Submitted:

13 June 2023

Posted:

13 June 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Glick, M.; Williams, D.M.; Kleinman, D.V.; Vujicic, M.; Watt, R.G.; Weyant, R.J. A new definition for oral health developed by the FDI World Dental Federation opens the door to a universal definition of oral health. J. Public Health Dent. 2017, 77, 3–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- World Health Organization: Draft Global Oral Health Action Plan (2023-2030). Available online: https://www.who.int/publications/m/item/draft-global-oral-health-action-plan-(2023-2030) (accessed on 11 April 2023).

- World Health Organization: Global oral health status report: towards universal health coverage for oral health by 2030. Available online: https://www.paho.org/en/documents/global-oral-health-status-report-towards-universal-health-coverage-oral-health-2030 (accessed on 11 April 2023).

- Gallagher, J.; Ashley, P.; Petrie, A.; Needleman, I. Oral health and performance impacts in elite and professional athletes. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol. 2018, 46, 563–568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ashley, P.; Di Iorio, A.; Cole, E.; Tanday, A.; Needleman, I. Oral health of elite athletes and association with performance: a systematic review. Br J Sports Med. 2015, 49, 14–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Opazo-García, C.; Moya-Salazar, J.; Chicoma-Flores, K.; Contreras-Pulache, H. Oral health problems in high-performance athletes at 2019 Pan American Games in Lima: a descriptive study. BDJ open. 2021, 7, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bryant, S.; McLaughlin, K.; Morgaine, K.; Drummond, B. Elite athletes and oral health. Int J Sports Med. 2011, 32, 720–724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stamos, A.; Mills, S.; Malliaropoulos, N.; Cantamessa, S.; Dartevelle, J.-L.; Gündüz, E. The European Association for Sports Dentistry, Academy for Sports Dentistry, European College of Sports and Exercise Physicians consensus statement on sports dentistry integration in sports medicine. Dent Traumatol. 2020, 36, 680–684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roettger, M.; Mills, S. Modern Sports Dentistry. 1st ed.; Springer Cham, Switzerland, 2018; pp. 3–6.

- Sousa, M.; Mendes, J.J.; Godinho, C. Medicina Dentária Desportiva: Ideologia ou Necessidade? Proelium 2016, 7, 135–164. [Google Scholar]

- Needleman, I.; Ashley, P.; Fine, P.; Haddad, F.; Loosemore, M.; de Medici, A.; et al. Oral health and elite sport performance. Br J Sports Med 2015, 49, 3–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- de la Parte, A.; Monticelli, F.; Toro-Román, V.; Pradas, F. Differences in Oral Health Status in Elite Athletes According to Sport Modalities. Sustainability. 2021, 13, 7282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hinds, L. Sports drinks and their impact on dental health. BDJ Team. 2019, 6, 11–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tripodi, D.; Cosi, A.; Fulco, D.; D’Ercole, S. The Impact of Sport Training on Oral Health in Athletes. Dent J. 2021, 9, 51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gleeson, M.; McDonald, W.A.; Pyne, D.B.; Cripps, A.W.; Francis, J.L.; Fricker, P.A. Salivary IgA levels and infection risk in elite swimmers. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 1999, 31, 67–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Needleman, I.; Ashley, P.; Petrie, A.; Fortune, F.; Turner, W.; Jones, J. Oral health and impact on performance of athletes participating in the London 2012 Olympic Games: a cross-sectional study. Br J Sports Med. 2013, 47, 1054–1058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cardoso, F.; Monteiro, A.S.; Fernandes, A.; Vilas-Boas, J.P.; Pinho, J.C.; Pyne, D.B.; Fernandes, R.J. Oral health in young elite swimmers. Trends Sport Sci. 2020, 27, 49–55. [Google Scholar]

- Rios, M.; Fernandes, R.J.; Cardoso, R.; Monteiro, A.S.; Cardoso, F.; Fernandes, A.; Silva, G.; Fonseca, P.; Vilas-Boas, J.P.; Silva, J.A. Physical Fitness Profile of High-Level Female Portuguese Handball Players. Int J Environ Res Public Health, 2023, 20, 5751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Angle, E.H. Classification of malocclusion. Dent Cosm. 1899, 41, 248–264. [Google Scholar]

- Yadav, D.; Rani, M.S.; Shailaja, A.M.; Anand, D.; Sood, N.; Gothi, R. Angle´s Molar Classification Revisited. J Indian Orthod Soc. 2014, 48, 382–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lobbezoo, F.; Ahlberg, J.; Raphael, K.G.; Wetselaar, P.; Glaros, A.G.; Kato, T. International consensus on the assessment of bruxism: report of a work in progress. J Oral Rehabil. 2018, 45, 837–844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maffetone, P.B.; Laursen, P.B. Athletes: Fit but Unhealthy? Sport Med - Open. 2016, 2, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dijkstra, H.P.; Pollock, N.; Chakraverty, R.; Alonso, J.M. Managing the health of the elite athlete: a new integrated performance health management and coaching model. Br J Sports Med. 2014, 48, 523–531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, K.; Qadir, A.; Trakman, G.; Aziz, T.; Khattak, M.I.; Nabi, G. Sports and Energy Drink Consumption, Oral Health Problems and Performance Impact among Elite Athletes. Nutrients. 2022, 14, 5089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González-Aragón Pineda, A.E.; García Pérez, A.; García-Godoy, F. Salivary parameters and oral health status amongst adolescents in Mexico. BMC Oral Health. 2020, 20, 190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Needleman, I.; Ashley, P.; Fine, P.; Haddad, F.; Loosemore, M.; Medici, A. Consensus statement: oral health and elite sport performance. Br Dent J. 2014, 21, 587–590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magalhães, I.B.; Pereira, L.J.; Marques, L.S.; Gameiro, G.H. The influence of malocclusion on masticatory performance. A systematic review. Angle Orthod. 2010, 80, 981–987. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pullinger, A.G.; Seligman, D.A.; Solberg, W.K. Temporomandibular disorders. Part II: Occlusal factors associated with temporomandibular joint tenderness and dysfunction. J Prosthet Dent. 1988, 59, 363–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Souki, B.Q.; Pimenta, G.B.; Souki, M.Q.; Franco, L.P.; Becker, H.M.G.; Pinto, J.A. Prevalence of malocclusion among mouth breathing children: do expectations meet reality? Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol. 2009, 73, 767–773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El Ouali, E.M.; Zouhal, H.; Bahije, L.; Ibrahimi, A.; Benamar, B.; Kartibou, J. Effects of Malocclusion on Maximal Aerobic Capacity and Athletic Performance in Young Sub-Elite Athletes. Sports. 2023, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maurer, C.; Stief, F.; Jonas, A.; Kovac, A.; Groneberg, D.A.; Meurer, A. Influence of the lower jaw position on the running pattern. PLoS One. 2015, 10, e013571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dias, A.A.; Redinha, L.A.; Silva, L.M.; Pezarat-Correia, P.C. Effects of Dental Occlusion on Body Sway, Upper Body Muscle Activity and Shooting Performance in Pistol Shooters. Appl bionics Biomech 2018, 2018, 9360103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mon, D.; Zakynthinaki, M.; Cordente, C.; Barriopedro, M.; Sampedro, J. Body sway and performance at competition in male pistol and rifle Olympic shooters. Biomed Hum Kinet. 2014, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Merle, C.L.; Wuestenfeld, J.C.; Fenkse, F.; Wolfarth, B.; Haak, R.; Schmalz, G. The Significance of Oral Inflammation in Elite Sports: A Narrative Review. Sport Med Int Open. 2022, 6, E69–E79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Solleveld, H.; Goedhart, A.; Vanden Bossche, L. Associations between poor oral health and reinjuries in male elite soccer players: a cross-sectional self-report study. BMC Sport Sci Med Rehabil. 2015, 7, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barnett, M.L. The oral-systemic disease connection. An update for the practicing dentist. J Am Dent Assoc. 2006, 137. [Google Scholar]

- Mealey, B.L. Periodontal disease and diabetes. A two-way street. J Am Dent Assoc. 2006, 137, S26–S31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demmer, R.T.; Desvarieux, M. Periodontal infections and cardiovascular disease: the heart of the matter. J Am Dent Assoc. 2006, 137, S14–S20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soler, B.D.; Batchelor, P.A.; Sheiham, A. The prevalence of oral health problems in participants of the 1992 Olympic Games in Barcelona. Int Dent J. 1994, 44, 44–48. [Google Scholar]

- Forrest, J.O. The dental condition of Olympic Games contestants-a pilot study. Dent Pract Dent Rec. 1969, 20, 95–101. [Google Scholar]

- Piccininni, P.M.; Fasel, R. Sports dentistry and the olympic games. J Calif Dent Assoc. 2005, 33, 471–483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, X.-J.; Schamach, P.; Dai, J.-P.; Zhen, X.-Z.; Yi, B.; Liu, H.; et al. Dental service in 2008 Summer Olympic Games. Br J Sports Med. 2011, 45, 270–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kragt, L.; Moen, M.H.; Van Den Hoogenband, C.-R.; Wolvius, E.B. Oral health among Dutch elite athletes prior to Rio 2016. Phys Sportsmed. 2019, 47, 182–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Botelho, J.; Vicente, F.; Dias, L.; Júdice, A.; Pereira, P.; Proença, L. Periodontal Health, Nutrition and Anthropometry in Professional Footballers: A Preliminary Study. Nutrients. 2021, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gay-Escoda, C.; Vieira Pereira, D.; Ardèvol, J.; Pruna, R.; Fernandez, J.; Valmaseda-Castellón, E. Study of the effect of oral health on the physical condition of professional soccer players of Football Club Barcelona. Med Oral Patol Oral Cir Bucal. 2011, 16, e436–e439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Souza, J.; Grande, R.; Bahls, R.; Santos, F. Evaluation of the oral health conditions of volleyball athletes. Rev Bras Med do Esporte. 2020, 26, 239–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ringhof, S.; Hellmann, D.; Meier, F.; Etz, E.; Schindler, H.; Stein, T. The effect of oral motor activity on the athletic performance of professional golfers. Front Psychol. 2015, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ebben, W.P.; Flanagan, E.P.; Jensen, R.L. Jaw clenching results in concurrent activation potentiation during the countermovement jump. J Strength Cond Res. 2008, 22, 1850–1854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- SNS 24. Available online: https://www.sns24.gov.pt/servico/cheques-dentista/ (accessed on 5 May 2023).

- Calado, R.; Ferreira, C.S.; Nogueira, P.; Melo, P. Caries prevalence and treatment needs in young people in Portugal: the third national study. Community Dent Health. 2017, 34, 107–111. [Google Scholar]

- Veiga, N.J.; Pereira, C.M.; Ferreira, P.C.; Correia, I.J. Prevalence of dental caries and fissure sealants in a Portuguese sample of adolescents. PLoS One. 2015, 10, e0121299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Veiga, N.J.; Cecchi, M.H.R.D.; Martins, J.; da Cunha, I.P.; Meneghim, M.D.C.; Correia, M.J.; Couto, P. Dental caries and oral health behavior assessments among Portuguese adolescents. J Oral Res. 2020, 9, 300–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

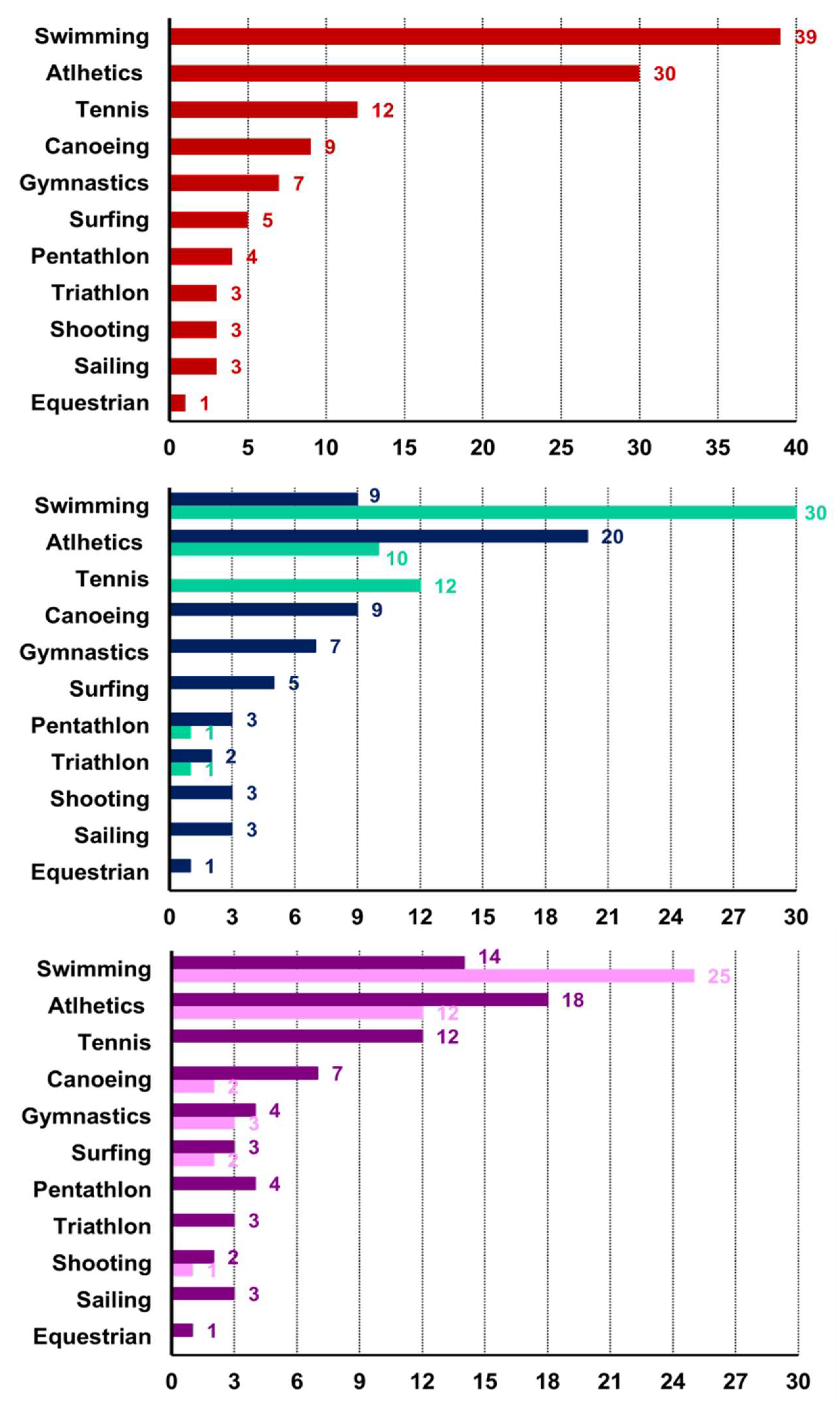

| Sport | Angle classes | Malocclusions | Caries | Missing teeth |

Fillings | Gingivitis | Visible calculus |

Bruxism signs |

Orthodontics | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| I | II | III | ||||||||||

| Swimming | 31 | 5 | 3 | 11 | 8 | 1 | 9 | 18 | 16 | 14 | 12 | |

| Athletics | 24 | 5 | 1 | 10 | 6 | 3 | 12 | 14 | 9 | 16 | 7 | |

| Tennis | 7 | 1 | 4 | 5 | 3 | - | 6 | 6 | 5 | 4 | 3 | |

| Canoeing | 6 | 1 | 2 | 5 | 1 | - | 5 | 1 | 1 | 6 | - | |

| Gymnastics | 6 | 1 | - | 3 | 1 | - | 1 | 1 | 1 | 5 | 2 | |

| Surfing | 5 | - | - | 2 | 2 | - | - | - | - | 2 | - | |

| Pentathlon | 4 | - | - | 1 | 1 | - | 1 | 2 | 1 | 2 | - | |

| Triathlon | 3 | - | - | - | - | - | 1 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 1 | |

| Shooting | 2 | - | 1 | 1 | - | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 2 | - | |

| Sailing | 1 | 1 | 1 | - | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | - | - | |

| Equestrian | - | 1 | - | 1 | - | - | - | - | - | 1 | - | |

| *Values represent the number of subjects in each diagnosis. | ||||||||||||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).