problem (55.6), quantitative safety problem. (11.1) | 34 | After the intervention, 9 drug-related problems remained, which means that 68.9% of them were resolved (P < 0.001), reaching an adherence of 80%. Parathyroid hormone, calcium and calcium-phosphorus product serum levels decreased significantly after 3 months of treatment (P < 0.001, < 0.001 and 0.045 respectively), achieving the KDOQI Clinical Guideline recommendations. | Cinecalcet |

| Chen 2013 Singapore [56] |

Observational prospective (5 months) | General hospital | 30 HD | 15 (50.0) female, 15 (50.0) male |

62.3 (10.0) | Chinese (73.3) | To evaluate the prevalence of DRPs identified and the types of interventions made by pharmacists. | 94 | Drugs with no indication (2,1), therapeutic duplication (8.5), untreated indication (14.9), improper selection of drugs (5.3), overdose of drugs (9.6), underdose of drugs (1.1), drug-drug interactions (1.1), drug-food interactions (1.1), non-adherence (41.5), ADRs (11.7), administration issues (3.2). | Not reported | Not reported | 54 | Almost half involved suggestions to modify dosing regimens (51.9%), followed by suggestions to add new drugs (16.7%) and to increase the doses, discontinue drugs (13.0%). Total DRPs solved (%): 63 (67.0%) | Not reported |

| George 2017 India [48] |

Observational prospective (6 months) | Hospital | 79 HD | 56 (70.9) male, 23 (29.1) female |

Not reported | Not reported | To determine DRPs in HD patients. | 301 | Drug interactions (86.4), ADRs (5.0), indication without drug therapy (4.0), improper drug selection (1.3), overdose (3.0), failure to receive drug (0.3). | Not reported | Not reported | Not reported | Not reported | Not reported |

| Lumbantobing 2017 Indonesia [52] |

Observational prospective (5 months) | HD unit | 86 HD | 45 (52.3) male, 41 (47.6) female |

Not reported Age range 41-60 years |

Not reported | To identify DRPs and assess the effect of pharmacist intervention on the number and types of DRPs in HD outpatients | 337 | Failed therapy (18.7), suboptimal therapeutic effects (52.2), indications of non-administration of drugs (2.4), non-allergic adverse drug effects (26.7). | Not reported | Not reported | 277 | Not reported | Calcium carbonate, ferrous sulfate, erythropoiesis-stimulating agents, and omeprazole |

| Alshamrani 2018 Saudi Arabia [51] |

Observational prospective cross-sectional (2 months) |

Outpatient HD unit | 83 HD | 42 (51) males, 41 (49.4) female |

63 (not reported) | Not reported | To determine the prevalence of polypharmacy and DRPs in HD patients | 280 | Medication use without indication (36.0), subtherapeutic dosing (23.0), overdosing (15.0), deprescribing of medication (41.0), medication use without indication (89.0), duplicate therapy (11.0), drug interaction (n = 184) | Not reported | Not reported | 280 | Not reported | Medications for gastrointestinal or acid-related disorders, cardiovascular medications, and antidepressants |

| Manley 2020 U.S.A. [57] |

Retrospective cohort study (12 months) |

Dialysis clinics |

726 ESRDHD (89%) | 334 (46) female, 392 (54) male |

64 (15) | White (46), black (43), other (4), unknown (8) | Not reported | 5466 potential | Medication dosing issues (31.0), comprising “dose too high” (22.0) and “dose too low” (9.0), actual or potential ADRs (29.0), unnecessary drug therapy (17.0). | Not reported | Not reported | Not reported | Not reported | Cardiovascular medications, medications for gastrointestinal or acid-related disorders, analgesics and endocrine and metabolic medications. |

| Daifi 2021 U.S.A [58] |

Retrospective (14 months) | HD facilities | 157 HD | 81 (52) female, 76 (48) male |

63.0 (not reported)Age range: 26–92 years | African American (79), White (4), Hispanic (6), other (11) | To evaluate the impact of a clinical pharmacist in an HD facility by assessing the efficacy of medication reconciliation in HD patients and evaluating the potential impact on the health system through estimated cost avoidance. | 1407 | Non-adherence (31.0), ADRs (2.6), dose too high (4.6), dose too low (13.1), needs additional drug therapy (21.5), unnecessary drug therapy (8.8), wrong dose (4.5), additional/ other DRP (0.6), drug-drug interaction (1.1), cost, accessibility, refills (11.9). | Not reported | Not reported | 964 | Not reported | Antihypertensives, vitamin D analogues and calcimimetics. |

| Peri 2022 Indonesia [49] |

Analytical cohort study (6 months) | Hospital | 83 HD | 54 (65) male, 29 (35) female |

48.91 (not reported) Age range 11–61 years |

Not reported | To analyze the impacts of pharmacy interventions on DRPs, blood pressure, and quality of life in HD | 470 | Sub-optimal drug effects (50.85), untreated symptoms (22.1), no drug effect (8.9), ADRs (17.7) | Not reported | Not reported | 470 | Not reported | Not reported |

| Questionnaire elements | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| First author, year, country, ref. no. | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 | 15 | 16 | 17 | 18 | 19 | 20 | 21 | 22 | Total | % | |

| Grabe 1997 U.S.A. [53] |

1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 21 | 95.45 | |

| Possidente 1999 U.S.A. [46] |

1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 19 | 83.36 | |

| Chisholm 2000 U.S.A. [47] |

1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 16 | 72.73 | |

| Manley 2003 U.S.A. [20] |

NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | |

| Chua 2003 Singapore [50] |

1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 11 | 50 | |

| Wang 2008 Taiwan [54] |

NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | |

| Mirkov 2009 New Zealand [55] |

1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 20 | 90.91 | |

| Chemello 2012 Spain [30,37] |

1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 22 | 100 | |

| Chen 2013 Singapore [56] |

1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 18 | 81.82 | |

| George 2017 India [48] |

1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 16 | 72.73 | |

| Lumbantobing 2017 Indonesia [52] |

1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 17 | 77.27 | |

| Alshamrani 2018 Saudi Arabia [51] |

1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 21 | 95.45 | |

| Manley 2020 U.S.A. [57] |

1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 22 | 100 | |

| Daifi 2021 U.S.A [58] |

1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 22 | 100 | ||

| Peri 2022 Indonesia [49] |

1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 16 | 72.73 | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).